?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

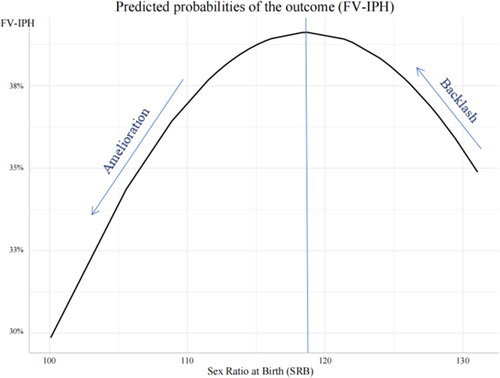

A debate existing in feminist and criminological literature is the plausible macro-level relationship between gender inequality and female-victim intimate partner homicide (FV-IPH). The amelioration hypothesis assumes the reduction of gender-based violence in more gender-egalitarian societies, while the backlash hypothesis anticipates that reducing gender inequality may actually increase males’ violence perpetration against women to maintain their dominance. A third theoretical account hypothesizes a curvilinear relationship that integrates the traditional theses and provides a possible explanation for some inconsistent findings. This study revisited and tested these three macro-level theoretical propositions using detailed incident information on 11,310 Chinese judgment documents of intentional homicides (2017-2019) and multidimensional gender inequality indices across provinces. By disentangling the incident-level effects from the aggregate-level forces, our models enable a more explicit estimation of the relationship between provincial gender inequality and FV-IPH. The results indicated that: 1) backlash processes are more likely to occur with increases in women’s empowerment; 2) the relationship between the degree of egalitarian gender ideology and men’s likelihood of committing FV-IPH conforms to an inverted U. Using an innovative Chinese big-data source and text-mining approach, this study represents a pioneering endeavor, as it furnishes robust empirical evidence to corroborate the curvilinear relationship between cultural gender inequality and FV-IPH in a non-Western context. The implications of our findings underscore the need for tailored policy interventions that take into account the nuanced dimensions of gender inequality, particularly those that are culture-related.

Female-victim intimate partner homicide (FV-IPH)Footnote1 is a persistent, increasingly prevalent global issue that places a significant unfair burden on women. Despite the current downward trend in overall homicide rates, a recent global report revealed a 4% increase in FV-IPH and other family-related homicides since 2014 (UNODC, Citation2019). More than one-third of all females intentionally killed worldwide, approximately 82 every day, are victims of intimate partners, whom they would normally trust and expect to care for them (UNODC, Citation2019). Globally, the gender asymmetry of intimate partner homicide (IPH) victims is significantly higher than that of other forms of violence. Furthermore, mounting evidence depicts the dire consequences of FV-IPH on individuals, families, and societies (e.g. Coker et al., Citation2011; Peterson et al., Citation2018). Given its pervasiveness and seriousness, FV-IPH has emerged as a critical area of criminological research. A slew of studies has expanded homicide research to include FV-IPH.

Feminist criminologists have long debated the links between gender stratification and violence against women, and they generally agree that structural gender inequality is a critical macro-level driving force behind FV-IPH (e.g. Chon & Clifford, Citation2020; Straus, Citation1994). However, theorists have proposed different perspectives on the nature of this insidious connection. The amelioration hypothesis posits that higher levels of gender inequality would severely limit women’s empowerment and create an environment conducive to violence against women (Schwendinger & Schwendinger, Citation1983; Whaley & Messner, Citation2002). With increased opportunities and higher social status, women might have greater autonomy and independence, which helps to protect them from the risk of FV-IPH. However, the improvement in reducing gender inequality is likely to be perceived as a threat to men’s power and authority over women, and as a result, generate a “backlash” or retaliation (Lauritsen & Heimer, Citation2008; Russell, Citation1975). Hence, men with a conventional belief in their patriarchal dominance over women may intend to use force to exercise control over their female counterparts (Anderson, Citation2005). Although both of the aforementioned approaches to understanding FV-IPH are beneficial, they have been criticized for inadequately rationalizing the complex causes and patterns that underpin FV-IPH. A recent vein of gender-based violence research reconciles the traditional propositions that have long been pitted against each other. This viewpoint hypothesizes a dynamic between these “counter-balancing forces”—both processes exist as gender equality ranges from low to high levels; whether the amelioration or backlash process is dominant depends on their relative strength in relation to the level of gender inequality at a given stage (Whaley et al., Citation2013).

Previous empirical studies based on the three perspectives, however, failed to provide a clear and valid evaluation between them. Several theoretical and methodological issues have resulted in less than conclusive results. In three major areas, the current study seeks to improve on the existing literature. First, this study investigates FV-IPH based on the above three macro-level theoretical explanations while at the same time controlling for the incident-level influences. FV-IPH, as a global problem of epidemic proportions, is a multifaceted issue rooted in a dynamic combination of complicated institutional and individual risk factors (Chrisler & Ferguson, Citation2006; Heise & Kotsadam, Citation2015). The proper investigation of structural-level effects on FV-IPH thus needs to examine the distal aggregate-level forces as posited by the three hypotheses, independently of the proximal characteristics of defendants and victims and other incident-related factors (Frye et al., Citation2008). Feminist theorists like Risman (Citation2004) have significantly advanced our understanding by proposing theories that systematically encapsulate gender structures at both micro and macro levels. This comprehensive framework demonstrates how gender operates across multiple levels. It has inspired several international studies that use a multilevel approach to assess the effects of aggregate-level amelioration and backlash forces on intimate partner violence (IPV) against women (e.g. Ivert et al., Citation2020; LeSuer, Citation2020). However, the findings, predominantly based on cross-national self-reported survey data, are inconsistent and have not yet been linked with the non-linear hypothesis or extended to IPH. This study aims to further this research line by employing cluster data to compare three different structural-level perspectives and to incorporate individual heterogeneity in FV-IPH risk.

Second, this study tries to use data-mining techniques to conduct homicide research in China with judgments as an innovative data source. Despite the development of numerous bodies of FV-IPH theories based on statistics from Western countries, empirical tests in Chinese societies are limited due to the lack of detailed crime data. The Supreme People’s Court of China mandated that all courts upload their judgments to the China Judgments Online (CJO) website beginning 2014, for improved monitoring and transparency, enabling scholars to link Chinese crime data to incident-level and aggregate-level factors of criminological interest. We obtained all publicized intentional homicide judgmentsFootnote2 (2017–2019) from the CJO using web-scraping techniques and coding algorithms, which provided a large nationwide sample.

Third, China is a strategic and uniquely suitable research site since its inner heterogeneity and uneven social development offer an ideal opportunity to model the relationship between the degree of gender inequality and gender-based violence using cross-sectional data. Although China has undergone a profound social and economic transformation in recent decades, China’s 31 provincial-level administrative regions are not developing at the same pace (Fan et al., Citation2011). The huge regional disparity persists within China, such that some provinces (e.g. Zhejiang and Tianjin) have reached a developed level in terms of women’s empowerment, while some provinces (e.g. Ningxia and Gansu) lag behind with levels comparable to the least developed countries. Additionally, developing countries were under-represented in existing homicide studies. Indeed, the dominance of Western-based criminology has been identified as a major limitation to the growth of global criminology, especially criminology in the global South (Carrington et al., Citation2016). Hence, this study provides valuable insights by systematically investigating the mainstream FV-IPH theoretical propositions in China.

Overall, this study uses Chinese data sources to bridge the literature on gender inequality and homicide by further considering the direction and functional form of the correlations between structural gender inequality and FV-IPH. It examines traditional amelioration and backlash hypotheses and the third theoretical proposition that incorporates both perspectives. The overarching goal of the analyses is to 1) describe the FV-IPH patterns based on Chinese judgments, taking into account offenders’ characteristics, victim-offender relationships, incident features, etc.; 2) identify the prevalence of FV-IPH across Chinese provinces, and investigate how multidimensional constructs of provincial-level gender inequality influence the likelihood of FV-IPH guided by the three macro-level theses. To get more careful estimations of the structural forces, we control for incident-level risk factors via hierarchical models. By furthering the development of a richer understanding of women’s victimization in China, this study contributes to the interdisciplinary discourse between criminology, feminism and global justice.

