Abstract

Social media networks such as Facebook offer a promising way of fast, cost-effective and direct communication between enterprises and stakeholders. Employing this technology in entrepreneurial Public Relations (PR) may increase the success of new ventures. Yet, the adoption of social media for PR by start-ups remains under-studied. To fill this gap, we conceptualize entrepreneurial PR within the framework of communication management theory and entrepreneurial marketing. We developed three success factors for PR communication out of the literature and tested them empirically using a sample of 453 German start-ups. Results indicate that social media PR positively contributes to communication outcomes in terms of building up brand and reputation. Perceived relevance, long-term planning and understanding-oriented PR were all relevant for communication success. This means that entrepreneurs benefit from social media, when they initiate dialogues with stakeholders, conduct environmental scanning processes, and build up PR planning skills. Moreover, findings indicate that social media PR is practiced differently depending on the start-ups’ age. Hence, it is crucial for future research to integrate a dynamic perspective on entrepreneurial PR studies.

Résumé

Les réseaux de médias sociaux tels que Facebook offrent un moyen prometteur de communication rapide, économique et directe entre les entreprises et les parties prenantes. Le recours à cette technologie dans les relations publiques (RP) peut accroître le succès de nouvelles entreprises. Pourtant l’adoption des médias sociaux aux fins de relations publiques par les start-ups reste peu étudiée. Pour combler cette lacune, nous conceptualisons les relations publiques entrepreneuriales dans le cadre de la théorie de la gestion de la communication et du marketing entrepreneurial. Nous avons développé trois facteurs de succès pour la communication dans les RP à partir de la littérature et les avons testés en utilisant empiriquement un échantillon de 453 start-ups allemandes. Les résultats indiquent que les relations publiques dans les médias sociaux contribuent positivement aux résultats de la communication en ce qui concerne le renforcement de la marque et de la réputation. La pertinence perçue, la planification à long terme et les relations publiques axées sur la compréhension sont autant d’éléments qui ont contribué au succès de la communication. Cela signifie que les entrepreneurs bénéficient des médias sociaux lorsqu’ils entament des dialogues avec les parties prenantes, mènent des processus d’analyse de l’environnement et développent des compétences en matière de planification des relations publiques. En outre, les résultats indiquent que les relations publiques dans les médias sociaux sont pratiquées différemment selon l’âge des start-ups. Il est donc crucial que les recherches futures intègrent une perspective dynamique sur les études de relations publiques entrepreneuriales.

1. Introduction

Since around the turn of the millennium, start-up companies have played an increasingly important role in public debate, but also in specialist discourses in politics, business and science. In this context, reference is often made to positive employment effects of start-up activity, but also to the role of start-ups as drivers of competition and innovation (Van Stel, Carree, and Thurik Citation2005). From both theoretical reflections and best cases from business practice, it can be proposed that public relations (PR) may play a significant role for a start-up’s success (Bekmeier-Feuerhahn et al. Citation2018; Bekmeier-Feuerhahn, Rudeloff, and Adam Citation2016; Chen, Ji, and Men Citation2017). At the same time, the emergence and spread of innovative communication technologies, especially social media, have greatly changed the way organizations practice PR (Macnamara and Zerfass Citation2012; Guo and Saxton Citation2014). Social media networks as “web-based services that allow individuals to construct a public or semi-public profile within articulate a list of other users with whom they share a connection, and view and traverse their list of connections” (Ellison Citation2007, 211) are especially relevant for the PR of start-ups. They allow fast, cost-effective and direct communication between companies and their reference groups. Accordingly, recent studies, indicate that online and social media channels are extensively adopted for communication management of start-ups and are already perceived as more important than other opportunities to reach stakeholders such as media relations, fairs and events (Bekmeier-Feuerhahn, Rudeloff, and Adam Citation2016; Stokes Citation2000).

Over the last years, the implementation of social media for PR has gained in importance by firms (Qualman Citation2012). However, thus far, research in PR studies mainly investigated big and already established corporations, non-governmental organizations or public agencies (Schivinski and Dabrowski Citation2016; Vernuccio Citation2014; Men and Tsai Citation2014). Moreover, we found few studies on PR in Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs) (Moss, Ashford, and Shani Citation2004; Nakara, Benmoussa, and Jaouen Citation2012). Prior studies cover research on how social media can be used to attract customers (Chen, Ji, and Men Citation2017) or recruit employees (Kadam and Ayarekar Citation2014). Furthermore, authors have pointed out that engagement in social media can result in more positive behavioural outcomes from stakeholders, such as word-of-mouth or loyalty (Men and Tsai Citation2014).

One of the major challenges which start-ups face due to their newness and which they need to overcome to survive is the lack of reputation and legitimacy (Petkova, Rindova and Gupta Citation2008). Consequently, it is crucial for start-ups’ communication to raise awareness and build up relationships with stakeholders (Chen, Ji, and Men Citation2017). Compared to large, multinational companies (Bresciani and Eppler Citation2010), start-up firms dependent much more on stakeholder engagement in order to build up their brands and to facilitate reputation and legitimacy (Witt and Rode Citation2005).

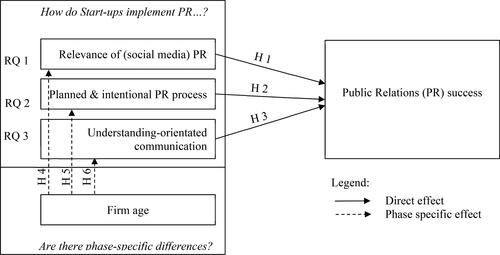

Even though there are some studies showing that PR is used by start-ups and that in particular social media plays a significant role for entrepreneurial PR practices (Bekmeier-Feuerhahn et al. Citation2018; Bekmeier-Feuerhahn, Rudeloff, and Adam Citation2016; Bekmeier-Feuerhahn, Rudeloff, and Adam Citation2016; Chen, Ji, and Men Citation2017; Men, Ji, and Chen, Ji, and Men Citation2017), these studies do not address empirically the influence of PR on communication success of start-ups. Men, Ji, and Chen, Ji, and Men (Citation2017) explicit call for quantitative studies in this context. Our study aims to fill this research gap in identifying success factors for start-up PR. In particular, we followed three main research questions (RQ) to examine how entrepreneurs assess the relevance of the adoption of PR practices (RQ1). If and how entrepreneurs choose long-term planning PR practice (RQ2). And, if and how they adopt communication strategies (RQ3). From this starting point, we developed three hypotheses examining the influence of entrepreneurial PR practices on communication success.

Furthermore, existing literature does not take into account the organizational life cycle and dynamic perspective on new venture development. New venture development follows uniform patterns and evolves through various stages over time (Levie and Lichtenstein Citation2010), which impacts also the way how brand building is practiced in start-ups (Juntunen et al. Citation2010). To address this gap in the literature, we include a dynamic perspective and study entrepreneurial PR through different temporal age stages within new venture development.

We utilize a quantitative survey among 453 start-ups in Germany. The empirical analysis focuses on entrepreneurial PR on Facebook, as it is the social network with the greatest reach in Germany (Comscore 2019). The article concludes with a comprehensive description of the empirical results and a discussion of its main implications. By combining literature on public relations and entrepreneurial marketing, we offer insights into the management of social media PR in start-up environments.

2. Theoretical background: Social media PR in start-ups

2.1. PR in social media

PR refers to intentional communication processes that coordinate actions and clarify interests between companies and their stakeholders, thereby making a value contribution to organizations (Zerfass Citation2010). Typical instruments for PR are press releases, fairs, events with customers and company or product websites. Gaining popularity, social media has changed dramatically the way consumers interact with each other but also with organizations (Solis and Breakenridge Citation2009). It has therefore been adopted intensively for PR. This is especially true for Facebook being the most popular social media channel with the highest reach (Comscore 2019). The potential of social media for start-ups is seen primarily in the no- or low-cost-functionalities to reach and interact directly with stakeholder groups and, furthermore, in positive effects on enterprise performance (e.g. Pakura and Pakura Citation2015).

In this context, existing studies demonstrate the prevalence of the adoption of social media for PR by start-ups. Communication with stakeholders in online and social media channels was evaluated by entrepreneurs as more important than traditional opportunities such as advertisements, fairs and events or media relations (Bekmeier-Feuerhahn, Rudeloff, and Adam Citation2016). This study also finds that a mixed model approach of informative and dialogue communication practices was chosen by entrepreneurs, leaving open the question of whether these practices actually lead to success.

