ABSTRACT

Students’ prior knowledge may affect their learning of content in a compulsory Indigenous Studies course. Notably, non-Indigenous pre-service teachers’ prior knowledge may bring conceptions and misconceptions to their formal Indigenous Studies education, potentially influencing their engagement with and/or resistance to concepts affecting their manifestation in their future classroom practices. Indeed, learning, unlearning, and relearning often occur in Indigenous Studies courses. Accordingly, this research aimed to understand what formal and informal knowledge students bring with them to their university studies to improve pedagogy. The survey data were collected from 357 pre-service teachers commencing a compulsory Indigenous Studies university course over four semesters. This analysis revealed two distinct clusters – those who valued their formal schooling knowledge (Formal cluster) and those who valued their personal experience-based knowledge (Informal cluster). Unlike the Formal cluster, the Informal cluster held extreme views of social media as a source of knowledge and were more likely to disagree that their prior knowledge is limited/incomplete. Interestingly, institutional and individual factors such as gender, as well as exposure to enduring discourses, were also important but need further research. We argue that university and school educators need expertise in identifying prior ‘troubling’ knowledge of students and integrating knowledge sources to more skilfully ‘trouble’ and transform student knowledge.

Introduction

The purpose of this research was to gain a deeper understanding of how a pre-service teacher’s prior knowledge may affect their learning in a compulsory university Indigenous Studies course. Research into the importance of students’ prior knowledge in learning has been well-documented for decades in science, mathematics, physics and reading (Shanta & Wells, Citation2022). However, there is minimal literature exploring the prior knowledge pre-service teachers bring with them to an Australian Indigenous Studies course and how this may affect their learning.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples comprise Indigenous Australia, representing 3.8% of the total population, with a larger proportion of school-aged younger people than the non-Indigenous population (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Citation2021), yet comprise only around 2% of the teaching workforce (Australian Council of Deans of Education, Citation2018). Many non-Indigenous university students resist certain types of learning in Indigenous Studies because of the histories of colonisation, and sometimes new knowledge can be unknown and uncomfortable in the context of their existing conceptions or misconceptions (Bodkin-Andrews et al., Citation2022). It may be that students bring misconceptions that have been handed down through an authoritative figure in a formalised sense, such as through primary or secondary education, and these misconceptions need to be unlearned. Alternatively, a non-Indigenous student may have informal or personal experience about the subject area, for example, through being married to an Indigenous person. In both scenarios, understanding a student’s prior knowledge will benefit not only the Indigenous Studies educator in developing more appropriate transformative pedagogies, but is also vital to how the student understands, accepts, or resists course content. This paper explores the troubling misconceptions that educators may need to ‘trouble’ in the classroom.

Literature review

The role of prior knowledge and types of prior knowledge

Research shows that prior knowledge can have a positive effect on student learning, achievement, and success. Defining prior knowledge is challenging, as terms used throughout the literature include ‘current knowledge’ (Bosch et al., Citation2021), ‘expert knowledge’ (Chung et al., Citation2019), ‘professional and personal knowledge’ (Trigwell, Citation2021), ‘non-formal or tacit knowledge’ (Debarliev et al., Citation2022), and ‘background knowledge’ (Teng, Citation2020).

Although some definitions are broad and serve many disciplines, most scholars define prior knowledge as the knowledge, skills, or abilities that students bring to a learning process (Kek & Huijser, Citation2017). Prior knowledge has foundations in both formal and informal ways of knowing, giving individuals the ability to consciously recall common facts, like the difference between a cat and a dog, and unconscious procedural skills learned through repetitive practice such as driving a car (Kek & Huijser, Citation2017).

Formal or explicit knowledge is knowledge asserted by authority figures like teachers and/or academics whose information is heavily derived from experts in a particular discipline (Harrison & Luckett, Citation2019). Further, Cochran-Smith and Lytle (Citation1999) define prior knowledge as ‘general theories and research-based findings on a wide range of foundational and applied topics that together constitute the basic domains of knowledge about teaching’ (p. 254).

Formal knowledge (or formal ways of knowing) has been reviewed as being the most reliable source of knowledge, meaning the learner can formally articulate what is known such as in school-based content where instructed material is learnt (Kek & Huijser, Citation2017). Informal knowledge is harder to articulate, and the learner may have difficulty because it is often based on emotions and/or intuition which may be obtained through experience (Kek & Huijser, Citation2017).

