ABSTRACT

Psychological studies on international research students’ resilience to mental distress have attracted much scholarly attention. Yet, sociological inquiries into resilience to ‘invisible’ pressures such as power imbalances remain limited. Drawing insights from Bourdieu’s relational sociology, we recast the psychology of resilience to adversities into a sociology of resilience to symbolic violence. To delve into the latter, we surveyed 220 Chinese international Higher Degree by Research (HDR) students across Australian universities using a self-designed instrument and analysed the data through Multiple Correspondence Analysis. Findings revealed that Chinese international HDR students were drawn into a space of forces fraught with the symbolic violence of supervisor authority, English hegemony, and neoliberalism; yet, simultaneously, they ventured into a space of struggles with such forms of symbolic violence by virtue of their agency and reflexivity as well as peer and supervisor empowerment. Such resilience practice was complicated by their capital portfolio and habitual dispositions, which in turn, contributed differently to their perceptions of symbolic violence and resilience to it. We thereby offer diverse stakeholders strategies in building resilience for (Chinese) international research students within and beyond Australia.

Introduction

With the continuing internationalisation of higher education, many universities worldwide strategically recruit research students from overseas. Concomitant with the prominence of international research students on numerous campuses across the globe are the concerns regarding the wellbeing of this student cohort and the disturbing evidence about the degree of their mental distress (Jackman et al., Citation2021). These disturbing circumstances are often attributed to a range of psychological and academic challenges (Jackman et al., Citation2021; Woolston, Citation2019). The documented challenges include, but are not limited to, inadequate academic English writing proficiency, high academic demands, heavy academic workloads, tense relationships with supervisors, financial concerns and hardships, inability to achieve work-life balance, and uncertainty of career prospects. These challenges may lead to a higher level of isolation, discrimination, depression, and suicidal tendencies than those concerns identified in the general student population (Jackman et al., Citation2021). While this body of literature has contributed to knowledge about the adversities encountered by international research students, that literature is underpinned by a deficit discourse which portrays those students as vulnerable and passive victims, overlooking their capacities to achieve success despite significant challenges.

By contrast, resilience research in the context of migration has emerged as a positive tool to examine how people on the move transform vulnerabilities into opportunities even in precarious situations (Mu & Hu, Citation2016). In the context of international student mobility, resilience research has revolved around improved mental health, as well as the successful transition and adjustment to university life (Brewer et al., Citation2019; Pidgeon et al., Citation2014; Sabouripour & Roslan, Citation2015). While most of that research focuses on undergraduate students, empirical-based resilience study on research students remains rare. Our paper contributes in this regard by exploring how Chinese international research students in Australia engage with resilience to come to grips with the challenges they experience during their research journey. In this paper, ‘Chinese international research students’ refer to those with Chinese citizenship instead of those with a Chinese heritage in diasporic contexts.

The resilience research reported in the current paper quantitatively surveyed 220 Chinese international Higher Degree by ResearchFootnote1 (HDR) students, the most prominent international HDR student body on Australian university campuses, accounting for approximately 14.5% of the overall Australian HDR students community (DESE, Citation2015). Before proceeding to our empirical study, we first address a key problematic of resilience research, that is, ‘resilience to what?’. This is followed by a theoretical reframing of the dominant psychological school of resilience through Bourdieu’s sociology. After detailing the methodological rationale of the study, we discuss the findings from the survey data through Multiple Correspondence Analysis – an exploratory quantitative methodology heavily used by Bourdieu while currently underutilised in sociological inquiries. Herein lies a methodological contribution of our paper: we vivify a useful quantitative model that remains moribund in Bourdieusian sociology of education. We conclude the paper by offering some practical resilience strategies for relevant stakeholders.

Literature review

Resilience denotes an empowering process of positive response to adversities that would otherwise undermine wellbeing. Resilience research concerning international research students is still in its infancy. Within this limited body of literature, Casey et al. (Citation2022) conducted a mixed-methods study, noting that international research students studying in the United Kingdom have significantly lower wellbeing and resilience levels in comparison to the general population. Yet the authors did not address the problematic of ‘resilience to what?’. By contrast, Singh (Citation2021) interviewed international research students in Malaysia, targeting at their resilience to academic obstacles such as language barriers, academic writing, and the application of new software and equipment. The study revealed institutional and peer support as the underpinnings of resilience to these academic obstacles. In a reflective piece by a British-Indian international doctoral student in New Zealand, the free counselling services provided by the university were acknowledged as a nurturing factor for resilience to isolation and lack of connectivity in a foreign country (Dencer-Brown, Citation2020).

