ABSTRACT

In this article, we show how the post-migrant perspective fosters inclusive participatory urban development without reproducing the “either/or” logic of ethno-cultural origin that distinguishes between migrants and natives. Based on empirical research with local administrators and community organizers in the German cities of Berlin and Wiesbaden, we identify two key findings. First, we found that a multicultural understanding of migration—based on a gap between migrants and natives—still dominates in participatory urban development. Second, we show how participation practices overcame the migrant-native divide by mobilizing liminal in-between identities, negotiated at the boundaries of class, milieu, age, and neighborhood. We argue that participation based on the post-migrant perspective is inclusive by virtue of its ambiguity. It allows participants to decide what perspective they wish to adopt or how they position themselves in participation—without being reduced to a status as migrants.

Introduction

The International Organization of Migration defines immigration as “the act of moving into a country other than one’s country of nationality or usual residence, so that the country of destination effectively becomes his or her new country of usual residence” (Sironi et al., Citation2019, p. 103). In this article, we use the more general term migration which includes the ongoing social dynamics that do not end after settlement (Foroutan, Citation2019b). In order to describe “emigrants, returning migrants, immigrants, refugees, displaced persons and persons of immigrant background and/or members of ethnic minority populations that have been created through immigration,” we use the term migrant (Council of Europe, 2017, as cited in Foroutan, Citation2019b, p. 143).

In 2001, the German government declared for the first time that Germany is a migration society (Foroutan, Citation2019a; Yıldız, Citation2015). In other words, it admitted what had already been lived reality in the Federal Republic for over thirty years. Today, in nine of the ten largest German cities, migrants and their descendants constitute a third of the population. Due to personal migration experience, family ties and friendships, or political engagement, the everyday visibility of migration has become an urban normality (Foroutan, Citation2019b).

Planners and other participation practitioners address migrants for the most part at the neighborhood scale as a new target group for public participation, with the aim of ensuring equal access in urban development (Häußermann et al., Citation2007; Schnur, Citation2018). Public participation as a means of social inclusion and local democracy has long been criticized by urban scholars as tokenism (Arnstein, Citation1969; Friendly, Citation2019; Monno & Khakee, Citation2012) or the reproduction of existing power asymmetries and expert knowledge based on the logics of consensus and negotiation (Hillier, Citation2003; Purcell, Citation2009; Swyngedouw, Citation2011). Furthermore, area-based participation approaches address migrants as either a potential or a problem in urban development and continue to produce social exclusion based on origin or migration experience (Marquardt & Schreiber, Citation2015; Rodatz, Citation2012). To shed light on the ambivalence of so-called inclusive participation and marginalization based on migration, this article asks how participatory urban development can be organized so that the essentializing of migration is not reproduced and racialized ascriptions of migration are excluded.

We introduce a post-migrant perspective (Foroutan, Citation2019b; Römhild, Citation2017; Yıldız, Citation2015) to the field of urban research and planning in order to expose racial exclusion as Othering based on the migrant-native divide and to present an alternative conceptualization of more inclusive participation practices in urban development. The post-migrant perspective attempts to deconstruct the “either/or” logic of the migrant-native divide that sees migration as an aberration of the imagined sedentary white citizen, a notion that is no longer compatible with contemporary urban societies. The post-migrant perspective claims to transcend social ordering based on the migration experience and ethno-cultural difference, while acknowledging the existing structural power relations of exclusion that shape everyday urban life (Römhild, Citation2017). We show how liminal in-between markers of class, milieu, age, and neighborhood—negotiated at the boundaries of ethnicity and the migrant-native divide—foster inclusive participation practices. The in-between does not simply emphasize ethnicity, migration experience and sedentariness as the distinguishing features of participation, but takes into account the multiple belongings and situational positionalities of the participants in question (Bhabha, Citation2004).

With this approach, the post-migrant perspective offers an alternative framework to the prevailing dominant concept of multiculturalism (Burayidi, Citation2015; Fincher et al., Citation2014; Uitermark et al., Citation2005). Despite highlighting the importance of recognizing migration in participation, multiculturalism fails to question the migrant-native divide. This article utilizes existing research on the exclusionary dynamics of the gap between migrants and natives in urban development (Pilz & Kirndörfer, Citation2021; Wiest, Citation2020). It shows how the post-migrant perspective can be used to conceptualize participation practices and implement multi-faceted and parallel participation formats (Huning et al., Citation2021). Approaching public participation from a post-migrant perspective allows us to recognize essentialist avoidance and the conflicting logics of identifying “who is to be addressed and in what way” (Räuchle & Nuissl, Citation2019, p. 9).

Based on semi-structured expert interviews with participation practitioners from local and state administrations as well as civil society in Berlin and Wiesbaden, we analyzed notions of normality of migration in participatory urban development. These notions depict how migrant belonging is ordered and negotiated between social actors (Castro Varela & Mecheril, Citation2010), whereby the question of who belongs to society and who does not is always at the heart of the matter. We use this concept to examine the prevailing arguments about hegemonic interpretations of migration in the field of participatory urban development. Ideas about the normality of migration have a bearing on the understanding and behavior of planners and other participation practitioners and are therefore crucial to whether practices in participatory urban development are exclusive or inclusive. We consider participatory urban development as the joint production of public processes of participation at the neighborhood scale involving local administrations and community organizations. We emphasize that the social field of participatory urban development is not shaped exclusively by local administrations who mandate when participation is required, but also by community organizations who influence both implementation and participation.

Our findings show that multicultural notions of normality of migration dominate in the interviews with participation practitioners. These interviewees focus on normalizing ethno-cultural diversity, thereby reproducing an exclusionary migrant-native divide. Our analysis also reveals that post-migrant notions of normality of migration evolve in participation practices that address the exclusionary distinction between migrants and natives by linking them to liminal in-between markers of class, milieu, age, and neighborhood. We conclude by indicating how these in-between markers structure participatory spaces and formats.

We situate our research results within the framework of real-world labs. Real-world labs are transdisciplinary and transformative research infrastructures that build on joint knowledge production between academia and practitioners to promote societal change (Schäpke et al., Citation2018; Wanner et al., Citation2018). Developed in the field of sustainability sciences, real-world labs have an experimental character and use real-world experiments as central sites of transdisciplinary co-production to explore transformation on a limited temporal and local scale (Räuchle, Citation2021; Schäpke et al., Citation2018). We initiated one real-world lab in Berlin and one in Wiesbaden. The two cities differ in size and structure, but foster the institutionalizing of participation in urban development, e.g., with binding guidelines for citizen participation (for Berlin see SenSW—Senate Department for Urban Development and Housing, Citation2021; for Wiesbaden, see City of Wiesbaden, Citation2016). Both real-world labs were organized in the frame of the research project INTERPART (intercultural spaces of participation) and investigated the use of digital services to improve intercultural participation in urban development. The goal was to find out what precisely is meant by intercultural spaces of participation, the obstacles involved, and how participation practitioners can actively design these spaces (Huning et al., Citation2021). Within Berlin and Wiesbaden, we selected the neighborhoods Berlin-Moabit and Wiesbaden-Biebrich as case studies because both neighborhoods have been long-term sites of participatory urban development of the Socially Integrative City program for urban renewal and share similar population structures. We present our research from two different neighborhoods which makes it possible to contextualize the research findings in a comparative way.

The article is divided into six sections. The first section introduces the post-migrant perspective and multiculturalism as the key theoretical debates on which our analysis is based. The second section explains our methodological approach. In the subsequent section, we describe the neighborhoods of Berlin-Moabit and Wiesbaden-Biebrich, our case studies. The fourth and fifth sections present our findings on multicultural and post-migrant notions of normality of migration in participatory urban development. We conclude by discussing the implications of a post-migrant perspective for public participation and how a post-migrant perspective will affect planners and other actors who organize participation processes.