Informal knowledge includes personal experiences, usually gained through social interactions and diverse ways of seeing, hearing, or observing, which are intrinsically and emotionally charged (Kek & Huijser, Citation2017). There is little literature exploring students’ tacit dimensions of knowledge and the multiple ways this is used to construct knowledge in Indigenous Studies. However, Yukich (Citation2021) notes that students learn strongly when emotional content is provided. Alternatively, many scholars have noted that informal knowledge and personal experience play an effective role in the construction of knowledge. For Polanyi (Citation2010, p. 20), tacit knowledge and informal ways of knowing are:

… an indispensable part of all knowledge, the ideal of eliminating all personal elements of knowledge would, in effect, aim at the destruction of all knowledge. The ideal of exact science would turn out to be fundamentally misleading and possibly a source of devastating fallacies … the process of formalizing all knowledge to the exclusion of any tacit knowing is self-defeating.

Australian Indigenous Studies for pre-service teacher training

There is exhaustive literature showing non-Indigenous students’ resistance to Australian Indigenous Studies course material and their challenging of the educator (e.g., Bodkin-Andrews et al., Citation2022; Nakata et al., Citation2012). Retention of prior knowledge, even when students are faced with alternative conceptions, is a type of resistance that is found extensively throughout the Indigenous Studies literature (Harrison & Luckett, Citation2019).

Racism remains a topic of national significance as it is still very much a part of Australian society in the twenty-first century (Bodkin-Andrews et al., Citation2022). To counteract racism, pre-service teachers are required to undertake Australian Indigenous Studies courses in order to teach in Australian schools, as the national curriculum requires Indigenous Australian perspectives and knowledge ‘cross-cutting’ traditional disciplines including geography, history, biology, and maths (Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership, Citation2017). External accreditation and professional teaching standards were developed for pre-service teachers to assist them to develop strategies for teaching Indigenous students and to understand and respect Indigenous peoples and their diverse cultures, including through reconciliation.

Effective Indigenous Studies pedagogies need to begin with engaging learners in an activity to activate their prior knowledge, informing students that upcoming information may conflict with what they already know, and recognising that some of their misconceptions may need to be ‘unlearned’ (Taylor, Citation2019). For example, a common misconception held by some non-Indigenous people is that Indigenous people receive ‘more’ rights, special treatment, and are more likely to drink alcohol (Pedersen et al., Citation2011). Most non-Indigenous students in the study undertaken by Pedersen and colleagues (Citation2011) had little personal exposure to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and cultures. Furthermore, they were more likely to hold deficit constructs around academic learning or to see ‘other’ students who are dissimilar from them as somewhat inadequate.

Understanding how students construct new information from their prior knowledge, both through their formal education and informal personal experience, allows educators to determine the extent and type of ‘unlearning’ needed before introducing new and challenging information, which may be particularly important in order to unlearn racism (Taylor, Citation2019). To unlearn misconceptions, the individual needs to interrogate their own beliefs and values and to understand how they came to construct certain knowledge (Taylor, Citation2019). A learner constructs knowledge based on their social foundations including power and privilege, which are also important for educators to understand because there may be a need to counter misconceptions in order for students to accept the content (Yukich, Citation2021). Unlearning pre-service student teachers’ misconceptions may therefore require a reflective dialogue that focuses on ‘understanding the frames of references from which ourselves and others speak, and how these frames of reference shape what we can hear and understand’ (McDowall, Citation2018, p. 7).

Methods

This research design is largely based on Crotty’s (Citation2020, p. 8) delineation of epistemology, theoretical perspective, methodology and methods. In using this methodology, the researcher’s values, beliefs, and perspectives were acknowledged as being socially constructed, which allowed the researcher to not only collect and analyse the data but reshape the data throughout the process (Crotty, Citation2020).

Also of benefit to this research is Foucault’s (Citation1972) paradigm of the construction of dominant discourses and how these are implemented within the schooling curriculum, social media and elsewhere, and how these are then seen by students as normal, which could explain why new content delivered in Indigenous Studies courses may be resisted because discursive practices, as developed by Foucault (Citation1972), do not correspond to what students already know and accept.

The method used in this research was a single survey questionnaire comprising questions that required quantitative and qualitative data. The quantitative section of the questionnaire aligns with Schommer-Aikins and Easter's (Citation2006) research and the pencil Likert instrument, which has been found to be effective in measuring students’ prior knowledge. The questions asked respondents for demographic information including gender (male/female/other), age (<24/>25), domestic or international student status, the year they left school and whether they had returned to study after being in the workforce. Students were asked to gauge their prior knowledge on a Likert scale of 1–5 (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Three questions were used to assess prior knowledge. Students were asked if their knowledge of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people was a) learnt at school or other educational institution; b) derived from scientific reasoning and evidence; c) based on personal experience and/or d) based on social media (e.g., Facebook). Respondents were also asked if they felt that the knowledge they currently held was limited and/or incomplete, which reflected knowledge sources and behaviours like their use of social media.

The qualitative section of the questionnaire consisted of questions asking students about their learnt concepts, such as what they remembered learning at school or other educational institutions regarding Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures/peoples/communities, how Indigenous people were portrayed throughout their schooling/educational curriculum, an example of good or bad social media that may have caught their attention over the last six months, and an example of any other informal knowledge they may have learnt about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (e.g., through friends, family, sport). Qualitative analyses were undertaken in the form of manual textual analysis by the first author, followed by all authors triangulating the final interpretation. The coded answers were entered into SPSS for analysis.

