ABSTRACT

Research educators, scholars, and employers often debate the nature and purpose of doctoral training. Should doctoral degrees exist only to make new knowledge and replenish the academic workforce or are they part of broader societal-enhancement and employment agendas? Or both? This study aimed to identify and analyse tensions in Australian employability discourse in the doctoral degree. We systematically reviewed 41 articles published in journals and conferences on Australian doctoral employability training from 2000 to 2022 and put them in context with the broader debate about doctoral employability in the so-called ‘grey literature’ of government reports and policy papers. Our findings indicated that stakeholders are all grappling with the difficulty of meeting diverse learning needs and there are contested understandings of the value of the doctoral degree beyond academia. At the same time, we found a relatively poor evidence base for many claims that outcomes of doctoral education are poor for both students and employers. This paper will be of interest to research educators seeking to implement new training programs and policy makers trying to craft new initiatives to connect doctoral education with industry.

Introduction

The PhD was originally conceived as training for academia, but now graduates go on to a wide range of careers (Vitae, Citation2013; Quality Indicators for Learning and Teaching (QILT), Citation2021). Clearly PhD students need to be prepared for a range of career outcomes, but there is no consistent approach to embedding employability skills in the PhD curriculum. Taking a global view of the issues around doctoral education is useful for informing this ongoing debate (Sharmini & Spronken-Smith, Citation2020), but many international ‘solutions’ to local problems run the risk of missing out on characteristics specific to a national context (Thomson, Citation2016). For example, Australia has a massified and marketized education system (Marginson & Considine, Citation2000) with a larger proportion of international PhD candidates than most OECD countries (OECD, Citation2019). The Australian doctoral education system includes Indigenous candidates (e.g., Aboriginals and Torres Strait Islanders) and provides a wide range of priority schemes in all universities to support their success. Therefore, it is necessary to carefully examine local characteristics of doctoral education to make the Australian PhD curriculum fit for purpose in the twenty-first century. To this end, this paper provides a detailed exploration of the literature on the issue of employability within Australian doctoralFootnote1 education with a view to making recommendations for future scholarly research, education, and policymaking.

It is widely acknowledged that the Australian academic job market can no longer absorb all doctoral graduates. More than a decade ago, Neumann et al. (Citation2008) noticed that only 23% of doctoral graduates in Australia were employed in research and teaching positions within academia. Both increasing casualization (Bosanquet et al., Citation2020) and heavy workload in academia (Bosanquet et al., Citation2020; McKinstry et al., Citation2020) seem to have ‘disillusioned’ many doctoral graduates. As a result, both governments and universities have been putting effort into making PhD graduates more employable beyond academia.

While lists of employability goals set out in policy papers get longer, a coherent pedagogy to achieve that aim remains elusive. Scholars have noticed how unstructured doctoral skills training and industry programs can be (e.g., Manathunga et al., Citation2009; Molla & Cuthbert, Citation2015, Citation2019; Platow, Citation2012). It is hard – and perhaps pointless – to assign blame for this incoherence; pedagogical improvements only happen if we try new initiatives. But unless we have some idea of what has worked (or not) in the past, we cannot move forward with confidence. By examining the relevant available literature, this paper will provide valuable context for research educators attempting to design curriculum and policy makers looking to drive new initiatives.

Some of the current issues in PhD graduate employability can be traced back decades. It was not until 1948 that the first three PhDs were awarded in Australia (CBCS, Citation1952). Up to the second World War (WW2), Australia was an ‘importer’ of PhD talent, largely from the UK. After WW2, Australians looked to the USA for inspiration. PhD education was framed as a way to give countries a competitive edge (Dufty-Jones, Citation2018).

While the idea of PhD graduates as an economic benefit is deeply entrenched in Australia, initially the PhD did not have a direct relationship with industry. The PhD was seen as a way of building the academic workforce and capacity for both research and teaching (Kemp, Citation1999). This strategy seemed to pay off until the mid-1990s, when the Australian academic workforce became increasingly unable to absorb all its PhD graduates (Kiley, Citation2017; McCarthy & Wienk, Citation2019).

The uneven balance between demand and supply of PhDs was one of the drivers behind the policy statement by Kemp (Citation1999), which called for greater engagement with industry. This discussion paper on doctoral education suggested a range of policy changes to increase PhD completion rates, shorten completion time, and strengthen links with industry. Kemp pointed out the problem of skills inadequacy among Australian research graduates and the need to formalize training. The Research Training Scheme (RTS) was a direct outcome of this report, providing universities with direct government funding for research training for the first time. At the same time, domestic candidates had access to fee offsets and stipends to encourage participation. The design of the RTS aligned with ‘marketisation’ reforms of education in the late twentieth century (Marginson & Considine, Citation2000), providing a range of policy ‘carrots and sticks’; they have morphed over time into what is now called the Research Training Program (RTP) that provides, for instance, higher returns for universities to train a greater number of Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) PhDs. Crucially, the RTS also punished universities for non-completions, by only paying in arrears, forcing universities to shoulder all the risk. As a result, a whole species of specialists in research education was spawned, some of whom work in universities and others consult and provide services. The government has continued to ‘tinker’ with this system, for example, in 2022 proposing a ‘bonus payment’ for candidates who complete an industry internship during candidature.