Men, Ji, and Chen (Citation2017) examine stakeholder’s relationship cultivation techniques and PR practice in start-ups. They find that customers and employees are the most important strategic public stakeholders for new ventures. In a similar approach, Men, Ji, and Chen (Citation2017) investigate the strategic use of social media for stakeholder engagement, thereby showing that, among others, building image and reputation count among the primary purpose of start-up’s PR in China. In the context of online communication, Bekmeier-Feuerhahn et al. (Citation2018) examine different communication types and identify differences between intentional and emergent communication practices for entrepreneurial communication. Moreover, results indicate that intentional communication strategies seem to be a success factor in online communication management. Authors call for further research on this proposed relationship, in particular for empirical studies.

Studies from the field of entrepreneurial marketing, explicitly take into account the characteristic organizational framework conditions of start-ups, such as the newness of the company, a high level of uncertainty and the typical lack of resources (Gruber Citation2004; Hills, Hultman, and Miles Citation2008). In this regard, Stokes (Citation2000) argues that the way entrepreneurs practice marketing differs from those practices in larger and already established corporations. The author conclude that the start-up’s marketing practices can be characterized by the use of interactive media and word-of-mouth (Stokes Citation2000). However, entrepreneurial marketing studies investigate communication only peripherally and locate it as one of the four marketing instruments beside price, place and product. In this research field the understanding of entrepreneurial communication is based on a definition of communication as promotion of products and services to consumers in order to increase directly a corporation’s profit.

In contrast, PR studies conceptualize communication with a broader scope as a management function that builds relationships with stakeholders in order to create tangible and intangible values for the organization. Intangible values as described by Zerfass and Viertmann (Citation2017) are corporate culture, brand and reputation. In this context, the central role of PR is to manage processes that positively influence corporate culture, the positioning as a brand and the reputation of an organization (Grunig Citation2006). As corporate culture relates to the internal creation of intangible values, in our study we will concentrate on brand and reputation as two forms of “relational capital” (Hormiga, Batista-Canino, and Sánchez-Medina Citation2011), which depend on external relations of the company.

2.2. PR outcome: Brand and reputation

Referring to the measurable contribution that PR contributes to company success, positioning as a brand and building up reputation can be defined as the outcome level of communication success (Einwiller and Boenigk Citation2012). In contrast to outflow (financial performance) and output (reach of communication activities) outcome means the achievement of predefined communicative objectives on the level of the perceptions of the stakeholders.

Brands are conceptualized as knowledge structures in consumer’s minds that can influence their buying behavior at the level of attention and learning, interpretation, evaluation, and choice (Hoeffler and Keller Citation2003). In positioning as a brand in a market a company addresses the expectations and interests of stakeholder groups in order to create organizational trust (Welter and Smallbone Citation2006), thus enlarging the scope of possible actions (Zerfass Citation2008). Reputation, on the other hand, can similarly be described as collective judgments of companies based on the assessment of their products and services over time (Barnett, Jermier, and Lafferty Citation2006; Hormiga, Batista-Canino, and Sánchez-Medina Citation2011). Regarding the term reputation, Barnett, Jermier, and Lafferty (Citation2006) identified in a meta-analysis three dimensions of reputation that interact with another: awareness, assessment and asset. Applying these dimensions in the start-up context, creating awareness refers to reputation as it “generates perceptions among employees, customers, investors, competitors, and the general public about what a company is, what it does, what it stands for. These perceptions stabilize interactions between a firm and its publics” (Fombrun and Van Riel Citation1997, 6). It aims for start-ups to be perceived and recognized by the relevant stakeholder groups. Moreover, awareness is the prerequisite for positive assessment. In order to increase the probability that the stakeholders are willing to interact with the start-up in a way that is intended by the firm (e.g. buy products or invest in the company) (Shane and Cable Citation2002), awareness should be developed into positive assessments. As a consequence of the intended interactions, the start-up may become more successful in terms of revenue, profit or market capitalization. In this light, reputation presents an asset as it also influence the economic success of a company, which means in our context first of all the survival of the start-up.

To conclude, while the brand focuses primarily on relations with customers, reputation relates more to other stakeholder groups such as investors or suppliers. As intangible values, they are both crucial for start-up development, as they build the basis for creating tangible assets, such as revenue and profit. It can be argued that intangible values are even more important than tangible values for entrepreneurs, as daily operations in start-ups normally are less dependent on cash flow (Zerfass and Viertmann Citation2017; Lichtenstein and Brush Citation2001).

2.3. Adoption of PR practices by start-ups and its relevance

Reijonen et al. (Citation2012) show that brand orientation plays a critical role in guiding a firm’s growth. They examined how market and brand orientation of SMEs influences their performance on the level of revenue, market share, profitability, and number of employees. The results showed that “brand orientation differentiated the declining, stable, and growing SMEs most clearly” (p. 711), indicating that growing firms are significantly more brand-oriented. Similarly, Berthon, Ewing, and Napoli (Citation2008) assess whether the performance of SMEs may benefit from building brands. They conclude that high-performing SMEs implement brand orientation to a greater extent than low-performing SMEs. In their study brand-focused SMEs were able to achieve a distinct performance advantage over rivals by “effectively communicating the brand’s identity to internal and external stakeholders” (p. 40), which indicates that communication is one key element to successful brand building. This in in line with brand management literature (e.g. Keller Citation2009) which assumes that organizations should try to create an appropriate and distinct brand positioning that must be communicated consistently to the target audiences. However, Reijonen et al. (Citation2012) as well as Berthon, Ewing, and Napoli (Citation2008) do not take into account the characteristics of start-ups.

In order to assess the way PR – as the organizational function to build up brand and reputation – is implemented in start-ups, it is essential to take into account their organizational characteristics. While organizations that are already known in the market can fall back on established relationships with their customers, it is part of the “Liability of Newness” of start-ups (Stinchcombe and March Citation1965; Rao, Chandy, and Prabhu Citation2008) that these relationships must first be built up to win the stakeholders’ trust.

At the same time, start-ups usually have limited financial resources, which makes the adoption of social media for PR highly appropriate and essential to them (Abimbola Citation2001; Men, Ji, and Chen, Ji, and Men Citation2017). This is critical, as research indicates that reputation is generally positively influenced by high investments in advertising (Milgrom and Roberts Citation1986), which is normally no option for start-ups.

Social Media such as Facebook facilitate the creation of organizational relationships through low-cost functionalities. Contrary to traditional and typically expensive PR tools, social media allows start-up firms to engage in timely and direct stakeholder contact at relatively low cost (Bresciani and Eppler Citation2010), while at the same time provides higher levels of efficiency (Kaplan and Haenlein Citation2010). Thus, social media PR may be highly relevant for start-ups, as there is a special need to create awareness and positive assessments under uncertain conditions and increase the willingness to cooperate on the part of customers and other stakeholder groups without investing high budgets. This is especially important as brand and reputation are normally attributed by consumers based on a company’s past performances (Fombrun and Shanley Citation1990;), which in the case of new ventures is not yet possible.

Until today, only few insights exist in entrepreneurial marketing concerning intangible values such as reputation and brand. Furthermore, results from existing studies regarding the role of PR in start-ups present inconsistent findings. From a theoretical viewpoint, Bresciani and Eppler (Citation2010) and Petkova, Rindova, and Gupta (Citation2008) agree on the relevance of PR for brand building, but authors’ empirical findings differ regarding the actual PR practices of start-ups. While Petkova, Rindova, and Gupta (Citation2008) describe how PR is implemented by new ventures to create awareness and reputation among stakeholders, Bresciani and Eppler (Citation2010) found that only few start-ups paid attention to their PR activities. Laukkanen et al. (Citation2016) show that brand orientation is a success factor for market orientation of entrepreneurs, but they do not take into account the role of PR for brand building.

In light of the above, there is a gap between the theoretically proposed relevance of the adoption of PR in general by start-ups and its perception by the entrepreneur. In particular the adoption of social media PR by start-ups and its communication outcome calls for empirical evidence. We conclude with the following research question and hypothesis:

RQ1: How do entrepreneurs assess the relevance of the adoption of PR practices in general, more precisely the relevance of the implementation of social media PR compared to non-social media practices?

H1: The perceived relevance of social media PR is positively associated to PR outcome as positioning as brand and reputation on social media.