Literature Review

FV-IPH, Gender Inequality, and Modernization in China

Violence against women is a significant problem around the world, including in China. According to estimations from a systematic analysis of data obtained from 161 countries and areas, 27% of ever-partnered women reported IPV experiences in their lifetime (Sardinha et al., Citation2022). Considerable prevalence rates are also reported in Asian societies where Confucian paternalistic traditions are deeply rooted (e.g. Park et al., Citation2017). China’s homicide rate in 2016 was 0.6 per 100,000 citizens, ranking 44th in the world; compared to the global average of 5.3, China appears to be relatively safe (UNODC, Citation2019; World Bank, Citation2017). Chinese women, on the other hand, are obligated to bear unjust burdens associated with intimate partner violence. Zhao’s (Citation2020) latest analysis of 1,500 Chinese homicide judgments revealed that 81.9% of IPH perpetrators were males. Male-perpetrated violence against their female partners appeared to be more widespread, with approximately 30% of married women categorized as intimate partner violence victims (All-China Women’s Federation, Citation2019). According to a national report, 31% of male-perpetrated intimate partner violence cases involved intentional homicide, and 34% resulted in serious injury (The Supreme People’s Court of PRC, Citation2015).

China has experienced phenomenal socio-economic transformation and modernization over the last decades. Following the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, the government actively promoted a Marxist ideology that emphasized egalitarian gender roles, and women’s liberation was achieved through mass labor participation and education (Davis & Harrell, Citation1993; Ji & Wu, Citation2018). Gender dynamics in households and traditional jobs have undergone radical changes. The modern generation of women strived for a higher level of education and income, which provided them with more opportunities to balance egalitarian relationships with their family life (Ji & Wu, Citation2018).

In practice, however, such forms of opportunity-related enrichment of gender equality fail to reformulate traditional patriarchal gender norms (Parish & Farrer, Citation2000). For thousands of years, traditional Confucianism contributed to Chinese women’s subordination (Tu et al., Citation1992). The father and the husband are the ultimate disciplinarians in the traditional Confucian family (Slote, Citation1998). The cultural narrative of a “good wife” or “good mother” is deeply embedded in Chinese women’s minds, and women are burdened with bearing prolonged violence to sustain the family’s consolidation. Furthermore, Qian and Li (Citation2020) identified a widening gender gap in gender attitudes. Men, in contrast to women, are predisposed to justify traditional gender ideology, particularly in the private sphere. The liberation of Chinese women may pose a threat to men’s traditional masculinity, leading to increased intimacy tension. Chinese women are constantly subjected to multiple oppressions from the patriarchal system, increasing their chances of FV-IPH victimization.

Despite this fact, there is still a lack of theoretical insight into how structural gender inequality is associated with the risk of FV-IPH. Current FV-IPH research in China is primarily based on media reports or the evaluation of specific cases (e.g. Chan et al., Citation2019; Densley et al., Citation2017). Moreover, a global North-South divide shaped hierarchies in criminological knowledge production and privileged theories based on the empirical specificities of Western societies (Carrington et al., Citation2016). However, application of these theories and outcomes to China may be untenable due to China’s unique social, political, and cultural circumstances. As a result, empirical research in the Chinese context should be conducted extensively in order to educate ourselves on the general overview of FV-IPH and associated gender-specific theoretical interpretations.

Gender Inequality and Gendered Violence: Three Theoretical Perspectives

Feminist scholars have attempted to comprehend violence against women, arguing that gender inequality is a macro-level driving force behind gender-based violence, as social structures create contextual effects that constrain individual behaviors and risks (e.g. LeSuer, Citation2020). Risman (Citation2004, Citation2017) developed the multidimensional gender structure theory, which recognizes the complex relationship between structures and individual actions. This theory emphasizes that gender structures can shape individual orientations, interpersonal interactions, and macro-level societal patterns. It furthered our understanding of gender-based violence, suggesting that macro-level gendered social institutions, gender norms, and stereotypical attitudes towards violence may legitimize intimate partner violence and affect male perpetration of IPV at an individual level (Anderson, Citation2005, Citation2009). The larger social, cultural and gendered processes operating at the contextual level reflect the varying degrees of oppression of women and male dominance; men thus may be likely to use force to exert their dominance over women if they are socially and physically located in societies that are conducive to such behaviors (Heise, Citation1998; Kiss et al., Citation2012).

While scholars widely agree that structural gender inequality is linked to gender-based violence, two points of contention remain: 1) the direction of the relationship—whether gender inequality is associated with higher levels (i.e., an ameliorative effect) or lower levels (i.e., a backlash effect) of gender-based violence; 2) the hypothesized functional form of the nexus - whether the relationship implies a linear or a curvilinear form.

Hypothesis

1. The Amelioration Hypothesis

In early studies of gender-based violence, feminists held that the higher the degree of gender inequality in a social system, the higher the rate of violence against women (e.g. Levinson, Citation1988; Straus, Citation1994). In later expositions, based on the empirical evidence of Western countries, it was theorized that promoting gender equality would result in proportionately lower levels of violence against women, i.e., the amelioration hypothesis (e.g. Whaley & Messner, Citation2002). Gender inequality in patriarchal systems establishes a hierarchical structure where men hold superior status and power, while women are deemed inferior. Within this system, masculinity is shaped by gender inequality and emphasizes male toughness and aggression (Messerschmidt, Citation1996). Hegemonic masculinity, which justifies male dominance, leads men to employ violence as a means of demonstrating and establishing their masculine identity. In societies with pronounced gender inequality, power disparities between men and women are more accentuated, reinforcing conventional notions of masculinity. Consequently, men in such societies tend to be more inclined to employ violence as a means of asserting their strength, power, and masculinity (Lei et al., Citation2014). Additionally, according to liberal feminism’s propositions, a lack of equal opportunities is the root cause of women’s vulnerability (Webb, Citation1997). Women could effectively shield themselves from violence if they are granted equal standings to men, including universal access to power, education, employment, etc. Ideally, increased gender equality should reduce overall female-victim violence, evidencing the process of amelioration.

Previous studies have identified a downward trend in female victimization in the process of achieving gender equality. Lower FV-IPH rates were found in U.S. cities with lower levels of socio-economic status inequality between the sexes (Titterington, Citation2006). Globally, concrete evidence in favor of the amelioration hypothesis can be found in the United Nation’s global homicide report (UNODC, Citation2019). In Finland (representing the lowest level of gender inequality on a global scale), approximately one in every five homicides involves the murder of a woman by intimate partners (Lehti & Kivivuori, Citation2012), whereas the proportion of male-perpetrated FV-IPH in the U.S. was 45% (U.S. gender inequality levels were relatively higher than Finland) (Cooper & Smith, Citation2012).

Based on the preceding discussion, we can hypothesize that in China, gender equality would have an ameliorative effect on the propensity of committing FV-IPH. That is, the achievement of reduced gender inequality, as evidenced by more equal access to economic opportunities/education and improved social status, would lessen the risk of FV-IPH.

Hypothesis

2. The Backlash Hypothesis

Paradoxically, the counter-argument to the amelioration hypothesis, known as the backlash hypothesis, argues that increased opportunities for women may result in increasing levels of their victimization. Initially, Russell (Citation1975) proposed this hypothesis to warn about the potential negative consequences of reducing gender inequality. The backlash of FV-IPH could stem from males’ perceived downfall or lack of control over their female partners as a result of females’ rising status (Vieraitis & Williams, Citation2002). Gender equality and females’ progressive status (e.g. women’s greater visibility in higher education and traditionally male-dominated occupations) may reduce their reliance on males, and threaten their male counterparts’ power as well as dominant conceptions of masculinity. Hence, males are prone to resort to exaggerated forms of masculinity (i.e., violence against women) to preserve the patriarchal system when traditional aspects of masculinity are threatened or when they fail to meet culturally defined standards of gendered success, such as being providers and protectors (Messerschmidt, Citation1996). Men who embrace this hegemonic masculine identity may undergo a transition from feelings of insecurity to a desire for control, basing their success on physical strength and heterosexual conquest (Dworkin et al., Citation2013). The persistence of hegemonic masculinity, with decreasing patriarchal control and gender power imbalances, prompts some men to justify using violence as a means for their patriarchal maintenance in intimate relationships, frequently resorting to violence against women (Fry et al., Citation2019).