Although Australian politicians have made claims to developing a prosperous and expanding higher education sector via policies such as the RTP, Coates et al. (Citation2020a) argue that Australian doctoral education is not optimized yet, specifically with respect to catering to students and stakeholders’ needs. A range of government and commissioned reports (e.g., ACOLA, Citation2012; Australian Government Department of Education and Department of Industry, Citation2014; The Allen Consulting Group, Citation2010) and empirical studies (e.g., Dufty-Jones, Citation2018; Guerin, Citation2020; Pitt, Citation2008) all raise different concerns. Stakeholders have constantly referred to efficiency, relevance, and employability problems related to doctoral programs in Australia (e.g., Hodgson et al., Citation2021; Molla & Cuthbert, Citation2015; Pitt & Mewburn, Citation2016). Employers, even academic employers, have claimed PhD-level graduates do not always meet their expectations (ACOLA, Citation2016; Pitt, Citation2012; The Allen Consulting Group, Citation2010). Younger PhD graduates have expressed apprehension about lacking industry experience, while older PhDs with industry experience report being stressed about employment precarity due to family, financial, and health-related issues (Spina et al., Citation2022). PhD graduates continue to be disillusioned with outcomes of the PhD in relation to their career (Guerin, Citation2020).

Doctoral education has become a site of anxiety within the academy, surrounded by what Molla and Cuthbert (Citation2015) call a ‘PhD crisis discourse’. Positive stories about the PhD are not common in the Australian news media, and the ‘chatter’ in social media groups containing or pertaining to doctoral study is filled with ‘doom and gloom’ predictions and stories of mental health issues. Sydney Morning Herald’s opinion article authored by the PhD graduate Astore (Citation2022) is a good example of PhDs feeling disheartened and ill-supported in Australia. Many current Australian institutional responses to ‘PhD crisis discourse’, such as industry programs and skill training courses, have been based on the assumption that industry employers’ expectations for doctoral employees were not met (Molla & Cuthbert, Citation2015), but has sufficient research really been done? The rest of this paper will outline a more detailed picture of this ‘crisis discourse’ around post-PhD employability through a systematic review of 41 included articles from 2000 to 2022. So far as we are able to ascertain, there has been no published literature survey of Australian doctoral employability. One of our aims is to find gaps and opportunities to expand knowledge.

Review design

This paper systematically reviews relevant peer-reviewed journal articles and conference papers published on doctoral education in Australia over the past 22 years to identify and analyze tensions in doctoral employability discourse. The selected timeframe begins in 2000, as this marked the introduction of the RTS (now RTP) and the framing of the PhD as part of a government skills and employment agenda for national prosperity.

Our study methods drew on keywording strategies (Evidence for Policy and Practice Information Centre (EPPI-Centre), Citation2022) and rigorous data search, evaluation, and analysis processes (Whittemore & Knafl, Citation2005). Keywording strategies we used for narrowing the scope of the literature through SuperSearch and Google Scholar for our research purpose were as follows:

We confined our search to papers with titles that have the terms ‘PhD’/‘Ph.D’/‘Doctora* ‘ to pinpoint doctoral education studies.

We further narrowed down the most relevant papers with the strings ‘Austral*’ in combination with ‘*employ*’/‘satisf*’/‘job*’/‘work*’/‘*demand*’/‘*suppl*’/‘career*’/‘*skill*’/‘destin*’/‘train*’ in the abstracts.

Our selection process included peer-reviewed articles published from January 2000 to January 2022, featuring data-based studies, policy documents, and theoretical commentaries from Australia, with PhD employability as the primary criterion. Journal articles and conference papers meeting our standards were chosen. Despite not being as well-indexed, book chapters, other reviews, conference abstracts, theoretical papers, and grey literature offer valuable insights into Australian doctoral employability. In-depth analyses of important grey literature on Australian doctoral employability training and changes in Australian doctoral education are available in scholarly works such as Molla and Cuthbert (Citation2015) and Kiley (Citation2017). Consequently, we only sought to locate and incorporate as much important grey literature as possible into our analysis.

