ABSTRACT

Words classified as ‘interjections’ tend to be treated in descriptive grammars as outside of morphosyntax, too contextually bound to warrant a systematic description of their syntagmatic relations. In this paper we argue that if one takes grammar to include recurrent patterns in conversational turns that are routinely connected with particular interactional functions, such as assessments and acknowledgements, then the grammar of interjections can indeed be incorporated into language description in ways that show the systematic relationships between form and function. We use a comparative corpus of conversations in four typologically distinct Australian Aboriginal languages (Garrwa, Gija, Jaru and Murrinhpatha) to illustrate how such an analysis may be developed. We focus on forms which have been described as ‘compassionate interjections’, which express that the speaker takes a compassionate affective stance towards something described in prior talk or evident in the situation. Despite differences in the morphological properties of these words in the languages we compare here, they display remarkable similarities in where they occur within conversational turns, and the functions they serve in different turn-related positions.

1. Introduction

Forms classified as ‘interjections’ in descriptive grammars are usually found in chapters focusing on the margins of grammar, falling outside of regular morphological and syntactic patterns. Indeed it has been one of the diagnostic criteria for interjections that they operate outside of the normal rules of constituency and sentence grammar (e.g. Wilkins, Citation1992).Footnote1 The result is that even though such forms may occur frequently in ordinary language use, and speakers have a sense of what they are used for in social interaction, rarely is there an attempt to describe their grammar: i.e. their patterns of occurrence in utterances, and their collocations with other linguistic elements.

In this paper we show that while the description of interjections might fall outside of clausal syntax, they nonetheless display regularities of form, distribution, meaning and function which can be described and explained in grammatical terms, including in terms of syntagmatic relations. We demonstrate how such a grammar may be developed through a comparative analysis of one kind of interjection in four different Australian Aboriginal language communities: Garrwa, Murrinhpatha, Gija and Jaru, as they occur in ordinary conversations.

To develop this grammar we take an interactional linguistics approach (Couper-Kuhlen & Selting, Citation2018), examining regularities of distribution, morphological and phonological realization, and pragmatic function within conversational turns. The results illustrate the context-sensitivity of grammar, and how a grammar based on conversational turns rather than clauses and phrases might usefully be integrated into descriptive linguistic practice.Footnote2

The interjection type we consider in this paper is one which has often been described as expressing compassion. In her recent book on the expression of emotions among speakers of the northern Australian language Dalabon and the English-lexified contact variety Kriol, Ponsonnet (Citation2020, p. 53) describes a form which she calls a “compassionate interjection” in both languages. The Dalabon word weh-no comes from an adjectival word meaning ‘bad’, and the Kriol equivalent bobala, which has the form of a nominal, is etymologically derived from the English expression poor fellow. Both are described as being used in contexts where there is an expression of pity towards the misfortune of others, illustrated in (1) and (2), where the speaker comments on a third party being upset:Footnote3

In Ponsonnet’s (Citation2023) survey of interjections in grammatical descriptions of 37 Australian languages, forms with a similar description to weh-no and bobala are the most frequent type of ‘expressive interjection’, being described in 43% of the grammars consulted.Footnote4 Ponsonnet (Citation2023) uses this as evidence of compassion as “a focal category”, based on the lexicalization of this cultural concept in so many different Australian languages.None of the four language groups we examine here were included in Ponsonnet’s survey, and all four are genetically and typologically distinct (see §4). Furthermore, the words under consideration are clearly not etymologically related: Garrwa kurda, Murrinhpatha ʔaʔu, Gija goorlange-/gaage-, Jaru yawiyi/luyurra. Examples (3)–(7) illustrate the formal and functional range of these tokens as recorded in multiparty conversations.Footnote5

We have observed that while each community has distinct and seemingly unrelated forms, they are used in very similar contexts including responses to bad news or misfortune (where ‘feeling sorry for’ others is evoked), and as responses to the mention or evocation of people or places regarded with affection and/or nostalgia.Footnote7 This range is illustrated in (3), from Garrwa, where the form kurda is used in response to hearing bad news – that someone the speaker knows (a classificatory grandson) may have died; in (4), from Jaru, where the form yawiyi is used in response to observing a crow in an ostensibly misfortunate situation, looking to relieve its thirst; in (5), from Gija, where the forms gaage- and goorlange- (here inflected for feminine noun-class) are used when a female referent is mentioned who is regarded with affection (no particular misfortune implied); in (6), from Murrinhpatha, where the form ʔaʔu is used with a mention of a place that the speaker regards with affection. Example (7) illustrates the use of ʔaʔu in response to observing another’s misfortune, similar to the use of yawiyi in (4).The examples show that the contexts which trigger the use of the token need not be linguistic. For example, in both the Jaru example in (4) and the Murrinhpatha example in (7), the token appears triggered by the observation of another’s misfortune – a crow which appears to be looking for water, and a child who has injured her foot. In (4) the speaker first describes her observation of the situation with a Kriol formulation i waitin fo ngaba ‘It is waiting for water’ before using the token yawiyi. In (7), there is no such description, but the situation to which the token pertains (line 2) is clear because the injured child’s limp is plain to see.

This range of contexts accords with Ponsonnet’s (Citation2020, p. 53) observations that compassionate interjections in Dalabon and Kriol not only express immediate pity, as illustrated in (1) and (2), but rather more broadly express “a range of emotions that relate to compassion, such as endearment when witnessing other people being compassionate with one another […] and sympathetic emotions (e.g. relief or joy for others)”.

Ponsonnet’s (Citation2023) survey of interjections in Australian languages was based on what has been published in descriptive grammars, and she explicitly only included forms which had been classified as interjections in these grammars. The ones considered to be compassionate interjections are those which are described as such in the grammars, or minimally given glosses of ‘poor fellow/thing’. However, as the typological, semantic and pragmatic literature attests, interjections are a notoriously difficult class of forms to define homogenously, with most approaches applying some combination of formal and functional criteria (see Borchmann (Citation2019) and Dingemanse (Citation2023) for recent syntheses of these approaches). Comparison of interjections across published grammars thus relies on the criteria the grammar-writer has used to decide what counted as an interjection. As these forms are usually considered to fall outside of morphosyntax, their inclusion in grammars is often as a list of expressions, with or without attested contextualized examples. This makes it challenging to conduct comparative studies of such forms.

In this paper we use a comparative corpus of multiparty conversations in each of the four communities to examine the distribution of compassionate interjections as lexicalized forms that display a particular affective stance associated with the English term ‘compassion’ (see §3). We examine not only the range of situational contexts in which speakers spontaneously use such tokens, but also their associated prosody, their positions within conversational turns and sequences, and the observable impacts that their use has on others participating in the interaction.

Before discussing the conversational data that form the basis of the current study, we review how interjections have been considered as a word class in the Australian descriptive tradition (§2), and how conventional displays of compassion have been understood in the Australian context (§3). In §4 we summarize our data and the interactional linguistic approach we have taken in our analysis. In §5 we describe the interactional syntax of compassionate tokens as affective stance markers, demonstrating regularities in their syntactic distribution across the four corpora. In §6 we present some preliminary observations concerning the development of compassionate interjections from nominal and verbal forms.

2. Interjections

In Australian descriptive linguistics, the word class ‘interjection’ is usually described as comprising uninflecting free forms which can stand alone as a conversational turn and which may display deviant or unusual phonological features (e.g. English tsk, psst) (e.g. Ameka, Citation1992; Wilkins, Citation1992). Forms lacking inflectional morphology are often classified formally as particles, with interjections constituting a type of particle (e.g. Gaby (Citation2017, p. 100) calls them ‘interjective particles’). Some of these forms, particularly those which have deviant phonological characteristics, do not appear to have historical reflexes or contemporary polysemies with words ascribed to other word classes (e.g. tsk, wow). These have been called ‘primary’ interjections (Ameka, Citation1992). Of the four languages we examine in this paper, only Murrinhpatha ʔaʔu displays deviant phonological characteristics (the glottal stop is not a conventional phoneme in Murrinhpatha).

However, many forms classified as interjections share formal properties or historical connections with other word classes. For example, both Dalabon weh-no and Kriol bobala are historically derived from verb and nominal forms respectively, although they have lost their inflectional productivity and referentiality in contemporary language use. Reber (Citation2012), in her interactional linguistic study of English sound objects, follows Nübling (Citation2004) in using “lack of referentiality” as a heuristic for interjection as a word class. That is, forms which may appear similar to, for example, nouns and verbs, are no longer semantically functioning as nouns and verbs.

