Abstract

This study aimed to develop a German version of the revised Pre-loss Grief Questionnaire (PG-12-R) and examine its factor structure, reliability and validity. The PG-12-R was assessed in a representative German sample (N = 2,515). Of these, 362 (14.4%) reported to have a loved one suffering from an incurable disease and 352 provided full data sets. Principal component factor analysis, scree-plot and parallel analysis were conducted. Results supported a one-factor model of PG-12-R with high internal consistency. Convergent validity was confirmed by negative correlations with psychological well-being and time since diagnosis and positive correlations with a more difficult perception of circumstances surrounding the illness and unpreparedness. The German version of the PG-12-R represents a reliable and valid measurement tool of pre-loss grief. It may be used as a screening measure for high levels of pre-loss grief to identify individuals who may need additional support.

Introduction

Grief is a natural response that occurs after a loss of a loved one and in most bereaved subsides over time (Shear et al., Citation2011). However, an approximate 3–4% of bereaved are not able to cope with the loss and develop a persistent grief reaction which is accompanied by functional impairment lasting for at least six months (Rosner et al., Citation2021; Treml et al., Citation2022). This grief response is referred to as Prolonged Grief Disorder (PGD) and is included as a diagnostic entity in the newest ICD-11, as well as in the recently published DSM-5-TR, which uses a time criterion of 12 months (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2022; WHO, Citation2018).

While grief after a loss has been examined in a variety of studies over the last years (e.g., Boelen & Kolchinska, Citation2023; Sekowski & Prigerson, Citation2021), less attention has been paid to grief before a loss. Nevertheless, research has shown that in case of terminal diseases, many relatives have time to prepare for the impeding loss of their loved one and are therefore confronted with feelings of grief even before the death (Caserta et al., Citation2013; Nielsen et al., Citation2016). This grieving period was first described as anticipatory grief by the psychiatrist Lindemann (Citation1944). During World War II Lindemann (Citation1944) noticed how wives rejected their spouses after returning from war. He interpreted this reaction as a protective response in which women already went through all the stages of grief in order to be prepared for a possible death.

Thus, Lindemann (Citation1944, p.143) described anticipatory grief as anticipatory “grief work, namely, emancipation from the bondage to the deceased, readjustment to the environment in which the deceased is missing, and the formation of new relationships.” However, literature following Lindemann’s approach described the term anticipatory grief a “misnomer,” as it suggests relatives only grieving for future losses in contrast to past or present losses and also implies “anticipation of bereavement outcome” as opposed to studies not demonstrating its protective function (Evans, Citation1994; Fulton, Citation2003; Nielsen et al., Citation2016, p. 91; Rando, Citation1988). Therefore, the conceptualization began to shift from focusing on conditions surrounding the death to the experiences of caregivers (Nielsen et al., Citation2016). Recent literature encourages the use of a different terminology, that is pre-loss grief (Evans, Citation1994; Nielsen et al., Citation2016; Treml et al., Citation2021b). Pre-loss grief is simply defined as grief symptoms occurring before the loss of a loved one in contrast to anticipatory grief work (Lindemann, Citation1944, Nielsen et al., Citation2017b). It further includes grief experiences due to present losses, e.g., the perception of changes in loved ones caused by the terminal illness (Nielsen et al., Citation2017b). Similar to PGD, pre-loss grief also appears to be distinct from other mental disorders such as depression and anxiety (Coelho et al., Citation2017; Kiely et al., Citation2008). Moreover, high levels of pre-loss grief seem to be associated with several negative health outcomes before losing a loved one, such as higher levels in anxiety, somatization and depression and lower levels in life satisfaction (Hudson et al., Citation2011; Schmidt et al., Citation2022). Similarly, pre-loss grief was found to be associated with more anxiety, depressive and prolonged grief symptoms after losing a loved one and therefore may be predictive of grief outcomes (Breen et al., Citation2020; Coelho et al., Citation2017). Moreover, high prevalence rates between 14.9% and 33% for high levels of pre-loss grief have been reported (Areia et al., Citation2019; Coelho et al., Citation2017; Hudson et al., Citation2011; Nielsen et al., Citation2017b). However, there is still no consensus in the literature on the operationalization of pre-loss grief, as different measurement scales are being used.