Empirical evidence supporting the backlash hypothesis has been discovered in several Western societies (e.g. Chon & Clifford, Citation2020; Gillespie & Reckdenwald, Citation2017). Higher socio-economic status of women (e.g. higher education attainment, female employment, female executives, etc.) has unanticipated retaliatory effects and shows higher levels of male-perpetrated intimate partner violence (Bailey & Peterson, Citation1995; Vieraitis & Williams, Citation2002). When men’s role as breadwinners was threatened by women asserting themselves more and breaking free from traditional feminine roles, men tended to reassert their power and control through physical and psychological abuse (Tang & Oatley, Citation2002). This was especially true when the women’s sociopolitical and economic status rose while their husbands’ gender attitudes remained unchanged.

Based on the above theoretical proposition, advancements in women’s status would result in men’s FV-IPH perpetration to maintain power. We thus hypothesize that, in China, lower gender inequality would be associated with a higher likelihood of FV-IPH.

Hypothesis

3. The Inverted U-shaped relationship Hypothesis

Some scholars have expanded these theoretical statements by investigating the functional form. Vieraitis et al. (Citation2008) predicted that the backlash processes of gender equality would operate until there was a peak point in female homicide victimization, after which such violence would begin to ameliorate. The radical reform toward gender equality may result in a temporary backlash in which men attempt to reclaim their lost power and re-establish the gender-stratified society through the use of force (Brownmiller, Citation1975; Russell, Citation1975). After the initial transition, as both men and women become more comfortable with equality and realize the benefits that equality brings, women’s victimization should decrease (Vieraitis et al., Citation2008).

Therefore, the functional form of the relationship between structural gender inequality and gender-based violence should be curvilinear rather than linear. Specifically, the relative strength of the ameliorative and backlash effects dynamically depends on levels of gender inequality, with the backlash processes likely to predominate as the level of gender inequality decreases from its peak; and the ameliorative effects eventually become more potent after an unspecified period of backlash (Whaley et al., Citation2013). Whaley et al. (Citation2013) went on to explain why such an “inverted U-shaped” relationship exists and how the two traditional feminist hypotheses are compatible. Initially, a high degree of gender inequality is characterized by significant disparities in access to valued resources and opportunities between genders. These structural constraints contribute to the perpetuation of a patriarchal system that positions women as inferior to men, thereby solidifying male authority. Consequently, the necessity for overt acts of violence by men as a means of social control is minimal due to the effectiveness of alternative forms of control, such as male dominance across key institutions and the prevalence of conservative patriarchal ideologies. As gender inequality gradually diminishes from its peak, women gain greater access to labor-force opportunities and engage more extensively in traditionally male-dominated economic and sociopolitical spheres. The emergence of women who challenge traditional gender roles poses a notable threat to their male counterparts (Russell, Citation1975). The intermediate levels of gender inequality thus might pose the greatest danger to women, as this threat often leads to violent retribution against them. Meanwhile, the capacity of women to protect themselves through empowerment remains limited. Over time, as gender egalitarianism becomes more firmly established, conservative gender norms undergo erosion and redefinition. In addition, policies promoting gender equality empower women and foster a more favorable social context for them, thereby enhancing their ability to protect themselves (Inglehart & Norris, Citation2005). Consequently, in the long term, this process of improvement becomes increasingly effective.

While the majority of studies accepted the linear assumption, several studies have attempted to investigate the curvilinear functional form. Williams and Holmes (Citation1981) study first predicted a negative effect on sexual assault against women in the early stages of women’s liberation. Bailey (Citation1999) first introduced time (referring to changes in gender inequality and gender-based violence) into the models and discovered that, while cross-sectional analyses reported backlash effects, analyses of change and lagged effects using panel data revealed ameliorative effects. Whaley’s (Citation2001) research developed a “refined feminist theory” in order to contextualize the intricate roles of gender inequality and reached a similar conclusion that the amelioration and backlash hypotheses are not necessarily contradictory or oppositional but represent processes occurring over different time periods (long term versus short time effects). Viewed over a longitudinal plane, the hypotheses become compatible. Most recently, Whaley et al. (Citation2013) established a quadratic model with a squared term of gender equality, resulting in an inverted U-shaped relationship between the degrees of gender equality and men’s violence against women. To further interpret such a relationship, analyses disaggregated by victim/offender relationships, especially intimate partner relationships, are required (Whaley et al., Citation2013).

According to the above reviews of the refined theory, we can hypothesize that in China, the relationship between gender inequality and likelihood of FV-IPH should be an inverted U, with the upward slope indicating a backlash effect as the gender system is radically reformed towards equality; and the subsequent downward slope implying the dominance of amelioration processes at somewhat intermediate to high levels of gender equality.

Methodology

Data Sources and Measures

Data on Homicide at the Incident Level

As an extreme form of violence, homicide has relatively high police detection and clearance rates (Mouzos, Citation2002). As a result, homicide is one of the few crime classifications where official statistics provide relatively reliable prevalence estimates, attracting the attention of a wide range of scholars from various disciplines (Loftin et al., Citation2015). While the bulk of previous research has relied on arrest statistics (e.g. the police Supplementary Homicide Report (SHR) data of the U.S.), such police records are not available in China. In this study, the authors obtained an entire collection of first-instance homicide judgmentsFootnote3 (from 2017 to 2019) from the China Judgments Online (CJO) website. After removing cases that were deemed “inappropriate to publicize” or lacked key information, as well as duplicated and miscategorized documents, the final dataset contains 11,310 cases. The study then used Python to design rule-based information extraction algorithms to code relevant incident-level information following previous studies analyzing Chinese judgments (e.g. Michelson, Citation2019; Xin & Cai, Citation2020).Footnote4

In this study, the dependent variable is whether the homicide case had a female victim and was committed by an intimate male partner (1 = FV-IPH; 0 = other homicide).Footnote5 To account for potential fluctuations, homicide statistics are based on three-year averages (2017–2019), consistent with previous homicide studies (e.g. Reckdenwald, Citation2008; Whaley et al., Citation2013).

Several incident-specific covariates are chosen from existing literature and based on data availability to isolate the direct effects of provincial-level gender inequality on FV-IPH. Offenders’ age, minority statusFootnote6 (1 = ethnic minority; 0 = Han), and urban-rural division (1 = rural; 0 = urban) are all controlled. As some specified individual and situational characteristics could indirectly indicate the offender’s risk of committing FV-IPH when engaging in violence (Overstreet et al., Citation2021), key legal factors in these homicide cases are also controlled according to the legal and criminal justice literature (DeJong et al., Citation2011; Overstreet et al., Citation2021), including offenders’ crime records (1 = yes; 0 = no), whether the homicide was committed under the influence of alcohol or drugs (1 = yes; 0 = no), and whether there are multiple victims involved or not (1 = multiple victims; 0 = one victim). In addition, the court level (1 = intermediate people’s court/higher people’s court; 0 = primary people’s court) is included, indicating the seriousness of the cases.Footnote7 Missing observations (<7.2%) were imputed by using Multiple Imputations by Chained Equations (MICE; Van Buuren & Oudshoorn, Citation1999).

Data on Provincial Gender Inequality Indicators

The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) has developed the Gender Inequality Index (GII) as a comprehensive measure of gender inequality, ranging from 0 to 1, where 0 represents a high level of gender equality and 1 represents a high level of gender inequality (UNDP, 2016). The GII is a commonly used indicator in previous studies on intimate partner homicide (e.g. González & Rodríguez-Planas, Citation2020). Usually, the GII includes three dimensions of human development: health inequality (GII-H), empowerment inequality (GII-E), and labor market inequality (GII-L) (see details in Gaye et al., Citation2010; Permanyer, Citation2013). Scholars have cautioned against using a unidimensional approach to measure gender inequality, as it may fail to capture the complex and multifaceted nature of the construct (Whaley et al., Citation2013). In light of this, the present study seeks to account for the multidimensionality of structural gender inequality by incorporating the values of the three GII dimensions separately across provinces.

