ABSTRACT

As a composer-performer, Cat Hope has collaborated with Éliane Radigue in the creation of three new works: 2015's OCCAM HEXA II, co-composed with Carol Robinson and commissioned by Decibel new music ensemble, 2018's OCCAM XXIV for solo alto flute, and 2019's OCCAM RIVER XXIV for flute and cello. In this article, Hope traces the genesis of these works and her experience bringing these compositions to life via a shared composer-performers' circle: friendship networks and ways of being together that Hope argues are key to the success of Radigue's acoustic work. Drawing from meetings, discussions, and workshop sessions with Radigue, the experience of the evolving performance process and consultations with other Radigue performers, Hope outlines her perspective on how these works come together, link to each other, and contribute to the broader community of composer-performers.

Personal Background

I am an Australia-based composer, bassist, flute player and artistic director of the new music ensemble Decibel. My own compositions often feature electronics and pay close attention to low frequency sounds. My electric bass guitar playing is noisy, improvisatory and laden with effects. As a classically trained flute player, I focus primarily on new repertoire for bass or alto flute. These practices are all tied together through an interest in the extremes of sound: very loud, soft, detailed, sparse, long or short, completely open or tightly composed. Based in Australia, I am perhaps furthest away from Radigue’s Parisian locale and her circle of performers. Nonetheless, this article draws on in-person conversations I have had with Radigue, as well as discussions with other composer-performers that share working relationships with her, to show how these networks are an essential part of Radigue’s compositional process (Yip Citation2015). It builds on the musicological scholarship by authors who have not performed her works: such as Luke Nickel (Citation2020) and William Dougherty (Citation2021). I will also explore how these networks inform which performers are able to perform this music and when. After presenting some background on each of the pieces that I have performed, I will explain how they fit together.

First Meetings

I naively wrote Radigue a letter in early 2014 requesting a work for my ensemble Decibel. I mentioned that I would be in Paris later that year, and Radigue promptly invited me to meet with her. Shortly after that exchange, I met French composer and electric bassist Kasper T. Toeplitz after a concert in Sydney. We were excited to meet each other: two electric bass-playing composers interested in electronics, noise, drones and the lowest of sounds. He gave me a compact disc recording of his performance of the work he had commissioned from Radigue, Elemental II (2004) for electric bass and computer sounds (R.o.s.a 01; Citation2005). I knew little about her most recent acoustic music at this time, and this release made me think that something with electronics and acoustic instruments might be realisable.

Before my meeting with Radigue, I also met composer-performer Carol Robinson, who had performed many of Radigue’s acoustic works. We met some weeks before I arrived in Paris, where Robinson vouched for me and my proposal to Radigue. We met in a café before heading to Radigue’s home—where she clarified some important information I had been missing—that Radigue did not notate her pieces for performers, that she worked very directly with them in the evolution of a composition, and that she did not write for electronics anymore. A work would not be complete at the end of the composition process, but would time need to evolve, allowing the development and control of the performance techniques required for the work. Then, perhaps, after several performances, the work would be complete. We could then share it with other performers who may like to play it themselves. Radigue could not travel to Australia to undertake this process due to health concerns at that time, and it was also prohibitive to bring Decibel—a group of six Australian artists—to Paris and work on a new piece for several weeks, a few hours each week. Thus, Radigue suggested Robinson co-compose the piece, which would involve her travelling to Australia to work with Decibel using Radigue’s methods, but on a composition of her own design (Hope and Robinson Citation2017).

I brought my bass flute to Radigue’s apartment, and performed a twenty-minute improvised solo for Radigue and Robinson. Again naively, I tried to capture something of the atmosphere of her electronic music, that I had listened to extensively. I found the well-lit apartment—surrounded by art works, large house plants and various artefacts of Radigue’s career and friendships—to be welcoming and warm. After my performance, we shared tea and biscuits, chatting about music and common friends. We discussed Radigue’s compositional process and how this co-composed piece with Robinson would come about. After some online preparation with each player, Robinson would come to Australia to develop the work, first with solos, then duos and trios, using Radigue’s methods over two weeks. Afterward, Radigue and Robinson requested that I take a few days to consider their proposal, and in exchange for recordings of my work, Radigue gifted me a book about her in French (Girard Citation2013), and a copy of the newly released Naldjorlak series (Robinson, Curtis, and Martinez Citation2013). She inscribed the book with a personal message: ‘For this beautiful meeting. For all the understanding we have. For everything we’ll have done. For … For … For … ’

