Abstract

There is a widely-held belief that China’s high-performing entrepreneurs have been fueled by their transnational experience. Scholars have pointed to studying or working in the US, in particular, as a driver of their performance, while other researchers emphasize the ascent of place-based factors, such as the triple helix – the interaction of industry, government and academia – of leading cities as a bedrock for China’s entrepreneurship. In this paper, we examine the migration patterns of high-performing entrepreneurs, like Jack Ma, the founder of Alibaba, in order to test these competing hypotheses. To do so, we analyze the spatial mobility patterns of the founders of the Chinese high-growth companies that had raised at least US$1 billion in private equity funding as of March 2020. In contrast to the prevailing assumption that these high-performing entrepreneurs are returnees (e.g. Chinese entrepreneurs that lived abroad and returned to China), we find that, like Ma, this elite cohort are predominantly graduates with bachelor’s degrees from universities in urban coastal regions in China. Rather than transnational or location-based explanations, our findings point to sub-national migration patterns within China—to and within coastal urban areas—as more likely to drive entrepreneurial performance.

RÉSUMÉ

Une croyance largement répandue veut que les entrepreneurs chinois les plus performants aient été nourris de leur expérience transnationale. Des universitaires ont indiqué que le fait d’étudier ou de travailler aux États-Unis, en particulier, était un facteur de leur performance, tandis que d’autres chercheurs mettent l’accent sur l’augmentation de facteurs liés au lieu, tels que la triple hélice – l’interaction entre l’industrie, le gouvernement et les universitaires – des villes phares, comme base de l’entrepreneuriat en Chine. Dans cet article, nous examinons les modèles de migration des entrepreneurs très performants comme Jack Ma, le fondateur d’Alibaba, afin de tester ces hypothèses concurrentes. Pour ce faire, nous analysons les modèles de mobilité spatiale des fondateurs des entreprises chinoises à forte croissance qui avaient levé au moins un milliard de dollars de fonds privés en mars 2020. Contrairement à l’hypothèse dominante selon laquelle ces entrepreneurs très performants sont des rapatriés (c’est-à-dire des entrepreneurs chinois qui ont vécu à l’étranger et sont revenus en Chine), nous constatons que comme Ma, cette cohorte d’élite est principalement composée de diplômés de premier cycle des universités des régions côtières urbaines de la Chine. Plutôt que des explications transnationales ou basées sur le lieu, nos résultats indiquent que les modèles de migration infranationale en Chine – vers et dans les zones urbaines côtières – sont plus susceptibles d’être à l’origine des performances entrepreneuriales.

Introduction

There is an increasingly prevalent narrative that claims that high-growth entrepreneurship is an engine for social mobility. Such a narrative has been popularized by Jack Ma, founder of the e-commerce giant Alibaba, and one of China’s wealthiest men,Footnote1 and by America’s technology founders, such as Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, who have emphasized their humble beginnings when testifying to Congress. Jack Ma, in particular, has been forthcoming in sharing the failures that accompanied his path; he was rejected from 30 of the jobs he applied to after college, including one at Kentucky Fried Chicken (Wong Citation2016), and he was rejected from Harvard University ten times.Footnote2 Instead of Harvard, he was eventually accepted to study in his hometown of Hangzhou, at the Hangzhou Teachers College. Ma’s story has popularized the idea that anyone can achieve exceptional success. He is not the graduate of a top global university, and he learned English by listening to Voice of America, an American radio program broadcast in China rather than through experience as an overseas returnee.

In numerous ways, Jack Ma’s narrative is inconsistent with the advantages that recent research has found to be associated with high-performing entrepreneurs, especially in China. There is a large body of research exploring the distribution and determinants of entrepreneurial performance, in China in particular (see, for example, Zhao and Aram Citation1995; Troilo and Zhang Citation2012; Guo, He, and Li Citation2016; Farquharson and Pruthi Citation2015; Zhang and Zhao Citation2015; Lee Citation2018; Zhao and Ha-Brookshire Citation2018). Studies suggest that such business success is, to varying extents, determined by one’s possession of significant overseas-derived human capital, which comprises formal knowledge in terms of overseas university education, tacit knowledge, and formal and informal skills, and social capital, which comes from social networks and strong familial and political connections, amongst other sources (Hao et al. Citation2017; Liu Citation2016; Kenney, Breznitz, and Murphree Citation2013; Wang, Zweig, and Lin Citation2011; Batjargal Citation2007). On the other hand, emerging research instead points to place-based, institutional, drivers of entrepreneurial activity, such as the role of Chinese universities in urban settings as being positive determinants of entrepreneurial performance (Ahlstrom and Bruton Citation2002; Davidsson, Hunter, and Klofsten Citation2006; Bruton, Ahlstrom, and Li Citation2010; Lang, Fink, and Kibler Citation2014; Li, He, and Zhao Citation2020).

The question of whether transnational migration or local context is a stronger driver of entrepreneurial performance is what motivates this study. We focus on China, given the stark contrast between the narrative surrounding Ma’s hyper-local path in Hangzhou and the findings of existing research showing that diaspora entrepreneurs and China-born returnees, particularly those returning from the U.S., are prevalent amongst China’s high-performing entrepreneurs. Specifically, we ask: to what extent do place-based educational experiences in China or transnational migration experiences underpin the social and human capital of China’s high-performing entrepreneurs, like Jack Ma? To answer this question, we offer a nuanced way of studying migration patterns and entrepreneurial performance, by adding a third layer. We examine sub-national migration patterns, in addition to place-based and transnational levels. In doing so, we offer a preliminary step towards answering this question through studying the migration paths of high-performing entrepreneurs.

Our empirical focus is the migration of the founders of China’s most successful firms, at the level of cities, provinces, and countries, both within and outside of China. We analyze a novel dataset of the biographical details of the founders of the 75 privately established Chinese companies that had raised at least US$1 billion in private equity funding as of March 2020, according to CrunchBase.Footnote3 With this approach, we contribute to a growing body of research in economic geography, innovation studies, and entrepreneurship literature. Our foundation theory is social capital theory (Coleman Citation1998; Portes Citation1998; Putnam Citation1993; Bourdieu Citation1986), in which human and social capital of entrepreneurs are understood as key determinants of performance (Westlund and Bolton Citation2003; Granovetter Citation1973). Studies in this vein have examined founders’ familial relations (see Delmar and Davidsson Citation2000), social capital endowments (Renzulli, Aldrich, and Moody Citation2000; Westlund and Bolton Citation2003), social class (Mejia and Melendez Citation2012), and transnational migration patterns (Kenney, Breznitz, and Murphree Citation2013; Batjargal Citation2007) as drivers of who undertakes entrepreneurship and their performances.

In taking this approach, our paper offers three main contributions. Empirically, we provide a novel analysis of high-performing entrepreneurs in China, given our detailing and testing of sub-national migration patterns. Our point of departure from previous studies is distinguishing migration patterns within China, particularly coastal versus inland migration; in other words, we are studying migration at the sub-national, rather than only at the transnational level. We also offer an updated study of the social and human capital endowments of contemporary high-performing entrepreneurs; previous studies focused on high-performers working in the 1990s and early 2000s (Kenney, Breznitz, and Murphree Citation2013; Wang, Zweig, and Lin Citation2011; Batjargal, Citation2007), while our study focuses on high-performers as of 2021.

Second, we contribute to theory on entrepreneurial performance by going beyond the transnational and place-based explanations. We do this by conceptualizing and empirically demonstrating the importance of sub-national migration patterns in endowing high-performing entrepreneurs with relevant social and human capital. Third, methodologically we help to model the use of geographic information systems (GIS) visualizations in research on the relationship between entrepreneurship and social capital. We draw on advances in GIS software and visual research methods in the social sciences (Steinberg and Steinberg Citation2006; Lin Citation2020; McKinnon and McCallum Breen Citation2020) to distill and visualize the migration patterns of the high-performing founders as well as spatial patterns within and outside of China.

