ABSTRACT

Higher Degree by Research (HDR) students are an important part of Australian university research culture. They contribute significantly to the generation of new knowledge, research outputs, industry engagement and the continual development of higher education. This article is the first to systematically review existing research to synthesise the key areas of HDR student experience within the Australian context. A systematic review of the literature was conducted following PRISMA protocols, and 7 themes were identified across the 68 papers included in the review. Themes reflected supervisory relationships, challenges for international students, engagement with research communities, balancing life contexts, administrative challenges, thesis by publication, and industry-based research. The overall findings suggest a need for universities to be more proactive in supporting the unique needs of HDR students in a changing educational context.

Introduction

Higher Degree by Research (HDR) students play a key role in Australian universities, with important contributions to both the economy and society (McGagh et al., Citation2016). They generate new knowledge, understanding, and technologies allowing for global challenges to be addressed across diverse areas including climate change, food security, technological innovation, and pandemics such as COVID-19. Ensuring that HDR programmes address such priorities and result in positive student experiences is complex. This is due to a dynamic and changing academic landscape and the many difficulties HDR students can experience as part of their research journey.

According to the Department of Education, Skills, and Employment (DESE), Australia has a diverse cohort of HDR learners. This is evident across the areas of programme, mode of study, and study area; cultural background; geographical location; socio-economic background; and disability (DESE, Citation2019). In 2019, 70% of HDR students were enrolled full-time and 30% part-time. According to percentages of commencing HDRs, students were studying across a diverse range of fields, including natural and physical sciences (22.8%), society and culture (18.4%), health (16.7%), engineering and related technologies (15.3%), management and commerce (8.3%), education (5.5%), information technology (4.8%), creative arts (4%), agriculture and environment (2.7%), and architecture and building (1.5%). Recent changes placing additional weightings on government funding for those programmes actively engaged with industry via internships further broadens the types of students within these research areas.

Based on the 2019 DESE statistics, culture and geographical location add to the diversity of the HDR academic landscape. For example, international students accounted for 36% of the HDR student population. Of the 64% domestic students, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students accounted for 1% of enrolments and students from a regional or rural area accounted for 8.9%. The diversity in geographical location is linked to changes in modes of delivery and offering the possibility of researching online and remotely. However, this potentially limits some of the associated benefits of face-to-face contact with peers and supervisors, School and Faculty and being part of a research community.

Socioeconomic background and disability are additional elements that add to the complexity and richness of student experience within HDR programmes. In 2019, 8.9% of all domestic HDR students identified as being from a low socio-economic background (DESE, Citation2019) and between 1996 and 2020 postgraduate research students with a disability has increased from 483 to 2700 (DESE, Citation2020). Varied cohorts across programme, mode of study and study area, cultural background, geographical location, socio-economic background, and disability represent a diverse and dynamic academic landscape containing students with differing needs and experiences relative to their circumstances. Providing for these needs and ensuring HDR students experience positive research journeys is a complex endeavour.

Higher Degree by Research study can also be a turbulent journey, in which students experience complex challenges. For example, as the time required across the research journey becomes more demanding, balancing work, study, and family commitments can become more difficult (Beasy et al., Citation2021). This can affect the time candidates have to effectively maintain personal relationships and can contribute to feelings of isolation, a common issue for doctoral candidates (Lee et al., Citation2013; McAlpine & Amundsen, Citation2011). Isolation can be especially acute for those students studying off campus and online (Owens et al., Citation2020).

Given current educational circumstances and the diverse range of research students, both domestic, international, on-campus, distance, and first-generation students and the challenges they undergo, it is important to examine HDR student experience. This can assist in the facilitation of research student success and wellbeing, approaches to research training, as well as address HDR completion and attrition rates. This is useful given that a recent review of Australia’s Research Training System concluded that while Australia’s research system is ‘world class in many respects’, there is scope to improve HDR training practices (Department of Education and Training, Citation2018). Although completion rates in Australia vary according to idiosyncratic, demographic, and cohort characteristics, as well as differing institutional policies and practices (DESE, Citation2020; Torka, Citation2020), information on student experience can be used to improve completion rates and consequent government funding. There is a large body of research that examines HDR students within the Australian context, but to date none have systematically reviewed and synthesised understandings of student experience into key themes. This synthesis will assist university research leaders, policy makers, and research supervisors to understand the HDR student experience and inform decisions that impact the student journey and university research outcomes. This article seeks to address this gap and systematically bring together the existing research to address the research question: What are the experiences of HDR students studying higher degrees by research in Australia?

Method

A systematic literature review was undertaken that brought together research around the HDR student experience within the Australian context. A systematic literature review should follow an established protocol that is both rigorous and transparent in terms of review methods, research questions, search processes, manuscript screening, and quality checks where applicable (Lasen et al., Citation2018). For the present research, the methodology was adapted from the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Manual for Evidence Synthesis (Aromataris & Munn, Citation2020) including using relevant JBI critical appraisal tools. The step-by-step protocol: (a) established eligibility criteria to include or exclude literature; (b) articulated search terms to discover relevant literature; (c) selected and searched relevant databases using precise Boolean strings and export abstracts; (d) screened data (abstracts then full papers) and then extracted data; and (e) synthesised the data.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria included: (a) Research participants were HDR students studying at an Australian university; (b) Only HDR student perspectives were considered (as opposed to supervisors or non-research students); (c) English language content only; (d) Any methodology excluding literature reviews or meta-analyses; and (e) Peer reviewed journal articles only (i.e., excluding book chapters and other literature).