The post-migrant perspective in urban research

“Post-migrant” aspires to transcend “migration” as a disguised marker for racist exclusion, on the one hand, while embracing migration as social normality, on the other. (Foroutan, Citation2019b, p. 149)

The post-migrant perspective on society and spatial productions of everyday urban life seeks to recognize transnational migration as a normality in migration society. It also tries to displace migration as the dominant, stigmatizing marker of social difference, without ignoring “migrantization” which is a powerful tool of social exclusion (Dahinden, Citation2016; Foroutan, Citation2019a; Römhild, Citation2017). We define “migrantization” as a form of “Othering” (Ahmed, Citation2012) that sees migration as a deviation from the constructed norm of sedentariness and the eternal role of “just arriving” (El-Tayeb, Citation2011, p. XXV). A post-migrant perspective also opposes xenophobia and argues for a comprehensive critique of racism beyond the mere focus on nationality. It not only deconstructs the migrant-native divide to render visible the mechanisms of racial exclusion and structural privileging of sedentary whiteness, but also conceptualizes hybrid ways of identity formation. In doing so, it acknowledges intersectionality and reflects on the structural power relations of inclusion and exclusion by broadening the scope of identity formation to include ethnicity and the migrant-native divide, as well as the interconnectedness of difference markers such as race, class, gender, and lifestyle.

By referring to Bhabha’s concept of the “in-between” (Citation2004, p. 41), the post-migrant perspective transcends rigid ethno-cultural ascriptions and the simplifying of migration as the eternal difference. By highlighting liminal identities, it also cuts across sedentariness that is both unquestioned and considered a monolithic fixed positionality. Bhabha (Citation2004) describes the stairwell as a liminal in-between space that connects binaries—similar to sedentariness and migration or Turkish and German—and leaves room for interaction and movement between them. The in-between space itself remains ambivalent. Although it connects highly influential sedentariness and marginal migration, it cannot completely eliminate the power relations involved. To operationalize the in-between for the context of participation, we argue that in-between spaces of migration and ethnicity need an intersection with other categories, such as race, class, gender, or lifestyle that transcend the dominant categories, e.g., migrant and native or German and Turkish, in order to enter and structure participation. These categories function as in-between markers, as a door to the stairwell, and create liminal in-between spaces. The liminal nature of the in-between refers to the agency of people to position themselves toward group identities, multiple belongings, and the moving between them without the constraint of having to settle for an ultimate location (Yıldız, Citation2015). The post-migrant perspective contests that group identities are “natural,” but recognizes, for example, that ethnicity, migration experience, and sedentariness could well be defining features of an individual positionality. After a brief introduction of the post-migrant perspective as a theoretical approach adapted from critical migration studies, we discuss its recent encounters in urban research and planning.

In the 2000s, members of the performing arts introduced the post-migrant concept. They did not perform only for migrants and their descendants but were more interested in negotiating multiple identity constructions between migration, gender, and desire (Stewart, Citation2017). Writings on the post-migrant perspective from a social science perspective evolved from an artistic and activist confrontation with exclusion and everyday racism by referring to the transitional logic of post-colonial theory (Foroutan, Citation2019b). In this sense, the post-migrant perspective highlights the persistent impact of colonial and Eurocentric pasts and presents, e.g., on transnational mobility as a normality and basis of social exclusion.

The first academic approaches to the post-migrant perspective had an actor-oriented focus and emerged in the 1990s. Scholars began to question the concept of a culturally or ethnically homogenous migrant community as the dominant category. In the introduction to their anthology Post-migration Ethnicity, Baumann and Sunier (Citation1995) wrote about empirical realities in anthropological research that call for de-essentializing ethnic categories. Migrants are seen as experts, each of whom constructs identities around ethnicity, culture, gender and beyond in order to develop everyday agency and escape discriminatory practices. The post-migrant perspective emphasized by Yıldız (Citation2015) does not look primarily at past transnational migration but instead discusses the transformative achievements and recognition that lived migration has brought to society, e.g., the contribution of migrant workers and post-colonial subjects to boosting the West German economy after World War II. The post-migrant perspective also includes descendants of migrants whose only connection to direct migration experiences is through family, partnership, or friendship ties (Yıldız, Citation2015). Their confrontation with migrantization—as a form of Othering—is significant and structures identity formation in the face of everyday racism (Foroutan, Citation2019b).

The post-migrant perspective addresses continuities of Othering as a key challenge. After 2000, migrant descendants born in Germany received full citizenship rights when one parent had been in possession of a permanent residence permit for the previous eight years. This is but one example of the legal barriers to becoming a German citizen beyond ius sanguinis that increase the reproduction of categories marked “foreigner” or “person with a migration background.” A person has a “migration background” if they or at least one parent did not have German citizenship at birth. For a critique of the term and its prevailing focus on ancestry, see Will (Citation2019).

When people are citizens but deviate from an imagined normality because they look or sound different, it feeds into the reproduction of a binary sedentary whiteness and the image of the eternal migrant. The post-migrant perspective, on the other hand, seeks to open up spaces for the representation and participation of racially marginalized people through a network of alliances (Foroutan, Citation2019b). Built on knowledge, empathy and attitudes, these post-migrant alliances emerge as peer group identities between personal, professional and social ties at places such as school, work, trade unions, or political engagement, and go beyond the subject level focused on ethnicity and color (Foroutan, Citation2019b). Given the representation of racially marginalized people and the overcoming of the migrant-native divide, the post-migrant perspective can play a substantial role in research on planning and participation. It helps to challenge participation concepts that rely on formats geared to separating participants according to (ascribed) migration experience or ethnicity, without including empowering formats aligned to race, class, gender, or lifestyle.

The analytical dimension of the post-migrant perspective refers to an understanding of migration as a peripheral perspective on society, i.e., an analytical view of social phenomena seen from the marginalized edges of society (Römhild, Citation2015). This understanding shifts the research focus from ethnic communities toward negotiating identity at the local level, e.g., at a neighborhood scale. The analytical processes of “studying up” and “studying through” are characteristic of reflexive research with a peripheral perspective on migration (Römhild, Citation2015, pp. 42–44). “Studying up” refers to opening up research on migration to international elites or racially unmarked migrants to emphasize the multi-faceted nature of migration as a global normality. “Studying through” is understood as research on non-migrant institutions and milieus of the majority society from a migration perspective. In the sense of studying through, our research examines participatory urban development as a non-migrant societal institution currently seen from the perspective of migration, since participation in the German context is still strongly associated with a white, academic middle class (Friesecke, Citation2017; Kast, Citation2006; Selle, Citation2013).

The post-migrant perspective has recently been introduced to the field of urban research and planning (Jahre, Citation2021; Pilz & Kirndörfer, Citation2021; Wiest, Citation2020). Scholars used it as a starting point to frame migration as a normality of everyday urban life. The existing literature—mainly empirical work—highlights the deconstruction of the migrant-native divide by applying a migration perspective to urban policy programs (Jahre, Citation2021), migrant economies (Räuchle & Nuissl, Citation2019), and everyday urban encounters (Althaus, Citation2018; Pilz & Kirndörfer, Citation2021; Wiest, Citation2020). We seek to connect our research on participatory urban development with the existing literature on the everyday urban of migration and the migrant-native divide, which tackles the stereotypical use of group identities based on ethnicity and race in participation (Beebeejaun, Citation2006, Citation2012). In Germany, the field of urban development and participation rarely addresses race and racism (Chamberlain, Citation2022). The post-migrant perspective allows us to conceptualize exclusion based on the Othering of migrants in participation and create a wider discourse on racialized structures in society, from which urban research and planning can learn. The shift from analyzing the group behavior of individual migrant communities in participation to a critique of Othering and sedentary whiteness as a means of rendering structures of racial exclusion visible makes the post-migrant perspective comparable to efforts of applying Critical Race Theory to British planning (see Gale & Thomas, Citation2018). Besides exposing racialization and migrantization, Critical Race Theory includes imagining an alternative conceptualization of more inclusive participation practices, one that questions the epistemic control of planners and participation practitioners by labeling and assembling groups as different (Beebeejaun, Citation2012).

