ABSTRACT

An extensive body of literature documents large-scale property-led redevelopment in the world and in China. However, in recent years China has seen the policy shift toward small-scale redevelopment, heritage preservation, and public participation in the regeneration process. Using the pilot project of “micro-regeneration” (weigaizao) in Guangzhou, this paper critically examines these aspects of change. We find that such a policy shift is attributed to increasing social contestations generated by large-scale redevelopment. The state uses heritage preservation to develop creative and cultural industries, which transforms the traditional neighborhood into a commercial and tourist quarter. The policy also encourages participation in urban redevelopment. However, residents still have limited influence over the course of redevelopment. The paper argues that micro-regeneration is a practice of worlding cities in the Chinese institutional context, involving the state dealing with the problems of redevelopment through new governance approaches.

Introduction

Large-scale property-led redevelopment has been a ubiquitous landscape of the globalizing world (Orueta & Fainstein, Citation2008). Originating from the United Kingdom, the concept of property-led redevelopment refers to “the assembly of finance, land, building materials and labor to produce or improve buildings for occupation and investment purposes” (Turok, Citation1992, p. 362). This approach often adopts wholesale demolition and dispossession, giving greater power to the developer in city-building (Fainstein, Citation2001). However, instead of thinking of the inevitable dominance of global capital and large-scale projects, urban regeneration is influenced by urban politics and the process of “worlding” to create a desirable policy outcome (Roy & Ong, Citation2011). This approach to urban regeneration is subject to constant adjustment to deal with the problems and challenges identified by policymakers.

Large-scale property-led redevelopment has been extensively studied in China (Guo et al., Citation2018; He & Wu, Citation2005; Lin, Citation2015; Schoon & Altrock, Citation2014; Shih, Citation2010; Tian & Yao, Citation2018; Y. Zhang & Fang, Citation2004). However, in recent years, a new approach of “micro-regeneration” (weigaizao or weigengxin), emphasizing on small-scale, heritage conservation, and public participation that has been experimented in many Chinese cities is still underexamined despite some publications discussing its governance mode (M. Wang et al., Citation2022; Wu et al., Citation2022; Yao et al., Citation2021; Ye et al., Citation2021; Yu et al., Citation2021). Similar to culture-led and heritage-led urban regeneration, the new approach stresses the value of culture and heritage (J. Wang, Citation2009; Zhong, Citation2016; Zhu, Citation2018). It also encourages community participation in the process of redevelopment (Hui et al., Citation2021; X.Li et al., Citation2020; Verdini, Citation2015; Xu & Lin, Citation2019).

This policy shift aims to avoid the problems encountered in earlier large-scale redevelopment, such as housing demolition, heritage degradation, and residential displacement (Chen et al., Citation2020; He & Wu, Citation2005; Lin, Citation2015; Tan & Altrock, Citation2016; Wu et al., Citation2013; Q. Yang & Ley, Citation2019; Zhang, Citation2017). It also hopes to address the problem of low efficiency of land use in inner-city areas (Chen & Qu, Citation2019; Liu & Xu, Citation2018; Wei, Citation2022). However, it is not clear whether these policy objectives have been achieved and what roles of culture and heritage play in micro-regeneration.

China is now prioritizing urban redevelopment because of constraints on land resources. As more than 63% of the nation’s population is now living in urban areas (China National Bureau of Statistics, Citation2021), redeveloping existing urban areas has become an important task. Understanding new approaches to urban redevelopment has significant policy implications. Theoretically, this paper enriches the emerging literature on micro-regeneration or micro-rehabilitation in China, and compares the approach with property-led redevelopment which have been studied by growth machine theory (Brenner, Citation2019). Thinking along the lines of “worlding practices” (Roy & Ong, Citation2011), we demonstrate the variegation of redevelopment approaches, multiple logics, and policy actors’ understandings of the “problems” and their tactics.

In this paper, we critically examine these new practices and try to answer the following questions. Why has the redevelopment policy shifted from large-scale property-led redevelopment to micro-regeneration? What are the intentions behind the policy shift? What are the new features of this new type of incremental regeneration? What are the roles of culture and heritage in micro-regeneration? Has micro-regeneration achieved its policy objectives?

The remainder of this paper consists of seven sections. The second section starts with a literature review of urban redevelopment. The research methods are then introduced in the third section. Following that, the case of Yongqingfang is briefly presented in the fourth section. The next three sections examine, respectively, the new features of micro-regeneration. Our key findings are concluded in the final section.

Literature review: Variegated approaches to urban redevelopment

Large-scale property-led redevelopment, culture-led, and participatory planning

Large-scale property-led redevelopment has prevailed for the past few decades for its rapid economic returns. Growth machine theory, first introduced in the United States by Molotch (Citation1976), explains the application of this approach. Molotch (Citation1976) elaborated on how land-based interests become a common objective for local business elites and government officials to form a pro-growth coalition to construct and develop cities. Local growth machines are heavily dependent on land development because the intensification of land can generate different forms of revenue including taxes, transaction fees, and its related surcharges through urban housing and real estate development, which eventually promotes population growth in a certain locality. Among all types of development, property-led (re)development has become the most popular approach for its visible physical changes to the built environment since the 1960s.

Though growth machine theory is useful in explaining the reasons for city growth, more and more empirical cases from the 1980s onward have shown the emergence of anti-growth community movements (Goetz, Citation1994). This trend indicates that the original concept of growth machine focusing on state-market relations—the role of local pro-growth coalition between economic elites and the local state—might not be sufficient or accurate enough to illustrate urban growth in every place (Logan et al., Citation1997).

The application of growth machine theory outside the United States is debated. An increasing body of literature adopts and expands the concept of the growth machine in terms of who forms the coalition (Cochrane, Citation2019; Kulcsar & Domokos, Citation2005; Pinson, Citation2019; Valiyev, Citation2014). For example, Pinson (Citation2019, p. 541) contends “in European cities, property developers are no longer the only capitalists able to establish lasting relationships with urban governments, which has an impact on the content of development policies.” Kulcsar and Domokos (Citation2005) observe how some external players, such as transnational corporations, have considerable impacts on local development.

Regarding increasing social conflicts generated by property-led redevelopment, the concept of “redevelopment through preservation” was proposed to not only emphasize physical and spatial changes, but also reshape and enhance the cultural and social diversities in local neighborhoods (Harvey, Citation2001; Reichl, Citation1997; Zukin, Citation1996). From an entrepreneurial perspective, however, culture and heritage have become new “economic assets” in the global battle for sustainable investment and massive tourism (Florida, Citation2014; Peck, Citation2005; Ryberg-Webster & Kinahan, Citation2014). Culture-led redevelopment under the guise of culture and heritage preservation is usually a tactic proposed by the local government and implemented by the private sector for developing luxurious real estates and generating profits from global tourism (De Cesari & Dimova, Citation2019).

The roles of key actors, such as property investors and developers, are clearly revealed in property-led and culture-led redevelopment. However, such economic achievements come at the expense of the displaced local communities, which has generated increasing contestations, social unrest, and calls for greater participation in urban redevelopment. Participatory planning has been involved in the planning theory and practices in the United States (Day, Citation1997) and European countries (Foley & Martin, Citation2000) since the 1960s and the 1970s, which is considered to indicate a healthy democracy. It is tightly linked with the four core themes in contemporary social sciences: namely, participation, democratic decision-making, political equality, and consensus-making (Monno & Khakee, Citation2012). The traditional top-down rationalist approach taken by the local authority to decisions on planning issues is designed to achieve its own political and economic objectives, and often fails to consider the needs of underrepresented groups. Whereas participatory planning emphasizes collective decision-making by a plurality of actors, it especially helps project-affected neighborhoods, and the wider general public play a fundamental role in counterbalancing the system of power, resulting in a more even redistribution of resources and profound urban governance readjustments.

