ABSTRACT

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced universities worldwide to deliver emergency remote online teaching and learning. This study analyses teaching practices at a globally ranked Australian university. These practices were adopted to develop connection with students in the absence of face-to-face learning. Complex adaptive system theory is applied, and a mixed research method adopted to examine the evolution of the remote classroom and to understand behaviour as a process of self-organisation. We find that social connection is the underlying mechanism by which the classroom evolved to meet the learning outcomes within the remote online teaching and learning environment. In response to initial transition and institutional pressures, educators attempted to replicate online their work in a face-to-face environment, creating surrogate social connectedness. Our study findings not only extend the literature on the continuing impact of the pandemic on higher education but also highlight the need for pedagogy to drive change and the importance of social connectedness.

1. Introduction

Since 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic forced universities around the world to transition to emergency remote online teaching and learning. Although online teaching is not new, the pace at which universities had to transform their ways of engaging with students is an entirely new experience. We use the term ‘emergency remote teaching and learning’ (ERTL), following extant researchers to signify the environment created as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. This differentiates it from ‘traditional’ online learning that emanates from careful instructional design using a systematic model (Aguilera-Hermida, Citation2020; Ali, Citation2020; Evans et al., Citation2020; Hodges & Fowler, Citation2020; McGaughey et al., Citation2021; Naylor & Nyanjom, Citation2021; Tharapos et al., Citation2022; Watermeyer et al., Citation2021). As we move beyond this interim emergency setting, it is important to understand the lessons learned from an educator and student perspective, with a particular focus on the critical role ‘connection’ plays in higher education.

Connection in education can include connecting with concepts, connecting with technology, connecting with oneself, and connecting with others. Connection is often recognised as a prerequisite for engagement, with both factors deemed necessary for positive student and educator learning experiences (Baron & Corbin, Citation2012; Devlin & Samarawickrema, Citation2022; Kahu & Nelson, Citation2018). The pandemic not only emphasised that teaching is a complex social cognitive process, but how integral connections are to that sense of belonging, often viewed as precursor for learning (Aldridge, Citation2019; Evans et al., Citation2020; MacMahon et al., Citation2020). For this study, as a starting point we consider social connection as the interpersonal and interdependent closeness between educators and students and amongst students that results in the experience of belonging to and engaging in the education community (Green et al., Citation2020).

In addition to social connection, student engagement is also an essential condition for learning, with observable engagement ‘behaviours’ including class attendance, listening and participating in class discussion and interacting with peers typical of highly motivated students (Aldridge, Citation2019). Yet student engagement and its importance to education is not just about visible behaviours; motivated quiet students can be hidden from view in any mode of delivery. Therefore, ‘engagement’ is a multi-faced concept that is not just about demonstrating engaged behaviour, rather it entails engaging at a level that involves cognitive and emotional factors. Kahu’s (Citation2013) conceptual framework for student engagement notes that when students are emotionally and cognitively connected to their educators, their peers, the learning concepts and institution, it often results in active engagement that promotes students’ learning success. More recently, a study by Tai et al. (Citation2019) identifies how students engage, interact, develop connections and participate in online learning activities, finding that student engagement is complex, particularly in relation to attendance and participation in remote online settings. Other relevant studies include that by Naylor and Nyanjom (Citation2021), who outline educators’ frustration at students who do not engage or participate actively in class discussions, and McGaughey et al.’s (Citation2021) survey of Australian educators, which reveals challenges in forming connections to universities, both for students and educators. In a recent study of education in the post-Covid era, Devlin and Samarawickrema (Citation2022) argue that effective teaching practices must continue to evolve and respond to changing contexts.

In an international student context (both pre- and post-ERTL), social connectedness is often perceived as essential in easing negative feelings and experiences in an unfamiliar country, with belonging and connections with others potentially shaping students’ success (Willoughby-Knox & Yates, Citation2021). TEQSA’s (Citation2020) Student Perceptions of Online Learning Quality Project highlights the importance of connection to teaching practice, with the top three student ‘connection concerns’ including: lack of engagement, lack of interaction with academics and insufficient peer interaction.