From this meeting and materials, I gained a much better understanding of her circle and the sound that seemed to bind the performers together: an aesthetic somewhere between acoustic and electronic timbres, between composed and improvised conceptions, between breath, wood, metal and movement. The combination of the conversations that day, the recording and book, helped me to realise the inadequacy of musical notation for this music. Regardless of its complexity, notation could neither prescribe nor describe these sounds, and it would not have the capacity to illustrate the interpersonal relationships that are so central to the success of these works.

Some days later, we met again, and we confirmed Robinson’s role of stewarding Radigue’s working method and sonic sensibilities (Dougherty Citation2021, 103). The work was given a title, OCCAM HEXA II (Citation2015).

Pulling Threads into a Circle

In our conversations that followed this first meeting, it became clear how our networks had so many common threads, including and beyond those that had led us together. For example, when touring with Decibel in Australia in 2010, I met Lionel Marchetti who, unbeknownst to me at the time, was diffusor of Radigue’s electronic works. Decibel commissioned Marchetti and later co-composed music together (Decibel Citation2018). I had worked with another Radigue collaborator, such as in a concert with composer-tubist Robin Hayward. I later found that one of the Shiiin label team, who releases Radigue’s recent work, was involved with the French label that released my early pop music, Telescopic, back in the late 1990s. I met cellist Deborah Walker at a concert in Melbourne, instrument inventor Laetetia Sonami at a conference in Paris, Cat Lamb on a programme in Berlin. The conversations with composer performers Robinson, Toeplitz and Hélène Brechand were the most insightful, however all these connections have provided important touchstones for understanding the works, thinking about concert presentations and future works, contributing to a growing wreath-like circle.

OCCAM HEXA II for Flute, Clarinet, Viola, Cello and Percussion (2015)

Developing OCCAM HEXA II (Citation2015) was a wonderful introduction into Radigue’s sound world, because it came about through another composer-performer’s experience of it. As a composer and clarinettist, Robinson had particular insights into the way Radigue communicated her ideas to performers, and how they become engaged in the evolution of the piece. I think the co-compositional process that began with this work is an extension of Radigue’s desire for pieces to be passed on between performers.

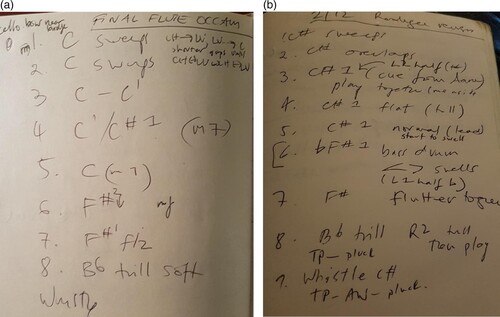

Devising and learning this work was an all-consuming, extraordinary experience. We travelled with Decibel to the Indian Ocean on Australia’s west coast near Perth where we lived, and Robinson asked us to remember particular qualities of this site that we would refer to as an indicator for the energy of our sound, its modulations and how we come together as a whole. Bodies of water are the usual structural and spiritual starting point for many of Radigue’s recent instrumental collaborations. There would be no score for the work, just some notes we took about fingerings we developed and what to listen for as an indication for a change to the next sound. The concept—building and weaving sounds and dynamics that start from a point of instability—seemed so deceptively simple, but required incredible focus, preparation and control by the performers.Footnote1 After the premiere in Perth, we recorded the work in Hamburg in 2017, under Robinson’s supervision. Further alterations were made at this session, and my notes from the original work and the recording session are shown in (a and b). These notes are indicative, reminding me of my steps through a structure signalled by other ensemble members. The fingerings for these notes were now memorised and not noted on this copy. We found that recording this music was a difficult process, as the resonance afforded by a large space caused other sounds to intrude into the quiet parts of the piece. We later performed the work in Melbourne in 2019, in a programme featuring some diffusions of Radigue’s electronic works by Lionel Marchetti. This programme highlighted the connections between Radigue’s electronic and acoustic music for the audience, a connection that was so key to my own understanding of her music. Her acoustic compositions are completely shaped by her experience with electronics. They are shaped by the process of listening, searching, and refining the sounds that emerge when composing with synthesisers. Radigue often comments that working with acoustic instruments has resulted in the formation of sounds she had always been seeking in her electronic music. Her composition process, and process of performing these compositions, is a listening-centric one.

