ABSTRACT

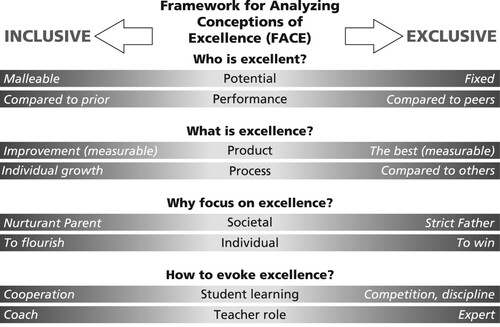

Honors programs and similar initiatives aimed at evoking excellence of students are increasingly promoted in higher education. However, there is a lack of conceptual clarity with regard to the concept of ‘student excellence’. The purpose of this article is to present a conceptual framework, called FACE (Framework for Analyzing Conceptions of Excellence), which provides a reflective tool for analyzing ideas on who is excellent, what is student excellence, why is student excellence important, and how is excellence taught. The content of FACE is based on literature on giftedness, motivation and excellence in higher education. FACE consists of a horizontal axis with inclusive and exclusive views at the extremes, and vertically distinguishes between possible answers to the ‘who’-, ‘what’-, ‘why’- and ‘how’-questions. FACE as a reflective tool can facilitate constructive debate among teachers that work together to develop educational programs aimed at evoking excellence of students.

Introduction

Initiatives aimed at evoking excellence of students in higher education, such as honors programs, have increased both in Europe and worldwide (Allan, Citation2011; Long & Mullins, Citation2012; Wolfensberger, Citation2015). These programs are designed for students who are willing and able to do more than their regular education program offers, and they offer these highly able and motivated students a challenging learning environment (Kool et al., Citation2017; Scager et al., Citation2014; Wolfensberger, Citation2015).

However, there is a lack of conceptual clarity about what excellence of students (or ‘student excellence’ for short) means (Mudrak et al., Citation2019). Different conceptions can lead to conflicting educational views of teachers about what students need and how to teach them in order to reach their full potential (Castejón et al., Citation2016; Millward et al., Citation2016). This may cause confusion or controversy between teachers who aim at designing and implementing programs that focus on evoking excellence in students (Astin & Antonio, Citation2012).

Conceptions of ‘student excellence’ are part of the broader conceptions of students and their learning that teachers have. These conceptions have an impact on the way they teach (e.g., Sagy et al., Citation2018; Trigwell et al., Citation1999), and are part of specific teaching and learning cultures (Sagy et al., Citation2019; Wood & Su, Citation2017). Therefore, we will explore conceptions of ‘student excellence’ in the context of teaching and learning cultures in higher education (Sagy et al., Citation2018, Citation2019).

When analyzing conceptions of ‘student excellence’, it is therefore not enough to focus on characteristics of excellent students (which is addressed by the question who is excellent?), but should also include aspects related to the educational settings aimed at evoking excellence. Three additional questions (what does excellence of students mean? why is excellence of students important? and how is excellence taught?) account for this context. Thus, when we refer to ‘conceptions of student excellence’, we refer to the combination of these four guiding questions.

FACE: framework for analyzing conceptions of excellence

The purpose of this article is to present a conceptual framework, called FACE (Framework for Analyzing Conceptions of Excellence). FACE is not intended as a quality assessment framework such as the Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF) in the UK, which is an instrument to assess teacher quality (Lubicz-Nawrocka & Bunting, Citation2019; O’Leary & Cui, Citation2018). Instead, FACE can be used as a reflective tool by both teachers and students to make conceptions of ‘student excellence’ explicit. As a result, FACE can enhance teachers’ reflective practice and facilitate constructive debate in teacher teams that are working on educational programs that aim to evoke excellence in students.

Developing the structure of FACE

As suggested above, ‘student excellence’ is an ambiguous and inherently contested concept. We propose that the ambiguity is best characterized by a distinction between inclusive and exclusive views on excellence, which apply to each of the four guiding questions related to ‘student excellence’. In general, to excel means ‘to be superior to, surpass in accomplishment or achievement’ (Merriam Webster, Citation2018). Therefore, identifying something as excellent follows from a comparison: better than others, better than norms, or better than previous performance (Brusoni et al., Citation2014). When excellence of students is referred to as a mark of distinction, it is exclusive: not everybody can attain it. However, when referring to prior individual achievements, student excellence becomes inclusive: everyone can strive for excellence by improving their performance or attitude (Laine et al., Citation2016; Mintrom, Citation2014; Stewart, Citation2010).

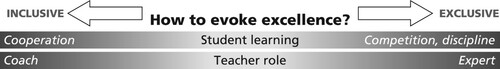

That is why FACE consists of a horizontal axis that distinguishes between inclusive and exclusive views on ‘student excellence’. The vertical axis in FACE presents the guiding questions that identify the central elements of conceptions of ‘student excellence’. These questions guide in analyzing these conceptions in a concrete educational setting. The guiding questions are: (1) who is (an) excellent (student), (2) what is excellence of students, (3) why should higher education focus on evoking excellence in students, and (4) how can excellence in students be promoted, evoked or taught? We work out a collection of possible answers to these questions. Answers to these questions are interrelated and in their mutual connection form specific conceptions of ‘student excellence’.

