Abstract

Today, melancholia is no longer used as a separate clinical picture in psychotherapeutic diagnostics. Instead, the symptoms are subsumed under major depression or dysthymia and understood as a disease concept. In both Freud's interpretation and in the artistic, Islamic, poetic, and medical-historical approaches in Turkish culture, melancholia is understood in a richer way than just in terms of a “disease-like disorder.” This article aims to emphasize the broader understanding of melancholia within the Turkish-Islamic context and illuminate intersections with psychoanalysis. Since the Islamic faith occupies an important place in the treatment and popular understanding of mental disorders both historically and to the present day, religious and mystical aspects related to melancholia are also considered in this article. A case vignette of a melancholic migrant woman with Turkish roots is used to trace the psychodynamic movements in her treatment. In order to follow this patient’s psychoanalytic process, the theoretical explanations in the first part of the article provide the sensibilization for a deeper understanding of the cultural and religious aspects important to the inner dynamics of this woman.

Melancholia – insights into the Islamic tradition and the Turkish language

Dolab-i Muhammediye (the Mohammedan wheel), a famous water wheel in the Syrian city of Hama, symbolizes the love for the Prophet Hz. MuhammedFootnote1 in the Muslim cultural area and is also considered a symbol of transcendent love, spiritual pain, and passion (Alvan, Citation2020). According to Islamic tradition, this waterwheel began to turn, after a long standstill, having heard a request from a Derviş, a Sufi master, to “turn out of love for Muhammed”: “Muhammed aşkına dön!“ (p. 451). At the same time, the huge crashing and squealing of the huge water wheel was heard all over the country. According to Alvan's description, its specific sound symbolized the wailing, moaning, and whimpering of a person suffering from transcendent love and longing, and the water running from its containers was reminiscent of his tears. The turning movement of the water wheel also has a specific meaning and alludes to the timelessness and unpredictability of the belief in fate anchored in Muslim understanding (cf. Çarkı Felek, the wheel of fate).

Even the famous Ottoman Turkish mystic Yunus Emre (Citation1986, p. 72f.) referred in his religious poems to the water wheel, which whimpers and sighs out of love and longing for Mevlâ, a name of Allah.Footnote2 Through his poems Emre lets us know that transcendent love and longing in Muslim understanding are always connected with inner pain. In addition to this religious meaning, the water wheel is also found in Ottoman Turkish divan literature. Here it expresses the painful longing for love between a couple (Emre, Citation1986). This particular literary genre is called Dolab-nâme (cf. Alvan, Citation2020) and is also found, for example, in traditional folk songs, here often in the form of an image of a mill (Değirmen).

This painful emotional and mental state of the soul coupled with a religious experience of love is strongly rooted not only in the Muslim world, but also in Christianity. The psychoanalyst Kläui cites Akedia, the midday crisis of faith, as an example of the early monks' longing for God and search for God, as “the phenomenon of deep despair in which unreadability and death meet” (Kläui, Citation2018, p. 74). The monks went into the desert in their expectation of being able to experience God and fell into a state of inner emptiness and immobility in the demonic midday heat. Kläui interprets this state as the “unreadability” of signs and relates it to our present time, in which the so-called “midday demon” (p. 76), through accessing of science, technology, and consumption, has made the “things meaningless and mute” (p. 76).

If we look at the Turkish language (often with Arabic word stems), we can see that there are many different terms for mental pain and suffering, depending which aspect of the pain is focused upon. Gam (prolonged grief), Keder (sorrow), Izdırap (excruciating suffering), Acı (pain), Sızı (a breath of trembling pain), Dert (worry), Çile (suffering), Efkâr (rising of sadness and at the same time intoxicating emotion), Hüzün (blues), Yas (mourning process), Üzüntü (grief, dejection), and many more. The variety of terms for inner pain reflects the multifaceted nature of melancholia. In many folk songs and poems, for example, these terms of pain occur and can make the mood of melancholia palpable when listening to them. Accordingly, melancholia is deeply rooted in Turkish culture, as well as in the performing arts, in which it is the motive for many Turkish artists, to which I will refer in the later part of this text.

Perspectives from the Islamic/Ottoman medical history

In the psychiatric medical history of the Turkish-Muslim cultural area, the clinical image of depression was for a long time closely associated with the rich understanding of melancholia. This painful state of mind was thus not understood and used exclusively under the aspect of illness, but embedded in the individual life and cultural history of the suffering person.

In the epoch of the end of the Ottoman Empire and the emergence of the Turkish Republic at the beginning of the twentieth century, historical psychiatric literature used the term Mȃl-i Hülya for severe depression, which was translated by Arab scholars from the Greek melancholia (melas = black and cholia = gall). The Greek philosophers, among them most famously Hippocrates, associated melancholia with an organ. In his four-humors theory Hippocrates attributed to melancholic people a dysfunction of the bile. The similar sound of the Turkish Ottoman term Mâl-i Hülya, when pronounced, to “melancholia” is striking. Hülya – also used as a girl's name – has a nice connotation in everyday speech and means rêverie in the sense of daydream and fantasy or even illusion. Although the pronunciation of Cholia (bile, gall) and Hülya (daydream, illusion) is similar, the Ottoman Turkish term encompasses more the psychological dimension of melancholia rather than the organic.

This understanding of melancholia in relation to an organ is evident both in the early works of the Turkish Arab scholar and physician İbn Sînȃ (980–1037), for example in his famous work El- Kānûn fi't Tıbb (Citation2018) [The canon of medicine], and later in the works of the early psychiatrists of the Turkish Republic from the 1920s onward. However, the two approaches differed in their perspective on symptomatology, etiology, and therapy. Turkish psychiatrists of the young republic, first and foremost Mazhar Osman, attributed melancholia in the clinical sense of depression almost exclusively to organic and substance-induced dysfunctions. He stood with his closest circle of colleagues in Kraepelin's tradition due to stays abroad in Europe. Hence, they tried to cure exclusively by means of neurobiological concepts and drug therapies. In this understanding the psychiatrist and neurologist Fahrettin Kerim Gökay (Citation1939), who studied in Vienna for some time at the beginning of the twentieth century, attributed liver insufficiency as major cause of melancholia and attempted to capture this clinical picture on a biological level.

Early Islamic scholars, on the other hand, associated melancholia, in addition to organic connections, also to unfulfilled and sensual desires, as did İbn Sînȃ in his treatment of a young man suffering from love melancholia (cf. Usak, Citation2015). Mecnun was the term used to describe “lovesick men” who fell into a depressive/melancholic state out of unsatisfied desire for an unattainable love object. The term Kara Sevda (black desire) (cf. Usak, Citation2015) – was also used as a synonym for “love sickness” (cf. also Artvinli, Citation2017). It is striking that the color black (kara) is included in this term, as it is in melancholia. Moreover, Muslim physicians and scholars, such as the philosopher El-Farabi (872–950), did not exclusively apply medical therapies, but also recognized the effects of suggestion and Ottoman/Oriental music as therapeutic measures. One of the most important contemporary practitioners and scholars in the field of Turkish (shaman and sema) music and psychotherapeutic approaches was Rahmi Oruç Güvenç (Citation1985), who, for example, describes which makame (key in Turkish sanat muzikisi – art music) has a healing/alleviating effect for which ailment.

Martin Pappenheim, a psychiatrist and neurologist from the Western cultural area and father of the psychoanalyst Else Pappenheim, also recognized the influence of the Muslim faith on the psychological processing of difficult social conditions and inner conflicts. In a highly interesting historical document from 1918 entitled Über Kriegsneurosen bei türkischen Soldaten [On war neuroses in Turkish soldiers], he writes about culturally conditioned manifestations of neurotic states in wounded Turkish soldiers who were serving at the East Galician front. His account is based on clinical observations and treatments in a reserve hospital of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy.

