ABSTRACT

Objectives

The care of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) relies on family caregivers (FCs) who face increasing demands. This study aimed to identify trajectories of depressive symptoms in FCs.

Methods

226 FCs and individuals with AD were followed up for 5 years as a part of the ALSOVA study. Depressive symptoms in FCs were measured with the Beck Depression Inventory from the time of the AD diagnosis to the 5-year follow-up. We compared the trajectory of groups regarding age, education, and sex of both FC distress and AD symptoms.

Results

We identified three trajectories of FC depressive symptoms throughout follow-up: (1) declining (7.5% of FCs), (2) minor (59.7% of FCs), and (3) increased (32.7% of FCs). These groups exhibited differences in demographic variables, FC distress, and individuals with AD neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Conclusions

The present study showed that FC depressive symptoms existed, and one-third of caregivers experienced increasing depressive symptoms over five years.

Clinical implications

Family caregivers’ health should be followed in clinical practice, and those at risk of depression could be recognized early in caregiving.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

In primary dementia care settings, depressive symptoms in family caregivers (FCs) of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) are common (Sallim, Sayampanathan, Cuttilan, & Ho, Citation2015). Studies that focus on depression in family caregivers are often cross-sectional in design (Arai, Kumamoto, Mizuno, & Washio, Citation2014; Arthur, Gitlin, Kairalla, & Mann, Citation2018; Cheng, Lam, & Kwok, Citation2013; Hasewaga et al., Citation2014; Huang, Liao, & Wang, Citation2015; Lee et al., Citation2017; Ownby, Peruyera, Acevedo, Loewenstein, & Sevush, Citation2014; Piercy et al., Citation2013; Sutter et al., Citation2014). Piercy et al. (Citation2013) showed that fewer depressive symptoms were observed in caregivers with more education, more social support networks, less wishful thinking tendencies, more problem-focused coping, and fewer health problems. On the other hand, health problems (Arai et al., Citation2014), female sex (Arai et al., Citation2014), inadequate income (Arai et al., Citation2014), longer hours spent caregiving (Arai et al., Citation2014), co-residing with an individual with AD (Arai et al., Citation2014), and an emotional relationship between the FCs and individual with AD (e.g., daughter vs daughter-in-law; Lee et al., Citation2017) were associated with increased depressive symptoms in caregivers.

In addition, family caregivers’ depression was found to be influenced by individual factors connected with Alzheimer’s disease, including the severity/frequency of behavioral disturbances or neuropsychiatric symptoms (Arthur et al., Citation2018; Hasegawa et al., Citation2014; Huang et al., Citation2015; Lee et al., Citation2017), moderate dementia (Arai et al., Citation2014), and greater dependency in activities of daily living (Hasegawa et al., Citation2014; Lee et al., Citation2017). For instance, Ying, Yap, Gandhi, and Liew (Citation2018) showed that significant predictors of FCs’ depression were: acting as a primary caregiver, caring for a spouse, having a low level of education, and care recipient with severe dementia and behavioral problems.

Moreover, FCs’ depression has been associated with care recipients’ distinct neuropsychiatric symptoms, including sleep problems (Ownby et al., Citation2014), problems in the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) behavior domain (Cheng et al., Citation2013), agitation/aggression, anxiety, nighttime behavior, irritability, and hallucinations (Huang et al., Citation2015). Conversely, Ornstein et al. (Citation2013) found that FCs’ depression was only associated with care recipients’ depression.

The hierarchical model of Sutter et al. (Citation2014) indicated that family dynamics were associated with two variables that reflected the family caregiver’s mental health. Moreover, caregivers tended to assess persons with dementia well-being to be lower than persons with dementia themselves, and this discrepancy has been associated with caregivers’ psychological well-being and health (Schulz et al., Citation2013). A relatively short follow-up study by Simpson and Carter (Citation2013) also indicated that perceived stress and lack of sleep contributed to depression.

