Abstract

This paper focuses on place-based entrepreneurs as regionally anchored companies that rely on regional resources to generate a sustained competitive advantage, but are increasingly challenged by a seemingly placeless and highly-globalized marketplace. Although there are numerous cases of successful place-based entrepreneurs, the role of place for their competitiveness is an understudied research field. This paper presents an illustrative case study to explore the competitive advantage of small regional banks from Germany, which are prototypical place-based entrepreneurs that successfully compete in the market, but meet important external challenges. By focusing on a relational perspective on the idiosyncratic co-operative relationships of the banks with regional SMEs, the paper finds that the place-based entrepreneurship of the small regional banks is determined by the interplay of static/dynamic proximities in the relationships, which leads to their strength and resilience. These relational and proximity-based benefits result in a strategy of investments by the banks in the relationships with regional SMEs, and the investments, in turn, support the building of a strong regional identity that is shared with the banks and their customers.

RÉSUMÉ

Cet article se concentre sur les entrepreneurs locaux en tant qu’entreprises ancrées qui dépendent des ressources régionales pour générer un avantage concurrentiel durable, mais qui sont de plus en plus confrontées à un marché apparemment sans localisation et fortement mondialisé. Bien qu’il existe de nombreux cas de réussite d’entrepreneurs basés sur le lieu, le rôle du lieu pour leur compétitivité est un domaine de recherche sous-étudié. Cet article présente une étude de cas illustrative pour explorer l’avantage concurrentiel des petites banques régionales d’Allemagne, qui sont des prototypes d’entrepreneurs locaux qui rivalisent avec succès sur le marché, mais sont confrontés à des défis externes importants. En se concentrant sur une perspective relationnelle sur les relations de coopération idiosyncrasiques des banques avec les PME régionales, l’article révèle que l’entrepreneuriat territorial des petites banques régionales est déterminé par l’interaction des proximités statiques/dynamiques dans ces relations, ce qui conduit à leur force et à leur résilience. Ces avantages relationnels et de proximité se traduisent par une stratégie d’investissement des banques dans les relations avec les PME régionales, et en retour, ces investissements soutiennent la construction d’une identité régionale forte qui est partagée avec les banques et leurs clients.

1. Introduction

Place-based entrepreneurs are challenged in today’s seemingly placeless marketplace even though their business model might prove to be a source of sustained competitiveness (Dybdahl Citation2019; Vlasov et al. Citation2018). Small regional banks in countries like Italy or Germany are prototypical place-based entrepreneurs with their century-long tradition of business operations within a limited regional market area and their role as core financial partners of notably SMEs (Sellar Citation2015; Fiordelisi and Mare Citation2014; Mercieca et al. Citation2007; Usai and Vannini Citation2005). In spite of its practical relevance, such place-based entrepreneurship represents an understudied topic in the entrepreneurship and small business management literature with only a few publications addressing it (Bollweg et al. Citation2020; Hakenes et al. Citation2015; Howorth and Moro Citation2006). Notably the role of place as either a competitiveness factor for or threat to the competitive advantage of such entrepreneurs in the trade-off between a regional and global market challenges has not been thoroughly explored, resulting in a lack of knowledge on the inter-relationship of place and competitiveness. For small regional banks, Ughetto et al. (Citation2019, 617) illustrate this lack of knowledge as follows: “little is known about how recipient regional economies are affected by changes in the traditional bank-SME relationship, in the banking system (Basel II and III) and in the financial markets”.

Motivated by this evident gap in the literature, the present paper explores how place-based entrepreneurs such as small regional banks actually use place to generate a sustained competitive advantage. To this aim, the paper focuses on the tight, and place-dependent, relationships of the banks with regional SMEs (cf. Koetter et al. Citation2020). Based on a literature review and research propositions, which are derived from the literature, an illustrative case study from German public-sector saving banks (Sparkassen) and mutual savings-cooperative banks (Genossenschaftsbanken) is presented. These banks hold long-term collaborative relationships with regional SMEs and have their headquarters at short distance from these customers (Flögel and Gärtner Citation2018), both of which qualifies them as prototypical place-based entrepreneurs.

The paper finds that the place-based entrepreneurship of the small regional banks is facilitated by the interplay of their established relationship banking with regional SMEs and spatial/a-spatial proximities, acting in this relationship. Jointly, these elements generate high levels of regional engagement on the part of the banks, which, in turn, materializes as investments in their network interaction with regional SMEs and other stakeholders (companies, public actors, etc.) and contributes to the building of a shared regional identity among the banks and SMEs.

With these findings, the paper contributes to the small business management and entrepreneurship literature in the following ways: First, it adds to the extant empirical research on proximities in inter-firm business relationships, which, however, mainly focuses on innovation collaboration (Balland et al. Citation2015; Ben Letaifa and Rabeau Citation2013), by illustrating the importance of notably dynamic proximities for co-operative relationships outside the innovation field. Second, the finding of the inter-related spatial and a-spatial proximities with bank-SME relationships amends the established “stylized facts” on relationship banking (Boot Citation2000; Elsas and Krahnen Citation1998) with a place-based component. Third, the paper demonstrates how regional identity is expressed and built by place-based entrepreneurs through regional engagement (Bürcher Citation2017; Jussila et al. Citation2007) and how it is used as a competitiveness factor in a regional markt. Finally, because the co-operative relationships between the small regional banks and regional SMEs strengthen the competitive advantage of the banks, the paper also contributes to the extant research on SME-related business co-operation and competitiveness issues (cf. Wincent Citation2005).

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The next two sections present the context and a literature overview, including the research propositions. The following section describes the methodology and research design, followed by the empirical results. The final sections, first, discuss the findings and, subsequently, present the main conclusions, the limitations to the study and a brief outlook on future research avenues.

2 The context: small regional banks in Germany

2.1. Small regional banks in the German banking system

Regional banks such as public-sector banks and mutual savings-cooperative banks, which individually are small companies (), are an integral part of Germany’s “three-pillar” banking system (Höwer Citation2016; Hüfner Citation2010; ); they co-exist along private commercial banks and other specialized banks and are equally distributed across the country. This is an important difference to notably the private commercial banks, which are concentrated in selected headquarter locations (e.g., Frankfurt am Main) but serve the whole German market and, hence, compete with the regional banks in their small-scale market areas (Hakenes et al. Citation2015).

Table 1. Size of the small regional banks in Germany (data from 2018).

Table 2. Structure of the German banking market (data from 2017, n.i. data not indicated).

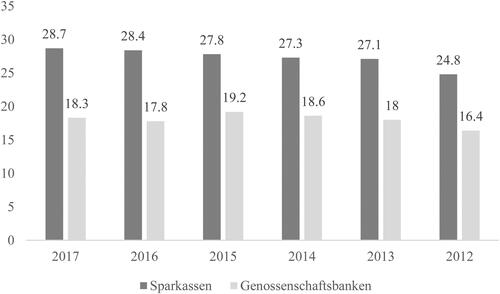

On the aggregate level, the regional banks in Germany account for a large market share and have been market leaders in corporate lending over the past few years (). In 2017, the German banking market had a total volume of EUR 7,066 billion, of which public-sector savings banks accounted for 17.0 per cent and mutual savings-cooperative banks for 12.6 per cent (Deutscher Sparkassen- und Giroverband e.V. Citation2018). Public-sector savings banks also hold 32.6 per cent of all branches, followed by mutual savings-cooperative banks with 31.3 per cent and private commercial banks with 29.9 per cent (Deutsche Bundesbank Citation2018). Moreover, both types of regional banks demonstrate a higher equity compared to the other bank types in Germany and generate higher returns on equity, which indicates their stability ().