Changing urban redevelopment in China

Analysis of China’s urban redevelopment has widely adopted growth machine theory because of a similar pro-development agenda and social consequences, such as uneven redistribution, displacement, and gentrification (S. He & Wu, Citation2005; He, Citation2019; Lin, Citation2015; Shin, Citation2016; Wu, Citation2018). In addition, many scholars reveal the pivotal role of the local state in pro-growth coalition in property-led (re)development after the country’s 1994 marketization and tax-sharing reform (S. He & Wu, Citation2005; Y. R. Yang & Chang, Citation2007; Ye, Citation2011).

Property-led redevelopment

Property-led redevelopment has been accelerated since 1998 when a new financial system was established to support real estate developers and individuals with mortgages and loans to participate in the housing market. Then, in the early 2000s, the central government promulgated a regulation to legalize monetary compensation as an alternative to in-kind compensation. At the same time, large-scale redevelopments have been stimulated by mega events, such as the 2008 Summer Olympic Games in Beijing, the 2010 World Expo in Shanghai, and the 2010 Asian Games in Guangzhou (Lin, Citation2015; Wu, Citation2016; Wu et al., Citation2013). Under the name of city re-imagining and city betterment, local governments managed to initiate demolition campaigns. In Beijing, it was estimated that the demolition of 171 villages in the city might lead to the eviction of about 37 million residents (Shin & Li, Citation2013). Similarly, three million households in traditional neighborhoods were relocated in Shanghai before the World Expo mega event (X. Ren, Citation2014). About 138 villages in the city of Guangzhou, covering an area of 500,000 acres, were also identified for redevelopment by the municipal government before the Asian Games. Among them, 52 were planned to be demolished entirely within 3 to 5 years (Liang et al., Citation2018). At that time, the GDP-ism was the main measurement for the performance of the local state (Li & Zhou, Citation2005). The local pro-growth coalition enjoyed handsome profits from the mushrooming large-scale redevelopment.

Large-scale redevelopment has intensified social issues such as uneven redistribution, forced relocation, gentrification, and degradation of historic-cultural relics (Chen et al., Citation2020; He, Citation2012; Hu & Morales, Citation2016; Lee, Citation2016; Lin et al., Citation2022; González Martínez, Citation2016; Shih, Citation2010; Z. Wang, Citation2020; X. Wang & Aoki, Citation2019; Wu et al., Citation2013). More importantly, the social network of residents was broken up. “Domicide” (Zhang, Citation2017) and the resistance of nail households (dingzihu; Shin, Citation2013) have become common phenomena in major Chinese cities.

These negative outcomes have to some extent put local government officials’ career advancement at risk (Oakes, Citation2019). In order to mitigate such conflicts, some inner-city regeneration projects have been implemented with special efforts to preserve and reuse local culture and heritage. Moreover, in recent years, the concept of participatory planning has been adopted and practiced in China’s urban regeneration processes, aiming to enhance public participation. In the reminder of this section, we review recent studies on culture and heritage preservation and participatory planning.

Culture and heritage preservation

Rather than treating historical neighborhoods as “illnesses” of the city, various redevelopment projects were initiated in the 2000s under the name of culture and heritage preservation (S.He, Citation2019; Oakes, Citation2019; J.Wang, Citation2009; J. Wang & Li, Citation2017; Zhao et al., Citation2020; Zhong, Citation2016; Zhu, Citation2018). However, in the recent decade, many scholars have argued that culture and heritage preservation is not the actual intention of redevelopments to promote creative industries; instead, cultural heritage is a value-laden concept that associates with economic, social, and political processes in urban redevelopment (De Cesari & Dimova, Citation2019; Kuutma, Citation2013; Tomba, Citation2017). For example, Oakes (Citation2019) contends that the purpose for which the local government launched a happiness campaign in the city of Tongren was not simply about generating happiness by promoting certain activities and practices, but to use the city as a biopolitical machine to achieve its designated social ends. The cultural policy helps the local state maintain social order and reinforce its power (Oakes, Citation2019). Zhu (Citation2018, p. 182) summarizes four core purposes for the local government’s use of the Chinese history of Xi’an: “a mark of tourism to motivate consumption; a theme for city branding and marketing; a trigger for community-based pride or nostalgia; and a motif for protesting individual rights.”

As a result, policy speculations, external economic interferences, and uncontrolled heritage consumption undeniably put displacement pressure on local residents (X. Wang & Aoki, Citation2019). He and Wu (Citation2005) find that although the core area of Xintiandi in Shanghai has been preserved during the redevelopment, their residential function has been dramatically changed into high-end commercial space. Wai (Citation2006) further argues that the history of Shanghai is selectively preserved by the local government and developers to nurture a new consumption space for tourists and the middle-class. Zhong (Citation2016) investigates three artistic sites (M50, Tianzifang, and the Red Town) in Shanghai and concludes that art production and urban redevelopment are two strongly connected fields in state-controlled China. She focuses on the artists in culture-led redevelopment and finds out that only elite artists, being part of the growth coalition with the local state and developers, are capable of possessing all types of benefits. The non-elite artists who also have made considerable contributions to promoting artistic and cultural environment in certain inner-city areas are excluded from the growth coalition and have little power to acquire the benefits. Hu and Morales (Citation2016) also evaluate the unintended impacts of culture-led redevelopment in Nanluoguxiang, Beijing and conclude that even though the creative industries improve the quality of life for residents in the old neighborhood and economic prosperity, mass tourism put the goal of heritage preservation and community conservation at risk. In a word, the local state uses culture and heritage as active tools to legitimize the process of city beautification and gentrification in historical inner-city areas. That is to say, “cultural heritage has become a governance strategy for the state to reinforce its control over the production of space and the functioning of society” (Zhu & González Martínez, Citation2022, p. 477).

Participatory planning

Because of the decentralization of the state, the increasing awareness of civil society, and the negative social outcomes generated by large-scale property-led redevelopment, the concept of participatory planning has increasingly gained recognition and popularity in many recent urban regeneration projects in China, despite how its institutional setting differs from its Western counterparts (Chen & Qu, Citation2019; Hui et al., Citation2021; Li et al., Citation2020; Xu & Lin, Citation2019; Verdini, Citation2015; Wei, Citation2022; Zhang et al., Citation2020). For example, Hui et al. (Citation2021) contend that different stakeholders can be incentivized to be involved in the process of regeneration through a participatory planning workshop jointly organized by university professionals, adopting the case of Shapowei regeneration in Xiamen. The workshop not only serves as a platform for different groups who are closely related to the regeneration project, but also helps the public participate in the implementation process. For example, planners designed open space and proposed community activities, which helps support the health of the community. Li et al. (Citation2020) use the case of Shenjing village in Guangzhou to illustrate how partial interests of the planning scheme can be avoided and a consensus can be achieved among the local state, villagers, social organizations, and other actors through a collaborative workshop led by urban planners. Similarly, Yuan et al. (Citation2021) argue that the third sector plays a central role in an inner-city community regeneration project in Guangzhou. Their participation in the project helps bridge connection and communication and build up a collaborative network among different stakeholders. More essentially, the third sector helps complement the institutional design of the local planning institutions.