A longitudinal study by Ornstein, Gaugler, Zahodne, and Stern (Citation2014) followed persons with AD or Lewy body dementia and their caregivers for up to 6 years. Participants were either community-dwelling or living in nursing homes. They described three main groups with the following trajectories of FCs’ depressive symptoms: (1) a consistently low probability of developing depressive symptoms, which remained stable over time; (2) a high risk of depression, which slightly but steadily increased over time; and (3) a steeper increase in symptoms, which stabilized over time (this small group was not included in the further analyses). There was no difference between groups 1 and 2 in initial persons with dementia cognition, function, behavioral and psychological symptoms in dementia, other medical comorbidities, or the time since diagnosis. The only difference between groups 1 and 2 was the sex of the person with dementia, relationship and the amount of time they spent together. Results indicated that FCs in group 2 with a high risk for depression were more often caregivers to a male individual with dementia and spouses and spent more time with an individual with dementia.

Furthermore, a trend suggested that FCs in the more depressive group were older, less likely to be employed, and lived with the person with dementia in their own home. In the intervention study by Kuo et al. (Citation2017), three relatively stable trajectories of depression symptoms were found during an 18-month follow-up: non-depressed, mildly blue and depressed. Caregivers in the intervention group received telephone consultations, and caregivers in this group had a lower probability of persistent depressive symptoms.

Although FCs depression is widely studied, longitudinal research among dome-dwelling dyads is rare. In previous longitudinal studies, studied populations have been heterogeneous, including individuals with AD and Lewy Body Disease (Ornstein et al., 2103) or Alzheimer’s disease and Vascular dementia (Kuo et al., Citation2017). However, group-level demographics and analysis were not presented, although care recipients were at early stages of illness with relatively mild cognitive impairment (Ornstein et al., Citation2013), similarly to our study. But, in another longitudinal study by Kuo et al. (Citation2017), persons with dementia were already at the baseline at the severe stage of dementia.

These are the rare follow-up studies of caregivers’ depressive symptoms to the best of our knowledge. There is a need for longitudinal studies of depressive symptoms in caregivers caring for community-dwelling persons with AD from the early phase of caregiving.

The present study aimed to identify the trajectories of depressive symptoms in FCs during a five-year follow-up and identify caregiver- and care recipient-related factors that affected these trajectories. During the longitudinal follow-up, starting from the time of the AD diagnosis, it may be possible to detect worsening depressive symptoms over time and recognize those caregivers who would need more support in the clinical setting.

Methods

Participants

This study was performed as part of the prospective ALSOVA study, which was designed to examine the effects of early rehabilitation in individuals with very mild or mild AD and their caregivers (Koivisto et al., Citation2016) and the effects of caregiving on caregivers (Välimäki et al., Citation2016). Individuals with AD and their FCs (dyads) were recruited at an average of five months after the AD diagnosis, from April 2002 to September 2006. Individuals with AD were diagnosed in the memory clinic by a geriatrician or neurologist according to the criteria set by the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (McKhann et al., Citation1984) and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (APA, Citation1994). A study neurologist verified all AD diagnoses. A study nurse and psychologist followed dyads annually. A detailed description of the study design was presented previously (Koivisto et al., Citation2016). Of the initial 236 participants and caregivers included in the ALSOVA follow-up study, ten caregivers changed during the three-year follow-up due to caregiver-related reasons; these FCs were excluded from this study. The number of participant dyads in annual visits were: 226, 188, 158, 122, 77, and 68.

Ethical considerations

The ethical committee of Kuopio University Hospital (original decision no. 64/00) and the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare (THL, Dnro THL/1576/5.05.00/2014) gave favorable opinions for the ALSOVA study (latest updates 2020). The potential participants (individuals with AD and their caregivers -dyads) were recruited from the three memory clinics. They were informed of the ALSOVA study orally and in writing, emphasizing the voluntary nature of their participation and the confidentiality of the collected data. Both the individual with AD and the caregiver signed the informed consent form. The caregiver also provided proxy consent on behalf of the individual with AD.

