Abstract

This article aims to re-evaluate Johann Lhotsky’s published sheet music ‘A Song of the Women of the Menero Tribe near the Australian Alps’ to claim it as a distinctively Ngarigu document that speaks to Ngarigu people today. Following a method suggested by Graeme Skinner, we recover additional information, strip out the ‘improvements’ of the arrangers and create a new Ngarigu-oriented reading with what we hope will be ‘real value for song revitalisation’ by providing ‘usable details’ of text, melody and rhythm. We suggest that the evidence tends to substantiate Skinner’s suggestion that Lhotsky’s original publication was more ‘ethnographically honest’ than Isaac Nathan’s revision. We present new conclusions as to who originally performed the Song, and when and where the performance witnessed by Lhotsky took place. We show that Lhotsky’s untranslated text is clearly in an Aboriginal language and provides important clues to its significance to Ngarigu Country. We contend that various musical features of Lhotsky’s publication, while departing from the norms of settler colonial parlour music, bear witness instead to Ngarigu performance practice of the time.

Introduction

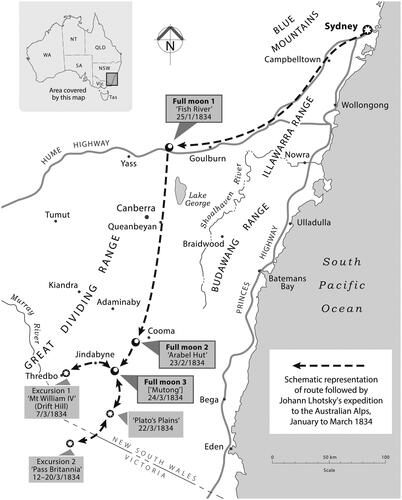

In March 1834, women of the ‘Menero tribe’ of the alpine region of south-eastern Australia performed a song witnessed by Johann Lhotsky, a Central European botanist, geologist and medical doctor with a keen interest in political economy who undertook an expedition to the area in January–March 1834 (see ). These women were most likely from the group who now identify as ‘Ngarigu’ of the Monaro district, whose homelands encompass the ‘High Country’ or ‘Snowy Mountains’ of the Australian Alps. This is Jakelin Troy’s community, referred to in this article as Ngarigu people in keeping with current usage by Aboriginal communities from the Snowy region.

Figure 1. Schematic Representation of Johann Lhotsky’s 1834 Expedition to the Australian Alps, Superimposed on a Modern Location Map. Note: Dates and names of places in boxes are drawn from his published account of the journey (Lhotsky Citation1835). Locations visited by Lhotsky on the nights of the full moons of 25 January, 23 February and 24 March are highlighted.

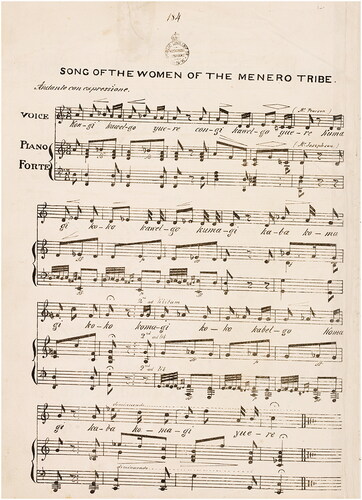

Sometime after his return to Sydney in April 1834, Lhotsky organized for his notes on the song he had heard to be arranged as a piece of parlour music for voice and pianoforte, with the assistance of three ‘musical gentlemen’,Footnote1 and in November 1834 he published the sheet music entitled ‘A Song of the Women of the Menero Tribe near the Australian Alps’ (henceforth, ‘the Song’) (Lhotsky Citation1834a). It is remarkable that this remains ‘the earliest-known piece of music, of any sort, printed in Australia’ (Skinner Citation2015, 296). While many aspects of Lhotsky’s publication betray layers of misunderstanding, misinterpretation and misrepresentation of the original performance, other features suggest that it also conserved traces of the language and music performed so long ago.

In a spirit of creative application of judgement and understanding, we present here for the first time new information about the circumstances of the Song’s production, a glossing and translation of the Ngarigu text, and a sketch of its likely musical features. To arrive at our conclusions, we have had to reimagine ourselves into Snowy Mountains Country at that time. We have read painstaking reconstructions of Lhotsky’s itinerary by historians and geographers, we have pored over topographical maps and we have drawn on our own disciplinary training as documenters of language and music. This has helped us not only to reconstruct the processes of performance and production that led to the sheet music publication, but also to propose creative re-interpretations of the Song’s content, with the purpose of incorporating it within a larger renewal of Ngarigu cultural, performative and linguistic practices.Footnote2

Significance of the Song Today

For Troy and her people, the Song is a document of immeasurable importance, bringing the voice of her ancestors into the present. For settler Australians and their descendants, study of the production and reception of the Song calls into relief the shaky foundations of settler appropriation of Indigenous lands, languages and performative cultures. For musicologists, it calls to attention the ways in which settlers have repeatedly attempted to make sense of Aboriginal performative cultures by trying to mould them into ill-fitting European musical conventions (Harris Citation2020).

Very few researchers have paid attention to the Snowy Mountains people. The exception is Josephine Flood (Citation1973, Citation1980), whose ‘Aboriginal prehistory of the Australian Alps’ provides an analysis of the archaeological record and associated ethnohistorical texts. Flood called the people of the High Country ‘The Moth Hunters’ for their practice of holding, with other local communities, great feasts of bogong moths (Agrotis infusa) from spring to early autumn each year. Moths were key to the social ceremonies and rituals of the lives of the Ngarigu and surrounding communities. Flood observed:

although the highland tribes could have feasted independently on moths within their own tribal territories, yet they gathered together for moth feasts within one tribal territory. This inter-tribal contact and shared ceremonial life would appear to have been the raison d’être of moth feasts. (Flood Citation1980, 76)

It was early autumn, the end of this bogong season, when Lhotsky came through Ngarigu Country, a time when alpine wildflowers carpeted the valleys and meadows. For Lhotsky, it was a fine time for botanizing and collecting examples of the unique alpine flora. For Ngarigu, the end of summer and the beginning of autumn is time to start thinking about bringing back the snow so that the alpine environment will continue to thrive.

For Troy, the Song speaks of a continuous shared concern for ‘caring for Country’,Footnote3 ensuring that everything human and non-human that depends on proper Indigenous management of the environment is safe and has a future. As others have suggested:

Country is often misunderstood as being synonymous with ‘land’, but it goes far beyond that. It comprises ecologies of plants, animals, water, sky, air and every aspect of the ‘natural’ environment. (Foster, Kinniburgh and Wann Country Citation2020, 68)

Troy’s people continue to remain in their Country and keep their cultural connections strong. Since the early nineteenth century, Ngarigu people have faced the ongoing challenge of settler colonial invasion and occupation and their destructive impacts on the environment of the Monaro district. The Song’s epilogue (probably penned by Lhotsky himself) asks why Troy’s people were so vulnerable in the new colonial world, an ‘unprotected race of people’ whose ‘children shrink so fastly’, reflecting what Lhotsky saw then as a declining and unsupported Aboriginal population being overrun by colonial expansion. Today, 185 years later, the Ngarigu community is spread across the Snowy Mountains region and beyond, a dispersed community like so many others. We number in the thousands, but there has never been a true census of Ngarigu people. Our communities continue to be organized into small family-oriented groups similar to those described in the historical and archaeological record (Flood Citation1980). Troy and her people must still care for Country, but it is a great challenge to know how to do so in this much altered world, where a maze of outside interests claim the right to make policy about and manage Country.Footnote4 Unpacking the Song has helped Troy to understand how her people managed Country and their engagement with climate and season.