We build the conceptual content of FACE – the answers to the four guiding questions in the inclusive–exclusive spectrum – by making use of different strands of literature that all deal with the development of learning potential towards excellence (Mudrak et al., Citation2019). We combine insights coming from literature on student excellence in higher education (e.g., Brusoni et al., Citation2014; Joosten, Citation2014; Scager et al., Citation2013), theories on giftedness (e.g., Gagné, Citation2004; Harder et al., Citation2014; Heller, Citation2012; Sternberg, Citation2003), and theories of motivation (e.g., Dweck, Citation2012; Laine et al., Citation2016; Maehr & Zusho, Citation2009; Pullen et al., Citation2018). These different strands of literature provide various ideas regarding ‘student excellence’, which we have interpreted as possible answers to the four guiding questions and located on the inclusive–exclusive axis in FACE.

Based on our analysis of this literature, we have made more refined conceptual distinctions regarding the four guiding questions: between ‘potential’ and ‘performance’ in relation to ‘who is excellent?’; between ‘product’ and ‘process’ regarding ‘what is excellent?’; between ‘societal’ versus ‘personal’ perspective regarding ‘why focus on excellence?’; and between the roles of ‘student’ and ‘teacher’ regarding ‘how to evoke excellence?’ In this way, we categorized and structured the many different and often contradictory ideas about ‘student excellence’, filling the entire framework with conceptual content (see ).

FACE as a reflective tool within teaching and learning cultures

Several authors have proposed that different conceptions of student excellence relate to differences in personal beliefs, values and norms (Brusoni et al., Citation2014; Gan & Geertsema, Citation2018; Mintrom, Citation2014; Wood & Su, Citation2017). These beliefs, values and norms, although not always made explicit, influence how teachers shape their teaching and how students evaluate their learning (Cross & Cross, Citation2005; Dai & Chen, Citation2013). More generally, beliefs, values and norms form teaching and learning cultures (Gan & Geertsema, Citation2018), which influence educational practices, both on an individual and on a collective level (Maslowski, Citation2006).

Sagy et al. (Citation2019, p. 850) define teaching and learning cultures as: ‘the beliefs, values and behaviors a person or a group of people have with regards to their own teaching or learning in specific contexts’. These beliefs, values and norms on excellence can differ within each teaching and learning culture (Behari-Leak & McKenna, Citation2017; Dixon & Pilkington, Citation2017; Lubicz-Nawrocka & Bunting, Citation2019; Roxå et al., Citation2011). This implies that conceptions of student excellence can differ between and even within institutions.

Therefore, these conceptions must be analyzed and understood within a specific teaching and learning culture, rather than in the abstract. FACE provides a reflective tool that enables teachers, students, and managers to become aware of beliefs, values and norms that are part of the teaching and learning culture of their own institution. Using this tool in the context of the design of an educational program may clarify incongruity between one's own views and those of the team or the institution.

In addition, the role of individual and ‘learning-culture-dependent’ beliefs, values and norms, in conjunction with the possible variations therein on the four questions, implies that different stakeholders (i.e., managers, teachers, and students) within an educational institution can attribute a different meaning to student excellence. Therefore, it is important that conceptions held by the different stakeholders are made explicit, and discussed in mutual coherence (Dixon & Pilkington, Citation2017; Skelton, Citation2009). We suggest that FACE can be used as a reflective tool that helps in finding common ground when designing and implementing educational programs aimed at evoking excellence.

Furthermore, FACE can help to avoid specific political or managerial interpretations. Neo-liberal managerial narratives of excellence in higher education are often found in contemporary educational policy and mission statements (O’Leary & Cui, Citation2018; Rostan & Vaira, Citation2011; Saunders & Ramiréz, Citation2017). This limited, political connotation has resulted in resistance to the term ‘excellence’ among both teachers and students (Anderson, Citation2008; Herschberg et al., Citation2018). FACE, on the other hand, invites teachers to reflect on their deep-rooted beliefs and values with regard to students and their learning process.

Thus, the resulting conceptual framework does not provide one specific perspective on ‘student excellence’. Instead, FACE is intended to serve as a reflective tool to make specific conceptions of a person or group explicit. We suggest that the framework's guiding questions, along with the possible answers presented, can help reveal taken-for-granted beliefs, which often remain unconscious until challenged (Maslowski, Citation2006). Also, answers to these questions point to values on what people believe to be good or desirable and worth striving for. Moreover, they elicit norms on how things should be done or are always done. Finally, they provide insight into practices related to evoking excellence (Maslowski, Citation2006).

When using FACE as a reflection tool, it is important to keep two things in mind: First, the answers to the guiding questions are strongly related but not necessarily congruent, for example, they might not be positioned on the same side of the inclusive–exclusive axis. Second, the combination of answers to these four questions by a person or group constitute conceptions of excellence.

The conceptual content of FACE

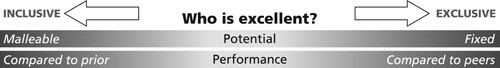

Who is an excellent student?

