Abstract

Citizen Development (CD) is a method of delivering low-code no-code (LCNC) development that empowers subject matter experts to design, develop, and deploy applications into production as though they were full-on, experienced coders. This paper explores teachers’ perceptions around the potential for, and enactment of LCNC in our education system. Workshops, surveys, and interviews were conducted with in-service teachers. Teachers are open to improving their digital skills. Nevertheless, some teachers fear technology and are reluctant to embrace change. Our results indicate that it is timely to leverage the increased use of technologies in the classroom before teaching reverts to pre-pandemic norms of “face-to-face.” CD provides an excellent opportunity to introduce teachers and students to aspects of computer science without placing demands on them to develop technical skills. The paper provides considerations for the adoption of CD in our education system and in initial teacher education programs.

Introduction

In this digital era, it is clear we need to do education differently (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO], Citation2020) and prepare students to become competent and confident engaging with digital technologies, potentially recognizing opportunities in STEM careers. Indeed during, and as we emerged from the COVID-19 pandemic, we have witnessed how education was mediated by technology to facilitate our young people’s learning and development. Technology, computer systems, and mobile application development enabled educational progression and the continuity of learning and teaching (Blau et al., Citation2020).

Accepted wisdom that everyone should learn to code (Resnick, Citation2013) certainly seems to apply to Education 4.0, where technology is ubiquitous in society and creating new possibilities, and challenges, for learning and teaching in classrooms and schools (Salmon, Citation2019). Interest in providing Computer Science (CS) or programming in school classrooms has resurfaced due to initiatives such as CSforALL (https://www.csforall.org/) and Code.org (https://code.org/), dedicated to disseminating CS education (Denning et al., Citation2017). Other initiatives have focused on developing specific low-code and/or no-code (LCNC) tools for programming initiation with block programming widespread, such as the Scratch program developed by the MIT Lifelong Kindergarten Lab (Brennan & Resnick, Citation2012). Technology can often be misperceived to have a high entry barrier whereby only students with technical skills can thrive in this area (Selwyn, Citation2006a).

This study was designed to explore how teachers perceive the potential value of Citizen Development (CD) and LCNC in their teaching practices in post-primary (secondary) schools in Ireland. The research question guiding the intervention was: Can Citizen Development be of potential value and use to secondary school teachers? To address this question, the research explores:

What are teachers’ attitudes toward Citizen Development?

What are the challenges toward the integration of Citizen Development into their own teaching practices?

What are teachers’ perceptions of a LCNC training program and its applicability to a school environment?

Background

Citizen Development

In the age of disruption and transformation, there are growing demands for people to be digital literate and have sufficient applied technical skills to play an active role in modern businesses and society (Goodfellow, Citation2011). In response to such demands, Citizen Development is a growing movement which describes a new trend across businesses to empower traditionally non-IT employees to collaborate with IT professionals to build effective and innovative applications (Carroll & Maher, Citation2023). Indeed, to successfully lead digital innovations and transformations within organizations, there is a focus on digital skills requiring greater focus on people, mindset, culture, and new norms (Carroll & Conboy, Citation2020; Deuze, Citation2006; Hemerling et al., Citation2018). To harness people’s talents, it is evident that people must feel empowered to experiment and learn from success or failure. However, within a higher education setting, students can often feed a disconnect between digital innovations and delivering digital solutions (Selwyn, Citation2006b). In addition, just as the pandemic accelerated the need for organizations to change though digital transformation, it laid bare the massive global shortage of skilled software developers needed to deliver and operationalize digital transformation (Carroll et al., Citation2021). Against this backdrop, we are witnessing a new method of delivering low-code development to accelerate and expand new second and third-level educational opportunities through Citizen Development.

Citizen Development offers significant potential to embed new applied digital skills initiatives by empowering students to bridge the gap in meeting growing digital literacy and skills demands, for example, building applications over rapid timeframes. However, developing an application from concept to launch can be a complex process requiring specific guidelines (Dobrigkeit et al., Citation2020) to take advantage of LCNC app-building solutions. CD offers significant potential to support this by empowering students to bridge the gap from ideation, prototyping, and deploying digital solutions to meet the growing demand. In addition, the CD method hides the sophistication and complexity of coding but empowers subject matter experts—allowing us to view digital solutions as building blocks rather than a complex process (Carroll et al., Citation2021).

To support bridging this gap, there are growing number of LCNC vendors and training resources entering the marketplace and some already well-established platforms, for example, Microsoft Power Apps, and training resources, such as Project Management Institute (PMI) courses (https://www.pmi.org/citizen-developer/). CD offers significant potential for new educational initiatives by empowering students to bridge the gap in meeting growing digital skills demands and the freedom to experiment with new applications development. However, insight on the potential for CD in second-level education is lacking.

Education system in Ireland and digital technology adoption

To place the evolution of computing, coding, CD and digital transformation within education in context, a brief account of the structure of the Irish education system is provided. Education in Ireland is centralized, and the Department of Education determine policy and the national curriculum. Secondary education consists of a three-year Junior Cycle (lower secondary), followed by a three-year Senior Cycle (upper secondary). During the final two years of their secondary education, young people prepare for a high-stakes state examination, the Leaving Certificate (LC), on which entry to higher education is determined. In 2016, Senior Cycle Reform began with the aim of reviewing the Senior Cycle structure and purposes and as part of this reform, ‘new’ subjects were introduced into the Senior Cycle curriculum, one of which was Leaving Certificate Computer Science (LCCS). The LCCS specification was seen as a landmark development in Irish education (Connolly et al., Citation2022). Along with the two highly innovative Junior Cycle short courses (100 h each) in Coding and Digital Media Literacy, introduced as part of the systemic reform of Junior Cycle in Irish schools, LCCS is central to the national STEM Education policy (Department of Education and Skills, Citation2016).

The Teaching Council is the statutory body for teaching in Ireland and maintains the register of teachers and accredited initial teacher education (ITE) [or pre-service] programs. Their requirements for teacher education program accreditation specify details such as the program entry requirements, subject requirements, a partnership model for school placement and curriculum content (Teaching Council, Citation2022). Another requirement is digital literacy and the use of digital technologies to support teaching, learning and assessment as well as the integration of digital skills across all teacher education programs affording opportunities for student teachers to explore new and emerging technologies (Schrum et al., Citation2007; Teaching Council, Citation2022).

