Abstract

This paper explores young people’s development of digital literacy and resilience and discusses how teachers and librarians can play an important role in supporting young people to become digital citizens: informed, active, ethical, safe and responsible members of the online society. The research involved the delivery and evaluation of an interactive educational workshops that included an online cartoon series, accompanied by openly available educational toolkits dealing with topics of online resilience and safety in the online environment. The research involved a total of 239 secondary school pupils, across six schools and within a single local authority in Scotland. Anonymous qualitative and quantitative data were collected from the learning activities, which related to young people’s experiences, coping strategies and emotions in the online environment. The workshops empowered young people to open dialogue about challenging situations they experience in their everyday online connectivity and express their needs for further training. This work presents an innovative constructivist learning approach that can be replicated with young people to explore multiple challenges and opportunities they may encounter when navigating their online environment.

Introduction

The popularity of social media platforms, such as TikTok and Instagram by an increasingly younger demographic (Ofcom, Citation2022a), indicates that there is a growing need to place emphasis on equipping young people earlier with skills that help them to address multiple challenges they may encounter online, such as cyberbullying, misinformation and the misuse of their personal data. The UK Government’s “Online Safety Bill” aims to minimize the risk of online harm, where platforms accessed by children have a duty to protect them from harmful material and activities that threaten their safety (U.K. Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport, Citation2022). However, this is only one side of the coin. There is also a need to empower young people with digital literacy skills to become active and ethical producers and creators of online content, developing a critical understanding of online malpractices versus ethical behaviors (The Scottish Government, Citation2022; Carretero Gomez et al., Citation2017). These skills ensure that people can become active participants “in social, cultural, economic, civic and intellectual life now and in the future” (Future lab, Citation2010, p. 28), having “the key skills necessary for using technology appropriately and responsibly and for engaging in learning through managing information, communicating and collaborating, problem-solving and being creative” (Education Scotland, Citation2015, p. 58). This emphasis on skills for an active, confident, and responsible online participation and engagement requires not only technical and operational skills (e.g., information processing, evaluation, content creation) but also cognitive, social and attitudinal skills development (e.g., communication, problem solving, collaboration and life-long learning) (American Library Association, Citation2011; European Commission, Citation2019).

A recent strategy, developed by the Scottish Government, highlights “growing as an ethical digital nation and developing trust in the way we use data and apply digital technology” as a “collective responsibility” (The Scottish Government, Citation2021). The “Objects of Trust” framework acknowledges the responsibility of institutions, including schools to ensure online safety, highlighting the importance of becoming ethical digital citizens (The Scottish Government, Citation2022). Education plays an important role in young people growing up as responsible online citizens who respect the online rights, the safety and the wellbeing of others (e.g., recognizing the wrongs of online bullying behavior, respecting rights in the online environment, handling online data with care).

The Scottish Government has set out its vision to “Ensure that digital technology is a central consideration in all areas of curriculum and assessment delivery” (The Scottish Government, Citation2016, p. 3). The development of digital literacy in the “Curriculum or Excellence” is addressed in the “Technologies” subject, where young people develop skills using different digital products and services, learn to search, process and manage information responsibly, and learn about cyber resilience and internet safety, evaluating “the implications for individuals and societies of the ethical issues arising from technological developments” (Education Scotland, Citation2016, p. 16).

The National Framework for Digital Literacies in Initial Teacher Education in Scotland also addresses digital safety and resilience emphasizing the importance of “engaging with young people, parents and guardians about how to promote positive online behaviour” (Scottish Council of Deans of Education, Citation2020), recognizing that, although engaging online and utilizing digital tools help young people to develop digital skills, networking and creativity, the digital world lacks “adult intervention” (p. 9), which further highlights the importance of developing strategies and resources in education programmes (Scottish Council of Deans of Education, Citation2020, p. 11).

The above government initiatives, strategies and frameworks identify a need to tackle the different facets and dimensions of digital literacy, together with the challenges and opportunities they present, stressing the need to develop “technical and operational”, “information navigation and processing”, “communication and interaction” and “content creation and production” skills (Helsper et al., Citation2020), together with a need to develop them from an early age. Current definitions of digital literacy similarly identify an array of multiple digital skills and competencies as well as contesting definitions and research directions (Ilomäki et al., Citation2011; Spante et al., Citation2018; Tinmaz et al., Citation2022). However, there is still a fundamental lack of empirical research focusing directly on younger learners’ perspectives and experiences and particularly within the context of primary and secondary education to explore both the challenges and the opportunities they encounter within a fast-accelerating online environment (Godaert et al., Citation2022).

Background and literature review

Existing research with children and young people highlights challenges with information evaluation and the creation of digital content (Aesaert & van Braak, Citation2018), as well as with online safety (Desimpelaere et al., Citation2020; Shin & Kang, Citation2016), offering some preliminary evidence of the need to explore gaps across the spectrum of digital skills development. In addition, given the complexity of digital literacy as an ‘umbrella term’ encompassing multiple directions and variables, previous research has identified fewer opportunities for cross-comparison studies, with a growing need to understand digital literacy more holistically and by means of repeated and mixed methods studies, beyond small scale qualitative investigations that are predominant in this area (Tinmaz et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, there is need for more critical conversations around exploring the perspectives, feelings, attitudes, and behavior of young people, opening creative dialogue around issues of online connectivity and safety, through creative and interactive educational activities that relate to their own everyday life experiences (Martzoukou, Citation2022a).

Most research in this area is concerned with the dangers of online connectivity rather with exploring young people’s existing experiences and mindsets. Previous research, for example, has found that there are diverse challenges created in the online everyday life context as children and young people are now using a wide range of social media enabled online tools for messaging, video sharing and online gaming to connect with others, learn and experiment. Despite age restrictions being placed upon social media, they connect online increasingly at a younger age, with recent research estimating that in the U.K. half of ten-year-olds own a smartphone and have their first social media at age 12 or under (Ofcom, Citation2019), while this demographic is now even younger, with children aged as young as 8 having an online profile on at least one of the large online social media platforms. Up to half of children 8–12 have set up their own profile themselves without the help of their parents while a third of children include an adult user age after signing up with a false date of birth (Ofcom, Citation2022b). Research in Scotland concludes to similar results as “most social media platforms tend to be composed of relatively young demographics”, for example on TikTok users can be as young as 9 years old (The Scottish Government, Citation2022, p. 12).

While young people use social media for positive activities, such as communicating, learning, connecting and socializing with their peers, and being creative, most research attention has been given to the diverse challenges and multiple online harms that they encounter, such as cyber-bullying, misinformation/disinformation and online identity and privacy challenges that can have a negative effect to their health, safety and well-being. Studies also report that young people need to be constantly connected online and feel popular. Earlier research by Ofcom found that 45% of young people surveyed admitted checking their mobile at night, while one in ten 12–15s had ‘gone live’ (Ofcom, Citation2017). The EU Kids Online 2020 project, which surveyed 25,101 children aged 9–16 from 19 European countries, identified a significant increase in screen time children spend online, which had almost doubled in some European countries (Smahel et al., Citation2020). However, there was also a call for shifting the research focus “to a more contextual assessment of the quality and nature of children’s engagement with digital media” (Livingstone, Citation2020).