Research on participation practices that operationalize the post-migrant perspective are rare, in contrast to the standard and highly demanding town hall meetings that tend to favor white, academic, male middle-class voices. These public formats are often disconnected from participation for migrants only, e.g., in storytelling cafés for migrant women (Marquardt & Schreiber, Citation2015). A post-migrant public participation process that uses a doorbell as a “boundary object” (Star, Citation2010, p. 602) contains the following key characteristics (Autor*innen-Kollektiv INTERPART, Citation2021):

Parallel participation: a combination of empowering formats for some and public formats for all, in one event.

Freedom to use different languages, not merely the official language.

Formats distinguished by language, gender, or age that are useful as safe spaces. Results should be integrated later on.

The use of different methods to obtain information from different people, e.g., storytelling, public discussions, small surveys.

Supporting infrastructure such as child care, translation, food, and leisure activities to engage people.

A welcoming environment at typical neighborhood spots to reach out to people. Experiments with different time slots.

The doorbell as an activation tool enhances multi-lingual participation by allowing participants to position themselves on their own terms with respect to language in public places in Berlin and Wiesbaden. As such, it acts as a conversation starter to facilitate in-depth participation with additional narrative elements (Huning et al., Citation2021).

Our analysis emphasizes conceptualizing the in-between as an integral part of the post-migrant perspective. We show how liminal in-between markers help to open up in-between spaces of participation that transcend migrantization in participatory urban development and make participation more inclusive.

Multiculturalism

… local governments are largely responsible for managing the built environment to ensure social order and harmony among ethnically and racially diverse residents. (Fincher et al., Citation2014, p. 4)

Another approach that impacts on how migration is addressed in the urban sphere is multiculturalism. Since the mid-20th century, multiculturalism has influenced national and local policy agendas in Western countries by describing social realities as multi-ethnic or taking account of the colonial past and post-colonial present enriched by migration and progressive globalization (Beebeejaun, Citation2022; Fincher et al., Citation2014). Multiculturalism specifically highlights the co-existence of different ethno-cultural groups as an everyday demographic reality (Wise & Velayutham, Citation2009) and the main focus of policy interventions (Fleras & Elliott, Citation2002). A dynamic discourse on multiculturalism has unfolded and shaped the field of planning and urban research (Amin, Citation2002; Beebeejaun, Citation2012; Sandercock, Citation1998; Uitermark et al., Citation2005).

To understand multiculturalist notions of the normality of migration in participatory urban development, we conceptualize multiculturalism as both normative and assimilative. The normative level draws attention to everyday ethno-cultural difference as a lived demographic reality (Fincher et al., Citation2014), one that seems normal, necessary, and acceptable (Fleras & Elliott, Citation2002). It focuses on the co-existence of different ethno-cultural groups in a given geographic area, such as a city or a neighborhood (Burayidi, Citation2015). Assimilative multiculturalism (Lanz, Citation2007) is characterized by the negation of equality and co-existence among different ethno-cultural groups. It gives prominence to a hierarchic and linear convergence to cultural norms and values of an imagined homogenous sedentary host society, to which migrants (and their descendants) are obliged to adapt.

In the field of planning, multiculturalism has been described as the continuous adaptation of planning practices to ensure access by different ethno-cultural groups traditionally marginalized or discriminated against in the planning process (Burayidi, Citation2015). In this sense, multicultural planning encourages the participation and representation of bottom-up actors from diverse ethno-cultural communities, facilitating social, cultural, and environmental justice (Sandercock, Citation1998). Hence, multicultural planning means negotiating urban landscapes marked by difference in a constant process of recalibrating the many shifting public interests and visions of community (Sandercock, Citation1998). A multicultural planning and participatory approach that first emerged in Berlin and was readily adopted in other German cities involves the so-called neighborhood mothers (Stadtteilmütter) (Marquardt & Schreiber, Citation2015). District offices initiated the training of Turkish and Arab women for voluntary work in their ethnic communities, which in turn entailed instructing other woman on matters of health, education, and child care (Marquardt & Schreiber, Citation2015). In a subsequent stage, these women became networkers and facilitators of information on participation in their neighborhoods. This participation format concentrates solely on migrants and certain marginalized ethnic communities, thereby emphasizing everyday ethno-cultural difference.

Some characteristics of multicultural planning are similar to diversity planning (Raco & Kesten, Citation2018; Schmiz & Kitzmann, Citation2017), which also focuses on urban diversity as a key challenge and planning objective. Contrary to the multicultural planning frame used here, diversity planning centers primarily on the intersection of multiple categories of difference, such as ethnicity, race, class, gender or age, rather than on ethno-cultural difference. In this sense, diversity planning has links to the post-migrant perspective and points to conflicts that set ethno-cultural difference against social justice in urban development (Raco & Kesten, Citation2018). We argue that focusing on ethno-cultural categories reproduces simplistic ideas of homogenous ethno-cultural communities and encourages the Othering of minority groups (Fincher et al., Citation2014). Beebeejaun (Citation2022, p. 2) condemns multiculturalism and diversity for their persistent emphasis on migration and description of migrants as either “former or established,” disregarding the fact that many members of ethnic minorities or Europeans of color have no migration history at all. Diversity, in particular, can obscure long-standing racial and ethnic inequalities by re-asserting and protecting white majority norms, by drawing less attention to race and ethnicity, or by the selection and boundary drawing between good and bad diversity (Beebeejaun, Citation2022). Deconstructing ethnicity with a post-migrant perspective prevents the bias of diversity because it goes hand in hand with a sharp critique of sedentary whiteness as normality.

The post-migrant perspective and multiculturalism take different paths when it comes to interpreting migration-related phenomena in participatory urban development. The post-migrant perspective is about deconstructing the gap between migrants and natives. It looks at hybrid identity formations using in-between spaces to structure inclusive participation beyond ethno-cultural categories. Multiculturalism, on the other hand, highlights everyday ethno-cultural differences that give rise to co-existence and perpetuates the migrant-native divide in participation processes. Due to the novelty of the post-migrant perspective and its less established position in planning and participation research, we expect to find more multicultural ideas on participation in our data than evidence of the post-migrant perspective.

In the following sections we describe data and methods and give a brief overview of the two cases Berlin-Moabit and Wiesbaden-Biebrich. Then, we analyze multicultural and post-migrant notions of normality of migration in the field of participatory urban development and how the two complement each other.

Data and methods

To investigate notions of normality of migration within participatory urban development, we analyzed a total of 42 semi-structured expert interviews in two groups (Flick, Citation2011). We interviewed 23 administrators (first group) and 19 community organizers (second group). We selected administrators from local and state offices based on their professional experience and their current position in participatory urban development. We selected community organizers through a diverse sample, ensuring the inclusion of a broad range of people with experience in participation and various fields such as housing, community management (Quartiersmanagement), refugee rights, women’s rights, social and youth work, education, and antiracism.