The question ‘who is excellent?’ can also be framed as ‘who can be excellent?’ This difference shows that conceptions of student excellence can be derived from two approaches: from focusing on potential or from focusing on previous performance (Laine et al., Citation2016). Potential and performance are closely linked, because potential refers to abilities that a person must have in order to perform. Answers in both categories – potential or performance – can be scored on the inclusive–exclusive axis of FACE.

Inclusive and exclusive views on who is excellent – potential

Literature on giftedness and high-ability students provides several types of characteristics of a student's potential that can lead to excellence, such as innovativeness (Banis-den Hertog, Citation2016), creativity, high intrinsic motivation, above-average cognitive ability and high task commitment (e.g., Gagné, Citation2004; Pullen et al., Citation2018; Renzulli, Citation1986; Sternberg, Citation2003).

When someone argues that an excellent student is identified by his/her potential, this can both be viewed from the perspective of entity theory, hence fixed mindset, or incremental theory, hence growth mindset (Dweck, Citation2012). A mindset consists of implicit beliefs people have about abilities and intelligence. People with a fixed mindset believe that these abilities and intelligence are fixed, whereas people with a growth mindset believe that these abilities are malleable and can be changed (Dweck, Citation2012). Regarding the axis of FACE, therefore, using a growth mindset perspective results in more inclusive answers, whereas a fixed mindset coincides with more exclusive answers to this question (Laine et al., Citation2016).

Inclusive and exclusive views on who is excellent – performance

Beliefs, values and norms on who is excellent can also be about student performance. This performance can be in different domains and does not have to be solely about cognitive achievements, but can also be about creativity, for instance. The type of achievement that is recognized in these beliefs depends on whether the belief is held that excellent students will excel in every domain as a result of context-free talents, or whether gifts and talents are domain specific and exceptionality thus depends on the context (Brusoni et al., Citation2014; Dai & Chen, Citation2013; Matthews & Dai, Citation2014). However, this does not yet determine whether someone has a more inclusive or exclusive view on performance.

Whether someone has a more exclusive or inclusive view on performance is determined by the point of reference (self or other) someone takes. When taking the performance of others as a point of reference, excellence means being the best. This view on performance complies with the performance orientation in Achievement Goal Theory (Ames, Citation1992), which argues that performance goals are focused on demonstrating competence, showing others that one is capable or the best (Maehr & Zusho, Citation2009). However, when taking past performance of the self as comparison, excellence implies development. This complies with the mastery orientation in Achievement Goal Theory: here, the focus is on the process of learning and on improving one's own performance (Maehr & Zusho, Citation2009). The latter perspective on excellence is far more inclusive than the first (Brusoni et al., Citation2014; Johnson, Citation2005). summarizes the perspectives on who is excellent.

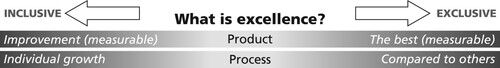

What is excellence of students?

The second question asked when analyzing conceptions of excellence is: what does excellence of students entail? Here, beliefs, values and norms regarding excellence of students focus on learning outcomes. These learning outcomes can be divided in product or process outcomes, since views on what student excellence is differ in whether excellence is perceived as measurable output (a product) versus something that is aspired for (a direction or process) (Brusoni et al., Citation2014, p. 21; Stewart, Citation2010). A focus on product or process is not inherently inclusive or exclusive, because, like in the who-question, this depends on the point of reference (self or other).

Inclusive and exclusive views on what is excellence – product

Excellence perceived as measurable output is a product that either meets or exceeds high standards. The mark ‘excellent’ can thus be reserved for best-of-class, best-of-year or best-of-university (Brusoni et al., Citation2014). This implies a comparison with others, therefore making this notion exclusive. On the other hand, excellence as product can be viewed in terms of development. A product can be considered excellent when it has improved considerably. When this is the case, excellence as product becomes inclusive, as improvement should be possible for every product (Maehr & Zusho, Citation2009).

Inclusive and exclusive views on what is excellence – process

Instead of seeing excellence as product, excellence can be perceived as embodied in the process of learning, which can be recognized in the way students strive for continuous improvement (Mintrom, Citation2014; Stewart, Citation2010). At first sight, a focus on excellence as process seems to fit with a growth mindset and with more inclusive views on excellence. However, the point of reference (self or other) taken to assess this learning process, also determines whether this actually is the case: comparing learning processes of students with each other, and determining which one is best, gives a more exclusive perspective, than only assessing individual growth in someone's learning process. See for the perspectives on what is student excellence.

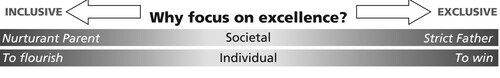

Why is evoking excellence of students necessary?

To truly understand individual conceptions of excellence, it is important to question why someone believes it is important to focus on student excellence (Cross & Cross, Citation2005; Dai & Chen, Citation2013). Conceptions of excellence are related to beliefs about the purpose of education in general, and the purpose of evoking student excellence in higher education in particular. According to Cross and Cross (Citation2005, p. 21), education reflects deep-seated values within society. Also, conceptions of student excellence are related to one's worldviews and conceptions about the nature of knowledge (Dai & Chen, Citation2013; Harder et al., Citation2014; Johnson, Citation2005). To show which answers can be given to the why-question, we therefore approach this question from two perspectives: from a societal perspective which focuses on the relevance of evoking student excellence for society, and from an individual perspective which is concerned with the relevance of student excellence for an individual.