Participants were drawn from all students attending the University of the Sunshine Coast and specifically enrolled in the first-year course Introduction to Indigenous Australia over four semesters from Semester 2, 2018 to Semester 1, 2020 (inclusive). The total number of enrolled students was 800, with 45% (n = 357) completing the survey. The sample was disproportionately female (69%) and aged 18–24 years (77%) with a further 12% (n = 43) in the 25–34 years age bracket. Except for six students, all were domestic enrolments, and most students identified as non-Indigenous. This regional university attracts small cohorts of international students who rarely enrol in this Indigenous Studies course. The six international student respondents were too small a number to make a meaningful impact on the results. Indigenous students were enrolled in this course. However, the number of Indigenous respondents was unknown because these students chose not to identify on the survey. This research is written from an Indigenous Standpoint where Indigenous students’ prior knowledge was not analysed for dominance and/or power. Lastly, age cohorts were then broken into those who had recently left school (<24 years of age) and those who had left school later (>25 years of age) to counteract any recent curriculum changes based on changing social values.

Results

‘Bundling’ sources of prior knowledge

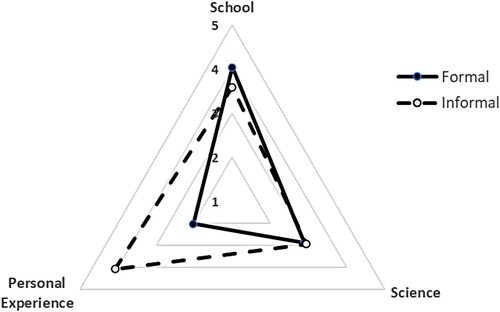

The quantitative data were examined to understand the sources of prior knowledge, their interdependencies, and to profile the respondents who comprised the final knowledge source clusters. In the survey, respondents were asked to evaluate the extent to which their prior knowledge was derived from school through scientific reasoning or personal experience. The first two are formal knowledge types, and the last is an informal knowledge type. presents the means for each source (reported on a 5-point Likert scale).

Table 1. Prior Knowledge Sources (All Respondents).

The School (Formal) (M = 3.74) knowledge source mean was significantly higher than the scale midpoint, while the Science (Formal) (M = 2.88) knowledge source mean was significantly lower than the scale midpoint, indicating that respondents tended to agree with School (Formal) as a source of knowledge and to disagree with Science (Formal) as a source of knowledge. Personal Experience (Informal) was not significantly different from the scale midpoint (t(356) = 1.19, p = .24). All means were significantly different from each other. Specifically, the School (Formal) knowledge source mean was significantly higher (in agreement) than the Science (Formal) knowledge source mean response (t(353) = 13.24, p < .001), and the Personal Experience (Informal) knowledge source mean response (t(354) = 7.20, p < .001). Also, the Science (Formal) knowledge source mean was smaller than the Personal Experience (Informal) knowledge source mean (t(355) = 2.60, p = .010).

Next, we examined to what extent the knowledge source scale items were interrelated or ‘bundled’. We employed the SPSS Hierarchical Cluster using standard squared Euclidian distance and between-groups linkage methods to examine the extent to which the cases formed coherent clusters. Examining the number of cases falling into a range of cluster solutions, the results indicated that the initial three groups comprised two large groups and one much smaller group of 11 respondents. Hence, a two-cluster solution was chosen. To assess cluster validity, the mean item scores for measures in were tested in a mixed ANOVA (analysis of variance) for differences, showing a significant interaction between the two-group cluster and three items (F(1.88, 639.92) = 254.25, p < .001; Greenhouse-Geisser adjusted) with the profiles of the means for each of the two groups (or ‘bundles’) presented in . Because the primary difference in the two clusters was found in comparing School (Formal) source of knowledge and Personal Experience (Informal) means, we named the two clusters in accordingly. Forthwith, we use the terms Formal to represent the school/science cluster and Informal to represent the personal experience cluster.

shows the relative difference in knowledge source means for the Formal versus Informal clusters. The three axes represent the means of the knowledge sources for School (Formal), Science (Formal) and Personal Experience (Informal). The Informal cluster overlaps with the Formal cluster on the Science (Formal) knowledge source, and to a lesser degree, the School (Formal) knowledge source is primarily distinguished by a higher mean on the Personal Experience (Informal) knowledge source (see , bottom left corner).

Keeping in mind the results from the mixed ANOVA, showing that all knowledge source items form two clusters, ultimately what shows is that the difference between the clusters is to a stronger degree about the central role of Personal Experience (Informal) knowledge, and to a lesser degree related to the marginal importance of School (Formal) as a discriminating knowledge source.

