ABSTRACT

There is extensive CLIL research on stakeholders’ practices, integration of content and language, and pedagogies. However, limited studies report on teachers’ pre-existing knowledge before CLIL implementation and how it influences their classroom pedagogy. Using a third space frame, this study examined CLIL implementation in Kazakhstan. It included 15 science teachers who teach science through the English medium of instruction (EMI). A hybrid coding strategy was followed to analyze questionnaires, teachers’ science lessons, multimodal teaching-based scenarios, and semi-structured interviews. Our findings revealed that teachers’ CLIL implementation was guided by their (1) hybrid beliefs about scientific knowledge and learning, (2) humanising pedagogy, (3) shift to constructivist science pedagogy, and (4) hybrid linguistic stance. We conclude that a third-space perspective diverts the gaze from CLIL teachers’ challenges to illuminate the entanglement of teachers’ epistemic stance, pedagogical content knowledge (PCK), and linguistic stance as emergent discursive practices when policy borrowings connect global and local epistemologies.

Introduction

CLIL foregrounds the critical role of language in teaching content (Dalton-Puffer et al., Citation2010; Fung & Yip, Citation2014; Llinares & Morton, Citation2017). However, CLIL has been criticised as lacking ‘cohesion around CLIL pedagogy [as] there is neither one CLIL approach nor one theory of CLIL’ (Coyle, Citation2008, p. 101), raising questions about its nature and effective classroom implementation (Cenoz et al., Citation2014; Lorenzo et al., Citation2010; Ruiz de Zarobe & Cenoz, Citation2015). Despite these criticisms, CLIL remains popular in European countries, with macro-level studies advocating for its implementation and development (Banegas, Citation2012; Dalton-Puffer et al., Citation2010; Pavón & Ellison, Citation2013). These studies have shaped the positive views of CLIL, particularly among education authorities in Asian countries such as Japan, Thailand, and Kazakhstan that favour curriculum borrowing from the West (Karabassova, Citation2020, Citation2022; Kewara & Prabjandee, Citation2018; Mehisto et al., Citation2022; Tanaka, Citation2019; Tsuchiya, Citation2019).

There is extensive CLIL research on stakeholders’ practices, integration of content and language, and pedagogies (Banegas, Citation2020; Kewara & Prabjandee, Citation2018; Lo, Citation2019; McDougald & Pissarello, Citation2020). However, limited studies report on teachers’ pre-existing knowledge before CLIL implementation and how it influences their CLIL practices. For example, Kazakhstan was the first post-Soviet country to introduce CLIL requiring science teachers to teach in English (Karabassova, Citation2020, Citation2022). The dilemma is that teachers must now reconcile their Soviet education legacy with CLIL constructivist pedagogy through English medium instruction (EMI) and navigate their students’ Russian and Kazakh identities while figuring out how to integrate language and content. Therefore, exporting a CLIL curriculum to regions outside of Europe requires engagement with teachers’ linguistic and cultural backgrounds, their pedagogical histories, and epistemological viewpoints (Breeze & Legarre, Citation2021). For this reason, we argue that such teachers would probably experience CLIL reform like ‘a fish out of water’ (Bourdieu & Wacquant, Citation1992) and reimagine CLIL implementation as a third space (Bhabha, Citation1994) to bring into the conversation the local voice that might be silenced by a European perspective that can take ‘ for granted […] a particular conception of reason and knowledge’ (de Souza, Citation2014, p. 41).

Bhabha’s (Citation1994) third space theory holds significant relevance when CLIL is exported to non-European contexts, as it argues for an in-between space that is created when different cultures, identities, or ideologies intersect (Gutiérrez, Citation2008). This concept challenges rigid notions of identity and culture and advocates for the inclusion of marginalised voices and narratives to counter one-dimensional views. Such in-between spaces offer the potential for new meanings, ideas, and identities to emerge through interactions and negotiations between different values and beliefs. It also refutes binary categorisations such as coloniser/colonised or self/other and argues for the exploration of alternative possibilities (Bhabha, Citation1994; Soja, Citation1996). This makes the third space an appropriate lens for understanding the complexities and potential changes that emerge when CLIL leads to the flow and exchange of Western cultural ideas and ideologies (Appadurai, Citation1996).

In teacher education, it has shown promise in breaking down dichotomies between research and practice (Zeichner, Citation2010), in science education it offered a space to engage with the discursive boundaries between disciplinary and specialised contexts (Carlone et al., Citation2014; McKinley & Gan, Citation2014; Schuck et al., Citation2017) and in language education it merged students’ real-life contexts with school knowledge, creating a transformative space for ‘an expanded form of learning’ (Gutiérrez, Citation2008, p. 152). Consequently, it is a messy and lived space that embraces hybridity and diversity to offer an alternative narrative of how teachers navigate linguistic and cultural diversity (Bhabha, Citation1994; Gupta, Citation2020; Moje et al., Citation2004; Soja, Citation1996). However, a third space lens is unexplored in CLIL professional development (PD), which is unfortunate because it can (1) offer a sensemaking space about how teachers navigate their way toward CLIL implementation, (2) show how teachers in different geographical contexts are always in the process of being and becoming CLIL practitioners, and (3) offer a departure from deficit discourses about the gap between CLIL policy and teachers’ ineffective practice.

Purpose

CLIL research distinguishes between micro and macro studies, as well as process-oriented and product-oriented research (Dalton-Puffer, Citation2007; Dalton-Puffer et al., Citation2010). Micro studies report the language and content learning outcomes, while macro studies address broader implementation. Process-oriented studies analyze classroom discourse, while product-oriented studies examine final outcomes (Coyle et al., Citation2010; Dalton-Puffer, Citation2007, p. 181). This framework provides a comprehensive understanding of CLIL research, common themes across CLIL research is stakeholders’ beliefs, challenges, and how teachers integrate language and content (Dalton-Puffer et al., Citation2010). A similar thread is visible in the Kazakhstani CLIL research that mostly foregrounded teachers’ perspectives, and implementation challenges (Kanayeva, Citation2019; Karabassova, Citation2020, Citation2022; Mehisto et al., Citation2022). We look beyond this narrow focus, using a third space lens to illustrate Kazakhstani teachers’ boundary crossing into what is essentially a European approach and to reveal the points of intersection to shift from measuring Kazakhstani STEM teachers against a narrow European CLIL yardstick (García, Citation2009). Thus, we pose the research question below:

What are Kazakhstani science teachers’ responsive pedagogies when they navigate CLIL/EMI in their biology classrooms?

