ABSTRACT

For almost a century, unionists won a majority of seats in every election to Northern Ireland's regional parliament or assembly. That unbroken run came to an end in March 2017 when unionists became a minority in the Northern Ireland Assembly for the first time. Much scholarly analysis of this new dispensation characterises it as part of a long-term shift away from the binary politics of ethnonational division and majoritarianism as support grows for parties aligned with neither unionism nor nationalism. This paper offers an alternative analysis that emphasises the persistent importance of constitutionally related majorities. It argues that the emergence in 2017 of a non-unionist majority in the Assembly removed the last vestiges of a dominant party system that had endured in one form or another since the establishment of Northern Ireland. It marks the birth of a new party system, bringing about a much more fundamental shift in the dynamics of political competition than is generally understood. Rather than moving the politics of Northern Ireland beyond constitutional questions, it brings those questions to the forefront, with profound implications for the long-term relationship between Northern Ireland on one hand and the Republic of Ireland and Great Britain on the other.

Majority no more

For almost a century unionists won a majority of seats in every election to Northern Ireland's regional parliament or assembly. That unbroken run ended in March 2017 when unionists took just 40 of the 90 seats available. The impact of this turning point was reinforced by the May 2019 European Parliament elections when unionists – who had always taken two of the three Northern Ireland seats – were reduced to just one; and the December 2019 Westminster elections in which unionists were reduced for the first time to a minority among Northern Ireland's 18 MPs. The era of assured and predictable unionist majorities had ended, several years after the unionist vote had first dipped below 50%. If unionists do manage to secure a majority in the Assembly again it is likely to be a one-off resurgence given the steady long-term decline in the unionist vote. Some scholarly analysis of the new dispensation in Northern politics characterises it as a move away from the binary politics of ethnonational division and majoritarianism. In this view the lines of tribal loyalty are beginning to soften as a growing number of voters reject the labels of unionist and nationalist (Tonge, Citation2020; Whitten, Citation2020).

This paper offers an alternative analysis that keeps constitutionally related political majorities firmly at its heart. It characterises the new political dispensation since 2017 as the removal of the last vestiges of a dominant party system and the emergence of an alternative electoral and parliamentary majority – a non-unionist majority – for the first time since Northern Ireland was established.

The term non-unionist refers to all political parties and candidates that do not embrace the unionist label. While this is a disparate group, it is politically meaningful because it provides the basis for an alternative working majority in the Assembly. The politics of the Republic of Ireland provides a precedent for a working coalition of ‘all others’. For many decades competition for government pitted the dominant party, Fianna Fáil, against ‘the rest’ who were unified only by the fact that they were not Fianna Fáil. Despite their often-wide ideological differences ‘the rest’ were able to come together and form coalition governments on almost every occasion when they secured a majority of seats (Mair, Citation1979, p. 453).

This profound shift in the party system in Northern Ireland is linked to, and reinforced by, the emergence of new cross-cutting cleavages on constitutionally relevant issues. There is still a pro-union majority that would vote to remain in the United Kingdom in any referendum on Irish unity, but there is also a pro-EU majority, a socially liberal majority (on touchstone issues such as marriage equality and abortion) and a majority favourably disposed to stronger links and cooperation with the Republic of Ireland. The quest to build stable majorities on issues related to the constitutional status of Northern Ireland remains a central driving force of Northern politics.

To better understand the significance of this new party system the paper revisits the debate on unionist majority rule prior to 1972 and offers a new reading of the electoral calculus that hindered the construction of an alternative non-unionist majority. I move then to examine the gradual emergence from 1997 onwards of a robust non-unionist majority in Belfast City Council, identifying some key features of the changed electoral calculus that would later emerge at the level of Northern Ireland as a whole.

The paper analyses the factors that contributed to the emergence of an alternative majority in the Assembly in 2017, including dealignment from core ethnonational ideologies, demographic change, and the emergence of new cross-cutting cleavages. It argues that the most significant change in 2017 was not the erosion of ethnonational identification but the construction of an alternative parliamentary majority that brought an end to a dominant party system – later a dominant bloc system – that had persisted for almost a century.

Dominant party system and ethnic party system

From the establishment of the Northern Ireland Parliament in 1920–1921, Northern Ireland had a dominant party system of an exceptionally strong type in which the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) formed every government for 50 years. The system was only ended in 1972 by large-scale violence and the breakdown of order. Research on the party system in Northern Ireland has long been dominated by the ethnic dual-party model elaborated by Mitchell (Citation1995, Citation1999) and others (Coakley, Citation2008; Mitchell, Evans, & O’Leary, Citation2009; Mitchell, O’Leary, & Evans, Citation2001). The model – which is used to analyse post-1972 politics rather than the Stormont era – stresses competition between parties within ethnic blocs and sheds powerful light on key aspects of electoral competition, including the importance of reinforcing social cleavages and the pressures for, and against, ethnic polarisation.

References to Northern Ireland as a dominant party system, in contrast, are rare; just a few authors cite unionist majority rule before 1972 as an example, and they do so fleetingly (Crighton & Iver, Citation1991, p. 131; Mair, Citation1996, p. 96; O’Leary, Citation2019, p. 9). But the concept of the dominant party system has untapped potential for analysing patterns of competition in Northern Ireland well beyond the ending of unionist majority rule and is vital to appreciating the depth of the changes since 2017.

A dominant party system is one in which a single party dominates over a long period of time (Giliomee & Simkins, Citation1999). In its strongest version, the same party repeatedly wins a majority of seats in parliament and controls government over several elections, as the Congress Party did in India for decades after independence, and the ANC in South Africa (Bogaards, Citation2004, pp. 174–176; Kaßner, Citation2013). Sartori (Citation1976, p. 174, 193–194), in his influential typology of party systems, defines the dominant party as the party that repeatedly ‘outdistances all the others’ (although he prefers the term ‘predominant party’).

Electoral dominance is not the only defining feature of dominant party systems, however. Duverger (Citation1959, pp. 308–309, 312), the first scholar to identify the phenomenon, defined a dominant party as one that is consistently larger than any other party in the system over an extended period of time. But he stressed too that a party is dominant ‘when it is identified with an epoch’ (Duverger, Citation1963, pp. 275–280). Scholars have built on this insight to argue that dominant parties are defined in part by ‘the successful implementation of a historical project over a long period of time … [that] … significantly shapes the political culture of society’ (Kaßner, Citation2013, p. 31). It may include the foundation of a new political order: ‘many dominant parties … have been closely identified with the creation of the constitutional and political order that they came to dominate’ (Arian & Barnes, Citation1974, p. 595). The UUP was the dominant party in Northern Ireland not only because of its electoral support but because of its identification with the foundation of a new political order and the long-term project of establishing and maintaining Northern Ireland. Importantly, a dominant party does not have to enjoy an overall majority. It can maintain its parliamentary majority instead through a stable alliance with ideologically congruent ‘satellite parties’ (Blondel, Citation1968, pp. 196–197). I turn now to examine how Northern Ireland's exceptionally strong dominant party system was sustained for so long.