2.4. Start-up’s PR planning

To create intangible values, organizations must implement PR strategically, aligned to overriding corporate objectives. According to Grunig and Dozier, PR is the “overall planning, execution and evaluation” of communication. PR therefore is (ideally) planned systematically and for the long term. Consequently, the literature assumes that planning is a prerequisite for successful PR (Bruhn Citation2008). PR planning, e.g. setting objectives and developing key messages, supports the long-term orientation of communication (Hallahan et al. Citation2007), and is therefore seen as a positive impact factor for PR outcome (Grunig and Huang Citation2000). It is assumed that companies that carry out intentional and planned communication management are more likely to achieve their objectives than unplanned communication programs (Grunig and Dozier Citation2003).

At the same time, given their newness, often there are no established operating routines and roles in start-ups (cf., Stinchcombe and March Citation1965). Also, startups usually have limited know-how and time (Abimbola Citation2001; Men, Ji, and Chen, Ji, and Men Citation2017). And, the entrepreneur, who normally has no professional background in PR, plays an overriding role in communication and branding activities (Bresciani and Eppler Citation2010). While PR planning seems to be crucial, its evaluation and implementation by the entrepreneur is challenged by organizational and individual restrictions such as a lack of time and skills. Accordingly, prior studies show that only every second (Bekmeier-Feuerhahn et al. Citation2018; Einwiller and Boenigk Citation2012) or rather every third entrepreneur (Hills, Hultman, and Miles Citation2008; Lumpkin, Shrader, and Hills Citation1998) engages in formal planning. While at the same time first insights show that for SMEs applying an overall planned communication concept correlates with the communication outcome of SMEs (Einwiller and Boenigk Citation2012). We conclude with the following research question and hypothesis:

RQ2: Do entrepreneurs choose long-term planning PR practices?

H2: Long-term planning of PR is positively associated to PR outcome as positioning as brand and reputation on social media.

2.5. Understanding-oriented PR and start-ups

Based on Grunig and Hunt (Citation1984) fundamental organizational PR model and its further development by Morsing and Schultz (Citation2006), a distinction can be made between informative, persuasive and understanding-oriented communication strategies. Start-ups may, for example, orient themselves towards an informative communication model by focusing on the dissemination of relatively objective information to a broad public, e.g. through information brochures or press releases (Zerfass Citation2010). Alternatively, they could make use of a persuasive communication model with an emotional advertising campaign.

In contrast, the understanding-oriented model focuses on an open dialogue with the stakeholder groups, aimed at mutual understanding. In this context, trust is conceptualized as an indicator for good organization-public-relationships (Ledingham and Bruning Citation1998) and can therefore be seen as a crucial communication objective within the understanding-oriented PR model. The monitoring of the relevant stakeholder groups (environmental scanning) and the implementation of their views in organizational practices of the start-up thus is essential for understanding-orientated PR (Hallahan et al. Citation2007). Morsing and Schultz (Citation2006) emphasize the aspect of involving the stakeholder groups in order to understand and adapt to their concerns, which differentiates the understanding-oriented PR from other communication models. The technical possibilities of social media offer enormous potential for start-ups as they allow the monitoring of stakeholder interests with low costs (Kane et al. Citation2012). There are also first insights showing that the understanding-oriented model seems to be appropriate to build up brand positioning and reputation (Kang and Sung Citation2017), which is crucial for start-ups. Hence, the following research question and hypothesis are formulated:

RQ3: Do entrepreneurs adopt understanding-oriented PR strategies?

H3: Understanding-oriented PR is positively associated to PR outcome as positioning as brand and reputation.

2.6. Differences of start-up’s PR within new venture development

It is assumed that the growth of new ventures in terms of sales, employment or market share proceeds in phases moderated by firm’s age (Levie and Lichtenstein Citation2010; Baum, Locke, and Smith Citation2001) and that each phase involves individual stakeholder constellations and, thus, specific problems for organizational development (Kazanjian Citation1988). As Juntunen et al. (Citation2010) demonstrate, this also impacts the way how start-ups practice their brand management. They show that in the pre-establishement phase entrepreneurs begin to develop their brand by creating relationships with first stakeholder groups. At this moment, the company’s corporate brand building process starts, which is intensified in the early growth stage. The effective growth stage maintains or revises this process. Furthermore, Bekmeier-Feuerhahn, Rudeloff, and Adam (Citation2016) theoretically discussed the impact of growth stages on how social media PR is practiced differently within the new venture development. As a result, they call for further empirical evidence.

Although there exists a multitude of differentiated growth models in the literature, a common distinction is made between two main phases: the start-up stage and the growth stage (Mueller, Volery, and von Siemens Citation2012). Following Kazanjian (Citation1988) as well as Juntunen et al. (Citation2010) it can be expected that the way start-ups practice PR varies with start-up’s age and a growing history of firm behavior and outcomes. Especially in the start-up stage, the lack of organizational trust is a crucial problem (Singh, Tucker, and House Citation1986). While, the longer the company is in the market, the less significant this problem should become (Singh, Tucker, and House Citation1986). Hence, it can be assumed that in the start-up stage the relevance of PR and creating trust are particularly important as PR objectives. Regarding communication models, consistently understanding-oriented PR should be the main focus in this stage.

Both start-up and growth stage involve not only individual stakeholder constellations but also specific management and behavioral patterns of the entrepreneurs (Mueller, Volery, and von Siemens Citation2012). For the growth stage it is characteristic that an internal differentiation, specialization und professionalization of management functions takes place. While in the start-up phase, the entrepreneur dominates all processes and decisions (Hussain, Shah, and Akhtar Citation2016), this will later be gradually transformed into a function of management and empowering of employees (Lichtenstein, Dooley, and Lumpkin Citation2006). This replacement of broad overlapping roles into more specialized roles (Hanks and Chandler Citation1994) could mean for PR that the entrepreneur is no longer the only person in charge and that more specialized staff with communication backgrounds comes into play. Therefore, the way PR is practiced may develop from an ad-hoc-activity to a more strategically managed and planned form of PR. As specialized employees with communication specific knowledge enter the start-up, the relevance of long-term planning will probably grow, as PR professionals widely accept the potential of strategic planning as a success factor (Grunig and Huang Citation2000). Long-term PR planning as being one central element of strategic communication management should therefore increase in the later phases. Hence, we conclude with the following research hypotheses:

H4: There are phase-specific differences within start-up development regarding the relevance of social media PR.

H5: There are phase-specific differences within start-up development regarding long-term planning of PR.

H6: There are phase-specific differences within start-up development regarding the implementation of understanding-oriented PR strategies.

To clarify and to summarize our research model, see .

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample and procedure

The study is based on a German panel data set, monitoring young micro and small enterprises annually through periodical surveys (see Lambertz and Schulte Citation2013 for details about the panel data). Panel surveys are carried out through standardized one-page questionnaires, which contain recurring questions assessing the firm’s and corporate development (e.g. sales volume, quantity of staff, perception of the current and future business situation) as well as non-recurring questions focusing on specific topics that differ in each panel wave (e.g. PR, social networks, or entrepreneurial communication management). The panel concept allows controlling for survivorship bias (see Pakura and Pakura Citation2015). Working together with the LGH association, which is a joint institution of seven craft chambers in the western part of Germany, we designed and conducted our survey in late 2013. Additionally to our survey, the LGH association provided us with access to an enterprise database with detailed data on the respective business, providing additional information about the age of the enterprise, the firm’s business sector, and the entrepreneur’s gender. Based on the data obtained from the enterprise database, we could assess differences across respondents and non-respondents by conducting independent-sample t-test and found no differences between the two groups, suggesting that non-response bias is not a problem. Furthermore, comparing our data set with secondary data from the German Federal Statistical Office for the crafts business sector, we found high correlation between both data, suggesting that it is quite likely that our data presents a representative sample for micro and small enterprises for the German crafts industry. To examine our research questions, we focused solely on start-ups using social media for their PR. After excluding data on firms that did not use social media for their PR strategies, we retained a sample of 453 start-ups. All questionnaires were completed by the firm owner. briefly describes the data set.

Table 1. Sample descriptive statistics: Mean, standard deviation (S.D.), median.

3.2. Questionnaire and variables

We conducted questions referring to our research questions and the variables derived from them. The items to operationalize the variables were developed in a two-step approach. First, we developed the items based on the relevant literature from the theoretical background. Second, we pre-tested the items together with experts from the seven craft chambers of the LGH association and social media PR experts from the university. According to the experts’ assessments, we adapted the questions in line with their validation. Appendix 1 briefly displays the definitions of the key variables, the measurements and the respective sources.

