?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This paper intends to evaluate the efficiency of programs aimed at providing youth education and microfinance services, as well as the direct and indirect impacts of such programs on the independence of the beneficiaries. The sample consists of 141 young adults in Indonesia; all of whom were beneficiaries of an NGO which focuses on youth development through education and microfinance initiatives. The free disposal hull (FDH) order-m technique employed in this study examines which initiative (education to youths or microfinance services for mothers) leads to the highest benefit (output) for the beneficiaries, given a certain level of cost (input). In operationalising the FDH, a composite index of independence that combines work status, work knowledge, self-determination, income, expenditure, and savings to measure the independence of the young adults was used as the output, and costs associated with implementing the programs serve as the input. The results indicate that in terms of output only, young adults whose mothers receive microfinance and no financial literacy training had the highest level of independence. On the other hand, when the costs associated with providing the programs are considered, the use of FDH order-m suggests no significant difference in the efficiency of the different programs.

Résumé

Cet article a pour objectif l’évaluation de programmes visant à offrir aux jeunes des services d’éducation et de microfinance, ainsi que des impacts directs et indirects de ces programmes sur l’indépendance de leurs bénéficiaires. L’échantillon se compose de 141 jeunes adultes en Indonésie, tous bénéficiaires d’une ONG qui se concentre sur le développement de la jeunesse à travers l’éducation et des initiatives de microfinance. Le modèle d’enveloppe de libre disposition (FDH) employé dans cette étude examine quelle initiative (éducation des jeunes ou services de microfinance pour les mères) conduit au bénéfice le plus élevé (output) pour les bénéficiaires, étant donné un certain niveau de coût (input). Dans l’opérationnalisation du FDH, un indice composite d’indépendance qui combine le statut de travail, la connaissance du travail, l’autodétermination, le revenu, les dépenses et l’épargne pour mesurer l’indépendance des jeunes adultes a été utilisé comme output, et les coûts associés à la mise en oeuvre des programmes servent d’input. Les résultats indiquent que seulement en termes de production, les jeunes adultes dont les mères bénéficient d’une microfinance mais d’aucune formation en compétences financières, avaient le niveau d’indépendance le plus élevé. D’autre part, lorsque les coûts associés à la prestation des programmes sont pris en compte, l’utilisation du modèle FDH ne suggère aucune différence significative en matière d’efficacité des différents programmes.

1. Introduction

Human resources are one of the essential factors in the economic growth of any country. The competitiveness of a country depends on the education and nurturing of youths to prepare them to enter the labour force. Nevertheless, many people in middle-income countries (MICs) do not have the opportunity to educate themselves by any means, and this makes it very difficult for them to achieve their potential. Even though primary and secondary education is free in many MICs like Indonesia, there are still many challenges in keeping children in school. The rate of secondary school enrolment in the country in 2018 was only 89% (World Bank Citation2020). This statistic is concerning since it limits the children and makes it harder for them to achieve economic self-sufficiency. One macro indicator of young adults' independence is the unemployment rate. In Indonesia, youth unemployment remains an issue. According to the World Bank database (World Bank Citation2020), the International Labour Organisation (ILO) estimated that in 2019, more than 16% of the labour force aged 15-24 in Indonesia were unemployed. This figure is significantly higher compared to neighbouring countries, including Malaysia (11.7%), Thailand (3.7%), and Vietnam (6.9%). As suggested by UNFPA (Citation2014), the problem of economic opportunity is the greatest for the young.

Different approaches have been launched to tackle these issues to close the gap between privileged and underprivileged adolescents to improve young adult's independence. The provision of education to those who are out of school is one of the most direct solutions in helping youths' transition from destitution to fulfilling their potential to themselves and society (Dworsky Citation2005). There are, however, many cases where these programs do not achieve their intended outcomes, as highlighted in the literature. Often children who become too old for foster care and do not have supporting infrastructure or aid are found living in poverty (Gates et al. Citation2018). Many are unemployed and without the potential to help either society or themselves. According to Miller, Green, and Lambros (Citation2019), youths in foster care achieve lower results in school and have lower graduation rates than their wealthier counterparts. As a result, achieving full independence becomes a severe challenge which they often do not overcome. These people eventually grow up to have children that are born in the same social conditions as and the cycle repeats itself over the generations.

The lack of education could be due to a variety of factors including financial instability, and fear of abandonment or segregation. Some families keep their children to do households chores while the parents are working, others with small and micro businesses keep them as employees to save on labour costs (Behrman and Parker Citation2010). Hence, it is impossible to ignore the link between the financial security of families with businesses and the education of their children. It is crucial to examine poverty eradication strategies from the perspective of businesses and parents, as well as considering the welfare and education of the children.

Microfinance is used in various countries to encourage financial independence and improve the lives of underprivileged young adults through education. Many impoverished families with micro-businesses from around the world suffer from a lack of financing (Johnston and Morduch Citation2008). Microfinance attempts to give financing to those whom banks, and other institutions are reluctant to serve due to high risks. In a way, microfinance aims to fill in the gap by serving the people at the bottom of the pyramid of society (Armendariz and Morduch Citation2005) to improve their economic conditions. Research conducted with Vietnamese families has shown a positive correlation between household income and the quantity of financing received (Thanh, Saito, and Duong Citation2019). Microcredit is considered a useful tool to improve welfare and reduce poverty through an increase in consumption, income, and employment (Khandker and Koolwal Citation2016).

Beyond the simple economic advantages, microfinance is also seen as a tool for empowering women. Because of more convenient access to credit, women can improve their status and well-being by increasing their income, which gives them the financial independence to care for their health (Malhotra, Schuler, and Boender Citation2002). The economic contribution of women to the household is crucial in many homes. Mahmud (Citation2003) found that low-income women who take microcredit programs are more likely to choose to invest in the education of their children. This finding indicates that empowering women has a positive impact on families, especially on children's education. In line with this study, Rokhim et al. (Citation2016) showed that household spending on education increased after they received microcredit.