This study extends these previous studies, taking a novel approach to explore the challenges faced by educators and students transitioning to an ERTL context. It applies a complex adaptive system (CAS) theory lens to argue that teaching and learning (T&L) taking place in a classroom is a complex social phenomenon that evolves over time. We conceptualise the remote classroom as a CAS to explain the adaptations and processes taking place within the ERTL transition. We argue that educational practices observed in the remote classroom are deeply rooted in social connection and that social connection is the underlying mechanism by which the classroom adapts within the remote environment. That is, social connection underlies the adaptation of educational practices aiming to sustain engagement in the ERTL context. To explore the conditions and interactions within the ERTL classroom to explain these adaptive educational practices, we ask the following research questions:

How did educators and students respond and engage in the ERTL context?

How did social connection occur in the ERTL context?

2. Theoretical framework

2.1. Complex adaptive systems theory

Since the 1990s, researchers have utilised CAS theory as a framework to investigate complex dynamic phenomena in organisations and society, especially in response to changing conditions (Alaa & Fitzgerald, Citation2013; Dooley, Citation1997; Gell-Mann, Citation1994; Holland, Citation2006). CAS principles have been widely applied in management, social science and information systems, among others, to understand and explain the dynamic behaviour of complex systems (Kariippanon et al., Citation2020; Schneider & Somers, Citation2006), with some studies finding that the most productive state for a system is at the ‘edge of chaos’ (Levin, Citation1998, p. 431).

Holland (Citation2006, p. 1) suggests that CAS ‘are systems that have a large number of components, including agents, that interact and adapt or learn’, leading to systems behaviour that is unpredictable. Complexity results from the interaction and interconnectivity of the elements within a system and between a system and its environment. This implies that a decision or action by one component within a system influences all other related components but not in any uniform manner. CAS are therefore characterised by a high degree of adaptive capacity, giving them resilience in the face of environment perturbation.

Agents (i.e., system components) are the building blocks of CAS (Dooley, Citation1997), possessing intrinsic attributes and cognitive abilities that drive unpredictable actions and interactions, which in turn result in a process of self-organisation. Self-organisation is defined as the ability of a CAS to evolve in an organised form, through changes to its internal structures and behaviour, often in response to changes in the environment (Anderson et al., Citation2003). Stacey (Citation2007, p. 196) argues that ‘self-organisation is spontaneous and autonomous’. CAS are heavily dependent on initial conditions. Small changes in initial conditions can have a profound impact on overall system behaviour, or vice-versa, as described in the butterfly effect (Lorenz, Citation1960), where changes in initial conditions directly impact the way agents act and interact, in turn, shaping changes in internal structures and/or new patterns of behaviour.

The use of CAS in education studies is more recent and limited (Burns & Knox, Citation2011; Raduescu et al., Citation2016; Wang et al., Citation2015). In this study, we adapt Burns and Knox’s (Citation2011) conceptualisation of the classroom as a CAS, according to which classroom processes (i.e., teaching and learning (T&L) practices) are highly dependent on agents’ actions and interactions (e.g., educators and students) within the classroom, and the outcomes of T&L practices, in turn, are highly dependent on educators and students’ interactions. We suggest that CAS is a suitable theory to understand the adaptation of T&L practices, because the classroom is a process of self-organisation in response to changes to initial conditions (e.g., COVID-19 pandemic).

2.2. The classroom as a complex adaptive system

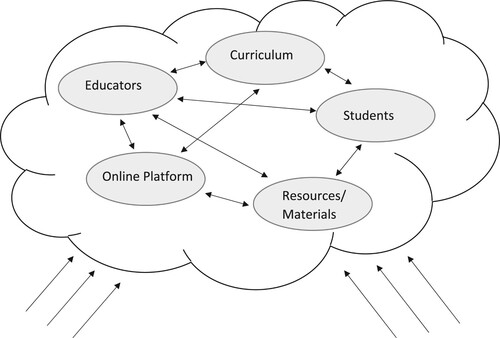

illustrates the five main components of a classroom. The main aim of a classroom is to achieve course-specific learning outcomes through interactions among five main components.

