?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This research examines the influence of address style (direct, no address) and narrative voice (first-person, third-person) on the feeling of being pressured by a public service announcement about work stress in two sequential studies. The results of a choice-based conjoint analysis show that persuasive messages designed with a first-person narrative voice and direct address tend to pressure recipients. Results of a between-subjects online experiment suggest that this feeling increases subjects’ behavioral intentions to prevent stress when people interact parasocially with the displayed character. Both direct address and first-person narrative voice led directly to reduced behavioral intention to prevent stress.

Introduction

Public service announcements (PSAs) are a common means for communicating health information and promoting health-related beliefs, attitudes, or behaviors. Because PSAs are often directive, audience members may experience that their freedom is threatened, which, in turn, may lead to their refusing to heed the recommendations and, eventually, result in reactance. This is especially true for high-pressure communicators (Brehm & Brehm, Citation1981; Wicklund, Citation1974). PSA designers put much effort into message design because of the critical role such messages play in fostering healthy outcomes. Examples include verbal and visual communication, such as the presentation of the protagonist, the style of address, and the choice of the grammatical person. The protagonist can, for example, address audiences verbally while looking directly at them (Auter, Citation1992). In addition, the speaker in the message may vary (Genette, Citation1990). The physical and verbal address is expected to foster parasocial interaction (PSI) (Hartmann & Goldhoorn, Citation2011), while a first-person narrative voice increases identification with the protagonist (Chen & Bell, Citation2021). Both concepts imply that audience members develop an emotional connection with these media characters (Cohen et al., Citation2019). In turn, the message processing is more favorable because the audience is more likely to accept the position of the displayed character. Thus, direct address and first-person narrative voice are essential contributors to persuasive outcomes as they increase PSI and identification (e.g., Hartmann & Goldhoorn, Citation2011; Igartua & Rodríguez-Contreras, Citation2020).

To help design more effective PSAs, we investigate how these characteristics influence the feeling of being pressured by a PSA. As we are interested not only in the effects of one narrative characteristic but also in the most effective combination, we conducted a choice-based conjoint analysis (Study 1). The advantage of this approach is that the characteristics are not interpreted in isolation but can be compared relatively (Brusch et al., Citation2002); however, only a single-item measure can be used as the dependent variable. Therefore, we focus on “feeling pressured” by a PSA as an antecedent of reactance. As inferences are limited due to the conjoint design, an online experiment is conducted to investigate the impact of narrative voice and style of address on identification and parasocial interaction as well as on persuasive outcomes (Study 2).

Feeling pressured by PSAs

PSAs are messages designed to raise awareness about problems that are assumed to be of major importance to the public. In many cases, PSAs intend to not only inform the public but also to influence beliefs, attitudes, or behaviors (O’Keefe & Reid, Citation1990). In health communication, PSAs are a common means for communicating health information and promoting health-related beliefs, attitudes, or behaviors. These recommendations can provoke either the recipient’s acceptance or rejection. The latter occurs when recipients perceive PSAs as being too directive because the message exerts pressure for change to conform to the PSA’s recommendation. When recipients feel as if their autonomy is threatened by a health-related message, they may reject the advice (Shen et al., Citation2018). “High-pressure communicators” are especially likely to be perceived as threats (Brehm & Brehm, Citation1981; Dillard & Shen, Citation2005; Wicklund, Citation1974), and this may reduce the effectiveness of persuasive health-related messages or even lead to reactance (Dillard & Shen, Citation2005). For example, Quick et al. (2011) found that language designed to pressure individuals into adherence should not be used when attempting to convince audience members to join a donor registry as it increases a perceived threat to their freedom. Rather, non-freedom threatening messages including statements stressing that joining a donor registry is an individual choice should be used. Thus, to reduce the risk of such effects, researchers recommend that a persuasive message should be clear in advocating for the recommended behavior while avoiding cues that pressure or threaten recipients’ freedom of choice (Quick & Stephenson, Citation2008; see, for an overview, Reynolds-Tylus, Citation2019).

One strategy to prevent defensive reactions to PSAs is to increase viewers’ engagement with the characters displayed. If audience members can interact with or relate to these characters, positive associations with the displayed beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors of the media character may be fostered (see, for example, Hoeken & Fikkers, Citation2014; Wei et al., Citation2019). Engagement with media characters is often investigated in terms of PSI (Klimmt et al., Citation2006) or identification (Cohen, Citation2001). Both of these mechanisms can be triggered through different message design features that will be elucidated in the following section.