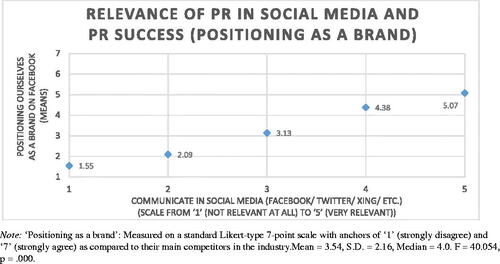

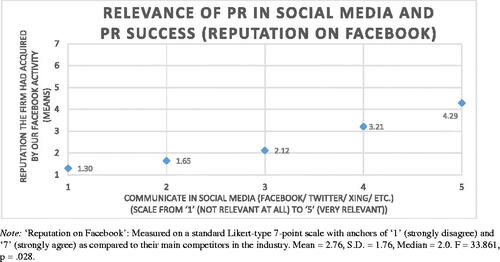

To measure PR success we refer to the concepts of ‘brand’ and ‘reputation’ as described in Zerfass (Citation2008) and Fombrun and Van Riel (Citation1997) as communication outcome. We use two items adapted from literature and experts’ valuation and asked respondents to provide an assessment for each item: ‘brand positioning on Facebook that the firm had acquired by the firm’s Facebook activity’ (Morgan, Vorhies, and Mason Citation2009) and ‘reputation that the firm had acquired by the firm’s Facebook activity’ (Hormiga, Batista-Canino, and Sánchez-Medina Citation2011) – each item rated relative to their major competitors in the industry on a Likert-type 7-point scale.

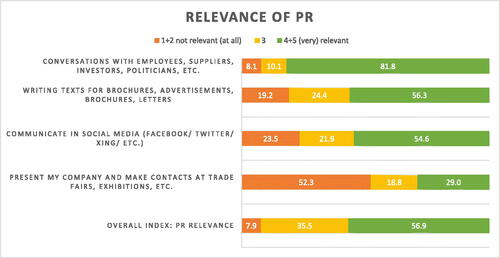

To measure relevance of PR we relied on items that were developed by Bekmeier-Feuerhahn, Rudeloff, and Adam (Citation2016) as well as Zerfass et al. (Citation2007) and adapted an item according experts’ valuation. To measure relevance of social media PR we asked respondents to provide an assessment for: ‘the relevance of social media communication – more precisely social media PR (on Facebook, Twitter, Xing)’ – each item rated on a Likert-type 5-point scale (Bekmeier-Feuerhahn, Rudeloff, and Adam Citation2016). Additionally, we measure the relevance of three further PR concepts and calculated an overall index on the relevance of entrepreneurial PR by averaging all four items (Cronbach’s alpha = .600). Again, respondents were asked to provide an assessment for ‘the relevance of these three non-social media related PR concepts: ‘conversations with stakeholders’, ‘writing and providing texts’, and ‘taking part in trade fairs or exhibitions’ – each item rated on a Likert-type 5-point scale (Bekmeier-Feuerhahn, Rudeloff, and Adam Citation2016).

Long-term PR planning was assessed in terms of planned and intentional aspects by asking the entrepreneurs about their long-term PR plan commitment. Adapted from literature on the aspects of strategic PR management as described by Grunig and Dozier (Citation2003) entrepreneurs were asked ‘whether they favor planned and intentional communication based on a long-term over ad-hoc communication activity within their communication management’ – each item rated on a Likert-type 4-point scale (Bekmeier-Feuerhahn, Rudeloff, and Adam Citation2016).

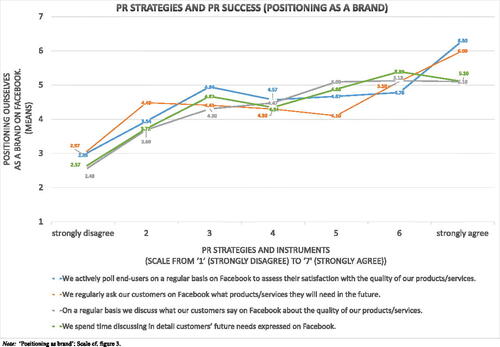

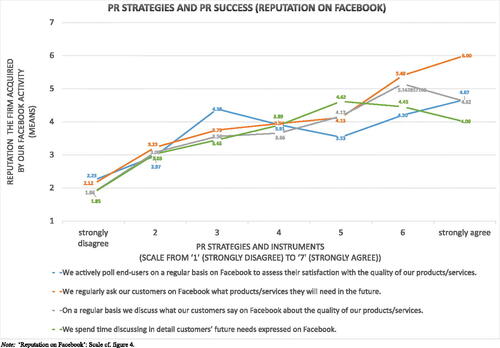

The understanding-oriented PR model is based on Grunig and Hunt (Citation1984) and Morsing and Schultz (Citation2006) and adapted according experts’ valuation. We assessed an understanding-oriented PR model in terms of ‘trust building mechanisms’, ‘dialog conversations’, and ‘environmental scanning’. Measuring trust building mechanism respondents were asked ‘whether they consider the PR model for building trust in a defined circle to be more important than achieving wide publicity in a broad public’ – each item rated on a Likert-type 4-point scale (Ledingham and Bruning Citation1998). Regarding ‘dialogic communication’ and ‘environmental scanning’ items refer to Morgan, Vorhies, and Mason (Citation2009) marketing orientation scales, which have been adapted to match understanding-oriented PR in the context of Facebook. Five items were used to measure the amount of effort put into dialogic conversations and environmental scanning on social media. Respondents were asked ‘how much they agree or disagree with each of the statements’ (Morgan, Vorhies, and Mason Citation2009). Each item was scored on a Likert-type 7-point scale with anchors of ‘1’ (strongly disagree) and ‘7’ (strongly agree). displays the five statements in detail.

Table 2. PR strategies and instruments: Mean, standard deviation (S.D.), median, and Pearson’s r value.

Finally, to measure phase-specific differences in PR practice, we us the firm’s age as a metric variable, as well as two temporal firm stages in our study: one indicating early stage, the other later stage start-ups.

4. Results

4.1. PR relevance and the adoption of social media for PR

First, we present results referring to the research question RQ1 of how entrepreneurs assess the theoretically assumed relevance of PR practices in general for their startup, more precisely how they evaluate the relevance of the implementation of social media PR compared to non-social media PR practices. Second, we analyze whether the perceived relevance of social media PR relates to PR success as positioning as brand and reputation on Facebook (H1). To evaluate the relevance of PR for start-ups we studied four different PR concepts and asked respondents how relevant they deem these concepts. displays the descriptive statistics of these PR concepts and the calculated overall PR relevance index. Results show that for start-ups PR is of high relevance. 50 per cent (median) of all entrepreneurs score for an overall PR relevance index value equal ‘4’or ‘5’ on a scale from ‘1’ (not relevant at all) to ‘5’ (very relevant) (mean: 3.50, S.D. = 0.79). Descriptive statistics indicate the relevance of PR for start-ups. Conversations with stakeholders score highest: Of all entrepreneurs, 82 per cent agree that conversations with relevant stakeholder groups are very relevant for their start-up (mean = 4.27, S.D. = 1.05). Second important is the concept of writing and providing texts (56 per cent agree, mean = 3.70, S.D. = 1.13). Social media PR, such as on Facebook, Twitter, and Xing, is perceived as being of strong relevance for 55 per cent of all start-ups (mean = 3.5, S.D. = 1.24). In contrast, taking part in trade fairs or exhibitions for PR is seen as relevant only by less than one third of all new ventures (mean = 2.6, S.D. = 1.38).

Regarding social media PR concepts, we studied the network Facebook in detail. indicates a description of the Facebook activities of all start-ups within the sample.

Table 3. Facebook specific descriptive statistics: Mean, standard deviation (S.D.), median.

With social media emerging as PR concept, Facebook activities became more important. We conducted bivariate analyses to test this assumption. Results of both variance and correlation analyses show that start-ups, who evaluate the relevance of the PR strategy in social media as being more important, similarly score significantly higher on Facebook activities. Analyses of variance show that means for Facebook activities significantly (p = .000) differentiate within the different scoring of the evaluation of the communication relevance of social media. For example, start-ups who answered that they deem social media to be very relevant show on average 351 Facebook contacts (S.D. 294) and reported to interact 5.8 hours per week with their Facebook contacts (S.D. 6.7). Furthermore, they have significantly more groups (mean = 4.5, S.D. = 7.4) and post significantly more news/photos on average (mean = 7.0, S.D. = 12.0).

The positive correlation between the perceived social media relevance for PR and the actual social media activity on Facebook is supported by bivariate correlation analysis (Spearman’s Rho and Pearson’s r correlation). All items for Facebook activity show significant positive correlation with social media PR relevance evaluation – correlation coefficients ranging between r = .187 and r = .549 (p-value ≤ .05).