Exploring CLIL literature: focus and its gaps

CLIL has become an essential ‘part of European language policy’ (Lopriore, Citation2020, p. 99); the EU Action Plan for Language Learning and Linguistic Diversity (Citation2003, p. 8) states that CLIL makes ‘a major contribution to the Union's language learning goals’ and that successful implementation requires ‘trained teachers who are native speakers of the vehicular language’. However, the previous statement may inadvertently present a monolingual view that favours ‘the target language only’ or ‘one language at a time’ ideology, which could silence the diverse multilingual identities of teachers in Asia (Lin & He, Citation2017, p. 237). Unsurprisingly, teachers have mentioned the need for improvement in their general linguistic competence and their pronunciation (Pérez Cañado, Citation2016; Yildiz, Citation2019). This emphasises the risk of teachers developing deficit identities regarding their language proficiency, potentially overshadowing their pedagogical content knowledge (PCK) which the unique knowledge and understanding that teachers need to effectively teach a specific subject (Shulman, Citation1986).

Interestingly, An et al. (Citation2021) cast doubt on the native language proficiency factor; they argue that ‘teachers’ high English proficiency alone is insufficient’ to promote students’ engagement in science education. The reality of multilingual classrooms contradicts monolingual assumptions, ‘pedagogical straitjackets’, or ‘multilingualism through parallel monolingualisms’ (Lin, Citation2015, pp. 75–76; Lin & He, Citation2017; Pavón & Ellison, Citation2013). For this reason, translanguaging has gained prominence in CLIL research (Cenoz & Gorter, Citation2017; Lin & He, Citation2017; Nikula & Moore, Citation2019). Gierlinger's (Citation2015) longitudinal study in Austrian secondary schools found that teachers’ use of the students’ first language (L1) served both a regulatory and instructional purpose, facilitating the students’ understanding of content and language. However, there is a gap in CLIL research regarding how PCK informs their intentional translanguaging about strategically planning their multilingual pedagogy move from a multilingual safe zone to support learner development across various contexts and registers (Van Viegen & Zappa-Hollman, Citation2020).

When CLIL is exported to other developing countries, it is often a foreign language for teachers and their students (Dearden, Citation2014), which can perpetuate the ‘native speaker fallacy’ that diverts ‘attention from the flourishing […] local pedagogical initiative’ (Phillipson, Citation1992, p. 199). In this way, the PCK, epistemic stance, and unique linguistic resources of non-native English-speaking teachers (NNEST) can be seen as worthless (Canagarajah, Citation2013). For this reason, CLIL exportation requires a critical lens to decipher how it ‘is continually interpreted and discursively constructed by policymakers and practitioners’ (Darvin et al., Citation2020, p. 103), because CLIL is not neutral, it carriers specific historical, cultural, and political orientations from a particular geographical context.

Several researchers in Asia have reported on teachers’ linguistic competence, CLIL classroom interactions, and translanguaging (Liu, Citation2020; Maxwell-Reid & Lau, Citation2016; Pun & Tai, Citation2021; Tai & Wei, Citation2020). It is noteworthy that they report on how translanguaging practices ‘reshape power relations [in] the process of teaching and learning to focus on meaning-making and identity development’ (Li, Citation2018, p. 15). Liu (Citation2020) illustrates how power relations changed when teachers in the study challenged official monolingual norms when they resisted the use of one language to facilitate meaningful engagement with their students. In Shanghai, Zhou (Citation2021) showed that translanguaging between students’ L1 and the target language facilitated task management, scaffolding, and conceptual clarification. Morton (Citation2018) illustrated that teachers’ limited language skills shifted the power imbalance between teachers and learners because they openly admitted that they did not ‘have the faintest idea’ about certain language aspects and that they dealt with gaps in ‘a practical way’ and integrated into ‘ongoing, content-focused discussions’ (p. 283). Therefore, teachers and learners use their linguistic diversity as valuable identity resources to ‘connect new language forms with students’ existing semantic knowledge in their L1’ (Calafato, Citation2019, p. 14). However, the knowledge of language as a semiotic resource to scaffold disciplinary content and provide access to ‘language/s of power’ is often overlooked (Heugh et al., Citation2017, p. 197; Francomacaro, Citation2019).

Even though there is a growing interest in CLIL research in non-European contexts about the integration of content and language, stakeholders’ beliefs, and CLIL challenges (Banegas, Citation2020; Kewara & Prabjandee, Citation2018; McDougald & Pissarello, Citation2020), there is limited research on how science teachers’ prior pedagogy shape their preparedness for CLIL implementation (Hedges, Citation2012). Numerous studies have merely reported on teachers’ insufficient knowledge of the CLIL hindering its effective implementation (Banegas, Citation2012; Karabassova, Citation2020; Citation2022) which increased calls for CLIL PD to develop teachers’ instructional techniques, scaffolding strategies, and assessment practices (Cammarata & Haley, Citation2018; Francomacaro, Citation2019; Lo, Citation2019, Citation2020; McDougald & Pissarello, Citation2020). However, such an approach has a tabula rasa underpinning because teachers’ pedagogical practices before CLIL is ignored, constituting cognitive injustice and silencing the local epistemology (Santos, Citation2014), especially in post-Soviet contexts like Kazakhstan.

