1. Introduction

I could feel my mind buzzing after another long day at work. Driving home, I am looking forward to my “me time” ritual of playing with colors. As I arrive, I get myself comfortable, pick up an orange crayon, and start coloring a mandala with beautiful lace-like details. For that, I have to fully concentrate, and my attention is focused on the unfolding present experience of slowly and mindfully filling in the mandala with color. Once I filled in all the little spaces from the central layer, I pick up a green crayon and color the next layer. When I make mistakes is usually because I am not paying attention. I now tend to accept and work my way around them. Before I know it, my mandala is complete, and my buzzing mind has calmed down. I can even pinpoint some subtle feelings unreachable when I started, wondering also how I could do better next time. By looking at the colored mandala, I can see from my mistakes when I was less mindful and lost focus. I also know that there were other moments of lost focus, albeit I cannot see them in my mandala. Maybe because these happened while coloring larger areas, and then mistakes are easier to avoid even without concentration.

This scenario inspired by our study findings illustrates the richness of mandala coloring as an illustration of a focused attention mindfulness (FAM) practice. It shows the importance of intention, attention, and non-judgmental acceptance, with an invitation to explore how the materialization of mindfulness states onto colors may provide value to this practice.

While acknowledging the complexity of mindfulness constructs (Hart et al., Citation2013), for the purpose of our work we adopt the working definition of mindfulness as “the awareness that emerges through paying attention on purpose, in the present moment, and non-judgmentally to the unfolding of experience moment by moment” [pp. 145] (Kabat-Zinn, Citation2009). Nevertheless, consistent findings in the literature indicate that the skills required to sustain and regulate attention are challenging to develop (Kerr et al., Citation2013; Sas & Chopra, Citation2015). Mindfulness practices have been broadly categorized under focused attention – involving sustained attention on an intended object, and open monitoring – with broader attentional focus, hence no explicit object of attention (Lutz et al., Citation2008). While FAM targets the focus and maintenance of attention by narrowing it to a selected stimulus despite competing others and, when attention is lost, disengaging from these distracting stimuli to redirect it back to the selected one, rather than narrowing it, open monitoring involves broadening the focus of attention through a receptive and non-judgmental stance toward moment-to-moment internal salient stimuli such as difficult thoughts and emotions (Britton, Citation2018).

FAM is typically the starting point for novice meditators, with the main object of attention being either internal (e.g., focus on the breathing in sitting meditation (Prpa et al., Citation2018; Vidyarthi et al., Citation2012), or on bodily movements during walking meditation (S. S. Chen et al., Citation2015) or Tai-Chi (Cheng et al., Citation2016)), or external (e.g., focus on the light of candle in sitting meditation (Häkkilä et al., Citation2016) or the Tibetan praying wheel (Wu et al., Citation2015)). Most work in this space has been drawn from static FAM practices such as sitting meditation (Lutz et al., Citation2008; Vago & Silbersweig, Citation2012). This is surprising given the acknowledged value of bodily movement in traditional mindfulness practices such as walking meditation, tai-chi or mandala coloring (Schmalzl et al., Citation2014), and their growing interest among the general population (Campenni & Hartman, Citation2020; The Statistics Portal, Citationn.d.).

As the HCI work on mindfulness technologies has started to mature, new areas of this design space have started to be explored involving more complex interactions needed to account for both attention regulation and movement. Such technologies involve not just audio-visual input but alternative modalities such as haptic, thermal, or vibration neuro-feedback (Roquet & Sas, Citation2021). We argue that the foundation of technologies for sitting meditation is now ripe to explore these less investigated mediation practices involving fine motor skills. For instance, mandala coloring has been identified as an effective form of mindful self-tracking of mood (Ayobi et al., Citation2018) or as part of the empathic co-creative design of Spheres of Wellbeing for mindfulness practice (Thieme et al., Citation2013). This opens up new design opportunities for mindfulness technologies that can not only support these specific practices, but provide fresh insights into mindfulness training more broadly. In this paper, we focus on mandala coloring as an illustration of a non-static FAM practice, with an external object of attention. Therefore, this less explored design space offers untapped design opportunities for novel mindfulness technologies.

The benefits and challenges of mindfulness training (Brown & Ryan, Citation2003; Calvo & Peters, Citation2014; Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present and future, Citation2003) have inspired a growing number of focused attention mindfulness (FAM) technologies in HCI. These systems commonly use bodily responses such as respiration or brain activity to capture mindfulness states, and map them onto real-time interactive interfaces (Calvo & Peters, Citation2014; Kitson et al., Citation2018; Terzimehić et al., Citation2019). Interestingly, the trend in such work has been on providing the real-time monitoring of the practice on the same interface as the FAM’s main object of attention. However, the processes of regulating focused attention (e.g., concentrating on the light of a candle (Häkkilä et al., Citation2016) or on the creation of the mandala (Campenni & Hartman, Citation2020)), and of open monitoring have been shown to have distinct neural correlates (Malinowski, Citation2013). Therefore, we found there may be value in decoupling the interface to provide separate support to each of these core processes. To the best of our knowledge, such an approach has been little explored in FAM technologies so far. For instance, utilizing the main interface for the focal task of focused attention, and a peripheral interface for the secondary task of monitoring the practice.

Furthermore, focused attention and open monitoring in mindfulness practices have been often used as independent variables in previous work exploring their impact on mindfulness states and other measures of wellbeing (Britton et al., Citation2018). Therefore, there has been less work focused on them as dependent variables or, in other words, on measuring the different attention states associated with these two approaches. While research in the psychology of attention has led to several performance tasks for measuring both focused and distributed attention (Oken et al., Citation2006), these measures have been limitedly borrowed in the context of mindfulness training. This may be because such tasks measuring moment-to-moment attention drawn from the same attentional resources that are needed throughout mindfulness training. Thus, the design of the Anima prototype aims to support mindfulness training rather than the measurement of specific attention states involved in focused attention or open monitoring processes.

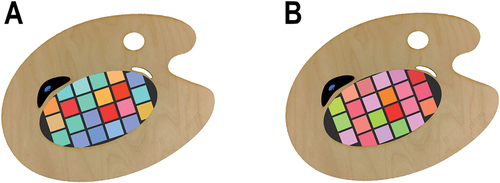

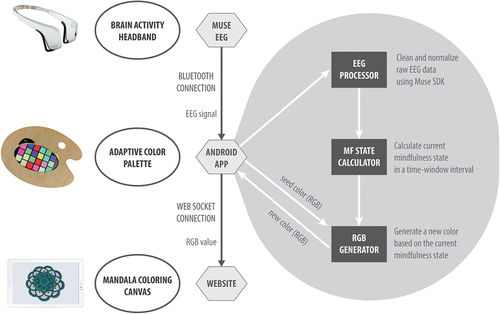

An additional challenge when designing mindfulness-based technologies is effectively communicating one’s mental states during the FAM practice, as questions such as ‘How can I know when I achieve a mindfulness state?’ or ‘How do I realize that my mind has wandered?’ Are common among novice meditators (Vago & Silbersweig, Citation2012). An extensive body of work in neuroscience has shown that brain activity data (EEG) can unobtrusively and accurately monitor mental states during mindfulness practice (Esch, Citation2014; Krigolson et al., Citation2017), hence the prevalence of EEG headsets in technological systems for mindfulness training both commercial ones (Krigolson et al., Citation2017; MuseTM – Meditation Made Easy with the Muse Headband, Citationn.d.) and HCI research prototypes (Amores et al., Citation2016; Cochrane et al., Citation2018). However, making sense of the mindfulness states captured by the EEG data is not trivial, and neither is capturing them through design (Alfaras et al., Citation2020; Sanches, Höök et al., Citation2019). To explore these challenges, we investigated the practice of mandala coloring and how it can inform the design of novel interactive technologies for FAM training. First, we report on an interview study with 21 people who had been coloring mandalas regularly for at least 1 year prior to the study. Findings provided us with a deeper understanding of mandala coloring, highlighting the motivations, context, and main qualities of this practice. Second, we detail the design and development of Anima: a brain–computer interface (BCI) working exemplar prototype, which integrates a tablet for coloring, a wearable EEG device, and a second tablet providing peripheral palette containing a color scheme based on one’s evolving mindfulness states during mandala coloring (). The aim of Anima goes beyond digitally replicating mandala coloring as it explores the value of subtle and peripheral neurofeedback for monitoring mindfulness training, whilst the mandala is being colored on the main interface, a quality that can inspire new classes of mindfulness technologies. Finally, the feasibility for supporting mindfulness states during mandala coloring using color-based metaphorical representations of mindfulness states on a peripheral interface was explored through participatory workshops with 12 participants, in which Anima was used as a working exemplar prototype (Sas et al., Citation2014).