Through these contributions, we build on the strengths of previous studies that have examined the human and social capital of entrepreneurs with research that explains ‘flying geese’ patterns of industrial activity, in which competency and wage advances in one location fuel nearby advances (Zhou Citation2011; Ruan and Zhang Citation2014; Li Citation2016; Guo, He, and Li Citation2016; Zheng and Zhao Citation2017; Xu and Cao Citation2019) and research on place-based entrepreneurship and institutional theory (Lee Citation2018; Cheng et al. Citation2021). Overall, this helps us to advance the analytical and methodological tools available for examining the extent to which entrepreneurial performance is enabled by particular migratory patterns, especially certain coastal, urban areas related to a cluster of elite universities. Similar to Nazareno, Zhou, and You (Citation2019) and Zhou (Citation2004), we also strive to contribute to scholarship on the intersection of ethnic entrepreneurs, diaspora entrepreneurs, and migration.

The paper proceeds as follows. Next, we develop the social capital theoretical framework that guides the analysis, which is a combination of several contemporary approaches to explaining the relationship between social and human capital, geography and entrepreneurship. After this, section III provides an overview of the data and methods, specifically how we compiled and coded the location of educational and work experiences, as well as places of birth and residence, of the 75 founders. It also details the steps of our geographic information system visualization methods. Then the empirical section presents the findings. The empirical analysis details patterns in the rankings of universities attended as well as inland and coastal movements within China. It uses GIS software to show the visual patterns of sub-national and transnational migration.

In the discussion section, we then analyze the extent to which our two hypotheses, drawn from the extant literature, are supported. We discuss whether our first hypothesis, centering on whether ‘place-based entrepreneurship’ narratives like Jack Ma’s ‘made in Hangzhou’ narrative is in fact a common pattern, and second, we discuss whether our second hypothesis, centering on whether overseas experience, especially in the US, is in fact a common pattern amongst high-performing entrepreneurs in contemporary China. We conclude the paper with a discussion of what these findings mean to scholarly knowledge on the social and human capital determinants of high-performing entrepreneurship by outlining avenues of future research.

Theoretical framework: social capital, entrepreneurship, and migration

Social capital is determined by one’s social networks as well as study and work experiences and family characteristics (Bourdieu Citation1986; Coleman Citation1998; Portes Citation1998). Putnam (Citation1993: 35) defines social capital as ‘features of social organization such as networks, norms, and social trust that facilitate coordination and cooperation for mutual benefit.’ Studies on the impact of social capital on entrepreneurship tend to focus on the role of social capital in determining performance (Westlund and Bolton Citation2003; Delmar and Davidsson Citation2000; Renzulli, Aldrich, and Moody Citation2000). In the context of the role of social capital in accessing innovative entrepreneurship, specifically, Klingler-Vidra and Liu (Citation2020, 1034) assert that ‘without personal connections, and without indications of the ‘right’ experiences and networks, under-represented demographic groups may struggle to break into employment in innovative sectors.’

Research follows Granovetter’s (Citation1973) conceptualization of strong ties (deep, close connections via friends and family) and weak ties (more shallow or distant connections) to determine entrepreneurship activities and performance (Grabher Citation1993; Guth Citation2005). Engel (Citation2014) delineates the social capital endowments of a ‘cluster of innovation,’ noting that social networks and culture, amongst other elements, shape the relative advantages of the place. One’s ties shape access to financial resources, which are also key to determining their propensity to undertake entrepreneurial activities (Mejia and Melendez Citation2012), partly because family assets mitigate the risks associated with entrepreneurial investment and can serve as a safety net or unemployment insurance.

Scholars have also researched the relationship between social capital and entrepreneurship in terms of migration patterns. Studies of diaspora entrepreneurs (Nazareno, Zhou, and You Citation2019; Zhou Citation2004) and immigrant entrepreneurs (Camara Malerba and Ferreira Citation2021) examine the prevalence of such entrepreneurs and seek to explain why and how their migration experience may contribute to their entrepreneurial activities. In this vein, studies focus on where one attends university, and what social and human capital endowments accumulate as a result of living and studying at that location. This includes studies examining the prevalence of MIT graduates in the U.S. technology industry (Roberts 1991) and the prevalence of U.S. university graduates among internet-based entrepreneurs in China in the 1990s (Batjargal Citation2007).

By studying overseas, returnees are said to be better equipped for ‘opportunity identification’ when they return home, as they are more alert to new business opportunities (Zhou, Farquharson, and Man Citation2016). Klingler-Vidra, Tran, and Chalmers (Citation2021) also find that transnational experience is prevalent amongst Vietnam’s burgeoning set of high-performing tech founders. They go on to explain that this stems from homophily—broadly understood in the context of entrepreneurship as a tendency for people to (often subconsciously) hire and invest in people similar to themselves (Parker Citation2009)—and related affects, which mean that venture capitalists value Vietnamese returnees from the U.S. as they, themselves, are also either returnees or foreigners (Klingler-Vidra, Tran, and Chalmers Citation2021: 7). To be sure, the experience of studying and working in the U.S. leads to returnees developing new skills related to identifying potential gaps in a market in their home country.

The second strand of literature focuses on transnational migration as social capital, for instance, with contacts and networks accumulated from overseas educational and/or entrepreneurial experiences (Troilo and Zhang Citation2012; Guo, He, and Li Citation2016; Zhang and Zhao Citation2015; Zhao and Ha-Brookshire Citation2018; Brzozowski, Cucculelli, and Surdej Citation2019). Notably, Kenney, Breznitz, and Murphree (Citation2013) find that many overseas returnees, after obtaining university degrees in the United States, went on to become founders of technology companies in China, India and Taiwan, part of a highly-successful second wave of such companies, following an initial group of domestically educated and experienced entrepreneurs who first achieved momentum in this sector. Studying at elite universities, such as MIT, or Harvard University, is associated with the production of social elites in the business and political spheres (Bloch et al. Citation2017). Thus, it is not only the curriculum or technical know-how, but also a way of thinking and social network that come from university experience.

In the Chinese context, such U.S.-obtained social capital has been said to be important in propelling positive entrepreneurial performance through the creation of ‘structural holes’ – the absence of a link between actors – in one’s social network (Batjargal Citation2007). Structural holes typically have a negative connotation, as the missing links between actors can mean that actors cannot access network resources. However, structural holes in the networks of entrepreneurs with transnational experience have been found to be valuable as they orient actors towards ‘new information, opportunities and resources’ (Batjargal, Citation2007, 606). In contrast, in their systematic review of scholarship on Chinese returnees, Hao et al. (Citation2017, 147) discuss the trade-off between returnees and locally-derived networks in China, noting that success was often determined by ‘whom he or she knows. This would be a disadvantage for returnees since many lose their domestic guanxi after years of overseas experience.’ Thus, there is debate in recent scholarship as to whether overseas experience—whether for education or otherwise—is an asset for Chinese entrepreneurs in terms of their social capital accumulation.

The last strand of literature highlights the importance of place-based resources, infrastructures and institutions in explaining the presence and performance entrepreneurship (Yang Citation1994; Ahlstrom and Bruton Citation2002; Westlund and Bolton Citation2003; Peng Citation2004; Davidsson, Hunter, and Klofsten Citation2006; Bruton, Ahlstrom, and Li Citation2010; Lu and Tao Citation2010; Lang, Fink, and Kibler Citation2014; Su, Zhai, and Landstrom Citation2015). Akin to the ways in which research into why and how transnational migration boosts the accumulation of social and human capital conducive to high-performing entrepreneurial activity, institutionally-focused research often examines the nature of the locale’s social capital as a determinant of activity (Westlund and Bolton Citation2003; Engel Citation2014). The nature of a locale’s social capital, that is, the particular strong and weak ties across the ecosystem (Granovetter Citation1973), shapes the innovativeness of the place (Akcomak and ter Weel Citation2009) as well as which demographic groups are included (Klingler-Vidra and Liu Citation2020).