In contrast to his experiences with European soldiers, there was no tendency toward “theatrical manifestations”Footnote3 (Citation1918, p. 313) in his patients. In his essay, Pappenheim observes an “apparently conspicuously low percentage of neuroses among the Turkish Mohammedans” (p. 312). He assumes that the cause is “perhaps to be sought in part in certain differences of temperament and worldview,” since “the Turk is said to have a certain phlegm and a fatalistic view of life” (p. 313). This fatalistic worldview is part of the Islamic faith and helps believers in difficult situations to Sabır (patience) and Sükunet (inner calm) (cf. also Bulut et al., Citation2021). However, the “phlegmatic temperament” (p. 313) that Pappenheim attributes to Turkish soldiers and evaluates as a power of resistance could also indicate a tendency of the Turkish-Muslim collective to melancholia, which is subtly intrinsic to this cultural group throughout very long eras of poverty and war.

Psychoanalytic approaches to melancholia

Taking another look at the metaphor of the water wheel with its containers, which is predominant in the Muslim world, the remarks of psychoanalyst Jutta Gutwinski-Jeggle (Citation2017) hint at a similar understanding of depression. Following Bion's psychoanalytic thinking, Gutwinski-Jeggle writes about vascular metaphors, which she draws upon as helpful concepts for a closer understanding of depression in relation to language, the phenomenon of time and its disruption, and also the body.Footnote4 In doing so, she elaborates on depression, titling it a “disease of time” (p. 211). In the melancholic/depressive state – both terms are used here largely synonymously – “the person lives in the past, the present is empty of meanings, and there is no future” (p. 185). Gutwinski-Jeggle considers the origins of depression, among other factors, in processes of disturbed symbolization in the child, whose frustration tolerance was exceeded by too long an absence of the satisfying object. Even though she describes depression as a “disease” in her remarks, creative-sensual language images permeate her lines, revealing the creative nature of melancholia. It should be noted that the symbolism of the water wheel or the mill in standstill or in uninterrupted rotation also symbolically points to the connection of timelessness, a thinking loop, as well as the experience of emptiness in the present.

In his seminal essay “Mourning and Melancholia” [Trauer und Melancholie], Sigmund Freud takes a closer look at these painful feelings. While he sees mourning as “regularly the reaction to the loss of a loved person, or to the loss of some abstraction which has taken the place of one, such as one's country, liberty, an ideal, and so on” (Citation1917, p. 243), he relates melancholia to an “object-loss which is withdrawn from consciousness” (p. 245). Freud argues further on that, in melancholia, there has been “an attachment of the libido to a particular person,” but then through “a real slight or disappointment coming from this loved person, the object-relationship was shattered (p. 249). In this case, “the free libido was not displaced on to another object; it was withdrawn into the ego” (p. 249), Thus, there is “an identification of the ego with the abandoned object” (p. 249, original emphasis) and the “shadow of the object fell upon the ego” (p. 249). Freud continues to write in “Mourning and Melancholia” that “we find the key to the clinical picture: we perceived that the self-reproaches are reproaches against a loved object which have been shifted away from it on to the patient's own ego” (p. 248). Now the lamentations, sighs, moans, and groans of melancholics also become more understandable, for their “complaints are really ‘plaints'” (p. 248) against the lost object.

Accordingly, these described ambivalent love experiences, which are handled in creative processes in literature and in art as well as in many other cultural assets in a close connection with pain, were experienced by their melancholic creators. Namely, the libidinal occupation existed in the earliest moments of their biography, although these were, however, lost due to a mortification, but reappear in their works of art. The Bulgarian-French psychoanalyst Julia Kristeva (Citation2007) sets the focus in her book Schwarze Sonne. Depression und Melancholie [Black sun. Depression and melancholia] not on the “lost object” but on the Lacanian concept of the real (Lacan, Citation1981 [2021]). By this Kristeva opens an area in clinical understanding that focuses on creativity, like the religious as well as the artistic understanding of melancholia. In doing so, she establishes the reference to the feminine, according to which in melancholia the meaning of mother relates to the “death-bringing woman” (Citation2007, p. 36). At the same time the successful/failing “matricide” (p. 36) is analyzed as a necessary condition for individuation or its failure.

Referring to the real in relation to creativity and the unconscious, the Turkish poet Necip Fazıl Kısakürek comes to mind. He succeeds particularly well in making the real tangible as a mood in his largely religious poems. His art connects the melancholic experience with death, the suspension of space and time, and also transcendental longing. Especially in his poems Ölüm güzel şey (1977) [Death is a beautiful thing], Uyumak istiyorumFootnote5 (n.d.) [I want to sleep] and Beklenen (1937) [The one you wait for], the latent forces of thanatos are raised up, interwoven with the sweet taste of melancholia.

Similarly, in his book Die tote Mutter [The dead mother], Cairo-born French psychoanalyst André Green (Citation2004) refers to depressive/melancholic states of mind, which he describes as “black” (the heaviness) and “white” (the emptiness, the negative) depression, which create “psychic holes” in the unconscious. He not only understands these inner states in terms of a “lost object,” but focuses on the absent in the present as a possible cause of the depression, as in the case of a no longer emotionally accessible mother in severe mourning for her child. His remarks remind me of a depressed patient in my practice, who was the mother of an infant and told me that she “no longer laughed with her heart, but only with her mouth.”Footnote6

Migration – melancholia – femininity

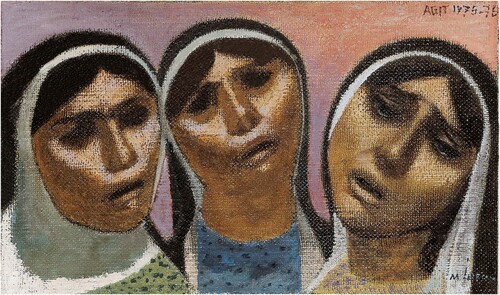

Like withered flowers, the women in the painting by Turkish artist Nuri İyem (1915–2005) are depicted in melancholic despair (). Their heads are bent to the side, their sad looks and the downward-moving corners of their mouths reminding me of many women in my clinical practice. Often their state of suffering is related to drastic migration experiences, aggravated family dynamics, and also stressful social conditions. The loss of the old homeland, of family members and parts of one's own (childhood) history, can be reflected in melancholic or depressive symptoms. As Sigmund Freud in his essay “Mourning and Melancholia” spoke of the “object-loss” (Citation1917, p. 245), which is unconsciously/unmournfully introjected and leads to melancholia, the artist Nuri İyem creates in his works such soulful portraits of women from his “outer and inner homeland”. In particular, as a small child, he had lost his older sister, who had also assumed a mother role for him.

Figure 1. Nuri İyem (1915−2005), Ağıt, 1975–1976. Source: https://melikeaycaguzel.blogspot.com/2014/07/yuzlerde-yansyan-toplum-nuri-iyem-resmi.html

The emigrant couple Rebeca and Leòn Grinberg (Citation1990 [Citation2016]) wrote a standard work on the psychodynamic effects of migration and exile, entitled Psychoanalyse der Migration und des Exils [Psychoanalysis of migration and exile]. In their work they elaborate on the connections between migration and the depressive complaints of migrants. The Grinbergs speak of the “skipped mourning” (übergangene Trauer) (p. 106) of the emigrants, when forms of defense such as an over-adaptation to the receiving society or idealization of the abandoned homeland make mourning impossible and thus depressive states more likely (cf. also Volkan, Citation2017).

As a result of the Turkish guest worker movement – beginning in 1964 in Austria – profound changes have taken place in the lives of the emigrant parents and their children. Due to the hard work of the mothers/parents, it was common to send the children back and forth between Turkey and the “guest country” Therefore, in the parents' generation, but especially in the children's generation (the second generation), feelings or unconscious early experiences of inner fragility, imperfection, and fragmentation have remained. These inner states can experience an unconscious transmission to later, to the third or fourth generation, as long as they remain unconscious (cf. also Faimberg, Citation2009; Kogan, Citation1998). The first generation followed the ideal of working and earning money and had no possibilities for pausing and reflecting. According to my clinical observations and reflections, to their “skipped mourning” is to be added an “overlooked mourning” (übersehene Trauer) of the children's generation, which today shows itself in them as adults in states of depression/melancholia.

shows the cover of the book Die vergessenen Kinder der Globalisierung [The forgotten children of globalization] (Rohr et al., Citation2016), which touches me greatly every time I look at it, because it aptly depicts the painful experiences of the children of that time, which can also be heard again and again in the psychoanalytic field as painful memories of today's adults. In Turkish, Yolunu gözlemek is literally translatable as “to direct one's eyes to the path” – whether on this path the distant father or the longed-for mother will one day appear.