To refer to hypothesis H1 and test the extent to which perceived social media PR relevance actually relates to PR success on Facebook, we conducted further analyses. Analyses of variance ( and ) and correlation analyses indicate a significant positive relationship between relevance for PR in social media and PR success as measured by brand positioning and reputation on Facebook.

Correlation analyses support these relationships. Analyses show high correlation coefficients for both: positioning as brand (r = .563, p ≤ .001) and reputation (r ≤ .590, p ≤ .001). The more relevant the respondents deem the PR concept of social media use, the higher the scores of the measured PR outcome as brand and reputation achievements.

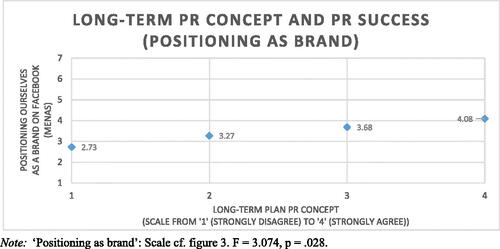

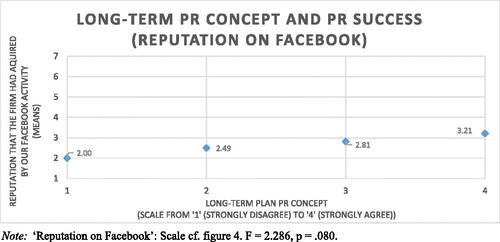

4.2. PR planning

To further assess the relevance of strategic PR management for start-up PR, we asked the entrepreneurs about their long-term communication plan (RQ2). Of all answers the mean is 2.73 (S.D. = .85), 50 per cent (median = 3) are more likely to agree or even strongly agree to evaluate a long-term plan as relevant. To refer to hypothesis H2 and test the assumption of the impact of long-term planning on PR success on Facebook, we conducted analyses of variance and bivariate Pearson correlations. Both support a positive relationship between a long-term PR strategy and PR success. and show steady and significant increase in means with an increase of long-term plan relevance. At the anchor ‘strongly agree’ to access long-term PR concept as favorable, values achieve means of 4.08 (S.D. = 2.16) for success as building up brand and 3.21 (S.D. = 1.79) for success as reputation. Pearson correlation analysis supports the positive relationship (brand: r = .166, p ≤ .01; reputation: r = .173, p ≤ .01).

4.3. Understanding-oriented PR

Referring to the implementation of PR models (QR3), i.e. to what extent start-ups practice understanding-oriented PR on Facebook, descriptive results show a weak implementation of understanding-oriented PR. All items for understanding-oriented PR show very low means and medians ().

However, conducting bivariate analyses between understanding-oriented PR and social media PR relevance, results show that with higher relevance of social media as PR concept, means relating to understanding-oriented PR significantly increase. With one exception: means for the first item ‘Trust in a defined circle is more important than wide publicity in a broad public.’ remain at the same low level independently of the perceived social media PR relevance. Conducting further analyses of variance, in case of the other five items, values significantly increase with the increasing importance of social media PR relevance, but remain at low values. Means at the most achieve values of 4.14 (S. D. = 2.3) on a Likert-type 7-point scale when social media PR relevance is rated at the highest level (anchored ‘5’ – very relevant). This is the case for the item ‘On a regular basis we discuss what our customers say on Facebook about the quality of our products/services’.

Even though understanding-oriented PR is conducted at relatively low levels by the start-ups, further analyses indicate a significant relationship between understanding-oriented PR and communication success on Facebook (H3). Four of the six items show significant higher success values with an increase in understanding-oriented PR (cf. displaying the correlation coefficients with PR success as brand positioning and reputation). Again, the item ‘On a regular basis we discuss what our customers say on Facebook about the quality of our products/services.’ shows highest correlation with PR success. The item ‘Trust in a defined circle is more important than wide publicity in a broad public.’ indicates a negative significant correlation, meaning that achieving wide publicity in a broad public seems to appear more important for PR success measured on Facebook. Analyses of variance support these findings, indicating exactly the same four items as being significantly positively related with PR success ( and ).

Table 4. PR strategies and instruments: t-test, mean, standard deviation (S.D.), F-value and p-value.

4.4. PR in start-up stages

To study hypotheses H4, H5, and H6 and test the assumption whether phase-specific communication can be empirically supported, we conducted bivariate analyses referring to the start-up’s age and differentiated between early and late start-up phase. According to Lambertz and Schulte (Citation2013), the process of early development of the new venture can last up to five or at most six years for SMEs. Likewise, Mueller, Volery, and von Siemens (Citation2012) argue that, after an age of five years, the start-up phase ends and the firm enters a growth phase. We adopted these concepts measuring the start-up phase – as proposed by Lambertz and Schulte (Citation2013) – up to at most six years. We conducted analyses of variance and correlation tests between the start-ups’ age and the PR concepts to find out age depending phase-specific differences. Furthermore, we cut data at the median of the start-ups’ age and conducted t-tests for very young start-ups with a firm age of up to 31 months in comparison to older start-ups with a firm age of 32 months or more (but no more than 84 month). Referring to H4, results show no significant age- or phase-specific effect for the perceived relevance of three out of the four discussed PR concepts (as displayed in ). With one exception: The relevance of the PR concept of social media (item: communicate in social media) shows significant t-test results (F = .314, p = .039) between younger and older start-ups, meaning that the PR concept social media is more relevant for younger enterprises than for older ones. Younger start-ups report a mean-value of 3.6 (S.D. = 1.2), whereas older start-ups report a mean-value of 3.3 (S.D. = 1.2). The difference is small, but significant. Variance analysis supports this assumption. Results report a decrease in relevance of social media PR with an increase in start-ups’ age – for social media PR relevance the mean in age t = 0 years is 3.5, whereas the mean in age t = 7 years is 2.7. Although the effect measured is low, for the overall index of PR relevance this phase-specific difference is significant as well. In the early start-up phase, entrepreneurs consider PR as more relevant (mean = 3.6, S.D. = .8) than older start-ups (mean = 3.4, S.D. = .8) (t-test: F = .868, p ≤ .05). Pearson correlation supports the negative relationship between overall PR relevance and start-ups’ age (r = -.94, p ≤ .05).

Referring to H5 and the analyses of phase-specific differences within start-up development regarding long-term planning of PR, results are not robust. For younger start-ups t-tests (F = .837, p = .030) indicate a slightly higher relevance of long-term planning with a mean of 2.8 (S.D. = .85) than for older start-ups (mean = 2.6, S.D. = .83). However, bivariate analyses conducting analysis of variance and correlation with the start-ups’ age show no significant relation between long-term planning and the start-ups’ age.

Finally, examining the assumption that the understanding-oriented PR shows phase-specific differences (H6), analyses indicate phase-specific differences, even though – as discussed above (cf. ) – results show a weak PR model implementation. Conducting t-test analyses, results show significant differences for four of the six items of the construct understanding-oriented PR (cf. ). As means display, for younger start-ups understanding-oriented PR is significantly more relevant than for older start-ups. The item ‘Trust in a defined circle is more important than wide publicity in a broad public.’ and ‘Regularly asking customers for product/service needs in the future.’ indicate no significant difference, meaning that trust as a communication objective and regularly asking for customer future needs seem to appear as important for younger as for older start-ups.

5. Discussion and conclusions

This study investigates the adoption of social media PR practices by start-ups, how PR activities vary between start-ups’ age and how start-ups’ PR practices relate to PR success in terms of communication outcome as building up brand and reputation. Our results show that social media PR positively contributes to communication outcome. Moreover, findings indicate that social media PR is practiced differently depending on the start-ups’ age. Therefore, it is crucial to integrate a dynamic perspective on entrepreneurial PR.

We theoretically discuss and empirically support three main factors that appear to be crucial for the success of entrepreneurial communications in social media: the ‘perceived relevance of PR’, ‘conducting long-term planning PR practices’ and ‘implementing an understanding-oriented communication’. Further, results show that over 90 per cent of all entrepreneurs valued the relevance of PR practices in general as highly relevant for their start-up (cf. ).

5.1. Factors for social media PR success

First, the start-ups in our sample, which perceived PR in social media as more relevant and showed more PR activity had a higher reach (external output), also evaluated their reputation and their positioning as a brand on Facebook significantly more positive (indirect outcome). This result confirms the role of PR for start-ups as creator of intangible values and is in line with basic assumptions of PR and communication management literature for established companies, such as e.g. the IABC Excellence Study (Grunig and Dozier Citation2003) which demonstrates how communication helps organizations to be more effective.