Figure 1. Market shares of German regional banks in corporate lending (2012–2017). Source: Finanzberichte Sparkassen-Finanzverbund 2013-2018. Deutscher Sparkassenund Giroverband e.V., Berlin.

Historically, the existence of regional banks in Germany is explained by the “regional principle”, which represents a formal or traditional norm to restrict business operations of the banks (with all branches) to a specific market area. The principle still accounts for the operations in and strategic focus of the banks on regional markets (Gärtner and Flögel Citation2013). Public-sector savings banks have to follow the principle as a legally binding rule (Schrumpf and Müller Citation2001) because they are owned by municipalities (Höwer Citation2016; Flögel and Gärtner Citation2016). Hence, their market area corresponds to the geographical scale of their principal shareholder (Scheike Citation2004), and their operations are based on the legal mandate to provide customers in the region with financial services (Schrumpf and Müller Citation2001). Mutual savings-cooperative banks, however, are owned by private shareholders, who are organized in co-operatives (Höwer Citation2016). Their regional focus is derived from their traditional understanding as regional co-operatives (Raab-Kratzmeier Citation2014; Schrumpf and Müller Citation2001).

2.2. The place-based model of small regional banks in Germany

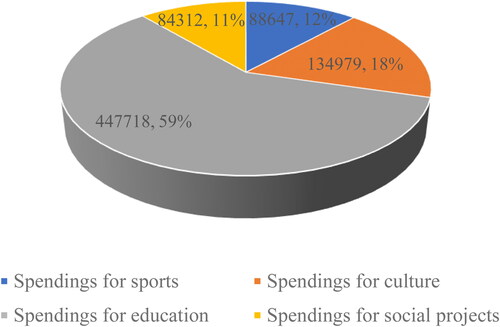

Because of their overall regional operations, both public-sector savings banks and mutual savings-cooperative banks possess a place-based business model. However, its sustainability is heavily dependent on the growth of the regional economy. If the regional economy faces stress, for example, because of a loss of the competitiveness of established industries and lay-offs, regional banks need to sustain their competitiveness despite this stress by developing this small-scale regional market (Usai and Vannini Citation2005) because opportunities for market expansions and internationalization are very limited. Hence, they have an intrinsic interest to promote regional growth strategies through various activities beyond corporate lending (Hakenes et al. Citation2015), for example, through the development of new industrial sites on behalf of municipalities, public-private partnerships with municipalities for business development, and investments in technology promotion and business incubation centers (cf. Sunley et al. Citation2005). The activities of regional banks to lobby and influence regional policies in Germany typically encompass, for instance, investments in social and cultural projects through sponsoring and charity ().

Figure 2. Sponsoring activities by German public-sector saving banks (Sparkassen) in 2017 and 1.000 EUR. Source: Deutscher Sparkassen- und Giroverband e.V., Bericht an die Gesellschaft 2017.

Nevertheless, these small regional banks face huge competitiveness challenges in the global business environment and, more recently, due to digitization and its ubiquitous effects on financial services. A major challenge is associated with the ongoing centralization and concentration of financial service provision in urban regions, a trend that generally favors large private commercial banks using economies of scale (Wójcik and MacDonald-Korth Citation2015). This centralization raises the level of competition in the market areas where the regional banks operate (Mercieca et al. Citation2009). To generate efficiency gains, the German public-sector saving banks have recently begun to merge into larger units and streamline their operations (Gärtner and Flögel Citation2017). The resulting fierce competition, along with the second trend of more digitally available financial services, endangers the proximity-based business model of the small regional banks, notably their decentral and customized approach to loan decisions (Conrad et al. Citation2018; Gärtner and Flögel Citation2017). Furthermore, national and supra-national (European Union) politics – the latter aiming at the privatization of publicly-owned banks – imply major regulatory changes such as an increasingly standardized loan-granting process, which is enforced by the legal frameworks of Basel II and Basel III in the European Union (Seikel Citation2017). Jointly, these challenges threaten the place-dependent operations of small regional banks, which is the motivation to explore their sustained competitiveness in this context.

3. Literature review

3.1. The concept of place-based entrepreneurship

Feldman’s (Citation2001) observation that entrepreneurial activities are mostly a regional phenomenon lays the ground for place-based entrepreneurship. In a broad understanding, which is followed in this paper, place-based entrepreneurship is associated with the use of regionally-provided resources by companies for learning and upgrading processes (Moriggi Citation2020; Cantino et al. Citation2017) as well as the place embeddedness of companies (McKeever et al. Citation2015). Both ideas are reflected in the argument proposed by Vlasov et al. (Citation2018) and Cantino et al. (Citation2017) that the place-specific inter-firm business co-operation respectively network relationships constitute the place embeddedness of such entrepreneurs.

Hence, in the context of small regional banks, which this paper addresses, place-based entrepreneurship is conceptualized from a relational perspective. Place-based entrepreneurs are, thus, incumbent small regional banks, which are dependent on relationships provided within the region, for example, through customers, suppliers, co-operation partners and policy actors, on the one hand, whilst actively developing these relationships themselves, on the other (cf. Bürcher and Habersetzer Citation2016). Hence, the strong interdependency between small regional banks and regional SMEs as well as their geographical proximity implies that the transactions managed in the relationships are embedded not only in the relationships themselves, but also in the region in which banks and SMEs are located.

3.2. Relationship banking and housebank relationship

Furthermore, the embeddedness of transactions in the relationships between small regional banks (as lenders) and their SME customers (as borrowers) is reflected in the concept of “relationship lending” (Elyasiani and Goldberg Citation2004), which is also described as “relationship banking” (Boot Citation2000) and the “housebank relationship” (Elsas and Krahnen Citation1998).

The three concepts jointly emphasise the long-term co-operative character of the relationship (Elsas and Krahnen Citation1998; Berger and Udell Citation1995), with the so-called housebank considered as the main lender to and, hence, key financial partner of the company (Behr and Güttler Citation2007). The transactions, which are embedded in the relationship, are multi-dimensional but corporate lending typically represents the main transaction (Uzzi Citation1999). The relationship provides the housebank with informational advantages, which goes at the expense of the company because the bank receives implicit, private and complex information about it (Moro et al. Citation2012). Another important element is the trust that typically builds over time and leads to more advantageous lending conditions for the company as the relationship becomes more long-termed. This accounts for the label of the concept as “relationship lending” (Elyasiani and Goldberg Citation2004), and it also explains the stability of the housebank relationship.

Therefore, with relationship lending or, more broadly speaking, relationship banking, the loan-grant decisions of the banks are supported by the relationship to the companies, which alleviates information asymmetries between the co-operation partners over time and provides the bank with abundant information, including tacit knowledge (Berger and Udell Citation2006; Boot Citation2000; Berger and Udell Citation1995). Other informational advantages are explained by the low monitoring costs of the borrower because of the evolving trust between borrower and lender and their mutual reputational gains in the course of time (Baas and Schrooten Citation2006). Therefore, relationship banking leads to more favorable credit conditions for the borrowing company over time, reduces the transaction costs and risks for the lending bank, and increases the value of the relationship for both contractual partners (Boot Citation2000; Bornheim and Herbeck Citation1998).

The concept of the housebank relationship with relationship banking applies specifically to SMEs with their tight and long-term bank relationships (Neuberger and Räthke Citation2009; Baas and Schrooten 2006). Such relationships tend to be persistent; for example, Elsas (Citation2005) shows that an increase in market competition strengthens the housebank relationships. Moreover, the global financial and economic crisis in the past decade has given proof that stable housebank relationships are beneficial to companies because housebanks are more open, in such situations, to loan granting than other types of banks (Ughetto et al. Citation2019; Hasan et al. Citation2019; Gärtner Citation2009).