Kazakhstani educational reform context

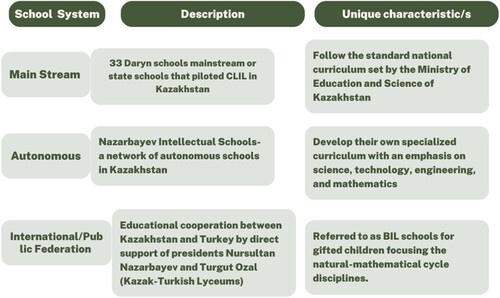

Kazakhstan's population consists mainly of Kazakhs (63%) and Russians (23.7%) (MoES, Citation2015), with Russian being the unifying language during the Soviet era (Smagulova, Citation2008). To enhance education and human capital, Kazakhstan adopted a trilingual language policy in 2007, recognising Kazakh and introducing English (MoES, Citation2015). The education system reflects this linguistic diversity, with schools using Kazakh, Russian, a combination of both, or EMI. Kazakhstan's CLIL context (see ) is interesting due to the different school models, such as Nazarbayev Intellectual Schools (NIS) system, which serves as a roadmap for state schools (MoES, Citation2015). However, this may lead to a deficit discourse about CLIL practices in state schools, despite their unique contextual conditions. Therefore, Kazakhstani teachers work under strict policy reforms such as teaching CLIL through EMI and we argue that CLIL requires a radical reorientation about ‘what counts as responsive and effective education, [and] what counts as appropriate teaching’ (Apple, Citation2011, p. 223).

Research method

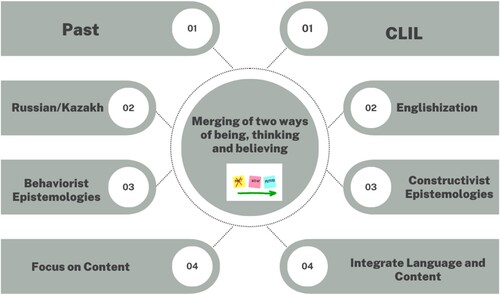

This paper is part of a larger research project that examined Kazakhstani science teachers’ metalinguistic knowledge to design a 45-hour PD. The project involved three phases of data collection: before, during, and after PD. We used a case study design to report on the data collected before the PD to provide ‘an intensive, holistic description and analysis’ (Merriam, Citation1998, p. xiii) of the emergent practices when global and local epistemologies merge. illustrates why educational reform requires rethinking teachers’ values and beliefs about science pedagogy, language, and how learners learn. A third space is important because little is known about their prior professional funds of knowledge and it can reveal the ‘kinds of assumptions [and] unchallenged, unconsidered modes of thoughts’ (Foucault, Citation1980, p. 154) that influence teachers’ pedagogical reasoning when they implement CLIL (Hedges, Citation2012).

Research design

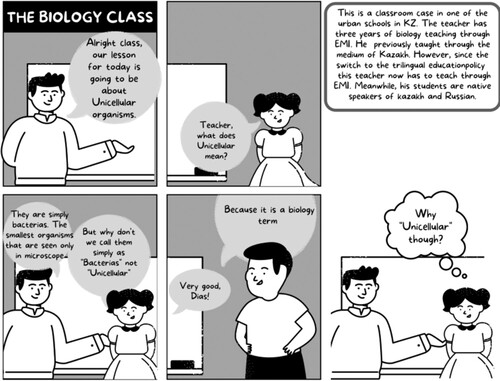

After obtaining ethical approval, we purposively selected 11 schools in Kazakhstan (state and private) to address the research gap in implementing CLIL in these schools. Fifteen experienced EMI biology teachers (mostly female) from grades five to ten were recruited. For this paper, we draw on multiple data sets collected prior to our PD, which included questionnaires, lesson descriptions, reflections on classroom scenarios, and online interviews, were collected to explore teachers’ backgrounds, experiences, linguistic orientations, and content and language integration. is an example of one of our multimodal tools to map instructional scenarios and gain insights into teachers’ beliefs, and CLIL pedagogy.

To ensure the credibility of the study, several strategies were employed. Firstly, the participants engaged in a 45-hour PD course, allowing for prolonged interaction, observation of their learning processes, and cross-checking of their statements through PD presentations. Secondly, the multiple datasets underwent multiple examinations by the research team to uphold validity and rigour (Jansen, Citation2022; Merriam, Citation1998).

Data analysis

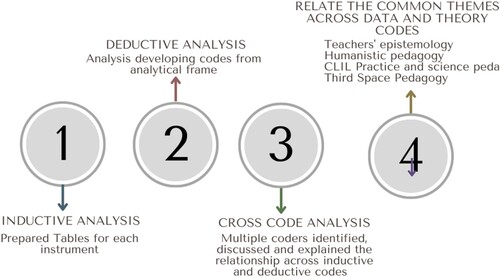

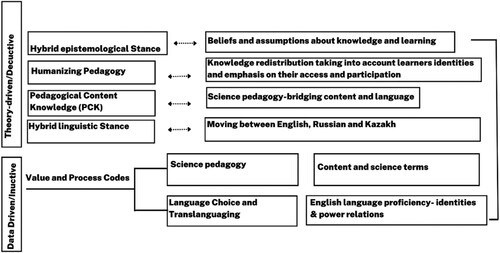

Using a hybrid coding strategy (), we applied both deductive and inductive coding processes to ensure validity and reliability (Jansen, Citation2022). In data-driven inductive coding, the lead researcher and three research assistants coded the different data sets individually and identified value and process codes related to teachers’ responsive CLIL pedagogy (Patton, Citation2014; Yin, Citation2009). Theory-based codes were also generated that focused on epistemology, pedagogy, and the integration of language and content. Through team discussion and code refinement, similar codes were grouped under relevant themes to ensure inter-coder reliability and validity and to mitigate the risk of confirmation bias (Cousin, Citation2005). Finally, a matrix () was created to visually represent the recurring themes and patterns in teachers’ responsive science/CLIL pedagogy.