Figure 2. Die vergessenen Kinder der Globalisierung [The forgotten children of globalization]. Cover of: Rohr, E., Jansen, M. M., & Adamou, J. (Eds.) (Citation2016). Die vergessenen Kinder der Globalisierung. Psychosozial-Verlag. Source: https://www.psychosozial-verlag.de/catalog/images/products/onix/9783837923520.jpg

![Figure 2. Die vergessenen Kinder der Globalisierung [The forgotten children of globalization]. Cover of: Rohr, E., Jansen, M. M., & Adamou, J. (Eds.) (Citation2016). Die vergessenen Kinder der Globalisierung. Psychosozial-Verlag. Source: https://www.psychosozial-verlag.de/catalog/images/products/onix/9783837923520.jpg](/cms/asset/669bb8c7-3b36-40ea-8bff-3d238ff185e5/spsy_a_2303060_f0002_oc.jpg)

The members of the first generation of the Turkish guest worker movement are today about 70–80 years old and are currently in Turkey for most of the year, going for only short periods of weeks or months to their former “host country,” Austria. However, many of them have already lost their lives due to their age. Thus, I hardly see the members from the first generation in my practice, but they are very present in the associations of their children in adulthood.

Most of my patients are former second-generation children, who were either born in the “host country” or, as already described, were (re-)brought from Turkey to Austria in their childhood/adolescence. Some of the girls sent back and forth came (again) to Austria in their early adulthood as marriage migrants, into the pre-migrated family system of their then also young husbands. Thus, they (again) lost their parents/grandparents and (again) left the familiar, at times when they have needed secure attachments the most. The artwork Uğurlama (leave-taking) by Nuri İyem () symbolizes a scene, which all these young women had experienced, as they came to Austria as marriage migrants and were bid farewell by their parents or grandparents. These narratives are imbued with melancholia.

Figure 3. Nuri İyem (1915−2005), Uğurlama [Leave-taking], 1967. Source: https://www.leblebitozu.com/anadolu-kadin-portreleriyle-taninan-nuri-iyemin-16-eseri/

![Figure 3. Nuri İyem (1915−2005), Uğurlama [Leave-taking], 1967. Source: https://www.leblebitozu.com/anadolu-kadin-portreleriyle-taninan-nuri-iyemin-16-eseri/](/cms/asset/1c4939ef-5fe9-4a68-ac50-0bea3d7c538f/spsy_a_2303060_f0003_oc.jpg)

Most of these middle-aged women (mostly between 45 and 55 years old today, having been born in the late 1960s, 1970s, or early 1980s) consult me not with the knowledge that they are going to a specifically psychoanalytic practice, and not harboring the desire to process their life history from the outset, but because of a current pressure of suffering and a rough knowledge of my profession in the psychic field. The psychoanalytic framework must first be explained by me and subsequently experienced by the women in the process of therapy. My linguistic and cultural background and finally my gender makes it easier for many women to visit my practice, since burdened, often shameful, and generally very intimate topics can be addressed more freely from woman to woman in the mother tongue.

In the life stories of almost all these second-generation women, a common strand is discernible: first, the rupture in the life story caused by the migration event itself; second, the fragility of relationships with primary caregivers, especially parents and, in some cases, siblings; and third, an inner-psychic experience of “fragility” or “deep grievance” (burukluk or kırgınlık). In every single life story of these women, experiences of separation and pain, which had a particularly precarious impact on the primal sense of trust, can be heard. These women grew up without their parents for certain periods of time, sometimes for years, being with relatives in Turkey. They were often placed in the care of relatives as babies or toddlers, and as older children/adolescents had to experience separation again, this time from their caregivers in Turkey, often from grandparents, when they were brought back to the “host country.” Often, during the time of being sent back and forth, there happened also to be separations among the siblings.

One female patient, for example, “remembered” being left behind as an infant/toddler, with the narrative that she had lived “wrapped up” for five years with relatives in Turkey (in rural areas of Turkey, babies were wrapped in a so-called kundak, but not for several years). Then, when her mother came to Turkey for a visit, she relieved her of these cloth bandages, while, according to her reminiscence, the patient could only walk staggeringly for a while afterwards. The distortion of the time length of five years in this memory or narrative makes clear the dimension of her unconsciously perceived developmental stop. She felt trapped, immobile, and abandoned all those years without her parents. The image of a staggering gait points to the perceived absence of her “psychological backbone,” her parents.

In other life stories, the abrupt weaning is associated with the departure of the parents, especially the mother. Many of the infants and toddlers were in fact separated from their mother's breast from one day to the next as she set off for the far country. Süt'ten kesilmek (to be cut off from the milk) is the Turkish name for weaning and in this context aptly describes the “cutting” experience of the sudden absence of the mother which these children were exposed to and had to endure in a helpless manner.

This early “break” or “cut” in the migration history as well as the inner-emotional “fragility” have an effect in adulthood in the way many second-generation women describe the relationship with their old or deceased parents as not consistently trusting or as ambivalent. “Bir soğukluk girdi aramıza“ (“A coldness has come between us”) or “Isınamadım onlara” (“I have not been able to warm up to them”) are exemplary phrases of the second towards the first generation. Accordingly, the lack of inner closeness or the inner distance is described with sensations of the skinFootnote7 as the primary organ of attachment, indicating the earliest cutaneous phase of life in which their basic conflict seems to be fixed. At the same time, these narratives are imbued with a wistful melancholia of never having lived these early times together, and the window of time having closed for forever.

In psychoanalytic processes in my practice, it has become apparent that the technique of indulgent narratives or dreaming associations, as described by the American psychoanalyst Thomas Ogden, can be very helpful and unifying when faced with the forms of fragility experienced by the soul. Ogden writes in Conversations at the Frontier of Dreaming:

The internal conversation known as dreaming is no more an event limited to the hours of sleep than the existence of stars is limited to the hours of darkness. Stars become visible at night when their luminosity is no longer concealed by the glare of the sun. (Citation2001, pp. 4f.)

With this example I want to describe the unifying character of these reveling associations – here we can also speak also of rêverie (Bion, Citation1962). This connecting function of rêverie shows itself also in my countertransference reactions/sensations, and thus it implied an effectiveness in working through the feelings of “inner fissures and fragmentations.” The patients themselves also describe as beneficial this kind of revealing associations in our conversations about their former time in Turkey (maziye dalmak – diving into the past) .

In the following case vignette, I present a woman in a melancholic state of soul, whose life story is marked by the rupture of an early migration with the associated experiences of loss. My focus in treatment was also directed to the unconscious pre-Oedipal/Oedipal desires of this woman, whose physical and psychical existence was threatened by the “shadow of the father” and the “silhouette of the mother.”

The melancholia of Mrs. K.

Haykırmak istedim, haykıramadım. Sesimi duyuramadım (“I wanted to scream, but I could not. I could not let my voice be heard”)

Figure 4. Nuri İyem (1915−2005), Haykırış [Pleading/pain-filled cry], 1967. Source: Anbarpınar, Elif (2012): Türk Resminde Melankoli (1960–1980), p. 98. T.C. Cumhuriyet Üniversitesi, Eğitim Bilimleri Enstitüsü, Güzel Sanatlar Eğitimi Ana Bilim Dalı, Resim-İş Eğitimi Bilim Dalı. Yüksek Lisans Tezi [Melancholia in Turkish Painting. Cumhuriyet University, Institute of Educational Sciences, Department of Fine Art Education, Department of Painting and Drawing Education, Master Thesis]. https://tez.yok.gov.tr/UlusalTezMerkezi/tezSorguSonucYeni.jsp

![Figure 4. Nuri İyem (1915−2005), Haykırış [Pleading/pain-filled cry], 1967. Source: Anbarpınar, Elif (2012): Türk Resminde Melankoli (1960–1980), p. 98. T.C. Cumhuriyet Üniversitesi, Eğitim Bilimleri Enstitüsü, Güzel Sanatlar Eğitimi Ana Bilim Dalı, Resim-İş Eğitimi Bilim Dalı. Yüksek Lisans Tezi [Melancholia in Turkish Painting. Cumhuriyet University, Institute of Educational Sciences, Department of Fine Art Education, Department of Painting and Drawing Education, Master Thesis]. https://tez.yok.gov.tr/UlusalTezMerkezi/tezSorguSonucYeni.jsp](/cms/asset/9c625136-6204-4c9f-a0c9-9a7929c0aab4/spsy_a_2303060_f0004_oc.jpg)

The story of the life and suffering of my patient corresponds in some aspects to the collective experiences of many Turkish women under psychosocially, educationally, and economically more difficult living conditions. This is above all true regarding the (sub)cultural and generational characteristics of the living environment of many migrant Turkish women. Her statement “Haykırmak istedim, haykıramadım” (“I wanted to scream, but I could not”) also reflects the desire for a fervent cry, which, however, had to remain unfulfilled in silence for years. Despite these striking collective elements, the psychoanalytic process also revealed deeper traces of an individually experienced relational constellation and dynamics in this woman's life. I would like to elaborate on these aspects and her inner-psychic conflicts against the background of her “unconscious singularity.”