3.3. Spatial and a-spatial proximities in the relationship

Despite the advantages highlighted, place itself is not indicated as an element of relationship banking (cf. Dass and Massa Citation2011; Elsas 2005). Therefore, the proximities approach, which will be applied to inter-firm business co-operation in this paper, provides a more fine-grained understanding of the role of place for such relationships (Torre and Wallet Citation2014). The concept includes various proximities, spatial and a-spatial ones (cf. Knoben and Oerlemans Citation2006).

A central term is physical proximity, defined as the geographical distance between companies (Boschma Citation2005), which influences the level of transaction costs and determines the degree to which companies exchange knowledge, notably through face-to-face communication. Concerning the relationship between small regional banks and regional SMEs, physical proximity represents a lever for the banks to reduce the costs of acquiring information on borrowers in the necessary quantity and quality. For the context studied, the decision-making about loan grants with public-sector savings banks and mutual savings-cooperative banks is organised decentrally and takes place in spatial proximity to their customers (cf. Deeg Citation1998). This model allows the bank consultants to pass on tacit, non-codified information about customers (for example, planned investments and business decisions) to the headquarters inside the region. Such information cannot be retrieved from the balance sheets and on the company books. This is a notable difference to the business model of large commercial banks with branches inside, but headquarters outside, the region, where a complex internal hierarchy and physical distance need to be surmounted between the consultant in the regional branch to the central committee when deciding about loan grants. The more hierarchical structure with large banks does not encourage the bank consultants to report notably the non-codified information about borrowers (cf. Stein Citation2002).

The empirical literature on physical proximity with bank relations is scarce; only Degryse and Ongena (Citation2005) show that the low geographical distance between banks and their corporate customers reduces asymmetric information. According to Boschma (Citation2005), physical proximity, however, does not necessarily influence by itself the exchange of resources and knowledge in co-operative relationships but rather represents a facilitator that intensifies other a-spatial proximities acting in the relationships. Hence, social proximity is another proximity that matters for the relationship between regional banks and SMEs. It builds on the social relationships between persons (Knoben and Oerlemans Citation2006) and is amplified by trust, friendship and kinship, or shared experience (cf. Boschma Citation2005). The effects of social proximity depend largely on the context (Boschma Citation2005): A high degree of social proximity can strengthen business co-operation, but overly strong relations can also lead to wrong decisions or involve nepotism in the relationships. Vice-versa, a low degree of social proximity can disturb and even hinder transactions when these relationships are not trustful enough or lack substantial personal interaction.

Cognitive proximity represents a third relevant proximityFootnote1, which is defined as the ability to absorb and process knowledge (Boschma Citation2005). To generate cognitive proximity, companies involved in co-operative business relationships need to possess similar communication modes (Molina-Morales et al. Citation2015; Knoben and Oerlemans Citation2006). For the relationship addressed here, a high degree of cognitive proximity is necessary because the transactions between banks and companies are based on codified and non-codified information. Cognitive proximity can support the bank’s ability to absorb, decode and process such information and develop it into valuable knowledge about the SME. However, a high level of cognitive proximity can also disturb learning processes (Huber Citation2012) if bank and companies are cognitively too close to each other.

The relation between these three proximities from a static perspective is not perfectly clear. Fitjar and Rodríguez‐Pose (2017), Crescenzi et al. (Citation2016), and Balland et al. (Citation2015) suggest that physical proximity is less important for co-operative relationships than other proximities. However, according to Paci et al. (Citation2014), Rychen and Zimmermann (Citation2008), and Boschma (2005), both social and cognitive proximity can be facilitated by physical proximity. More specifically, Agrawal et al. (Citation2008) and Ben Letaifa and Rabeau (Citation2013) claim that physical and social proximity substitute each other whereas Hansen (Citation2015) finds that physical proximity can be either a facilitator of or substitute for social proximity. Finally, Mattes (Citation2012) regards social and physical proximity just as auxiliary proximities that can facilitate cognitive proximity.

Taken together, the literature suggests that physical and social proximity are either complements or substitutes in inter-firm business co-operation, whereas physical proximity is considered as a complement of cognitive proximity (Ben Letaifa and Rabeau Citation2013). However, the empirical evidence is thin, which requires further assumptions about the proximity relations for the relationship of small regional banks and SMEs:

The physical proximity of bank and company will have a positive effect on their social proximity because of the informational advantages provided over short distances and by flat hierarchies.

Various transactions are managed simultaneously in the relationship and may require different levels of physical proximity. Standardized financial services such as current account transactions require only a low degree of physical presence and can easily be replaced by online services. By contrast, complex transactions such as investment loan decisions cannot be standardized to the same extent and require higher levels of physical proximity to find a customized solution. A substitution of physical through online service provision may adversely affect them.

For cognitive proximity between regional banks and SMEs, it can be assumed that both physical and social proximity facilitate the communication and instigate learning processes between them, for example, when banks are dealing with new demands by SMEs.

These ideas find partial support in the literature. Petersen and Rajan (Citation2002) show that US companies choose more distant banks and less personalized communication. However, Neuberger and Räthke (Citation2001) rather highlight that micro-enterprises in Germany prefer both electronically provided and personal financial services.

A further complexity to the missing evidence is the observation that the proximity categories are both influencing and influenced by the actual amount of interaction in the relationship (Balland et al. Citation2015). This argument has two consequences for the relationship between regional banks and SMEs: First, regular and continuous interactions taking place in the relationship (based on physical-social proximity) will most likely generate high levels of cognitive proximity (Balland et al. Citation2015), with banks learning about their customers and SMEs about the banks over time. Second, the interactions also change the relation of physical, social and cognitive proximities (Menzel Citation2015), and these changes influence themselves the interaction between bank and company in complex ways. Therefore, the spatial and a-spatial proximities acting in the relationship of bank and companies are subject to change over time, and their dynamic relations (e.g., physical-social proximity) may also change as the relationship continues.

3.4. Regional engagement and identity through relationships

The observation that small regional banks engage for the region they are located in and that this engagement is not limited to the provision of financial services, but includes, for example, sponsoring and charity activities (), is in line with the common understanding of corporate social responsibility. Corporate social responsibility is often found with SMEs (Pahnke and Welter Citation2019) and defined as the pressure on entrepreneurs of “holding companies to account for the social consequences of their activities” (Porter and Kramer Citation2006, 78). While this concept reflects a reactive behavior on the part of companies, Jussila et al. (Citation2007, 36) define corporate regional responsibility as a proactive strategy to influence regions as “firms’ active participation in regional strategy processes, L&RED initiatives and regional philanthropy”. Hence, corporate social responsibility is associated with the commitment of companies beyond basic business operations in a given region such as the lobbying for and participation in policy initiatives, and it is part of the understanding of companies as regional players.

A related idea is corporate regional engagement, which Bürcher (Citation2017, 694) describes as “personal engagement of decision-makers of firms that can be based on a feeling of responsibility vis-à-vis the region” and that results in high levels of regional social capital (cf. McKeever et al. Citation2015). Bürcher (Citation2017) shows that such regional engagement is more than the production and sales of goods and services in a specific region because it leads to the formation of a regional identity (cf. Raagmaa Citation2002). This argument is supported by the empirical literature: Berglund et al. (Citation2016) show the link between identity-formation and regions for entrepreneurs. More specifically, Gill and Larson (Citation2014) demonstrate how place-based identity intermingles with identity works of entrepreneurs to build a strong entrepreneurial mindset that is attached to a specific location. Finally, Markowska and Lopez-Vega (Citation2018) highlight how entrepreneurs use such a regional identity for the narratives they build around their business, which shows how regional identity may materialize through actions and behavior of entrepreneurs.