Reception of the Song

At the time of its publication, the Song was already a contentious document, received by settler society with mixed acclaim. From the time of his arrival in Sydney in 1832, Lhotsky had begun to publish polemics attacking the British colonial government, which had also offended him by refusing to appoint him colonial zoologist at the Australian Museum. A political exile from his homeland,Footnote5 Lhotsky had come to Australia with funding from the King of Bavaria, but by the time of his 1834 journey to the Australian Alps he was largely self-financed by selling specimens collected on his travels (Anon. Citation1833; Lhotsky Citation1834b). Lhotsky’s publication of the Song, offered for sale as one of the first products of his journey, was not solely an attempt to remedy his ailing finances. It can also be read as a political act, as made clear in its epilogue: ‘Unprotected race of people/unprotected all we are/and our children shrink so fastly/unprotected why are we?’.Footnote6 This sentiment is consistent with Lhotsky’s strong views regarding the British colonial authorities’ oppression and neglect of Aboriginal people. These attitudes were expressed not only in the published record of his journey (Lhotsky Citation1835, 19), but also in an earlier polemic published anonymously in 1832, in which he condemned those who had stigmatized Aboriginal people ‘with incapacity and inferiority in the scale of human beings’, and blamed the British colonial powers for passively and apathetically allowing ‘to die away, and to become extinct, a poor and helpless race of people’ (Lhotsky Citation1832, 3). Lhotsky’s fundamentally humanist perspective placed settlers and Indigenous people (termed here ‘Papuas’) on the same plane:

Let a hundred specimens of our boasted civilization (we speak of children) be placed amidst the penury of Australian bushes, and we shall see how they will exhibit their fancied capabilities: they will suffer and shrink, like their despised fellow-creatures. … These Papuas will have, perhaps, as good Franklins and Washingtons, Byrons and Shakespeares, as the cannibals and wild fellows which the Romans called once Picts. (Lhotsky Citation1832, 3)

In a similar vein, Lhotsky’s 1834 assessment of the Song placed it alongside music considered by settler society as the height of European musical achievement: ‘for majestic and deep melancholy, it would not dishonour a Beethoven or a Handel’ (Lhotsky Citation1835, 45). Sentiments of melancholy or nostalgia were particularly associated with the parlour (or drawing-room) ballad, a popular music genre that reached its heyday in the nineteenth century, generally consisting of sheet-music arrangements for voice and pianoforte, and intended for use in amateur domestic musical settings, often performed by women (Scott Citation2017). As discussed by Scott, the ‘cultivation of refined folk airs’ including those of Britain’s own rebellious internal colonies, Scotland and Ireland, was one of the key foundations of the genre (Citation2017, 22–32). As Scott comments, ‘[t]hroughout the nineteenth century musical features from a variety of ethnic cultures were introduced from time to time as exotic decoration to drawing-room ballads’ (Citation2017, 81). Any political interpretations were mostly effaced by foregrounding a ‘melancholy nostalgia’ (Scott Citation2017, 26).Footnote7

According to Lhotsky, the ‘most competent judges’ assessed the Song as ‘very pretty’ and even ‘sublime’ (Sydney Gazette, 27 November 1834, 3). Others apparently condemned it as ‘a Portuguese air’ (insinuating, perhaps, that it was a fake, based on Lhotsky’s previous travels in Brazil in 1831–32), although Lhotsky defended it as nothing other than ‘a wild air, carrying however a great depth of feeling’ (Sydney Monitor, 27 November 1834, 3). Little evidence remains that the Song was widely circulated or performed in settler circles, despite Lhotsky’s assertion that several families had ‘expressed their wishes to buy this Air for their children’ (Sydney Monitor, 27 November 1834), and a report that ‘a considerable number’ of copies of the sheet music ‘had been lately purchased for friends in Cambridge, Edinburgh, and other eminent places in Great Britain’ (Sydney Gazette, 11 December 1834 cited in Skinner Citation2011, 115).Footnote8

We have no historical records contemporary to Lhotsky of Ngarigu people’s responses to the publication of the Song, although in the following decade Isaac Nathan reported an Aboriginal person’s response to his arrangement of another Ngarigu song, ‘Koorinda Braia’: ‘[he] alternately laughed and wept from excessive joy, at hearing his own native melody, sung and accompanied by us on our own Piano Forte’ (Nathan Citation1848, 117). Perhaps this was the same person ‘of the Maneroo tribe’ who Nathan reported having inspired his own revised arrangement of Lhotsky’s Song, published with English text by Eliza Dunlop as ‘The Aboriginal father of the Maneroo Tribe’ (Nathan Citation1843). Nathan famously poured scorn on Lhotsky’s arrangement, describing it as:

so deformed and mutilated by false rhythm, so disguised in complete masquerade, by false bases and false harmony, that I cast it from me with no small share of regret at the poor chance thus afforded me of adding anything in favour of the claim of the aborigines to the pages of musical history. (Nathan Citation1843, 2)

Twentieth-century assessments were little kinder. In Roger Covell’s opinion, the arrangement ‘removes effectively any genuine Aboriginal flavour it may have had in Lhotsky’s own memory or rough jottings’ (Covell Citation1967, 67). He continues: ‘if any trace of the original melody or melodic pattern remains, it may be in the chant-like semitonal alternations of the first phrase and its later repetition at a lower pitch’, suggesting that the complementary phrases following are ‘either partially or wholly the work of Dr Lhotsky’s Musical Gentlemen’ (Citation1967, 67). Covell concludes his discussion of the 1834 arrangement with the statement ‘The sentiments were all too accurate, even if the notation was not’ (Citation1967, 68).Footnote9

Recovering Contextual Information

Contextual information is of great significance for Ngarigu people to help identify association with Country and likely contemporary relations of the original performers. Unfortunately, none of Lhotsky’s notes relevant to the occasion of the Song have yet been located (if indeed they still survive). Who were the people who performed the song and probably helped Lhotsky document it? When and where did they perform? The sheet music itself gives few clues beyond its title. We have supplemented this sparse information by close reading of Lhotsky’s other published works (including the itinerary of his journey, published newspaper articles and journal articles), by detailed correlation of Lhotsky’s accounts of the performance context of the Song with mid-twentieth century historians’ analyses of his itinerary, and by interpreting musical features of the work in the context of other nineteenth-century settler records of performances. We have also drawn on Troy’s previous investigation of Lhotsky’s material for her PhD research (Troy Citation1994, 323–6 and 332–3).

Who

We believe it is likely that the Song was performed by members of the same group of people of the ‘Menero tribe’ who assisted Lhotsky with a brief vocabulary collected on the same trip and published some years later (Lhotsky Citation1839). We also presume that they assisted him to note down the words of the Song, which are clearly in an Australian language. Since this language would have been previously completely unknown to Lhotsky, it is unlikely that Lhotsky alone could have quickly memorized or written them down without assistance from speakers. Lhotsky’s vocabulary was collected in the course of an encounter with several young people between the ages of thirteen and nineteen (Lhotsky Citation1839, 157), part of a group of Aboriginal people that also included a man and his two wives (Lhotsky Citation1839, 158). Could these two wives have been amongst the ‘women of the Menero tribe’ referred to in the title of the Song? If the vocabulary was taught and learned by indicating things present in the environment in which it was elicited, it is telling that it includes a number of words associated with performance—song (yangang), dance (tibiribi), belt (kumel), pipe-clay (miridni, kobat), red ochre (neir) (Lhotsky Citation1839, 161), (to) paintFootnote10 (murugembeli) (Citation1839, 162) and opossumFootnote11 (buckani) (Citation1839, 159)—as well as words relating to the song content we shall shortly present: moon (kabata´) and snow (kunyima´) (Citation1839, 159).Footnote12

When

As for the likely date of the Song’s performance, some clues are provided by Lhotsky’s partial account of his journey in ‘A Journey from Sydney to the Australian Alps’ (Lhotsky Citation1835), although neither the performance of the song nor the vocabulary he collected are mentioned. Published in 1835, the ‘Journey’ finished after seven of a planned twenty instalments. The published version covers the period from 10 January to 18 February 1834, but a copy held at the British Museum contains a further nine pages of handwritten notes and two maps by Lhotsky covering the period 30 January–22 March (Jeans and Gilfillan Citation1969, 1–4). The latter part of his journey, from 23 March, is not covered at all, but a letter written from Limestone Plains (near present-day Canberra) on 5 April, during his return journey, announces the performance of the Song (Lhotsky letter to Sydney Gazette dated 5 April 1834 cited in Andrews Citation1973, 126). We can therefore presume that the dates of both Song and vocabulary were somewhere between 22 March and 5 April.