Persuasive effects of direct address and first-person narrative voice

An important trigger for PSI is the media character’s verbal or physical address of the audience as this creates the impression of an interpersonal encounter (Auter, Citation1992). The verbal address refers to the way the media character talks to the audience, for example, by using the word “you” instead of “one.” Physical address involves the visual presentation. The character may be presented frontally to the camera or in a lateral position (Hartmann & Goldhoorn, Citation2011). The direct verbal and physical address of the audience indicates conversational engagement that should establish a face-to-face relationship between the audience and the media character. Ultimately, PSI is increased. When a viewer interacts parasocially with a character, the illusion of reciprocity and interpersonal contact is fostered, creating a sense of intimacy, friendliness, and companionship (Cohen et al., Citation2019). The character may be seen as a (para-)friend who offers the audience member advice. This activates fewer defensive reactions because when a persuasive message is transmitted through a media character who is perceived to be a peer, they are also perceived as less authoritative and less controlling (Burgoon et al., Citation2002; Moyer-Gusé, Citation2008).

Since identification requires some kind of merging of the audience members’ and the media character’s views, the direct address should not affect the intensity of identification (Cohen et al., Citation2019). Instead, identification is expected to be heightened through a first-person narrative voice where a protagonist describes their personal experience. A third-person narrative is one told by a narrator who relates the story of a protagonist, and this has been shown to impede perspective-taking (see, for an overview, Chen & Bell, Citation2021). Identification occurs when audience members imagine themselves as one of the story’s characters, lose self-awareness, and temporarily take on the perspective of this character (Cohen, Citation2001). Studies have shown that, when a narrative features a character who represents one’s position on a topic, the tendency to agree with the character is increased. This, in turn, fosters positive associations with the displayed beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors of the media character, which should reduce refusal of the recommendations in the message (Shen et al., Citation2018).

Research interest study 1

In the first study, we investigate how characteristics of a PSA (narrative voice and address style) influence the feeling of being pressured by the message. Although previous studies have shown that direct address and first-person narrative voice are beneficial for persuasive outcomes because they increase PSI and identification respectively, the question of which is the most beneficial combination of these features remains open. Therefore, we conducted a choice-based conjoint analysis. We propose that health messages with direct verbal and physical address promote a lower feeling of being pressured than messages without direct address (H1). We assume that health messages with a first-person narrative voice result in a lower feeling of being pressured than messages with a third-person narrative voice (H2). We hypothesize that messages combining direct address and a first-person narrative voice lead to lower feelings of pressure than all other combinations (H3). We examine which of the characteristics plays a more critical role in the activation of feeling pressured by a PSA (RQ1).

Method study 1

Research design and procedure

The study employed a 2 × 2 factorial within-subject design with the two characteristics narrative voice (first- vs. third-person) and address style (direct bodily and verbal address vs. no address). As it is important to indicate the most effective combination of these narrative characteristics, a choice-based conjoint analysis was conducted. With this decompositional method, the overall judgment can be divided into the partial contribution of each characteristic to the stimuli (Orme, Citation2010).

Participants were recruited via student and professional online platforms and through university e-mail distribution lists. In the online questionnaire, participants first answered questions about their general health and their stress levels. In the subsequent choice tasks of the conjoint design, the participants were asked to indicate which of two simultaneously presented health-campaign posters about stress put them under more psychological pressure (see measures). The final part of the survey asked questions regarding the posters in general, stress management, as well as sociodemographic factors.

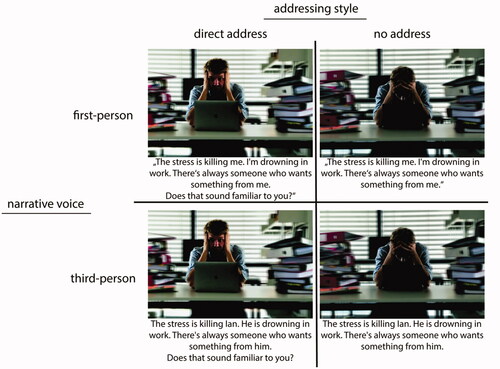

Stimulus material

The stimuli were designed in the style of a PSA poster about stress reduction in the workplace (see ). On the posters, the two characteristics—narrative voice and address style—were manipulated, resulting in four different stimuli: first-person and direct address, first-person and no address, third-person and direct address, as well as third-person and no address.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the manipulation of address style and narrative voice in the four stimulus versions.

Measures

Feeling pressured

Due to the design of the choice tasks, participants were asked one question to assess their defensive reaction to each poster’s combination of stimuli. For the choice tasks’ question, we asked “Which poster makes you feel like you’re being put under more pressure?”

Control variables

As control variables, current professional situation, level of employment, education, sex, and age were assessed.

Participants

A total of 240 participants completed the online questionnaire (Mage = 26.4, SDage = 6.58; 75% female). General stress level, measured by the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) (S. Cohen et al., Citation1983), was slightly below the scale mean (M = 2.84, SD = 0.76, n = 240; 1 = low stress level, 5 = high stress level).