However, the above research tends to pay particular attention to the role of the third sector without questioning the level of involvement had by the local communities and marginalized groups, and whether the redistribution of resources becomes fairer. With Arnstein’s (Citation1969) influential arguments in mind, some researchers indicate that public participation in China is still at an incipient stage. For example, by examining the housing requisition cases in Shanghai, Xu and Lin (Citation2019) discuss that despite the superficial involvement of local residents in the process, non-registered residents, tenants, and migrants are entirely excluded. Public participation is rhetorically adopted by the district government as a response to the higher-level government in order to facilitate the process of housing requisition more effectively and with fewer potential social contradictions. Zhang et al. (Citation2020) compared different styles of participation in Beijing and Guangzhou. They suggest that although residents in Guangzhou tend to be more active than people in Beijing, the adoption of micro-regeneration might actually constrain their participation in these projects in the future. Wei (Citation2022) further argues that the participation approaches adopted in Baitasi regeneration in Beijing are “the tyranny of participation.” Three distinctive manifestations match with the concept of tyrannical participation. First, the entire policy framework was pre-set by the local authority without consulting with the residents, meaning that the latter are excluded from the decision-making process; second, the relocation work was more or less completed with the financial support of the movers who are both users of and payers for the relocation, which features the logic of “user-pays”; and finally, the already underprivileged groups (tenants and migrants) become even more marginalized socially and economically due to the increasing living expenses, changing living environment, and fractured social networks (Wei, Citation2022).

Although the market-friendly investment environment and participatory planning in China allow private developers and residents to become more involved in the process of redevelopment, the methods also help the local state maintain its power in urban redevelopment (M. Wang et al., Citation2022). First, the ownership of urban land belongs to the local state. Second, the local state manages the land transaction and draws up the (re)development plan. Third, paid transfers of urban land use rights are legalized, meaning that the local state has been granted the right to use the state land for property development projects. The local state benefits from redevelopment through land-transfer fees and land-related taxes and surcharges which have become major contributions to local revenue (Ye, Citation2011). Though some positive social outcomes can be observed from recent urban regeneration practices in China by adopting the participatory planning approach, only certain groups of people can become involved in and get benefits from it. In this sense, participatory planning strategies proposed by the local state are instruments to help itself achieve political objectives such as maintaining social stability, rather than considering the demands from local communities (M. Wang et al., Citation2022; Wei, Citation2022; Wu et al., Citation2022).

Research methods

This research adopts the pilot project of Yongqingfang (around 7200 m2) in Enning Road as its study area. It used to be a traditional neighborhood of old Guangzhou. We chose the city of Guangzhou and the pilot project for four main reasons. First, Guangzhou is one of the four first-tier cities in China which has experienced large-scale property-led redevelopment for decades. The tensions between economic growth, land supplies, and social stability have become fiercer than those in smaller cities. Second, unlike other first-tier cities, Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen, which have special administrations and preferable policy supports from the central government, the cases in Guangzhou may have more in common with other ordinary cities. Third, the policy of micro-regeneration was initiated in the city prior to 2020 when it became a national-level redevelopment approach. Fourth, apart from Yongqingfang, another 23 pilot projects were identified by the municipal government for incremental regeneration (Guangzhou Municipal Government, Citation2016), but none of them caught the same amount of attention from the central government, social media, and general public.

This research incorporated a mixed-method design (semi-structured interviews, non-participant observations, and desk research). Four instances of fieldwork spanning from May 2017 to June 2022 were undertaken in Guangzhou. A total of 39 in-depth interviews were conducted with government officials from Guangzhou Municipal Government, Guangzhou Urban Renewal Bureau, and Liwan District Government. Other actors including developers from Guangzhou Vanke, designers, researchers, and journalists related to the Yongqingfang project were also interviewed. Each interview lasted from around 25 minutes to three hours. Repeated visits to Yongqingfang and its surrounding areas were made during the daytime and at night, which allowed us to observe how residents, tourists, and small business owners live and work. In addition, we attended various festivals and promotional events at Yongqingfang to examine how the place was commercialized through these programs. We also interviewed seven local inhabitants who live in and around Yongqingfang. Most of them are low-income residents who refused to be off-site relocated in the past rounds of large-scale demolition. In combination with the fieldwork data, we collected and used information from local newspapers, governmental documents, and official statistics about the urban redevelopment of Guangzhou.

Yongqingfang: The pilot project of micro-regeneration

Before the municipal government introduced the new approach of micro-regeneration (weigaizao or weigengxin), the initial redevelopment plan of Enning Road, where the site of Yongqingfang is located, was a property-led approach proposed in 2006 by the former head of Liwan District, Liu Ping. All historical dwellings within the 150,000 m2 area were planned to be taken down. The demolition project was justified at that period because Guangzhou would be the host city for the 2010 Asian Olympic Games. Between 2006 and 2014, the district government implemented two major rounds of large-scale demolition. However, the top-down redevelopment has generated great social contestation from the general public over the issues of relocation, displacement, and heritage preservation (Lee, Citation2016; Tan & Altrock, Citation2016; M. Wang et al., Citation2022; Wu et al., Citation2022; Yao et al., Citation2021; Ye et al., Citation2021; Yu et al., Citation2021). The intensifying social unrest caused by demolition caught the attention of the central government (C. Zhang & Li, Citation2016). As a result, the demolition work was stagnated and, without proper maintenance, the once vibrant neighborhood became dilapidated and unsanitary.

The fate of Enning Road changed in 2014 when new national political mandates paid more attention to the promotion of Chinese culture and the preservation of Chinese heritage. Since President Xi took leadership, he has constantly mentioned the importance of preserving and inheriting Chinese culture and history. To cope with the political mandates, local governments have formulated many preservation-related plans and regulations, such as Regulations on the Protection of Intangible Cultural Relics in Guangdong (Guangdong Provincial Government, Citation2011), Measures for the Protection of Historical Buildings and Historical Areas in Guangzhou (Guangzhou Municipal Government, Citation2014), and Plans for Conservation of the Famous Historical-cultural Metropolis of Guangzhou (Guangdong Provincial Government, Citation2016).

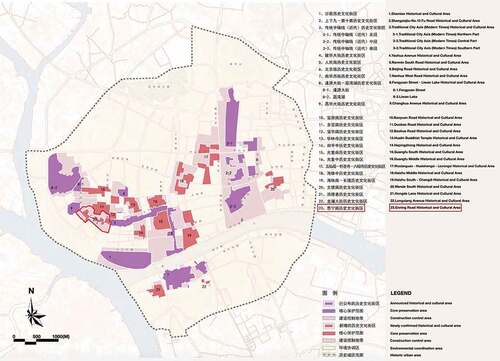

Besides, in 2014, the Chinese premier Li Keqiang proposed “mass entrepreneurship and innovation” (dazhong chuangye wanzhong chuangxin). He emphasized that the proposed policy was not limited to the field of technology, commerce, and culture, but also supported the innovation of ideas and institutions so that more creative vigor could be injected into the public (State Council of China, Citation2016). Under these circumstances, 23 historical and cultural areas (including Enning Road redevelopment area) were confirmed and announced by the Guangzhou Municipal Government in 2014. The newly appointed head of Liwan District Liu Jie selected the Yongqingfang quarter from Enning Road redevelopment area for a demonstration project of “micro-regeneration” in late 2015 (). The quarter only contains one alley and two short lanes, namely Yongqing Alley, the 1st Yongqing Lane, and 2nd Yongqing Lane. The designated plot is around 8,000 m2 with 90 dwellings, 61 of which are owned by the district government (Liwan District government, Citation2015).

Figure 1. 23 Historical and Cultural Areas of Guangzhou. Source: Adapted from Enning Road Historical and Cultural Area Preservation Plan by the authors (Liwan District Land Resources and Planning Bureau, Citation2018).