We can further narrow down this range of possible dates by reference to Lhotsky’s account of a ‘corrobery’ performance he witnessed on a ‘full moon night’ at Fish Creek on 25 January 1834 (Lhotsky Citation1835, 45). Here, Lhotsky foreshadows that he will later describe a ‘like scene witnessed near the Alps’ and give music and words for a song (Citation1835, 45). The only ‘full moon night’ between 22 March and 5 April was that of 24–25 March 1834.

Where

Lhotsky is likely to have passed the night of 24–25 March in Ngarigu Country at Mutong hut, near present-day Dalgety, which acted as the base for his two excursions into the Alps ().Footnote13 Aboriginal people were highly likely to have been living in the area. Although Lhotsky’s sketchy handwritten notes do not explicitly mention the presence of Aboriginal people at Mutong, settler colonial accounts agree that Aboriginal people were in considerable numbers in the early years of settler occupation:

The early settlers speak of the aboriginals as existing in great numbers on Manaro, though they consistently agree that at no time were they dangerous. The country, in those days, was practically owned by them, as they were the only ones who penetrated its gorges and passes. It was not unusual to see five hundred of them at the one time. (Mitchell Citation1926, 18)

A strong indication of Aboriginal presence in the Mutong area at the time of Lhotsky’s visit is the fact that both of his excursions from Mutong into the Alps followed traditional Aboriginal pathways (Wesson Citation2003, 155, Figure 30 ‘Monaro and Map pre-contact travel routes’; Blay and Eden Local Aboriginal Land Council Citation2011). On 4 March 1834, Lhotsky’s group followed a ‘Black Path’ in the course of his first excursion from Mutong to ‘Mount King William IV’ (page 6 of handwritten notes appended to British Museum copy of Lhotsky Citation1835). His second excursion southwards, in the direction of the Omeo plains, seems to have initially followed the route of a traditional pathway southward from present-day Dalgety to present-day Currowong (Wesson Citation2003, 155, Figure 30), which lies close to the Bundian Way, the most prominent of the many traditional pathways followed by coastal people journeying to and from the highlands of the Australian Alps for the annual bogong moth season (Flood Citation1973; Blay and Eden Local Aboriginal Land Council Citation2011; Blay Citation2015). It is likely that at least one of Lhotsky’s party on this second excursion was Aboriginal: Wakefield comments that ‘this is demonstrated by the direct route taken—particularly the short-cut across the mountains from Dellicknora to the Amboyne Crossing area and by the abundant use of native place names’ (Wakefield Citation1975, 243).

A variety of historical sources from just a few years after Lhotsky’s visit confirm that Aboriginal people were indeed living at Mutong. In 1841, the government administrator John Lambie distributed blankets and counted fifty-five Aboriginal people resident at ‘Snowy River’ (Lambie Citation1924), which is identified by Andrews and Wesson as Mutong (Andrews Citation1977, 95; Citation1998, 136; Wesson Citation2003, 154). In 1881, Mickey, one of the Ngarigu people who later provided information to Howitt via squatter John O’Rourke, stated that he ‘was born at Mutong, near Buckley’s Crossing [present-day Dalgety], at Rutherford’s Old PlaceFootnote14—it is his country’ (letters from John O’Rourke, 1881, held by Museum of Victoria, Howitt papers). Wesson (Citation2003, 79) estimates that Mickey was born in the period 1838–41.

The waterhole at Mutong would certainly have been of great significance to Aboriginal people living there or passing through the area on summer migrations to enjoy the Bogong moths of the Alps (Common Citation1954; Flood Citation1973). As elsewhere in Australia, careful husbandry of water and food resources by Aboriginal people in this area is widely attested (Blay and Eden Local Aboriginal Land Council Citation2011; Pascoe Citation2018). Some indication of the food resources available in this period was given by William Crisp, son of the squatter Amos Crisp, who described the abundance of the nearby Matong creek as he experienced it as a child in the late 1830s:

Matong Creek for about five miles above and below its junction with Jimenbuen Creek was a succession of deep waterholes, there being no high banks, and the grass ran to the water’s edge. Hundreds of wild ducks could be seen along these waterholes, and platypus and divers were plentiful. (Cited in Hancock Citation1972, 107)

It is therefore highly plausible that both the Song and the vocabulary originated with Aboriginal people on Ngarigu Country at Mutong, on or around the full moon night of 24–25 March 1834.

Reliability of Lhotsky’s Documentation

To evaluate the linguistic and musical features of the song document, we need to consider the circumstances that led to its production. Between Lhotsky’s witnessing of the performance and publication of the sheet music, several intervening activities must have taken place, each with potential for slippage in transmission of the cultural information. A key question concerns the reliability of Lhotsky’s notes, the pivot point between him and Ngarigu cultural practitioners. Even if assisted by Ngarigu people to note down the text and other relevant information, Lhotsky heard both performance and language with European ears. Whatever the shortcomings of his understanding and medium of documentation, however, there is evidence that Lhotsky’s European scientific training led him to approach the collection of cultural material in a similarly systematic manner to that applied in his botanical and geological work.Footnote15 Back in Sydney later in the year, the notes would have again become a pivot point as the basis for Lhotsky’s interactions with the ‘Musical Gentlemen’ called in to rearrange the song according to the conventions of British parlour music.

With regard to the reliability of his linguistic notes, Lhotsky’s own multilingualism suggests that he was likely to have been alive to phonological and other linguistic differences between languages. Born to a Czech family in the ethnically Polish city of Lwow, then part of the Austrian Empire, and educated in Prague, Berlin and Vienna, Lhotsky must have spoken several European languages (Whitley Citation1967). People for whom English is not the first language are often able to hear sounds in Australian languages that are not apparent to first-language speakers of English, particularly the phonemic vowel sounds and multiple variants of consonants, such as rhotics, that are not evident in English. Indeed, Lhotsky explicitly avoided using an English-based orthography to write Indigenous vowels, as outlined in a footnote in his 1835 Journey, as well as in his published vocabulary (Lhotsky Citation1835, 39; 1839). With regard to Lhotsky’s ability to note down musical features of the Song, his own musical training is mentioned in his article ‘Music in Australia’ published in June 1836 in his short-lived journal The Reformer, where he claims to have practiced music himself ‘in the happier days of our youth’ (cited in Anon Citation1838, 117). That he apprehended musical qualities of the Australian songs he encountered on his 1834 journey is demonstrated by his comments in relation to the performance (‘corrobery’) he witnessed at Fish River, on 25 January: ‘Their strain was in 2–4 time, which they marked by beating crotchets and in moments of greater excitement quavers’ (Lhotsky Citation1835, 45).

Language of the Song

Known to Lhotsky as members of ‘the Menero tribe’ (also spelled Maneroo), the performers of the Song were speakers of a language that has not been a community language for a very long time, although its use is now being renewed by Troy and her community. It was only sparsely documented. The most useful and voluminous primary source material currently known to researchers for the languages of the Snowy Mountains region is the documentation of George Augustus Robinson when he was Chief Protector, Port Phillip Aboriginal Protectorate, and travelled through the region in the mid nineteenth century keeping notes and documenting Aboriginal language and cultural practices (Robinson Citation2000). Other sources of primary data for the languages of the region include Lhotsky (Citation1839) (as discussed in this article), Robert Hamilton Mathews (Citation1908), and Luise Hercus and Janet Mathews (1969). Troy has drawn on her own analyses of these sources and the analyses of Harold Koch (Citation2011, Citation2016, Citation2019), as well as her own work on related New South Wales languages (Troy Citation1990, Citation1994, Citation2019). The Song’s text as given by Lhotsky has been transliterated in , assuming a three-vowel system and the consonant phoneme system proposed by Hercus and Mathews (Citation1969) and reconsidered by Koch (Citation2016, 150–1), and drawing on Troy’s own work on the sound system of and orthographic conventions for the Sydney Language, which has some features cognate with languages of the Snowy Mountains (Troy Citation2019).

