Abstract

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) play an important role for growth and sustainable development, particularly for rural areas in which MNCs are absent. Despite this link, there is little systematic research that investigates how SMEs address the particularities, opportunities, and challenges of rural areas based on their strengths and weaknesses. To fill this gap, this article uses a systematic literature review (SLR) that analyses 228 articles published between 2003 and October 2020. Our descriptive analysis shows that research on this topic has increased over time. Based on our thematic results, we juxtapose typical strengths and weaknesses of SMEs (enterprise perspective) and the opportunities and challenges of rural areas (spatial perspective). A key finding is that SMEs use relation-based collaboration as a meta-strategy to respond to these specific conditions. Wedding the theoretical perspectives of the RBV and transaction cost economics, we develop a conceptual model that explains why rural SMEs are in a particular need and position to use collaboration as a tool to innovate and access critical resources in otherwise resource-scarce rural areas. We then discuss how digitalization impacts our results regarding SMEs in rural space.

Résumé

Les petites et moyennes entreprises (PME) jouent un rôle important pour la croissance et le développement durable, en particulier dans les zones rurales dans lesquelles les multinationales sont absentes. Malgré ce lien, il existe peu de recherches systématiques qui examinent comment les PME abordent les particularités, les opportunités et les défis des zones rurales, en se basant sur leurs forces et leurs faiblesses. Afin de combler cette lacune, cet article utilise une revue systématique de la littérature (RSL) qui analyse 228 articles publiés entre 2003 et octobre 2020. Notre analyse descriptive montre que la recherche sur ce thème a pris de l’ampleur au fil du temps. En nous basant sur nos résultats thématiques, nous juxtaposons les forces et les faiblesses typiques des PME (perspective entrepreneuriale) et les opportunités et les défis des zones rurales (perspective spatiale). L’une des conclusions principales est que les PME utilisent une collaboration basée sur les relations comme une méta-stratégie en riposte à ces conditions spécifiques. En mariant les perspectives théoriques de la vue basée sur les ressources (RBV) et de l’économie des coûts de transaction, nous développons un modèle conceptuel qui explique pourquoi les PME rurales ont un besoin et une position particuliers pour utiliser la collaboration comme un outil d’innovation et d’accès à des ressources critiques dans des zones rurales autrement pauvres en ressources. Nous traitons ensuite de la manière dont la numérisation impacte nos résultats en ce qui concerne les PME dans l’espace rural.

1. Introduction

Small- and medium sized enterprises (SME) provide an important contribution to sustainable economic development and employment within Europe and across the globe (Ayyagari, Beck, and Demirguc-Kunt Citation2007). Indeed, SMEs are often described as ‘job engines’ and the backbone of economic development (Muller et al. Citation2016; Mandl et al. Citation2016).

To fulfil this essential role within the economy, SMEs have to adapt to various internal and external factors including their spatial context. On top of challenges faced by most SMEs such as resource constraints, SMEs are often also greatly affected and shaped by the space they operate in i.e., whether they are located in a rural or metropolitan area (Korsgaard, Müller, et al. Citation2015; Kranzusch, May-Strobl, and Levering Citation2017; Zhao and Jones-Evans Citation2016). While multi-national companies (MNCs) usually operate in several places and can fairly easily shift their activities from one location to another, SMEs often only have one location on which they consequently depend more critically. Seen this way, place matters for SMEs even more than for MNCs.

In a rural context, SMEs can have an important, positive impact on growth and sustainable rural development (Berlemann and Jahn Citation2016; Kranzusch, May-Strobl, and Levering Citation2017; Korsgaard, Müller, et al. Citation2015). In contrast to a more metropolitan context, SMEs and their owner-managers tend to be more embedded in their rural region and society (Lang, Fink, and Kibler Citation2014; Courtney, Lépicier, and Schmitt Citation2008; Harangozó and Zilahy Citation2015). As a consequence, their feeling of responsibility for their regions is often higher which in turn leads SMEs in rural areas to shape its future, create new jobs, seek benefits for the community, and foster innovation (Fortunato Citation2014; Lang, Fink, and Kibler Citation2014; Berlemann and Jahn Citation2016).

Given their ‘lack of human, cultural or financial capital’ (Korsgaard, Müller, et al. Citation2015), however, rural spatial contexts can create additional challenges for SMEs ranging from economic decline, underemployment, limited export possibilities to lower qualification levels and underdeveloped infrastructure (Mayer and Baumgartner Citation2014; Horlings and Padt Citation2013; Martin and Sunley Citation2006; Benneworth Citation2004). At the same time, rural areas can also offer unique historic, cultural, or physical resources (Korsgaard, Ferguson, et al. Citation2015), thus opening up opportunities for SMEs.

In light of this important link between rural SMEs and rural spatial contexts, there has been a growing number of publications concerned with rural SMEs or rural development (see e.g., Henry and McElwee Citation2014). Yet, despite many valuable insights, there is only limited research that systematically links the particularities of the spatial context of rural areas with the challenge of managing SMEs in rural areas. To fill this gap and to provide a comprehensive and structured combination of these contexts, we conducted a systematic literature review (SLR). With the help of the systematic review of 228 academic publications, we aim to answer the overarching research question of ‘How do rural SMEs use their strengths and weaknesses to address the particular opportunities and challenges in the spatial context of rural areas?’.

By answering this overarching research question, this paper contributes to the literature in five ways: First, our descriptive analysis serves to map the state of research on rural SMEs, discuss blind spots of the literature, and suggest avenues for further research. Second, based on a thematic analysis and synthesis, we derive an overview of internal and external factors that characterize the situation of SMEs in rural areas. Here, we point out that many of these factors are ambivalent and can affect economic venturing both in a positive and negative way. Third, based on this analysis, we discuss how SMEs use above all collaborative and network strategies to respond to this situation. Here, our analysis maps the forms, partners, and purposes of collaboration in rural areas. Fourth, wedding the theoretical perspectives of the resource-based view and transaction cost economics, we develop a conceptual model that explains the prominent role of relationship-based collaboration for SMEs in rural areas. We show that the relevant characteristics of rural SMEs and rural spaces create both a particular need as well as particular opportunities for relation-based, longer-term collaboration. Fifth, we discuss how digitalization impacts our results regarding SMEs in rural spaces and spell out implications for policy makers and SMEs.

To develop these contributions, the paper proceeds as follows: First, we will provide a brief theoretical background and refine our research questions. Second, the paper will outline the methodology of the SLR. In a third step, we will illustrate its descriptive results. Fourth, we will present our thematic results before discussing our findings in a fifth step and deriving implications for practitioners with a framework and further research. The paper concludes with a short summary.

2. Research and theoretical background

Before introducing and conducting our SLR, this section serves both to specify its contextual background and terminology as well as to refine our research questions that invite the application of the SLR methodology.

A first challenge towards conceptualizing the nexus between SMEs and their rural environment lies in the fact that in most of the literature there is ‘no clear definition of what constitutes a rural business’ (Henry and McElwee Citation2014, 3). We address this challenge by first defining our perspective on SMEs and the rural context before then deriving a definition for rural enterprises.

2.1. The enterprise perspective: Small and medium sized enterprises

While national definitions of SMEs vary (Hillary Citation2006; Klewitz and Hansen Citation2014), there are certain quantitative and qualitative characteristics that regularly emerge in the discussion of SMEs (Loecher Citation2000).

Quantitative criteria: Most definitions of SMEs contain quantitative criteria (Günterberg and Kayser Citation2004; Loecher Citation2000; Oricchio et al. Citation2017; European Union Commission Citation2003). Indeed, research found over 200 SME definitions worldwide (Loecher Citation2000)) which points to challenges in precisely defining SMEs (Klewitz and Hansen Citation2014; Oricchio et al. Citation2017; Hillary Citation2006) based on quantitative criteria. Despite these variances within the literature, there seems to be an emerging point of convergence that understands SMEs as organizations employing less than 500 full-time equivalent staff (Ayyagari, Beck, and Demirguc-Kunt Citation2007). Within this scale, SMEs are often further segmented into micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises. The exact cut-off between these three segments varies depending on national definitions. Supplementing or complementing staff figures, many countries also have turnover limits to delineate SMEs. Thus, companies that employ more than 500 staff might still be considered an SME if their earnings are smaller than the upper rate. As the purpose of this study is to compare international research, we neglect this quantitative criterion for lack of comparability and only focus on staff numbers.