The cross-code synthesis indicated that teachers’ CLIL implementation was guided by their (1) hybrid beliefs about scientific knowledge and learning, (2) science knowledge redistribution demonstrated humanising pedagogy, (3) shift to constructivist science pedagogy, and (4) hybrid linguistic stance ().

Results

The third space frame showcased Kazakhstani science teachers negotiating their previous professional knowledge and CLIL reform, leading to new ways of practicing and embodying science (Moje et al., Citation2004). It demonstrated a dynamic site where teachers are continuously emerging, reshaping, and transitioning, constantly evolving as CLIL practitioners (Recchia & McDevitt, Citation2018). Our results emphasised that despite the rapid shifts in language and science pedagogy, teachers relied on their hybrid epistemic stance, humanising pedagogy, flexible language stance, and professional identities as valuable resources to implement CLIL lessons.

Hybrid epistemic stance: beliefs about science knowledge and learning

Teachers’ epistemic stance shows hybridity because their beliefs combine multiple perspectives about science knowledge and learning. For example, they believe that science teachers must be the authority on subject matter,

Here, it looks like the teacher does not know the topic himself. The students ask something, the teacher cannot explain properly. So actually, teachers have to get prepared for the class beforehand. [Teacher 1]

He didn’t explain why it is ‘Unicellular' nor why it is the term for bacteria. I think that he also has some difficulties with his knowledge of Biology. He must explain why it is ‘unicellular' because all organisms are divided into multicellular. He must give examples for every part of these cells, and why we call them auxiliary. [Teacher 10]

Another thing I noticed is that the teacher does not say that he does not know the answer. In my opinion, it is OK to say ‘I don’t know’ and to ask students to find the answer together. In this way, the teacher will know and the students, too. [Teacher 2].

If we talk about unicellular organisms, we would show not only bacteria but also other types of unicellular organisms, and importantly ask questions: why do you think we call them unicellular? But the teacher is not asking just questions and he should have been more specific for his students to understand. [Teacher 5]

Here it looks like the students are just answering the questions but the teacher keeps it short and does not push the students further. I think the teacher needed to think and plan for how prepared his students were, and what they know. [Teacher 13]

Science knowledge redistribution as a humanising pedagogy

Kazakhstani teachers apply a humanising pedagogy when they include students’ linguistic repertoires, identities, and background knowledge to access content (Fataar, Citation2016). Their humanising pedagogy prioritises the needs of learners and goes beyond official guidelines because they challenge power imbalances, build close relationships with students, and adapt science knowledge to students’ linguistic and academic needs. For example, teachers commented,

Our principal encourages us to use Kazakh more if we want to explain something not in English since it is a Kazakh school. I have tried it, and I have explained the word ‘жасуша' and my students were confused. I do what is best for my learners and make them comfortable to speak to me or tell me when they don’t understand. [Teacher 8]

I don’t know if NIS maybe they teach in pure English but in mainstream schools, such as ours, you can’t teach purely in English because of the science content. Even if you know English, you anyway should explain in Kazakh because they must understand the content. So, you will say it in English a bit but will go back to Kazakh so all students will understand. [Teacher 12]

The most important thing is to make sure that my students get the knowledge about the topic, not only to show them videos and teach. I want my students to understand the subject and want them to be able to explain it in English. For this reason, using the Russian and Kazakh languages helps me to make a bridge between what they know and the new science knowledge. [Teacher 6]

Furthermore, they have transcended the ‘Garden of Eden view’ (Samuel, Citation2009, p. 750) by accepting linguistic imperfections and appreciating their students’ linguistic ‘repertoires as valuable resources’ (Moore et al., Citation2018, p. 348).

I offer my subject in an appropriate language and use all the language flexibly for my learners to feel comfortable and free to speak in their language. I do this because I do not want to make them nervous about making mistakes. [Teacher 2]

We all struggle with English, they hear my mistakes and they know it is ok. The important thing is that students at least leave the class with new knowledge. [Teacher 11]

Consequently, teachers recognised the importance of language in fostering inclusivity, blurring power dynamics, and encouraging collaboration. Thus, a third space lens revealed a humanising (inclusive) pedagogy utilising students’ bilingual identities to promote positive socio-emotional, cognitive, and academic growth (Fataar, Citation2016).

Science pedagogy: ways of bridging content and language

When the lens shifted from measuring teachers’ CLIL practices, we could see teachers’ pedagogical reasoning skills and values that underpin their science teaching. The results showed teachers’ PCK in action: they explained how they transform the content and were flexible in classroom communication and science pedagogy.

Before starting the lesson, I would first open the topic, raise a question, show a picture, or show a video to make students think. In that way, students themselves will reveal the topic of the lesson or give their variants of possible topics. [Teacher 9]

If it’s a hard topic then I will first little explain it, but if it is a simple topic, I first give them tasks and students do those tasks, and then they reveal the topic. Or I can first explain them and then give them tasks. It depends on the situation. That’s how we give tasks, but even after giving the tasks I additionally check, and after checking we discuss this topic with students. [Teacher 15]

Students are often talking about their opinions; I listen to them so that they become more competent in the topic. For example, they learn the weight of the heart or the number of beats per minute, and all of these create an interest. After that, I work on terminology words and key terms. This is essential. I give these in English, Kazakh and Russian. [Teacher 6]

There could be very difficult topics such as photosynthesis. I find myself explaining in English but eventually, you need to continue in Russian so that the students can understand the subject. [Teacher 4]

I work on terminology and key terms; it is essential. I give these in English, Kazakh and Russian. We are making it because our school is a Kazakh-English school, and our students are Russian fluent, so we need to give them information in all three languages. [Teacher 10]

We repeat new words, translate with students, repeat them with the key terms, and definitions, the terms are provided, and the meaning of the terms are given, and we read them. Then we move to the topic itself. [Teacher 7]

I provide new vocabulary before the class using slides or some activities to practice. We translate new vocabulary at the beginning of any class and discuss them. I try to explain it with easy words. I try to use this option all the time instead of translations. [Teacher 11]

English language proficiency, identities, and power

Despite their limited English language proficiency, teachers did not experience their authority and professional identities under threat. For example, when dealing with their learners’ hybrid identities, teachers seem to continuously reinvent themselves to accommodate their students’ needs and to develop their own and their students’ language proficiency (Beauchamp & Thomas, Citation2009).