Table 1. Six-phrase Text of the Song as given by Lhotsky (1834), with transliteration by Troy.

This is the first time that the Song’s text has received detailed linguistic attention. Although there are some inconsistencies in Lhotsky’s text transcription (e.g., ‘kon-gi’ versus ‘con-gi’) we can clearly discern the poetic form AABCBD. Comparison of this poetic form with that of the epilogue reveals no apparent relationship, weighing strongly against the proposition offered by some commentators that the epilogue is a translation of the Song’s text (Saintilan Citation1993, 58). Therefore, the free translation offered by Troy and presented in , based on her analysis of the text, constitutes the first translation of the song’s Ngarigu text into English. Troy’s analysis of the text features the key terms given in the vocabulary kunyimá, ‘snow’ (here, gu-) and kabatá, ‘moon’ (here, kaba). One could say that Troy has here engaged her ‘feeling for snow’ (gu-), a feeling common to people whose Country is characterized by a frozen landscape (Høeg Citation1993).

Table 2. Proposed glossing of the lyrics of the Song, by Troy.

On examining the Ngarigu lyrics, it became clear to Troy that the Song provides a substantial clue about her heritage and how her people cared for Country. It appears to be a song about snow, perhaps a snow increase song, the kind of ceremonial song Aboriginal people across Australia create to ensure that important environmental events continue. It makes sense that Ngarigu, as the people of snow and ice, would have a snow increase ceremony to ensure the continuation of this essential element in the maintenance of the alpine environment that the people depended upon and were responsible for maintaining, an essential part of ‘caring for Country’. Increase ceremonies have been widely discussed in anthropologies of Aboriginal people.Footnote16 The Song text as analysed appears to be an attempt by Ngarigu to influence the return of the snow and all that is associated with snow and its subsequent melt that sustains the alpine ecosystem. Given the time of year it was performed, it is also possible that the Song marked the end of the bogong season and was part of a ceremony to ensure the right environmental conditions for the moths to again increase in the spring. Whether frozen or melted, snow is core to the maintenance of the fragile landscape of the High Country.

By early autumn, when the Song was performed, the appearance of a frosty moon—a moon with a glowing frosty ring around it—indicates the beginning of the snow season. Ngarigu people today look for this and also for brown clouds. When Troy comments that she thinks it will snow, her mother will say ‘Yes, there are the brown clouds. It will definitely snow’. She also says that when we have a drip on our cold noses, it is snowing in the mountains. Having these and other markers of seasonal change pointed out to her is something Troy has grown up with, signs that the much awaited snow, and the fun she and her family have in their Country during the snow season, is beginning. From March onwards, the onset of winter is also signalled by the migration down into the warmer Canberra area of High Country birds like grey currawongs and magpies with large white saddles from their heads to their lower backs. Troy’s daughter, in her turn, uses these markers to understand seasonal change with reference to her Country, explaining to her friends that arrival of the birds signals the change of seasons, as do clouds and the effects of frost and icy cold on our bodies. Troy’s grandmother told her—and her mother also reinforces this essential of Ngarigu cosmology—that nothing ever disappears. The past and the present coexist: we are always living with whatever has happened before and our ancestors look down on us as stars in the sky. Troy’s mother says: ‘We stand on the ground and we touch the sky. In Ngarigu Country the sky and the earth meet on our high mountains’ (Troy Citation2017). Thus, our work engaging with this Song continues the practice of caring for snow and caring for Country, as well as creating an opportunity to repatriate this knowledge more widely to the Ngarigu community.

Ngarigu Song in Regional Context

The following description of a ‘corroboree’ from a settler colonial perspective, published in an oral history in 1926, is one of the few historical indications of performances in the Ngarigu area:

The Manaro tribes seem to have been generally in friendly association with the Canberra, Quanbeyan, Pialago men, as also with Murray and Gippsland natives. … The people from all these places often held corroborees, for which the men prepared themselves by painting and tattooing their bodies with alternate lines of white and red pigments. These gave the individual so treated a truly terrifying appearance, which was one of the objects aimed at. Women assisted at these corroborees. Whilst the men shouted and sang as they danced, the women had bundles of opossum skins rolled as tightly as possible. These they hit as hard as they could, whilst sometimes joining in the singing. (Mitchell Citation1926, 18)

This quoted passage (as well as Lhotsky’s title, ‘A Song of the Women of the Menero Tribe’) points to the key role of women in Ngarigu music, not only in singing, but also in providing rhythmic accompaniment. This description accords with widespread reports of women functioning as ‘orchestras’ at other performances witnessed by settlers in south-eastern Australia in this period, often led by an older male ‘conductor’, while women sang and beat time with a possum-skin ‘pillow’ on their laps (McDonald Citation2017, 140–71). See, for example, Eliza Kennedy’s description of Ngiyampaa singing practices (cited in Donaldson Citation1987, 27) or Wurundjeri elder William Barak’s depictions of corroboree performances (Barak Citation1895). This practice is often referred to in English as ‘beating the pillow’.

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, any kind of Indigenous song and dance was generally referred to in English as ‘corroboree’ (in various spellings, a word probably drawn from the Sydney language; see Gummow Citation2001). The ‘corroboree’ genre itself is regarded by some commentators such as Paul Carter as a European artefact:

The corroboree, like the ‘Aborigine’, was a European invention, a cultural generalization reflective of difficulties of communication in the contact situation. … the corroboree was a European construction in … that it was improvised and institutionalized in response to the white invasion. (Carter Citation1992, 168–9)

Although performances witnessed by settler colonists and called ‘corroboree’ by them were no doubt conditioned by the presence of the settler colonists themselves, there is ample evidence in early written records that performances also took place independently of settler colonist presence, often in the context of intergroup exchange (Casey Citation2013; McDonald Citation2017, 140–71).Footnote17 From the perspective of the performers themselves, and of their descendants today, performances embodied and articulated local social identities, and thus reflected great typological, thematic and musical diversity. The passage quoted at the head of this section specifically addresses the kinds of social relationships between neighbouring groups that fostered development of broader regional performance conventions. Apart from the Song itself and two Ngarigu men’s songs arranged for pianoforte by Isaac Nathan a decade later, no other detailed accounts of specifically Ngarigu music-making from this era survive. There exists, however, a useful sample from neighbouring groups.

Around 1896, the surveyor and self-taught anthropologist R.H. Mathews published an account of ceremonies held by Dhurga people (coastal neighbours of the Ngarigu), including descriptions of women’s singing, and later published texts and musical notations of some men’s and women’s songs (Mathews Citation1896, Citation1907; Mathews and Everitt Citation1900, 279–80) (reproduced and discussed in Gummow Citation1983, 245; see also Skinner and Wafer Citation2017, 403–4). In her survey of music-making in New South Wales, Gummow drew together these historical notations by R.H. Mathews with much later documentation by Janet Mathews and John Gordon of Dhurga and Dharawal songs by Herbert Chapman, Percy Davis, Jimmy Chapman and Jimmy Little Snr (Gummow Citation1983, 239–69). Although Gummow notes constraints in defining features of musical style of the area due to the limited size of the sample (Citation1983, 240), she observes that more broadly the music of New South Wales has general characteristics in common with music from the rest of Aboriginal Australia (Citation1983, 277).

Thus, useful contextual information for interpreting Lhotsky’s document can be drawn from discussions of early musical performances by other First Nations people elsewhere in south-eastern Australia including work by Gummow (Citation1983, Citation1992, Citation1994, Citation1995, Citation2001) and Donaldson (Citation1984, Citation1987, Citation1995), recently brought together and extended by McDonald (Citation2017). As observed by Gummow and others, historical records show that although south-eastern musical style was generally diverse, some common features emerge (Gummow Citation1983, 271–3; McDonald Citation2017, 156). Features relevant to this discussion (paraphrased from McDonald Citation2017) include the following:

generally descending melodic phrases, with stepwise progression within phrases and including tonal plateaux, with regular repetition of the final keynote;

larger ascending intervals (up to an octave) sometimes found between phrases;

two types of tonal organization, one where the final was the lowest note and another arranged centrically around the final note; and

predominantly syllabic rhythmic organization.

