ABSTRACT

University professors’ collegiality has received far more attention in higher education research than collegiality among higher education students. Hence, this lack of research concerning higher education students’ collegiality represents a research gap that this study aims to fill. The present study aimed at examining the contribution of personal characteristics and goal orientations to collegiality among higher education students. A total of 196 undergraduate students participated in the study. Path analysis revealed that different personality characteristics (gender, age, type of study program, years in college, and academic self-concept) and traits (Big Five and altruism) are related to goal orientations as well as positive and negative collegiality. Results are discussed regarding theoretical assumptions on pro-social development, measurement problems, and practical applications in higher education courses or trainings.

Collegiality represents a widely accepted value within institutions of higher education (e.g., Kligyte & Barrie, Citation2014). Basically, it encompasses actions within cooperative environments reflecting prosocial values as well as individual and group-related rights and responsibilities (Haviland et al., Citation2017). Moreover, collegiality is an important factor in higher education institutional culture and leadership, faculty development and research productivity, especially among university professors (e.g., McGrath et al., Citation2019). Although undergraduate and graduate students are part of higher education institutions, have research motivations and disciplinary identities as well as significantly contribute to research activities, empirical research on collegiality among these groups of students is still rare (e.g., Davis & Wagner, Citation2019). For example, Trigwell (Citation2005) found that students describe collegiality as encompassing a sense of allegiance for deeper approaches to learning. Of course, there is research on higher education students’ soft or social skills and how they are connected to collegiality, such as research on starting, leading, maintaining, and ending of social relationships (e.g., Moeller & Seehuus, Citation2019). For example, Chamorro-Premuzic et al. (Citation2010) found that collegiality-related soft skills positively affect academic performance. Panteli et al. (Citation2021) discovered that during the COVID-19 pandemic social skills of college students were related to their perceived stress. However, these approaches on social skills are highly generalized without being contextualized in academic environments and especially in specific research-related experiences.

Traditional theories on collegiality focus on concepts like altruism, conscientiousness, sportsmanship, courtesy, or civic virtue as well as on mutual support/trust, equity/politics, and shirking behavior (Johnston et al., Citation2010; Macfarlane, Citation2016; Miles et al., Citation2015). Based on such models, research on higher education students’ collegiality needs to consider multiple conceptual and measurement-based options.

First, higher education students’ collegial behavior is related to specific domains of researcher development and behaviors. These are usually connected to social activities such as doing research, supporting professional and career development, managing research projects, and realizing professional conduct, engagement and impact together with sophisticated communication and dissemination techniques (Bray & Boon, Citation2011).

Second, collegial behavior encompasses positive and negative dimensions at the same time. Establishing an entrepreneurial university within a climate of hypercompetition challenges mistakes or misconduct as well as negative collegial behavior that can be discriminating, marginalizing, or damaging to professors and to students (e.g., Wankel & Wankel, Citation2012). Based on these shortcomings in research, Astleitner (Citation2021) has developed a research-based model that covers positive and negative research-related behaviors of collegiality as well as context dimensions among researchers. This theoretical model of collegiality includes aspects of (positive or negative) relationship quality, (low or high) degree of involvement with others, and attributional contexts (related to intention, evidence, and transparency of activities).

Third, since there is little research on higher education students’ collegiality, it is necessary to relate it to other relevant variables in higher education settings in order to increase validity. We expect that personal characteristics (gender, age, type of study program, years in college, or academic self-concept), which are traditionally closely related to academic performance, are also related to collegiality, because many achievements in learning and research are based on cooperation and team work. For example, Afolabi (Citation2014) identified relationships between age, gender, self-esteem, and collegiality-related prosocial behavior as well as social adjustment. Deniz et al. (Citation2005) discovered that variables that are closely related to collegiality like emotional expressivity, emotional sensitivity and social control of female college students were found to be higher than those of male students. A study from Olsen and Gebremariam (Citation2022) found that students majoring in humanities have higher scores on socially relevant empathy than their peers majoring in other disciplines. Rinn et al. (Citation2014) identified small but significant negative relationships between academic self-concept and collegiality-related academic dishonesty. Therefore, we assume that collegiality is related to personality traits like the Big Five personality traits. Moreover, we also include altruism, since it is central for positive behavior towards others. Concerning personality traits, Rhee et al. (Citation2013) identified significant correlations between the Big Five and undergraduates’ individual collegiality-related performance, like contributing useful ideas that help the group succeed. Also, Agbaria and Mokh (Citation2022) found relationships between all Big Five personality traits and social support experiences within a sample of college students. Branas-Garza et al. (Citation2010) observed that undergraduates who are better socially integrated are more altruistic. Rubin and Wright (Citation2017) discovered negative correlations between age and social integration whereas Tseng et al. (Citation2019) did not find any differences on social skills between graduate in comparison to undergraduate students. In addition, Park and Shin (Citation2017) discovered that higher education students’ prosocial behavior can be enhanced by prosocial behavior from peers. Also, goal orientations play a role in social settings. They are about motives of improving abilities, demonstrating abilities, or hiding lack of ability (e.g., Hsieh et al., Citation2007). These goal orientations might be academic and related to learning and motivation as well as social-emotional factors, like courtesy. For example, Ferrari et al. (Citation2009) found out that highly engaged students in mission-driven social campus activities show more noticeable goal orientations. Also, Mansson and Myers (Citation2012) identified courtesy as an important part of maintenance behaviors related to mentoring relationships of higher education students and their advisors.