In the Chinese context, research findings emphasize the geographical advantages of pre-existing clusters of entrepreneurial networks and human capital within China (Nee and Opper Citation2012). Research on the spatial distribution of entrepreneurship in China reveals which locales are most likely to generate the largest number of successful entrepreneurs. Zheng and Zhao (Citation2017), for instance, study China’s economic and population census data and find that there is a positive relationship between city size and entrepreneurial activity. This can be explained by place-based resources, infrastructures and institutions. Liu’s research highlights geographical patterns of the distribution of higher education institutions (Citation2015); in particular, coastal urban areas have significant advantages of clusters of universities and investment in R&D by the local governments (Ang Citation2016).

In turn, such place-based resources and opportunities are further translated into advantages of attracting and retaining highly-skilled labor forces and new entrepreneurs (Li, He, and Zhao Citation2020). This suggests that would-be founders who create businesses in cities in which there is already a density of same-industry firms have an advantage. This is a version of the flying geese logic, where industrial activities move in clusters according to regional advantage; rather than the advantage being one related to cost, in the context of flying geese for high-performing entrepreneurial talent, it is the density of local technological talent that determines the pattern.

Drawing together these different strands of the extant literature, there are effectively two sides of an ongoing debate about which experience sets, especially in terms of location, better drive entrepreneurial performance. We test these two competing hypotheses about the spatial patterns of the founders of China’s high-performing businesses. First, developing from the logic of place-based advantages that entrepreneurship is boosted by locally-specific social and human capital endowments in coastal cities, our first hypothesis is that it is university experiences in specific cities, or clusters, within China that is fueling the performance. China’s elite cohort of entrepreneurs, then, is expected to have largely been educated in coastal urban areas in China with growing ‘triple helix’ ecosystems of industry, government and university collaborations (Cheng et al. Citation2021). Relatedly, according to recent findings on the spatial distribution of entrepreneurship in China, we expect that entrepreneurs come from coastal urban areas with human and social capital advantages, for instance, Shanghai and Shenzhen (Zheng and Zhao Citation2017; Giulietti, Ning, and Zimmerman Citation2012).

Hypothesis 1: China’s high-performing entrepreneurs are more likely to have attended universities in China’s coastal urban areas, and then to have founded their businesses in the same city.

In contrast, hypothesis 2 is that transnational migration, and the social and human capital endowments that stem from those experiences, predominantly underpins this cohort of elite entrepreneurs. If established studies on the Chinese case, such as Batjargal (Citation2007) and Kenney, Breznitz, and Murphree (Citation2013) still hold true, then these high-performing entrepreneurs have, in large part, studied overseas, and that overseas experience endows them with world views, technical know-how and/or social networks that enable their entrepreneurial activity.

Hypothesis 2: China’s high-performing entrepreneurs are more likely to be returnees who have studied, and/or worked, in the United States, and then returned to China to establish and grow high-performing businesses.

In order to test for these two competing hypotheses that emanate from state-of-the-art literature on the relationship of migration patterns and entrepreneurial performance in China, we examine migration patterns both within China, and transnationally. This helps us to determine which types of migration movements are most associated with this elite cohort of entrepreneurs.

Material and methods

To investigate the patterns of human and social capital accumulation amongst high-performing entrepreneurs in China, we first identified the set of China’s most successful, privately-established businesses, as consistent with the approach taken by Klingler-Vidra, Tran, and Chalmers (Citation2021) and Kenney, Breznitz, and Murphree (Citation2013). We operationalized this by setting search filters in the CrunchBase database for the China-headquartered companies that had raised at least US$1 billion in equity funding as of March 2020. This produced an initial list of 101 companies. We exported the following data for each company: the firms’ date of founding, headquarters city, company structure, and business or sector category. We complemented the CrunchBase data with a bilingual (Chinese and English) search of press releases and companies’ websites to gather further company information.

We used the exported and supplementary data to verify that these companies were indeed active and independently founded in China. We applied four filters to do this. First, we disqualified companies on the basis of being established by a government entity. In this process, 10 companies were excluded as they were originally founded by a state body, such as China Unicom, which was founded by the Ministry of Railways, the Ministry of Electronics Industry, and the Ministry of Electric Power Industry in 1994.Footnote4 Our second filter is that of Chinese ownership; if companies were not ultimately owned by a Chinese parent company, they were excluded. This led to three companies—OLAM International, Uber China, and WeWork China—being removed from the dataset on account of these companies being foreign-owned. The third filter was for being a subsidiary of a Chinese company, as we wanted to be sure to not double count the subsidiaries (and thus founders) on the list. This led to 16 companies—including the various subsidiaries of JD—being filtered out.Footnote5 The fourth filter was for current operating status, in order to avoid the inclusion of companies that have gone into bankruptcy. This last step led to the filtering out of two companies.Footnote6

Once the set of companies was established, we then identified all of the founders of these 68 companies. As some of the firms were founded by more than one entrepreneur—Tencent, for example, has five co-founders: Charles Chen, Chenye Xu, Jason Zeng, Pony Ma and Zhidong Zhang—the total number of founders identified was 82. However, information about some of these founders was not available, and so the total, final number of China’s high-performing entrepreneurs for which we could gather biographical data is 75.

We collected and coded the biographical details of each of these 75 founders (see Appendix for full list of founder names and companies). This data was gathered through English and Chinese sources, beginning with LinkedIn and including media coverage, alumni and alumna news report from the alma mater, public speeches and talks, Baidu Baike (an online Chinese-language encyclopedia similar to Wikipedia), Quora, and Zhihu (a Chinese service similar to Quora). Across these sources, we mapped personal details, such as date of birth, age and gender. To ascertain the spatial distribution and migration patterns of these elite entrepreneurs, we gathered data on their hometown (the city where they were raised) as well as the location of their university degree at four levels: Bachelors, Masters, MBA and PhD. We coded education with the following: the university name, location (city and country) and the ‘coastal versus inland’ dimension for Chinese universities, in order to test for hypothesis 1. Finally, each university attended was coded with its global ranking, according to the 2020 ARWN (Academic Ranking of World Universities).

To test hypothesis 2 about the prevalence of returnee status, we also coded whether each founder is a returnee on the basis of their experience in Education, Academia, or Business, the location (country) of this experience, as well as when and how long (number of years) they were abroad. There are two approaches to define hai gui, either using a broad or a narrow definition. In the broad definition, the designation would include anyone who stays overseas (by study, work, and living) for any period of time that is not simply a short holiday. The narrow understanding of returnee (called hai gui, or ‘sea turtle,’ in Chinese) refers to the category that is regulated by China’s Ministry of Education, for students who study overseas and receive particular benefits upon their return, such as the right to settle in and register a residence (hukou) in a major city, as well as entrepreneurial support. To achieve this narrow hai gui status, students must stay or study at least 360 days overseas accumulatively. In our study, we use this broad definition of the time necessary to be considered a hai gui, in order to comprehensively capture the returnee phenomenon. Thus, we count anyone spending at least four months living abroad as a returnee, as we wanted to be sure to capture any and all overseas patterns. This allows us to be as comprehensive as possible in measuring and testing the prevalence of transnational experience amongst this sample of high-performing entrepreneurs, and thus, best positioned to test hypothesis 2.