This paper evaluates the efficiency of the programs implemented by YCAB aimed at providing youth education and microfinance services, as well as the direct and indirect impacts on the independence of the beneficiaries. Although it is crucial to examine which program yields the highest benefit concerning cost, to date, there has been a lack of studies that compare the cost with benefits. Gamble (Citation2018) assessed different forms of institutional logic used by microfinance programs in India, specifically: microfinance with well-being mentoring and business coaching. The aim was to examine which of the two systems yielded the highest investment-adjusted financial and non-financial outcomes. The study found that microfinance with well-being mentorship to be the most effective method. Nevertheless, it should be noted that the features of the programs did not significantly differ, and the ultimate goal of these programs was not young adults' independence. Also, there is little literature about microfinance in Indonesia concerning the relationship with the independence of the beneficiary's children.

YCAB is a social enterprise focused on youth development; in 2019, the foundation was ranked 35th of the top 500 Global NGOs. Its principal goal is to promote independence in young people by providing education to the children and microcredit access to low-income mothers on the condition that they send their children to school. YCAB bases its operations on the sustainable social change model, and its mission is to improve welfare through education and micro-loan financing. To date, YCAB has provided education to 3.4 million underprivileged youths and has given microcredit to over 150,000 low-income households. To this end, there are two available main programs in YCAB: leaning centres (Rumah Belajar) and mission-driven microfinance.

Rumah Belajar centres are focused on providing basic education and vocational training. Basic education teaches basic mathematics, English, geography, and science to students who have dropped out of mainstream schools. This program is known as Paket Program and is an equivalency education program for out of school children. The vocational training courses teach skills related to health and beauty, motorcycle mechanics, electronic tool repair, machine sewing, and batik crafting. The monthly fee per child is IDR10,000 (or approximately USD 2.36, PPP-adjusted).

YCAB's microfinance programs target low-income mothers as entrepreneurs and loan-receivers. The organisation emphasises that the mothers must send their children to school in order to receive the loan; their children must not drop out during the duration of the loan cycle. If in any case, they do drop out, they are given a one-year grace period to put the children back to school, or they can send their children to gain an education in YCAB's learning centres in their neighbourhood.

Profit generated from this microfinance program is used to support the operational activities of learning centres. This program is aligned with YCAB's mission to promulgate women empowerment and youth development. YCAB also provides financial literacy training to the beneficiaries with the help of both social investors (i.e. Bank of Indonesia, the central bank of Indonesia) and philanthropic investors (i.e. HSBC).

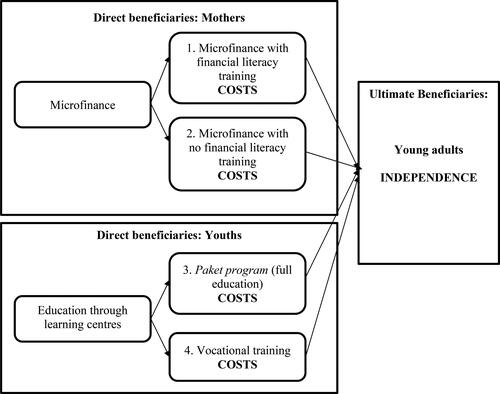

Based on YCAB's different programs, the young adults who are the ultimate beneficiaries in this study are categorised into four groups: (1) those whose mothers were microfinance clients and participated in financial literacy training; (2) those whose mothers were microfinance clients and did not receive financial literacy training; (3) alumni from YCAB's comprehensive learning program which comprises of the Paket Program and some vocational training; and (4) alumni from YCAB's vocational training only who also went through mainstream formal high school education.

This paper uses the frontier-estimation approach as the tool to determine whether education or microfinance is most beneficial, given a certain level of input. The technique has been widely used to estimate the efficiency of both manufacturing and service industries (Keh and Chu Citation2003; Halkos and Tzeremes Citation2007; Ariff and Can Citation2008; Park and Weber Citation2006). Also, many studies have been applying this technique to human development (Binder and Broekel Citation2011; Deutsch, Ramos, and Silber Citation2003; Ramos and Silber Citation2005). The Order-m Free Disposal Hull (FDH) method developed by Deprins, Simar, and Tulkens (Citation1984) was employed in this study. When using the FDH, the input and output associated with a production process should first be determined. In the case of this study, the inputs are the costs incurred by providing the service (microfinance and education), and the output is young adults independence score, which is composed of working status, working knowledge, self-determination, income, expenditure, and savings indicators.

The findings of this study indicate that young adults whose mothers received microfinance from YCAB without financial literacy training had the highest independence scores. Further analyses reveal that when costs incurred in providing these programs are considered, those whose mothers were the clients of YCAB Foundation's microfinance program and received financial literacy training had the highest (lowest) efficiency (inefficiency) score. However, the differences in the efficiency scores are not statistically significant. This indicates that generally speaking, the efficiency levels of all programs are equal. Given the efficiency scores, there is room for improvement in the efficiency of the programs. However, it should be noted that various factors, both internal- and environmental-related, might contribute to this improvement.

The paper is henceforth organised as follows: Section 2 reviews relevant literature, section 3 describes the methodology and measurement of variables, section 4 shows and explains the results, section 5 provides the discussion, and section 6 concludes our findings.