The calculation of the health inequality dimension of GII consists of the provincial maternal mortality ratio and adolescent birth rate; gender inequality in the dimension of empowerment inequality is measured using the ratio of attainment of at least secondary education and the share of parliamentary seats in each province (here ‘parliament’ refers to the people’s congress in the Chinese context) of men and women; and the labor market inequality dimension is operationalized using the provincial ratio of labor force participation of men and women. Four steps are needed to calculate the GII. Step 1 is obtaining the geometric mean for the three dimensions of GII for each gender group. Step 2 is calculating the harmonic means to aggregating across gender groups. Step 3 computes the arithmetic means for each dimension, thereby establishing a reference standard. Finally, step 4 is calculating the gender inequality indices which account for differences between women and men while adjusting for association (or overlapping) between inequality indicators (Gaye et al., Citation2010).Footnote8

However, GII has long been criticized for overemphasizing the economic and material dimensions of women’s disadvantages while ignoring inherent cultural aspects in determining the extent of patriarchal gender ideology in each society (Permanyer, Citation2013). Prior results appear to imply that socio-economic factors contribute little to understanding the problem of women’s victimization (Vieraitis et al., Citation2008). Accordingly, scholars emphasize the importance of carefully shifting more emphasis to cultural factors. Some existing studies have included natality inequality (son preference) as a cultural aspect of gender inequality. Without any interruptions, the ‘expected’ sex ratio at birth is quoted as 102-105 male births per 100 female births (Chao et al., Citation2019). Unfortunately, some societies exhibit a strong preference for male offspring, leading to higher levels of sex ratio at birth (SRB) derived from excess female child mortality and sex-selective abortion. Such culturally rooted discrimination against women is persistent and self-perpetuated since women themselves have internalized it; women’s achievements in socioeconomic opportunities are also hard to reduce such cultural effects even in middle-income countries (Amartya, Citation2003; Das Gupta et al., Citation2003). The levels of gender inequality thus need to be measured by combining the prior three dimensions of GII and the cultural aspect (indicated by SRB). A study that employed the refined GII has demonstrated that SRB is a more influential factor of the global gender gap in suicide than the other dimensions of GII (Chang et al., Citation2019).

Moreover, progress toward gender equality in China has been pronounced in the policy-driven area of equal-opportunities rather than in the attainment of an advanced gender-equitable culture (Qian & Li, Citation2020). The persistent “son preference” in China is a product of a Confucian patriarchal tradition, and is widely regarded as a proxy for a region’s female subordination (Attané, Citation2009). In general, China’s SRB is significantly higher than the global average, and the SRBs also vary greatly among different provinces (National Bureau of Statistics, Citation2021),Footnote9 demonstrating the seriousness of cultural gender inequality and the necessity to incorporate SRB when examining provincial gender inequality within China. The SRB data comes from China’s Sixth National Population Census (the closest census year to 2017-2019).

This study, like previous homicide studies (e.g. Reckdenwald, Citation2008; Whaley et al., Citation2013), controlled for each province’s crude divorce rate (‰) at a three-year average, representing exposure between intimate partners. The divorce rate statistics were obtained from the annual China Statistical Yearbook (2017–2019).

Analyses

Descriptive statistics for provincial-level indices and incident-level features are first presented. Next, because observations in this study are nested within their respective provinces, a series of hierarchical logistic regression models are estimated to assess the effects of provincial gender inequality on the probability of a homicide case being FV-IPH or non-FV-IPH, in line with prior research examining the structural effects on individual offenses (e.g. Wright et al., Citation2016). The combination of CJO homicide data and provincial-level gender inequality indices allows for multilevel analysis since there are enough units (31 provinces) (Jowell et al., Citation2007). The initial step tests whether a significant proportion of the total variance in the outcome variables exists at the higher level of units (i.e., the province-level effects) (Raudenbush & Bryk, Citation2002). Using hierarchical models, the effects of provincial-level (Level 2) factors on the likelihood of FV-IPH are tested while controlling for incident-level (Level 1) factors. The likelihood of FV-IPH is assumed to be influenced by individual-level factors at level 1 through a Logistic Regression Model: whereas the FV-IPH probability,

is the intercept, and

is a vector of the coefficients associated with the individual-level predictor

. At level 2, it is assumed that provincial-level factors influence the intercept:

whereas the intercept located at the level 1 model which is constant across all provinces in the dataset,

is a vector of the coefficients associated with provincial-level predictors

, and

is a random effect associated with each individual j of province i (

). Substituting the level 2 model into the level 1 model yields the final model:

. To test Hypothesis 3, we used Lind and Mehlum (Citation2010) procedure and criterion to rigorously test for an inverted-U-shaped relationship between gender inequality and FV-IPH.Footnote10 The multilevel analyses were applied to have a more careful examination of the contextual effects of structural gender inequalities while controlling for incident-level factors. It was conducted in Stata 15 using melogit.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

The analysis begins with presenting incident-level descriptive statistics in terms of all the homicide cases from 2017 to 2019 and FV-IPH cases (accounting for 30.5% of homicide cases). The defendants’ average age is around 42, indicating that middle-aged Chinese people are at high risk for committing homicide. More than half of all homicides occurred in rural areas (63.11%). For FV-IPH, 56.95% of the cases occurred in rural China. Criminal records were uncommon (all homicide cases: 9.73%; FV-IPH cases: 7.71%). In terms of homicide situational information, less than one-third of homicide cases occurred under the influence of alcohol or drugs (all homicide cases: 29.28%; FV-IPH cases: 23.87%). As the most serious type of crime, which can result in the death penalty or life imprisonment, more than 60% of homicide cases in the current sample were handled by intermediate or higher people’s courts.

Table 1. Descriptive results and bivariate statistics of incident-level factors.

The descriptive statistics for the provincial-level factors are shown in . The provincial FV-IPH rate averaged 1.705 cases per million people, with a range of .197 to 3.472.Footnote11 In terms of provincial gender inequality, the average scores of gender inequality in the domains of health inequality, empowerment inequality, and the labor market inequality are .220 ([.005, .583]), 0.073 ([.015, .170]), 0.061 ([.013, .118]), respectively. Referring to cultural gender inequality, the average sex ratio at birth is 118.390, ranging from 100.080 to 131.070.

Table 2. Descriptive results of provincial-level factors.

Multilevel Analyses

The logistic coefficients and odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals for all the variables as well as goodness of fit indices of all the hierarchical models are shown in . First, a Baseline Model (Model 1) was estimated using all the incident-level variables while adjusting for possible clustering at the provincial level using random intercepts. According to the results of model 1, a significant portion of the variance in the outcome occurs across provinces (provincial-level variance component = .015; p < .01). As a result, multilevel analyses would be the appropriate next step to capture the associations among the outcome and independent variables across levels.

Table 3. Results of hierarchical models (N = 11,310).

The Linear Model (Model 2) was then used to test Hypothesis-1 and Hypothesis-2 by introducing first-order terms of each provincial-level factor into the Baseline Model. After controlling for the other variables, higher levels of gender inequality in the empowerment dimension appear to be significantly associated with a lower likelihood of FV-IPH (OR = .077, p < .05), lending support to the backlash hypothesis. As predicted by the amelioration hypothesis, higher levels of gender inequality in the labor market are linked to a higher likelihood of FV-IPH (OR = 11.531, p < .05). Gender inequality in health and the first-order SRB term has no significant relationship with FV-IPH. Model 2 demonstrates a negative relationship between an increasing provincial divorce rate and a decreasing presence of FV-IPH (OR = .926, p < .05).