3.5. Research propositions

From the literature, it can be derived that the housebank relationship represents a basic competitiveness factor of the small regional banks because it accounts for a persistent, long-term co-operation with regional SMEs due to trust, reputation-building and informational advantages (Elyasiani and Goldberg Citation2004; Bornheim and Herbeck Citation1998). Moreover, the interplay of physical (spatial) and social and cognitive (a-spatial) proximities acting in the housebank relationship (cf. Boschma Citation2005) reinforces the basic advantages that the housebank relationship provides to the banks, which results in place-based relationship banking. This leads to the following research proposition.

Research proposition 1: The competitive advantage for small regional banks as place-based entrepreneurs results from the established housebank relationship with regional SMEs and its amplification by spatial and a-spatial proximities in the relationship.

Furthermore, because of the proximities in the relationship, the literature suggests that the relationship between regional banks and their corporate customers such as SMEs is regionally embedded beyond the business operations of the banks. The place embeddedness, thus, creates relational benefits for the banks from their housebank relationship, which are further amplified through the banks’ engagement for the region, including the promotion of regional economic growth strategies (cf. Bürcher Citation2017; Jussila et al. 2007).

Research proposition 2: The competitive advantage for small regional banks as place-based entrepreneurs results from the established housebank relationship with regional SMEs and its amplification by the banks’ regional engagement.

4. Methodology, research design, data collection and analysis

Empirically, the present paper is based on a qualitative, inductive research approach according to the grounded theory paradigm (Strauss and Corbin Citation1997). Accordingly, the empirical fieldwork was organized as a process to generate insights into the topic inductively and iteratively, and the whole research process was structured in line with building-blocks recommended for empirical fieldwork in accordance with the grounded theory paradigm (O’Reilly et al. Citation2012).

A first stage of the fieldwork (2015-2016) focused on developing ideas about theoretical categories and paying attention to the requirement of the constant comparison of empirical findings with theoretical considerations. The fieldwork was accompanied by a literature review that summarized key ideas from the literature and compared them with the empirical results. A subsequent stage (2016) targeted the reflection, writing and narrowing down of theories for the topic under investigation, based on an analysis of the information collected and the insights gained from the literature review. A third fieldwork stage (2016-2017) refined the categories and codes created in the first stage of empirical fieldwork, and a fourth stage in the research process (2017-2018) finally established the coding scheme () underlying this paper and juxtaposed the finished coded empirical material and theories. Moreover, research propositions were established in this stage of the research process.

Table 3. Coding guideline for the grounded theory research process.

For the empirical research design, purposive sampling was applied (Miles et al. Citation2018), which resulted in a multiple case study approach that follows the recommendations for qualitative case-study settings provided by Yin (Citation2018), Eisenhardt and Graebner (Citation2007), and Eisenhardt (1989). Concerning the research design used for the case study, the aim was to collect enough evidence to reach empirical saturation, support theory-building and establish a rigorous case-study setting (cf. Gioia et al. 2013; Guest et al. 2006).

Following these goals, the case-study sample consists of a total of 12 in-depth interviews held either personally or by phone with key stakeholders from three groups ( and ): (i) managers from small regional banks from Southern Germany (the Federal States of Bayern and Baden-Württemberg); (ii) managers in associated banking associations (for example, the Association of Public-Sector Savings Banks); and (iii) managers from external expert organizations with connections to the small regional banks (e.g., regional chambers of commerce and chambers of craft). Whereas the interviews with group (i) had the goal of investigating the specific interaction between the banks and SMEs from the perspective of the banks, the interviews with groups (ii) and (iii) aimed at gaining additional insights from stakeholders residing outside this relationship, and, hence, at controlling the information provided by group (i).

Table 4. Interview design with regional banks (group i).

Table 5. Interview design with external stakeholders (groups ii and iii).

The analysis of the material collected through the interviews applied the method of cross-case comparison (Eisenhardt 1989). With regard to coding and data interpretation, an open coding technique was used in line with the principal tenets of grounded theory (Strauss and Corbin Citation1997; O’Reilly et al. Citation2012; cf. Saldaña Citation2016). It enabled an open and contextualized, yet theoretically grounded, interpretation of the categories derived in the early stages of the research process but also allowed their refinement in later stages. These categories were checked and, if necessary, refined using examples from the transcripts, which were condensed into manifestations of the categories. The interpretation of the coded empirical findings was, moreover, closely aligned to the theoretical insights gained from the literature review. Attention was paid to a potential bias stemming from different assessments of “real-life” phenomena on the part of the actors interviewed from regional banks versus outside regional banks. in the appendix gives a detailed overview of how the interpretation with the data analysis was performed, based on the coding scheme from the grounded-theory approach used, and how manifestations were established from key aspects associated with the concepts discussed in the literature review.

Table A1. Key aspects related to small regional banks as place-based entrepreneurs according to the literature and based on the coding and empirical analysis.

With this setting, the empirical study does not aim to establish causal relationships that are statistically representative (Gioia et al. Citation2013; Siggelkow Citation2007). Instead, the primary goal is to benefit from the expert knowledge of the interviewees selected and interpret their explanations by considering theoretical arguments about the relationship studied here. All interviewees were identified via snowballing techniques, and, because of this, but also given the grounded-theory approach chosen, the 12 interviews were iteratively conducted during the research process (2015-2017).

5. Empirical analysis

Research proposition 1: Competitive advantage for small regional banks based on proximities in the housebank relationship.

To start with, all interviewees confirm that the relationship between the small regional banks and SMEs covered in the sample represents a prototypical housebank relationship, whose core is “a very tight, personal and trustful contact between the bank consultant and the business owner, which is being established over the years” (Regional bank A) and that “has a long-term character and is stable and resilient over time, also in difficult times” (Banking association J). Through the trustful, highly personalized relationship between bank consultant and owner or managing-director in a company, the bank is committed to relationship banking. It receives “soft” and non-codified information, which is provided, e.g., through company visits and personal meetings, as well as codified facts from the customers (such as balance sheets). This mix of information provided on the company’s credibility through the relationship facilitates quick yet informed decision-making and generates informational advantages for the bank, as one interviewee points to as follows: “often the bank has more information about the situation of a company than the company itself” (Chamber of Crafts L). Another important insight is that this relationship is, in fact, exclusive in its value for both parties, and personal bank consultants for the SMEs are the key lever to maintain the value of the relationship over time. Even a longer break in the contact between bank consultant and company representative does not imply its breach because the high levels of trust and exclusivity keep the relationship stable.

Moreover, the interviews highlight that the relationship between regional banks and SMEs is determined by proximity, which SMEs understand both as physical and social proximity with the bank consultant, as the following statement describes:

Two things have always been extremely important to all our corporate customers: First, the geographical closeness. That the customer knows I just need to go around the corner and there is my bank. Second, it is the personal contact. The latter can be organized as a digital bank service via e-mail, app or chat, whatever. (Regional bank D)

The amalgam of physical and social proximity is described by the key informants from banks B and D as the feeling of “being present in the minds of the entrepreneurs”.

In addition, cognitive proximity is generated through repeated personal communication; it helps creating a joint understanding of the demands that SMEs have but also reflects the learning process on the part of banks about these demands through the ongoing communication. Cognitive proximity overlaps with the physical and social proximity, because “the most important thing is that the bank and the customer talk to each other… and face-to-face communication is paramount in the bank-customer relationship” (Banking association L).