Figure 1. Overview of the ANIMA system including: (left) a tablet-based mandala coloring canvas for the training of focused attention, (middle) a tablet-based adaptive color palette for peripheral monitoring of the mindfulness practice, and a brain activity headband for sensing the mindfulness states in real-time (right).

Key contributions of our work include: (i) an in-depth exploration of the focused attention mindfulness practice of mandala coloring with experts, (ii) novel design opportunities for harnessing peripheral interfaces to decouple the main task of focused attention from secondary task of monitoring attention during mindfulness training, and (iii) the concept of representational and temporal ambiguity in color-based metaphors to represent EEG data in order to facilitate its non-judgmental interpretation.

2. Background

Our paper draws from HCI work in three distinct areas: interactive systems for mindfulness training, interfaces for materializing bodily states and mandala coloring as a FAM practice.

2.1. Mindfulness-based interactive technologies

The increasing interest in mindfulness technologies is grounded in a wealth of findings showing the important benefits of mindfulness practices for both affective (Brown & Ryan, Citation2003; Carmody & Baer, Citation2008; Teasdale et al., Citation2000) and physical health (Kabat-Zinn, Citation1982; Zeidan et al., Citation2010). This is reflected in the growing range of technologies supporting mindfulness training from commercial smartphone apps (Daudén Roquet & Sas, Citation2018) to interactive systems (Sliwinski et al., Citation2017; Terzimehić et al., Citation2019); most of which are tailored to support focused attention practices, and often through guided meditation.

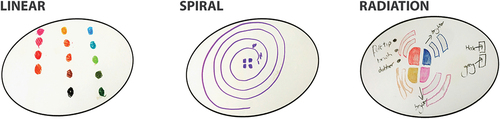

HCI research on FAM training () has looked at both external objects of attention such as tangible artifacts (Schmalzl et al., Citation2014; Vago & Silbersweig, Citation2012), and internal ones associated with bodily responses such as heart rate (Thieme et al., Citation2013; Zhu et al., Citation2017), electrodermal activity (Shaw et al., Citation2007), or breathing patterns (Vago & Silbersweig, Citation2012). These have been mapped into generative soundscapes (Prpa et al., Citation2018; Roo et al., Citation2017; Vidyarthi et al., Citation2012) and elements in virtual environments (Prpa et al., Citation2018; Roo et al., Citation2017), to provide real-time feedback and support for the mindfulness practice. Regarding the level of movement involved in the FAM practice, as shown in , the space of practices involving skilled movement such as mandala coloring has been underexplored with only two examples drawn from Zen Gardens (Roo et al., Citation2017) and mediation balls (Thieme et al., Citation2013).

Figure 2. Classification of mindfulness practices based on their range of movement, as well as their level of structure, illustrated with references to relevant HCI work.

Neurofeedback has also been explored for mindfulness training, although to a lesser extent. Such work leverages findings on neuro-correlates of mindfulness training (Bing-Canar et al., Citation2016; Lagopoulos et al., Citation2009; Vernon, Citation2005), as well as advances in wearable BCI technologies (Hinterberger & Thilo, Citation2011; Nacke et al., Citation2011; O’Hara et al., Citation2011) through which brain activity is used to represent changes in mindfulness states (Richer et al., Citation2018). For example, systems such as Relaworld (Kosunen et al., Citation2016) and PsychicVR (Amores et al., Citation2016) use EEG data related to focused attention mindfulness training to control elements in virtual environments; while MeditAid (Sas & Chopra, Citation2015) supports attention regulation in open monitoring through real-time, binaural beats-based feedback on mindfulness states.

Emerging HCI work has also looked at tangible interfaces to enhance the embodiment aspects of mindfulness practices (Kerr et al., Citation2013) although there has been limited exploration involving bio- or neurofeedback technologies. Examples in this space include PAUSE, a smartphone app for training mindfulness focused attention through the finger’s slow circular movement on the touchscreen (Cheng et al., Citation2016; Salehzadeh Niksirat et al., Citation2017); or the Channel of Mindfulness (Wang, Citation2011) which, inspired by the Tibetan praying wheel, consists of a tangible add-on to the smartphone that needs to be kept spinning in a steady rhythm. Both these systems provide adaptive audio-based feedback for monitoring the practice based on the maintenance, or not, of a gentle and continuous movement on the smartphone’s interface. Other examples of tangible technologies for mindfulness training are the Mindfulness Spheres (Thieme et al., Citation2013), Inner Garden (Roo et al., Citation2017) or Mind Pool (Long & Vines, Citation2013), which map physiological or brain signals onto creative audio-visual outputs. Inner Garden (Roo et al., Citation2017), for example, provides two distinct interfaces with different feedback modalities to support the mindfulness training: a tangible augmented sandbox and an immersive virtual environment. However, the use of peripheral interfaces to simultaneously support distinct aspects of mindfulness has not been yet explored.

To conclude, we have placed the body of work presented in this paper within a design space based on the FAM practice’s level of movement (), from meditation practices involving stillness such as focusing on a candle’s flame in sitting meditation, to those involving full body movement such tai chi or walking meditation. Unlike the ends of this continuum, the mid-range involving fine motor skills such as those in meditation practices of mala beads, mandalas, or Baoding balls have been less explored in HCI. The rationale for the limited work in this space could be that HCI interest in mindfulness technologies has started with the prototypical meditation practice of sitting meditation and the more traditional audio-visual- input often employed in early guided meditation systems used for such static practices.

2.2. Interfaces for materializing bodily states

There has been growing interest in HCI in exploring the materialization of bodily states for wellbeing and affective health technologies (Sanches, Janson et al., Citation2019; Sas & Coman, Citation2016; Sas, Hartley et al., Citation2020), mostly beyond the focus on mindfulness. For example, breathing patterns (Höök et al., Citation2016; Patibanda et al., Citation2017), brain activity (Hinterberger & Thilo, Citation2011; Wikström et al., Citation2017), electrodermal activity (Sanches, Höök et al., Citation2019) and heart rate variability (Umair et al., Citation2019) have been explored to support the awareness of and reflection on one’s emotional arousal and proprioception.

To address the challenge of materializing tacit internal states, researchers have investigated different metaphors for mapping them onto ambiguous representations (Höök et al., Citation2016) to support an open and playful exploration (Daudén Roquet & Sas, Citation2020) of meditation states (Roquet & Sas, Citation2021). Most work in this area has focused on visual feedback employing colors to represent emotional states (Umair et al., Citation2018), such as highly saturated red for high arousal ones (Hinterberger & Thilo, Citation2011; McDuff et al., Citation2012; Ståhl et al., Citation2009). Others have used virtual objects to convey naturally inspired metaphors, such as trees (Patibanda et al., Citation2017), whose shape and size vary mirroring changes in the user’s current arousal level (McDuff et al., Citation2012) or brain activity (Wikström et al., Citation2017). Regarding the level of ambiguity in the mapping, Höök and colleagues (Höök et al., Citation2008) proposed the concept of evocative balance between recognizable, yet open for interpretation metaphorical representations of “familiar lived experiences,” which has been also applied in haptic interactions that rely on heat and vibration (Höök et al., Citation2016; Umair et al., Citation2021, Citation2019).

To summarize, most HCI research exploring the materialization of bodily states has looked at mapping physiological signals onto ambiguous representations supporting emotional awareness and wellbeing, albeit there is limited integration of such work with mindfulness training technologies (Mohamed et al., Citation2017; Terzimehić et al., Citation2019; Zhu et al., Citation2017). In this paper, we aim to integrate the concept of evocative balance into a mindfulness technology. This type of ambiguity has been suggested to be key when designing novel classes of technologies or interactions, which potential users may have a limited prior knowledge of, as the ones involving EEG-based biodata (Alfaras et al., Citation2020; Gaver et al., Citation2003).