Qualitative criteria: While there are many differences between SMEs, the literature identified common particularities or characteristics that – at least the majority of – SMEs share. Due to their smaller size, SMEs are often struggling with resource constraints – be it financial, personnel, time, or knowledge (del Brío and Junquera Citation2003; Spence Citation1999; European Union Commission Citation2003). Furthermore, SMEs tend to be more centrally organized and are often owned privately and thus led by owner-managers who often present a prominent figure within a SME (Günterberg and Kayser Citation2004; Loecher Citation2000). Due to their personal involvement in the business, their views and values shape the business in its strategy and operations. Moreover, as an owner-manager’s name is often used synonymously with their business, they tend to be more involved in the local community to create a good standing for themselves and their business.

Due to their smaller size, the level of division of labor is also comparatively lower in SMEs i.e., employees often perform multiple tasks rather than being very specialized. Their small size also often leads to more informal communication (Bos-Brouwers Citation2009).

In sum, for the purpose of this paper, we define SMEs quantitatively in terms of their employees and qualitatively as organizations that are run by owner-managers, have more informal and flexible communication as well as organizational structures, and that face resource constraints.

2.2. The spatial perspective: Rural areas

The difference between the spatial contexts of urban and rural areas matters when analyzing organizations (Baù et al. Citation2019; Dax Citation1996; Muñoz and Kimmitt Citation2019; Zonneveld and Stead Citation2007). Depending on the research interest, rural context can be explored as a spatial, cultural, social, or economic phenomenon (Gaddefors and Anderson Citation2019). Similar to SMEs, definitions of rural areas include both quantitative and qualitative criteria (Cloke Citation2006; Copus, Skuras, and Tsegenidi Citation2009; Hoggart Citation1988; Kūle Citation2008; Pato and Teixeira Citation2016).

Quantitative criteria predominantly focus on population density as the defining characteristic (eurostat Citation2016; OECD 2011). On the qualitative side, rural areas often have less developed infrastructure (Stathopoulou, Psaltopoulos, and Skuras Citation2004). This ranges from the access to public transport to healthcare and schooling as well as to the quality of roads and other physical infrastructure. However, limiting a discussion of rural areas to its level of infrastructure and population density would be short-sighted. From a sociological perspective, life in rural areas – or rurality as it is sometimes referred to – is often quite different from that of urban areas. For instance, the distinction between public and private space is often less clear in rural areas (Murdoch and Marsden Citation1994). Here, spaces commonly considered public spaces, such as a marketplace, are seen as private to the local residences in a rural area. In other words, if strangers enter such spaces, they are more likely to face scrutiny than they would in similar urban spaces. Furthermore, rural communities tend to be more tightly knit and built on interdependencies (Murdoch and Marsden Citation1994).

2.3. Defining rural SMEs

Building upon these concise reviews of SMEs and rurality, we can now sharpen our definition of rural SMEs. To this end, we build upon and adapt the three parameters proposed by Henry and McElwee (Citation2014) to define a rural business. First, highlighting the spatial perspective, a rural SME’s primary location (in terms of main physical infrastructure and majority of employees) is situated in a rural context. Second, highlighting both spatial and quantitative SME criteria, a rural SME employs people within a specified travel to work area, yet less than 500 full-time equivalents. Third, highlighting economic embeddedness, a rural SME contributes to gross value added (GVA) in its rural environment. We thus exclude entities that just happen to be domiciled in the rural yet lack real embeddedness such as e.g., a self-employed homeworker with no value creation partners in the region.

2.4. The nexus between SMEs and the rural context

While some extant research indicates that the spatial context influences the entrepreneurial or management context (Korsgaard, Ferguson, et al. Citation2015; Muñoz and Kimmitt Citation2019; Trettin and Welter Citation2011), research on the particularities of venturing in rural areasFootnote1 is nonetheless limited (Baù et al. Citation2019; Muñoz and Kimmitt Citation2019; Trettin and Welter Citation2011; Welter Citation2011). Moreover, as SMEs often dominate in rural areas (Shields Citation2005), the enterprise-space nexus also works in the other direction with SMEs having an impact on the spatial context and rural development (Bürcher Citation2017; Courrent, Chassé, and Omri Citation2018; Ní Fhlatharta and Farrell Citation2017; Gray and Jones Citation2016; Salone, Bonini Baraldi, and Pazzola Citation2017).

So far, various publications have investigated selected elements of the SME-rural-area nexus by discussing specific SME practices such as the use of innovation and ICT (McKitterick et al. Citation2016; Salemink, Strijker, and Bosworth Citation2017) or the role of embeddedness in rural SME management (Baù et al. Citation2019; Korsgaard, Ferguson, et al. Citation2015; Muñoz and Kimmitt Citation2019). What is missing, however, is a systematic overview of both typical particularities of rural areas and rural SMEs as well as of the general strategic responses of SMEs that acknowledge these particularities. Given the diversity of rural contexts and SMEs, gaining such an overview is difficult with a single case, interview, or survey study.

Against this background, we suggest conducting a systematic literature review (SLR) as a useful methodology that can distil the breadth and diversity of existing research to deduce generalizable insights about the situation of SMEs in rural areas. More specifically, we use the SLR to address the following research questions.

2.5. Research questions

First, since the quality of the results that a SLR can obtain depends on the state and maturity of the respective research field, the descriptive analysis of our SLR serves to map how the literature on SMEs in rural areas has evolved from January 2003 to October 2020. Such a mapping of the literature can help to orient future research by addressing the following research question:

RQ1: How has the literature developed in terms of articles, methodologies, and lead journals and where are blind spots that invite further research?

Shifting our attention to the qualitative content, we then systematically analyze the literature to determine recurring characteristics that are relevant for rural areas and rural SMEs, thus addressing the following research questions:

RQ2a: What are recurring particularities of rural contexts that matter for SMEs?

RQ2b: What are general and specific characteristics of SMEs in these rural contexts?

Third, a SLR can look beyond single cases and applications to identify, categorize, and analyze recurring strategies used by SMEs to operate in rural areas, thus addressing the following research question:

RQ3: What is the dominant response or meta-strategy that SMEs can and do use to operate in rural contexts?

Finally, going beyond a mere description of SME behavior, we seek to develop a conceptual model that can explain our findings in theoretical terms. This is also relevant to substantiate implications for practitioners and future research, thus bringing us to our final question:

RQ4: How can we theorize the interplay of rural SMEs and rural areas in a way that can explain SME strategy?

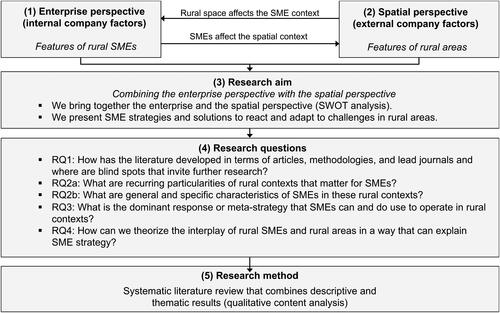

As summarizes, we thus aim to bring together the enterprise perspective and the spatial perspective for rural SMEs. In doing so, we carve out relevant features of rural SMEs and specific features of rural areas. Building on this analysis, we use the SLR to discuss recurring SME strategies to react and adapt to challenges in rural areas.

3. Research method: systematic literature review

Systematic literature reviews are an emerging research approach to investigate research topics in SME and entrepreneurship journals (e.g., Hlady-Rispal and Jouison-Laffitte Citation2014; Laufs and Schwens Citation2014) and regional studies and planning journals (Salemink, Strijker, and Bosworth Citation2017). The general aim of a systematic literature review is to get a theoretical and methodological overview of the current state of the research in a particular area. To conduct our SLR, we follow well-established processes of former SLRs (Garkisch, Heidingsfelder, and Beckmann Citation2017; Rousseau, Manning, and Denyer Citation2008) and apply the following three step research framework ().

Table 1. Overview of the systematic literature framework.

3.1. Search terms and search strings

We conducted a brief scoping study to get an initial impression of the existing literature (Denyer and Tranfield Citation2009). Following the search approach of Maier, Meyer, and Steinbereithner (Citation2016), we distinguish between sector-related search terms (context of small and medium sized enterprises) and topic-spatial-related search terms (context of rural areas) (see ). In order to get a holistic keyword list, we included keywords from former SME research (Hlady-Rispal and Jouison-Laffitte Citation2014; Laufs and Schwens Citation2014) and keywords from peer feedback (Garkisch, Heidingsfelder, and Beckmann Citation2017) provided by fellow researchers.