In order to take account of post-migrant “studying through” (Römhild, Citation2015), we explored participatory urban development—as a white, academic, middle-class institution—from a migration perspective. Thus, we juxtaposed existing beliefs about the normality of migration among administrators with the perspectives of community organizers. We assumed that we could only study participatory urban development adequately by decentering the dominant white sedentary perspective through studying administrators and community organizers. In order to address post-migrant “studying up,” we interviewed community organizers from ethno-culturally defined migrant associations, but also considered a broad range of actors, organizational structures, and professional fields. In total, we conducted research about 10 community organizations from Berlin and nine from Wiesbaden. These organizations were mostly active in the neighborhoods of Berlin-Moabit and Wiesbaden-Biebrich. Nine of the administrators were from Berlin and 14 from Wiesbaden.

The interviews were part of the first out of three fieldwork periods in the real-world lab research project INTERPART (for the interview guide see Appendix). The aim of the interviews in the INTERPART context was to

gain information about interviewees’ experience about participation in urban development;

enhance trust-building between the INTERPART team and the participation practitioners from the respective administrations and community organizations;

connect and map other key participation practitioners in administrations and community organizations; and

prepare urban experimentation as part of a real-world lab in the two cities.

In our analysis, we only used interview data related to experience about participation in urban development. The interviews were conducted in German in 2018 and 2019. They varied in length between approximately 40 minutes and one hour. Two interviewers conducted 16 interviews, usually with one INTERPART practitioner as a community facilitator who initiated the contact and one INTERPART researcher without prior field access. Using a different set of interviewers made it easier to deal sensitively with the trust, experiences, and individual positionalities of the interviewees (Hitchings & Latham, Citation2020). We took the personal and professional expertise and gender of each interviewer into account in order to create a balanced interview setting and carried out almost all interviews in places chosen by the interviewees (mostly their offices) to ensure a comfortable environment. At the direct request of the interviewees, we conducted two interviews by phone.

We analyzed the interview data via Grounded Theory Coding (Charmaz, Citation2006; Flick, Citation2011) in a combined approach of open and selective coding. In a first step we open-coded interviews and then reorganized the resulting codes, based on engagement with multicultural and post-migrant theory. Our objective was to examine the notions of normality of migration in participatory urban development and to identify the differences among participation practitioners from local administrations and community organizations, and between Berlin and Wiesbaden. Although the comparative analysis of both cities is not a systematic comparison, both case studies served to contextualize the research findings.

Migration as normality: Berlin-Moabit and Wiesbaden-Biebrich

We compare notions of normality of migration in participatory urban devolvement in Berlin and Wiesbaden. We focus on two neighborhoods, Berlin-Moabit and Wiesbaden-Biebrich, because they share a similar population structure and the local community has been actively involved in public participation processes for over 20 years. We will therefore give a short overview of both neighborhoods as case studies.

The German capital of Berlin has a population of 3.7 million and is the core of the monocentric metropolitan region of Berlin-Brandenburg, which has a total population of 6.1 million. In contrast, Wiesbaden, the capital city of the German federal state of Hesse, has a population of 291,000 and belongs to the polycentric metropolitan region of Frankfurt/Rhine-Main, which has a total population of 5.7 million. Berlin-Moabit and Wiesbaden-Biebrich are former inner-city working-class neighborhoods and had a long tradition of labor in-migration. Both have been long-term sites of participatory urban development of the Socially Integrative City program for urban renewal funded by the federal government since 1999 (in the case of Moabit) and 2000 (in the case of Biebrich). Consequently, we interviewed local administrators and community organizers who were highly versed in engaging with and implementing participation. Berlin and Wiesbaden generally use a mix of participation methods, emphasizing town hall meetings and online engagement. The former operates via citywide platforms that provide information on urban development projects and allow for comments but to a lesser extent the contribution of individual ideas. Both cities started using arts-based and narrative methods like podcasts or storytelling cafés and experimented with public participation in languages other than German. Participation practitioners initiated such innovative approaches for the most part separately due to lack of institutionalization and budget allocations for citywide parallel and multi-faceted participation.

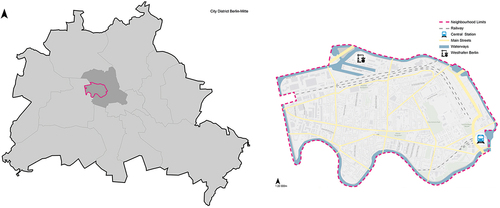

Moabit is a neighborhood in the district of Berlin-Mitte. It has a population of approximately 80,000 people and covers an area of 2.98 square miles. One striking feature of Moabit is its location as an inner-city “island” linked to the surrounding neighborhoods by 17 bridges. Up until 1990, Moabit was part of the outskirts of West Berlin, due to its proximity to the Berlin Wall. Moabit was home to large manufacturing sites such as Borsig, AEG and Siemens, and still harbors some key infrastructure: Berlin’s food wholesaler and the capital’s largest harbor are located in the north, and Berlin’s central station is located in the south-east (see ). Large parts of Moabit are residential areas built in the 19th century, many of them still occupied by working-class people. Due to a steady population growth over the last 10 years and its central location, Moabit has faced rising rents and displacement (Döring & Ulbricht, Citation2017; Haferland, Citation2018).

Figure 1. Location of Moabit in Berlin and in the district of Mitte.

Nineteenth century industrialization in continental Europe caused migrants from the surrounding rural areas to move to Moabit, and migrants have shaped this part of the city ever since. In the 1970s, migrant workers, notably from Turkey, began to settle in Moabit. The so-called Gastarbeiter were hired to fill labor shortages in industries and services in West Berlin. Affordable rents due to the deteriorating building stock and the lack of social infrastructure planning, but also to a discriminatory housing policy based on xenophobia and restrictive citizenship, led to racial segregation of Gastarbeiter in fragmented inner-city areas such as Moabit.

After German reunification in 1990, many East Germans migrated to West German cities in search for better living conditions. At the same time, the Kohl government restricted the right to asylum to reduce transnational migration and to keep jobs and social security primarily for Germans. Also, the absence of a national migration law made migration to Germany challenging (Hinger, Citation2016). After EU enlargement in 2004, many migrants from Poland moved to Moabit. In 2014, when restrictions on EU citizens’ freedom of movement were lifted, a growing number of Bulgarians took residency in this part of the city (Statistical Office Berlin-Brandenburg, Citation2020). After “the long summer of migration” in 2015 (Römhild & Schwanhäußer, Citation2018, p. 345), Syrian migrants also settled in Moabit. Overall, 32% of residents in Moabit are foreign-born compared to 21% in Berlin. Approximately 52% of residents in Moabit have a migration background compared to 36% of all residents in Berlin (Statistical Office Berlin-Brandenburg, Citation2020).

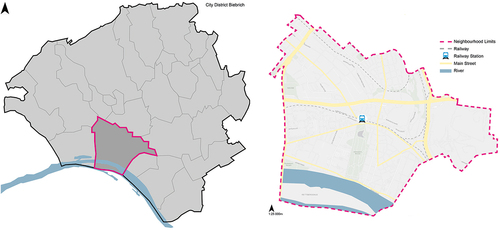

Biebrich lies between Wiesbaden’s Central Business District and the Rhine River. It is home to approximately 38,000 residents and covers 4.98 square miles. In the 19th century, many manufacturers located in the area surrounding the baroque Biebrich Palace. Biebrich and the adjacent City of Mainz then owned one of the largest industrial areas in the Rhine-Main metropolitan region. Germany’s economic recovery and growing population in the wake of World War II saw the beginning of major infrastructure and housing projects in Biebrich. Three new highways were built in the 1960s, leading to increased fragmentation of this part of the city, which lies between factories, railroad tracks, and a landfill for industrial and household waste (see ). To meet the demand of industrial labor, the City of Wiesbaden built two large housing estates—Parkfeld and Gräselberg—in the eastern part of Biebrich, the former planned by modernist architect Ernst May. Today, Biebrich is still an industrial area and home to an industrial park with over 500 jobs in the chemical industry.