2.3. Mandala coloring: focused attention and self-expression

In this paper, we focus on the FAM practice of mandala coloring, which has received a growing interest among general population as it supports mindfulness training through self-expression, provides benefits for mental wellbeing (Blackburn & Chamley, Citation2016; Campenni & Hartman, Citation2020), and has been less explored in HCI. With its origins in Buddhist traditions, mandalas have been used for centuries as meditation aids in spiritual practices. Their geometry represents symbolic aspects of harmony, wholeness, and the self (Tucci, Citation2001). Starting from their epicenter, mandalas grow in a concentric structure consisting of circular layers that represent different aspects of the Buddhist Universe. Mandalas were brought to the Western culture and therapeutic context by Carl Jung (Slegelis, Citation1987), whose work suggested that the structure of mandalas facilitates focused attention and meditative states, which are beneficial for mental wellbeing (Kellogg et al., Citation1977).

2.3.1. Focused attention mindfulness

Findings from more recent studies on mandala coloring have shown that through the use of colors and the movement of coloring within geometric structures, mandalas require focused attention to the present moment and disengagement from any other thoughts or emotions (Campenni & Hartman, Citation2020; Curry & Kasser, Citation2005).

Within a widely accepted taxonomy of mindfulness (Vago & Silbersweig, Citation2012), FAM practices are considered the most widely accessible among beginners as they facilitate stabilizing the mind and decreasing mental proliferation by concentrating on a specific mental or sensory object such as coloring in a mandala (Daudén Roquet & Sas, Citation2019; Greenberg & Harris, Citation2012; Lutz et al., Citation2008). Therefore, the practitioner has to shift their attention from distractors – that can be internal thoughts and/or external stressors – to sustain it on the main object of attention.

Furthermore, traditional FAM practices tend to rely on tangible artifacts and movement to scaffold the focus of attention, for instance, using a candle for sitting meditation in which the practitioner needs to focus on the continuous movement of the flame (Perlman et al., Citation2010). Interestingly, most external objects of attention are fine skilled movement mediated by the tangible artifact (Schmalzl et al., Citation2014). For example, the Baoding Balls are two little spheres that need to be rolled in the palm of the hand, constantly switching the relative position of both balls whilst trying to avoid them touching each other. Similarly, the Tibetan Prayer Wheel also relies on small continuous movement of the hand as the cylindrical wheel spins clockwise whilst visualizing a mantra. Mandala coloring is another interesting example in this space, in which the object of attention is the fine, slow, and controlled movement of the hand to create and color in the intricate geometry.

According to neuro-psychology literature, internal objects of attention integrate conscious awareness with ongoing, dynamic viscero-somatic function (Vago & Silbersweig, Citation2012). Hence, fostering interoceptive awareness, an ability to receive and attend to the signals originating in our bodies, which is shown to improve attention task performance as well as emotion regulation (Farb et al., Citation2015; Farb et al., Citation2014). Whereas external objects of attention involve an underlying framework of motor learning that functions to strengthen non-conscious, associative memory processes (Vago & Silbersweig, Citation2012). The instructions for practice (e.g., coloring in the geometrical pattern of the mandala) form an executive set that is created and sustained by working memory processes, while attention processes operate to focus and sustain concentration on the external object (i.e. fine, controlled, and continuous movement). This “mind-body” connection has been suggested to have benefits to improve cognitive function and attention by coordinating executive goals, sustained attention and motor plans (Clark et al., Citation2015).

While the effects of static FAM practices such as sitting meditation have been extensively studied in psychology and neuroscience with proven benefits for physical and mental wellbeing, secular mindfulness practices such as mandala coloring have only started to receive scientific attention (Campenni & Hartman, Citation2020; Chen et al., Citation2019; Khademi et al., Citation2021; Rose & Lomas, Citation2020). HCI work in FAM practices follows a similar trend, with a well-established body of work exploring the design of meditation technologies (Terzimehić et al., Citation2019); whereas non-static FAM practices such as mandala coloring have just recently started to receive attention in HCI (Cochrane et al., Citation2021; Liang et al., Citation2020; Mah et al., Citation2020; Niksirat et al., Citation2019).

2.3.2. Self-expression through coloring

Besides its mindfulness benefits, mandala coloring also offers powerful forms of self-expression, being thus also a common tool in art therapy. Indeed, the literature on mandalas suggests that colored mandalas embody subtleties and layers of expression that may be difficult to articulate through words (Campenni & Hartman, Citation2020; Malchiodi, Citation2011). As a result, mandalas have been extensively used in art therapy for processing emotional experiences (Rappaport, Citation2013), expressed either consciously or unconsciously through the art materials (Moon, Citation2010), the way they are applied (Lusebrink, Citation2010), and the use of colors (Rappaport, Citation2013).

Given the context of mandala coloring, we found inspiration in another body of HCI work, which has built on art therapy to explore artistic representations for self-expression through crafts and art (Lusebrink, Citation2010). Craft activities have been used to scaffold self-expression to support memories (Sas et al., Citation2015) encode positive ones for people living with depression (Qu et al., Citation2018), or for supporting reminiscing in old age (Sas, Davies et al., Citation2020). The art therapy and its affordances for self-expression and bringing attention to the present experience have been particularly explored with people experiencing communication difficulties (Lazar et al., Citation2018) or living with dementia (Killick & Craig, Citation2011; Lazar et al., Citation2018), indicating benefits for their wellbeing.

Despite its link to traditional practices such as mandala coloring, the exploration of self-expression through craft and arts in the context of mindfulness practices has been limited. Emerging work in both HCI and psychology (Chen et al. (Citation2018); Kitson et al., Citation2018) have highlighted the importance of supporting digital mindfulness practices through embodied and ambiguous esthetic experiences (Daudén Roquet & Sas, Citation2018; Zhu et al., Citation2017). However, there is limited integration of embodied esthetic experiences supporting self-expression in mindfulness training technologies as a means of monitoring and interpreting one’s experience.

3. Study 1: Understanding the practice of mandala coloring

In this study, we explore the practice of coloring in mandalas as an illustration of movement-based mindfulness training. Mandala coloring has been explored mostly in Psychology as a task with non-experts to evaluate its impact on wellbeing (Babouchkina & Robbins, Citation2015; Curry & Kasser, Citation2005; Kersten & Van Der Vennet, Citation2010). Our work provides a fresh, complementary perspective by qualitatively exploring mandala coloring as an intrinsically motivated practice with long-term practicants. We report on interviews with 21 people who had been regularly coloring mandalas for at least a year prior to the study, with the aim of drawing novel design inspiration for mindfulness-based and mental wellbeing technologies. In particular, we focused on the following research questions:

What are the motivations, benefits, and challenges of engaging in mandala coloring practice?

In what spatio-temporal context is mandala coloring practiced?

What materials and actions are key in mandala coloring?

What physical and digital affordances support or hinder mandala coloring practice?

3.1. Method

The aim of our interview study was to explore the practice of mandala coloring and how this may inform the design of movement-based mindfulness technologies. We report on an interview study with 21 participants, partly completed online and partly face-to-face. In this paper we refer to them as practicants, since according to the inclusion criteria, they have been coloring mandalas regularly i.e. at least monthly, for a year prior to the study commencement.

3.1.1. Participants

We employed purposeful sampling (Palinkas et al., Citation2015) and recruited participants both by advertising the study in social media dedicated to mandala coloring (i.e. Instagram and Facebook pages and groups), and locally via the University’s mailing lists as well as with posters in campus and the city. Everyone who responded and met the inclusion criteria was included in the study. In total, 21 people participated in the study, with 11 interviews completed online and 10 face-to-face. The latter were compensated with a $10 worth Amazon voucher as they had to commute to University to participate in the study, which also took longer due to the in-lab session of mandala coloring.