Some compassionate expressions do retain morphological productivity as attested in the Gija example (5). This example illustrates two distinct roots for displaying compassion: gaage- and goorlangge-, both of which require noun-class marking (masculine, feminine or non-singular), which is a hallmark of Gija nominals and verbal agreement. Although Gija noun-class suffixes appearing on compassionate interjections do not reliably index the (semantic) gender of their targets, the retention of noun-class marking at all suggests retention of certain properties of nominals, including perhaps referentiality, that we do not see formally expressed by compassionate tokens in the other Australian languages described to date. We return to this in §6.

Interjections which have observable connections with other parts of speech, such as the Gija example above, have been considered less prototypical than ones without such connections. For example, Gaby (Citation2017, p. 365) considers prototypical Kuuk Thayorre interjections to be forms which are not derived from other parts of speech (e.g. ngeeca ‘hooray’ as a response to good news, ngee ‘I see’) so that the form meer.kun.waar ‘poor thing’, derived from noun roots meaning ‘eye’, ‘bum’ and ‘bad’ respectively, is described as ‘atypical’. Interjections with observable properties of other parts of speech have also been called ‘secondary’ interjections (Ameka, Citation1992). Secondary interjections include those which can be derived historically from other word classes, as well as phrasal constructions, such as English bloody hell, good grief.

Aside from their morphophonological characteristics as fixed and uninflected expressions (with or without deviant phonology), interjections are described as falling outside of sentence (phrasal and clausal) grammar, being able to constitute an “utterance on its own” (Wilkins, Citation1992, p. 124). The syntactic independence of interjections is often considered a diagnostic criterion in grammatical description. However, the heuristic value is somewhat diminished when one considers any linguistic expression in a language can – and frequently does – occur as a single item in a conversational turn, for example in answer to a question, or as a way of incrementing a prior turn, and this is not limited by word class or indeed even wordhood.Footnote8

Furthermore, as (1)–(7) show, forms which have been classified as interjections can also occur in multi-word utterances: in (1), (2) and (5) weh-no, bobala and gaagel occur at the end of a turn following other contentful language; in (3), (5), (6), kurda, goorlangel and ʔaʔu both occur turn-initially; in (4) yawiyi occurs at the possible conclusion of a turn (i.e. finally after a prosodically and grammatically complete utterance), but the same speaker continues speaking. In (7), ʔaʔu constitutes the entire turn. These regularities suggest syntagmatic relations with respect to turn position.

There are also systematic correspondences with prosodic domains, as Gaby (Citation2017) notes for Kuuk Thayorre ‘interjective particles’ which “may be uttered in isolation as a complete, non-elliptical utterance” but where they are “uttered as part of a larger utterance, they tend to be separated from the following or preceding clause by a pause and an intonational break” (p. 100). This suggests that the grammatical description of interjections needs to incorporate not only their syntagmatic distribution but also their prosodic properties.

In addition to the description of formal (phonological and morphosyntactic) features, there have also been attempts to classify types of interjections according to semantic and pragmatic criteria. Like many linguists working on Australian languages, Ponsonnet (Citation2023) adopts Ameka’s (Citation1992) three-way classification of interjections: conative (‘aimed at an auditor’, ‘demand an action or response’); phatic (‘used in the establishment and maintenance of communicative contact’); and expressive (‘symptoms of a speaker’s mental state’), with acknowledgement of semantic heterogeneity and the possibility of idiosyncrasy in usage. As an expression of emotion, Ponsonnet includes compassionate interjections as a type of expressive interjection (as does Gaby (Citation2017) for Kuuk Thayorre). Indeed Reber (Citation2012), following Nübling (Citation2004), considers the expression of ‘spontaneous emotion’ to be a heuristic for identifying interjections.

Spontaneous responsive expressions, including interjections, are a kind of ‘response cry’ (Goffman, Citation1978), a vocalization displaying “the examination of our relation to social situations at large, not merely our relation to conversations” (p. 794). Goffman’s (Citation1978) response cries are responsive actions by an individual often to their own fortune or misfortune and their emotions resulting from their own experiences, but also in response to another’s turn of talk, and, unlike many other kinds of social actions, not strongly mobilizing a next action by another participant. Nonetheless, as Goffman (Citation1978, p. 800) notes:

Witnesses can seize the occasion of certain response cries to shake their heads in sympathy, cluck, and generally feel that the way has been made easy for them to initiate passing remarks, attesting to fellow feeling; but they aren’t obliged to do so.

As Ponsonnet (Citation2023) makes clear, while many descriptive grammars make use of the term ‘interjection’ to describe a class of words using formal, semantic and sometimes functional criteria to differentiate them from other word classes, the result is often a heterogenous set. In this section we have suggested that at least some of these formal and semantic criteria are inherently problematic, as they are built on traditional models of grammar that require words to be assigned to classes, syntax to be restricted to phrases and clauses, and semantics to reflect cognitive structures and processes.

An interactional linguistic approach, such as we take in this paper, considers all productions of language as part of the constellation of resources that people can utilize in order to accomplish social actions. Under this approach, compassionate interjections of the kind we examine in this paper are linguistic routines for displaying an affective stance, instantiated and positioned systematically in conversational turns. The lexicalization of such constructions as particles bereft of inflectional morphology is evidence of their routine usage, where frequency of usage results in less particularized semantics and syntactic ‘emancipation’ (Haiman, Citation1994). Our claim is that such forms do have both semantic and syntactic properties that may be included in language descriptions. But these properties must be understood in terms of the interactional contexts in which they emerge.

3. Conventional expressions of compassion

Compassion can be defined as “the feeling or emotion, when a person is moved by the suffering or distress of another” (Oxford English Dictionary, Citation2000, accessed 2.9.21), according with Western philosophical and psychological uses of the term (e.g. see Gilbert (Citation2017) for a review).Footnote9 Compassion is usually considered positively as a hallmark prosocial behaviour in human societies and cultures in general (Gilbert, Citation2010, Citation2017; Gilbert et al., Citation2019). It is therefore not difficult to see why different languages and cultures might develop conventional ways for compassionate feelings to be outwardly expressed in acts of affective stance taking, as evidence for prosociality.

There is now a substantial literature on affective stance-taking in interaction, using conversation analysis and interactional linguistic methods (e.g. Couper-Kuhlen, Citation2012; Ochs & Schieffelin, Citation1989; Reber, Citation2012; Selting, Citation2010). A related focus in conversation analysis research has been on empathic responses to the telling of misfortune, with or without emotional displays or response cries, where one participant’s response aligns with and responds to another’s affective stance. In conversation analysis literature there has been particular interest in a form of talk known as troubles telling (e.g. Jefferson, Citation1988), where people report on their own negative experiences. According to Heritage (Citation2011), an empathic response is a stance displayed in response to hearing this negative experience, that “affirms the nature of the experience and its meaning, and […] affiliates with the stance of the experience towards them” (Heritage, Citation2011, p. 160). Such empathic responses may also display compassion as we have characterized it here, especially if the response attends to the troubles teller’s misfortune explicitly, but we have not found any studies in the conversation analysis literature which focus specifically on compassion as an affective stance.

The expressions of affective stance through compassionate interjections of the kind illustrated in (1)–(7) above are, typically, neither responses to one’s own misfortune, nor responses to troubles telling. Rather, they express a stance with respect to a third party, who may or may not be present at the time of talking. Goffman (Citation1978, p. 805) allows for such ‘thrice-removed’ response cries, as articulated in the following quote:

… response cries are often employed thrice-removed from the crisis to which they are supposed to be a blurted response: a friend tells us about something startling and costly that happened to him, and at the point of disclosure we utter a response cry – on his behalf, as it were, out of sympathetic identification and as a sign that we are fully following his exposition. In fact we may offer a response cry when he recounts something that happened to someone ELSE. In these cases, we are certainly far removed from the exigent event being replayed and just as far removed from its consequences, including any question of having to take immediate rescuing action. Interestingly, there are some cries which seem to occur more commonly in our response to another’s fate as it is recounted to us (good or bad) than they do in our response to our own.

Lyn’s attitude towards this third party is further reinforced in her next turn where she compares the misfortune of Pat – who has also lost his job – with this poor guy who not only had previous experiences of being retrenched, but was also retrenched without mitigating factors such as the whole business being shut down. Mal’s sure response in line 15 shows alignment with this stance without contributing further, and the talk moves back to the general situation at the company, rather than this guy in particular.