We build on the work of Cross and Cross (Citation2005) for an analysis on how worldviews inform ideas on excellence. They apply Lakoff's (Citation2002) analysis of conservative and liberal reasoning to beliefs on gifted education, using the metaphors of respectively the conservative ‘Strict Father’ and the liberal ‘Nurturant Parent’. These opposing worldviews result in different conceptions of why excellence should be evoked, both on a societal as well as on an individual level. The Strict Father emphasizes that competition is natural and that only the strong ones will succeed, which concurs with exclusive views. The Nurturant Parent is geared towards personal development, stimulating all individuals to take their place in society and aligns with inclusive views (Cross & Cross, Citation2005).

Inclusive and exclusive views on why excellence from a societal perspective

According to the Strict Father metaphor, a focus on student excellence is beneficial for society as it emphasizes the necessity of having talented academics and professionals competing in the international global market, thereby strengthening the knowledge economy (Altbach et al., Citation2009; Lolich & Lynch, Citation2016; Mintrom, Citation2014). Therefore, this Strict Father reasoning can be placed on the ‘exclusive’ side of the continuum, as it ties in well with neo-liberal narratives on excellence in education that use the highly competitive globalized economy as their departure point. Astin and Antonio (Citation2012, p. 6) call this the ‘resources and reputational conceptions of excellence’: the more resources, the more excellent the institution. This was also argued in the US National Commission for Excellence in Education (NCEE) Report A Nation at risk in 1983. They argued that learning was an economic investment and necessary to develop a true knowledge-based economy (Flink & Peter, Citation2018). Furthermore, a focus on student excellence is important for a university's ranking and reputation and therefore for its ability to attract talented students and researchers (Brusoni et al., Citation2014; Long, Citation2002; Rostan & Vaira, Citation2011; Wilson, Citation2015).

According to Nurturant Parent narratives, a focus on student excellence is beneficial for society when it means stimulating talent development and enhancing well-being of all (Astin & Antonio, Citation2012; Joosten, Citation2014; O’Leary & Cui, Citation2018). This reasoning can be placed on the ‘inclusive’ side of FACE. Challenging students to make the most of their education is the way to ensure that every student uses his/her talents well and lives a full life (Dai & Chen, Citation2013; Mintrom, Citation2014). The talents of every individual student should be developed, including gifted students who may underexploit their talents in traditional educational settings (Dai & Chen, Citation2013; Wolfensberger, Citation2012). A focus on personal development and self-care are viewed not only as important for individuals, but also as necessary pre-conditions for the care of others. Therefore, values such as cooperation, maintaining social relationships and fair distributions are central in this narrative (Cross & Cross, Citation2005).

Inclusive and exclusive views on why excellence from an individual perspective

Societal beliefs and values are reflected in individual values and beliefs (Cross & Cross, Citation2005): what is someone's personal aim when striving for excellence? Here the focus is on the inherent values for individual students, instead of external values for society. Answers to this question can be placed on the inclusive–exclusive continuum as well. When applying the Strict Father metaphor to personal aims for striving for excellence, the focus is on competition, on becoming the best and on winning, which aligns with exclusive views on excellence. Also, students’ excellence needs to be evoked as it will help them get access to prestigious advanced educational programs or improve their future employability (Wolfensberger et al., Citation2012).

Within the Nurturant Parent narratives, on the other hand, the focus is on personal development, thriving and helping others to thrive. So, inclusive individual's views on why it is important to strive for excellence focus on personal growth, cooperation and flourishing (Cross & Cross, Citation2005) (see ).

How to evoke excellence of students?

The fourth question of FACE is concerned with the practice of teaching and learning: what should be done to evoke excellence of students? Several authors have described patterns of excellence in teaching and learning (Gibbs, Citation2008; Hattie, Citation2008; Mintrom, Citation2014) or have outlined specific teaching strategies that should lead to excellent performance (Rogers, Citation2007). Others have discussed ways to challenge high ability students (Scager et al., Citation2013, Citation2014) or means to evoke excellence in honors students (Wolfensberger, Citation2012).

However, in these studies, often the connection between norms and values concerning student excellence and the practice of teaching is not made explicit. Yet, teachers’ beliefs on excellence and the way they perceive students and their learning do impact their teaching (Pelletier et al., Citation2002), as do their beliefs regarding pedagogy (Lee et al., Citation2017; Norton et al., Citation2005). Therefore, it is important to realize that answers to the how-question are closely related to the answers to the other three questions of FACE, since the answers to these three questions influence beliefs, values and norms concerning the practices of teaching and learning (Dai & Chen, Citation2013).