For the initial definition as anticipatory grief, the Anticipatory Grief Scale (Theut et al., Citation1991) was developed and used in studies. However, as anticipatory grief received much criticism, a pre-loss version of the PG-13, also called PG-12, has been frequently used (Hudson et al., Citation2011; Nielsen et al., Citation2017b; Prigerson & Maciejewski, Citation2008). The PG-13 scale was developed by Prigerson and Maciejewski (Citation2008) and was originally created for the assessment of PGD in the post-loss context. It contains 13 items that can be used for a continuous measure as well as for diagnosing PGD and has been widely used in the literature (e.g., Nielsen et al., Citation2017a). For the pre-loss version of the PG-13, most studies rephrase the questions to a pre-loss context, and remove the question regarding the time criterion (e.g., Hudson et al., Citation2011; Nielsen et al., Citation2017b). Moreover, items refer to the illness instead of the loss of the loved one (Coelho et al., Citation2017). Pre-loss grief seems similar to post-loss grief, as both “phenomena are multidimensional processes composed of similar affective, physical, cognitive, behavioral, and social features and symptoms” (Gilliland & Fleming, Citation1998, p. 543). Both grief before and after a loss necessitate adaptation to various challenges (Gilliland & Fleming, Citation1998) and have many common risk factors, e.g., female gender, poor health or lower income (Hudson et al., Citation2011; Kersting et al., Citation2011; Lenger et al., Citation2020; Tomarken et al., Citation2008). Gilliland and Fleming (Citation1998) found that various grief reactions for both pre-loss grief and post-loss grief did not differ statistically, such as the experience of emotional distress, social isolation or somatic symptoms, and therefore concluded that both are conceptually similar.

Unlike other measures of anticipatory or pre-loss grief, the pre-loss PG-13 scale (also called PG-12) is based on the distinction between post-loss normal and pathological grief reactions (Eisma, Citation2023) and thus represents an important measure for the pre-loss context. The validity of the pre-loss PG-13 scale (also called PG-12) has been previously confirmed in studies and different correlates for pre-loss grief have been found, such as gender, income, caregiver burden or amount of hours of daily care (Coelho et al., Citation2017; Hudson et al., Citation2011; Tomarken et al., Citation2008; Treml et al., Citation2021b). Moreover, pre-loss grief and preparedness for death appear to be negatively associated, as preparedness for death represents a protective factor for adjustment after a loss in contrast to pre-loss grief (Nielsen et al., Citation2016, Citation2017b; Treml et al., Citation2021b).

However, because the PG-13 items do not correspond to the current PGD criteria, a revised version was developed by Prigerson and colleagues to capture the current DSM-5-TR criteria (Prigerson et al., Citation2021). The revised version has been shown to be a reliable and valid measurement tool for people suffering from PGD (Prigerson et al., Citation2021). However, since this questionnaire has not yet been applied to the pre-loss context, previous studies on pre-loss grief are based on the outdated criteria of PGD. Moreover, previous studies often employ convenience samples, limiting generalizability (see Treml et al., Citation2021b).

Early recognition of high levels of pre-loss grief could help identify individuals who need additional support. Therefore, a valid and reliable measurement tools for the assessment of pre-loss grief is necessary. This might help prevent the potential development of PGD. Additionally, in order to recognize cultural differences in the perception of pre-loss grief, it is important to use validated translations of the PG-12-R. Therefore, this study aimed to provide a pre-loss version of the German translation of the PG-12-R, and examine its psychometric criteria, with regard to internal consistency, factor structure and validity. In contrast to previous measurements of pre-loss grief, the PG-12-R includes the current PGD criteria, applied to the pre-loss context.

Given that the PG-12-R represents a new scale, which has not been tested yet, an exploratory approach was chosen to examine the number of underlying components (see Prigerson et al., Citation2021). Regarding convergent validity, we expected the PG-12-R to be positively associated with difficult aspects surrounding the illness and negatively associated with psychological well-being and preparedness for death. In addition, we investigated whether the time since diagnosis had an impact on pre-loss grief. While this association has not been previously investigated, a negative association was found between depressive and anxious avoidance in PGD and time since loss (Treml et al., Citation2021a). In the case of pre-loss grief, a longer period of time since the diagnosis may provide more time to prepare for the impending loss. Higher preparedness was in turn found to be negatively associated with less pre-loss grief (Treml et al., Citation2021b). Therefore, a negative association between time since diagnosis and pre-loss grief was expected.

