ABSTRACT

The aim is to trace how the ethnonym Kven and the interrelated imagination of Kvenland changed over time in Nordic political discourse from the Viking Age to the mid-eighteenth century. In the negotiations over fixed borders between Sweden, Denmark and Russia, recognition of ethnic groups played an important political role in legitimating the territorial claims of the states. It brought the history of ethnic groups to the table and in the process made visible ethnonyms and names for provinces used previously. The continuity of the ethnonyms is investigated as a chronological chain of communicative and collective memory. The ethnonym and the territory of Kvenland were used by the Norwegians to maintain an ethnic boundary with the Finnish speakers in the upper Bothnian area. The names Kven and Kvenland were never used in Sweden. The investigation shows that the Kvens constituted a group of Finnish speaking people existing in continuity from the Viking Age. Their core territory was situated in the upper Gulf of Bothnia area. When this was integrated into the Swedish kingdom the inhabitants were designated Finns by the Swedes. The Finnish speakers in Tornedalen, thus, kept their linguistic and cultural continuity but lost their western Scandinavian ethnonym Kven.

Introduction

The historical province of Kvenland is mentioned in Norwegian and Islandic sources in various political discourses. From the late ninth century up to the thirteenth century it was depicted as a province inhabited by fishers and warrior groups, called Kvens. In these sources Kvenland is always located east of the mountain range separating Norway and Sweden. In the medieval sources the political area of Kvenland was variously depicted as comprising all the area north of Swedish Svealand, as in the Viking Age source, to being more specifically located between the provinces of Hälsingland, Finnmark, Finland and Karelia (Green Citation1893, 23; Ross Citation1940, 5–23; Fell Citation1983, 5–65; Egil Skallagrimssons Saga Citation1989, 30; Opsahl Citation2003, 23–60).Footnote1 In the mid-eighteenth century Kvenland was more exactly located on both sides of the estuary of the Torne River on the northernmost shore of the Gulf of Bothnia, and from there widening along its tributaries up to the Norwegian border about 350–500 km northwest of the coast. This location was determined in the Norwegian border protocols that were part of the negotiations concerning the northern part of the Norwegian-Swedish border (Schnitler [Citation1742–Citation1745] Citation1962, XX–XXV). It comprises the area recognized today as Finnish and Swedish Tornedalen. At that time it had a mainly Finnish-speaking population in its lower part nearer the coast, and a Sámi-speaking population in the upper part.Footnote2

Strangely, there are no traces of Kvenland in early Swedish or Finnish historical sources, nor have the Kvens survived to the present as a group of people in Sweden and Finland, linked to a territory as, for example, have the Sámi, Tavastians [Fin. Hämäläiset; Swe. Tavastlänningar], people from the province of Hälsingland [Fin. Hälsinkiläiset; Swe. Hälsingar] or Hålogalanders. Considering the above-mentioned sources, it has been debated whether the Kvens are a continuous ethnic group, surviving from the ninth to the middle of the eighteenth centuries. The interpretations of the sources can be divided into two main schools of thought, which also follow national lines.

The first takes it starting point in the present-day Norwegian national minority of Kvens, comprising the Finnish-speaking migrants who moved from northern Sweden and Finland to northern Norway mainly in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The Norwegian historian Einar Niemi is of the opinion that the designation Kven has continuity from the Viking Age to the present, but that this is not true of the group of people (Nor. folkegruppen) over that time span (Niemi Citation2014, 257). Erik Opsahl leaves the designation and its continuity open to different interpretations, but leans towards the position that the Kvens formed an ethnic group in the Viking Age and have since been associated with different categories, first the birkarlar who were trading with Sámi in medieval times, and secondly the Finnish-speaking immigrants to North-Norway. Like Niemi he is unsure about the continuing content of the group (Opsahl Citation2003, 30–34). This, of course, is a general uncertainty that could be applied to every ethnic group of people, whether majority groups, such as Norwegians, Swedes, Finns and Russians, ethnic minorities such as Sámi, Tornedalians, Sweden-Finns, or regionally determined groups like Hälsinglanders and Hålogalanders. No ethnic group is static; their make-up changes as the course of society changes.

In the other school, which mainly follows a Finnish and Swedish line, the issue of Kvenland was placed under the umbrella of methodological nationalism. During the stage when the nation-state was forming, Finnish historians were influenced by ideas of Finland’s cultural and geographical extension beyond the nation’s then current boundaries, and by ideas of a Greater Finland (Anttonen Citation2005; Fewster Citation2006). They started to equate the Kven ethnonym with the Finnic ethnonym Kainulainen.Footnote3 Correspondingly, the name Kvenland was equated with the Finnish region Kainuu, which was more or less equated with the County of Ostrobothnia (Yrjö-Koskinen Citation1874, 7–53; Jaakkola Citation1941, 32–41). In this nationalistic discourse Kvenland came to be associated with an ancient golden age of Finnish expansion to the north, associated with the language, culture and prehistory of the Finns. The collective memory of the Kvens and Kvenland was used to create a Finnic past for the Finnish national consciousness.

The assertion that the Kvens were Finnish speakers was met with opposition from Swedish researchers claiming that they were Swedish speakers (Wiklund Citation1896, 103–117). The fusion of the ethnonyms Kainulainen and Kven was also woven into the issue of the ethnic origin of the birkarlar. Finnish researchers argued that the Kvens/Kainulaiset were the predecessors of birkarlar, and were consequently of Finnish origin (Jaakkola Citation1941, 32–41; Luukko Citation1966, 21–38). The arguments were countered by the Swedish researcher Birger Steckzén, who did not want to interpret the institution of birkarlar as a Finnish invention, especially not one connected with the Kvens and Kvenland in the Viking Age (Steckzén Citation1964, 108–118). In Finland the opinion has been maintained that Kven and Kainulainen are different ways of denoting the same indigenous Finnic people, who initially lived along the coastal area of south-western Finland and then spread along the Bothnian coast to the Swedish side (Vilkuna Citation1969; Huurre Citation1979, 264–266; Vahtola Citation1980; Vahtola Citation1991, 209–214; Heikkilä Citation2014, 181–266).

In the early 1970s the concept of Kvenland was used to create a historical northerly Finnic identity in the county of Oulu and Lapland. Historical research was established at the University of Oulu after the Faculty of Humanities was set up in 1972, and in 1977 the newly founded Northern Finland’s History Association issued its first yearbook entitled Faravid after the Kven king in Egil’s Saga. Footnote4 The historical research into the continuity of Finnic people, from prehistoric to historical time, situated the fused area of Kvenland and Kainuu in a discourse of North Finnish identity and regional policy (Faravid Citation1977; Julku Citation1986). Kvenland and King Faravid thus became part of the creation of a northern regional identity within Finland, while at the same time its prehistoric narration contributed to the national identity. The use of Kvenland as an ancient element for strengthening a northerly Finnic identity in Ostrobothnia was not a cause of nationalistic conflicts between Finland and Sweden as was the case earlier, when it was used as an element in the creation of national identity. On the contrary, the idea was integrated into a transnational co-operation concerning a northerly identity, using the North Calotte area as an area for Nordic co-operation within the subject of history (Elenius Citation2018a). Ostrobothnia and the North Calotte follow the general stages in the creation of regional identity, which is characterized by symbolic shaping of regional identity, territorialization and institutionalization (Paasi Citation1996). This way of using the region as a platform for creating identity during the development of modernity could be called methodological regionalism in the same way as methodological nationalism is used with reference to the nation.

In a Swedish regional context, the two ethnonyms have been equated in the county of Norrbotten. The Swedish archaeologist Thomas Wallerström equated the Kvens with Kainulaiset, as did the Finnish researchers in general. In his dissertation he expressed the opinion that the ethnonym Kven or Kainulainen did not depict any ethnic group, but was an epithet given to the several different people engaged in the medieval fur trade (Sundström, Vahtola, and Koivunen Citation1981; Sundström Citation1983, Citation1984; Wallerström Citation1995, 213–229, 238). The archaeologist Ingela Bergman has argued that the lack of Kven place names in the coastal area around the Gulf of Bothnia is replaced by Gaino or Kaino names in the inland area, denoting the same group of people. She argues that the Kven ethnonym designates a section of the population together with the Laps and Finns, but one that has a separate form of livelihood with elements of cultivation, hunting, trapping and perhaps reindeer herding (Bergman Citation2010, 179–182). In a recently published article I have argued that the fusion of the two ethnonyms does not correspond with the historical pattern of encounter between Sámi, Finnic and Scandinavian groups in Finland and in the northernmost area of the Gulf of Bothnia. The Kven and Kainulainen ethnonyms must be analyzed separately in their different historical contexts. The Kainulaiset seem to have been Swedish speakers, whom Finnic and Sámi groups first encountered along the coast of Finland in the early Iron Age. The Kvens seem to have been a Finnish-speaking group (Elenius Citation2018b).