A more recent systematic review of evidence points to the complexity of the multiple possible directions in digital literacy investigations, but also turns to the positive outcomes of young people’s engagement with the online environment, demonstrating a link to creating online opportunities and information benefits, and inviting educators to offer a richer approach to the teaching of digital literacy, focusing on critical or evaluative aspects and beyond a single emphasis on technical skills, which emerges as a problematic strategy (Livingstone et al., Citation2023). Further evidence suggests that more research is required around exploring young people’s digital skills development and coping behavior for the purposes of designing curricula that can help empower young people to manage online risks (Haddon et al., Citation2020, p. 104).

Overall, current literature demonstrates that as digital literacy skills demands are constantly changing, so does our need to evaluate teaching methods (Talib, Citation2018) and to reflect on critical thinking and the multidisciplinary nature of media and technology literacy (O’Halloran et al., Citation2017), in a way that “goes beyond teaching online safety and seeks to inform and engage pupils” and help them develop into “capable digital citizens…active and informed in their citizenry online—more likely to intervene positively in negative situations online, more likely to consume online information critically…” (Reynolds & Scott, Citation2016, p. 19).

Current educational methods should aim to engage young people to share their experiences and perspectives openly, using innovative and interesting teaching approaches that allow critical thinking and problem solving as part of the learning process. These, could take the form of posing critical questions or addressing problems to be solved, simulating real-life circumstances, and supporting a constructive learning process that allows to explore ideas and open dialogue with the students (Gunstone, Citation1992).

Aims and objectives

This paper reports on the evaluation of an innovative educational cartoon video project that was designed to support creatively young people’s digital literacy and resilience skills development, as the online citizens of tomorrow, prepared to deal with multiple challenges and opportunities navigating their online environments. The objectives of the project were the following:

Objective 1. To explore young people’s feelings of online connectivity.

Objective 2. To deliver and evaluate an innovative interactive teaching approach, utilizing cartoon animation video storytelling for the teaching of online resilience and safety.

Objective 3. To critically explore different coping strategies of young people (both passive and active) and examine their communicative approaches when dealing with online challenges, as well as their needs for further training.

Research questions

What are the main positive (e.g., sociable, valued, creative) and negative (e.g., worried, unpopular, insecure) feelings that young people report around their online connectivity experiences? Why, do they feel in that way?

Do young people enjoy learning in an interactive way? Do they connect to the experiences and feelings of the imaginary character of the story?

What coping and communicative strategies do young people consider as most effective for dealing with online resilience issues in the online environment? Do they favor active or passive strategies? Are they open to speaking to others when experiencing problems? What are their needs for training when it comes to online challenges (e.g., online bullying, privacy and security, online communication)?

Methods

This study was designed following the paradigm of a pragmatic philosophy, which embraces a plurality and allows flexibility in the choice of method and inquiry perspectives, positing that human thoughts are “intrinsically linked to action”; therefore, understanding social phenomena takes place via understanding both experiences and actions (Kaushik & Walsh, Citation2019, p. 3). The research was conducted using an “experience-based, action-oriented framework”, following a mixed method approach (Kaushik & Walsh, Citation2019, p. 9) which involved the collection of qualitative and quantitative concurrent data to explore young people’s experiences of online connectivity, and a practice-based evaluation of an innovative teaching intervention that utilized cartoon video animation to directly engage learners with real-world online challenges. By means of interactive workshops that encouraged critical thinking and dialogue, the study explored preferred online coping strategies of participants, following a constructivist and dialogic approach to teaching and learning, inviting learners to build upon their own preexisting knowledge and share individual experiences with others. Quantitative data helped to answer ‘what’ questions (e.g., coping strategies, demographic data), while qualitative questions addressed the ‘why’ and ‘how’ aspects of the research (e.g., exploring feelings and strategies). This approach allowed both the depth and breadth of research, leading to a more comprehensive understanding of situations, feelings and perspectives (Saunders 2018), related to online connectivity.

Sampling

A total of two hundred and thirty-nine young people in S1 classes (the first year of secondary school in Scotland) engaged directly with the project, which was delivered to six out of seven schools within a single local Scottish authority. The research took place between May and June 2021, following convenience sampling, with the assistance of librarians and teachers at each school, and was delivered as part of the curriculum (e.g., within scheduled classes, such as English, ICT, Personal and Social Education and Drama) in workshops that lasted approximately 45 min each, covering a single school period.

Due to anonymity and confidentiality, the study was limited on the basis of estimating the response rate, as complete lists of school classes with student numbers were not available to access.

Data collection

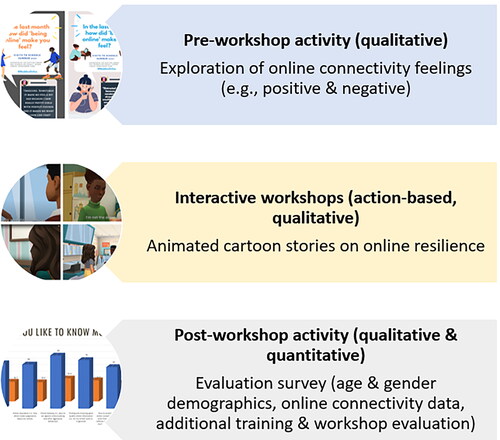

Data collection, as presented in , was organized around interactive workshops, which were delivered to students. The process involved an initial qualitative exploration of feelings around online connectivity, interactive workshops using a series of animated cartoon stories (that addressed the theme of online resilience) and a post workshop evaluation survey, which collected demographic data, participants’ online connectivity data, areas for additional training and workshop evaluation data.

Pre-workshop qualitative survey of feelings

The pre-workshop qualitative exploration of participants’ positive and negative feelings of online connectivity was based on a single open-ended question: “In the last month, how did ‘being online’ make you feel?”. That question carried an added significance, as schools, at the time of the project, were just coming out of a second period of lockdown, due to the global pandemic restrictions; this meant that young people had spent a significant amount of time on online schooling, as well as extended online hours of entertainment/gaming and socializing online with their friends.

Interactive workshops

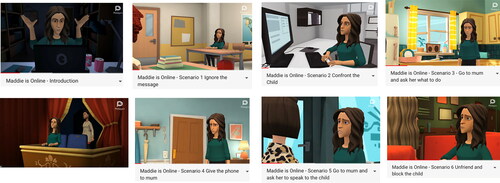

The pre-workshop survey was followed by interactive workshops that employed in the classroom a series of cartoon animated stories, ‘Maddie is Online’, that is based on an ongoing innovative community-led project (aimed at 9–13-year-old children) that uses creative storytelling to produce learning and teaching material, focusing on the development of online information, digital and media literacy skills. The work draws attention to critical issues of online connectivity, in a way that is fun and engaging, linking to children’s and young peoples’ own online experiences within everyday life and the skills they require to navigate safely, effectively and ethically the online environment.