Pretest

A pretest was conducted (n = 40) to validate the manipulation in the stimuli. One participant was excluded because of numerous missing values. The results of unpaired t-tests revealed significant differences concerning the address style. Participants who saw the direct address version of the poster felt more personally addressed by the posters (M = 4.00, SD = 1.17, n = 19) than the participants in the no-address condition (M = 2.42, SD = 1.08, n = 20; t(37) = −4.390, p < 0.001). The manipulation of the narrative voice was successful. In both groups, 95% of the participants correctly recalled the narrative voice used in the stimuli (n1 = 19, n3 = 18).

Results study 1

Main analysis

To evaluate the proposed hypotheses, a Cox regressionFootnote1 was performed. A Cox regression allows each characteristic’s utility to be estimated through the decomposition of the overall judgment (e.g., the poster that participants chose as exerting pressure) into each characteristic’s partial contribution to this decision. The part-worth utility describes the importance of one characteristic (e.g., first-person narrative voice) in all the decisions made in the choice tasks. The total utilities summarize the part-worth utility of all the characteristics applied in one stimulus, for example, the stimulus using first-person narrative voice and direct address is calculated by adding the part-worth utility of the direct address and the first-person narrative voice. To compare the utilities, the attribute with the lowest utility within each characteristicFootnote2 (narrative voice: third-person; address style: no address) was set to zero. As a result, the higher the utility, the more often the characteristic or stimulus was chosen as making the recipient feel pressured.

The results (see ) showed a significant influence of narrative voice on the feeling of being pressured (uvoice = 0.873, SE = 0.071, p < 0.001), with the first-person narrative voice making people feel more pressured than the third-person narrative voice (H1 rejected). No significant effects on feeling pressured were found for address style (uaddress = 0.036, SE = 0.067, p = 0.590) thus, H2 rejected.

Table 1. Cox-regression of narrative characteristics.

The third hypothesis assumed that messages combining direct address and first-person lead to lower feelings of pressure than all other combinations. The stimulus with the lowest utility value was the one chosen less often as making recipients feel pressured. The results demonstrated that the best combination was the stimulus with a third-person narrative voice and without address (u4 = 0)Footnote3, followed by the poster combining third-person with direct address (u3 = .036). The stimuli producing the greatest feelings of pressure combined the first-person narrative voice with direct address (u1 = 0.909; H3 rejected).

To investigate the importance of each characteristic, the relative importance of the characteristics narrative voice and address style was calculated by normalizing the sum of the part-worth utilities to zero.Footnote4 The results showed that narrative voice (ivoice = 0.96) had a stronger influence on feeling pressured than address style (iaddress = 0.04). This implies that, in most cases, the narrative voice was the deciding factor in regard to feeling pressured (RQ1).

Discussion study 1

The results indicated that a PSA poster using a first-person narrative voice as well as directly addressing the audience increased recipients’ feelings of being pressured. One explanation is that the participants perceived the first-person perspective and the direct address as too intrusive. Tukachinsky and Sangalang (Citation2016) found that audience members engrossed in a PSI with the protagonist were more likely to feel that their freedom was being threatened. The authors assume that the audience felt attacked by the speaker. A protagonist who directly addresses the audience members is perceived as demanding (Kress & van Leeuwen, Citation2021) which can be perceived as imperious. The first-person narrative voice PSA might increase pressure because audience members lose distance in relation to the protagonist, find themselves in the situation displayed, and become concerned.

Another question raised by our results is whether the feeling of “being put under more pressure” might not have indicated an antecedent of reactance but rather addressed an achievement motivation (e.g., the pressure to act). The persuasive attempt might have been evaluated as the pressure in the sense that participants felt encouraged to change their attitudes (Fransen et al., Citation2015). This assumption is supported by previous findings which showed that reactance is associated not only with negative emotions but also with activation and feeling strong and determined (Steindl et al., Citation2015).

Due to the conjoint design, we could use only a single item as the dependent variable. We chose to ask our participants about their “feeling of being put under pressure.” It is not possible to determine whether the address style and the narrative voice influence PSI or identification or whether the feeling of being pressured indicates pressure to comply with or pressure to refuse the recommendations. To address these limitations, we conducted a second study aiming at exploring how address style and narrative voice influence message effectiveness and the underlying psychological mechanisms (i.e., parasocial interaction and identification), as well as examining their effects on the behavioral intention of “being pressured” by a PSA.