Curriculum is a structural component that guides the development and implementation of T&L practices, such as activities and resources. Educators and students are the main agents interacting in the classroom. Agents play a significant role because their actions and interactions influence the behaviour and outcomes of the classroom (i.e., the CAS). Educators monitor students’ achievements and, based on their progress, can adapt current classroom practices or design and implement interventions to ensure that required outcomes are achieved. Resources and materials (e.g., lecture notes, lecture recordings, assessments, etc.) are components carefully designed and utilised by educators using their experience and knowledge. The online platform is a structural component in which the T&L practices take place, in our context in lieu of the traditional physical classroom.

Of particular interest to our study is how educators and students engage in T&L practices via their actions and interactions with the other classroom components. We interpret these interactions and the resulting changes to the classroom structure and behaviour by applying a CAS lens to shed light on the process of classroom self-organisation.

3. Methodology

We utilise a qualitative research method (Reyad et al., Citation2020), appropriate to understanding a complex phenomenon within the ERTL context, and this study is part of a larger research project that began with surveying students and educators. For this study, we collected data throughout 2020 via 7 focus groups with a total of 25 students, and in-depth interviews with 23 educators, 11 from the Accounting discipline and 12 from the Business Information Systems (BIS) discipline. We utilised an interpretive approach, allowing researchers to unpack and understand educators’ and students’ experiences in their transition to the ERTL context.

3.1. Participants

Upon receiving ethics approval (Project 2020/385), we identified all semester 1 and 2, 2020 undergraduate and postgraduate students enrolled in units of study from two of the largest disciplines (Accounting and Business Information Systems (BIS)) in an Australian business school, including units coordinated by the researchers. To avoid bias and coercion in data collection, student email lists were downloaded from the university timetabling system and educator email lists were downloaded from University Outlook distributions lists accessible to all University staff. The email lists were provided to an independent research assistant who then sent invitation emails to students and educators to participate in initial surveys. At the completion of the survey conducted in semester 1 2020, the participants were invited to volunteer for an interview (educators) and focus groups (students). The research assistant managed the entire follow-up correspondence and conducted all the focus groups on their own.

All focus groups with students were conducted via Zoom in the latter half of 2020. All interviews with educators were conducted via Zoom by the research assistant and one researcher during November and December 2020. All interviewed educators, despite having limited experiences with ERTL, had significant experience with course coordination, content design and delivery.

In compliance with the ethics requirements, all audio files and transcripts were maintained by the research team and stored on a secured university research data storage platform. Although the student participants were either undergraduate or postgraduate, and in various stages of their degree, the experience of ERTL was new to them. Therefore, the study was not intended to compare the cohorts, but to understand their experience as a whole student cohort in the ERTL context.

3.2. Process

Student focus group and educator interview questions were informed by the ERTL literature (Burgess & Sievertsen, Citation2020; Ferri et al., Citation2020; MacMahon et al., Citation2020), earlier surveys conducted in early 2020 by the researchers, and our longstanding experience as educators. Whilst prompting different perspectives, the questions covered similar themes for both students and educators. They included preparation for the transition to remote teaching and learning, the delivery of teaching and learning (assessments, engagement and participation), and key aspects of social learning (motivation, social connections and engagement with learning community).

We asked students in focus groups (N = 25) to elaborate on these themes with a number of leading questions linked to each theme, which allowed respondents to interpret and explain their experience (see ).

Table 1. Major themes and questions for student focus groups.

We interviewed educators (N = 23) during open-ended interviews of 46 min on average. In eliciting the educators’ experiences, we were guided by the themes and questions provided in . All interviews and focus groups conducted over Zoom were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim, with transcripts then imported into NVivo 10.0 software for coding of recurring and overlapping themes, with intercoder reliability checked by researchers.

Table 2. Major themes and questions for educator interviews.

4. Findings

Our findings indicate that social connection is the underlying mechanism that maintained educators' and students’ engagement within the remote classroom. Social connection is deeply embedded in the classroom self-organisation process during the transition from traditional to remote classroom context. Social connection occurred through the adaptation of educational practices in response to the need to maintain engagement within the remote classroom. We find that classroom self-organisation was the result of educators’ beliefs that for learning to be effective, it is essential to engage and connect with students and, in turn, students need to engage and connect with educators and their peers as indicated in our discussion below. We expand on these findings in the following subsections, applying the framework of CAS.