Adapting the Song to Parlour Music Conventions

The Song as published by Lhotsky lies somewhere between the known musical conventions of south-eastern Australian ‘corroboree’ music, on the one hand, and those of British parlour music on the other. The parlour music style had been imported along with pianos by early settler colonists, but most sheet music was imported, and it was only from the 1830s that locally composed sheet music began to be published in Australia (Skinner Citation2020), with the Song constituting the earliest surviving example.Footnote18 Because parlour music was destined for amateur musicians, it was generally technically straightforward, and indeed simplicity was regarded as an aesthetic ideal, allowing its usually sentimental themes to be foregrounded in its performance (Key Citation2016). Composers charged with the task of transforming the variety of musics from ethnic sources to fit into the parlour music frame adopted processes described by Scott as ‘part appropriation and part invention’ (Citation2017, 81). Commenting on how modal Scottish tunes were assimilated to the parlour style, Scott notes that ‘the first thing that could be done to “improve” matters would be to provide classical harmonies and decorate the melody with classical ornamentation’ (Citation2017, 95).

Given the lack of harmonic basis of most Australian Indigenous musics, we may conjecture that a similar process was undertaken in adaptation of the Song. Thus, not only the piano accompaniment, but also the fitting of the melody itself to the harmonic framework of the parlour music style through introduction of leading notes, passing notes, leaps within phrases and melismatic decorations, are likely, if not certain, additions by Lhotsky’s ‘Musical Gentlemen’. Other features, however, remain unidiomatic to the parlour music genre—perhaps due to Lhotsky’s insistence on including features he had noted from the original performance.

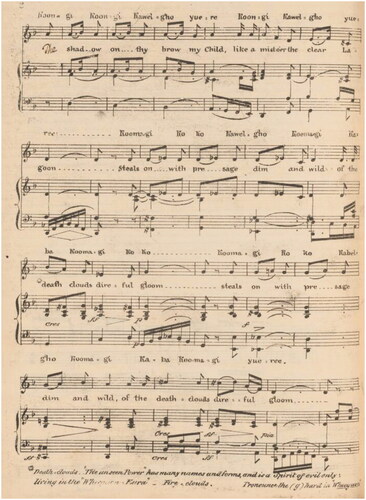

First among these anomalous characteristics is the maintenance of the text in an untranslated Aboriginal language (interpreted earlier as a variety of Ngarigu) as opposed to assimilation to parlour music conventions by providing English text.Footnote19 Instead, the melancholy sentiment characteristic of the parlour music genre is supplied by Lhotsky’s epilogue in English and German. By contrast, Nathan’s version conforms to the parlour ballad form by setting an English text in three verses by Irish-born poet Mrs Eliza Dunlop. Entitled ‘The Aboriginal Father’, this text invited the public to contemplate the despair and sorrow of an Aboriginal father whose child had been murdered.Footnote20

As previously mentioned, Lhotsky’s 1834 musical setting of the Song was heavily criticized by Isaac Nathan as ‘mutilated and deformed’ with ‘false rhythms, false bases and false harmony’. Nathan was certainly a more accomplished musician and composer than Lhotsky’s Musical Gentlemen, so his complete rewriting of the piano accompaniment doubtless produced a more orthodox specimen of parlour music. As observed by Covell, ‘Nathan’s skill allowed him to be more industrious in producing a genteel travesty of traditional chant’ (Citation1967, 68). Some of Nathan’s corrections to Lhotsky’s version, however, point to specific points of disjuncture in between the musical stylistics of ‘corroboree’ music and parlour music.

For example, Lhotsky’s version () generally maintains syllabic rhythm (characteristic of ‘corroboree’ style), resulting in the shorter seven-syllable or eight-syllable lines (A, C and D) being set to three-bar phrases, while the longer 11-syllable line B is set to a four-bar phrase. As can be seen from , in revising Lhotsky’s version, Nathan converted all Lhotsky’s three-bar phrases to four-bar phrases, either by interpolating an additional bar of repeated melodic material (first system, bar 3) or by extending the phrase-final note (system 2, bars 1–2; system 3, bars 3–4; system 4, bars 5–6). This irregular phrasing in the Lhotsky version is perhaps what Nathan meant by ‘false rhythms’, because apart from some minor alterations to dotted rhythms, he otherwise largely maintained Lhotsky’s rhythmic setting of the vocal line.

Figure 2. Lhotsky’s 1834 Setting of the Song (Lhotsky Citation1834a, 2). Note: Courtesy of State Library of New South Wales.

Figure 3. Isaac Nathan’s Rearrangement of Lhotsky’s Original: ‘The Aboriginal Father’, with English Text by Eliza Dunlop (Nathan Citation1843, 3). Note: Courtesy of State Library of New South Wales.

Another striking feature of the Lhotsky setting of the Song is its unusual harmonic structure, setting the six lines of text in three sections, modulating D minor–G minor–C minor. Various commentators including Skinner (Citation2017) and Covell (Citation1967) have commented on this feature. Covell considers this feature to be an innovation of the Musical Gentlemen ‘with a certain air of self-conscious unorthodoxy’ (Citation1967, 67). Skinner comments that Lhotsky’s version ‘defies European rules of tonality so as to end in a different key from which it began. Perhaps Lhotsky had perfect pitch, and this is what he heard’ (Skinner Citation2011, 115). Nathan ‘corrected’ this feature by altering cadences and rearranging the melody of the last line to return to D minor rather than C minor.

In the context of the characteristics of south-eastern Australian ‘corroboree’ style listed earlier, it is noteworthy that Lhotsky’s version of the last phrase, finishing on C, displays the centric tonal organization identified by Gummow as characteristic of south-eastern Australian musical style,Footnote21 while Nathan’s version alters the melody to finish with the phrase-final on the lowest note of the melody. While this ‘correction’ of Nathan’s no doubt sought to address ‘false harmony’, in all probability it erased a key feature of the original Song. Sequential transpositions of melodies by a tone or a third are mentioned by George W. Torrance, a nineteenth-century commentator on the music of Yorta composer William Barak (Torrance Citation1887; discussed by McDonald Citation2017, 157). In light of these observations, it is not implausible that the melody of the Song witnessed by Lhotsky might have been similarly transposed.

In parlour music style, piano accompaniment often remains closely aligned to the vocal line, reinforcing the pitch of the amateur singer and not infrequently showing musical independence only in the pauses between lines or verses (Scott Citation2017, 29). This feature can be observed in Nathan’s setting. By contrast, the texture of the piano accompaniment in Lhotsky’s version involves frequent octaves in the left hand, often marking the vocal rhythm. However ‘false’ these bases may have been when read from the perspective of the conventional harmonic framework of the parlour song, they can also be read as invoking the Menero women’s ‘beating of the pillow’ to accompany their Song.

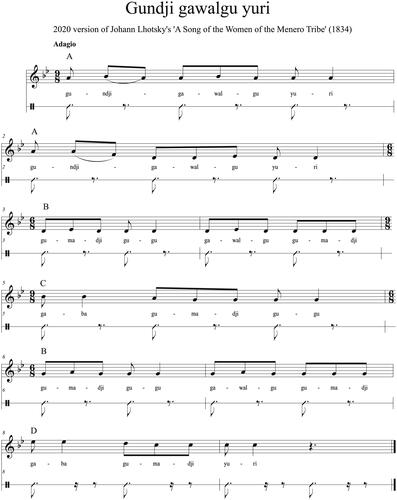

Resetting the Song for Contemporary Ngarigu Performance

In 2017 Graeme Skinner proposed that:

[insofar] as some usable details of melody and rhythm can be recovered, or reconstituted hypothetically, by stripping out their ‘improvements,’ even the most unpromising cases of colonial arrangements––like Nathan’s, Salvado’s and Taplin’s–– potentially retain real value for song revitalisation. (Skinner Citation2017, 356)

We have developed a sketch setting of the Song that discards features we consider to have been introduced to fit parlour music conventions, with some additional reworking inspired by stylistic features of the group of Dhurga women’s songs from the south coast of New South Wales notated by Mathews around 1901 (Mathews Citation1907, 35).