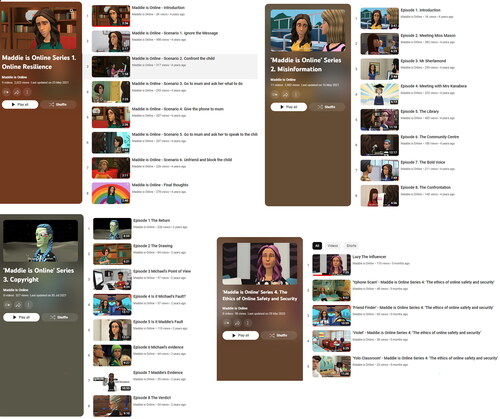

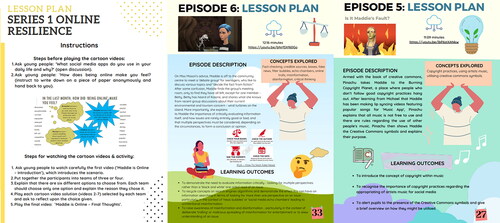

‘Maddie is Online’ includes a total of four animated series (Series 1. Online Resilience, Series 2. Misinformation, Series 3. Copyright, and Series 4. The Ethics of online safety and security). presents Series 1 which formed part of this study.

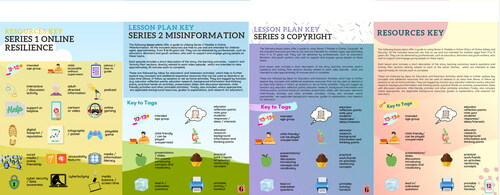

As part of the cartoon project, education resource toolkits were developed that contained useful resources and activities linked to the series themes, extending the relevance and the reach of the cartoon audio-visual material. The toolkits were designed using the online design and publishing tool Canva which allows the creation of different visual design types. Previous research has emphasized the positive impact of rich visual content on improving cognition and retention (Bellato, Citation2013; D’Auriol, Citation2016; Fontaine, Citation2015). A “Key to tags”, presented in , included a number of pictographs that were designed for the categorization of the external material, addressing the intended age group and labeling the selected resources according to material type.

The toolkits also incorporated information about the cartoon video stories, as presented in , and step-by-step structured digital lesson plans with systematic guidance for running the series, the concepts explored and the learning outcomes, as shown in .

Workshop delivery

Series 1 Online Resilience and its toolkit formed the basis of the workshop activity. The story focuses on online resilience and safety and consists of eight short cartoon stories that narrate the experiences of Maddie, a preteen social media active girl who enjoys lip-syncing to music and sharing videos of herself but falls victim to online bullying. The workshop started with an ‘ice-breaking’ introductory video from the series, “Reflections on cyberbullying”, where Maddie discusses both the positive and the negative aspects of being online as well as her own feelings and online experiences, concluding with ideas of how parents can help. This encouraged participants to connect with the character and to relate to the story, reflecting on their own earlier reported feelings of online connectivity.

Following that activity, young people formed teams of 4–5 members, watching the first video and discussing in their team the best solution for the problem of online bullying that the protagonist encounters in the story. A total of six potential solutions/scenarios () were designed on the basis of different coping strategies, discussed by D’Haenens et al. (Citation2013): “fatalistic/passive coping strategies” (such as taking no action, ignoring the situation and expecting the problem to disappear on its own), “communicative coping” (e.g., talking to/seeking advice from someone else) and “proactive coping” (i.e., attempting to address the problem directly by means of deleting a negative message or as in the case of the story unfriending and blocking the bully) (p. 2). The solutions also aimed to replicate strategies that some parents may follow in real life (e.g., taking a child’s phone away for some time). The purpose behind this activity was to engage teams in dialogue and exchange of experiences around dealing with difficult situations experienced online.

Post workshop evaluation

A written questionnaire survey was administered to participants to collect age and gender demographic data together with additional questions that explored young people’s connectivity experiences (e.g., smart mobile phone ownership and preferences for apps and online games). Furthermore, the questionnaire collected participant data on their impressions of the workshop, based on a five-point Likert scale (i.e., ranging from “I did not enjoy it at all” to “I enjoyed it very much”). An additional open-ended question captured the best and the worst aspects of the session. Further data were collected on areas of online connectivity challenges participants required additional knowledge on, which helped to explore follow up training needs in a way that connected to the existing themes of the cartoon animated series (e.g., online image and identity, how to create good online communication and relations with others, online reputation, online bullying, finding and choosing good quality online information, protecting online content, privacy and security).

The workshop approach and its evaluation were previously successfully tested in a pilot study with 30 pupils (Martzoukou, Citation2022a). Following data analysis, the approach was subject to minor revisions which included asking participants to choose a scenario related to the story on an individual rather than team level and offering a written explanation of the rationale for choosing it. This allowed for debate among the team members and critical thinking that balanced the benefits and the limitations of the approach selected.

Data analysis

Qualitative data in this project were analyzed using template analysis for the questions on the feelings of online connectivity (as these involved a priori themes developed with reference to the work by D’Haenens et al. (Citation2013) which became the basis of the coding template (King, Citation1998). Explanations of the chosen scenario/solution were analyzed following second level thematic analysis, using open coding that allowed to identify emerging patterns (themes) within data (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006, p. 79). For example, a proactive coping strategy was rendered as an “easy”, “reasonable” and “safest” solution, while passive coping strategies were linked to the subtheme of “attention avoidance”. Feelings of online connectivity were initially analyzed according to positive and negative responses and, due to the many similarities in responding emotions, similar words were grouped together giving attention to specific words that were particularly recurrent (see for example the word “distracted”). Qualitative workshop evaluation data from the post-workshop questionnaire were analyzed according to positive and negative comments, while quantitative data were analyzed using SPSS quantitative analysis software employing descriptive statistics (e.g., demographics).

Ethical procedure

Written permission was obtained from each school to collect and publish anonymously the data of this study. To ensure the privacy and anonymity of the children who took part, no names or any other personal data were recorded in the questionnaires beyond their gender, and age, as well as some other broader information, such as whether they owned a mobile phone and which online games and social media apps they used. An “Ethics and Contributor Consent Form” was sent to the school explaining the purpose of the research, the background and the value of the project, what the activities would involve and how data would be collected and published. The form also explained that the anonymity of the children would be protected, and that any personal data would be removed. It further addressed the low-level risks associated with participation in the project, ensuring that the activities would not be connected to any forms of assessment or influence the academic performance of the students and that participants could withdraw from the study at any point if they required to do so. The study subscribed to the ethical conduct of research and to the protection, at all times, of the interest, comfort, and safety of participants. All parents were asked to sign the form, via the school, and indicate that they had read the project information and agreed for their children to participate in the study, and for the anonymous publication of any images, video, audio and/or written articles, to be captured and used for research, publication, or for dissemination purposes.