However, the interviewees stress that the importance of the proximities is changing because physical proximity decreases and social and cognitive proximity is gaining in importance due to external factors (such as the digitization of banking operations, tougher requirements for standardization of financial services, and the fiercer competition within the banking sector). However, the relationship between regional banks and SMEs is not automatically harmed by a loss of physical proximity because the banks manage to replace physically provided standardized services by online services, whilst simultaneously maintaining the physical provision for high-end, less standardized and more customized, services.

With this shift, the banks meet the sophisticated demands of companies by offering a differentiated service package with personalized services at the top of the pyramid that is embedded in a multi-channel communication and distribution strategy. Altogether, the banks exchange physical for social proximity, but maintain the same level of service quality and intensity despite a higher proportion of less personalized online services. To implement this strategy, the personal contact with the bank consultants is paramount, as is stressed as follows: “we estimate that we will have more channels to communicate with the owners and managers of companies in the region, but that their personal bank consultants will always be the same” (Regional bank F). Therefore, such a strategy includes the concept of the “travelling” bank consultant who drives out to the facilities of the companies and initiates regular personal meetings.

However, this strategy of exchanging social for physical proximity faces two important limitations. First, in order to generate high levels of social proximity, the banks need to invest heavily in the high-end, non-standardized services, which they need to carefully judge given resource limitations compared to large banks. Importantly, fluctuations of the staff in the bank or ownership changes with companies trigger a transition period of new trust-building and reciprocal investments of the banks respectively companies. Such changes might lead to breaches in the highly personalized relationships. To prevent this, the regional banks proactively seek to extend the housebank relationship to the new entrepreneurial persons in companies, for example, the new generation of owners or external managers, and develop the management of family succession as an emerging market segment, which fits into the portfolio of high-end, customized services they offer.

Second, the policy requirements for credit standardization push back the personal element in the housebank relationship and endangers the viability of the proximities-based relationship. The interviewees confirm this threat since bank-specific calculation models are gradually superseding the personal, individual decision-making given high pressures on banks to legitimize their loan decisions against the Basel regulations. Notwithstanding this, regional banks maintain their flexibility to decide in cases where the calculation model and personal assessment collide, as they state.

Research proposition 2: Competitive advantage for small regional banks based on regional engagement through the housebank relationship.

The regional banks use regional engagement as a strategy in their consulting approach with regional SMEs to convey a sense of regional identity to them, as the interviewee of regional bank B states: “If you are coming from the region and you are working in the region, you convey to the customer a sense that regional economic cycles matter for you”. This approach provides the bank with a strategic advantage over other banks with this customer segment that values regional identity high. Moreover, the banks proactively support the regional economy, either directly through investments, taxes, job creations and donations, or indirectly through investments in regional business contacts and relationships, as the following statements highlight:

When we built our new head office, we gave 80 per cent of the orders to regional construction and craft firms. (Regional bank D) and Our bank is one of the biggest donors in the region with approximately 150,000 EUR that we donate per year for social, cultural and sports events in the region. (Regional bank C)

This financial and non-financial support and the regional identity are inter-connected because the banks invest in their relationships with SMEs (and private customers as well as other stakeholders, for instance, policy actors), which, again, stabilizes the relationships and allows the banks to keep their customized approach. Their regional engagement, based on relationship banking, pays off because it helps the banks to achieve regional market leader positions and maintain a competitive advantage over private commercial banks, as the following statement suggests:

Regional banks are small banks, but they consider themselves as strong partners of small enterprises, those companies we have in this region. Because of this strategy, they are strong and make it hard for other house banks – large banks – to gain market shares with particularly the small enterprises. (Chamber of Crafts L)

6. Discussion

Regarding research proposition 1, the illustrative case study shows that the housebank relationship respectively relationship banking (Elyasiani and Goldberg Citation2004; Boot Citation2000; Bornheim and Herbeck Citation1998) between the small regional banks and regional SMEs is amplified by the interplay of physical, social and cognitive proximities (Boschma Citation2005). Due to physical and social proximities between the business partners, the banks maintain their non-standardized, personalized consulting, including real-time analysis and decision-making. This approach stabilizes the evolving trust between the key persons in the relationship – personal bank consultants and owners/owner-managers –, even in troubled times. The fact that trust is an outcome of relationship banking is confirmed for Italian start-up entrepreneurs (Howorth and Moro, Citation2006). Moreover, these findings from this case study are in line with Degryse et al. (Citation2017), who show that relationship banking is associated with better credit conditions for SMEs, notably in the post-2007/2008 crisis times.

Beyond confirming the established findings from empirical studies, the present case study provides further evidence that the co-location of banks and SMEs (physical proximity) within the market area is closely intertwined with the intensive and stable social interaction between the key persons from their organisations, that is, owner-manager and bank consultant (social proximity). Moreover, the case study shows that this interaction is embedded in an effective communication (cognitive proximity). Both the physical-social proximity relation as well as the physical-social-cognitive proximity relation amplify the informational advantages that the banks gain from relationship banking with regional SMEs.

Since the relations between the proximities are, however, themselves subject to change following influences from globalization, digitization, and national and supranational policymaking and regulatory requirements, the importance of physical proximity is decreasing while social and cognitive proximities are relatively increasing in importance with the housebank relationship. Because of this, the regional banks face rising transactions costs due to higher investments in relationship banking to compensate for this change. However, the regional banks avoid to become alienated from the regional SMEs. This is a direct result of the smallness of their regional markets which forces them to continuously develop tight relationships with customers in spite of the surrounding market conditions. Partly, this is also the outcome of a proactive strategic move towards a portfolio diversification with more emphasis on high-end, customized consulting and individual risk assessment of companies, which places standardized and online services on the lower end of the portfolio. This differentiation strategy enables the small regional banks to consider the individual context of SMEs irrespective of a loss of physical proximity and take advantage of the tight housebank relationship to continue to provide value to regional SMEs. Altogether, the case study shows that the dynamic relations of proximities help the small regional banks maintaining their housebank model even in challenged times. Partly, this finding is reflected in the empirical literature on dynamic proximities (for example, Huber, Citation2012), but this literature is mostly studying innovation co-operation (as an example, Steinmo and Rasmussen, Citation2016).

With regard to research proposition 2, an important finding is that it is these dynamic proximity relations which also strengthen the regional embeddedness of the housebank relationship in spite of the rising competition and a more anynomous market. Generally, both public-sector savings banks and mutual savings-cooperative banks possess a high degree of regional market knowledge, which lays the ground for their place-based business model. Beyond this, the embeddedness of the regional banks investigated is particularly facilitated by their proximity-dependent operations in the segment of the customized financial services such as the management of company succession, start-up and internationalization services. Hence, the banks generate a strong regional identity and use it as an asset in the relationship with regional SMEs to safeguard a place-based business model. The housebank relationship, thus, lays the ground for their high levels of regional identity. The banks, thus, invest in the building and developing of co-operation with SMEs and other stakeholders in the region, which also goes beyond the provision of financial services. Through these network relationships, they acquire regional-specific market knowledge, for example, about a company’s creditworthiness and future expansion plans. As a result, these investments in regional-identity creation pay off for the banks because the regional SMEs share regional identity with them as a joint value.

Taken together, the housebank relationship, and the relationship banking taking place within this key SME-bank relationship, as well as other network relationships in the specific region, along with the engagement of banks for the region, jointly support the small regional banks in performing better than their competitors located outside the regional market. This latter finding is echoed by Hasan et al. (Citation2019), who show that Polish co-operative banks have a positive influence on regional economic development, based on relationship banking and local interactions.