Example (8) shows that while Australian English does not appear to have a single lexical item that directly translates the compassionate interjections illustrated in (1)–(7), the phrase poor X is a fixed construction: it has a required item (poor), which is restricted to either generic referents (guy, thing, sod), or accusative pronouns (me, you, us, etc).

The reported prevalence of lexicalized compassionate tokens in Australian Aboriginal languages of the kind illustrated in (1)–(7) raises the question of the particular role(s) of expressions of compassion in these Australian Aboriginal cultures and what this says about the moral order in these communities (Ponsonnet, Citation2018, Citation2023). Earlier anthropological work has identified compassion as a particular cultural value in some communities. For example, Myers (Citation1986, p. 113) discusses the Pintupi term ngaltutjarra (lit. ‘compassion-having’) and explains that this concept recognizes:

… shared identity or empathy between the person who is compassionate and another. This identity is the source of the other’s legitimate claim on one’s compassion. Not to have compassion or not to display it is interpreted as ‘not liking’ the other person – that is, not recognizing the link.

4. Data and methods

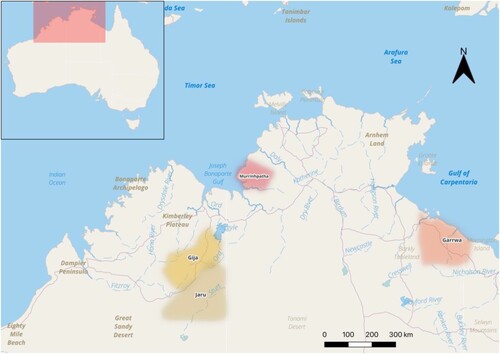

Our data come from a corpus of video-recorded multiparty conversations in four different Aboriginal communities whose traditional languages are Murrinhpatha, Jaru, Garrwa and Gija, shown on the map in .

Figure 1. Areas in northern Australia, where Jaru, Gija, Murrinhpatha and Garrwa are traditionally spoken

These four languages belong to different language families within Australia: Garrwan, Pama-Nyungan (Ngumpin-Yapa), Southern Daly and Jarragan. They are typologically distinct from each other: for example Garrwa has no noun classes, no complex predication, and tense/aspect is marked with positional clitics rather than directly on verbs (Mushin, Citation2012); Jaru has no noun classes but does have complex predication with verbs inflecting for tense/aspect/mood categories (Dahmen et al., Citation2020; Tsunoda, Citation1981); Murrinhpatha has polysynthetic verbs with complex predication and tense/aspect/mood inflection, as well as a noun classification system (Hill, Citation2019; Mansfield, Citation2019); Gija has complex predication, tense/aspect/mood marking on verbs and an extensive system of noun-class agreement (de Dear et al., Citation2020; Kofod et al., Citation2022).

Of the four, Murrinhpatha is the only language still spoken by all generations and those conversations are largely monolingual. Jaru, Garrwa and Gija are all only spoken by older community members and conversations are commonly multilingual, using these languages as well as local English-based vernacular varieties (‘Kriol’ or Aboriginal English) (Dahmen, Citation2022; Mushin, Citation2010).

The corpus comprises video-recordings of ordinary conversations conducted between three or more members of the language community in question, usually recorded with two HD cameras and a multitrack audio recorder where each participant wore a lapel mic. Video and audio sources were then synchronized in post-production.Footnote12 The conversations were always between people who would normally talk with each other. We left it up to the people we recorded as to what they talked about, and where they positioned themselves. Recordings were transcribed using ELAN and checked with the people we recorded for accuracy and appropriateness. For each corpus between 3 and 6 h of conversation have been transcribed.

As our aim in this study was to develop a comparative analysis of the grammar of compassionate interjections, we started with those expressions that occurred in our recordings – Garrwa kurda, Murrinhpatha ʔaʔu, Gija gaage- and goorlangge-, and Jaru yawiyi and luyurra – and developed a rich description of the turn and sequence organization of the talk surrounding the use of each token.Footnote13 These were by far the most frequent tokens expressing compassion in each language. Jaru and Gija speakers occasionally used Kriol bobala, but this did not occur in the Garrwa recordings (although Garrwa speakers are familiar with the word bobala). Older Jaru speakers tended to use the form luyurra in places where yawi could occur so we have included both in the analysis. Murrinhpatha has a song language form tjingarru that is translated as ‘poor thing’. The Garrwa form kurda is used across the languages of the Borroloola region, such as Yanyuwa (Gaby & Bradley Citation2017). An older word, warriyaluku ‘poor thing’, is recognized by Garrwa speakers but did not occur in our recordings. The two Gija roots are reported as being interchangeable.

Using next-turn proof procedure (Hutchby & Wooffitt, Citation1998, p. 15) we examined what triggered the use of each token and considered the extent to which the use of the token had an impact on what happened next in that interaction. We also looked at whether the token occurred as a standalone conversational turn, or whether it co-occurred with other ‘interjections’ or with other substantive talk within the same turn. We examined whether the token occurred initially, medially or finally within the turn in which it appeared. We also examined the prosody of the token in relation to other marked prosody which may be associated with a compassionate affective stance.

Our analysis takes into account the distinction between conversational turns, which are “ … utterances that speakers produce when they occupy the floor” (Couper-Kuhlen & Selting, Citation2018, p. 34), and turn construction units (TCUs), which are the linguistic building blocks of turns. The boundaries of TCUs are loci where a change in speaker may become relevant – a prospective end of the current turn (Sacks et al., Citation1974). TCUs can be linguistically composed of words, phrases, clauses or multiple clauses. The boundaries of these very often coincide with a final intonation boundary, completed embodied conduct (such as gesture) and a recognizable completion of a social action. These resources provide recipients with a wealth of online evidence for where the current turn may conclude and the floor become available for the next turn (Ford et al., Citation1996; Li, Citation2014).Footnote14

Actual turns may therefore consist of one or more TCUs. For example, in the Jaru example in (4) (repeated as (9) below), Rosie’s single turn consists of two TCUs: the first TCU is composed syntactically of a full clause plus a compassionate interjection; and the second TCU is a nominal destiwan comprising a turn increment that provides further evidence for the stance taken (i.e. the crow is thirsty and so warrants compassion).

We examined all instances of these tokens that occurred in all four corpora. presents both the number of tokens and their position in TCUs. Compassionate tokens which occurred on their own in a turn, or with other interjections, invariably functioned as a response and were not used to initiate new actions. These are response tokens (cf. Gardner, Citation2001), functioning as a kind of assessment. In the other two contexts, the compassionate interjection was usually prosodically offset from the same-speaker talk that preceded and/or followed it. This regular prosodic disjunction suggests a looser syntactic integration than if these interjections occurred within the same prosodic unit (see Mushin (Citation2018) for an analysis of prosody and syntactic integration of a turn-initial particle in Garrwa).The total numbers of compassionate interjections range from 23 in the Murrinhpatha conversation to 167 in the Gija data.Footnote15 The overall number of tokens found for each language is largely a consequence of what was being talked about in the conversations we recorded. Some topics were more conducive to affective stance taking, including compassion, nostalgia and affection associated with the use of these tokens. This also meant that uses tended to cluster, as we saw in (5) above from Gija, where both gaage- and goorlage- are used by the same speaker expressing affectionate anticipation for the arrival of a ‘poor’ sister.

Table 1. The corpus of compassionate interjections

In addition to numerical differences in the overall number of tokens, there is also some variation in the relative proportions of tokens in different positions in the turn: in the Garrwa and Murrinhpatha collections more standalone response tokens are uttered than tokens produced in the same turn with additional substantive talk (62% vs 38% for Garrwa and 87% vs 13% for Murrinhpatha). Where the compassionate interjection occurred with other substantive talk by the same speaker in the same TCU, ʔaʔu only occurred TCU-initially in Murrinhpatha (and then only three times), while Garrwa kurda occurred slightly more often in TCU-initial position than final position.

The distribution is somewhat complicated in the Jaru and Gija corpora due to the use of more than one term as a compassionate interjection. In Jaru, luyurra is mostly used by older speakers and overall occurred less frequently than yawiyi. Both luyurra and yawiyi occurred in combination with other response tokens more often than as a standalone particle (cf. Garrwa and Murrinhpatha). Both luyurra and yawiyi also occurred in turns with other substantive talk in far greater proportions than Garrwa and Murrinhpatha, with turn-final being the most frequent proportion of yawiyi.