Evaluations

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (Beck, Ward, Mendelson, Mock, & Erbaugh, Citation1961), a widely studied self-rating scale, evaluated FC depressive symptoms. Values vary between 0 and 63; a higher score means more severe depressive symptoms. The General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) (Goldberg & Hillier, Citation1979) measured FC distress. It is a self-administrated questionnaire. Values vary between 0–36, with a higher score indicating more distress. Following scales were used to measure the symptoms of an individual with AD. The NPI (Cummings et al., Citation1994) measured neuropsychiatric symptoms. The NPI is a structured interview for caregivers, including 12 behavioral and psychological symptoms typical of AD. Values vary between 0–144, and a higher score means more severe symptoms. The Clinical Dementia Rating Sum of Boxes (CDR-sb) (Morris et al., Citation1993) measured dementia severity. The CDR is a semi-structured clinician-rated interview assessing memory, orientation, judgment and problem-solving, community affairs, home and hobbies, and personal care. Values vary between 0–18, with a higher score indicating more severe dementia. The Alzheimer Disease Cooperative Study – Activities of Daily Living (ADCS-ADL) scale (Galasko et al., Citation1997) measured daily functioning. The ADCS-ADL is a structured interview for caregivers, including basic and instrumental ADL questions. Values vary between 0–78, with a higher score indicating better functional ability. These three scales are widely used in clinical AD studies and are reliable and valid.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS Statistical software (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 22.0) and R version 3.5.3 (R Core Team, Citation2019). We constructed a latent class mixed model with “patient ID” as a random effect to identify different trajectories of FC depressive symptoms (the BDI scores). Baseline characteristics were expressed as means and standard deviations or frequencies and propositions. We performed a logistic regression model to determine factors that differed between trajectory groups 2 and 3 (demographic information, CDR-sb, NPI, ADCS-ADL, GHQ). The Friedman Test evaluated the statistical difference in changes in repeated measures. The χ2 test was used to analyze differences between groups in the drop-out rate and the intervention effect for the original ALSOVA study intervention. P-values <0.05 were considered to indicate statistically significant results.

Results

The baseline characteristics of study participants are presented in . In Finland, the recommended cutoff scores of BDI for research are ≥10 for mild depression and ≥19 for moderate depression (Aalto, Citation2011). Among 226 participants, 139 (61.5%) had at least mild depressive symptoms (BDI scores >10) at baseline.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of study participants.

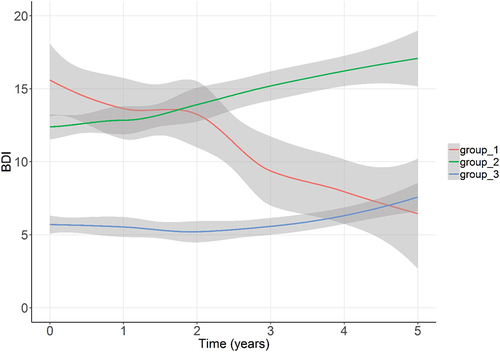

During the five-year follow-up, the latent class mixed model was used to identify different trajectories for FC depressive symptoms (BDI scores). We identified three different trajectories for FC depressive symptoms, which are shown in : (1) A few (7.5%) FCs had depressive symptoms at the time of the individual with AD AD diagnosis (baseline), and the symptoms diminished during follow-up; (2) 32.7% of FCs had depressive symptoms at baseline, and the symptoms increased over follow-up, and (3) 59.7% of FCs had minor depressive symptoms that remained constant throughout the study. Due to the small number of participants in group 1 and the drop-out rate, further analyses included only groups 2 and 3. We named these trajectory groups as major depressive symptoms (group 2) and minor depressive symptoms (group 3).

Figure 1. Trajectories of depressive symptoms of caregivers during a five-year follow-up. Depressive symptoms were evaluated with the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). Group 1 has declining, group 2 major and increasing, and group 3 minor and stable depressive symptoms, respectively. A higher BDI score means more severe depressive symptoms.

shows the proportions of participants in groups 2 (major depressive symptoms) and 3 (minor depressive symptoms). We also evaluated how many FCs had mild (≥10), moderate (≥19) or severe (<19) depressive symptoms (BDI scores) during each follow-up visit. We also analyzed the changes in the proportions of FCs in these BDI categories during follow-up. We report these apart for trajectory groups 2 and 3. We found significant changes in group 2 at the three-year (p < .001) and five-year follow-ups (p = .002). In group 3, the change was not significant at the three-year follow-up (p = .112) but was significant after five years (p = .007). In group 1 (data not shown), the change was significant after the first three years (p = .007) but not at the five-year follow-up (p = .112). These changes showed similar significance when we evaluated them based on a continuous BDI variable.