Finally, in order to offer a geographic information system (GIS) visualization of the migration patterns of the founders, we conducted a series of steps (in line with state-of-the-art GIS visualization methods as discussed in Lin (Citation2020) and McKinnon and McCallum Breen (Citation2020). We began by ensuring that the panel data that we collected for each founder at each life stage (e.g. location at birth, Bachelor’s degree, etc.) was standardized according to the Geo Names Server (for Chinese locations) as provided by the Chinese Geographic Information Professional Knowledge Service SystemFootnote7 and the NGA GEOnet Names Server (for international locations) provided by the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency.Footnote8 All the geographic nodes were identified by their internationally standardized longitude and latitude.

We then used the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP)’s Environmental Data Explorer,Footnote9 a standardized open-source platform of geospatial data sets, to obtain a world map template, and the National Catalogue for Geographic Information,Footnote10 from the Chinese Ministry of Natural Resources, to obtain a Chinese map. After completing these two steps, we obtained latitude and longitude data for all the geographic locations in our panel data, and mapped these onto the templates for China and the globe.

The above data were then imported into ArcGIS, a GIS software package.Footnote11 This includes the geographic nodes for each stage (start point longitude, start point latitude, end point latitude) and the Chinese and world map templates used for visual representation. At the same time, we aligned the layers within the GIS system, including geographic alignment, geo-layers, visual elements (symbols, symbol attributes, arrow attributes, linear attributes, vector factor, etc.). It should be emphasized here that we chose the Rhumb Line (also known as Loxodrome) as our indicator for the linear attributes of the arcs in order to make the visualization appear natural. After the basic system settings, we choose to produce GIS geographic information images. The icons produced clear representations of the spatial trends, and patterns for each entrepreneur, from the birth place, their original hukouFootnote12, their current hukou, their various stages of education (domestic and foreign), and the location of their company headquarters.

Empirical results

Given our interest in the extent to which this elite cohort demonstrates particular spatial migration patterns via-a-vis their university studies, we examined whether these founders studied at Chinese universities or abroad. Through this examination of the country location for university studies, we found that nearly all of these founders (92%) conducted some level of university studies in China, with only six (8%) having no experience at a Chinese university across the Bachelors, Masters, MBA or PhD levels. In fact, and related to the greater range of rankings of universities at which Bachelor’s degrees were obtained, Bachelor’s degrees were almost exclusively obtained in China.

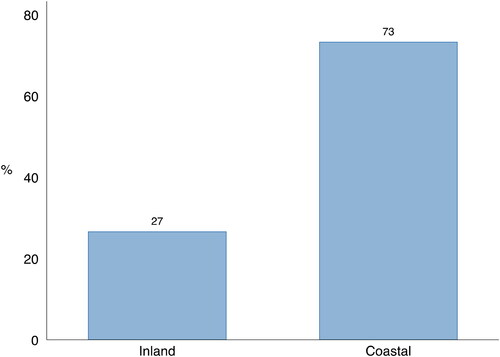

Thus, like Jack Ma and his Hangzhou Teachers College, hypothesis 1 is supported by data, as most of the successful founders completed their Bachelor’s degree in China. Through this sub-national migration examination, we found that the overwhelming majority of founders attended universities located in China’s large and wealthy urban areas on the coast, such as BeijingFootnote13, Shanghai, and Shenzhen. shows that more than 70% of founders completed their Bachelor’s degrees at universities located in coastal, urban China.

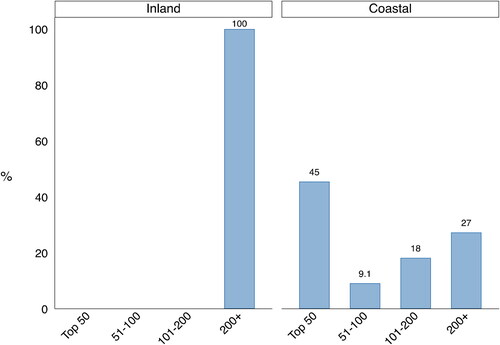

Again, we are interested in investigating these patterns in light of their relation to the potential for social mobility. Given existing studies on the differential opportunities available for those coming from coastal, urban centers and inland and rural contexts, we examined the extent to which there is a relationship between the spatial distribution of universities attended and the rankings of these universities in terms of their coastal vs. inland location. As illustrates, especially at the master’s degree level, this elite set of founders often attended top tier, coastal universities—especially the top 50 and top 100—while the universities more than about 300 kilometers from the sea tend to be ranked below the top 100 globally.

Figure 2. Ranking by coastal versus inland location of Chinese university studies completed (for Masters’ degrees).

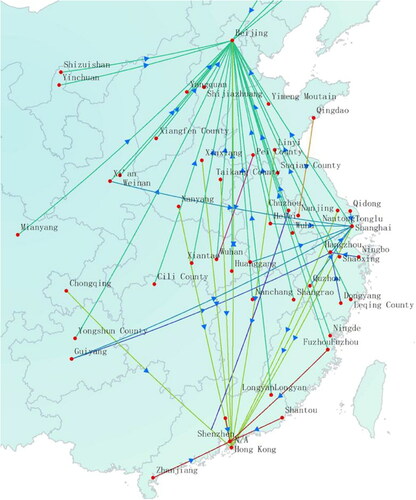

These are noticeable patterns, which can be visualized spatially using GIS software. Using GIS software and the settings outlined in the Data and Methods section above, in we visualize the sub-national migration patterns of the high-performing founders in terms of their hometown, or place of birth, the location of their hukou, to the place where they establish the headquarters of their company in China. As illustrates, there is a clear pull towards the coastal, urban regions, particularly Beijing, and, to a lesser extent, Shenzhen.

Figure 3. Spatial visualization of hometown to company headquarters hukou (amplified).

Source: Visualization of author’s data on founders’ hukou status in terms of hometown and headquarters city of their company using ArcGIS, a GIS software program. The arrow directions indicate movements from hometown to company headquarters location. The trajectory lines of each of the five major destinations are coded by color: (1) Ordinary Green Line indicates the hukou migration to Beijing; (2) Light Green Line, to Shenzhen, (3) Dark Green Line, to Shanghai, (4) Red Line to Hong Kong, and (5) Purple Line to Hangzhou.

Migration patterns to Shanghai, Hong Kong and Hangzhou are visible, but less pronounced. Overall, the graphic illustration shows that the founders of China’s highest-performing startups tend to move from one coastal, urban area to another, and to a lesser extent, migrate from inland regions to the coastal cities.

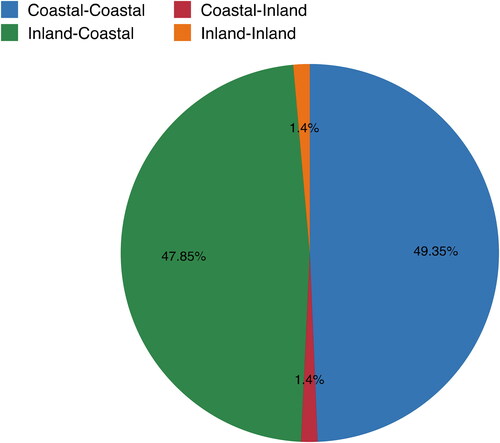

To test the sub-national dimension of hypothesis 1, we coded each founder according to (1) whether they moved at all, and (2) which type of move they made, in terms of the inland-coastal dichotomy. Through this, we found that 88.4% of founders moved away from their hometown. As such, only 11% were place-based ‘like Jack Ma’ in the sense that they grew up, attended university and then established their high-performing business all in the same city. But, also like the Alibaba founder, seven out of the eight founders who stayed in the same city, did so in a coastal city.