To produce our sketch (), based on Lhotsky’s 1834 version of the Song (rather than Nathan’s later revisions), we have removed the piano accompaniment and stripped the vocal melody of what we consider to be harmonic alterations (such as insertion of leading notes) and unidiomatic leaps within musical phrases, otherwise largely maintaining Lhotsky’s pitch contour. We have kept the uneven phrase structure, which we have organized in a compound triple metre (reflecting the 6/8 time signature of the three women’s songs notated by Mathews) and inserted regular percussion (to reflect the women’s beating). We have also realigned musical stress to fit the text stress (which occurs on the first syllable of most words, as in Mathews [Citation1907] and many other sources, rather than on the last syllable, as in Lhotsky’s published score).

Conclusion

By claiming Lhotsky’s 1834 sheet music publication as a record of Ngarigu creative practice, stemming from the heart of Ngarigu Country, our primary aim is to care for Ngarigu performative culture, honour Ngarigu Country and nurture contemporary Ngarigu creativity. Our hope is that our work may inspire new creations and new performances by Ngarigu people on Country, and thus contribute to the great ongoing dialogue between people and Country. As Troy commented in 2016, ‘We will never be truly “colonised” while ever we keep these songlines open and we can rehearse the knowledge of our peoples and our Countries that these songs repeat across thousands of generations’ (Troy Citation2016). At the time of completing final revisions to this article, we are undertaking a series of performance events to allow Ngarigu people to learn and perform the Song on and for Country, with the support and collaboration of allies from other First Nations groups and musical experts.

We also hope that this account of our research process will help others to take stock of their own musical heritage, including understanding the double-edged role of song documentation and adaptation in histories of advocacy for First Nations people as well as erasure of First Nations musical agency. As co-authors, we share a commitment to social justice and to contemporary efforts to re-evaluate and, where appropriate, revitalize significant cultural records. We have struggled to forge this new story of the Song. We are both children of the intellectual and social histories addressed in this article.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Nicholas Routley, Allan Marett and Amanda Harris for feedback on earlier versions of this article. Thank you, too, to participants in the Australian Research Council-funded Discovery Project DP180100938 ‘Reclaiming Performance Under Assimilation’, in particular those who attended the workshop held on Ngarigu Country at Thredbo in May 2019.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jakelin Troy

Jakelin Troy is Director, Indigenous Research at the University of Sydney. She is known as one of the early founders, in Australia, of the field of language reconstruction from historical records. Specializing in the languages of New South Wales, her work began with an analysis of communication between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people in the post invasion ‘colonial’ period on the east coast of Australia (Troy Citation1985, Citation1990, Citation1994). Her 1993 publication The Sydney Language (second edition 2019) brought together and analysed historical documents on the languages spoken in the Sydney area, including the Patyegarang and Dawes notebooks compiled circa 1791. A Ngarigu woman whose Country lies in the Snowy Mountains region of New South Wales, she is responsible for the linguistic analysis in this article.

Linda Barwick

Linda Barwick is an Emeritus Professor in the Sydney Conservatorium of Music at the University of Sydney. She is a musicologist specializing in Australian music, with a focus on repatriation and revitalization of archival materials. Her convict settler ancestors were part of the colonial-era erasure of First Nations sovereignty in New South Wales. She is responsible for the music analysis in this article. She is a Fellow of the Australian Academy of the Humanities.

Notes

1 As explicitly noted in the published score, Mr Pearson was credited with the vocal arrangement, Mr Josephson with the piano arrangement, and Mr Sippe with the simplified piano arrangement (Lhotsky Citation1834a).

2 Ours is far from the first scholarly engagement with the Song (Hall Citation1951; Covell Citation1967, 67–68; Hort Citation1987; Saintilan Citation1993, 56–59; Troy Citation1994; Skinner Citation2011, Citation2014; Skinner and Wafer Citation2017, 372–73).

3 Country is capitalized when writing about an Aboriginal homeland, as dictated by Aboriginal protocol. ‘On Country’ is the way Aboriginal people describe the embodied experience of being immersed in the environment of their homelands.

4 This leads to what Tess Lea calls ‘wild policy’ and a chaos of management that exhausts individuals and communities (Lea Citation2020).

5 Born in Lemberg (Galicia), the son of a Czech-born Austrian government official, Lhotsky was imprisoned for political activities by the Austrian empire for several years in the 1820s (Paszkowski Citation1977). Following his collecting expeditions in Brazil and Australia, he returned to Europe and continued to live in exile in London, where he died in around 1866.

6 A more or less direct translation into German follows: one of Lhotsky’s own languages, and that of some of his closest European colleagues and funders. Oddities in the English (lack of rhyme in lines 2 and 4; use of ‘fastly’) may suggest that the original verse was in fact first written in German and then translated into English, pointing to Lhotsky himself as the likely author. Covell (Citation1967, 68) suggests (on unknown grounds) that Mr Sippe may have been responsible for the verse epilogue. As discussed more fully in the following, the epilogue is not a translation of the Song lyrics, as some commentators have assumed.

7 Later in the century, blackface minstrelsy became a key component of the parlour ballad genre.

8 See Graeme Skinner’s (Citation2011, 112–15) PhD thesis for further details on settler reception of the Song.

9 Ann Carr-Boyd’s (Citation1971) instrumental arrangement of the Song for trio of flute, cello and piano (Carr-Boyd Citation1971) remains one of the few known traces left by the Song in more recent Australian performance history.

10 The verb ‘to paint’ (or ‘to paint up’) refers to the application of ceremonial paint to the body of the dancers (and sometimes singers), which features widely in ‘corroboree’ performances across Australia.

11 As will be discussed later in this article, women used tightly bound bundles of possum skin to beat time for corroboree songs (Mitchell Citation1926, 18).

12 The vocabulary does not include, however, the Ngarigu word for ‘corroboree’, which according to Robinson was Woc.kite (Koch ‘wagady’), ‘corrobery’ (Robinson Citation2000, 193).

13 On 22 March, Lhotsky was heading back to Plato’s Plains hut (near present-day Currowong), a day’s journey from his base at Mutong. Described by Lhotsky as ‘the last out-station in that direction of the alps’, Mutong’s nearby waterhole supported a variety of European vegetables (described in Lhotsky Citation1835, 104).

14 Around the 1860s–70s, William Rutherford was a squatter at Marinumbla (also spelled ‘Marranumbla’) station, described as ‘near Buckley’s Crossing’, present-day Dalgety.

15 Alan Andrews comments in relation to Lhotsky’s notes on his travels that ‘they give the decided impression that he had recorded the excursion with complete honesty and has recorded features and impressions to the best of his ability’ (Andrews Citation1973, 114).

16 Morton contends that ‘an analysis of the symbolism of “increase rite” has to be integrated with an analysis of its general effect, not only on the moral subjectivity and social constitution of believers, but also on the natural phenomena which the rites are said to influence’ (Citation1987, 455).

17 See also the extensive list of newspaper reports of Indigenous performances in early colonial times on Graeme Skinner’s Australharmony website (Skinner Citation2014, Citation2020).

18 According to Skinner (Citation2020), the lithographer was John Austin Gardner, who had arrived in Sydney in June 1834.

19 Casey suggests that from an Indigenous perspective, ‘performances in Aboriginal languages without explanation can be understood as an offer of knowledge to the settlers that required them to actively engage with learning in order to understand. This is an offer that the majority of settlers failed or chose not to take up. Given the violence against Aboriginal people and the need to negotiate safety and access to their traditional lands and hunting grounds, this maintenance of cultural power and generosity is remarkable’ (Citation2013, 63).

20 While consistent with the sentimental connotations of the parlour music style, Dunlop’s evocation of horror and melancholy was linked to her political campaigns against massacres of Aboriginal people, notably the Myall Creek massacre of 1838, for which she had written her most famous poem entitled ‘The Aboriginal Mother’ (Hansord Citation2011).