In Gija, both goorlange- and gaage- were used by all speakers, but with about double the number of tokens of gaage- compared with goorlange-. While both roots were found in all positions, similar to Jaru and Garrwa, the proportions differed: gaage- was more likely found in turns consisting of response tokens only (as standalone or with other interjections); while goorlangge- occurred in a higher proportion of turns which included substantive talk. Like Jaru yawiyi, both goorlange- and gaage- occurred TCU-finally substantially more often than TCU-initially.

However, while the proportions are different in the different languages, there are also a lot of common features. In all four languages, compassionate interjections can stand alone in a TCU, or can occur in combination with other interjective particles; they can also occur at the boundaries of TCUs consisting of other substantive talk, as we discuss in the next section. What we do not find are instances of compassionate tokens turn-medially in a TCU, corresponding to occurrences within phrasal or clausal units.

5. Towards an interactional grammar of compassionate interjections

In this section we focus in more detail on the recurrent features of compassionate interjections as they emerged in each of the three syntactic environments outlined in above: as response tokens (§5.1), TCU final (§5.2) and TCU initial (§5.3). We focus in particular on the timing and prosody of the tokens in relation to the surrounding talk; their collocation with other linguistic objects and whether their scope of affective stance-taking was prospective or retrospective to the surrounding talk.

5.1 Response tokens

Compassionate interjections were commonly found as the sole element in a turn as an assessment response. Like many response tokens, their use does not strongly project a clear next action by speaker or recipient(s), but rather retrospectively displays the speaker’s stance towards something in the immediate prior context.Footnote16 The response may be to something someone else has said, or it may be to something in the immediate situational context. They express the stance of a listener or recipient without a strong implication that the speaker of the compassionate interjection is trying to take the floor (Gardner, Citation2001). This is shown in the Garrwa extract in (10) where three different participants utter kurda in response to a misfortunate story event.

From line 1 of (10), Peggy begins to tell a story of a time when she was at home (in ‘Garrwa One’ camp) and discovered that a python had swallowed her pet cat. Each of the three recipients of the story (Marjorie, Miriam and Shirley) responds with a stand alone kurda, each one responding to a different part of Peggy’s unfolding story. Marjorie’s soft and falsetto kurda comes after Peggy introduces the little cat with some display of affection by characterizing it in a falsetto voice as lilwan ‘little’. Marjorie’s kurda thus aligns with Peggy’s affectionate stance. After a 2.2 s gap, Peggy continues, adding further information about the sequence in which the python managed to swallow the cat.Footnote17 There are two parts to the turn in line 9. Miriam’s level ah. kurda, responds to the first of these, while Shirley’s extended, level soft kurda responds to the second of these. These responses thus appear to display compassion for the now-ingested feline.As (10) illustrates, kurda is uttered in response to a reported bad experience suffered by a third person referent (here, the cat): Marjorie’s kurda comes after the introduction of the cat but before its untimely demise has been mentioned; both Miriam and Shirley’s kurdas come after the event of swallowing has been mentioned.Footnote18

There is also evidence that speakers are not constrained to using a compassionate interjection to express an affective stance response. This may also be accomplished by other response tokens and by prosodic features (cf. Jefferson, Citation1984). Example (11), also from Garrwa, shows kurda as one of a number of response types uttered by different speakers upon hearing the same information. Peggy, Shirley, Marjorie and Miriam have been working with a botanist, Glenn, and Ilana on plant and animal knowledge. Glenn had been telling the women about the impact of Cane Toads on the Northern Quoll (a carnivorous marsupial) population.

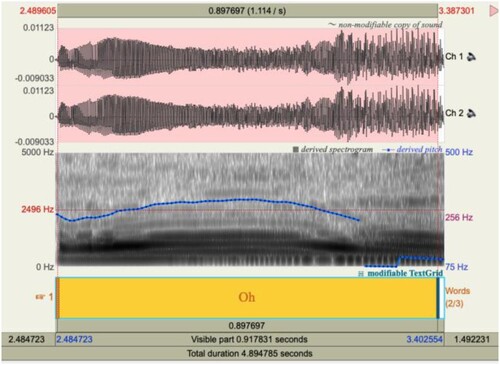

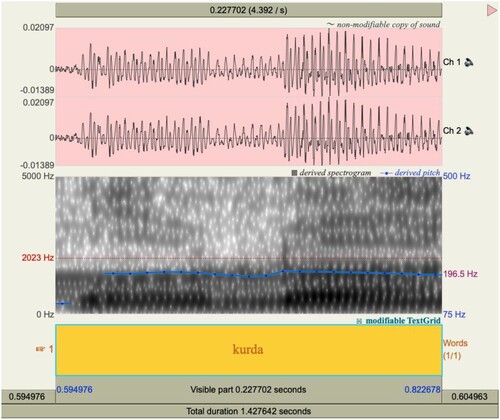

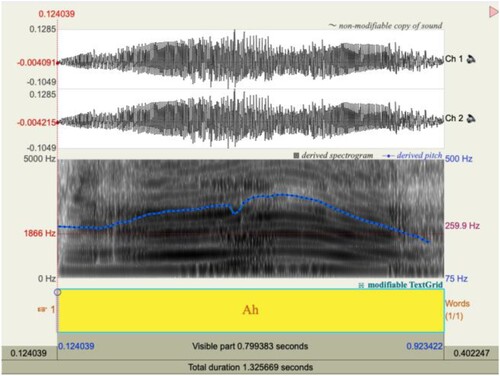

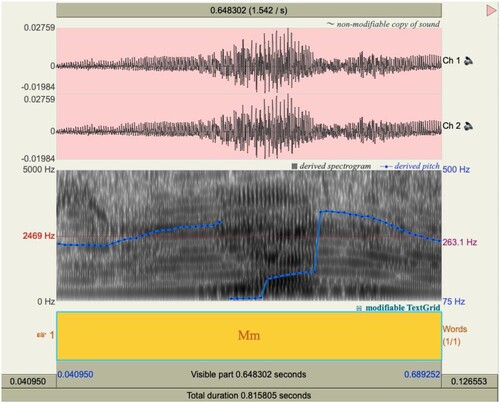

At line 1, Glenn tells the four women that Northern Quolls (that little spotted back) are the only mammal to be made locally extinct by the introduction of the Cane Toad. All four women respond to hearing about this misfortune in near unison. Given the prevalent use of kurda in (10) for expressing compassion for an animal, Miriam’s use of kurda in line 4 () seems very apt. However, the other three women produce other response tokens in the same slot: Marjorie says oh (), Shirley says mm () and Peggy says ah (). While all three tokens are expressed as a single phoneme, they share an elongated (above 0.6 s) rise–fall intonation contour, which is widely associated with “heightened involvement in the talk”, such as expressing an emotion or assessment (Gardner, Citation2001, p. 235). So, while Marjorie and Peggy’s oh/ah tokens may reflect the receipt of this information as news (Heritage, Citation1984), and Shirley’s mm may reflect a more neutral acknowledgement of receipt (Gardner, Citation2001), the synchronized intonation contour shows an affective stance towards this information. In contrast, Miriam’s kurda is uttered with a short (0.2 s), flat intonation contour, one which is not usually associated with more emotive expression.In line 7, Glenn then adds a positive assessment of the Northern Quoll as a ‘really good hunter’, and in line 10 Marjorie now responds with a short, flat kurda, rather than another news receipt. At the same time, Shirley utters another elongated mm – this time with rising intonation – suggestive of a continuer rather than an assessment, soliciting further talk from Glenn (Gardner, Citation2001). This seems to be how Glenn has understood Shirley’s mm as he provides a confirming yeah to his assessment in line 13. Peggy’s yeah with falling intonation in line 12 occurs after Marjorie and Shirley have responded to Glenn’s assessment and appears designed to agree with the assessment of the Northern Quoll as a good hunter. The lack of the rise–fall intonation contour across these three different lexical responses to Glenn’s assessment in line 9 suggests that only Marjorie’s kurda retains the affective stance of compassion.