Second, there is a positive impact of long-term PR planning on communication outcome. The ‘long-term planners’ in our sample show more success in creating reputation and brand positioning on Facebook than their competitors, which confirms that Vercic and Zerfass’ (2016) results can be adapted to start-ups. Vercic and Zerfass (Citation2016) demonstrated that communication departments of companies, non-profits and governmental organizations who rely on planned and prepared PR strategies are significantly more successful regarding their communication outcome than communication departments without a strategic approach. This is in line with our finding, which confirms the importance of a strategic PR approach also in the context of start-ups’ communication success. Likewise, referring to Einwiller and Boenigk (Citation2012), who showed that applying an overall communication concept correlates significantly with the communication outcome of SMEs, our study provides first empirical insights to support this findings for start-ups too. Moreover, when integrating a dynamic entrepreneurial approach, our study sheds first light on the idea that the effect of long-term PR planning on communication outcome is not static, but vary according to the start-ups’ age. We find, that for very early start-up phases a long-term PR plan seems to be more vital to communication success than for older start-up firms. Future research should examine entrepreneurial PR under a dynamic approach of different growth stages in more detail – we propose a longitudinal study as an appropriate approach.

Referring to the research stream of different management schools as described by Mintzberg and Waters (Citation1985), our results contribute evidence for the direction of the ‘planning school’ that can be characterized by deliberate and formalized planning processes and is opposed to more emergent and adaptive strategies. This is somehow surprising, as the lack of communication specific skills and routines in start-ups can be seen as predestining factors for more emergent or ad-hoc communication strategies – especially in the early developmental stage. As Hills, Hultman, and Miles (Citation2008, 7) indicate successful entrepreneurs do not necessarily operate their marketing in the “rational, sequential manner” and tend “not to be constrained by their previous conceptualization of strategy, but quickly adapt their strategy to the new set of opportunities”. On the other hand, as our sample does not consist of innovative ventures but of typical founders from the crafts sectors, the industrial context might explain this result. It could be assumed that in the context of the crafts industry, the degree of uncertainty in the organizational environment is lower than for innovative start-ups, which makes a deliberate and formalized planning approach more suitable. Accordingly, future research should further examine different management schools in the context of PR for young start-ups, thereby also taking into account industry specific differences.

Third, regarding the communication approach of an understanding-oriented PR model, our study indicates a significant positive relationship with communication outcome on Facebook for those start-ups that choose an understanding-oriented PR approach. This meets our theoretical assumptions concerning the role of this PR model to create reputation and brand positioning for start-ups (Ledingham and Bruning Citation1998) and, furthermore, confirms the PR literature assumptions on the impact of openness and responsiveness for communication outcome (Macnamara Citation2014).

However, results show a relatively weak implementation of understanding-oriented PR by start-ups yet. This partly contradicts our theoretical proposition considering the suitability of social media for stakeholder monitoring (environmental scanning) (Kane et al. Citation2012, Macnamara Citation2014) and interaction with stakeholder groups (dialog conversations) for start-ups (Kang and Sung Citation2017). When comparing our results to other findings from larger corporations (Rybalko and Seltzer Citation2010) or NGOs (Lovejoy and Saxton Citation2012), we conclude that start-ups in our study do not exploit the dialogue potential of Facebook adequately yet. This leads to future research considering the questions ‘why not?’ or ‘what hinders them?’.

5.2. Call for a more dynamical approach of entrepreneurial PR

Results showed that the adoption of social media for PR is more important for younger enterprises than for older ones. This may be explained by the perception of social media communication as low-cost and low-risk (Pakura and Pakura Citation2015) that predetermines its use especially for young start-ups who, compared to more developed enterprises, have to establish relationships with stakeholder under several resource constraints (Chen, Ji, and Men Citation2017) – in particular under a lack of financial ones.

Furthermore, results showed that a communication approach of understanding-oriented PR is significantly more utilized by younger start-ups than by older start-ups. This meets the expectations of our theoretical reflections and is in line with findings by Bekmeier-Feuerhahn, Rudeloff, and Adam (Citation2016), who suggest that younger start-ups more often apply understanding-oriented communication practices. While Petkova, Rindova, and Gupta (Citation2008) show how entrepreneurial communication strategies are used to build up reputation depend on the type of product the startup is offering, our results shed light on the influence, that different growth stages might have an effect as well – especially, when it comes to the implementation of different communication models.

According to the results stated above, our study found that entrepreneurs considered Facebook primarily as a tool for ‘environmental scanning’ instead of a channel to obtain specific communication objectives such as trust. Beyond that, we found that this is especially true for younger start-ups and varies significantly to older start-ups. The importance of this process of listening and the evaluation of stakeholders’ feedback via Facebook may be of high significance for early stage entrepreneurs, because in particular in the early stage start-up firms are in the very beginning of their organizational development and engage primarily in activities such as conducting market analyses in order to complete their business plan (Carter, Gartner, and Reynolds Citation1996; Cooper, Ramachandran, and Schoorman Citation1998). Accordingly, it can be assumed that the process of listening and the evaluation of stakeholder feedback via Facebook may be of high significance for entrepreneurs in the early stage not only for their PR, but also for product and service development.

To conclude, our study indicated that there are phase-specific differences of PR practices between younger and older start-ups. This confirms our theoretical assumption that integrating a dynamic perspective in studying entrepreneurial PR appears to be not only a new, but also promising research direction. While organizational life cycle or stage models (Levie and Lichtenstein Citation2010) have been adopted in entrepreneurship research (e.g. in the context of behavioural patterns of the entrepreneurs (Mueller, Volery, and von Siemens Citation2012)), until now studies in entrepreneurial communications have not focused on the impact of growth stages. In integrating a dynamic perspective on the adoption of PR by start-ups, our study extends the state of research.

5.3. Implications for practice and policy

Our study provides several implications for practice and policy. For entrepreneurs, it can be concluded that they should strengthen the role of social media PR within their start-up. Our results support the significant positive relationship between PR and communication outcome.

First, those start-ups that practice understanding-oriented PR have a higher communication outcome. Therefore, and according to the literature on the understanding-oriented communication model (Morsing and Schultz Citation2006), entrepreneurs are advised to initiate a dialogue with their stakeholders rather than putting the emphasis on a persuasive or informative communication approach. These dialogues should be based on systematic environmental scanning processes, for which social media such as Facebook offers huge potential (Kane et al. Citation2012). Second, long-term PR planning increased communication outcome, therefore start-ups are better advised to avoid intuitive ad-hoc-communication and should better develop a PR concept before starting to develop relationships with stakeholders on Facebook. This is especially true for very early star-up phases. Third, our findings suggest that start-up counselling should strengthen the creation of building social media PR capabilities and communication strategies in start-ups as part of their operational policy to achieve an effective communication success right from the beginning of the new firm development, and to reduce potential threats of failure. Hence, government officials and start-up advisors should consider programs aiming to sensitize start-ups to the important role of social media PR in general, but also from the very first day of communication activities.

5.4. Limitations and future research

This article has some limitations that leave room for future research. Due to our sample from Germany, the sample size, the focus on the crafts industry, and the social media network Facebook, the generalisability of our findings is limited. Our study provides empirical evidence that the usage of social media PR in strategic communication works well for start-ups. However, given the one-sided questionnaire survey, the study could not control for some variables that have been suggested by the conceptual literature as competitive advantages, such as the sociodemographic and the personality background of the business owner. Sociodemographic variables such as the age and educational level can be influence factors concerning social media usage (Perrin Citation2015). Personality traits may play a role such as, e.g. extraversion, and together with openness to experiences are positive predictors for social media usage (Correa, Hinsley, and De Zuniga Citation2010) and may therefore influence the way entrepreneurs engage in dialogues with their customers on Facebook. We cannot exclude that our results are impacted by unobserved heterogeneity. Accordingly, we conducted bivariate analyses and leave future research to conduct multivariate analyses – such as regression analysis with PR success as dependent variable. Our analysis was of an exploratory nature, which is in line with our research questions and our aim to contribute to the need for more empirical insights regarding the examination of PR practices of start-ups. Future research on this topic should include further variables and test our proposed conceptual model as discussed in the theoretical chapter (cf. ). Though, our theoretical discussion and first bivariate empirical evidence support the proposed conceptual model.