Understanding teacher beliefs and practices with technology is important (Galvis, Citation2012; Kim et al., Citation2013; Levin & Wadmany, Citation2006), as there are some barriers facing teachers in the integration of technology (Chai & Lim, Citation2011). A study by Ertmer (Citation1999) identified and divided technology-use challenges into first-order barriers (extrinsic to a teacher’s control e.g., lack of access to equipment/resources, training, administrative and technical support) and second-order barriers (intrinsic to a teacher e.g., viewpoints, confidence, attitudes, beliefs, values). More recent studies such as O’Neal et al. (Citation2017) “suggest that, although teachers see the value of technology for teaching and learning, they require more guidance on what constitutes 21st-century skills and how to effectively integrate technology” (p.1). While access to resources and technology tools can be potential barriers (Francom, Citation2016), teachers participating in this research have existing access to certain software. The schools where participating teachers teach are affiliated with either Microsoft or Google. For example, for teachers affiliated with Microsoft, the LCNC Power Apps application is included in their Microsoft suite for schools.

Existing mindsets, one’s beliefs and attitudes toward technology can be another major barrier in using technology (Chai & Lim, Citation2011; Ertmer et al., Citation2012, Citation2015; Hew & Brush, Citation2007). Ertmer (Citation1999, Citation2012) found that the best way to engage teachers was to increase knowledge and skills which in turn, potentially changes beliefs and attitudes. Attitudes and beliefs can be influenced by fear of technology, fear of failure or fear of change. The effect of fear may influence the adoption of technology (Al-Maroof et al., Citation2023). Thus, supportive strategies may be needed to overcome barriers and are discussed later in this paper.

Method

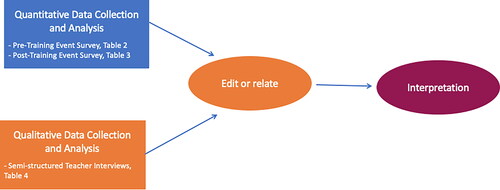

This research study engaged in a mixed methods approach (Hesse-Biber & Burke Johnson, Citation2015). By using multiple approaches, a much richer insight was achieved to develop a greater understanding of the topic (Creswell & Clark, Citation2017). The data gathering techniques included quantitative pre- and post- training surveys and qualitatively coded teacher interviews. All ethical concerns were appropriately addressed (British Educational Research Association (BERA), Citation2018) .

Figure 1. Research method (adapted from Harvard Catalyst, Citationn.d.).

Research participants

Eighteen secondary school teachers registered for an online PMI training course on Citizen Development. Of the 18 teachers who registered for the CD training, 50% were Computer Science teachers, the remainder divided between teachers of Business Studies (33%) and the Humanities (17%). Invitations to the PMI training event were extended to teachers through teacher associations: notably Computers in Education Society of Ireland (CESI) and Business Studies Teachers’ Association of Ireland (BSTAI). Additionally, the event was advertised on social media and through direct email to past cohorts of a Professional Master of Education (PME) ITE (pre-service) teaching degree from one university.

Given that CS is a comparatively new subject in Irish schools and with a relatively small number of qualified CS teachers nationally (Connolly & Kirwan, Citation2023) the sample size of CS participants was small. Additionally, demands associated on all teachers impacted the number of teachers (N = 18) who volunteered for this study.

Research design

The online training event was held over two evenings. Teachers completed customized surveys on both nights; one on registration, before the Citizen Development training, and one directly after the training event. Whereas 18 teachers had registered and completed the pre-training survey, only eight teachers attended the entire training and completed both surveys; of these, four teachers agreed to be interviewed, two of whom teach CS and two of whom teach Business Studies.

The training event was held online via Zoom. The event consisted of an introduction to Citizen Development, access to the ninety-minute PMI Citizen Developer Foundation course and a general discussion afterwards. Each of the teachers received a promotional code from PMI to access the training. This allowed the teachers to register for the PMI Citizen Developer Foundation course at no cost. The course covered three modules detailed in (Project Management Institute (PMI), Citation2022).

Table 1. Project Management Institute (PMI) Citizen Developer Foundation course modules.

Data collection and analysis

There were three forms of data collection:

a pre-training survey – 18 respondents.

a post-training survey – 8 respondents

semi-structured interviews – four participants

Survey instrument

The survey design for both surveys drew on existing validated instruments used for measuring attitudinal changes, course outcomes and usability. Items were adapted for Citizen Development and LCNC. In addition, open-ended questions were appended to the post-training survey to extend and analyze fully the reasons behind closed item responses. The items were all in Likert-scale type with five anchor points ranging from 1 (Not at all Agree/Not at all Confident) to 5 (Strongly Agree/Extremely Confident). The structure of the pre-training event survey instrument is illustrated in and the post-training event survey instrument in .

Table 2. Pre-training event survey details.

Table 3. Post-training event survey details.

Interviews

To expand on data gathered from the pre- and post-training surveys (), all teachers were asked in post-training survey would they be willing to participate in an interview. Four teachers agreed to participate in in-depth semi-structured interviews which were carried out within two weeks of the training event. The timing offered the teachers sufficient time and opportunity for thought on any potential integration of Citizen Development into their teaching practices. The semi-structured interview approach allowed flexibility in questioning and probing (Cohen et al., Citation2011) and exploration of different aspects of the topic based on teacher’s answers. Teachers shared their thoughts, experiences, and opinions, on Citizen Development, affording a comprehensive understanding of the teachers’ viewpoints. Assurances of confidentiality and anonymity were stressed to the teachers in advance of the interviews. Teachers’ permissions were requested to conduct audio-recorded interviews, and upon consent, the interviews were transcribed. In adherence to the agreement with the teachers, the transcribed documents were returned to them, providing an opportunity for them to review and make any necessary clarifications or amendments to accurately reflect their statements.

Table 4. Details of semi-structured interview schedule.