Strikingly, we found that 47.8% moved from inland to the coastal region, and 49.3% moved from one coastal, urban area to another. As visualized in , collectively just 2.8% of the founders made a move within the inland region, or from the coast to inland. This data shows that high-performing entrepreneurs often reside near the coast; and in fact, many of them are born and study near the coast. This data also shows that migration is likely to occur over the founder’s lifetime, and that such founders they are overwhelmingly likely to migrate to an urban, coastal region for university and then stay there. We hypothesize that this is done in order to build both their social and human capital, and then accordingly, build their business.

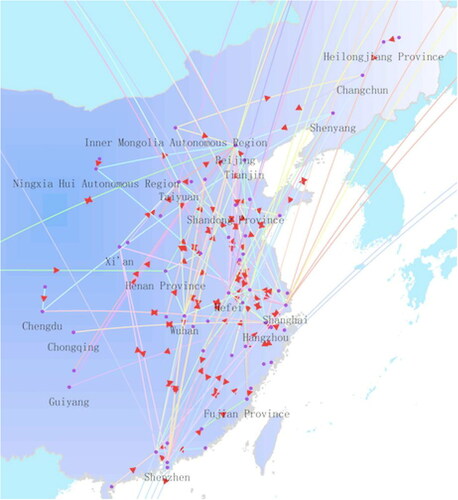

To interrogate the timing of the movements, given the expectation that the location of one’s university education may have a bearing on further opportunities, we delineated moves to these locations according to five stages. First, a move to complete the bachelor’s degree, second, a Masters, third, an MBA, fourth, a PhD, and finally, a move to establish the company headquarters. These movements are illustrated in , below, using GIS software to visualize the migration patterns from the place of birth to places of education (at the Bachelors, Masters, MBA and PhD levels), to the business headquarters. Points with an outward arrow indicates the place of birth (beginning stage) while points with an inward arrow indicates the location of the company headquarters (final stage). To be more precise, ’s line colors indicate the life stage of the movement, with orange as Undergraduate, green corresponding to Masters, yellow as MBA, blue as PhD, and purple as a move to establish the company headquarters.

Figure 5. Hometown to Universities to Headquarters (in China, amplified).

Source: Author’s representation of founder hukou and educational data, and company headquarter data, using the GIS software program, ArcGIS.

has a large number of orange lines, suggesting a large share of moves to complete a Bachelor’s degree, and then yellow, green and blue lines, indicating moves for postgraduate studies, but it has relatively few purple lines. This is an important finding as it suggests that founders—by and large—do not move to establish their businesses, but rather, that they set up businesses in the cities where they study.

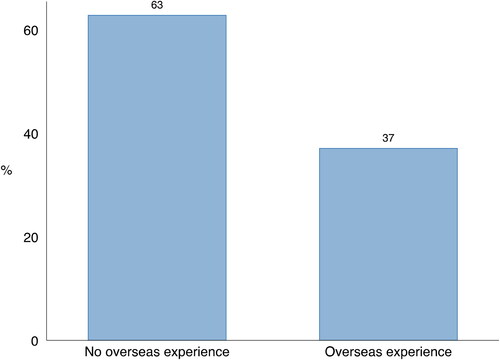

Finally, to test hypothesis 2 about the prevalence of transnational migration patterns, we then examined migration patterns in terms of the occurrence of hai gui, especially those returning from the US. Even with the broad definition of the time spent abroad in order to be considered a returnee, in which anyone who had spent just four months living overseas was counted, 63% of the founders were so-called ‘ground beetles,’ meaning those that had not lived overseas. Only 37% were hai gui. Said another way, the majority of the cohort (63%) had no overseas experience at all, whether in academia or business, as illustrated in below.

Thus, in contrast to the prevailing belief that China’s high-performing entrepreneurs are returnees who were exposed to US entrepreneurial practices, we did not find support for hypothesis two. The dominant migration pattern of contemporary high-performing entrepreneurs in China is, rather, within China.

When we look at the destination of the 37% who did go abroad, though, we see a clear pattern, and one that is mostly consistent with Batjargal (Citation2007), Wang, Zweig, and Lin (Citation2011) and Kenney, Breznitz, and Murphree (Citation2013). Of the hai gui, 20 (more than 71%) of those founders who lived overseas at some point, spent their overseas time in the United States. Hong Kong, the second most popular destination, attracted just three (approximately 11%) of the hai gui. Thus, while returnees are sparse amongst this cohort, there is evidence that those who did live abroad, tended to go to the United States. The educational level for which they migrate to the U.S. is typically postgraduate, either to complete a master’s degree or PhD, rather than a bachelor’s degree. We hypothesize that these individuals spend years developing disciplinary and sector expertise through their postgraduate studies in the U.S. in order to accumulate human capital as well as a transnational social network.

Discussion

There are aspects of the place-based entrepreneurship narrative, epitomized by Jack Ma, that are consistent with hypothesis 1. We found that such entrepreneurs are, almost entirely, graduates of Chinese universities, at least for their bachelor’s degrees, as 92% of the cohort obtained at least one degree at a Chinese university. What’s more, they are overwhelmingly graduates of universities in coastal urban areas, akin to Jack Ma’s graduation from Hangzhou Teachers College. The Jack Ma narrative is also relatively consistent with the evidence of returnee status amongst the cohort. Ma is one of the 63% of the so-called ‘ground beetles’ in this cohort, whereas just over one-third of the founders spent at least four months living overseas, whether for education or work.

Thus, in contrast to hypothesis 1, we found that China’s elite founders are not overwhelmingly likely to be graduates of U.S. universities, as Batjargal (Citation2007), Wang, Zweig, and Lin (Citation2011) and Kenney, Breznitz, and Murphree (Citation2013) found when examining previous sets of high-performing entrepreneurs in China. Instead of attending U.S. universities, more than 70% graduated from China’s highly-ranked coastal universities. This suggests that the accumulation of place-based human and social capital, on account of attending university in an urban, coastal region, is the predominant path of high-performing entrepreneurs in contemporary China. Tsinghua University, in Beijing, can alone count 10% of this cohort as alumni. Thus, it is China’s highly-ranked, and located near to the coast, universities that constitute the social and human capital foundations of this set of high-performing entrepreneurs, more so than studying and building social networks at top-ranked oversea universities. The prominence of sub-national migration patterns, and the place-based entrepreneurship that ensues, suggests that overseas experiences are not needed for ‘opportunity identification,’ as Zhou, Farquharson, and Man (Citation2016) found.

The picture changes somewhat when examining the spatial dimension of postgraduate studies, as the cohort members studied abroad, at U.S. universities, at a greater rate for their master’s, MBA and PhD degrees. However, they do not only study at top-ranked American universities near the coasts, as just one of the founders (Yibo Shao) graduated from Harvard, and one graduated from Stanford (Victor Koo), both with MBAs. This underscores the notion that the development of social and business connections (guanxi) in China, and especially amongst elite universities in populous coastal cities, is of great value in building a successful business. In short, sub-national migration patterns within China matter. While the direct influence of U.S. education appears to be less pronounced, the absence of any American influence should not be overstated. Studies suggest that U.S. universities maintain a significant presence in China through the way that graduates have established curriculum and institutional practices based upon their U.S. experience when they return to China (Li Citation2016).

How does this study of spatial mobility and high-performing entrepreneurs in China compare with findings of similar cohorts elsewhere? In the American context, studies of high-performing technology ‘unicorn’ entrepreneurs and venture capitalists reveal striking patterns, with Stanford and Harvard university’s being major producers (Parker Citation2020) of such individuals. The prevalence of Stanford graduates in the American high-technology sector, in particular, has been consciously constructed as Stanford management sought partnerships with firms that would hire their alumni (Adams Citation2005), and then, Silicon Valley firms actively courting Stanford graduates (The Economist Citation2019). Stanford attracts students who stay in Silicon Valley to work and found startups in a way that Tsinghua University is doing in China.