Figure 4. Shirley’s mm (line 5) – 0.6 s rise–fall (perturbation caused by overlap with other speakers)

We have yet to complete a systematic detailed phonetic analysis of the standalone compassionate interjections in our corpus, but we can make some initial observations: the complementarity of a neutral prosody on kurda compared with marked expressive prosody on other response tokens in (11) suggests that compassionate interjections need not rely on prosody to convey affect. Nonetheless, we did find a range of prosodic shapes of compassionate interjections in all four of the languages and across recordings. Some were short and level, as in (11) while others were elongated and level, such as Shirley’s kurda in (10). In addition to level tones, compassionate interjections also occurred with stepped pitch movements (up or down), but without strong rising or falling contours at their boundaries. We leave for future work a more systematic instrumental analysis of prosody and compassionate interjections, including whether there are conventional associations between particular contours and their interactive functions.

Example (11) illustrated standalone compassionate interjections occurring in the same environments as other response tokens such as news-markers or minimal responses, something we found for all four languages.Footnote19 In all cases, the compassionate interjection occurred second in a sequence of two. An example of this from the Garrwa corpus is in (10) above, line 10, where Miriam responds to Peggy’s story first with a news receipt (ah with falling intonation) followed by a level kurda. In this example, the two interjections are in two separate intonation units, but combinations of interjection + compassionate interjection can also occur in the same intonation unit, as in (12), where Marjorie responds ah kurda (one intonation contour) to hearing that the Northern Quolls have disappeared from Glenn’s neighbourhood.

The recurrent co-occurrence of compassionate interjections with news receipts is perhaps indicative of their function as a response to hearing of the misfortune of others as new information.5.2 TCU final

In the examples presented so far, the compassionate interjection provided an affective response to something someone else had said, or on witnessing someone’s misfortune. Compassionate interjections can also occur following the end of a TCU by the same speaker, as illustrated by the Garrwa example in (13), where kurda occurs at the end of Shirley’s turn as a kind of tag with scope over what Shirley has just asserted.

In (13), Shirley’s turn occurs after a lapse in the conversation when Glenn is preparing to sit on his chair ahead of starting to work on the Plant and Animal Book, and Peggy is talking quietly about getting some tobacco out. At line 8 Shirley recycles an earlier topic where it was established that Shirley had not been able to find her key card ( = debit card) earlier that morning. Her turn-final kurda looks retrospectively at this misfortunate situation, one which directly impacts herself as she will not be able to access her bank account without it. When Shirley utters this turn, her gaze is forwards and not directed to any other participant as potential recipient (Blythe et al., Citation2018). That is, there does not seem to be any attempt to draw aligning affective stances from anyone else, and indeed the matter is dropped.In (13) there is a clear intonation boundary between the main assertion and the compassionate interjection. However, we also found examples of turn-final compassionate interjections where the interjections appeared more integrated into the other substantive talk of the turn. To illustrate this, we return to the Jaru example discussed as (4) and (9) above. Here the target TCU is given with surrounding context.

In extract (14) the four children Jack, Anna, Rose and Tom are talking about a crow which seems to be waiting for them to leave so it can drink from the water hole at which they are playing. When Jack directs the children’s visual attention to the crow and points out that it is still there (lines 1–3), Rose explains that it is waiting to drink some water (line 6). Rose’s verbal account of the situation is immediately followed by the prosodically integrated token yawiyi, which is latched onto the preceding talk. Through the latched token, Rose retrospectively expresses her compassionate stance towards the crow’s situation before any of the other children have an opportunity to respond. By adding destiwan ‘thirsty one’ (line 6) Rose also follows up with an explanation of why the crow deserves compassion, making a compassionate response by the other interlocutors relevant next. At line 8 Jack affiliates with Rose’s stance and utters a high-pitched interjection o:h with a quavering voice followed by the token yawiyi, before asserting that the children will make room when the crow approaches. While the token here follows a prior syntactic and semantic closure, there is no prosodic break which means the token is heard as being part of the turn’s initial TCU.As (13) and (14) illustrate, TCU-final compassionate interjections across our corpus retrospectively displayed a stance towards a situation that has already been established through talk by the same speaker. This contrasts with the response token uses which, while also retrospective in orientation, are responding to another speaker’s talk or action. In turn-final cases, the talk preceding the use of the token makes some reference to the situation which is to be deemed worthy of compassion, such as the loss of a debit card (13) or the plight of a thirsty crow (14).

5.3 TCU initial

As shows, each of the languages we have examined in this paper allows the compassionate interjections to appear as prefaces to larger turns. Rather than responding to the current speaker’s, or another speaker’s, prior talk, some of these tokens index the stance the current speaker is about to take towards a situation that is yet to be described in forthcoming turns. These prospectively oriented tokens tend to project wistful, sorrowful or sentimental moments, for which recipient alignment and affiliation should be expected. When they occur following a lapse, they signal a topical departure from the prior talk. This type of stance-taking preface is exemplified in (15), where the Jaru interjection yawiyi, which follows a 4-second lapse, foreshadows the pitiful topic of the forthcoming talk. Juanita uses the token to shift the discussion from a stocky cat to an unrelated topic, namely a relative needing an operation following a motorcycle accident.

The talk starts up in this extract after a 4-second lapse that is followed by a simultaneous start between Christine and Juanita (lines 2–3), before Christine drops out. At line 3 Juanita introduces a new conversation topic by announcing that her nephew Jabalyi has left, a piece of information that is not news to any of the conversationalists, but that provides an opportunity to commiserate with Jabalyi’s predicament. This mournful lament is preceded by a prosodically integrated token yawiyi that indicates the launch of a new topic and simultaneously projects its pitiful nature. In this sequential position, the token is uttered not as a compassionate response but rather as a preface to project the speaker’s stance toward what will be said next. Christine affiliates with Juanita by repeating the token yawiyi as an aligning response (line 5). At line 8 Judy wonders whether he has already gone into the operating theatre, which Christine confirms to be the case, having recently read her sister Molly’s Facebook update. In her ensuing contributions, Christine re-utters the token yawiyi two additional times to display her affective stance (lines 10 and 12).Similarly, (16) illustrates a prospectively oriented token in Murrinhpatha occurring after a lapse. In this extract, Alice, Lily, Rita and Karen are sitting on the beach while the sun sets into the sea. As further context, Alice and Lily belong to a clan that has the sun (nanthi tina) as their totem. One’s clan totems are regarded as one’s siblings, so they consider the sun to be their sister (in the dreaming she is a woman). Rita and Karen’s mothers were of the same clan, so they are in their ‘mothers’ country’ (their kangathi). They regard the sun as their mothers’ sister, and consider her to be another ‘mother’.

Table

After the lapse in line 1, Karen at line 3 pronounces that ‘This place/this is the place’ (ʔaʔu kanyirda dayu). At line 4 Lily initiates repair (yu ngarra, ‘yeah what/where?’). Alice, while gazing directly at Karen, proffers ‘your mother’s country?’ at line 6, as a candidate gloss for Karen’s elliptical pronouncement. Gazing toward the sea (see the photo within (16)), at line 8 Karen confirms Alice’s proffer to be correct (yu, ‘yeah’), adding that the sun (her mother’s totem) is right in front of them. At line 9 Alice (whose totem is the sun) adds that ‘it/she is standing here’. At line 9 Karen then turns toward Rita, informing her that their respective mother is setting in front of them.Footnote20 At line 12 Lily also urges Rita to look before Karen then reiterates that the sun is descending (line 14).

From a referential perspective, Karen’s initial pronouncement at line 3 is hugely underspecified and Lily’s attempt to initiate repair apparently deals with not understanding where or what Karen might be talking about. Despite the vagueness, however, when prefaced with ʔaʔu her pronouncement seems to project an air of sentimentality. Seemingly ʔaʔu provides Alice a touchstone that makes this vague reference less opaque. The candidate gloss she proffers at line 8 (‘your mother’s country?’) reveals that she has at least some idea about what Karen might be leading up to saying. Karen’s confirmation that it is the sun that is there in front of them (line 8), who is her and Rita’s mother (line 11), and who is descending into the sea (line 14), is a profoundly spiritual representation of this most resplendent scene. Her portrayal of this scene is not only imbued with totemic significance, but also with the nostalgia they have for their mothers, who were of course sisters of the sun.

5.4 Summary

In this section we have shown that the three different syntactic contexts – response token, turn-final and turn-initial – correspond with three different interactional functions. The interjections that occurred on their own or in combination with other interjections are always response tokens: They display an affective stance over some prior talk or prior or current situation. As listener responses they do not in and of themselves project an imminent change in speakerhood, nor do they project that the current speaker will go on to say something more substantial (Jefferson, Citation1984). In such cases the turn of talk is not wholly functioning to display a particular affective stance as a listener response, but is also accomplishing other social actions, such as assessments, as in (10), or announcements, as in (11).