Materials and methods

Procedure

Data was collected in a representative sample of the German population between December 2022 and March 2023 by a German social research company (USUMA, Berlin, Germany). A random sampling technique was employed with three steps: a) a random selection of 258 geographic locations, reflecting the various regions of Germany, b) random selection of households in the previous selected locations (using a random-route method) and c) random selection of a single person from the previously selected household (using the Kish-selection grid method). For inclusion, participants had to be at least 16 years, be fluent in German and provide written informed consent (for minors, an additional written informed consent from parents had to be provided).

For recruitment, a total of 6,085 individuals were approached by the doorstep by 191 trained interviewers. In case the individual was not home, interviewers tried up to three additional times to reach the selected individual. Upon contact, oral and written study information were presented. Sociodemographic variables were surveyed face-to-face, which was followed by completion of self-report scales. The study was conducted according to the declaration of Helsinki and approved by the ethics committee of the University of Leipzig (AZ:355/22-ek, 11.10.2022).

Participants

A total of 6,085 individuals were selected, of which 2,515 (41.3%) participants were included in the study. Reasons for selected individuals/households not responding were: 1) interviewers were not able to reach selected households (n = 804, 13.2%), 2) selected households did not want to participate (n = 1,481, 24.3%), 3) interviewers were not able to reach selected individuals (n = 78, 1.3%), 4) selected individuals did not want to participate (n = 1,037, 17.0%) and 5) selected individuals were ill and unable to follow the interview or interview not evaluable due to other reasons (n = 170, 2.8%). Of the 2,515 participants, 362 (14.4%) reported having a loved one with an incurable, terminal illness. For the analysis only participants with complete data in the PG-12-R were included. Overall, thirteen participants were excluded due to missing values, leading to a final sample of n = 352.

Measures

Sociodemographic characteristics included age, gender, education level, income, employment status and religion. Moreover, characteristics about the loved one and his/her illness were obtained with self-constructed questions (e.g., type of illness, age, time since diagnosis, degree of kinship).

Pre-loss grief (PG-12-R)

The pre-loss version PG-12-R was based on the PG-13-R, which was developed to measure PGD according to the current DSM-5-TR criteria (Prigerson et al., Citation2021). The original questionnaire contains 13 items, of which 10 can be rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all; 5 = overwhelmingly), two questions are dichotomous (1 = yes; 2 = no) and one questions allows to provide details about the months since loss. The questionnaire was rephrased to a pre-loss context, so that questions focused on the illness rather than the loss of the person. Therefore, the first question asks if participants have a loved one suffering from a terminal illness instead of asking if participants have lost a loved one (1 = yes, 2 = no). Similarly, the second question asks about the time since diagnosis instead of time since loss. The following ten questions include cognitive, behavioral, and emotional symptoms, such as having trouble believing that the loved one is really ill. The answers can be calculated into a sum score. A higher sum score indicates higher pre-loss grief. The last question refers to functional impairment (1 = yes, 2 = no). The translation was based on a German translation of the PG-13-R (Rosner, Citation2021) and rephrased to the pre-loss context by two psychologists (VS and JT) independently. Both versions were examined for differences and combined into a final version by agreement of both psychologists. The German Version of the PG-12-R can be found in the Supplementary Material.

Psychological well-being

Psychological well-being was assessed using the WHO-5 well-being index (World Health Organization, Citation1998). This questionnaire has been translated to various languages and found to be a valid screening measurement for depression (Topp et al., Citation2015). It contains 5 questions which can be answered on a 6-point Likert scale (0 = at no time, 5 = all of the time). A higher sum score indicates a higher psychological well-being. Internal consistency for the scale was excellent (α = .94) in this study.

Perception of circumstances surrounding the illness

Perception of circumstances surrounding the illness were measured using the Perception of circumstances surrounding death scale (Barry et al., Citation2002). The scale was rephrased to a pre-loss context and reframed to the focus of the illness rather than death by two independent reviewers (VS and JT). Both versions were examined for differences and combined into an agreed final version (see Supplementary Material). The scale contains 4 items on a 7-point Likert scale with varying response options. The scale assesses how peaceful or violent the illness is perceived (1 = peaceful, 4 = moderate, 7 = violent), how much the loved one is currently suffering from the illness (1 = minimally, 4 = moderately, 7 = extremely), the perceived longevity of the illness (1 = very short, 4 = moderate, 7 = very long) and the preparedness for the imminent death (1 = well prepared, 4 = somewhat prepared, 7 = totally unprepared). Higher scores indicate more difficult circumstances surrounding the illness and less preparedness for death.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences, version 29 (IBM®SPSS®). The significance level was set to α = .05.