The current study

Based on these findings, our study aims at exploring interrelations among personality characteristics (gender, age, years in college, type of study program), personality traits (Big Five traits, academic self-concept, altruism), academic and social goal orientations (mastery, approach, avoidance motivation as well as courtesy), and (positive and negative research-based) higher education students’ collegial behavior. We focus on behavioral aspects of collegiality that allow to conceptualize collegiality as a skill composed of a larger set of behaviors. Considering the research studies mentioned above and a prosocial development model from Eisenberg et al. (Citation2015), our goal was to test three general hypotheses: (1) Personality characteristics will relate to collegial behavior; (2) Personality traits will correlate with collegial behavior; and (3) Academic and social goal orientations will mediate the influence of personality characteristics and personality traits on collegial behavior. Additionally, our study aims at developing and testing an instrument on higher education students’ collegial behavior.

Method

Participants

In sum, 196 undergraduate students (32.1% male and 67.9% female) from different majors at the Paris-Lodron University of Salzburg participated in the study. About 84.7% of the participants were doing the teacher training program, and 15.3% did other college majors. The teacher training program at that university is strongly dominated by professional development in different content areas of teaching such as biology, mathematics, or art education. It is a university training program with a strong scientific orientation which is what makes it different from the usual more practice-oriented undergraduate programs. Participants' average age was 23 years (SD = .47) and they filled in an online questionnaire. Participants were recruited in courses of the first and second author of the study, resulting in a non-representative sample. Participation was voluntary, no reward was given.

Measures

Personality characteristics. Students were asked about their gender, age, years in college, and type of study program by single open questions. Gender (male, female) and type of study program (teacher education, other majors) are dichotomous variables. For all scale formations, we added the values of the items and divided the resulting sum by the number of items.

Big Five personality traits and altruism. For measuring the traits of the five-factor theoretical model of personality, we used the 40-item version of the International Personality Item Pool (IPIP40; Hartig et al., Citation2003). Each of the following personality traits were measured using 8 items with answer alternatives ranging from (1) ‘very inaccurate’ to (5) ‘very accurate’: Openness (as being open-minded), Neuroticism (as experiencing the world as threatening), Extraversion (as orientation toward the outer world), Conscientiousness (as being careful) and Agreeableness (as being friendly). In addition to the big five personality traits, we focused on altruism as it was not only found to relate to collegiality, but also seems to be a separate and independent personality-related trait. Altruism (as concern for the well-being of others) was measured with four items from an adapted scale by Johnston et al. (Citation2010): ‘I assist other students in case of study problems’, ‘I assist other students having personal problems’, ‘I share study documents with other students’ and ‘If necessary, I advise other students on study problems’. Answer alternatives ranged from (1) ‘absolutely false’ to (5) ‘absolutely true’.

Academic self-concept. Academic self-concept (as evaluation of success in learning settings) was measured using five items with dichotomous answer alternatives (from ‘completely agree’ to ‘completely disagree’) based on Dickhäuser et al. (Citation2002) and their theoretical reference norm concepts: ‘I am gifted for studying’, ‘I find it easy to learn new things’, ‘I am very intelligent’, ‘I can do a lot in studying’, and ‘Many tasks come easy to me during my studies’.