We also have shown that they could occur at the end of a TCU as a way of imbuing the turn-so-far with the speaker’s affective stance. And they occurred as a turn preface to prospectively frame the upcoming talk as one displaying a compassionate affective stance. We showed that when such tokens were used prospectively, they evoked affiliating compassionate and/or affectionate responses from others.

That we found examples of all of these positions and all of these functions in the four languages shows that not only are the semantics of compassionate interjections remarkably similar in all four languages, so is their grammar. This in turn demonstrates that affective stance taking is a generalizable interactional practice and thus constitutes the routinization of social actions. Such routinizations are the cradle of grammaticalization, where frequency of recurrent linguistic behaviours leads to their coalescence in to new grammatical and lexical forms (e.g. Bybee & Hopper, Citation2001; Hopper & Traugott, Citation2003). While we are not yet able to provide a full account of how Garrwa kurda, Murrinhpatha ʔaʔu, Gija gaage- and goorlangge-, and Jaru yawiyi and luyurra emerged as compassionate interjections, in the next section we consider their respective lexical properties, which raise questions about how ‘interjections’ might be understood as a lexical class.

6. The lexical status of interjections

As we discussed in §2, Ameka (Citation1992) classified interjections into ‘primary’ and ‘secondary’ types, where the primary types displayed irregular phonological patterns and/or no etymological relationship with other lexemes, and the secondary types were transparently related to other words in the language. If we apply this classification to the forms we have examined here, only Murrinhpatha ʔaʔu, with its irregular phonological form, meets the criteria for a primary interjection.

Ponsonnet (Citation2023) shows evidence of the derivation of compassionate interjections from nouns (e.g. Dalabon, Kriol and Kuuk Thayorre examples presented earlier in this paper), what would be secondary interjections in Ameka’s (Citation1992) typology. The origins of Garrwa kurda and Jaru yawiyi and luyurra are not yet clear but they both have the shape of nominal lexemes in these languages, even if they do not appear to inflect like nouns. We have no examples of these forms serving as clausal arguments, for example.

In our study, only Gija gaage- and goorlange- display clear indications of their nominal origin, as they regularly take noun-class suffixes just as other nominals do in Gija. Indeed, there is evidence that they still are able to function as referential nominal expressions, as is clear in (17) where goorlanggel serves as a host for the first person oblique clitic -ngage.

The status of goorlange- and gaage- as compassionate interjections would seem analogous to English poor thing, where the collocation can function as a core argument as well as a stance marking interjection, and this differentiates these forms from compassionate interjections in the other three languages. However, there is also morphological evidence in our corpus which suggests that Gija gaage- has moved further away from functioning as nominals do in this language, which we take as evidence of its further grammaticalization as a stance marker.As we noted earlier, Gija is the only language in our study with noun classes: masculine (singular), feminine (singular) and non-singular. All nominals must inflect for one of these categories with suffixes (-ny for masculine, -l for feminine and -m for non-singular), and noun-class concord also underpins verbal inflection, whereby third-person subjects, objects and obliques all inflect according to noun-class membership as masculine, feminine or plural. The noun-class inflection of both compassionate interjection roots can be seen in lines 2 and 4 of (18).

In (18), Mabel, Shirley, Helen and Phyllis are keen to go camping and they have been discussing who might be able to drive. An unnamed woman has been suggested as having a suitable car. At line 4 Helen refers to the woman, as mai sisda (‘my sister’, a classificatory sibling), asserting that she is likely to be able to come. At line 9, Shirley asserts (predominantly in Kriol) that she won’t go with her on account of her being ‘mad’ (a drinker). In lines 2 and 4 Helen uses a gaage- token TCU-initially and a goorlangge- TCU-finally to display a compassionate affective stance towards this woman, a female singular referent.Footnote21

Over the whole Gija corpus the goorlangge- tokens in particular usually displayed regular concordant noun-class agreement (e.g. feminine singular marking for feminine singular referents, etc). The gaagela token in line 2 of (18) also shows regular agreement, here with the third singular feminine subject of the verb nyimbiyanya ‘she will come’. However, gaage- also displayed less concordant noun-class marking behaviour. This is illustrated in (19) which is a resumption of the discussion from (18), following Shirley’s assertion that she won’t go with the woman because she is mad.

At line 12, Shirley downplays the assertion of madness where she describes her as her (classificatory) daughter, drawing an affiliative response from Mabel at line 13. All references to this classificatory daughter thus far have been marked with the feminine noun-class suffix -l (e.g. wangalal in lines 9 and 13), which accords with the woman being female.Footnote22 By contrast, her compassionate interjection at line 12 (gaagem) is plural, as is the gaagembi token in Mabel’s affiliating response at line 13, despite it expressing her affective stance toward the woman that she similarly describes as wangala-l ‘mad-feminine’. So even though Mabel’s response is triggered by the mention of the woman, feminine agreement occurs only on the nominal and not on the plural token gaagembi.

If we consider the Gija corpus as a whole, 46% of the morphologically non-singular marked gaage- tokens are discordant with the singular individuals (or entities) to whom they are indexing affect. In contrast, only 7% of the 54 goorlangge- tokens are discordant with the entities over which they have scope. So, while Gija compassionate interjections have more transparent nominal origins than Garrwa and Jaru compassionate interjections, gaage- is showing signs of losing its full morphological productivity as nominals, consistent with their development as markers of stance rather than of reference.

7. Conclusion

We began this paper with the observation that while interjections have been documented in a very wide range of Australian languages, they are often only cited in lists of forms and treated as lexical marginalia outside of syntax, commensurate more generally with the treatment of interjections as a word class (Dingemanse, Citation2023). However, our close investigation of compassionate interjections in four typologically distinct Australian language communities has revealed remarkably consistent syntagmatic patterning that we have shown corresponds with distinct interactional functions: as responses to external triggers for compassion (e.g. someone else’s talk or the situational context); as stance marking of a turn just completed; or displaying an affective stance that at times invites affiliation by other participants.

Such regular syntagmatic patterning is evident regardless of whether forms were what Ameka (Citation1992) called ‘primary interjections’ or ones that are ‘secondary’. We suggest that the remarkable similarity in the grammar of compassionate interjections across all four language groups challenges this dichotomous classification: regardless of whether root forms are also found in word classes that do integrate into clausal syntax (e.g. nouns and verbs), regardless of phonological shape, they share the same turn-based grammar and interactional functions.

Stance-marking – i.e. designing one’s turn to reflect aspects of a speaker’s position with respect to the surrounding talk/situation – is a recurrent feature of human communication. It is encoded in speech in many ways: in lexical choices (including interjections), in prosody, in TAME systems, and in vocalizations (such as laughter). Deictic systems have long been recognized as means for positioning the speaker with respect to an utterance, from Franz Boas’s early observations about evidentials in Kwakiutl (Boas et al., Citation1947) to Jakobson’s account of shifters in Slavic verbal morphology (Jakobson, Citation1971). Our study shows how we can integrate aspects of language that are not bound morphemes into the grammatical description of stance-marking.

As we have argued throughout this paper, the focus in grammatical descriptions of Australian Indigenous languages tends to be on forms which are readily integrated into clausal syntax. Forms which are not readily integrated into clausal syntax tend to be treated as free variables, not subject to rules of grammar. Here we have shown how interjections can be more rigorously described, their occurrence and positioning governed by the grammar of the conversational turn (Couper-Kuhlen & Selting, Citation2018; Ford et al., Citation2002). We expect that the routinization of affective stance-taking is what leads to the development of interjections from other lexical material, as seems evident in Gija. A more detailed analysis of grammaticalization patterns and pathways for interjections must be left for future work.