Research interest study 2

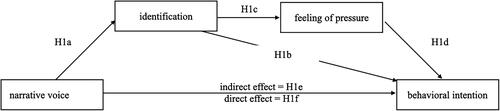

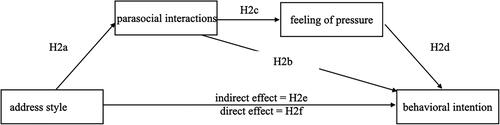

In keeping with the theoretical and empirical findings previously discussed as well as the results of study 1, we assume that a first-person narrative voice increases identification (H1a). Identification should be positively associated with behavioral intentions (H1b). As the feeling of being pressured might indicate pressure to comply and a motivation to achieve the proposed behavior, we propose a positive effect of identification on the feeling of being pressured (H1c), which is positively associated with behavioral intention (H1d). We assume that the positive effect of narrative voice on behavioral intention is partly mediated by identification (Vafeiadis and Shen, Citation2021) and the feeling of being pressured (H1e). Lastly, we assume that a positive direct effect of narrative voice on behavioral intention remains (H1f; see ).

The second set of hypotheses predicts that the direct verbal and physical addressing of the audience increases PSIs with the media character (H2a). We assume that PSI is positively associated with behavioral intentions (H2b). PSI should increase the feeling of being pressured (H2c), and this should foster behavioral intention (H2d). In line with previous research (Rosaen et al., Citation2019), we hypothesize that the positive effect of address style on behavioral intention is partly mediated by PSI and by the feeling of being pressured (H2e), and that a positive direct effect remains (H2f; see ).

Method study 2

Research design and procedure

To investigate the hypotheses, we conducted an online experiment with a 2 (narrative voice: first- vs. third-person) × 2 (address style: direct verbal and physical address vs. no address) between-subjects design, using the same stimulus material as in Study 1.

Participants were recruited via an online access panel (SoSci-Panel; www.soscipanel.de) with inclusion criteria between 18 and 65 years of age, and 50% female participation. Participants were asked about their general stress level and were randomly presented with one of the four-poster versions. They answered questions about the poster, the protagonist, and their perception of the message, followed by questions about stress management and sociodemographic variables.

Measures

Unless otherwise noted, all items were measured using a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (e.g., “not applicable at all” or “do not agree at all”) to 5 (e.g., “totally applicable” or “fully agree”).

Feeling of pressure

As in Study 1, the feeling of being pressured was measured after being presented with the stimulus. Participants were asked how pressured the poster made them feel (1 = “not at all” 5 = “extremely”; M = 2.31, SD = 1.04).

Behavioral intention

Participants’ intention to prevent stress was measured with the behavioral intention scale (Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation1975), adapted for the topic (e.g., “How likely are you to actively do something to combat stress?”; M = 3.30, SD = 1.03, α = 0.76). Higher values indicate stronger behavioral intentions.

PSI

PSI with the protagonist was measured using the experience of PSI scale developed by Hartmann and Goldhoorn (e.g., “While viewing the poster, I had the feeling that Ian was aware of me”; Hartmann & Goldhoorn, Citation2011; M = 1.53, SD = 0.81, α = 0.91).

Identification

Participants’ identification with the person displayed on the poster was measured using eight items adapted from identification studies (e.g., “While viewing the poster, I felt like I could really get inside Ian’s head”; M = 2.81, SD = 0.94, α = 0.90; Cohen, Citation2001; Tal-Or & Cohen, Citation2010).

Participants

A total of 295 participants completed the online questionnaire in March 2020 (M = 37.7, SD = 13.56; 63% female). As in sample 1, the general stress level according to the Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen et al., Citation1983) was slightly below the scale mean (M = 2.90, SD = 0.61, α = 0.70, n = 295; 1 = low stress level, 5 = high stress level).

Data analysis

First, zero-order correlations were calculated (). The patterns confirmed several but not all of our assumptions. Address style and PSIs are positively correlated (r = 0.15, p = 0.008). Narrative voice and identification do not correlate (r = 0.03, p = 0.644). The feeling of being pressured is positively correlated with PSIs (r = 0.16, p = 0.005), identification (r = 0.32, p < 0.001), and behavioral intention (r = 0.14, p = 0.019).

Table 2. Means, standard deviations, Pearson zero-order correlations, and internal consistencies.

To test the hypotheses, data were analyzed using the PROCESS macro for SPSS (Custom Model, V3.4; Hayes, Citation2017). To test indirect effects for significance, 95% confidence intervals were calculated with 10,000 bootstrapping samples. Address style and narrative voice were entered as independent variables in the respective models with PSI and identification as mediators. In both models, the feeling of being pressured was the second mediator and behavioral intention was the dependent variable. To control for the other manipulations in the factorial design, the other factor was included as covariate.