Multi-dimensional goal orientations. In order to measure goal orientations, slightly adapted scales from Dickhäuser et al. (Citation2007) and related achievement goal theory were used. Answer scales ranged from (1) ‘absolutely agree’ to (5) ‘absolutely disagree’. The eight item sub-scale ‘performance avoidance goal orientation’ was intended to measure whether students tried to conceal their weaknesses and hide their deficits (sample item: ‘My studies are about … not embarrassing myself in front of others’). ‘Performance approach goal orientation’ was measured with seven items (‘ … showing that I am a good student’). This sub-scale aimed at measuring how strong students tended to demonstrate their own skills. The sub-scale on ‘learning goal orientation’ had eight items and was used to measure how hard students focused to broaden their skills (‘ … getting new ideas’). These goal orientations have a cognitive and a motivational facet. We also focused on courtesy as it represents a social-emotional goal orientation, which is important as collegiality is always embedded in social contexts. Courtesy (as a pursuit of polite and respectful behavior) was measured with two items from a theory-based and adapted scale by Johnston et al. (Citation2010): ‘I show respect for other students’ and ‘I get on well with most students’. Answer alternatives ranged from (1) ‘absolutely disagree’ to (5) ‘absolutely agree’.

Collegiality. Positive and negative collegiality were measured with 28 items each from a theory-based and adapted scale by Astleitner (Citation2021; see ). This scale was originally developed for measuring college professors’ collegiality and was adapted for students by the second author of this study. The positive collegial behavior scale covered seven positive behaviors (each concept measured with four items) like being friends, cooperating, positive citing, positive proposing, using ideas, being honest and open, as well as positive intentions towards colleague(s). The negative collegial behavior scale also focused on seven conceptual behaviors (with four items) like ignoring ideas, negative proposing, negative citing, supporting opponents, mobbing, cheating on colleagues, and negative intentions. Participants had to rate the items based on a 5-point scale ranging from (1) ‘completely disagree’ to (5) ‘completely agree’.

Table 1. Means and standard deviations for single items on student collegiality.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were computed with SPSS 26. Manifest variable path analysis was conducted with LISREL 8.8. Before data analyses, we considered Barbeau et al. (Citation2019, p. 42): (1) All our endogenous variables were continuous data. (2) We had only 3.56% missing values in only one variable (type of study program), affected participants were excluded in computations. (3) A test on the multivariate normality of our 17 variables was negative (Henze-Zirkler = 1.05, p < .001; Henze & Zirkler, Citation1990; URL https://statistikguru.de/rechner/multivariate-normalverteilung.html). Nevertheless, we achieved an acceptable non-normal data situation since only one variable (i.e., age with 2.56 and 10.57) did not show any skewness between −2 and +2 and a kurtosis between −7 and +7. Hence, for data processing, a Pearson correlation matrix and Maximum Likelihood (ML) estimation were used, assuming that our sample size of about 200 allows robust estimations in LISREL (Boomsma & Hoogland, Citation2001). (4) We had multivariate outliers in only four participants based on Mahalanobis Distances and related p-values of the chi-square distribution calculated in SPSS (Meyers et al., Citation2013, p. 131; see URL https://www.statisticssolutions.com/identifying-multivariate-outliers-in-spss/). Due to the small number of participants and not wanting to underestimate variability in the data, we decided to leave them in the sample. (5) We did not have correlations r = .85 or larger in our sample, indicating no high collinearity between variables (see ). (6) In order to approximately estimate a minimum sample size with acceptable power, we used the G*Power 3.1-Software (Faul et al., Citation2009) to calculate a minimum sample size (for linear multiple regression with random model, critical R2 = 0.15, p = .05, Power = 0.95, number of predictors: 16). The resulting estimated sample size of N = 180 is close to the sample size in this study indicating sufficient power of our tests. For evaluating the model fit, the following goodness-of-fit indices were used: the ratio of the chi-square value to its degrees of freedom, the non-normed fit index (NNFI), the comparative fit index (CFI), root mean square of approximation (RMSEA) and its confidence interval (Jöreskog et al., Citation2016).

Table 2. Descriptive statistics, scale reliabilities and correlations.