For preliminary analyses, items were analyzed for mean (SD) and corrected item-total correlation. According to Cristobal et al. (Citation2007), the minimum value for item-total correlations was set at.3. The normality of items was investigated through the skewness and kurtosis values, with West et al. (Citation1995) describing values < 2 for skewness and < 7 for kurtosis as suitable.

To investigate reliability, following indices were used: Cronbach’s α, mean inter-item correlation (MIIC), and McDonald’s omega (ω). For good internal reliability, Cronbach’s α and McDonald’s omega (ω) ≥ .80 is required (Feißt et al., Citation2019). Moreover, a MIIC between.15 and.50 has been suggested as suitable (Ashouri et al., Citation2023; Mohsenabadi et al., Citation2020).

For construct validity, a principal component analysis (factor analysis) was performed. As mentioned above, since the PG-12-R represents a new scale and construct validity for this scale has not been tested yet, an exploratory approach instead of a CFA was applied (Kokou‐Kpolou et al., Citation2022; e.g., Prigerson et al., Citation2021). Similarly to previous studies, an oblique rotation was performed (Kokou‐Kpolou et al., Citation2022; Pohlkamp et al., Citation2018). For the assessment of the underlying components, several criteria were considered: (a) eigenvalues ≥ 1 (Guttman, Citation1954; Kaiser, Citation1960) (b) a scree-plot of eigenvalues (Fabrigar & Wegener, Citation2012) and (c) the results of a parallel analysis (Horn, Citation1965).

To investigate convergent validity, associations between the PG-12-R and psychological well-being (WHO-5), perception of circumstances surrounding the illness, preparedness for death and time since diagnosis were investigated using Pearson’s r. We predicted that the PG-12-R would be negatively associated with psychological well-being and time since diagnosis and positively associated with more difficult circumstances surrounding the illness and more unpreparedness.

Results

Participant characteristics and preliminary analysis

Participants were aged between 16 and 93 years (M = 56.01, SD = 16.55). About 60.2% were women and 39.8% were men. Most participants had a German citizenship (97.7%). Demographic characteristics can be found in the Supplementary Material.

Participants’ loved ones were aged between 8 and 95 years (M = 68.53, SD = 14.53). Regarding the terminal illness, participants reported their loved one to have cancer (59.1%), dementia/Alzheimer’s disease (18.8%), heart disease (11.4%), Parkinson’s disease (9.9%), pulmonary disease (5.4%), ALS or other motor neuron disease (.9%) or other (3.7%), with participants being able to indicate more than one illness. Of all loved ones’, 59.6% were women, 40.1% men and 0.3% diverse gender. Characteristics of participants’ loved ones can be found in the Supplementary Material.

Preliminary analyses

Item characteristics of the PG-12-R can be found in . Item means ranged from 1.84 (Item 9) to 4.01 (Item 1). Eight items were positively skewed and two items (1, 6) negatively skewed, while skewness ranged from −1.15 to 1.08. Similarly, eight items showed a negative kurtosis and two items a positive kurtosis (1, 6). Kurtosis ranged from −1.18 to.65. Corrected item-total-correlations were between.45 and.81. All items had suitable skewness and kurtosis and met the minimum value for item-total correlations.

Table 1. Psychometric properties and factor loadings of the PG-12-R.

Reliability

The internal consistency of the PG-12-R was excellent with Cronbach’s α = .90 and ω=.90. None of the individual items had a negative effect on the consistency of the overall scale (see ). The mean inter-item correlation was suitable with r = .49. The range for the individual inter-item correlations was r = .19 to.75, with the highest correlation between Items 7 and 8 (r = .75) and the lowest correlation between Items 1 and 9 (r = .19).

Factor analysis

To evaluate the factor structure, a factor analysis (principal component analysis) with an oblique rotation was performed. The analysis yielded excellent sampling adequacy (Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure = .916, Field, Citation2013) and a significant Bartlett’s test of Sphericity (p < .001), indicating suitability of data for a factor analysis.

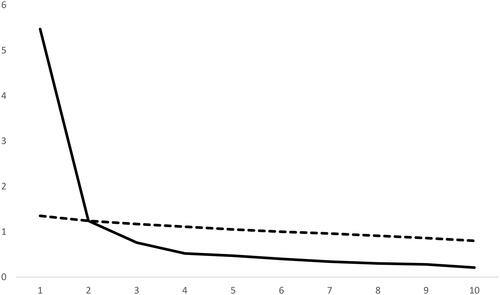

The first assessment criteria (examination of Kaiser’s criteria) yielded two factors with eigenvalues above one (5.474 and 1.243). However, the scree-plot favored a one-factor model. Moreover, a parallel analysis also yielded a one-factor solution, as the 95% Percentile Random Data Eigenvalue (1.245) was slightly above the eigenvalue of the principal component analysis for the second factor (1.243, see ).