From the total of 21 participants, 4 had over one-year experience of practicing mandala coloring, 14 between 1 and 5 years, and 3 over 5 years (Mean = 3.3 years, SD = 2.9), and none reported discontinuing the practice at any time. Furthermore, all participants described how they use mandala coloring as their regular self-care ritual: 15 reported coloring mandalas several times per week, and 6 several times a month. In terms of demographics, all participants identified as women. We would like to emphasize that despite the broad and diverse advertisement for this study, only women responded. This is consistent with related work (Flett et al., Citation2017), suggesting that mandala coloring could be a gendered practice. Regarding their age, 12 participants were between 16 and 25 years old, 3 between the ages of 26 and 35, 3 between 46 and 55, and 3 were over 55 years old (Mean = 31.5, SD = 14.7). And regarding occupations, 13 were students, 5 clerk workers, and 3 support workers. Interestingly, three participants (P16, P18, P19) did not only practice mandala coloring for themselves, but they also regularly used mandalas as healthcare professionals, as a tool for training mindfulness and enhancing the mental wellbeing of their clients.

3.1.2. Study procedure

We now describe the study design, which consisted on three distinct parts to better delve into their personal experience and understanding of mandala coloring: (1) investigating the process of selecting a mandala geometric pattern to color in, (2) coloring a mandala, and (3) exploring the participant’s view on mandala coloring. Parts 1 and 2 of the study were intended to bring the practice forward to be explored further during the semi-structured interviews in Part 3. As not all participants could attend face-to-face, the part two of the study was modified to fit both online and face-to-face participants, as detailed below.

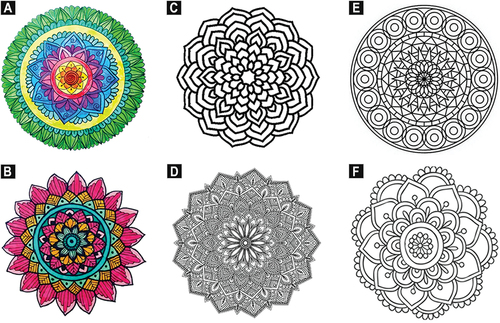

Part 1: Selecting a mandala geometry to color in. The main goal of this task was to bring the participants into the space of mandala coloring by firstly exploring their process of choosing a mandala to color in. Therefore, we provided them with a choice of four mandalas (, mandalas C-F) with distinct geometric characteristics (e.g., sharp versus rounded edges, thinner versus thicker outlines, distinct size, and number of details). Whilst they were choosing which mandala they would prefer to color in, we encouraged them to verbalize their thought process. Therefore, we asked them questions about the differences between the mandalas such as: What do you like the most about each mandala and why? What do you like the least about each mandala and why? Which mandala would you like to color in?.

Part 2: Coloring in a mandala. For the face-to-face participants, we asked them to color their preferred mandala from Part 1 either with the art materials provided (i.e. color pencils and felt tips). The coloring session lasted between 20 and 30 minutes (Curry & Kasser, Citation2005), 25 minutes on average, and the process was photographed ( shows a mandala being colored by P14). For the online participants, as we could not provide them with a physical copy of their chosen mandala from Part 1, we asked them to color one of their mandalas and send us a photo of it once finished (, mandalas A and B). In this way, we ensured that participants had a recent lived experience of mandala coloring prior to the interview study, despite it being in a lab setting rather than their regular space and context of practice. Furthermore, it allowed us to observe their coloring process and refine the questions of the semi-structured interviews based on their personal practice.

Figure 3. One participant’s illustration of mandala coloring process: starting from the center with the desired color, here felt tip (left), coloring in each concentric layer (middle), and partially completed mandala at the end of the session (right).

Part 3: Personal experience of mandala coloring. Finally, we employed semi-structured interviews, which included questions about the practicants’ understanding of mandalas, their benefits, and challenges: Which is your motivation for this practice? What benefits does it have for you? Do you perceive any challenges associated with it?, as well as their experience and context of practice: Where and when do you usually color mandalas? We also enquired about the process itself, from preparing for coloring to finishing a mandala: How do you choose which materials and colors to use? What happens if you make a mistake? What do you do when you finish and why? Finally, we explored the role of current technology in mandala coloring: Have you ever used an app for coloring in mandalas? If so, what did you like and dislike? If not, why not? How do you perceive the role of technology in this practice? All interviews lasted between 20 and 60 minutes (Mean = 30 minutes), were audio-recorded and fully transcribed.

3.1.3. Data analysis

Interviews were fully transcribed and analyzed following an iterative and hybrid approach to coding (Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, Citation2006), drawing upon a conceptual framework and its informed deductive codes. Codes from previous work included concepts such as materials and colors for self-expression, and the object of focused attention during the practice. The coding scheme was refined as new codes emerged from the interview data such as the significance of imperfections, qualities of movement, and context of practice. The authors revised the coding scheme weekly for several months to ensure consensus.

3.2. Findings

Our findings indicate three main themes including first-person perspectives into the motivations for engaging in mandala coloring practice, together with its main perceived benefits and challenges, the context of mandala practice, and coloring – as a progressive emotional expression. These are further described with examples from participants’ quotes, together with the presentation of the value of mandalas both analogly and digitally.

3.2.1. Motivations for engaging in mandala coloring: wellbeing and mindfulness

Findings indicate that people perceive mandala coloring as a self-care activity beneficial for their emotional well-being such as relaxing when stressed, and also for their mental health as a tool for depression or anxiety. These two reasons can be positioned on the ends of a continuum from wellbeing to mental health, with focused attention being key throughout.

Coloring Mandala for Emotional Wellbeing. All participants mentioned the value of mandala coloring for emotional wellbeing as it allows to express themselves freely, and facilitates sense-making of their thoughts and experiences, as illustrated in the following quote: “projecting something [you’re feeling] into something so visual it’s very helpful […] it’s almost as a projection of whatever it is that I’m feeling, so it kind of helps me understand and go through my thought process a little better” (P14). As a result, the practice of coloring mandalas is for most interviewees a deep and highly personal activity, which they become attached to: “the more you go through the process, the more you connect [with your emotions]” (P15). Another participant gave a more detailed account of this relationship, suggesting that mandalas offer a safe space to process feelings otherwise difficult to communicate, which in return requires nurturing: “I’m expressing and processing that emotion that’s stuck inside […] the mandala is giving something to you because it’s something beautiful that’s there for you to work with, but then you are giving something back as well because you are coloring it” (P18).

Coloring Mandala for Mental Health. A significant finding is that more than two-thirds of participants started coloring mandalas for mental health reasons. Unexpectedly, almost all explicitly mentioned starting this practice because of conditions such as stress (14 participants) or severe ones such as depression or anxiety (5 participants). In particular, two participants openly talked about their experience with depression. For example, P18 started with a therapist who encouraged to express herself through mandala coloring. Despite the initial resistance to disclose her negative emotions, mandala coloring became a recurrent activity providing a safe space for self-expression: “once you start the process, then it can become something you can go to, it’s like a support” (P18). In her case, the process of coloring mandalas helped self-regulate emotions through expressive strategies like using different colors and materials that would fit her affective state.

From Expressing to Regulating Emotional States. Apart from expressing emotions, mandala coloring offers also the benefit of regulating emotions, for both wellbeing and emotional health purposes. Another important outcome is that participants’ choice of materials and colors, and the ways in which they are used that relate to their emotional states. This indicates additional embodied ways of monitoring one’s focused attention: “if they are pressing really hard, they could be frustrated, or if they are doing it very delicately they might be calmer” (P18). As shown by the findings, the choice of colors is particularly important serving two both emotional expression and emotional regulation. The former is supported by participants’ choice of colors, so that they reflect their emotional states at the start of mandala coloring: “it depends on what I’m feeling; I think if I’m mellower I’d probably choose blues or greens, whereas if I’m angrier would be reds and pinks” (P14). This quote indicates the potential value of such colored mandala to provide emotional information of how they felt at the time. Mandala coloring also supports emotion regulation (Kellogg et al., Citation1977) when participants choose colors not to express how they feel in the moment but how they would like to feel: “if I had a bad day I would choose something really jolly and nice so that I could shed away all the stresses from the day” (P15). Such an outcome confirms findings on how mindfulness-based arts and expressive practices can support emotional regulation for decreasing symptoms of distress (Kellogg et al., Citation1977; Khademi et al., Citation2021).