The objective of Yongqingfang micro-regeneration was twofold. One was to preserve local culture and history. The proposal emphasized that the preservation of heritage and cultural relics should be a prerequisite for future redevelopment. The other redevelopment goal was to stimulate commercial development and creative economy. To do so, the initiative of mass entrepreneurship and innovation proposed by the Chinese premier was introduced in the neighborhood. Creative and cultural industries were welcomed in order to attract and support young entrepreneurs with good business ideas to incubate their work and, eventually, transform the residential neighborhood into a unique and vibrant “maker town” (chuangke xiaozhen; L. He, Citation2020).

To support the neighborhood’s transformation, the Liwan District Government formulated two special guidelines to shorten the time of planning approval (Liwan District Government, Citation2016a) and allow the functional transformation of old residential houses and the operation of small businesses in Yongqingfang (Liwan District Government, Citation2016b).

In the following three sections, we will examine the policies for small-scale, conservation-oriented, and participatory redevelopment.

Small-scale redevelopment

Compared to the initial demolition area of the Enning Road redevelopment, the area of micro-regeneration is small and compact, containing around 5% of the original area. The plot of Yongqingfang from the Enning Road redevelopment area was selected for micro-regeneration mainly because over 90% of households in this small neighborhood have accepted the compensation scheme and moved out in the past rounds of redevelopment. The property right of these dwellings has been managed by the district government, which prevents potential social conflict and confrontation.

Although the redevelopment scale of Yongqingfang was relatively small when compared to large-scale demolition and renewal, it still faced some financial, legal, and social challenges. For example, the district government lacked funding to carry out the new project after the 2010 Asian Games. Besides, the work of housing expropriation and demolition was not fully completed in the previous rounds of the Enning Road redevelopment, meaning that no land use certificate was granted for the project. Therefore, it was impossible for the project to go through the process of planning applications for construction (guihua baojian). More importantly, because of the two rounds of large-scale demolition in the past 2 decades, residents have difficulty trusting the local government. Any further implementation may cause social resistance.

Considering these issues and challenges, the district government of Liwan gave up carrying out the redevelopment by itself. Instead, the government sought financial support from the private sector. The government officials chose the developer, Vanke, one of the largest real estate companies in China, because such top-ranking companies could guarantee the smoothness and efficiency of certain projects. However, real estate developers needed a stronger financial incentive to take part in the seemingly nonprofit project. To do so, the government waived the taxes generated from the redevelopment project and signed an additional agreement with Vanke, promising that if they could invest and complete the Yongqingfang micro-regeneration successfully, three other plots in Fangcun, located at the urban fringe of the district, would be leased to them to carry out new-build commercial property development (M. Wang et al., Citation2022).

The pilot project of Yongqingfang was operated through a build-operate-transfer (BOT) model, which defined the legal responsibility of the local state and the developer. The district government drew up the plan for the micro-regeneration project and acted as a supervisor. Its main responsibilities included deciding the land use and housing functions of the project, formulating policies and guidelines, and supervising the project implementation and management. In this demonstration project, a 15-year operation contract was signed by both parties. Vanke would take charge of the project investment for housing refurbishment and renovation, environmental beautification, and business promotion. After the agreed operation time, the district government would evaluate the project performance and decide whether to arrange a new agreement with the developer for further investment and management.

As can be seen from the above discussion, so-called small-scale redevelopment still uses public private partnership. But in the process, the private sector, Vanke, plays only the role of property manager. The local state is much stronger. Vanke is required to keep the original appearance of these buildings but is allowed to make functional changes. The use of the “small-scale” redevelopment approach hopes to generate more social consensus as the process of redevelopment is not through demolition, but gradually enhances the physical appearance of dwellings and of the public environment more broadly. The small scale is therefore used as a tactic.

Although the scale of micro-regeneration is small, its social impact is significant as most of the indigenous residents have been relocated to the outskirts of the city. For those who still live in the neighborhood, their social networks were broken. Moreover, their daily life has been affected by the commercial activities organized by the developer.

Culture and heritage preservation

The redevelopment area of Enning Road was one of the 23 (now extended to 26) historical and cultural areas (lishi wenhua jiequ) in old Guangzhou, well-known for its traditional arcade houses (qilou). Many famous dwellings were located in this area, including the Cantonese Opera Academy, Baoqing Pawnshop, and Golden Sound Cinema (L. Ren, Citation2007). Apart from being the neighborhood where Cantonese Opera celebrities lived and worked, this area was also famous for its xiguan culture, such as Cantonese embroidery and ivory sculpture, which have been recorded in the list of intangible cultural heritage at the national or municipal level. In order to promote the culture of Cantonese Opera, the Cantonese Opera Art Museum was constructed near Yongqingfang and opened to the public in 2016. Therefore, for the Museum’s image, the dilapidated neighborhood was in an urgent need of environmental upgrades.

To break the long stagnation caused by large-scale demolition, the district government adopted heritage preservation. It was proposed that the neighborhood would become a place for innovative and creative industries. Specifically, any business related to co-working, science and technology, creative culture, youth rental apartments, education, and cafés and restaurants that provide food without using natural or coal gas were welcomed. In addition, both store tenants and local residents were able to apply for a business license from the street office (jiedaoban) for temporarily using the residential houses for local business (Liwan District Government, Citation2016b). In practice, dwellings in the neighborhood were carefully evaluated and recorded according to their housing style and materials and the construction time, despite 53 dwellings being in severely damaged condition.

During our site visits to Yongqingfang in 2017 and 2018, the façades of the historical dwellings were well preserved, but their interiors and the housing structures have been reconstructed and transformed dramatically. The internal structures of some houses on the same side of the lane have been demolished and reconstructed in order to create more space for offices and entertainment.

Based on our observation, over 80% of the stores were for entertainment and commercial uses, including restaurants offering cuisines from all over the world, cozy cafés, whiskey bars, and self-service grocery stores, creating a more international-friendly business environment, and matching the taste of the middle-class and tourists. Interestingly, after President Xi’s visit in October 2018, many of these restaurants and bars were replaced by Chinese restaurants, local souvenir stores, tearooms, and exhibition halls for Chinese paintings and Cantonese embroidery. Besides, the local government initiated a three-million Yuan fund to invite and support ten representative successors of national intangible cultural heritage projects to establish their own studios in Yongqingfang (). This demonstration area has later become Guangzhou’s first “Intangible Cultural Heritage District” (feiyi jiequ), which opened to the public in August 2020. What is more, small businesses are only approved if they are relevant to Cantonese or xiguan history and culture.

All these new types of stores have been introduced for consumption by heritage fans, domestic and international tourists, and the middle-class, while none of them facilitates the basic needs of local habitants. Because of the increasing rental prices, many traditional small businesses, such as hardware stores and barbershops, that once served indigenous residents have been replaced.

According to the plan, the function of most houses would be transformed into space for entrepreneurs and co-working, education and training, as well as long-term rental apartments for young professionals. In detail, the co-working space and education and training space would be placed near the main entrance of Yongqingfang, containing an area of 2,500 m2 and 1,000 m2, respectively. Old dwellings at the northeast side of Yongqingfang would be transformed into long-term rental apartments. At the same time, around 1,000 m2 of commercial services and business would be facilitated in the neighborhood. An estimated total cost of 65 million Yuan would be invested for the housing transformation and environmental beautification. In addition, some small pocket squares and green spaces were created.

