ABSTRACT

An increasing number of professionals take on doctoral studies in order to advance their professional knowledge and develop their practice in line with academic practice. Many choose a thesis by publication. Using a mixed method approach, including data from the publishing process and autoethnographic narrative, this article explores one case of the publishing process for a professional doctoral student. The results show that the doctoral process when reconstructed is an overlapping process in which the professional combines academic and professional skills, moving from a professional doing research to a professional researcher. This space can be understood as a transformative or liminal space of creative opportunities in line with Van Gennep’s thoughts regarding rites of passage and liminal space. It is concluded that awareness of the doctoral publishing process may facilitate this process for doctoral students as well as supervisors.

Introduction

Interest in pursuing doctoral studies continues to increase among both students and professionals. Professionals in many fields take on doctoral education to advance their professional knowledge and to develop practice in line with academic standards. This move, from professional to doctoral student, places specific demands on doctoral education to be relocated into ‘learning spaces at the interface among academic, professional and workplace knowledges’ (Lee, Citation2011, p. 155). It involves both a ‘not-knowing’ and an ‘unlearning’ (Lee, Citation2011, p. 159) in an ambiguous and unstable learning space and which includes a transformation dynamic (Clegg & Gall, Citation1998). For the doctoral student entering academia directly from a profession, this could be described as becoming a new type of professional as a researching professional (cf. Bourner, Bowden, & Laing, Citation2001).

At the same time, the process of doctoral studies to become a researcher has changed. In the Swedish context, as internationally, the previous publishing process of writing a monograph has in many institutions shifted to thesis by publication, in which doctoral students are expected to write a number of scientific articles to be published in academic journals (cf. Aitchison, Kamler, & Lee, Citation2010; Bartkowski, Deem, & Ellison, Citation2015; Sharmini, Spronken-Smith, Golding, & Harland, Citation2015). Researchers report doctoral students’ publishing processes as a way to prepare them for their further careers in academia. This gives doctoral students the opportunity to practice the art of publishing articles (Boud & Lee, Citation2009), and can also be seen as an indicator of a continued pattern of publishing (Gray & Drew, Citation2008). Thus, producing scientific articles and a capstone, an extensive dissertation summary, can be regarded as a hybrid practice, performing both public and pedagogical functions (Lee, Citation2011). Further, it is possible that there is a gap in how doctoral programs are prepared to link these two functions.

Barnacle (Citation2005) argues that the process of doctoral education can be regarded as ‘fraught and difficult’ (p. 186) for doctoral students. This is perhaps reflected in the vast amount of handbooks for supervisors of doctoral students (cf. Bartkowski et al., Citation2015; Storey & Maughan, Citation2016; Wright, Murray, & Geale, Citation2007), including assessing theses by publication (cf. Sharmini et al., Citation2015; Wisker, Citation2012). Research also includes handbooks for doctoral students in writing (cf. Gray & Drew, Citation2008; Rocco & Hatcher, Citation2011; Stubb, Pyhältö, & Lonka, Citation2014), factors to support timely completion (Burman, Citation2017; Lindsay, Citation2015), concerns for doctoral students’ well-being (Acker & Haque, Citation2015; Pyhältö, Toom, Stubb, & Lonka, Citation2012) and the discontinuation of doctoral studies (Hunter & Devine, Citation2016). While there appears to be research reporting different aspects of doctoral studies from the doctoral student perspective (cf. Acker & Haque, Citation2015; Pyhältö et al., Citation2012; Stubb et al., Citation2014), there seems to be relatively little research in regard to the publishing process of doctoral students reflecting the voice of doctoral students themselves.

Robins and Kanowski (Citation2008) combine doctoral voice and the publishing process and discuss advantages and disadvantages of publishing for doctoral students. Here, time was seen to be problematic, as the time invested in the publishing process required that other academic activities were forfeited (Robins & Kanowski, Citation2008). Further, these researchers, based on the time restraints, discuss how perhaps publishing some of the articles would be a more practical alternative. Knowing when to publish can also be a concern for doctoral students. Paré (Citation2010) reports issues regarding publishing too early and related quality issues. Thus, the shift from academic writing in monographs to thesis by publication, while at the same time, the number of doctoral students in the publishing process has most likely increased (cf. Gray & Drew, Citation2008). For a new doctoral student, it may be difficult to know what to expect of the publishing process. A major part of the publication process is writing (Jönsson, Citation2006; Rocco & Hatcher, Citation2011). There is most likely the need for help and support in the academic writing process (cf. Paré, Citation2010). Murray (Citation2010) describes this as learning to know one’s audience or learning to be rhetorical. It is possible that doctoral students have the view of the writing process as a linear process and are not aware of the time and conditions involved in the publishing process. Therefore, the conditions for timely completion may be one aspect, which adds to frustration and difficulties in the publishing process (Barnacle, Citation2005).