In both Norway and Sweden the contemporary debate on indigenous rights has also influenced the interpretation of the history and ethnic background of the Kvens. The ethnopolitical, transnational Kvenland Association, for example, has called into question the accepted view that the Sámi are the only indigenous people in Sweden and Norway, and claim that the Kvens have an equal right to use the territory. This has been met with resistance by researchers both in Norway and Sweden (Kvenangen Citation1999, 26–28, Citation2002, 18–19; Lundmark Citation2002, 18–19; Ryymin Citation2004, 133–151). The Suonttavaara Lappby Association, which is part of the Kvenland Association, has tried to prove an early Kven history as part of their political aim to be recognized as an indigenous people, like the Sámi (see the site http://www.suonttavaara.se; Wallerström Citation2006; Elenius Citation2007, 89–110; Hagström Yamamoto Citation2010). In this ethnopolitical context the transnational concepts of Kvenland and Sápmi have also been compared as historical constructs within the discourse of nationalism (Elenius Citation2018a).

However, no convincing explanation has been presented of why Kvenland never appeared in Swedish and Finnish historical sources, or why it disappeared as a political province after the fourteenth century while Hålogaland, Hälsingland and Karelia, for example, remained. Kven and Kvenland are Western Scandinavian denominations, but to date they have been fused with the concepts of Kainulainen and Kainuu. They have not been systematically analyzed in the context of the chain of political discourses and cultural memories in which they occurred.

The aim of this article is to trace how the concepts of these denominations changed over time in different political discourses from the Viking Age up to the mid-eighteenth century. The modern use of Kvenland in its ethnopolitical context will not be investigated, nor that of the Kvens as an immigrant minority in northern Norway. The most important questions are:

How did the imagination of the geographical area of Kvenland change from the Viking Age to early modern times from a Norwegian and Danish perspective?

How did the demarcation of territorial states with fixed borders influence the change in the ethnonym Kven in relation to other ethnic groups?

What form did the parallel Swedish naming of ethnic groups of people and different provinces in the Gulf of Bothnia area take?

What can we tell about the continuity of language and other ethnic markers among the Kvens from the Viking Age to the present?

The method used is a critical textual analysis based on an empirical approach.

Ethnic groups and theories concerning collective memory

This article's investigation into the changed recognition of Kvens and the location of the province of Kvenland covers a long period of historical development. It is connected to the slowness of change in the landscape and environment which, together with the maintainance of traditional techniques, only gradually led to changes in the institutions of ethnic interaction (Braudel [Citation1949] Citation1997, 13–14). The most persistent mark of ethnicity in the transition from the Iron Age to historic time is language; language has proved to be one of the most lasting characteristics of human communities in migration processes, overweighing estate, class and other social categories. In order to survive, languages require larger communities, at least several hundreds of people who speak the same language (Manning Citation2013, 3–4).

However, there are also language shifts among ethnic groups of people. Language boundaries tend to stabilize when one language group predominates in an area, and conversely, language boundaries change when demography changes (Naert Citation1995). K. B. Wiklund, for example, thought it was possible that a language shift from Swedish to Finnish occurred in Tornedalen somewhere in ancient time (Wiklund Citation1896, 103–117). In contrast, new research has expanded the Finnic language sphere to cover both the Swedish and Finnish side of Fennoscandinavia (Fogelberg Citation1999; Wiik Citation2004). From an archaeological perspective, findings from the Stone Age suggest that the Kvens spoke a surviving Fenno-Ugric language associated with either Finnish or Sámi (Bergman Citation2010, 179–182). In Norway there has been no doubt that the Kvens, at least from the sixteenth century onwards, were Finnish-speaking immigrants from Tornedalen and North-Finland who settled in northern Norway (Niemi Citation1983, 103; Hansen and Evjen Citation2008, 29–47).

The concept of ethnicity in written sources is used here to trace changes in group identities. In addition, the concept of ethnically demarcated groups of people is used. Groups of people means that they identified themselves with the larger category of people, which is also regarded as an ethnic marker, but that they constitute a subgroup within it (Elenius Citation2018b). Thus, they constitute what Anthony D. Smith calls ethnies, i.e. unified groups of people within a relatively broadly defined territory of settlement, united by a common language, culture, history and mythology, and identifying themselves as a people in relation to other people (Smith Citation1991). This does not exclude the possibility that ethnic categories can also be part of historically contingent social systems of classification, and thus can be modified and change over time (Fenton Citation2010, 112 ff.).

In order to weigh persistence against change it is necessary to consider how powerful and dominant a settled group was at the time when the encounter with other groups took place.

Ethnicity does not exclude the possibility of cultural exchanges taking place across the ethnic boundary; it only asserts that the identification of one’s own group in relation to other groups is maintained as long as the differences are considered socially significant (Barth Citation1969, Citation1994; Eriksen Citation1993; Olsen Citation2003). The relevance of applying ethnicity to prehistoric conditions has been questioned within the field of archaeology, crucially because finds are often so sparse that they do not provide enough information about ethnicity (Jones Citation1998, 15–39, 128–144; Myrvoll and Henriksen Citation2003; Hansen and Olsen Citation2006, 36–51; Wallerström Citation2006; Ojala Citation2009, 30–33).

We cannot expect that an ethnonym that was used to denote a small ethnic group will denote the same group a thousand years later. On the other hand, many ethnonyms correspond to specific peoples, associated today with nations such as Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia, to mention only examples in Subarctic Europe. There are also ethnonyms connected to groups of people, like the Sámi in Sápmi, Kvens in northern Norway and Tornedalians in northern Sweden. These minority ethnonyms have an ethnic historical continuity, even if the groups they denote do not have a state of their own. Additionally, the conscious use of ethnicity in the creation of national identity is a typical example of methodological nationalism, often used with the dominant majority population acting as a constitutive element in creating imagined national identities (Chernilo Citation2007).

One way of investigating changing ethnic relations from prehistoric to historic time is to treat ethnonyms as marks of ethnicity, i.e. as the cultural markers for maintaining social boundaries between groups of people. Ethnonyms are used here to investigate ethnic relations using three specific criteria. The first is the way in which the territorial homeland associated with the ethnonym has been defined by the ethnic group itself and by others, and how that may have changed over time. The second is tracing language as a persistent marker of ethnicity, one of the most important when connected with the ethnic group’s homeland. A common homeland and a common language (ancestral or adopted) are the critical minimum markers of a nation and national identity (Oommen Citation1997, 19–34).

The third criterion is that ethnonyms are treated as remaining memories of the encounter between ethnic groups. The way in which ethnic groups and provinces are recognized in sources from the Viking Age to early modern times must be situated in a discourse of collective memories. Maurice Halbwachs argues that it is through membership of a social group that individuals are able to acquire, localize and recall their memories (Halbwachs Citation1992). Our memories are located within the mental and material spaces of the group by a kind of mapping. The mental spaces always receive support from and refer back to the material spaces that particular social groups occupy. To study the social formation of memory is to study those acts of transfer which make remembering possible (Connerton Citation1989, 36–40; Nora Citation1996, 1–23; White Citation2000, 49–74; Wertsch Citation2002, 30 ff.).

These transfers comprise socially shared, lived memories within specific groups, but also culturally constructed knowledge about a distant past and its transmission through the creation of traditions (Halbwachs Citation1992; Erll Citation2011, 9–18). The former have been regarded as a communicative memory, the latter as a cultural memory. Since communicative memories are created through everyday interaction they fall into oblivion within a specific time span, i.e. when people die. The cultural memory, in contrast, belongs to the mythical past and ancient history (Assman Citation2011, 15–69; Erll Citation2011, 27–37).

The historical accounts of ethnic groups and geographical provinces are here regarded as both communicative and collective memories. The narratives about the Other formed a kind of cognitively imagined map. It could be that a person had made a journey to some places and in those places heard about yet other places. The location of different ethnic groups of people and provinces belonged to the collective memory of those who had visited or heard about them, so the accounts were not exactly situated in the geography. Various kinds of accounts about Kvenland and the Kvens are analyzed as a chronological chain of communicative and collective memory within differing political discourses.