Results

shows means and standard deviations of the positive and negative student collegiality scales. In summary, answers indicate that positive collegiality was rated high and negative collegiality low.

displays the psychometric characteristics of the variables in our study and the correlations among these variables. We tested the internal consistency for each scale by calculating Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient (CA). Two items of the original scales were dropped due to bad reliability for the questionnaire on courtesy (resulting CA = .67). One item on approach goal orientation was also dropped (CA = .80). For all the other questionnaires, acceptable to very good reliabilities could be achieved: CA ranged from .63 (agreeableness) to .92 (positive collegiality; see ). In general, values indicated that internal reliability within the questionnaires was acceptable or even good in some cases.

Indicators of validity for our scales were found in past studies for all variables except for collegiality (see references on the instruments). In order to obtain information on the validity of collegiality scales we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis with LISREL. Within this analysis, we tested whether the items belonged to the assumed positive and negative dimensions of collegiality. There were 28 items for the latent variable positive collegiality and 28 items for the latent variable negative collegiality. Results showed an acceptable fit: χ2 (1470, N = 189) = 1445.47, p > .05, NNFI = 1.00, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .00, 90% confidence interval (CI) for RMSEA [.00, .02]. All t-values for factor loading (indicator for validity) and error variances (indicator for reliability) were significant: t > 2.75. We allowed 13 correlated measurement errors for variables, but only within the same construct. The model fit improved if correlated errors were added to the model. However, correlated errors are also indicators of mis-specifications or wording problems resulting in lack of validity. Modification indices indicated adding 11 more paths from latent and indicator variables, which we did not allow. Overall, confirmatory factor analysis revealed some preliminary evidence that the 56 items are related to two dimensions of collegiality. However, results also showed that there could be more constructs involved or that some items might measure both constructs. In our single-item-based confirmatory factor analysis, we found a significant correlation of r = −0.67 between the latent factors of positive and negative collegiality. This correlation changed to r = −.0.47 based on building the sum of single items for each factor (see ). According to such analyses, positive and negative collegiality are therefore not independent of each other.

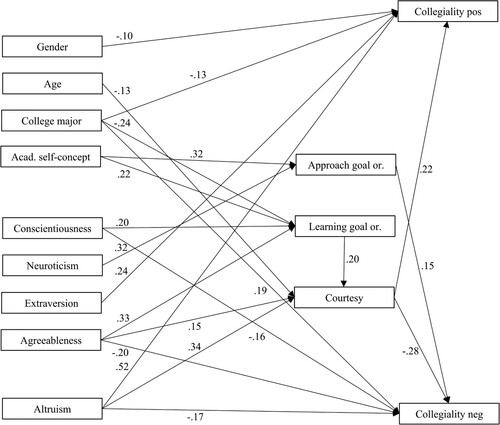

Path analysis results are shown in . All standardized coefficients were significant at the .05 level. The estimated model demonstrated a good fit to the data: χ2 (34, N = 189) = 34.81, p > .05, NNFI = 1.00, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .01, 90% confidence interval (CI) for RMSEA [.00, .06], no modification indices.

Figure 1. Parameter estimates of the tested model.

Note: The figure shows standardized path coefficients from the LISREL analysis. All lines represent significant paths, p < .05.

The hypothesized model adequately describes the relationships between personality characteristics and traits, goal orientations, and their influences on collegiality.

In our path model, we identified a good model fit that shows no significant relationship between positive and negative collegiality. If we integrate a correlation between positive and negative collegiality into the model, a non-significant correlation of r = −0.03 (p > .05) emerges and the model fit changes minimally: χ2 (33, N = 189) = 34.49, p > .05, NNFI = 1.00, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .02, 90% confidence interval (CI) for RMSEA [.00, .06]. Originally, there was a significant bivariate correlation between the two variables (r = −0.47, p < .05; see ), but the other variables in the path analysis model affected the relationship of positive and negative collegiality. The model showed an explained variance (R2) for positive collegiality of .64, and for negative collegiality of .42.

The standardized path coefficients in can be interpreted as follows: Gender and type of study program affected collegiality in a way so that being female and studying in the teacher training program are significantly related to positive collegiality. Positive collegiality was also higher for participants with higher values on extraversion, altruism, and courtesy. Negative collegiality was higher among students not studying in the teacher training program and for students with higher approach motivation goal orientation. It also correlated negatively with conscientiousness, agreeableness, altruism, and courtesy. In addition, participants showed higher levels of approach motivation goal orientation together with higher levels of academic self-concept and neuroticism. Students studying in regular curricula showed higher learning goal orientations than students studying in the teacher training program. They also showed higher levels of academic self-concept, conscientiousness and agreeableness. Finally, courtesy was found to be related negatively to age, but positively to agreeableness and altruism.