In considering how to best describe the doctoral publishing process and how this process can be reconstructed and understood, several lines of thought have been considered. It is possible to see this process as becoming (cf. Barnacle & Mewburn, Citation2010; Coryell, Wagner, Clark, & Stuessy, Citation2013; Ennals, Fortune, Williams, & D'Cruz, Citation2016; Hart & Montague, Citation2015; Lee, Citation2011) or perhaps as transformative, according to Coleman, Collings, and McDonald (Citation1999). Another perspective would be that with the base of professional knowledge from the field, the doctoral student seeks to take on a new space of learning within academia and a new space is created, that is, the third space (Bhabha, Citation1994). However, in this intersection between professional knowledge and academic knowledge, there would perhaps be too much focus on the space, instead of the individual himself. If considered as a process of transition in which the individual moves from one stage to the next, this process can perhaps be interpreted in terms of rites of passage (Van Gennep, Citation1960). The rites of passage can be described as three stages: separation, liminality as the state of the in-between and incorporation as the last stage, according to Van Gennep (Citation1960). The first stage describes the separation between the old and the new, for example, when the professional leaves his profession to begin doctoral studies to become a researcher. The final stage is the stage of incorporation in which the professional has attained the status of the researcher. In this article, the liminal stage, the stage of the in-between, is seen as the stage in which the individual combines the old and the new and prepares to be incorporated in the academic world.

In this liminal space, there are certain concepts, or learning experiences, which resemble passing through a portal, from which a new perspective opens up, allowing things formerly not perceived to come into view (Meyer & Land, Citation2003; Meyer, Land, & Baillie, Citation2010). This liminal space, in which the learning is suspended and may, although perhaps exhilarating, be seen to be unsettling with a feeling of uncertainty or loss (Meyer & Land, Citation2003). In the transitional passage, threshold concepts, that is, specific strategies may be needed for supporting doctoral students to help them move forward from stuck to unstuck (Kiley, Citation2009). Rowbottom (Citation2007) seeks to demystify threshold concepts, stating that they are difficult to define and cannot be regarded as abilities. Moreover, these threshold concepts are described as extrinsic, that is, they are most likely different for different students (Rowbottom, Citation2007). Nevertheless, the liminal space remains of interest to study.

Aim and research questions

The objective of this article is to study one specific case of a doctoral publishing process from professional to researcher through exploring the publishing process of the four articles and the capstone, or extensive dissertation summary. The following questions are put forth: (1) How can the doctoral publishing process be described? and (2) How can this process be reconstructed and understood as a liminal space according to Van Gennep (Citation1960) for the researching professional? This article aspires to contribute with knowledge regarding how the professional takes on the role of a professional researcher, contributing to insights into the transition into a new and creative space in liminality.

Context

The context of this study is a four-year doctoral program comprising 240 European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System (ECTS) at a university in Sweden. In the Swedish context, doctoral education is often a period of four years, however, teaching responsibilities may prolong this period of time up to five years. Composed of 240 ECTS, this specific program included coursework of 90 ECTS, of which 37.5 ECTS were mandatory in the form of basic education courses required for becoming a researcher. The remaining 150 ECTS comprised the publishing process of the thesis. This often involves writing a number of scientific articles as well as a capstone (cf. Hamilton & Weiner, Citation2011). Although the number of articles may vary, in this case, four articles were to be written as well as the capstone. Initially, this process is often described as somewhat linear, which involves moving from one article to the next and further to the capstone, as illustrated in .

Although the demands on publications vary between different universities and between the institutions at the university, this case involved the publication process of a thesis, which included four published articles, and the doctoral work was completed over a period of four years. As this study will employ personal narrative as a form of auto-ethnography (Muncey, Citation2010) and reflexivity (MacMillan, Citation2003) to gain insight into the research questions posed, a few words about the author are perhaps in place. Having a background in banking and finance, the author of this article became a doctoral student after some 13 years’ experience as a teacher in compulsory school. Thus, the author was a professional with hopes that doctoral studies would involve both a personal challenge and professional development (cf. Guerin, Jayatilaka, & Ranasinghe, Citation2015; Leonard, Becker, & Coate, Citation2005).