2. Literature review

2.1. Education and youth independence

Many educational programs have been designed to help young adults achieve independence. The role of education in the development of underprivileged youths in foster care has previously been examined by Cassarino-Perez et al. (Citation2018). The results show that children in foster care with higher levels of educational attainment are better able to find jobs than those with lower levels of education. Teichler (Citation2015) emphasised the importance of school and education in preparing children to enter the workforce. Previous studies found that higher educational attainment is associated with higher income, work status, and greater capacity to face competition (Flouri and Hawkes Citation2010; Ng et al. Citation2005; Faas, Benson, and Kaestle Citation2013). A study by Chowdhury, Endres, and Frye (Citation2019) also found that people with a higher education level may have access to a range of experiences which are helpful to improve their self-efficacy, which is their perception and ability to perform tasks individually.

Formal education (consisting of academic subjects such as mathematics, English, science and social studies) should be differentiated from vocational training (skills and knowledge related to specific industries); the latter of which prepares participants for entry-level positions in various sectors. The literature documented conflicting results on the impact of vocational education on its graduates. Among others, Gates et al. (Citation2018) found that career readiness programs following foster care, based on vocational and interview training, positively influence a child's future independence. Though this type of education helps young adults enter the labour market immediately, Korber and Oesch (Citation2019) found that people who only participate in vocational training receive lower incomes than those with formal education as well. This is because vocational workers often face difficulties adjusting to technological change and changing work structures; therefore, formal education is better suited to prepare children for their future careers. Similarly, Choi, Jeong, and Kim (Citation2019) highlighted that in the long term, vocational training graduates were more likely to possess lower literacy skills compared to general education graduates.

The complexities surrounding the success of education programs might be due to various factors. First, other factors contribute more significantly to young adult's independence, such as support from family and friends during their transition to adulthood, as suggested by Kim et al. (Citation2019). Another problem in evaluating these programs stems from the fact that measuring independence is not always straightforward. There is no single measure, and different scholars have conceptualised it using different elements. For example, Dworsky (Citation2005) used a comprehensive indicator consisting of employment, earnings, and public assistance receipts to measure former foster youths' self-sufficiency. In evaluating a career readiness preparation program for youths, Gates et al. (Citation2018) looked at work status and self-determination, as well as career readiness itself. Self-reported measures have also been used, as can be seen in the SSM that assesses individuals' self-sufficiency in 11 life domains: finances, day-time activities, housing, domestic relations, mental health, physical health, addiction, activities daily life, social network, community participation, and judicial (Bannink et al. Citation2015).

2.2. Microfinance for women and education

Recently, many organisations are considering women empowerment within their goals. Kabeer (Citation1999) identified three dimensions of women empowerment, which are resources (where women could get access or claim material resources), agency (where women have a role or are involved in the decision-making proses), and achievements (the improvement of their well-being). Microfinance services offered to women could provide them with many economic opportunities and broader access to material resources, which will eventually enhance their involvement in essential decisions making within their households. Kato and Kratzer (Citation2013), Khan, Zaki, and Bokhari (Citation2017) as well as Yadav and Verma (Citation2015) independently found that women who joined microfinance programs and increased their earnings have improved savings, decision-making capacities, and self-esteem.

Women's agency is shown to be positively associated with welfare indicators at the household level. Mothers with financial freedom tend to prioritise their children's educational needs by investing their time and resources towards it. Mahmud (Citation2003) found that for poor households, there exists a positive relationship between microfinance and the general well-being of the house. In most cases, this leads to improved health and education of the children, variables linked with higher living standards for their children's future. Furthermore, Schaedel, Azaiza, and Hertz-Lazarowitz (Citation2007) suggest that a more active role for women in the households could deepen social interactions with children, further improving their academic performance.

2.3. The impact of financial literacy training

Providing resources to women, as done by many microfinance programs, is associated with an increase in their well-being (Kato and Kratzer Citation2013). This increase could be encouraged further by providing training along with financing. Through this training, they can learn to allocate money wisely and engender better outcomes for themselves and their family (Monteza, Blanco, and Valdivieso Citation2015). There have been studies that attempted to evaluate financial literacy training, with inconsistent findings regarding its impact on financial behaviour (see for example Stango and Zinman Citation2007; Lusardi Citation2008; Mandell and Klein Citation2009; Behrman et al. Citation2012; Cole, Sampson, and Bilal Citation2011). A meta-analysis by Fernandes, Lynch, and Netemeyer (Citation2014) on 168 empirical studies led to a conclusion that the typical financial education programs were not associated with improved financial behaviour. Moreover, Karlan, Ratan, and Zinman (Citation2014) argued that even when a study shows a positive correlation between financial literacy and behaviour, it cannot guarantee the existence of a causality relationship.

Studies have also explicitly established linked between training and children's education. Gamble (Citation2018) shows that business training given to women has the expected effect of improving their ability to save money, budget, and allocate resources to their children's education. This aligns with Awan and Kauser (Citation2015) work that shows a positive relationship between the education of mothers and the final level of education of their children; likewise, the lower the level of education or financial freedom of the mother, the higher the chances are of their children failing school.

3. Methods

3.1. Research design and hypotheses

The primary purpose of this study is to evaluate the efficiency of the costs incurred by YCAB's microfinance and education programs and their impacts on the independence of young adults. The direct beneficiaries of the microfinance program are mothers. As has been explained previously, some of YCAB's microfinance clients also received financial literacy training. Meanwhile, young adults are the direct beneficiaries of the education programs. The first type of education program is Paket Program, which provides high-school level education for dropouts, and vocational training, which those who are in the formal education system can also join. The ultimate beneficiaries are young adults who gain increased autonomy and independence. To estimate the efficiency of the programs (i.e. the one that yields the highest output given a certain level of input) the costs associated with providing the initiatives and the benefits (independence) need to be estimated. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was then performed to identify the differences in efficiency scores among different YCAB beneficiaries. The null hypothesis is there is no statistically significant difference in the average efficiency scores among different groups of beneficiaries within the population, while the alternative hypothesis is at least one group has statistically significant different average efficiency score from those of the other groups. This study also uses ANOVA to compare the independence levels of the young adults who received different programs.

illustrates the framework used in this study.