According to Hypothesis-3, the cross-sectional relationship between levels of gender inequality and the likelihood of FV-IPH is unlikely to take the linear functional form typically modeled in prior FV-IPH research from the two traditional feminist perspectives. To specify the functional form and properly test for the presence of a hypothesized inverted U-shaped relationship, rigorous tests were conducted following Lind and Mehlum (Citation2010) procedure. The quadratic relationship between SRB (representing cultural gender inequality) and FV-IPH is significant, as shown in .Footnote12 Model 3 evaluates Hypothesis 3 by estimating a regression model with an SRB term and an SRB squared term. After fixing the incident-level characteristics and other provincial indices, an increase in the quadratic term of sex ratio at birth by 1 unit is associated with a 0.1% decrease in the odds of FV-IPH (OR = .999, p < .05),Footnote13 indicating an inverted U-shaped relationship. It appears that the backlash processes are likely to predominate as the SRB level (indicating cultural gender inequality) decreases from its peak where boys greatly outnumber girls; and the ameliorative effects are more potent at somewhat intermediate to low levels of patriarchal culture. When SRB is around 118.928, which is well within the data range (from 100.1 to 131.1), the extreme point appears. provides an additional visual representation of the curvilinear relationship between SRB and the predicted probability of FV-IPH. As regional gender equality improves, the rate of FV-IPH initially rises, indicated by the shift from the SRB of 131 to 119; however, progress beyond the peak of this inverted-U trend, approximately at an SRB of 119, amelioration will have a much greater impact on FV-IPH. Furthermore, higher levels of gender inequality in terms of women’s empowerment are still associated with a lower likelihood of FV-IPH (OR = .089, p < .05). However, the effect of gender inequality in the labor market domain diminishes to non-significance.

Table 4. Estimates of the inverted U curves.

Finally, a series of post hoc analyses were performed to further investigate the robustness of the results.Footnote14 To ensure that the results were consistent across different measurements, supplemental analyses were conducted using an alternative measure of patriarchal gender ideology proposed by Jiang and Zhang (Citation2021). Given the spread of mass education in China, the models were also tested with an alternative empowerment inequality indicator calculated by female and male indices of tertiary education attainment and political participation. The findings withstand the robustness tests. Moreover, when employing alternative coding schemes for the dependent variable which excluded male-victim intimate partner homicide and other instances of gender-motivated femicide, the supplemental analyses yielded consistent findings. We also assessed the robustness with control of several potential confounding variables, e.g. the age structure of regional populations, and the proportion of urban and rural recipients of subsistence allowances (Dibao). The pattern of findings remained unchanged.

Discussion

Violence against women has become a global problem of epidemic proportions (World Health Organization, Citation2013). Researchers have issued calls for action plans driven by research based on appropriate methodologies. The purpose of this study is to determine whether and how multidimensional aggregate-level gender inequality is related to FV-IPH in the Chinese context. Using large-scale Chinese judgments, our analyses test 1) The traditional amelioration and backlash propositions, which suggest that the relationship fits a linear function but in opposite directions; and 2) The “refined feminist perspective”, which proposes a curvilinear functional form.

Findings of the current research lend partial support to the backlash hypothesis. Both the amelioration hypothesis and the backlash hypothesis agreed that with social development, women were empowered with greater opportunities for political participation and educational attendance, endorsed egalitarian gender ideology, and displayed more dominant traits such as being directive and competitive (Archer, Citation2006). However, the backlash group argued that such increased gender equality may have a negative impact. Men may use social structures that allow certain types of violence as resources to pursue a gender strategy and construct their masculinity (Messerschmidt, Citation1996). Women’s empowerment and movement away from rigid gender stereotypes may preclude such gender-specific social structure resources, fostering men’s perception of a threatened status quo (i.e., the subordination of women to men). As a result, FV-IPH may be utilized as a means of preserving male dominance over their female partners. According to Whaley’s (Citation2001) research, women’s increasing share of seats in elite occupations and presence in higher education may pose the greatest threat to men’s status quo. Equal opportunities in the labor market and egalitarian divisions of labor at home benefit highly educated women the most (Pampel, Citation2011). Women would be “rewarded” with a lower risk of victimization if they did not challenge men in important status areas (Bailey, Citation1999, p. 24). Hence, it is understandable that women’s involvement in less traditional social roles and their share of higher academic degrees may put them at a higher risk of FV-IPH victimization. While not bearing a direct link with violent behaviors, Qian (Citation2012) has identified certain backlash effects in China: owing to Chinese men’s negative attitudes towards women who deviate from conventional gendered domestic roles, highly educated women experienced a "marriage squeeze" and became less likely to get married. Consistent with extant social research, our study provides further support to the proposition that positive social developments may generate unintended consequences and come with problems. Such findings encourage researchers to embrace the complexities of gender equality and look into policies and interventions that can buffer the deleterious backlash effects, paying more attention to those men with persistent gender stereotypes.

The current study found no strong support for the amelioration hypothesis. Declined gender inequality in the health and empowerment dimensions is not that effective in reducing the FV-IPH risks. Only gender inequality in the labor market domain was in the expected positive direction in predicting the likelihood of FV-IPH. Here’s a conundrum: why do women’s increasing labor-force participation rates, which also represent women’s higher socio-economic status and empowerment, not result in more FV-IPH as the backlash hypothesis suggests? The reason might be that the Chinese government has actively promoted female labor force participation as a critical means of enhancing economic development and women’s liberation; China’s female labor force participation rates thus have been among the highest on a global scale (Attané, Citation2012). Its socialist propaganda also challenged the conservative discourse of gender division in the workplace. As a result, women’s identities in the workplace are commonly affirmed, and beliefs in equal employment rights are acceptable for both Chinese men and women. However, the incorporation of the quadratic SRB nullified the significance of labor force participation, to some extent affirming the salience of the cultural aspect of gender inequality. It also implies that the labor force participation rate assessment may be insufficient because it likely underestimates the extent of economic gender inequality (e.g. missing concerns on the gendered division of labor and unpaid work performed by women) (see a review in Berik, Citation2022). Existing studies have provided various evidence that while women’s employment has increased dramatically, inequality in segregated occupations, gender pay gaps, and unequal opportunities for advancement persist in China’s labor market (Ji et al., Citation2017). Further institutional reforms are imperative for the systematic mitigation of women’s disadvantages in the economic realm.

While increases in gender equality brought about by “instrumental social policies” are found to be linearly related to FV-IPH, regarding gender equality in the cultural dimension, Whaley et al. (Citation2013) hypothesis suggesting an inverted-U-shaped relationship is supported. Along with its rapid and large-scale economic boom, China’s GII has been ranked in the world’s bottom quartile (UNDP, Citation2020), indicating unprecedented achievement in terms of gender equality in the domains of health, labor market and empowerment. However, China’s SRB has remained to be one of the highest in the world for several decades (118.6/100 women in 2005 and 113.5/100 women in 2021). Such abnormally high levels of SRB reveal China’s deep-rooted culture-based gender discrimination, which is formidable to change with economic development (UNICEF, Citation2021). Our results demonstrate additional support to this ‘China paradox’ (inconsistency between cultural gender inequality and other aspects of gender inequality): in the Chinese context, it appears the non-linear cultural effects (SRB) exhibit greater sensitivity to FV-IPH in comparison to other indicators of gender inequality. Why this is the case? Partially related to the one-child policy (political support to relax the cultural constraints among girls and girls’ families), a large amount of Chinese women have accepted and internalized gender-egalitarian attitudes, while their male counterparts are highly lagged behind (Qian & Li, Citation2020). During the initial phases of the reforms toward gender equality, when power relations undergo a shift, there is a heightened probability of encountering increased gender rigidity and backlash to egalitarian pressures, particularly in societies characterized by long-standing patriarchal institutional structures (Forsythe et al., Citation2000; Pimentel, Citation2006). As a result, women who challenge conventional gender roles may pose a threat to men’s hegemonic masculinity, especially in provinces with more conventional gender-related culture (indicated by higher levels of SRB). Such cultural or attitudinal conflicts between men and women might lead to more FV-IPH.