Table 2. Search terms.

In total, we identified 13 topic-related and 8 sector-related search terms, which were transferred into search-strings and used in database and journal search operations.

3.2. Used databases and search engines

The search was conducted as a structured search-string search in the following databases: EBSCO Business Source Premier, SCOPUS, Science Direct, Springer, ABI-INFORM Complete, INGENTA, and EconBiz. To cross-check, we further used the academic search engine GOOGLE Scholar (cf. Johnson and Schaltegger Citation2016; Roth and Bösener Citation2015).

3.3. Overview of search process

In the context of a SLR, it is particularly important to define boundaries (Seuring and Müller Citation2008). Following the approaches of Moustaghfir (Citation2008), Colicchia and Strozzi (Citation2012) and Albliwi et al. (Citation2014), we defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. We included academic papers that focused on SMEs as their core topic and which were published in English between January 2003 and October 2020.

In terms of geographic focus, we limited our search to papers that deal with SMEs in rural areas of highly developed countries, notably in Europe. Compared to developed countries, emerging economies typically rely more on the informal economy, and often have higher levels of inequality (Zeyen and Beckmann Citation2019). For SMEs, being located in a developing country thus brings about specific challenges e.g., when poor governance restricts access to formal capital markets (Cole Dietrich, and Frost Citation2012). As a consequence, rural areas in many developing and emerging economies are often not just ‘rural’ but at a very different development stage with weakly developed formal institutions thus making a comparison with Western rural areas difficult. Furthermore, conceptualizing ‘why the European context is important’, entrepreneurship researchers emphasize the role of shared cultural parameters or common regulatory constraints (Fayolle, Kyrö, and Ulijn Citation2005, pt. III) such as specific labor market conditions (Hessels and Parker Citation2013). To allow greater comparability, we therefore focused our research on SMEs in rural areas in European countries.

We excluded papers that are not full journal articles (e.g., editorials, conference papers) and papers that focused on a different regional context, or did not have SMEs as their core topic. After briefly scanning all publications according to our inclusion and exclusion criteria, we created an A-B-C List (Klewitz and Hansen Citation2014). Here, A-List publications meet all inclusion criteria which qualified them for our descriptive and thematic analysis. B-List articles are interesting for the general context. These often discussed ‘Agriculture/Farming’, ‘Tourism’, ‘Food/Brewery/Restaurants and Pubs’. Since we are interested in how the generic differences between metropolitan and rural areas influence SMEs, we excluded industries that are primarily confined to rural areas. C-List papers were considered irrelevant to our research, e.g., because the rural context was missing. In total, we derived an A-List of 228 articles.

3.4. Data analysis

Following the established SLR methodology described by Tranfield, Denyer, and Smart (Citation2003), we distinguished between a descriptive analysis (to quantitatively map the literature) and a thematic analysis (for a mapping and synthesis of qualitative content (Seuring and Müller Citation2008)).

To organize the data and codes, we have used the qualitative coding software MAXQDA. The coding process used an abductive approach. Prior to the data analysis, we defined deductive coding categories that reflected our research questions and coded the literature in terms of internal characteristics of SMEs, external characteristics of rural areas as well as recurring strategies and practices. Within these categories, we used emergent coding to inductively create codes that describe specific characteristics and practices which we then discussed and merged into code families. In order to ensure validity and reliability, the content analysis was carried out by two researchers. The results were discussed in several steps.

4. Descriptive results: mapping the state of the literature

In this section, we provide a descriptive analysis of the 228 publications. This section thus serves to give a general overview of the state and maturity of research as well as to later identify potential blind spots and research gaps.

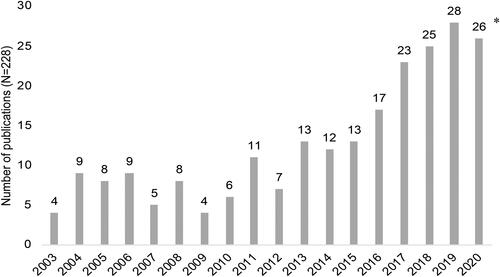

4. 1.Distribution of publications over time

The 228 A-List publications are distributed along the selected time period from January 2003 to October 2020 as shown in . During the first years (2003-2012) the frequency of publications is quite volatile whereas the numbers are constantly increasing for the time period between January 2013 and October 2020. The continuously rising number of articles in the past eight years thus mirrors increasing attention for the topic.Footnote2 At the same time, it still remains to be seen whether there is continuous exponential growth that would indicate the emergence of a specialized field.

4.2. Distribution in main journals

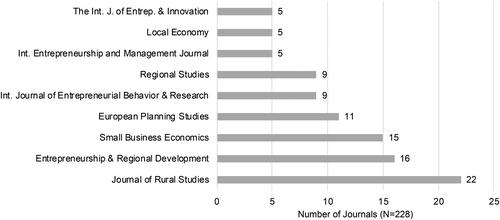

The identified literature was published in 108 different journals. The journals come from diverse disciplines including entrepreneurship and innovation research (e.g., International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research or The International Journal of Entrepreneurship & Innovation), small business research (e.g., Small Business Economics or International Small Business Journal), or regional studies and economic geography (e.g., European Planning Studies or Regional Studies). The high number of journals with one publication only illustrate that the field is somewhat scattered on the one hand. On the other, some journals contribute more strongly to the existing body of literature (), with six journals covering roughly 36% of all publications. Here, the two lead journals in terms of publication frequency, Journal of Rural Studies as well as Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, explicitly focus on the rural or regional context in their title.

4.3. Applied research methodologies

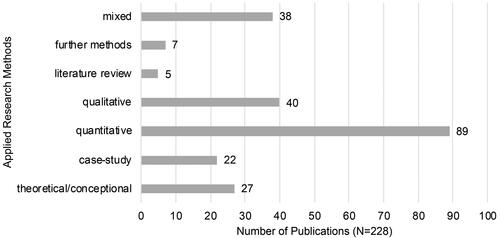

Following the literature (Hlady-Rispal and Jouison-Laffitte Citation2014; Seuring and Müller Citation2008; Silvius and Schipper Citation2014), we distinguished seven research methodologies: (1) theoretical and conceptual papers, (2) case studies, (3) quantitative approaches, (4) qualitative approaches, (5) literature reviews, (6) further methods, and (7) mixed-methods. The distribution of research methodologies is shown in .

Quantitative approaches were the most prominent research method (89 publications). While many studies used already existing quantitative datasets (Bennett, Robson, and Bratton Citation2001; Belso Martínez Citation2005; Deloof and La Rocca Citation2015; Frankish, Roberts, and Storey Citation2010), some studies collected original quantitative data (Meccheri and Pelloni Citation2006; Moilanen, Østbye, and Woll Citation2014). Note that, as our study does not engage in a quantitative meta-analysis, we refrained from integrating these data sets to conduct statistical analysis but rather carried out a thematic analysis of the qualitative content.

The second most common approach was qualitative research approaches (40 publications) followed by mixed methods (38 publications). The former mostly employ interview studies with semi-structured interviews (Bishop Citation2011; Blanchard Citation2015; Martin, McNeill, and Warren-Smith Citation2013; Wood, Watts, and Wardle Citation2004) and have sample sizes of 6 to 25 (Blanchard Citation2015; Galvão et al. Citation2020; Martin, McNeill, and Warren-Smith Citation2013).

In sum, the literature displays a pronounced diversity of research approaches, including a high proportion of quantitative work. According to the general debate on bibliometric research (Keathley et al. Citation2013), this indicates that the research field is evolving towards maturity, thus inviting the use of an SLR.

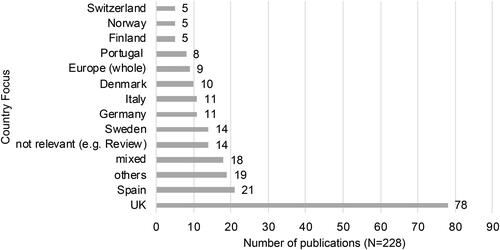

4.5. Country focus of the identified publications

The studies focus on various countries in Europe (see ). By far, the most prominent country is the United Kingdom with 78 publications followed by publications in Spain (21 publications) and mixed countries (18 publications).

Figure 5. Country focus of the identified publications (*other countries include Ireland (4), Netherlands (3), Czech Republic, France, Greece, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia (all 2) as well as Austria and Estonia (1)).