The memories of other ethnic groups of people were maintained through everyday oral exchange among family and kinship members, but also in the communication with hunters, travellers, merchants and others – a form of belonging to the communicative memory of living persons. On the other hand, ethnic groups were also mythologized and inscribed into the more enduring cultural memory which was transformed over generations. Oral memories are characterized by a “structural amnesia”; everything not immediately needed must be forgotten. Memories of other ethnic groups that survived orally over generations were therefore of importance. Literacy and map printing changed the nature of collective memory fundamentally (Erll Citation2011, 113–143). Comparisons of pre-state geographical world-views, as cognitive maps without exact borders, with that of the demarcated territorial state on a printed map, must be handled with care. It is possible, however, to investigate the political discourse in which groups of people and historical provinces have been imagined, and to compare changes in the representation of groups of people over time.

Before the introduction of Christianity and consequent formation of a new kind of centralized state there were many different petty kingdoms in northern Fennoscandinavia which were politically autonomous (Ramqvist Citation1991, 305–318). The forming of states in large parts of Central Europe was typified by an initial phase of plundering and forced collection of tributes, but when the conquerors met resistance from the people living in the attacked area the economic control of their own area increased (Lindkvist Citation1988, 62). The focus could also have changed from extensive trading and plundering expeditions to territorial conquest of nearby areas. This was what happened when the Viking expeditions along the Russian rivers declined and the focus shifted to the territorialization of Finland and Estonia and later to the Bothnian area. In the second phase of state formation these areas were colonized and integrated into the state (Tegengren Citation2015, 1–15, 41–77). The process of colonization was born from both economic and political goals, two sides of the same coin (Hansen and Olsen Citation2006, 124 ff.).

Within this period of state building Kvenland and Bjarmaland disappeared as territories containing recognized groups of people, in favour of new ethnic constellations within patrimonial kingdoms. During this time of transformation merchants played a crucial role in the changed recognition of ethnic groups. Earlier the relations between merchants and indigenous people in those territories was as much political as concerned with trade. Trade was maintained by armed merchants who simultaneously belonged to specific ethnic groups of people and were clan leaders. They established military alliances with other armed merchants and groups of people (Bratrein Citation2018).

It was such travelling clan leaders and merchants that, in the Viking Age, created a basic geographical knowledge about the northern regions and its ethnic groups of people. From at least the eleventh century onwards they carried out their trading expeditions on behalf of the king and continued to collect tribute from the hunting people they traded with. Subsequently, merchants came to play an important role in legitimating the borders when the new system of territorially demarcated states was created. Two main principles were used for claiming the better right to a territory: the merchant’s customary right to trade and the king’s right to tax his subjects in the area claimed. As no written regulations or laws existed for these activities, evidence came to be based on the witness of the collective memories of the traders and Sámi.

It was now no longer the personal relationship between the clan leader/merchant and his subjugated groups that determined the extent of the realm, but the geographically demarcated area in which the group of people in question lived. The territorial state border was consequently drawn both between and within groups of people. In that context, denominations of ethnic groups were used to prove how far the borders of one’s own realm of taxation extended, and based on that, where the ultimate border between the states should be drawn.

In this context of national challenge, the drawn and printed map became a new kind of evidence for legitimating the power of the state. Benedict Anderson specifies the map, the census and the museum as the three pivotal elements in the consolidation of colonial power in southeast Asia (Anderson Citation1991, 170–178). Maps are crucial to the spatial socialization in which nations, regions and peoples are positioned regarding each other. They are therefore crucial for the practice of state power. The maps were not only used in the service of the state for legal reasons, but also for propaganda purposes (Wood Citation1991; Mead Citation2002, 69). The sixteenth and seventeenth centuries saw an explosion of maps of northern Europe which tried to represent the countries, provinces and places as scientifically and relevantly as possible (Ahlenius Citation1900; Lönborg Citation1901; Bratt Citation1958; Julku Citation1986; Ehrensvärd Citation2006). Actually, many of the first maps were created by merchants and seamen, so merchants were also involved in drawing state borders because of their cartographical expertise. The map of the Dutch merchant Simon van Salingen, which is of central interest in this article, combined the merchant’s view of the Northern areas, where economic aspects guide the details, with the political agenda of the Danish king who engaged him to create the map.

By antedating their nation’s activities, the negotiating states sought to make the continuity of their own territorial occupations appear as long and uninterrupted as possible. The periods when the borders were drawn were thus also periods when the parties involved sought to demarcate as clearly as possible ethnically determined regions in relation to each other, implying that ethnic groups had to be named and situated geographically. In these activities the king sought help from tax bailiffs as well as from merchants who had travelled, carried out services and done business in the disputed areas. This article assumes that ethnic groups of people were made visible during those periods when state borders were drawn.

The state transformation period under investigation is the end of the sixteenth and beginning of the seventeenth centuries when disputes arose between Sweden and Russia concerning the state borders between the two realms, and also between Denmark-Norway, Sweden and Russia about occupation and taxation rights in the Arctic Ocean area and the Kola Peninsula. The period is chosen because it is one of transition from the old trading system, carried on by Hålogalanders in northern Norway and birkarlar in northern Sweden and Finland, to a new system of regulated trade within the administration of the state. The representations of ethnic groups in the transformation period will be compared with those in early medieval times and in the Viking Age in order to establish a chain of empirical statements about the Kvens and Kvenland from the Viking Age to the mid-eighteenth century, and to discover how the ethnic boundaries with other groups might have changed. In this regard the interaction of communicative and cultural memories is used to reveal the continuity of ethnic groups.

Viking age and medieval accounts concerning Kvens and Kvenland

The first time the Kvens and Kvenland are mentioned is in an account from the end of the ninth century by the Norwegian chieftain Ohthere, living in Hålogaland in northern Norway. He described the Kvens as a group of people who lived to the east of the Scandinavian mountain range. Along the southern part of the land [Norway], on the opposite side of the fells, was Svealand. On the opposite side of the fells in the north was Kvenland. In summertime the Kvens carried their very small and light boats overland to the large fresh-water lakes at the foot of the fells. From there the Kvens harried the Norwegians across the fells, and sometimes the Norwegians harried the Kvens (Ross Citation1940, 5–23; Fell Citation1983, 5–65; Opsahl Citation2003, 23–60).

Ohthere’s account must be put into the context of an expanding fur market, which can be seen in Sweden in the presence of an increasing number of Sámi places of sacrifice with metal deposits linked to the period AD 800–1300 (Serning Citation1956, Citation1960, 87–94; Zachrisson Citation1984; Malmer and Malmer Citation2005). It must also be related to the increasing Sámi use of purchased utility goods, adapted to a more nomadic life (Bergman Citation2007, 1–16). From his account it seems that politically Kvenland comprised the area north of Svealand, but the fact that he did not mention any other province north of Svealand makes his political description difficult to assess. There were autonomous petty kingdoms, or at least strong Scandinavian chiefdoms, in the area of present-day Sundsvall in the centuries of the great migration, long before Ohthere’s account (Ramqvist Citation1991, 305–318). In comparison, Historia Norwegie, written in Latin by an unknown author somewhere between AD 1150–1170, was much more informed regarding politics than Ohthere. Both Ångermanland and Jämtland were mentioned as two northerly Swedish provinces, but not Kvenland and not Hälsingland. The Kvens were mentioned together with four other Fenno-Ugrian groups of people, all depicted as pagan tribes in the east (Ekrem and Mortensen Citation2003, 53–54, 114). Even this political description is confusing in light of the knowledge that Medelpad and Ångermanland were brought under the common law of Hälsingland at the very beginning of the fourteenth century, but Hälsingland is not mentioned in the description (Tegengren Citation2015, 5–7).

We must consider Ohthere’s description of Svealand and Kvenland as a very rough political classification from a man who obviously did not know so much about the political regions of northern Sweden at that time. Like the first printed maps of northern Europe, his outlook was limited, distorted and inexact, based on the accounts of people who had visited different parts of the described area. It therefore seems fair to say that the idea of Svealand in Ohthere’s account must have included strongholds of Scandinavian settlements at least up to Ångermanland and southern Västerbotten. We do not know, but he probably never visited Kvenland. If he had, he would doubtless have told about it, as he did about his visit to remote Bjarmaland in the White Sea area. From his account it is apparent that the Norwegian encounter with the Kvens in that time occurred in a summer context when the Kvens visited the large lakes on the eastern side of the mountain range for fishing. It is not stated at what time of the year the Norwegians harried the Kvens.