Table 2. Proportions of family caregivers with no depression (BDI < 10), mild depression (BDI = 10–18), and moderate depression BDI ≥ 19 during a five-year follow-up.

Univariate regression analyses () revealed significant differences in characteristics between groups 2 and 3, including the sex of the individual with AD (p = .004, OR 0.43, CI 0.24–0.77), the relationship between the FC and individual with AD marital, other; p = .004, OR 0.35, CI 0.17–0.72), and the FC’s age (p = .016, OR 1.03, CI 1.01–1.06). Furthermore, these groups showed significant differences in the baseline distress level (GHQ) of the FC (p = .001, OR 1.29, 1.18–1.40) and the neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPI) of the individual with AD (p = .005, OR 1.04, CI 1.01–1.08). There were no significant differences between groups in the individuals with AD MMSE, ADC-ADL, and CDR-sb scores. These findings indicated that, compared to the FCs in group 3, the FCs in group 2 felt more distress during caregiving. They were more often a spouse of an individual with AD, their individual with AD were more often male, and their individual with AD had more neuropsychiatric symptoms. The groups were not significantly different in the proportions assigned to the control and intervention groups in the ALSOVA study. The groups were not significantly different in the drop-out rates.

Table 3. Baseline univariate logistic regression analyses of clinical and demographic variables on BDI trajectory group 2 major and group 3 minor depressive symptoms.

Discussion

The current study was one of the few to identify trajectories of depressive symptoms among FCs of individuals with AD (Ornstein et al., Citation2014). The majority (67.3%) of FCs in this study belonged to the trajectory group that did not show substantial depressive symptoms, even in the sixth year after the Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis, in accordance with the previous study (Ornstein et al., Citation2014).

A small group of FCs belonged to the group that showed depressive symptoms at baseline that diminished during the five-year follow-up, especially during the first three years. This kind of reduction in depressive symptoms was not found in a previous longitudinal (Ornstein et al., Citation2014) or a shorter intervention study (Kuo et al., Citation2017). On the other hand, in a short follow-up study of 69 dyads by Tentorio et al. (Citation2020), FC levels of depression declined significantly during a one-year follow-up, even though they did not receive any intervention, like psychological counseling, in addition to their usual care. Several possible explanations exist for diminishing depressive symptoms, for example, psychological resilience to depressive symptoms in caregivers (O’Rourke et al., Citation2010). However, in our study, the group that showed diminishing depressive symptoms was small; thus, this result may represent an exception to the rule.

The most common trajectory in our study represented minor depressive symptoms, which were experienced by almost two-thirds of FCs over the five-year follow-up. Similarly, Ornstein et al. (Citation2014) identified two main trajectories of FC depression over a six-year follow-up, although they used different depression measures.

In the present study, only one participant with minor symptoms reached the cutoff level for moderate depression throughout the follow-up. However, the analysis of changes revealed a tendency for BDI to increase in the minor symptom group during the last two years of follow-up. Recent studies showed that protective factors associated with FC depressive symptoms were: participation in leisure activities (Lee, Ryoo, Crowder, Byon, & Wiiliams, Citation2020), the ability to pay for basic needs (Miller, Killian, & Fields, Citation2020), and self-compassion (Hlabangana & Hearn, Citation2020).

Notably, in the present study, there were no significant differences in baseline cognition among individuals with AD between groups 2 and 3. That finding further supported the previous assumption that caregivers’ depressive symptoms were independent of the decline in cognitive function in individuals with AD (Hasegawa et al., Citation2014; Voutilainen, Ruokostenpohja, & Välimäki, Citation2018; Yuan et al., Citation2020); instead, depressive symptoms in caregivers were more related to the other symptoms present in AD or the individual characteristics of the FC.

In the present study, one-third of caregivers experienced increasing depressive symptoms (group 2), which is in line with a previous meta-analysis (Collins et al., Citation2020) which showed that nearly one-third of caregivers experienced depression. Among these, 17.6% reported moderate depressive symptoms (BDI ≥ 19) at the beginning of caregiving, but this proportion increased to 55.6% in the fifth follow-up year. In this group, BDI scores increased significantly during the entire follow-up. We also found that caregivers who experienced increased depressive symptoms had more symptoms at baseline when they started caregiving. In fact, several baseline characteristics were associated with an increasing trajectory of depressive symptoms.