Development of search terms and selection of library databases

An initial search of Google Scholar using the terms PhD, HDR, Australia, and experience returned multiple articles. Following this broad search, terms were further refined using PICo to better reflect the research question posed, as shown in below.

Table 1. Definition of research terms using PICo.

Further advice around search terms and synonyms, databases, and effective Boolean search strings was sought from a university research librarian. Following this consultation, the following Boolean search string was developed.

(experience? OR success? OR performance? OR complet*) AND (student? OR graduate? OR candidate?) AND (HDR OR ‘higher degree by research’ OR ‘higher degree research’ OR ‘higher degree’ OR PhD OR doctora*) AND Australia?

Search strategy and selection of literature

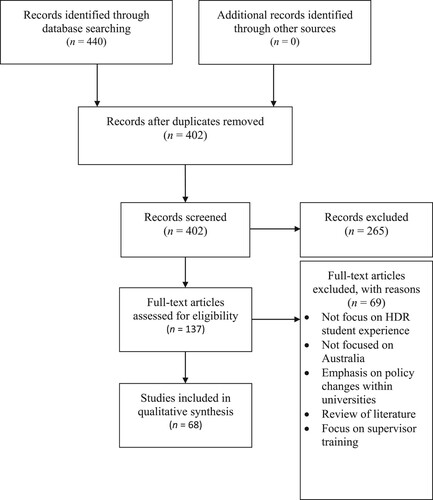

Searches took place in two phases, in January 2020 and a follow-up search in November 2021, across all selected databases without date restrictions. Searches were undertaken by three researchers and cross-checked by members of the research team. Searches were limited to title, keywords, and abstracts. All relevant abstracts were downloaded and imported into EndNote to organise the literature for screening. Once duplicates were removed, two researchers independently screened abstracts (n = 402) for inclusion and exclusion against the eligibility criteria and later met to resolve any disagreements. Where disagreements could not be resolved, a third member of the research team made an assessment and recommendation. Next, full papers were downloaded (n = 137) and again were independently screened for inclusion and subsequent data extraction and synthesis (n = 68). Any disagreements in screening were resolved through discussion based on returning to the eligibility criteria with a third researcher consulted if necessary. A flow diagram derived from search logs outlining each data screening step is provided in and includes reasons why articles at the full-text stage of screening were excluded.

Results

Summary data from the final papers selected for inclusion were extracted, focusing on the number of HDR student participants in each study, the methodological approach adopted, and key findings. Please see table in supplementary materials. Data were then organised thematically to illustrate the themes shared across the body of research literature (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019).

Methodological summary and study characteristics

In total, 68 papers were included in the final synthesis. Most of the papers utilised more than one research method. Of the included papers, the main methods adopted were interviews (30), surveys (29), and focus groups (14). The other methodological approaches comprised diary analysis (6), autoethnography (4), case studies (6), and other approaches, e.g., action-based research, randomised control trials, document analysis, etc. (14). The total number of participants across all studies was 8502, with participant numbers in individual studies ranging from 1 to 1531. All papers were retained for thematic synthesis irrespective of quality assessment.

Thematic synthesis

Seven key themes were identified across the 68 papers, with some papers reflecting more than one theme. The main themes are summarised below and are recorded against each paper in the data extraction table (see supplementary Table 1).

Supervisory relationships

The majority of the papers (n = 35) reported on the importance of positive supervisory relationships in supporting successful progression through HDR studies. For example, Barry et al. (Citation2018) reported that most of the challenges experienced by participants during their HDR journey were related to supervisory relationships. The relationship with the principal supervisor was considered particularly crucial and one that needed to be based on mutual trust and respect (Berridge, Citation2008). Power differences in the relationships between students and supervisors were found to negatively impact student progression (Jones & Blass, Citation2019). Students were, however, reluctant to challenge these differences and find their own voice due to the acknowledgement that supervisors were frequently placed under institutional pressure to perform and the need for positive references from supervisors post-PhD (Jones & Blass, Citation2019).

Davis (Citation2019) explored students’ perceptions of an ideal HDR supervisor and found that students valued cognitive and affective personal qualities ahead of discipline and research expertise, highlighting the need for a mutual respectful and trusting relationship to support success. This was echoed by Halbert (Citation2015), who found that quality supervision from a student perspective was a balance between academic and emotional support (see also Yim & Waters, Citation2013). However, Satariyan et al. (Citation2015) highlighted the importance of disciplinary expertise in addition to these qualities. Ives and Rowley (Citation2005) further highlighted the importance of continuity of supervision, with changes in supervision leading to problems and delays. Owens et al. (Citation2020) also considered the impacts of supervisory changes with participants emphasising not only difficulties in finding a supervisor but also being subject to changes in team that are beyond their control.