The principle of heritage preservation in “micro-regeneration” emphasizes the preservation of the physical structure of dwellings but reduction in their residential uses. Therefore, plenty of reconstruction works have been undertaken in the neighborhood to make sure that the dilapidated or even collapsed dwellings are refurbished or rebuilt in their old or traditional style. To do so, the façades of historical dwellings are well refurbished and renovated, and old materials such as bricks and tiles are recycled and reused to recreate the neighborhood in its traditional style. However, the interiors and structures of public housing are transformed to allow the change from residential to entertainment, exhibition, education, and co-working spaces. On August 22, 2020, Yongqingfang was officially listed as a national 4A-level tourist attraction, welcoming more than 40,000 daily visitors. In January 2022, it was selected as one of the 55 National Tourism and Leisure Districts in China.

Again, as can be seen from the functional changes, this emphasis on culture and heritage does not preserve the local culture as residents no longer live in the area. Like culture-led regeneration, the redevelopment has significantly transformed the nature of local areas (J. Wang et al., Citation2016). Within the policy of micro-regeneration, the understanding of “culture” and “heritage” is very narrow.

Participatory planning

Before the Yongqingfang micro-regeneration project, local activism and contests had some influence on the development process for Enning Road. With help from local media and university researchers, residents signed an appeal and reported it to the central government (Tan & Altrock, Citation2016; M. Wang et al., Citation2022), which then changed the pace and direction of the redevelopment during the past decade. Otherwise, the whole area of Enning Road would have been demolished. In this sense, even if public participation at that time was not formulated in any planning guidelines and policies, the public did influence the course of redevelopment.

The micro-regeneration project began to encourage public consultation. First, a joint committee organized by university professionals and formed by local residents was established after the implementation of micro-regeneration. Second, an evaluation committee was established right after the project’s completion. Members of the committee are local government officials, representatives from Vanke, university professionals, and journalists from local media. The primary goal of the committee is to evaluate whether the project is feasible and fair. It took the committee around half a year for the evaluation, including several rounds of formal group meetings and presentations.

Although the new policy encourages the involvement of the residents, their influence is very limited. First, it was the district government that drew up the plan for Yongqingfang redevelopment, and the implementation work was conducted by the developer, Vanke. There was little active and direct involvement of indigenous residents in the decision-making process.

Second, the content of the evaluation mainly focuses on physical aspects such as design layouts, construction, and implementation processes, with less consideration of social aspects such as the quality of life and demands of local residents. This is largely because the committee is invited and sponsored by Vanke. Public participation does not change how the project is evaluated. The project evaluation largely emphasized the physical changes of the project but lacked detailed investigation of residents’ daily life in the ever-changing neighborhood.

Third, the residents could hardly negotiate the outcomes of compensation. Some residents complained about the compensation scheme, because the benefit depended on the timing of negotiation. It seemed that the longer the residents lived in the neighborhood, the more chances they had to get a better compensation deal. Sometimes the compensation fees for two neighboring houses could be vastly different, ranging from 2,000 to 5,000 Yuan per m2. The other factor was the location of the house. If the dwelling was close to the main alley, a higher compensation deal could be achieved through negotiation. Though some residents did not agree with the developer to refurbish their houses or flats, they suffered from construction noise or damage to their own flats. Some residents had to temporarily move out during the renovation work on their neighbors’ flats due to safety concerns.

Fourth, public engagement does not change the course of redevelopment. The once quiet neighborhood became chaotic and noisy due to numerous promotional events. To attract more tourists and younger generations, it was estimated that more than a hundred events have taken place in the small quarter of Yongqingfang within a year. The social network and the traditional lifestyle in the inner-city neighborhood were severely disturbed, if not completely destroyed. There was no doubt that the redevelopment project would still meet some contestation over uneven compensation, housing refurbishment, heritage preservation, and indirect displacement.

Conclusion

Taking Yongqingfang as an example, this paper has examined the implementation of micro-regeneration in traditional residential neighborhoods. We observe the recent policy shift from large-scale demolition to small-scale and incremental regeneration, which now prevails in many Chinese cities, especially those along the coastal area, and analyze the underlying reasons for such a policy shift.

This paper has both empirical and theoretical contributions to the field of urban studies. Empirically, the case was a pilot project of micro-regeneration in China, and our study provides a comprehensive and thorough review of its implementation and subsequent social impacts on the local community. We identify and summarize three main features of the micro-regeneration policy: being implemented on a small-scale, adopting the approaches of culture and heritage preservation, and the involvement of public participation.

These new features are, in fact, tactics proposed by the local state to generate social consensus (Zhu & González Martínez, Citation2022) and align its urban regeneration policies with national political mandates (Wu et al., Citation2022). Micro-regeneration usually contains a small site. Instead of taking down historical dwellings overnight, their façades have been well preserved and refurbished according to their construction history and building materials. Before micro-regeneration, heritage preservation was regarded as a development barrier (Lee, Citation2016; Tan & Altrock, Citation2016), whereas now some old dwellings are refurbished and renovated to maintain the appearance of traditional neighborhoods. The interior and structure of many long-standing houses have been changed or reconstructed to facilitate new commercial spaces. Based on the refurbishment of historical buildings, creative and cultural industries are introduced into the neighborhood. Some intangible local cultures such as Cantonese opera, embroidery, and ivory sculptures in this case are selectively preserved and presented in the neighborhood. The project invites representative successors of national intangible cultural projects to set up their own studios with financial support from the local government to attract domestic and international tourists, as well as young entrepreneurs. Although local residents are encouraged to participate in the consultation process, they cannot change the plan for redevelopment or course of action. The preservation work is not geared toward improving the quality of life for indigenous habitants. The neighborhood has been transformed into a touristic hub combining spaces for co-working, entertainment, and exhibition. The once quiet and peaceful traditional neighborhood has eventually become a commercial and cultural quarter that welcomes hundreds of thousands of visitors every single day. As for local residents, they suffer from the noise in the commercialized neighborhood and the loss of social networks. Many have left the neighborhood, making displacement unavoidable in the end. New social issues related to tourism, gentrification, uneven redistribution, and indirect displacement are generated by accelerated micro-regeneration.

Most of micro-regeneration practices are increasingly observed in cities within or close to China’s coastal areas, such as Beijing (Wei, Citation2022), Shanghai (Chen & Qu, Citation2019), Guangzhou (M. Wang et al., Citation2022; Wu, Citation2022, pp. 87-91), Shenzhen (Chen & Qu, Citation2019; Zhan, Citation2021), and Tianjin (X. Wang & Aoki, Citation2019), whereas only a few cases are conducted in inland or western cities (see, for example, Zhao et al., Citation2020; Zhu, Citation2018).

There are two main reasons for this regional difference. Firstly, coastal-area cities are relatively more developed and richer, meaning the land value is much higher than that in western and inland cities. The costs of a large-scale property-led redevelopment through wholesale demolition are getting increasingly unaffordable for many local governments. Therefore, to maintain or even increase local revenues more sustainably, they need to initiate strategies for redeveloping land at a relatively smaller scale. Secondly, social resistance tends to be stronger and much more severe in coastal-area cities because indigenous residents are more informed and active regarding the redevelopment issues due to a more active social media environment and a stronger connection through kinship and social networks in a local context. Since economic performance is no longer the only consideration for local government officials’ career advancement, they must maintain social stability, preserve culture and heritage, and improve the local environment, etc. In this sense, the policy of micro-regeneration, which targets all the above goals, has increasingly been initiated and adopted in these cities. The fact that micro-regeneration projects are much more popular in coastal-area cities than inland and western cities reveals the regional inequality in China.

We also examine the multiple roles of culture and heritage in micro-regeneration. In this pilot project, “heritage” not only refers to tangible elements such as historical dwellings and traditional arcade houses, but also includes intangible things such as authentic local food sold by street venders and handicrafts created by artisans and craftsmen. The preservation approach in Yongqingfang tends to stress the tangible aspects and does not manage to restore intangible social and cultural ones.