Figure 2. Location of Biebrich in Wiesbaden.

During industrialization, laborers migrated from the Prussian province of Hesse-Nassau and the Grand Duchy of Hesse (Struck, Citation1974). Immediately after World War II and until the formation of the Iron Curtain, numerous migrants from the former eastern territories of Germany came to Biebrich (Faber, Citation1974). In the 1960s, many Gastarbeiter—especially from Greece and Turkey—migrated to Biebrich. At the time, they were attracted by industrial labor, cheap housing and a less segregationist part of the city, one that tolerated deviations from white sedentariness. The descendants of Turkish and Greek Gastarbeiter have continued to shape the neighborhood through several stores and a Greek-speaking private high school. After EU enlargement in 2004, many Polish, Bulgarian, and Romanian migrants settled in Biebrich, similar to Moabit. In Biebrich, 27% of the residents are foreign-born compared to 22% in Wiesbaden. Here, 45% of residents have a migration background compared to 39% in Wiesbaden (Office for Statistics and Urban Research Wiesbaden, Citation2021).

The migrant-native divide

In this and the following section, we discuss our findings on notions of normality of migration in participatory urban development. We found a predominance of the multicultural rather than the post-migrant understanding of migration in terms of participation. We assume that the relevance of multiculturalism is based on its long-standing influence on planning policies and participation practices (Beebeejaun, Citation2022; Fincher et al., Citation2014; Uitermark et al., Citation2005).

We first present our findings on multiculturalism, focusing on the reproduction of the migrant-native divide. In the subsequent section we will turn to the emerging post-migrant notion of the in-between. Our analysis showed that multiculturalism in the participation experience of our interviewed administrators and community organizers focused on

co-existence and everyday ethno-cultural difference (Fleras & Elliott, Citation2002; Wise & Velayutham, Citation2009);

boundary drawing that constantly highlights the migrant-native divide; and

migration as a deficit in the sense of assimilative multiculturalism (Lanz, Citation2007).

Interviewees from the administrations stressed the boundaries among different ethno-cultural groups, but also their co-existence as a lived urban reality based on acceptance and everyday negotiation:

The Greeks have never been a big problem, they had a close connection to the local council on the political level. I don’t think we have that with people of Turkish origin yet, that degree of involvement in the local council, at festivals, clubs—especially the men. (Interview 11)

These insights indicate that administrators structured the multicultural notions of normality of migration as ethno-cultural difference (Fleras & Elliott, Citation2002). Various other examples from the administrators showed a similar pattern of homogenous ethno-cultural groups. In the case of the Arab migrant community, for example, participation formats have always been advertised in Arab community magazines because administrators believed that they address the entire community (Interview 17). In general, administrators saw distinctive ethno-cultural entities as the key to organizing participation in the context of migration. Our interviewed community organizers saw the same distinctions. When it came to participation, however, they made an effort to address each group equally (interviews 8, 14, 18, 20).

This focus on boundary drawing between ethno-cultural groups likewise led to a reproduction of the migrant-native divide (Foroutan, Citation2019b; Römhild, Citation2017). In this sense, we did not see ethno-cultural differences as interactions between equal partners, but as the application of exclusionary hierarchies, because our interviewees described the distinction between the migrantized “other” and an imagined sedentariness as intrinsically “normal” (Ahmed, Citation2012). The following statement by an administrator provides an example of such a distinction:

With regard to refugees or perhaps migrants as a whole, I think their points of view, experiences and ideas, and perhaps also things that work within their community are often not perceived by the other side. It’s always viewed from the side of the host society, what do they have to learn, right? So, they tend to be seen as deficient. … That’s probably also true for the most part, but there is at least another perspective, the people who bring something with them. (Interview 10)

The participation practitioners discussed the migrant-native divide as the predominant notion of normality of migration, regardless of its positive or negative contextualization. We identified numerous ways of Othering based on the divide between migrants and natives (Interviews 6, 23). Representatives of community organizations also talked about the Othering they had experienced, e.g., from street-level bureaucrats who treated them disrespectfully once their accent had labeled them as migrants (Interview 16). Only a few of these interviewees followed the drawing of the migrant-native divide similar to the administrators (Interview 9). Despite the heterogeneity of our interview partners, our findings showed that the migrant-native divide impacted how actors structured the field of participatory urban development. The migrant-native divide put Othering center stage, highlighted differences and consequently made participation less inclusive for a vast number of people. Many of our interviewees saw the (ascribed) migration experience, but also religion, lifestyle, or color as deviating from the socially constructed norm of white sedentariness (Ahmed, Citation2012; El-Tayeb, Citation2011). Such forms of racial marginalization hinder participation practitioners to organize more inclusive participation processes.

Our analysis of the divide between migrants and natives also brought forth notions of migration as a deficit with reference to assimilative multiculturalism (Lanz, Citation2007). The interviewed administrators not only stressed unequivocal ethno-cultural differences, but underlined the need to assimilate ethno-cultural groups they perceived as backward, that is, as authoritarian and deviant vis-à-vis the imagined democratic and regulated majority society. Administrators linked the negative, authoritarian habitus of migrants with reference to participation to an ascribed origin, identified as a non-democratic country. Learning and appreciating participation was therefore difficult if not impossible for migrants (interviews 2, 17). The interviewed administrators described migrants as deviant in the context of driving and running small businesses and cultural festivities (interviews 11, 12). By migrantizing people, administrators and community organizers construed authoritarian or deviant ascriptions. Our interviewed administrators and officials of community organizations called for assimilation, demanding a process of linear convergence to cultural norms they define, which see migrants and their descendants as Others compared to an imagined homogenous sedentary host society (El-Tayeb, Citation2011).

The interviewees understood multiculturalism as exclusionary difference in the migrant-native divide. The interviewed administrators in Wiesbaden made more statements about Othering than their counterparts in Berlin. Othering was less common in interviews with community organizers in both cities. Interviews showed that multiculturalism prevailed in normalizing ethno-cultural differences. We identified assimilationist notions referring to the migrant-native divide in interviews with administrators and community organizers in both cities. While administrators in Berlin and community organizers in Wiesbaden discussed migrant authoritarianism, administrators in Wiesbaden linked deviation with migration.

“In-between” in participation

Interviewees discussed the post-migrant “in-between” as a liminal form of identity formation in ideas about the normality of migration, as we show below (Bhabha, Citation2004). We identified the emerging “in-between” in statements on migration by our interviewees that did not emphasize ethno-cultural belonging and sedentariness as the distinguishing features of participation, but instead stressed a departure from the “either/or” logic of origin. Drawing on the interview material, we analyzed class, milieu, neighborhood, and age as emic codes that function as in-between markers to open up post-migrant in-between spaces of participation.

Although these post-migrant moments were rare in the statements of our interviewees, they gave a first impression of how participation can be designed more inclusively without essentializing the migrant-native divide. The interviewed administrators stressed class and milieu as meaningful identity markers to ensure inclusive participation beyond ethno-cultural ascriptions of migration or the migrant-native divide. Interviewees of the community organizations, on the other hand, referred primarily to age and neighborhood as defining in-between markers.