The biographical incident of the early death of Nuri İyem's sister gave me a clue in the psychoanalytic process of understanding my patient's soul. Nuri İyem encountered death and mourning very early in his life, when he lost his sister, who had taken on the role of a mother for him, as a small child. The psychic loss of a beloved object accompanies the life of my patient as well, accompanied by disappointment, mortification, and consequently a “disturbance of self-regard” (Freud, Citation1917, p. 244) – the most important distinguishing feature between melancholia and mourning – and an almost incessant pain.

Mrs. K. is 37 years old when she starts treatment, has two sons (a toddler and a boy at the beginning of puberty), and has been married for 13 years. She is the fourth of six children and has three older sisters, after her coming another sister, followed by a brother who is a “latecomer” (seven years difference from the preceding sibling). The sisters were each born with a one-year age difference. The patient migrated to Austria with her mother and sisters when she was eight years old. The youngest child was born in the country of migration. Her father had already been in Austria for three years at the time my patient arrived in this country. The psychoanalysis was conducted in the Turkish language.

Mrs. K. consulted me a few months after a stomach operation, which she undergone to reduce her weight. She had then gone through a very difficult time with a rapid loss of body weight and inflammation in the abdominal area, accompanied by a feeling of deep sadness and futility.

The beginnings of the psychoanalytic process

The very pale, thin, and “pitch black” dressed woman says in the initial interview that she had had an operation on her stomach about one a half years ago. Afterwards she had lost too much weight too quickly and also had inflammation in the abdominal region. In total, she had lost over 50 kilograms (100 pounds). In this first hour she also talks about her husband, how unemphatic, frustrated, and self-centered he is and how he makes her life difficult. During her narration, in my mind's eye there is the image of a small child, raging, ranting, and “pouring” her own undigested/unbearable inner world into the primary person. Despite her initially negative descriptions about her husband, I tell her that this negative image of him does not arise in me. I think to myself that she is talking about a part of her inner self when she speaks about her husband.

The defense mechanisms of splitting and projection or projective identification (especially towards her husband) indicate already in this first hour an early disturbance and an “immature” processing mode. In my patient documentation there are terms like “the man as a lightning rod” (drive breakthrough/splitting), “she looks dogged” (“verbissen” in German, a reference to orality), and “feminine protest” (Oedipal conflict), which also give the first clues to her unconscious conflicts.

I ask Mrs. K. in this first encounter if she has a question about her state of suffering or an idea about what she wants or expects from psychotherapy. She looks at me helplessly and waits for my words. I feel that I should “pick her up” from her inner place and explain to her where her path might lead her. I then tell her that I experience her like a “black box” (Kara Kutu), so black (alluding to her clothes) and opaque (even to herself). The direction of the psychotherapeutic process, I tell her, could be to explore this “black box” together. Her physical as well as mental fragility gives me concern. Death has thus crept into the psychoanalytic space from the very beginning. The metaphor of the “black box” that spontaneously occurred in me, and which is searched for after an airplane crash, points to death, and the color “black” to the melancholic element, as it is also contained in the Turkish term Kara Sevda (black desire; cf. Usak, Citation2015).

In the initial hours, Mrs. K. tells about her body/physical suffering and about her “suffering at the hands of her husband.” These narrations sound very rigid and “immovable.” In her “incidental” mentions, I can hear that her husband is concerned about her and shows her affection toward which she seems to be “blind.” Two months after the beginning of the psychoanalytic process, the patient informs me that she will travel to Turkey and stay there for about three weeks. I am a bit surprised at the suddenness and decisiveness of her statement. She wants to look for the cause of her illness there and is thinking of X-ray examinations of her abdominal region. In her opinion, Turkish doctors are more familiar with the concerns and illnesses of their compatriots. Before that, however, she would like to go to a soccer game in her hometown.

To me, her concrete plan of searching for the reason of her “illness” sounds like the beginning of a journey into her own unknown, leading her to the primary place of her life (she lived in Turkey for the first eight years of her life; she frequently mentioned in the analysis that she had no memory of this time before her migration). With respect to time, there is a synchronicity to the “departure for Inner-Africa” (Nitzschke, Citation1998), to the inner unknown in the psychoanalytic process. She was not aware of this connection of the “synchronous search” at that time, but it was addressed by me at a much later phase of treatment. In particular, the fact that she wanted to attend a soccer game before the planned series of examinations caught my attention. As I learned only later on, she had been very fond of, even fanatical about, soccer in her puberty and adolescence, and was also a frequent spectator at soccer games in the stadium with her father and her little brother, especially on holidays in Turkey.

The aspect of expecting the doctors to tell her what exactly her illness is presents the evidence of her assumption that her difficulties were primarily physical in nature. In the process of further understanding, it became clear that her primary conflict around her “ego, or self-preservative, instincts” (Freud, Citation1915a, p. 124, original emphasis)Footnote8 in terms of her desire for recognition/affirmation of life was strongly condensed with food intake. From this point of view, the fixation on the physical area, especially on the stomach as the place of food intake, is understandable. I will discuss this in more detail later in the clinical vignette.

The patient looked better after her return from Turkey compared to before. The Turkish doctors had told her that her suffering was of a psychological nature. First, she underwent an X-ray, then also an ultrasound examination, and then was finally referred to a psychiatrist. He prescribed her medication and advised her to do something nice with her husband. The psychiatrist thus immediately recognized during the first and only consultation that in her case there was at least a conflict in the sexual/sensual drive area. The fact that she was referred to a psychiatrist by somatically trained doctors did not touch her very much, and she did not draw any conclusions from that concerning her problem. The important task of deciphering the clues in the sense of pointing out to her unconscious conflict and to her psychic inner world was the “hard work” that had to be done by me in the analytic process. It is important to mention that Mrs. K. brought me a present from Turkey: a package with nuts, pekmez (a Turkish sweet made of grape syrup) and helva (sweet sesame paste). The unconscious meaning of this gift remains to be seen at that point in time.

The further course of the initial phase of Mrs. K.’s psychoanalysis turned out to be very laborious. Her complaints and lamentations seemed to be tireless, the world and life were “nothing but a big lie” for her, and nothing brought any change in her life. She had no rêveries or pleasant imaginations for the future, and everything beautiful and good in life was now only a pale memory from the past. Her meager complaints on life were very difficult to bear in my countertransference.

In one of these hours I gave her an interpretation. Since the beginning of therapy her “iron nature” was noticeable; always others or the entire world was to blame for all her suffering. Her convictions could hardly be shaken, and this circumstance made me angry inwardly and at the same time helpless. My statement or my interpretation thus came directly from my affect and was correspondingly close to the patient’s unconscious. In her “iron manner,” she triggered an “iron reaction” in me that led to a turn in the analytic process. In the sense of Freud's receiver metaphor (Citation1912), from unconscious to unconscious, my interpretation set something in motion: Mrs. K. had had an argument with her husband, during which he had asked her reproachfully whether she could not see “it” (a problem), in the sense of not recognizing it, since she was stubborn and insisted on her position. I said to her:

Exactly at this point I would like to say something. You have been coming here for several months and as I know you, from the first hour, there is this “black box.” You have suffered a lot. A part of you has remained closed because of that. We have tried to open this part a little bit, we have gone into the depth of your life story together. But in the end, your expectations and complaints do not coincide with reality. If you always remain closed, there will be no miracle from the outside. The medicines, my interpretations, your husband's affectionate behavior – all this will be in vain –- that's why: Don't you see it?