4.1. Adapting T&L practices and resources to achieve social connection

We suggest that the classroom self-organisation process follows four stages as presented in . Our focus is on the first two stages taking place during 2020, with the last two evolving beyond the immediate response from 2020.

Within each stage, we discuss three CAS-related aspects: initial conditions as context; educators and students’ actions and interactions, and the results of these interactions as system behaviour.

4.1.1. Stage 1: Respond to crisis

4.1.1.1. Context

Facing a novel context, the COVID-19 pandemic, educators had a very short time to transition to ERTL. A number of institutional challenges constrained the way educators could successfully implement the transition. First, they had a significant international student cohort, and some of these students were less open to engaging in a remote environment, with some 18% of students deciding to postpone their studies from semester 1 to 2 in 2020. However, this did not impact our study, as the focus groups had a mix of local and international students located both in Australia and overseas. Second, there was limited educational design support and resources available to educators: ‘felt very unsupported, every one of us felt a bit the same, that we were dumped into this and kind of left to survive like you are in a Shark Tank’. Third, strict financial austerity measures were implemented limiting access to teaching support (e.g., fewer tutors). Fourth, a number of technological factors, such as Zoom being the institutional choice and a push to use multiple online tools, many on the basis of trial and error, limited what educators could achieve pedagogically in a short time. Several educators responded:

worried about the internet connection, and so I think that makes me frightened to try new things.

I did the minimum changes like changing tutorials to zoom.

removed some of the interactive components because it is simply not fit for an online model. planned to do homework through the online textbook questions but discontinued it in week three because there was so many problems and mistakes with the answers … number of emails I got just wasn’t worth it.

Educators responded that they were driven by two imperatives: (1) to reduce students’ stress and fear of the unknown; and (2) to make students feel comfortable and connected with the learning process in the new environment as several educators noted:

I tell my students always that this is a space where you can try and make mistakes.

I try to be social and like tell them it’s my cat’s birthday.

I started forcing them to turn on the camera, and to unmute and talk to each other rather than use the chat function.

I tried to grab their attention, nice makeup, hand gestures, and social conversations.

connection means my ability of sending students this message to come on board on a journey with me, I want to get them from point A to point B with some transformation … inspire them to be passionate about what they are learning.

I try to promote this idea of community and connection, so we actually posted announcement to say ‘distancing’ is not a real word [making students feel comfortable].

4.1.1.2. Planning new remote practices (actions and interactions of educators and students)

As educators had different levels of pedagogical experience and expertise, their decisions to adapt T&L practices were unpredictable and inconsistent:

brought in participation marks in tutorials, something that I don’t agree with.

the type of questions I asked changed because of the technology … shorter questions, pieces of it rather than the full process.

I was so focused on designing something for the online space that I threw out all my techniques of knowing people’s names, developing rapport with students.

I went with a very conservative approach … to ensure assessments maintain a quality standard.

no change in approach as its already high engagement style where students have to prepare in advance.

I thought this Google drive and having students annotate and draw things would be useful because in a F2F classroom I have butcher papers and I get them to draw. So, I tried to mimic that, but of course it’s not the same with technology.

no matter what technology out there, nothing beats the basics sticky notes, pens and social movement … the challenge of being inquisitive, being curious, becoming more innovative … those skills will not be developed by sitting in front of a computer with technology.

… advocate of technology but you need human contact and human to human interaction.

it’s case study based so the core of the unit is actual contact in class with groups working together, lecturer’s role is to basically coach/facilitate conversations … we were struggling to engage with them online … it wasn’t an environment where we could continue in terms of running the standard assessments and standard teaching.

As a far as changing my pedagogical approach, yes, I did, for the very first time, I brought in participation marks in tutorials, which is something that I don’t agree with, because I think it’s an attendance mark.