Ohtere distinguished Sámi as reindeer herders, hunters and fishers, from Kvens as a people who were settled in a “land”. During the Viking Age, Scandinavians often named territory settled by people with the extension -land, as in provinces such as Finland, Estonia [Swe. Estland], Gotland, Hålogaland, Bjarmaland, Hälsingland and Kvenland. It was a comprehensive term used to denote the ethnic group of people living in a specific territory. The Swedish Lappmarkerna or Norwegian Finnmarken are typical examples of how areas outside the settled lands were associated with the Sámi people and their means of livelihood (Elenius Citation2014, 32–69). The extension -mark indicated that it was situated outside the settled area of farmers. It could also show boundary areas between different territories (Olwig Citation2004, 39–63). We can assume that some kind of farming was carried out in Kvenland as well as in Bjarmaland.

Three hundred years after Ohthere’s account, in the early thirteenth century, the writer of the Islandic Egil Skallagrimsson’s Saga told of the contacts between Norwegians and Kvens. In the words of the saga:

But eastwards from Naumdale is Jamtaland, thereafter Helsingjaland and Kvenland, then Finland, then Kirialaland [Karelia]; along all these lands to the north lies Finmark, and there are wide inhabited fell districts, some in dales, some by lakes. The lakes of Finmark are wonderfully large, and by the lakes there are extensive forests. But high fells lie behind from end to end of the Mark, and this ridge is called Keels (Green Citation1893, 23).Footnote5

The saga tells of Thorolf Kveldulfsson, who was supposed to have lived in the tenth century. The account is set in winter and takes its starting point in the middle of Norway, in Helgeland. According to the saga Kveldulfsson made three journeys in the fell area, typically combining trade and warefare. The first year he kept to the traditional fell area where he had just received the privilege of taxing the Sámi on behalf of the king, taking with him 90 armed men instead of the usual 30 men. The next winter he carried out a similar official tax journey, combined with a private military and trading expedition. He went far to the East and this time he was contacted by a messenger from King Faravid of Kvenland. The king asked Thorolf for help in a military expedition against the Karelians who had harried among them, so Thorolf went first to Kvenland to join King Faravid and thereafter up in the fells where they met the Karelians and beat them. The next year Thorolf went directly to Kvenland and together with King Faravid repeated the same journey up to the fell area and from there went into Karelia where they assaulted the settled areas they dared to attack (Green Citation1893, 17, 23–24; Egil Skallagrimssons Saga Citation1989, 22–23, 29–31).

The last time the Kvens were mentioned as a military force was in 1271 when, according to Norwegian sources, they attacked Norwegian targets on the edge of the Arctic Ocean in co-operation with Karelians. The various sources, however, do not agree. In one source only Karelians are mentioned, in another the Kvens are replaced by “Kurmenn” (Wiklund Citation1896, 108; Opsahl Citation2003, 31). We cannot regard the Icelandic sagas from this time as primary historical sources for what happened in the Viking Age. They are written in a specific medieval mode with a warrior style and moral (Males Citation2017). The mentioning of the province of Finland in Egil’s saga, but not in Ohthere’s account or in Historia Norwegie, clearly places the political landscape in medieval times, not in the tenth century that it purports to describe. It was in the thirteenth century that the documented Swedish crusades to Finland took place and it was from that time that it was integrated into the Swedish kingdom as a new eastern province.

The Islandic sagas can, however, be used to analyze contemporary understanding of the surrounding world. We do not have to question the kind of contacts between groups of people that are described, even if accounts of that time cannot be treated literally as portraying historical events (Heather Citation2009, 515–616). They were written in a time when the Viking expeditions belonged to a past era and the political landscape was undergoing a process of radical change compared with Ohthere’s time (Tegengren Citation2015, 19). The possible author of Egil Skallagrimsson’s Saga is Snorri Sturluson. He was a lawyer in Iceland and one of its most powerful men, with great political experience. As he had also visited both Norwegian and Swedish nobilities during his lifetime, his political analysis of the provinces in the northern areas of Sweden, Finland and Novgorod is much more detailed and reliable than Ohthere’s.

There are, however, details in Egil’s Saga that are anachronistic. It describes how the king had the right to trade with the Sámi, a right that was recurrently conferred on some of the king’s county sheriffs [Norw. sysselman], but according to Lars Ivar Hansen the institution of county sheriff was only introduced in the late twelfth century, not in the tenth century. Similarly, the king had no monopoly over the Sámi tax before the middle of the eleventh century. The king’s right to collect the so called Finn taxation [Norw. finneferden, finneskatten], which referred to the right to tax the Sámi, dates from that time (Hansen and Olsen Citation2006, 61).Footnote6 This anachronism in Egil’s Saga does not affect the Finn taxation as a phenomenon, nor call into question the carrying out of such remote military expeditions. From Ohthere’s account we know that this kind of regular taxation of the Sámi was already a reality as early as the late ninth century. He also mentioned that the Hålogalanders ravaged the Kvens, which must be interpreted to mean they crossed the mountain range into the territory he called Kvenland (Ross Citation1940, 5–23; Fell Citation1983, 5–65; Opsahl Citation2003, 23–60). Both accounts prove that the area around the Gulf of Bothnia was familiar to the Norwegians.

One might ask why Ohthere or Thorolf did not meet the birkarlar on their journeys to Kvenland. Adam of Bremen mentions, in the mid-eleventh century, that there were “skridfinnar” living in the Ripheian Mountains, who were ruled from Hälsingland (Adam av Bremen [Citation1070] Citation1984, 221, 251). From the context of the text it is obvious that “skridfinnar” was the name given to the Sámi, and that the Ripheian Mountains correspond to the Scandinavian Mountains (Nyberg Citation1984, 317–377). He did not, however, mention any birkarlar, and none of the western-Scandinavian sources above mention them as fur traders in the area of the Gulf of Bothnia up to the thirteenth century when Egil’s saga was written. Nor are they mentioned in the Swedish Lex Helsingiae (Swe. Hälsingelagen) written at the beginning of the thirteenth century, which is very strange considering the economic power and territorial rights of the birkarlar at that time (Holmbäck and Wessén Citation1940; Hansen and Olsen Citation2006, 106; Elenius Citation2014, 32–69). There are no written Swedish sources from the time that mention the institutional right of the king of Sweden to tax the Sámi in the Viking Age.

The director-general of the central board of national antiquities, Johannes Bureus (1568–1652) noted from early historical sources that King Magnus Ladulås (1240–1290) tried to bring the Sámi under his rule but failed. He therefore stated that anyone who could manage to achieve this would be allowed to rule the Sámi. The fur traders from the Pirkkala parish in Finland succeeded (Bureus [Citation1651] Citation1886, 180). It is a matter of much dispute whether Bureus’s account can be trusted, but the lack of Swedish sources about earlier Sámi taxation actually support it.

One conclusion that can be drawn is that the institution of birkarlar cannot date earlier than from the beginning of the thirteenth century. It is plausible that it was established during the reign of Magnus Ladulås or perhaps that of his father, Birger Jarl. It is very likely that the king of Sweden derived his right to tax the Sámi from the Hälsinglanders, described by Adam of Bremen, but also from the Finnic fur traders that Bureus described. This royal custom probably grew in parallel in Scandinavia. In Norway it is documented as deriving from the old right of the Norwegian king to finneferd, i.e. taxation of the Sámi, while in Sweden this royal right was transferred to the birkarlar on payment to the king.Footnote7 Another conclusion is that the activities of the Kvens preceded the birkarlar. In the proto-state period fur traders and tax collectors, like Naumudalers and Hålogalanders from Norway, Kvens from the Bothnian area and Karelians from Finland or the White Sea area, competed in the lucrative fur trade with the Sámi. They are all mentioned in the western Scandinavian sources.