In this hour and in the further course of the psychoanalysis, moving and touching hours could be followed by tender stories from her past. Sometimes she took a photo from her childhood years before migration; at other times scenes from her life in the parental home emerged. Over time, pictorial narratives also spread from her primary home in Turkey, where she had met on holidays in Turkey and fallen in love with her husband in her youth. Her stories about the first time with her husband, and the beautiful wedding photos she brought with her, reminded me of a “dream couple” from the Arabian Nights. Dreamy associations in Bion's sense (rêverie) (Citation1962) became possible with time. It seemed that the “black box” was opening a little bit.

The pre-Oedipal and Oedipal desires – the “shadow of the father” and the “silhouette of the mother”

Lacan's statement “the unconscious is the discourse of the other” (Citation1978, p. 113) (by identifying with the Other's view of oneself), sums up the dominance of the paternal partial objects/introjects in my patient's inner world. To restate this thesis in the patient's words, “Bir baklava getirecek kadar değerim yokmuş” (“I was not even worthy of being brought a baklava” – to celebrate her birth). This deeply sad sentence of Mrs. K. contains the temporal and content-related source of her basic conflict, shows the connection with her symptomatology, and gives clues to a possible diagnosis. The first thing mothers are given after giving birth in Turkish culture, is sweets such as baklava or lokum (Turkish candies) and nuts. On the one hand this is a recognition of and strengthening for the mother; on the other hand it is seen as important for a nutritious, oily milk for the child. Gifts of gold are then presented to the mother.

Mrs. K. was born as the fourth child and fourth girl of the family. Her father, who had eagerly wished for a son, was now “disappointed” for the fourth time. Thus, the mother had received no gift from him for the birth of the youngest daughter. The “silent stare,” which repeatedly appeared in Mrs. K.'s symptomatology and became present and palpable in the psychoanalytic room, can be associated with her reaction to the “absent recognition”/offense by her father. Thus, death (unconsciously: “If only you had never been born as a girl!”) is present from her birth and, moreover, has become attached to food intake, to the instinct of self-preservation.

The baklava as a physical strengthening and oral pleasure for the mother after the birth and for the abundant milk production for the baby, as well as the emotional appreciation of mother and daughter through this symbolical gift, were completely missing in Mrs. K.'s case. At the beginning of therapy, the patient's weight was 38 kilograms. With this low weight the signs of death were already manifest. In her symptoms of weight gain and loss with signs of death (an emaciated appearance), her basic conflict of worthlessness from the birth onwards can be recognized (also visually). In her stories about being thin or emaciated against the background of the described unconscious conflict dynamics, I associate a hunger strike and starvation.

I realized with the knowledge of Mrs. K.’s birth story the unconscious meaning of her gift from her trip to Turkey. I as her “mother” got from her the “birth gift”, the nuts and the sweet grape paste, so that my “milk” becomes nutritious for her: “You nourish me!” was her unconscious message. Sigmund Freud writes in “Mourning and Melancholia” that there had been “an attachment of the libido to a particular person,” but then through “a real slight or disappointment coming from this loved person, the object-relationship was shattered” (Citation1917, p. 249). Based on this thinking I formulate the thesis that the former primary disappointment of the father about his daughter now persists in the unconscious of Mrs. K., who is now an adult. In the case of melancholia, there is “an identification of the ego with the abandoned object” and “the shadow of the object fell upon the ego” (p. 249). In the case of Mrs. K. the shadow of the father specifically falls on herself. In this respect, his primary disappointment in her has also become her own disappointment in herself and her world.

In his text, Sigmund Freud (Citation1917) presupposes a once-existing relationship with the love object. In the patient's narratives there are also delicate hints of this once existing love relationship between father and daughter. For Mrs. K., this latent connection is not acceptable/perceptible, but in my countertransference it clearly appears, for example in an old photograph in which the father, crouching, looks into the face of his little daughter and smiles at her. It is important to mention in this context that the father's transference of love to the patient only took place by superimposing male characteristics on her. As loving as the father could be to his “boyish daughter,” he was strict and imperious towards his “female” daughters and his wife.

In this phase of the analytic process, Mrs. K. brought many memories and photographs with her to the sessions. I was very pleased that she was able to engage and dive into the deep layers of her soul to some extent. As Mrs. K. told me, she had dressed very boyishly in her early teenage years, preferring gendarme pants (which were fashionable among boys in the Turkish migration collective in the 1990s), plus boots and a cap. She was even somewhat jokingly called Erkek Fatma (the “man Fatma” or the “male Fatma”).Footnote9 She unconsciously complied with her father's wish for a boy by her boyish behavior and clothing, and thus gained his love and the freedoms for herself, such as that she was allowed to accompany him and also her little brother to the stadium for soccer games. At this point, the libidinous significance of her initial desire to attend a soccer match before the medical examinations in Turkey was revealed to me.

In the further course of the psychoanalysis, I learned that Mrs. K. was already very thin as a toddler and as an adolescent. The weight gain started in a conspicuous way after her marriage – with each pregnancy she had gained several kilos. The Iranian-German psychoanalyst Mahrokh Charlier describes Oedipal relationship dynamics in “patriarchal societies”Footnote10 (Citation2017, p. 50) of the Oriental cultural area and speaks of “a narcissistic symbiosis” (p. 51) “in the relationship between father and daughter”, in which there is a “mutual dependence” (p. 51). The father is dependent in his honor on the physicality of his daughter, who is not supposed to behave or clothe provocatively. She surrenders to this social control out of fear of reprisals, but also realizes that the father is dependent on her. Thus, the girl/daughter suppresses any provocative femininity to gain or retain the father's favor and recognition. In the area of tension between the father's honor and the daughter's morality – in Mrs. K.'s case, the circumstance of the “superimposed boyishness” is added – a “feeling of intimate attachment” (p. 52) arises. Accordingly, her slight figure posed no danger to her father's honor.

Exactly when Mrs. K. could inwardly distance herself from her father through love for her husband (triangulation) and live out her femininity and desire in marriage, she now “armed” herself with her kilos out of an unconscious feeling of guilt towards her father against this desire. The father had not initially agreed to the daughter's marriage.

Shortly after Mrs. K.’s second pregnancy, her desire for the original libidinal-Oedipal relationship with her father became virulent. Accordingly, this unconscious desire must have been so strong – “once again, regardless of context, obstinate, particular” as Kläui (Citation2017, p. 49) writes about unconscious desires – that she also accepted death with this difficult operation. “Ne olacaksa olsun!” (“May become what is to become!”) she had thought to herself before the operation, either to regain her slenderness or to die, without “wasting” even a thought on the possibility of leaving behind her children and her husband. My associations to this “blind” determination can be described by the terms Gözü kara/Gözü tok/Gözü pek (The eye is black/careless, the eye is satisfied/demandless, the eye is strong/fearless). Where once the love of the father was for the boyish girl, she wants to return, accepting death – the death that once should have been for the girl (“If you had never been born as a girl!”).

In the analysis we slowly approached these unconscious connections. For Mrs. K. they were completely hidden at first. The symptoms of emptiness, lack of interest, and meaninglessness, as well as the resentment towards her husband (which was basically towards her father), initially dominated her psychological state until these openings could come to light.

The mother appears marginally in the narratives compared to the father, remaining in the position of a silhouette throughout Mrs. K.'s psychoanalysis and in relation to her father. Emotionally and financially dependent on her husband (Mrs. K.'s father) and illiterate, the mother was nevertheless able to serve as a kind of “nourisher in the underground” for her children, especially her daughters, thus compensating to some extent for Mrs. K.'s “psychological malnutrition.” She had leased a field near her former house and had grown vegetables there, which she then offered for sale in part to acquaintances and neighbors and by this secretly secured her children's pocket money, without her husband noticing. From a story told by her mother, Mrs. K. learned that, as a little girl in her Turkish home village (before her migration), when many children from her clan ate together (at that time, in village areas, people ate at a sini (a large, round, silver tray)), she was not able to get all of her share of the food.