Method

In this study, the questions were explored using a case study approach (Simons, Citation2009; Yin, Citation2009), involving what can be described as an auto-ethnographically inspired (Muncey, Citation2010) and mixed method design, involving qualitative and quantitative data (cf. Bryman, Citation2008; Hammersley & Atkinson, Citation2007). Quantitative data such as statistics regarding publishing periods in days were used to reconstruct the publishing process. This information has been gained through the study of correspondence with the editors and reviewers of the journals. The qualitative element comprised quotations from documents and correspondence with editors and reviewers. Further, reflective auto-ethnographic narrative (Muncey, Citation2010) was used to further deepen the knowledge of the publishing process related to these quotations. These narratives were written when the data for each article and the capstone was compiled, as the author, through the study of these materials, relived and reconstructed the publishing process in order to reflect upon the reflexivity in the process (MacMillan, Citation2003).

As in all writing processes, it is difficult to measure the beginning and the end of a writing process, with this perhaps instead being an overlapping and expanding process as recursive through revision (cf. Flower & Hayes, Citation1981; Jönsson, Citation2006). Thus, the starting point for the articles has been set approximately one week after the final revisions of the preceding manuscript. Although this may not give a completely correct picture of the publishing process for the article, it hopefully provides a sufficient picture of the overall process. The final date for each respective article has been set when the author has submitted the final revisions, when these revisions have no longer required work by the author. In all of the publications, when revisions were required, the author complied with these revision dates. This means that the author was not responsible for delays in the publishing process. In summary, the publishing time involved the starting time, including submission, review and revision work until the final submission, until more work by the author was no longer required. Both the author and the supervisors made the choice of the journals. In two cases, the supervisors suggested journal issues which were especially well suited for the articles. The three other journals were identified and suggested by the author, and chosen in consultation with the supervisors. While acknowledging the strong support of the supervisors, co-authorship was not considered as an alternative.

Regarding ethical considerations, it is important to note that the results presented in this study are in no way to be regarded as a negative reflection on either the editors’ or the reviewers’ work with the included articles. The suggestions and comments that the editors and the reviewers have provided concerning the manuscripts in this study have had a strong impact and have both substantially developed and improved the articles.

Results

In this section, the results are presented for each article and the capstone, according to the order of publication. The publishing process of the articles was a total of 1419 days or 3.97 years in total. The distribution between the articles is presented in .

Table 1. Publishing process in days for Articles 1–5 and the capstone.

Article 1

This article had a publishing time of 11.4 months. The submission notification was sent within a few days and the reviews for the article were received back within about four months. The revisions of the article were described as minor. A revised manuscript and a cover letter were submitted: ‘Included is the new version of my text as well as my letter regarding how I have dealt with the comments. Many thanks for your help in this process’. Notification was received from the editors: ‘We have now received the reviews from our two referees, who are very positive about your article. Based on their comments, your article will be published’. From the perspective of the author, the contact with the journal through the editors could be described as smooth and flexible. The length of the publishing process for this article is mainly related to the article being included in a special issue, with the editors having planned ahead of time in order to meet deadlines without delay.

The following reflection summarizes the publishing of the article according to the author:

This was my first article. At this point, I was so incredibly relieved that my article was going to be published. It was a milestone in my doctoral process and perhaps the first realization that I could actually somewhere along the line complete my doctoral studies. Some of the comments from the editor were very basic, for example, inconsequent referencing, which although, they were at the time somewhat embarrassing, were of great help in my future work.

Article 2

This article had a review time of 4.5 months. The notification of submission was received immediately through the submission system as well as notification from the editor one day later: ‘Thank for submitting your manuscript … With the online journal management system that we are using you will be able to track its progress through the editorial process’. Following a review time of 65 days, a revised manuscript was submitted. This included a cover letter: ‘Many thanks to both reviewers for rigorous reviews. All of their suggestions have been of great help and have hopefully resulted in a clearly improved manuscript’. For this article, the reviewers did not agree. This article could not be published in line with the journal’s policy requiring the ‘unconditional consent of the reviewers’. From the perspective of the author, the publishing process of this article was relative as the article was not published, and the publishing process was restarted with a new journal.