In this study, we have focused on the concepts of brand and reputation, which we operationalized via subjective measuring. One downside in this context is that founders may be biased by self-serving bias, which means the tendency of entrepreneurs to ascribe success to their own abilities and efforts in an overly favorable manner. As self-assessment of success only relies on the response given by entrepreneurs in our study, common source bias cannot be excluded. To diminish biases we operationalized the measurement by asking the respondents to evaluate success relative to their major competitors in the industry. Future research should utilize additional objective measurement, for example, positive or negative reviews from customers on Facebook.

We showed that different development stages are defined by different social media PR practices; however, future research should explore these differences within the start-up’s development in more detail. A longitudinal study might provide more insights. Finally, we suggest extending the research to a broader use of social media platforms apart from Facebook, such as e.g. Twitter, LinkedIn, or Xing.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the editor and two anonymous reviewers for constructive feedback and insightful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Stefanie Pakura

Dr. Stefanie Pakura is a postdoctoral researcher and lecturer at the Chair of Management & Digital Markets, Faculty of Business, Economics and Social Sciences of University of Hamburg. Her current research interests intersect various research streams, including entrepreneurship, technology and innovation, communication management, crowdfunding, big data, and social media.

Christian Rudeloff

Dr. Christian Rudeloff is professor for Media Management at Macromedia University of Applied Sciences, Hamburg, Germany. His current research interests are: communication management, public relations, entrepreneurship, media theory.

References

- Abimbola, T. 2001. “Branding as a Competitive Strategy for Demand Management in SMEs.” Journal of Research in Marketing and Entrepreneurship 3 (2): 97–106.

- Barnett, M. L., J. M. Jermier, and B. A. Lafferty. 2006. “Corporate Reputation: The Definitional Landscape.” Corporate Reputation Review 9 (1): 26–38.

- Baum, J. R., E. A. Locke, and K. G. Smith. 2001. “A Multidimensional Model of Venture Growth.” Academy of Management Journal 44 (2): 292–303.

- Bekmeier-Feuerhahn, S., J. Kollat, C. Rudeloff, and J. Sikkenga. 2018. “Intentional vs. Emergent Strategies of Online Communication of Start-Ups: A Status-Quo Consideration. [Intentionale vs. emergente Strategien der Online-Kommunikation von Gründungsunternehmen: Eine Status-quo-Betrachtung.]” In Strategische Kommunikation im Spannungsfeld zwischen Intention und Emergenz, 195–213. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Bekmeier-Feuerhahn, S., C. Rudeloff, and U. Adam. 2016. “Communication Management of Start-Ups in the Cultural and Creative Industry: An Empirical Inventory. [Kommunikationsmanagement von Gründungen in der Kultur-und Kreativwirtschaft: Eine empirische Bestandsaufnahme].” ZfKE–Zeitschrift für KMU und Entrepreneurship 64 (1): 21–45.

- Berthon, P., M. T. Ewing, and J. Napoli. 2008. “Brand Management in Small to Medium‐Sized Enterprises.” Journal of Small Business Management 46 (1): 27–45.

- Bresciani, S., and M. J. Eppler. 2010. “Brand New Ventures? Insights on Start-Ups’ Branding Practices.” Journal of Product & Brand Management 19 (5): 356–366.

- Bruhn, M. 2008. “„Communication Policy for Start-Ups.” [Kommunikationspolitik für Gründungsunternehmen].” In Entrepreneurial Marketing: Special Features, Tasks and Solutions for Start-Ups [Entrepreneurial Marketing: Besonderheiten, Aufgaben und Lösungsansätze für Gründungsunternehmen], edited by J. Freiling, and T. Kollmann, 481–502. Wiesbaden: Gabler.

- Carter, N. M., W. B. Gartner, and P. D. Reynolds. 1996. “„Exploring Start-up Event Sequences.” Journal of Business Venturing 11 (3): 151–166.

- Chen, Z. F., Y. G. Ji, and L. R. Men. 2017. “Strategic Use of Social Media for Stakeholder Engagement in Startup Companies in China.” International Journal of Strategic Communication 11 (3): 244–267.

- Comscore 2019. “Top 50 Multi-Platform Properties (Desktop and Mobile)”. Accessed 27 March 2019. https://www.comscore.com/Insights/Rankings

- Cooper, A., M. Ramachandran, and D. Schoorman. 1998. “Time Allocation Patterns of Craftsmen and Administrative Entrepreneurs: Implications for Financial Performance.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 22 (2): 123–136.

- Correa, T., A. W. Hinsley, and H. G. De Zuniga. 2010. “Who Interacts on the Web?: the Intersection of Users’ Personality and Social Media Use.” Computers in Human Behavior 26 (2): 247–253.

- Einwiller, S. A., and M. Boenigk. 2012. “Examining the Link between Integrated Communication Management and Communication Effectiveness in Medium-Sized Enterprises.” Journal of Marketing Communications 18 (5): 335–361.

- Ellison, N. B. 2007. “Social Network Sites: Definition, History, and Scholarship.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 13 (1): 210–230.

- Fombrun, C., and M. Shanley. 1990. “What’s in a Name? Reputation Building and Corporate Strategy.” Academy of Management Journal 33 (2): 233–258.

- Fombrun, C. J., and C. B. Van Riel. 1997. “The Reputational Landscape.” Corporate Reputation Review 1 (1): 5–13.

- Gruber, M. 2004. “Marketing in New Ventures: Theory and Empirical Evidence.” Schmalenbach Business Review 56 (2): 164–199.

- Grunig, J. E. 2006. “Furnishing the Edifice: Ongoing Research on Public Relations as a Strategic Management Function.” Journal of Public Relations Research 18 (2): 151–176.

- Grunig, J. E., and Y. H. Huang. 2000. “„from Organizational Effectiveness to Relationship Indicators: Antecedents of Relationships, Public Relations Strategies, and Relationship Outcomes.” In Public Relations as Relationship Management: A Relational Approach to the Study and Practice of Public Relations, edited by J. A. Ledingham, and S. D. Bruning, 23–53. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Grunig, J. E., and T. T. Hunt. 1984. Managing Public Relations. Fort Worth: Wadsworth.

- Grunig, J. E., and D. M. Dozier (2003). Excellent public relations and effective organizations: A study of communication management in three countries. Routledge.

- Guo, C., and G. D. Saxton. 2014. “Tweeting Social Change: How Social Media Are Changing Nonprofit Advocacy.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 43 (1): 57–79.

- Hallahan, K., D. Holtzhausen, B. Van Ruler, D. Verčič, and K. Sriramesh. 2007. “Defining Strategic Communication.” International Journal of Strategic Communication 1 (1): 3–35.

- Hanks, S. H., and G. Chandler. 1994. “Patterns of Functional Specialization in Emerging High Tech Firms.” Journal of Small Business Management 32 (2): 23–36.

- Hills, G. E., C. M. Hultman, and M. P. Miles. 2008. “The Evolution and Development of Entrepreneurial Marketing.” Journal of Small Business Management 46 (1): 99–112.

- Hoeffler, S., and K. L. Keller. 2003. “The Marketing Advantages of Strong Brands.” Journal of Brand Management 10 (6): 421–445.

- Hormiga, E., R. M. Batista-Canino, and A. Sánchez-Medina. 2011. “The Impact of Relational Capital on the Success of New Business Start-Ups.” Journal of Small Business Management 49 (4): 617–663.

- Hussain, J., F. A. Shah, and ChS. Akhtar. 2016. “Market Orientation and Organizational Performance in Small and Medium Sized Enterprises. A Conceptual Approach.” City University Research Journal 6 (1): 166–180.

- Juntunen, M., S. Saraniemi, M. Halttu, and J. Tähtinen. 2010. “„Corporate Brand Building in Different Stages of Small Business Growth.” Journal of Brand Management 18 (2): 115–133.

- Kadam, A., and S. Ayarekar. 2014. “Impact of Social Media on Entrepreneurship and Entrepreneurial Performance: Special Reference to Small and Medium Scale Enterprises.” SIES Journal of Management 10 (1): 3–11.

- Kane, G., M. Alavi, G. Labianca, and S. Borgatti. 2012. “What’s Different about Social Media Networks? a Framework and Research Agenda.” MIS Quarterly 38 (1): 275–304.

- Kang, M., and M. Sung. 2017. “How Symmetrical Employee Communication Leads to Employee Engagement and Positive Employee Communication Behaviors: The Mediation of Employee-Organization Relationships.” Journal of Communication Management 21 (1): 82–102.

- Kaplan, A. M., and M. Haenlein. 2010. “Users of the World, Unite! The Challenges and Opportunities of Social Media.” Business Horizons 53 (1), 59–68.