Summing up the descriptive SLR results, despite a regional imbalance that deserves further attention below, the increase in publications and breadth of methodologies suggest an evolution towards maturity of the research field that allows for further qualitative analyses.

5. Thematic results of our qualitative content analysis

The following section presents the findings of our SLR’s qualitative content analysis. Addressing RQ2a, we will first outline specific spatial characteristics of rural areas identified in the literature to be followed by relevant enterprise characteristics of rural SMEs (thus addressing RQ2b). We then point towards challenges that the combination of these characteristics poses to SMEs operating in rural areas. Turning to RQ3, we will then discuss and categorize key strategies SMEs use to address these challenges.

5.1. External factors: characteristics of rural areas

(a) The rural lifestyle – tight-knit communities: An advantage of rural areas is that the cost of living is relatively cheaper than in urban areas and it is easy to rent or buy residential or commercial buildings at low cost (Salone, Bonini Baraldi, and Pazzola Citation2017). For many, a rural lifestyle offers advantages such as enjoying ‘a jolly, light-hearted rural idyllic’ (Anderson, Wallace, and Townsend Citation2016, 7) lifestyle with access to the natural environment, lower levels of stress (Akgün et al. Citation2011) and beautiful landscape (Berglund, Gaddefors, and Lindgren Citation2016; Burnett and Danson Citation2016).

(b) Unique regional resources and cultural identity. Given their specific historic, culinary, and geographic background, rural areas can possess unique cultural identities (Burnett and Danson Citation2016) and related resources. While such a profile can be particularly relevant for the marketing of agricultural and artisanal products as well as touristic services (Galliano, Gonçalves, and Triboulet Citation2019), a strong cultural identity also affects businesses in other industries. Due to a strong sense of cultural identity, newcomers in rural areas tend to integrate very quickly (Arbuthnott and von Friedrichs Citation2013; Berglund, Gaddefors, and Lindgren Citation2016; Salone, Bonini Baraldi, and Pazzola Citation2017) which could indicate that it is easier to access social capital in rural areas.

(c) Lack of economic growth. Many rural areas struggle with economic downturn, lack of economic growth (Anderson, Osseichuk, and Illingworth Citation2010; Tregear and Cooper Citation2016), lower levels of population (Reidolf Citation2016; Smallbone, Baldock, and North Citation2003; Tregear and Cooper Citation2016) as well as with a low density in their regional business milieu (Bjerke and Johansson Citation2015; Smallbone, Baldock, and North Citation2003).

(d) Rural isolation. Rural areas are often isolated due to lack of transportation infrastructure (Anderson, Wallace, and Townsend Citation2016; Dubois Citation2016; Ferreira et al. Citation2016; Gray and Jones Citation2016; Karlsen, Isaksen, and Spilling Citation2011; Reidolf Citation2016). Local decision makers are far away from (key) markets (Byrom, Medway, and Warnaby Citation2003; Galbraith et al. Citation2017; Salamonsen and Henriksen Citation2015; Tregear and Cooper Citation2016). This is often further enhanced by long transportation ways and barriers (N hx00ED; Fhlatharta and Farrell Citation2017) and long distances to big cities (Burnett and Danson Citation2016) or to economic centers (Galbraith et al. Citation2017).

(e) Lack of everyday services and resources. While some rural areas strive, others are facing a continued decrease in the offering of essential services for daily life. These challenges include school closures (Herslund Citation2012), lack of childcare and banking-services (Ní Fhlatharta and Farrell Citation2017) as well as often underdeveloped local public transport (Smallbone, Baldock, and North Citation2003).

(f) Limited digital infrastructure. Rural communities often suffer from underdeveloped digital infrastructure (Anderson, Wallace, and Townsend Citation2016). While broadband access is increasingly important for Internet of Things solutions, digital business models, and creative practitioners (Townsend et al. Citation2017), internet bandwidth in rural areas is typically much lower compared to urban areas (Räisänen and Tuovinen Citation2020). Similarly, fast mobile services such as 4 G or 5 G have less coverage than in more densely populated areas (Bowen and Morris Citation2019). Despite government efforts to close the urban/rural ‘digital divide’, huge disparities still persist (Briglauer et al. Citation2019) with the risk of ‘prompting out-migration to areas with better digital connectivity’ (Townsend et al. Citation2017).

(g) Reduced access to financial resources and services. Financial institutions and services are often concentrated in metropolitan areas and spatially centralized in rural areas (Klagge and Martin Citation2005; Mercieca, Schaeck, and Wolfe Citation2009). SMEs which experience financial bottlenecks thus often lack adequate access to financial resources (Anderson, Osseichuk, and Illingworth Citation2010; Fortunato Citation2014). The increasing closure of rural banks (Smallbone, Baldock, and North Citation2003) exacerbates this trend.

(h) Resistance against changes and opposition to innovation. In some rural areas, entrepreneurs are seen as ‘rebels’ because they break with traditions (Benneworth Citation2004; Berglund, Gaddefors, and Lindgren Citation2016). In addition, there is only little support in creating new businesses in rural areas (Lang, Fink, and Kibler Citation2014). In many cases, this is due to local governments’ lack of power and resources to devise effective regulatory frameworks and policies to foster local entrepreneurship (Lang, Fink, and Kibler Citation2014).

(i) Socioeconomic decline: Young people leave rural regions (Berglund, Gaddefors, and Lindgren Citation2016; Herslund Citation2012). This in turn leads to lack of diversity (Fortunato Citation2014). Furthermore, higher unemployment rates for average workers and a lack of high-skilled, specialized labor (Akgün et al. Citation2011; Bürcher Citation2017; Clark, Palaskas, et al. Citation2004; Reidolf Citation2016) or low income levels (Brooksbank, Thompson, and Williams Citation2008; Clark, Palaskas, et al. Citation2004) are further challenges. This leads to socio-economic decline (R. Smith Citation2012).

In short, while rural areas are attractive to some people and have specific cultural, physical, and social resources, they face systemic structural challenges. As we will discuss below, these particularities can pose both opportunities and threats for SMEs’ economic venturing in rural spaces.

5.2. Internal factors: Relevant characteristics of SMEs in rural areas

This section presents the characteristics and practices mentioned in our literature sample to describe SMEs in rural spaces. Note that, given the SLR methodology, our findings do not claim that these characteristics apply to rural SMEs only. In fact, many aspects such as reactive or short-term management are well-known in the literature as typical characteristics of SMEs in general (Gelinas and Bigras Citation2004). However, our analysis does show which of the often-general SME characteristics are mentioned prominently in rural contexts. At the same time, the rural context seems to accentuate some SME characteristics (e.g. (a) and (b)) more than others (e.g. (e) and (f)). In the following, we summarize main features and key arguments presented in the literature as to whether these characteristics have a specific relevance for rural SMEs.

(a) Embeddedness in local communities: To address some of the characteristics of their spatial context as well as to comply with local cultures, research on SMEs in rural spaces emphasize their embeddedness in local communities (Kofler and Marcher Citation2018). This materializes for instance in their increased perceived responsibility for their community (Korsgaard, Müller, et al. Citation2015) or their focus on regional customers (Ní Fhlatharta and Farrell Citation2017). In other words, most rural SMEs aim to create value not only for the company but also for the region (Berglund, Gaddefors, and Lindgren Citation2016) and thereby contribute to socio-economic development of the region (Bürcher Citation2017). This is nicely demonstrated in a quote from Bürcher (Citation2017, 9) ‘The whole region understood that they were like a family’.

(b) Family and local ownership. This link to the local community is further strengthened by the fact that SMEs in rural areas are often family owned (Dubois Citation2016; Larsson, Hedelin, and Gärling Citation2003; Pinto, Fernandez-Esquinas, and Uyarra Citation2015). As the family that runs the business also lives in the same spatial context as their business operates in, having a good standing in the community is important for the business as well as for their personal lives. While rural communities can be tight-knit, research also indicates that once someone is considered ‘unworthy’, they are more easily isolated than they would be in urban areas.

(c) Intimate understanding of local communities and customers. This embeddedness seems to have an additional benefit to the SMEs. Research indicates that SMEs in rural areas have a much more intuitive understanding of the physical, historical, and cultural make-up of their region (Korsgaard, Müller, et al. Citation2015). As a consequence, they are often better able to serve their local clients’ needs (Anderson, Wallace, and Townsend Citation2016; Blanchard Citation2015; Blanchard Citation2017; Müller and Korsgaard Citation2018). Moreover, the tightness of local communities also means that entrepreneurs, i.e. new SMEs, are much more visible than they would be in urban spaces (Martin, McNeill, and Warren-Smith Citation2013).