We then asked, are the ‘bundled’ clusters of Formal and Informal knowledge sources different in terms of the demographic and behavioural characteristics of respondents? The results are provided in .

Table 2. Profiles of Formal and Informal Clusters.

shows that all factors, with the exception of school level, were significant in differentiating the two knowledge source clusters. The Formal cluster tended to be more likely female (55%), younger (55%), to have more recently finished (secondary) school (55%), and respondents were less likely to be returning to study (33%). Alternatively, the Informal cluster was more likely to be male (59%), older (71%), have less recently completed school (73%), and respondents were returning to study (67%). Notably, the Informal cluster both agreed (26% vs 19%) and disagreed (58% vs 49%) that their prior knowledge was influenced by social media.

The interplay between Formal and Informal clusters on learning self-efficacy

The influence of the Formal and Informal sources of knowledge on respondents’ perception that their knowledge was complete/limited is presented in .

Table 3. The Influence of Knowledge Source Clusters on Perceived Self-efficacy.

shows that while both clusters tended to agree that their knowledge was limited/incomplete, the Formal cluster had a higher level of agreement (86%, n = 148) than the Informal cluster (66%, n = 112). Conversely, the Informal cluster was more likely to disagree that their knowledge was limited/incomplete (20%, n = 34) compared to the Formal cluster (7%, n = 12). That is, the Informal cluster was approximately three times more likely to disagree that their prior knowledge about Indigenous Australians was limited/incomplete compared to the Formal cluster.

Textual analyses of qualitative data about learnt (mis-)conceptions

Respondents were asked what they remembered learning at school about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people/communities and to give examples of their personal experiences (e.g., through friends, family, sport etc.). Additionally, respondents were asked to describe social media they had seen in the last six months regarding Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples/communities.

Learnt (mis-)conceptions from Formal prior knowledge sources

The majority of respondents noted how in school (Formal knowledge source) they were exposed to repetitive renditions of the narrative feature film Rabbit Proof Fence (Noyce, Citation2002), which shows the effects of Australian Government assimilation policies of The Stolen Generations, where children were removed from their families into missions and where they were trained for domestic service and labour for settlers. Primary school students noted that ‘we watched the Rabbit Proof Fence’ (<24, female), but it ‘wasn’t really elaborated on’ (<24, female, Formal) despite it causing division as ‘they [Indigenous Australians] were so separate to us’ (<24, female, Formal). Respondents’ memories of secondary school showed a similar over-reliance on particular curriculum materials, including ‘we watched Rabbit Proof Fence twice’ (<24yr, male, Formal).

Other primary school learning was about Indigenous culture. Respondents' recollections included that they ‘learnt about their culture, e.g., what they are and ways of living’ (<24, female, Formal). Dreaming stories and art were also mentioned, with one student highlighting that ‘Aboriginal culture is mostly the dreaming and oral stories’ (>25, male, Formal). Traditional learning of art was highlighted, with one student stating, ‘we did art in primary, that is all we were taught!’ (>25, female, Formal). Similarly, traditional food and tools (hunting and gathering) featured strongly. A key conception from formal prior knowledge sources was ‘understanding that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are different’ (<24, male, Formal).

The impacts of colonisation were recalled by some respondents when recounting their learning from secondary schooling – ‘I remember learning about the crimes Europeans committed against Aboriginal people’ (>25, male, Formal) and the ‘white policy act, land rights’ (>25, male, Formal). The extermination of the Tasmanian Aboriginal people was also recalled from secondary school learning and, similarly, that ‘Captain Cook found Australia which was classed as uninhabited’ (>25, female, Formal). Some remembered contemporary conceptions from their secondary education, including the Mabo legal case, which altered the foundation of land law in Australia by overturning the doctrine of terra nullius used by the British to take possession of Australia (Secher, Citation2007). The Sorry Speech was also recounted from secondary school, being the Australian Government’s apology to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, particularly the Stolen Generations, whose lives have been impacted by past policies of removal and assimilation (Tippo et al., Citation2008). One respondent remembered ‘[Prime Minister] John Howard refusing the Sorry Speech, then [the succeeding Prime Minister] Kevin Rudd delivering the apology’ (<24, male, Formal).

Learnt (mis-)conceptions from Informal prior knowledge sources

Respondents who preferred Informal prior knowledge sources based on personal experiences also recalled overexposure to Rabbit Proof Fence and the myth of Tasmanian Aboriginal absence – ‘I was taught that there were no real Tasmanian Aboriginal peoples left because they had all been killed. I was left with the impression that the Aboriginal culture was fearsome and almost barbaric’ (>25, female, Informal). Some also remembered learning about Indigenous culture and art – ‘During primary school, there was a focus on the artistic side of Aboriginal people, i.e., dot painting’ (<24, female, Informal). Others recalled cultural stereotypes – ‘they were nomadic people, isolated communities, hunter/gatherers’ (>25, male, Informal).