Results

Demographics, mobile ownership and use of apps

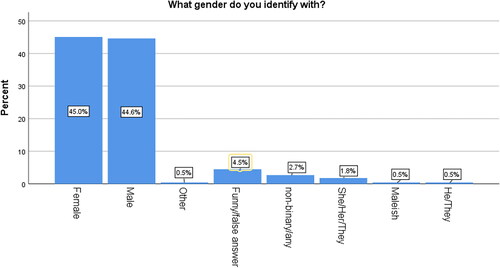

presents the gender demographics of the study, which revealed a balanced distribution of participants in the sample with approximately 45% of young people equally distributed in the female and male categories.

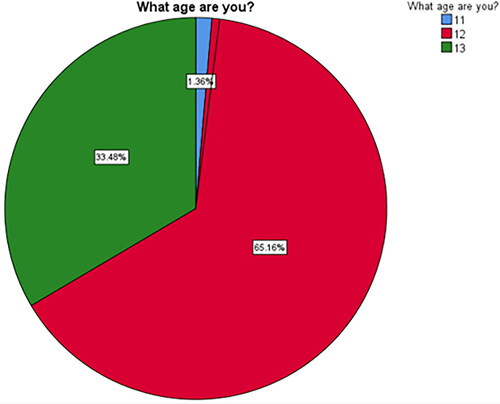

The majority of participants (65%), as shown on , were 12 years old (n = 144), while 33% (n = 74) were 13 years old and just only 1% (n = 3) were 11 years old.

To explore their connectivity experiences, participants were asked if they own a mobile phone and to list their favorite apps and online games (i.e., that they use regularly). The analysis of mobile ownership revealed that only five children did not have their own mobile phone. These results were not surprising as evidence suggests that, in the U.K. 50% of ten-year-olds already own a smart phone and that 49% of 8–11-year-olds use a phone to go online (Ofcom, Citation2019).

The most popular tools young people used were Snapchat (n = 117, 62%), followed by TikTok (n = 113, 60%), YouTube (n = 69, 36%), Instagram (n = 56, 30%) and WhatsApp (n = 49, 26%). There were also a few mentions of Discord (n = 15), Netflix (n = 12), Twitch (n = 7), Google apps (n = 7), Roblox (n = 6), Minecraft (n = 6), Spotify (n = 6), Twitter (n = 6), Facebook (n = 5) and Disney + (n = 5) as well as a few mentions of messaging apps (such as Messages, Messenger, Facetime) and games or games related apps (e.g., Game, Clash of Clans, Clash Royale, Among Us, Call of Duty). The popular use of social media apps, such as Snapchat and TikTok, despite that the minimum age for using them is 13 years old, has also been verified by earlier research (Ofcom Citation2022b). Given that in our sample 65% of participants were 12 years old, the data offered a clear indication that social media use started at an earlier age. Indicatively, 62% (n = 74) of the 12-year-olds in our study used Snapchat and 59% (n = 71) used TikTok. Interestingly, the proportion of 13-year-olds who used these apps was very similar with only 0.5% and 1% difference between the two groups.

Feelings of online connectivity

Young people’s verbalizations included different expressions of positive feelings when connecting online. Most of the children expressed a feeling of being sociable, described as an opportunity that extended connectivity with existing friends as well as making new ones, “go to online classes and clubs”, and be “connected with the world”, emphasizing the sociable character of online interactions: “I can talk to my friends even when I can’t meet up with them due to Covid”, “I feel valued when talking to my amazing friends”. Young people also referred to the multiple affordances of the online environment for connectivity, via different apps (such as Messaging, WhatsApp and Instagram, Snapchat and Facetime): “I made friends online on Snapchat and now I have another couple of friends. I am no longer lonely!”.

In addition, several participants emphasized the value of playing online games with friends and having fun via online social activities: “It’s fun because I can run away from real life”. Playing games even evoked a “cathartic” feeling: “Games are a way for me to vent”. There were multiple positive feelings emanating from activities emphasizing creativity: “If you are on TikTok and you listen to sounds you can make up dances” and “I have an app on my phone which is a drawing app and I like to draw on that”, “I make edits of famous people!”, “…I made my own website”. Other positive feelings included being “relaxed”, “involved”, “interactive”, “excited”, “entertained”, “daring”, “valued”, “smart”, “innovative” and “knowledgeable”, e.g., watching YouTube videos and learning new things they liked online, “inspired to do things”, finding “inspiring content for projects and ideas”, and sharing new tips they learned online about their favorite hobbies. Online connectivity was also described as a lifeline for some of the young people as it offered ways to feel “included” and “connected” during the pandemic: “I could still talk to my friends and play with them on video games at the time that we couldn’t meet outside”, “I get to talk to online friends and school friends as a way to stay in touch during lockdown”, and deal with the pressures of the situation they were experiencing, making them feel “happy”, “keep contact with others and not be so lonely” and allowing themselves to be “distracted from bad thoughts”. As one of the participants characteristically put it: “my phone is my comfort thing”, while another one mentioned: “Seeing other people online feeling a bit stressed or worried made me feel better because I know I’m not the only one feeling that way”.

For other children, online connectivity meant learning about the world and growing up: “I felt like big girl”, “it teaches me about the world”, “I’m able to experience and learn about things that happened more than a decade ago”. Finally, several participants mentioned feeling “popular” because of online posts they had made that were endorsed by many of their online followers, making them feel “proud” of their achievements: “Because on Instagram I posted a video that got 3000 views”, “Because I recently got 1000 followers on TikTok and I never thought that would happen”, “I have posted on Tik Tok and got 1K views and people really like the football content I post”, “On Insta…people tagged me and I’m on way to 2 K followers”. A synopsis of key indicative positive quotes is given in .

Table 1. Positive feelings of ‘being connected online’.

However, several children also expressed negative feelings. These included feelings of insecurity or feeling “left out”, “worried” and “unpopular”. A few young people also felt “uncomfortable” and “insecure” around their social media presence: “A dude on Snapchat asked to see my face so I sent him a picture and he replied with comments that I didn’t want to be called. I have now blocked him so I hope I never talk to him again”, “I can sometimes feel insecure about my social media presence”; while others referred to the “dangers of being online”, demonstrating awareness of the complexity of online presence and its connection to cyber-bullying, when it came to “hurtful videos or comments” and “people being nasty over text”, or even “worried because people that are older could maybe cyberbullying and take it too far by finding my house”. Others felt “sad” and “insecure” by idealized body image depictions: “I saw really pretty girls with perfect figures and it makes me want to look like that” and “When I see other people do certain things or look a certain way it makes me insecure because I would like that as well, to look like them”.

However, the most commonly encountered problem that young people referred to was being “distracted” by constant notifications and “could not focus”:

I spent too much time on my phone and I spent more time on my phone when I should have been doing other stuff.