Olaus Magnus on ethnic groups in the northern areas

The first and only time Kvens are mentioned in Swedish sources is in the account of Olaus Magnus of his visit in the parish of Torneå in the province of Västerbotten at midsummer in 1519. On the trip he probably journeyed to St. Andreas’s chapel in Övertorneå, 60 km upstream of the Torne River, and also to Pello which was a further 60 km upstream, in order to inspect the salmon fisheries and to sell letters of indulgence. At the same time he collected folklore (Ahlenius Citation1895, 46; Olaus Magnus [Citation1555] Citation1976a, vol.4, 501–503). The local observations Olaus made must be treated as an eyewitness account from that time. He is known for his interest in the details of how people lived, their customs and beliefs, and his observations should be given as much credance as Ohthere’s account.Footnote8 His observations must be regarded as contemporary communicative memories, but mixed with cultural memories of a more mythological kind.

From his account of the many different people who frequently visited the Torne market on the northernmost shore of the Gulf of Bothnia, it is clear that Norwegians were still there in the summer of 1519. He noted that: “ … furthermore quite a number come from Norway across the high fells and extended wilderness, as well as across Jämtland.” (Ahlenius Citation1895, 46; Olaus Magnus [Citation1555] Citation1976a, vol.4, 166).Footnote9 His description of the Norwegians coming from different directions echoes both Ohthere’s account and Egil’s Saga. It is possible, however, that Olaus put together what he heard about the Norwegian's winter travels with his own summer experiences. We must remember that all accounts of travelling that appear in Egil’s Saga occur in a winter context. It is difficult to imagine how anyone could have made the difficult journey from the area of Trondheim across Jämtland to Torneå in summer time, by boat following the rivers, and without any regular shipping along the Bothnian coast. It is more likely that summer travellers from northern Norway went by boat down the well-known Torne River to the Gulf of Bothnia around midsummer. According to Ohthere, the Kvens had already travelled up to the mountain lakes to fish six hundred years earlier. In the sixteenth century the birkarlar, or berkarlar as Olaus called them, still journeyed extensively from the Bothnian coast to the Tromsø area on the Atlantic Ocean as well as to the Varanger area on the Arctic Ocean. Three Finnish speakers from Tornedalen arrived in Kvænangen in northern Norway in February 1553 with an instruction from the Swedish King Gustav Vasa that they should levy taxes on the Sámi people living there (Bjørklund Citation1985, 19).

In his famous map Carta Marina, printed in Venice in 1539, there is a wonderful drawing of a wheeled wagon being pulled by two reindeer. Two men are in the wagon, which is fully loaded with goods, one sitting steering it and one standing in the back with an arrow in a drawn bow. In front of the equipage is the text “BERKARA QVENAR”, and the legend reads “ … the highlanders have 400–500 reindeer, which are used for pulling wagons and sledges and for riding on, because they are more comfortable on snow than horses” (Olaus Magnus [Citation1539] Citation1964, 12–15).Footnote10 This is the first known written Swedish source, and one of the very few in which Kvens are named. A version of the picture was also used in his History of the Nordic People from 1555, where he wrote:

Their journey is thus directed through the smooth valleys towards Norway, where they often travel, regarded as being the nearest place for the exchange of goods and … through visits there try to maintain the good friendship with that people. Those, who handle those vehicles, are commonly called kvenar (Quenar) by the people (Olaus Magnus [Citation1555] Citation1976a, vol.4, 33–34).Footnote11

The description of the “smooth valleys” to Norway should be contrasted with an account from the mid-eighteenth century describing that it was only possible to go by foot in summer and by Sámi vehicles in winter from Ofoten in Norway to the Torne Lap land in Sweden (Schnitler [Citation1742–1745] Citation1929, 203, 337). The depiction of a wagon with large wheels for long-distance transportation in winter time is, thus, unrealistic and is not inherent in the Sámi or Finnic culture of the area, nor has it been described by anyone except Olaus Magnus. If he saw such a wagon pulled by reindeer when he visited Torneå it must have been used by the Finnish-speaking population who, influenced by daily intercourse with the Sámi, had incorporated reindeer into their working life. They might have used this kind of transportation for shorter distances in their daily work in summer.

In another chapter Olaus describes, very realistically, how the Laps have sledges to which they hitch reindeer and he illustrates this with a realistic picture of reindeer pulling an ackja [Eng. Laplander’s sledge] in a winter context (Olaus Magnus [Citation1555] Citation1976a, vol.4, 33–35). There were also other reindeer-drawn sledges for transportation of goods in the Northern area. The traveller Jan Huygen van Linschoten made a drawing of such a sledge on a map when visiting the White Sea area in 1594–1595. It was quite high and rectangular, equipped with bent runners made of birch so that it could be used both in summer and winter time. However, it was used for transportation in the open tundra landscape on the shores of the Arctic Ocean (Naber Citation1914, 136–137) and could not be used in the forest area.

It is difficult to distinguish between the ethnic groups in Olaus’s account. Sometimes he equates Sámi with Bothnians, but on other occations he separates them into different categories (Bergman Citation2010, 167–192). When he tells that some of the people own reindeer herds comprising of 10–500 animals, which are driven to grazing and then back again in the evening to fenced places, it is very reminiscent of the culture of forest Sámi (Olaus Magnus Citation1976a, vol.4, 32). It is obvious that he could not clearly sort out the different kinds of ethnic groups. It is also difficult to discern the way in which Olaus Magnus combined communicative and cultural memories, i.e. what he heard from people living in Tornedalen at that time and what was taken from earlier accounts.

Van Salingen’s map of Northern Europe

When the ship of the English adventurer Richard Cancellor reached Rose Island at the estuary of the Dvina River in the White Sea in late November 1553 it profoundly changed the international importance of the Northern areas. The new northern seaway sharpened the conflict over the territory in the north between Sweden, Russia and Denmark. In order to succeed with the territorial claims it was of the utmost importance to prove that the ethnic groups of people in the territory claimed belonged to the kingdoms. For example, in his official coronation in 1607 the Swedish King Charles IX declared himself the king of “Sweden, Göthis (Swe. Götaland), Wöndis (Swe. Wende), Finns, Karelians, Laps in the Northern lands, and the Kajaans and Estonians in Livonia”Footnote12 (K Citation17 a. Handlingar rörande). The same formulation was confirmed by the Riksdag in Örebro in 1610 and one year later in Nyköping in 1611 (Stiernman Citation1728, 635–636, 645). It is obvious from the king's title the great importance he attached to the issue of distinguishing between the Finns, Karelians, Kajaanis and Laps in the northern and eastern part of the kingdom. The Kvens, however, did not appear among the ethnic groups of people that were mentioned.

The conflict between Sweden and Denmark was sharpened when, in 1595, Sweden and Russia agreed the Treaty of Teusina and fixed the border between the two countries without informing Denmark about its content. A further important outcome of the treaty was that Russia would not hinder the Swedish tax collectors from taxing the Sámi in the area from Ostrobothnia to the shore of Varanger Fjord (Rydberg and Hallendorff Citation1903, 79 ff.; Enewald Citation1920, 88). After Christian IV ascended to the Danish throne in 1596 he immediately engaged in the northern issues. In order to proclaim his sovereignty over the northern area, Christian made a symbolic voyage to the Varanger and Kola Peninsulas in 1599 (Hagen and Sparboe Citation2004). By chance, newly created maps by Ortelius and Hondius came into his hands which seemed to show that Finnmarken belonged to Sweden. A map by Gerard de Jode published in 1578 was also coloured in such a way as to show that the Kola Peninsula belonged to Sweden (Ehrensvärd Citation2006, 60–63, 118–119). Christian was greatly upset and it was probably against this background that he engaged the Dutch merchant Simon van Salingen to create a map that would confirm the Danish hegemony over Finnmarken and the Kola Peninsula.

Van Salingen was one of the pioneering Dutch merchants trading in the northernmost areas bordering the Arctic Ocean, and he became an experienced visitor to the Kola Peninsula and White Sea area. In the years 1567–1568 he surveyed the coast of the White Sea, measured the depth of the sea and charted the harbour conditions. He was known as one of the foremost experts on conditions in this area, and in 1584 was already engaged on the Danish side in the conflict over the northern territory (Naber Citation1914, LXXVI; Hagen Citation2004, 9–27). In his own account he describes how some years he stayed over the winter period, how he met people of different ethnicities, not least Russians and Karelians, in the inner part of the White Sea area. Some of them were old and had visited the villages and met clerks in the area. They had much to tell him about the routes of the Novgorod merchants and the warfare between Moscow and Novgorod in Russian Karelia. They also spoke about the relations between Russia, Norway and Sweden, and about the people living in the Northern areas (Salingen Citation1914, 211–222). In contrast to many other foreigners, van Salingen did not visit the Northern areas only once or twice, but did so repeatedly over a period of 30–40 years. His information on ethnicity in the area should therefore be regarded as well-founded.