Figure 1. Comparison between eigenvalues from principal component analysis of PG-12-R and eigenvalues from parallel analysis from random data (median of 1000 replications).

Therefore, a model with one factor was retained which accounted for 54.49% of the total variance. Item loadings on the factor ranged between.51 and.88, with the highest loading for Item 8 (emotional numbness or detachment from others since loved one’s illness) and the lowest loading for Item 1 (longing or yearning for the loved one to become healthy, see ). Thus, results yielded a one-factor solution for measuring pre-loss grief.

Convergent validity

PG-12-R was significantly positively correlated with a more difficult perception of circumstances surrounding the illness (perception of illness as more violent, perception of loved one suffering from illness and perceived longevity of illness) and more unpreparedness for the death. Moreover, PG-12-R was negatively correlated with psychological well-being and time since diagnosis (see ). The highest correlation was found between psychological well-being and PG-12-R with r = −.487 and the lowest correlation between time since diagnosis and PG-12-R with r = −.106.

Table 2. Bivariate Pearson’s correlations between PG-12-R symptom score (sum of 10 items) and related constructs.

Discussion

The aim of the study was to provide a German version of the PG-12-R and examine its factor structure, reliability and validity in a representative German sample. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the factor structure of the PG-12-R, which represents the pre-loss version of the newest PG-13-R scale (Prigerson et al., Citation2021).

Results yielded a one-factor solution for the PG-12-R scale. This is in line with previous studies regarding the PG-13-R scale for assessment of post-loss PGD (Ashouri et al., Citation2023; Prigerson et al., Citation2021), as well as for PG-12 (pre-loss version of the original PG-13 scale, Coelho et al., Citation2017; Park et al., Citation2022; Prigerson & Maciejewski, Citation2008). Therefore, the scale seems to represent a unidimensional construct for pre-loss grief.

The first item, referring to the longing or yearning for the loved one to become healthy, had the lowest factor loading on the unidimensional construct. Since only participants who had a loved one with an incurable disease were included, this item may be the “least relevant” for the experience of pre-loss grief in this sample (Park et al., Citation2022, p. 7), as the participants did not expect their loved ones to become healthy again due to the terminal nature of the disease. This is in line with Park et al. (Citation2022), who also found the weakest loading for the first item in caregivers of people with incurable moderate or severe stages of dementia. The highest factor loading in our study was found for item eight, referring to the feeling of emotional numbness or detachment from others since loved one’s illness. This aligns with Park et al. (Citation2022), who found emotional numbness to be associated with caregiver’s pre-loss grief, since many caregivers often feel emotionally numb due to stress and the caregiving burden.

Moreover, results showed an excellent internal consistency of the scale, which is also consistent with previous studies on PG-13-R and PG-12 (Ashouri et al., Citation2023; Coelho et al., Citation2017; Park et al., Citation2022; Prigerson et al., Citation2021). While eight items were positively skewed and two items negatively skewed, skewness and kurtosis were within the acceptable range. Similarly, item-total correlation were high and ranged between.45 and.81.

Regarding convergent validity, PG-12-R showed a positive correlation with more difficult circumstances surrounding the death. This is in line with our expectations and previous studies on grief after a loss, which found that individuals with probable PGD perceived the death of a loved one as more violent than individuals not meeting the criteria for PGD (Treml et al., Citation2022). Therefore, results extend previous findings indicating that even before a loss, higher levels of pre-loss grief seem to be associated with a more violent perception of the illness. Moreover, higher levels of suffering by loved ones’ and perceived longevity of the illness also seem to be correlated with higher levels of pre-loss grief. Therefore, results show that higher levels of relatives’ grief may be accompanied with not only perceived circumstances surrounding the death, but also surrounding the illness before a loss. Additionally, pre-loss grief and preparedness for death showed an inverse correlation, which aligns with our expectations and previous studies (Nielsen et al., Citation2017b). Moreover, previous studies have implied that high levels of pre-loss grief may be hindering and high levels of preparedness for death may be helpful for a better adjustment after a loss (Nielsen et al., Citation2016; Treml et al., Citation2021b).