I am probably supposed to be doing my homework, cleaning my room, helping my sister etc., and I go on my phone and go on tiktok just to watch “1” tik tok but I end up watching like 50 tik toks.

I was doing my work my phone was just sitting right in front of me and then my phone vibrates because I get a notification. Then I’m sitting on my phone for an hour, then I’ve missed my work deadline.

I can’t focus on my work because I spend too much time texting my friends.

Table 2. Negative feelings of ‘being connected online’.

The key feelings that children expressed were subsequently converted into infographics and shared via social media to disseminate the findings externally, as presented in .

Children from the participant schools were also invited to verbalize some of these feelings, adding voice-overs to the data. This resulted in short cartoon videos, as presented in , which gave voice and life to the data.

Cartoon video activity

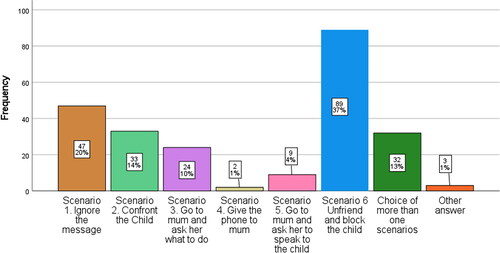

The cartoon video activity involved children in making choices after discussion, by means of collectively choosing a possible scenario/solution for the incident of online bullying the protagonist of the story experienced. demonstrates that the most popular scenario/solution was Scenario 6 “Unfriend and block the child”, with 37% (n = 89) of the participants choosing it, followed by “Ignore the message”, and then “Confront the child”, while 13% (n = 32) of participants chose multiple solutions, usually followed in a specific sequence with the most popular combination being Scenario 6, followed by Scenario 1.

Children’s verbalisations revealed that Scenario 6 “Unfriend and block the child”, a form of “proactive coping” (D’Haenens et al., Citation2013) was preferable for various reasons, including ensuring early intervention so that the incident does not become a recurrent situation, escalates or involves other people. Indicatively, some of the explanations included: “Because I think the other ones would escalate but after you blocked it would be over”, “Stops the problem without getting anyone involved”, “Because it keeps the situation from becoming bad”, “Because it does not go any further”, “…they don’t bother you again”.

Several comments also emphasized the difference between receiving negative comments online from a friend/person you know, as opposed from someone who does not know you or is not your real friend: “Because she has never met her and if she is saying things like this it is the best thing to do”, “Maddie should not worry about the opinion of anyone especially if she doesn’t know her personally”, “Because she doesn’t even know the girl that well and it will stop arguments”.

Other explanations demonstrated that intervention would be an “easy”, “reasonable” and “safest” solution, especially as unfriending and blocking the person who bullied would mean the end of the problem, something that may not be possible if a friendship or connection with the bully existed: “Because you would stop the hate and it’s easy and it stops unwanted drama”, “Because it’s easier and it means they won’t bother you again”, “Because it’s easy and they will never text you again, “Then they can’t say anything mean to her again”. These replies showed understanding of the potential complexity of an online bullying situation: the situation may have been more difficult if it involved a person young people were connected with as a friend.

Interestingly, some of the explanations were also guided by offering emotional support directly to the story character: “It’s just a single person just ignore it because you have lots more friends, one bad comment doesn’t matter”, “Block them because you hardly know them and they can’t see your posts”. In other cases, participants offered advice on broader online behavior strategies around what one should do to avoid finding themselves in that difficult situation: “Don’t add strangers online it could be a bad and they could send hateful stuff”, “Don’t add people you haven’t met”, “…remove all the people from your followers who you don’t directly know”. Other comments reflected on reasons that related to the participants’ own self: “Because I can’t be bothered arguing with someone I don’t even know”, “So that the person won’t bother me again”, providing some evidence of previous personal encounters with online bullying: “I always go with scenario 6. Once you block them they are more or less gonna stop trying”, “I chose scenario 1 because I don’t care what people call me online”.

The next most preferred option, Scenario 1 “Ignore the message”, involved ignoring the situation and taking no action, linked to a passive coping strategy (D’Haenens et al., Citation2013). However, participants’ explanations demonstrated that this choice was a conscious decision that was not connected with avoiding the problem; instead they pointed to tactics that work with ignoring bullying behaviors specifically, ensuring that a reaction which further encourages the bully to continue that behavior is not present: “…A lot of people hate the silence treatment and it’s better just not to care about it”, “Because it will make the child see like it did not affect Maddie and will not be satisfied meaning she will get bored and stop”, “Because if someone is being mean to you try to just ignore it and when it doesn’t bother you they will probably stop trying”, “If you confront it then then the person who commented will keep doing it because you are giving them a reaction so it is better to ignore it”, “Because if you give the comment attention then they will want to do it again because you are sad about it”. It was important that the incident was not given value, importance or more attention than what it deserved: “What’s the point in worrying - Just forget about it”, “Because it doesn’t matter and you shouldn’t give them the time of day”.

Similarly, to Scenario 6, the situation was deemed to be straightforward as it did not involve a repetitive occurrence or a direct friend, with some direct references to personal experiences and ways of coping in similar situations: “It’s 1 negative comment. You’ll get loads of them online you may as well ignore the comment and don’t escalate it any further. Just don’t pay attention to that person”, “I would ignore them because it’s one person you don’t know and if it keeps happening block them”, “Because it’s one comment it doesn’t matter, it happens to everyone”.

Other explanations revealed broader behavioral approaches and the importance of recognizing the level of significance of online risks and developing online resilience: “Because you should not care about what other people think, you should just be happy and keep on posting on a private account”, “Because she shouldn’t listen to hateful comments and she should only listen to the positive things”, “If she doesn’t spend time fixating on it, it won’t matter to her”, “Because you can’t let such a little thing bother her she shouldn’t need other people’s validation. Just ignore it”, “Why should you care…It may seem hurtful at first but you should focus on the positivity not the negativity”.

The next most popular strategy with dealing with the problem of online bullying presented in the story involved Scenario 2 “Confront the child”, a form of proactive coping, which was chosen as a way to ensure this their behavior will not be repetitive, “Because if you do not confront the child then they might do it again” and “to stop this rude and uncalled for behaviour”, while others pointed to the need to teach them a lesson, “make them feel bad” or “to make you feel better”, again pointing to broader behavioral attributes such as “Because you have to learn to stand up for yourself”, “You can’t let others destroy your happiness, it also grows character & resilience. You have got to learn to stand up for yourself!” and “I want to see her stand up for herself”.