We found that students, the other key actors, responded relatively well to educators’ practices because it was a novel situation. They trusted educators and accepted remote classroom practices. Initially, students felt the remote classroom was an interim classroom, and were hesitant to connect with their peers with many students claiming ‘don’t have much connections with my peers as I do not know them’. As the remote classroom progressed into the year, this evolved to become a deep absence of student-to-student (S2S) interactions, leading to isolation and limited social connection.

4.1.1.3. Result: community of educators ‒ a new informal internal structure

In the absence of educational design support, limited resources and time pressure, educators felt left alone in making pedagogical decisions within a new context. In response, many turned to their colleagues to seek advice about how to adapt their T&L practices. An informal community of educators emerged where educators expressed their feelings of concern. This led to collective decisions to maintain the status quo of most T&L practices: ‘we leaned on fellow lecturers, and we basically had a big, like counselling group, I think you could call it that, but essentially, we taught each other’. In doing so, educators minimised the impact of change because they were concerned about how their students would cope.

Interestingly, by creating an informal community, educators’ responses were the opposite of students. While many students withdrew from interactions educators strengthened their educator to educator (E2E) connections, feeling ‘more connected with colleagues with regular online meetings’.

4.1.2. Stage 2: Recreate the human touch (new remote practices)

Many educators acknowledged and identified human touch and movement as integral in how they create and connect with students. Hence, they viewed the online transition as a barrier and lack of participation problematic: ‘as a human being I find it very hard … I’ve tried so many things and there comes a point where the lack of participation is slightly offensive’. Another educator noted ‘online is only upper body acting, whereas in the physical classroom, the movement, the authentic reactions, the hand gestures, the facial cues are real and powerful’. These responses support the view that human touch is a fundamental language of connection with others (Gao et al., Citation2022; Marshall et al., Citation2022; Naylor & Nyanjom, Citation2021).

4.1.2.1. Context

The context did not change over time as it became clear the pandemic was not a short-term situation. Students continued to be isolated in their home country and ERTL started to emerge as a delivery mode that might co-exist with F2F delivery. In Stage 2, educators noticed increasing student withdrawal and isolation, which was echoed by student focus group comments:

felt lonely and isolated with no free time to chat.

I was feeling lonely a lot and it did affect my mental health.

I don’t do networking at all, but I feel now this path is cut down and I have to find something else.

4.1.2.2. New Remote Practices (new patterns of behaviour resulting from actions and interactions)

In response to the lack of S2S interactions, educators started to embed more social connection and interactions by further adapting their T&L practices. They emphasised the need for students to engage and learn from each other, which they believed would improve students’ performance. Educators leveraged the value of real connections in the F2F classroom, developing strategies to achieve a more personalised connection with students in the remote classroom:

used Microsoft Teams not just as a professional platform but a communication platform to engage in banter with students on random things.

I talked to them like I was talking in the classroom, through a video each week with recap Qs.

Our analysis shows that educators saw engagement as essential and necessary to sustain educator-to-student (E2S) connections in the remote classroom. Their adapted T&L practices emphasised attempts to develop closeness to students (e.g., checking regularly on students, something they previously achieved by walking around in the physical classroom), as well as creating an inclusive environment inside the remote classroom. For instance, one educator reflected that they ‘put marks on the engagement with the participation each week’ while another ‘provided four online quizzes to keep them up to date with the content each week’.

In fulfilling their duty of care, in most instances, educators did not make many changes to the actual T&L content and assessment. Some commonly implemented changes were mini recorded lectures to address students’ attention span and cognitive load. Some educators enabled more exam preparation by providing ‘lots of practice questions so that they can go into the exam feeling more confident’.

As the S2S lack of interaction deepened over time, students started to crave interaction and turned their attention to educators. Students acknowledged educators’ efforts and duty of care, as indicated in their perceptions that educators adapted classroom practices to make remote learning more comfortable (e.g., students acknowledged the detailed feedback and help in their learning, assessment changes to minimise cognitive and information overload). They trusted educators and acknowledged educators’ efforts to link participation to achievement, for example, saying ‘[teachers] feeling stressful because they don’t actually see students’ eye and their faces making it hard to tell whether they can fully understand the materials’. More engaging student-to-educator (S2E) connection was observed over time, with some students noting ‘from week six onwards, I started like talking and you know interacting more, with camera on’. Some students misconstrued engagement attempts, adopting a behavioural, rather than a cognitive response: ‘I participate more by placing Qs in the chat function just to be noticed’ and ‘try and participate as much as I can and ask as many questions as I can during class, but staying engaged was hard in the online space as you get distracted like going to Facebook’.