Furthermore, time since diagnosis and pre-loss grief were negatively related. However, the correlation was small, indicating that pre-loss grief only slightly diminished over time. This is consistent with previous studies on PGD after a loss (Treml et al., Citation2021a), suggesting that not only PGD, but also pre-loss grief may be stable over time.

Lastly, PG-12-R and psychological well-being were negatively related. This is consistent with previous research finding pre-loss grief to be related to different outcomes of poor psychological health (Schmidt et al., Citation2022; Treml et al., Citation2021b). Therefore, results further confirm the validity of the PG-12-R.

The PG-12-R conceptualizes pre-loss grief as the presence of different grief symptoms before loss, including grief reactions to various losses experienced during a terminal illness of a loved one (see also Nielsen et al., Citation2017b). Therefore, pre-loss grief is centered on the present, describing grief reactions experienced related to the ongoing terminal illness of a loved one. This is in line with previous literature, describing one possible conceptualization of grief before loss as “illness-related grief” (Singer et al., Citation2022, p. 10). However, results have to be seen in light of some limitations. A major limitation of this study is the cross-sectional assessment, therefore not providing retest-reliability and not allowing for causal interpretations. Moreover, the sample was relatively small with n = 352. Nevertheless, the study included a representative German sample and therefore extends previous findings on pre-loss grief, often including convenience samples (e.g., Areia et al., Citation2019; Breen et al., Citation2020; Coelho et al., Citation2017). Future studies should investigate pre-loss grief in in longitudinal designs and seek to include larger samples. Moreover, future studies performing confirmatory factor analysis using a larger sample size are necessary.

Conclusions

PG-12-R represents a reliable and valid scale to measure pre-loss grief before losing a loved one and may therefore be used in further studies. While PGD is a well-studied disorder, less attention is paid to pre-loss grief. Nevertheless, pre-loss grief should be considered in studies and in patient care, as it seems to be associated with poor psychological health (Nielsen et al., Citation2016; Treml et al., Citation2021b). The PG-12-R may further be used as a screening measure for high levels of pre-loss grief to identify individuals who may need additional support. Further studies are needed to better understand the trajectory of pre-loss grief over time.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (33.8 KB)Acknowledgements

None.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Declaration of interest statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [VS], upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). (Ed.). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5-TR. (5th ed., text revision). American Psychiatric Association Publishing.

- Areia, N. P., Fonseca, G., Major, S., & Relvas, A. P. (2019). Psychological morbidity in family caregivers of people living with terminal cancer: Prevalence and predictors. Palliative & Supportive Care, 17(3), 286–293. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951518000044

- Ashouri, A., Yousefi, S., & Prigerson, H. G. (2023). Psychometric properties of the PG-13-R scale to assess prolonged grief disorder among bereaved Iranian adults. Palliative & Supportive Care, 22(1), 174–181. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951523000202

- Barry, L. C., Kasl, S. V., & Prigerson, H. G. (2002). Psychiatric disorders among bereaved persons: The role of perceived circumstances of death and preparedness for death. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 10(4), 447–457. https://doi.org/10.1097/00019442-200207000-00011

- Boelen, P. A., & Kolchinska, Y. (2023). Prolonged grief disorder: Nature, risk-factors, assessment, and cognitive-behavioural treatment. Psychosomatic Medicine and General Practice, 7(2), e0702375. https://doi.org/10.26766/pmgp.v7i2.375

- Breen, L. J., Aoun, S. M., O’Connor, M., Johnson, A. R., & Howting, D. (2020). Effect of caregiving at end of life on grief, quality of life and general health: A prospective, longitudinal, comparative study. Palliative Medicine, 34(1), 145–154. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216319880766

- Caserta, M. S., Utz, R. L., & Lund, D. A. (2013). Spousal bereavement following cancer death. Illness, Crises, and Loss, 21(3), 185–202. https://doi.org/10.2190/IL.21.3.b

- Coelho, A., Silva, C., & Barbosa, A. (2017). Portuguese validation of the Prolonged Grief Disorder Questionnaire–Predeath (PG–12): Psychometric properties and correlates. Palliative & Supportive Care, 15(5), 544–553. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951516001000

- Cristobal, E., Flavián, C., & Guinalíu, M. (2007). Perceived e‐service quality (PeSQ): Measurement validation and effects on consumer satisfaction and web site loyalty. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal, 17(3), 317–340. https://doi.org/10.1108/09604520710744326

- Eisma, M. C. (2023). Prolonged grief disorder in ICD-11 and DSM-5-TR: Challenges and controversies. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 57(7), 944–951. https://doi.org/10.1177/00048674231154206

- Evans, A. J. (1994). Anticipatory grief: A theoretical challenge. Palliative Medicine, 8(2), 159–165. https://doi.org/10.1177/026921639400800211

- Fabrigar, L. R., & Wegener, D. T. (2012). Exploratory factor analysis. Oxford University Press.