21 Centric tonal organization is also found in the second section of the melody, which finishes on G in both Lhotsky and Nathan’s versions.

References

- Andrews, A.E.J. (1973), ‘Further Light on the Summit: Mount William IV Not Kosciusko’. Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society 59/2: 114–27.

- Andrews, A.E.J. (1977), ‘Dr John Lhotsky’s Australian Alps and Menero’, in Vladislav Kruta (ed.), Dr. John Lhotsky: The Turbulent Australian Writer, Naturalist and Explorer. Melbourne: Australia Felix Literary Society, 87–108.

- Andrews, A.E.J. (1998), Earliest Monaro and Burragorang, 1790 to 1840: With Wilson, Bass, Barrallier, Caley, Lhotsky, Jauncey, Lambie, Ryrie. Palmerston, ACT: Tabletop Press.

- Anon. (1833), ‘Advance Australia’, The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW: 1803–1842), November 21, 31.

- Anon. (1838), ‘Music at Sydney’, in Chambers’ Edinburgh Journal, Eds William and Robert Chambers (Saturday, May 6, 1837), 6/275: 5. London: W.S. Orr & Co, 117. Digitized from the University of California at Los Angeles Library Copy by Google, 23 April 2012.

- Barak, William (1895), ‘Corroboree, 1895’. Drawing in charcoal and natural earth pigments, over black pencil. National Gallery of Australia, Accession Number NGA2009.164 (Accessed 12 April 2021), https://artsearch.nga.gov.au/detail.cfm?IRN=193404.

- Blay, John (2015), On Track: Searching out the Bundian Way. Sydney: NewSouth Books.

- Blay, John, and Eden Local Aboriginal Land Council (2011), Report on a Survey of the Bundian Way, 2010–2011. Eden, Australia: Eden Local Aboriginal Land Council.

- Carr-Boyd, Ann (1971), Song of the Women of the Menero Tribe (Trios: Flute, Piano, Cello). Music score. Sydney. Australian Music Centre.

- Carter, Paul (1992), Living in a New Country: History, Travelling and Language. London: Faber & Faber.

- Casey, Maryrose (2013), ‘Colonists, Settlers and Aboriginal Australian War Cries: Cultural Performance and Economic Exchange’. Performance Research 18/2: 56–66..

- Common, I.F.B (1954), ‘A Study of the Ecology of the Adult Bogong Moth, Agrotis Infusa (Boisd) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), with Special Reference to Its Behaviour during Migration and Aestivation’. Australian Journal of Zoology 2/2: 223–63..

- Covell, Roger (1967), Australia‘s Music: Themes of a New Society. Melbourne: Sun Books.

- Donaldson, Tamsin (1984), ‘Kids That Got Lost: Variation in the Words of Ngiyampaa Songs‘, in Jamie C. Kassler and Jill Stubington (eds.), Problems and Solutions: Occasional Essays in Musicology Presented to Alice M. Moyle. Sydney: Hale & Iremonger, 228–53.

- Donaldson, Tamsin (1987), ‘Making a Song (and Dance) in Southeastern Australia’, in Margaret Clunies Ross, Tamsin Donaldson, and Stephen A. Wild (eds.), Songs of Aboriginal Australia. Oceania Monograph 32. Sydney: Oceania Publications, University of Sydney, 14–42.

- Donaldson, Tamsin (1995), ‘Mixes of English and Ancestral Language Words in Southeast Australian Aboriginal Songs of Traditional and Introduced Origin‘, in Linda Barwick, Allan Marett, and Guy Tunstill (eds.), The Essence of Singing and the Substance of Song: Recent Responses to the Aboriginal Performing Arts and Other Essays in Honour of Catherine Ellis. Oceania Monograph 46. Sydney: Oceania Publications, University of Sydney, 143–58.

- Flood, Josephine (1973), ‘The Moth-Hunters : Investigations Towards a Prehistory of the South-Eastern Highlands of Australia’. PhD thesis, Australian National University.

- Flood, Josephine (1980), The Moth-Hunters: Aboriginal Prehistory of the Australian Alps. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies.

- Foster, Shannon, Kinniburgh, Joanne Paterson, and Wann Country (2020), ‘There’s No Place Like (Without) Country’, in Dominique Hes and Cristina Hernandez-Santin (eds.), Fundamentals for the Built Environment. Singapore: Palgrave-Macmillan, 63–82.

- Gummow, Margaret (1983), ‘Aboriginal Music of New South Wales: An Exploratory Study’. BA (Hons) thesis, The University of New England.

- Gummow, Margaret (1992), ‘Aboriginal Songs from the Bundjalung and Gidabal Areas of South-Eastern Australia’. PhD thesis, The University of Sydney. http://hdl.handle.net/2123/7249.

- Gummow, Margaret (1994), ‘The Power of the Past in the Present: Singers and Songs from Northern New South Wales’. The World of Music 36/1: 42–50.

- Gummow, Margaret (1995), ‘Songs and Sites/Moving Mountains: A Study of One Song from Northern NSW’, in Linda Barwick, Allan Marett, and Guy Tunstill (eds.), The Essence of Singing and the Substance of Song: Recent Responses to the Aboriginal Performing Arts and Other Essays for Catherine Ellis. Oceania Monograph 46. Sydney: Oceania Publications, University of Sydney, 106–20.

- Gummow, Margaret (2001), ‘Australia: I. Aboriginal Music: 3. Southeastern Aboriginal Music’, in Stanley Sadie and John Tyrell (eds.), Grove Music Online. Oxford: Oxford Music Online.

- Hall, James (1951), ‘A History of Music in Australia, No. 6’. The Canon: Australian Journal of Music 4/11: 517–24.

- Hancock, W. Keith (1972), Discovering Monaro: A Study of Man’s Impact on His Environment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hansord, Katie (2011), ‘Eliza Hamilton Dunlop’s “The Aboriginal Mother”: Romanticism, Anti Slavery and Imperial Feminism in the Nineteenth Century’. Journal of the Association for the Study of Australian Literature 11/1: 1–14.

- Harris, Amanda (2020), ‘Representing Australia to the Commonwealth in 1965: Aborigiana and Indigenous Performance’. Twentieth-Century Music 17/1: 3–22.

- Hercus, Luise, and Janet Mathews (1969), ‘Phonetic Notes on Other Victorian Languages: Southern ŋarigu’, in Luise Hercus (ed.), The Languages of Victoria: A Late Survey. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, 198–210.

- Høeg, Peter (1993), Miss Smilla’s Feeling for Snow. Translated by F. David. London: The Harvill Press.

- Hort, Harold (1987), ‘An Aspect of Interaction Between Aboriginal and Western Music in the Songs of Isaac Nathan’. Miscellanea Musicologica: Adelaide Studies in Musicology 12: 207–11.

- Jeans, Dennis. N., and William G.R. Gilfillan (1969), ‘Light on the Summit: Mount William the Fourth or Kosciusko?’ Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society 55/1: 1–18.

- Key, Susan (2016). ‘Parlor music’, in Anna-Lise Santella (ed.), Oxford Music Online (Grove Music Online). New York: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.A2292670.

- Koch, Harold (2011), ‘George Augustus Robinson and the Documentation of Languages of South-Eastern New South Wales’. Language & History 54/2: 140–63.

- Koch, Harold (2016), ‘Documentary Sources on the Ngarigu Language: The Value of a Single Recording‘, in Peter K. Austin, Harold Koch, and Jane Simpson (eds.), Language, Land and Song: Studies in Honour of Luise Hercus. London: EL publishing, 145–57. http://www.elpublishing.org/PID/2011.

- Koch, Harold (2019), ‘Yuin Comparative Vocabulary by Semantic Domain’. Unpublished Text, Version 08.07.2019.

- Lambie, John (1924), ‘Report by J. Lambie Re Aborigines in District of Maneroo 14 January, 1842’, in Frederick Watson (ed.), Historical Records of Australia. Published Online by the National Library of Australia, Series One, 21 October 1840–March 1842. Sydney: Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament, 743–44. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-442186184.