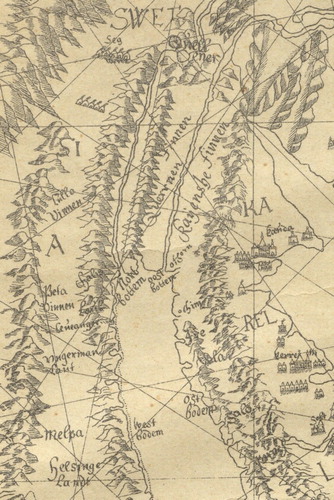

The map that van Salingen created is well known (). It was published in 1601 and also used in a meeting on the Russian border (Naber Citation1914, LXXIV–LXXVI; Mead Citation2002, 68; Ehrensvärd Citation2006, 119, 125–129). It has been criticized because it relies heavily on earlier maps, with their merits and demerits, and because it is so disproportionately drawn and geographically misleading. Both Sweden and Finland are shown as remarkably long and narrow, while the White Sea area and the Kola Peninsula are surprisingly detailed and in proportion. The narrow shape of Finland is very reminiscent of Petrus Plancus’s map of Europe from 1594. In the context of this article it is not the professionalism of cartography that is important. Van Salingen’s map is an economic and political map, focusing on the contested areas which both he and Christian IV of Denmark were interested in. It does not give a realistic picture of the Swedish and Finnish areas, but when thinking of the map as a cognitive map of ethnicity we can overlook the poor representation of the geographical proportions.

Figure 1. The Kola and White Sea areas in Simon van Salingen’s map of 1601. Source: Simon van Salingen’s map of Scandinavia (1601) (curtailed). The National Archive of Sweden, Stockholm.

According to Naber (Citation1914, LXXIV–LXXVI) there is one original of the map in Copenhagen, and according to the Finnish historian Kyösti Julku (Citation1986, 116–119) there is also one in the National Archive in Stockholm and a copy in the National Library in Helsinki. A comparison between the original map in the Swedish National Archive and the copy in the National Library in Helsinki shows that they are not identical. The original map is coloured and dated 1601 while the copy is in black and white. The file information in the National Library in Helsinki states that the black and white copy was issued in Copenhagen in 1601. At the bottom of the copy, however, are the words “Kopieret af Kaptein Schiötz 1891”, indicating that it was copied in Denmark in that year. Footnote13

The place names in the original Swedish map have been added in black and over the years have faded to a light brown or red, but in some places they have retained their original black colour. Many of the names are so faded that it is impossible to read them today (Simon van Salingen's map Citation1601). The impression is that the place names and ethnonyms were inserted in the original map by the experienced Simon van Salingen at the time the map was drawn. In the Helsinki copy all the place names are clear and legible. The map is a very precise copy in shape and detail of the coloured map in Stockholm. Even the details of the realistically drawn houses on the shores of the White Sea are very similar.

In the original map the political and economic claims of Denmark are visualized using colours. Green was used for two different purposes; first to mark the network of rivers which were of economic importance both for the Dutch traders in the Kola Peninsula and northern Russia and King Christian, but also for van Salingen’s personal economic interests. The other purpose was to mark different regions of political interest and importance for the Danish crown, such as Hälsingland, Finland and Karelia. The red along the sea shores, lakes and rivers emphasized the most important rivers and seas as transport routes in Finnmarken and the Kola Peninsula. They appear in the territory that was contested in relation to Sweden and Russia. The areas where green and red coincide mark the combined political and economic interests of Christian IV.

It is apparent from van Salingen’s map that he had not visited the area of the Gulf of Bothnia. The place names and ethnonyms that are written on the Swedish and Finnish parts of the map must have been taken from other maps published at this time. They probably also came from people who knew the area because they are correctly placed. It is quite conceivable that van Salingen met Norwegian merchants who had visited the market in Torneå. He could also have met Swedish merchants trading with Sámi, so called birkarlar, who made extensive journeys to the Varanger and Kola Peninsulas at this time. On the Swedish side of the Gulf only a handful of northerly villages appear on the map, together with the most important boroughs in the southern part, but most of Norrland is blank. This lack of place names in most of Sweden emphasizes even more the specific aim of the map: it was the border areas of the Kola Peninsula and the White Sea that were seen as important.

When van Salingen labelled Finland he did so from a Danish and Russian perspective, from the White Sea area. The main part of Finland is therefore named “Oest Finlandia” (Eng. West Finland) because it was located west of the White Sea. The small east–west part near Lake Ladoga was called “Ost Finland” (Eng. East Finland). The central Finnish area, which van Salingen designated West-Finland, was from a Swedish perspective called “Österland” (Eng. the Eastern land) in early medieval times (Tarkiainen Citation2008). The Danish political effort to underline its hegemonic ambitions is obvious in the map. The northern part of the Swedish kingdom, encompassing present-day Sweden and Finland, is shown as extremely narrow and undersized. The northern part of Finland up to the White Sea is dominated by Russian Karelia, written in capital letters, located along the western shore of the White Sea, and another Karelia in small letters on the southern and eastern shore. In addition, the size of the Kola Peninsula is much exaggerated, and over the whole peninsula is written LAPPIA PARS NORWEGIA in capital letters, meaning “Lapland as Part of Norway.” For van Salingen the Kola Peninsula was the same as Lapland, the area to which King Christian IV claimed ownership.

The separation of Kven and Kajana Finns

Two rivers on the map are of specific interest. They run parallel in an artificial way, straight northward from the Gulf of Bothnia, and seem almost to be connected to each other at one point. The western river flows to the Arctic Ocean. The idea of a straight river connecting the Gulf of Bothnia with the Arctic Ocean was current at this time and appears on maps by Lucas Jansz Waghenaer in 1585 and Jan Huygens van Linschoten in 1601 (Ehrensvärd Citation2006, 112, 117–123). The westernmost of the two rivers in van Salingen’s map originates in that idea, but it does not go straight northwards to the Arctic Ocean, as in Waghenaer’s and van Linschoten’s maps. Instead, it bends to the northeast and empties into a large lake, identifiable as Lake Inari, before continuing to the Arctic Ocean.

The eastern river connects to the network of rivers on the Kola Peninsula, which fits quite well with the Kemi River, an interpretation suggested by Kyösti Julku (Julku Citation1986, 117–118). However, a closer look at the map reveals that the place name at the mouth of the eastern river (the one Julku thought was the Kemi River) is “Thorn”, which means “Torneå”, and beside the western river is written the name “Chalis” for “Kalix”. One can see on the map that the Kalix River is surrounded by mountains on both sides of the river, which corresponds to how the hilly countryside up-river looks in reality. In reality, the Torne and Kalix Rivers are interconnected by the Tärendö River, a natural phenomenon that must have been well known to the people van Salingen met. This is probably why he allowed the two rivers to interconnect, even if only in a vague way and in the wrong place geographically. The two rivers are therefore a combination of an economic, geographical and cultural outlook: geographically they are a wrongly represented combination of the Kalix, Torne and Kemi Rivers, culturally they depict the Kalix and Torne Rivers.

When studying the naming of ethnic groups and place names it appears that van Salingen used a combination of Norwegian, Swedish and Dutch vocabulary reflecting the multilinguistic and as yet not standardized character of the Northern areas in that time (see , a detail from van Salingen's map). At the mouth of the Kalix River is written “Nort bottem,” and at the mouth of the Torne River “oost bottem,” a little further south on the eastern shore “ost Bodem,” and on the western shore “West bodem,” naming the provinces of Ostrobothnia and Västerbotten in Dutch.Footnote14 On the other hand, he uses the Norwegian term “Vinnen” (Nor. Finns) for the Sámi on the Swedish side of the Gulf of Bothnia, but spelled in Dutch/German. West of the Kalix River one can discern the place names “Lulla Vinnen” (meaning Lule Sámi), and below “Peta Vinnen” (meaning Pite Sámi). Far above Lulla Vinnen is written “Seg” (meaning Siggevare Sámi village).

Figure 2. Detail from the copy of Simon van Salingen’s map of Scandinavia. Source: Digital copy of Simon van Salingen’s map of Scandinavia (1891) (curtailed). The A. E. Nordenskiöld collection, the National Library, Helsinki.