Transcription conventions (Hepburn & Bolden Citation2017)

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the Garrwa, Murrinhpatha, Jaru and Gija speakers who consented to having their interactions recorded, analyzed and presented publicly in the service of linguistic scholarship. For transcription and translation assistance, we additionally thank Daphne Mawson and Miriam Charlie (Garrwa), Nida Tchooga and Judy Tchooga (Jaru), Frances Kofod, Eileen Bray, Phyllis Thomas, Shirley Drill, Mabel Julie, Helen Clifton, Shirley Purdie and Nancy Nodea (Gija), and Elizabeth Cumaiyi, Phyllis Bunduck, Lucy Tcherna, Gertrude Nemarlak, Carmelita Perdjert, Desmond Pupuli and Jeremiah Tunmuck (Murrinhpatha). We also thank the audience at the 2020 Australian Languages Workshop for feedback on an earlier version of this work, and John Bradley, Mark Dingemanse, Maïa Ponsonnet and an anonymous reviewer for their helpful suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The data that support these findings are not publicly available but may be available on request from the corresponding author (IM) subject to explicit consent from those recorded.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ilana Mushin

Ilana Mushin is Professor of Linguistics at the University of Queensland and co-editor of the journal Interactional Linguistics (Benjamins). Her research interests include interactional linguistics, conversation analysis, language typology, and the documentation and description of Australian Indigenous languages, especially Garrwa. She is the author of A grammar of (Western) Garrwa (Mouton, 2012).

Joe Blythe

Joe Blythe is an Associate Professor in interactional linguistics. His research interests include gesture and embodiment, turn-taking, spatial cognition, language evolution, kinship concepts and social identities – particularly as instantiated within everyday conversation and as acquired by children. He leads Conversational Interaction in Aboriginal and Remote Australia, a comparative project funded by the Australian Research Council investigating conversational style in four Australian Aboriginal languages and in English varieties spoken by non-Aboriginal people in the Australian outback.

Josua Dahmen

Josua Dahmen is a postdoctoral researcher who uses an interactional-linguistic approach to study language structures in ordinary conversation. He has a special interest in the documentation and description of Australian First Nations languages and has been working in collaboration with the Jaru community in the north of Western Australia.

Caroline de Dear

Caroline de Dear is a doctoral researcher who is currently completing her dissertation on canonical and non-canonical questions in Gija conversations. Her research interests include Australian Indigenous languages, pointing and spatial language, nominal classification, interactional linguistics, and conversation analysis.

Rod Gardner

Rod Gardner is Honorary Associate Professor at the University of Queenland. He has published conversation analysis research over 30 years, on ordinary conversation, classroom interaction and Australian Indigenous conversation, the last mostly on Garrwa with Ilana Mushin.

Francesco Possemato

Francesco Possemato is a postdoctoral researcher who uses conversation analysis and interactional linguistics to study language use in social interaction in everyday and institutional contexts. His research interests include pragmatic typology, bilingualism and language maintenance, and interactions involving speakers with acquired communication disorders.

Lesley Stirling

Lesley Stirling is Professor of Linguistics and Head of the School of Languages and Linguistics at the University of Melbourne. She has published in descriptive and typological linguistics, semantics, discourse analysis and psycholinguistics, including on the grammar of the Australian language Kala Lagaw Ya. Her current research focuses on the analysis of conversational interaction.

Notes

1 In a paper examining the description of interjections in published grammars of Nepalese languages, Lahaussois (Citation2016, p. 192) notes that interjections were more likely to feature in language descriptions in cases where the authors had spent more extensive time living in the language communities.

2 Dingemanse (Citation2023) also argues for an interactional linguistic approach to the grammatical description of interjections. See also Williams et al. (Citation2020) for a recent interactional linguistic analysis of an interjective particle in the endangered Amazonian language, Wai’ikhana.

3 All of our extracts of conversation have been transcribed using conversation analysis transcription methods (Hepburn & Bolden, Citation2017) that show timing and prosodic features of talk. A full list of transcription conventions that are used is given at the end of this paper. For non-English languages we also include glosses following Leipzig conventions (with the addition of INC – inclusive; BENE – benefactive; C – catalyst; CL – classifier; EMPH – emphatic; ITER – iterative; NC – noun classifier (Murrinhpatha); NFUT – nonfuture; NS – nonsingular; O – object; PRES – present tense; S – subject; SUB – subordinator; SUBSEC – subsection; TEMP – temporal adverbial; TOP – topic; VBLZ – verbalizer) and free English translations.

4 That 57% of the grammars did not include compassionate interjections does not mean they did not occur in these languages. This underlines our point that such interjections are often marginalized in language grammars.

5 The data used in this paper come from the Conversational Interaction in Aboriginal and Remote Australia (CIARA) Project corpus (www.ciaraproject.com), funded by the Australia Research Council (DP180100515), Macquarie University and University of Queensland. We have used the following referencing convention for data from this project (Date of recordingInitials of recorderNumber of recording on date_time code (start time) time code (end time)).

6 The examples in (3)–(5) come from bilingual conversations where speakers use both traditional language and local varieties of the newer contact language Kriol. While the form bobala is attested in our Jaru data, and known as a Kriol form by participants we recorded, we found very few uses of bobala even when participants were otherwise largely speaking local Kriol varieties.

7 Gija consultant Eileen Bray (pc July 2022) reports that both gaage- and goorlangge- are used when the speaker says something that ‘makes them sorry’. Similarly, Garrwa speakers Daphne Mawson and Kathy Ger (pc April 2022) said they used kurda when ‘feeling sorry for’ the referent. Bradley (Bradley and Yanyuwa families, Citation2010, pp. 49–51, pc) notes that kurda occurs in some Yanyuwa songline songs, expressing affection for country.

8 The following example, from Sidnell (Citation2010)’s textbook on Conversation Analysis, illustrates the use of a bound derivational English morpheme as a well-formed and relevantly placed conversational turn. See Sidnell (Citation2010, p. 2) for a full discussion of this example.

9 Compassion differs from related concepts of empathy and sympathy, which are usually applied to one’s ability to understand and share the feelings of others, regardless of the feelings or emotions involved. As an emotional response to another’s suffering, compassion is reliant on our capacities for empathy, but not all empathic feelings are in relation to suffering.

10 The extract in (8) is taken from an audio-only recording of a face-to-face conversation. We expect there to be embodied displays of compassion (e.g. conventional facial expressions) alongside the audible ones.

11 This need not be framed as ‘compassion’. For example, Neely (Citation2019) describes the term shĩńãì̀ in the Panoan (Peru) language Yaminawa as referring to a ‘sad’ way of speaking which includes discussions of serious illness or death, estrangement from close friends and family (due to travel or other circumstances) and the discussion of personal problems (p. 151), and described by speakers as meaning specifically to “ … ‘remember’ or ‘think about’ distant or deceased kin or friends in a bittersweet and nostalgic way … ” (p. 68). This way of speaking is marked by distinctive prosody and the use of the form “ … tiimãwi as an ‘affective interjection’ that expresses the associated affect of úbìskṹĩ̀ ‘concern, pity, poor thing’” (p. 144).

12 All data were collected with participants’ fully informed consent. Ethical clearance was provided by the human ethics committees of Macquarie University (#5201600207) and the University of Queensland (#2019000832).

13 We did not, for example, start with all contexts in which compassion – or affective stances in general – might be expressed.

14 It is important to note that the end of a TCU does not predict that a new speaker will start talking.

15 Note that numbers and percentages are given to show the comparability of our corpora. Our highly qualitative and context-sensitive approach does not require us to quantify the data, as long as there are sufficient tokens to allow for the observation of patterns of usage within and across languages.

16 Continuers such as mm hm in English are different, in that they hand the floor back to the prior speaker, and thus do project what comes next.

17 The words in this part of the recording at line 9 are not clear but it is clear that whatever she says happened, leads to the swallowing of the cat, explicit in line 11.

18 Marjorie may be able to predict the trajectory of the story either because she has heard this story before, or because the topic of conversation prior to the story was about the habits of the Olive Python more generally and so she can infer where the story is heading.

19 As Table 1 shows, there are proportional differences across the four languages if we compare solo compassionate interjections to TCUs with combinations of response tokens. For example, the Jaru corpus shows double the number of compassionate tokens with another response token than solo standalone compassionate interjections; the Gija corpus shows equal proportions, while there are proportionally fewer in the Garrwa and Murrinhpatha corpuses. As we noted earlier when looking at the numbers, these differences may be due to the local contingencies of the interactions we recorded. The key finding here is that compassionate tokens can occur alone and in combinations in all four languages.

20 Karen initially points at Rita as she produces the 1DU.INC pronoun neki ‘your and my {mother}’ before pointing toward the sun. The term for the sunset, kempuktharr, is a verb ‘{it/she} is sunsetting’.

21 This pattern is unremarkable. Our collection of Gija compassionate tokens has twice as many gaage- tokens as goorlangge- tokens (see ), and all speakers produce both tokens. The tokens have a skewed distribution in that the gaage- tokens are more often produced as response tokens (62%) than with substantial other talk (37%), whereas the goorlangge- tokens are more often produced with substantial talk (74%) than as response tokens (26%).