Sustaining the dominant party system

The stability of Northern Ireland's dominant party system prior to 1972 was not an automatic consequence of majority support for the union with Great Britain. It was possible to support the union while rejecting the ethnonational solidarity that characterised political unionism: to be both pro-union and non-unionist. For many scholars of the period, the great lost hope was the failure of pro-union parties that courted both Protestant and Catholic support – such as the Northern Ireland Labour Party and the Ulster Liberals – to ‘break the sectarian deadlock of unionist and nationalist politics’ (Buckland, Citation1986, p. 727). It was hoped that Unionist Party domination might be overturned by a non-unionist majority built on a foundation of voters who had freed themselves from ethnonational loyalties. Scholars focus above all on the Northern Ireland Labour Party's successful inroads into the UUP vote in the early 1960s, especially in Belfast (Bew, Patterson, & Gibbon, Citation1979; Edwards, Citation2013; Loughlin, Citation2018; Walker, Citation1985). The failure to end Unionist majority rule prior to 1972 is attributed to the Ulster Unionist Party's successful playing of ‘the Orange card’ to frighten Protestant voters back into the Unionist fold on the basis that all opposition ‘wittingly or unwittingly … helped Ulster's enemies’ (Loughlin, Citation2018, p. 92).

But the vision of an alternative non-unionist majority constituted by voters who had freed themselves of their ethnonational shackles – expressed in the rhetorical attacks by Labour activists in the 1960s on both ‘Orange and Green Tories’ – obscured a blunt mathematical reality. Given that the large Catholic minority could be relied on to vote consistently for non-unionist candidates, a non-unionist majority dominated by the Catholic electorate and by parties and candidates associated with that community would emerge long before a non-unionist majority that drew more or less equally on both Catholic and Protestant voters. And however willing Catholics might be to vote Labour or Liberal, nationalist and republican sympathies remained strong among that electorate. The most plausible route to a non-unionist majority then was to build it on the foundations of the consistently anti-unionist Catholic electorate, allied to sections of the Protestant electorate who were willing to be part of a broader non-unionist majority.

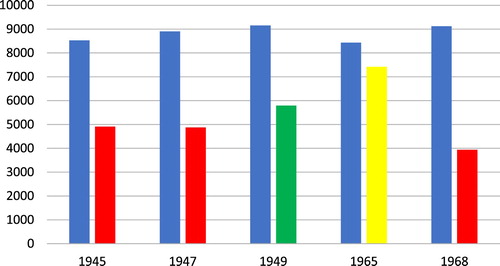

The obstacles to constructing an alternative majority of this kind are neatly illustrated by the electoral history of a Stormont constituency that closely mirrored the overall population balance in Northern Ireland: the City of Londonderry constituency that covered the city's Waterside and historic city centre. Just under 40% of the electorate here was Catholic and just over 60% Protestant and, as in Northern Ireland as a whole, the Unionist Party won every time. Unionist victory was so predictable that in four successive elections between 1951 and 1962 the UUP candidate was elected unopposed. This was part of a broader pattern in Northern Ireland where large numbers of seats were uncontested at every election due to the predictability of voter preferences (O’Leary & McGarry, Citation1996, pp. 123–124). But the failure to elect a non-unionist in City of Londonderry was not the result of unwavering loyalty to ethnonational blocs. Far from being a contest between Orange and Green Tories, in which voters remained loyal to their ‘tribe’, Catholic voters here showed remarkable promiscuity in party support and a consistent willingness to vote for any non-unionist candidate. In successive elections the vast majority of Catholic voters supported the Northern Ireland Labour Party (1945 and 1947), the Nationalist Party (1949), the Ulster Liberals (1965) and the Northern Ireland Labour Party (1968) against the Ulster Unionist candidate. Even when the Northern Ireland Labour Party was strongly attacking and challenging the Nationalist Party in 1968 it was still able to take the great majority of Catholic votes. But while Catholics were generally willing to vote for non-unionists regardless of political stripe, virtually no Protestant voters in the constituency cast their vote for a non-unionist, regardless of the candidate's party or religious background – with the telling exception of one election.

In 1965, Derry was rocked by the ‘Faceless Men’ controversy surrounding the role of senior Derry Unionists in secretly lobbying against the opening of a new University in Derry lest it disturb Unionist electoral control of the city (Ó Dochartaigh, Citation1999; O’Brien, Citation1999). In these unique circumstances, Ulster Liberal Party candidate, Claude Wilton, a Presbyterian and a lawyer who had been prominent in the University campaign, finally succeeded in securing substantial Protestant support, taking perhaps 700 votes – or 8% of the unionist vote.Footnote1 But even in these most unusual of circumstances, fewer than a tenth of unionist voters were willing to vote for a Presbyterian Ulster Liberal. It signifies just how great the obstacles were to the construction of a winning coalition of non-unionist voters. In voting for a non-unionist of any variety, Protestants would be voting for someone strongly associated with the Catholic minority. Wilton's strong association with that community, and his electoral need to maintain a strong identification with them was summed up in the unofficial election slogan ‘vote for Claude the Catholic prod’ (Ó Dochartaigh, Citation1999, p. 75) ().

Figure 1. City of Londonderry election results, 1945–1968 (Stormont constituency). Blue = Unionist; Red = Labour; Green = Nationalist; Yellow = Liberals.

The example indicates that a fundamental obstacle to a non-unionist electoral majority was the unwillingness of sufficient Protestant voters to vote for candidates who might form part of a non-unionist majority that was built on the foundations of the Catholic minority. It suggests that one of the most profound changes in the early twenty-first century is the growing willingness of substantial numbers of Protestant voters to form part of such a non-unionist majority. We turn now to look at the persistence of elements of the dominant party system after the introduction of Direct Rule in 1972.