(d) Willingness but limited capacity to innovate. Rural SMEs try to get the best out of the rural context despite a frequent lack of support from local authorities (Cabras Citation2011; Ramsey et al. Citation2013). To do so, they aim to be creative (Korsgaard, Müller, et al. Citation2015) and to adapt their products to market needs (Blanchard Citation2015). What is more, some SMEs take the challenges their rural context faces as a starting point for their business. These SMEs demonstrate high adaptability and willingness to experiment to solve rural challenges (Anderson, Wallace, and Townsend Citation2016; Ní Fhlatharta and Farrell Citation2017). Here again rural SMEs use their unique local knowledge (Huggins and Thompson Citation2015) to innovate (Bjerke and Johansson Citation2015; Blanchard Citation2017).

Despite these examples of creativity, research points out that rural SMEs are generally less innovative than their urban counterparts (Bjerke and Johansson Citation2015; Crowley Citation2017; McAdam, McConvery, and Armstrong Citation2004; Moilanen, Østbye, and Woll Citation2014; Triguero, Moreno-Mondéjar, and Davia Citation2016). This is mostly due to the associated costs and risks inherent in innovation activities (Bjerke and Johansson Citation2015).

(e) Age structure and conservative culture. Another reason for the lack of creativity is that rural SME managers often are older individuals (Wood, Watts, and Wardle Citation2004) and resist change (McAdam, McConvery, and Armstrong Citation2004). Furthermore, rural SMEs are often more active in more traditional industries such as fishery, agriculture, or tourism (Arbuthnott et al. Citation2011; Pinto, Fernandez-Esquinas, and Uyarra Citation2015; Salamonsen and Henriksen Citation2015). This is often because families have been living in the same area for many generations, passing down their business. SMEs in growth industries that rely heavily on knowledge often prefer urban areas (Ferreira et al. Citation2016).

(f) Reactive and short-term management. Given the companies’ small size, lack of resources, and less functional division of labor, SME managers often focus on daily operations. As a result, they are often preoccupied with fire-fighting (Ramsey et al. Citation2013) rather than employing an effective, forward-thinking, modern management culture (Clark, Palaskas, et al. Citation2004; McAdam, McConvery, and Armstrong Citation2004; Meccheri and Pelloni Citation2006). As a consequence, a strong vision for the future is missing (Larsson, Hedelin, and Gärling Citation2003). Another potential reason for this managerial approach is the often-challenging economic situation in rural areas that keep the focus on the short-term, hardly allowing for visionary approaches.

(g) Specialized, often niche skills. While many rural SMEs operate in localized markets, this is only possible if the local market is big enough. In less populated and weakly industrialized rural areas, SMEs, particularly in manufacturing, can escape their limited local market by tapping into national or even international markets (Dubois Citation2016). As SMEs face many more competitors including bigger firms in these markets, however, they often need to differentiate themselves by focusing on niche markets. For rural and remote enterprises, such specialization can be a strategy to become subcontractors in regionally more extended value chains (Virkkala Citation2007) or to form regional clusters in industries such as high-quality manufacturing (Kiese and Kahl Citation2017). Specialized skills thus refer to specific industries or products such as in the case of an SME exporting high-tech magnifying lenses to medical professionals around the world (Müller and Korsgaard Citation2018).

(h) Ability to network. Given their strong spatial embeddedness, their more informal structures, and the personal ties of their family owners, SMEs in rural areas often display a particular capacity and ample experience in developing, using, and maintaining networks and other forms of collaboration. As collaboration is thus a key feature of SMEs in rural areas (Bjerke and Johansson Citation2015; Bürcher Citation2017; Dubois Citation2016; Korsgaard, Ferguson, et al. Citation2015; Salone, Bonini Baraldi, and Pazzola Citation2017; Stankovska, Josimovski, and Edwards Citation2016; Tregear and Cooper Citation2016), we will focus on this practice in much more detail below.

The particular internal and external factors that SMEs face in rural areas

Bringing together the spatial and enterprise perspective thus shows that there are both relevant internal and external factors that influence the economic venturing of SMEs in rural areas. Interestingly, many of these characteristics of rural SMEs and rural areas can have ambivalent effects: They can both result in advantages and disadvantages for SMEs. With regard to internal factors, take the example of the more informal management style. While informality often allows for easier ad-hoc collaboration in the rural community, it can be more reactive and less strategic. With regard to external factors, take the case of a strong cultural identity. While such an identity can be an important source of social capital that supports collaboration, it can also be status-quo oriented and hinder innovation.

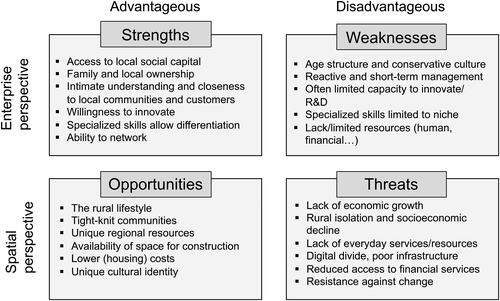

Put differently, the characteristics of rural SMEs and rural spaces can result in strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats for SMEs in rural areas. By this logic, summarizes our findings in form of a classic SWOT illustration. While in business practice a genuine SWOT analysis requires a careful investigation of the situational specificities, we use this SWOT illustration in a more figurative way to highlight important generic issues for SMEs in rural areas. Like any SWOT analysis, these results raise the question as to how a company can use its strengths and acknowledge its weaknesses in a way that mitigates risks and realizes opportunities. The following section presents the strategies that our SLR could identify in this regard.

5.3. Relation-based collaboration as an SME meta-strategy to navigate and operate in rural contexts

Our qualitative coding of the strategies SMEs use to address the particularities of rural contexts yielded a broad spectrum of diverse practices. Upon closer inspection and when merging the different codes, however, our findings suggest that almost all of these different strategies can be subsumed as variations of an overarching ‘meta-strategy’, namely networking and relation-based collaboration. Again, our results do not suggest that collaboration is a strategy exclusively used by rural SMEs. In fact, collaboration has been researched as a general SME practice to foster growth (Robson and Bennett Citation2000) or innovation (Cumbers, Mackinnon, and Chapman Citation2003). In the following, we map how this general role of collaboration is covered in our literature sample. More specifically, we review the following sub-categories: (1) forms of collaboration (How to collaborate?), (2) partners of collaboration (Who collaborates?) as well as (3) purposes of collaboration (Why do SMEs seek to collaborate?). This section will first present these findings before our discussion looks at how this strong focus of SMEs on relation-based collaboration relates to the SWOT analysis described above.

5.3.1. Forms of collaboration and networking

Networks can be private or public sector and can be formal, informal/ad-hoc networks or social networks (Arbuthnott and von Friedrichs Citation2013; Bishop Citation2011; Dubois Citation2016; Moyes, Whittam, and Ferri Citation2012; Smallbone, Baldock, and North Citation2003). In our literature sample, formal and informal networks were discussed most frequently.

Formal networks often operate as a ‘closed shop’ and membership is required. Especially in rural regions, all business owners know each other ((Dubois Citation2016; Moyes, Whittam, and Ferri Citation2012) as they regularly meet (Arbuthnott and von Friedrichs Citation2013). With formal networks the SMEs are able to ‘mobilise important market intelligence (e.g. bringing in new business, finding new markets, awareness of the competition, compliance with rules and regulations)’ (Dubois Citation2016, 7). Informal networks, in turn, often build upon long-term personal relationships and can thus draw on specific strengths of locally embedded SMEs. In sum, collaborative networks can be formal or informal, offline or virtual (Smith, Smith, and Shaw Citation2017), interpersonal or interorganizational (Idris and Saridakis Citation2018) as well as locally confined or reaching beyond the rural area’s boundaries (Müller and Korsgaard Citation2018).