I know my English level is not that high, but I try to speak only English in my classes. I try because it is an explanation of the topic for me and the understanding of students about this topic. Sometimes it is a problem, a problem for both of us. [Teacher 8]

I can express my thoughts in English, but sometimes I forget how to spell; therefore, it goes in the Kazakh language. The students have the same situation when we use those words; you can sometimes forget them, but we try to use them more. [Teacher 1]

For me personally it is preferable to give an explanation in Russian. It is much easier for students. For me personally it is easier to use Kazakh rather than other languages. Interestingly, students prefer the Russian language more. [Teacher 10]

Sometimes I also have some problems when my English seems not enough because some students have studied in America, or transferred from private schools. I hesitate to speak them but then I remember I am teaching them new knowledge. When I get stuck I ask these students to help me, the Russian and Kazakh speaking students help them in other classes and so we all feel that we learn from each other. [Teacher 5]

Although teachers faced contextual complications in their teaching contexts, a third space lens illustrated their professional identities as mobile and flexible. Despite their limited English proficiency, teachers did not see their authority or professional identities threatened. English language challenges blur power and authority as teachers seek to build their self-confidence while creating a safe space to reduce anxiety for themselves and their students. Consequently, language played a critical role in cultivating an appropriate and supportive environment.

Discussion and conclusion

This paper framed Kazakhstani CLIL implementation as a third space, which challenged our initial assumptions about STEM teachers’ needs. Through engagement with pre-PD data, an unexpected narrative unfolded, highlighting teachers’ responses to CLIL reform. The third space offered a transformative realm where teachers’ local knowledge and diverse experiences connected their old and new approaches. It revealed the potential for meaning-making as Kazakhstani teachers embraced their cultural and linguistic hybridity, merging European CLIL and Soviet-style science education. Thus, the third space provided an alternative window into the responsive pedagogy of teachers as ‘missing links, […] absent knowledges […] or silenced agents [giving access to] an epistemology of absences’ (Santos, Citation2014, p. 154). Based on our findings, we believe this article uncovered the potential of a third-space perspective to divert the gaze from CLIL teachers’ challenges to illuminate the entanglement of teachers’ epistemic stance, PCK, and linguistic stance as emergent discursive practices when policy borrowings connect global and local epistemologies. Consequently, we found that teachers are currently in an in between space resulting in hybrid expressions of science teaching and learning.

First, a third space revealed that our participants’ funds of knowledge and professional identities should not be discarded as inappropriate ‘baggage or pathologies’ (Samuel, Citation2009, p. 749). For example, their hybrid epistemic stance shows their shift from a teacher-centred, authority of knowledge and didactic instruction to ‘I noticed is that the teacher does not say that he does not know the answer to this question. In my opinion, it is OK to say I don’t know’ when you don't know’. Even though, a third space revealed that their epistemic stance did not entirely represent the European CLIL, it illustrated that they are going through a process of reevaluating their teaching methods and taking initial steps of transitioning from traditional didactic approaches to a constructivist perspective (Iranmehr & Davari, Citation2017; Moodie, Citation2016; Soleimani, Citation2020). Any CLIL PD outside of Europe needs to engage with teachers’ epistemic stance to open a reflective space about how prior knowledge connects new CLIL learning, rather than ignoring or discarding their professional identities (Gupta, Citation2006, Citation2020; Recchia & McDevitt, Citation2018). Therefore, we need a CLIL PD model that encourages a shift from binary explanations on the policy-practice divide to engage with local funds knowledge and ‘practice-based evidence’ that question established norms while embracing diversity, and integrating theory-building with local teachers’ practice (Fox, Citation2003, p. 81; Santos, Citation2014).

Second, a third space revealed a social constructivist relationship between participants’ hybrid epistemic stance, their pedagogical beliefs, and their PCK, which is the ‘special amalgam of content and pedagogy [and] special form of professional understanding’ (Shulman, Citation1986, p. 8). They were able to think beyond the official CLIL prescriptions-strong evidence of how their PCK functions as a resource for CLIL implementation. However, the PCK of Kazakhstani science teachers was silenced and marginalised, resulting in the invisibility and devaluation of the diverse local funds of knowledge (Mehisto et al., Citation2022; Santos, Citation2014). We argue for an ontological shift in CLIL PD to create inclusive and socially just spaces for teachers to explore and engage with the transformative impact of CLIL on their epistemic and pedagogical beliefs (Gupta, Citation2020). Based on our findings, therefore, we argue against native English as the predominant benchmark for instruction because it creates conditions in which English competence is ‘valued over professional qualifications and experience’ (Yazan, Citation2018, p. 2). We argue that a third space can create more inclusive and socially just spaces for teachers to explore and grapple with how CLIL changes their epistemic and pedagogical beliefs (Gupta, Citation2020). In the Kazakh context, a CLIL PD model should include reflexivity for teachers to think about issues of hybridity and explore how local practices contribute to navigating or transitioning to the proposed new space.