Concerning the issue of the Kvens, it is interesting that van Salingen has written “Querrnen finnen” between the Kalix and Torne Rivers, and “Kaÿenske finnen” east of the Torne River. The difference between the two kinds of Finns probably arises from the different history of the two groups. The Querrnen finnen represented the Kvens who were recognized from ancient times as fishers and Lapland travellers in the area of Tornedalen. The first known Kvens who settled in Vadsø in North-Norway are registered in the census of 1595–1596 under the ethnonym Querrner (Niemi Citation1983, 103). This is convincing evidence that Querrnen finnen actually designates the Kvens living between the Torne and Kalix Rivers on van Salingen’s map.

Typical of van Salingen’s linguistic mix is the use of the Norwegian ethnonym Querrnen and their Swedish ethnonym Finns. The Kaÿenshe finnen were recognized as the Finns in Ostrobothnia, an ethnic group of people that was established in the north as part of the expansion of the Swedish kingdom, no earlier than the fifteenth century (Keränen Citation1984). The text Querrnen finnen is placed east of the mountains of the Kalix River and thus east of the language boundary between Swedish and Finnish, described in the early eighteenth century by Carl von Linné (Linné Citation1969 [Citation1732]). This language boundary had already been mentioned in the seventeenth century by the Swedish antiquarian Johannes Bureus (1568–1652) when he commented about Torneå that: “Thär är alt finskt folk” (Eng. There are only Finnish people) and under the label “Insignia” he wrote: “Kalijs – Lappar, Torne – Finnar” (Eng. Kalix –Laps, Torne –Finns) (Bureus Citation1886 [Citation1651], 183, 224). In the latter comment the point is that Finns were contrasted to the Sámi, stressing the ethnic contact zone between the Torne and Kalix Rivers, declaring at the same time that those living in Tornedalen were Finns, not Swedes.

One might ask why van Salingen separated the Kven Finns and Kainuu Finns on each side of the Torne River. The general belief at this time was that rivers united, not separated cultures and ethnic groups. In the early seventeenth century Tornedalen was bound together by a common Finnish language and culture. One must remember, however, that van Salingen’s map served a marked political agenda.

From a Norwegian perspective the Kvens belonged to the cultural memory of Finnish speakers in the area between the Kalix and Torne River. They were regarded as an “old group” of Finns, while the Kajaani Finns close to the White Sea were regarded as “newcomers”. In the border negotiations with Sweden it was in the interest of the Danish king to keep the “old group” of Querrnen finnen as far away as possible from the disputed area around the White Sea, because they could otherwise be used by the Swedish negotiators to claim a historical right to the White Sea area. By using the ethnonym Querrnen for the Kvens, as a well-defined separate ethnic group of people different from the Kajaani and Karelians, van Salingen supported the Norwegian and Danish view that the Kvens had no historical rights east of the Torne River.

The disputed territory of Kvenland

The Finnish historian Kyösti Julku studied van Salingen’s map as part of a larger work in which he investigated the historiography of the Kvens and Kainulaiset, and how they were represented in maps of the Nordic countries and northern Europe. In comments regarding van Salingen’s map he stated that Kaÿenshe finnen on the map is “kajaanilaiset suomalaiset eli kainuulaiset suomaliset”, meaning “Kajana Finns or Kainuu Finns”, thus using their dual names in Swedish and Finnish and associating them with the Kainuu district in Ostrobothnia.

He then stated that the Kvens (Querrnen on the map) and the Kainuu Finns (Kaÿenshe finnen on the map) were the same, writing in Finnish “Kveenit eli kainulaiset tulevat siis Salinghenin kartassa aivan oudosti oikealle paikalle,” meaning “the Kvens or Kainuu people are, thus, quite strangely put in the right place on Salingen’s map.” He was of the opinion that the Kalix River was settled by the ancient Kainuu people, whom he regarded as Finnish speakers, and therefore equated them with the Kvens (Julku Citation1986, 116–119). The statement is a typical example of the way the ethnonyms of Kven and Kainuu have regularly been fused together. In one way he depicted the Kainuu Finns as equivalent to the Kajana Finns, But on the other hand he depicted them as equivalent to Kvens. All this together created an ancient cultural Greater Finland, stretching from southern Finland to the Kalix River, a magnificent cultural memory of the past.

As mentioned above, the most important regions on the map were marked with green lines. Jämtland is one such green area in the middle of Norrland. The area of the Querrnen finnen, between the Kalix and Torne Rivers, is also surrounded by a green line to mark its importance. It is tempting to associate it with the ancient province of Kvenland. Other areas marked in green are Hälsingland, Finland, Karelia, the Kola Lapland, and the counties of Finnmark and Troms. When comparing van Salingen’s map with the description in Egil’s Saga of the different “lands” one gains an understanding of the saga geography. Van Salingen could not have read the Islandic Egil’s Saga, since the manuscripts were not collected before the end of the seventeenth century, so everything he has shown on the map must have come from oral and written sources, not least from Olaus Magnus. He thus used a combination of communicative and collective memories.

First we must consider how the Scandinavian Peninsula and the Swedish, Finnish and Russian provinces might have been envisaged by the writer of Egil’s Saga in the early thirteenth century. A modern imagination is that the province of Norrland lies north of Götaland and Svealand, but actually it stretches in a northeasterly direction. Medieval writers were of the opinion that the Scandinavian Peninsula stretched eastward from Denmark. Adam of Bremen turned the peninsula horizontally even more, in an easterly direction, and placed the groups of people he heard about according to that geography. The provinces and groups of people fall into the right places when his account is read in that way (Nyberg Citation1984, 317–320). The account in Egil’s Saga fits geographically with van Salingen’s map if we turn the listing of “lands” in the account in a northeastern instead of a northerly direction.

We can imagine that Hälsingland, from a thirteenth century Icelandic perspective, covers the whole of northern Sweden, with Kvenland placed in the northernmost part of the Gulf of Bothnia, followed by a thin strip of (Kaÿenske) Finland along the eastern part of the Gulf of Bothnia and eventually Karelia on the shores of the White Sea. In van Salingen’s map there are wonderful mini-drawings of Karelian villages with detailed and realistically outlined timber houses and Orthodox churches placed along the shores of the White Sea. They fit well with the account in Egil’s Saga of how Norwegians visited Kvenland, and how the Norwegians together with the Kvens had plundered Karelian villages on the shores of the White Sea six hundred years earlier.

Van Salingen’s map was used by Denmark in negotiations about the territory with Sweden and Russia. Charles IX realized that Sweden had to present an even better map to accord with his territorial claims. Therefore, in 1603 the cartographer Anders Bureus was commissioned to draw a map of the Northern areas (Ehrensvärd Citation2006, 128–130). By 1611 he had created a map of Lapland called Lapponiæ Bothniæ Cajaniæque Regna Sveciae Provinciarum Septentrionalium Nova Delineatio scupta anno domini 1611 (). Only ten years elapsed between the publishing of van Salingen’s Scandinavian map and Bureus’s Lapland map, but the difference is considerable. Bureus incorporated into his map an image of the world that was influenced by the modern territorial state, based on modern cartography. Unlike Olaus Magnus and van Salingen he was able to reproduce the system of rivers and lakes in North Scandinavia quite correctly, as well as the extent of the Kola Peninsula and the White Sea.

The place names in Sweden and Finland are detailed and correctly noted (Lönborg Citation1901, 61–62). This map also had an underlying political agenda. It was designed to fulfil the Swedish aspirations and can be seen as a response to the maps that Denmark had created. It is written in the title frame (Swe. kartusch) that Lapland, Bothnia and Cajana are the northernmost provinces of Sweden according to the new demarcation. No particular ethnic groups are specified. He uses Cajania as a designation for the eastern side of the northern Gulf of Bothnia, as distinct from Botnia, which is used for the western side. Lapland stretches from north of Jämtland to the border with Norway and Russia, but is also divided into the different Lap lands (Swe. Lappmarker) in accordance with the administrative units. Kvens or Kvenland are not mentioned anywhere on the map.