Cotterall (Citation2011) identified structural elements associated with positive supervisor practices, which included providing guidance throughout candidature milestones, being a mentor, and a champion for their student (see also Fung et al., Citation2017; Robertson, Citation2017). For the participants in Roach et al. (Citation2019), attributes of supervisors that reflected open communication and constructive feedback were considered key. This was further extended on through a call for the development of interpersonal qualities in supervisor training programmes. Further, supervisory teams were most effective when they operated as a unified voice for candidates rather than one that was fractured and diverse. Such diversity was found to have negative impacts for students (Guerin & Green, Citation2015).

Differences in experiences of supervision were highlighted by Harman (Citation2003b), who found that in their large survey of students, female PhD students were more dissatisfied than their male counterparts in terms of both course experience and supervision. Important factors related to this included lack of access to supervisory support due to the high workloads of supervisors. This, however, should be considered in conjunction with the different supervisory role expectations of HDR students and their supervisors; Ross et al. (Citation2011) highlighted sometimes differing perspectives as to the role of supervisors. For example, students reported their perception of the role of a supervisor was to develop writing skills to a larger extent than was considered by supervisors.

Reflecting on the experiences of Indigenous HDR students specifically, Trudgett (Citation2011) found some evidence that Indigenous students with Indigenous-focused topics would benefit from having an Indigenous supervisor, or supervisors with appropriate cultural knowledge. Of the 55 students contributing to the study, 70.9% were supported by non-Indigenous supervisors and approximately 50% believed that supervisors should undertake mandatory cultural awareness training. Further, the paper called for community members to have more involvement with the process of research. Building on these findings, Trudgett (Citation2014) outlined a best practice framework for supporting the unique needs of Indigenous HDR students.

The importance of positive supervisory relationships was magnified for international students. Supervisors were identified as a conduit to embedding international students within the university research community, as well as providing sensitive feedback and guidance (e.g., Ai, Citation2017; Wang & Li, Citation2011). Indeed Yarlagadda et al. (Citation2018) reported that supervisors’ maintenance of student motivation was the single largest factor in HDR completion. Further, Dai and Hardy (Citation2021) highlighted the power differences between international students and supervisors and corresponding challenges. Similarly, Shen (Citation2008) noted the hierarchic expectations that students from China held, and the belief that they should not challenge the supervisor in any way (see also Winchester-Seeto et al., Citation2014).

Unique challenges of being an international student

Twenty-one papers focused on unique challenges associated with being an international student. In addition to language and writing challenges, a need for positive engagement in communities to overcome cultural barriers and the central role that supervisors play in supporting international students were identified. Harman (Citation2003a) found that overall international students reported higher satisfaction, but concerns were expressed around supervision, frequently compounded by language challenges, and the spaces provided on campus within which to complete research (see also Ma, Citation2021; Son & Park, Citation2014; Winchester-Seeto et al., Citation2014; Yeoh & Thao, Citation2012).

Fotovatian and Miller (Citation2014) found that participants called for a critique of the stereotype of what is an ‘international student’. Participants in this study posited that a lack of attention is paid to the heterogeneity of this group, with the administrative label of ‘international student’ being imposed on them, and it being difficult to move beyond this. This singling out as ‘different’ further served to distance them from other students (see also Nguyen & Pennycook, Citation2018).

Chapman and Pyvis (Citation2005) focused on the experiences of being an offshore HDR student and the impacts of this on student identity. Chapman and Pyvis reported that students faced difficulties in interacting with their supervisor and rather than risk being considered a ‘bother’ they would sometimes wait several weeks before asking what they considered trivial questions. The role of a timely and supporting supervision arrangement was therefore lost. Additionally, given the geographical distance due to being offshore, some participants reflected that they felt very little attachment to the university.

Nguyen and Pennycook (Citation2018) found that in addition to the more anticipated challenges with language, the identity development of Vietnamese students in the sample was of concern. HDR students in this study reported challenges in adjusting to the Australian higher education system, and felt they were considered by others as ‘outsiders’. This was compounded by supervisor expectations of independence which at times was at odds with the interdependence expectations of the student. Zeivots (Citation2021) also reported on frustrations by international students which included feelings of being outsiders, a lack of engagement with the community, and dissatisfaction with the rules governing working opportunities. These participants suggested that universities should facilitate more events to promote opportunities for connection for international students. Similarly, Nomnian (Citation2017) highlighted the need for careful consideration of the expectations of students and supervisors in terms of student agency.

Engagement with the research community and developing an academic identity

Twenty papers reported on the importance of being engaged with a research community within the university and the facilitation of the development of an academic identity, especially as the role transitions from student to academic colleague in the latter parts of HDR study. Barry et al. (Citation2018) highlighted a lack of social interaction with an academic community as a key concern for HDR students. Further, Devenish et al. (Citation2009) found that collaborative peer support was considered by HDR students to be crucial to individual success, but again this was at times lacking. Work by Klenowski et al. (Citation2011) found that one approach to this was through communities of practice that could support and facilitate the development of academic and researcher identities. The opportunities afforded by peer learning and the development of a community of belonging were also highlighted in the work of Maher et al. (Citation2008), Mantai (Citation2019), Parker (Citation2009), and Macoun and Miller (Citation2014). Cotterall (Citation2015) reported that none of the participants in their study reported feeling supported by their school/research department and were lacking in peer networks. The researcher called for more action from universities in supporting the development of an academic identity. The need for integration with the academic community and peer networks was found to be amplified for international students (Yu & Wright, Citation2016).