Discussion

The findings of this study partially supported our goal-related assumptions that there are significant interrelations between personality characteristics and traits as well as goal orientations and collegiality among higher education students.

First, from a theoretical perspective, our results are, in general, related to and supported by the model on pro-social development from Eisenberg et al. (Citation2015) and the model of collegiality by Astleitner (Citation2021). However, we did not focus on all variables from the first model. For example, we only included one indicator of the theoretical aspect of socialization, namely academic major/study program. We also excluded affective states or empathy-related responding. Our findings also provide evidence on the collegiality model by Astleitner (Citation2021), however, only for two higher-order, but not for all lower-order dimensions in the model.

Second, as we mentioned before, there is little research on higher education students’ collegiality; therefore, it is difficult to relate our findings to existing research within the same target group. Despite this lack of comparable research, we were able to achieve our study goal and to find evidence that positive and negative collegiality simultaneously exist among higher education students, that they are stimulated by different personal triggers and processes, and that they may vary due to changes in the study environment. Positive and negative collegiality correlate with many different variables in our model. Only few variables, like study program, altruism, and courtesy, relate to both dimensions of collegiality (in the opposite direction). Our study differs from other research because it is based on a combination of pro- and antisocial behavior, on self-ratings, and on non-causality survey results. On the one hand, we know that self-ratings’ validity is questionable, especially when negative or problematic behavior has to be evaluated. On the other hand, research indicates good validity for such ratings (e.g., Stanton et al., Citation2019).

Nevertheless, our findings that being female in comparison to being male relates differently to positive collegiality, correspond to similar research findings, at least when examining teachers (e.g., Mora-Ruano et al., Citation2018). Studying in a socially-orientated academic major (teacher training program) correlates positively with collegiality. This is consistent with other results indicating that students of humanities and social sciences show higher values of self-transcendence (e.g., social contribution) compared to other major students (e.g., Balsamo et al., Citation2013). Correlations between collegiality and conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and altruism are supported by research identifying relationships between conscientiousness and interpersonal aggression (Bogg & Roberts, Citation2004), extraversion and social connectedness (Lee et al., Citation2008), agreeableness and helping others (Teng et al., Citation2012), or altruism and social support (Li et al., Citation2018). The relationships between collegiality and approach motivation goal orientation as well as collegiality and courtesy that we discovered coincide with findings by Yasuda (Citation2009) on approach goals and sense of community. The relationships we identified between academic self-concept and the Big Five personality traits with goal orientations correspond to evidence, for instance, by Seaton et al. (Citation2014). Finally, we discovered a relationship between learning goal orientation and courtesy that is similar to findings by Hong et al. (Citation2009).

Limitations

There are a number of limitations of our study, affecting various theoretical and methodological aspects. Although our assumptions and methods were based on actual research findings, our study was exploratory in nature and only partially achieved its goals; however, it showed significant potential for innovation. We tried to measure higher education student collegiality with a two-dimensional and research-behavior-focused perspective. As far as we know, this was done for the first time in higher education contexts. Therefore, our study offers a starting point for learning more about collegiality among higher education students. Of course, social desirability as an influencing factor might be given, since this study was based on self-report measures without including observations of behaviors or other different methodologies. Also, two of our variables (agreeableness and courtesy) only reach acceptable, but not good reliability; therefore, the corresponding findings need to be interpreted accordingly. Moreover, our scales for collegiality might have more latent factors than the two that our analysis focused on. In our factor and correlation analyses, we found significant correlations when assuming two factors. In path analysis, the included set of variables led to a non-significant correlation between positive and negative collegiality. The question of the dependence or independence of the two or more factors as well as their embeddedness in higher-order factors must be clarified in future studies. The relationships we found among variables in our path analysis must be considered as preliminary and still need to be investigated, since we had no specific hypotheses, no latent factors, no reciprocal links, or no error-reduction strategies within our analyses (Cole & Preacher, Citation2014). In this study, we focused on direct effects only. We have not tested indirect effects or more complex moderations or moderated mediations because the current state of research does not deliver sufficient theoretical background or empirical evidence. However, some exploratory analysis revealed that there are also several significant indirect effects in our model related to courtesy (from college major, academic self-concept, conscientiousness and agreeableness) as well as to positive collegiality (from college major, academic self-concept, agreeableness and altruism) and negative collegiality (from college major, neuroticism, agreeableness and altruism) (−1.96 > all t > 1.96). In addition, larger sample sizes and more pronounced normally distributed data situations could provide further insight into this study’s variable patterns. Another problem for the interpretation of our results concerns sample selection. Our sample was mainly based on female teacher education students at an early stage in their education. Therefore, and due to a convenience sampling, our results have low external validity. However, the goal of this study was not to have a representative sample, but a sample that is appropriate for exploring and testing the measurement quality of a new instrument. We tested a network of hypotheses to gain information on the construct validity of the measurement instrument. External validity must be tested in follow up studies: Other higher education students might differ from this group regarding personality, personality development, prosocial behavior or collegiality (e.g., Corcoran & O’Flaherty, Citation2016). Finally, all of our participants had a Western European background, limiting findings of this study to this population. Samples within or including students with different cultural background (e.g., from more collectivistic cultures) might lead to different outcomes.