The processing of her mother's role for her own life could give Mrs. K. certain “emotional support points” in the psychoanalytic process, but she remained in the background for her daughter because of her emotional/financial dependence on her husband, or bowing to his authoritarian guidelines (identification with the aggressor). In the narratives, she appeared as a beaten, silent, suffering mother. Thus, she could not be an anchor for Mrs. K. as a child in a fundamental sense and could not represent a “enough good mother” in Winnicott's (Citation1953) understanding. Only the silhouette of the mother remained for Mrs. K. Thus, she seemed to have withdrawn her occupation from the maternal object and identified with a “dead mother” (Green, Citation2004, p. 242).

The German-Turkish psychoanalyst Aydan Özdağlar describes this Oedipal dynamic in psychosexual development in orthodox-traditional Turkish families in “Somehow Different - On Difficulties in German-Turkish Psychoanalyses” [“Irgendwie anders – Über Schwierigkeiten in deutsch-türkischen Psychoanalysen”] (Özdağlar, Citation2007). Mothers, she argues, are responsible for their daughter's so-called respectable/chaste behavior from the time of menarche (in my judgment, an abrupt feminization of the adolescent girl), thus assuming a paternal-controlling attitude and “the girl [experiences] the paternal in the mother during puberty” (p. 1110). From now on, “the mother … is perceived simultaneously as feminine-weak and as phallic-persecutory” (p. 1110). In this respect, Mrs. K.'s mother's behavior can be explained not only by her individual dependence on her husband, but also by her folk worldview, in which, from the daughter's onset of puberty, identification with paternal-controlling systems is concomitant.

Her transference love – my countertransference

The transference and countertransference events have proved to be very dense in the psychoanalytic process with Mrs. K. and very exhausting for me. As Sigmund Freud describes the manic phase in “Mourning and Melancholia,” “the whole quota of anticathexis which the painful suffering of melancholia had drawn to itself from the ego and ‘bound' will have become available” (Citation1917, p. 255). Similarly rigid as her “iron hardness” toward her husband, she is just as intense, idealizing, and appropriating in her transference towards me, fed by this “whole quota” (p. 255). I experience her unconscious desires for recognition, “being satisfied,” and symbiosis as very insistent from time to time. Inwardly I try to counteract the force of her “transference love” (Freud, Citation1915b) in a “strenuous struggle” for my abstinence/for my existence as an analyst, without losing my human/therapeutic presence. Sometimes I emphasize in due place my restraint and try to make her understand why I remain opaque as a “private person.”

Once she presented me with a gift, a three-dimensional glass frame with my photo that exists on the Internet. I experienced this as intrusive because I felt that she looked at me too much and I did not want to have a likeness of myself. Moreover, it was agreed between us that I would not accept any more gifts from her (she had prepared “food gifts” for me three times by then). I, as an incorporated part of her, was to be nourished. But this incorporation became too intense and too transgressive for me. I gave her back the photo gift and kindly and gently emphasized my position. She accepted my reaction, which at the same time she also felt like a “rejection.” From this point on, “her transference love” was withdrawn. Even though “it” then got easier in the hours of our sessions, an important part now seemed to be suppressed during this time.

My main effort in the analytic process was to direct her libido, which had become free, to her husband, who was concerned about her. I interpreted her resentment, which had been shifted from her father to her husband, and thus tried to reopen her eyes, ears, and soul to her former love for her husband and enhance the possibility for her to experience it. However, I often had the feeling that she did not hear me with my interpretations.

An “opening” dream

To my joyful surprise Mrs. K. began to tell about her dreams at some point during the psychoanalytic process. I was surprised because I considered her will to recount a dream as the result of an initial movement from within her, and I was pleased by the content of her dreams. They represented another turn for the psychoanalytic process, as they further “opened” the “black box” by seeming to reveal deep fears in her, which we began to work on and slowly understand during the hours.

In the 114th hour another “opening” (referring to the black box) dream occurred:

I am in a forest with my mother and siblings in the house of my childhood (in Austria). Suddenly I am separated from my family and am outside the house in the forest. Suddenly I catch sight of a being with a monstrous head and a childlike body. At that moment I wanted to scream out loud, but could not [“Haykırmak istedim, haykıramadım!”].

When I ask her about her associations with this dream sequence, she tells me about a real dog in the community surrounding her childhood home in Austria, of which she and her sisters were very afraid of as children. Subsequently, she comes to talk about her father when he had once beaten her mother. “Yeter!” (“Enough!”), she had been able to scream one time. Horrified, I realized: “The father, the dog!” Here, she had been able to scream really loud once, but the father had replied that she should be quiet or he would hit her too. She says sadly: “Only once I was able to scream, but I could not make my voice heard! Sesimi duyuramadım!” ().

Figure 5. Nuri İyem (1915–2005), Çıǧlık ([fearful/horrified scream], n.d. Source: Anbarpınar, Elif (2012): Türk Resminde Melankoli (1960–1980), p. 99. T.C. Cumhuriyet Üniversitesi, Eğitim Bilimleri Enstitüsü, Güzel Sanatlar Eğitimi Ana Bilim Dalı, Resim-İş Eğitimi Bilim Dalı. Yüksek Lisans Tezi. [Melancholia in Turkish Painting. Cumhuriyet University, Institute of Educational Sciences, Department of Fine Art Education, Department of Painting and Drawing Education, Master Thesis]. https://tez.yok.gov.tr/UlusalTezMerkezi/tezSorguSonucYeni.jsp

![Figure 5. Nuri İyem (1915–2005), Çıǧlık ([fearful/horrified scream], n.d. Source: Anbarpınar, Elif (2012): Türk Resminde Melankoli (1960–1980), p. 99. T.C. Cumhuriyet Üniversitesi, Eğitim Bilimleri Enstitüsü, Güzel Sanatlar Eğitimi Ana Bilim Dalı, Resim-İş Eğitimi Bilim Dalı. Yüksek Lisans Tezi. [Melancholia in Turkish Painting. Cumhuriyet University, Institute of Educational Sciences, Department of Fine Art Education, Department of Painting and Drawing Education, Master Thesis]. https://tez.yok.gov.tr/UlusalTezMerkezi/tezSorguSonucYeni.jsp](/cms/asset/6ff0dc3a-d0d9-4a11-965f-a0097872ea06/spsy_a_2303060_f0005_oc.jpg)

Through the analysis of this dream sequence we were able to approach the dynamics of her suffering. The symptomatology of “wanting to scream but not being able to,” which she had repeatedly brought up in the previous hours and which also showed up in her dreams, for the first time revealed the connection to the traumatic events to which she had been exposed as a little girl and for many more years. Now she was able to express these profound experiences of violence with clarity. Her voice was heard in her narration in the analytic space and also gets its due place in the title of this case vignette.

The fear of the real dog from her childhood was thus condensed with the fear of her childhood father, which crystallized as an association to the monstrous object with a childlike body (monstrous objects in her childhood) in the dream. Separation from her mother and siblings could indicate her feeling of deep loneliness (not a “good enough mother” in Winnicott's sense; Winnicott, Citation1953). As a little girl, she was the smallest and most delicate child among the siblings.

As difficult as the narratives were for Mrs. K., they had a curative effect in the psychoanalytic process. The analyst–patient relationship, which provided security, was also healing/“holding” (c.f. the “holding function” according to Winnicott, Citation1953). Although problems with her stomach and eating became apparent from time to time, she regained some kilos so that she came into a feminine and “healthy enough” physical and mental state. In one hour, she said she could feel, even if little, some pleasure in life. This was the most beautiful sentence in her analysis (cf. Abrevaya, Citation2023).

In a somewhat more distant hour, Mrs. K. told how her sisters had once jokingly said to her a few years ago, when she had once done a lot with a girlfriend, “Maymun açıldı” (“The monkey has risen,” in the sense of “got a taste for it”).Footnote11 “You, the monkey? Why?” I ask. She responds: “Do you know the picture? The monkey covering his mouth, eyes and ears? That monkey.”