Class as an “in-between”

The interviewed administrators discussed social aspects to describe the in-between that paved the way for participation beyond ethno-cultural ascriptions of migration. One interviewee remarked on the importance of participating in a culturally sensitive manner, but also stressed class-based commonalities:

On the one hand, approaching culture more sensitively and being aware that we are talking about numerous cultural groups. At the same time, however, we have to take this social component into account. And then also allow for difference. I think that’s an important point to consider. (Interview 3)

A shared class-based identity in participation beyond ascriptions of ethnicity and culture made it possible to avoid migrantization and the exclusionary “either/or” logic of the migrant-native divide. This approach transformed participation into a hybrid and liminal in-between space, where negotiating class was a way of preventing Otherness. The liminal in-between space enables participants to respond to a class-based identity and at the same time to an identity based on their migration experience or ethnic belonging. It furthermore recognizes intersecting mechanisms of exclusion, e.g., the overlapping discrimination of working-class participants who are simultaneously people of color or migrants. The agency of participants to position themselves in relation to class leads to a class-based subjectivation that decenters the interpretative authority of sedentary whiteness (see Beebeejaun, Citation2022).

Our interviewees agreed that the focus on class addresses a pressing problem of participation, namely, that those who tend to be absent from participation are poor residents with low education rather than migrants (interviews 2, 5, 8). Although class-based inequalities are difficult to redress through area-based participation, those who are active in participatory urban development and who acknowledge class and the involvement of working-class people could make a difference by promoting capacity-building and resource allocation in their local interests.

Milieu as an “in-between”

The concept of milieu refers to a social group or lifestyle collective that exhibits a high degree of social and cultural uniformity, e.g., in the fields of consumption, religion, or political opinion (Diaz-Bone, Citation2004). The interviewed administrators addressed milieu as key to getting people involved in participation processes without highlighting ethnic communities or reproducing the gap between migrants and natives. Hence, participation by milieu mobilizes people with similar lifestyles and comparable incomes, education, values, and consumption patterns. Administrators in both cities used milieu analysis based on Sinus Milieus (vhw - Federal Association for Housing and Urban Development, Citation2021) to obtain a demographic and socioeconomic understanding of the kind of people living in a neighborhood, and their attitude to participation. The Sinus Milieus concept envisages eleven overlapping milieus ranging from liberal intellectual to traditional or precarious milieus (vhw - Federal Association for Housing and Urban Development, Citation2021). The Sinus Institute invented this social model in the 1980s and combined socioeconomic status with a canon of values to conduct market research and inform political consulting about societal trends (Erdem, Citation2013). The Sinus Milieus approach has been criticized for its lack of scientific transparency and the validity of its data collection, which is inconsistent with its aspiration of exclusive commercialization (Diaz-Bone, Citation2004). Also, it reflects poorly on the influence of researchers and interviewers on data collection and the social constructiveness of survey data results (Erdem, Citation2013).

Based on milieu analysis, local administrations opted for participation formats with low access barriers, e.g., tables for regulars or storytelling cafés, to include milieus that are less visible in participatory urban development (Interview 4). Our interviewees credited the milieu approach for its ability to organize participation according to ethno-cultural similarities or migration experience and to call attention to shared social realities and the intersecting experience of inclusion and exclusion, as one interviewee described:

I am always careful. What is a migration background? What does it have to do with culture? How is that related to their economic situation, or is it to milieus, or to tight housing and larger families? (Interview 1)

The milieu approach makes it possible to use a multitude of small hubs of everyday identity formation such as home-making, family networks, work experience, education, or consumer interests, all of which ensure liminal in-between spaces beyond the “either/or” of origin and the migrant-native divide.

Education, as a key aspect of belonging to a certain milieu, strongly affects how people accumulate what Bourdieu (Citation1984, p. 23) calls “cultural capital” and how these people are positioned in the social field. A broad range of the interviewed administrators and community organizers declared that the more educated people are, the more likely this milieu is willing to participate (interviews 2, 4, 8, 19). Some administrators stated that education carries far more weight than ethnicity or culture when it comes to participation (Interview 10).

Although actors using the milieu approach are able to connect day-to-day experiences, the milieu approach itself has been criticized as less suitable for inclusive participation because it fails to acknowledge structural racism. Erdem (Citation2013) shows that the Sinus Milieus concept associates the experience of racial exclusion only with precarious and disadvantaged milieus but dismisses the idea of racism as a structural driver of inequality. This relativistic understanding of racial exclusion that fails to conceptualize Othering adequately weakens the Sinus Milieus considerably as an in-between marker in terms of participation.

Interviews with participation practitioners from community organizations revealed that they were not enthusiastic about the milieu approach. In Berlin, for example, community organizers worked with the Sinus Milieus to invite people to participate in urban development. The fact that these interviewees knew where certain milieus lived, however, did not promote inclusive participation (Interview 19). Although the administrators spoke of inclusive participation formats based on milieu analysis, they could not provide the resources and training to implement these formats and organize people on a regular basis, for example, from the precarious milieu. As a result, community organizers concluded that the milieu approach was unsuccessful.

Addressing people by milieu is another method of organizing participation. Here, in order to overcome Othering and the migrant-native divide, our interviewees did not distinguish between imagined homogenous ethno-cultural groups or between migrants and natives.

The neighborhood as an “in-between”

“We as neighbors” (Interview 23) was a common phrase that interviewees witnessed in participation formats in the context of migration. A shared local or neighborhood identity—as a lived reality—functioned as an in-between marker because it avoided migrantization and ethno-cultural categorization on the one hand and sedentariness on the other. Both residents and people who work in the neighborhood identify themselves with the area, which is a useful basis for inclusive participation. Contrary to milieu, neighborhood is a loose concept, one that is more accessible for participants than milieu and conveys values that are less binding for those who work or live there. Our interview findings suggested that people who are primarily seen as neighbors rather than migrants became potential partners in urban development, as the following quote from a community organizer indicates:

It’s very good to just talk a little bit about the neighborhood, my neighbors … Then you create a bridge to get away from “you’re different and I’m different, let’s get together.” That’s more likely to create barriers than “you’re my neighbor, I’m your neighbor, we don’t know each other yet, let’s get to know each other.” (Interview 21)

The neighborhood as an in-between marker influences inclusive identity formation in the participatory involvement of people who share the challenges and expectations of their immediate urban environment. One problematic aspect of the neighborhood focus was the hidden demand that only actors from within the neighborhood like residents and local participation practitioners can solve social problems through inclusive participation (Marquardt & Schreiber, Citation2015). We think that participation practitioners cannot solve social problems such as exclusion based on ethnicity or race at the local level alone. Such problems also need to be addressed on the national or supra-national scale.

Community organizers were aware of the potential for participatory urban development at that neighborhood level. One interviewee, however, mentioned that even when people were directly affected, they often failed to participate (Interview 14). We believe that participation practitioners generally tend to have overly optimistic expectations. Following Hartmann (Citation2012), we highlight the fatalistic rationality of “I don’t participate” and its omnipresence in every participation process. The fact that participation practitioners often fail to recognize why people abstain from participating is a concern for us. For many, organizing day-to-day activities are a permanent struggle leaving little room for any form of participation.

We saw that a shared neighborhood identity created a sense of belonging for people living or working in the same urban environment. People in the neighborhood were able to transcend migrantization. The local focus, however, cannot solve the structural inequality that prevents people from participation.

Age as an “in-between”

Age as another in-between marker of identity formation helps to decenter the migrant-native divide in participation. Interviewees from community organizations said that a growing number of young Germans defy being positioned in an “either/or” logic of origin or migration background. As participants in urban development, they see their shared generational experience as far more important when it comes to inclusive participation (interviews 7, 13).

Maybe we don’t even see that anymore. If I’m trying to do anything now, it doesn’t even occur to me to ask how do I reach the migrants. I just ask myself how I can reach the kids. (Interview 15)

This quote was remarkable in that it showed how participation practices—and notably youth participation—were rapidly shifting from a multicultural understanding that focuses solely on migrants to a post-migrant understanding of social relations. Participation strategies that used age-related identities to address people opened up in-between spaces of participation that challenged the hegemony of ethnicity and migration backgrounds.