Quantitative data was captured via Google Forms and analyzed manually using Microsoft Excel. Guided by Braun and Clarke (Citation2013) stages of thematic analysis, themes were identified from the qualitative data (open-ended questions, interviews) and cross-checked against the data from the survey. The data was analyzed through phases of coding guided by Charmaz (Citation2006) and the subsequent constructed categories represented processes and ideas which the teachers experienced.

Findings

The research findings and data analysis sub-themes are structured around the study’s main research question: the exploration of Citizen Development’s potential value and use for secondary school teachers. As stated earlier, although 18 teachers registered for the event and in doing so, completed the pre-training survey, in the data analysis the comparisons on pre and post surveys relate to the eight teachers who attended the training event. As stated, participants were sampled through a purposively and convenience sampling approach (Bryman, Citation2012). We acknowledge the number of teachers was low but participation in the PMI event was a voluntary exercise for teachers. The study aimed to gain a representation of teacher views at a particular time, post-covid and after their forced engagement with online learning and digital education. Also impeding participation was the low number of CS teachers in the education system, with only 34 registered with the Teaching Council (Connolly & Kirwan, Citation2023).

Teacher background and LCNC initial knowledge

All 18 teachers declared that they use some form of technology, ranging from 22% (N = 4) moderate use to 50% (N = 9) considerable use and 28% (N = 5) a great deal. The teachers explained how they use many technologies in their teaching roles at present, mostly online coding material, various apps, Google Suite and Office 365 (Teams, Word, Excel, PowerPoint). The teachers felt competent using technology to solve problems in their teaching roles ranging from “Somewhat Competent” (N = 10) to “Extremely Competent” (N = 8). The interviewed teachers (N = 4) conveyed that while their school leaders themselves may not have a strong interest in technology, they are highly supportive of the school’s IT departments. According to Teacher1, “everyone’s standards were brought up to speed” with the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic, although Teacher2 believes “there’s a long way to go yet.”

Before the training event, among the teachers there was a mixed level of understanding regarding the concept of Citizen Development. While a few teachers had a clear understanding of the term (N = 5), some (N = 6) had little or no knowledge of the concept, and others (N = 7) held different interpretations including that of digital citizenship (N = 4). Given misunderstandings around the corporate term Citizen Development, it can be inferred that five teachers (28%) had full understanding of CD and thirteen did not (72%) ().

Table 5. Existing knowledge on the concept of Citizen Development.

Additionally, teachers were asked in the pre-training survey about their familiarity with LCNC. Six teachers (33%) stated they were familiar with LCNC, while 12 (67%) stated they were not familiar with LCNC. As mentioned previously five teachers demonstrated a comprehensive understanding of the concept of CD. However, when asked specifically about their familiarity with LCNC, one teacher did not associate LCNC with Citizen Development.

Confidence and value

Perceived confidence—self- efficacy—in abilities to incorporate Citizen Development/LCNC

Confidence in teachers’ abilities to incorporate CD/LCNC into their teaching increased after completing the PMI Citizen Development Foundation course. In the pre-workshop survey with the cohort of eight teachers (those who did both pre and post surveys), when asked if they were familiar with LCNC half of the participants stated “YES” (N = 4) and half stated “NO” (N = 4). Those that replied “YES” were asked three additional questions one of which dealt with confidence in their ability to incorporate CD/LCNC into their teaching. All expressed confidence, ranging equally between slightly and moderately. After the training event, confidence was high for all eight teachers, perspectives changed positively with five of the eight self-reporting as very confident. Additionally, when teachers were asked in the post-survey if they had the ability to develop LCNC processes and solutions on their own, seven agreed with the statement. In an interview, another teacher believed the course reinforced a growth mindset.

Not all teachers have the confidence with technology that CS teachers may have. One interviewed teacher mentioned they came to the Citizen Development training event without any prior knowledge of LCNC. However, their school expect staff to possess digital technology skills and knowledge. The teacher’s shared insights regarding their teaching colleagues who are currently enrolled in teacher education programs and pursuing studies in coding. These colleagues anticipate being more receptive to incorporating technology into their teaching practices in the near future. As Teacher1 commented in their interview:

Some people are more receptive to these initiatives than others are …. maybe if some younger ones are coming out [of teacher education programs], they have a little bit more, say coding with geography or something that we’re seeing a bit of that now.

Value to teachers and students

In both surveys teachers were asked to rate the potential value of CD/LCNC in (a) their teaching career and (b) in their students’ career paths. Of the cohort of eight teachers, all perceived CD/LCNC to be of value to both teachers and students. Seventy-five percent (N = 6) perceived a strong value for both students and teachers, with 25% (N = 2) expressing slight value to both.

As we emerge from the global pandemic and a return to face-to-face teaching teachers are finding potential value in incorporating LCNC in the classroom going forward. Teacher4 explained that when young people came back from COVID-19 lockdowns and school closures there was a slight withdrawal from digital technology, that is, students wanted to be face-to-face:

Students just wanted me to explain something or just show them something … but we have to understand these kids were online, nine classes a day, some live classes – they did so much online in such a short space of two years.

Teacher3 expressed, in their interview, how LCNC could encourage young people’s interest in technology. By not “having to teach students to read the syntax and the really kind of nitty gritty of coding,” Teacher3 suggested LCNC could provide significant value as it could “grab” students’ interest quickly:

I was looking at …the value we can add to students. I think that just getting students and kids involved at a young age into technology, without having to teach them to read the syntax and the really kind of nitty gritty of coding, and just get their interest and grab it quickly. And there’s a lot of value there.

The value of that for me is seeing the kids, I suppose, involved in that learning. It’s not the kids who, you know that if you tell them something they’re going to do it - it’s the kids who you could lose.

It could be a different angle and rather than your traditional mainstream academic subjects…and you know, sometimes if people are used to working with projects or different things like that, that might be more willing to try something.

In the interviews, Teacher1 explained how keeping up to date with global trends holds great value. They expressed enthusiasm about bringing this knowledge back to the classroom and equipping students with enhanced digital skills. However, students need to be prepared to be able to use these new technologies properly. Teacher1 highlights how information literacy, copyright, and plagiarism “are not fully sinking in.” These skills are vital when using platforms such as LCNC and in the development of apps.