A third notable finding was how teachers employed humanising and hybrid linguistic practices that demonstrate their awareness that the ‘cognitive and affective elements of human lives and learning’ cannot be considered inseparable from their teaching (Hedges, Citation2012, p. 12). We did not find rigid power relations as language practices resulted in negotiated communication between learners and teachers and between learners and learners who helped each other understand and translate, each being a linguistic resource. Our participants used all the languages available to them to navigate their CLIL pedagogy; language hybridity acted as a resource to redefine linguistic boundaries and their science pedagogy. Our findings support Morton (Citation2018), who found that teachers talked openly about when ‘they do not have the faintest idea’ about certain aspects of language, that gaps were managed in ‘practical ways’, and that they were ‘quickly integrated into ongoing, content-focused discussions’ (p. 283). Therefore, the lens of the third space shatters the narrative of Kazakhstani teachers’ English problem and argues for addressing NNEST professional identities and funds of knowledge at the margins (Lin & He, Citation2017, p. 237; Tao & Gao, Citation2021). Consequently, our findings are consistent with research on CLIL settings outside Europe, which argues that teachers’ language proficiency does not lead to ‘pedagogical straitjackets’ or ‘multilingualism through parallel monolingualisms’ (Lin, Citation2015, pp. 75–76; Lin & He, Citation2017; Pavón & Ellison, Citation2013).

Finally, our findings are consistent with those of An et al. (Citation2021), who questioned the importance of ‘English proficiency’ in promoting student engagement (p. 9). They emphasised the need for teachers to possess specialised knowledge about language as a semiotic resource. While our participants were concerned about their English language proficiency, multilingualism served as a pedagogical boundary strategy but fell short in scaffolding disciplinary language and science literacies (Heugh et al., Citation2017). This suggests that they did not have the knowledge to address science language and literacies (Block & Moncada-Comas, Citation2022). Nonetheless, our teachers demonstrated intentionality, scaffolding, and a constructivist paradigm in implementing CLIL, indicating that their pedagogical knowledge (PK) and PCK were more important than CLIL methods. However, our results are consistent with research findings that a language as a social semiotic model is necessary for teachers to make the STEM register explicit in order to expand students’ language awareness, scientific thinking, and problem-solving skills (Francomacaro, Citation2019; Lo, Citation2019). In summary, reimagining CLIL as a third space, we aimed to include the rich diversity of local knowledge that is often ignored when policymakers are unable to recognise the limitations of dominant forms of Eurocentric thinking, which seemed to be the case in Kazakhstan (de Souza, Citation2014). To support and leverage teachers’ science pedagogy, we recommend:

Kazakh teachers’ PCK and science habitus, epistemic stance and pedagogical beliefs be used as leverage to extend their pedagogies and philosophies in CLIL PD.

Specific PD about the language of science and science disciplinary literacies to implement CLIL effectively.

Science translanguaging pedagogies.

Limitations

Although a third space lens revealed some striking results, a limitation of our study is the inclusion of data from teachers’ practice. Due to COVID-19 restrictions, the team could not observe teachers in practice to understand their CLIL pedagogies in situ. Despite its limitations, the study offers valuable insights into teachers’ CLIL pedagogy and highlights the need to consider contextual factors when local and global discourses merge.

Geolocation

51.0906920079056, 71.3983684459067.

Acknowledgements

We want to acknowledge the teacher participants who willingly shared their experiences and practices with the research team.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

All data is available by emailing the author.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- .). Adilet.zan.kz. .

- Action Plan for Language Learning and Linguistic Diversity. (2003). Retrieved October 10, 2011, from http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2003:0449:FIN.

- An, J., Macaro, E., & Childs, A. (2021). Classroom interaction in EMI high schools: Do teachers who are native speakers of English make a difference? System, 98, 102482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2021.102482

- Appadurai, A. (1996). Modernity at large: Cultural dimensions of globalization. University of Minnesota Press.

- Apple, M. W. (2011). Global crises, social justice, and teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 62(2), 222–234. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487110385428

- Banegas, D. L. (2012). CLIL teacher development: Challenges and experiences. Latin American Journal of Content and Language Integrated Learning, 5(1), 46–56. https://doi.org/10.5294/laclil.2012.5.1.4

- Banegas, D. L. (2020). Content knowledge in English language teacher education. Bloomsbury. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350084650

- Beauchamp, C., & Thomas, L. (2009). Understanding teacher identity: An overview of issues in the literature and implications for teacher education. Cambridge Journal of Education, 39(2), 175–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057640902902252

- Bhabha, H. (1994). The location of culture. Blackwell.

- Block, D., & Moncada-Comas, B. (2022). English-medium instruction in higher education and the ELT gaze: STEM lecturers’ self-positioning as NOT English language teachers. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 25(2), 401–417. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2019.1689917

- Bourdieu, P., & Wacquant, L. (1992). An invitation to reflexive sociology. Polity.

- Breeze, R., & Legarre, M. P. A. (2021). Understanding change in practice: Identity and emotions in teacher training for content and language integrated learning (CLIL). International Journal of Language Studies, 15(3), 25–44.

- Calafato, R. (2019). The non-native speaker teacher as proficient multilingual: A critical review of research from 2009–2018. Lingua, 227, 102700. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2019.06.001

- Cammarata, L., & Haley, C. (2018). Integrated content, language, and literacy instruction in a Canadian French immersion context: A professional development journey. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 21(3), 332–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2017.1386617

- Canagarajah, A. S. (2013). Interrogating the “native speaker fallacy”: Non-linguistic roots, non-pedagogical results. In G. Baine (Ed), Non-native educators in English language teaching (pp. 77–92). Routledge.

- Carlone, H. B., Johnson, A., & Eisenhart, M. (2014). Cultural perspectives in science education. In N. G. Lederman, & S. K. Abell (Eds.), Handbook of research on science education, (pp. 2069–2135). Routledge.

- Cenoz, J., Genesee, F., & Gorter, D. (2014). Critical analysis of CLIL: Taking stock and looking forward. Applied Linguistics, 35(3), 243–262. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amt011

- Cenoz, J., & Gorter, D. (2017). Minority languages and sustainable translanguaging: Threat or opportunity? Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 38(10), 901–912. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2017.1284855

- Cousin, G. (2005). Case study research. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 29(3), 421–427. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098260500290967

- Coyle, D. (2008). CLIL – A pedagogical approach from the European perspective. In N. H. Hornberger (Ed.), Encyclopedia of language and education, (pp. 1200–1214). Springer.