Figure 1. (a) Original notes for the flute part of OCCAM HEXA II in Citation2015. (b) The revised notes made at the recording session in Hamburg in 2017.

OCCAM XXIV for Alto Flute (2018)

In 2018, I returned to Radigue for a series of meetings to develop OCCAM XXIV, her first work for solo flute. I brought along two photographs of important bodies of water, both places that I felt a strong connection to, hoping Radigue would help me choose. One was of the estuary in Perth, the other of a river near Catania, Sicily. I had lived for considerable periods in both cities and the longing for one whilst in the other had created an unsettled feeling in my life, where my sense of home was split. To my surprise, Radigue was interested in exploring a work with both images, almost as a way to help me reconcile this division. We assigned an instrument to each place, alto and bass flute. I had brought both with me to our meeting, again expecting to make a choice. This time, I was learning to play Radigue’s music not only from previous experience performing OCCAM HEXA II, but also discussions with performers of her music that I had met since. OCCAM XXIV unfolded as follows:

When I met Radigue, we took some moments together to slow down. The pace in her apartment is different, it is a space to breathe, relax, and make space in one’s mind for something new. We chatted for a while, just like at our first meeting a few years earlier. After briefly discussing the images and what they meant to me, we progressed to sound. Radigue sat opposite me on her large white sofa, with a notebook, pencil and timepiece, listening very carefully with her eyes closed. I stood on the other side of the low coffee table between us.

I presented a sequence of three or four different sound ideas in a descending pitch sequence on the alto flute, concluding on a note that can be continued on the bass flute. Thereafter I picked up the bass and continued the trajectory. My proposition ended with variations around the lowest possible pitches of the bass flute, extended further by having each flute’s head joint pulled out as far as it can go making ‘hollow tubes with holes, assembled in different lengths’ (Radigue in Eckhardt Citation2019, 9). That last sound, eventually, somehow, fades to nothing, like ‘clouds in a blue summer sky’ (Eckhardt Citation2019, 17).

This approach drew from my own compositional interests. All my works feature some element of low frequency—either literally, by writing for low instruments and registers, or metaphorically—by applying downward motion in various ways (Hope Citation2023). Radigue permitted this direction, and I would not be surprised if other collaborators contributed their own compositional ideas. She made notes and provided extensive commentary on my sequence of sounds, designing a shape and structure for the work as we went. She reflected on what she liked and disliked in my playing. The work is built of four to seven-minute segments. Each time the piece got longer. When I asked for the ideal duration, she reminded me that the work ‘has its own duration, its duration is within’ (personal communication, 2017). We spent a lot of time talking about duration. We did not ever work from somewhere other than the beginning, and this may partially explain why the work needs time after these meetings to establish itself. There is always a clear beginning, some definable middle section and some clarity around the ending. Everything else needs to be developed more fully.

Radigue kept a precise track of the length of the piece with her stopwatch. She created a sketch for the score, a description of the shape and texture, which exists for each of the works. Drawn in a notebook, they were shared with me at our meetings and are a kind of memory aid for her, to remember the shape of sound when such a slow evolution makes detail impossible. These are similar in style to the drawings for some of her synthesiser works, reproduced in Eckhardt’s book (Citation2019, 117).