The small body of studies reviewed above is laudable not merely for providing preliminary evidence on institutional and social support in building resilience with international research students, but also for shifting the research focus from the challenges faced by these students to their resilient responses to academic and social obstacles. Informed by this form of research, our study moved the problematic of ‘resilience to what?’ one step further by addressing resilience to structural constraints – social forces that are implicit and hence ‘take the form of a more effective, and in this sense more brutal, means of oppression’ (Bourdieu & Eagleton, Citation1992, p. 115). Our point of departure is twofold. First, due at least in part to their invisible nature, structural constraints have been rarely present on the radar of extant resilience research. We aim to address this knowledge void in our paper. Second and more importantly, it would be difficult for resilience research to achieve a further breakthrough without bringing to its agenda resilience to structural constraints. For while it is morally justifiable to support individuals in becoming strong(er) when faced with adversities, a resilience programme is palliative in nature if it does not address and redress the root causes behind adversities. Our paper makes an attempt to grapple with the (more) difficult problematic – resilience to structural constraints.

In sociological terms, social forces and structural constraints can be termed as symbolic violence – violence that is ‘softened and disguised’ and conceals ‘domination beneath the veil of an enchanted relation’ (Bourdieu, Citation1991, p. 24). Before taking a deep dive into our empirical foray into how Chinese international HDR students in Australia engage in resilience to symbolic violence, we return to the question of ‘resilience to what?’, notably, resilience to what forms of symbolic violence. Our focus here is on three forms of symbolic violence prevalent and persistent in the HDR space, namely supervisor authority, English hegemony, and neoliberalism.

The HDR space is often fraught with the symbolic violence of supervisor authority. Some supervisors tend to enforce frameworks originated in the West on international research students from a non-Western background (Manathunga, Citation2007). In the face of supervisor authority, international research students may assume an academic subaltern status (Kim, Citation2012). Such power imbalances can jeopardise their intellectual independence during their research candidature, impeding their academic development and achievement (Tsotetsi, Citation2020). Supervisor domination can be grounded on symbolic violence beyond student-supervisor power imbalances, extending to something larger, for example, neoliberalism. The neoliberal logics of standardisation, productivity, and performativity in HDR education inadvertently lead to supervisors’ excessive control over students’ research (Deuchar, Citation2008) and heightened pressure to produce research publications within tight timelines (Huang, Citation2021; Manathunga, Citation2019). Another form of symbolic violence – English hegemony – persists in HDR education in Anglophone universities, which, in turn, can prompt tensions and feelings of inferiority amongst non-native English-speaking HDR students (Ma, Citation2020; Sato & Hodge, Citation2009). Yet despite significant linguistic barriers and the attendant academic challenges, international research students rarely questioned the legitimacy of using English. In these cases, supervisor authority, neoliberalism, and English hegemony can be viewed as symbolic violence because it is ‘unrecognised as such, chosen as much as undergone’, and misrecognised as legitimate (Bourdieu, Citation1990, p. 127).

Collectively, the aforementioned studies reveal the symbolic violence of supervisory authority, neoliberalism, and English hegemony faced by international research students. These forms of symbolic domination are not easy to resist as symbolic violence is ‘something you absorb like air, something you don’t feel pressured by; it is everywhere and nowhere, and to escape from that is very difficult’ (Bourdieu & Eagleton, Citation1992, p. 115). Yet this does not necessarily lead to determinism that locks international research students into symbolic violence once and for all. To force symbolic violence to retreat, resilience may work as an important ‘tool’. Accordingly, our study utilised Bourdieu’s thinking tools to re-examine and unearth the sociological mechanisms underlying the resilience building of Chinese international HDR students in Australia. Specifically, we ask: How do these students engage in resilience to the symbolic violence of English hegemony, pedagogic authority, neoliberalism?

Theoretical framework: sociologising resilience with Bourdieu

Since the 1970s, psychological studies of resilience have explicated why some individuals are able to withstand or even thrive throughout their lives despite a variety of difficulties, ranging from daily inconveniences to major life challenges or traumatic events (Luthar et al., Citation2006; Masten et al., Citation2004; Rutter, Citation1993; Ungar, Citation2004). Five decades of psychological research on resilience have produced insightful understandings about successful recovery from, coping with, and adaptation to adversities. Paradoxically, adversities can endure for longer periods of time when human agents better adapt to them (Mu, Citation2021). In response to such paradox, an emerging body of Bourdieu-informed sociological research on resilience (Bottrell, Citation2009a, Citation2009b; Mu, Citation2021, Citation2022) has explored the structural problems behind problematic situations. Psychology of resilience often responds to the latter while ignoring the former. Bourdieu-informed sociology of resilience differs by taking into account ‘the structural roots of social inequalities systemically created and reproduced’ (Mu, Citation2021, p. 18). This approach can reveal, to some degree, the structural constraints and prompt in-depth thinking on social systems, norms, and structures that are often taken for granted.