Furthermore, there are also specific beliefs, values and norms on evoking student excellence that guide teachers in their answers to the how-question. To analyze these specific beliefs, we make a distinction in FACE between students and their learning on the one hand, and teachers and their role, on the other. The category ‘students and their learning’ focuses on what a student should do to become excellent. Within the category ‘teachers and their role’, the focus is on didactics and teaching. Again, answers within both categories can be inclusive as well as exclusive.

Inclusive and exclusive views on how to evoke excellence – students and their learning

When looking at students and their learning, we differentiate between a focus on discipline, competition, and performance on standardized tests on the one hand (Cross & Cross, Citation2005). In this view, students need to work hard, try to be the best, and do what the test requires or what the teacher considers important. This sits with more exclusive views on excellence. On the other hand, inclusive views regarding how excellence is evoked focus on cooperation, flexibility, and working together. Here, test scores and grades are less important, and the focus is on learning together (Cross & Cross, Citation2005).

Inclusive and exclusive views on how to evoke excellence – teachers and their role

When the focus is on teachers and their role, we can distinguish between a teacher-content orientation and learner-centered orientation. Within a teacher-content orientation the focus is on content and knowledge dissemination. The teacher is perceived as expert or knowledge provider (Gan & Geertsema, Citation2018; Lee et al., Citation2017). This orientation is more compatible with exclusive views on excellence, since it expresses a hierarchy: teacher as expert, as authority (Cross & Cross, Citation2005). Within a learner-centered pedagogy (Lee et al., Citation2017), the focus is on learning and the learning process (Norton et al., Citation2005). From this perspective, personal development and students’ own construction of knowledge are important (Lee et al., Citation2017). Here, the teacher acts like a coach, guiding the students (Cross & Cross, Citation2005). The learner-centered pedagogy is therefore more in line with inclusive views on excellence (see for an overview).

Figure 4. Inclusive and exclusive views concerning ‘How to evoke excellence?’, determined by an emphasis on student learning or teacher role.

To conclude, conceptions of student excellence are multi-faceted. The distinction between inclusive and exclusive views on student excellence is determined by underlying beliefs, values and norms. These beliefs, values and norms become explicit when answering the four guiding questions within their respective categories. Bringing all these elements together makes FACE a useful conceptual tool to provide a nuanced understanding of conceptions of student excellence teachers and students can have. shows the complete framework.

Discussion

In this article, we present a novel framework that can clarify and unravel existing conceptions of student excellence, which is relevant for teachers and students in educational programs that are aimed at evoking excellence. Conceptions of student excellence encompass beliefs on education and learning, as well as values on the why of education, and norms on how teachers and students should behave. These beliefs, values and norms together are included in conceptions of excellence.

In FACE these beliefs, values and norms become explicit in the answers positioned on the inclusive–exclusive continuum. On the exclusive end, excellence is referred to as a mark of distinction: in comparison to others, not everyone can be excellent. On the inclusive end, excellence is seen in reference to prior individual achievement, making it possible for everyone to strive for excellence. Furthermore, each question in FACE has two answer categories. Combining the four questions and their respective categories with the inclusive–-exclusive axis allows for a more fine-grained analysis of existing beliefs, values and norms regarding excellence of students which together mold conceptions.

FACE contributes in various ways to the debate on excellence within higher education. It can be used as a tool that creates more conceptual clarity and gives meaning to conceptions of excellence of students. FACE helps to determine what is meant by student excellence and provides substance to it. It also provides researchers with the necessary vocabulary to articulate the type of excellence they study (Dai & Chen, Citation2013, p. 164).

FACE shows that conceptions of student excellence are multi-faceted and consist of contradictory elements: they include various beliefs, values and norms about what excellence is or should be, and practices related to teaching and learning (Roxå et al., Citation2011). It clarifies the topics teachers talk about: do they come up with ideas related to who, what, why, or are they mainly focusing on how? In their discussions, do they focus on student characteristics, on the learning process of students, or maybe on high quality products students deliver? Or do they simultaneously adhere to seemingly contradictory ideas on the inclusive–exclusive axis, such as a focus on the individual learning process combined with outcomes such as an excellent written thesis?

Also, as already indicated, ‘student excellence’ is an ambiguous and inherently contested concept. The concept is rejected as meaningless, and some even argue that ‘excellence’ in education should not be used at all (Clegg, Citation2007; Cui et al., Citation2019). Instead, we argue that the concept of ‘student excellence’ expresses important values in teaching and learning that require ongoing discussion and explication.

FACE as a reflective tool

FACE functions as a reflective tool in three ways. First, FACE distinguishes four aspects, allowing for a systematic approach to examine assumptions regarding student excellence. Second, FACE provides conceptual content for these aspects (possible answers based on literature), allowing teachers and students to articulate their assumptions about student excellence that often remain hidden, but implicitly direct educational practices (Boon, Citation2017; Procee, Citation2006). Third, the inclusive–exclusive axis of FACE makes it possible to articulate different, perhaps incompatible, views on student excellence. FACE, therefore, can be used to identify the diversity of conceptions of student excellence within and between subgroups at all levels of the educational organization.