Considering the value-based approach in mind, in Yongqingfang project, the multilayered roles of culture and heritage can be seen from at least three aspects. Firstly, from the economic perspective, the once dilapidated and poor neighborhood was replaced by office, entertainment, and recreational spaces for city branding and capital accumulation. These spaces have generated new forms of commercial and recreational activities that match the taste of the middle-class and visitors from all over the country. Secondly, from the cultural perspective, historical dwellings such as the ancestral home of Bruce Lee and traditional arcade houses representing the local past can enhance people’s sense of belonging, trigger their nostalgia as well as find their cultural identity, which generates a wider acceptance of urban redevelopment from the general public. Thirdly, from the political perspective, preserving local culture and heritage aligns with the central government’s mandates of carrying forward Chinese civilization and maintaining social stability. In this sense, heritage-led redevelopment distinguishes itself from other kinds of redevelopment by targeting multiple but contradictory goals at the same time. Through heritage-led redevelopment, on the one hand, the idealized city image is created, which helps promote local business and economy; on the other hand, the state power is reinforced.

Recently, there is an emerging literature on public participation in Chinese urban regeneration (see, for example, Hui et al., Citation2021; Xu & Lin, Citation2019). The regeneration project of Yongqingfang mainly involved expert-led consultancy activities. The general public involvement is still limited. Even so, the project expands the scope of public participation compared with previous property-led redevelopment. The narrow understanding of heritage so far does not involve more engagement of the neighborhood, partially because many public housing residents have been relocated before micro-regeneration. Current heritage preservation actually restricts rather than encourages wider public participation. In the long term, urban redevelopment might create more conflicts with local residents as relocation is inevitable for converting residential neighborhoods into commercial streets or business premises. As the case of Yongqingfang reveals, the conversion of the neighborhood to business uses creates an environment that is less suitable for residential purposes.

Theoretically, this research compares the case of micro-regeneration with property-led redevelopment research and highlights the varieties of policy practices on the ground. While the regeneration project includes some consideration of economic development, for example, the creation of shared business space, other motivations and imperatives exist, such as heritage preservation and public participation.

There have been critical reflections on the limitation of the locally based growth machine (Brenner, Citation2019) and the role of the central government and multi-scalar states in China (Wu et al., Citation2022). The state politics at the national level and political mandates constrain the impetus of property-led redevelopment. The property developer is involved in micro-regeneration. But there are negotiations between the government and the property developer. In this case, the local government imposes some key requirements while leaving the developer to manage the property as it sees appropriate for its business operation. The scope of profit-making in Yongqingfang is regulated in that the developer can only act as a property manager to collect rents from businesses rather than selling commercial properties and housing. However, Yongqingfang is still a small area to pilot a new approach to urban regeneration. Whether it is possible to carry out urban regeneration in a larger inner-urban areas remains to be seen. Therefore, it is still unclear whether China has departed from its property-led redevelopment.

Our research reveals how this new policy has been envisioned in response to the problems of earlier property-led mega projects and the changing national political environment. While growth machine theory focuses on the intensification of land uses to enhance and capture land value, our study explains multiple logics in which the value capture is not the only determinant. For example, the creation of shared business space, other motivations and imperatives exist, such as heritage preservation and public participation.

Similar to “worlding cities” that make the city global and competitive according to a specific vision by the state and business elites (Roy & Ong, Citation2011), micro-regeneration to some extent reflects multiple policy objectives. Although micro-regeneration differs from property-led redevelopment in some respects, it still heavily relies on land use changes and intensification, capturing land value to achieve some stated objectives. The outcome, however, is quite mixed.

In sum, critically reflecting on urban redevelopment theories, particularly from the perspectives of property-led redevelopment, heritage preservation, and public participation, we analyze the motivations behind the policy shift from large-scale demolition to incremental regeneration. It is undeniable that inner-city redevelopment is due to the land insufficiency caused by rapid urbanization through urban expansion in the past 3 decades (Lin, Citation2015). But the improvement of land use efficiency is not the only goal. Since President Xi assumed leadership in 2012, the national political environment has changed for urban (re)development. The national policy objectives include culture and heritage preservation and social stability. Local governments formulate and implement preservation-related projects (such as micro-regeneration) to show their alignments with the intentions of the central government. In this sense, the aims of micro-regeneration are more complicated, targeting multiple goals apart from economic growth. The existing literature on large-scale redevelopment focuses on growth machine dynamics but has paid insufficient attention to the changing political environment in China.

We argue that the new practices of micro-regeneration can be better explained by a performance of state entrepreneurialism that combines planning centrality and market instruments (Wu, Citation2018). Although the case is about China, urban regeneration’s subsequent impacts and key problems can also be observed in many other countries under a similarly authoritarian regime and market economy. The local state uses variegated approaches such as small-scale refurbishment and rehabilitation, commercialization of local culture and heritage, as well as public consultation and participation to redevelop traditional neighborhoods, according to its development agendas. The various development agendas of the local state are also affected by the changing strategies of the central government. Compared with a more defined agenda of large-scale property-led regeneration driven by the growth machine, this policy shift also indicates the objectives of the state and its sovereign power (Roy & Ong, Citation2011), which is not necessarily confined to revenue maximization (Wu et al., Citation2022; Zhan, Citation2021). In fact, the financial viability of this micro-regeneration is questionable.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the editor Dr. June Wang and three anonymous referees for their valuable comments on earlier drafts and thank the interviewees for sharing their time and views on Yongqingfang project. This research is supported by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant agreement No. 832845, Advanced Grant) ChinaUrban, and the National Social Science Fund Youth Project (grant No. 21CSH015).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Manqi Wang

Manqi Wang is a PhD candidate at the Bartlett School of Planning, University College London. Her research interests include urban redevelopment, urban governance, and gentrification in China.

Fangzhu Zhang

Fangzhu Zhang is an Associate Professor at the Bartlett School of Planning, University College London. Her main research interests focus on innovation and governance; urban redevelopment and migrant integration; and eco-innovation and eco-city development in China.

Fulong Wu

Fulong Wu is the Bartlett Professor of Planning at University College London. His research interests include urban development in China and its social and sustainable challenges.

References

- Arnstein, S. R. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35(4), 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225

- Brenner, N. (2019). New urban spaces: Urban theory and the scale question. Oxford University Press.

- Chen, Y., & Qu, L. (2019). Emerging participative approaches for urban regeneration in Chinese megacities. Journal of Urban Planning and Development, 146(1), 04019029. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)UP.1943-5444.0000550

- Chen, H., Wang, L., & Waley, P. (2020). The right to envision the city? The emerging vision conflicts in redeveloping historic Nanjing, China. Urban Affairs Review, 56(6), 1746–1778. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087419847769

- China National Bureau of Statistics. (2021). The country’s population development presents new characteristics and new trends. Retrieved July 9th, 2022, from http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/sjjd/202105/t20210513_1817394.html ( in Chinese)

- Cochrane, A. (2019). Riffing off Kevin Cox: Thinking through comparison. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 44(3), 537–539. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12766

- Day, D. (1997). Citizen participation in the planning process: An essentially contested concept? Journal of Planning Literature, 11(3), 421–434. https://doi.org/10.1177/088541229701100309

- De Cesari, C., & Dimova, R. (2019). Heritage, gentrification, participation: Remaking urban landscapes in the name of culture and historic preservation. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 25(9), 863–869. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2018.1512515

- Fainstein, S. (2001). The city builders: Property development in New York and London, 1980–2000. University of Kansas Press.