Results study 2

Main analysis

The first mediation analysis () showed that a first-person narrative voice did not lead to a higher degree of identification (H1a rejected). Stronger identification led to a stronger intention to prevent stress (H1b accepted) and a greater feeling of pressure (H1c accepted). The feeling of being pressured did not lead to a stronger intention to prevent stress (H1d rejected). The indirect effect of narrative voice, identification, and feeling pressured was not significant (H1e rejected). An indirect effect means that one variable (i.e., narrative voice) affects another variable (i.e., behavioral intention) through one or more other variables (i.e., identification and feeling pressured). In other words, identification and feeling pressured are the mechanisms by which narrative voice is expected to influence behavioral intention. Narrative voice showed a direct negative effect on the intention to prevent stress (H1f rejected).

Figure 4. Results of the research model for narrative voice and identification. Indirect effect: narrative voice—identification—behavioral intention: β = 0.012, B = 0.012, SE B = 0.022, 95% CI [−0.028, 0.059]. Indirect effect: narrative voice—identification—feeling of pressure—behavioral intention: β = 0.002, B = 0.002, SE B = 0.005, 95% CI [−0.025, 0.053]. n = 292.

![Figure 4. Results of the research model for narrative voice and identification. Indirect effect: narrative voice—identification—behavioral intention: β = 0.012, B = 0.012, SE B = 0.022, 95% CI [−0.028, 0.059]. Indirect effect: narrative voice—identification—feeling of pressure—behavioral intention: β = 0.002, B = 0.002, SE B = 0.005, 95% CI [−0.025, 0.053]. n = 292.](/cms/asset/e08c4dbb-857f-4554-a0d7-2dd87b5ae8a8/whmq_a_1995643_f0004_b.jpg)

In the second mediation analysis (), direct address led to stronger PSIs compared to no address (H2a accepted). PSIs had a positive impact on behavioral intentions to prevent stress (H2b accepted) and triggered a stronger feeling of being pressured (H2c accepted); this stronger feeling supported behavioral intentions to prevent stress (H2d accepted). The indirect effect of address style, PSIs, and feeling pressured on behavioral intention was small but significant and positive (H2e accepted). This means that PSIs and feeling pressured function as mechanisms for the influence of address style on behavioral intentions. The direct effect of address style on behavioral intention was negative (H2f rejected). As the indirect effect has a different sign than the direct effect, it was an inconsistent (Blalock, Citation1969; Davis, Citation1985) or competitive (Nitzl et al., Citation2016) mediation. The negative effect of direct verbal and physical address on behavioral intention contrasts with the positive indirect effect of PSIs or the feeling of being pressured combined with PSIs. As the indirect effect is small (β = 0.05), the total effect of direct address on behavioral intentions remains negative (β = −0.23).

Figure 5. Results of the research model for address style and parasocial interactions. Indirect effect: address style—parasocial interactions—behavioral intention: β = 0.04, B = 0.04, SE B = 0.02, 95% CI [0.005, 0.092]. Indirect effect: address style—parasocial interactions—feeling of pressure—behavioral intention: β = 0.01, B = 0.01, SE B = 0.01, 95% CI [0.000, 0.019]. n = 292.

![Figure 5. Results of the research model for address style and parasocial interactions. Indirect effect: address style—parasocial interactions—behavioral intention: β = 0.04, B = 0.04, SE B = 0.02, 95% CI [0.005, 0.092]. Indirect effect: address style—parasocial interactions—feeling of pressure—behavioral intention: β = 0.01, B = 0.01, SE B = 0.01, 95% CI [0.000, 0.019]. n = 292.](/cms/asset/26021924-a99e-45d8-b69e-0f0b15ae32a3/whmq_a_1995643_f0005_b.jpg)

General discussion

This research examined the influence of two message design characteristics—address style and narrative voice—on recipients’ feelings of being pressured by a PSA. The results of the first study showed that using a first-person narrative voice and direct physical and verbal address as design elements increased the feeling of being pressured by the PSA. A first explanation could be that the message characteristics employed did not successfully trigger PSIs or identification and, therefore, failed to develop their attenuating effect on defensive reactions. The “feeling of pressure” could be an indicator of peer pressure, which in turn reduces the rejection of media characters’ recommendations.

As conclusions on the effects of the message characteristics are limited due to the conjoint design, we conducted an online experiment to investigate the impact of narrative voice and address style on identification and PSI and on persuasive outcomes. The findings of Study 2 showed that direct address increased PSIs and led to a stronger feeling of being pressured. The first-person narrative voice did not increase identification, but higher levels of identification did lead to stronger feelings of being pressured.

A second explanation could be that feeling pressured through the direct address of a media character narrating in a first-person voice does not necessarily lead to or indicate reactance. Although the persuasive attempt was evaluated as exerting pressure, the pressure of a closely perceived protagonist motivated the participants to adapt the behavior according to the recommendations. Typically, reactance leads to an urge to regain one’s threatened autonomy and is a strong motivational force, generally seen in a desire to refuse and to act contrary to the recommendations (Brehm, Citation1966; Siegel et al., Citation2017). The current study demonstrates that feeling pressured can also promote positive effects in such a way that it fosters one’s motivation to tackle the health issue–but only when the feeling of pressure is triggered by PSI. Similar results have been shown in another study where the experience of reactance elicited heightened achievement motivation (Steindl et al., Citation2015).