FACE thus assists teachers and students in articulating conceptions of excellence, and by doing so, FACE serves as a reflective tool for teachers and students by stimulating dialogue. This dialogue is a shared and collaborative act of inquiry (Stewart & McClure, Citation2013, p. 95). In this dialogue, both reflection and action are essential components (Freire, Citation2005, pp. 87–88). Thus, a dialogue on student excellence includes both reflection on the meaning of conceptions of student excellence, as well as reflection on the impact of these conceptions on educational practice.

Through this dialogue, teachers can reflect on their assumptions (Brookfield, Citation1992), and their theories of practices (Kinsella, Citation2001). They can bring their educational practice more in line with their underlying values and beliefs, thus improving their reflective practice (Schön, Citation1983, p. 31). Through this dialogue, students gain a better understanding of the aims of their education and are able to evaluate their learning process in line with their own assumptions on student excellence.

As a next step, FACE can also be used to find common ground (Roxå et al., Citation2011); through dialogue a team or group can develop a shared meaning of student excellence in the context of their teaching and learning practices (Dixon & Pilkington, Citation2017; Skelton, Citation2009). In this way, the use of FACE as a reflective tool contributes to more clarity on the meaning of student excellence and the impact this has on educational practice.

Avenues for further research

This framework also provides avenues for further research. First, FACE offers a tool for a more systematic analysis of teachers’ conceptions of student excellence across different institutions. Studies could also incorporate observations of teacher practices to study what kind of excellence of students teachers promote through their teachings and compare that with their conceptions. Also, in line with what others have argued (Dixon & Pilkington, Citation2017; Wood & Su, Citation2017), FACE can be used to analyze differences between stakeholders (teachers, students, and managers) within an educational institution. This could lead to a better understanding of the meaning of ‘student excellence’ between various groups that together form teaching and learning cultures, in order to avoid miscommunication or mismatch (Sagy et al., Citation2019).

In addition, FACE could be used to systematically compare conceptions of student excellence in programs specifically aimed at promoting excellence, such as honors programs or selective research master programs, with other educational programs. This is relevant, for example, when an institution considers transferring educational approaches from these programs to other educational programs.

To conclude, the Framework for Analyzing Conceptions of Excellence presented here, can be used to clarify conceptions of ‘student excellence’ in a specific teaching and learning culture, by shedding light on beliefs, values and norms people have. It also supports dialogue between stakeholders within an institute. In that way, teachers, students, and managers can come to a better understanding of what student excellence means in their context of teaching, learning, or educational design process. Based on that understanding, they can work together to enhance student excellence in a way that benefits all.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allan, C. (2011). Exploring the experience of ten Australian Honours students. Higher Education Research & Development, 30(4), 421–433. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2010.524194

- Altbach, P. G., Reisberg, L., & Rumbley, L. E. (2009). Trends in global higher education: Tracking an academic revolution. A report prepared for the UNESCO 2009 world conference on higher education. UNESCO.

- Ames, C. (1992). Classrooms: Goals, structures, and student motivation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 84(3), 261–271. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.84.3.261

- Anderson, G. (2008). Mapping academic resistance in the managerial university. Organization, 15(2), 251–270. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508407086583

- Astin, A. W., & Antonio, A. L. (2012). Assessment for excellence: The philosophy and practice of assessment and evaluation in higher education (2nd ed.). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

- Banis-den Hertog, J. (2016). X-factor for innovation: Identifying future excellent professionals [Doctoral dissertation]. Twente University. https://research.utwente.nl/en/publications/x-factor-for-innovation-identifying-future-excellent-professional

- Behari-Leak, K., & McKenna, S. (2017). Generic gold standard or contextualised public good? Teaching excellence awards in post-colonial South Africa. Teaching in Higher Education, 22(4), 408–422. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2017.1301910

- Boon, M. (2017). Philosophy of science in practice: A proposal for epistemological constructivism. In H. Leitgeb, I. Niiniluoto, P. Seppälä, & E. Sober (Eds.), Logic, Methodology and Philosophy of Science – Proceedings of the 15th International Congress (CLMPS 2015) (pp. 289–310). College Publications. http://www.collegepublications.co.uk/lmps/?00016

- Brookfield, S. (1992). Uncovering assumptions: The key to reflective practice. Adult Learning, 3(4), 13–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/104515959200300405

- Brusoni, M., Damian, R., Sauri, J. G., Jackson, S., Kömürcügil, H., Malmedy, M., Matveeva, O., Motova, G., Pisarz, S., Patricia, P., Rostlund, A., Soboleva, E., Tavares, O., & Zobel, L. (Eds.). (2014). The concept of excellence in higher education. ENQA.

- Castejón, J. L., Gilar, R., Miñano, P., & González, M. (2016). Latent class cluster analysis in exploring different profiles of gifted and talented students. Learning and Individual Differences, 50, 166–174. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2016.08.003

- Clegg, S. (2007). The demotic turn – excellence by fiat. In A. Skelton (Ed.), International perspectives on teaching excellence in higher education. Improving knowledge and practice (pp. 91–102). Routledge.