From dominant party system to dominant bloc system

The party system that emerged after the suspension of Stormont in 1972 has been usefully characterised as an ethnic dual-party system in which ethnonational parties competed for votes within their own ethnic blocs (Mitchell, Citation1995). But in one important respect the post-1972 system was not a conventional party system at all. As far back as 1996, Peter Mair argued that party system classification schemes are ultimately aimed at understanding patterns of government formation and alternation. To analyse party systems is to ask the question: ‘How might differential patterns in the competition for government be understood’ (Mair, Citation1996, p. 90). After 1972, parties in Northern Ireland were not competing to form a government: the election in 1973 was a partial, and fleeting, exception. Instead they sought to shape British government actions and influence any anticipated constitutional settlement. Party competition during these long decades of Direct Rule is best understood not as a conventional party system but as a period of suspension of the normal dynamics of electoral competition. Parties and voters might well have acted differently if government power had been at stake. Above all, Direct Rule reduced the incentives for unionist unity. As Coakley puts it, ‘the disappearance of the Northern Ireland House of Commons undermined the imperative of cohesion on the unionist side (since formation of a parliamentary majority was no longer crucial)’ (Coakley, Citation2008, p. 776).

After 1972, the UUP was no longer a dominant party. It became instead the leading party in a dominant bloc, forming a majority in combination with other unionist parties: ideologically-congruent ‘satellite’ parties to use Blondel's term. The centrifugal character of the ethnic dual-party system ensured that the unionist parties – with the exception of the period surrounding the Sunningdale Agreement in 1973–74 – remained strongly aligned with one another on key contentious issues and regularly agreed election pacts to ensure the victory of candidates from the bloc where competition between them might result in victory for a non-unionist. The coherence of the bloc was demonstrated by the coming together of unionist parties in the United Ulster Unionist Council from 1974 to 1976; the Constitutional Convention report of 1975 that called for the restoration of simple majority rule; and the 1985 campaign against the Anglo-Irish Agreement. Where once the dominant party could be sure of a majority in every parliament or assembly and was identified with the founding ideology of the state, now it was the dominant bloc that was assured of a majority and was identified with the state. The dominant party system had evolved into what we might call a dominant bloc system. This system was disrupted in 1998 when the UUP backed the Good Friday Agreement while the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) opposed it. Nonetheless, the unionist parties remained unified on a range of crucial issues and the DUP's acceptance in 2007 of the institutions established by the Good Friday Agreement allowed for the working unity of the bloc to be restored. When the DUP became the largest unionist party in 2003 it took on the mantle of leading unionist party from the UUP which in turn became a ‘satellite’ to the DUP. The continuities are personified in the transfer of a whole generation of younger UUP members to the DUP including key leadership figures Arlene Foster and Jeffrey Donaldson, with Foster becoming DUP leader in 2015.

One might have expected the dominant bloc system to come to a definitive end when the consociational system of government established under the Good Friday Agreement finally got up and running on a sustainable basis in 2007. But despite power-sharing, majorities and thus dominant blocs remain important. Most decisions in the Northern Ireland Assembly are made on the basis of a simple majority and the DUP and UUP have voted together as a unionist majority bloc on a wide range of issues, and are particularly unified on sensitive issues related to the constitutional question.

Most importantly of all, the leading unionist party continued to be the senior party in every government – pointing up a curious continuity between UUP majority rule prior to 1972 and the consociational system. The commonality between consociational and dominant party systems was discussed by Peter Mair as far back as 1996. Describing government alternation as one of the key dimensions on which party systems differ, Mair (Citation1996, pp. 91–92) identified three patterns of alternation. The third of these, a pattern of ‘non-alternation’, is a characteristic of both dominant-party systems and consociational systems:

the third pattern is marked by a complete absence of alternation, or by non-alternation, in which the same party or parties remains in exclusive control of government over an extended period of time, being displaced neither wholly nor partially. Switzerland offers the clearest example of non-alternation over time, with the same four-party coalition holding office since 1959. A similar pattern of non-alternation clearly also characterises what Sartori defined as predominant-party systems, as in the case of Japan from 1955 to 1993 …

Majority rule and consociationalism alike were characterised by non-alternation of government in Northern Ireland. And in both systems the largest unionist party was the dominant party in government. A kind of consociational majoritarianism emerged after 2007 that preserved certain features of the dominant party system. The DUP strongly asserted its primary position in government, not only because it was the largest party, but because it spoke in the name of a majority unionist electorate and the historical project of the Northern Ireland state. The DUP's pre-eminent position was reinforced by the gap in power suggested by the titles of First Minister and Deputy First Minister. The two positions – the first held by a unionist and the second by a nationalist – have equal power but the titles suggest otherwise. Consistent unionist occupation of the position of First Minister, combined with the unionist majority in the Assembly and in the wider population, strongly influenced the dynamics within the Executive. That said, the consociational structures set tight limits on the exercise of authority by the leading unionist party. It could be exercised only as long as it was accepted by the leading nationalist party, Sinn Féin, as was demonstrated when Sinn Féin withdrew from government in January 2017, triggering the suspension of the Executive and the Assembly for the following 3 years.

Belfast: foreshadowing the new non-unionist majority

The non-unionist majority in the Northern Ireland Assembly was foreshadowed 20 years earlier in Belfast City Council (BCC) where non-unionists first won a majority of seats in 1997, initially with a one seat advantage. This became a clear majority in 2011 when nationalists took 24 of the 50 seats and Alliance 6. In 1997, this non-unionist alliance provided the city with its first SDLP mayor, and in 2002 its first Sinn Féin mayor. The City Council has been a test bed for the emergence of a politically coherent non-unionist majority and highlights some of the political changes we might now expect to see in Northern Ireland as a whole.

BCC showed that a disparate non-unionist majority, based on the large nationalist parties – Sinn Féin and the SDLP – combined with Alliance and later the Greens and People Before Profit, could develop a robust working alliance. Most significantly of all, the new non-unionist majority showed itself capable of taking and defending positions even on sensitive issues associated with the nationalist-unionist divide. These included the 2012 decision to fly the Union flag over Belfast City Hall on designated days only, and the Council's support for Irish language measures. It showed the resilience and strength of a non-nationalist voter base that was prepared to be part of a non-unionist coalition even on issues of constitutional sensitivity. The starkest evidence of this was provided during the unionist flag protests of 2012–2013 (Nolan et al., Citation2014).