In this study, we purposefully draw from Bourdieu’s logic of practice to frame the resilience practice of Chinese international HDR students in Australia. Although Bourdieu’s model was mainly developed through empirical work in France and the then French colony of Algeria, that model is not bound by context. Essentially, the model was not designed for a particular context but rather crafted as an epistemological tool that is abstract enough to apply to any differentiating social space of forces and struggles. Its applicability beyond the original context of production has productively enabled a range of scholarship on adopting and adapting Bourdieu’s model to different national contexts (Wacquant, Citation2013), on transnationalising Bourdieu’s field (Schmidt-Wellenburg & Bernhard, Citation2020) and habitus (Stahl et al., Citation2023), and on researching Chinese education (Shi & Li, Citation2019). While the explanatory power of Bourdieu’s model across contexts has been evidenced by a rich body of literature, we do not assume its appropriateness without question, but instead adopt it with epistemological vigilance. Such vigilance is diametrically different from what Mu and Dooley (Citation2023, p. 192) would term a ‘postcolonial guilt’ that worries – with good intention – about imposing ‘mainstream’ Western models on ‘peripheral’ research communities. Rather, our epistemological approach recognises the power shifts between the Western and the other(ed). In this vein, our use of Bourdieu in theorising the experiences of Chinese international HDR students in Australia was a purposeful selection rather than a form of ontological complicity with Bourdieu’s symbolic power. As we intend to understand how Chinese international HDR students engage in resilience to the symbolic violence of supervisory authority, neoliberalism, and English hegemony in Australian universities, Bourdieu’s theoretical framework is valuable in illuminating underlying structures or systemic factors. This provides a new lens for us to recognise how Chinese HDR students withstand within a differentiating social space of symbolic forces and struggles. Accordingly, we have adopted the concepts of Bourdieu’s theoretical toolkit as fit for purpose for investigating the research question and analysing the findings. As will be seen, the use of Bourdieu has helped make sense of, and elucidate, the positions and position-takings of Chinese international HDR students in Australia who are usually silenced and/or subsumed across the neo-liberal, English-dominant academy.

Bourdieu’s logic of practice consists of three main ‘thinking tools’ (Citation1990), namely capital, habitus, and field. According to Bourdieu and Wacquant (Citation1992), field can be understood as a social space that functions by implicit rules, which in turn are interpreted and practiced by social agents; habitus functions as a structured schema that internalises the rules of the field and a structuring mechanism that generates and modifies social practice within the limits set by the field; and capital refers to field-specific resources occupied by social agents which take time to accrue and manifest in different forms, such as economic capital, cultural capital, or social capital.

Working through a Bourdieusian lens, we retheorise resilience as a form of social practice unfolding: whereby the dispositions of Chinese international HDR students in Australia (habitus), the resources and social positions that they take (capital), and the politics and principles of various social spaces where they work and live (field) all collectively shape the mechanisms of resilience to symbolic violence (practice). It is arguable that the social positions of Chinese international HDR students defined by their volume and configuration of capital, and their position-takings driven by their habitus, may come to shape their practice of resilience to symbolic violence in the HDR space as a field. We now draw from this theoretical stance to put Bourdieu to work through quantitatively inquiring the ways in which our Chinese international HDR student participants engage with resilience to symbolic violence.

Research design

This quantitative study is part of a multi-year sequential mixed methods project on the resilience practice of Chinese international HDR students in Australia (ethics approval number 2000000248). For this particular study, a survey was developed based on the interview findings from the qualitative phase of the larger project, a literature review of resilience research that is concerned with the experience of Chinese international research students, and Bourdieu’s sociology. The survey was provided in Mandarin. An online survey link created by Questionnaire Star was distributed to the prospective respondents via email and a Chinese social app WeChat, where numerous Chinese postgraduate groups convene. Following a two-week snowball sampling distribution, 220 Chinese international students who were studying for or have recently graduated (within 12 months) with a research degree from an Australian university at the time of data collection completed the survey.

The survey comprised three main components, namely, socio-educational backgrounds, symbolic violence, and resilience to symbolic violence. The first component, the social-educational dynamics of Chinese international HDR students, was measured by 23 demographic survey items in relation to gender, year of birth, marital status, educational and research backgrounds, supervisory backgrounds, and family backgrounds. In Bourdieusian terms, these items can measure systems of dispositions (habitus) and positional dis/advantage (capital) of Chinese international HDR students. demonstrates the demographic information of the survey respondents. More than half (n = 125, 56.8%) of the survey respondents were female. The majority of the respondents (n = 188, 85.5%) were born between 1989 and 1998 and were in their 20s and 30s. The respondents came from 25 Australian universities, with 63.2% (n = 139) from Australia’s leading research-intensive Group of Eight (Go8) universities. Aside from these sociodemographic features, the respondents demonstrated a diverse range of educational and research backgrounds; their supervisors’ backgrounds and family backgrounds also varied.

Table 1. Demographic information of survey respondents.

The second component, symbolic violence, has three constructs, namely, supervisor authority, English hegemony, and neoliberal constraints – three persistent and prevalent forms of symbolic violence in the HDR space – as suggested in our foregoing exposition. Each of the three forms of symbolic violence was measured by 6 items, gauging the degree of participants’ consecration of the symbolic power of their supervisor/s and English language as well as the extent of imposition of neoliberal forces such as standardised milestone management, the urgency to publish, and peer competition in research performance.