- Lea, Tess (2020). Wild Policy: Indigeneity and the Unruly Logics of Intervention. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Lhotsky, John (1832), ‘Australian Sketches. 1. Civilization of the Aborigines’. The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW: 1803–1842), 6 October 1832, 3.

- Lhotsky, John (1834a), A Song of the Women of the Menero Tribe near the Australian Alps. Arranged with the Assistance of Several Musical Gentlemen for the Voice and Pianoforte, Most Humbly Inscribed as the First Specimen of Australian Music to Her Most Gracious Majesty Adelaide, Queen of Great Britain and Hanover, by Dr J. Lhotsky, Colonist N.S. Wales. Sydney: Sold by John Innes, Pitt Street. By commission at R. Ackerman’s Repository of Arts, Strand [London].

- Lhotsky, John (1834b), ‘Australian Philosophical Repository’. The Sydney Monitor (NSW: 1828–1838), 27 November 1834, Morning edition, sec. Advertising.

- Lhotsky, John (1835), A Journey from Sydney to the Australian Alps, Undertaken in the Months of January, February, and March, 1834. Being an Account of the Geographical & Natural Relation of the Country Traversed, Its Aborigines, Etc. [Pp. 118, With a Map and with MS. Material Inserted.]. Sydney: [by commission at R Ackermann’s Depository, London. Digitized original from British Library, digitized by Google Books 18 October 2018].

- Lhotsky, John (1839), ‘Some Remarks on a Short Vocabulary of the Natives of Van Diemen Land, and Also of the Menero Downs in Australia’. Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London 9: 157–62.

- Mathews, Robert H. (1896), ‘The Bunan Ceremony of New South Wales’. The American Anthropologist 9/10: 327–44.

- Mathews, Robert H. (1907), Notes on the Aborigines of New South Wales. Sydney: Government Printer. (Accessed 17 September 2020), http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-756755978.

- Mathews, Robert H. (1908), ‘Vocabulary of the Ngarrugu Tribe, N.S.W’. Journal of the Royal Society of New South Wales 42: 335–42.

- Mathews, Robert H., and Mary M. Everitt (1900), ‘The Organization, Language and Initiation Ceremonies of the Aborigines of the South-East Coast of New South Wales’. Royal Society of New South Wales Journals and Proceedings 34: 262–81.

- McDonald, Barry (2017), ‘A Survey of Traditional South-Eastern Australian Indigenous Music‘, in Jim Wafer and Myfany Turpin (eds.), Recirculating Songs: Revitalising the Singing Practices of Indigenous Australia. Canberra and Newcastle: Pacific Linguistics & Hunter Press, 360–404.

- Mitchell, Felix F., ed., (1926). Back to Cooma Celebrations; 20th February to 27th February 1926 [Booklet]. Cooma: The Direct Publicity Company under the auspices of the ‘Back to Cooma’ Executive Committee.

- Morton, John (1987), ‘The Effectiveness of Totemism: “Increase Ritual” and Resource Control in Central Australia’. Man 22/3: 453–74.

- Nathan, Isaac (1843), The Aboriginal Father, a Native Song of the Maneroo Tribe … the Melody, as Sung by the Aborigines, Put into Rhythm & Harmonized with Appropriate Symphonies & Accompaniments … by I. Nathan. Sydney: T. Bluett, Lithographer. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-165998456.

- Nathan, Isaac (1848), The Southern Euphrosyne, and Australian Miscellany: Containing Oriental Moral Tales, Original Anecdote, Poetry and Music. Sydney: Isaac Nathan. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-166023361.

- Pascoe, Bruce (2018), Dark Emu. Revised edition. Broome: Magabala Books.

- Paszkowski, Lech (1977), ‘John Lhotsky as I See Him‘, in Vladislav Kruta (ed.), Dr. John Lhotsky: The Turbulent Australian Writer, Naturalist and Explorer. Melbourne: Australia Felix Literary Society, 109–35.

- Robinson, George Augustus (2000), The Papers of George Augustus Robinson, Chief Protector, Port Phillip Aboriginal Protectorate ed. Ian D. Clark. Ballarat, Vic: Heritage Matters.

- Saintilan, Nicole (1993), ‘“Music—If so It May Be Called”: Perception and Response in the Documentation of Aboriginal Music in Nineteenth Century Australia’. Master of Music thesis, University of New South Wales. http://handle.unsw.edu.au/1959.4/50383.

- Scott, Derek B. (2017), The Singing Bourgeois: Songs of the Victorian Drawing Room and Parlour. 2nd edition. London: Routledge.

- Skinner, Graeme (2011), ‘Toward a General History of Australian Musical Composition: First National Music 1788–c.1860’. PhD thesis, The University of Sydney.

- Skinner, Graeme (2014). Australharmony: An Online Resource toward the History of Music in Colonial and Early Federation Australia. Sydney: University of Sydney. (Accessed 17 September 2020), https://www.sydney.edu.au/paradisec/australharmony/

- Skinner, Graeme (2015), ‘The Invention of Australian Music’. Musicology Australia 37/0: 289–306.

- Skinner, Graeme (2017), ‘Recovering Musical Data from Colonial Era Transcriptions of Indigenous Songs: Some Practical Considerations‘, in Jim Wafer and Myfany Turpin (eds.), Recirculating Songs: Revitalising the Singing Practices of Indigenous Australia. Canberra & Newcastle: Pacific Linguistics & Hunter Press, 349–74.

- Skinner, Graeme (2020), ‘A Checklist of Australian Sheet Music Prints, 1834–c.1850’. Australharmony (an Online Resource toward the History of Music and Musicians in Colonial and Early Federation Australia). (Accessed 17 September 2020), https://sydney.edu.au/paradisec/australharmony/checklist-sheet-music-1834-c1850.php

- Skinner, Graeme, and Jim Wafer (2017), ‘A Checklist of Colonial Era Musical Transcriptions of Australian Indigenous Songs’, in Jim Wafer and Myfany Turpin (eds.), Recirculating Songs: Revitalising the Singing Practices of Indigenous Australia. Canberra & Newcastle: Pacific Linguistics & Hunter Press, 360–404.

- Torrance, G.W. (1887), ‘Music of the Australian Aboriginals. [An Appendix to Mr A.W. Howitt’s “Notes on Songs and Songmakers of Some Australian Tribes”]’. The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 16: 335–40.

- Troy, Jakelin (1985), ‘Australian Aboriginal Contact with the English Language in New South Wales: 1788 to 1845’. BA (Hons) thesis, The University of Sydney.

- Troy, Jakelin (1990), Australian Aboriginal Contact with the English Language in New South Wales: 1788 to 1845. Pacific Linguistics, Series B-103. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

- Troy, Jakelin (1994), ‘Melaleuka: A History and Description of New South Wales Pidgin’. PhD thesis, Australian National University.

- Troy, Jakelin (2016), ‘Songlines of My Country: Belonging to Land Is a Universal Right That Shouldn’t Be Denied’. SBS News Online. NITV: The Point (blog). July 5, 2016. (Accessed 21 March 2021), https://www.sbs.com.au/nitv/article/2016/07/05/songlines-my-country-belonging-land-universal-right-shouldnt-be-denied

- Troy, Jakelin (2017), ‘Standing on the Ground and Writing on the Sky: An Emotional Account of Being Indigenous’. Public lecture for the Autralian Research Council Centre of Excellence for the History of Emotions, The University of Western Australia, December 12 2017.

- Troy, Jakelin (2019), The Sydney Language. 2nd edition. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press.

- Wakefield, Norman A (1975), ‘Dr. John Lhotsky’s Two Excursions into the Australian Alps’. The Victorian Naturalist 92: 228–43.

- Wesson, Sue Caroline (2003), ‘The Aborigines of Eastern Victoria and Far Southeastern New South Wales, 1830 to 1910: An Historical Geography’. PhD thesis, Monash University.

- Whitley, Gilbert P. (1967), ‘Lhotsky, John (1795–1866)’, in Douglas Pike (ed.), Australian Dictionary of Biography, volume 2. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 114–15. http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/lhotsky-john-2357/text3085.