When Sinn Féin and the SDLP voted in support of an Alliance party motion in December 2012 that the Union flag no longer be flown over Belfast City Hall every day, but instead on 18 ‘designated days’ important to the UK's national calendar, the Alliance party came under sustained attack. As the vote approached, the DUP and UUP circulated 40,000 leaflets ‘warning in emotional language that the Alliance Party policy was a threat to unionist identity’ (Nolan et al., Citation2014, p. 9). Loyalists and unionists launched a wave of street protests after the vote; the homes of several Alliance party representatives were attacked, their offices picketed and, in some cases, attacked and ransacked.

The flags campaign sought to make it impossibly difficult for Alliance to combine with nationalists by intimidating activists and eroding the party's support among Protestant voters. In many ways it was a reaction to the longer term issue of the robust non-unionist majority on BCC. Despite the immense pressure, Alliance stuck by its position and, crucially, was not damaged electorally. In the May 2014 local elections, the Alliance vote held up well, dropping by just 0.7%. The party lost one of its 9 seats in BCC but this was picked up by another non-aligned party rather than by a unionist. And in the European Parliament election of 2014 the party's candidate Anna Lo increased the Alliance vote by 1.6%, to 7.2%, its best European election result to date.

The failure of the flag protests to reverse the new majority in BCC also solidified that non-unionist coalition, allowed them to prepare for similar challenges in the future, and provided vital information to parties such as Alliance about the robustness of their support base. It demonstrated that, even on some of the most difficult issues, parties reliant in large part on support from voters of Protestant background were willing to work as part of a non-unionist majority. And their voters were willing to stick with them when they did.

Cross-cutting cleavages and the emergence of an alternative majority

The emergence of an alternative majority in 2017 in Northern Ireland as a whole was made possible by three long-term trends: a decline in the Protestant proportion of the population; increasing dealignment from unionist and nationalist identities; and an increase in secularism and social liberalism.

The Protestant population on which unionist parties relied almost exclusively for support began to decline in the early 1970s: from around 63% in 1961 the Protestant population had fallen to 41.6% by 2011. This was partly due to the relative growth of the Catholic population – from 34.9% to 40.1% over the same period – and partly to the growth in those associated with neither group. By 2011 the numbers stating no religion had surged to 10.1% while 6.8% did not state their religion. The size of both groups had been negligible in 1961 (https://www.nisra.gov.uk/statistics/census).

The UUP had long defined itself as a party of the Protestant community and Northern Ireland as a ‘Protestant country’. Belated efforts by the UUP to rebrand in the 2000s as a party of the Union rather than of the Protestant community, promoting a ‘simply British’ identity and representing unionism as a multicultural and diverse cause, were implausible and failed comprehensively (Hennessey, Braniff, McAuley, Tonge, & Whiting, Citation2018). The flag protests in 2012–2013 and subsequent attempts by the UUP to outflank the DUP on the right on sensitive issues such as dealing with the past and the so-called ‘border in the Irish Sea’ have compounded the identification of unionism with one community. Unionist parties continue to be defined by their identification with the Protestant community. The result is that, as the Protestant electorate shrinks, the unionist vote shrinks.

Dealignment from the two main blocs is a second factor. Many of those with no religion or who do not state a religion nonetheless identify with either the Catholic or Protestant community. But the growth of this group is an indicator of a broader trend, a decrease in strong identification with core nationalist and unionist identities and positions by many Catholics and Protestants (Hayward & McManus, Citation2019). The consequences for nationalism and unionism are asymmetrical. The nationalist vote rose steadily from the early 1980s, peaking at 42.7% in 2001. It has fluctuated since then, ranging between around 38.4% and 41.1% in recent Westminster and Assembly elections, but it remains close to its all-time high. Until the early 1980s unionists regularly took 60% of the vote. By 2010 that had dipped below 50% on a few occasions and unionists have not succeeded in securing a majority of the vote in a Westminster or Assembly election since the Westminster election of that year. Nationalist growth has levelled off while long-term unionist decline seems set to continue despite occasional upward bumps such as the surge in the unionist vote to 48.7% during the highly-polarised 2017 Westminster election that took place in the shadow of the suspension of the Executive and the Assembly (https://www.ark.ac.uk/elections/).

Dealignment from the blocs has contributed to the consolidation and growth of a robust non-unionist vote among many from Protestant backgrounds, chiefly for the Alliance Party and the Greens. This development has a very different character from support for third parties in earlier periods. When unionists formed a solid majority the position of parties such as Alliance that they would abide by the wishes of the majority on the constitutional issue meant that they were effectively pro-union. But in a context where unionists are no longer a majority and where there is a greater degree of openness to changes in north–south relations among those who are neither unionist nor nationalist, these parties have a very different character. They are now much more clearly distinct from the unionist position on north–south relations even if the bulk of their voters support the union.

The final trend damaging unionism is the growth in socially liberal attitudes. As support for liberal reform on the touchstone issues of abortion and same-sex marriage increased in the 2000s, the two main unionist parties placed themselves on the conservative side of an emerging social cleavage that separated them from a new more secular and socially liberal majority in the North. While the Catholic conservatism of the old Nationalist Party had limited the possibility for an alliance with socially liberal Protestants, both Sinn Féin and the SDLP positioned themselves (despite the misgivings of a strong conservative Catholic element within the SDLP) carefully on the liberal side in most of these debates. This established an additional policy area in which majority opinion was politically represented by nationalists making common cause with the Alliance, the Greens and even many liberal unionists.

This made the unionist parties a minority in yet another policy field – notwithstanding unionist success in securing a majority in the Assembly to oppose British government abortion legislation in June 2020 by allying with SDLP MLAs (Moriarty, Citation2020). A large proportion of young socially-liberal Protestant voters have stayed loyal to the two main unionist parties despite this issue. But it has undoubtedly contributed to a fraying at the edges of unionist support, particularly among feminists and LGBT+ activists from Protestant and unionist backgrounds.

Brexit

Then came Brexit. The 2016 referendum established a new political cleavage in Northern Ireland between a strong British nationalist position and a broadly pro-European position on relations with the rest of Europe and the Republic of Ireland. It accelerated the development of a non-unionist coalition. The DUP supported Brexit from the outset using strong British sovereigntist rhetoric. In taking this stance the largest unionist party sought to fend off a challenge from the unionist and loyalist right that had been brewing since the flag protests of 2012–2013. But, like almost everyone else, the DUP did not expect the referendum to pass and had no apparent strategic approach to Brexit. Before the referendum the UUP supported Remain, although the party allowed its members to campaign for either side (Ferguson, Citation2016). After the result, the UUP moved much closer to a straightforward British nationalist position on the issue, arguing that the debate was over and that they now needed to implement Brexit and leave the EU. Seeking to outflank the DUP on its right flank, long regarded as the firmest ground on which to mount any challenge to the leading unionist party, the UUP argued against any special arrangements for the North that would distinguish it from Great Britain. When the EU Withdrawal Agreement provided for the North to stay in the European common market and, effectively, in its customs zone, thus necessitating checks on trade between Great Britain and the North, the UUP condemned the DUP for its failure to protect the Union (Moriarty, Citation2019). Unionist parties thus gradually came into alignment on the issue, both taking a strong position against any special arrangements that would weaken links with Great Britain.