LCNC has potential value but only for those interested in it, and if it is not associated with more work for teachers. During the global pandemic, six of the eight teachers took the initiative to develop their coding knowledge, including third-level coding courses. However, upskilling presents certain issues. As Teacher1 pointed out in their interview “anything I do for coding I literally just do it in my own time.” According to Teacher1, certain teachers exhibit negativity or fear around the introduction of new technologies. Teacher1 believes any negativity surrounding technology and upgrading of skills has not so much to do with someone’s background, but it is related to their interest and their growth mindset:

I think their own mindset is the biggest barrier. That if you have someone who has a negative perception or they have no interest in doing it, or it’s got to be more work to them, or “why are we doing this?” That is a biggest barrier. I think, if you have someone who has some interest in it, then absolutely I think that’s going to be okay.

Attitudes

Appetite for CD/LCNC

Computer Science teachers demonstrate a higher level of optimism regarding the perceived appetite for CD in schools. From the perspective of one CS teacher interviewed, Teacher1, young people are coming into secondary school with block coding experience (e.g., Scratch, MakeCode), and are now advancing from block code to text-based coding such as Python. According to Teacher1, there has been a shift in the interests of young people toward LCNC in the last year. However, other teachers are unsure overall and have mixed responses. Although changed teaching practices during the COVID-19 pandemic have helped eradicate fear surrounding technology, Teacher3 in their interview stated there is still an element of “this is the way we’ve always done it” and ‘if it’s not broken, don’t fix it.” Teacher4, in their interview, shared a similar viewpoint:

I think sometimes when you mention coding to teachers they think “not me, nothing to do with me” - “I don’t know how to do it” rather than, I suppose, testing the waters which is at the heart of it.

Usability of CD/LCNC and course outcomes

Perceived use and potential further use of CD/LCNC

From the survey data, five of the eight teachers had used a form of LCNC previously such as MIT App Inventor, Thunkable, or Google Sites. Seven of the eight teachers indicated their ability to synthesize fundamental knowledge and skills of Citizen Development had increased post-training. One teacher, Teacher2, found the course was “very much related to the corporate world” and it would need to “be focused on how it would apply to a student’s/teacher’s life.” Additionally, Teacher2 commented the course was “very business oriented and if you were into that—good.”

Although six teachers found LCNC moderately easy to understand and all teachers were agreeable to learning more about LCNC, presently only six of the eight would like to introduce it into their classroom. All teachers expressed an interest in enrolling in Citizen Development courses in the future. Five stated that they would be interested and three stated that they might be in response to the survey item.

Potential level of challenge with CD/LCNC

Fifty per cent of the teachers (N = 4) that completed the training event found the course very easy and these were all CS teachers. Among the surveyed teachers, four indicated that they perceived the potential implementation of Citizen Development as slightly challenging, while three expressed a moderate level of challenge, and one teacher, Teacher2, considered it very challenging due to the course being “heavy in theory.” However, this teacher remained open to learning more about LCNC. Although the eight teachers considered Citizen Development challenging to implement and half of the teachers (N = 4) believed they would need technical support to introduce Citizen Development into the classroom, all teachers agreed they developed a deeper insight into, awareness, and understanding of Citizen Development. They enhanced their understanding of the benefits of LCNC and found that their appreciation of theory applied to practice was aided. Teacher4 liked what the training event afforded:

I liked your course because what you’re kind of doing - you’re giving teachers an opportunity to build digital products or something they would use without that technical side of things- taking out all that coding and making it more accessible in that sense.

Learning outcomes—incorporating into the classroom

In interviews, teachers were asked if LCNC could facilitate a learning outcome led curriculum. Learning outcomes can be defined as “statements in curriculum specifications to describe the knowledge, understanding, skills and values students should be able to demonstrate after a period of learning” (National Council for Curriculum and Assessment and [NCCA], Citation2019, p. 5). A learning outcome based and “spiral curriculum is novel within the Irish education system and specification design” (Scanlon & Connolly, Citation2021, p. 3). In short, learning outcomes provide “potentially measurable outputs from the process of education” (Priestley, Citation2016, p. 8). According to the European Center for the Development of Vocational Training [CEDEFOP], Citation2009), there should be an emphasis, when framing outcomes, “on defining learning outcomes to shape the learner’s experience, rather than giving primacy to the content of the subjects that make up the curriculum” (p. 10). LCNC has the potential to shape learner’s experience and facilitate learning outcomes. However, LCNC incorporation in the classroom may encounter challenges.

According to Teacher1 student motivation is a challenge and unless a student wants to, or has an interest in, achieving a specific learning outcome, it could be difficult for them to follow through from a potential concept to launch in a LCNC application. In Teacher1’s experience, some students have a good work ethic and an interest in developing something of a good standard. However, others may have excellent research done but do not put the time into the coding of it. Teacher1 believes the students should be informed what a successful process looks like from concept to launch, which includes planning, research, reiterating and improving designs. This approach may ensure that students follow through, maintain a strong work ethic, and have the necessary interest to achieve learning outcomes at the highest standard. Certainly, digital/information literacy is important to implement alongside the coding of LCNC applications. Teacher1 expressed how young people need guidance on copyright and plagiarism, they “actually don’t realize that you can’t just copy and paste.” Additionally, Teacher1 emphasizes the importance of English writing and the use of syntax in the coding process:

I think your syntax and your attention to detail with the different types of brackets, colon, semicolon, quotes. I think that’s far more of an issue with someone in code and say not being able to debug their code properly or test it - like they can’t find it because they just don’t recognize the differences.

That was the main one that stood out for me - that I was thinking okay, instead of someone doing their PowerPoint presentation, we could actually do an app instead.