- Coyle, D., Hood, P., & Marsh, D. (2010). CLIL: Content and language integrated learning. Cambridge University Press.

- Dalton-Puffer, C. (2007). Discourse in content and language integrated learning (CLIL) classrooms. John Benjamins.

- Dalton-Puffer, C., Nikula, T., & Smit, U. (2010). Language use and language learning in CLIL classrooms. John Benjamins Publishing.

- Darvin, R., Lo, Y. Y., & Lin, A. M. (2020). Examining CLIL through a critical lens. English Teaching & Learning, 44(2), 103–108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42321-020-00062-2

- Dearden, J. (2014). English as a medium of instruction – A growing global phenomenon. https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:4f72cdf8-b2eb-4d41-a785-4a283bf6caaa.

- de Souza, L. M. (2014). Epistemic diversity, lazy reason, and ethical translation in postcolonial contexts: The case of indigenous educational policy in Brazil. Interfaces Brasil/Canadá. Canoas, 14(2), 36–60.

- Fataar, A. (2016). Towards a humanising pedagogy through an engagement with the social-subjective in educational theorising in South Africa. Educational Research for Social Change, 5(1), 10–21. https://doi.org/10.17159/2221-4070/2016/v5i1a1

- Foucault, M. (1980). Power/knowledge: Selected interviews and other writings. (C. Gordon, ed.) Pantheon.

- Fox, N. J. (2003). Practice-based evidence: Towards collaborative and transgressive research. Sociology, 37(1), 81–102. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038503037001388

- Francomacaro, M. R. (2019). The added value of teaching CLIL for ESP and subject teachers. International Journal of Language Studies, 13(4), 55–72.

- Fung, D., & Yip, V. (2014). The effects of the medium of instruction in certificate-level physics on achievement and motivation to learn. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 51(10), 1219–1245. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21174

- García, O. (2009). Education, multilingualism, and translanguaging in the 21st century. In A. Mohanty, M. Panda, R. Phillipson, & T. Skutnabb-Kangas (Eds.), Multilingual education for social justice: Globalising the local (pp. 128–145). Orient Blackswan.

- Gierlinger, E. (2015). ‘You can speak German, sir’: On the complexity of teachers’ L1 use in CLIL. Language and Education, 29(4), 347–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2015.1023733

- Gupta, A. (2006). Early experiences and personal funds of knowledge and beliefs of immigrant and minority teacher candidates dialog with theories of child development in a teacher education classroom. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 27(1), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/10901020500534224

- Gupta, A. (2020). Preparing teachers in a pedagogy of Third Space: A postcolonial approach to contextual and sustainable early childhood teacher education. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 34(1), 43–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/02568543.2019.1692108

- Gutiérrez, K. D. (2008). Developing a sociocritical literacy in the third space. Reading Research Quarterly, 43(2), 148–164. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.43.2.3

- Hedges, H. (2012). Teachers’ funds of knowledge: A challenge to evidence-based practice. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 18(1), 7–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2011.622548

- Heugh, K., Prinsloo, C., Makgamatha, M., Diedericks, G., & Winnaar, L. (2017). Multilingualism (s) and system-wide assessment: A southern perspective. Language and Education, 31(3), 197–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2016.1261894

- Iranmehr, A., & Davari, H. (2017). English language education in Iran: A site of struggle between globalized and localized versions of English. Iranian Journal of Comparative Education, 1(2), 70–84.

- Jansen, D. (2022). Qualitative data coding: Explained simply. https://gradcoach.com/qualitative-data-coding-101.

- Kanayeva, G. (2019). Developing teacher leadership in Kazakhstan. International Journal of Teacher Leadership, 10(1), 53–64.

- Karabassova, L. (2020). understanding trilingual education reform in Kazakhstan: Why is it stalled? In D. Egéa (Ed), Education, Equity, Economy,: Education in Central Asia A Kaleidoscope of Challenges and Opportunities, (pp. 37–51). Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-50127-3_3

- Karabassova, L. (2022). Is top-down CLIL justified? A grounded theory exploration of secondary school science teachers’ experiences. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 25(4), 1530–1545. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2020.1775781

- Kewara, P., & Prabjandee, D. (2018). CLIL teacher professional development for content teachers in Thailand. Iranian Journal of Language Teaching Research, 6(1), 93–108.

- Li, M. (2018). The effectiveness of a bilingual education program at a Chinese university: A case study of social science majors. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 21(8), 897–912. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2016.1231164

- Lin, A. M. Y. (2015). Conceptualising the potential role of L1 in CLIL. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 28(1), 74–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2014.1000926

- Lin, A. M. Y., & He, T. (2017). Translanguaging as dynamic activity flows in CLIL classrooms. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 16(4), 228–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2017.1328283

- Liu, Y. (2020). Translanguaging and trans-semiotizing as planned systematic scaffolding: examining feeling-meaning in CLIL classrooms. English Teaching Learning, 44(2), 149–173. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42321-020-00057-z

- Llinares, A., & Morton, T. (2017). Applied linguistics perspectives on CLIL. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Lo, Y. Y. (2019). Development of the beliefs and language awareness of content subject teachers in CLIL: Does professional development help? International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 22(7), 818–832. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2017.1318821

- Lo, Y. Y. (2020). Professional development of CLIL teachers. Springer.

- Lopriore, L. (2020). Reframing teaching knowledge in Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL): A European perspective.

- Lorenzo, F., Casal, S., & Moore, P. (2010). The effects of content and language integrated learning in European education: Key findings from the Andalusian bilingual sections evaluation project. Applied linguistics, 31(3), 418–442.