It is essential to recognize which caregivers are at risk of increasing depression when the diagnostic examinations for AD are performed.

We previously showed that female spouses taking care of individuals with neuropsychiatric symptoms experienced the most distress based on the subjective general health questionnaire (GHQ) (Hallikainen, Koivisto, & Välimäki, Citation2018). The GHQ was developed to assess changes in psychological health. The present study found that the same factors were associated with the trajectories of FC depressive symptoms. FCs in the trajectory group with major depressive symptoms felt more distress during caregiving, were more often the spouse of an individual with AD, their care recipients were more often male, and had more neuropsychiatric symptoms. Other symptoms of an individual with AD did not affect the caregiver’s depression. Our results corroborated with previous results by Ornstein et al. (Citation2014), taking into account that in the study of Ornstein et al. (Citation2014), caregivers were followed beyond the person with AD nursing home placement. The impact of gender (Arai et al., Citation2014), living with older people with not specified dementia (Arai et al., Citation2014; Kaufman, Lee, Vaughon, Unuigbe, & Gallo, Citation2019; Ying et al., Citation2018), and neuropsychiatric symptoms of persons with dementia (Arthur et al., Citation2018; Hasegawa et al., Citation2014; Huang et al., Citation2015; Lee et al., Citation2017; Ying et al., Citation2018) on FC depression has also been found in several cross-sectional studies.

The relationships between the caregiving burden, distress, and depression are not simple. We previously reported that FC depressive symptoms were associated with distress (based on the GHQ) (Välimäki, Martikainen, Hallikainen, Väätäinen, & Koivisto, Citation2015). However, results are conflicting regarding how care recipients’ depressive symptoms are related to the caregiving burden (Ying, Citation2018; Miller et al., Citation2020).

Studies have shown that psychosocial group interventions with individual counseling could reduce the risk of major depression (Sperling et al., Citation2020). Those interventions could be beneficial to use more in routine care. Some recent studies have analyzed more complicated relationships between depression and feelings. For example, guilt (Corey et al., Citation2020) and grief (Jain et al., Citation2019) have been associated with caregiver depressive symptoms.

Further investigation is needed to understand why some caregivers have relatively persistent or increasing depressive symptoms. The results from the present study corroborated previous findings that showed that adverse psychological effects accumulated in female spousal caregivers taking care of individuals with neuropsychiatric symptoms (Välimäki et al., Citation2015, Citation2016; Ying, Yap, Gandhi, & Liew, Citation2018). Available counseling and support services are most often provided to individuals with AD, and sometimes to FCs, but rarely to dyads or families. Ying et al. (Citation2018) proposed interventions focusing on caregivers’ competency and the demands and symptoms of individuals with dementia.

The heterogeneity of caregivers is not recognized. Too often, support and counseling are ill-timed, not targeted to family needs, or insufficient overall. Some families with AD may receive only the minimum services in their municipalities. Recent evidence on caregiver interventions has shown promising results (Frias et al., Citation2020; Lee et al., Citation2020), but implementations in typical primary care settings have been inadequate. To provide efficient support services for FCs, it is necessary to conduct services that meet their needs (Zwingmann et al., Citation2020).

In our study, only individuals with diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease were included at the time of the diagnosis. Dissimilar types of progressive memory disorders may impact the onset of caregivers’ depressive symptoms differently because the disease courses vary.

Due to some study limitations, our findings must be interpreted with caution. The main potential limitation was that many burdened caregivers might have dropped out of the study during the follow-up. However, there was no significant difference in the drop-out rates between groups. Nevertheless, this study was one of the few community-based studies with a five-year follow-up, and the follow-up was started at the time of AD diagnosis and was done at the very mild or mild phase of AD. Also, this study followed home-dwelling dyads with standard treatment of AD according to Finnish national guidelines by local memory clinics.