The following reflection summarizes the publishing of the article according to the author:

When I think about it, I went into this publishing process strengthened by the first article being published. I had been to a conference in my research area and the organizers of the conference suggested submitting articles to this journal. I saw this as a wise and suitable choice of journal. For me, the publishing process of this article was a very difficult experience. It had never occurred to me that two or three reviewers could have such different opinions of a text. One said average and one said excellent! And the journal required that the reviewers were in consent, which took a while for me to realize, that in my case, this was impossible. I felt that my writing had developed considerably and that this article was just so much better than the first. I was very lucky that I had supportive and professional supervisors.

Article 3

The publishing process for this article was a total of 11.9 months. This process was characterized by relatively long periods of time for reviewers’ reviews, questions and updates on the process of the article:

I am sorry that this has taken a long time for this response. There has been some disagreement among the reviewers, however, we have chosen to collect a number of these now, in order for you to be able to revise the text in a manner in which the reviewers can agree that the text has been improved and ready for publishing.

The reply to this manuscript involved the length of the manuscript: ‘We hereby want to inform you that your article has extended 40,000 characters in the last version and is now over 60,000 characters. It needs to be reduced according to our guidelines’.

In order to meet these guidelines the manuscript was further revised and submitted:

Enclosed, please find the latest version of my manuscript in line with your recommendations. In this work, I have mainly shortened and sharpened the introduction and literature review. Repetitive parts of the text have been located and removed throughout the manuscript, certain quotations have been shortened and the discussion has been clarified.

The following reflection summarizes the publishing of the article according to the author:

Somewhere along the line, I found the energy to rip up my rejected manuscript and start all over again. I went literally back to the drawing board and started all over. I reviewed all of my data again. What could be changed, what could be done better, what had I missed? I rebuilt the text from scratch. It was difficult to start all over again, but I think it was probably the best learning process in my doctoral studies, because it gave me the opportunity to see that I could organize my manuscript in an alternative manner. There were revisions and revisions and revisions. I added more and more according to what the reviewers asked for. Finally, they were happy, but my manuscript was too long. It was hard work. But as I revised and edited, I could see the manuscript becoming better and better.

Article 4

This article had a publishing process of 9.1 months. When the article was submitted, a notification letter was sent, informing of the review time:

Thank you very much for submitting your manuscript. Your manuscript will now be sent for review. Reviews are usually completed in 8 to 10 weeks. You will be contacted when the review results have been received. We appreciate your time and effort.

The following reflection summarizes the publishing of the article according to the author:

At this point in time during my doctoral process, I had written quite a lot and felt that I finally understood what I was doing in my doctoral project as a whole. The pieces were finally coming together and this sense helped me to put a lot of energy into my writing. It is most likely that this was reflected in my writing and facilitated this publishing process and my contacts with this journal.

Article 5

The publishing process for this article was a total of 10.7 months. The acceptance of the abstract was received within one day. The submission process for the full article was prolonged with 13 days. The reviews from the editors and the reviewers were short and concise, for example, suggestions for headings, conclusions and practical implications. From the perspective of the author, the publishing process of this article was relatively fast. The contact with the editors was characterized by quick replies to questions for continued work. The final revisions were completed within one or two days.

The following reflection summarizes the publishing of the article according to the author:

This was my final article in my dissertation. During my whole period of doctoral studies, there had been a continual conversation among the doctoral students regarding how many published articles you needed to have in a thesis. No one really wanted to answer this question straight out. Somewhere along the line someone said that it was possible to have three published articles and one manuscript. The pressure lifted, when I realized that I would do fine if this article was just submitted or even accepted. My work with this article was perhaps the most interesting, and well, the most fun. I enjoyed writing it and it felt good to send it off to the editor. I remember this very clearly, because feeling so good about the publishing process of this article, helped me in the next step. I started writing my capstone within a week.

The capstone

The writing of the capstone took some 5.8 months. As the process was an internal university process, it involved intensive work for both the doctoral student and the supervisors. The time period also included a final seminar in which the text was read by an external reader and the consequent revisions. A final version was sent for printing and a preliminary book was printed. A period of three days was allowed for revisions in the book, upon which the whole process was repeated and which concluded the printing process. This became the final version of the book.

The following reflection summarizes the writing process of the capstone according to the author:

Once again the writing started. I started right off and realized that the writing of the capstone involved starting all over again. Back to the concrete work of the literature review and at the same time trying to figure how to fit it all together. I have very few memories of this period of time, probably because of stress, but mainly because I felt totally immersed in the work. All of the things I had learned along the way about writing articles felt irrelevant. The capstone was something completely different to write! It was inspiring, fun and hard work. I think that my supervisors were very happy when I submitted the final version for printing. They were happy not to have to read any more of my texts.