The third component, resilience to symbolic violence, was gauged by 12 survey items, the design of which was informed by extant literature. First, Bourdieu-informed resilience research has highlighted the role of agency and reflexivity of individuals grappling with symbolic violence, such as academics working in neoliberal universities (Yin & Mu, Citation2022). These individuals intended to transform a problematic system instead of merely adapting to that system. Agency and reflexivity of Chinese international research students also appear to be key to resilience to symbolic violence (Xing et al., Citation2022a, Citation2022b, Citation2023). Second, Chinese international research students’ strategies of resilience to symbolic violence may not always develop from within but can be nurtured by empowering others, such as peers and supervisors (Xing et al., Citation2022a, Citation2022b, Citation2023). Accordingly, the survey items associated with resilience to symbolic violence were loaded on two constructs, namely, supervisor and peer empowerment, and student agency and reflexivity. Each construct was measured through 6 items. All items of the second and the third components were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 ‘strongly agree’ to 5 ‘strongly disagree’.

With the collected survey data, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted respectively on the three-factor measurement model for symbolic violence consisting of supervisory authority, English hegemony, and neoliberalism (CFI = .95, TLI = .91, NFI = .91, and RMSEA = .06) and the two-factor measurement model for resilience to symbolic violence consisting of supervisor and peer support as well as student agency and reflexivity (CFI = .92, TLI = .90, NFI = .88, and RMSEA = .08). As suggested by the cited model fit indices, both measurement models have shown a reasonably good fit. Cronbach’s alpha of the five constructs ranged in value between .74 and .91, demonstrating a reasonably high level of internal consistency reliability of the survey instrument. In our further analyses, each factor was treated as a variable with a composite score. In total, there are five such variables that were applied to Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA) detailed in the ensuing section.

Research findings

To unveil the patterns behind the resilience practice of Chinese international HDR students, we have recourse to Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA) – a statistical technique and an exploratory quantitative methodology for analysing groupings of social categories (Hjellbrekke, Citation2018; Le Roux & Rouanet, Citation2010). Different from most inferential statistical models that assume independence of variance, MCA takes into account the interdependence among the variables included in the analysis (Blasius & Thiessen, Citation2001). When exploring the interdependency of variables, MCA tends to pull together socially similar participants and their characteristics, while pushing away socially dissimilar participants/characteristics. In this vein, MCA is geometric modelling that helps construct a space of classification. As such, the principles of MCA are coherent with Bourdieu’s relational thinking, seen in his extensive use of this methodology throughout his research programme (e.g., Bourdieu, Citation1984, Citation1988, Citation1996).

In this study, MCA was performed in two steps. The first was set to construct a space of symbolic forces and the struggles against them taken by Chinese international HDR students through resilience. This was followed by the second step to help make sense of how Chinese international HDR students navigate the space of structural forces and strategise their struggles against those forces. In the first step of MCA – constructing a space of symbolic forces and struggles, variables measuring symbolic violence and resilience to symbolic violence were included as active variables, variables that contribute to space construction (Hjellbrekke, Citation2018). To recall, symbolic violence was measured by three variables including ‘supervisor authority’, ‘English hegemony’, and ‘neoliberal constraints’; and resilience to symbolic violence was gauged by two variables including ‘supervisor and peer empowerment’ and ‘student agency and reflexivity’. Bourdieu (Citation2020) construes field simultaneously as a social space of forces and struggles. The space construction through MCA was thus enlightened by ‘the field of forces’ versus ‘the field of struggles’. Regarding the former, Bourdieu explains that social space is a structure of objective relations of forces. Accordingly, we consider a field of forces fraught with symbolic violence into which Chinese international HDR students were drawn. Regarding the latter, Bourdieu expounds that social agents seek to safeguard or improve their position in a field of forces. Accordingly, we consider Chinese international HDR students as agents venturing into a field of struggles to take issue with the field of forces through a sociological practice of resilience to symbolic violence.

For the purpose of MCA, the five active variables measured as continuous variables need to be transformed into categorical variables. Taking ‘supervisor authority’ as an example, it was transformed into a categorical variable with four categories, namely, ‘Authority 1’ (the bottom 25%), ‘Authority 2’ (25%–50%), ‘Authority 3’ (50%–75%), and ‘Authority 4’ (the top 25%). ‘Authority 1’ represents the weakest supervisor authority inflicted on the respondents, while on the opposite, ‘Authority 4’ symbolises the strongest supervisor authority encountered by the respondents. In this way, each active variable contains four categories. In total, the five active variables generate 20 active categories (5 × 4). Each category on average contributes 5% to space construction (1/20 = .05). As a rule of thumb, categories with a contribution higher than average (≥ 5%) to space construction are called explicable categories, which are considered in further analysis (Hjellbrekke, Citation2018).