In this hour, her associations led her to her childhood story. Painful and ashamed, she recounted how once her father had yelled and hit her mother. Unsustainable for her, she had covered her ears and eyes as a child. In the process, she said, he had then poured away the food her mother had cooked for the family and locked the kitchen door (even for the children) as punishment. When the father left the apartment, the children had ventured out of their own room and taken, as they became hungry, food from the storage room, where the raw material for cooking was. An appalling horror overcame me during her narration. I interpreted the monkey picture with her suffering. As a survival strategy Mrs. K. had – like the monkey – to cover her eyes (reminiscent of her husband’s comment: “Don't you see it?”), her ears (my thought of “She doesn't hear my interpretations”), and finally also her mouth (her own comment of “I couldn't scream/could not eat”).

As far as Mrs. K. will be able to continue to “open up” like a “monkey” in the psychoanalytic process by speaking, seeing, and hearing, her eros will be able to flare up more strongly and she could gain more quality in her life.

Conclusion

The case presentation of Mrs. K. has clarified the extent to which her pre-Oedipal and Oedipal constellations with her mother and father and the difficult conditions in a migrant environment contributed to her inner conflicts and severe health problems. In her adolescence she was only able to achieve her father's love and recognition by adopting masculine characteristics and suppressing her femininity. The unconscious realization of this paternal condition triggered the “disturbance of self-regard” (Freud, Citation1917, p. 244) from the very beginning, which constitutes the navel of melancholia. The acting out of her birth story, the immersion in the hidden childhood memories in the form of rêverie (Bion Citation1962), the “containing” (Bion, Citation1962) function of her Muslim faith, the interpretation of her fearful dreams (cf. “nameless fear”; Bion, Citation1990), and the supporting relationship with the psychoanalyst of the same cultural-religious-linguistic-gender affiliation in a migration society, enabled Mrs. K. to open up her soul and alleviate her states of suffering. One of the author's concerns is that her voice – representative of many migrant women from Muslim (migrant) cultures – be heard in the psychoanalytic scientific community.Footnote12

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Acknowledgments

The German version of this article was proofread by the DeepL program and by psychoanalyst Elke Wurnig. Thanks to her also for her comments on the “work in progress” version of this article. The translation into English was prepared by means of the DeepL program. I am grateful to psychoanalyst Dr. Doris Peham for proofreading the final English version of the text and for her remarks. Thanks also go to Assoc. Prof. Dr. Fatih Artvinli for the exchange on the term Mâl-i Hülya.

In memory of Univ. Prof. Dr. med. emeritus Günsel Koptagel-Ilal (1933–2023), the first female psychoanalyst in Turkey.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Hale Usak

Hale Usak is in private psychoanalytic practice in Innsbruck, Austria and is a lecturer at the Institute of Psychology, University of Innsbruck. She has held lectureships on the topics “Psychoanalytic treatment of Turkish-Muslim patients,” “Ethnopsychoanalysis as qualitative research method,” and “Psychoanalytic conversation” at the University of Innsbruck; “Live stories of Turkish Émigré women” at the University of Vienna; and “Introduction to psychology with emphasis on psychoanalysis” at the FH Kärnten. Her areas of interest are ethnopsychoanalytic psychotherapies in the context of the Turkish/Muslim (migration) culture, psychoanalysis in Turkey, psychoanalysis and Islam, biographical studies of emigrant psychoanalysts, and the history of psychoanalysis. ([email protected])

Notes

1 Hz. is the abbreviation for Hazreti (honored/saint). This abbreviation is prefixed in the Turkish language to the name of the Prophet, his companions (Sahabe) and other religious personalities as a sign of respect and esteem. I will place the original Turkish versions alongside the English terms that seem important to me in terms of content.

2 The saying of Allah is completed in religious communities with celle celâluhu (high/far/exalted is His glory/mercy) or also teâlâ (exalted is He). The 99 names of Allah are described in the El Esmâ-ül Hüsnâ [The most beautiful names].

3 Referring to the so-called “war neuroses” with “Schütteltremores” (tremors) and “Myotonoclonia trepidans” (convulsions).

4 The metaphor of the container is also found in the Turkish language in relation to interpersonal (unconscious) relationships: “İçimi sana dökeyim” (“I want to pour my inner self into you”) states on the manifest level the communication of an inner suffering to a person, while at the same time it also includes in its metaphore Klein's and Bion's concepts of projection, projective identification, and transformation, which Gutwinski-Jeggle (Citation2017) also uses to describe the process of depression.

5 Uyumak istiyorum. Iki yıldız arası göğe asılan hamak, uyku uyku … zamansız ve mekansız uyumak. Uyumak istiyorum; başım bir cenk meydanı; Harfsiz ve kelimesiz düşünmek Yaradanı. Ilgisizlik, herşeyden kesilmis ilgisizlik; Bilmeyiş ki, en büyük ilme denk bilgisizlik. Usandım boş yere hep gidip, gelmelerden; Bırakın uyuyayım, yandım kelimelerden! Göz kapaklarımda gün, kapkara bir kızıllık; Kulağımda tarihin cıkrık sesi, bin yıllık. Bir yurt ki bu, diriler ölü, ölüler diri; Raflarda toza batmış Peygamberden bildiri. Her gün yalnız namazdan namaza uyanayım; Bir dilim kuru ekmek, acı suya banayım! Ve tekrar uyuyayım ve kalkayım ezanla! Yaşaya dursun insan hayat dediği zanla … Necip Fazıl Kısakürek, Citationn.d. (I want to sleep. Between two stars a hammock, sleep, sleep … without time and space to sleep. I want to sleep; my head is a battlefield; without a letter and without a word I want to think the creator. Disinterestedness, disinterestedness cut off from everything; one does not know, the lack of knowledge is equal to the greatest science. I am tired of coming and going for nothing; let me sleep, I am burned by words! On my eyelids the day, pitch-black the blush; at my ear the creaking voice of history, a thousand years old. What a homeland, the living dead, the dead alive; on the book racks a dusty message from the Prophet. Every day I want to get up from prayer to prayer; a piece of hard bread, I want to dip it in a bitter water! Then sleep again and wake up to the call of the prayer! Man shall live, with the illusion, which he thinks is life) (Necip Fazıl Kısakürek, Citationn.d.).

6 I write about the melancholic phenomenon of the “The Dead Mother” in connection with Oriental and Occidental (linguistic) images in a case vignette about a child-regressive patient of Muslim faith whose mournfully absent mother was the foundation of her suffering (Usak, Citation2021).

7 The British psychoanalyst and founder of the Infant Observation Esther Bick (Citation1968) writes about the “second skin,” which babies develop when they were not “contained” enough through their mothers/primary caregivers.

8 In his earlier instinct/drive theory, Freud distinguishes between the “ego or self-preservative instincts” and the “sexual instincts” (Freud, Citation1915a, p. 124, original emphasis), but in his later instinct/drive model in “Beyond the Pleasure Principle” he opposes the “ego- (or death-) instincts” to the “sexual (life-) instincts” (Freud, Citation1920, p. 55) and uses the terms eros and thanatos for them. In a more detailed analysis of the patient's physical symptoms and conflict dynamics there seems to be a bitter struggle between eros and thanatos.

9 Fatma is a feminine given name. Erkek Fatma is a common name for girls/women who behave in a tomboyish manner; they were/are also called this way in village areas, but were/are largely integrated into the community and accepted in their way.

10 I do not see this Oedipal relational dimension, which manifests itself at the level of the “honor/morality” complex, as occurring exclusively in (sometimes overemphasized) “patriarchal” societies. It can exist in different/latent forms of societies in different expressions.

11 The expression “Maymun iştahlı” means “A person with the appetite of a monkey.” I am reminded of Freud's statement about the melancholic in manic state, who seeks “like a ravenously hungry man for new object-cathexes” (Freud, Citation1917, p. 255).

12 In order to publicize psychoanalysis in Muslim cultural context, I wrote a book on the historical and actual development of psychoanalysis in Turkey (Usak, Citation2013), which was reviewed by Marco Conci (Citation2021) in this journal. A new edition of this book with my current investigations on the topic is under consideration.

References

- Abrevaya, E. (2023). Femininity, desire and sublimation in psychoanalysis. From the melancholic to the erotic. Taylor & Francis.