According to Teacher3 in their interview, LCNC could be a useful tool in the classroom for students to analyze and present their data: “I think those things can be very important, especially in Business, you’re not telling them what to do, you’re not transmitting information, you’re just like letting them at the tool, and see what comes about it.” LCNC, for Teacher3 is a “good way to get kids involved with some form of being computer literate…it’s just a bit more unique”. Additionally, according to Teacher3, incorporating LCNC into a Business Studies class could enhance business acumen and skills while fostering an early interest in the field. Teacher3 believes that if students had access to a set of resources that allowed them to “reach the entire world” and encouraged them to think globally, it would benefit their learning experience. A key challenge for Teacher3 is to ensure all students can effectively explore LCNC without any barriers, as barriers may impact on students’ willingness to further use LCNC applications.

LCNC also has the potential to meet learning outcomes in the science classroom. In the Science Junior Cycle curriculum, a CBA called “Extended experimental investigation” tasks students with designing and conducting their own experiments (NCCA, Citation2015b). While Teacher4 acknowledges the potential concerns surrounding accessing mobile phones in school, referring to it as a “grey issue,” they favor the use and development of mobile apps in school. They proposed using LCNC as a platform where students can log their experiments, create videos, and store them. This approach is like Teacher4’s teaching practice during the pandemic when students conducted and recorded experiments at home, enabling this teacher to assess the level of learning outcomes attained online. However, for LCNC to be effective, Teacher4 states it would have to be something unique and integrate with other technological and pedagogical aspects for example, Google Classroom. The teacher highlighted the difficulty of overseeing and assessing experiments in a classroom setting with a potentially large number of students.

Challenges and recommendations

The many challenges associated with any potential implementation of LCNC into secondary schools are outlined in . In this study, both first-order and second-order barriers were identified by the teachers, with second-order barriers being more prevalent.

Table 6. Challenges and recommendations.

Teacher’s beliefs and attitudes toward technology can be a major barrier in using technology (Ertmer et al., Citation2012; Hew & Brush, Citation2007). Teacher mindsets emerged as one of the key challenges identified in this study. Teacher4 believes that teachers often demonstrate a mindset of thinking they cannot incorporate coding due to a perceived fear of technology. If teachers are happy enough with what they have being doing for years, they may not have a desire for change. All teachers commented on some existing attitudes/beliefs in the teaching profession as in “this is the way we’ve always done it. So, this is it” (Teacher3). Teacher1 strongly believes mindset is a teacher’s biggest challenge.

Yet with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, and subsequent school closures, teachers adapted quickly to online teaching, effectively learning and integrating both new and existing technologies. Microsoft teams, Google Meets, Zoom, amongst other platforms were all were integrated into online teaching. According to Winter et al. (Citation2021) the potential of technology use in education became evident during the pandemic; teachers increased their confidence and rate of engagement with technology during this time. In Teacher4’s experience the pandemic broke down barriers for teachers in adopting and integrating technology. As Selwyn (Citation2015, Citation2019) stated, everyone should have a grasp of computing in this era of digital education and teachers have shown their readiness and proficiency in using technologies. They have successfully adapted to pandemic teaching practices in recent years. Their willingness to learn more about technology and enhance their digital skills was evident in the interviews and survey data. Three of the teachers interviewed expressed interest in progressing with the use of technology. These three teachers stated how, “it’s not a huge step to the next step” (Teacher1), where teachers “creat[e] their own type of app” (Teacher4) and “before everything’s forgotten again” (Teacher3).

Another challenge that emerged in the study was the perception amongst some teachers that LCNC appeared quite technical. According to three of the teachers, the use of jargon and terminology posed a challenge, leading to confusion, particularly for those who lacked interest in LCNC. Teacher3 in their interview stated those without interest “won’t have a hope.” Some teachers may not be aware of technological terms, which may add to their struggles with technology. Therefore, it is crucial to be mindful of language and technical terms. By providing and demonstrating LCNC subject-specific examples and avoiding the use of confusing terminology, the burden on teachers can be alleviated. This approach will enhance teachers’ competence and confidence in using new technologies including LCNC.

Teaching is a very time-poor profession. Hew and Brush (Citation2007) noted the hours needed to preview web sites, locate resources, plan and prepare lessons, with teachers often paying the price with ‘burn out’. Teacher2 expressed the view in their interview that teachers are “just coping at the moment.” All teachers interviewed in this study have little time to play around with technology, or as Teacher2 states, have “time to do any fancy stuff.” For Teacher1, with curriculum and examination constraints it is difficult to “get[ting] that dedicated time.”

Supports for teachers and students

Lim and Khine (Citation2006) emphasized the importance of schools implementing technical, pedagogical, and administrative support for teachers to enable effective integration of technology into their teaching roles. To overcome barriers and challenges, it is crucial to provide support for teachers in integrating LCNC into their classrooms. Teacher1 emphasized, in their interview, that without adequate support, and unless LCNC is made “easy for them it doesn’t always happen.”

Increasing teachers’ knowledge and skills: changing beliefs and attitudes

As stated earlier by Ertmer (Citation1999, Citation2012), increasing teachers’ knowledge and skills will potentially change their beliefs and attitudes toward technology use. To facilitate the development of teachers’ knowledge and skills, teachers suggested potential supports, such as aligning with existing Junior Cycle training days or developing short courses for Junior Cycle on Citizen Development, similar to coding and digital media literacy courses on offer by the JCT (Junior Cycle for Teachers). An essential support would be the presence of a trained expert on Citizen Development who can provide training to teachers. It is crucial to create a collaborative environment where teachers can interact with and learn from each other, thereby fostering a valuable learning experience.

Ertmer et al. (Citation2012) have stated the importance of professional development for supporting changes in teachers’ beliefs and attitudes. During the pandemic, Teacher1 took the opportunity to upskill herself, leading to a change in the way she conducted CBAs and the integration of new technologies in the classroom. For Teacher1, effective support entails continuous professional development (CPD), staying aware of new technologies, having access to them, and having opportunities for further learning and exploration. According to Teacher1, CS teachers in Irish secondary schools feel very supported as they have an excellent existing relationship with the teacher association CESI (Computer Education Society of Ireland) and the Department of Education Professional Development Service for Teachers unit. Despite the challenges teachers encounter in finding dedicated time for upskilling, Teacher1 highlighted the shared experience of everyone trying to navigate and discover the most effective teaching approaches, recognizing the importance of “get[ting] the pedagogical knowledge ourselves.”