Results in summary

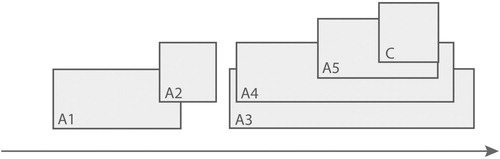

In summary, when the result of the publishing process is reconstructed into days and months per article, the results of this study can be represented as in .

Through this reconstruction, an actual picture of the publishing process is illustrated as a liminal process over time. This illustration could be said to comprise a number of stages or liminal processes over time and with overlaps.

When reconstructing the publishing process based on the reflexive narrative, progression as well as liminal transitions can be seen. In Article 1, the author describes the publishing process in terms of a relief and in some aspects somewhat embarrassing. This liminal transition could perhaps be described as a first troublesome encounter with the publishing process. Moving on to Article 2, the author comes to terms with rejection as a difficult experience and at the same time feeling an improvement in writing skills. This liminal transition involves both positive and negative aspects. Finding the energy to revise, taking on the work with rewriting and revising as well as being able to reflect upon improvement in their own work characterized the liminal transition of Article 3. Article 4 can perhaps be best described as the author having come to an understanding of the writing process and the publishing process, finding a liminal space and applying this energy to continued writing. Finally, the publishing process with Article 5 can be seen as lifted pressure, as a space for writing and learning as a positive experience and liminal transition.

Discussion

Through this reconstruction, an actual picture of the publishing process can be regarded as one specific case (Simons, Citation2009; Yin, Citation2009) of the doctoral publishing process. As noted above, the publishing process of the articles in this dissertation totaled 3.97 years, which can be compared to the actual period of the doctoral studies, which was four years. Although there were many periods in this publishing process which were relatively free to pursue other tasks related to the doctoral work such as course work, meetings, meetings with supervisors, revision work and conferences, the publishing time and time for doctoral studies are almost the same, 3.97 and 4 years respectively. It is perhaps expected of a doctoral student to have several articles and manuscripts in process, but it may be helpful for the doctoral student to be aware of alternative and individual versions of this liminal process. As the work with the capstone is linked to the publishing period, this amount of time for the publishing process is perhaps too comprehensive and too late in the process. Knowledge of what the publishing process actually looks like, as in this study, which is far from the linear process initially presented, but rather a series of liminal spaces, would perhaps have facilitated and supported this professional as a doctoral student.

Although the element of time for the publishing process is problematic for researchers as a whole, it is perhaps more problematic for doctoral students with a set period of time for their doctoral studies (Robins & Kanowski, Citation2008). There is no question that supervisors do their absolute best to help and support doctoral students through these liminal spaces. However, it is possible that support is needed for both doctoral students and supervisors when submitted manuscripts are rejected or when major revisions are necessary. This support is most likely an important experience for all doctoral students in regard to future work and a necessary liminal transition.

It is important to note that the results of this study should not be regarded as a negative reflection on either the work of the editors or the reviewers. The process of peer-review is the most common use of quality control for academic texts, and this work should be expected to take time (Ferreira et al., Citation2015; Kassirer & Campion, Citation1994). This quality control of texts, although perhaps not always optimal, is nevertheless the best possible process available at this time (Cusick, Citation2016; Nicholas et al., Citation2015) and is an important liminal transition to learn. From the perspective of a doctoral student, supervisors need to state clearly that comments from reviewers when an article is not published, as in this study, may facilitate and shorten the next round of reviews with the next journal, that is, the work done in one liminal space may support the process in the next. It is difficult to say how the time lost in the publishing process affects the doctoral student’s writing process, publishing process and studies overall. This process, when seen as a liminal space is troublesome and one in which the doctoral student takes on reviewer critique, is most likely an important experience and transition.

As seen in this study, the process of publishing the articles in this dissertation process took a relatively long period of time and was unevenly distributed. It is difficult to say if these reviewers and editors themselves could have hastened the publishing process. In this study, deadlines for revisions were respected. It is difficult to see if the doctoral student could have produced the manuscripts in a shorter period of time, and shortened these difficult liminal transitions.