3.2. Data collection

In this study, a quantitative survey was conducted to collect some information regarding young adult's independence. The survey was administered from November – December 2018 in the urban area of Greater Jakarta. Before the survey, the enumerators were trained to make sure they understood the objective of this study and the information being gathered.

The respondents come from YCAB's learning centres and from those whose mothers receive financing from the foundation. This study limits the respondents to young adults aged between 21 and 24, assuming that those in this age range are at an early stage of their career. Also, too large a variation in age may add variables which are unaccounted for. The database contains 162 potential respondents who fulfilled the criteria, but only 141 could be contacted. The data was collected through questionnaires sent from December 4th, 2018 to January 10th, 2019. The questions were divided into four sections: “Personal data”, “Work knowledge”, “Self-determination”, and “Income and expenditure”. Further elaboration is provided in the following subsection.

According to the different programs examined in this study, the respondents can be classified into four groups: (1) young adults whose mothers were microfinance clients and participated in financial literacy training; (2) young adults whose mothers were microfinance clients and did not receive any financial literacy training; (3) alumni of YCAB's education program which includes Paket Program and vocational training (4) alumni of YCAB's vocational training only, but who also went through mainstream formal high school education.

3.3. Measurement

The measured result of this research is the efficiency score which considers the benefits as well as the costs incurred by YCAB. The efficiency score is calculated using the free disposal hull (FDH) method with investments incurred by different types of respondents in YCAB as input factors and independency scores as output factors.

3.3.1. Output, young adult's independence score

Young adult's independence score is a composite index consisting of the following six components

Working status score: It is assumed that to become independent, a young adult should have a decent-paying occupation. Respondents first indicate whether they are working (including being self-employed) if they respond yes, they were asked whether their income was similar to, or exceeded, the minimum wage of IDR 3,600,000 per month (or USD 848, PPP-adjusted). If the respondents are not working, the follow-up question asked whether they are studying, or have had a paid job recently. Their reasons for not working were also investigated. The possible score for working status is from 1-10; this was then rescaled to a score from 0-1. This score contributes 30% of the weight of the final result.

Working knowledge score: There are cases where the participants may not be working but are actively seeking employment. The survey collected information about their fundamental knowledge of applying for jobs. The questions related to job vacancies, work-life, and applications. For each question, the right answer is rewarded with 1 point and the wrong answer with 0 points. This section has five questions, so the scores vary from 0 and 5; which is converted to a value ranging from 0 to 1. The weight of this section towards the final score is 15%.

Self-determination score: Gates et al. (Citation2018) have shown the importance of self-determination, which can be defined as one's ability to make decisions related to career choices. Six questions were adapted from the American Institute of Research (AIR) self-determination scale, as employed by Gates et al. (Citation2018). The questions included “you set goals to get what you want or need” and “you begin working on your plans to meet your goals as soon as possible”. The responses were measured by a Likert scale from one to five, in which 1 = never, 2 = seldom, 3 = sometimes, 4 = often, and 5 = always. This score has a minimum value of 5 and a maximum value of 30, which is rescaled into a value between 0-1. The variable's Cronbach's alpha for our sample is 0.90, indicating a high reliability. The weight of this score for the overall independence index is 15%.

Income score: This score is measured by using the regional minimum wage (IDR 3,600,000 or USD 848) as a benchmark for respondents' income. If the income of working respondent is higher than, equal to, or lower than the regional minimum wage, the scores are respectively 3, 2, and 1. This score is then rescaled into a value between 0-1 and contributes 20% of the final score.

Expenditure score: Young adults should be self-sufficient to achieve independence. In this section, respondents were required to fill in their expenses categorised into ten types: housing, electricity and water, food and beverage, tokens, clothing, snacks, cigarettes, education, personal healthcare, and credit card payments or loan instalments. The default score of 1 is awarded for each expenditure that the young adult bears alone, the score is then reduced based on the proportion of the expenditure held by parents or other third parties. If the respondents are not working, a score of zero is given. The score for this section ranges from 0 to 10, then rescaled to a value between 0 and 1. The weight of the score on the overall independence score is 10%.

Savings score: It is believed that young adults should have enough savings to survive unexpected events which may require large amounts of money. The measurement of this element uses a dichotomous variable – there are only two alternative answers; have savings or not. Respondents who set aside a portion of their income for savings are rewarded one point, and therefore the score is either 1 or 0. This element is given 10% weight.

summarises the measurement of Independence score.

Table 1. Independence score (output) calculation.

3.3.2. Input costs

describes the amount of monthly costs incurred by YCAB related to different types of respondents. The numbers reflect the direct and indirect costs and were collected from YCAB's monthly financial statements.

Table 2. Costs (input) for different types of beneficiaries*.

3.2.3. Free disposal hull (FDH) in Efficiency Score Measurement

As previously stated, the frontier estimation technique in efficiency measurement is often used in both manufacturing and service industries (Keh and Chu Citation2003; Halkos and Tzeremes Citation2007), and this technique is also applicable to the context of human development (Binder and Broekel Citation2011 among others). In this study, a non-parametric version of the free disposal hull (FDH) method developed by Deprins, Simar, and Tulkens (Citation1984) was used to measure the efficiency of the production unit, also known as decision-making units (DMUs). The FDH measures the DMU's efficiency at converting input into output. Once the estimated frontier is constructed, the efficiency of each DMU is calculated as a distance function relative to the most efficient data point. There are two models of FDH: input-oriented and output-oriented. The former model aims to minimise input at constant output levels, whereas the latter attempts to minimise output at constant input levels.

The use of non-parametric technique such as FDH is often criticised as it is sensitive to outliers in the sample (Tulkens Citation1993). This limitation led to the emergence of several partial frontier approaches, including order-m by Cazals, Florens, and Simar (Citation2002). Outliers are treated as super-efficient observations and are located beyond the estimated frontier (Tauchmann Citation2012).