7. Conclusion and limitations

Place-based entrepreneurship with small regional banks is determined by the long-term, resiliet, housebank relationship between the banks and regional SMEs and shaped by the interplay of static and dynamic proximity relations. Together, these factors result in a strategy of regional engagement and investments in regional identity on the part of small regional banks to sustain a competitive advantage over large competitors – despite a seemingly placeless financial market. Although small regional banks are limited to and dependent on regional markets, they use place as a factor to strategically develop and sustain their place-based business model. These findings are in line with evidence from other European countries about small, regional or niche-based banks and their competitiveness respectively role in fostering regional financing, notably for SMEs (Hasan et al. Citation2019; Degryse et al. Citation2017; Hakenes et al. Citation2015; Fiordelisi and Mare Citation2014; Howorth and Moro Citation2006).

With this conclusion, the study contributes to the literature on place-based entrepreneurship by confirming that entrepreneurial operations are not placeless (cf. Shrivastava and Kennelly Citation2013) and showing how SMEs can develop place as a competitiveness factor and strategic asset. As a final comment, this paper contributes to this emerging, yet understudied debate by providing insights into how such a place-based business model can be maintained by small companies in the global and seemingly placeless marketplace.

As an illustrative case study, this study faces some important limitations that deserve being mentioned. First, the perspective of the SMEs cannot be directly addressed with the research design chosen for this paper. Generally, there is a lack on data on SMEs regarding their bank relationships. For the country studied, Germany, official sources, such as the German Federal Bank or the German Association of Public-Sector Savings Banks, do not provide these data, and studies investigating corporate borrowers would heavily depend on surveys to generate primary data, which was not feasible within the framework of the present study. Second, the role of policy (notably EU and supranational policies) is only implicitly mentioned in this paper, although it matters for the long-term survival of small regional banks in the EU. The regulatory requirements for financial services in the EU have led to more restrictive credit-lending conditions in the past years, putting the personal element in the relationship with regional SMEs at risk and limiting the flexibility of banks about customized loan decisions. Therefore, policy as a factor in the SME-regional bank relationship should be looked at in greater depth in future studies. Finally, another limitation is associated with the exploratory research approach and the small sample size. Although case-study research is an acknowledged and powerful research approach with qualitative studies (Gioia et al. Citation2013; Siggelkow Citation2007), which particularly adds to the building of theory through the exploration of understudied phenomena, the explanatory power of the present case-study is limited and needs validation in follow-up studies. Since the sample of small regional banks was designed in a single-country research setting, future research should carefully verify the rigor of the findings attained, based on a larger, representative sample among banks respectively a sample in a multi-country setting such as several countries in the EU.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Birgit Leick

Birgit Leick is a business economist and currently Associate Professor in Innovation and Entrepreneurship in the Business School of the University of South-Eastern Norway. Her current research interests are entrepreneurship in the creative industries, digital entrepreneurs and the sharing economy, and regional economic development.

Grit Leßmann

Grit Leßmann is an economist and works as Full Professor in Business Administration with a specialization on regional economic development in Ostfalia University of Applied Sciences in Germany. Her current research focuses on business networks, regional networks and innovation.

Alexander Ströhl

Alexander Ströhl is a doctoral student in economic geography in the University of Bayreuth in Germany. His research focuses on institutional change, shrinking regions and regional resilience.

Tim Pargent

Tim Pargent is a member of the regional parliament in the German state of Bavaria and a former master student in the Institute of Geography, University of Bayreuth.

Notes

1 We skip the other proximities mentioned in Boschma (Citation2005) because we deem them as being of minor importance for the specific relationship addressed here.

References

- Agrawal, Ajay, Devesh Kapur, and John McHale. 2008. “How Do Spatial and Social Proximity Influence Knowledge Flows? Evidence from Patent Data.” Journal of Urban Economics 64 (2): 258–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2008.01.003.

- Baas, Timo, and Mechthild Schrooten. 2006. “Relationship Banking and SMEs: A Theoretical Analysis.” Small Business Economics 27 (2-3): 127–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-006-0018-7.

- Balland, Pierre-Alexandre, Ron Boschma, and Koen Frenken. 2015. “Proximity and Innovation: From Statics to Dynamics.” Regional Studies 49 (6): 907–920. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2014.883598.

- Behr, Patrick, and André Güttler. 2007. “Credit Risk Assessment and Relationship Lending: An Empirical Analysis of German Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises.” Journal of Small Business Management 45 (2): 194–213. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-627X.2007.00209.x.

- Ben Letaifa, Soumaya, and Yves Rabeau. 2013. “Too Close to Collaborate? How Geographic Proximity Could Impede Entrepreneurship and Innovation.” Journal of Business Research 66 (10): 2071–2078. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.02.033.

- Berger, Allen N., and Gregory F. Udell. 1995. “Relationship Lending and Lines of Credit in Small Firm Finance.” The Journal of Business 68 (3): 351–381. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2353332.

- Berger, Allen N., and Gregory F. Udell. 2006. “A More Complete Conceptual Framework for SME Finance.” Journal of Banking & Finance 30 (11): 2945–2966. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2006.05.008.

- Berglund, Karin, Johan Gaddefors, and Monica Lindgren. 2016. “Provoking Identities: Entrepreneurship and Emerging Identity Positions in Rural Development.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 28 (1-2): 76–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2015.1109002.

- Bollweg, Lars, Richard Lackes, Markus Siepermann, and Peter Weber. 2020. “Drivers and Barriers of the Digitalization of Local Owner Operated Retail Outlets.” Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship 32 (2): 173–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/08276331.2019.1616256.

- Boot, Arnoud W. A. 2000. “Relationship Banking: What Do We Know?” Journal of Financial Intermediation 9 (1): 7–25. https://doi.org/10.1006/jfin.2000.0282.

- Bornheim, Stefan P., and Thomas H. Herbeck. 1998. “A Research Note on the Theory of SME-Bank Relationships.” Small Business Economics 10 (4): 327–331.. :1007907427042.

- Boschma, Ron. 2005. “Proximity and Innovation: A Critical Assessment.” Regional Studies 39 (1): 61–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/0034340052000320887.

- Bundesbank, Deutsche. 2018. Bankstellenbericht 2017. Frankfurt am Main: Deutsche Bundesbank.

- Bundesverband der Deutschen Volks- und Raiffeisenbanken 2019. Alle Volksbanken Und Raiffeisenbanken per Ende 2018* (Werte in Tausend Euro). Berlin: Bundesverband der Deutschen Volks- und Raiffeisenbanken.

- Bürcher, Sandra. 2017. “Regional Engagement of Locally Anchored Firms and Its Influence on Socio-Economic Development in Two Peripheral Regions over Time.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 29 (7-8): 692–714. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2017.1330903.

- Bürcher, Sandra, and Antoine Habersetzer. 2016. “Entrepreneurship in Peripheral Regions: A Relational Perspective.” In Geographies of Entrepreneurship, edited by Mack, Elisabeth A., and Haifeng Qian, 143–164. London: Routledge.

- Cantino, Valter, Alain Devalle, Damiano Cortese, Francesca Ricciardi, and Mariangela Longo. 2017. “Place-Based Network Organizations and Embedded Entrepreneurial Learning: Emerging Paths to Sustainability.” International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research 23 (3): 504–523. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-12-2015-0303.

- Conrad, Alexander, Alexander Hoffmann, and Doris Neuberger. 2018. “Physische Und Digitale Erreichbarkeit Von Finanzdienstleistungen Der Sparkassen Und Genossenschaftsbanken.” Review of Regional Research 38 (2): 255–284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10037-018-0121-7.

- Crescenzi, Riccardo, Max Nathan, and Andrés Rodríguez-Pose. 2016. “Do Inventors Talk to Strangers? on Proximity and Collaborative Knowledge Creation.” Research Policy 45 (1): 177–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2015.07.003.

- Dass, Nishant, and Massimo Massa. 2011. “The Impact of a Strong Bank-Firm Relationship on the Borrowing Firm.” Review of Financial Studies 24 (4): 1204–1260. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhp074.