Conclusion

The present study showed that FC depressive symptoms existed, but most FCs belonged to the trajectory group that showed minor symptoms during the follow-up period. Approximately one out of three caregivers experienced increasing depressive symptoms over five years, and these FCs were particularly vulnerable to depression as caregiving continued. This susceptibility should be detected when the FC begins caregiving to ensure that tailored support can be provided. In memory clinics, family caregivers’ depressive symptoms could be detected using validated scales, for example, incorporated with annual health checks. The level of depression at the beginning of caregiving and score change from previous years should alarm health care providers.

Clinical implications

Recognizing caregivers at risk of increasing depression in the early phase of caregiving is vital before the minor depressive symptoms are prolonged.

In future clinical practice, caregivers’ heterogeneity needs to be considered in service planning in memory policlinics and support services for families.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data is not available due to ethical restrictions. Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is unavailable.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aalto, A.-M. (2011, January 26). Back in depressiokysely 21-osioinen (käyttö väestötutkimuksiin). TOIMIA-suositus. Retrieved from https://www.terveysportti.fi/apps/dtk/tmi/article/tmm00083/search/bdi

- APA. (1994). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

- Arai, Y., Kumamoto, K., Mizuno, Y., & Washio, M. (2014). Depression among family caregivers of community-dwelling older people who used services under the long term care insurance program: A large-scale population-based study in Japan. Aging and Mental Health, 18(1), 81–91. doi:10.1080/13607863.2013.787045

- Arthur, P. B., Gitlin, L. N., Kairalla, J. A., & Mann, W. C. (2018). Relationship between the number of behavioral symptoms in dementia and caregiver distress: What is the tipping point? International Psychogeriatrics, 30(8), 1099–1107. doi:10.1017/S104161021700237X

- Beck, A. T., Ward, C. H., Mendelson, M., Mock, J., & Erbaugh, J. (1961). An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 4(6), 561–571. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004

- Cheng, S. T., Lam, L. C. W., & Kwok, T. (2013). Neuropsychiatric symptom clusters of Alzheimer’s disease in Hong Kong Chinese: Correlates with caregiver burden and depression. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 21(10), 1029–1037. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.041

- Collins, R. N., & Kishita, N. (2020). Prevalence of depression and burden among informal caregivers of people with dementia: A meta-analysis. Ageing and Society, 40(11), 2355–2392. doi:10.1017/S0144686X19000527

- Corey, K. L., McCurry, M. K., Sethares, K. A., Bourbonniere, M., Hirschman, K. B., & Meghani, S. H. (2020). Predictors of psychological distress and sleep quality in former family caregivers of people with dementia. Aging and Mental Health, 24(2), 233–241. doi:10.1080/13607863.2018.1531375

- Cummings, J. L., Mega, M., Gray, K., Rosenberg-Thompson, S., Carusi, D. A., & Gornbein, J. (1994). The neuropsychiatric inventory: Comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology, 44(12), 2308–2314. doi:10.1212/wnl.44.12.2308

- Frias, C. E., Garcia-Pascual, M., Montoro, M., Ribas, N., Risco, E., & Zabalegui, A. (2020). Effectiveness of a psychoeducational intervention for caregivers of people with dementia with regard to burden, anxiety and depression: A systematic review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 76(3), 787–802. doi:10.1111/jan.14286

- Galasko, D., Bennett, D., Sano, M., Ernesto, C., Thomas, R., Grundman, M., & Ferris, S. (1997). An inventory to assess activities of daily living for clinical trials in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders, 11(SUPPL. 2), S33–S39. doi:10.1097/00002093-199700112-00005

- Goldberg, D. P., & Hillier, V. F. (1979). A scaled version of the general health questionnaire. Psychological Medicine, 9(1), 139–145. doi:10.1017/S0033291700021644

- Hallikainen, I., Koivisto, A. M., & Välimäki, T. (2018). The influence of the individual neuropsychiatric symptoms of people with Alzheimer’s disease on family caregiver distress—A longitudinal ALSOVA study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 33(9), 1207–1212. doi:10.1002/gps.4911

- Hasegawa, N., Hashimoto, M., Koyama, A., Ishikawa, T., Yatabe, Y., Honda, K., … Ikeda, M. (2014). Patient-related factors associated with depressive state in caregivers of patients with dementia at home. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 15(5), 371.e15–371.e18. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2014.02.007