Mandala Coloring as an Expressive, Movement-based Mindfulness Practice. We now describe participants’ accounts of mandala coloring that resonate with mindfulness training, as mentioned by 10 participants. In this respect, findings indicate aspects of mindfulness training such as the practice of focused attention on the present experience as relevant also during mandala coloring. Focused attention is a key aspect that each participant agreed on, in particular as coloring helps anchor their mind by focusing attention on the process of slowly coloring the intricate details of the mandala’s geometry: “you are being very careful – filling the little spots with color- and thinking ahead to the next color you’re going to put around, and that you need to let it dry” (P17). With respect to movement-based qualities of mandala coloring, all participants described it as an active mindfulness training: “instead of being like a guided meditation in which you have to listen, it is more active and you can see then what comes out” (P13). Thus, through their intrinsic and symmetrical pattern mandala provides sufficient scaffold to ground the practice: “because it has more structure, it’s less exposing” (P18). Participants also found that mandala coloring becomes a safe space to practice non-judgmental acceptance of one’s coloring and its associated emotional experience that can, in turn, be generalized to their everyday life. For example, for P17 mandalas were recommended in her Cognitive Behavioral Therapy treatment for depression (Kuyken et al., Citation2016), and she found they offered a safe space to practice reappraisal and acceptance when making coloring mistakes: “if you make a slight mistake you have to live with it, and you might have to rethink where you go after that” (P17). Such non-judgmental acceptance of mandala coloring process in its entirety suggests participants’ ability to take the observer’s perspective and to attend to the present experience without active evaluation, which is an important aspect of mindfulness training (Vago & Silbersweig, Citation2012). An important outcome related to the non-judgmental acceptance of mistakes is their role in indicating less mindful moments, as further described.

Mistakes as Tangible Feedback of Mindless Moments. Findings suggest that coloring mistakes play two main roles in this practice, as reported by 8 participants. The first, as detailed before, is the way in which they facilitate the development of non-judgmental acceptance. Secondly, through their immediate visibility, coloring mistakes provide participants with the opportunity to monitor their training of focused attention as mistakes act as tangible indicators of mindless moments: “Making sure how you stay in the lines, I wouldn’t do that if I were thinking about other things too much. But mind wonders sometimes, I’m not always that focused” (P12). Such mistakes () include crossing the boundary of a pattern, or breaking the symmetry of the mandala’s color pattern by filling a gap with the wrong color. Indeed, although generating frustration, coloring mistakes are particularly important to help people recognize mindless moments and to shift attention back to the coloring activity: “I always make mistakes when I am not focused. I suppose that in my younger days I’d been very upset if I made a mistake, but now it doesn’t bother me particularly. If this happens, I try to find a way to avoid it being noticed […] I try and work around it and make it right, change track a little bit.” (P4, mandala shown in ). As shown in this quote, practicants do not try to erase their mistakes, but instead make them fit within their current coloring pattern, further practicing acceptance and learning to let go as core concepts of mindfulness (Kabat-Zinn, Citation2009): “[during mandala coloring] relaxing and accepting mistakes is a key thing for me […] if you make a slight mistake you have to live with it, and you might have to sort of rethink where you go after that” (P6). This is also exemplified in P13’s mandala shown in , highlighted with a double circle as the mistake has not only been accepted but accommodated into the whole mandala. In this case, P13 started coloring a space with a wrong color and then decided to combine both colors throughout the mandala’s layer: “you just have to carry on, you can’t undo, it needs to go with the mandala” (P13). This is an important finding highlighting the values of acceptance and reappraisal that come from mandala coloring (Brown & Ryan, Citation2003).

3.3. Temporal unfolding of mandala coloring sessions

We now describe the way in which participants prepare for their mandala coloring sessions, the social context of this practice, and the range of practices they engage in with their completed colored mandalas.

Preparing for Mandala Coloring. In order to start coloring, people roughly plan materials and colors as indicated by 5 participants: “I lay them out, that is part of it […] and they (art materials) have to go back once you’re finished!” (P17). This resembles a ritual-like process that marks the entering into a special time and sacred place, which allows the intimate connection with mandala coloring to unfold: “I have what everybody calls my corner. So it’s just where I sit and I’ve always sat since my children were small. I can have a cup of tea next to me and […] got a lovely view over the trees, so it seems to be very nice and peaceful for me“ (P5). With respect to the choice of colors, the findings suggest that most mandalas tend to be colored with a limited set of three to five colors (): “I kind of like to experiment in mixing tones, and sticking with one particular color palette and theme” (P14). Regarding the geometry, all participants mentioned that selecting the mandala to color, based on their geometry, tends to be somehow open: “I usually get them from a book; I don’t go systematically but choose the one I like the most in that moment” (P4, ). This quote indicates the value of browsing a set of uncolored mandalas in order to choose the one that participants resonate with in the moment. Interestingly, from the choice of the four mandalas given to the participants in the face-to-face interviews shown in , mandalas C-F, all chose mandala F with the exception of P13, who chose mandala C. Participants reported that mandala C was generally avoided because of its outline: “I don’t like how thick the lines are, it looks a little less delicate” (P14), “seeing the lines like that, it feels almost angry” (P15). This outcome brings up the importance of the mandala’s geometry, as for example, participants found mandala D too intricate and challenging to color in: “I find it far too busy” (P12), and mandala E too enclosed and with geometric spaces such as triangles that would make them feel uncomfortable to color in: “I don’t like this one, it’s too geometric” (P16). On the other hand, mandala F offered better opportunities for self-expression: “I like the combination of borders, and the dots, and bigger spaces there” (P17).

Figure 5. Mandalas colored by our participants from the online interviews P5 (A) and P4 (B), and the choice of four mandalas to color in the face-to-face interviews (C-F).

Sharing the Practice and Space with Others. The way in which practicants prepare their environment prior to coloring was described by 16 participants. The setting up stage seems to be what helps them get grounded and ready for the practice. Such safe space is predominantly within one’s home (19 participants), but we also found accounts of nature-based places that people consider sacred: “at home, I do them all the time. But sometimes if I’m not in a great place, I will go down to the beach [to create the mandalas]” (P16). This illustrative quote is interesting, suggesting that the restorative power of nature (Kaplan, Citation1995) can be leveraged within the mandala coloring practice. With respect to the social context, participants mentioned the presence of trusted others with whom they share the space of mandala coloring but not the practice itself. The typical example is coloring a mandala in the living room while one’s partner reads a book. Only occasionally, people would color in group settings: “everyone had their own personal little bit [parts to color] but it was a part of the whole” (P18), or alongside trusted others: “I love looking at what my grandma’s coloring because she uses some color combinations I wouldn’t think of, and I wonder what made her choose that” (P21). Interestingly, participants mentioned that they would not feel comfortable with unfamiliar people. In particular, most interviewees (16 participants) considered mandala coloring an activity during which they open themselves up, and therefore would not like to do something that personal, for example, in public spaces: “I had surgery and I took the mandala coloring in [the hospital setting] but it’s not the same, I’m not relaxed enough, I’m just on edge because is not my coloring place” (P10). Therefore, the spatial and temporal context in which the coloring of the mandala takes place is important, as this should be a space and a time in which the person feels safe. In contrast with previous work that suggests mindfulness training on the go (Cheng et al., Citation2016), these findings imply the need for a sacred space so that coloring mandala properly unfolds.

Completed Colored Mandalas. Most participants mentioned that they like to finish each mandala in one session: “I try to finish the mandala in one sit. If I have to leave before, I feel like I should’ve finished it and I want to go back and finish it” (P21). This interest in completion suggests the need for closure and the importance of supporting it through mandala’s size and geometry, i.e. not too large that would need more than one session. Findings also indicate that almost all participants keep hold of their completed colored mandalas as organized collections. They store them within precious boxes or albums in private spaces within one’s home, and often in chronological order: “I always date it with a nice pen, with the date I finished it” (P17). By capturing the metadata of the coloring experience and then storing the mandalas, people attempt a sense of continuity within the practice. These collections of colored mandalas can serve important remembering and reflecting functions. Indeed, over two-thirds of participants mentioned that they would occasionally browse through their old colored mandalas and that in doing so they remember how they were feeling whilst coloring: “as if the mandala could convey the feeling you had while coloring it” (P21). This is an unexpected yet relevant finding suggesting mandala’s value for capturing and storing emotional memories.