However, Naylor et al. (Citation2016) caution against generalised approaches to address such issues and urge a reflection on the need to consider the specific academic disciplines of students and the potentially differing needs in terms of support that may be required, e.g., for lab-based students. In short, a one-size-fits-all approach may not be the solution for engagement with academic community and fostering positive identity development for HDR students.

Balancing life contexts and health and wellbeing of HDR students

The management of tensions outside of study, including family relationships, financial strains, and the management of individual health and wellbeing was reflected in 16 articles. Beasy et al. (Citation2021) reported that the competing demands experienced by some HDR students led to ill-health and anxiety. These findings were supported by Stylianou et al. (Citation2017), whose participants expressed concerns with unstable employment and perceived employment challenges post-PhD that were further compounded by the challenge of neoliberal university contexts. This resulted in highly competitive environments characterised by a pressure to publish yet supports to foster these skills were not always being provided. Crossman (Citation2005) found that for employed HDR students, balancing demands of the workplace was a core influencing component on student progression and success.

Barry et al. (Citation2018) found that HDR students reported higher levels of perceived stress and higher scores on the 42-item Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS) when compared with the general population. This was however still within the ‘normal’ range. Hutchings et al. (Citation2018) identified a major theme of isolation among the participants in their research. Peer support was considered central, with supervisors reporting feeling unequipped to support students’ mental health. The prime directive from this research was that HDR students need to feel supported by their supervisors but also connected to their peers. Finally, Usher and McCormack (Citation2021) found that relationships between HDR study and wellbeing represent a complex interaction, which is impacted by age and international versus domestic student status.

Administrative challenges

Thirteen papers focused on challenges posed by university structures. These included positive supports for development of skills such as writing, and more challenging elements ranging from the provision of adequate working spaces to the impacts of broader thinking around HDR completions. HDR students participating in Bendix Petersen’s (Citation2012) study reported that universities were slow and bureaucratic, with the implication being that it is time-consuming for students to navigate through administrative systems. Hierarchy amongst academics was considered to add to this tension.

Beasy et al. (Citation2021) found in their online survey that the lack of institutional support for HDR students coupled with the ‘dehumanising process of candidature’ (p. 608) added to the stressors of being an HDR student. This was echoed in the findings of Dickie (Citation2011), where a positive environment in which the university provided appropriate structures to support training and skill development was considered important facilitators for student success. Taylor et al. (Citation2004) found that access to support sites was often challenging, contributing to a stressful environment for students. Participants in Kefford and Morgenbesser (Citation2013) highlighted the need for more opportunities and support to be provided to potential and existing students in supporting their research choices. It was evident however that there was some confusion as to the role of Faculty, and whether this was purely academic or social as well (Due et al., Citation2015).

Trudgett (Citation2009) examined university supports specifically for Indigenous students and found that support officers did not sufficiently understand the needs of Indigenous students, and Indigenous students were not familiar with the support services that are available. This may mean that students miss out on key opportunities for support and scholarship application.

Challenges of a thesis by publication

Seven papers considered the nuances associated with completing a PhD by publication. Issues reported included the additional stress associated with pursuing a thesis by publication and the perception by students that this approach was favoured in part to progress the career of the supervisory team. Clear guidelines and experienced supervisors who were active researchers in their field were reported to support success for a thesis by publication.

Cumming (Citation2009) reflected on several challenges faced by HDR students, with a key one being the perceived pressure to publish to enhance their own career prospects and achieving balance in terms of supervisor contributions to this (see also Mason et al., Citation2021). Despite challenges in negotiating authorship and the risks of not getting articles published, Jowsey et al. (Citation2020) report that overall, the benefits of having publications were acknowledged as an important element of the CVs for post-PhD plans (see also Merga et al., Citation2019; Citation2020).

However, Mason (Citation2018) reported that for success to be achieved in PhD by publication, clear institutional support guidelines need to be established. Mason highlights, for example, that the time required for publication processes can create stress for students and therefore policies that are flexible in the requirements for theses by publication that do not require all papers to be published can help to relieve student stress (see also Merga, Citation2015). Established processes also need to be supported by adequate training for students and mentoring by supervisors in publication achievement (Mason et al., Citation2021).

Challenges specific to industry-based research

Four papers specifically reflected on links with industry in the completion of PhDs. The papers indicated differing experiences for students who were based in industry, with those embedded in collaborative Cooperative Research Centre (CRC)-based projects generally having enhanced development of skills in areas such as IP, commercialisation, and leadership. However, there was a challenge in meeting the needs of both the university and industry partner.