Implications

First of all, our study underlines the significance of higher education research on higher education students’ collegiality. Therefore, we developed and tested instruments measuring behavioral-respective skill-related facets of higher education students’ collegiality. These instruments can be used in the future for further validation attempts, studies on student behavior in research contexts, or especially in studies concerning higher education students’ personality characteristics and their development during attending university.

This instrument might also be suitable as a tool for exploratory screening in the context of student social development in future research activities. Students can use it to create collegiality profiles showing individual strengths and weaknesses. Based on such profiles, it might be possible to implement strategies for promoting collegiality among higher education students. These strategies could in turn be implemented in courses or trainings on social development, institutional mobbing, empathic communication, or research ethics (Israel, Citation2014).

Informed consent

Participation was voluntary. All ethical standards were applied.

Code availability

Codes available on request.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Burkhard Gniewosz for his comments on the statistical analyses. Both authors contributed to all parts of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data and material are available on request.

References

- Afolabi, O. A. (2014). Do self esteem and family relations predict prosocial behaviour and social adjustment of fresh students? Higher Education of Social Science, 7(1), 26–34. https://doi.org/10.3968/5127

- Agbaria, Q., & Mokh, A. A. (2022). Coping with stress during the coronavirus outbreak: The contribution of big five personality traits and social support. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 20(3), 1854–1872. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-021-00486-2

- Astleitner, H. (2021, September). Collegiality in research within an entrepreneurial university – an activity-context model for self-assessment-based educational improvement and quality assurance [Paper presentation]. European Conference on Educational Research (ECER), Geneva, Switzerland. https://www.plus.ac.at/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/CiR_AS_ECER21.pdf

- Balsamo, M., Lauriola, M., & Saggino, A. (2013). Work values and college major choice. Learning and Individual Differences, 24, 110–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2012.12.022

- Barbeau, K., Boileau, K., Sarr, F., & Smith, K. (2019). Path analysis in Mplus: A tutorial using a conceptual model of psychological and behavioral antecedents of bulimic symptoms in young adults. The Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 15(1), 38–53. https://doi.org/10.20982/tqmp.15.1.p038

- Bogg, T., & Roberts, B. W. (2004). Conscientiousness and health-related behaviors: A meta-analysis of the leading behavioral contributors to mortality. Psychological Bulletin, 130(6), 887–919. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.6.887

- Boomsma, A., & Hoogland, J. J. (2001). The robustness of LISREL modeling revisited. In R. Cudeck, S. du Toit, & D. Sörbom (Eds.), Structural equation models: Present and future (pp. 139–168). Scientific Software International.

- Branas-Garza, P., Cobo-Reyes, R., Espinosa, M. P., Jiménez, N., Kovářík, J., & Ponti, G. (2010). Altruism and social integration. Games and Economic Behavior, 69(2), 249–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geb.2009.10.014

- Bray, R., & Boon, S. (2011). Towards a framework for research career development. International Journal for Researcher Development, 2(2), 99–116. https://doi.org/10.1108/17597511111212709

- Chamorro-Premuzic, T., Arteche, A., Bremner, A. J., Greven, C., & Furnham, A. (2010). Soft skills in higher education: Importance and improvement ratings as a function of individual differences and academic performance. Educational Psychology, 30(2), 221–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410903560278