Although the interviewed administrators and community organizers mentioned seniors as a group with shared experience, interests, and identities, they gave few examples where age-related activities function as an in-between. Community organizers argued that a lack of exchange and language barriers ultimately left participants at a disadvantage (Interview 9). Participation practitioners need to address multiple types of discrimination of older participants based on age and the migrant-native divide. Practitioners who design participation formats could remedy discrimination with readily available translation assistance, which in turn would make positionalities in participation transparent. Some interviewed administrators merely stated the importance of participation formats in locations such as kindergartens and retirement homes in order to reach certain age groups (Interview 22). Other administrators did not see participation structured by age as a successful method of transcending the migrant-native divide, but stressed that generational experiences are strongly influenced by class relations, insights that participation practitioners should acknowledge in public participation (Interview 5). In conclusion, we consider age as an in-between marker a good starting point for more inclusive participation without referencing the migrant-native divide.

Gender and race as an “in-between”

Our interviewed community organizers rarely mentioned gender and race as in-between markers to open up liminal in-between spaces, which are therefore not fully comprehensive codes with theoretical data saturation. However, we found that administrators referred to gender in notions of normality of migration in a general sense only, e.g., support for gender-sensitive language and formats such as storytelling cafés. Community organizers highlighted events organized by women to empower working-class women by encouraging a participatory exchange of ideas on how to advance inclusive neighborhood development (interviews 8, 9, 19). Despite the considerable success of feminist thought in the German planning system (see Huning, Citation2020), we did not find any knowledge transfer or even an intersectional perspective that tackled racial inequality as passionately as patriarchal exclusion. This deficit could be due to the difficulty of administrations to adapt feminist or gender-related approaches to racialization and migrantization or to the persistent idea in Germany that racism is a personal attitude rather than the outcome of structural inequality (Espahangizi et al., Citation2016). Consequently, our interviewed administrators failed to see the experience of racial discrimination as significant in terms of overcoming the migrant-native divide in participation formats. Only community organizers in Berlin described such an in-between marker based on active resistance to racial discrimination. We recommend that practitioners apply race as a category in participation to highlight shared experiences of and collective actions against racial discrimination. In turn, such experiences and actions could lead to a reshuffling of peer group identities characterized by attitude rather than markers such as ethnicity, nationality, or (ascribed) migration experience (Foroutan, Citation2019b).

Conclusions

Our analysis of notions of normality of migration in participatory urban development contains three major points. First, practitioners in participatory urban development still prioritize the multicultural understanding of notions of normality of migration. Although we expected largely essentializing notions of the migrant-native divide, they were in fact diverse. Most prominent was the reproduction of the exclusionary divide between migrants and natives by participation practitioners (Foroutan, Citation2019b; Römhild, Citation2017). This divide unfolded its power through a particular focus on the fundamental otherness and distinct characteristics of “the migrant.” Furthermore, we identified the normality of everyday ethno-cultural difference that highlights the co-existence between migrant groups according to ethnicity, on the one hand, and between migrants and natives, on the other (Fleras & Elliott, Citation2002; Wise & Velayutham, Citation2009). Finally, we identified assimilative multiculturalism, which treats migration as a deficit (Lanz, Citation2007). We are aware that the post-migrant perspectives we hoped to describe in our analysis appear less frequently than multicultural notions of normality of migration and see the lack of post-migrant findings as the result of participation practitioners’ persistent targeting of migrants in participation formats. We also see the need to take a closer look at Othering and similar forms of racial exclusion. At the same time, we believe that the multiculturalist understanding of everyday ethno-cultural difference shares common ground with the post-migrant perspective. Both multiculturalism and the post-migrant perspective acknowledge transnational mobility as normal and as an achievement in migration societies, but stress different aspects of migration (Yıldız, Citation2015). Multiculturalism emphasizes the co-existence of homogenous ethno-cultural groups as a result of migration (Fleras & Elliott, Citation2002), whereas the post-migrant perspective accentuates identity formations that go beyond origin and ethno-cultural categories.

Second, the analysis of interviews with administrators and community organizers on notions of normality of migration enabled us to reconstruct the obstacles to a post-migrant perspective in participatory urban development—an institution still dominated by a white, academic, middle-class outlook. Our findings show that participation can be conceptualized along the liminal in-between markers of class, milieu, neighborhood, or age, an approach that allows participation practitioners to create spaces of participation where people are addressed beyond the migrant-native divide and ethnic categorizations such as Turkish, Polish, or German. The interviewed administrators in both cities highlighted social categories such as class and milieu as liminal markers that create in-between spaces for participation without focusing exclusively on the migrant-native divide. Although participation that includes class-based identities avoids migrantization, participation practitioners should acknowledge that people from low-income households do not participate in public events, something that calls for locally adapted participation formats in order to reach them. Community organizers argue that specifically at the local level, the sense of belonging to a neighborhood, a shared everyday urban environment, encourages people to participate. These area-based approaches attempt to locate problems where they are most visible, albeit social exclusion issues cannot simply be solved on the ground but require efforts on different scales (Marquardt & Schreiber, Citation2015). When practitioners make use of neighborhood ties as an in-between marker to open up spaces of participation, they should be careful not to ignore structural exclusion or questions of distributive justice. Community organizers also stressed age as another important in-between marker. The reality of young urban people living in a migration society shows that common generational experience is valuable and has a stronger impact than the “either/or” logic of origin.

Third, scientific engagement with the post-migrant perspective in planning and participation is still in the early stages and focuses mainly on the discursive deconstruction of the migrant-native divide (Pilz & Kirndörfer, Citation2021; Wiest, Citation2020). Our research applied the post-migrant perspective beyond the deconstruction of ethnicity and showed that participation practitioners see liminal in-between markers such as class, milieu, neighborhood, and age as opportunities to structure spaces of participation. Markers are necessary since participation practitioners must somehow address participants in an event beyond the binaries of migrant and native. Age, for example, serves as a door opener to in-between spaces for participation, where young adults can position themselves freely—if they want to at all—as migrant or native, or as German, Turkish, or Polish.

If inclusive participation processes are to be successful, participants must be able to feel that they are not simply being addressed along the excluding “either/or” logic of the migrant-native divide. Instead, they should have the opportunity to choose or leave open whether they wish to be addressed as a neighbor, a working-class woman or a teenager, or all of them at once. In other words, participation practice in this sense would allow participants to choose between identities but also to recognize the intersecting mechanisms of exclusion and leave room for empowering marginalized participants. We believe that post-migrant participation practice can only be considered successful if it manages to reflect on the decentering of migration and the unlearning of a structural exclusion that treats white privilege as a point of reference.

Finally, we recommend that planners and other participation practitioners embrace the advantages and implications of the post-migrant perspective for participation processes. Participation formats based on a post-migrant understanding are inclusive by virtue of their ambiguity: sensitive and open to the use of intersecting in-between markers rather than organized by participation practitioners separately for migrants, natives, or by ethnicity. We therefore suggest using parallel participation designs that combine empowering formats aligned to class, milieu, neighborhood, or age with public formats for all, organized in one event. It is vital that participation practitioners integrate the results of these parallel designs into the final stages of the event.

Given that the German government has begun to recognize migration as a lived reality, planners in Germany must be better equipped to reflect on race relations and white privilege in order to translate them into participation formats that exceed tokenism (Arnstein, Citation1969; Beebeejaun, Citation2006; Gale & Thomas, Citation2018). Planners and other participation practitioners need to be aware of their own positionalities when it comes to racialization and migrantization, and how these influence the output of participation formats (Rose, Citation1997). Participation practitioners’ collaboration with community organizations experienced in anti-racism work and the application of in-between markers in participation can facilitate their engagement with excluding ascriptions of race or migration.