Radigue also alerted me to tension—and how that will not help the piece. Sometimes she watches my hands, looking for any indication of physical tension. It became clear during these meetings that she aimed to experience the natural resonance of the instrument, rather than the parameters to which it was designed to sound for, despite, or because of, the ‘perfection of acoustic instruments’ (Citation2019, 21). We spent considerable time searching for ways to create the ‘rich and subtle interplay of their harmonics, sub-harmonics, partials, just intonation left to itself, elusive like the colours of a rainbow’ (Citation2019, 21). She insists that the harmonics come naturally, that little beatings should evolve, and that a unique richness of a note’s fundamental should be established yet never overstated. We aimed for sparkling sounds—not as core sounds, but as artefacts of other mechanisms. The compositional process focused on seeking out these sounds, and providing a structure for them to evolve and develop. The tuning needed to be unusual, to facilitate the unique sounds, and extending the headpiece of each instrument contributed to an instability that was useful. When I asked if I should learn to circular breathe, she told me it was not necessary. Over the duration of the piece, my breathing became part of a longer trajectory of sound. She remained very still while listening. She told me that however long the work becomes in our sessions, it would grow twice as long when I started to work on it alone. There was always a long pause at the end of each play through, and my memory of these is almost stronger than the sounds I made at the time, something happens to the air after these works, as if it has been readjusted. Our very focused work was broken up with long tea breaks with sweet snacks.

At the end of our first session, Radigue gifted me a recording of the OCCAM works (Radigue Citation2017). As during my first visit, I returned to my accommodation and listened to the compact disc with headphones in the dark. Then, I returned to Radigue’s apartment to work on the piece two more afternoons. She acknowledged how demanding it is, and often compared the flute sound and performance to that of other instruments, asking questions about various technical conditions. She reminded me that what comes out of these sessions is only the first part of the process: I will have to work on the piece until it ‘settles’. For me, this means acquiring an exacting control of the sounds we found together, and learning how they unfold through the piece. In each session, she talked about the spirit of the work, frequencies and structure. She talked about what she discovered in the sounds, and was not afraid to tell me when it didn’t work. I sometimes knew it myself, but not always. The easiest way was always the best. We talked about spontaneity and intensity, and discussed how my water images could help navigate the intensities of the work. I visited Robinson between these sessions, and we compared notes about the process. Throughout the meetings with Radigue, I took notes on fingerings, the order and shape of things, points from conversations. I returned to and revised these notes before each performance. I made some recordings of our conversations and the playing, with her blessing.

Upon my return to Australia, I continued to prepare for the premiere. Unfortunately, the venue turned out to have a dry acoustic, and the promoter, also the commissioner of the work, Lawrence English, wanted to amplify the performance to compensate. This was not a suitable solution, as it would result in too directional a sound and a loss of what Radigue calls the ‘magic of the colour’ (personal communication, 2017). Instead, we agreed to have the audience surround me on the floor of the stage.

The audience’s proximity was at once confrontational and intimate, and the acoustic was still flat, resulting in a difficult premiere. I wondered if the entire large audience could hear the important details of the piece. My breathing suddenly felt dislocated from the sound, and this made me realise how much a part of the piece it was.

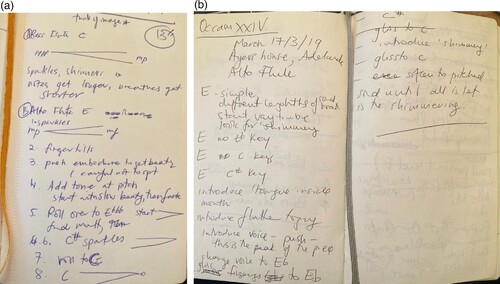

At the next performance in March 2019, I found that playing the piece only on alto flute felt easier and more natural. I had never been comfortable with the changeover, no matter how careful I was to make it silent and inconspicuous. Also, I could slide through larger intervals with the fingerings and embouchure on the alto. I contacted Radigue for endorsement, and this new version was premiered to a small attentive audience in Adelaide and in a more suitable acoustic. The notebook guides made for each version can be seen in . Toeplitz was also on the bill performing Elemental II, and I was working with him on other projects including the development of a work for him with harpist Hélène Breschand.

Figure 2. (a) Notes for the original OCCAM XXIV (Citation2018) for bass flute and alto flute. (b) Notes for the final, alto flute only version.