- Cross, J. R., & Cross, T. L. (2005). Social dominance, moral politics, and gifted education. Roeper Review, 28(1), 21–29. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02783190509554333

- Cui, V., French, A., & O’Leary, M. (2019). A missed opportunity? How the UK’s teaching excellence framework fails to capture the voice of university staff. Studies in Higher Education, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1704721

- Dai, D. Y., & Chen, F. (2013). Three paradigms of gifted education in search of conceptual clarity in research and practice. Gifted Child Quarterly, 57(3), 151–168. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0016986213490020

- Dixon, F. J., & Pilkington, R. (2017). Poor relations? Tensions and torment; a view of excellence in teaching and learning from the Cinderella sector. Teaching in Higher Education, 22(4), 437–450. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2017.1301912

- Dweck, C. S. (2012). Mindsets and Malleable minds: Implications for giftedness and talent. In R. F. Subotnik, A. Robinson, & C. M. Callahan (Eds.), Malleable minds: Translating insights from psychology and neuroscience to gifted education (pp. 7–18). The National Research Center on the Gifted and Talented, University of Connecticut.

- Flink, T., & Peter, F. (2018). Excellence and frontier research as travelling concepts in science policymaking. Minerva, 56(4), 431–452. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11024-018-9351-7

- Freire, P. (2005). Pedagogy of the oppressed (30th anniversary ed.). Continuum.

- Gagné, F. (2004). Transforming gifts into talents: The DMGT as a developmental theory. High Ability Studies, 15(2), 119–147. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1359813042000314682

- Gan, M. J. S., & Geertsema, J. (2018). Sharing practices, but what is the story? Exploring award-winning teachers’ conceptions of teaching. Higher Education Research & Development, 37(2), 254–269. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2017.1373331

- Gibbs, G. (2008). Conceptions of teaching excellence underlying teaching award schemes. The Higher Education Academy.

- Harder, B., Vialle, W., & Ziegler, A. (2014). Conceptions of giftedness and expertise put to the empirical test. High Ability Studies, 25(2), 83–120. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13598139.2014.968462

- Hattie, J. (2008). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. Routledge.

- Heller, K. A. (2012). Different research paradigms concerning giftedness and gifted education: Shall ever they meet? High Ability Studies, 23(1), 73–75. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13598139.2012.679097

- Herschberg, C., Benschop, Y., & Van den Brink, M. (2018). Selecting early-career researchers: The influence of discourses of internationalisation and excellence on formal and applied selection criteria in academia. Higher Education, 1–19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-018-0237-2

- Johnson, A. (2005). Caught by our dangling paradigms: How our metaphysical assumptions influence gifted education. The Journal of Secondary Gifted Education, 16(2-3), 67–73. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4219/jsge-2005-469

- Joosten, H. (2014). Excelleren voor iedereen: Nietsche als inspiratiebron voor het hoger onderwijs [Excellence for everyone: Nietsche as inspiration for higher education]. Tijdschrift voor Hoger Onderwijs, 32(2), 156–167. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5553/TvHO/016810952014032002002

- Kinsella, E. A. (2001). Reflections on reflective practice. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 68(3), 195–198. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/000841740106800308

- Kool, A., Mainhard, T., Jaarsma, D., Van Breukelen, P., & Brekelmans, M. (2017). Effects of honours programme participation in higher education: A propensity score matching approach. Higher Education Research & Development, 36(6), 1222–1236. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2017.1304362

- Lakoff, G. (2002). Moral politics: How liberals and conservatives think. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Laine, S., Kuusisto, E., & Tirri, K. (2016). Finnish teachers’ conceptions of giftedness. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 39(2), 151–167. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0162353216640936

- Lee, W. C., Chen, V., & Wang, L. (2017). A review on research on teacher efficacy beliefs in the learner-centred pedagogy context: Themes, trends and issues. Asia Pacific Education Review, 18(4), 559–572. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-017-9501-x

- Lolich, L., & Lynch, K. (2016). The affective imaginary: Students as affective consumers of risk. Higher Education Research & Development, 35(1), 17–30. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2015.1121208

- Long, B. T. (2002). Attracting the best: The use of honors programs to compete for students. Report for the Harvard Graduate School of Education. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. Ed465355). Spencer Foundation.

- Long, E. C. J., & Mullins, D. (2012). Honors around the globe. Journal of the National Collegiate Honors Council, 13(2), 1–6.

- Lubicz-Nawrocka, T., & Bunting, K. (2019). Student perceptions of teaching excellence: An analysis of student-led teaching award nomination data. Teaching in Higher Education, 24(1), 63–80. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2018.1461620

- Maehr, M. L., & Zusho, A. (2009). Achievement goal theory. The past, present, and future. In K. R. Wentzel, & D. B. Miele (Eds.), Handbook of motivation at school (pp. 77–104). Routledge.