Despite various efforts to increase social connection in the remote classroom, most educators felt they were doing the hard work to make this happen. They were aware of the importance of building a rapport with students and for students to actively participate in T&L activities, however were often thwarted by students’ behaviour, which was an attempt to show, rather than do engagement, limiting their ability to reach their learning potential (Naylor & Nyanjom, Citation2021).

Our findings suggest that students developed their own study practices to cope with the adapted T&L practices in the remote classroom. They realised the need for self-discipline and autonomy, and acknowledged that more preparation, higher participation and engagement were required to succeed: ‘my engagement with the lecturer and the tutor was much higher just because I attended a lot of consultation sessions to get ahead’. Many students responded positively by engaging more in the classroom to reciprocate educators’ efforts.

Despite aspirations for stronger S2E connections, educators admitted that ultimately students were responsible for this, with one educator claiming, ‘it’s really hard to establish this connection, I think it’s a lot more burden on the student to make sure that the teacher knows them for more than their picture’.

We found that S2S connection continued to suffer over time, due to the physical isolation and lack of campus experience (e.g., social groups, student society events). This led to limited opportunities for students to establish new connections, with those who had studied on campus before relying on their already established connections. A number of students in focus groups claimed:

I felt quite disconnected to my classmates and my lecturers.

I wasn’t active in many societies either … I wasn’t really connected with the community at Uni.

I was connected with people that I knew, um, but there wasn’t much opportunity for me to get connected with others.

4.1.2.3. Result: status quo of classroom

While educators adapted their T&L practices, our findings suggest their aim was to compensate for the absence of F2F social connection, without relying on any specific pedagogical approaches. Educators maintained most of their F2F T&L practices within the remote classroom, because the duty of care for students was their priority and they faced significant time pressure. With some exceptions, most T&L practices maintained the status quo of the traditional classroom.

5. Discussion and conclusion

By employing CAS theory, we have shed light on the process of classroom self-organisation in response to the COVID-19 pandemic to answer our two research questions.

How did educators and students respond and engage in the ERTL context?

How did social connection occur in the ERTL context?

Our findings show the capacity of the classroom, as CAS, to self-organise in response to changes in initial conditions and via agents’ actions and interactions. However, we identify initial conditions, particularly institutional challenges, as constraints, making it difficult for the system (classroom) to evolve. The system (classroom) was further pushed to maintain its status quo because key agents (educators) did not undertake sound pedagogical adaptation of T&L practices but focused instead on a proxy social connection within the remote classroom. Our analysis suggests this shortcoming led to less effective learning (Gao et al., Citation2022; Marshall et al., Citation2022).

Educators recognised the need to achieve social connection in the remote classroom, both to achieve better learning outcomes and because of their sense of duty of care for students. That constraint created only a surrogate social connectedness was to some extent due to educators’ different understandings of what social connection means, which significantly influenced the way they adapted T&L practices. It is also the result of students’ difficulties in forming connections. While all agents recognised that social connection is key to engagement, both for educators and students there was a misunderstanding about what is engagement, with many observing engagement as a behaviour, rather than understanding it as a cognitive activity.

Ultimately, our findings indicate that the remote classroom mostly was a replica of the traditional classroom. The classroom as a system did not change significantly but two observable changes emerged: (1) a new E2E community as a new internal structure; and (2) attempts to develop new T&L practices with a focus on engagement and social connection.

In attempting to identify interactions within the remote classroom in the transition to ERTL, we see that ‘a new pedagogy for higher education may be necessary’ (Devlin & Samarawickrema, Citation2022, p. 27), one that rethinks how best to incorporate engagement and social connection into the T&L experience to enable knowledge and shared learning, especially within new contexts. Our study raises several questions about what the future holds. It seems likely that educators will be expected to deliver a hybrid of online and F2F teaching. How can we, as educators, make the complex social process of T&L work, engaging students and ourselves as part of an education community? One key element of this is better education and training for educators. Another is a shift in mindset. We must overcome our fatigue in the face of constant change and consider the benefits to be gained from an opportunity to rethink education, to move beyond the confines of the classroom, while recognising that as humans we all need ‘social connection’.