My communication with members of the composer-performer circle for the preparation of the performance of these works was key. It is a community that weaves in and around each other. In many ways, it is this notion of community that demands the works be shared, not cloistered amongst those that ‘know’. In our conversations, Radigue made it clear that this was her intention. After the concert in Adelaide, Toeplitz agreed to teach me Elemental II on bass guitar. Later that year, I committed to passing on OCCAM XXIV to Luke Nickel, a flutist and author of an early paper about the OCCAM pieces (Nickel Citation2016). I don’t feel like the work will be complete until this sharing has occurred.

OCCAM River XXIV for Alto Flute and Cello (2019)

In Citation2019, I approached Radigue about creating a duo for myself and Australian cellist-composer Judith Hamann. Hamann had studied with Charles Curtis—a frequent collaborator of Radigue's—and had performed Radigue’s feedback piece Vice-Versa, etc … (1970) with Curtis in New York in 2019. Hamann had performed several compositions of mine, so I knew that we shared a mutual respect for the level of detail and intimacy that Radigue’s music required. A new collaboration with Radigue initially seemed improbable since she was no longer planning to make works for new instrumentalists. But Hamann’s connection with Curtis and her compositions for cello and humming (Hamann Citation2020), piqued her interest.

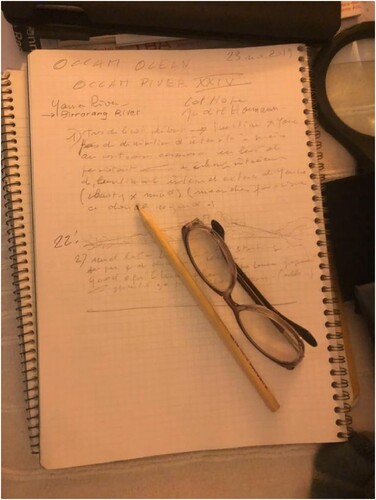

At our first session, Hamann and I played together for Radigue at her home. We talked about our image choice—the Birrarung (Yarra) river, a place in Melbourne where we had both spent time. Radigue titled the work OCCAM River and shared her sketch of the score with us (see ). We returned for two more sessions, but sadly the 2020 premiere planned in Tasmania, Australia was postponed and it has been, at the time of writing this text, over three years since Hamann and I have worked on the piece.

Figure 3. A notebook entry by Radigue for OCCAM River (Citation2019).

Preliminary Conclusions

I learned about some fixed elements in Radigue’s music through my collaboration with her and have aimed to create a kind of exegesis for the works I performed. In this article, I sought to illuminate the contexts in which they existed, and hopefully facilitate a rich understanding of them. I respect the need for some aspects of Radigue’s working processes to remain private, yet I am also wary of creating exclusivity for works and processes that merit sharing. I intentionally refrain from discussing the images I use for the works, or their specific locations, and I don’t wish to share the images themselves. These decisions are the result of discussions with Radigue who was concerned that her music would be over-simplified through analyses of these images as a kind of score. Printed materials can be dangerously and erroneously considered authoritative. This is compounded by the nature of the recordings, which, as I mentioned earlier, do not always represent her music well. Recordings of this music seem to miss the most extraordinary highlights experienced when listening to it live.

Radigue’s music creates a unique compositional and performative experience. The composer-performers in Radigue’s circle each bring something to the process of making these works which I have sought to describe.

Radigue always sends me a message before a performance of her music, and I make sure she always knows when one is taking place and send her documentation thereof. This composer-performer circle is about connection and growth, exchange and debate, perspectives and experiments. Radigue and I have become friends. As Radigue inscribed a recent book, ‘This wonderful experience of sharing again, one of these miracles … moments … music’. She described our experience perfectly, and better than I possibly can ().

Figure 4. Cat Hope and Eliane Radigue, after working on OCCAM XXIV (Citation2018) in 2018.