- Florida, R. (2014). The creative class and economic development. Economic Development Quarterly, 28(3), 196–205. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891242414541693

- Foley, P., & Martin, S. (2000). A new deal for the community? Public participation in regeneration and local service delivery. Policy and Politics, 28(4), 479–492. https://doi.org/10.1332/0305573002501090

- Goetz, E. G. (1994). Expanding possibilities in local development policy: An examination of US cities. Political Research Quarterly, 47(1), 85–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/106591299404700105

- González Martínez, P. (2016). Authenticity as a challenge in the transformation of Beijing’s urban heritage: The commercial gentrification of the Guozijian historic area. Cities, 59, 48–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2016.05.026

- Guangdong Provincial Government. (2011). “Guangdong sheng feiwuzhi wenhua yichan tiaoli” (Regulations on the Protection of Intangible Cultural Relics in Guangdong) Document No.66. Official Document. (in Chinese)

- Guangdong Provincial Government. (2016). “Guangzhou shi lishi wenhua mingcheng baohu tiaoli” (Plans for Conservation of the Famous Historical-cultural Metropolis of Guangzhou). Document No.77. Official Document. in Chinese

- Guangzhou Municipal Government. (2014). “Guangzhou shi lishi jianzhu he lishi fengmaoqu baohu Banfa” (Measures for the Protection of Historical Buildings and Historical Areas in Guangzhou). Document No.98. Official Document. (in Chinese)

- Guangzhou Municipal Government. (2016). “Guangzhou Chengshi gengxin xiangmu he jijin jihua” (Guangzhou Urban Renewal Projects and Funding Plan in 2016). Official Document. (in Chinese)

- Guo, Y., Zhang, C., Wang, Y. P., & Li, X. (2018). (De-) Activating the growth machine for redevelopment: The case of Liede urban village in Guangzhou. Urban Studies, 55(7), 1420–1438. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098017729788

- Harvey, D. C. (2001). Heritage pasts and heritage presents: Temporality, meaning and the scope of heritage studies. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 7(4), 319–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/13581650120105534

- He, S. (2012). Two waves of gentrification and emerging rights issues in Guangzhou, China. Environment & Planning A, 44(12), 2817–2833. https://doi.org/10.1068/a44254

- He, S. (2019). The creative spatio-temporal fix: Creative and cultural industries development in Shanghai, China. Geoforum, 106, 310–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.07.017

- He, L. (2020, June 15). Guangzhou Yongqingfang is more youthful today: Exploring new paths for urban refined management. People's Daily. http://politics.people.com.cn/n1/2020/0615/c1001-31746188.html

- He, S., & Wu, F. (2005). Property-led redevelopment in post-reform China: A case study of Xintiandi redevelopment project in Shanghai. Journal of Urban Affairs, 27(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0735-2166.2005.00222.x

- Hui, E. C. M., Chen, T., Lang, W., & Ou, Y. (2021). Urban community regeneration and community vitality revitalization through participatory planning in China. Cities, 110, 103072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2020.103072

- Hu, Y., & Morales, E. (2016). The unintended consequences of a culture-led regeneration project in Beijing, China. Journal of the American Planning Association, 82(2), 148–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2015.1131130

- Kulcsar, L. J., & Domokos, T. (2005). The post-socialist growth machine: The case of Hungary. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 29(3), 550–563. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2005.00605.x

- Kuutma, K. (2013). Concepts and contingencies in heritage politics. In L. Arizpe & C. Amescua (Eds.), Anthropological perspectives on intangible cultural heritage (pp. 1–15). Springer.

- Lee, A. K. Y. (2016). Heritage conservation and advocacy coalitions: The state-society conflict in the case of the Enning Road redevelopment project in Guangzhou. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 22(9), 729–747. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2016.1195427

- Liang, X., Yuan, Q., Tan, X., & Li, Z. (2018). Territorialization of urban villages in China: The case of Guangzhou. Habitat International, 78, 41–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2018.05.009

- Lin, G. C. (2015). The redevelopment of China’s construction land: Practicing land property rights in cities through renewals. The China Quarterly 865–887. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741015001228

- Lin, S., Liu, X., Wang, T., & Li, Z. (2022). Revisiting entrepreneurial governance in China’s urban redevelopment: A case from Wuhan. Urban geography, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2022.2079272

- Liu, L., & Xu, Z. (2018). Collaborative governance: A potential approach to preventing violent demolition in China. Cities, 79, 26–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2018.02.019

- Liwan District government. (2015). “Liwan qu fang mingxi dengji biao (2015)” (List of housing conditions in the Yongqing area (2015)). Guangzhou: Unpublished document. (in Chinese)

- Liwan District Government. (2016a). “Yongqing Pianqu chuangyi bangong shequ chanye guanli daoze” (Guideline for Managing Local Business in the Neighborhood of Yongqing Area (Report No.30)). Unpublished document. ( in Chinese).

- Liwan District Government. (2016b). “Yongqing Pianqu chuangyi bangong shequ chanye guanli daoze” (Guideline for Managing Local Business in the Neighborhood of Yongqing Area (Report No.30)). Unpublished document. ( in Chinese).

- Liwan District Land Resources and Planning Bureau. (2018). Enning road historical and cultural area preservation plan. Architectural Design and Research Institute of SCUT Co., LTD. ( in Chinese).

- Li, X., Zhang, F., Hui, E. C. M., & Lang, W. (2020). Collaborative workshop and community participation: A new approach to urban regeneration in China. Cities, 102, 102743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2020.102743

- Li, H., & Zhou, L. A. (2005). Political turnover and economic performance: The incentive role of personnel control in China. Journal of Public Economics, 89(9–10), 1743–1762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2004.06.009

- Logan, J. R., Whaley, R. B., & Crowder, K. (1997). The character and consequences of growth regimes: An assessment of 20 years of research. Urban Affairs Review, 32(5), 603–630. https://doi.org/10.1177/107808749703200501

- Molotch, H. (1976). The city as a growth machine: Toward a political economy of place. American Journal of Sociology, 82(2), 309–332. https://doi.org/10.1086/226311

- Monno, V., & Khakee, A. (2012). Tokenism or political activism? Some reflections on participatory planning. International Planning Studies, 17(1), 85–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563475.2011.638181

- Oakes, T. (2019). Happy town: Cultural governance and biopolitical urbanism in China. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 51(1), 244–262. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X17693621

- Orueta, F. D., & Fainstein, S. S. (2008). The new mega-projects: Genesis and impacts. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 32(4), 759–767. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2008.00829.x

- Peck, J. (2005). Struggling with the creative class. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 29(4), 740–770. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2005.00620.x

- Pinson, G. (2019). Rethinking the European exception. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 44(3), 540–542. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12786

- Reichl, A. J. (1997). Historic preservation and progrowth politics in US cities. Urban Affairs Review, 32(4), 513–535. https://doi.org/10.1177/107808749703200404

- Ren, L. (2007, May 12). Enning Road is encountering demolition, and Golden Sound Cinema will be demolished and fades out from the stage of history. News Express. http://news.sohu.com/20070512/n249980319.shtml. (in Chinese)

- Ren, X. (2014). The political economy of urban ruins: Redeveloping Shanghai. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38(3), 1081–1091. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12119

- Roy, A., & Ong, A. (Eds.). (2011). Worlding cities: Asian experiments and the art of being global. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Ryberg-Webster, S., & Kinahan, K. L. (2014). Historic preservation and urban revitalization in the twenty-first century. Journal of Planning Literature, 29(2), 119–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885412213510524

- Schoon, S., & Altrock, U. (2014). Conceded informality. Scopes of informal urban restructuring in the Pearl River Delta. Habitat International, 43, 214–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2014.03.007