From the outset the non-unionist parties, Sinn Féin, the SDLP, Alliance and the Greens, all took strong pro-remain positions. The exception was People Before Profit, a small all-Ireland, pro-unity, Trotskyist party that aligned with the Lexit (left-wing Brexit) position of a section of the British left. When the referendum was passed by a majority of 51.9% in the UK, but rejected by a majority in Northern Ireland, where 56% voted remain, unionists once again found themselves in a minority but this time on an issue that was directly connected to the constitutional question. Unionist parties, which had long invoked majority opinion in Northern Ireland, now found themselves in the uncomfortable position of arguing that majority support for EU membership in Northern Ireland could and should be disregarded and that only the slim overall pro-Brexit majority in the UK counted.

Even more seriously, unionist parties now positioned themselves on the minority side of yet another new social cleavage. Most dangerously of all for a unionism that had always emphasised the economic benefits of the Union, unionists now appeared to be willing to sacrifice the economic interests of the North for ideological reasons. In two elections in 2019, for the European Parliament and for Westminster, unionist parties suffered substantial electoral damage among Protestant voters for taking positions that were too rigid and too British nationalist. The unionist majority of elected representatives that had been lost in the Assembly in 2017 slipped away in two more arenas.

In the May 2019 European Parliament elections, unionists – who had always taken two of the three seats – were reduced to just one. The big winner was the Alliance Party whose leader Naomi Long took a seat as the party's vote surged from 7.1% to 18.5%. Alliance's positioning on the big issues of Brexit and social liberalism had paid off handsomely. Finally, in December 2019, the last bastion of the unionist majority fell. In the Westminster elections that month, unionists – who on several occasions after 1920 had won all of Northern Ireland's seats – were, for the first time, reduced to a minority among Northern Ireland's 18 MPs, and secured fewer seats than nationalist parties. The most striking result of the election was that in several predominantly Protestant constituencies thousands of erstwhile unionist voters turned to the Alliance Party. In Lagan Valley, DUP MP Jeffrey Donaldson's vote plummeted from 59.6% to 43.1% while the overall unionist vote in the constituency (including the UUP and the tiny vote for UKIP and the Conservatives) fell from 78.4% to 64.9%. The big winner was Alliance candidate Sorcha Eastwood who increased the party's vote from 11.1% to 28.8%. In North Down, Stephen Farry, the author of Alliance's strong pro-remain policy, took the seat previously held by independent unionist Sylvia Hermon. Almost all of Hermon's supporters chose Alliance over the DUP.

The most remarkable aspect of these election results was that the Alliance Party had taken a strong and unapologetic stance on Brexit. The party had argued that Northern Ireland needed to be treated differently from Great Britain and had worked closely and publicly with the Irish government and with the other non-unionist parties. Alliance spokesperson Stephen Farry was one of the foremost advocates of a special status for the North that would, in certain respects, leave it within the EU. The party had taken part in the forums organised by the Irish government in Dublin that were boycotted by both the DUP and UUP (McKeown, Citation2016) and took part in a high-profile joint delegation to Brussels with Sinn Féin, the SDLP and the Greens to put their joint position to EU Chief Negotiator, Michel Barnier, emphasising that they represented a majority in the North (Smyth, Citation2018). The four parties issued repeated joint statements on the issue and met in Dublin with Irish premier Leo Varadkar to support the Irish ‘backstop’ proposal (RTÉ, Citation2018).Footnote2 Rather than seeking a middle ground between unionist and nationalist positions on Brexit, the Alliance had aligned with non-unionist parties against the unionist position. Some unionists accused Alliance of being part of a pan-nationalist front (Kane, Citation2019). The result of all this was spectacular growth in the Alliance vote. For the first time ever, a party with substantial Protestant support had greatly increased that support by working with nationalists and the Irish Government to ensure continued strong links and an open border between the two Irish jurisdictions to serve the economic interests of Northern Ireland. This is not to suggest that Alliance has a shared position with nationalists on constitutional issues, nor even that the party will always find itself on the same side of the argument on issues surrounding Brexit. Nonetheless, it was an indicator of the depth of the change associated with the transition to a non-unionist majority in the Assembly.

The dynamics of Northern Ireland's new party system

The full implications of a new party system in which the unionist bloc is no longer guaranteed a majority of seats in the Assembly were obscured by the suspension of Stormont from 2017 to 2020 and the disruption of political life in the UK since the Brexit vote in 2016. The Executive and Assembly have had little opportunity to settle into a routine. Since March 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic has extended this period of exception. It might be argued that the new non-unionist parliamentary majority is of limited significance given the constraints of a consociational system that guarantees all significant parties a place in government. Despite the big changes in Assembly membership the D’Hondt system for choosing ministers ensures that unionists still hold five of the ten seats in government, including the symbolically important position of First Minister, while nationalists have 4 seats and Alliance 1. On the surface the shift in the balance of power may seem minimal.

Why then should the new majority make any difference? Despite consociationalism, most decisions in the Northern Ireland Assembly are decided on the basis of a simple majority vote. It means that unionists, even if they maintain their position in the Executive, now face the prospect of being repeatedly defeated in the Assembly on constitutionally-sensitive issues, most importantly on relations with the EU and the Republic of Ireland. The Assembly's vote to support an extension to the Brexit transition period by a majority of 48 non-unionists to 40 unionists in May 2020 was a sign of things to come (Campbell, Citation2020).

Unionists can of course resort to the Petition of Concern (POC, the minority veto) to block measures supported by a non-unionist majority in the Assembly. Because the POC can be used to block legislation but not to initiate it, the measure is structurally biased towards those seeking to preserve the status quo. Defending a hardline British sovereigntist position from behind the barricades of the POC carries risks, however. If unionists repeatedly block measures that are backed by a majority of Assembly members and voters – as the DUP did when it blocked same-sex marriage and abortion legislation during the previous Assembly term – it could erode unionist electoral support even further. Liberal-minded pro-European unionist voters may increasingly come to see the unionist parties as blocking forces without the necessary vision to effectively represent their preferences. If the unionist parties circle the wagons ever more tightly, they may find fewer and fewer people inside the circle.