Adapting this approach, we see opportunities for future research. As our study data covers the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, 2020, it would be interesting to further examine changes in mechanisms from 2021 and beyond in stages 3 and 4 of the CAS, pushing the system (classroom) towards a new state of equilibrium, which appears to be a mix of F2F and online classroom (see ). A limitation of our research is that it focuses on educators and students in only two business disciplines. It would be interesting to expand this study to other disciplines and contexts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aguilera-Hermida, A. P. (2020). College students’ use and acceptance of emergency online learning due to COVID-19. International Journal of Educational Research Open, 1, 100011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedro.2020.100011

- Alaa, G., & Fitzgerald, G. (2013). Re-conceptualizing agile information systems development using complex adaptive systems theory. Emergence: Complexity & Organization, 15(3), 1–23.

- Aldridge, D. (2019). Reading, engagement and higher education. Higher Education Research & Development, 38(1), 38–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2018.1534804

- Ali, W. (2020). Online and remote learning in higher education institutes: A necessity in light of COVID-19 pandemic. Higher Education Studies, 10(3), 16–25. https://doi.org/10.5539/hes.v10n3p16

- Anderson, R. A., Issel, L. M., & McDaniel Jr, R. R. (2003). Nursing homes as complex adaptive systems: Relationship between management practice and resident outcomes. Nursing Research, 52(1), 12–21. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006199-200301000-00003

- Baron, P., & Corbin, L. (2012). Student engagement: Rhetoric and reality. Higher Education Research & Development, 31(6), 759–772. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2012.655711

- Burgess, S., & Sievertsen, H. H. (2020). Schools, skills, and learning: The impact of COVID-19 on education. Retrieved July, 2021, from https://voxeu.org/article/impact-covid-19-education

- Burns, A., & Knox, J. S. (2011). Classrooms as complex adaptive systems: A relational model. Tesl-Ej, 15(1), n1.

- Devlin, M., & Samarawickrema, G. (2022). A commentary on the criteria of effective teaching in post-COVID higher education. Higher Education Research & Development, 41(1), 21–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2021.2002828

- Dooley, K. J. (1997). A complex adaptive systems model of organization change. Nonlinear Dynamics, Psychology, and Life Sciences, 1(1), 69–97. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022375910940

- Evans, J. C., Yip, H., Chan, K., Armatas, C., & Tse, A. (2020). Blended learning in higher education: Professional development in a Hong Kong university. Higher Education Research & Development, 39(4), 643–656. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1685943

- Ferri, F., Grifoni, P., & Guzzo, T. (2020). Online learning and emergency remote teaching: Opportunities and challenges in emergency situations. Societies, 10(4), 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc10040086

- Gao, X., Guo, F., & Coates, H. (2022). Contributions to the field of student engagement and success. Higher Education Research & Development, 41(1), 62–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2021.2008326

- Gell-Mann, M. (1994). Complex adaptive systems.

- Green, W., Anderson, V., Tait, K., & Tran, L. T. (2020). Precarity, fear and hope: Reflecting and imagining in higher education during a global pandemic. Higher Education Research & Development, 39(7), 1309–1312. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1826029

- Herrmann, K. J. (2013). The impact of cooperative learning on student engagement: Results from an intervention. Active Learning in Higher Education, 14(3), 175–187. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787413498035

- Hodges, C. B., & Fowler, D. J. (2020). The COVID-19 crisis and faculty members in higher education: From emergency remote teaching to better teaching through reflection. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Perspectives in Higher Education, 5(1), 118–122. https://doi.org/10.32674/jimphe.v5i1.2507

- Holland, J. H. (2006). Studying complex adaptive systems. Journal of Systems Science and Complexity, 19(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11424-006-0001-z