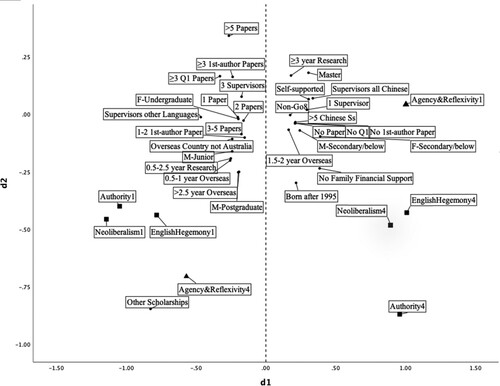

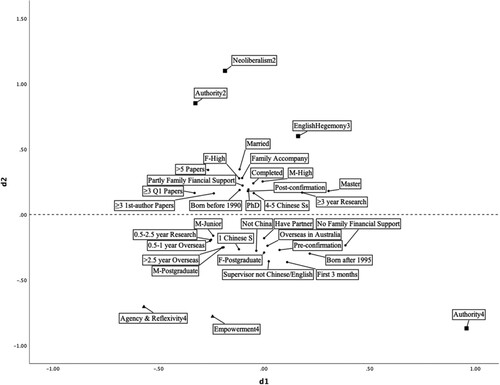

Following the first step of MCA that constructed the space of symbolic forces and struggles, the second step delved into the relations between respondents’ socio-educational characteristics and their position-takings in the space thus constructed. In Bourdieusian terms, capitals and habitus navigate respondents to certain positions of the space constructed by active variables. In total, there are 23 socio-educational variables containing 85 categories altogether (see ). These variables were projected onto the MCA plot as supplementary variables, referring to those with no contribution to the construction of the space but can help interpret position-takings within the space constructed by active variables (Hjellbrekke, Citation2018). Of all the supplementary variables, participants’ disciplinary backgrounds did not appear on the MCA maps; hence they were deemed to have little if any explanatory power in the current study. Of all the possible dimensions initially generated by MCA, two dimensions were retained, accounting for 73.7% of all variance in the data. maps the meaningful/interpretable categories of the first dimension (horizontal) while outlines the second dimension (vertical).

Dimension 1: a seemingly ‘zero-sum’ game

As shown in , the space of forces and struggles was split into two sub-spaces on the first dimension. The left half of the plot represents a space of weak symbolic violence (Neoliberalism1, Authority1, EnglishHegemony1) in correspondence to a strong sense of agency and reflexivity (Agency & Reflexivity 4); while the right half of the plot shows an opposite tendency. There seems to exist a ‘zero-sum’ between symbolic violence and resilience to it. Yet further analysis suggests that the dialectics between the two cannot be simplistically reduced to a zero-sum game. When supplementary variables were added to the MCA plot, complicated but interpretable patterns of sociology of resilience to symbolic violence emerged.

The left half of the space is populated with the most socio-educationally advantaged respondents. First, these respondents had some overseas learning and research experience prior to their most recent HDR study in Australia. Some had studied abroad for half to one year; some, more than 2.5 years. Notwithstanding, some had already accumulated 0.5 to 2.5 years' research experience. Such experience was likely to be obtained in countries other than Australia. These respondents were also likely to have three supervisors coming from diverse linguistic backgrounds. In addition, they had established a track record of academic publishing in terms of both quantity and quality during their HDR study in Australia, ranging from a total number of one to five papers including papers published in top journals of their study area and those published as first author. Second, the parents of the respondents tended to have high educational qualifications such as an undergraduate or postgraduate degree.

In Bourdieusian terms, respondents residing in the left half of the space tended to obtain academic habitus and substantial capital sourcing from the higher education field and the family field. These owe to their upbringing by educated parents as well as their previous and current overseas learning and research experience including academic publishing and research training by a supervisory team with multilingual capacity. When their habitus and capital encounter a field of which they are the products, a sense of goodness-of-fit may be produced for these respondents. They may find themselves as ‘fish in water’ and may not ‘feel the weight of the water’ (Wacquant, Citation1989, p. 43). Indeed, HDR students as such only reported a marginal sense of coercion by the symbolic violence of English hegemony, supervisor authority, and neoliberal constraints. While the goodness-of-fit between habitus, capital, and field would generate a sense of taking ‘the world about itself for granted’ (Wacquant, Citation1989, p. 43), this is not the case for the respondents here. Instead, they were associated with a strong sense of agency and reflexivity. Putting together, the respondents residing in the left half of the space tend to engage with a sociological practice of resilience to symbolic violence in two related ways. On the one hand, their capital portfolio and habitual dispositions may have enabled their adaptation to the HDR space. On the other hand, their agency and reflexivity may have promoted them to constantly question the usually unquestioned symbolic violence and break loose from it.

In contrast to the left half of the space, the right half is occupied by socio-educationally disadvantaged respondents. These respondents include those having had 1.5–2 years of overseas learning and research experience before their HDR study in Australia, recently awarded a Master’s degree, or studying in non-Group of Eight Australian universities at the time of the survey. They were likely to have no publications as first author or in leading journals of their study area, or no publications at all. Some respondents had only one supervisor; some had supervisors who came from a Chinese-speaking background and/or supervised more than five Chinese students. Respondents also include those who were self-supported to study and those whose parents had an education qualification at a secondary school level or below and could not financially support their HDR study in Australia.