In previous research, a direct positive effect of direct physical and verbal address on persuasive outcomes has been identified (e.g., Beege et al., Citation2017). Surprisingly, our results revealed a negative direct effect on behavioral intention. A possible explanation might be the protagonist’s representation; Although direct eye contact is expected to increase PSI, a person who gains and maintains direct eye contact with the viewer can be perceived as threatening, which would prevent the audience from interacting parasocially. When people interact parasocially, they might experience a stronger feeling of pressure that would motivate them to modify their behavior, explaining the positive effect of direct address. Therefore, we suggest considering these two effects as independent of each other: Either the direct address leads directly to a lower intention to prevent stress, or it enhances PSIs and the feeling of pressure, which in turn leads to a stronger intention to prevent stress.

Contrary to our assumptions, the first-person PSA did not trigger behavioral intentions. Other studies have reported mixed results on the relationship between narrative voice and persuasive outcomes. The third-person narrative voice was shown to lead to more favorable attitudes than the use of a first-person narrative voice; no effects of narrative voice on attitudes were found (Ma & Nan, Citation2018); and no differences between first- and third-person narrative voice on attitudes were identified (Nazione, Citation2016). Our results come closest to those found by Christy (Citation2018): third-person narrative voice leads to a more thorough motivation to prevent stress than first-person narrative voice.

The first-person narrative voice did not lead to stronger identification. These results were reported by other studies in health communication that either could not confirm results or found mixed results regarding the influence of narrative voice on identification (Chen et al., Citation2016; Christy, Citation2018; Ma & Nan, Citation2018). There are three possible explanations for our results. First, the address style could be manipulated by visual and verbal cues, while the narrative voice was manipulated only via written text. If the audience was not paying close attention, the effect of the narrative voice could be small. Second, the narrative voice may lose its impact if the person portrayed is engaging in unhealthy behavior. The involvement of the protagonist in unhealthy behavior—for example, working in a stressful environment—may have prevented the audience from identifying. In comparable studies, a connection between narrative voice and identification was found when the message encouraged the recipients to adapt their behavior following the message (Nan et al., Citation2015), but no connection was shown when the audience was asked to stop the behavior (Nazione, Citation2016). The third possible explanation is the feeling of belonging to another group. The recipients could defend themselves by perceiving the protagonist as being entirely different, despite any similarities. The decision about whether the audience accepts or rejects the similarity can influence the message processing and processes such as identification and persuasive outcomes (Christy, Citation2018; Kaufman & Libby, Citation2012).

Limitations and future research

First, in Study 1, in six choice tasks, the participants had to decide which of two presented poster versions made them feel pressured. The number of choice tasks leading to a valid measurement has been discussed in the literature and can vary from three to 30 choice tasks, depending on the stimulus material (Bansak et al., Citation2018; Chrzan & Orme, Citation2000). As there was a significant amount of information about the protagonist, stress in general, and especially stress prevention, the stimuli may have become rather complex. Subsequently, the six choice tasks could have caused respondent fatigue (Bansak et al., Citation2018), reducing the validity of the results.

Second, there was only one stimulus version, which depicted a young, white man as the protagonist. According to the similarity-identification hypothesis (Maccoby & Wilson, Citation1957), audience members tend to identify with protagonists they perceive as similar to themselves. A recent study found that young participants reading a health testimonial experience stronger identification with a young, same-sex protagonist than with an older protagonist of the opposite sex (Chen et al., Citation2016). In another study, the similarity-identification hypothesis was disproven as similarity with the protagonist did not lead to stronger identification (Cohen et al., Citation2018). To address this, multiple poster versions could be created to enable the participants to identify with a similar protagonist. Nevertheless, participants were randomly distributed among experimental conditions; the effects should be equivalent across both groups and no differences in identification were found between sexes.

Conclusions

This research contributes to the current literature in several ways: First, combining a first-person narrative voice and direct physical and verbal address in a message increases the feeling of being pressured. Second, feeling pressured by a PSA does not imply refusal of the recommendations. Our results suggest that direct address can increase the intention to prevent unhealthy behaviors while still triggering a feeling of being pressured by the persuasive message. If people do not interact parasocially with a media character, direct address lead to a decreased intention to perform the recommended behavior. Thus, design practitioners need to be mindful of the psychological mechanisms of identification and PSIs when using a protagonist as a spokesperson directly addressing the audience about health information. Triggering a feeling of being pressured through a spokesperson can be positive in the sense that the audience becomes motivated to engage in the displayed behavior—but only if PSIs are enabled.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (2.4 MB)Disclosure statement

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in OSF: https://osf.io/8ek3p/

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 A layered Cox regression employs a logit-choice model with a log-likelihood function, thereby applying the same assumptions as in the choice-based conjoint design (Cox & Oakes, Citation1984).