22 In codeswitched speech, Gija nominals that surface in Kriol matrix clauses are often, but not always and not here, stripped of their noun-class suffixes.

References

- Ameka, F. K. (1992). Interjections: The universal yet neglected part of speech. Journal of Pragmatics, 18(2–3), 101–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-2166(92)90048-G

- Blythe, J., Gardner, R., Mushin, I., & Stirling, L. (2018). Tools of engagement: Selecting a next speaker in Australian aboriginal multiparty conversations. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 51(2), 145–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2018.1449441

- Boas, F., Yampolsky, H. B., & Harris, Z. S. (1947). Kwakiutl grammar with a glossary of the suffixes. American Philosophical Society.

- Borchmann, S. (2019). Non-spontaneous and communicative emotive interjections: – Ecological pragmatic observations. Scandinavian Studies in Language, 10(1), 7–40. https://doi.org/10.7146/sss.v10i1.114668

- Bradley, J., & Yanyuwa families (2010). Singing saltwater country: Journey to the songlines of Carpentaria. Allen & Unwin.

- Bybee, J. L., & Hopper, P. J. (eds.). (2001). Frequency and the emergence of linguistic structure (Vol. 45). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Couper-Kuhlen, E. (2012). On affectivity and preference in responses to rejection. Text & Talk, 32(4), 453–475. https://doi.org/10.1515/text-2012-0022

- Couper-Kuhlen, E., & Selting, M. (2018). Interactional linguistics: Studying language in social interaction. Cambridge University Press.

- Dahmen, J. (2022). Bilingual speech in Jaru-Kriol conversations: Codeswitching, codemixing, and grammatical fusion. International Journal of Bilingualism, 26(2), 198–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/13670069211036925

- Dahmen, J., Possemato, F., & Blythe, J. (2020). Jaru (Australia) – Language snapshot. Language Documentation and Description, 17, 142–149.

- de Dear, C., Possemato, F., & Blythe, J. (2020). Gija (East Kimberley, Western Australia) – Language snapshot. Language Documentation and Description, 17, 134–141.

- Dingemanse, M. (2023). Interjections (Oxford Handbook of Word Classes) [Preprint]. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/ngcrs.

- Du Bois, J. W. (2007). The stance triangle. In R. Englebretson (Ed.), Pragmatics & beyond new series (Vol. 164, pp. 139–182). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Ford, C. E., Fox, B. A., & Thompson, S. A. (1996). Practices in the construction of turns: The “TCU” revisited. Pragmatics, 6(3), 427–454.

- Ford, C. E., Fox, B. A., & Thompson, S. A. (2002). The language of turn and sequence. Oxford University Press.

- Gaby, A. (2017). A grammar of Kuuk Thaayorre. De Gruyter Mouton.

- Gaby, A., & Bradley, J. (2017). Yanyuwa emotive exclamations. Oral presentation. University of Sydney.

- Gardner, R. (2001). When listeners talk: Response tokens and listener stance. John Benjamins.

- Gilbert, P. (2010). The compassionate mind: A new approach to life’s challenges. Constable.

- Gilbert, P. (2017). Compassion. In P. Gilbert (Ed.), Compassion (1st ed., pp. 3–15). Routledge.

- Gilbert, P., Basran, J., MacArthur, M., & Kirby, J. N. (2019). Differences in the semantics of prosocial words: An exploration of compassion and kindness. Mindfulness, 10(11), 2259–2271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-019-01191-x

- Goffman, E. (1978). Response cries. Language, 54(4), 787–815. https://doi.org/10.2307/413235

- Haiman, J. (1994). Ritualization and the development of language. In W. Pagliuca (Ed.), Current issues in linguistic theory (Vol. 109, pp. 3–28). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Hepburn, A., & Bolden, G. (2017). Transcribing for social research. SAGE Publications.

- Heritage, J. (1984). A change-of-state token and aspects of its sequential placement. In J. Atkinson & J. Heritage (Eds.), Structures of social action: Studies in conversation analysis (pp. 299–345). Cambridge University Press.

- Heritage, J. (2011). Territories of knowledge, territories of experience: Empathic moments in interaction. In T. Stivers, L. Mondada, & J. Steensig (Eds.), The morality of knowledge in conversation (pp. 159–183). Cambridge University Press.

- Hill, R. (2019). Murrinhpatha noun classifiers: Syntax and discourse features. University of Melbourne.

- Hopper, P. J., & Traugott, E. C. (2003). Grammaticalization. Cambridge University Press.

- Hutchby, I., & Wooffitt, R. (1998). Conversation analysis: Principles, practices, and applications. Polity Press.

- Jakobson, R. (1971). Shifters, verbal categories, and the Russian verb. In Selected writings (Vol. ii, pp. 130–147). De Gruyter Mouton.

- Jefferson, G. (1984). Notes on a systematic deployment of the acknowledgement tokens “yeah”; and “Mm Hm”. Paper in Linguistics, 17(2), 197–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351818409389201

- Jefferson, G. (1988). On the sequential organization of troubles-talk in ordinary conversation. Social Problems (Berkeley, Calif.), 35(4), 418–441.

- Kofod, F., Bray, E., Peters, R., Blythe, J., & Crane, A. (2022). Gija dictionary. Aboriginal Studies Press.

- Lahaussois, A. (2016). Where have all the interjections gone? A look into the place of interjections in contemporary grammars of endangered languages. In C. Assunção, G. Fernandes, & R. Kemmler (Eds.), Tradition and innovation in the history of linguistics (pp. 186–195). Nodus Publikationen.

- Li, X. (2014). Multimodality, interaction and turn-taking in Mandarin conversation. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Mansfield, J. (2019). Murrinhpatha morphology and phonology. DeGruyter Mouton.

- Mushin, I. (2010). Code-switching as an interactional resource in Garrwa/Kriol talk-in-interaction. Australian Journal of Linguistics, 30(4), 471–496. https://doi.org/10.1080/07268602.2010.518556

- Mushin, I. (2012). A grammar of (Western) Garrwa. De Gruyter Mouton.

- Mushin, I. (2018). Diverging from ‘business as usual’: Turn-initial ngala in Garrwa conversation. In J. Heritage & M.-L. Sorjonen (Eds.), Between turn and sequence: Turn-initial particles across languages (Vol. 31, pp. 119–154). John Benjamins Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.1075/slsi.31.05mus

- Myers, F. (1986). Pintupi country, Pintupi self: Sentiment, place and politics among Western Desert Aborigines. Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Neely, K. (2019). The linguistic expression of affective stance in Yaminawa (Pano, Peru). University of California.

- Nübling, D. (2004). The prototypical interjection: A definition proposal. Zeithschrift fur Semiotik, 26(1-2), 11–45.

- Ochs, E., & Schieffelin, B. (1989). Language has a heart. Text - Interdisciplinary Journal for the Study of Discourse, 9(1), 7–25.

- Oxford English dictionary. (2000). Oxford University Press.

- Ponsonnet, M. (2018). Expressivity and performance. Expressing compassion and grief with a prosodic contour in Gunwinyguan languages (northern Australia). Journal of Pragmatics, 136, 79–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2018.08.009

- Ponsonnet, M. (2020). Difference and repetition in language shift to a creole: The expression of emotions. Routledge.

- Ponsonnet, M. (2023). Interjections. In C. Bowern (Ed.), Oxford guide to Australian languages (pp. 564–572). Oxford University Press.

- Reber, E. (2012). Affectivity in interaction: Sound objects in English. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Sacks, H., Schegloff, E. A., & Jefferson, G. (1974). A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language, 50(4), 696–735. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.1974.0010

- Selting, M. (2010). Affectivity in conversational storytelling: An analysis of displays of anger or indignation in complaint stories. Pragmatics, 20(2), 229–277.

- Sidnell, J. (2010). Conversation analysis: An introduction. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Tsunoda, T. (1981). The Djaru Language of Kimberley, Western Australia. Pacific Linguistics.

- Wilkins, D. P. (1992). Interjections as deictics. Journal of Pragmatics, 18(2–3), 119–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-2166(92)90049-H

- Williams, N., Stenzel, K., & Fox, B. (2020). Parsing particles in Wa’ikhana. Revista Linguíʃtica, 16(Esp.), 356–382. doi:10.31513/linguistica.2020.v16nEsp.a43715