- Feißt, M., Hennigs, A., Heil, J., Moosbrugger, H., Kelava, A., Stolpner, I., Kieser, M., & Rauch, G. (2019). Refining scores based on patient reported outcomes – Statistical and medical perspectives. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 19(1), 167. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-019-0806-9

- Field, A. P. (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics: And sex and drugs and rock ‘n’roll. Sage.

- Fulton, R. (2003). Anticipatory mourning: A critique of the concept. Mortality, 8(4), 342–351. https://doi.org/10.080/13576270310001613392

- Gilliland, G., & Fleming, S. (1998). A comparison of spousal anticipatory grief and conventional grief. Death Studies, 22(6), 541–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/074811898201399

- Guttman, L. (1954). Some necessary conditions for common-factor analysis. Psychometrika, 19(2), 149–161. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02289162

- Horn, J. L. (1965). A rationale and test for the number of factors in factor analysis. Psychometrika, 30(2), 179–185. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02289447

- Hudson, P. L., Thomas, K., Trauer, T., Remedios, C., & Clarke, D. (2011). Psychological and social profile of family caregivers on commencement of palliative care. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 41(3), 522–534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.05.006

- Kaiser, H. F. (1960). The application of electronic computers to factor analysis. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20(1), 141–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316446002000116

- Kersting, A., Brähler, E., Glaesmer, H., & Wagner, B. (2011). Prevalence of complicated grief in a representative population-based sample. Journal of Affective Disorders, 131(1-3), 339–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2010.11.032

- Kiely, D. K., Prigerson, H. G., & Mitchell, S. L. (2008). Health care proxy grief symptoms before the death of nursing home residents with advanced dementia. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 16(8), 664–673. https://doi.org/10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181784143

- Kokou‐Kpolou, C. K., Lenferink, L. I. M., Brunnet, A. E., Park, S., Megalakaki, O., Boelen, P., & Cénat, J. M. (2022). The ICD‐11 and DSM‐5‐TR prolonged grief criteria: Validation of the Traumatic Grief Inventory‐Self Report Plus using exploratory factor analysis and item response theory. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 29(6), 1950–1962. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2765

- Lenger, M. K., Neergaard, M. A., Guldin, M.-B., & Nielsen, M. K. (2020). Poor physical and mental health predicts prolonged grief disorder: A prospective, population-based cohort study on caregivers of patients at the end of life. Palliative Medicine, 34(10), 1416–1424. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216320948007

- Lindemann, E. (1944). Symptomatology and management of acute grief. American Journal of Psychiatry, 101(2), 141–148. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.101.2.141

- Mohsenabadi, H., Shabani, M. J., Assarian, F., & Zanjani, Z. (2020). Psychometric properties of the child and adolescent mindfulness measure: a psychological measure of mindfulness in youth. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, 14(1), e79986. https://doi.org/10.5812/ijpbs.79986

- Nielsen, M. K., Neergaard, M. A., Jensen, A. B., Bro, F., & Guldin, M.-B. (2016). Do we need to change our understanding of anticipatory grief in caregivers? A systematic review of caregiver studies during end-of-life caregiving and bereavement. Clinical Psychology Review, 44, 75–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.01.002

- Nielsen, M. K., Neergaard, M. A., Jensen, A. B., Vedsted, P., Bro, F., & Guldin, M.-B. (2017a). Predictors of complicated grief and depression in bereaved caregivers: A nationwide prospective cohort study. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 53(3), 540–550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.09.013

- Nielsen, M. K., Neergaard, M. A., Jensen, A. B., Vedsted, P., Bro, F., & Guldin, M.-B. (2017b). Preloss grief in family caregivers during end-of-life cancer care: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Psycho-oncology, 26(12), 2048–2056. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4416

- Park, J., Levine, H., & Galvin, J. E. (2022). Factor structure of Pre‐Loss Grief‐12 in caregivers of people living with dementia. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions, 8(1), e12322. https://doi.org/10.1002/trc2.12322