Access to subject resources/time and technical supports

As mentioned earlier, teachers’ schools in this study have existing access to software for example, Microsoft Power Apps, a LCNC Microsoft application. Teachers have proposed various potential supports for the use and integration of LCNC into their teaching practices. These include demonstrations, tutorials, video tutorials, an FAQ support service for addressing questions and providing assistance, as well as a repository of subject-specific resources that can be applied back within one’s own school. Teachers have expressed that if supports are too generalized, it can be challenging to apply them to teachers’ own specific subjects, which in turn reduces teacher’s interest in using those resources.

Teachers need specific concrete ideas and tailored examples (Snoeyink & Ertmer, Citation2001). It is crucial to provide teachers with examples showing how LCNC can benefit teachers and their teaching subjects as well as demonstrating the step-by-step process of digital transformation as a series of building blocks. As Dobrigkeit et al. (Citation2020) point out, clear and specific guidelines are essential for every stage of application development, including concept, design, development, and launch. Therefore, it is crucial to provide teachers with user-friendly, straightforward guidelines, as well as providing relatable examples that encourage them to explore LCNC further.

Given the time barrier, schools should allocate ample time for teachers to engage in professional and curricular activities for technology integration. According to Ertmer (Citation1999), it is important teachers gain technical skills and effective instructional practices that incorporate meaningful technology use. Snoeyink and Ertmer’s (Citation2001) study emphasize the significance of having a clear purpose for technology use in the classroom to overcome the time barrier. Support for teachers is vital, particularly in integrating potential LCNC integration, as it can free up some valuable time and reduce their class loads (Snoeyink & Ermter, 2001). Teacher3, in their interview, emphasized the potential value of LCNC to teachers: “that would be one thing I think - actually getting across this [LCNC] will save you time, and energy and frustration.”

Quality supports, such as demonstrations and in-person events, play a crucial role in helping teachers see the value and relevance of new initiatives like LCNC for themselves and their students. As Snoeyink and Ertmer (Citation2001) suggest, teachers may need to undertake projects themselves to effectively apply these ideas to their situations. It is important for teachers to experience the implementation of LCNC in both the classroom and administration and have access to real-world examples. This in turn, as Teacher4 stated, “will boost their confidence and break down barriers.” Such supports are essential in alleviating the burden on teachers. Supports can overcome mindsets, complacency, fear of technology/failure/change, and time constraints. Supports help boost confidence, develop competencies, facilitate changes in beliefs and attitudes, and break down barriers.

Student support

Support should be provided not only to teachers but also to students. As Hsu et al. (Citation2019) emphasized, young people need to develop computational thinking and coding skills, to actively participate in future digital economies. Contrary to the assumption that young people are, as Teacher4 states “tech savvy,” in Teacher4’s experience their students often lack proficiency in digital skills, including the use of platforms like MS 365 Office, Google Docs/Slides and so forth. Teacher4 strongly believes students require assistance in using these platforms effectively. Additionally, maintaining student motivation is a challenge in teaching today. In any possible integration of LCNC applications it is important to address teachers’ pedagogical concerns, ensuring student engagement, enjoyable learning experiences, and the cultivation of a strong work ethic.

The importance of developing a clear vision for integrating meaningful technology use has been stressed (Chen et al., Citation2011; Ertmer, Citation1999; Hew & Brush, Citation2007; Zuiker & Ang, Citation2011). Many schools have a digital strategy in place although in this study when asked in the survey about same, three of the eight teachers reported no presence of a digital strategy in their school, two were unsure, and three teachers were involved in their school’s strategy. As we emerge from the global pandemic, it is an opportune time to sustain the momentum of increased technology usage. An effective and quality CD/LCNC program can help teachers and schools in their digital strategies going forward. A program that nurtures a clear vision for teachers can provide opportunities to observe models, engage in reflection, participate in peer discussions, and collaborate with other teachers to experiment and explore new approaches for integrating classroom technology.

Conclusion

This research provides an insight into teachers’ attitudes and beliefs toward technology, their existing use (or not) of technology in their teaching roles, and their perceptions of the potential value and use of CD in the classroom. In future research, it would be beneficial to involve a greater number of teachers in exploring the potential implementation and impact of integrating CD/LCNC in the classroom. Increasing the number of teachers involved in a similar type of research project, will give better insights and greater clarity into teachers’ technological confidence, competencies, existing knowledge and skills, as well as their attitudes and beliefs. While this study focused on the perspectives of teachers, it is important to consider the voices of students when it comes to successfully integrating LCNC into secondary schools. The success of CD/LCNC in the school ecosystem relies on ensuring student agency in the development of any program.

Teachers hold valuable digital learning skills and are open to learning more. Online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic has given teachers opportunities to enhance their digital teaching skills. With schools having resumed face-to-face teaching, now may be the opportune moment to take the next step in integrating technology despite the numerous barriers and challenges that exist. In any implementation of CD, quality supports are vital in order for teachers to overcome challenges, facilitate knowledge and skills, and change attitudes and beliefs. It is crucial to frame CD/LCNC programs in a way that resonates with teachers and their subjects. This approach enables teachers to witness first-hand how LCNC has the potential to save them time, energy and frustration. The availability of a repository of resources and subject-specific examples that teachers can access will be vital for the success of LCNC in schools. Equally, arranging in-person training events and peer group sessions will ensure the active involvement of teachers and facilitate their growth in competence and confidence. This will enable them to share the benefits of LCNC with each other and their students. Given the diverse school environments and varying levels of interest in the use of technology, it is important to continue to reach out to management, teacher associations, ITE programs, to promote the adoption of LCNC into secondary schools.

To ensure that all interested teachers are aware of the potential of new technologies for their classrooms, it is important to continue to target teachers through teacher associations for example, CESI, BSTAI. The findings indicated the high level of self-belief among teachers when it comes to solving problems using technology in their own classrooms. Most teachers believe they can independently develop effective processes and solutions using LCNC, although they also recognize the associated challenges. Teachers’ confidence in their own abilities to incorporate LCNC into their teaching increased after our training event. When teachers feel confident in using technologies, it can lead to a reduction in fear toward technology and technological change.