2 When setting the less-chosen characteristic to zero, the comparison is facilitated.

3 Poster 1 (first-person, no address), Poster 2 (third-person, no address), Poster 3 (third-person, direct address), Poster 4 (first-person, direct address).

4 As in the Cox regression results previously interpreted, only differences in utility matter. Thus, normalizing the sums to zero allows for a comparison of importance.

References

- Auter, P. (1992). TV that talks back: An experimental validation of a parasocial interaction scale. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 36(2), 173–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838159209364165

- Bansak, K., Hainmueller, J., Hopkins, D. J., & Yamamoto, T. (2018). The number of choice tasks and survey satisficing in conjoint experiments. Political Analysis, 26(1), 112–119. https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2017.40

- Beege, M., Schneider, S., Nebel, S., & Rey, G. D. (2017). Look into my eyes! Exploring the effect of addressing in educational videos. Learning and Instruction, 49, 113–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2017.01.004

- Blalock, H. M. (1969). Theory construction: From verbal to mathematical formulations. Prentice-Hall.

- Brehm, J. W. (1966). A theory of psychological reactance. Academic Press.

- Brehm, S. S., & Brehm, J. W. (1981). Psychological reactance: A theory of freedom and control. Academic Press.

- Brusch, M., Baier, D., & Treppa, A. (2002). Conjoint analysis and stimulus presentation. A comparison of alternative methods. In Classification, Clustering, and Data Analysis. Recent Advances and Applications. (pp. 203–210). Springer.

- Burgoon, M., Alvaro, E., Grandpre, J., & Voulodakis, M. (2002). Revisiting the theory of psychological reactance. Communicating threats to attitudinal freedom. In J. P. Dillard & M. Pfau (Eds.), The persuasion handbook. Developments in theory and practice (pp. 196–212). Sage Publications.

- Chen, M., & Bell, R. A. (2021). A meta-analysis of the impact of point of view on narrative processing and persuasion in health messaging. Psychology & Health, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2021.1894331

- Chen, M., Bell, R. A., & Taylor, L. D. (2016). Narrator point of view and persuasion in health narratives: The role of protagonist-reader similarity, identification, and self-referencing. Journal of Health Communication, 21(8), 908–918. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2016.1177147

- Chen, M., McGlone, M. S., & Bell, R. A. (2015). Persuasive effects of linguistic agency assignments and point of view in narrative health messages about colon cancer. Journal of Health Communication, 20(8), 977–988. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2015.1018625

- Christy, K. R. (2018). I, you, or he: Examining the impact of point of view on narrative persuasion. Media Psychology, 21(4), 700–718. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2017.1400443

- Chrzan, K., & Orme, B. (2000). An overview and comparison of design strategies for choice-based conjoint analysis. Sawtooth Software Research Paper Series, 98382, 161–178.

- Cohen, J. (2001). Defining identification: A theoretical look at the identification of audiences with media characters. Mass Communication and Society, 4(3), 245–264. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327825MCS0403_01

- Cohen, J., Oliver, M. B., & Bilandzic, H. (2019). The differential effects of direct address on parasocial experience and identification: Empirical evidence for conceptual difference. Communication Research Reports, 36(1), 78–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824096.2018.1530977

- Cohen, J., Weimann-Saks, D., & Mazor-Tregerman, M. (2018). Does character similarity increase identification and persuasion? Media Psychology, 21(3), 506–528. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2017.1302344

- Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385–396. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136404

- Cox, D. R., & Oakes, D. (1984). Analysis of survival data. Chapman and Hall.

- Davis, J. (1985). The logic of causal order. Sage Publications.

- Dillard, J. P., & Shen, L. (2005). On the nature of reactance and its role in persuasive health communication. Communication Monographs, 72(2), 144–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637750500111815

- Fishbein, M. A., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention and behavior. An introduction to theory and research. Addison-Wesley.

- Fransen, M. L., Smit, E. G., & Verlegh, P. W. J. (2015). Strategies and motives for resistance to persuasion: An integrative framework. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1201.

- Genette, G. (1990). Narrative discourse revisited. Cornell University Press.