3.3.1. Analog vs digital affordances for mandala coloring

An appetite for technology to be used for mandala coloring came up during the interviews, with 17 out of 21 participants having used mobile applications to color mandalas. However, such interest in the digital space does not seem to be fulfilled with current commercially available apps. Interestingly, the main affordances of the analog practice on paper and using color pencils were further unpacked, while participants described their negative experience with such apps. We now describe them together with the main digital affordances and challenges as identified by participants, and how they can inform novel designs for movement-based mindfulness technologies more broadly, and mandala coloring technologies in particular.

Instantaneous, Perfect Coloring of Digital Mandalas. When inquired about coloring mandalas digitally, most participants expressed an interest. Nevertheless, the 17 participants who had tried mandala coloring apps such as Pigment or Colorfy failed to enjoy and to adopt them as their experience with such apps was often problematic: “I don’t like that you can just color by tapping on the screen, I like to work it out myself, slowly color it” (P12). A main limitation of such apps relates to how the mandala coloring practice is mapped onto the digital space with a focus on the final image rather than on the process of coloring: “you’re thinking more about … I think because then you’re thinking more about what it looks like, as opposed to how it is just to do it“ (P5). Generally, such apps seem to deliberately eliminate the coloring’s slow and continuous movement supporting, instead, the quick generation of a colored mandala with no imperfections (Daudén Roquet & Sas, Citation2019): “I think the coloring movement is very important […] there is much more of a connection: [tap] is different [than] when you write or color which is softer or more continuous […] actual physical act is important to me, and that’s how I remember” (P15). The avoidance of imperfections was further supported by allowing users to undo actions (Daudén Roquet & Sas, Citation2019), which prevents the acceptance and accommodation of mistakes. Nevertheless, these are mandala coloring affordances that participants found key in their analog practice and missed in the digital experience: “I don’t like [the app] because of the [way it can erase] imperfections […] because [mistakes are] very organic and surprise you as beautiful” (P16). Similarly, the coloring of the mandala was facilitated digitally by allowing to zoom in, yet this disrupted the structured geometry, hence the coloring rhythm. Furthermore, we found that the coloring affordances are at the core of mandala coloring practice. However, the limited use of materials for coloring in digital mandalas hinders such experience: “I think I’m missing the pens (the smell, choosing them, holding them)” (P20). This echoes previous findings on the role of different art materials and their properties for expressing intimate sensations and emotions (Lazar et al., Citation2018).

Augmenting Mandala Coloring via Tailored Experiences. One of the main motivations to use mobile applications for mandala coloring was to access a wider range of mandala geometries, which would also be less expensive than mandala coloring books. Moreover, participants expected technology to increase the potential for personalization. For example, by allowing to modify pre-drawn mandalas or to draw bespoke ones from scratch: “the benefit of an app would be that you could build the mandala, and then you could make it the whole thing: production and design” (P17). This quote illustrates similar views expressed by more than half of participants who perceive the drawing of a geometric mandala as a high-skilled process. While lacking skills for drawing mandala’s geometry, participants would, however, like to be able to do it, in order to increase their sense of agency and expressiveness while coloring a mandala: “if I could get the images out of my head, through my eyes, onto a piece of paper” (P20). Yet, 14 participants never attempted to draw a mandala due to lack of skills. To conclude, findings indicate strong mental wellbeing benefits of the act of coloring the mandala’s geometry, as well as those linked to the ritualistic aspects of the practice. Participants also expressed growing interest in digital technologies for mandala coloring. According to the interviews, such technologies are expected to allow them to expand the affordances of the analog practice. Interestingly, however, our findings also suggest that the current mobile apps purposefully designed for mandala coloring fail to account for its key qualities.

3.4. Summary

Findings from this study detail how mandala coloring is adopted as a practice for mental wellbeing as it allows for self-expression through slowly and mindfully coloring an intricate pattern, which becomes a safe space to make and accept mistakes and imperfections as part of the experience. In turn, these findings informed the design of Anima for augmenting mandala coloring, which is detailed in the next section.

4. Design of a working exemplar prototype for augmenting mandala coloring

Anima is a working exemplar prototype (Sas et al., Citation2014), defined as an instantiation or design exemplar illustrating an abstract principle. The main role of working exemplar prototypes, such as Anima, is both to inspire designers’ thinking of such principles, and to act as a possible placeholder (rather than design solution) within a novel and yet to be explored design space (Sas et al., Citation2014). Such working exemplars have generative rather than evaluative purposes (Hoök & Lowgren, Citation2012; Hutchinson et al., Citation2003; Sas, Davies et al., Citation2020) emphasizing their playful exploration, while offering the advantage of being easy to understand by naïve users (Boehner et al., Citation2007).

Therefore, the goal of Anima is to bring forward the exploration of a novel design space for non-static focused attention mindfulness technologies, with an external focus of attention. The key design principle Anima illustrates is the decoupling of two main aspects of FAM practices: the training of focused attention and the monitoring of mindfulness states during the practice.

The design decision of separating onto two different displays the coloring of the mandala – i.e. the main focus of attention – and the generation of colors based on the mindfulness states during the practice – i.e. the monitoring – was grounded on the findings from Study 1 and previous work evaluating mandala coloring apps (Daudén Roquet & Sas, Citation2019). Furthermore, we aimed to explore the way in which brain activity could be materialized in order to guide the mindfulness practice, which has been little explored in HCI.

The design of the working exemplar prototype was inspired by the traditional practice of mandala coloring, as explored in Study 1, in which the interactions between the mandala and the used colors are key. In Jung’s theory, the psychotherapist that introduced mandala coloring to Western culture for mental wellbeing, anima represents the inner personality that allows bringing attention toward unconscious parts of the self (Slegelis, Citation1987). Similarly, Anima aims to facilitate the FAM practice of mandala coloring through the materialization of mindfulness states on the peripheral color palette, in order to facilitate the FAM practice of mandala coloring (Fincher, Citation2000; Malchiodi, Citation2011). Its design was also inspired by traditional coloring and its interaction with the materials: placed within reach, there when needed, yet peripheral. We now provide an overview of the system and describe the design choices regarding colors, their esthetic appearance and spatial arrangement on the peripheral palette.

4.1. Overview of the system

The Anima working exemplar prototype consists of three components (): a brain activity headband, an adaptive color palette, and a mandala coloring canvas. Each of these components were carefully designed to fulfill a specific goal (). First, the brain activity headband is used to non-obtrusively access the person’s mindfulness states during mandala coloring. Second, the tablet-based adaptive color palette is used as a peripheral interface for monitoring the FAM practice, as it provides new colors that are generated based on the current mindfulness state. Finally, the tablet-based canvas aims to recreate the traditional practice of mandala coloring to train focused attention by coloring with conscious, slow, and continuous hand movements. also shows the way in which the new colors are generated based on the mindfulness states sensed by the brain activity headband and is further detailed in the section ‘Mapping Brain Activity onto Colors’ below. Each of these components is described below.

Figure 6. This diagram shows an overview of the system by describing the three components of Anima (i.e. brain activity headband, adaptive color palette and mandala coloring canvas on two Android tablets respectively) and the way they function together.

4.1.1. Sensing mindfulness states using a wearable brain activity headband

The first component of Anima is Muse (MuseTM – Meditation Made Easy with the Muse Headband, Citationn.d.), a wearable, commercial EEG headband for monitoring brain activity in order to infer mindfulness states in real-time. Through its four cutaneous channel electrodes capturing α, β, γ, and θ brain waves (Krigolson et al., Citation2017), Muse has been shown to provide valid and reliable measurements of event-related brain potentials (Krigolson et al., Citation2017; Richer et al., Citation2018). Previous work has also linked each of these brain waves with specific mental states (Richer et al., Citation2018), particularly during mindfulness training, from which mindfulness states can be clearly identified (Hölzel et al., Citation2011; Sas & Chopra, Citation2015).