Different experiences were noted between the Informal and Formal prior knowledge clusters. One misconception mirrored deficit discourses as illustrated by the following quote: ‘Low socio-economic status, health is poor, and a struggle with addiction and alcoholism – Separate to our community, as in there was a focus on regional and isolated Indigenous communities’ (<24, female, Formal). Another respondent wrote: ‘The advantages they [Indigenous Australians] receive/opportunities in part that I did not get’ (<24, female, Formal). Some respondents stated, ‘I really don’t remember learning much at all about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people whilst at school. What I know has come from Aboriginal friends’ (<24, female, Informal). Other respondents portrayed a reflective stance, such as ‘a year 11 elective modern history class … was culturally insensitive’ (<24, female, Informal) and ‘I remember learning about [Indigenous] culture through workshops and guest speakers and camps etc. In class learning was very Eurocentric’ (<24, male, Informal).

Social media and Formal and Informal prior knowledge sources

Many students from both the Formal and Informal clusters recalled social media posts about the Change the Date (Pearson & O’Neill, Citation2009) protests to move Australia Day away from January 26th (the date of Federation). One respondent called it the ‘Australia Day disagreement’ (<24, female, Formal), and another highlighted the ‘debate over renaming Australia Day to Invasion Day’ (>25, male, Informal). One example from an older female, however, suggested changing the date would cause a national divide – ‘calling to change Australia Day to Invasion Day. I was upset by this as I feel it will break Australia apart’ (>25, female, Informal).

Some respondents, mainly the younger males, noted racist comments in their social media sporting threads. For example, one respondent wrote, ‘I recently watched the Adam Goodes documentary and realised just how real racism still is’ (<24, male, Formal) and that at ‘the State of Origin [rugby league football match], Aboriginal men won’t sing [the] Australian national anthem, [which drew] racist comments from people [on social media]’ (<24, male, Formal).

However, some of the older female respondents focused on social injustices, referring to social media posts about ‘police brutality and no trust or connections within communities’ (>25, female, Formal) and ‘the treatment of people within the prison/justice system and how their human rights are violated’ (>25, female, Informal). Others observed a lack of empathy from mainstream society towards ‘The two Indigenous young boys who drowned in Townsville during the flood. Many of the [social media] comments on the piece were very racist/negative, with no sympathy, e.g., 2 less on the dole’ (<24, female, Formal).

Many respondents remembered negative social media posts about crime – ‘Crimes on the news performed by Aboriginal people’ (<24, female, Formal) and ‘Violence, alcohol abuse, dole bludging’ (<24, female, Formal). Further, some remember seeing social media posts referring to Indigenous Australians as ‘scamming the system’ (<24, female, Informal) and ‘[getting] free Centrelink and special treatment’ (<24, male, Informal). Some students recounted a particular locale due to their personal experience of living or growing up there. For example, ‘The crime. My hometown is on the news quite often. Usually, it is [Indigenous] primary school aged children [who are offenders]’ (<24, male, Informal). Also, ‘In Townville, the media portrayed Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people as people that bought alcohol and drunk copious amounts then wreaked havoc in town’ (<24, female, Informal).

Discussion

Cultural baggage – why troubled knowledge?

A prevailing narrative is traceable through respondents’ layers of qualitative data in both prior knowledge clusters. Primary school knowledge mostly introduced respondents to (positively) stereotypical representations of Indigenous Australians (recalling art, Dreaming stories, food, tools etc.). Any knowledge implicating stereotypes in primary school was that of the Stolen Generations (via the narrative feature film Rabbit Proof Fence) and the Prime Minister’s Sorry Speech apologising to Indigenous Australians, which may have been formative in young respondents’ experiences. Such stereotypical views are commonly held and can cause resistance to the more troubling knowledge of the impacts of colonisation on Indigenous disadvantage and suffering (Bodkin-Andrews et al., Citation2022). Furthering these conceptions (and misconceptions) is problematic in that the next generation of students will continue to learn the same material from their teachers (Yukich, Citation2021).

Secondary schooling concepts did include impacts of colonisation and land claims, including the Mabo case, alongside social issues including the Stolen Generations and the Sorry Speech. There may be a progression from ‘easy to accept’ concepts in primary school to more challenging concepts in secondary school that deepen student understandings of Australian history, despite the retention of some misconceptions around the absence of Aboriginal people from certain places.

The ‘unsure’ sub-group in the Formal cluster, however, can be influenced by adamant students in tutorials, supporting the need for ‘unsure’ students to examine their own positionalities in relation to the dominant viewpoint of more vocal peers (Carter & Hollinsworth, Citation2017). Hollinsworth (Citation2016), in recognition of the influence of peers, recommends a deliberative pedagogy that troubles and discomforts learners from the historically dominant society in their awareness of themselves and their relationships with those who are racially oppressed.