Harman (Citation2002) focused on understanding the experiences of HDR students who were part of CRCs. Harman found that overall reported satisfaction of CRC students was comparable with those students based solely in universities. These CRC students did, however, report wider opportunities for skill development and were more likely to consider a career in industry rather than academia. Manathunga et al. (Citation2009) also reported on perceived benefits of CRC-based research students, particularly in work-readiness.

Morris et al. (Citation2012) found that industry-based students had more frequent contact with their supervisors and reported being more engaged and embedded within a research culture. Stewart and Chen (Citation2009) found that in addition to real-world applications becoming more apparent, industry-based research also brought financial benefits through causal work opportunities. However, with this came tensions in balancing time management and meeting the needs of both the university and industry partner. Role confusion was also highlighted, with some HDR students reporting engaging with menial tasks due to lack of role clarity or alternatively engaging with industry roles that led to the PhD research becoming secondary to the industry work. Overall, however, participants in Stewart and Chen’s study reflected on the competitive edge that industry engagement provided for them post-PhD.

Discussion

In this systematic literature review, we have highlighted some key challenges that HDR students encounter. A prescient finding is that the quality of the relationship between the student and their supervisor, their university, and their peers are strongly associated with a positive student experience. Drawing on motivational theories such as self-determination theory (SDT; Ryan & Deci, Citation2017) that emphasise individual autonomy may offer opportunities to provide a framework of support for students. For example, a study by Litalien and Guay (Citation2015) using measures derived from SDT research and a sample of 1482 PhD students found evidence that perceptions of reduced competence (e.g., lack of confidence, limited progress, not presenting their research to peers) predicted attrition from PhD studies. Such student perceptions were derived from a controlling or impersonal motivational climate (e.g., quality of supervisory relationship). In contrast, the provision of an autonomy-supportive environment (e.g., demonstrating care and kindness, providing relevant structure and training, offering choice rather than control) predicted the completion of studies due to enhanced autonomous motivation and self-regulation of doctoral research. Based on the key findings from this review, we suggest that training could be provided to supervisors around the importance of providing support for autonomous motivation and would likely enhance the student experience and in turn student success. We note that good supervisory practice frameworks do currently exist (e.g., The UK Council for Graduate Education and the Australian Council for Graduate Research). These frameworks could be further adapted to include an SDT theoretical lens that frames relationships more specifically. Such training would involve promoting the importance of student autonomy (as opposed to supervisor control), awareness of kindness and the need to belong, and providing structure and constructive feedback to help with progression.

The importance of peer support should not be underestimated. A number of scholars have highlighted the positive role that writing groups and community of practices have in the peer support for HDR students (e.g., Beasy et al., Citation2020). We would suggest that again an SDT informed approach to designing writing groups would be helpful. For example, framing the group around mutual autonomy where the students’ guide the content and direction of the group writing as opposed to setting pressured targets would likely lead to success.

Future work, implications, and limitations

This review has brought together a body of existing work and has explored the key themes in findings shared across the 68 academic journal articles. Its strength is therefore in reconciling a disparate body of work adopting divergent methodologies and providing a summative account of HDR students’ experiences in Australia, although the themes identified would be beneficial beyond Australian contexts. Limitations of the work include the focus on academic peer reviewed journals, which was adopted due to the voluminous proportions of search returns. The inclusion of only peer reviewed articles provided a focus on rigorous research and the best possible summary of contemporary understandings. Similarly, the decision to include only those articles written in English may have excluded some reports, especially about the experiences of international students. One aspect worthy of explicit future exploration that did not emerge as a key focus in the present review is the role of scholarships and how they might differentially impact student experience. We suggest that the themes identified from this review can inform research leadership and supervisors in developing interventions to support richer HDR experiences within their institutions.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (31.2 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Research Librarian, Dr Tricia Kelly for their assistance in formulating the search parameters.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- *Abdullah, M. N. L. Y., & Evans, T. (2012). The relationships between postgraduate research students’ psychological attributes and their supervisors’ supervision training. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 31, 788–793. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.12.142

- *Ai, B. (2017). Constructing an academic identity in Australia: An autoethnographic narrative. Higher Education Research & Development, 36(6), 1095–1107. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2017.1303459

- *Aitchison, C., & Mowbray, S. (2013). Doctoral women: Managing emotions, managing doctoral studies. Teaching in Higher Education, 18(8), 859–870. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2013.827642

- Aromataris, E. M. Z. E., & Munn, Z. (2020). JBI manual for evidence synthesis. JBI. https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL

- *Bamgboje-Ayodele, A., Ye, M., Almond, H., & Sakulwichitsintu, S. (2016). Inside the minds of doctoral students: Investigating challenges in theory and practice. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 11, 243–267. https://doi.org/10.28945/3542

- *Barry, K. M., Woods, M., Warnecke, E., Stirling, C., & Martin, A. (2018). Psychological health of doctoral candidates, study-related challenges and perceived performance. Higher Education Research & Development, 37(3), 468–483. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2018.1425979

- *Beasy, K., Emery, S., & Crawford, J. (2021). Drowning in the shallows: An Australian study of the PhD experience of wellbeing. Teaching in Higher Education, 26(4), 602–618. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2019.1669014