In Bourdieusian terms, the right half of the space hosted respondents who could access or accrue a limited amount of cultural, symbolic, and economic capital except for those self-funded students. This is also a space fraught with strong symbolic violence; namely, that of English hegemony, neoliberal constraints, and supervisor authority. For Bourdieu, symbolic violence takes effect through constraint by consent, ‘exerted not in the pure logic of knowing consciousness but through the schemes of perception, appreciation, and action that are constitutive of habitus’ (Bourdieu, Citation2001, p. 37). This appears the case for the respondents here, who demonstrated limited agency and reflexivity when faced with symbolic domination.

Dimension 2: a double-edged sword of supervisor power

On the second dimension (the vertical dimension), the MCA plot was also divided into two spaces (see ). The upper half of the space is marked with moderate symbolic violence (Neoliberalism2, Authority2, and EnglishHegemony3), but none of the categories associated with resilience to symbolic violence landed on this space, and further investigation is required to make sense of the latter. The bottom half of the space is characterised by strong resilience to symbolic violence (Agency&Reflexivity4 and Empowerment4), while the symbolic violence of supervisor authority was also strong (Authority4).

In the bottom half of the space, respondents received the strongest degree of supervisor and peer empowerment and demonstrated the strongest degree of agency and reflexivity while exposed to the strongest degree of supervisor authority. The respondents’ characteristics are as follows. First, their family backgrounds varied. Some were raised up by well-educated parents with a postgraduate degree; some had parents with a modest educational qualification, e.g., a mother with a junior high school certificate; others came from a family unable to financially support their study at all. Second, they were relatively ‘rich’ in cultural capital before they commenced their HDR journey in Australia. Some of them had completed their undergraduate education abroad and had overseas experience in Australia for half to one year or more than 2.5 years. Some already had research experience of half to 2.5 years. Interestingly, they tended to be at an early stage of their current HDR journey. Some were in the first three months of their candidature; others were yet to have their HDR candidacy confirmed. Their supervisors might have had just one Chinese student and were not native speakers of either Chinese or English. This indicates that those ‘newcomers’ rich in cultural capital might have received ‘special care’ from supervisors and peers; at the same time, they also reportedly experienced strong supervisor authority. By implication, HDR supervision can be a craft of simultaneous empowerment and authority, which are not necessarily two opposing extremes on a spectrum. When working with high-calibre, capital-rich candidates early in their HDR journey, supervisors can balance wielding power and granting power, which in turn, may nurture student agency and reflexivity in the face of symbolic violence.

Discussion and conclusion

This quantitative study unveils the underlying social mechanisms behind the sociological practice of resilience to symbolic violence that involves Chinese international HDR students in Australia. Our findings suggest that these students are drawn into a space of forces fraught with various degrees of symbolic violence and simultaneously venture into a space of struggles with the symbolic violence to which they are exposed. At first glance, there seems to be a ‘zero-sum’ exercise where strong symbolic violence limits resilience and strong resilience forces symbolic violence to retreat. However, this is an undertaking complicated by Chinese international HDR students’ prior overseas learning and research experience, current research experience including candidature stages, academic publishing, and HDR supervision. It is also shaped by their family backgrounds such as parental educational qualifications and financial support, all of which contribute differently to these students’ capital portfolio and habitual dispositions, and which in turn, contribute differently to their perceptions of symbolic violence and resilience to it.

In brief, capital-rich participants with an academic habitus that matches the higher education field may find themselves ‘fish in water’ without noticing much symbolic violence in that field. This does not necessarily mean that they have been fully enculturated into, and over-adaptive to, that field, hence taking that field for granted. Instead, they often demonstrate a high level of agency and reflexivity to take issue with the symbolic violence in the field. By contrast, those respondents with less capital tend to be exposed to notable symbolic violence while experiencing limited supervisor and peer empowerment as well as little student agency and reflexivity. Also noteworthy is that HDR supervision is an art of simultaneously capitalising on empowerment and authority, which can nurture resilience to symbolic violence especially at the early stage of the HDR candidature.

We have to acknowledge, however, that the role of peers did not stand out in the sociological patterns of resilience to symbolic violence although our measurement did take into account peer competition and empowerment. Despite this limitation, our findings can offer implications and recommendations to relevant stakeholders that include (Chinese) international research students, research student supervisors and educators, as well as universities, in Australia and beyond. For (Chinese) international research students, it recommends that they enhance their cultural capital in terms of academic literacy in English, track record in research publications, scholarly capacity in project management, and the growth in scholarship under the guidedance of their supervisors. Equally important – as suggested by our findings – are agency and reflexivity in realising both the value and violence of symbolic power. We invite (Chinese) international research students to engage with our findings critically so that they do not unconsciously consecrate supervisors as ‘sage on the stage’ authority figures, English as the legitimate academic language, neoliberal rules as the right order, and hence internalise a sense of submissiveness in the face of those forms of symbolic violence. This is not to suggest a radical cynicism that blatantly rejects the symbolic power of cultural capital, which would otherwise exclude (Chinese) international research students from the higher education field. Instead, we hope that our findings can empower them as reflexive, agentic knowledge workers who understand that power imbalances are not something as given but something that can be contested and changed.