While those preferring Informal knowledge sources held similar misconceptions based on the Formal cluster with regard to curriculum over-use, stereotypes and myths, they also noted cultural insensitivity and Eurocentrism at school or no formal instruction at all. Nevertheless, the prevalence of references to alcoholism and addictions could also reflect the prevailing deficit discourse perpetuated by their school educators that may continue to subjugate Indigenous peoples (Pedersen et al., Citation2011).

Two knowledge systems

Our initial descriptive analyses (see ) might imply that students had a monotonic knowledge source built on a cumulation of more specific indicators. However, our subsequent ‘bundling’ results revealed that students drew their knowledge from either Formal (school or science) or Informal (personal experience) sources. The Formal and Informal clusters represent different and diametrically opposed systems in that their indicators tend to be negatively correlated and not summative or additive in nature.

Understanding the constellation of the three indicators – School, Science and Personal Experience – in forming the two clusters – Formal and Informal – is important as they represent potentially wider social and interactional processes from which students’ conceptions (and misconceptions) are set in motion, suggesting all educators need to integrate both Formal and Informal knowledges that are mutually exclusive (Halverson & Rosenfeld Halverson, Citation2019), which is a complex task.

The embedded nature and reproduction of ways of seeing and knowing

Encountering and negotiating troubling knowledge is the corollary of critical thinking, and this research sought to understand the profiles of students in each of the two knowledge clusters and how each cluster perceived their self-efficacy in learning in the course. Again, the results underscored that the two clusters varied significantly, with the Formal cluster more likely to be younger, female, and having recently completed secondary school, with the Informal cluster typically being older, male, and having completed secondary school some time ago. Female respondents were not any more likely to be in a younger or older age category, nor have more or less recently finished school than their male counterparts, so these factors should be treated strictly independently. As such, they represent a combination of socially constructed, cohort-specific, and context-dependent factors important in orienting individuals to either Formal or Informal knowledge sources.

While an older age and more time since finishing school would be expected to play out into Informal dominant knowledge sources, it is less obvious how respondents’ gender works in knowledge source clusters. The performative nature of ‘doing gender’ (Wehrle, Citation2019) may serve to situate female and male roles, leading to Formal or Informal knowledge clusters. While our analyses cannot provide a full account of how respondents actively construct the essentially gendered nature of their knowledge sources, they point both quantitatively and qualitatively to the centrality of gender as a key factor.

A key finding from our research is that the Formal cluster had a higher sense of agreeing that their knowledge was limited/incomplete at the start of a university semester, while the Informal cluster respondents tended to disagree that their knowledge was limited/incomplete. Again, whilst the Informal cluster held some conceptions around Eurocentrism and cultural insensitivity, their misconceptions about benefits and privileges received by Indigenous Australians need guidance and reflection, as problematic informal knowledge based on experience can block more formal types/facts of learning, particularly when students perceive their own (heightened) self-efficacy in such knowledge (Harrison & Luckett, Citation2019).

These demographic findings are further evidence of the need to centre institutional, culturally embedded and individually constituted notions of everyday life, as these are also crucial to understanding the production and reproduction of systematic differences in individuals that feed into knowledge source differences. Misconceptions can be either challenged in local interactional contexts or uprooted from the bedrock of historically enduring discourses, including deficit discourses, meaning all educators need the expertise to counteract some misconceptions. In addition, the overuse of some curriculum resources may detract from individual understandings of important learning instances due to student boredom without further contextualisation (Hook, Citation2012).

Do different knowledge systems matter?

The lower self-efficacy in the Formal cluster compared with the Informal cluster may mean that school educators in formal learning settings have introduced some recent insights from current issues or knowledge, or it could mean that the role of informal personal experience functions to provide biases, both positive and negative. This result suggests that in practice it may be more difficult for students with prior personal experience as a source of informal knowledge to ‘unlearn’ misconceptions, with such students potentially being more active in resisting course content.

Regarding social media, the Informal cluster was both (i.e., simultaneously) more likely to disagree and more likely to agree with social media as a knowledge source compared with the Formal cluster, suggesting all educators may need to trouble social media examples in the classroom. For example, students refer to youth sniffing petrol on social media and the educator would counteract such representations with facts such as lead petrol not being available in communities for many years.

These results carry two lessons. Firstly, those with Informal prior knowledge may seek out affirming or confirming support on social media representing a more extreme position (either agree or disagree) about social media than those who were unsure, and secondly, they are perhaps more ambivalent, simultaneously discounting and rejecting social media information about Indigenous Australians that challenges their prior conceptions. Social media representations of Indigenous Australians are proliferating with little regulation or mediation (Herborn, Citation2013), presenting a danger for those who draw primarily from personal experience in, as our results show, galvanising their sense of efficacy in their existing knowledge. Further research between informal personal experience as a prior knowledge source and confirmation-seeking/discounting behaviour through social media is needed.