In specifying the estimated frontier using, each DMUi, i = 1, ……, N is compared to other DMUj j = 1, ……, N with at least has the same level of output (Y), which is used for comparison and denoted as Bi. The one using a minimum level of input serves as the benchmark for i, and efficiency is calculated as:(1)

(1)

Order-m specification sets the benchmark for an expected best performance among certain m peers. This technique allows us to estimate the pseudo-efficiency score for D times, and the final efficiency score is the average of these scores. Mathematically:(2)

(2)

In using the FDH order-m to measure efficiency, costs incurred are used as the input and the independence score as the output. If the score of a particular DMU equals to one, we can say that the respective DMU is efficient. When the score is below one, they are super-efficient, and when the score is higher than 1, the DMU is inefficient.

4. Results

4.1. Respondent's profile

presents the demographic characteristics of the sample used in this study. In total, there were141 respondents, 59 of whom (42%) were men. One respondent had no formal education degree (0.70%). Three respondents had finished special high school and elementary school level (2.11%), 16 had finished junior high (11.27%), 32 had a vocational high school degree (22.54%), and five had graduated from YCAB's Paket Program. Finally, the majority of the sample, or 85 respondents (60.56%), had at least finished high school.

Table 3. Sample characteristics.

Of the 69 respondents, most were children of YCAB microfinance clients who had not participated in financial literacy training (49.30%). Nineteen of them were children of microfinance clients with financial literacy training (13.38%), five were young adults who had received both Paket Program and vocational training from YCAB (3.52%), and 47 had only participated in YCAB's vocational training (33.10%).

The majority of the respondents (86%) had a stable income source, and 24 (17%) earned at least the minimum wage. Of the workers, 75% were employees, 18% self-employed, 5% freelancers, and 2% were online transportation drivers. Among the respondents who were not working, 11 (50%) had resigned from their old jobs and were seeking new employment, four (20%) were studying, and seven (30%) claimed to have no experience working and were not actively looking for work.

4.2. Independence score

The objective of this study is to identify the impact of different programs offered by the YCAB Foundation and find out which yields the highest benefits (output) given the costs (input), in terms of young-adults independence. An independence score of each young adult surveyed in this study was constructed using the method explained in section 3.3.1, and the average scores of each sample group according to various demographic factors and different programs received are compared. shows that the results for the average independence score is 0.6317 (from a maximum possible score of 1, after standardisation).

Table 4. Independence score of different groups of respondents.

The score is further broken down into its six components: expenditure, work status, self-determination, work knowledge, savings, and income. The average for each is 0.8585, 0.7535, 0.7365, 0.6634, 0.4225 and 0.3826, respectively. These scores have been standardised into a 0-1 scale. Expenditure has the highest average, indicating that overall, respondents could bear their expenses and did not rely on parents or other parties. The lowest average score is income, which means that many respondents' income levels were lower than the minimum wage.

When respondents are divided into groups based on gender, the average independence scores of men and women are 0.6377 and 0.6273, respectively. Although the average independence score of men is higher than that of women, the difference is not statistically significant (p-value ANOVA = 0.7570). In educational attainment, respondents are divided into four categories; those who graduated from vocational high school, senior high school, junior high school, and others (no school, elementary school, and special high school). The average independence scores for each type of respondent are 0.6563, 0.6449, 0.6063, and 0.4425, respectively. Respondents whose education background is vocational high school have the highest average Independence score. The scores' differences between these groups are statistically significant (p-value ANOVA = 0.0329). Concerning the types of benefits provided by YCAB, the independence score of young adults whose mothers had received financing from YCAB without training, young adults whose mothers had received financing and financial literacy training, alumni of YCAB Learning Centre who had received Paket Program and vocational training, and alumni of YCAB Learning Centre who had received only vocational training are 0.6767, 0.6279, 0.6240, 0.5804, respectively. Statistically significant differences in these scores are confirmed (p-value ANOVA = 0.0012).

4.3. Efficiency score

The independence score described in section 4.2 was used to construct the efficiency measure for each respondent. Looking at this efficiency score allows us to see which of the programs yielded the highest benefit in terms of young adults' independence, given their costs. The efficiency of the program was calculated using the FDH order-m approach, as explained in 3.2.3. It should be noted that lower numbers reflect higher levels of efficiency. When the score is below one, it can be said that the respondent, or the DMU, is super efficient, and when the score is higher than 1, the respondent is inefficient.

presents the results related to the efficiency scores. When the respondents are grouped based on gender, the average efficiency scores of men and women are 1.5714 and 1.5661, respectively. However, this difference is not statistically significant (p-value ANOVA = 0.9614), indicating that overall, there is no difference between the efficiency of men and women in converting input into output. Meanwhile, with regards to respondents' educational backgrounds, those whose highest educational attainment was vocational high school have the best (lowest) average efficiency score. The difference between these groups' scores are statistically significant (p-value ANOVA = 0.074).

Table 5. Efficiency score of different groups of respondents.

The main focus of this study is differences in efficiency levels among respondents receiving different YCAB Foundation's programs. The lowest (highest) average inefficiency (efficiency) score is found among young adults whose mothers had received microfinance with no financial literacy training. In contrast, the highest (lowest) average inefficiency score is found among those who had received vocational training only. Nevertheless, the p-value of ANOVA (0.2840) indicates that these differences in efficiency scores are not statistically significant.