A second factor in this shift in power is that the alternatives to sharing government power with Sinn Féin and others are now even less viable and less attractive than they were. Many Unionists long spoke of their preferred alternative to consociationalism as a ‘voluntary coalition’ that was envisaged as a unionist-dominated government in which the SDLP represented Catholics, thus allowing permanent exclusion of Sinn Féin. But the emergence of the new non-unionist majority has raised the prospect that a voluntary coalition might be nationalist-dominated with a small unionist party added on to fulfil the cross-community requirement – a much worse scenario for unionism than the current situation. A return to simple majority rule – the dream for many years of hardline unionists – could be even worse, potentially allowing for the complete exclusion of unionists from government. These two alternatives to consociationalism – neither of them very plausible to begin with – have now been closed off. So too has the option of Direct Rule from London. During the 3 years of Stormont's suspension the British Government refused to implement Direct Rule, even at the cost of deterioration in public services. And when Stormont returned, its restoration was based on an agreement proposed jointly and very publicly by the British and Irish governments (Moriarty & McClements, Citation2020). The commitment of the two states to bi-national leadership on the North is now firmly established and any prospect that might once have existed of Direct Rule and fuller integration with Great Britain, has evaporated almost completely. The brief period between 2017 and 2019 when the British government was directly dependent on, and thus responsive to, the DUP, is over. And even during this time the DUP proved unable to prevent a Withdrawal Agreement that the party denounced as catastrophic for the Union. The pressures for compromise are accordingly greater than ever. When the Executive was re-established in 2020 DUP First Minister Arlene Foster set a very different tone and there was a strong public projection of equal partnership (Emerson, Citation2020a). We might expect too that the DUP and UUP will try to avoid over-using the POC on the issue of Brexit and the EU despite the rhetoric of some of their MPs. DUP MP Jeffrey Donaldson's comments in early 2020 about the ‘new opportunities’ presented by the Withdrawal Agreement provides early indications of a DUP concern to avoid being trapped in a negative blocking position and a willingness to accept a certain strengthening of the links with the Republic of Ireland and a change in relations with Great Britain (Emerson, Citation2020b).

Brexit and constitutional change

The past 20 years has seen the gradual building of a loose but coherent non-unionist coalition, first in Belfast and from 2017 in Northern Ireland as a whole, that is capable of cooperating on sensitive constitutional-adjacent issues. In generating a range of simultaneously novel and urgent constitutionally-relevant issues, Brexit has created the perfect conditions for the consolidation of this coalition. The case for Special Status, that is, for the North to effectively remain within the EU when Great Britain leaves; the case for Northern Ireland to effectively remain in the EU's regulatory and customs zone (as provided for in the Withdrawal Agreement); the case for maintaining a soft border in Ireland even if it necessitates divergence from Great Britain: all of these are positions that either strengthen or protect links with the Republic of Ireland even if this results in a certain weakening of links with Great Britain. All of them enjoy the support of a non-unionist majority in both the Assembly and the electorate. By forcing a reorganisation of relations between the two Irish jurisdictions and Great Britain, Brexit has crystallised the non-unionist coalition around a constitutionally-sensitive issue. Moreover, the fact of a non-unionist majority, alongside the pro-remain majority in the referendum, has influenced the positions of both British and EU negotiators on Brexit, undermining the case for a hard Brexit for Northern Ireland and offering a popular mandate for special measures and a soft border.

Against the DUP's expectation, and demand, that any special arrangements with the EU would be subject to a unionist veto through the POC in the Assembly, the Withdrawal Agreement signed in January 2020 stipulated that the special arrangements would come into force at the beginning of the transition period. The Assembly has the right to vote 4 years later on whether to continue them, but on the basis of a simple majority vote. It is a measure of the change that has taken place that the Irish government and northern nationalists could accede to a simple majority vote on a major issue of this kind, confident that a unionist majority no longer exists and can no longer block changes unilaterally.

Unionist parties take comfort from the persistent majority support for remaining in the UK that is evident in almost all opinion polls and surveys, often by a substantial margin. But even on this central constitutional question there are signs of unionist uncertainty. The first, and only, border poll, back in 1973, was a concession to unionism – to allow a demonstration of strong majority support for remaining in the UK. Republicans and nationalists boycotted and opposed the poll. Now it is unionists who oppose a border poll, perhaps fearful that on a bad day, in a bad month, perhaps on the back of some catastrophic Brexit decision, support for Irish reunification might come close enough to 50% to make it seem inevitable. Such a result would establish a new context in which all parties and the two governments would increasingly orient themselves to a future reunification.

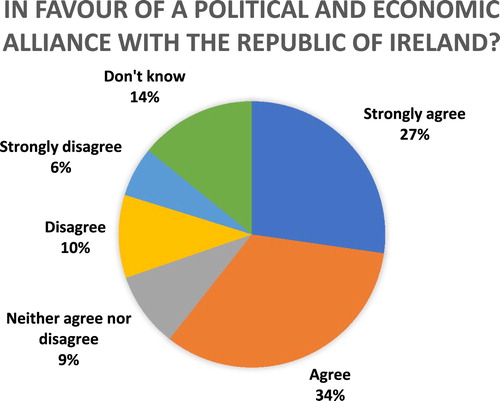

Despite this prospect, a border poll is not the main danger to unionist preferences on constitutional issues at the current moment. In the next five to ten years, the North will face a series of decisions on relations with the EU that are less stark than a border poll and in which a majority of the population are likely to support changes that strengthen relations with the Republic of Ireland and the EU even if that involves some weakening of ties with Great Britain. The potential for a strong non-unionist coalition in favour of such changes, with some support from liberal unionists, is hinted at in the 2017 Northern Ireland Life and Times survey. The survey has always shown strong majority support for staying in the UK, but in 2017 it found an even larger majority saying they were ‘in favour of Northern Ireland entering a political and economic alliance with the Republic of Ireland if it would help jobs and the economy’. Only 16% disagreed with this proposition ().Footnote3

Figure 2. Northern Ireland Life and Times survey results for a question in 2017 asking if people were ‘in favour of Northern Ireland entering a political and economic alliance with the Republic of Ireland’.

We may quibble over what exactly people understood by this somewhat leading question, but it indicates a much greater openness to stronger relations with the Republic of Ireland than is offered by the primarily defensive, and sometimes hostile, approach of the DUP and, to a lesser extent, the UUP. The goal of building closer relations between the Republic and the North is now associated with majority opinion in the Northern electorate and the Assembly.