Interestingly, others suggested that this solution also had an element of “communicative coping”, exploring the reasons behind the incident and what motivated the bullying behavior: “To find out how the child is”, “Confront the child and talk about why they said it. See what they would say in real life”, “…you can find out why they are commenting that and confront them and tell them to stop”. However, in general a communicative coping strategy (e.g., Scenario 3) was less popular, although the young people who chose that option explained that the experience of an adult would be helpful to dealing with the problem in a “smart” way, “better” and “properly”, and it was important to confine to a person of trust, who were “wiser than her and more experienced” and could “make her feel better”. As they further explained “…the mother might have some experience with this type of stuff and might have a good idea on what to do”, “She would have dealt with similar things before and she could give the best advice”, and “So she can get help from an adult and to tell someone and get it out of her system”.

Workshop evaluation

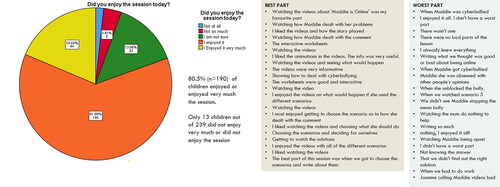

After the end of the workshop, the participants were asked to indicate which part of the workshop they enjoyed most, based on a five-point Likert scale (i.e., ranging from “I did not enjoy it at all” to “I enjoyed it very much”). presents that most of the participants (80.5%) “enjoyed” or “enjoyed very much” the sessions, as they engaged in different scenarios and solutions to decide on the best outcome for Maddie. Participants also indicated that their favorite part of the workshops were the cartoon videos and choosing the best scenario for Maddie: “I liked the videos and how the story played”, “I enjoyed the videos on what would happen if she used the different scenarios”, “I most enjoyed getting to choose the scenario as to how she dealt with the comment”, “Choosing the scenarios and deciding for ourselves”, “…when we got to choose the scenarios and write about them”. Interestingly, several children also expressed that their worst part of the session was “When Maddie was cyberbullied”, “When she unblocked the bully”, when “We didn’t see Maddie stopping the mean bully”, “Watching the mum do nothing to help” and “Jasmine calling Maddie’s videos bad” which demonstrates that young people related to the animated characters and were also able to connect on an emotional level with the moral and the lessons of the story.

Additional areas of interest

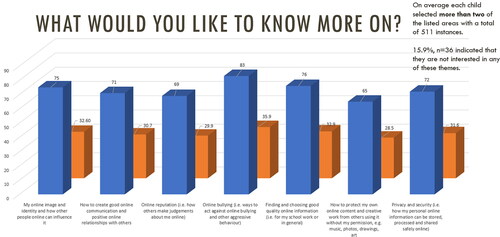

In addition to the evaluation of the workshop session, participants were asked if they would like to have additional similar activities in the future organized in their school and they were given a choice of topics they would like to explore more. As shown in , the participants expressed interest for multiple themes with the most popular being online bullying. On average each child selected more than two of the above listed areas with a total of 511 instances. Only 15.9% (n = 36) indicated that they are not interested in any of these themes.

Sharing online worries

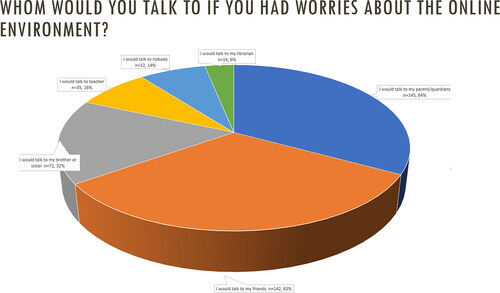

Finally, participants were asked to indicate the people they would normally talk to if they had worries about the online environment. As shown in , most young people selected their parents, guardians and friends as well as their siblings (64%) but teachers (16%) and librarians (6%) were the lowest selected groups, calling in that way for a need to engage more with young people around these issues and protect their online safety and resilience. Alarmingly, there was also a small proportion of children who would not speak to anybody about these issues (14%).

Discussion and implications

Equipping young people with digital literacy

The Scottish Government (Citation2021) has set out a vision for Scotland “as a vibrant, inclusive, open and outward looking digital nation” (p. 18). Emphasis is placed on recognizing not only the opportunities created with the use of digital technologies and connectivity, but also the multiple challenges young people encounter when navigating their online environments with the purpose of finding good quality information and dealing with issues such as misinformation, fake news and the ethical sharing of information. Schools have an important role to play in equipping young people with information and digital literacy skills and are well placed to put forward a new important agenda, which places equal emphasis on digital literacy as that given to literacy and numeracy, with innovative interventions which place these skills at the center of learning and development.

This study tested an innovative constructivist approach to the teaching of digital literacy to probe students’ ideas and engage them in a dialogic learning process, where they shared their feelings around both the opportunities and the challenges of online connectivity and were able to connect with the problem presented to them, and interpret it connecting back to their own experiences, devising their preferred solutions and demonstrating critical thinking and engagement with the issues. The study demonstrated a complexity of affective situations which suggested that the online environment created ample affordances for connectivity, socializing, creativity, learning and growth for young people. However, it also presented several challenges, where educational interventions may be particularly beneficial or necessary. School education strategies should place emphasis on creating advanced awareness and developing skills to address different online behavioral challenges faced by young people. This research demonstrated that the online environment can be a place that is distracting, uncomfortable, addictive, lonely, insecure and competitive and also one, where different behavioral and emotion-coping strategies may be necessary to be developed. For example, young peoples’ verbalisations revealed concerns related to their self-image and popularity, handling their relationships with others online and managing their online identity and connectivity. What was mostly of interest was also the dichotomy of these experiences. Playing games online with others could be experienced as both a fun and competitive experience, while connecting with others online could be both a socializing and an isolating incident, leaving young people feeling left-out and excluded. Learning online could be for some a positive, easy and fun activity, while for others a difficult once to manage and focus. Sharing content online could evoke feelings of being smart, creative and popular or a fear of being bullied, making unsafe contacts and receiving inappropriate information from strangers.

As the online environment becomes even more complex there is a need for education to keep abreast of new opportunities and challenges, offering appropriate and timely educational interventions that allow young people to share their experiences and emotions. It is important to further explore the complex layers of the emotional dimensions of online connectivity and what impact it can have on young people. Recent research, for example, has found that children and young people can be more susceptible to emotional exploitation online via content marketing advertisements (specifically those relating to online gambling) which were found to be almost 4 times more appealing to them when compared to adults, triggering positive emotions (Rossi & Nairn, Citation2021). Other research has found that more than half of 8–11-year-olds already own a mobile phone, while two-thirds of 8–11-year-olds are playing games online and nearly half of them are playing against multiple people or teams (Ofcom, Citation2023), which coincides with the results of our study indicating rich and multiple connectivity using different apps and games and with almost all the participants owing a personal smart phone.

Digital skills development therefore requires educators, and everyone supporting young people, to have ongoing awareness of the developments that take place within the continuum of young people’s online lives, with a focus not only on accessibility and basic digital skills, but also on shaping safe and resilient online behaviors and with an understanding of how these behaviors evolve.