Taking on doctoral studies is an opportunity to learn and reflect on the process of learning the trade of researching and finding a liminal space, in which knowledge from the profession and academia are combined. What may be considered to be problematic for the doctoral student, is that while it is possible to plan coursework and teaching responsibilities, the time needed for the peer review (Cusick, Citation2016; Ferreira et al., Citation2015; Kassirer & Campion, Citation1994; Nicholas et al., Citation2015) and publishing process of articles in journals is beyond the control of supervisors, institutions and universities. In regard to well-being (Burman, Citation2017; Pyhältö et al., Citation2012), this may be stressful for doctoral students, perhaps especially for a professional who is used to planning their own time. Further, as noted above, the effects on the writing process is difficult to foresee. Long delays from journals may make work with manuscripts more drawn out, with an extended time in the in-between liminal space. This, in turn, may cause difficulties related to timely completion (Lindsay, Citation2015).

It is important that doctoral students quickly become aware of the format of doctoral studies and the publishing process in order to widen their understanding of the process beyond the linear view which is often presented. This is also true for the supervisors involved in the process. This awareness may lead to stronger supervision and support for students during the doctoral process. Stress among doctoral students is noted in the literature (Acker & Haque, Citation2015; Burman, Citation2017), and this awareness for both students and supervisors may help in providing an alternative non-linear picture of what may be expected in the doctoral process and understanding this alternative liminal picture may also be a factor in reducing this stress. This is most likely also an important aspect to be targeted by Academic Development Departments at universities in charge of providing training for doctoral supervisors.

Finally, another interesting question to study is the possibility of shortening this publishing process. One issue is if it would be possible to shorten the publishing time through a course in academic writing as a part of the doctoral process. Researching professionals as doctoral students may have not studied or taken on academic projects for a long period of time, or written scientific articles previously. It is true that many supervisors are expected to instruct doctoral students in these skills. Nevertheless, it is important that doctoral students are prepared for writing in this genre, as well as later in their doctoral studies when then they are expected to quickly leave this genre and undertake the writing of the capstone.

The publishing process is an overlapping process in which the professional learns about the academic process and slowly creates a new space of using both professional knowledge and academic knowledge. These involve all of the elements of academic publishing including both positive and negative experiences, that is, acceptance and rejection, which are of importance in continued work in academia. The opportunities within this space can be interpreted as a liminal space (Van Gennep, Citation1960). As noted in the narrative, there is progression and transition from relief in being published with somewhat embarrassing mistakes through to hard work considered to be fraught and difficult (Barnacle, Citation2005), and gaining troublesome knowledge (Meyer & Land, Citation2003). In the end, when professional and academic skills are combined, a liminal space of opportunity and new energy is created, which leaves the author with a space for creative writing in which writing is a positive experience.

Discussion in summary and practical implications

In returning to the research questions (1) How can the doctoral publishing process be described? and (2) How can this process be reconstructed and understood as a liminal space (Van Gennep, Citation1960) for the researching professional? the doctoral process can be described as fraught and difficult (Barnacle, Citation2005) as well as stressful. It can also be described as rewarding, as it is a process of learning. The doctoral publishing process, in this study, also involves prolonged periods of time in a liminal space in which the publishing process cannot be influenced. Neither the doctoral student nor the supervisors own the publishing process. When reconstructed, the publishing process can be seen as far from linear as often presented. Instead, it can be seen as an overlapping process in liminal transition, or perhaps liminal transitions. It is difficult to see any relationship between the liminal transitions, which take place through the publishing time, the writing process and the order of the articles. However, the publishing process can be seen as a progression as the doctoral student in line with Van Gennep (Citation1960) as a liminal space, in which professional researcher and academic writing and publishing skills are combined. This progress can be understood as the researching professional passing through a liminal space and becoming a professional researcher.

Based on the results of this study and this discussion the following practical implications may be of interest to consider. First, it is important that supervisors inform doctoral students that the publishing process takes time, cannot be influenced and is most likely non-linear, liminal and highly individual. Secondly, Academic Development units at universities can help to provide awareness regarding this information in courses for supervisors, as well as how to support researching professionals and doctoral students whose well-being may be affected by this process. Thirdly, courses in academic writing should be provided for doctoral students as an important part of doctoral studies. If academic writing skills are acquired early in the process of doctoral studies, it is most likely that these skills will facilitate and support professionals to merge professional and academic skills and more easily navigate through this creative process as a liminal space.