- Hartmann, T., & Goldhoorn, C. (2011). Horton and Wohl revisited: Exploring viewers’ experience of parasocial interaction. Journal of Communication, 61(6), 1104–1121. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2011.01595.x

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

- Hoeken, H., & Fikkers, K. M. (2014). Issue-relevant thinking and identification as mechanisms of narrative persuasion. Poetics, 44, 84–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2014.05.001

- Igartua, J.-J., & Rodríguez-Contreras, L. (2020). Narrative voice matters! Improving smoking prevention with testimonial messages through identification and cognitive processes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(19), 7281. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197281

- Kaufman, G. F., & Libby, L. K. (2012). Changing beliefs and behavior through experience-taking. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 103(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027525

- Klimmt, C., Hartmann, T., & Schramm, H. (2006). Parasocial interactions and relationships. In J. Bryant & P. Vorderer (Eds.), Psychology of entertainment (pp. 291–313). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Kress, G., & van Leeuwen, T. (2021). Reading images: The grammar of visual design (3rd ed.). Routledge.

- Ma, Z., & Nan, X. (2018). Role of narratives in promoting mental illnesses acceptance. Atlantic Journal of Communication, 26(3), 196–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/15456870.2018.1471925

- Maccoby, E. E., & Wilson, W. C. (1957). Identification and observational learning from films. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 55(1), 76–87. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0043015

- Moyer-Gusé, E. (2008). Toward a theory of entertainment persuasion: Explaining the persuasive effects of entertainment-education messages. Communication Theory, 18(3), 407–425. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2008.00328.x

- Nan, X., Dahlstrom, M. F., Richards, A., & Rangarajan, S. (2015). Influence of evidence type and narrative type on HPV risk perception and intention to obtain the HPV vaccine. Health Communication, 30(3), 301–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2014.888629

- Nazione, S. (2016). An investigation of first- versus third-person risk narrative processing through the lens of the heuristic-systematic model. Communication Research Reports, 33(2), 145–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824096.2016.1155048

- Nitzl, C., Roldan, J. L., & Cepeda, G. (2016). Mediation analysis in partial least squares path modeling: Helping researchers discuss more sophisticated models. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 116(9), 1849–1864. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-07-2015-0302

- O’Keefe, G. J., & Reid, K. (1990). The uses and effects of public service advertising. Public Relations Research Annual, 2(1–4), 67–91. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532754xjprr0201-4_3

- Orme, B. K. (2010). Getting started with conjoint analysis: Strategies for product design and pricing research. Research Publishers.

- Quick, B. L., Scott, A. M., & Ledbetter, A. M. (2011). A close examination of trait reactance and issue involvement as moderators of psychological reactance theory. Journal of Health Communication, 16(6), 660–679.

- Quick, B. L., & Stephenson, M. T. (2008). Examining the role of trait reactance and sensation seeking on perceived threat, state reactance, and reactance restoration. Human Communication Research, 34(3), 448–476. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2008.00328.x

- Reynolds-Tylus, T. (2019). Psychological reactance and persuasive health communication: A review of the literature. Frontiers in Communication, 4, 56. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2019.00056

- Rosaen, S. F., Dibble, J. L., & Hartmann, T. (2019). Does the experience of parasocial interaction enhance persuasiveness of video public service messages? Communication Research Reports, 36(3), 201–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824096.2019.1598854

- Shen, L., Seung, S., Andersen, K. K., & McNeal, D. (2018). The psychological mechanisms of persuasive impact from narrative communication. Studies in Communication Sciences, 17(2), 165–181. https://doi.org/10.24434/j.scoms.2017.02.003

- Siegel, J. T., Lienemann, B. A., & Rosenberg, B. D. (2017). Resistance, reactance, and misinterpretation: Highlighting the challenge of persuading people with depression to seek help. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 11(6), e12322. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12322

- Steindl, C., Jonas, E., Sittenthaler, S., Traut-Mattausch, E., & Greenberg, J. (2015). Understanding psychological reactance: New developments and findings. Zeitschrift Fur Psychologie, 223(4), 205–214. https://doi.org/10.1027/2151-2604/a000222

- Tal-Or, N., & Cohen, J. (2010). Understanding audience involvement: Conceptualizing and manipulating identification and transportation. Poetics, 38(4), 402–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2010.05.004

- Tukachinsky, R., & Sangalang, A. (2016). The effect of relational and interactive aspects of parasocial experiences on attitudes and message resistance. Communication Reports, 29(3), 175–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/08934215.2016.1148750

- Vafeiadis, M., & Shen, F. (2021). Effects of narratives, frames, and involvement on health message effectiveness. Health Marketing Quarterly, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/07359683.2021.1965824

- Wei, L., Ferchaud, A., & Liu, B. (2019). Endorser and bodily addressing in public service announcements: Effects and underlying mechanisms. Communication Research Reports, 36(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824096.2018.1524752

- Wicklund, R. A. (1974). Freedom and reactance (p. 205). Lawrence Erlbaum.