5.3.2. Partners to collaborate with

There is a vast variety of potential collaboration partners for SMEs. The choice of partner very strongly depends on the resources needed by an SME. a) Clients: One potential partner are clients (Arbuthnott and von Friedrichs Citation2013; Bishop Citation2011; Jarvis and Dunham Citation2003; Martin, McNeill, and Warren-Smith Citation2013; McAdam, Reid, and Shevlin Citation2014; Moilanen, Østbye, and Woll Citation2014; Moyes, Whittam, and Ferri Citation2012; Reidolf Citation2016; Roper and Hewitt-Dundas Citation2013; Smallbone, Baldock, and North Citation2003) who mostly provide knowledge and expertise. In rural areas, customers tend to support SMEs more than they do in urban areas (Anderson, Osseichuk, and Illingworth Citation2010). For instance, through discussion with customers SMEs are able to create new marketing approaches, conduct market research or further develop their advertising (Bishop Citation2011). This is a so called ‘one-way knowledge-supply relationships’ (Roper and Hewitt-Dundas Citation2013, 288). Customers are able to co-design and specify products and manufacturing systems. These relationships are often very exclusive and of a long-term nature (Jarvis, Dunham, and Ilbery Citation2006; McAdam, Reid, and Shevlin Citation2014). b) Suppliers and supply chain partners can also offer access to relevant resources (Arbuthnott and von Friedrichs Citation2013; Martin, McNeill, and Warren-Smith Citation2013; McAdam, Reid, and Shevlin Citation2014; Roper and Hewitt-Dundas Citation2013). Supply chain partners can be a source of expertise and ‘advice as well as practical help that may increase the company’s competitive edge and strengthen its chances of winning business in other areas.’ (Jarvis and Dunham Citation2003, 254). Next to information needs, supplier collaboration can also address the lack of financial resources. SMEs often struggle to find or are hesitant to use debt from conventional banks. An alternative to debt and credit form financial institutions are trade credits (Deloof and La Rocca Citation2015). Here, SMEs receive loans not from banks but from their suppliers. Deloof and La Rocca (Citation2015) found that trade credit policy ‘plays a significant role in local financial development’ (922). In other words, trade credits help SMEs to overcome the challenges of rural isolation and the lack of everyday amenities by linking them more closely with their suppliers. c) Other companies: SMEs can also collaborate with other companies in the community. In rural settings, SMEs recognize that they are a part of the ecosystem and therefore relationships with other companies are important (Anderson, Wallace, and Townsend Citation2016; Jarvis and Dunham Citation2003; Smallbone, Baldock, and North Citation2003). These collaborations can lead to reduced costs or boosts in sales (Smallbone, Baldock, and North Citation2003). They can therefore help overcome financial resource constraints and sales challenges rooted in rural isolation. d) Schools and education: Research shows that SMEs build networks not only with business partners but also outside of business relations, for instance with local schools (Salone, Bonini Baraldi, and Pazzola Citation2017) which in some cases have existed for several decades (Bürcher Citation2017). These relationships with non-business actors help SMEs to access relevant resources. In the case of schools, SMEs can use these connections to improve their employer attractiveness and to attract potential future employees. Similarly, rural SMEs leverage local role models to inspire others to start companies to increase regional attractiveness. e) Research institutions and universities: Another potential collaboration partner are research institutions and universities (Benneworth Citation2004; Karlsen, Isaksen, and Spilling Citation2011; McAdam, McConvery, and Armstrong Citation2004; McAdam, Reid, and Shevlin Citation2014; Pinto, Fernandez-Esquinas, and Uyarra Citation2015; Reidolf Citation2016; Yoo, Mackenzie, and Jones-Evans Citation2012). University-SME interactions provide a wide range of services such as trainings, applied research, graduate recruitment (Karlsen, Isaksen, and Spilling Citation2011), and technology development (Yoo, Mackenzie, and Jones-Evans Citation2012). Collaboration with universities can further assist in technical development and commercialization which in turn can lead to expansion and growth (Benneworth Citation2004). f) Further actors: Our literature review also found the collaboration with business support agencies (Smallbone, Baldock, and North Citation2003), Non-Governmental Organizations (Harangozó and Zilahy Citation2015), trade organizations (McAdam, Reid, and Shevlin Citation2014; Moilanen, Østbye, and Woll Citation2014), and partners from personal networks (Moilanen, Østbye, and Woll Citation2014). Yet, these actors were mentioned with significantly lower frequency.

5.3.3. Purposes and motives for collaboration

Generally speaking, regional networks serve to exchange resources and business information as well as to participate in social activities (Arbuthnott and von Friedrichs Citation2013). On top, networks can be used to share experience (Herslund Citation2012). More specifically, we identify four concrete instrumental motives to collaborate: a) to foster innovation, b) to access non-financial resources, c) to access financial resources, and d) to access and to develop markets. a) Fostering innovation and knowledge exchange: For non-specialized or non-market leader SMEs, getting access to relevant knowledge is often a challenge. This is particularly relevant in rural areas. Here, the creation of networks and relationships serves to organize information flows that are needed to adapt products, skills, and processes. In this regard, particularly relevant collaboration partners include supplier and clients (to innovate and co-create products (Salone, Bonini Baraldi, and Pazzola Citation2017)) as well as research and education institutions (to transfer knowledge and innovations).

SMEs can collaborate with regional or extra-regional actors to gain access to or exchange knowledge (Tregear and Cooper Citation2016). What is particularly interesting is that knowledge-focused relationships are more common between SMEs and actors of different regions than those within a region (Bjerke and Johansson Citation2015). This seems to be due to the almost homogenous local culture and potentially limited knowledge base within a region (Bjerke and Johansson Citation2015; Ramsey et al. Citation2013; Reidolf Citation2016). b) Accessing non-financial resources and services: As SMEs have a limited resource base, they generally use collaboration to address this gap. In rural areas, however, adequate partners are often scarce. In fact, SMEs in rural areas often have limited access to manufacturing services (Jarvis and Dunham Citation2003), ICT services (Anderson, Wallace, and Townsend Citation2016) and especially human capital resources such as skilled labor (Fortunato Citation2014; Herslund Citation2012; Reidolf Citation2016). Against this background, rural SMEs try to use networks to find such partners and develop relations to secure these exchange relationships (e.g., though long-term partnerships with schools as discussed above). c) Accessing financial resources: Access to financial capital constitutes a common bottleneck for SME growth in rural areas due to rural bank closure (Fortunato Citation2014) and the concentration of financial institutions in bigger cities (Mercieca, Schaeck, and Wolfe Citation2009). Additionally, research indicates that conventional banks are hesitant to offer finance for SMEs in rural area (Price, Rae, and Cini Citation2013).

Against this background, our literature review found some, though limited, research on alternative sources of finance. These include trade credits (Deloof and La Rocca Citation2015), crowd funding, private equity funders, local authority loan funds (Price, Rae, and Cini Citation2013), joint public–private investments (Arbuthnott and von Friedrichs Citation2013), and venture capital (Avdeitchikova Citation2009; Klagge and Martin Citation2005; Meccheri and Pelloni Citation2006). Despite its potential promise for rural SMEs, most venture capitalists, however, are drawn towards high-tech enterprises (Avdeitchikova Citation2009; Klagge and Martin Citation2005; Meccheri and Pelloni Citation2006) which are more readily found in metropolitan areas (Avdeitchikova Citation2009). As a result, rural SMEs are often only able to access informal venture capital. Interestingly and in line with our argument, all of these instruments thus present relationship-based forms of collaboration such as informal venture capital or trade credits granted by long-term suppliers (Deloof and La Rocca Citation2015). d) Accessing, developing, and securing markets: Given the limited size of rural markets, SMEs cannot easily switch their local customer base. Building up long-term, relation-based collaboration with their clients can serve not only to jointly innovate and co-create (Salone, Bonini Baraldi, and Pazzola Citation2017) but to secure the customer relationship. At the same time, SMEs can use networks to find new customers and markets (Dubois Citation2016), both within and outside their rural context.

5.4. Gaps in existing research

Completing the idea of an SLR, we now use both the thematic and descriptive results to reflect upon two blind spots that invite future research.

5.4.1. Country focus of research and the problem of transferability

In our descriptive analysis, we identified a strong geographical focus (78 out of 228 publications) on the United Kingdom. This seeming overemphasis on the UK constitutes a challenge for SME studies as it is challenging to transfer findings from one country to another (Arbuthnott and von Friedrichs Citation2013; Anderson, Wallace, and Townsend Citation2016). Future research can therefore shed more light on other countries and/or engage in cross-country studies.