Future research

As more and more professionals take on doctoral studies to advance and develop their profession, it is of interest to study how these researching professionals continue their work in practice when their doctoral studies are completed. How are the skills, which are acquired during the doctoral process, supported outside of academia? How can skills such as research methods involving systematic investigation, documentation and evaluation be used to increase quality in these areas in professional workplaces? Another interesting question for future research is how academia can teach the academic process of conducting research and academic writing as well as valuing and learning from the skills and competences of researching professionals.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

ORCID

Marcia Håkansson Lindqvist http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9557-2164

References

- Acker, S., & Haque, E. (2015). The struggle to make sense of doctoral study. Higher Education Research & Development, 34(2), 229–241. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2014.956699

- Aitchison, C., Kamler, B., & Lee, A. (Eds.). (2010). Publishing pedagogies for the doctorate and beyond. London: Routledge.

- Barnacle, R. (2005). Research education ontologies: Exploring doctoral becoming. Higher Education Research & Development, 24(2), 179–188. doi: 10.1080/07294360500062995

- Barnacle, R., & Mewburn, I. (2010). Learning networks and the journey of ‘becoming doctor’. Studies in Higher Education, 35, 433–444. doi: 10.1080/03075070903131214

- Bartkowski, J. P., Deem, C. S., & Ellison, C. G. (2015). Publishing in academic journals: Strategic advice for doctoral students and academic mentors. The American Sociologist, 46(1), 99–115. doi: 10.1007/s12108-014-9248-3

- Bhabha, H. (1994). The location of culture. London: Routledge.

- Boud, D., & Lee, A. (2009). Changing practices of doctoral education. Oxford: Routledge.

- Bourner, T., Bowden, R., & Laing, S. (2001). Professional doctorates in England. Studies in Higher Education, 26(19), 65–83. doi: 10.1080/03075070124819

- Bryman, A. (2008). Social research methods (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Burman, Å. (2017). Bli klar i tid – och må bra på vägen. Handbok för doktorander [Finish on time – and feel good along the way. Handbook for doctoral students]. Stockholm: Natur & Kultur.

- Clegg, S., & Gall, I. (1998). The discourse of research degrees supervision: A case study of supervisor training. Higher Education Research & Development, 17(3), 323–332. doi: 10.1080/0729436980170305

- Coleman, M., Collings, M., & McDonald, P. (1999). Teaching anti-oppressive practice on the diploma in social work: Integrating learning. Social Work Education: The International Journal, 18(3), 297–309. doi: 10.1080/02615479911220291

- Coryell, J. E., Wagner, S., Clark, M. C., & Stuessy, C. (2013). Becoming real: Adult student impressions of developing an educational researcher identity. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 37(3), 367–383. doi: 10.1080/0309877X.2011.645456

- Cusick, A. (2016). Peer review: Least-worst approach or the very best we can do? Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 63(1), 1–4. doi: 10.1111/1440-1630.12281

- Ennals, P., Fortune, T., Williams, A., & D’Cruz, K. (2016). Shifting occupational identity: Doing, being, becoming and belonging in the academy. Higher Education Research & Development, 35(3), 433–446. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2015.1107884

- Ferreira, C., Bastille-Rousseau, G., Bennett, A. M., Ellington, E. H., Terwissen, C., Austin, C., … Murray, D. (2016). The evolution of peer review as a basis for scientific publication. Directional selection towards a robust discipline? Biological Reviews, 91(3), 597–610. doi: 10.1111/brv.12185

- Flower, L., & Hayes, J. R. (1981). A cognitive process theory of writing. College Composition and Communication, 32(4), 365–387. doi: 10.2307/356600

- Gray, P., & Drew, D. (2008). What they didn’t teach you in graduate school. 199 helpful hints for success in your academic career. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing.

- Guerin, C., Jayatilaka, A., & Ranasinghe, D. (2015). Why start a higher degree by research? An exploratory factor analysis of motivations to undertake doctoral studies. Higher Education Research & Development, 34(1), 89–104. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2014.934663

- Hamilton, D., & Weiner, G. (2011). Dancing at the edge: Writing for the academic marketplace. Education Inquiry, 2(2), 251–262. doi: 10.3402/edui.v2i2.21978

- Hammersley, M., & Atkinson, P. (2007). Ethnography: Principles in practice (3rd ed.). London: Routledge.