CD/LCNC is not a panacea to the changes and challenges within our education system, but it does provide a solution to some of the pressures teachers face. Nevertheless, for any CD/LCNC program to be of value to teachers it will need to not only address their pedagogical needs but avoid complicated technical features and help make their teaching-loads relatable and easier.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all who participated in, and supported this research, with special thanks to the teachers for sharing their valuable insights. Special thanks also to Lero, the Science Foundation Ireland (SFI) Centre for Software Research and the University of Galway Citizen Development Lab. Finally, the authors wish to acknowledge the project support and funding from Microsoft and PMI which made this research possible.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Al-Maroof, R. S., Salloum, S. A., Hassanien, A. E., & Shaalan, K. (2023). Fear from COVID-19 and technology adoption: The impact of Google Meet during Coronavirus pandemic. Interactive Learning Environments, 31(3), 1293–1308. doi:10.1080/10494820.2020.1830121

- Beranic, T., Rek, P., & Hericko, M. (2020). Adoption and usability of low-code/no-code development tools. In Central European Conference on Information and Intelligent Systems (pp. 97–103). Varaždin, Croatia: Faculty of Organization and Informatics.

- Blau, I., Shamir-Inbal, T., & Avdiel, O. (2020). How does the pedagogical design of a technology-enhanced collaborative academic course promote digital literacies, self-regulation, and perceived learning of students? The Internet and Higher Education, 45, 100722. doi:10.1016/j.iheduc.2019.100722

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. SAGE.

- Brennan, K., & Resnick, M. (2012, April 13–17). New frameworks for studying and assessing the development of computational thinking. In Proceedings of the 2012 Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Vancouver, BC, Canada (pp. 1–25). AERA. http://scratched.gse.harvard.edu/ct/files/AERA2012.pdf

- British Educational Research Association (BERA). (2018). Ethical guidelines for educational research (4th ed.). BERA. https://www.bera.ac.uk/publication/ethical-guidelines-for-educational-research-2018

- Bryman, A. (2012). Social research methods (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Carroll, N., & Conboy, K. (2020). Normalising the “new normal”: Changing tech-driven work practices under pandemic time pressure. International Journal of Information Management, 55, 102186. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102186

- Carroll, N., Móráin L. Ó., Garrett D., & Jamnadass, A. (2021). The importance of citizen development for digital transformation. Cutter Business Technology Journal, 34(3), 5–9. https://www.cutter.com/article/importance-citizen-development-digital-transformation

- Carroll, N., & Maher, M. (2023). How shell fueled digital transformation by establishing DIY software development. MIS Quarterly Executive, 22(2), 99–127. https://aisel.aisnet.org/misqe/vol22/iss2/3

- Chai, C. S., & Lim, C. P. (2011). The Internet and teacher education: Traversing between the digitized world and schools. The Internet and Higher Education, 14(1), 3–9. doi:10.1016/j.iheduc.2010.04.003

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. SAGE.

- Chen, C. H., Liao, C. H., Chen, Y. C., & Lee, C. F. (2011). The integration of synchronous communication technology into service learning for pre-service teachers’ online tutoring of middle school students. The Internet and Higher Education, 14(1), 27–33. doi:10.1016/j.iheduc.2010.02.003

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2011). Research methods in education (7th ed.). Routledge.

- Connolly, C., Byrne, J. R., & Oldham, E. (2022). The trajectory of computer science education policy in Ireland: A document analysis narrative. European Journal of Education, 57(3), 512–529. doi:10.1111/ejed.12507

- Connolly, C., & Kirwan, C. (2023). Capacity for, access to, and participation in computer science education in Ireland. University of Galway. doi:10.13025/bccm-2c38

- Creswell, J. W., & Clark, V. L. P. (2017). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). SAGE.

- Denning, P. J., Tedre, M., & Yongpradit, P. (2017). Misconceptions about computer science. Communications of the ACM, 60(3), 31–33. doi:10.1145/3041047

- Department of Education and Skills (2016, November). STEM Education in the Irish school system. https://www.gov.ie/en/policy-information/4d40d5-stem-education-policy/#report-stem-education-in-the-irish-school-system

- Deuze, M. (2006). Participation, remediation, bricolage: Considering principal components of a digital culture. The Information Society, 22(2), 63–75. doi:10.1080/01972240600567170

- Dobrigkeit, F., de Paula, D., & Carroll, N. (2020). InnoDev workshop: A one day introduction to combining design thinking, lean startup and agile software development. In 2020 IEEE 32nd Conference on Software Engineering Education and Training (CSEE&T) (pp. 1–10). IEEE. doi:10.1109/CSEET49119.2020.9206184

- Ertmer, P. A. (1999). Addressing first-and second-order barriers to change: Strategies for technology integration. Educational Technology Research and Development, 47(4), 47–61. doi:10.1007/BF02299597

- Ertmer, P., Ottenbreit-Leftwich, A. T., Sadik, O., Sendurur, E., & Sendurur, P. (2012). Teacher beliefs and technology integration practices: A critical relationship. Computers & Education, 59(2), 423–435. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2012.02.001

- Ertmer, P. A., Ottenbreit-Leftwich, A. T., & Tondeur, J. (2015). Teachers’ beliefs and uses of technology to support 21st-century teaching and learning. In H. Fives & M. G. Gill (Eds.), International handbook of research on teacher beliefs (pp. 403–418). Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203108437

- European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training (CEDEFOP) (2009). The shift to learning outcomes: Policies and practices in Europe. Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/publications/3054#group-details https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/publications/3054

- Francom, G. M. (2016). Barriers to technology use in large and small school districts. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 15, 577–591. doi:10.28945/3596

- Galvis, H. A. (2012). Understanding beliefs, teachers’ beliefs and their impact on the use of computer technology. Profile Issues in Teachers Professional Development, 14(2), 95–112. http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/prf/v14n2/v14n2a07.pdf

- Goodfellow, R. (2011). Literacy, literacies, and the digital in higher education. Teaching in Higher Education, 16(1), 131–144. doi:10.1080/13562517.2011.544125