But studies on the migration and studying patterns of high-performing entrepreneurs in emerging technology hubs find that overseas experience or immigration play a more central role. In Israel, for instance, the success of new immigrants as founders of high-technology startups in the country’s ascending technology sector in the 1980s and 1990s is well-trod. Highly-skilled Russian immigrants took the risk of building disruptive technology startups, many of which listed on Nasdaq, beginning in the 1990s (Senor and Singer Citation2009). In a recent study of Vietnam’s high-performing entrepreneurs, Klingler-Vidra, Tran, and Chalmers (Citation2021) find that founders of Vietnam’s technology-oriented startups are 35 times more likely to be returnees from American universities than the founders of high-performing, but non-technological, businesses. In a technology clusters’ ascent, then, overseas experience, including at elite U.S. universities in particular, seems to be a feature, as Batjargal (Citation2007) and Kenney, Breznitz, and Murphree (Citation2013) found in their earlier studies of China’s growing technology sector.

The fact that China’s top entrepreneurs, as of 2021, are graduates from highly-ranked, coastal universities in China, is suggestive of the country’s maturation, especially in the social and human capital derived from attending its world-class universities, and living and working, in these cities fueling entrepreneurial performance. Previous cohorts may have felt they needed to go overseas to study (Liu et al. (Citationforthcoming) suggest that elites still express preferences for studying abroad), in order to foster such opportunity, but for elite entrepreneurs in China today, human and social capital accumulated through studying at top national universities, in leading coastal urban areas, is now the predominant path. This offers further evidence of the impact of China’s highly-ranked universities’ embeddedness in the talent pools of the urban areas of Beijing, Shenzhen and Shanghai (Li, He, and Zhao Citation2020). The returns of studying at these universities persist well beyond the curriculum, instead onto entrepreneurial performance later on in the same place. This is also added indication of the disadvantage of those completing their university studies in inland and Eastern locales, building on Liu’s (Citation2015) findings. Entrepreneurial outperformance is less available to those who choose to complete their bachelor’s degree at a university located inland.

Conclusion

Based on our data, China’s highest-performing entrepreneurs largely tend to follow sub-national migration patterns, moving to urban, coastal cities for university and then staying in these cities to build their businesses. Existing research had two lines of findings, and two contrasting sets of hypotheses; the first hypothesis, according to place-based entrepreneurship, emphasizes the role of the local universities, government and industry and other institutional settings, expecting that China’s high-performing entrepreneurs accumulated social and human capital through being embedded in a local cluster of innovation. The second hypothesis was drawn from the extant literature on transnational entrepreneurs, in which high-performing, high-technology entrepreneurs, especially in China, are expected to be overseas returnees, and graduates of U.S. universities in particular, who have benefited from their American education, business sense, and transnational social networks.

In this paper, we tested these two sets of hypotheses. More specifically, we examined the extent to which the contemporary cohort of China’s highest-performing entrepreneurs, the founders of the companies that had raised at least US$1 billion in equity funding as of March 2020, best correspond to either the transnational migration trajectory or more local patterns of mobility. We found that China’s highest-performing contemporary entrepreneurs, including Jack Ma, are not exclusively graduates of American universities, nor are they the hai gui that have been touted as boosting China’s second wave of its technology sector (Kenney, Breznitz, and Murphree Citation2013). Instead, many of these high-performing entrepreneurs obtained bachelor’s degrees from highly-ranked, coastally-located Chinese universities such as Tsinghua and Peking universities, and stayed in that city to ultimately establish their business.

They are, in this way, so-called ‘ground beetles,’ or local entrepreneurs, more often than they are so-called ‘sea turtles,’ or returnee entrepreneurs. However, they do not necessarily stay in their hometowns, as Jack Ma has in Hangzhou, the hukou where he was born, educated, and founded his world-leading company. Instead, our GIS visualizations showed that the majority of China’s top entrepreneurs (88%) make sub-national moves for their university education, obtaining degrees in China. Those who begin their lives and careers in inland regions tend to move to coastal, urban areas, particularly Beijing and Shenzhen. Those born in other coastal areas also move, but to other coastal, urban centers rather than inland. In fact, more than 97% of the founders who moved do so within or to the coastal region; just two founders stayed or moved inland. Only eight of the founders stayed in their hometown, as Jack Ma did in his coastal hometown of Hangzhou. These few who stayed in their hometown almost entirely started out in a coastal, urban area (only one such founder started and stayed inland).

One of the avenues for future research is to further investigate the drivers of entrepreneurial performance as a result of studying at a coastally-located university. Research can interrogate whether it is primarily a matter of entrepreneurial education (Kariv, Cisneros, and Ibanescu Citation2019), work experience, and informal and formal skills—i.e. so-called human capital—or if it is the accumulation of relevant social capital that is enabling performance. In Valdes (1995), the ‘Chicago Boys’ effect was fomented through socializing at parties while together at the University of Chicago, rather than through classroom curriculum per se. To understand what is driving the positive relationship between coastal university attendance and entrepreneurial performance in China, qualitative studies can interrogate the extent to which it is the human or social capital that is driving the outcome. Similarly, research can delve further into the functioning of China’s triple helix complex of universities, government and industry collaborating in these coastal, urban centers, to delineate how the local context endows valuable social capital in these clusters of innovation (see Engel Citation2014).

Finally, future studies can examine how these migrant entrepreneurs—coming from across China and, to a lesser extent, returning from abroad—are involved in community building in the urban centers where they grow their businesses (Zhou Citation2004). In the case of China, and elsewhere, the dominance of outperforming cities, while others may flounder, strikes cause for concern. As Chetty et al. (Citation2014) find in their study of social mobility in the U.S.; one’s hometown can have a significant impact on their lifetime economic prospects. Liu (Citation2015) shows the differential impact on social mobility as the result of attending inland versus coastal universities. One of the policy imperatives that stem from this observation is that further work is needed to boost opportunities for ‘underdogs’ (Gargam Citation2020) who stay inland to go to university. Policies are needed that enable the effective industry and government collaborations with inland universities, so that would-be entrepreneurs living inland do not need to migrate. But rather, local universities could offer the human and capital accumulation potential that highly-ranked universities in Beijing, Shanghai and Shenzhen offer today.

Acknowledgements

Comments provided by participants of the UCLA International Symposium on Global Chinese Entrepreneurship, held 20-21 November, 2020, and the ‘Urbanization, rural development and changing social policy’ workshop, held at King’s College London on November 27, 2019, were helpful in shaping the paper. We are also grateful for anonymous reviewers’ comments and suggestions that helped to sharpen the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Robyn Klingler-Vidra

Dr Robyn Klingler-Vidra is Reader in Political Economy at King’s College London. Robyn is the author of The Venture Capital State: The Silicon Valley Model in East Asia (Cornell University Press, 2018) and has published on innovation, entrepreneurship and venture capital in highly-ranked journals, including International Affairs, New Political Economy, Regulation and Governance, and Socio-economic Review, and has led Innovate UK and UNDP-commissioned studies on inclusive innovation. She obtained her BA in Political Science at the University of Michigan and her MSc and PhD in International Political Economy from the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE).

Steven Jiawei Hai

Mr Steven Jiawei Hai is PhD candidate in Political Science at King’s College London. His research primarily focuses on the political economy of technology development, innovation policy and digital entrepreneurship in China and other emerging economies. Steven obtained his BA in International Politics from the University of International Relations (UIR), Beijing, and MA in International Political Economy from the University of California San Diego (UCSD), California. Prior to King's, he was a research and teaching fellow at the Department of Politics and Public Administration, The University of Hong Kong (HKU).