- Cole, D. A., & Preacher, K. J. (2014). Manifest variable path analysis: Potentially serious and misleading consequences due to uncorrected measurement error. Psychological Methods, 19(2), 300–315. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033805

- Corcoran, R. P., & O’Flaherty, J. (2016). Personality development during teacher preparation. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1677. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01677

- Davis, S. N., & Wagner, S. E. (2019). Research motivations and undergraduate researchers’ disciplinary identity. SAGE Open, 9(3), 215824401986150. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244019861501

- Deniz, M., Hamarta, E., & Ari, R. (2005). An investigation of social skills and loneliness levels of university students with respect to their attachment styles in a sample of Turkish students. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 33(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2005.33.1.19

- Dickhäuser, O., Butler, R., & Tönjes, B. (2007). Das zeigt doch nur. dass ich’s nicht kann. Zielorientierung und Einstellung gegenüber Hilfe bei Lehramtsanwärtern [That just shows I can’t do it: Goal orientation and attitudes concerning help amongst pre service teachers]. Zeitschrift für Entwicklungspsychologie und Pädagogische Psychologie, 39(3), 120–126. https://doi.org/10.1026/0049-8637.39.3.120

- Dickhäuser, O., Schöne, C., Spinath, B., & Stiensmeier-Pelster, J. (2002). Die Skalen zum akademischen Selbstkonzept: Konstruktion und Überprüfung eines neuen Instrumentes [The academic self concept scales: Construction and evaluation of a new instrument]. Zeitschrift für differentielle und diagnostische Psychologie: ZDDP, 23(4), 393–405. https://doi.org/10.1024//0170-1789.23.4.393

- Eisenberg, N., Spinrad, T. L., & Knafo-Noam, A. (2015). Prosocial development. In R. M. Lerner (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology and developmental science (Vol. 3, pp. 610–656). Wiley.

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A. G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

- Ferrari, J. R., McCarthy, B. J., & Milner, L. A. (2009). Involved and focused? Students’ perceptions of institutional identity, personal goal orientation and levels of campus engagement. College Student Journal, 43(3), 886–897. https://go.gale.com.

- Hartig, J., Jude, N., & Rauch, W. (2003). Entwicklung und Erprobung eines deutschen Big-Five-Fragebogens auf Basis des International Personality Item Pools (IPIP40) [Development and trial of a German Big Five questionnaire based on the International Personality Item Pool (IPIP40)]. Institut für Psychologie an der Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität.

- Haviland, D., Alleman, N. F., & Cliburn Allen, C. (2017). ‘Separate but not quite equal’: Collegiality experiences of full-time non-tenure-track faculty members. The Journal of Higher Education, 88(4), 505–528. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2016.1272321

- Henze, N., & Zirkler, B. (1990). A class of invariant consistent tests for multivariate normality. Communications in Statistics – Theory and Methods, 19(10), 3595–3617. https://doi.org/10.1080/03610929008830400

- Hong, E., Hartzell, S. A., & Greene, M. T. (2009). Fostering creativity in the classroom: Effects of teachers’ epistemological beliefs, motivation, and goal orientation. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 43(3), 192–208. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2162-6057.2009.tb01314.x

- Hsieh, P., Sullivan, J. R., & Guerra, N. S. (2007). A closer look at college students: Self-efficacy and goal orientation. Journal of Advanced Academics, 18(3), 454–476. https://doi.org/10.4219/jaa-2007-500

- Israel, M. (2014). Research ethics and integrity for social scientists (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Johnston, P. C., Schimmel, T., & O’Hara, H. (2010). Revisiting the AAUP recommendation: Initial validation of a university faculty model of collegiality. College Quarterly, 13(2), http://collegequarterly.ca/2010-vol13-num02-spring/johnston.html

- Jöreskog, K. G., Olsson, U. H., & Wallentin, F. Y. (2016). Multivariate analysis with LISREL. Springer.