Communication about digital literacy challenges

In the present study, young people did not favor communicative coping strategies and would not speak to their teachers although most available advice around cyberbullying centers on encouraging conversation and expressing concerns openly. At the same time, they suggested diverse and complex strategies to address the problem of cyberbullying the imaginary character of the story encountered, often with multiple steps and solutions. Teachers and school librarians would, therefore, find added value in working together with young people with the aim to increase understanding of their everyday life evolving digital experiences and help to open important and critical dialogue, encouraging the sharing of their experiences with each other in a way that would overall benefit their digital competence skills development. Digital literacy lessons can be incorporated in various subjects and the school library can provide access to readily available interactive educational and supportive resources, by means of creating a positive presence and a supportive culture between home and school.

School teachers and librarians should be trained and be given continuous professional development opportunities on how to handle online sensitive issues that pupils may encounter when they are sharing information online, how to protect themselves and create opportunities for positive and ethical online interactions, to play a pivotal role in developing a positive online digital citizenship culture for children and young people. This encompasses an understanding of the emotional dimensions of online connectivity (e.g., digital likes, connections, challenges) and how they influence mental wellbeing, of ways to safeguard young people’s digital footprints (e.g., what they share, where they share and with whom) and of ways to make them “smart” about the websites they visit, the emails they open and the links they click on - providing a safe, trusted space for children and young people. Pupils’ engagement with the online, interconnected landscape, could start with online positive and creative activities inside and outside school time, where the library can be used as a “second online home” and the school librarian as “somewhere between a parent and a teacher” (The Scottish Government & COSLA, Citation2018, p. 26).

Conclusion and follow-up work

The development of digital literacy is not just as an issue of technical competence, but of a deeper understanding of learning behaviors (Sefton-Green et al., Citation2009), adopting a creative and critical digital pedagogy that gives emphasis on the process over the end product (Mattock, Citation2022). Polizzi and Harrison (Citation2022) propose a model of cyber-wisdom which contains four components: “cyber-wisdom literacy”, “cyber-wisdom reasoning”, “cyber-wisdom self-reflection”, and “cyber-wisdom motivation” arguing, similarly to this study, that different perspectives and emotions need to be acknowledged and understood in addition to existing knowledge and practices students bring with them in the classroom (Nash et al., Citation2021).

As part of this project, ‘Maddie is Online’ was evaluated to be a successful cartoon video educational resource for children 9–12 years. The young people who took part connected with Maddie’s everyday life experiences and feelings of online connectivity and the workshops empowered them to open dialogue about challenging situations they experience in their everyday online connectivity and express their needs for further training. The video cartoon series aimed to stimulate critical thinking and ignite meaningful dialogue learning activities in both the class and the home, engaging young people directly. Lund (Citation2022) has elaborated on the value of storytelling and why it is important for creating a narrative around data visualizations that compels readers and viewers to act upon findings. In addition, the project created openly accessible educational material that were shared in the community of schools, nationally, as well as internationally (BRIDGE Portal, Citation2023; Martzoukou, Citation2022b; Citation2022c).

This research project aligned closely with key strategic aims of the Scottish Library and Information Council. Specifically, Strategic Aim 2. Information, Digital Literacy & Digital Creativity and Strategic Aim 4. Health and Wellbeing (School libraries in Scotland contribute to health literacy, social and mental wellbeing, and provide a safe, trusted space for children and young people to be nurtured) (Scottish Government & COSLA, 2018). Follow up work could utilize these innovative resources to replicate the present study or explore the additional interactive learning activities offered in the series in empirical studies that aim to encourage young people to open dialogue about their own experiences. Teaching and learning strategies should support critical thinking skills in digital literacy and particularly ethical online behavior and attitudes, as the pillars of digital citizenship skills development.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aesaert, K., & van Braak, J. (2018). Information and Communication Competences for Students In J. Voogt, G. Knezek, R. Christensen, & K-W. Lai (Eds.), Second Handbook of Information Technology in Primary and Secondary Education (pp. 255–269). Springer International Publishing AG. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-53803-7

- American Library Association (2011). What is digital literacy? Office of Information Technology Policy (OITP); Digital Literacy Task Force. http://hdl.handle.net/11213/16260

- Bellato, N. (2013). Infographics: A visual link to learning. eLearn, 2013(12), 1. doi:10.1145/2556598.2556269

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. (2006). doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- BRIDGE Portal. (2023). https://bridgeinfoliteracy.eu/

- Carretero Gomez, S., Vuorikari, R., & Punie, Y. (2017). DigComp 2.1: The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens with eight proficiency levels and examples of use. Publications Office of the European Union. doi:10.2760/38842

- D’Auriol, B. (2016). Engineering insightful visualizations. Journal of Visual Languages & Computing, 37, 12–28. doi:10.1016/j.jvlc.2016.10.001

- Desimpelaere, L., Hudders, L., & Van de Sompel, D. (2020). Children’s and parents’ perceptions of online commercial data practices: A qualitative study. Media and Communication, 8(4), 163–174. doi:10.17645/mac.v8i4.3232

- D’Haenens, L., Vandoninck, S., Donoso, V. (2013). How to cope and build online resilience? EU Kinds Online. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/9694255.pdf

- Education Scotland (2016). Education Scotland Curriculum for Excellence. A Statement for Practitioners from HM Chief Inspector of Education. https://education.gov.scot/improvement/Documents/cfestatement.pdf

- Education Scotland (2015). How good is our school? https://education.gov.scot/improvement/Documents/Frameworks_SelfEvaluation/FRWK2_NIHeditHGIOS/FRWK2_HGIOS4.pdf

- European Commission (2019). Key competencies for lifelong learning. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/297a33c8-a1f3-11e9-9d01-01aa75ed71a1/language-en

- Fontaine, L. (2015). Pictographic Storytelling for Social Engagement. International Conference for Design Education Researchers, 51(1), 83–114. doi:10.1080/00087041.2019.1633103

- Future lab (2010). Digital literacy across the curriculum: A Futurelab handbook. https://www.nfer.ac.uk/publications/futl06/futl06.pdf.

- Godaert, E., Aesaert, K., Voogt, J., & van Braak, J. (2022). Assessment of students’ digital competences in primary school: A systematic review. Education and Information Technologies, 27(7), 9953–10011. doi:10.1007/s10639-022-11020-9

- Gunstone, R. F. (1992). Constructivism and metacognition: Theoretical issues and classroom studies In R. Duit, F. Goldberg, & H. Niedderer (Eds.), Research in physics learning: Theoretical issues and empirical studies (pp. 129–140). Institute IPN, University of Kiel.