5.4.2. Lax definitions of SMEs

There is an ongoing debate and a lot of possibilities to define the term ‘small and medium sized enterprises’ (Klewitz and Hansen Citation2014; Loecher Citation2000; Welter, Smallbone, and Pobol Citation2015). Loecher (Citation2000) found over 200 different definitions of SMEs. This was a main challenge during the analysis of the 228 papers in our sample. For less than one in five papers did we find a clear definition of how the paper defined SMEs. The overwhelming majority, however, published their results on SMEs without defining the boundaries of the phenomenon. Just as in the case of strong country biases, this lax definition is a challenge for comparative analyses and for transferring insights between different research streams. We therefore encourage future research to be more explicit and transparent about how SMEs are defined.

6. Discussion

For brevity, our discussion engages with our thematic results in two ways: First, we use the resource-based view (RBV) and transaction cost economics (TCE) to develop a conceptual framework that brings together the enterprise and spatial perspective. Second, we discuss how digitalization impacts our results regarding SMEs in rural spaces.

6.1. A conceptual model of relationship-based collaboration of SMEs in rural areas

From the RBV (Wernerfelt Citation1984), firm competitiveness depends on the internal resource endowment of a company, thus highlighting the enterprise perspective. Seen from the RBV perspective, SMEs in rural areas face specific challenges because of their limited endowment with financial, organizational, personnel, knowledge, and other resources. In theory, companies can address such internal resource scarcity in various ways. If resources are mobile and can be traded, companies can use the market exchange to acquire valuable resources by buying machines, obtaining licenses, hiring highly skilled employees and others (Barney Citation1991). Linking the RBV with our spatial perspective, however, shows that the availability, mobility, and tradability of a resource does not only depend on the resource itself but also on the spatial context. If, such as in rural areas, markets are underdeveloped, certain resources not only become scarcer and more valuable but also less mobile and less tradable. Take the example of a highly skilled software engineer. In a big city, the software engineer might easily change her position and go from one SME to another because she does not have to relocate as the two SMEs are in the same area. In a rural context, in contrast, if the software engineer goes to another SME, this could be several villages away thus creating the need to either relocate or face long commutes. In effect, talent will then be less mobile. The spatial context thus affects not only the availability but also the mobility of resources.

If resources are immobile and cannot be traded in the market such as in the case of intangible assets, the RBV highlights a second option to nevertheless acquire the resource: Instead of buying the single resource, a firm can acquire the entire organization that holds it (Mahoney and Pandian Citation1992). Mergers and acquisitions, however, are a strategy typically reserved for bigger firms. Rural SMEs, in contrast, often lack the size and financial clout to buy other firms.

Against the background of these enterprise and spatial characteristics, rural SMEs are thus in special need to address resource weaknesses but cannot rely on conventional market exchanges. Taking a RBV perspective, we therefore suggest that the SME resource scarcity leads to the prominence of collaboration. Here, collaboration with other actors serves as a strategy to weaken internal weaknesses by gaining access to otherwise inaccessible resources.

While collaboration serves to weaken SMEs’ specific weaknesses, it is a strategy that builds upon SMEs’ specific strengths given their social embeddedness, informal culture, and family ties. Here, the RBV highlights that these assets are highly intangible and represent a resource that other actors cannot easily acquire or imitate.

Shifting our focus now to the spatial perspective, we suggest that TCE can add additional insights into why SMEs use relationship-based collaboration. TCE treats transactions as the basic unit of analysis with a transaction occurring ‘when a good or service is transferred across a technological separable interface. One stage of activity terminates and another begins.’ (Williamson Citation1981, 550). Transaction costs include search and information costs, bargaining cost as well as monitoring, policing, and enforcements. A key question for TCE is then to analyze how different governance solutions affect overall transaction costs. These governance solutions can fall on a spectrum where spot markets mark one end and hierarchy within an organization the other end. Hybrid governance solutions such as joint ventures, partnerships, relational contracts, and franchising then fall in the middle of this spectrum.

So where is the relevance of TCE for our spatial perspective? TCE highlights that the use of any governance arrangement has a cost. Our spatial perspective suggests that the specific characteristics of rural areas – their opportunities and challenges – significantly affect these transaction costs. To start with, the challenges of rural areas increase the costs of using conventional (spot) market mechanisms. As there are fewer options available, less specialization, and physically scattered market participants, search and information costs increase. Moreover, limited competition (e.g., among suppliers) means that there are fewer exit options (e.g., for their customers) (Hirschman Citation1970). The resulting increase in dependency and exchange specificity lead to higher need for contractual safeguards thus increasing the bargaining, monitoring, and enforcement costs of using the pure market organization (Williamson Citation1981). As a consequence, the specific challenges of rural areas create incentives to move away from pure market governance forms.

When looking at the opportunities of rural areas, on the other hand, various spatial characteristics result in a lowering of the costs of using hybrid governance solutions. As reviewed above, rural areas are often rich in relational resources such as a strong culture, shared identity, and tight-knit communities. Such pre-existing features render it much easier to rely on relational governance solutions such as networks, partnerships, and long-term supply chain relations where identity, history, and path dependencies matter. As a consequence, the specific opportunities of rural areas make it easier to use relational governance forms, thus explaining the prominence of relationship-based, long-term partnerships.

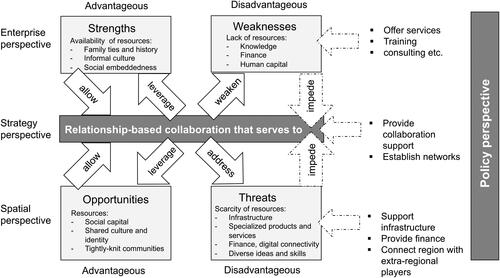

summarizes key elements of our analysis. The prominent use of relationship-based collaboration by SMEs reflects both the specific enterprise characteristics of SMEs and specific spatial characteristics of rural areas. In terms of disadvantageous factors, both SME weaknesses (their internal resource scarcity) and rural area challenges (the external resource scarcity) create a particular need for or push towards relationship-based collaboration to address these challenges. In terms of advantageous factors, both SME strengths and rural area opportunities put SMEs in a particular position to or create a pull towards relationship-based collaboration. Put differently, relationship-based collaboration allows SMEs to use their strengths and context opportunities to weaken their weaknesses and address their challenges. At the same time, collaboration allows them to leverage their strengths and opportunities.

Collaboration, however, is not a silver bullet. In fact, as our SLR analysis has shown, the very weaknesses of SMEs and challenges of rural areas pose barriers that can impede successful collaboration. Against this background, briefly sketches what policy makers can do to support rural SMEs. On the one hand, policy makers can try to directly address the shortcomings of SMEs and rural contexts. In the former case, support initiatives can provide training, for instance, to SMEs while, in the latter case, support initiatives can address shortcomings of rural areas e.g., by improving infrastructure. On the other hand, support initiatives can address barriers to collaboration by establishing networks, exchange fora, or bringing in extra-regional actors, thus supporting SMEs to address their challenges through collaboration.

6.2. The role of digitalization for SMEs and collaboration in rural areas

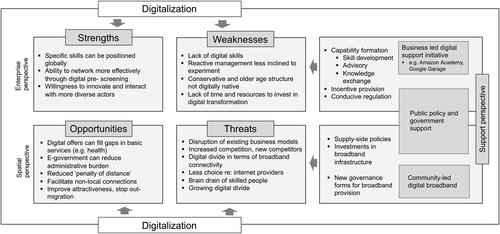

An important theme that emerged during our SLR is the increasing relevance of digitalization for SMEs in rural areas. As most of the articles that focus on this issue were published in the past few years, we did not include digitalization in our generic model above but separately discuss it as a recent development now.

For SMEs in rural areas, the digital transformation corresponds with both positive and negative implications. From a spatial perspective, broadband connectivity and ICT offer various opportunities for rural areas. On the one hand, digital banking, health, or education offers can address the lack of offline everyday services mentioned above as one of the threats of rural areas (Räisänen and Tuovinen Citation2020). Similarly, e-government can reduce the administrative burden for rural business (Ntaliani and Costopoulou Citation2018). On the other hand, digital transformation can favorably change the importance of place-based factors. Digital connectivity ‘can reduce the penalty of distance’ (Townsend et al. Citation2017) by bridging the spatial remoteness between rural and urban areas. For businesses, digitalization can facilitate non-local connections that allow ‘rural entrepreneurs to go beyond the local place in search of markets, partners and resources’ (Müller and Korsgaard Citation2018, 5). At the same time, digital business models can be home-based, thus offering employment opportunities for rural business (Reuschke and Mason Citation2020). Furthermore, Lundgren and Johansson (Citation2017) show in their work on ‘digital rurality’ that discourse on social media can create a positive narrative for a rural community. Here, digitalization thus strengthens existing advantages of rural areas such as tight-knit communities and a shared sense of identity. As a result, digitalization has raised hopes that its positive effects can bridge the rural-urban divide and stop the out-migration from the countryside (Briglauer et al. Citation2019).