5. Discussion

The main purpose of this study was to examine the efficiency of different YCAB programs in enhancing young adults' independence, and the findings also indicate the benefits of the programs. It is shown that 86% of the respondents have a stable source of income from employment, which is a positive finding because it provides security for their living conditions. However, only 17% earnt the minimum wage (IDR 3,600,000 or approximately USD 848, PPP-adjusted), which shows many respondents get paid equal to or below the minimum wage, especially in low-skilled positions. This problem is not specific to YCAB's beneficiaries, but this is a phenomenon present in Indonesia's current employment climate: many people who have been trained to use vocational skills still have limited opportunities to gain an above-average standard of living. A possible solution to this issue is if YCAB could intensify its partnership with hiring companies so that both parties could gain a better understanding of the people that YCAB trains, and what qualifications they need.

Gender differences in the independence score are shown to be statistically insignificant, but the differences based on educational backgrounds are statistically significant. This indicates the important role of education in helping young adults in becoming independent. Higher levels of educational attainment tend to result in more prepared young adults who can start living independently and enter adulthood. There also appears to be a direct correlation between the level of education achieved and their independence score. This is in line with the result of Cassarino-Perez et al. (Citation2018) who show that those who leave their homes with a high school diploma have a better chance of finding employment than those who do not.

The results suggest that assessing the programs in terms of its efficiency brings a different conclusion. When the evaluation of the different programs is merely perceived by the outcomes they produce (i.e. independence), young adults whose mothers receive microfinance with no financial literacy training had the overall highest independence score. However, if the costs of providing such programs are considered in the model, there was no statistically significant difference. This indicates that overall, all YCAB Foundation's programs, when evaluated using young adults' independence, have similar levels of efficiency.

Based on these results, it is suggested that YCAB succeeds in improving the conditions of young adults who dropped out of schools. The previously out-of-school youths from the Paket Program have an overall independence score higher than those who went to formal schools and received vocational training.

The results provide an alternative perspective for assessing the importance of financial literacy training. Young adults whose mothers received both financing and financial literacy training have better average efficiency scores than those whose mothers did not participate in the training. This suggests that giving financial literacy training to mothers has an indirect impact on their children. A previous study by Monteza, Blanco, and Valdivieso (Citation2015) found that giving women access to microcredit accompanied by training, results in greater decision-making capacity and control over their own lives and finances, leading to positive impacts for society. Moreover, educated mothers are likely to have a high awareness about the importance of education for their children and are more likely to invest their time, energy, and resources on their children's education (Gamble Citation2018).

6. Conclusion

This paper aims to evaluate the efficiency of different programs aimed at improving the independence, of self-sufficiency, of young adults. These programs include microfinance with or without financial literacy training, the Paket program (basic education) with vocational training, and vocational training only. Using FDH order-m as the technique to calculate efficiency, this study yields three essential findings. First, the level of educational attainment is shown to have a significant impact on the young adults' independence score. This finding is shown by statistically significant differences observed in independency scores for the educational level. Second, the result suggests that YCAB's Learning Centre program helps dropouts to achieve a similar independence score as those who went through public education, as shown by their similar independence scores. Finally, the most efficient program resulting in the highest benefit for the young adults' independence is microfinance combined with financial literacy training. YCAB might incorporate this last finding in their future strategic initiatives to have the optimum impact in helping underprivileged young adults become independent.

There are some inherent limitations of this study that future research can address. First, it should be noted that this study has a limited scope, i.e., it was only focused on programs' benefit for young adults aged 21-24 years old. The number of beneficiaries who fulfilled these criteria is limited; thus, although the size of the sample is relatively small, the results can be used as a basis for YCAB, and other microfinance institutions when formulating future strategic direction. The use of dimensions other than young adults' independence in evaluating the programs may also be fruitful. Future studies might consider looking at the longer-term horizon since the results of the assessment on the impact and efficiency of these programs may differ. Evidence shows that conclusions drawn when evaluating vocational training are not similar when different time horizons are considered (see for example Forster and Bol Citation2018; Choi, Jeong, and Kim Citation2019; Muja et al. Citation2019).

The second limitation stems from this study's research design, which did not use the experimental approach. Using this approach, where the sample is divided into different groups according to the intervention in this study (i.e. microfinance with and without financial literacy training and different education programs) and examined before and after the interventions, one can establish the impact of these programs more robustly. Hence, it is suggested that an experiment-longitudinal study could be fruitful for those who would like to expand research on this topic.

Also, this study did not collect some information that actually can interfere with the complex relationships between these programs and young adults' independence. Family-specific factors, such as parents' attitude and education-related spending, the availability of employment opportunities, and other environmental factors could be considered by future studies.

In this study, the focus is young adults independence, and the sample is limited to those who were aged 21-24 by the time the survey was conducted. Therefore, the results of this study only reflect the short to intermediate-term impact of the programs.

Acknowledgements

We are very much indebted to Veronica Colondam, Rosita Ariel, and all enumerators from Yayasan Cinta Anak Bangsa (YCAB) for their support in data collection and tabulation. We also thank to Dr. Putu Geniki Lavinia Natih from Trinity College, Oxford University, and Mr. Jean-Salman Marre from University of Glasgow, for their comments, feedback, and assistance. This research is funded by Universitas Indonesia’s grant No. NKB-2036/UN2.RST/HKP.05.00/2020. The authors are responsible for all remaining errors in this article.

Disclosure statements

We declare that this manuscript is original, has not been published before and is not currently being considered for publication elsewhere. We know of no conflict of interest associated with this publication and there has been no significant financial support for this work that could have influenced its outcome.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Rofikoh Rokhim, upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Rofikoh Rokhim

Rofikoh Rokhim is a professor at the Department of Management, Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Indonesia, and the director of Master of Management program in the university. Rofikoh’s research interest covers banking, finance, capital market, good governance, economic crisis, and development of domestic finance, foreign direct investment, micro credit, and other studies. She has published on finance and economic-related issues in several academic journals, including European Journal of Operation Research, Research in International Business and Finance, Journal of Enterprising Communities and Humanomics.