A different mechanism is suggested for the Formal cluster, which appears to be almost two times more likely to be ‘unsure’ about social media than the Informal cluster. Arguably, teaching that draws out reflection, emphasising diverse perspectives, could systematically evaluate the bases of knowledge (Formal or Informal cluster). With this in mind, the high levels of being ‘unsure’ in the Formal cluster makes sense. These students may require little or no unlearning; nevertheless, they still require effective pedagogy and curriculum to engage them rather than repetitive curriculum resources.

In the spaces created by discomforting and troubling confrontations, with support, learners can both unlearn and relearn knowledge, which can be liberating and transformative. It is important to understand that two systems of knowledge are concurrently in operation, and they do not overlap. The socio-demographic characterisation of each of the two dominant clusters (Formal and Informal) are different and is entrenched and embedded in a wider social context within which individuals both establish their identities (i.e., agency) but are also normatively constrained (i.e., structure, culture, and dominant discourses).

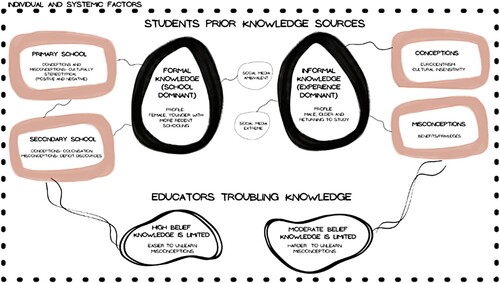

Drawing all these elements together, provides a diagrammatic summary of the key profiles of each system to visually situate elements relevant to the individual learner in compulsory Indigenous Studies courses, suspended within their social contexts and knowledge systems, but also relevant to those educators and researchers grappling with troubling knowledge. For knowledge that is ‘troubling’ to be overturned by educators, understanding students’ prior knowledge sources will be required in order to skilfully trouble that knowledge, and negotiate a path that leads to improved conceptions and social outcomes.

Conclusion

This research aimed to understand the prior knowledge sources of pre-service student teachers at the start of a university Indigenous Studies course and found explanations provided by different group demographics. The research showed that students tended to draw their prior knowledge from either Formal (School and Science) learning or Informal (Personal Experience) learning.

Those with Formal prior knowledge tended to be younger females who had recently left school and were unsure about social media being a source of information. Primary school conceptions and misconceptions were usually characterised by culturally stereotypical (positive and negative) information, and secondary school conceptions included colonisation and its impacts and some misconceptions, and the prevalence of deficit discourses. This Informal cluster also agreed that their current knowledge was limited.

Those in the Informal prior knowledge cluster were predominantly male, older than 25, more likely to be returning to study, and they took extreme positions on agreeing/disagreeing with social media as a source of prior knowledge about Indigenous Australians. This cluster was more likely to express concepts of Eurocentrism and cultural insensitivity, yet they held misconceptions about special benefits and privileges but also disagreed that their knowledge was limited.

Understanding the prior knowledge that a student brings to the classroom, including an awareness of imposed colonial narratives, remains crucial for determining the pedagogical effects of unlearning. Additionally, the process of truth-telling and reconciliation will benefit from a critical review of historical and political relationships and the institutional racism that still exists. In order to skilfully confront students’ ‘troubling’ information and navigate a path that leads to improved conceptions and socially just outcomes, educators must have a thorough understanding of students’ past knowledge sources.

Ethics number

S181194

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Professor David Hollinsworth and the students who participated in this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2021, June). 3238.0.55.001. Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-peoples/estimates-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-australians/latest-release

- Australian Council of Deans of Education. (2018, March). ACDE analysis of 2016 census statistics of Aboriginal Torres Strait Islander teachers and students. https://www.acde.edu.au/acde-analysis-of-2016-census-statistics-of-aboriginal-torres-strait-islander-teachers-and-students/

- Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership Limited. (2017). National professional standards for teachers. https://www.aitsl.edu.au/teach/standards

- Bodkin-Andrews, G., Page, S., & Trudgett, M. (2022). Shaming the silences: Indigenous graduate attributes and the privileging of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voices. Critical Studies in Education, 63(1), 96–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2018.1553795

- Boelens, R., De Wever, B., & Voet, M. (2017). Four key challenges to the design of blended learning: A systematic literature review. Educational Research Review, 22, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2017.06.001

- Bosch, E., Seifried, E., & Spinath, B. (2021). What successful students do: Evidence-based learning activities matter for students’ performance in higher education beyond prior knowledge, motivation, and prior achievement. Learning and Individual Differences, 91, 102056–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2021.102056

- Carter, J., & Hollinsworth, D. (2017). Teaching Indigenous geography in a neo-colonial world. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 41(2), 182–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2017.1290591

- Chung, C., Hwang, G., & Lai, C. (2019). A review of experimental mobile learning research in 2010–2016 based on the activity theory framework. Computers & Education, 129, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.10.010

- Cochran-Smith, M., & Lytle, S. (1999). Chapter 8: Relationships of knowledge and practice: Teacher learning in communities. Review of Research in Education, 24(1), 249–305. https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732X024001249

- Crotty, M. (2020). The foundations of social research: Meaning and perspective in the research process. Allen and Unwin.