In the 1730s Sweden and Norway agreed to demarcate the northern border between the two countries, starting in the middle of Norway. It soon became clear that further investigations had to be made before an agreement could be reached. The mountain range, the so-called Keel, between the two countries had been regarded as the border since ancient time, but when it came to delineating the border line it was not so easy a task. A careful investigation preparatory to any decisisons was carried out in order to discover where a fair border between the two countries should be drawn. The Norwegian border inspector Peter Schnitler was engaged by the Danish royal authorities in the years 1742–1750 to find out where the northern border between Sweden and Norway should be drawn (Schnitler [Citation1742–Citation1745] Citation1962, XX–XXV). In his report, based on written interviews with Sámi, Kvens and Norwegians living in North-Norway, he describes in great detail the livelihood of, and relation between, different ethnic groups. The interviews are examples of communicative memories, based on the interviewees’ everyday experiences, transformed into a written report.

Responding to the information he received from the interviews, Schnitler repeatedly wrote that Qvänland referred to an area in the northernmost reaches of the Gulf of Bothnia, which stretched 80 kilometres north from the town of Torneå. He explained that Qvänland starts 20–25 kilometres west and east of the Torne River and then extends 400 kilometres up to the Norwegian border at Enontekiö. Within this area the first 200 kilometres are inhabited by peasants and mining people, some of whom are conscripted as soldiers for the Västerbotten regiment, and the last 100 kilometres by Sámi. The peasants were said to live along the rivers, of which there were quite a number in Kvenland, and they spoke the East-Finnish language (Schnitler [Citation1742–Citation1745] Citation1962, 348, 360, 386, 388, 410–411). According to Schnitler's possessive report it was a multicultural area comprising both Finnish and Sámi speakers, not one inhabited by a single ethnic group. In the middle of the eighteenth century the name of the province was still in use in northern Norway, but only north of Ofoten, the area where for many centuries Finnish speakers had used the Atlantic and Arctic Ocean for fishing and trading with the Sámi (Niemi Citation2014, 257–270). Kvenland at this time was clearly situated in present-day Tornedalen in Sweden and Finland.

The language of the Kvens

A crucial question is whether the Kvens had possibly switched languages from Swedish in the ninth century to Finnish in early modern times. It is definitely possible for a small population to change language and culture within a period of six hundred years, under conditions of serious warfare or migrations, as during the time of the Great Migration in central Europe (Heather Citation2009). The neighbouring Sámi-speaking population in southern Finland did so in the Middle Ages, for example. They were assimilated by the Finns or forced to retreat northwards. Sámi is only spoken today in northernmost Finland (Itkonen Citation1947; Tegengren Citation1952, 232–273). This is a case of a Sámi hunting people meeting a Finnic farming people.

In the northernmost area of the Gulf of Bothnia the Sámi people met both Finnic and Scandinavian peoples, who combined farming with fishing and hunting, and settled along the coast. When Olaus Magnus visited Tornedalen in 1519, farming and agriculture had spread far up the river valley. In one passage he writes that “ … the Laps, or Bothnians, and forest people … .have a specific language, not much known by other neighbouring people” (Olaus Magnus Citation1976b, vol.1, 180–181).Footnote15 The neighbouring people he refers to must be Swedes, Norwegians or Russians, if they were not Finns. It is impossible to deduce from his writing what language the farmers in Tornedalen spoke. When van Salingen, in his 1601 map, named the people between the Kalix and Torneå Rivers Querrnen finnen, and Johannes Bureus in the same century wrote that there were only Finnish people in Torneå, it is obvious that it was a Finnish speaking district. The farmers must also have used the Finnish language when Olaus Magnus visited them, but it was probably so obvious that he did not mention it.

It is impossible to imagine that a Swedish-speaking community, connected to a Scandinavian culture of extreme military expansion in the Viking Age, should totally have changed its language and culture from Swedish to Finnish, not only at the mouth of the Torne River but also upstream of all its tributaries. Thereafter, this former Swedish population should have started to call their former ethnic compatriots in the lower part of the Kalix River for Kainulaiset, as a group separate from them. If we further take into consideration that the Finnic culture in Tornedalen is archaeologically manifested for the first time in the eleventh century in the form of rye cultivation, we must accept that the language shift must have taken place earlier, i.e. during the generations from perhaps the seventh to the eleventh centuries. This is implausible.

The distinct language boundary between Finnish and Swedish at the mouth of the Sangis River seems to have been established when the Swedish speakers encountered a well-established Finnish-speaking population there. It fits in with the burial mound of a Scandinavian warrior from the Viking Age; use of the site is dated to two periods, AD 600–800 and from AD 1070 (Ramqvist and Hörnberg Citation2015). The Viking burial separates the area around the mouth of the Kalix River, dominated by Swedish speakers, from that around the mouth of the Torne River, dominated by Finnish speakers in the Middle Ages. The Finnish speakers in Tornedalen previously called the Swedish speakers in the lower part of the Kalix River valley Kainulaiset. The Swedish speaking Kainulaiset were, thus, ethnically separate from the Finnish-speaking Kvens in Tornedalen (Elenius Citation2018b).

We can also see the remains of a narrow band of Finnish speakers in the coastal area south of the Sangis River, manifested in former Finnish substrates in coastal place names like Ryssbält, Pålänge, Vånafjärden, Kallax, Rosvik and Hortlax, but no substantial remnants of a surviving Finnic population (Pellijeff Citation1980, Citation1988, Citation1990). On the economic and topographical map of Överkalix, there are also many Finnish forms of lake names such as -järvi and -lompolo that have later become Swedish in the hybrid forms of -järv and -lomb. This shows that the lakes were named by Sámi and Finns before the Swedes established permanent farms (Pellijeff Citation1980, Citation1985; Wahlberg Citation2016).

The ethnic contact zone in the county of Norrbotten, demonstrated by Finnish and Sámi place names, follows the Torne and Kalix Rivers with their tributaries. More precisely it was the Finnish encounter with Swedish settlers in the lower part of the Kalix River, and a corresponding encounter in the upper part of the Lule River, that stopped the Finnic expansion westward. This is clearly demonstrated by the fact that Finnish lake names with endings such as -järvi and -lompolo, and also with the Finnish-Swedish hybrid forms -järv and -lomb, stop almost exactly at the western border of the municipality of Överkalix (Elenius Citation2018b). It demonstrates that the Finnic cultural influence on the Sámi culture stopped there. On the other hand, the Finnic influence on place names continued along the tributaries of the Torne and Kalix Rivers upstream beyond the Lapland border. In the municipality of Gällivare, above the Lapland border, there are 875 place names with the Finnish ending -järvi and 390 names with the ending -vaara (Eng. hill). In the municipality of Jokkmokk, south of Gällivare, there are only four järvi-names and four vaara-names (Elenius Citation2019), showing that the Lule River, which stretches into the municipality of Jokkmokk, was mainly colonized by Swedes. The boundaries of the ethnic contact zone between Finnic and Swedish settlements corresponds exactly to the location of Kvenland as described by Schnitler in the mid-eighteenth century.

The hypothesis that the Kvens had a third language, between Sámi and Finnish, is also not supported by the ethnic contact zone between the Finnish and Sámi languages. From the findings it is evident that the Finns encountered Sámi who were the first to give place names to the landscape. There is clear evidence of the co-existence of Sámi, Finnic and Scandinavian cultures in the coastal and inland areas during the long period when place names were established. However, the evidence regarding the language shift points in another direction than that emphasized by K. B. Wiklund, moving from Sámi to Finnish and eventually to Swedish. The Sámi were gradually assimilated into the other two groups of people in the coastal and adjacent inland areas.

There is also a special relationship between the Tornedalians and Sámi regarding the owning and herding of reindeer, indicating a long history of exchange. In a report from 1815, the district medical officer Henric Deutsch noted that the farmers in northern Finland looked after the reindeer themselves, but in Tornedalen they always hired Sámi to do that work (Deutsch Citation1970 [Citation1815]). This cultural distinction between Tornedalen and northern Finland also signifies a long lasting historical pattern among the “Qerrnen Finnen”. Another example of the persistence of the traditional use of reindeer in Tornedalen is that, in the Swedish reindeer herding legislation of 1928, the Tornedalians were the only ethnic group, apart from the Sámi, who were allowed to own reindeer, with the rationale that they needed the animals in farming and forestry (SFS Citation1928:309; Jernsletten Citation2007). An enduring and continuing pattern of exchange between the Finns and Sámi seems to have existed in Tornedalen. Taken together, the chain of communicative and collective memories documented above supports the idea that there is a continuing Finnic culture in the northern Gulf of Bothnia area, extending from the time of Ohthere to that of Schnitler.

Conclusions