Rofikoh is currently active in several activities outside of the academia, including serving as an independent commissioner at Bank Rakyat Indonesia (BRI) and board member at Article 33 foundation. She was also member of task force in Anti Mafia Migas by Ministry of Energy & Natural Resources and task force Village Fund by Ministry of Village, Transmigration and Remote Area. She was also member of audit and risk management in several companies. She received her doctoral degree with concentration in applied micro and macroeconomics from Université de Paris 1 Pantheon-Sorbonne, France, in 2005.

Arief Wibisono Lubis

Arief Wibisono Lubis is an assistant professor at the Department of Management, Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Indonesia. His research interests are topics related to human development, capability approach, management, finance, and banking. Arief has published in several academic journals, including International Journal of Social and Economics, ASEAN Marketing Journal, and International Journal of Ethics and Systems (formerly Humanomics), and previously served as managing editors of the South East Asian Journal of Management (SEAM) and Indonesian Capital Market Review (ICMR). He is currently the coordinator of international accreditation, Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Indonesia. Arief earned his PhD in Development Studies from the University of Cambridge, United Kingdom, in 2018.

Nadia Novianti

Nadia Novianti is currently a research assistant in Otoritas Jasa Keuangan (OJK), a financial service authority in Indonesia. Before that, she worked in Skha Consulting as research analyst. Nadia graduated and got her bachelor degree from Faculty of Economic and Business, University of Indonesia. Her concentration was Financial Management. Nadia’s research interests especially are in finance and economics field, included banking, microfinance, business, and capital market.

References

- Ariff, M., and L. Can. 2008. “Cost and Profit Efficiency of Chinese Banks: A Non-Parametric Analysis.” China Economic Review 19 (2): 260–273.

- Armendariz, B., and J. Morduch. 2005. The Economics of Microfinance. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Awan, A. G., and D. Kauser. 2015. “Impact of Educated Mother on Academic Achievement of her Children: A Case Study of District Lodhran-Pakistan.” Journal of Literature, Languages and Linguistics 12: 57–65.

- Bannink, R., S. Broeren, J. Heydelberg, E. v Klooster, and H. Raat. 2015. “Psychometric Properties of Self-Sufficiency Assessment Tools in Adolescents in Vocational Education.” BMC Psychology 3 (1): 1–10.

- Behrman, J. R., O. S. Mitchell, C. K. Soo, and D. Bravo. 2012. “How Financial Literacy Affects Household Wealth Accumulation.” American Economic Review 102 (3) : 300–304.

- Behrman, J. R., and S. W. Parker. 2010. “The Impacts of Conditional Cash Transfer programs on education.” In Conditional Cash Transfers in Latin America, edited by M. Adato and J. Hoddinott, 191–211. Washington DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.

- Binder, M., and T. Broekel. 2011. “Applying a Non‐Parametric Efficiency Analysis to Measure Conversion Efficiency in Great Britain.” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 12 (2): 257–281.

- Cassarino-Perez, L., G. Crous, A. Goemans, C. Montserrat, and J. C. Sarriera. 2018. “From Care to Education and Employment: A Meta-Analysis.” Children and Youth Services Review 95: 407–416.

- Cazals, C.,. J.-P. Florens, and L. Simar. 2002. “Nonparametric Frontier Estimation: A Robust Approach.” Journal of Econometrics 106 (1) : 1–25.

- Choi, S., J. Jeong, and S. Kim. 2019. “Impact of Vocational Education and Training on Adult Skills and Employment: An Applied Multilevel Analysis.” International Journal of Educational Development 66: 129–138.

- Chowdhury, Sanjib, Megan Lee Endres, and Crissie Frye. 2019. “The Influence of Knowledge, Experience, and Education on Gender Disparity in Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy.” Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship 31: 1–19.

- Cole, S., T. Sampson, and Z. Bilal. 2011. “Prices or Knowledge? What Drives Demand for Financial Services in Emerging Markets.” Journal of Finance 66 (6) : 1963–1967.

- Deprins, D.,. L. Simar, and H. Tulkens. 1984. “Measuring Labor-Efficiency in Post Offices.” In The Performance of Public Enterprises: Concepts and Measurement, edited by M. Marchand, P. Pestieau, and H. Tulkens, 243–267. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

- Deutsch, J., X. Ramos, and J. Silber. 2003. “Poverty and Inequality of Standard of Living and Quality of Life in Great Britain.” In Advances in Quality-of-Life Theory and Research, Vol. 20, edited by M. J. Sirgy, D. Rahtz, and A. C. Samli, 99–128. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

- Dworsky, A. 2005. “The Economic Self-Sufficiency of Wisconsin’s former foster youth.” Children and Youth Services Review 27 (10): 1085–1118.

- Faas, C., M. J. Benson, and C. E. Kaestle. 2013. “Parent Resources during Adolescence: Effects on Education and Careers in Young Adulthood.” Journal of Youth Studies 16 (2): 151–171.

- Fernandes, D., J. G. Lynch, Jr., and R. G. Netemeyer. 2014. “Financial Literacy, Financial Education, and Downstream Financial Behaviors.” Management Science 60 (8): 1861–1883.

- Flouri, D., and D. Hawkes. 2010. “Ambitious Mothers – Successful Daughters: Mothers' Early Expectations for Children's Education and Children's Earnings and Sense of Control in Adult Life.” British Journal of Educational Psychology 78(3): 411–433.

- Forster, A. G., and T. Bol. 2018. “Vocational Education and Employment Over the Life Course Using a New Measure of Occupational Specificity.” Social Science Research 70: 176–197.

- Gamble, E. N. 2018. “Bang for Buck’ in Microfinance: Wellbeing Mentorship or Business Education?” Journal of Business Venturing Insights 9: 137–144.

- Gates, L. B., S. Pearlmutter, K. Keenan, C. Divver, and P. Gorroochurn. 2018. “Career Readiness Programming for Youth in Foster Care.” Children and Youth Services Review 89: 152–164.