- Beasy, K., Emery, S., Dyer, L., Coleman, B., Bywaters, D., Garrad, T., Crawford, J., Swarts, K., & Jahangiri, S. (2020). Writing together to foster wellbeing: Doctoral writing groups as spaces of wellbeing. Higher Education Research & Development, 39(6), 109–1105. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1713732

- Bendix Petersen, E. (2012). Re-signifying subjectivity? A narrative exploration of ‘non-traditional’ doctoral students' lived experience of subject formation through two Australian cases. Studies in Higher Education, 39(5), 823–834. http://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2012.745337

- *Berridge, S. (2008). What does It take? Auto/biography as performative PhD thesis. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 9(2), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-9.2.379

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- *Chapman, A., & Pyvis, D. (2005). Identity and social practice in higher education: Student experiences of postgraduate courses delivered ‘offshore’ in Singapore and Hong Kong by an Australian university. International Journal of Educational Development, 25(1), 39–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2004.05.003

- *Cotterall, S. (2011). Doctoral pedagogy: What do international PhD students in Australia think about it? Pertanika Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 19(2), 521–534. http://www.pertanika.upm.edu.my/resources/files/Pertanika%20PAPERS/JSSH%20Vol.%2019%20(2)%20Sep.%202011%20(View%20Full%20Journal).pdf

- *Cotterall, S. (2015). The rich get richer: International doctoral candidates and scholarly identity. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 52(4), 360-370. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2013.839124

- *Crossman, J. (2005). Work and learning: The implications for Thai transnational distance learners. International Education Journal, 6(1), 18-29. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ854952.pdf

- *Cumming, J. (2009). The doctoral experience in science: Challenging the current orthodoxy. British Educational Research Journal, 35(6), 877–890. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920902834191

- Dai, K., & Hardy, I. (2021). The micro-politics of cultural change: a Chinese doctoral student’s learning journey in Australia. Oxford Review of Education, 47, 243–259.

- *Davis, D. (2019). Students’ perceptions of supervisory qualities: What do students want? What do they believe they receive? International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 14, 431-464. https://doi.org/10.28945/4361

- Department of Education and Training. (2018). Research Training Implementation Plan Progress Report. July 2018. https://www.dese.gov.au/higher-education-reviews-and-consultations/resources/rtip-progress-report-july-2018

- DESE. (2019). 2019 Higher degree by research student population of Australian universities. https://www.dese.gov.au/download/4100/2019-higher-degree-research-student-population/6075/document/pdf

- DESE. (2020). Enrolments time series, student enrolments by equity groups. https://www.dese.gov.au/higher-education-statistics/student-data/selected-higher-education-statistics-2020-student-data-0

- *Devenish, R., Dyer, S., Jefferson, T., Lord, L., van Leeuwen, S., & Fazakerley, V. (2009). Peer to peer support: The disappearing work in the doctoral student experience. Higher Education Research & Development, 28(1), 59–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360802444362

- *Dickie, C. (2011). Winning the PhD game: Evocative playing of snakes and ladders. Qualitative Report, 16(5), 1230–1244. http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ941701.pdf

- *Due, C., Zambrano, S. C., Chur-Hansen, A., Turnbull, D., & Niess, C. (2015). Higher degree by research in a foreign country: A thematic analysis of the experiences of international students and academic supervisors. Quality in Higher Education, 21(1), 52–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/13538322.2015.1032002

- *Fotovatian, S., & Miller, J. (2014). Constructing an institutional identity in university tea rooms: The international PhD student experience. Higher Education Research & Development, 33(2), 286–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2013.832154

- *Fung, A. S. K., Southcott, J., & Siu, F. (2017). Exploring mature-aged students’ motives for doctoral study and their challenges: A cross border research collaboration. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 12, 175–195. https://doi.org/10.28945/3790

- *Guerin, C., & Green, I. (2015). ‘They’re the bosses’: Feedback in team supervision. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 39(3), 320–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2013.831039

- *Halbert, K. (2015). Students’ perceptions of a ‘quality’ advisory relationship. Quality in Higher Education, 21(1), 26–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/13538322.2015.1049439

- *Harman, G. (2003a). International PhD students in Australian universities: Financial support, course experience and career plans. International Journal of Educational Development, 23(3), 339–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0738-0593(02)00054-8

- *Harman, G. (2003b). Phd student satisfaction with course experience and supervision in two Australian research-intensive universities. Prometheus, 21(3), 317–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/0810902032000113460

- *Harman, K. (2002). The research training experiences of doctoral students linked to Australian cooperative research centres. Higher Education, 44(3/4), 469–492. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1019894323421

- *Hutchings, K., Bodle, K., & Miller, A. (2018). Opportunities and resilience: Enablers to address barriers for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to commence and complete higher degree research programs. Australian Aboriginal Studies, 2, 29–49. https://search.informit.org/doi/epdf/10.3316informit.106269539902101

- *Ives, G., & Rowley, G. (2005). Supervisor selection or allocation and continuity of supervision: Ph.D. Students’ progress and outcomes. Studies in Higher Education, 30(5), 535–555. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070500249161