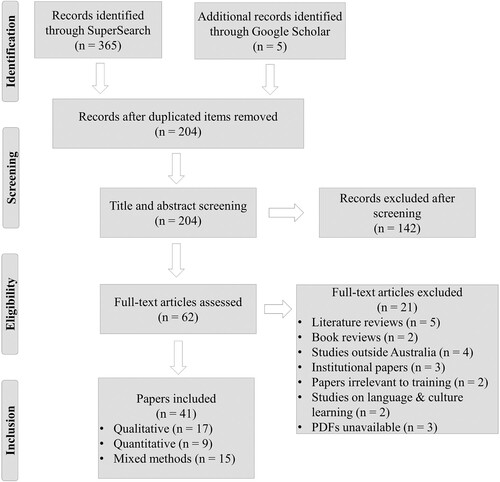

We (the three co-authors) reviewed selected papers’ titles and abstracts to determine their relevance to our question on tensions in doctoral employability training. After consensus on screening and quality assessment, data analysis commenced. The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis) flow diagram in outlines the detailed process for data extraction and synthesis (Tricco et al., Citation2018).

We coded the textual data and mapped out themes recurring across all included papers, followed by their clustering into broader groups. We adopted a textual approach to synthesis; telling the story of the findings from the selected papers. After presenting the findings from the selected papers, we included discussions of implications by drawing on other studies not necessarily targeting Australia. Hence, there will be two reference lists, one with only the selected papers for our data analysis, and another with references we used for supporting our findings.

Results and analysis

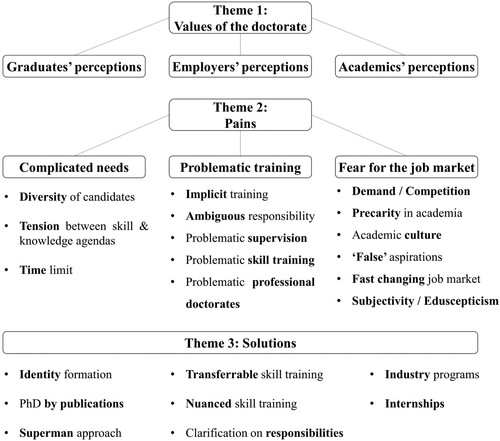

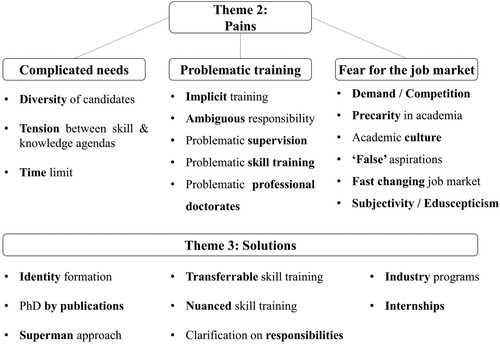

We found three broad themes across all 41 included papers: (1) values of the doctorate perceived by various stakeholders, (2) problems (pains) of Australian doctoral employability training, and (3) proposed solutions to these pains ().

Values of the doctorate in the eyes of various Australian stakeholders

The content analysis of the 41 included articles suggested that all stakeholders of doctoral education in Australia, with the notable exception of the government, have acknowledged the value of doctoral degrees. The value of the doctorate conveyed by graduates themselves and industry employers seemed to be mainly concerned with human capital (e.g., skill attainment) and social capital (e.g., credibility and respect), whereas academics tended to view the value in moral terms. Although the analysis also revealed stakeholders’ negative opinions about the degree in Australia, we will first focus on positive perspectives.

Values of the doctorate perceived by graduates

Out of the 41 articles, 12 used empirical evidence (mostly interviews and surveys) to claim that doctoral graduates in Australia positively associated their degrees and study experience with dimensions of social and human capital. has more detail.

Table 1. Papers demonstrating the values of the doctorate perceived by graduates.

Our review implied that there is clearly much more work to do to gauge how satisfied research degree graduates are with their training and career preparation. It should be noted that the above 12 studies were conducted within a very small number of Australian universities. In addition, the authors of the reviewed papers relied heavily on statistics or anecdotal narratives from other countries to frame their commentary about positive doctorate outcomes. For instance, stories in the US, UK, and Canada about successful PhDs in industry were often cited in the reviewed papers, rather than Australian evidence.

Value of the doctorate perceived by employers

Only two included articles had empirical evidence of industry employers’ opinions about doctoral graduates as employees. These two papers (Borbasi & Emden, Citation2001; Pitt, Citation2012) both showed industry employers valued doctoral employees’ in-depth knowledge, research capabilities, and ability to synthesize knowledge. For instance, nursing industry employers in Borbasi and Emden (Citation2001) listed qualities of their PhD hires that they liked, namely, ambition, confidence, risk management, and the ability to access important resources. But both papers showed employers asking questions about doctorates being ‘over-qualified’ or ‘over-specialized’ for industry jobs.

Within the rest of the literature we surveyed, industry employers’ dissatisfaction with PhD employability was the most cited reason for the need to drive changes in Australian doctoral education, but based on our review, it was hard to see sufficient scholarly evidence to support this claim. It is reasonable now to question the necessity of constantly seeking employers’ evaluations of their doctorate employees. A more beneficial approach might be to explore if and why a doctorate degree influenced employers’ hiring decisions.