- Maslowski, R. (2006). A review of inventories for diagnosing school culture. Journal of Educational Administration, 44(1), 6–35. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/09578230610642638

- Matthews, D. J., & Dai, D. Y. (2014). Gifted education: Changing conceptions, emphases and practice. International Studies in Sociology of Education, 24(4), 335–353. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09620214.2014.979578

- Merriam Webster. (2018). Online dictionary. Retrieved October 16, 2018, from www.merriam-webster.com

- Millward, P., Wardman, J., & Rubi-Davies, C. (2016). Becoming and being a talented undergraduate student. Higher Education Research & Development, 35(6), 1242–1255. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2016.1144569

- Mintrom, M. (2014). Creating cultures of excellence: Strategies and outcomes. Cogent Education, 1(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2014.934084

- Mudrak, J., Zabrdska, K., & Machovcova, K. (2019). Psychological constructions of learning potential and a systemic approach to the development of excellence. High Ability Studies, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13598139.2019.1607722

- Norton, L., Richardson, J. T. E., Hartley, J., Newstead, S., & Mayes, J. (2005). Teachers’ beliefs and intentions concerning teaching in higher education. Higher Education, 50(4), 537–571. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-004-6363-z

- O’Leary, M., & Cui, V. (2018). Reconceptualising teaching and learning in higher education: Challenging neoliberal narratives of teaching excellence through collaborative observation. Teaching in Higher Education, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2018.1543262

- Pelletier, L. G., Séguin-Lévesque, C., & Legault, L. (2002). Pressure from above and pressure from below as determinants of teachers’ motivation and teaching behaviors. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(1), 186–196. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.037//0022-0663.94.1.186

- Procee, H. (2006). Reflection in education: A Kantian epistemology. Educational Theory, 56(3), 237–253. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-5446.2006.00225.x

- Pullen, A. G., Griffioen, D. M. E., Schoonenboom, J., De Koning, B. B., & Beishuizen, J. J. (2018). Does excellence matter? The influence of potential for excellence on students’ motivation for specific collaborative tasks. Studies in Higher Education, 43(11), 2059–2071. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1304376

- Renzulli, J. S. (1986). The three-ring conception of giftedness. In R. J. Sternberg & J. E. Davidson (Eds.), Conceptions of giftedness (pp. 53–92). Cambridge University Press.

- Rogers, K. B. (2007). Lessons learned about educating the gifted and talented: A synthesis of the research on educational practice. Gifted Child Quarterly, 51(4), 382–396. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0016986207306324

- Rostan, M., & Vaira, M. (2011). Questioning excellence in higher education: Policies, experiences and challenges in national and comparative perspective. Sense Publishers.

- Roxå, T., Mårtensson, K., & Alveteg, M. (2011). Understanding and influencing teaching and learning cultures at university: A network approach. Higher Education, 62(1), 99–111. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-010-9368-9

- Sagy, O., Hod, Y., & Kali, Y. (2019). Teaching and learning culturs in higher education: A mismatch in conceptions. Higher Education Research & Development, 38(4), 849–863. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1576594

- Sagy, O., Kali, Y., Tsaushu, M., & Tal, T. (2018). The culture of learning continuum: Promoting internal values in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 43(3), 416–436. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2016.1174205

- Saunders, D. B., & Ramiréz, G. B. (2017). Against ‘teaching excellence’: Ideology, commodification, and enabling the neoliberalization of postsecondary education. Teaching in Higher Education, 22(4), 396–407. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2017.1301913

- Scager, K., Akkerman, S. F., Pilot, A., & Wubbels, T. (2013). How to persuade honors students to go the extra mile: Creating a challenging learning environment. High Ability Studies, 24(2), 115–134. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13598139.2013.841092

- Scager, K., Akkerman, S. F., Pilot, A., & Wubbels, T. (2014). Challenging high-ability students. Studies in Higher Education, 39(4), 659–679. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2012.743117

- Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Basic Books.

- Skelton, A. M. (2009). A ‘teaching excellence’ for the times we live in? Teaching in Higher Education, 14(1), 107–112. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510802602723

- Sternberg, R. J. (2003). WICS as a model of giftedness. High Ability Studies, 14(2), 109–137. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1359813032000163807

- Stewart, A. E. (2010). Explorations in the meaning of excellence and its importance for counselors: The culture of excellence in the United States. Journal of Counseling and Development, 88(2), 189–195. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2010.tb00008.x

- Stewart, T. T., & McClure, G. (2013). Freire, Bakhtin, and collaborative pedagogy: A dialogue with students and mentors. International Journal for Dialogical Science, 7(1), 91–108.

- Trigwell, K., Prosser, M., & Waterhouse, F. (1999). Relations between teachers’ approaches to teaching and students’ approaches to learning. Higher Education, 37(1), 57–70. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1003548313194

- Wilson, M. R. (2015). Value added. Journal of the National Collegiate Honors Council, 16(2), 171–175.

- Wolfensberger, M. V. C. (2012). Teaching for excellence. Honors pedagogies revealed [Doctoral dissertation]. Waxmann. http://dspace.library.uu.nl/handle/1874/261033

- Wolfensberger, M. V. C. (2015). Talent development in European higher education. Honors programs in the Benelux, Nordic and German-speaking countries. Springer.

- Wolfensberger, M., Van Eijl, P., & Pilot, A. (2012). Laboratories for educational innovation: Honors programs in the Netherlands. Journal of the National Collegiate Honors Council, 13(2), 149–170.

- Wood, M., & Su, F. (2017). What makes an excellent lecturer? Academic's perspectives on the discourse of ‘teaching excellence’ in higher education. Teaching in Higher Education, 22(4), 451–466. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2017.1301911