- *Jones, A., & Blass, E. (2019). The impact of institutional power on higher degree research supervision: Implications for the quality of doctoral outcomes. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 7(7), 1485–1494. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2019.070702

- *Jowsey, T., Corter, A., & Thompson, A. (2020). Are doctoral theses with articles more popular than monographs? Supervisors and students in biological and health sciences weigh up risks and benefits. Higher Education Research & Development, 39(4), 719–732. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1693517

- *Kefford, G., & Morgenbesser, L. (2013). Bridging the information gap: A survey of politics and international relations PhD students in Australia. Australian Journal of Political Science, 48(4), 507–518. https://doi.org/10.1080/10361146.2013.840431

- *Klenowski, V., Ehrich, L., Kapitzke, C., & Trigger, K. (2011). Building support for learning within a doctor of education programme. Teaching in Higher Education, 16(6), 681–693. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2011.570431

- Lasen, M., Evans, S., Tsey, K., Campbell, C., & Kinchin, I. (2018). Quality of WIL assessment design in higher education: A systematic literature review. Higher Education Research & Development, 37(4), 788–804. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2018.1450359

- Lee, E., Blackmore, C., & Seal, E. (2013). Research journeys: A collection of narratives of the doctoral experience. Cambridge Scholars.

- Litalien, D., & Guay, F. (2015). Dropout intentions in PhD studies: A comprehensive model based on interpersonal relationships and motivational resources. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 41, 218–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2015.03.004

- *Ma, L. P. F. (2021). Writing in English as an additional language: Challenges encountered by doctoral students. Higher Education Research & Development, 40(6), 1176–1190. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1809354

- Macoun, A., & Miller, D. (2014). Surviving (thriving) in academia: Feminist support networks and women ECRs. Journal of Gender Studies, 23(3), 287–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2014.909718

- *Maher, D., Seaton, L., McMullen, C., Fitzgerald, T., Otsuji, E., & Lee, A. (2008). ‘Becoming and being writers': The experiences of doctoral students in writing groups. Studies in Continuing Education, 30(3), 263–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/01580370802439870

- *Manathunga, C., Pitt, R., & Critchley, C. (2009). Graduate attribute development and employment outcomes: Tracking PhD graduates. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 34(1), 91–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930801955945

- *Mantai, L. (2019). ‘A source of sanity': The role of social support for doctoral candidates’ belonging and becoming. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 14, 367–382. https://doi.org/10.28945/4275

- *Mason, S. (2018). Publications in the doctoral thesis: Challenges for doctoral candidates, supervisors, examiners and administrators. Higher Education Research & Development, 37(6), 1231–1244. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2018.1462307

- *Mason, S., Morris, J. E., & Merga, M. K. (2021). Institutional and supervisory support for the thesis by publication. Australian Journal of Education, 65(1), 55–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004944120929065

- McAlpine, L., & Amundsen, C. (2011). To be or not to be? The challenges of learning academic work. In L. McAlpine & C. Amundsen (Eds.), Doctoral education: Research-based strategies for doctoral students, supervisors and administrators (pp. 1–13). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0507-4

- McGagh, J., Marsh, H., Western, M., Thomas, P., Hastings, A., Mihailova, M., … Wenham, M. (2016). Review of Australia’s Research Training System. Australian Council of Learned Academies (ACOLA).

- *Merga, M. K. (2015). Thesis by publication in education: An autoethnographic perspective for educational researchers. Issues in Educational Research, 25(3), 291–308. http://www.iier.org.au/iier25/merga.pdf

- Merga, M. K., Mason, S., & Morris, J. E. (2019). ‘The constant rejections hurt’: Skills and personal attributes needed to successfully complete a thesis by publication. Learned Publishing, 32(3), 271–281. https://doi.org/10.1002/leap.1245

- *Merga, M. K., Mason, S., & Morris, J. E. (2020). ‘What do I even call this?’ challenges and possibilities of undertaking a thesis by publication. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 44(9), 1245–1261. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2019.1671964

- *Morris, S., Pitt, R., & Manathunga, C. (2012). Students’ experiences of supervision in academic and industry settings: Results of an Australian study. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 37(5), 619–636. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2011.557715

- *Naylor, R., Chakravarti, S., & Baik, C. (2016). Differing motivations and requirements in PhD student cohorts: A case study. Issues in Educational Research, 26(2), 351–367. http://www.iier.org.au/iier26/naylor.pdf

- *Nguyen, B. T. T., & Pennycook, A. (2018). Dancing, google and fish sauce: Vietnamese students coping with Australian universities. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 38(4), 457–472. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2018.1493981

- *Nomnian, S. (2017). Thai PhD students and their supervisors at an Australian university: Working relationship, communication, and agency. PASAA: Journal of Language Teaching and Learning in Thailand, 53, 26–58. http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1153678.pdf

- *Owens, A., Brien, D. L., Ellison, E., & Batty, C. (2020). Student reflections on doctoral learning: Challenges and breakthroughs. Studies in Graduate and Postdoctoral Education, 11(1), 107–122. https://doi.org/10.1108/SGPE-04-2019-0048