Performances (through 2021)

OCCAM Hexa II (Citation2015) (co-composed with Carol Robinson) for C flute, clarinet in Bb,

viola, cello, marimba, and bass drum

World Premiere (first Radigue work in Australia): Perth: Perth Institute of

Contemporary Art, 30 October, 2015

European premiere: Berlin: Studio 8, 26 November, 2017

Further Performances: Hamburg: Forum Neue Music, Christianskirche, Hamburg

Ottensen, 29 November, 2017; Melbourne: Substation, 30 August, 2019

OCCAM XXIV (Citation2018) for alto flute

World Premiere: Open Frame, Carraigeworks, Sydney 28 June, 2018 (alto flute/bass flute)

Adelaide: Ayers House, 18 March, 2019 (alto flute, solo)

Melbourne: Substation, 30 August, 2019 (alto flute, solo)

Athens: Auditorium Ioannis Despotopoulos, Athens Conservatoire, 3 December, 2022 (alto flute, solo)

Acknowledgements

OCCAM HEXA II (2015) was commissioned and performed with support from the Government of Western Australia Local Government, Sports and Cultural Industry. Special thanks to the members of Decibel involved in OCCAM HEXA II (2015); Tristen Parr, Lindsay Vickery, Stuart James, and Aaron Wyatt.OCCAM XXIV (2018) was commissioned with assistance from Room 40 and Carriageworks. I would like to thank both Éliane Radigue and Carol Robinson for their generosity, music, and friendship.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Cat Hope

Cat Hope is a composer, musician, artistic director and academic. She is the co-author of Digital Arts—An Introduction to New Media (Bloomsbury, 2014), co-editor of Contemporary Musical Virtuosities (Routledge, 2024) and director of the Decibel new music ensemble. Her composition practice engages graphic, animated notation, but she is also a improvisor, songwriter, and curator. She is a Civitella Ranieri and Churchill Fellow, and her 2017 monograph CD Ephemeral Rivers (Hat[Art]Hut) won the German Record Critics Prize that year, when Gramophone magazine called her ‘one of Australia’s most exciting and individual creative voices’. Cat is Professor of Music at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia.

Notes

1 For a more detailed discussion of this work, see Hope and Robinson (Citation2017).

References

- Decibel. 2018. The Last Days of Reality. [Audio recording]. Brisbane: Room 40 4102.

- Dougherty, William. 2021. “Imagining Together: Éliane Radigue’s Collaborative Creative Process.” Doctor of Music Arts Thesis. Columbia University.

- Eckhardt, Julia, Ed. 2019. Éliane Radigue—Intermediary Spaces. Brussells: Umland.

- Girard, Bernard. 2013. Entretiens avec Éliane Radigue Collection Musiques XXe–XXIe. Paris: Editions Aedam Musicae.

- Hamann, Judith. 2020. Music for Cello and Humming. [Audio recording]. New York, NY: Blank Form Editions BF 108.

- Hope, Cat. 2023. “Low Frequency as Concept in the Music of Cat Hope.” In The Composer, Herself, edited by Linda Kouvaras, Natalie Williams, and Maria Grenfell, 257–272. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hope, Cat, and Carol Robinson. 2017. “OCCAM HEX II: A COLLABORATIVE COMPOSITION.” Tempo 71 (282): 18–28. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0040298217000584.

- Nickel, Luke. 2016. “Occam Notions: Collaboration and the Performer’s Perspective in Éliane Radigue’s Occam Ocean.” Tempo 70 (275): 22–35. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0040298215000601.

- Nickel, Luke. 2020. “Scores in Bloom: Some Recent Orally Transmitted Experimental Music.” Tempo 74 (293): 54–69. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0040298220000261.

- Radigue, Éliane. 2015. OCCAM HEXA II. [Music composition].

- Radigue, Éliane. 2017. Occam Ocean Vol. 1. [Audio recording]. Paris: Shiin 1.

- Radigue, Éliane. 2018. OCCAM XXIV. [Music composition].

- Radigue, Éliane. 2019. OCCAM RIVER XXIV. [Music composition].

- Robinson, Carol, Charles Curtis, and Bruno Martinez. 2013. Éliane Radigue: Naldjorlak I, II, III. [Audio recording] Paris: Shiin 9.

- Toeplitz, Kasper. 2005. Éliane Radigue: Elemental II. [Audio recording] Sleaze Art - r.o.s.a._01, 1 CD.

- Yip, Viola. 2015. “DARMSTADT 2014: THE COMPOSER-PERFORMER.” Tempo 69 (271): 69–72. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0040298214000679.