4.1.2. Monitoring the mindfulness practice with a peripheral adaptive color palette

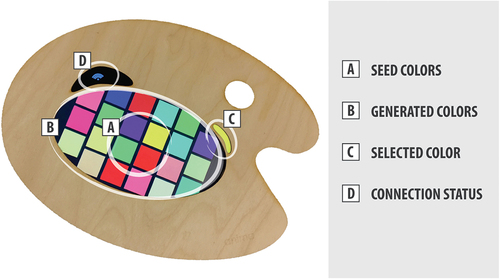

The second component is an adaptive color palette, for which we designed a hybrid artifact consisting of a tablet enclosed in a bespoke, wooden laser cut made painter palette (). The aim of the palette is to act as a peripheral display to facilitate the open monitoring of the mindfulness practice during mandala coloring, as it provides new colors based on the unfolding mental states throughout the session. The interface was developed as an Android app that was installed on a Samsung tablet. Besides the generated colors, the palette also includes the original four seed colors selected by the user (see and section ‘Mapping Brain Activity onto Colors’ below). The palette also offers an indication of the currently selected color to be used on the canvas, and an icon showing the connection status with the Muse’s headband.

Figure 7. Close up diagram of Anima’s color palette identifying its main parts: (A) four seed colors originally selected by the user, (B) generated colors based on the mindfulness states, (C) current selected color to use on mandala coloring canvas, and (D) connection status with brain activity headband.

4.1.3. Training focused attention through mandala coloring

Finally, the third component of Anima is a digital canvas for mandala coloring. The main goal of the canvas was to recreate the analog practice of mandala coloring in order to facilitate the training of focused attention and self-expression. Therefore, we developed a website, which provided the geometry of a mandala to be colored in with a stylus as if it was on paper (Daudén Roquet & Sas, Citation2019): no eraser or undo actions, no zooming in and out, and no color by tapping into the spaces. To select a color, the user would simply tap on that preferred color from the adaptive color palette. It would then be automatically loaded onto the canvas by sending the RGB value from the Android app to the website using web sockets, as shown in .

4.2. Mapping brain activity onto colors

An important design decision focused on how mindful versus non-mindful states could be distinctively represented through color. Here, the design was informed by Gombrich’s concept of beholder’s share, in which one’s prior experiences and emotional memories guide the process of decoding visual information, determining its meaning, and interpreting it (Koenderink et al., Citation2001). For that reason, the color-based metaphorical representation of mindfulness states was based on an initial user selection of colors ().

Drawing from mindfulness literature and the traditional practice of mandala coloring indicating that mandalas are traditionally created using four core colors (Tucci, Citation2001) as well as the findings from Study 1 presented in this paper, the initial choice of colors consisted of a set of four colors – which we call seed colors (). Indeed, the first study’s findings indicated that people who color mandala regularly, use in average between 3 and 5 colors per mandala. These are usually selected at the start of the session, and provide the full range of colors throughout the entire mandala coloring session.

For Anima’s design, the seed colors are to be chosen by each participant at the beginning of the mandala coloring session, and used as a yardstick to represent their mindfulness state. In particular, subsequent state changes (i.e. becoming more or less mindful) were materialized as changes applied to these seed colors. For the color modification, we draw further inspiration from work on color theory (Chua, Citation2012) suggesting that hue, saturation, and brightness can increase expressiveness in information visualization (Cyr et al., Citation2010; Lichtlé, Citation2007); and that low saturated colors with low hue can support calm states (Bartram et al., Citation2017). While saturation and brightness levels were open for modification, we kept the hue constant to limit the range of distinct colors. Generation was deliberately ambiguous and subtle to not distract from the main focus of coloring the mandala (Gaver et al., Citation2003), yet informed by participants’ mindfulness states (Richer et al., Citation2018).

To monitor mindful and non-mindful states, we used alpha and beta brain activity frequencies as increases in alpha and beta frequencies have been linked to attention modulation in focused attention practices in related neuroscience work (Irrmischer et al., Citation2018; Wahbeh et al., Citation2018). Thus, when a participant reached a more mindful state (i.e. increase in alpha and beta), the system generated a more muted color. This was done by lowering the saturation and increasing the brightness of a seed color by 10%. Accordingly, to represent a less mindful state (i.e. decrease in alpha and beta), the system generated a new stronger color by increasing the saturation and lowering the brightness of a seed color. On reflection, Anima’s design provides at least as much opportunity for self-expression through the choice of the four seed colors, as the paper and pencil version, as well as additional opportunity through the generated colors.

4.3. Palette design: color choice, appearance & placement

Regarding the interface of the Anima’s adaptive color palette (), we conducted a series of design iterations to find the appropriate design for the working exemplar prototype. For this, we draw inspiration from the traditional painter’s color palette while aiming also to provide support for open monitoring during the mindfulness practice of mandala coloring.

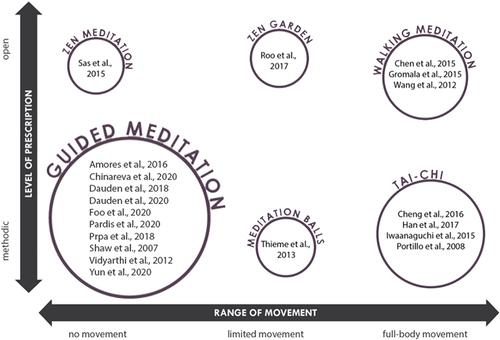

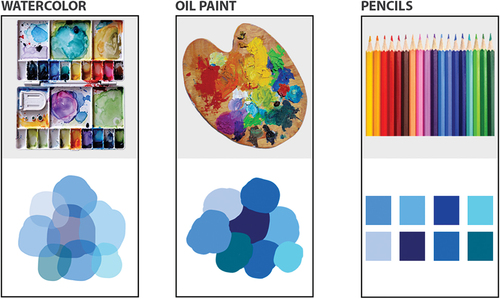

For instance, we explored colors’ physical appearance on the palette in terms of their shape and size. Inspired by work on materials for self-expression (Giaccardi & Karana, Citation2015; Lazar et al., Citation2018), we looked into art materials such as watercolors, oil paint and pencils (). We decided to use digital coloring due to its simplicity to programmatically augment the practice, and its use of metaphor of pencil coloring via the stylus. Digital coloring also leads to distinct, atomic color generation and selection which can be associated with distinct mental states.

Figure 8. This image shows the design exploration of the mapping of mindfulness states into colors, by drawing from different materials: watercolor (left), oil paint (middle), pencils (right).

In terms of color appearance, we considered a variety of shapes, like the ones shown in , and decided to display colors as solid cells as the interaction and meaning-making processes were best facilitated with the grid. The cells were squares of 1 × 1 inch, ensuring that the number of displayed colors resembled the number of colors provided by a case of coloring pencils. Indeed, based on the palette’s screen state and the size of the cells, up to 22 colors (4 seed and 18 generated) could be displayed on the palette without erasing any previous colors.

For the frequency and temporal addition of new colors, we initially tried to replace old colors with new ones. However, this felt like the system was erasing one’s prior experiences. After initial testing, we chose new colors to appear every 30 seconds, until the 22-color palette was full. Thus, half-way through a 20-min coloring session – average time of mandala coloring according to study 1 presented and previous literature (Curry & Kasser, Citation2005)- the user would have access to a full-color palette, which no longer evolves.

Finally, we experimented with colors’ spatial placement on the palette. After a few design iterations, we decided to place colors in random locations rather than chronologically aligned to make difficult the identification of the most recently generated color, and to ambiguously link it to the current mindfulness state. We expected that this choice would limit the user’s adoption of a judgmental attitude toward one’s performance (e.g., “I am not doing it right” thoughts), while still providing subtle monitoring of one’s FAM practice.

5. Study 2: Anima’s exploration workshops

Anima was developed to explore a novel design space for mindfulness technologies in which the training of focused attention and open monitoring are decoupled into two distinct, yet connected, interfaces. Because of this, the purpose of the workshops was twofold: not merely Anima’s evaluation but the exploration of its generative role to help us understand key design principles underpinning this new design space (Sas et al., Citation2014). We conducted a total of five workshops with two to three participants in each (), focusing on the following research questions:

Figure 9. Photographs of the setting of two distinct moments during the workshop sessions. On the left, participant coloring a mandala with Anima (individual session). On the right, follow up group discussion.

How should metaphorical representations of mindfulness states, captured through brain activity, be designed to be both recognizable by users and yet open for interpretation?

How do people make sense of the metaphorical representations of their mindfulness states?

How does the decoupling of focused attention and its monitoring impact on the mindfulness training through mandala coloring?