Values of the doctorate perceived by academics

We only found five articles that tackled the issue of academic opinion on the doctorate – a very small output considering how important academia is an employer of PhD graduates. Our analysis suggested that academics tend to put an emphasis on the moral incentives of the doctorate, namely the quality of research being produced and the contribution to academia as a profession ().

Table 2. Explication of the non-financial contributions perceived by academics.

It is worth noting that these five articles largely offered the authors’ critique and were not argued from a specific evidence base; if empirical testing of these claims was desirable, although we acknowledge this would be difficult, international literature exists to form the basis of a comparison.

Pains, solutions, and limitations

We identified 15 types of problems (pains) around doctoral employability training across all programs within the Australian doctoral education system. We further summarized them into three main groups and associated solutions ( and ).

Diverse disciplinary cultures had an impact on how employers and candidates themselves perceive skills and their implementation. For example, Pitt (Citation2012) demonstrated that industry leaders from different disciplines and sectors hardly ever agree on what counts as important skills. Doctoral candidates’ perceptions about the importance of different skills were also influenced by their areas of study (Jackson & Michelson, Citation2016). Further, skills essential for one discipline/industry did not necessarily count as essential for another, as observed in Chen et al. (Citation2020). More interestingly, Chen et al. (Citation2020) found that even if employers in two industries used the same term to describe a skill, the same term can entail very different specific requirements.

Our analysis also pointed to candidates’ varying motivations and aspirations as a complicating factor. For example, candidates in creative arts expressed less interest in heading into an academic career (Bendrups, Citation2021; Draper & Harrison, Citation2018), whilst geography (Dufty-Jones, Citation2018) and physics (Choi et al., Citation2012) candidates longed for research careers in academia. Additionally, candidates in business (Elsey, Citation2007) and creative arts (Bendrups, Citation2021) valued the benefit of an increased personal reputation through having their doctorates. By contrast, physics candidates claimed they were motivated by their pure desire for knowledge (Choi et al., Citation2012).

Diverse learning needs were further complicated by candidates’ different nationalities. The reviewed studies widely assumed that PhDs are in ‘crisis’ (Molla & Cuthbert, Citation2019) and doctorates need to find jobs outside of academia. These assumptions did not necessarily apply to Australia’s international doctoral candidates, especially from developing countries where higher education systems are still growing, thereby increasing the need for academic workforce (Molla & Cuthbert, Citation2019).

Another complicating factor was the difference in age and levels of industry experience amongst candidates. The analysis suggested that the average age of all Australian doctoral graduates is about 37 years (Elsey, Citation2007; Molla & Cuthbert, Citation2015; Neumann & Tan, Citation2011). Younger PhDs with little prior industry experience often felt anxious about their career prospects (Dufty-Jones, Citation2018; Neumann & Tan, Citation2011) but many older candidates already had industry work experience before enrolling in their doctoral programs (Bendrups, Citation2021; Pearson et al., Citation2011). Based on the reviewed articles, this factor was often ignored or taken for granted in both research and policy making.

Authors of the reviewed articles expressed concerns about deficiencies in several training modes embedded within Australian doctoral programs. Supervision, skill training, and professional doctorates were all criticized. Our review suggested that implicit learningFootnote2 is pervasive in all programs and clarity was lacking around the needs for training and who was responsible to carry it out. Supervisors are, of course, the primary educator responsible for PhD candidates and a typical assumption is that the conventional supervisor/student relationships will be sufficient, at least, to reproduce the academic workforce. However, the included articles indicated that candidates are ill-informed about academic conventions essential for good performance in academia and that supervisors routinely fail to make academic practices explicit (Cardilini et al., Citation2021; Greer et al., Citation2016; Guerin, Citation2020). For instance, one article we reviewed suggests PhDs having been in casualized teaching positions does not mean they understand the full student lifecycle and how it is managed, yet supervisors seldom initiate talks with PhDs regarding their roles as teachers (Jepsen et al., Citation2012).

Employers in various industries perceived ‘transferrable skills’ differently (Pitt, Citation2012) and it has been noted that skills required by different industries are not necessarily transferrable (Chen et al., Citation2020). Jackson and Michelson (Citation2016) suggested that non-technical skill development during the candidature does not positively influence job attainment. While a more tailored or nuanced approach seems reasonable, Cumming (Citation2010) and Jackson and Michelson (Citation2016) cautioned against drawing too rigid a line between generic and specific skills. What little evidence there is from employers implied that they often remain pretty vague about skills, which led some scholars to criticize the current skill training as too simplistic (Neumann & Tan, Citation2011). Most studies of skills needs were small scale, so getting to grips with the diverse needs of different industries is clearly difficult. However, the use of new machine learning technology had begun to expand the scale of analysis with, for example, research on job ads (Chen et al., Citation2020; Mewburn et al., Citation2018).