- Pohlkamp, L., Kreicbergs, U., Prigerson, H. G., & Sveen, J. (2018). Psychometric properties of the Prolonged Grief Disorder-13 (PG-13) in bereaved Swedish parents. Psychiatry Research, 267, 560–565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.06.004

- Prigerson, H. G., & Maciejewski, P. (2008). Prolonged grief disorder (PG-13) scale. Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

- Prigerson, H. G., Boelen, P. A., Xu, J., Smith, K. V., & Maciejewski, P. K. (2021). Validation of the new DSM‐5‐TR criteria for prolonged grief disorder and the PG‐13‐ Revised (PG‐13‐R) scale. World Psychiatry, 20(1), 96–106. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20823

- Rando, T. A. (1988). Anticipatory grief: The term is a misnomer but the phenomenon exists. Journal of Palliative Care, 4(1-2), 70–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/0825859788004001-223

- Rosner, R. (2021). PG-13-R (German). Retrieved May 19, 2023, from https://endoflife.weill.cornell.edu/sites/default/files/file_uploads/pg13-r-german.pdf

- Rosner, R., Comtesse, H., Vogel, A., & Doering, B. K. (2021). Prevalence of prolonged grief disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 287, 301–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.03.058

- Schmidt, V., Kaiser, J., Treml, J., & Kersting, A. (2022). The relationship between pre-loss grief, preparedness and psychological health outcomes in relatives of people with cancer. Omega, 302228221142675. https://doi.org/10.1177/00302228221142675

- Sekowski, M., & Prigerson, H. G. (2021). Associations between interpersonal dependency and severity of prolonged grief disorder symptoms in bereaved surviving family members. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 108, 152242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2021.152242

- Shear, M. K., Simon, N., Wall, M., Zisook, S., Neimeyer, R., Duan, N., Reynolds, C., Lebowitz, B., Sung, S., Ghesquiere, A., Gorscak, B., Clayton, P., Ito, M., Nakajima, S., Konishi, T., Melhem, N., Meert, K., Schiff, M., O’Connor, M.-F., … Keshaviah, A. (2011). Complicated grief and related bereavement issues for DSM-5. Depression and Anxiety, 28(2), 103–117. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20780

- Singer, J., Roberts, K. E., McLean, E., Fadalla, C., Coats, T., Rogers, M., Wilson, M. K., Godwin, K., & Lichtenthal, W. G. (2022). An examination and proposed definitions of family members’ grief prior to the death of individuals with a life-limiting illness: A systematic review. Palliative Medicine, 36(4), 581–608. https://doi.org/10.1177/02692163221074540

- Theut, S. K., Jordan, L., Ross, L. A., & Deutsch, S. I. (1991). Caregiver’s anticipatory grief in dementia: A pilot study. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 33(2), 113–118. https://doi.org/10.2190/4KYG-J2E1-5KEM-LEBA

- Tomarken, A., Holland, J., Schachter, S., Vanderwerker, L., Zuckerman, E., Nelson, C., Coups, E., Ramirez, P. M., & Prigerson, H. G. (2008). Factors of complicated grief pre-death in caregivers of cancer patients. Psycho-oncology, 17(2), 105–111. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1188

- Topp, C. W., Østergaard, S. D., Søndergaard, S., & Bech, P. (2015). The WHO-5 well-being index: A systematic review of the literature. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 84(3), 167–176. https://doi.org/10.1159/000376585

- Treml, J., Brähler, E., & Kersting, A. (2022). Prevalence, factor structure and correlates of DSM-5-tr criteria for prolonged grief disorder. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 880380. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.880380

- Treml, J., Nagl, M., Braehler, E., Boelen, P. A., & Kersting, A. (2021a). Psychometric properties of the German version of the Depressive and Anxious Avoidance in Prolonged Grief Questionnaire (DAAPGQ). PloS One, 16(8), e0254959. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0254959

- Treml, J., Schmidt, V., Nagl, M., & Kersting, A. (2021b). Pre-loss grief and preparedness for death among caregivers of terminally ill cancer patients: A systematic review. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 284, 114240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114240

- West, S. G., Finch, J. F., & Curran, P. J. (1995). Structural equation models with nonnormal variables: Problems and remedies. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications (pp. 56–75). Sage Publications, Inc.

- WHO. (2018). ICD-11—International classification of diseases for mortality and morbidity statistics (11th Revision). https://icd.who.int/en

- World Health Organization. (1998). Wellbeing measures in primary health care/the DEPCARE project: Report on a WHO meeting. https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0016/130750/E60246.pdf