- Deeg, Richard. 1998. “What Makes German Banks Different.” Small Business Economics 10 (2): 93–101. .

- Degryse, Hans, Kent Matthews, and Tianshu Zhao. 2017. “Relationship Banking and Regional SME Financing: The Case of Wales.” International Journal of Banking, Accounting and Finance 8 (1): 93–118. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBAAF.2017.085324.

- Degryse, Hans, and Steven Ongena. 2005. “Distance, Lending Relationships, and Competition.” The Journal of Finance 60 (1): 231–266. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2005.00729.x.

- Deutscher Sparkassen- und Giroverband e.V 2019. Sparkassenrangliste 2018. Berlin: Deutscher Sparkassen- und Giroverband e.V.

- Deutscher Sparkassen- und Giroverband e.V. 2018. Finanzbericht 2017 Der Sparkassen-Finanzgruppe. Berlin: Deutscher Sparkassen- und Giroverband e.V.

- Dybdahl, Linn Meidell, 2019. “Business Model Innovation for Sustainability through Localism.” Innovation for Sustainability: Business Transformations towards a Better World, edited by Bocken, Nancy, Ritala, Paavo, Albareda, Laura and, and Peter Verburg. 193–211. Cham: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Eisenhardt, Kathleen M. 1989. “Building Theories from Case Study Research.” Academy of Management Review 14 (4): 532–550. https://www.jstor.org/stable/258557.

- Eisenhardt, Kathleen M., and Melissa E. Graebner. 2007. “Theory Building from Cases: Opportunities and Challenges.” Academy of Management Journal 50 (1): 25–32. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.24160888.

- Elsas, Ralf. 2005. “Empirical Determinants of Relationship Lending.” Journal of Financial Intermediation 14 (1): 32–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfi.2003.11.004.

- Elsas, Ralf, and Jan P. Krahnen. 1998. “Is Relationship Lending Special? Evidence from Credit-File Data in Germany.” Journal of Banking & Finance 22 (10-11): 1283–1316. nohttps://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-4266. (98)00063-6.

- Elyasiani, Elyas, and Lawrence G. Goldberg. 2004. “Relationship Lending: A Survey of the Literature.” Journal of Economics and Business 56 (4): 315–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconbus.2004.03.003.

- Feldman, Maryann P. 2001. “The Entrepreneurial Event Revisited: Firm Formation in a Regional Context.” Industrial and Corporate Change 10 (4): 861–891.

- Fiordelisi, Franco, and Davide S. Mare. 2014. “Competition and Financial Stability in European Cooperative Banks.” Journal of International Money and Finance 45: 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jimonfin.2014.02.008.

- Fitjar, Rune D., and Andrés Rodríguez-Pose. 2017. “Nothing is in the Air.” Growth and Change 48 (1): 22–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/grow.12161.

- Flögel, Franz, 2016. and, and Stefan Gärtner. Niedrigzinsphase, Standardisierung, Regulierung: Regionale Banken Was Nun?, IAT Discussion Papers 16–02. Gelsenkirchen: Institut für Arbeit und Technik.

- Flögel, Franz, 2018. and, and Stefan Gärtner. Ein Vergleich Der Bankensysteme in Deutschland, Dem Vereinigten Königreich Und Spanien Aus Räumlicher Perspektive. Befunde Und Handlungsbedarf, IAT Discussion Papers 18-01, Gelsenkirchen: Institut für Arbeit und Technik.

- Gärtner, Stefan. 2009. Lehren Aus Der Finanzkrise: Räumliche Nähe Als Stabilisierender Faktor, Gelsenkirchen: Institut für Arbeit und Technik.

- Gärtner, Stefan, and Franz Flögel. 2013. “Dezentrale versus Zentrale Bankensysteme?” Zeitschrift Für Wirtschaftsgeographie 57 (1-2): 105–121. https://doi.org/10.1515/zfw.2013.0009.

- Gärtner, Stefan, and Franz Flögel. 2017. Raum Und Banken. Zur Funktionsweise Regionaler Banken, Baden-Baden: Nomos.

- Gill, Rebecca, and Gregory S. Larson. 2014. “Making the Ideal (Local) Entrepreneur: Place and the Regional Development of High-Tech Entrepreneurial Identity.” Human Relations 67 (5): 519–542. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726713496829.

- Gioia, Dennis A., Kevin G. Corley, and Aimee L. Hamilton. 2013. “Seeking Qualitative Rigor in Inductive Research: Notes on the Gioia Methodology.” Organizational Research Methods 16 (1): 15–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428112452151.

- Guest, Greg, Arwen Bunce, and Laura Johnson. 2006. “How Many Interviews Are Enough? an Experiment with Data Saturation and Variability.” Field Methods 18 (1): 59–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X05279903.

- Hakenes, Hendrik, Iftekhar Hasan, Philip Molyneux, and Ru Xie. 2015. “Small Banks and Local Economic Development.” Review of Finance 19 (2): 653–683. https://doi.org/10.1093/rof/rfu003.

- Hansen, Teis. 2015. “Substitution or Overlap? the Relations between Geographical and Non-Spatial Proximity Dimensions in Collaborative Innovation Projects.” Regional Studies 49 (10): 1672–1684. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2013.873120.

- Hasan, Iftekar, Krzysztof Jackowicz, Oskar Kowalewski, and Łukasz Kozłowski. 2019. “The Economic Impact of Changes in Local Bank Presence.” Regional Studies 53 (5): 644–656. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2018.1475729.

- Höwer, Daniel. 2016. “The Role of Bank Relationships When Firms Are Financially Distressed.” Journal of Banking & Finance 65: 59–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2016.01.002.

- Howorth, Carole, and Andrea Moro. 2006. “Trust within Entrepreneur Bank Relationships: Insights from Italy.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 30 (4): 495–517. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2006.00132.x.

- Huber, Franz. 2012. “On the Role and Interrelationship of Spatial, Social and Cognitive Proximity: Personal Knowledge Relationships of R&D Workers in the Cambridge Information Technology Cluster.” Regional Studies 46 (9): 1169–1182. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2011.569539.

- Hüfner, Felix. 2010. The German Banking System: Lessons from the Financial Crisis. OECD Economics Department Working Papers no. 788. Paris: OECD.

- Jussila, Iiro, Ulla Kotonen, and Pasi Tuominen. 2007. “Customer-Owned Firms and the Concept of Regional Responsibility: Qualitative Evidence from Finnish Co-Operatives.” Social Responsibility Journal 3 (3): 35–43. https://doi.org/10.1108/17471110710835563.

- Knoben, Joris, and Leon A. G. Oerlemans. 2006. “Proximity and Inter‐Organizational Collaboration: A Literature Review.” International Journal of Management Reviews 8 (2): 71–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2006.00121.x.

- Koetter, Michael, Felix Noth, and Oliver Rehbein. 2020. “Borrowers Under Water! Rare Disasters, Regional Banks, and Recovery Lending.” Journal of Financial Intermediation 43: 100811. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfi.2019.01.003.

- Markowska, Magdalena, and Henry Lopez-Vega. 2018. “Entrepreneurial Storying: Winepreneurs as Crafters of Regional Identity Stories.” The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation 19 (4): 282–297. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465750318772285.

- Mattes, Jannika. 2012. “Dimensions of Proximity and Knowledge Bases: Innovation between Spatial and Non-Spatial Factors.” Regional Studies 46 (8): 1085–1099. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2011.552493.

- McKeever, Edward, Sarah Jack, and Alistair Anderson. 2015. “Embedded Entrepreneurship in the Creative Re-Construction of Place.” Journal of Business Venturing 30 (1): 50–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2014.07.002.