- Kahu, E. R. (2013). Framing student engagement in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 38(5), 758–773. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2011.598505

- Kahu, E. R., & Nelson, K. (2018). Student engagement in the educational interface: Understanding the mechanisms of student success. Higher Education Research & Development, 37(1), 58–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2017.1344197

- Kariippanon, K. E., Cliff, D. P., Okely, A. D., & Parrish, A. M. (2020). The ‘why’ and ‘how’ of flexible learning spaces: A complex adaptive systems analysis. Journal of Educational Change, 21(4), 569–593. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-019-09364-0

- Levin, S. A. (1998). Ecosystems and the biosphere as complex adaptive systems. Ecosystems, 1(5), 431–436. https://doi.org/10.1007/s100219900037

- Lorenz, E. N. (1960). Maximum simplification of the dynamic equations. Tellus, 1(12), 243–254. https://doi.org/10.3402/tellusa.v12i3.9406

- MacMahon, S., Leggett, J., & Carroll, A. (2020). Promoting individual and group regulation through social connection: Strategies for remote learning. Information and Learning Science, 121(5/6), 353–363. https://doi.org/10.1108/ILS-04-2020-0101

- Marshall, S., Blackley, S., & Green, W. (2022). 40 years of research and development in higher education: Responding to complexity and ambiguity. Higher Education Research & Development, 41(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2021.2012879

- McGaughey, F., Watermeyer, R., Shankar, K., Suri, V. R., Knight, C., Crick, T., … Chung, R. (2021). ‘This can’t be the new norm’: Academics’ perspectives on the COVID-19 crisis for the Australian university sector. Higher Education Research & Development, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2021.1973384

- Naylor, D., & Nyanjom, J. (2021). Educators’ emotions involved in the transition to online teaching in higher education. Higher Education Research & Development, 40(6), 1236–1250. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1811645

- Raduescu, C., Leonard, J., & Hardy, C. (2016). Course design principles to support the learning of complex information infrastructures. Paper presented at the 27th Australasian Conference on Information Systems (ACIS 2016), Wollongong: Australasian Association for Information Systems (AAIS).

- Reyad, S., Madbouly, A., Chinnasamy, G., Badawi, S., & Hamdan, A. (2020, June). Inclusion of mixed method research in business studies: Opportunity and challenges. In: ECRM 2020 20th European Conference on Research Methodology for Business and Management Studies: ECRM 2020. Academic Conferences and Publishing Ltd, 19(3), 248.

- Schneider, M., & Somers, M. (2006). Organizations as complex adaptive systems: Implications of complexity theory for leadership research. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(4), 351–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2006.04.006

- Stacey, R. (2007). The challenge of human interdependence: Consequences for thinking about the day to day practice of management in organizations. European Business Review, 19(4), 292–302. https://doi.org/10.1108/09555340710760125

- Tai, J. H. M., Bellingham, R., Lang, J., & Dawson, P. (2019). Student perspectives of engagement in learning in contemporary and digital contexts. Higher Education Research & Development, 38(5), 1075–1089. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1598338

- TEQSA. (2020). Foundations for good practice: The student experience of online learning in Australian higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic, November 2020. Retrieved July, 2021, from https://www.teqsa.gov.au/latest-news/publications/foundations-good-practice-student-experience-online-learning-australian

- Tharapos, M., Peszynski, K., Lau, K. H., Heffernan, M., Vesty, G., & Ghalebeigi, A. (2022). Effective teaching, student engagement and student satisfaction during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from business students’ qualitative survey evaluations. Accounting & Finance, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/acfi.13025

- Wang, Y., Han, X., & Yang, J. (2015). Revisiting the blended learning literature: Using a complex adaptive systems framework. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 18(2), 380–393.

- Watermeyer, R., Crick, T., Knight, C., & Goodall, J. (2021). COVID-19 and digital disruption in UK universities: Afflictions and affordances of emergency online migration. Higher Education, 81(3), 623–641. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00561-y

- Willoughby-Knox, B., & Yates, L. (2021). Working toward connectedness: Local and international students’ perspectives on intercultural communication and friendship-forming. Higher Education Research & Development, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2021.1985087