The foregoing suggestions do not call on (Chinese) international research students to shoulder full responsibility in the project of resilience to symbolic violence. The support of supervisors and HDR training practitioners remains critical. We thereby encourage supervisors to reflexively scrutinise their academic authority during HDR supervision. We also encourage supervisors and staff in the higher education sector in general to enable and empower HDR students through a nurturing system for the sake of knowledge production instead of managing HDR students through neoliberalised principles for the sake of productivity. For the Australian government and universities, we think it is time to revisit the ‘English-only’ policy in HDR education. It is not enough to respect the linguistic diversity associated with the international HDR student body but more importantly, it will be productive to incorporate the linguistic repertoire of this student cohort into theses and knowledge production and to build collective capacity in cross-language HDR supervision and education.

In closing, international research students have received little scholarly treatment from the sociology of education and even less attention from resilience research. Our paper has enriched the scholarship concerning this student cohort. Being first-of-its-kind resilience research with Chinese international HDR students from Australian universities, our study extended the psychology of resilience to adversity to sociology of resilience to symbolic violence. The use of MCA contributes to the invigoration of this powerful quantitative exploratory methodology that is in a moribund position in the Bourdieusian sociology of education. Given the focus only on Chinese international HDR students, the sociological resilience practice discovered in this study only amounts to the tip of the iceberg. As such, we conclude this paper with a call to expand the research scope into diverse populations and contexts, such as other international research students or research students in general both within and beyond Australia.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In Australia, the official term of Higher Degree by Research (HDR) denotes research only degrees such as Masters by Research (1.5–2 years full time) and Doctorates (3–4 years full time).

References

- Blasius, J., & Thiessen, V. (2001). Methodological artifacts in measures of political efficacy and trust: A multiple correspondence analysis. Political Analysis, 9(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.pan.a004862

- Bottrell, D. (2009a). Dealing with disadvantage: Resilience and the social capital of young people’s networks. Youth & Society, 40(4), 476–501. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X08327518

- Bottrell, D. (2009b). Understanding ‘marginal’ perspectives: Towards a social theory of resilience. Qualitative Social Work, 8(3), 321–339. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325009337840

- Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A social critique of the judgment of taste (R. Nice, Trans.). Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd.

- Bourdieu, P. (1988). Homo academicus (P. Collier, Trans.). Stanford University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (1990). The logic of practice (R. Nice, Trans.). Polity Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (1991). Language and symbolic power. Polity Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (1996). The state nobility: Elite schools in the field of power (L. C. Clough, Trans.). Polity Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (2001). Masculine domination. Polity Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (2020). Habitus and field: General sociology, volume 2, lectures at the Collège de France (1982-1983) (P. Collier, Trans.). Polity Press.

- Bourdieu, P., & Eagleton, T. (1992). Doxa and common life. New Left Review, 191(1), 111–121.

- Bourdieu, P., & Wacquant, L. J. D. (1992). An invitation to reflexive sociology. University of Chicago press.

- Brewer, M. L., van Kessel, G., Sanderson, B., Naumann, F., Lane, M., Reubenson, A., & Carter, A. (2019). Resilience in higher education students: A scoping review. Higher Education Research & Development, 38(6), 1105–1120. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1626810

- Casey, C., Harvey, O., Taylor, J., Knight, F., & Trenoweth, S. (2022). Exploring the wellbeing and resilience of postgraduate researchers. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 46(2), 850–867. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2021.2018413

- Dencer-Brown, A. M. (2020). From isolation to cross-cultural collaboration: My international PhD journey as tauiwi. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in the South, 4(2), 228–234. https://doi.org/10.36615/sotls.v4i2.142

- DESE. (2015). China infographic 2015. Retrieved May 25, 2021, from https://internationaleducation.gov.au/research/research-snapshots/Documents/China%20Infographic%202015.pdf

- Deuchar, R. (2008). Facilitator, director or critical friend?: Contradiction and congruence in doctoral supervision styles. Teaching in Higher Education, 13(4), 489–500. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510802193905

- Hjellbrekke, J. (2018). Multiple correspondence analysis for the social sciences. Routledge.

- Huang, Y. (2021). Doctoral writing for publication. Higher Education Research and Development, 40(04), 753–766. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1789073

- Jackman, P. C., Jacobs, L., Hawkins, R. M., & Sisson, K. (2021). Mental health and psychological wellbeing in the early stages of doctoral study: A systematic review. European Journal of Higher Education, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568235.2021.1939752

- Kim, J. (2012). The birth of academic subalterns: How do foreign students embody the global hegemony of American universities? Journal of Studies in International Education, 16(5), 455–476. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315311407510

- Le Roux, B., & Rouanet, H. (2010). Multiple correspondence analysis. SAGE.