- Harvard Catalyst (n.d.). Mixed methods research. Community Engagement Program. https://catalyst.harvard.edu/community-engagement/mmr/

- Hemerling, J., Kilmann, J., Danoesastro, M., Stutts, L., & Ahern, C. (2018). It’s not a digital transformation without a digital culture. Boston Consulting Group. https://www.bcg.com/publications/2018/not-digital-transformation-without-digital-culture

- Hesse-Biber, S., & Burke Johnson, R. (Eds.). (2015). The Oxford handbook of multimethod and mixed methods research inquiry. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199933624.001.0001

- Hew, K. F., & Brush, T. (2007). Integrating technology into K-12 teaching and learning: Current knowledge gaps and recommendations for future research. Educational Technology Research and Development, 55(3), 223–252. doi:10.1007/s11423-006-9022-5

- Hsu, Y.-C., Irie, N. R., & Ching, Y.-H. (2019). Computational Thinking Educational Policy Initiatives (CTEPI) across the globe. TechTrends, 63(3), 260–270. doi:10.1007/s11528-019-00384-4

- Kim, C., Kim, M. K., Lee, C., Spector, J. M., & DeMeester, K. (2013). Teacher beliefs and technology integration. Teaching and Teacher Education, 29, 76–85. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2012.08.005

- Levin, T., & Wadmany, R. (2006). Teachers’ beliefs and practices in technology-based classrooms: A developmental view. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 39(2), 157–181. doi:10.1080/15391523.2006.10782478

- Lim, C. P., & Khine, M. S. (2006). Managing teachers’ barriers to ICT integration in Singapore schools. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 14(1), 97–125.

- National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA) (2015a). Junior cycle business studies. https://curriculumonline.ie/Junior-Cycle/Junior-Cycle-Subjects/Business-Studies/

- National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA) (2015b). Junior cycle science. https://curriculumonline.ie/Junior-Cycle/Junior-Cycle-Subjects/Science/

- National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA) (2019, September). Learning outcomes. https://ncca.ie/media/4107/learning-outcomes-booklet_en.pdf

- O’Neal, L. J., Gibson, P., & Cotten, S. R. (2017). Elementary school teachers’ beliefs about the role of technology in 21st-century teaching and learning. Computers in the Schools, 34(3), 192–206. doi:10.1080/07380569.2017.1347443

- Priestley, M. (2016). A perspective on learning outcomes in curriculum and assessment. https://ncca.ie/media/2015/a-perspective-on-learning-outcomes-in-curriculum-and-assessment.pdfhttps://ncca.ie/media/2015/a-perspective-on-learning-outcomes-in-curriculum-and-assessment.pdf

- Project Management Institute (PMI) (2021). PMI & Tech2025 July 2021 Citizen developer Survey. https://www.projectmanagement.com/presentations/720143/PMI-Tech2025-July-2021-Citizen-Developer-Survey

- Project Management Institute (PMI) (2022). PMI Citizen developer Foundation Course. https://www.pmi.org/shop/p-/elearning/pmi-citizen-developer-foundation-course/el001

- Resnick, M. (2013, May). Learn to code, code to learn. EdSurge. https://www.edsurge.com/news/2013-05-08-learn-to-code-code-to-learn

- Salmon, G. (2019). May the fourth be with you: Creating education 4.0. Journal of Learning for Development, 6(2), 95–115. doi:10.56059/jl4d.v6i2.352

- Scanlon, D., & Connolly, C. (2021). Teacher agency and learner agency in teaching and learning a new school subject, Leaving Certificate Computer Science, in Ireland: Considerations for teacher education. Computers & Education, 174(4), 104291. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2021.104291

- Schrum, L., Burbank, M. D., & Capps, R. (2007). Preparing future teachers for diverse schools in an online learning community: Perceptions and practice. The Internet and Higher Education, 10(3), 204–211. doi:10.1016/j.iheduc.2007.06.002

- Selwyn, N. (2006a). Digital division or digital decision? A study of non-users and low-users of computers. Poetics, 34(4–5), 273–292. doi:10.1016/j.poetic.2006.05.003

- Selwyn, N. (2006b). Exploring the ‘digital disconnect’ between net‐savvy students and their schools. Learning, Media and Technology, 31(1), 5–17. doi:10.1080/17439880500515416

- Selwyn, N. (2015). Data entry: Towards the critical study of digital data and education. Learning, Media and Technology, 40(1), 64–82. doi:10.1080/17439884.2014.921628

- Selwyn, N. (2019). What is digital sociology? John Wiley & Sons.

- Snoeyink, R., & Ertmer, P. A. (2001). Thrust into technology: How veteran teachers respond. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 30(1), 85–111. doi:10.2190/YDL7-XH09-RLJ6-MTP1

- Teaching Council (2022). Céim: Standards for initial teacher education. https://www.teachingcouncil.ie/en/news-events/latest-news/ceim-standards-for-initial-teacher-education.pdf

- Thacker, D., Beradi, V., Kaur, V., & Blundell, G. (2021). Business students as citizen developers: Assessing technological self-conception and readiness. Information Systems Education Journal, 5(19), 15–30. https://isedj.org/2021-19/n5/ISEDJv19n5p15.pdf

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) (2020). Education in a post-COVID-19 world: Nine ideas for public action. International Commission on the Futures of Education. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373717/PDF/373717eng.pdf.multi

- UC Berkeley (n.d). Course evaluations question bank. Berkley Center for Teaching & Learning. https://teaching.berkeley.edu/course-evaluations-question-bank

- University Of Wisconsin–Madison (n.d). Best practices and sample questions for course evaluation surveys. Student Learning Assessment. https://assessment.provost.wisc.edu/best-practices-and-sample-questions-for-course-evaluation-surveys/

- Winter, E., Costello, A., O’Brien, M., & Hickey, G. (2021). Teachers’ use of technology and the impact of Covid-19. Irish Educational Studies, 40(2), 235–246. doi:10.1080/03323315.2021.1916559

- Zuiker, S. J., & Ang, D. (2011). Virtual environments and the ongoing work of becoming a Singapore teacher. The Internet and Higher Education, 14(1), 34–43. doi:10.1016/j.iheduc.2010.05.006