However, the gender gap in egalitarian gender attitudes would narrow as a result of legislation, education, and media campaigns. New gender norms can be defined, diffused, and gradually accepted, leading to the erosion of traditional “male-breadwinner, female-homemaker” roles and a new construction of masculinity—men would rarely “do hegemonic masculinity” by battering their wives. Hence, it is reasonable to embrace the complex dynamic processes that altering deeply rooted cultural prescriptions of gender would initially exacerbate women’s burden of intimate partner violence but would be followed by ameliorative effects as gender stratification ranges from intermediate levels of inequality to low levels of inequality. It is worth noting, finally, that the inverted U-shaped relationship should not be interpreted as a “Safe Zone” for women when culturally embedded gender discrimination is at its peak. When there is a high level of gender stratification, patriarchal gender ideology may include protections for women as a form of social control and guardianship. However, it should be noted that such protections apply if, and only if, women are “Good Wives” who fully adhere to conservative gender norms, which further burdens women (Dery et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, extreme gender discrimination leads to other “Hidden Dangers,” such as the pervasive gender imbalance problem in rural China and the resulting problems of “Sex-starved violent bachelors” (Greenhalgh, Citation2013). All these findings suggest that China needs to continue its efforts to reduce gender equality by developing a comprehensive strategy to address both socioeconomic dimensions and cultural factors.

In addition, the results for some of the control variables in the hierarchical models are theoretically interesting. A higher divorce rate at the provincial level is associated with a lower likelihood of FV-IPH perpetration. According to the exposure reduction hypothesis, decreased spousal homicide is, to some extent, a function of domesticity change (marriage rates plummeted and divorce rates increased), which includes the age groups at highest intimate partner homicide victimization/offending risk (Dugan et al.,Citation1999). Relationship separation reduces the exposure of couples in discordant relationships, resulting in fewer opportunities to commit FV-IPH. There was empirical evidence in the U.S. literature that intimate partner homicide reduction was due to declining domesticity (Rosenfeld, Citation1997). Furthermore, descriptive statistics and the inclusion of incident-level factors in hierarchical regressions help to paint a rough portrait of FV-IPH cases and their male perpetrators. Notably, male perpetrators with prior criminal records or alcohol/drug problems are more likely to engage in non-FV-IPH violent offenses, such as economically-driven homicide or revenge-based homicide, etc. Moreover, while rural contexts are viewed as having a predominance of hegemonic cultural beliefs (Ridgeway & Correll, Citation2004), urban men have a higher propensity to commit FV-IPH in contemporary China than their rural counterparts. For socioeconomically marginalized urban males (more severe inequality in cities), the notion of male dominance is perceived as insecure due to a lack of perceived dominance in other aspects of their social lives (Hall, Citation2002). Those men may increase their use of force against women, which is the only type of power they still have, to reassert their dwindling patriarchal power and authority. However, this does not imply that rural women should be considered secure. To some extent, the relatively lower likelihood of lethal violence against women in rural China may be attributed to the critical role of wives in farm family economies, as well as a bride shortage accompanied by expensive “Bride Prices” (Greenhalgh, Citation2013). Future research shall look into intimate partner aggravated assaults, as well as mild violence reported in divorce petitions, as rural areas in China may exhibit a higher likelihood of non-lethal intimate partner violence. Given that the present study is predominantly guided by three macro-level theories pertaining to gender inequality and FV-IPH, the observations emerging from these controlled incident-level factors and potential cross-level effects warrant future research endeavors.

A notable limitation of this study is about the issue of unreported crime, also known as the “Dark figure of crime”. It means that official crime statistics have an infamous reputation for being a somewhat inaccurate reflection of the true nature and extent of crime (Coleman & Moynihan, Citation1996). A crime must be reported to the appropriate policing authorities and found guilty in court before it can be included in the CJO’s official statistics. Otherwise, such unreported crimes go undetected, leaving unidentified suspects. Moreover, the CJO data likely reflects law enforcement actions in addition to criminal behavior. The clearance rates for crimes, when analyzed across various jurisdictions and gender groups, have the potential to introduce data skewness. Consequently, it is imperative to acknowledge the possibility of detection and sentencing bias, which cannot be entirely dismissed, as it may exert an influence on collider bias within our findings.Footnote15 Nonetheless, as an extreme form of violence, homicide has relatively high police detection and clearance rates. In 2019, homicide clearance rates in China reached 99.8% (The Ministry of Public Security of the PRC, Citation2020). Furthermore, China’s annual homicide rate is consistent with the UNODC report (2019) based on a three-year average value (2017-2019). Therefore, this study used intentional homicide cases that official statistics provide relatively reliable prevalence estimates for. Finally, it should be noted that due to the restrictive uploading or purposeful deletion of cases on the CJO, the sample in the current study does not include the entirety of homicide cases. Going forward, future research needs to employ an appropriate research design to collect new types of Chinese data to minimize such bias.

Similar to other homicide studies using secondary official data sources, the present study bears the inherent shortcoming of insufficient information in official documents. The information missing from these judgments, such as the detailed social status of the offenders and the victims and their personal gender attitudes, greatly impedes our understanding on the intricate mechanisms of FV-IPH. Future empirical studies need to intentionally accumulate and collect more in-depth multilevel data to thoroughly examine the complex relationship between gendered social structures and individual actions, as suggested by Risman (Citation2017). In the retrieved judgments, several common extra-legal factors and situational factors were partially collected or released. Failing to control for those factors may jeopardize the validity of the findings. To gain a better understanding of FV-IPH, in future research, qualitative analyses of the dynamics of gendered interpersonal violence, such as interviews with homicide perpetrators, women who had survived a homicide attempt by a partner, or proxy victims, would be important to complement the big-data analyses represented in the current research.

Conclusion

The present study is a novel investigation of the uneven development of gender equality and its impact on violence against women in China, which assumes significance amidst the escalating global concerns on this issue. It addresses the theoretical controversy surrounding the direction (i.e., amelioration or backlash) and functional form (i.e., linear or inverted-U) of the association between gender equality and FV-IPH. This research utilized three-year national-level homicide judgments involving 11,310 cases and 31 provinces, advanced data mining techniques, and comprehensive indicators of gender inequality (namely, health, empowerment, labor market, and culture) to provide robust support for the curvilinear effects, encompassing both amelioration and backlash, of cultural gender inequality on FV-IPH. In comparison, non-cultural gender inequality exhibited some significant backlash effects (only in the domain of empowerment inequality). That is, promoting gender equality and alleviating FV-IPH shall go beyond improving opportunities in education and political participation. We need long-term strategies to transform the persistent patriarchal culture, and particularly cultivate egalitarian gender ideology among men. The present research expands our comprehension of three macro-level theories by highlighting the intricate nature of gender inequality, and pinpointing the salience of the cultural aspects of gender inequality in the mechanisms of FV-IPH.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (2.2 MB)Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The current study adopts the elements that feminist criminologists indicate may contribute to labeling a crime as “FV-IPH”. Consistent with prior studies, intimate partners in the current research include spouses, cohabitants, ex-spouses, boyfriends/girlfriends, and extra-marital lovers. For the purposes of this study, homosexual relationships are excluded.

2 The analyses in the current research focus on 31 provincial-level administrative regions in mainland China (Homicide data from Hong Kong and Macau SARs, and Taiwan province were excluded).

3 This study utilizes the judgment documents of cases involving defendants who "intentionally committed homicide" and were charged with a violation of Article 232 of the Criminal Code according to the Criminal Law of the People’s Republic of China.

4 Detailed information about our data-mining processes is depicted in the Online Appendix (pages 46–50).

5 To ensure the validity of the results, we performed supplementary analyses with alternative dependent variables, detailed in online Appendix Tables 7 and 8. The analyses yielded patterns consistent with those presented in the main tables.

6 Fifty-five ethnic minorities alongside the Han-majority have been officially classified in China. More than 125 million people belong to the 55 minorities, occupying 8.89% of the total population (National Statistics Bureau, 2021).

7 In China, cases proceeded in primary people’s courts indicate less seriousness than those trialed in higher-level courts.