The struggle to win a border poll is not the most important challenge for unionism in the coming years. More important now is that grey space between union and Irish unity in which there is great potential for building stronger links between the North and the Republic. If unionist parties repeatedly resort to the POC to block measures to strengthen cross-border ties, they present the non-unionist majority with the prospect of a permanent unionist veto from which there is only one escape: a vote for Irish reunification that requires a majority of just 50%+1. Unionists will want to avoid pushing people in this direction and this will require a move away from hard sovereigntist positions.

The old heart and the new

When Londonderry Corporation was abolished in November 1968, bringing an end to unionist minority control of the gerrymandered city and opening the way to nationalist control, one of the outgoing Unionist councillors commented sadly that ‘the new heart will never beat as loyally as the old heart’ (Derry Journal, 26 Nov 1968). Northern Ireland may remain in the UK for some time to come, but it has a new political heart now and it will never beat as loyally as the old.

This new context has stimulated talk of a new politics beyond unionism and nationalism and a new Northern Ireland identity that transcends the old divides. Some express the hope that the North might be on a long-term trajectory towards the end of ‘tribal’ politics, moving beyond a focus on constitutional issues. Viewed through the lens of the ethnic party system it might seem as though that system is beginning to weaken.

This interpretation fails to capture the central political dynamics of the new dispensation because it is overly focused on ethnonational allegiances and is insufficiently attentive to the importance of parliamentary majorities – even under consociationalism. If we analyse Northern Ireland politics as a dominant party system that evolved into a dominant bloc system, then the most significant change in 2017 was not the erosion of ethnonational identification but the construction of an alternative parliamentary majority that brought an end to a dominant party/dominant bloc system that had persisted for almost a century.

The key to that transformation was the construction of a ‘minimum winning coalition' – to borrow a concept used to understand government formation – that could offer an alternative majority in key Assembly votes on contentious issues. Converting the bulk of both Catholics and Protestants to a post-ethnonational politics was unnecessary when the Catholic minority could already be relied upon to consistently vote against unionist candidates. That minimum winning coalition in Northern Ireland would inevitably be dominated by the large Catholic and nationalist voting bloc. The key to transformation then was for enough non-Catholic and non-nationalist voters to be willing to be part of such a coalition. It was the failure to construct such a minimum winning coalition despite substantial support for liberal and socialist ideas within the UUP support base that allowed the dominant party system to persist for so long after partition.

In this new context, majorities on constitutionally-sensitive issues remain as important, and perhaps more important, than ever before. Importantly, this new electoral majority is underpinned by a set of social cleavages which have produced new cross-cutting majorities: a socially liberal majority, a pro-remain majority, a majority in favour of stronger links with the Republic of Ireland, but also a majority wishing to remain in the UK. Rather than moving Northern Ireland beyond constitutional issues, this shift has profound long-term implications for the relationship between Northern Ireland on one hand and the Republic of Ireland and Great Britain on the other, opening up new avenues and possibilities for changes in constitutional arrangements, even if a majority continue to prefer to stay in the UK. The dominant party system and dominant bloc system are no more, but the quest to build stable majorities on constitutional issues and constitutional-relevant issues remains a central driving force of Northern politics.

The case highlights the curious continuities between the dominant party system and consociationalism as it operates in Northern Ireland. While consociationalism severely constrains the power of the dominant bloc it shares with the dominant party system a pattern of non-alternation of government, guaranteeing a leading role in government to the leading party within the dominant bloc. The case also offers some general insights into the relationship between dominant party systems and ethnic dual-party systems. The polarised character of the ethnic dual-party system produced strong pressures for cooperation within the unionist bloc, ensuring that some important features of the dominant party system were perpetuated in the form of a dominant bloc system in which the bloc was identified with the founding project of the state and the leading party in the bloc maintained a united front with satellite parties on crucial issues on an ongoing basis.

Acknowledgements

I am deeply grateful to Jennifer Todd for the inspiration provided by her imaginative and groundbreaking research over many years. It's a privilege to contribute to this special issue based on the 2018 conference to celebrate her work at which I first presented this paper. Many thanks to the reviewers for their suggestions, to Katy Hayward for her valuable feedback, and to Paul Mitchell for his detailed and very helpful suggestions for changes. I bear sole responsibility for any remaining errors or failings.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Niall Ó Dochartaigh

Niall Ó Dochartaigh is Personal Professor of Political Science and Sociology at the National University of Ireland Galway. He is the author of Deniable Contact: Back-channel Negotiation in Northern Ireland (Oxford University Press, 2021) and Civil Rights to Armalites: Derry and the Birth of the Irish Troubles (Cork University Press 1997; Palgrave, 2005).

Notes

1 That is, 8% of the vote that the Unionist candidate took in the by-election three years later when they faced a Northern Ireland Labour Party candidate.

2 The ‘backstop’ referred to the idea, eventually formalised in the original EU Withdrawal Agreement of 2018, that Northern Ireland would essentially remain in the European single market and subject to certain EU regulations when the UK left the EU. This was intended to avoid the sort of regulatory barriers between the two parts of Ireland that would create a ‘hard border’. The arrangement would only apply in the event that the EU and UK could not find agreement on alternative means to avoid a hard border.

3 The precise text of the question: ‘Here are some things that other people have said about the UK leaving the EU. How much do you agree or disagree with each of these statements? I would be in favour of Northern Ireland entering a political and economic alliance with the Republic of Ireland if it would help jobs and the economy’ (Source: Northern Ireland Life and Times survey: https://www.ark.ac.uk/nilt/2017/Political_Attitudes/NIROIALL.html; accessed 13 January 2021).

References

- Arian, A., & Barnes, S. H. (1974). The dominant party system: A neglected model of democratic stability. The Journal of Politics, 36(3), 592–614.

- Bew, P., Patterson, H., & Gibbon, P. (1979). The State in Northern Ireland 1921-1972: Political Forces and Social Classes. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Blondel, J. (1968). Party systems and patterns of government in Western democracies. Canadian Journal of Political Science, 1(2), 180–203.

- Bogaards, M. (2004). Counting parties and identifying dominant party systems in Africa. European Journal of Political Research, 43(2), 173–197.

- Buckland, P. (1986). Review of Graham S. Walker. The politics of frustration: Harry Midgley and the failure of Labour in Northern Ireland. Albion, 18(4), 727–728.