- Shih, M. I. (2010). The evolving law of disputed relocation: Constructing inner‐city renewal practices in Shanghai, 1990–2005. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 34(2), 350–364. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2010.00895.x

- Shin, H. B. (2013). The right to the city and critical reflections on China’s property rights activism. Antipode, 45(5), 1167–1189. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12010

- Shin, H. B. (2016). Economic transition and speculative urbanization in China: Gentrification versus dispossession. Urban Studies, 53(3), 471–489. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098015597111

- Shin, H. B., & Li, B. (2013). Whose games? The costs of being “Olympic citizens” in Beijing. Environment and Urbanization, 25(2), 559–576. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247813501139

- State Council of China. (2016, March 3). Mass entrepreneurship and innovation as new growth engine. english.gov.cn. http://english.www.gov.cn/premier/news/2016/03/03/content_281475300571752.htm. (in Chinese)

- Tan, X., & Altrock, U. (2016). Struggling for an adaptive strategy? Discourse analysis of urban regeneration processes–A case study of Enning Road in Guangzhou City. Habitat International, 56, 245–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2016.06.006

- Tian, L., & Yao, Z. (2018). From state-dominant to bottom-up redevelopment: Can institutional change facilitate urban and rural redevelopment in China. Cities, 76, 72–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2018.01.010

- Tomba, L. (2017). Gentrifying China’s urbanization? Why culture and capital aren’t enough. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 41(3), 508–517. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12494

- Turok, I. (1992). Property-led urban regeneration: Panacea or placebo? Environment & Planning A, 24(3), 361–379. https://doi.org/10.1068/a240361

- Valiyev, A. (2014). The post-Communist growth machine: The case of Baku, Azerbaijan. Cities, 41, S45–S53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2014.06.008

- Verdini, G. (2015). Is the incipient Chinese civil society playing a role in regenerating historic urban areas? Evidence from Nanjing, Suzhou and Shanghai. Habitat International, 50, 366–372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2015.09.008

- Wai, A. W. T. (2006). Place promotion and iconography in Shanghai’s Xintiandi. Habitat International, 30(2), 245–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2004.02.002

- Wang, J. (2009). ‘Art in capital’: Shaping distinctiveness in a culture-led urban regeneration project in Red Town, Shanghai. Cities, 26(6), 318–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2009.08.002

- Wang, Z. (2020). Beyond displacement–exploring the variegated social impacts of urban redevelopment. Urban geography, 41(5), 703–712. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2020.1734373

- Wang, X., & Aoki, N. (2019). Paradox between neoliberal urban redevelopment, heritage conservation, and community needs: Case study of a historic neighborhood in Tianjin, China. Cities, 85, 156–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2018.09.004

- Wang, J., & Li, S. M. (2017). State territorialization, neoliberal governmentality: The remaking of Dafen oil painting village, Shenzhen, China. Urban Geography, 38(5), 708–728. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2016.1139409

- Wang, J., Oakes, T., & Yang, Y. (2016). Making cultural cities in Asia. Routledge.

- Wang, M., Zhang, F., & Wu, F. (2022). Governing urban redevelopment: A case study of Yongqingfang in Guangzhou, China. Cities, 120, 103420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2021.103420

- Wei, R. (2022). Tyrannical participation approaches in China’s regeneration of urban heritage areas: A case study of Baitasi historic district, Beijing. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 28(3), 279–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2021.1993310

- Wu, F. (2016). State dominance in urban redevelopment: Beyond gentrification in urban China. Urban Affairs Review, 52(5), 631–658. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087415612930

- Wu, F. (2018). Planning centrality, market instruments: Governing Chinese urban transformation under state entrepreneurialism. Urban Studies, 55(7), 1383–1399. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098017721828

- Wu, F. (2022). The end of (neo-)traditionalism. In Creating Chinese Urbanism: Urban revolution and governance changes (pp. 58–116). UCL Press. https://doi.org/10.14324/111.9781800083332

- Wu, F., Zhang, F., & Liu, Y. (2022). Beyond growth machine politics: Understanding state politics and national political mandates in China’s urban redevelopment. Antipode, 54(2), 608–628. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12781

- Wu, F., Zhang, F., & Webster, C. (2013). Informality and the development and demolition of urban villages in the Chinese peri-urban area. Urban Studies, 50(10), 1919–1934. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098012466600

- Xu, Z., & Lin, G. C. (2019). Participatory urban redevelopment in Chinese cities amid accelerated urbanization: Symbolic urban governance in globalizing Shanghai. Journal of Urban Affairs, 41(6), 756–775. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2018.1536420

- Yang, Y. R., & Chang, C. H. (2007). An urban regeneration regime in China: A case study of urban redevelopment in Shanghai’s Taipingqiao area. Urban Studies, 44(9), 1809–1826. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980701507787

- Yang, Q., & Ley, D. (2019). Residential relocation and the remaking of socialist workers through state-facilitated urban redevelopment in Chengdu, China. Urban Studies, 56(12), 2480–2498. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098018790724

- Yao, Z., Li, B., Li, G., & Zeng, C. (2021). Resilient governance under asymmetric power structure: The case of enning road regeneration project in Guangzhou, China. Cities, 111, 102971. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2020.102971

- Ye, L. (2011). Urban regeneration in China: Policy, development, and issues. Local Economy, 26(5), 337–347. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269094211409117

- Ye, L., Peng, X., Aniche, L. Q., Scholten, P. H., & Ensenado, E. M. (2021). Urban renewal as policy innovation in China: From growth stimulation to sustainable development. Public Administration and Development, 41(1), 23–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.1903

- Yuan, Y., Chen, Y., & Cao, K. (2021). The third sector in collaborative planning: Case study of Tongdejie community in Guangzhou, China. Habitat International, 109, 102327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2021.102327

- Yu, Y., Hamnett, C., Ye, Y., & Guo, W. (2021). Top-down intergovernmental relations and power-building from below in China’s urban redevelopment: An urban political order perspective. Land Use Policy, 109, 105633. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105633

- Zhan, Y. (2021). Beyond neoliberal urbanism: Assembling fluid gentrification through informal housing upgrading programs in Shenzhen, China. Cities, 112, 103111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2021.103111

- Zhang, Y. (2017). Domicide, social suffering and symbolic violence in contemporary Shanghai, China. Urban Geography, 39(2), 190–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2017.1298978

- Zhang, Y., & Fang, K. (2004). Is history repeating itself? From urban renewal in the United States to inner-city redevelopment in China. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 23(3), 286–298. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X03261287

- Zhang, C., & Li, X. (2016). Urban redevelopment as multi-scalar planning and contestation: The case of enning road project in Guangzhou, China. Habitat International, 56, 157–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2016.05.008

- Zhang, L., Lin, Y., Hooimeijer, P., & Geertman, S. (2020). Heterogeneity of public participation in urban redevelopment in Chinese cities: Beijing versus Guangzhou. Urban Studies, 57(9), 1903–1919. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019862192

- Zhao, Y., Ponzini, D., & Zhang, R. (2020). The policy networks of heritage-led development in Chinese historic cities: The case of Xi’an’s big wild Goose Pagoda area. Habitat International, 96, 102106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2019.102106

- Zhong, S. (2016). Artists and Shanghai’s culture-led urban regeneration. Cities, 56, 165–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2015.09.002

- Zhu, Y. (2018). Uses of the past: Negotiating heritage in Xi’an. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 24(2), 181–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2017.1347886

- Zhu, Y., & González Martínez, P. (2022). Heritage, values and gentrification: The redevelopment of historic areas in China. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 28(4), 476–494. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2021.2010791

- Zukin, S. (1996). The cultures of cities. Wiley-Blackwell.