- Hlabangana, V., & Hearn, J. H. (2020). Depression in partner caregivers of people with neurological conditions; associations with self-compassion and quality of life. Journal of Mental Health, 29(2), 176–181. doi:10.1080/09638237.2019.1630724

- Huang, S. S., Liao, Y. C., & Wang, W. F. (2015). Association between caregiver depression and individual behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia in Taiwanese patients. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry, 7(3), 251–259. doi:10.1111/appy.12175

- IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0, Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

- Jain, F. A., Connolly, C. G., Moore, L. C., Leuchter, A. F., Abrams, M., Ben-Yelles, R. W., … Iacoboni, M. (2019). Grief, mindfulness and neural predictors of improvement in family dementia caregivers. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 13. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2019.00155

- Kaufman, J. E., Lee, Y., Vaughon, W., Unuigbe, A., & Gallo, W. T. (2019). Depression associated with transitions into and out of spousal caregiving. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 88(2), 127–149. doi:10.1177/0091415018754310

- Koivisto, A. M., Hallikainen, I., Välimäki, T., Hongisto, K., Hiltunen, A., Karppi, P., … Martikainen, J. (2016). Early psychosocial intervention does not delay institutionalization in persons with mild Alzheimer disease and has impact on neither disease progression nor caregivers’ well-being: ALSOVA 3-year follow-up. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 31(3), 273–283. doi:10.1002/gps.4321

- Kuo, L. M., Huang, H. L., Liang, J., Kwok, Y. T., Hsu, W. C., Su, P. L., & Shyu, Y. L. (2017). A randomized controlled trial of a home-based training programme to decrease depression in family caregivers of persons with dementia. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 73(3), 585–598. doi:10.1111/jan.13157

- Lee, M., Ryoo, J. H., Crowder, J., Byon, H. D., & Wiiliams, I. C. (2020). A systematic review and meta-analysis on effective interventions for health-related quality of life among caregivers of people with dementia. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 76(2), 475–489. doi:10.1111/jan.14262

- Lee, J., Sohn, B. K., Lee, H., Seong, S., Park, S., & Lee, J. Y. (2017). Impact of behavioral symptoms in dementia patients on depression in daughter and daughter-in-law caregivers. Journal of Women’s Health, 26(1), 36–43. doi:10.1089/jwh.2016.5831

- McKhann, G., Drachman, D., Folstein, M., Katzman, R., Price, D., & Stadlan, E. M. (1984). Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: Report of the NINCDS-ADRDA work group⋆ under the auspices of department of health and human services task force on Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology, 34(7), 939–944. doi:10.1212/wnl.34.7.939

- Miller, V. J., Killian, M. O., & Fields, N. (2020). Caregiver identity theory and predictors of burden and depression: Findings from the REACH II study. Aging and Mental Health, 24(2), 212–220. doi:10.1080/13607863.2018.1533522

- Morris, J. C. (1993). The clinical dementia rating (CDR): Current version and scoring rules. Neurology, 43(11), 2412–2414. doi:10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a

- O’Rourke, N., Kupferschmidt, A. L., Claxton, A., Smith, J. Z., Chappell, N., & Beattie, B. L. (2010). Psychological resilience predicts depressive symptoms among spouses of persons with Alzheimer disease over time. Aging and Mental Health, 14(8), 984–993. doi:10.1080/13607863.2010.501063

- Ornstein, K., Gaugler, J. E., Devanand, D. P., Scarmeas, N., Zhu, C., & Stern, Y. (2013). The differential impact of unique behavioral and psychological symptoms for the dementia caregiver: How and why do patients’ individual symptom clusters impact caregiver depressive symptoms? American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 21(12), 1277–1286. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.062

- Ornstein, K., Gaugler, J., Zahodne, L., & Stern, Y. (2014). The heterogeneous course of depressive symptoms for the dementia caregiver. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 78(2), 133–148. doi:10.2190/AG.78.2.c

- Ownby, R. L., Peruyera, G., Acevedo, A., Loewenstein, D., & Sevush, S. (2014). Subtypes of sleep problems in patients with Alzheimer disease. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 22(2), 148–156. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2012.08.001

- Piercy, K. W., Fauth, E. B., Norton, M. C., Pfister, R., Corcoran, C. D., Rabins, P. V., … Tschanz, J. T. (2013). Predictors of dementia caregiver depressive symptoms in a population: The cache county dementia progression study. Journals of Gerontology - Series B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 68(6), 921–926. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbs116

- R Core Team. (2019). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing(Version 3.5.3) [Computer software]. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Retrieved from https://www.R-project.org/.