In addition to the need for more effective training of participation practitioners, there is demand for structural change that not only focuses on migration and the needs of individual ethnic communities and their cultural specificity in participation, but also on policies that address basic needs to counter racial exclusion (Beebeejaun, Citation2012). The recently updated guidelines for citizen participation could form the backbone of such change (for Berlin, see SenSW, Citation2021; for Wiesbaden, City of Wiesbaden, Citation2016). Up to now, however, guidelines for citizen participation have not addressed racial exclusion directly and lack monitoring by locally elected politicians. The post-migrant perspective or lack of it shows that the fight of local planners and community organizers against racism in participatory urban development must be continued, to change participation practices vis-à-vis the planning system. Raising awareness should take center stage if the Othering of migrants and the constant reproduction of the migrant-native divide is to be overcome. It could well be one of the most prominent issues in the German planning system in the context of structural racism.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the valuable comments of the two anonymous reviewers and the handling editor which were constructively challenging and encouraging. We also thank Henning Nuissl and Sunniva Greve for their feedback during the writing process, as well as Michael Frings for his hospitality during field work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Robert Barbarino

Robert Barbarino is a PhD student at the Applied Geography and Spatial Planning Research Group at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Germany. His research investigates migration and racial exclusion in public participation and the use of real-world labs as transformative and transdisciplinary approaches in urban development.

Hanna Seydel

Hanna Seydel is a PhD student in Urban and Regional Sociology at the Department of Spatial Planning at TU Dortmund University, Germany. Her research interests are storytelling, feminism, and conflict in participatory planning processes. She is further interested in methodological discussion about engaged research and science communication in urban studies and planning research.

References

- Ahmed, S. (2012). On being included: Racism and diversity in institutional life. Duke University Press.

- Althaus, E. (2018). Sozialraum Hochhaus: Nachbarschaft und Wohnalltag in Schweizer Großwohnbauten [Social space high-rise building: Neighborhood and everyday living in Swiss large residential buildings]. transcript.

- Amin, A. (2002). Ethnicity and the multicultural city: Living with diversity. Environment & Planning A: Economy & Space, 34(6), 959–980. https://doi.org/10.1068/a3537

- Arnstein, S. R. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35(4), 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225

- Autor*innen-Kollektiv INTERPART. (2021). Beteiligung interkulturell gestalten: Ein Lesebuch zu partizipativer Stadtentwicklung [Designing intercultural participation: A reader on participatory urban development]. jovis.

- Baumann, G., & Sunier, T. (Eds.). (1995). Post-migration ethnicity: De-essentializing cohesion, commitments and comparison. Het Spinhuis Publishers.

- Beebeejaun, Y. (2006). The participation trap: The limitations of participation for ethnic and racial groups. International Planning Studies, 11(1), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563470600935008

- Beebeejaun, Y. (2012). Including the excluded? Changing the understandings of ethnicity in contemporary English planning. Planning Theory & Practice, 13(4), 529–548. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2012.728005

- Beebeejaun, Y. (2022). Whose diversity? Race, space and the European city. Journal of Urban Affairs, 46(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2022.2075269

- Bhabha, H. K. (2004). The location of culture. Routledge.

- Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste. Harvard University Press.

- Burayidi, M. A. (Ed.). (2015). Cities and the politics of difference: Multiculturalism and diversity in urban planning. University of Toronto Press.

- Castro Varela, M. D. M., & Mecheril, P. (2010). Grenze und Bewegung: Migrationswissenschaftliche Klärungen [Border and movement: Clarifications in migration studies]. In P. Mecheril, M. D. M. Castro Varela, İ. Dirim, A. Kalpaka, & C. Melter (Eds.), Migrationspädagogik (pp. 25–53). Beltz.

- Chamberlain, J. (2022). Wilhelmsburg is our home! Racialized residents on urban development and social mix planning in a Hamburg neighbourhood. transcript.

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. SAGE.

- City of Wiesbaden. (2016). Wiesbadener Leitlinien für Bürgerbeteiligung [Wiesbaden guidelines for citizen participation].

- Dahinden, J. (2016). A plea for the “de-migranticization” of research on migration and integration. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 39(13), 2207–2225. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2015.1124129

- Diaz-Bone, R. (2004). Milieumodelle und Milieuinstrumente in der Marktforschung [Milieu models and milieu instruments in market research]. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 5(2), Art. 28.

- Döring, C., & Ulbricht, K. (2017). Gentrification hotspots and displacement in Berlin: A quantitative analysis. In I. Helbrecht (Ed.), Gentrification and resistance: Researching displacement processes and adaption strategies (pp. 9–35). Springer.

- El-Tayeb, F. (2011). European others: Queering ethnicity in postnational Europe. Difference incorporated. University of Minnesota Press.

- Erdem, E. (2013). Community and democratic citizenship: A critique of the sinus study on immigrant milieus in Germany. German Politics and Society, 31(2), 93–107. https://doi.org/10.3167/gps.2013.310208

- Espahangizi, K., Hess, S., Karakayalı, J., Kasparek, B., Pagano, S., Rodatz, M., & Tsianos, V. (2016). Rassismus in der postmigrantischen Gesellschaft: Zur Einleitung [Racism in the post-migrant society: An introduction]. Movements Journal for Critical Migration and Border Regime Studies, 2(1), 9–23.

- Faber, R. (1974). Die letzten fünfzig Jahre [The last fifty years]. In R. Faber (Ed.), Biebrich am Rhein: 874–1974: Chronik (pp. 143–178). Seyfried.

- Fincher, R., Iveson, K., Leitner, H., & Preston, V. (2014). Planning in the multicultural city: Celebrating diversity or reinforcing difference? Progress in Planning, 92, 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progress.2013.04.001

- Fleras, A., & Elliott, J. L. (2002). Engaging diversity: Multiculturalism in Canada. Nelson Thomson Learning.

- Flick, U. (2011). An introduction to qualitative research. SAGE.

- Foroutan, N. (2019a). Die postmigrantische Gesellschaft: Ein Versprechen der pluralen Demokratie [The post-migrant society: A promise of plural democracy]. transcript.

- Foroutan, N. (2019b). The post-migrant paradigm. In J.-J. Bock & S. Macdonald (Eds.), Refugees welcome? Difference and diversity in a changing Germany (pp. 142–167). Berghahn.

- Friendly, A. (2019). The contradictions of participatory planning: Reflections on the role of politics in urban development in Niterói, Brazil. Journal of Urban Affairs, 41(7), 910–929. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2019.1569468

- Friesecke, F. (2017). Aktivierung von beteiligungsschwachen Gruppen in der Stadt- und Quartiersentwicklung [Activating participation of weakly involved groups in urban and neighborhood development]. In H. Bauer, C. Büchner, & L. Hajasch (Eds.), Partizipation in der Bürgerkommune (pp. 117–138). Universitätsverlag.

- Gale, R., & Thomas, H. (2018). Race at the margins: A critical race theory perspective on race equality in UK planning. Environment & Planning C Politics & Space, 36(3), 460–478. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654417723168

- Haferland, E. (2018). Gentrifizierung - eine Frage des Lebensstils? Eine Untersuchung am Beispiel der Berliner Stadtteile Wedding und Moabit [Gentrification—A matter of lifestyle? An investigation using the example of the Berlin districts Wedding and Moabit]. Tectum Verlag.

- Hartmann, T. (2012). Wicked problems and clumsy solutions: Planning as expectation management. Planning Theory, 11(3), 242–256. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095212440427

- Häußermann, H., Läpple, D., & Siebel, W. (2007). Stadtpolitik [Urban politics]. Suhrkamp.