Ye Liu

Dr Ye Liu is Senior Lecturer in International Development. Prior to her post at King’s, she was a Senior Lecturer in International Education at Bath Spa University between 2013 and 2016, and was a lecturer of Contemporary Chinese Studies and Director of the BA programme in Chinese Studies at the University College Cork, Ireland from 2012 to 2013. She was awarded a PhD in Comparative Sociology in 2011 at the Institute of Education, University of London, supported by a Nicholas Hans Scholarship and the Overseas Research Student (ORS) scholarship. She was awarded the 2014 Junior Sociologist Prize by the Research Committee on Women in Society of the International Sociology Association and the 2014 Newer Researcher Award by the Society for Research into Higher Education (SRHE). She has published in highly ranked international journals, such as the British Journal of Sociology of Education, Higher Education and International Journal of Educational Development. Her first monograph entitled, 'Higher education, meritocracy and inequality in China' was published by Springer in September 2016.

Adam William Chalmers

Dr. Adam Chalmers is Reader in Politics in the Department of Political Economy at King’s College London. He has a PhD in Political Science from McGill University (2011) and was an Assistant Professor of International Relations at Leiden University in the Netherlands (2011-2015). His research, which mainly focuses on international regulatory politics, the politicisation of international trade, and interest group politics, has been published in numerous journals (including Regulation and Governance, Business and Politics, European Journal of Political Research, Political Communication, and Review of International Political Economy), book chapters, and policy papers.

Notes

1 Ma lost his title as the wealthiest man in March 2021. For details of his net worth, see https://www.wsj.com/articles/alibaba-co-founder-jack-ma-loses-title-as-chinas-richest-person-11614695213.

2 According to Barboza (Citation2015), upon graduation, Ma taught English and, at one point, took a short trip to California. His 1995 trip was to Malibu on behalf of the Hangzhou city government to recover a debt owed by an American businessman as part of a joint venture (Wattles Citation2018). Although he did not join a Master’s program or work for a startup in California like many of his peers, this short trip is said to have had a profound impact on Ma’s motivation to create an internet business in China. Ma worked for an internet company in Beijing, backed by the Ministry of Foreign Investment and Trade, for a year before returning to Hangzhou and establishing Alibaba in 1999.

3 The CrunchBase database is managed by TechCrunch, a renown new sources for the startup and venture capital activities. We use the CrunchBase data given its global coverage. It can be accessed here: https://www.crunchbase.com/.

4 The ten companies with state foundations are: Shanghai Pudong Development Bank, COFCO, China Unicom, Inspur Cloud, Tsinghua Unigroup International, HNA Group, Shanghai Canxing Cultural and Broadcast Company, Sinochem Energy, CMC Inc. and BAIC BJEV.

5 The 16 companies excluded on the basis of being subsidiaries are: Suning Finance, JD Logistics, Tencent Music, JD Health, Alibaba Cloud, JD Digits, Qingju, Bitauto Holdings, Cainiao Logistics, Lu.com, Koubei, Le Sports, Wanda Film, LeSee, Toutiao, and Ping An Healthcare Management.

6 The companies that have gone into bankruptcy or found guilty of fraud are: Luckin Coffee and Ofo.

7 The Chinese Geographic Information Professional Knowledge Service System is accessible here: http://kmap.ckcest.cn/otherSearch/searchztsjGISPage.

8 See https://geonames.nga.mil/gns/html/index.html for the National Geospatial Intelligence Agency.

9 The UNEP’s Environmental Data Explorer is available at http://geodata.grid.unep.ch/.

10 The National Catalogue for Geographic Information is accessible here: https://www.webmap.cn/main.do?method=index.

11 For more information, see the ArcGIS website: https://www.arcgis.com/index.html.

12 The hukou is a household registration system in China, which determines where citizens have access to social and health benefits.

13 Beijing and its top-ranking universities are not located on the sea, but are less than 200 kilometers from the sea, so are considered coastal rather than inland.

References

- Adams, S. B. 2005. “Stanford and Silicon Valley: Lessons on Becoming a High-Tech Region.” California Management Review 48 (1): 29–51.

- Ahlstrom, D., and G. D. Bruton. 2002. “An Institutional Perspective on the Roel of Culture in Shaping Strategic Actions by Technology Focused Entrepreneurial Firms in China.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 26 (4): 53–69.

- Akcomak, S., and B. ter Weel. 2009. “Social Capital, Innovation and Growth: Evidence from Europe.” European Economic Review 53 (5): 544–567.

- Ang, Y. Y. 2016. How China Escaped the Poverty Trap. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Barboza, D. 2015. “New Partner for Yahoo Is a Master at Selling.” New York Times, August 15.

- Batjargal, B. 2007. “Internet Entrepreneurship: Social Capital, Human Capital, and Performance of Internet Ventures in China.” Research Policy 36: 605–618.

- Bloch, R., A. Mitterle, C. Paradeise, and T. Peter. 2017. Universities and the Production of Elites: Discourses, Policies, and Strategies of Excellence and Stratification in Higher Education. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Bourdieu, P. 1986. “The Forms of Capital.” In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, edited by J. G. Richardson, 241–258. New York: Greenwood.

- Bruton, G. D., D. Ahlstrom, and H.-L. Li. 2010. “Institutional Theory and Entrepreneurship: Where Are We Now and Where Do We Need to Move in the Future?” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 34 (3): 421–440.

- Brzozowski, J., M. Cucculelli, and A. Surdej. 2019. “Exploring Transnational Entrepreneurship: Immigrant Entrepreneurs and Foreign-Born Returnees in the Italian ICT Sector.” Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship 31 (5): 413–431.

- Camara Malerba, R., and J. J. Ferreira. 2021. “Immigrant Entrepreneurship and Strategy: A Systematic Literature Review.” Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship 33 (2): 183–217.

- Cheng, Z., W. Guo, M. Hayward, R. Smyth, and H. Wang. 2021. “Childhood Adversity and the Propensity for Entrepreneurship: A Quasi-Experimental Study of the Great Chinese Famine.” Journal of Business Venturing 36 (1): 106063.

- Chetty, R., N. Hendren, P. Kline, E. Saez, and N. Turner. 2014. “Is the United States Still a Land of Opportunity? Recent Trends in Intergenerational Mobility.” American Economic Review 104 (5): 141–147.

- Coleman, J. S. 1998. Foundations of Social Theory. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Davidsson, P., E. Hunter, and M. Klofsten. 2006. “Institutional Forces: The Invisible Hand That Shapes Venture Ideas.” International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship 24 (2): 115–131.

- Delmar, F., and P. Davidsson. 2000. “Where Do They Come from? Prevalence and Characteristics of Nascent Entrepreneurs.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 12 (1): 1–23.

- Engel, J. S. 2014. “What Are Clusters of Innovation, How Do They Operate and Why Are They Important?” In Global Clusters of Innovation: entrepreneurial Engines of Economic Growth around the World, edited by J. S. Engel, 5–37. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Farquharson, M., and S. Pruthi. 2015. “Returnee Entrepreneurs: Bridging Network Gaps in China after Absence.” South Asian Journal of Management 22 (2): 9–35.

- Gargam, F. 2020. “Unlikely Champions: how Underdogs Create Strategies Advantages.” Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship 32 (5): 401–429.

- Giulietti, C., G. Ning, and K. F. Zimmerman. 2012. “Self-Employment of Rural-to-Urban Migrants in China.” International Journal of Manpower 33 (1): 96–117.

- Grabher, G. 1993. “The Weakness of Strong Ties: The Lock-in of Regional Development in the Ruhr Area.” In The Embedded Firm: On the Socioeconomics of Industrial Networks, edited by G. Grabher, 255–277. London: Routledge.

- Granovetter, M. 1973. “The Strength of Weak Ties.” American Journal of Sociology 78 (6): 1360–1380. DOI: jstor.org/stable/2776392.