- Kazanjian, R. 1988. “Relation of Dominant Problems to Stages of Growth in Technology-Based New Ventures.” Academy of Management Journal 31 (2): 257–279.

- Keller, K. L. 2009. “Building Strong Brands in a Modern Marketing Communications Environment.” Journal of Marketing Communications 15 (2-3): 139–155.

- Lambertz, S., and R. Schulte. 2013. “Consolidation Period in New Ventures: How Long Does It Take to Establish a Start-up?” International Journal of Entrepreneurial Venturing 5 (4): 369–390.

- Laukkanen, T., S. Tuominen, H. Reijonen, and S. Hirvonen. 2016. “„Does Market Orientation Pay off without Brand Orientation? a Study of Small Business Entrepreneurs.” Journal of Marketing Management 32 (7-8): 673–694.

- Ledingham, J. A., and S. D. Bruning. 1998. “Relationship Management in Public Relations: Dimensions of an Organization-Public Relationship.” Public Relations Review 24 (1): 55–65.

- Levie, J., and B. B. Lichtenstein. 2010. “A Terminal Assessment of Stages Theory: Introducing a Dynamic States Approach to Entrepreneurship.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 34 (2): 317–350.

- Lichtenstein, B. M. B., and C. G. Brush. 2001. “„How Do “Resource Bundles” Develop and Change in New Ventures? a Dynamic Model and Longitudinal Exploration.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 25 (3): 37–58.

- Lichtenstein, B., K. Dooley, and G. Lumpkin. 2006. “„Measuring Emergence in the Dynamics of New Venture Creation.” Journal of Business Venturing 21 (2): 153–175.

- Lovejoy, K., and G. D. Saxton. 2012. “Information, Community, and Action: How Nonprofit Organizations Use Social Media.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 17 (3): 337–353.

- Lumpkin, G. T., R. C. Shrader, and G. E. Hills. 1998. “Does Formal Business Planning Enhance the Performance of New Ventures?.” In Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research, edited by P. D. Reynolds, Babson Park, MA: Babson College.

- Macnamara, J. 2014. “Organizational Listening: A Vital Missing Element in Public Communication and the Public Sphere.” Asia Pacific Public Relations Journal 15 (1): 89–108.

- Macnamara, J., and A. Zerfass. 2012. “Social Media Communication in Organizations: The Challenges of Balancing Openness, Strategy, and Management.” International Journal of Strategic Communication 6 (4): 287–308.

- Men, L. R., Y. G. Ji, and Z. F. Chen. 2017. “Dialogues with Entrepreneurs in China: How Start-up Companies Cultivate Relationships with Strategic Publics.” Journal of Public Relations Research 29 (2-3): 90– 113.

- Men, L. R., and W. H. S. Tsai. 2014. “Perceptual, Attitudinal, and Behavioral Outcomes of Organization–Public Engagement on Corporate Social Networking Sites.” Journal of Public Relations Research 26 (5): 417–435.

- Milgrom, P. J., and J. Roberts. 1986. “Price and Advertising Signals of Product Quality.” Journal of Political Economy 94 (4): 796–821.

- Mintzberg, H., and J. A. Waters. 1985. “Of Strategies, Deliberate and Emergent.” Strategic Management Journal 6 (3): 257–272.

- Morgan, N. A., D. W. Vorhies, and C. H. Mason. 2009. “Market Orientation, Marketing Capabilities and Firm Performance.” Strategic Management Journal 30 (8): 909–920.

- Morsing, M., and M. Schultz. 2006. “Corporate Social Responsibility Communication: Stakeholder Information, Response and Involvement Strategies.” Business Ethics: A European Review 15 (4): 323–338.

- Moss, D., R. Ashford, and N. Shani. 2004. “The Forgotten Sector: Uncovering the Role of Public Relations in SMEs.” Journal of Communication Management 8 (2): 197–210.

- Mueller, S., T. Volery, and B. von Siemens. 2012. “What Do Entrepreneurs Actually Do? an Observational Study of Entrepreneurs’ Everyday Behavior in the Start‐up and Growth Stages.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 36 (5): 995–1017.

- Nakara, W. A., F. Z. Benmoussa, and A. Jaouen. 2012. “„Entrepreneurship and Social Media Marketing: Evidence from French Small Business.” International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business 16 (4): 386–405.

- Pakura, S., and A. Pakura. 2015. “The Impact of Entrepreneurs’ Facebook Activity on the Success of Small Firms. An Empirical Study in the German Crafts Business Sector.” Business Administration Review 75 (6): 413–429.

- Perrin, A. 2015. “Social Media Usage 2005-2015.” Pew Research Center 2015 (8): 52–68.

- Petkova, A. P., V. P. Rindova, and A. K. Gupta. 2008. “How Can New Ventures Build Reputation? an Exploratory Study.” Corporate Reputation Review 11 (4): 320–334.

- Qualman, E. 2012. Socialnomics. How Social Media Transforms the Way we Live and Do Business. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, New Jersey.

- Rao, R. S., R. K. Chandy, and J. C. Prabhu. 2008. “The Fruits of Legitimacy: Why Some New Ventures Gain More from Innovation than Other.” Journal of Marketing 72 (4): 58–75.

- Reijonen, H., T. Laukkanen, R. Komppula, and S. Tuominen. 2012. “Are Growing SMEs More Market‐Oriented and Brand‐Oriented?.” Journal of Small Business Management 50 (4): 699–716.

- Rybalko, S., and T. Seltzer. 2010. “Dialogic Communication in 140 Characters or Less: How Fortune 500 Companies Engage Stakeholders Using Twitter.” Public Relations Review 36 (4): 336–341.

- Schivinski, B., and D. Dabrowski. 2016. “The Effect of Social Media Communication on Consumer Perceptions of Brands.” Journal of Marketing Communications 22 (2): 189– 214.

- Shane, S., and D. Cable. 2002. “Network Ties, Reputation, and the Financing of New Ventures.” Management Science 48 (3): 364–381.

- Singh, J. V., D. J. Tucker, and R. J. House. 1986. “Organizational Legitimacy and the Liability of Newness.” Administrative Science Quarterly 31 (2): 171–193.

- Solis, B., and D. K. Breakenridge. 2009. Putting the Public Back in Public Relations: How Social Media is Reinventing the Aging Business of PR. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Ft Press.

- Stinchcombe, A. L., and J. G. March. 1965. “Social Structure and Organizations.” In Handbook of Organizations, edited by J. P. March, 142–193. Chicago: Rand McNally.

- Stokes, D. 2000. “Putting Entrepreneurship into Marketing: The Processes of Entrepreneurial Marketing.” Journal of Research in Marketing and Entrepreneurship 2 (1): 1–16.

- Van Stel, A., M. Carree, and R. Thurik. 2005. “The Effect of Entrepreneurial Activity on National Economic Growth.” Small Business Economics 24 (3): 311–321.

- Vercic, D., and A. Zerfass. 2016. “A Comparative Excellence Framework for Communication Management.” Journal of Communication Management 20 (4): 270–288.

- Vernuccio, M. 2014. “Communicating Corporate Brands through Social Media: An Exploratory Study.” International Journal of Business Communication 51 (3): 211–233.

- Welter, F., and D. Smallbone. 2006. “Exploring the Role of Trust in Entrepreneurial Activity.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 30 (4): 465–475.

- Witt, P., and V. Rode 2005. “Corporate brand building in start-ups.” Journal of Enterprising Culture 13 (3): 273–294.

- Zerfass, A. 2008. “Corporate Communication Revisited: Integrating Business Strategy and Strategic Communication.” In Public Relations Research. European and International Perspectives and Innovations, edited by A. Zerfass, B. van Ruler, and K. Sriramesh, 65–96. Wiesbaden: Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften (VS).

- Zerfass, A. 2010. Coporate Governance and Public Relations: Foundation of Corporate Communication Theory and Public Relations [Unternehmensführung und Öffentlichkeitsarbeit: Grundlegung einer Theorie der Unternehmenskommunikation und Public Relations, 3rd ed., Wiesbaden: Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften (VS).

- Zerfass, A., A. Moreno, R. Tench, D. Verčič, and P. Verhoeven. 2007. European Communication Monitor 2007. Trends in Communication Management and Public Relations–Results and Implications. Leipzig: University of Leipzig/EUPRERA.

- Zerfass, A., and C. Viertmann. 2017. “„Creating Business Value through Corporate Communication: A Theory-Based Framework and Its Practical Application.” Journal of Communication Management 21 (1): 68–81.