Who should be responsible for skills training? Opinions varied widely. Lee et al. (Citation2009) accused universities of a failure of imagination, treating candidates like they will always be academics. Others holding a similar opinion included Manathunga et al. (Citation2009), Platow (Citation2012), Jackson and Michelson (Citation2015), Guerin et al. (Citation2015), and Dufty-Jones (Citation2018). Not surprisingly, doctoral candidates also believed that universities should be responsible for providing good career development support (Valencia-Forrester, Citation2019). In addition, a few reviewed articles (e.g., Coates et al., Citation2020b; Craswell, Citation2007; Molla & Cuthbert, Citation2015; Pitt, Citation2008) thought that employers should take responsibility as well, perhaps by accepting candidates into their internship programs. Specifically, Craswell (Citation2007) argued that academic skills that candidates acquire during their study programs do not transfer to industry workplace settings. Craswell (Citation2007) also specified why over-reliance on doctoral supervisors for career advice is not practical: doctoral supervisors immersed in the academic culture may not have enough knowledge about industry jobs to offer useful career advice. Taking another angle on the argument, Guerin (Citation2020) argued that employers should be told about benefits and values that doctoral graduates can bring into their businesses. Again, there is clearly opportunity to do more comparative research on the outcomes of the various programs at different universities, but at the time of writing, we lack a national body committed to exploring this area of inquiry and consistent ways of keeping data and measuring what matters.

‘Eduscepticism’, or the unwillingness from employers to accept a degree as evidence of skills attainment, seems to be widespread. Valencia-Forrester (Citation2019) noticed how non-academic sectors generally do not understand the value of PhDs. Similarly, Mewburn et al. (Citation2018) illustrated 80% of industry employers not even mentioning ‘PhD’ or ‘doctorate’ in their job postings when the positions required a high level of research skills. Even if candidates had received a considerable amount of industry-related training, employers often experienced trouble believing in the authenticity of the contexts where such training happens (Valencia-Forrester, Citation2019). The combination of eduscepticism and the populist resistance to evidence-based science on real-world issues had led many to believe that degree acquisition is a waste of money and time (Molla & Cuthbert, Citation2019).

Interestingly, in the face of all this doom and gloom, the literature we examined suggested that doctoral graduates tend to have positive employment outcomes outside academia (Dufty-Jones, Citation2018; Elsey, Citation2007; Guerin, Citation2020). However, the perception by candidates that not becoming an academic is a failure was also pervasive in the literature: Dufty-Jones (Citation2018) noticed how candidates became angry every time they were asked to think about work outside academia. Harman (Citation2002), Molla and Cuthbert (Citation2015), Guerin et al. (Citation2015), Dufty-Jones (Citation2018), and Guerin (Citation2020) all suggested that working in non-academic sectors is viewed by graduates as ‘underemployed’ and a ‘fallback’ option, even when they actually may live an objectively better life, at least financially, than those who decide to stay in academia.

Although many Australian universities have implemented industry engagement programs, insufficient funding and unequal access to these programs was a theme in our literature. Humanities, Arts, and Social Science (HASS) candidates did not seem to have the same opportunities as their STEM counterparts to participate, perhaps because research in non-STEM fields was not readily profitable for industry partners (Barnacle et al., Citation2020; Molla & Cuthbert, Citation2015). Even the well-known Cooperative Research Centre (CRC) programs had not made doctoral graduates more employable in industry (Manathunga et al., Citation2009). The other solution to bridging gaps between academia and employers was internship programs, but Valencia-Forrester (Citation2019) highlighted problems here too: first, finding internship placements for candidates across all fields was difficult, especially for those from HASS. Second, initiating internship programs was a highly resource-intensive activity which increased the pressure faced by universities. Third, standards for picking partners had not been developed, and risks for outsourcing training responsibilities to third parties were hard to manage. Therefore, understanding the employer side of the equation will be essential to the success or otherwise of future programs.

Conclusion

This study systematically reviewed 41 peer-reviewed studies on Australian doctoral education published in the past 22 years and sourced additional policy papers, book chapters, and ‘grey literature’ to supplement this analysis. This study identified both the values and challenges of Australian doctoral education for different stakeholders. Initiatives to address challenges and improve doctoral training were identified, along with limitations of proposed solutions. presents the major gaps in Australian doctoral education and actionable steps resulting from our review.

Table 3. Gaps and suggested actions arising from this study.

Our study has two key limitations. The first is also a strength of our review: we only focused on the Australian context to pinpoint the local characteristics of Australian doctorates. Although this review currently relates to Australia, there are lessons for all countries in this analysis because the PhD can be thought of a signature pedagogy (Shulman, Citation2005), which takes similar forms regardless of what country it is in and therefore faces similar complexities around employability. The second limitation is that we only examined studies related to PhD and Professional Doctorates; other higher degree types may have different issues.