However, the very process of digitalization also brings about significant threats for rural areas. On a more general level, digital transformation can disrupt existing business models. In addition, increased transparency intensifies international competition and brings in new competitors. On a more specific level, various papers in our sample put explicit emphasis on the ‘digital divide’ between rural and urban communities (Bowen and Morris Citation2019; Briglauer et al. Citation2019; Philip et al. Citation2017; Roberts et al. Citation2017; Salemink, Strijker, and Bosworth Citation2017; Räisänen and Tuovinen Citation2020). Rural areas have less broadband connectivity, limited mobile coverage, and fewer options when choosing their ICT provider (Ashmore, Farrington, and Skerratt Citation2017). Consequently, the digital divide results in various forms of socio-economic exclusion (Philip et al. Citation2017), often even more severely for vulnerable groups with lower education or higher age (Roberts et al. Citation2017). For businesses, a further threat lies in younger and skilled people moving to more digitally connected urban areas (Bowen and Morris Citation2019). Although the quality of digital infrastructure in rural areas does increase, the more dynamic development in urban areas results in the threat that the urban-rural digital divide continues to expand (Townsend et al. Citation2017).

What is important to note for our purposes, however, is that the digital divide does not only have a spatial but also an enterprise dimension. As Räisänen and Tuovinen (Citation2020) highlight, the rural-urban digital divide stems not only from the conditions of broadband and technology access but also from underdeveloped ICT skills, motivations, and usage (Salemink, Strijker, and Bosworth Citation2017). Digitalization thus encounters specific weaknesses of rural SMEs. In order to benefit from the potentials of digital transformation, SMEs need an adequate ‘digital orientation’ (Quinton et al. Citation2018). Yet, many rural SMEs lack specific digital competences or the time resources to engage with digital platforms (Styvén and Wallström Citation2019). Reflecting the general weaknesses of rural SMEs discussed above, many SMEs are rather reactive and hesitant to adopt digital technologies (Bowen and Morris Citation2019). As the age structure of rural SMEs is also often older, there can be an even greater distance to modern digital technologies.

Despite these weaknesses, an enterprise perspective on digitalization also highlights relevant strengths of rural SMEs. As discussed above, SMEs often have specific skills and use them in the digital age to position themselves in global markets (Dubois Citation2016). Moreover, as rural SMEs have a strong ability to network, entrepreneurs can use the Internet to screen potential collaboration partners, target contacts and thus make face-to-face encounter when traveling more effective (Meili and Shearmur Citation2019). By accessing non-local knowledge that increase network diversity, SMEs can also capitalize on their innovation skills and foster open innovation (ibid).

While the potential benefits of digitalization for rural SMEs are significant, the space- and SME-related challenge of the digital divide underlines that effective forms of collaboration and support are needed to realize opportunities and counter threats. Here, government and public agencies are an important partner. With regard to the spatial perspective, government can improve the situation of rural areas through dedicated investments into enhanced broadband connectivity (Briglauer et al. Citation2019). With regard to the enterprise perspective, government can implement demand-side policies in terms of capability formation such as skill development, advisory, knowledge exchange (Räisänen and Tuovinen Citation2020), incentive provision (e.g., financial support) or regulation such as the mandatory platform use for business SME users (Henderson Citation2020).

In addition to public actors, there are other potential collaboration partners regarding digitalization in rural areas. In a case study on Welsh rural SMEs, Henderson (Citation2020) found that non-government actors emerge as important providers of digital support. These potential collaboration partners include Google Garage or Amazon Academy where global digital firms cooperate with local and regional support structures. Potential partners also include universities and other education providers in order to address the lack of digital skills. Finally, as rural areas often need ‘customized’ digital infrastructure solutions that national ICT companies frequently cannot deliver, solutions can also emerge at the community level (Salemink, Strijker, and Bosworth Citation2017). Against this background, Ashmore, Farrington, and Skerratt (Citation2017) analyze various community-led broadband models where locally based solutions achieve superfast broadband. Here, rural SMEs can collaborate in tight-knit communities to actively address the digital divide.

In short, digitalization significantly changes the context for SMEs in rural areas in terms of space-specific opportunities and threats as well as SME-specific strength and weaknesses (see ). Digitalization offers SMEs new ways to leverage their strengths and to address their resource constraints. At the same time, digitalization changes the social construction of space by connecting rural areas with bigger cities and global markets or by allowing the production of community digital heritage.

Linking the increasing important of digitalization to our discussion about SMEs’ use of relationship-based collaboration opens avenues for further research. It raises the question of how digitalization will impact relationship-based collaboration. On the one hand, as digitalization reduces the costs of using the market and allows substituting formerly scarce resource, we could theorize that digitalization reduces the importance of relationship-based long-term collaboration. On the other hand, as digitalization reduces the costs of communication and can facilitate the creation of networks, we could theorize that digitalization will strengthen relationships and lead to an expansion of collaboration. In short, digitalization holds the potential to change the need and options for SME collaboration in rural contexts – a promising area for future research.

6.3. Limitations

There are several limitations of our SLR. First, like in any SLR, our results build upon a particular choice of key words, data bases as well as inclusion and exclusion criteria that other researchers might have chosen differently. To control for this subjectivity, we have regularly discussed these choices (and continuously refined them) in our research team and with the feedback of peer researchers. Second, as mentioned in our methodology, our exclusion criteria focused our analysis on SMEs in Europe. Therefore, our results might not be transferable to other regions, notably developing economies. Third, our research concentrated only on academic, peer-reviewed journals published in English. Due to its regional focus, research on SMEs in rural areas, however, might often be published in national journals in non-English languages. This might also explain our strong country bias towards the UK.

There are also limitations with regard to our qualitative content analysis. Qualitative analyses always face the challenges coming from the researchers’ subjective interpretations. We have tried to control this limitation through iterated discussions and the systematic use of content analysis software (MAXQDA). Nevertheless, given the breadth of data, the presentation of our findings was necessarily selective. While our results highlighted the prominent importance of relationship-based collaboration, there were other recurring themes in the literature that we could not feature in more detail. This includes, for instance, the importance of finance strategies that we only touched upon in passing. We therefore encourage future research to complement our analysis where our aggregated depictions were necessarily incomplete.

7. Summary and conclusion

What are relevant characteristics of rural SMEs and their spatial context and what is the general strategy for SMEs to operate in these specific conditions? To answer this question, this study conducted a systematic literature analysis to consolidate scholarly research on small and medium sized enterprises in rural areas. We analyzed 228 articles published in 108 academic journals over the period January 2003 to October 2020.

The descriptive results of our SLR show that while research on rural SMEs is increasingly evolving towards maturity and methodological diversity, there is a strong country bias towards the UK. Furthermore, SME boundaries are typically not defined explicitly thus rendering comparative research difficult.

Juxtaposing an enterprise and a spatial perspective, this paper has mapped relevant characteristics of rural SMEs and of rural areas. Bringing both perspectives together yielded a SWOT-like analysis that reflects the context for rural SME strategy. As a recurring meta-strategy, our qualitative content analysis identified relationship-based collaboration as a typical approach of SMEs to operate in rural spaces. More specifically, our SLR results served to map different forms, partners, and purposes of collaboration.

In our discussion, we interpreted the prominence of relationship-based collaboration in light of the enterprise and spatial characteristics analyzed above. Wedding the theoretical perspectives of the resource-based view and transaction-cost economics, we presented a conceptual model that shows that – given the enterprise characteristics of rural SMEs and the spatial characteristics of rural areas – SMEs are both in a particular need to draw on relationship-based collaboration and in a particular position to do so.

There are various implications for both practitioners and for future research. For practitioners, our results highlight not only the importance of collaboration but also of support structures to make it successful. Public actors can support collaboration through the establishment of networks, by bringing in extra-regional partners, and by serving as a partner themselves. SMEs can professionalize collaboration through dedicated project managers and the use of digital technologies. Future research can investigate how digitalization affects SMEs internally and the configuration of rural areas as socially constructed spaces. Moreover, as digitalization impacts both the need and options for collaborative long-term partnerships, future research can look into how digitalization changes how SMEs use collaboration to navigate the rural areas of the future.

Compliance with Ethical Standards & Funding

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).