8 Detailed definitions and calculations of the indices are provided in & . To provide an example of how to calculate the gender inequality indices, we also demonstrated the computation of Beijing’s gender inequality indices in the Online Appendix (see Appendix Table 4). And the mapping techniques provide clear evidence that patterns of provincial-level gender inequality in the health, empowerment, and labor market domains are far from uniform in China (see online Appendix Figure 2).

9 Provinces with high levels of gender equality in the equal-opportunity dimensions (e.g., Guangdong province) may continue to adhere to entrenched traditional patriarchal values that discriminate against girls/prefer sons. The distribution map clearly shows that 13 of China’s 31 mainland provinces have an SRB greater than 120, and 14 provinces have an SRB between 112 and 120 (see online Appendix Figure 3).

10 Detailed procedure and test results for an inverted-U-shaped relationship following Lind and Mehlum (Citation2010) are shown in the online appendix (page 56–58).

11 Figures in online Appendix Figure 4 depict the overall distributions of FV-IPH across Chinese provinces, illustrating distinct heterogeneity within China.

12 Estimates of the inverted U curves for the other three gender inequality indices (i.e., GII-Health, GII-Empowerment, GII-Labour force participation) see .

13 Our index indicating cultural gender inequality, i.e., the sex ratio at birth, ranges from 100.1 to 131.1 (means that for every 100 girls, approximately 100.1 to 131.1 boys were being born). Taking two provinces, Heilongjiang and Shaanxi (whose sex ratio at birth is 115.1 and 116.1, respectively), as an example, 1 unit change (from 115.1 to 116.1) in the sex ratio at birth refers to a change in the quadratic term of sex ratio at birth by around 231 units (116.12-115.12), which is associated with a 26.6% change in the odds of FV-IPH:

Such an effect size might be regarded as quite considerable in the case of macro-level predictors of crime.

14 Detailed results of the supplementary analyses are shown in the Online Appendix (pages 53–56).

15 A discussion of potential collider bias is available in the Online Appendix (pages 51–53).

References

- All-China Women’s Federation. (2019). http://www.spcsc.sh.cn/n1939/n1944/n1945/n2300/u1ai199731.html

- Amartya, S. (2003). Missing women—revisited. BMJ, 327(7427), 1297–1298.

- Anderson, K. L. (2005). Theorizing gender in intimate partner violence research. Sex Roles, 52(11–12), 853–865. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-005-4204-x

- Anderson, K. L. (2009). Gendering coercive control. Violence against Women, 15(12), 1444–1457. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801209346837

- Archer, J. (2006). Cross-cultural differences in physical aggression between partners: A social-role analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Review: An Official Journal of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc, 10(2), 133–153. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr1002_3

- Attané, I. (2009). The determinants of discrimination against daughters in China: Evidence from a provincial-level analysis. Population Studies, 63(1), 87–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/00324720802535023

- Attané, I. (2012). Being a woman in China today: A demography of gender. China Perspectives, 2012(4), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.4000/chinaperspectives.6013

- Bailey, W. C. (1999). The socio-economic status of women and patterns of forcible rape for major US cities. Sociological Focus, 32(1), 43–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/00380237.1999.10571123

- Bailey, W. & Peterson, R. (1995). 8. Gender Inequality and Violence Against Women: The Case of Murder. In J. Hagan & R. Peterson (Ed.), Crime and Inequality (pp. 174-205). Redwood City: Stanford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781503615557-010

- Berik, G. (2022). Towards improved measures of gender inequality: An evaluation of the UNDP gender inequality index and a proposal. United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women (UN Women).

- Brownmiller, S. (1975). Against our will: Men, women and rape. Simon & Schuster.

- Carrington, K., Hogg, R., & Sozzo, M. (2016). Southern criminology. British Journal of Criminology, 56(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azv083

- Chan, H. C., Li, F., Liu, S., & Lu, X. (2019). The primary motivation of sexual homicide offenders in China: Was it for sex, power and control, anger, or money? Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health: CBMH, 29(3), 168–178. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbm.2114

- Chang, Q., Yip, P. S., & Chen, Y. Y. (2019). Gender inequality and suicide gender ratios in the world. Journal of Affective Disorders, 243, 297–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.09.032

- Chao, F., Gerland, P., Cook, A. R., & Alkema, L. (2019). Systematic assessment of the sex ratio at birth for all countries and estimation of national imbalances and regional reference levels. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 116(19), 9303–9311. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1812593116

- Chon, D. S., & Clifford, J. E. (2020). Cross-national examination of the relationship between gender equality and female homicide and rape victimization. Violence against Women, 27(10), 1796–1819. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801220954283

- Chrisler, J. C., & Ferguson, S. (2006). Violence against women as a public health issue. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1087(1), 235–249. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1385.009

- Coker, A. L., Williams, C. M., Follingstad, D. R., & Jordan, C. E. (2011). Psychological, reproductive and maternal health, behavioral, and economic impact of intimate partner violence. In J. W. White, M. P. Koss, & A. E. Kazdin (Eds.), Violence against women and children, Vol. 1. Mapping the terrain (pp. 265–284). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/12307-012

- Coleman, C., & Moynihan, J. (1996). Understanding crime data: Haunted by the dark figure (Vol. 120). Open University Press Buckingham.

- Cooper, A., & Smith, E. L. (2012). Homicide trends in the United States, 1980-2008. BiblioGov.

- Dalal, D. K., &Zickar, M. J. (2012). Some Common Myths About Centering Predictor Variables in Moderated Multiple Regression and Polynomial Regression. Organizational Research Methods, 15(3), 339–362. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428111430540

- Das Gupta, M., Zhenghua, J., Bohua, L., Zhenming, X., Chung, W., & Hwa-Ok, B. (2003). Why is son preference so persistent in East and South Asia? A cross-country study of China, India and the Republic of Korea. The Journal of Development Studies, 40(2), 153–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380412331293807

- Davis, D., & Harrell, S. (1993). Chinese families in the post-Mao era (Vol. 17). Univ of California Press.

- DeJong, C., Pizarro, J. M., & McGarrell, E. F. (2011). Can situational and structural factors differentiate between intimate partner and “other” homicide? Journal of Family Violence, 26(5), 365–376. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-011-9371-7

- Densley, J. A., Hilal, S. M., Li, S. D., & Tang, W. (2017). Homicide–suicide in China: An exploratory study of characteristics and types. Asian Journal of Criminology, 12(3), 199–216. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-016-9238-1

- Dery, I., Akurugu, C. A., & Baataar, C. (2022). Community leaders’ perceptions of and responses to intimate partner violence in Northwestern Ghana. PloS One, 17(3), e0262870. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0262870

- Dugan, L., Nagin, D. S., & Rosenfeld, R. (1999). Explaining the decline in intimate partner homicide: The effects of changing domesticity, women’s status, and domestic violence resources. Homicide Studies, 3(3), 187–214. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088767999003003001

- Dworkin, S. L.,Hatcher, A. M.,Colvin, C., &Peacock, D. (2013). Impact of a Gender-Transformative HIV and Antiviolence Program on Gender Ideologies and Masculinities in Two Rural, South African Communities. Men and Masculinities, 16(2), 181–202. https://doi.org/10.1177/1097184X12469878

- Echambadi, Raj., &Hess, J. D. (2007). Mean-Centering Does Not Alleviate Collinearity Problems in Moderated Multiple Regression Models. Marketing Science, 26(3), 438–445. https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.1060.0263

- Fan, S., Kanbur, R., & Zhang, X. (2011). China’s regional disparities: Experience and policy. Review of Development Finance, 1(1), 47–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rdf.2010.10.001

- Forsythe, N., Korzeniewicz, R. P., & Durrant, V. (2000). Gender inequalities and economic growth: A longitudinal evaluation. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 48(3), 573–617. https://doi.org/10.1086/452611

- Fry, M. W., Skinner, A. C., & Wheeler, S. B. (2019). Understanding the relationship between male gender socialization and gender-based violence among refugees in Sub-Saharan Africa. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 20(5), 638–652. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838017727009

- Frye, V., Galea, S., Tracy, M., Bucciarelli, A., Putnam, S., & Wilt, S. (2008). The role of neighborhood environment and risk of intimate partner femicide in a large urban area. American Journal of Public Health, 98(8), 1473–1479. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2007.112813

- Gaye, A., Klugman, J., Kovacevic, M., Twigg, S., & Zambrano, E. (2010). Measuring key disparities in human development: The gender inequality index. Human Development Research Paper, 46, 1–37.