- Alvan, T. (2020). Klasik Türk Şiirinde Dolab-name Hakkında Mülahazalar [The considerations about the Dolab-nama genre in classical Turkish poetry]. Türk Dili ve Edebiyatı Dergisi, 60(2), 443−476. https://doi.org/10.26650/TUDED2020-0031

- Artvinli, F. (2017). „Mecnuna ne urulur, ne sövülür!” Mazhar Osman ve yönetilemeyen bimarhaneler [“Neither beat, nor curse at the mad!” Mazhar Osman and the ungovernable bimarhane]. Osmanlı Bilimi Araştırmaları, XIX(1), 13−42.

- Bick, E. (1968). The experience of the skin in early object-relations. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 49(2), 484−486.

- Bion, W. R. (1962). Learning from experience. Karnac Books.

- Bion, W. R. (1990). Eine Theorie des Denkens [A theory of thinking]. In E. Bott Spillius (Ed.), Melanie Klein Heute. Entwicklungen in Theorie und Praxis. Beiträge zur Theorie (pp. 225−235). Verlag Internationale Psychoanalyse.

- Bulut, S., Hajiyousouf, I. I., & Nazir, Th. (2021). Depression from a different perspective. Open Journal of Depression, 10(4), 168−180. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojd.2021.104011

- Charlier, M. (2017). Ost-westliche Grenzgänge. Psychoanalytische Erkundungen kultureller und psychischer Differenzen zwischen “Orient” und “Okzident” [East-west border crossings. Psychoanalytical explorations of cultural and psychic differences between “Orient” and “Occident”]. Psychosozial-Verlag.

- Conci, M. (2021). Hale Usak-Sahin. Psychoanalysis in Turkey. A historical and personal reconstruction. International Forum of Psychoanalysis, 30(1), 71−72. https://doi.org/10.1080/0803706X.2021.1889139

- Emre, Y. (1986). Das Kummerrad/Dertli Dolap [The Cummer Wheel/Dertli Dolap]. Dağyeli Verlag.

- Faimberg, H. (2009). Teleskoping. Die intergenerationelle Weitergabe narzisstischer Bindungen [Telescoping. The intergenerational transmission of narcissistic links]. Brandes & Apsel.

- Freud, S. (1912). Recommendations to physicians practicing psycho-analysis. SE 12: 109−120.

- Freud, S. (1915a). Instincts and their vicissitudes. SE 14: 109−140.

- Freud, S. (1915b). Observations on transference-love. SE 12: 157−171.

- Freud, S. (1917). Mourning and melancholia. SE 14: 243−258.

- Freud, S. (1920). Beyond the pleasure principle. The International Psycho-Analytical Press, 1922.

- Gökay, K. F. (1939). Die Bestimmung der Leberinsuffizienz durch Santonin bei Melancholikern [The determination of liver insufficiency by santonin in melancholic patients]. Zeitschrift für die gesamte Neurologie und Psychiatrie, 165, 470−473. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02871546

- Green, A. (2004). Die tote Mutter. Psychoanalytische Studien zu Lebensnarzissmus und Todesnarzissmus [The dead mother. Psychoanalytical studies on life narcissism and death narcissism]. Psychosozial-Verlag.

- Grinberg, L., & Grinberg, R. (2016). Psychoanalyse der Migration und des Exils [Psychoanalytic perspectives on migration and exile]. Psychosozial-Verlag. (Original work published 1990)

- Gutwinski-Jeggle, J. (2017). Unsichtbares sehen - Unsagbares sagen. Unbewusste Prozesse in der psychoanalytischen Begegnung [Seeing the invisible – saying the unspeakable. Unconscious processes in the psychoanalytical encounter]. Psychosozial-Verlag.

- Güvenç, R. O. (1985). Türklerde ve Dünyada Müzikle Ruhi Tedavinin Tarihçesi ve Günümüzdeki Durumu [The history and current status of therapy with music among Turks and in the world]. Unpublished Phd thesis. Istanbul University.

- İbn Sînȃ. (2018). El Kânûn fi´t-Tıbb [The canon of medicine]. Tahbîzü'l -Mathûn (Tokadî Mustafa Efendi, Trans.). In M. Koç & E. Tanrıverdi (Eds.), El Kânûn fi´t-Tıbb. Tahbîzü'l -Mathûn. http://ekitap.yek.gov.tr/urun/el-kanûn-fi-t-tib-tercumesi_632.aspx

- Kısakürek, N. F. (n.d.). Necip Fazıl Kısakürek Şiirleri: Beklenen, Uyumak İstiyorum und Ölüm Güzel Şey [Necip Fazil Kısakürek poems: The expected, I want to sleep and death is a beautiful thing]. In: Necip Fazıl Kısakürek Şiirleri. https://www.antoloji.com/necip-fazil-kisakurek

- Kläui, Ch. (2017). Tod – Hass – Sprache. Psychoanalytisch [Death – Hate – Language. Psychoanalytical]. Turia + Kant.

- Kläui, Ch. (2018). Keine Analyse ohne Glauben. Gott, Tod und das Unbewusste [No analysis without faith. God, death and the unconscious]. texte. psychoanalyse. ästhetik. kulturkritik, 38(1), 73−89.

- Kogan, I. (1998). Der stumme Schrei der Kinder. Die zweite Generation der Holocaust-Opfer [The cry of mute children. A psychoanalytic perspective of the second generation of the Holocaust]. Fischer Verlag.

- Kristeva, J. (2007). Schwarze Sonne. Depression und Melancholie [Black sun. Depression and melancholia]. Brandes & Apsel.

- Lacan, J. (1978). Freuds technische Schriften [Freud's technical writings]. Walter Verlag.

- Lacan, J. (1981). Die Psychosen. Das Seminar, Buch III [The psychoses. The seminar, Book III]. Verlag Turia + Kant, 2021.

- Nitzschke, B. (1998). Aufbruch nach Inner-Afrika. Essays über Sigmund Freud und die Wurzeln der Psychoanalyse [Departure for inner Africa. Essays on Sigmund Freud and the roots of psychoanalysis]. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- Ogden, T. (2001). Conversations at the frontier of dreaming. Karnac Books.

- Özdağlar, A. (2007). “Irgendwie–anders” – Über Schwierigkeiten in deutsch-türkischen Psychoanalysen [“Somehow different” – About difficulties in German-Turkish psychoanalysis]. Psyche. Zeitschrift für Psychoanalyse und ihre Anwendungen. Migration. Islam. Psychoanalyse, 61(11), 1093–1115.

- Pappenheim, M. (1918). Über Kriegsneurosen bei türkischen Soldaten [About war neuroses in Turkish soldiers]. Allgemeine Zeitschrift für Psychiatrie und Psychisch-gerichtliche Medizin, 74(4–6), 310−313.

- Rohr, E., Jansen, M. M., & Adamou, J. (Eds.) (2016). Die vergessenen Kinder der Globalisierung. Psychosoziale Folgen der Migration [The forgotten children of globalization. Psychosocial consequences of migration]. Psychosozial-Verlag.

- Usak, H. (2013). Psychoanalyse in der Türkei. Eine historische und aktuelle Spurensuche [Psychoanalysis in Turkey. A historical and current search for traces]. Psychosozial-Verlag.

- Usak, H. (2015). “Kara Sevda” – “Das Schwarze Begehren” Von der Selbstlosigkeit zur Objektklebrigkeit [“Kara Sevda”-“The Black Desire”. From selflessness to object stickiness]. texte. psychoanalyse. ästhetik. kulturkritik, 35(4), 104–114.

- Usak, H. (2021). Die Frau und der Karabasan – Islamische Elemente im psychoanalytischen Raum [The woman and the Karabasan – Islamic elements in the psychoanalytic space]. texte. psychoanalyse. ästhetik. kulturkritik, 41(2), 90−105.

- Volkan, V. D. (2017). Psychoanalytic thoughts on the European refugee crisis and the Other. Psychoanalytic Review, 104(6), 661−685. https://doi.org/10.1521/prev.2017.104.6.661

- Winnicott, D. (1953). Transitional objects and transitional phenomena. The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 34(2), 89−97.