- Maxwell-Reid, C., & Lau, K. (2016). Genre and technicality in analogical explanations: Hong Kong’s English language textbooks for junior secondary science. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 23, 31–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2016.05.005

- McDougald, J. S., & Pissarello, D. (2020). Content and language integrated learning: In-service teachers’ knowledge and perceptions before and after a professional development program Íkala. Revista De Lenguaje y Cultura, 25(2), 353–372. https://doi.org/10.17533/udea.ika-la.v25n02a03

- McKinley, E., & Gan, M. J. S. (2014). Culturally responsive science education for indigenous and ethnic minority students. In N. G. Lederman, & S. K. Abell (Eds.), Handbook of research on science education, (pp. 298–314). Routledge.

- Mehisto, P., Winter, L., Kambatyrova, A., & Kurakbayev, K. (2022). CLIL as a conduit for a trilingual Kazakhstan. The Language Learning Journal, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2022.2056627

- Merriam, S. B. (1998). Qualitative research and case study applications in education. Jossey-Bass Publishers.

- MOES. (2015). The roadmap of trilingual education for 2015–2020. http://www.kafu.kz/en/academic-programs/3langeduen/roadmap-of-trilingual.

- Moje, E. B., Ciechanowski, K., Kramer, K., Ellis, L., Carrillo, R., & Collazo, T. (2004). Working toward third space in content area literacy: An examination of every day funds of knowledge and discourse. Reading Research Quarterly, 39(1), 38–70. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.39.1.4

- Moodie, I. (2016). The anti-apprenticeship of observation: How negative prior language learning experience influences English language teachers’ beliefs and practices. System, 60, 29–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2016.05.011

- Moore, E., Evnitskaya, N., & Ramos-de Robles, S. L. (2018). Teaching and learning science in linguistically diverse classrooms. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 13(2), 341–352.. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-016-9783-z

- Morton, T. (2018). Reconceptualizing and describing teachers’ knowledge of language for content and language integrated learning (CLIL). International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 21(3), 275–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2017.1383352

- Nikula, T., & Moore, P. (2019). Exploring translanguaging in CLIL. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 22(2), 237–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2016.1254151

- Patton, M. Q. (2014). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice. Sage Publications.

- Pavón, V., & Ellison, M. (2013). Examining teacher roles and competencies in content and language integrated learning (CLIL). Linguarum Arena, 4, 65–78. https://ler.letras.up.pt/uploads/ficheiros/12007.pdf.

- Pérez Cañado, M. L. (2016). Teacher training needs for bilingual education: In-service teacher perceptions. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 19(3), 266–295. https://doi.org/10.1080/13

- Phillipson, R. (1992). Linguistic imperialism. Oxford University Press.

- Poza, L. (2017). Translanguaging: Definitions, implications, and further needs in burgeoning inquiry. Berkeley Review of Education, 6(2), 101–128. https://doi.org/10.5070/b86110060

- Pun, J. K. H., & Tai, K. W. H. (2021). Doing science through translanguaging: A study of translanguaging practices in secondary English as a medium of instruction science laboratory sessions. International Journal of Science Education, 43(7), 1112–1139. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2021.1902015

- Recchia, S. L., & McDevitt, S. E. (2018). Unraveling universalist perspectives on teaching and caring for infants and toddlers: Finding authenticity in diverse funds of knowledge. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 32(1), 14–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/02568543.2017.1387206

- Ruiz de Zarobe, Y., & Cenoz, J. (2015). Way forward in the twenty-first century in content-based instruction: Moving towards integration. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 28(1), 90–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2014.1000927

- Samuel, M. (2009). Beyond the Garden of Eden: Deep teacher professional development. South African Journal of Higher Education, 23(4), 739–761.

- Santos, D. B. (2014). Epistemologies of the South: Justice against Epistemicide. Journal of Living Theories, 9(2), 87–98.

- Schuck, S., Kearney, M., & Burden, K. (2017). Exploring mobile learning in the third space. Technology, Pedagogy, and Education, 26(2), 121–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2016.1230555

- Shulman, L. S. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15(2), 4–14. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189x015002004

- Smagulova, J. (2008). Language policies of Kazakhization and their influence on language attitudes and use. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 11(3-4), 440–475. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050802148798

- Soja, E. W. (1996). Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and other real-and-imagined places. Blackwell.

- Soleimani, N. (2020). ELT teachers’ epistemological beliefs and dominant teaching style: A mixed method research. Asian-Pacific Journal of Second and Foreign Language Education, 5(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40862-020-00094-y

- Tai, K. W. H., & Wei, L. (2020). Bringing the outside in: Connecting students’ out-of-school knowledge and experience through translanguaging in Hong Kong English Medium Instruction mathematics classes. System, 95, 102364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102364

- Tanaka, K. (2019). Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL): Compatibility of a European model of education to Japanese higher education. International & Regional Studies, 54, 61–81. https://meigaku.repo.nii.ac.jp/records/2895.

- Tao, J., & Gao, X. (2021). Language teacher agency. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108916943

- Tsuchiya, K. (2019). CLIL and language education in Japan. In Content and language integrated learning in Spanish and Japanese contexts, policy, practice, and pedagogy (pp. 37–56). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-27443-6_3

- Van Viegen, S., & Zappa-Hollman, S. (2020). Plurilingual pedagogies at the post-secondary level: Possibilities for intentional engagement with students’ diverse linguistic repertoires. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 33(2), 172–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2019.1686512

- Yazan, B. (2018). Identity and non-native English speaker teachers. The TESOL Encyclopedia of English Language Teaching. TESOL Press. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118784235.eelt0020

- Yildiz, M. (2019). Preservice and in-service CLIL teachers’ perceived competencies and satisfaction with the training programmes: An investigation in Spanish context [Unpublished master’s thesis, Sakarya University].

- Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods. Sage.

- Zeichner, K. (2010). Rethinking the connections between campus courses and field experiences in college-and university-based teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 61(1-2), 89–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487109347671

- Zhou, X. (2021). Engaging in pedagogical translanguaging in a Shanghai EFL high school class. ELT Journal, 77(1), 1–10.