- Hart, A., & Montague, J. (2015). ‘The constant state of becoming’: Power, identity, and discomfort on the anti-oppressive learning journey. Journal of Psychological Issues in Organizational Culture, 5(4), 39–52. doi: 10.1002/jpoc.21159

- Hunter, K. H., & Devine, K. (2016). Doctoral students’ emotional exhaustion and intentions to leave academia. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 11, 35–61. doi: 10.28945/3396

- Jönsson, S. (2006). On academic writing. European Business Review, 18(6), 479–490. doi: 10.1108/09555340610711102

- Kassirer, J. P., & Campion, E. W. (1994). Peer review: Crude and understudied, but indispensable. Jama, 272(2), 96–97. doi: 10.1001/jama.1994.03520020022005

- Kiley, M. (2009). Identifying threshold concepts and proposing strategies to support doctoral candidates. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 46(2), 293–304. doi: 10.1080/14703290903069001

- Lee, A. (2011). Professional practice and doctoral education: Becoming a researcher. In L. Scanlon (Ed.), ‘Becoming’ a professional (pp. 153–169). Dordrecht: Springer.

- Leonard, D., Becker, R., & Coate, K. (2005). To prove myself at the highest level: The benefits of doctoral study. Higher Education Research & Development, 24(2), 135–149. doi: 10.1080/07294360500062904

- Lindsay, S. (2015). What works for doctoral students in completing their thesis? Teaching in Higher Education, 20(2), 183–196. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2014.974025

- MacMillan, K. (2003). The next turn: Reflexively analyzing reflective research. In L. Finlay & B. Gough (Eds.), Reflexivity: A practical guide for researchers in health and social sciences (pp. 231–250). Oxford: Blackwell.

- Meyer, J. H. F., & Land, R. (2003). Threshold concepts and troublesome knowledge: Linkages to ways of thinking and practising within the disciplines. In C. Rust (Ed.), Improving student learning: Improving student learning theory and practice – ten years on. Oxford: Oxford Centre for Staff and Learning Development. Retrieved June 5, 2018 from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.476.3389&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- Meyer, J. H. F., Land, R., & Baillie, C. (2010). Threshold concepts and transformational learning. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Muncey, T. (2010). Creating autoethnographies. London: Sage.

- Murray, R. (2010). Becoming rhetorical. In C. Aitchison, B. Kamler, & A. Lee (Eds.), Publishing pedagogies for the doctorate and beyond (pp. 101–116). London: Routledge.

- Nicholas, D., Watkinson, A., Jamali, H. R., Herman, E., Tenopir, C., Volentine, R., … Levine, K. (2015). Peer review: Still king in the digital age. Learned Publishing, 28(1), 15–21. doi: 10.1087/20150104

- Paré, A. (2010). Slow the presses: Concerns about premature publishing. In C. Aitchison, B. Kamler, & A. Lee (Eds.), Publishing pedagogies for the doctorate and beyond (pp. 30–46). London: Routledge.

- Pyhältö, K., Toom, A., Stubb, J., & Lonka, K. (2012). Challenges of becoming a scholar: A study of doctoral students’ problems and well-being. ISRN Education, 2012, 1–12. doi: 10.5402/2012/934941

- Robins, L., & Kanowski, P. (2008). Phd by publication: A student’s perspective. Journal of Research Practice, 4(2), Article M3. Retrieved from http://jrp.icaap.org/index.php/jrp/article/view/136/154

- Rocco, T. S., & Hatcher, T. G. (2011). The handbook of scholarly writing and publishing. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Rowbottom, D. P. (2007). Demystifying threshold concepts. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 41, 263–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9752.2007.00554.x

- Sharmini, S., Spronken-Smith, R., Golding, C., & Harland, T. (2015). Assessing the doctoral thesis when it includes published work. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 40(1), 89–102. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2014.888535

- Simons, H. (2009). Case study research in practice. London: SAGE.

- Storey, V. A., & Maughan, B. D. (2016). Dissertation in practice: Reconceptualizing the nature and role of the practitioner-scholar. In International perspectives on designing professional practice doctorates (pp. 213–232). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Stubb, J., Pyhältö, K., & Lonka, K. (2014). Conceptions of research: The doctoral student experience in three domains. Studies in Higher Education, 39(2), 251–264. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2011.651449

- Van Gennep, A. (1960). The rites of passage. London: Routledge.

- Wisker, G. (2012). The good supervisor: Supervising postgraduate and undergraduate research for doctoral theses and dissertations. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Wright, A., Murray, J. P., & Geale, P. (2007). A phenomenographic study of what it means to supervise doctoral students. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 6, 458–474. doi: 10.5465/amle.2007.27694946

- Yin, R. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods (4th ed.). London: SAGE.