- *Parker, R. (2009). A learning community approach to doctoral education in the social sciences. Teaching in Higher Education, 14(1), 43–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510802602533

- *Roach, A., Christensen, B. K., & Rieger, E. (2019). The essential ingredients of research supervision: A discrete-choice experiment. Journal of Educational Psychology, 111(7), 1243–1260. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000322

- *Robertson, M. (2017). Aspects of mentorship in team supervision of doctoral students in Australia. Australian Educational Researcher, 44(4-5), 409–424. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-017-0241-z

- *Ross, P. M., Burgin, S., Aitchison, C., & Catterall, J. (2011). Research writing in the sciences: Liminal territory and high emotion. Journal of Learning Design, 4(3), 14–27. http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ940645.pdf

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. The Guilford Press.

- *Satariyan, A., Getenet, S., Gube, J., & Muhammad, Y. (2015). Exploring supervisory support in an Australian university: Perspectives of doctoral students in an education faculty. Journal of the Australia and New Zealand Student Services Association, 46, 1–12. https://www.anzssa.com/public/94/files/JANZSSA%20editions/JANZSSA%20October%202015_Number%2046.pdf

- *Shen, C. (2008). Chinese research students’ adjustment to the Australian learning environment. International Journal of Learning, 15(1), 43–50. https://doi.org/10.18848/1447-9494/CGP/v15i01/45381

- *Son, J.-B., & Park, S.-S. (2014). Academic experiences of international PhD students in Australian higher education: From an EAP program to a PhD program. International Journal of Pedagogies & Learning, 9(1), 26–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/18334105.2014.11082017

- *Stewart, R. A., & Chen, L. (2009). Developing a framework for work integrated research higher degree studies in an Australian engineering context. European Journal of Engineering Education, 34(2), 155–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/03043790902833325

- *Stylianou, M., Enright, E., & Hogan, A. (2017). Learning to be researchers in physical education and sport pedagogy: The perspectives of doctoral students and early career researchers. Sport, Education and Society, 22(1), 122–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2016.1244665

- *Taylor, A., Millei, Z., Partridge, L., & Rodriguez, L. (2004). The getting of access: The trials and tribulations of the novice researcher. Issues In Educational Research, 14(1), 85–102. http://www.iier.org.au/iier14/taylor.html

- Torka, M. (2020). Change and continuity in Australian doctoral education: PhD completion rates and times (2005-2018). Australian Universities’ Review, 62(2), 69–82. https://aur.nteu.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/AUR-62-02.pdf

- *Trudgett, M. (2009). Build it and they will come: Building the capacity of Indigenous units in universities to provide better support for Indigenous Australian postgraduate students. Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 38(1), 9–18. https://doi.org/10.1375/S1326011100000545

- *Trudgett, M. (2011). Western places, academic spaces and Indigenous faces: Supervising Indigenous Australian postgraduate students. Teaching in Higher Education, 16(4), 389–399. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2011.560376

- *Trudgett, M. (2014). Supervision provided to Indigenous Australian doctoral students: A black and white issue. Higher Education Research & Development, 33(5), 1035–1048. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2014.890576

- *Usher, W., & McCormack, B. A. (2021). Doctoral capital and well-being amongst Australian PhD students: Exploring capital and habitus of doctoral students. Health Education, 121(3), 322–336. https://doi.org/10.1108/HE-11-2020-0112

- Wang, T., & Li, L. Y. (2011). “Tell me what to do” vs. “Guide me through it". Feedback Experiences of International Doctoral Students. Active Learning in Higher Education, 12(2), 101–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787411402438

- *Winchester-Seeto, T., Homewood, J., Thogersen, J., Jacenyik-Trawoger, C., Manathunga, C., Reid, A., … Holbrook, A. (2014). Doctoral supervision in a cross-cultural context: Issues affecting supervisors and candidates. Higher Education Research & Development, 33(3), 610–626. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2013.841648

- *Yarlagadda, P. K. D. V., Sharma, J., Silva, P., Woodman, K., Pitchforth, J., & Mengersen, K. (2018). Factors influencing the success of culturally and linguistically diverse students in engineering and information technology. International Journal of Engineering Education, 34(4), 1384–1399. https://eprints.qut.edu.au/223993/

- *Yeoh, J. S. W., D. Thao. (2012). International research students’ perceptions of quality supervision. International Journal of Innovative Interdisciplinary Research, 1(3), 10–18. https://www.auamii.com/jiir/Vol-01/issue-03/2Yeoh.pdf.

- Yim, L., & Waters, L. (2013). The role of interpersonal comfort, attributional confidence, and communication quality in academic mentoring relationships. Education Research and Perspectives, 40, 58–85. https://search.informit.org/doi/epdf/10.3316/aeipt.203881

- *Yu, B., & Wright, E. (2016). Socio-cultural adaptation, academic adaptation and satisfaction of international higher degree research students in Australia. Tertiary Education & Management, 22(1), 49–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/13583883.2015.1127405

- *Zeivots, S. (2021). Outsiderness and socialisation bump: First year perspectives of international university research students. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 41(2), 385–398. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2020.1779028