- Luthar, S. S., Sawyer, J. A., & Brown, P. J. (2006). Conceptual issues in studies of resilience: Past, present, and future research. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1094(1), 105–115. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1376.009

- Ma, L. P. F. (2020). Writing in English as an additional language: Challenges encountered by doctoral students. Higher Education Research and Development, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1809354

- Manathunga, C. (2007). Supervision as mentoring: The role of power and boundary crossing. Studies in Continuing Education, 29(2), 207–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/01580370701424650

- Manathunga, C. (2019). ‘Timescapes’ in doctoral education: The politics of temporal equity in higher education. Higher Education Research & Development, 38(6), 1227–1239. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1629880

- Masten, A. S., Burt, K. B., Roisman, G. I., Obradović, J., Long, J. D., & Tellegen, A. (2004). Resources and resilience in the transition to adulthood: Continuity and change. Development and Psychopathology, 16(4), 1071–1094. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579404040143

- Mu, G. M. (2021). Sociologising resilience through Bourdieu’s field analysis: Misconceptualisation, conceptualisation, and reconceptualisation. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 42(1), 15–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2020.1847634

- Mu, G. M. (2022). Sociologising child and youth resilience with Bourdieu: An Australian perspective (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003218814

- Mu, G. M., & Dooley, K. (2023). Researching Chinese education from within and afar: Enacting Bourdieu’s ‘practical reflexivity’. In G. M. Mu & K. Dooley (Eds.), Recontextualising and recontesting Bourdieu in Chinese education: Habitus, mobility, and language (pp. 185–201). Routledge.

- Mu, G. M., & Hu, Y. (2016). Living with vulnerabilities and opportunities in a migration context Floating children and left-behind children in China. Springer.

- Pidgeon, A. M., Rowe, N. F., Stapleton, P., Magyar, H. B., & Lo, B. C. Y. (2014). Examining characteristics of resilience among university students: An international study. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 02(11), 14–22. https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2014.211003

- Rutter, M. (1993). Resilience: Some conceptual considerations. Journal of Adolescent Health, 14(8), 626–631. https://doi.org/10.1016/1054-139X(93)90196-V

- Sabouripour, F., & Roslan, S. B. (2015). Resilience, optimism and social support among international students. Asian Social Science, 11(15), 159–170. https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v11n15p159

- Sato, T., & Hodge, S. R. (2009). Asian international doctoral students’ experiences at two American universities: Assimilation, accommodation, and resistance. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 2(3), 136–148. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015912

- Schmidt-Wellenburg, C., & Bernhard, S. (Eds.). (2020). Charting transnational fields: Methodology for a political sociology of knowledge. Routledge.

- Shi, Z., & Li, C. (2019). Bourdieu's sociological thinking and educational research in mainland China. In G. M. Mu, K. Dooley, & A. Luke (Eds.), Bourdieu and Chinese education: Inequality, competition, and change (pp. 45–61). Routledge.

- Singh, J. K. N. (2021). Academic resilience among international students: Lived experiences of postgraduate international students in Malaysia. Asia Pacific Education Review, 22(1), 129–138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-020-09657-7

- Stahl, G., Soong, H., Mu, G. M., & Dai, K. (2023). A fish in many waters? Addressing transnational habitus and the reworking of Bourdieu in global contexts. Sociological Research Online, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/13607804231180021

- Tsotetsi, C. (2020). Deconstructing power differentials in the postgraduate supervision process: Mentoring in Ubuntu praxis. Ubuntu: Journal of Conflict and Social Transformation, 9(1), 105. https://doi.org/10.31920/2050-4950/2020/9n1a6

- Ungar, M. (2004). A constructionist discourse on resilience: Multiple contexts, multiple realities among at-risk children and youth. Youth & Society, 35(3), 341–365. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X03257030

- Wacquant, L. J. D. (1989). Towards a reflexive sociology: A workshop with Pierre Bourdieu. Sociological Theory, 7(1), 26–63. https://doi.org/10.2307/202061

- Wacquant, L. J. D. (2013). Symbolic power and group-making: On Pierre Bourdieu’s reframing of class. Journal of Classical Sociology, 13(2), 274–291. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468795X12468737

- Woolston, C. (2019). PhDs: The tortuous truth. Nature, 575(7782), 403–406. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-03459-7

- Xing, C., Mu, G. M., & Henderson, D. (2022a). Problematising English monolingualism in the ‘multicultural’ university: A Bourdieusian study of Chinese international research students in Australia. Journal of Mutilingual and Multicultural Development, https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2022.2026366

- Xing, C., Mu, G. M., & Henderson, D. (2022b). Submission or subversion: Survival and resilience of Chinese international research students in neoliberalised Australian universities. Higher Education, 84(2), 435–450. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-021-00778-5

- Xing, C., Mu, G. M., & Henderson, D. (2023). Power imbalance and power shift between Chinese international research students and their supervisors: Adaptation and resilience. In G. M. Mu & K. Dooley (Eds.), Bourdieu and Sino-foreign higher education: Structures and practices in times of crisis and change (pp. 104–123). Routledge.

- Yin, Y. M., & Mu, G. M. (2022). Thriving in the neoliberal academia without becoming its agent? Sociologising resilience with an early career academic and a mid-career researcher. Higher Education, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00901-0