- Guo, Q., C. He, and D. Li. 2016. “Entrepreneurship in China: The Role of Localization and Urbanization Economies.” Urban Studies 53 (12): 2584–2606.

- Guth, M. 2005. “Innovation, Social Inclusion and Coherence Regional Development: A New Diamond for a Socially Inclusive Innovation Policy in Regions.” European Planning Studies 13: 333–349.

- Hao, X., K. Yan, S. Guo, and M. Wang. 2017. “Chinese Returnees’ Motivation, Post-Return Status and Impact of Return: A Systematic Review.” Asian and Pacific Migration Journal 26 (1): 143–157.

- Kariv, D., L. Cisneros, and M. Ibanescu. 2019. “The Role of Entrepreneurial Education and Support in Business Growth Intentions: The Case of Canadian Entrepreneurs.” Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship 31 (5): 433–460.

- Kenney, M., D. Breznitz, and M. Murphree. 2013. “Coming Back Home after the Sun Rises: Returnee Entrepreneurs and Growth of High-Tech Industries.” Research Policy 42 (2): 391–407.

- Klingler-Vidra, R., and Y. Liu. 2020. “Inclusive Innovation Policy as Social Capital Accumulationstrategy.” International Affairs 9 (4): 1033–1050.

- Klingler-Vidra, R., B. Tran, and A. Chalmers. 2021. “Transnational Experience and High-Performing Entrepreneurs in Emerging Economies: Evidence from Vietnam.” Technology in Society 66: 101605.

- Lang, R., M. Fink, and E. Kibler. 2014. “Understanding Place-Based Entrepreneurship in Rural Central Europe: A Comparative Institutional Analysis.” International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship 32 (2): 204–227.

- Lee, K.-f. 2018. AI Superpowers: Silicon Valley, China and the New World Order. Houghton Mifflin.

- Li, C. 2016. “China’s New Think Tanks: Where Officials, Entrepreneurs, and Scholars Interact.” China Leadership Monitor 29: 1–21.

- Li, M., L. He, and Y. Zhao. 2020. “The Triple Helix System and Regional Entrepreneurship in China.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 32 (7-8): 508–530.

- Li, X. 2016. “Exploring the Spatial Heterogeneity of Entrepreneurship in Chinese Manufacturing Industries.” Journal of Technology Transfer 42 (5): 1077–1099.

- Lin, W. 2020. “Participatory Geographic Information Systems in Visual Research.” In The SAGE Handbook of Visual Research Methods, edited by L. Pauwels and D. Mannay, 173–185. London: SAGE.

- Liu, Y. 2015. “Geographical Stratification and the Role of the State in Access to Higher Education in Contemporary China.” International Journal of Educational Development 44 (44): 108–117.

- Liu, Y. 2016. Higher Education, Meritocracy and Inequality in China. London: Springer.

- Liu, Y., Y. Huang, and W. Q. Shen. Forthcoming. “Branding Elite: How Do Chinese Elites Seek Distinction through Studying Abroad?” British Journal of Sociology.

- Lu, J., and Z. Tao. 2010. “Determinants of Entrepreneurial Activities in China.” Journal of Business Venturing 25 (3): 261–273.

- McKinnon, I., and J. McCallum Breen. 2020. “Expanding Cartographic Practices in the Social Sciences.” In The SAGE Handbook of Visual Research Methods, edited by L. Pauwels and D. Mannay, 154–172. London: SAGE.

- Mejia, P., and M. Melendez. 2012. “Middle-Class Entrepreneurs and Social Mobility through Entrepreneurship in Colombia.” Inter-American Development Bank working paper no. IDB-WP-317. September.

- Nazareno, J., M. Zhou, and T. You. 2019. “Global Dynamics of Immigrant Entrepreneurship: Changing Trends, Ethnonational Variations, and Reconceptualizations.” International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research 25 (5): 780–800.

- Nee, V., and S. Opper. 2012. Capitalism from below: Markets and Institutional Change in China. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Parker, S. 2009. “Can Cognitive Biases Explain Venture Team Homophily?” Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 3 (1): 67–83.

- Parker, T. 2020. “Where Do Unicorn Founders Go to College?” Investopedia, August 17.

- Peng, Y. S. 2004. “Kinship Networks and Entrepreneurs in China’s Transitional Economy.” American Journal of Sociology 109 (5): 1045–1074.

- Portes, A. 1998. “Social Capital: Its Origins and Applications in Modern Sociology.” Annual Review of Sociology 24 (1): 1–24.

- Putnam, R. D. 1993. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Renzulli, L. A., H. Aldrich, and J. Moody. 2000. “Family Matters: Gender, Networks, and Entrepreneurial Outcomes.” Social Forces 79: 523–546.

- Ruan, J., and X. Zhang. 2014. ““Flying Geese” in China: The Textile and Apparel Industry’s Pattern of Migration.” Journal of Asian Economics 34: 79–91.

- Senor, D., and S. Singer. 2009. Start-up Nation: The Story of Israel's Economic Miracle. New York: Hachette Book Group.

- Steinberg, S. J., and S. L. Steinberg. 2006. Geographic Information Systems for the Social Sciences: Investigating Space and Place. London: SAGE.

- Su, J., Q. Zhai, and H. Landstrom. 2015. “Entrepreneurship Research in China: Internationalization or Contextualization?” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 27 (1-2): 50–79.

- The Economist. 2019. “How Silicon Valley Woos Stanford Students.” November 2.

- Troilo, M., and J. Zhang. 2012. “Guanxi and Entrepreneurship in Urban China.” Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy 17 (2): 315–331.

- Wang, H., D. Zweig, and X. Lin. 2011. “Returnee Entrepreneurs: Impact on China’s Globalization Process.” Journal of Contemporary China 20 (70): 413–431.

- Wattles, J. 2018. “How Jack Ma Went from English Teacher to Tech Billionaire.” CNN, September 9.

- Westlund, H., and R. Bolton. 2003. “Local Social Capital and Entrepreneurship.” Small Business Economics 21 (2): 77–113.

- Wong, J. 2016. “Jack Ma, Rejected for Job at KFC, Buys Piece of It Instead.” Wall Street Journal, 2 September.

- Xu, J., and Y. Cao. 2019. “Innovation, the Flying Geese Model, IPR Protection, and Sustainable Economic Development in China.” Sustainability 11 (20): 5707.

- Yang, M. 1994. Gifts, Favors, and Banquets. New York: Cornell University Press.

- Zhang, J., and Z. Zhao. 2015. “Social-Family Network and Self-Employment: Evidence from Temporary Rural-Urban Migrants in China.” IZA Journal of Labor & Development 4 (1): 4.

- Zhao, L., and J. D. Aram. 1995. “Networking and Growth of Young Technology-Intensive Ventures in China.” Journal of Business Venturing 10 (5): 349–370.

- Zhao, L., and J. Ha-Brookshire. 2018. “Importance of Guanxi in Chinese Apparel New Venture Success: A Mixed-Method Approach.” Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research 8 (1): 1–19.

- Zheng, L., and Z. Zhao. 2017. “What Drives Spatial Clusters of Entrepreneurship in China? Evidence from Economic Census Data.” IZA Institute of Labor Economics IZA DP No. 11074. October.

- Zhou, L., M. Farquharson, and T. W. Y. Man. 2016. “Human Capital of Returnee Entrepreneurs: A Case Study in China.” Journal of Enterprising Culture 24 (04): 391–418.

- Zhou, M. 2004. “Revisiting Ethnic Entrepreneurship: Convergencies, Controversies, and Conceptual Advancements.” International Migration Review 38 (3): 1040–1074.

- Zhou, W. 2011. “Regional Deregulation and Entrepreneurial Growth in China’s Transition Economy.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 23 (9-10): 853–876.