- Sallim, A. B., Sayampanathan, A. A., Cuttilan, A., & Ho, R. (2015). Prevalence of mental health disorders among caregivers of patients with Alzheimer Disease. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, PMID: 26593303 16(12), 1034–1041. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2015.09.007.

- Schulz, R., Cook, T. B., Beach, S. R., Lingler, J. H., Martire, L. M., Monin, J. K., & Czaja, S. J. (2013). Magnitude and causes of bias among family caregivers rating Alzheimer disease patients. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 21(1), 14–25. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2012.10.002

- Simpson, C., & Carter, P. (2013). Short-term changes in sleep, mastery & stress: Impacts on depression and health in dementia caregivers. Geriatric Nursing, 34(6), 509–516. doi:10.1016/j.gerinurse.2013.07.002

- Sperling, S. A., Brown, D. S., Jensen, C., Inker, J., Mittelman, M. S., & Manning, C. A. (2020). FAMILIES: An effective healthcare intervention for caregivers of community dwelling people living with dementia. Aging and Mental Health, 24(10), 1700–1708. doi:10.1080/13607863.2019.1647141

- Sutter, M., Perrin, P. B., Chang, Y. P., Hoyos, G. R., Buraye, J. A., & Arango-Lasprilla, J. C. (2014). Linking family dynamics and the mental health of Colombian dementia caregivers. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, 29(1), 67–75. doi:10.1177/1533317513505128

- Tentorio, T., Dentali, S., Moioli, C., Zuffi, M., Marzullo, R., Castiglioni, S., & Franceschi, M. (2020). Anxiety and depression are not related to increasing levels of burden and stress in caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, 35, 153331751989954. doi:10.1177/1533317519899544

- Välimäki, T. H., Martikainen, J. A., Hallikainen, I. T., Väätäinen, S. T., & Koivisto, A. M. (2015). Depressed spousal caregivers have psychological stress unrelated to the progression of Alzheimer disease: A 3-year follow-up report, Kuopio ALSOVA study. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 28(4), 272–280. doi:10.1177/0891988715598229

- Välimäki, T. H., Martikainen, J. A., Hongisto, K., Väätäinen, S., Sintonen, H., & Koivisto, A. M. (2016). Impact of Alzheimer’s disease on the family caregiver’s long-term quality of life: Results from an ALSOVA follow-up study. Quality of Life Research, 25(3), 687–697. doi:10.1007/s11136-015-1100-x

- Voutilainen, A., Ruokostenpohja, N., & Välimäki, T. (2018). Associations across caregiver and care recipient symptoms: Self-organizing map and meta-analysis. Gerontologist, 58(2), e138–e149. doi:10.1093/geront/gnw251

- Ying, J., Yap, P., Gandhi, M., & Liew, T. M. (2018). Iterating a framework for the prevention of caregiver depression in dementia: A multi-method approach. International Psychogeriatrics, 30(8), 1119–1130. doi:10.1017/S1041610217002629

- Ying, J., Yap, P., Gandhi, M., & Liew, T. M. (2018). Validity and utility of the center for epidemiological studies depression scale for detecting depression in family caregivers of persons with dementia. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 47(4–6), 323–334. doi:10.1159/000500940

- Yuan, Q., Tan, T. H., Wang, P., Devi, F., Ong, H. L., Abdin, E., … Subramaniam, M. (2020). Staging dementia based on caregiver reported patient symptoms: Implications from a latent class analysis. PLoS ONE, 15(1), e0227857. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0227857

- Zwingmann, I., Dreier-Wolfgramm, A., Esser, A., Wucherer, D., Thyrian, J. R., Eichler, T., … Hoffmann, W. (2020). Why do family dementia caregivers reject caregiver support services? Analyzing types of rejection and associated health-impairments in a cluster-randomized controlled intervention trial. BMC Health Services Research, 20(1). doi:10.1186/s12913-020-4970-8