- Haddon, L., Cino, D., Doyle, M. A., Livingstone, S., Mascheroni, G., & Stoilova, M. (2020). Children’s and Young People’s Digital Skills: A Systematic Evidence Review, pp. 1–152. doi:10.5281/zenodo.4160176

- Helsper, E. J., Schneider, L. S., van Deursen, A. J. A. M., & van Laar, E. (2020). The youth Digital Skills Indicator: Report on the conceptualisation and development of the ySKILLS digital skills measure. KU Leuven, Leuven: YSKILLS. doi:10.5281/zenodo.4608010

- Ilomäki, L., Kantosalo, A., & Lakkala, M. (2011). What is digital competence?. Linked Portal, European Schoolnet (EUN), Brussels, pp. 1–12. http://hdl.handle.net/10138/154423

- Kaushik, V., & Walsh, C. A. (2019). Pragmatism as a Research Paradigm and Its Implications for Social Work Research. Social Sciences, 8(9), 255. doi:10.3390/socsci8090255

- King, N. (1998). Template analysis In G. Symon & C. Cassell (Eds.), Qualitative methods and analysis in organizational research: A practical guide Sage Publications Ltd.

- Livingstone, S., Mascheroni, G., & Stoilova, M. (2023). The outcomes of gaining digital skills for young people’s lives and wellbeing: A systematic evidence review. New Media & Society, 25(5), 1176–1202. doi:10.1177/14614448211043189

- Livingstone, S. (2020). EU Kids Online 2020 finds more risk to children online, but not always more harm. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/parenting4digitalfuture/2020/02/11/eu-kids-online-2020-finds-more-risk-to-children-online-but-not-always-more-harm/

- Lund, B. D. (2022). The Art of (Data) storytelling: Hip Hop innovation and bringing a social justice mindset to data science and visualization. The International Journal of Information, Diversity, & Inclusion (IJIDI), 6(1/2), 31–41. doi:10.33137/ijidi.v6i1.37027

- Martzoukou, K. (2022a). Maddie is online’: An educational video cartoon series on digital literacy and resilience for children. Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning, 15(1), 64–82. doi:10.1108/JRIT-06-2020-0031

- Martzoukou, K. (2022b). Maddie is Online’: A creative learning path to ethics of online safety and security for young people [Paper presentation]. Székelyudvarhelyi Városi Könyvtár (Odorheiu Sequiesc City Library), Transylvania, Romania. The library of the future.

- Martzoukou, K. (2022c). Building a Media, Digital and Information Literate Scotland, Autumn Gathering, ‘Young People and IL – panel discussion’. [Online conference presentation]. Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals. https://www.cilip.org.uk/events/EventDetails.aspx?id=1632106

- Mattock, L. K. (2022). Raspberry Pi and Rubber Ducks: Digital Pedagogy and Computer Anxiety in the LIS Classroom. Journal of Education for Library and Information Science, 63(2), 170–186. doi:10.3138/jelis-2018-0062

- Nash, B., Reyes, M., IV, Williamson, M., & Hedgecock, M. B. (2021). Inquiries into digital funds of knowledge: Envisioning a sociocritical digital reading curriculum. English Leadership Quarterly, 44(2), 2–7. doi:10.58680/elq202131527

- O’Halloran, K. L., Tan, S., & E, M. K. L, & K.L. E, M. (2017). Multimodal analysis for critical thinking. Learning, Media and Technology, 42(2), 147–170. doi:10.1080/17439884.2016.1101003

- Ofcom (2017). Children and Parents: Media Use and Attitudes Report. https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/108182/children-parents-media-use-attitudes-2017.pdf

- Ofcom (2023). Children and parents: Media use and attitudes report 2023. https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0027/255852/childrens-media-use-and-attitudes-report-2023.pdf

- Ofcom (2022a). Children and parents: Media use and attitudes report 2022. https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0024/234609/childrens-media-use-and-attitudes-report-2022.pdf

- Ofcom (2022b). Children’s Online User Ages. Quantitative Research Study. https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0015/245004/children-user-ages-chart-pack.pdf

- Ofcom (2019). Children and parents: Media use and attitudes report 2018. https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0024/134907/children-and-parents-media-use-and-attitudes-2018.pdf

- Polizzi, G., & Harrison, T. (2022). Wisdom in the digital age: A conceptual and practical framework for understanding and cultivating cyber-wisdom. Ethics and Information Technology, 24(1), 16. doi:10.1007/s10676-022-09640-3

- Reynolds, l., & Scott, R. (2016). There is an urgent need for schools to develop digital citizenship in our young people: Digital citizens: Countering extremism online. DEMOS. https://www.demos.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Digital-Citizenship-web.pdf

- Rossi, R., & Nairn, A. (2021). What are the odds? The appeal of gambling adverts to children and young persons on Twitter. University of Bristol. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.31807.84645

- Scottish Council of Deans of Education (2020). The National framework for digital literacies in initial teacher education. University of Glasgow. https://digitalliteracyframework.scot/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/SCDE-National-Framework_B.pdf

- Sefton-Green, J., Nixon, H., & Erstad, O. (2009). Reviewing Approaches and Perspectives on ‘Digital Literacy. Pedagogies: An International Journal, 4(2), 107–125. doi:10.1080/15544800902741556

- Shin, W., & Kang, H. (2016). Adolescents’ privacy concerns and information disclosure online: The role of parents and the Internet. Computers in Human Behavior, 54(9), 114–123. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.07.062

- Smahel, D., Machackova, H., Mascheroni, G., Dedkova, L., Staksrud, E., Ólafsson, K., Livingstone, S., & Hasebrink, U. (2020). EU Kids Online 2020: Survey results from 19 countries. EU Kids Online. doi:10.21953/lse.47fdeqj01of

- Spante, M., Hashemi, S. S., Lundin, M., & Algers, A. (2018). Digital competence and digital literacy in higher education research: Systematic review of concept use. Cogent Education, 5(1), 1519143. doi:10.1080/2331186X.2018.1519143

- Talib, S. (2018). Social media pedagogy: Applying an interdisciplinary approach to teach multimodal critical digital literacy. E-Learning and Digital Media, 15(2), 55–66. doi:10.1177/2042753018756904

- The Scottish Government (2022). Building trust in the digital era: Achieving Scotland’s aspirations as an ethical digital nation. Frameworks and Concepts - Building trust in the digital era: achieving Scotland's aspirations as an ethical digital nation - gov.scot (www.gov.scot)

- The Scottish Government (2021). A changing nation: How Scotland will thrive in a digital world. https://www.gov.scot/publications/a-changing-nation-how-scotland-will-thrive-in-a-digital-world/pages/an-ethical-digital-nation/

- The Scottish Government (2016). Enhancing learning and teaching through the use of digital technology. https://www.gov.scot/publications/enhancing-learning-teaching-through-use-digital-technology/pages/4/

- The Scottish Government & COSLA. (2018). Vibrant libraries, Thriving schools: A National Strategy for School Libraries in Scotland 2018-2023. https://scottishlibraries.org/media/2110/vibrant-libraries-thriving-schools.pdf

- Tinmaz, H., Lee, Y. T., Fanea-Ivanovici, M., & Baber, H. (2022). A systematic review on digital literacy. Smart Learning Environment, 9(21), 1–18. doi:10.1186/s40561-022-00204-y

- U.K. Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport (2022). Online Safety Bill Fact Sheet. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/online-safety-bill-supporting-documents/online-safety-bill-factsheet