Our analysis suggests that changes in doctoral education in Australia have been mostly driven by the policy framework at the very macro level, providing little evidence-based guidance for universities to develop programs that cater for candidates’ diverse learning needs. Our suggestion aligns with perspectives in Manathunga et al. (Citation2009), Lee et al. (Citation2009), and Cumming (Citation2010). Future research might engage with Australian universities’ career departments to learn how they've embedded employability training in PhD programs and assessed these initiatives.

Research into Australian employers’ perceptions of doctoral graduates is scant, with few retrospective self-report studies and a commissioned report by ACOLA (Citation2016). However, considering the issues of recall bias in retrospective self-reports (Bernard et al., Citation1984) and the evolving nature of doctorates, the validity and usefulness of soliciting employers’ degree perceptions may be debatable. Instead, examining the role of a doctorate degree in industry hiring decisions and investigating skills demand within varied industry cultures might be more insightful. Utilizing innovative methods like machine learning could enable a more robust exploration.

There is clear potential for more research on doctoral graduates’ employability. We observed abundant qualitative but scarce quantitative data. Both types are required for compelling arguments and decisions on whether limiting doctorate ‘birth rate’ (Larson et al., Citation2014) is the solution, or if targeted investment in education and employment schemes is the answer.

Our review indicates a lack of consensus on the responsibility for doctoral employability, suggesting a multi-stakeholder approach. Contrary to Platow (Citation2012), this isn't solely a supervisor's task. We align with Borbasi and Emden (Citation2001) and Jackson (Citation2013) – supervisors can help identify candidates’ learning needs and collaborate with professionals to address career learning requirements.

Our review did not find any research on doctoral employability outcomes for our First Peoples, namely, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cohorts. Despite anecdotal claims of favorable employability outcomes for Indigenous candidates, formal studies, as indicated by Locke et al. (Citation2022), are lacking. Hence, we advocate for research into Indigenous doctoral cohorts’ needs and challenges.

It is hoped that our review could enable a more comprehensive understanding of the local characteristics of career support for PhD students in Australia. We conclude that it is also crucial to engage the government and industry employers in the doctoral employability training enterprise. While we accept the fact that scholars can exert little influence on financial expenditure, we call for a deepened dialogue between universities, employers, and the government on these critical issues.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 In our study, we only examined studies related to PhD and Professional Doctorates. Other HDR degrees such as MPhil are not within the scope of this review.

2 Lovitts (Citation2007) defined implicit learning as the process of always guessing the special something one needs to excel as a student. Educators hardly make hidden rules for excellence explicit enough for their students.

Reference list A (reviewed papers)

- Barnacle, R., Cuthbert, D., Schmidt, C., & Batty, C. (2020). HASS PhD graduate careers and knowledge transfer: A conduit for enduring, multi-sector networks. Arts and Humanities in Higher Education, 19(4), 397–418. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474022219870976

- Barnacle, R., & Mewburn, I. (2010). Learning networks and the journey of ‘becoming doctor’. Studies in Higher education, 35(4), 433–444. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070903131214

- Bendrups, D. (2021). What attracts arts industry professionals to undertake practice-based doctorates? Three Australian vignettes. Research in Post-Compulsory Education, 26(3), 353–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/13596748.2021.1920263

- Borbasi, S., & Emden, C. (2001). Is a PhD the best career choice? Nursing employers’ views. Contemporary Nurse, 10(3-4), 187–194. https://doi.org/10.5172/conu.10.3-4.187

- Bosanquet, A., Mantai, L., & Fredericks, V. (2020). Deferred time in the neoliberal university: Experiences of doctoral candidates and early career academics. Teaching in Higher Education, 25(6), 736–749. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2020.1759528

- Cardilini, A. P., Risely, A., & Richardson, M. F. (2021). Supervising the PhD: Identifying common mismatches in expectations between candidate and supervisor to improve research training outcomes. Higher Education Research & Development, 41(3), 613–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2021.1874887

- Chen, L. A., Suominen, H., & Mewburn, I. (2020, December). A machine-learning based model to identify PhD-level skills in job ads. The 18th Annual Workshop of the Australasian Language Technology Association, Melbourne, Australia.

- Choi, S. H. J., Nieminen, T. A., & Townson, P. (2012). Factors influencing international PhD students to study physics in Australia. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 49(3), 309–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2012.703017

- Clements, K., & Si, J. (2019). What do Australian economics PhDs do? Australian Economic Review, 52(1), 134–144. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8462.12311

- Coates, H., Croucher, G., Moore, K., Weerakkody, U., Dollinger, M., Grosemans, I., Bexley, E., & Kelly, P. (2020b). Contemporary perspectives on the Australian doctorate: Framing insights to guide development. Higher Education Research & Development, 39(6), 1122–1139. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1706451

- Coates, H., Croucher, G., Weerakkody, U., Moore, K., Dollinger, M., Kelly, P., Bexley, E., & Grosemans, I. (2020a). An education design architecture for the future Australian doctorate. Higher Education, 79(1), 79–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-00397-1