- Campbell, J. (2020, 3 June). Brexit: NI Assembly votes to extend transition period. BBC Northern Ireland News. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-northern-ireland-52906604

- Coakley, J. (2008). Ethnic competition and the logic of party system transformation. European Journal of Political Research, 47(6), 766–793.

- Crighton, E., & Iver, M. A. M. (1991). The evolution of protracted ethnic conflict: Group dominance and political underdevelopment in Northern Ireland and Lebanon. Comparative Politics, 23(2), 127–142.

- Duverger, M. (1959 [1951]). Political Parties: Their Organization and Activity in the Modern State. London: Methuen.

- Edwards, A. (2013). A History of the Northern Ireland Labour Party: Democratic Socialism and Sectarianism. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Emerson, N. (2020a, 26 March). Arlene Foster and Michelle O’Neill are a credible double act. The Irish Times. https://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/newton-emerson-arlene-foster-and-michelle-o-neill-are-a-credible-double-act-1.4212006

- Emerson, N. (2020b, 21 May). The real U-turn on a Brexit sea border has been by the DUP. The Irish Times. https://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/newton-emerson-the-real-u-turn-on-a-brexit-sea-border-has-been-by-the-dup-1.4258433

- Ferguson, A. (2016, 5 March). UUP to campaign against Brexit. The Irish Times. https://www.irishtimes.com/news/politics/uup-to-campaign-against-brexit-1.2561908

- Giliomee, H., & Simkins, C. (1999). The Awkward Embrace: One-Party Domination and Democracy. Amsterdam: Harwood.

- Hayward, K., & McManus, C. (2019). Neither/nor: The rejection of unionist and nationalist identities in post-agreement Northern Ireland. Capital & Class, 43(1), 139–155.

- Hennessey, T., Braniff, M., McAuley, J. W., Tonge, J., & Whiting, S. A. (2018). The Ulster Unionist Party: Country Before Party? Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kane, A. (2019, 16 December). Why demonising the Alliance Party as Sinn Fein fellow travellers backfired on DUP. The Belfast Telegraph. https://www.belfasttelegraph.co.uk/opinion/news-analysis/alex-kane-why-demonising-the-alliance-party-as-sinn-fein-fellow-travellers-backfired-on-dup-38789601.html

- Kaßner, M. (2013). The Influence of the Type of Dominant Party on Democracy: A Comparison Between South Africa and Malaysia. New York: Springer.

- Loughlin, C. J. V. (2018) Labour and the Politics of Disloyalty in Belfast, 1921–1939. New York: Springer.

- Mair, P. (1979). The autonomy of the political: The development of the Irish party system. Comparative Politics, 11(4), 445–465.

- Mair, P. (1996). Party systems and structures of competition. In L. N. LeDuc, G. Richard, & P. Norris (Eds.), Comparing Democracies: Elections and Voting in Global Perspective (pp. 83–106). London: Sage.

- McKeown, G. (2016, 1 November). All-island Dublin forum on Brexit to take place without Arlene Foster and DUP. The Irish News. https://www.irishnews.com/news/2016/11/02/news/all-island-dublin-brexit-forum-to-go-ahead-without-the-first-minister-765692/

- Mitchell, P. (1995). Party competition in an ethnic dual party system. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 18(4), 773–796.

- Mitchell, P. (1999). The party system and party competition. In P. Mitchell, & R. Wilford (Eds.), Politics in Northern Ireland (pp. 91–116). Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Mitchell, P., Evans, G., & O’Leary, B. (2009). Extremist outbidding in ethnic party systems is not inevitable: Tribune parties in Northern Ireland. Political Studies, 57(2), 397–421.

- Mitchell, P., O’Leary, B., & Evans, G. (2001). Northern Ireland: Flanking extremists bite the moderates and emerge in their clothes. Parliamentary Affairs, 54(4), 725–742.

- Moriarty, G. (2019, 9 November). North will be a ‘place apart’ under Brexit deal, new UUP leader says. The Irish Times. https://www.irishtimes.com/news/politics/north-will-be-a-place-apart-under-brexit-deal-new-uup-leader-says-1.4078106

- Moriarty, G. (2020, 2 June). Northern Assembly supports DUP motion on abortion. The Irish Times. https://www.irishtimes.com/news/ireland/irish-news/northern-assembly-supports-dup-motion-on-abortion-1.4269069

- Moriarty G. & McClements, F. (2020, 9 January). Stormont talks breakthrough: Simon Coveney and Julian Smith present new deal. The Irish Times. https://www.irishtimes.com/news/politics/stormont-talks-breakthrough-simon-coveney-and-julian-smith-present-new-deal-1.4134909

- Nolan, P., Bryan, D., Dwyer, C., Hayward, K., Radford, K., & Shirlow, P. (2014). The Flag Dispute: Anatomy of a Protest. Belfast: Queen’s University Belfast.

- O’Brien, G. (1999). Our Magee problem: Stormont and the new university. In G. O’Brien (Ed.), Derry and Londonderry: History and Society (pp. 647–696). Dublin: Geography Publications.

- Ó Dochartaigh, N. (1999). The politics of housing: Social change and collective action in Derry in the 1960s. In G. O’Brien (Ed.), Derry and Londonderry: History and Society (pp. 625–646). Dublin: Geography Publications.

- O’Leary, B. (2019). A Treatise on Northern Ireland, Volume III: Consociation and Confederation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- O’Leary, B., & McGarry, J. (1996). The Politics of Antagonism: Understanding Northern Ireland. London: Athlone Press.

- RTÉ (2018, 15 Nov). Northern Ireland's pro-remain parties hold ‘positive’ Brexit meeting with Taoiseach. RTÉ News. https://www.rte.ie/news/politics/2018/1115/1011105-brexit-northern-ireland-politics/

- Sartori, G. (1976). Parties and Party Systems: A Framework for Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Smyth, P. (2018, 5 October). North’s Remainer leaders warn against any DUP veto on backstop. The Irish Times. Retrieved from: https://www.irishtimes.com/news/politics/north-s-remainer-leaders-warn-against-any-dup-veto-on-backstop-1.3652959

- Tonge, J. (2020). Beyond unionism versus nationalism: The rise of the Alliance Party of Northern Ireland. The Political Quarterly, 91(2), 461–466.

- Walker, G. S. (1985). The Politics of Frustration: Harry Midgley and the Failure of Labour in Northern Ireland. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Whitten, L. C. (2020). Breaking walls & norms: A report on the UK general election in Northern Ireland, 2019. Irish Political Studies, 35(2), 313–330.