5.1. Methodology

5.1.1. Participants

We recruited a total of 12 participants through university mailing lists and posters around campus. Participation was incentivized with an equivalent of a $15 Amazon voucher. All participants had regularly practiced mandala coloring prior to the study, with 2 participants having colored mandalas monthly, five more than once a month and five on a weekly basis. Furthermore, all participants had engaged with mandala coloring long-term for at least the last year, with 7 participants having been coloring mandalas regularly for 1–2 years, three for the past 3–5 years and two for over 5 years.

Regarding participants’ demographics, nine identified as women and three as men, with an average age of 32 years old (SD = 10.02). Participants’ nationalities were varied, with 4 participants identified as British, two Nepalese, two Peruvian, and four other (i.e. Costa Rican, Greek, Russian and Turkish).

5.1.2. Method

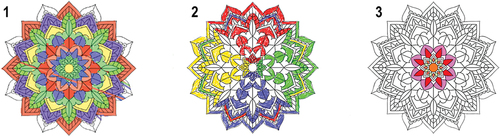

Upon arrival, each participant was provided with a Muse EEG headband (MuseTM – Meditation Made Easy with the Muse Headband, Citationn.d.). After the setup, participants were asked to select the four seed colors, and individually color the digital mandala provided to them (all participants had the same mandala) () using Anima’s canvas and palette. This activity took place in a separate room for each participant to explore the working exemplar in a private space. The inner workings and mappings of the working exemplar prototype were not disclosed at this stage in order to encourage Anima’s unbiased exploration. After 20 minutes (time allocated based on findings from Study 1 and following previous studies on mandala coloring (Babouchkina & Robbins, Citation2015; Curry & Kasser, Citation2005)), participants were notified and given the choice to either stop coloring, or to spend 5 more minutes to finish up.

Figure 10. Mandalas colored during the workshop by participants with different motivations: mandala 1 is by P7 for mindfulness training; mandala 2 is by P8 for spiritual tradition; and mandala 3 is by P1 for artistic purpose.

Then, all participants were brought together to start the group discussion, where they could share their final color palette with the group to be used as a starting point for discussion (). First, participants were prompted to share with the group their motivations for coloring mandala and to explain their own understanding of how Anima worked. Then, we disclosed to participants how Anima’s mapping of mindfulness states to generated colors worked. After the Anima’s color-based representations of mindfulness states were disclosed to the group, participants were invited to discuss Anima’s mapping of mindfulness states to colors, the colors’ frequency of appearance, and their placement, shape and size. We also provided alternative design choices for the mapping through different shapes, size and color arrangements identified through our previous design exploration, and encouraged participants to design their own palette to materialize mindfulness states during mandala coloring.

5.1.3. Data collection and analysis

All workshops were audio and video recorded, and the design materials such as colored mandalas, and generated palettes were photographed. Conversations were transcribed and coded using Atlas.ti/8 software for qualitative analysis. We followed a hybrid approach to coding and theme development (Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, Citation2006). For the deductive coding, we draw upon a conceptual framework developed from prior work including codes such as materialization of mental states, focused attention, open monitoring, attention regulation in focused attention. For the inductive coding, we used the new codes that emerged from the data such as mapping of mental states to the color palette, and its spatio-temporal arrangement. All brain activity data was stored and processed locally on the tablet of Anima’s color palette. EEG data was analyzed using power analysis to detect the dominant brain waves (Krigolson et al., Citation2017; Richer et al., Citation2018).

5.2. Findings

We now report the findings from the workshops highlighting participants’ motivation to color mandalas regularly in their everyday lives, and the ways in which their experience of mandala coloring has been impacted by the use of Anima. Further, we describe how participants made sense of Anima and how their mindfulness states were materialized into colors on the peripheral interface. They also provided suggestions for future brain-computer interfaces for mindfulness training during mandala coloring.

5.2.1. Motivation for coloring mandalas

Findings indicate three distinct motives for mandala coloring (): mindfulness benefits, spiritual motives, and artistic ones. The most prevalent motive was for the mental wellbeing benefits (Curry & Kasser, Citation2005) entailed by this form of mindfulness training (P2, P3, P4, P6, P7, P10, P11, P12): “for me, I never see mandala as a piece of work. It’s just an instrument for me to relax and be more mindful” (P2), “it gets you to see how you’re feeling on a page, without having to necessarily be too explicit, like writing” (P3). The other two motives were less emphasized, being shared by two participants each so future work should further confirm them. The spiritual reasons were inspired from Nepalese Buddhism (P8, P9), which embeds mindfulness training but not as the main goal: “having the base colors as they should be (red, green, yellow and blue), because maybe we are trained that way” (P9), and artistic purposes (P1, P5) with the goal of creating beautiful images: “with mandalas I don’t have a specific idea or goal in mind as ideas flow more naturally [than when I do other types of art]” (P5).

Findings also indicate how these motivations are reflected in different ways of coloring mandala. Participants who color for mindfulness benefits and spiritual tradition fill in the mandalas layer by layer, as illustrated in . They aim for completeness and have a specific approach to handling mistakes: going over the lines, by allowing, accepting, and integrating mistakes in the mandala coloring: “if I make a mistake, I have to incorporate it” (P10). This is an important outcome indicating the value of mistakes in signaling less mindful moments, as well as the opportunities they offer for practicing non-judgmental acceptance (Clark et al., Citation2015; Vago & Silbersweig, Citation2012). In contrast, in P1’s mandala we can see that the goal was to create a detailed and esthetically perfect image, with few mistakes whose acceptance has not been emphasized.

Regardless of their motivation, all participants expressed how the coloring of the mandala allowed them to express themselves in a non-judgmental way that facilitated self-reflection: “you can reflect and see it through the colors, because sometimes you have so much in your brain you can’t keep it all in – it’s like a release” (P11). These outcomes are important, indicating that mandala coloring, as a mindfulness practice rooted in Buddhist traditions (Tucci, Citation2001), is predominantly used for mental wellbeing (Kellogg et al., Citation1977), although our participants’ recruitment did not focus on this vulnerable user group.

5.2.2. Interactions with the Anima’s peripheral palette and digital canvas

Most participants reported that they really enjoyed the experience of using Anima: “It really felt nice, when I was coloring I didn’t want to stop, and when you came earlier I thought ‘it’s only been 5 minutes, how … why?’” (P8). Although 6 participants found it initially challenging to move from coloring on paper to coloring on a tablet (P1, P2, P5, P8, P9, P10): “I loved getting patient with it (the digital canvas) and getting good at it, which was really rewarding … it’s not great, full of mistakes, but I was quite happy with it” (P10), in a couple of minutes all participants mentioned that they reached a more mindful state, and seven even wanted to continue coloring for longer (average Anima coloring time among participants was 23.5 minutes). We now describe participants’ experience with the peripheral palette and the digital canvas, and how different motivations for engaging in mandala coloring impacted on their use.

Findings from the analysis of participants’ interaction with the palette, indicate that from the 22 provided colors (4 seed colors, and 18 generated) the average number of colors selected to use was 5.9, including on average 2.8 seed colors, and 3.1 generated colors. This suggests that we may have provided more colors than needed; however, as we shall see later, the number of generated colors provided both richer choices to select the color to use, as well as real-time feedback on the mindfulness states. To explore the latter, we calculated the number of colors mapping mindful vs. less mindful states, and findings on the palettes’ colors indicate that an average of 11.7 out of 18 generated colors represented mindfulness states. This suggests that for the first half of the session, while colors were generated, participants experienced mindfulness states about 65% of the time.

Another interesting finding is that despite this rather limited use of merely less than a third of the colors provided on the palette, seven participants across all three motivation-based groups expressed a desire for more colors. A closer look into this revealed two main reasons. First, there was a preference for colors varying both in saturation/brightness level, and hue: “I wanted more variety” (P11). Such findings suggest that the generated colors extend the range of choice beyond the four seed colors, which in turn elicit expectations for additional colors beyond the generated ones. Indeed, a third of participants mentioned their preference for more and distinct colors.

On reflection, we deliberately constrained the breadth of colors’ hues so that they would not distract attention from the main coloring task. This design decision was notably supported by three participants: “it’s boring when you have so many options” (P5). Driving the color generation solely on the basis on mindfulness states, and the four seed colors, meant that some of the colors were similar and difficult to differentiate, which in turn restricted the range of diverse generated colors. Moreover, most participants across the three groups made use of bright colors, which were also less represented on the palettes.