- Debarliev, S., Janeska-Iliev, A., Stripeikis, O., & Zupan, B. (2022). What can education bring to entrepreneurship? Formal versus non-formal education. Journal of Small Business Management, 60(1), 219–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2019.1700691

- Foucault, M. (1972). The archaeology of knowledge and the discourse. Pantheon.

- Halverson, R., & Rosenfeld Halverson, E. (2019). Education as design for learning. Wisconsin Centre for Education Research. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED598669

- Harrison, N., & Luckett, K. (2019). Experts, knowledge and criticality in the age of ‘alternative facts’: Re-examining the contribution of higher education. Teaching in Higher Education, 24(3), 259–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2019.1578577

- Herborn, D. (2013). Racial vilification and social media. Indigenous Law Bulletin, 8(4), 16–19. http://www.ilc.unsw.edu.au/sites/ilc.unsw.edu.au/files/articles/ILB%208

- Hollinsworth, D. (2016). Unsettling Australian settler supremacy: Combating resistance in university Aboriginal studies. Race Ethnicity and Education, 19(2), 412–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2014.911166

- Hook, G. (2012). Towards a decolonising pedagogy: Understanding Australian Indigenous Studies through critical whiteness theory and film pedagogy. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 41(2), 110–119. https://doi.org/10.1017/jie.2012.27

- Kek, M., & Huijser, H. (2017). Problem-based learning into the future. Springer.

- McDowall, A. (2018). (Not)knowing: Walking the terrain of Indigenous education with preservice teachers. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 100–108. https://doi.org/10.1017/jie.2017.10

- Nakata, M., Nakata, V., Keech, S., & Bolt, R. (2012). Decolonial goals and pedagogies for Indigenous studies. Decolonization: Indignity, Education & Society, 1(1), 120–140.

- Noyce, P. (2002). Rabbit Proof Fence, Showtime Australia. https://www.sbs.com.au/movies/video/84673091819/Rabbit-Proof-Fence

- Pearson, W., & O’Neill, G. (2009). Australia Day: A day for all Australians? In D. McCrone, & G. McPherson (Eds.), National days (pp. 73–88). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Pedersen, A., Walker, I., Paradies, Y., & Guerin, B. (2011). How to cook rice: A review of ingredients for teaching anti-prejudice. Australian Psychologist, 46(1), 55–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-9544.2010.00015.x

- Polanyi, M. (2010). The tacit dimension. University of Chicago Press.

- Schommer-Aikins, M., & Easter, M. (2006). Ways of knowing and epistemological beliefs: Combined effect on academic performance. Educational Psychology, 26(3), 411–423. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410500341304

- Secher, U. (2007). The high court and recognition of native title: Distinguishing between the doctrines of terra nullius and desert and uncultivated. UW Sydney, 11, 1. http://classic.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/UWSLawRw/2007/1.html

- Shanta, S., & Wells, J. (2022). T/E design based learning: Assessing student critical thinking and problem solving abilities. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 32(1), 267–285. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10798-020-09608-8

- Taylor, L. (2019). What does it mean to story our shared historical present? The difficult work of receiving residential school survivor testimony as bequest. In K. Llewellyn, & N. Ng-A-Fook (Eds.), Oral history, education, and justice: Possibilities and limitations for redress and reconciliation (pp. 132–146). Routledge.

- Teng, F. (2020). Tertiary-Level students’ English writing performance and metacognitive awareness: A group metacognitive support perspective. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 64(4), 551–568. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2019.1595712

- Tippo, L., Geia, L., Lever, J., & Hastie, M. (2008). ‘Sorry matters’— through indigenous eyes. TEACH Journal of Christian Education, 2(1), 46-47. https://research.avondale.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1162&context=teach, https://doi.org/10.55254/1835-1492.1162

- Trigwell, K. (2021). Scholarship of teaching and learning. In L. Hunt, & D. Chalmers (Eds.), University teaching in focus (pp. 286–303). Routledge.

- Wehrle, M. (2019). Doing gender differently?: The embodiment of gender norms as between permanence and transformation. In T. Bedorf, & S. Herrmann (Eds.), Political phenomenology (pp. 300–324). Routledge.

- Yukich, R. (2021). Feeling responsible towards Aotearoa New Zealand’s past: Emotion at work in the stance of five pākehā history teachers. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 56(2), 181–199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40841-021-00218-z