- Gillespie, L. K., & Reckdenwald, A. (2017). Gender equality, place, and female-victim intimate partner homicide: A county-level analysis in North Carolina. Feminist Criminology, 12(2), 171–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557085115620479

- González, L., & Rodríguez-Planas, N. (2020). Gender norms and intimate partner violence. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 178, 223–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2020.07.024

- Greenhalgh, S. (2013). Patriarchal demographics? China’s sex ratio reconsidered. Population and Development Review, 38(s1), 130–149. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2013.00556.x

- Hall, S. (2002). Daubing the drudges of fury: Men, violence and the piety of the ‘hegemonic masculinity’ thesis. Theoretical Criminology, 6(1), 35–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/136248060200600102

- Heise, L. L. (1998). Violence against women: An integrated, ecological framework. Violence against Women, 4(3), 262–290. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801298004003002

- Heise, L. L., & Kotsadam, A. (2015). Cross-national and multilevel correlates of partner violence: An analysis of data from population-based surveys. The Lancet. Global Health, 3(6), e332–e340. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00013-3

- Inglehart, R., & Norris, P. (2005). Modernization and gender equality: A response to Adams and Orloff. Politics & Gender, 1(03), 482–492. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X0522113X

- Ivert, A. K., Gracia, E., Lila, M., Wemrell, M., & Merlo, J. (2020). Does country-level gender equality explain individual risk of intimate partner violence against women? A multilevel analysis of individual heterogeneity and discriminatory accuracy (MAIHDA) in the European Union. European Journal of Public Health, 30(2), 293–299. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckz162

- Ji, Y., & Wu, X. (2018). New gender dynamics in post-reform China: Family, education, and labor market. Chinese Sociological Review, 50(3), 231–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/21620555.2018.1452609

- Ji, Y., Wu, X., Sun, S., & He, G. (2017). Unequal care, unequal work: Toward a more comprehensive understanding of gender inequality in post-reform urban China. Sex Roles, 77(11–12), 765–778. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-017-0751-1

- Jiang, Q., & Zhang, C. (2021). Recent sex ratio at birth in China. BMJ Global Health, 6(5), e005438. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-005438

- Jowell, R., Roberts, C., Fitzgerald, R., & Eva, G. (Eds.). (2007). Measuring attitudes cross-nationally: Lessons from the European Social Survey. Sage.

- Kiss, L., Schraiber, L. B., Heise, L., Zimmerman, C., Gouveia, N., & Watts, C. (2012). Gender-based violence and socioeconomic inequalities: Does living in more deprived neighbourhoods increase women’s risk of intimate partner violence? Social Science & Medicine (1982), 74(8), 1172–1179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.033

- Lauritsen, J. L., & Heimer, K. (2008). The gender gap in violent victimization, 1973–2004. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 24(2), 125–147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-008-9041-y

- Lehti, M., & Kivivuori, J. (2012). Homicide in Finland. In Handbook of European homicide research (pp. 391–404). Springer.

- Lei, M. K., Simons, R. L., Simons, L. G., & Edmond, M. B. (2014). Gender equality and violent behavior: How neighborhood gender equality influences the gender gap in violence. Violence and Victims, 29(1), 89–108. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-12-00102

- LeSuer, W. (2020). An international study of the contextual effects of gender inequality on intimate partner sexual violence against women students. Feminist Criminology, 15(1), 97–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557085119842652

- Levinson, D. (1988). Family violence in cross-cultural perspective (pp. 435–455). Springer US.

- Lind, J. T., & Mehlum, H. (2010). With or without U? The appropriate test for a U-shaped relationship. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 72(1), 109–118. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0084.2009.00569.x

- Loftin, C., McDowall, D., Curtis, K., & Fetzer, M. D. (2015). The accuracy of Supplementary Homicide Report rates for large US cities. Homicide Studies, 19(1), 6–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088767914551984

- Messerschmidt, J. W. (1996). Managing to kill: Masculinities and the space shuttle challenger explosion. In Crime, criminal justice and masculinities (pp. 191–212). Routledge.

- Michelson, E. (2019). Decoupling: Marital violence and the struggle to divorce in China. American Journal of Sociology, 125(2), 325–381. https://doi.org/10.1086/705747

- Mouzos, J. (2002). Quality control in the National homicide monitoring program (NHMP). Citeseer.

- National Bureau of Statistics. (2021). China population census yearbook 2020. http://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/pcsj/rkpc/7rp/indexch.htm. (in Chinese).

- Overstreet, S., McNeeley, S., & Lapsey, Jr, D. S. (2021). Can victim, offender, and situational characteristics differentiate between lethal and non-lethal incidents of intimate partner violence occurring among adults? Homicide Studies, 25(3), 220–238. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088767920959402

- Pampel, F. (2011). Cohort changes in the sociodemographic determinants of gender egalitarianism. Social Forces; a Scientific Medium of Social Study and Interpretation, 89(3), 961–982. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2011.0011

- Parish, W. L., & Farrer, J. (2000). Gender and Family. In W. Tang & W. L. Parish (Eds.), Chinese urban life under reform (pp. 232–272). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Park, G. R., Park, E. J., Jun, J., & Kim, N. S. (2017). Association between intimate partner violence and mental health among Korean married women. Public Health, 152, 86–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2017.07.023

- Permanyer, I. (2013). A critical assessment of the UNDP’s gender inequality index. Feminist Economics, 19(2), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2013.769687

- Peterson, C., Kearns, M. C., McIntosh, W. L., Estefan, L. F., Nicolaidis, C., McCollister, K. E., Gordon, A., & Florence, C. (2018). Lifetime economic burden of intimate partner violence among US adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 55(4), 433–444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2018.04.049

- Pimentel, E. E. (2006). Gender ideology, household behavior, and backlash in urban China. Journal of Family Issues, 27(3), 341–365. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X05283507

- Qian, Y. (2012). Marriage squeeze for highly educated women? Gender differences in assortative marriage in urban China [Master’s thesis]. The Ohio State University.

- Qian, Y., & Li, J. (2020). Separating spheres: Cohort differences in gender attitudes about work and family in China. China Review, 20(2), 19–51.

- Raudenbush, S. W., & Bryk, A. S. (2002). Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods (Vol. 1). Sage.

- Reckdenwald, A. (2008). Examining changes in male and female intimate partner homicide over time, 1990–2000. University of Florida.

- Ridgeway, C. L., & Correll, S. J. (2004). Unpacking the gender system: A theoretical perspective on gender beliefs and social relations. Gender & Society, 18(4), 510–531. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243204265269

- Risman, B. J. (2004). Gender as a social structure: Theory wrestling with activism. Gender & Society, 18(4), 429–450. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243204265349

- Risman, B. J. (2017). 2016 southern sociological society presidential address: Are millennials cracking the gender structure? Social Currents, 4(3), 208–227. https://doi.org/10.1177/2329496517697145

- Rosenfeld, R. (1997). Changing relationships between men and women: A note on the decline in intimate partner homicide. Homicide Studies, 1(1), 72–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088767997001001006

- Russell, D. (1975). The politics of rape: The victim’s perspective. Stein and Day. ORDER FORM.

- Sardinha, L., Maheu-Giroux, M., Stöckl, H., Meyer, S. R., & García-Moreno, C. (2022). Global, regional, and national prevalence estimates of physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence against women in 2018. The Lancet, 399(10327), 803–813. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02664-7

- Schwendinger, J. R., & Schwendinger, H. (1983). Rape and inequality (pp. 178–179). Sage.

- Slote, W. H. (1998). Psychocultural dynamics within the Confucian family. In Confucianism and the family (pp. 37–51). State University of New York Press.