- Craswell, G. (2007). Deconstructing the skills training debate in doctoral education. Higher Education Research & Development, 26(4), 377–391. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360701658591

- Cumming, J. (2010). Doctoral enterprise: A holistic conception of evolving practices and arrangements. Studies in Higher Education, 35(1), 25–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070902825899

- Draper, P., & Harrison, S. (2018). Beyond a doctorate of musical arts: Experiences of its impacts on professional life. British Journal of Music Education, 35(3), 271–284. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265051718000128

- Dufty-Jones, R. (2018). The career aspirations and expectations of geography doctoral students: Establishing academic subjectivities within a shifting landscape. Geographical Research, 56(2), 126–138. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-5871.12270

- Elsey, B. (2007). After the doctorate? Personal and professional outcomes of the doctoral learning journey. Australian Journal of Adult Learning, 47(3), 379–404. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.147958145784397

- Greer, D. A., Cathcart, A., & Neale, L. (2016). Helping doctoral students teach: Transitioning to early career academia through cognitive apprenticeship. Higher Education Research & Development, 35(4), 712–726. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2015.1137873

- Guerin, C. (2020). Stories of moving on HASS PhD graduates’ motivations and career trajectories inside and beyond academia. Arts and Humanities in Higher Education, 19(3), 304–324. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474022219834448

- Guerin, C., Jayatilaka, A., & Ranasinghe, D. (2015). Why start a higher degree by research? An exploratory factor analysis of motivations to undertake doctoral studies. Higher Education Research & Development, 34(1), 89–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2014.934663

- Harman, G. (2002). Producing PhD graduates in Australia for the knowledge economy. Higher Education Research & Development, 21(2), 179–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360220144097

- Jackson, D. (2013). Completing a PhD by publication: A review of Australian policy and implications for practice. Higher Education Research & Development, 32(3), 355–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2012.692666

- Jackson, D., & Michelson, G. (2015). Factors influencing the employment of Australian PhD graduates. Studies in Higher Education, 40(9), 1660–1678. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2014.899344

- Jackson, D., & Michelson, G. (2016). PhD-educated employees and the development of generic skills. Australian Bulletin of Labour, 42(1), 108–134. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/ielapa.439531603235277

- Jepsen, D. M., Varhegyi, M. M., & Edwards, D. (2012). Academics’ attitudes towards PhD students’ teaching: Preparing research higher degree students for an academic career. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 34(6), 629–645. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2012.727706

- Kiley, M. (2017). Reflections on change in doctoral education: An Australian case study. Studies in Graduate and Postdoctoral Education, 8(2), 78–87. https://doi.org/10.1108/SGPE-D-17-00036

- Lee, A., Brennan, M., & Green, B. (2009). Reimagining doctoral education: Professional doctorates and beyond. Higher Education Research & Development, 28(3), 275–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360902839883

- Manathunga, C., Pitt, R., & Critchley, C. (2009). Graduate attribute development and employment outcomes: Tracking PhD graduates. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 34(1), 91–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930801955945

- McKinstry, C., Gustafsson, L., Brown, T., & Poulsen, A. A. (2020). A profile of Australian occupational therapy academic workforce job satisfaction. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 67(6), 581–591. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12683

- Mewburn, I., Grant, W. J., Suominen, H., & Kizimchuk, S. (2018). A machine learning analysis of the non-academic employment opportunities for Ph.D. graduates in Australia. Higher Education Policy, 33(4), 799–813. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41307-018-0098-4

- Molla, T., & Cuthbert, D. (2015). The issue of research graduate employability in Australia: An analysis of the policy framing (1999–2013). The Australian Educational Researcher, 42(2), 237–256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-015-0171-6

- Molla, T., & Cuthbert, D. (2019). Calibrating the PhD for Industry 4.0: Global concerns, national agendas and Australian institutional responses. Policy Reviews in Higher Education, 3(2), 167–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322969.2019.1637772

- Mowbray, S., & Halse, C. (2010). The purpose of the PhD: Theorising the skills acquired by students. Higher Education Research & Development, 29(6), 653–664. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2010.487199

- Neumann, R., Kiley, M., & Mullins, G. (2008). Australian doctoral graduates: Where are they going. Quality in postgraduate research: Research education in the new global environment (pp. 84–89).

- Neumann, R., & Tan, K. K. (2011). From PhD to initial employment: The doctorate in a knowledge economy. Studies in Higher Education, 36(5), 601–614. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2011.594596

- Pearson, M., Cumming, J., Evans, T., Macauley, P., & Ryland, K. (2011). How shall we know them? Capturing the diversity of difference in Australian doctoral candidates and their experiences. Studies in Higher Education, 36(5), 527–542. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2011.594591

- Pitt, R. (2008, April). The PhD in the global knowledge economy: Hypothesising beyond employability. 2008 Quality in Postgraduate Research Conference: Research Education in the New Global Environment, Adelaide, Australia.