- Halkos, G. E., and N. G. Tzeremes. 2007. “Productivity Efficiency and Firm Size: An Empirical Analysis of Foreign Owned Companies.” International Business Review 16 (6): 713–731.

- Johnston, D., and J. Morduch. 2008. “The Unbanked: Evidence from Indonesia.” The World Bank Economic Review 22 (3): 517–537.

- Kabeer, N. 1999. “Resources, Agency, Achievements: Reflections on the Measurement of Women's Empowerment.” Development and Change 30 (3): 435–464.

- Karlan, D., A. L. Ratan, and J. Zinman. 2014. “Savings by and for the Poor: A Research Review and Agenda.” The Review of income and wealth 60 (1) : 36–78.

- Kato, M. P., and J. Kratzer. 2013. “Empowering Women through Microfinance: Evidence from Tanzatia.” ACRN Journal of Entrepreneurship Perspectives 2(1): 31–59.

- Keh, H. T., and S. Chu. 2003. “Retail Productivity and Scale Economies at the Firm Level: A DEA Approach.” Omega 31 (2): 75–82.

- Khan, A. A., W. Zaki, and I. H. Bokhari. 2017. “Impact of Microfinance on the Involvement of Women in Decision Making and Ownership.” International Journal of Business & Management 12 (2): 61–74.

- Khandker, S. R., and G. B. Koolwal. 2016. “How Has Microcredit Supported Agriculture? Evidence Using Panel Data from Bangladesh.” Agricultural Economics 47 (2): 157–168.

- Kim, Y., E. Ju, R. Rosenberg, and E. M. Farmer. 2019. “Estimating the Effects of Independent Living Services on Educational Attainment and Employment of Foster Care Youth.” Children and Youth Services Review 96: 294–301.

- Korber, M., and D. Oesch. 2019. “Vocational versus General Education: Employment and Earnings over the Life Course in Switzerland.” Advances in Life Course Research 40: 1–13.

- Lusardi, A. 2008. “Financial Literacy: An Essential Tool for Informed Consumer Choice?” Working Paper, Darmouth College.

- Mahmud, S. 2003. “Actually How Empowering Is Microcredit.” Development and Change 34 (4): 577–605.

- Malhotra, A., S. R. Schuler, and C. Boender. 2002. Measuring Women's Empowerment as a Variable in International Development. Washington, DC: Gender and Development Group of the World Bank.

- Mandell, L., and L. S. Klein. 2009. “The Impact of Financial Literacy Education on Subsequent Financial Behavior.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 20 (1): 15–24.

- Miller, A. E., T. D. Green, and K. M. Lambros. 2019. “Foster Parent Self-Care: A Conceptual Model.” Children and Youth Services Review 99: 107–114.

- Monteza, M. D., J. L. Blanco, and M. R. Valdivieso. 2015. “The Educational Microcredit as an Instrument to Enable the Training of Women.” Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 197: 2478–2483.

- Muja, A., L. Blommaert, M. Gesthuizen, and M. H. Wolbers. 2019. “The Role of Different Types of Skills and Signals in Youth Labor Market integration.” Empirical Research in Vocational Education and Training 11 (1): 6.

- Ng, T. W., L. Eby, K. L. Sorensen, and D. C. Feldman. 2005. “Predictors of Objective and Subjective Career Success: A Meta-Analysis.” Personnel Psychology 58 (2): 367–408.

- Park, K. H., and W. L. Weber. 2006. “A Note on Efficiency and Productivity Growth in the Korean Banking Industry, 1992–2002.” Journal of Banking & Finance 30 (8) : 2371–2386.

- Ramos, X., and J. Silber. 2005. “On the Application of Efficiency Analysis to the Study of the Dimensions of Human Development.” Review of Income and Wealth 51 (2): 285–309.

- Rokhim, R.,. G. A. Sikatan, A. W. Lubis, and M. I. Setyawan. 2016. “Does Microcredit Improve Wellbeing? Evidence from Indonesia.” Humanomics 32 (3): 258–274.

- Schaedel, B., F. Azaiza, and R. Hertz-Lazarowitz. 2007. “Mothers as Educators: The Empowerment of Rural Muslim Women in Israel and Their Role in Advancing the Literacy Development of Their Children.” In Schools and Families in Partnership: Looking into the Future. Nicosia, Cyprus.

- Stango, V., and J. Zinman. 2007. “Fuzzy Math and Red Ink: When the Opportunity Cost of Consumption is Not What It Seems.” In Working Paper, Dartmouth College.

- Tauchmann, H. 2012. “Partial Frontier Efficiency Analysis.” The Stata Journal: Promoting Communications on statistics and Stata 12 (3): 461–478.

- Teichler, U. 2015. “Changing Perspectives: The Professional Relevance of Higher Education on the Way Towards the Highly‐Educated Society.” European Journal of Education 50 (4): 461–477.

- Thanh, P. T., K. Saito, and P. B. Duong. 2019. “Impact of Microcredit on Rural Household Welfare and Economic Growth in Vietnam.” Journal of Policy Modeling 41 (1): 120–139.

- Tulkens, H. 1993. “On FDH Efficiency Analysis: Some Methodological Issues and Applications to Retail Banking, Courts, and Urban Transit.” Journal of Productivity Analysis 4 (1–2) : 183–210.

- UNFPA. 2014. Indonesian Youth of 21st Century. Jakarta: UNFPA Indonesia.

- World Bank. 2020. World Development Indicators [Data file]. http://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators

- Yadav, P. D., and A. Verma. 2015. “Exploring the Dimensions of Women Empowerment among Microfinance Beneficiaries in India: An Empirical Study in Delhi-NCR.” Journal of Applied Management and Investments 4 (4): 260–270.