- Kligyte, G., & Barrie, S. (2014). Collegiality: Leading us into fantasy – the paradoxical resilience of collegiality in academic leadership. Higher Education Research & Development, 33(1), 157–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2013.864613

- Lee, R. M., Dean, B. L., & Jung, K. R. (2008). Social connectedness, extraversion, and subjective well-being: Testing a mediation model. Personality and Individual Differences, 45(5), 414–419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2008.05.017

- Li, R., Jiang, T., Yong, J., & Zhou, H. (2018). College students’ interpersonal relationship and empathy level predict internet altruistic behavior—empathy level and online social support as mediators. Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, 7(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.pbs.20180701.11

- Macfarlane, B. (2016). Collegiality and performativity in a competitive academic culture. Higher Education Review, 48, 31–50. http://www.highereducationreview.com/news/collegiality-and-performativity-in-a-competitive-academic-culture.html

- Mansson, D. H., & Myers, S. A. (2012). Using mentoring enactment theory to explore the doctoral student-advisor mentoring relationship. Communication Education, 61(4), 309–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634523.2012.708424

- McGrath, C., Roxå, T., & Bolander Laksov, K. (2019). Change in a culture of collegiality and consensus-seeking: A double-edged sword. Higher Education Research & Development, 38(5), 1001–1014. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1603203

- Meyers, L. S., Gamst, G. C., & Guarino, A. J. (2013). Performing data analysis using IBM SPSS. Wiley.

- Miles, M. P., Shepherd, C., Rose, J. M., & Dibben, M. (2015). Collegiality in business schools. International Journal of Educational Management, 29(3), 322–333. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-02-2014-0022

- Moeller, R. W., & Seehuus, M. (2019). Loneliness as a mediator for college students’ social skills and experiences of depression and anxiety. Journal of Adolescence, 73(6), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.03.006

- Mora-Ruano, J. G., Gebhardt, M., & Wittmann, E. (2018). Teacher collaboration in German schools: Do gender and school type influence the frequency of collaboration among teachers? Frontiers in Education, 3, 55. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2018.00055

- Olsen, L. D., & Gebremariam, H. (2022). Disciplining empathy: Differences in empathy with U.S. medical students by college major. Health: An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness and Medicine, 26(4), 475–494. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459320967055

- Panteli, M., Vaiouli, P., Leonidou, C., & Panayiotou, G. (2021). Perceived stress of Cypriot college students during COVID-19: The predictive role of social skills and social support. European Journal of Psychology Open, 80(1-2), 31–39. https://doi.org/10.1024/2673-8627/a000005

- Park, S., & Shin, J. (2017). The influence of anonymous peers on prosocial behavior. PLoS One, 12(10), e0185521. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0185521

- Rhee, J., Parent, D., & Basu, A. (2013). The influence of personality and ability on undergraduate teamwork and team performance. SpringerPlus, 2(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/2193-1801-2-16

- Rinn, A., Boazman, J., Jackson, A., & Barrio, B. (2014). Locus of control, academic self-concept, and academic dishonesty among high ability college students. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 88–114. https://doi.org/10.14434/v14i4.12770

- Rubin, M., & Wright, C. L. (2017). Time and money explain social class differences in students’ social integration at university. Studies in Higher Education, 42(2), 315–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1045481

- Seaton, M., Parker, P., Marsh, H. W., Craven, R. G., & Yeung, A. S. (2014). The reciprocal relations between self-concept, motivation and achievement: Juxtaposing academic self-concept and achievement goal orientations for mathematics success. Educational Psychology, 34(1), 49–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2013.825232

- Stanton, K., Brown, M. F., Bucher, M. A., Balling, C., & Samuel, D. B. (2019). Self-ratings of personality pathology: Insights regarding their validity and treatment utility. Current Treatment Options in Psychiatry, 6(4), 299–311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40501-019-00188-6

- Teng, C.-I., Lee, I.-C., Chu, T.-L., Chang, H.-T., & Liu, T.-W. (2012). How can supervisors improve employees’ intention to help colleagues? Perspectives from social exchange and appraisal-coping theories. Journal of Service Research, 15(3), 332–342. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670511435538

- Trigwell, K. (2005). Teaching? Research relations, cross-disciplinary collegiality and student learning. Higher Education, 49(3), 235–254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-004-6665-1

- Tseng, H., Yi, X., & Yeh, H.-T. (2019). Learning-related soft skills among online business students in higher education: Grade level and managerial role differences in self-regulation, motivation, and social skill. Computers in Human Behavior, 95, 179–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.11.035

- Wankel, L. A., & Wankel, C. (2012). Misbehavior online in higher education. Emerald.

- Yasuda, T. (2009). Psychological sense of community in university classrooms: Do achievement goal orientations matter? College Student Journal, 43(2), 547–561.