- Menzel, Max P. 2015. “Interrelating Dynamic Proximities by Bridging, Reducing and Producing Distances.” Regional Studies 49 (11): 1892–1907. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2013.848978.

- Mercieca, Steve, Klaus Schaeck, and Simon Wolfe. 2007. “Small European Banks: Benefits from Diversification?” Journal of Banking & Finance 31 (7): 1975–1998. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2007.01.004.

- Mercieca, Steve, Klaus Schaeck, and Simon Wolfe. 2009. “Bank Market Structure, Competition, and SME Financing Relationships in European Regions.” Journal of Financial Services Research 36 (2-3): 137–155. nohttps://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-009-0060-0.

- Miles, Matthew B., A. Michael Huberman, and Johnny Saldaña. 2018 Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. 4th ed., Kindle ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Molina-Morales, FXavier, José A. Belso-Martínez, Francisco Más-Verdú, and Luis Martínez-Cháfer. 2015. “Formation and Dissolution of Inter-Firm Linkages in Lengthy and Stable Networks in Clusters.” Journal of Business Research 68 (7): 1557–1562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.01.051.

- Moriggi, Andrea. 2020. “Exploring Enabling Resources for Place-Based Social Entrepreneurship: A Participatory Study of Green Care Practices in Finland.” Sustainability Science 15 (2): 437–453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-019-00738-0.

- Moro, Andrea, Mike R. Lucas, and Devendra Kodwani. 2012. “Trust and the Demand for Personal Collateral in SME-Bank Relationships.” The Journal of Entrepreneurial Finance 16 (1): 57–79.

- Neuberger, Doris, 2001. and, and Solvig Räthke. “Klassische versus Elektronische Vertriebswege Von Bankdienstleistungen Für Kleine Unternehmen-Ergebnisse Einer Befragung Von Freiberuflern in.” Rostock, Bad Doberan Und Güstrow, Thünen-Series of Applied Economic Theory 30, Rostock: University of Rostock, Institute of Economics.

- Neuberger, Doris, and Solvig Räthke. 2009. “Microenterprises and Multiple Bank Relationships: The Case of Professionals.” Small Business Economics 32 (2): 207–229. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-007-9076-8.

- O’Reilly, Kelley, David Paper, and Sherry Marx. 2012. “Demystifying Grounded Theory for Business Research.” Organizational Research Methods 15 (2): 247–262. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428111434559.

- Paci, Raffaele, Emanuela Marrocu, and Stefano Usai. 2014. “The Complementary Effects of Proximity Dimensions on Knowledge Spillovers.” Spatial Economic Analysis 9 (1): 9–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/17421772.2013.856518.

- Pahnke, André, and Friedrike Welter. 2019. “The German Mittelstand: Antithesis to Silicon Valley Entrepreneurship?” Small Business Economics 52 (2): 345–358. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0095-4.

- Petersen, Mitchell A., and Raghuram G. Rajan. 2002. “Does Distance Still Matter? the Information Revolution in Small Business Lending.” The Journal of Finance 57 (6): 2533–2570. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6261.00505.

- Porter, Michael E., and Mark R. Kramer. 2006. “Strategy and Society: The Link between Competitive Advantage and Corporate Social Responsibility.” Harvard Business Review 85 (6): 78–93.

- Raab-Kratzmeier, Simone. 2014. Genossenschaftsbanken im Wettbewerb: Eine theoretische Analyse. Münster: LIT.

- Raagmaa, Garri. 2002. “Regional Identity in Regional Development and Planning.” European Planning Studies 10 (1): 55–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654310120099263.

- Rychen, Frédéric, and Jean-Benoît Zimmermann. 2008. “Clusters in the Global Knowledge-Based Economy: Knowledge Gatekeepers and Temporary Proximity.” Regional Studies 42 (6): 767–776. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400802088300.

- Saldaña, Johnny. 2016. The Coding Manual Qualitative for Researchers. London: Sage.

- Scheike, Alexander. 2004. Rechtliche Voraussetzungen Für Die Materielle Privatisierung Kommunaler Sparkassen: eine Untersuchung Unter Besonderer Berücksichtigung Der Rechtsform Der Eingetragenen Genossenschaft. Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

- Schrumpf, Heinz, 2001. and, and Beate Müller. Sparkassen Und Regionalentwicklung: eine Empirische Studie Für Die Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Berlin: Deutscher Sparkassen-Verlag.

- Seikel, Daniel. 2017. “Saving Banks and Landesbanken in the German Political Economy: The Long Struggle between Private and Public Banks.” In Public Banks in the Age of Financialization. A Comparative Perspective, edited by Christoph Scherrer, 155–175. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Sellar, Christian. 2015. “Italian Banks and Business Services as Knowledge Pipelines for SMEs: Examples from Central and Eastern Europe.” European Urban and Regional Studies 22 (1): 41–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776412465628.

- Shrivastava, Paul, and James J. Kennelly. 2013. “Sustainability and Place-Based Enterprise.” Organization & Environment 26 (1): 83–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026612475068.

- Siggelkow, Nicolaj. 2007. “Persuasion with Case Studies.” Academy of Management Journal 50 (1): 20–24. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.24160882.

- Stein, Jeremy C. 2002. “Information Production and Capital Allocation: Decentralized versus Hierarchical Firms.” The Journal of Finance 57 (5): 1891–1921. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-1082.00483.

- Steinmo, Marianne, and Einar Rasmussen. 2016. “How Firms Collaborate with Public Research Organizations: The Evolution of Proximity Dimensions in Successful Innovation Projects.” Journal of Business Research 69 (3): 1250–1259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.09.006.

- Strauss, Anselm, and Juliet Corbin. 1997. Grounded Theory in Practice. Thousand Oaks, Sage.

- Sunley, Peter, Britta Klagge, Christian Berndt, and Ron Martin. 2005. “Venture Capital Programmes in the UK and Germany: In What Sense Regional Policies?” Regional Studies 39 (2): 255–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/0034340052000321913.

- Torre, André, 2014. and, and Frédéric Wallet. “Introduction. The Role of Proximity Relations in Regional and Territorial Development Processes.” In Regional Development and Proximity Relations, edited by André Torre, and Frédéric Wallet, 1–44. London: Edward Elgar.

- Ughetto, Elisa, Marc Cowling, and Neil Lee. 2019. “Regional and Spatial Issues in the Financing of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises and New Ventures.” Regional Studies 53 (5): 617–619. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1601174.

- Usai, Stefano, and Marco Vannini. 2005. “Banking Structure and Regional Economic Growth: Lessons from Italy.” The Annals of Regional Science 39 (4): 691–714. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-005-0022-x.

- Uzzi, Brian. 1999. “Embeddedness in the Making of Financial Capital: How Social Relations and Networks Benefit Firms Seeking Financing.” American Sociological Review 64 (4): 481–505.

- Vlasov, Maxim, Karl Johan Bonnedahl, and Zsuzsanna Vincze. 2018. “Entrepreneurship for Resilience: Embeddedness in Place and in Trans-Local Grassroots Networks.” Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy 12 (3): 374–394. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEC-12-2017-0100.

- Wincent, Joakim. 2005. “Does Size Matter? a Study of Firm Behavior and Outcomes in Strategic SME Networks.” Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 12 (3): 437–453. https://doi.org/10.1108/14626000510612330.

- Wójcik, Dariusz, and Duncan MacDonald-Korth. 2015. “The British and the German Financial Sectors in the Wake of the Crisis: Size, Structure and Spatial Concentration.” Journal of Economic Geography 15 (5): 1033–1054. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbu056.

- Yin, Robert K. 2018. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.