- Pitt, R. (2012). Australian employers’ expectations and perceptions of PhD graduates in the workplace. 2012 Quality in Postgraduate Research Conference: Narratives of Transition: Perspectives of Research Leaders, Educators & Postgraduates, Adelaide, Australia.

- Pitt, R., & Mewburn, I. (2016). Academic superheroes? A critical analysis of academic job descriptions. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 38(1), 88–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2015.1126896

- Platow, M. J. (2012). PhD experience and subsequent outcomes: A look at self-perceptions of acquired graduate attributes and supervisor support. Studies in Higher Education, 37(1), 103–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2010.501104

- Valencia-Forrester, F. (2019). Internships and the PhD: Is this the future direction of work-integrated learning in Australia? International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning, 20(4), 389–400.

- Wallace, M., Byrne, C., Vocino, A., Sloan, T., Pervan, S. J., & Blackman, D. (2015). A decade of change in Australia’s DBA landscape. Education + Training, 57(1), 31–47. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-07-2013-0096

Reference list B (papers used for methods and discussion)

- ACOLA. (2012). Career support for researchers: understanding needs and developing a best practice approach. https://acola.org/research-workforce-strategy.

- ACOLA. (2016). Securing Australia’s future: Review of Australia’s research training system. https://acola.org.au/wp/PDF/SAF13/SAF1320RTS20report.pdf.

- Astore, M. (2022). Australia spent a million dollars training me – And now I’m leaving. https://www.smh.com.au/education/australia-has-spent-a-million-dollars-training-me-and-now-i-m-leaving-20220419-p5aelz.html.

- Australian Government Department of Education and Department of Industry. (2014). Boosting the commercial returns from research. https://www.dese.gov.au/higher-education-publications/resources/discussion-paper-boosting-commercial-returns-research.

- CBCS (Commonwealth Bureau of Census and Statistics). (1952). University statistics: Part 2. Degrees conferred, universities 1947 to 1952. Commonwealth of Australia.

- Bernard, H. R., Killworth, P., Kronenfeld, D., & Sailer, L. (1984). The problem of informant accuracy: The validity of retrospective data. Annual Review of Anthropology, 13(1), 495–517. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.an.13.100184.002431

- Evidence for Policy and Practice Information Centre (EPPI-Centre). (2022). Guideline tools for keywording and data extraction. https://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Default.aspx?tabid=184#Guidelines.

- Hodgson, D., Watts, L., Cordoba, P. S., & Nipperess, S. (2021). Social work doctoral education in Australia: The case for further development. Australian Social Work, 74(1), 96–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2020.1786139

- Kemp, D. (1999). Knowledge and innovation: A policy statement on research and research training. Commonwealth of Australia.

- Larson, R. C., Ghaffarzadegan, N., & Xue, Y. (2014). Too many PhD graduates or too few academic job openings: The basic reproductive number R0 in academia. Systems research and behavioral science, 31(6), 745–750. https://doi.org/10.1002/sres.2210

- Locke, M., Trudgett, M., & Page, S. (2022). Beyond the doctorate: Indigenous early career research trajectories. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 51(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.55146/ajie.2022.13

- Lovitts, B. E. (2007). Making the implicit explicit: Creating performance expectations for the dissertation. Stylus Publishing.

- Marginson, S., & Considine, M. (2000). The enterprise university: Power, governance and reinvention in Australia. Cambridge University Press.

- McCarthy, P. X., & Wienk, M. (2019). Advancing Australia’s knowledge economy: Who are the top PhD employers? https://www.voced.edu.au/content/ngv:84171.

- OECD. (2019). Education at a glance. https://doi.org/10.1787/f8d7880d-en.

- Quality Indicators for Learning and Teaching (QILT). (2021). Graduate outcomes survey. https://www.qilt.edu.au/surveys/graduate-outcomes-survey-(gos).

- Sharmini, S., & Spronken-Smith, R. (2020). The PhD – Is it out of alignment? Higher Education Research & Development, 39(4), 821–833. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1693514

- Shulman, L. S. (2005). Signature pedagogies in the professions. Daedalus, 134(3), 52–59. https://doi.org/10.1162/0011526054622015

- Spina, N., Smithers, K., Harris, J., & Mewburn, I. (2022). Back to zero? Precarious employment in academia amongst ‘older’ early career researchers, a life-course approach. British Journal of sociology of Education, 43(4), 534–549. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2022.2057925

- The Allen Consulting Group. (2010). Employer demand for researchers in Australia. https://www.academia.edu/30071655/Employer_Demand_for_Researchers_in_Australia.

- Thomson, P. (2016). Educational leadership and Pierre Bourdieu. Routledge.

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O'Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

- Vitae. (2013). What do researchers do? https://www.vitae.ac.uk/impact-and-evaluation/what-do-researchers-do.

- Whittemore, R., & Knafl, K. (2005). The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52(5), 546–553. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x