Abstract

Business Model (BM) tools are essential for start-ups to innovate and succeed, however, there is a gap between academic research and real-world application. Our study explores how start-ups use BM tools, using case studies and interviews with founders. We found two main patterns: Reactive Iteration, where start-ups use BM tools selectively in response to specific needs, and Adaptive Training, where hands-on mentor-led learning is preferred over theoretical models. Start-ups often focus on product development first, causing inconsistencies in their use of BM tools. Our research highlights the need to adapt BM tools to the practical realities of start-ups, ensuring they are both conceptually rigorous and practically relevant. This adaptation is key to helping entrepreneurs effectively use BM tools for innovation and growth.

RÉSUMÉ

Les outils de modélisation d’entreprise (ME) sont essentiels pour permettre aux start-ups d’innover et de réussir, mais il existe un fossé entre la recherche universitaire et leur application au monde réel. Note étude explore la manière dont les start-ups utilisent les outils de ME, à l’aide d’études de cas et d’entretiens avec des fondateurs d’entreprises. Deux modèles principaux ont émergé de notre étude: l’itération réactive, où les start-ups utilisent des outils de ME de manière sélective en réponse à des besoins spécifiques, et la formation adaptative, où l’apprentissage pratique dirigé par un mentor est préféré aux modèles théoriques. Les start-ups se concentrent souvent et en premier lieu sur le développement de produits, ce qui entraîne des incohérences dans l’utilisation des outils de ME. Notre recherche met en évidence la nécessité d’adapter les outils de ME aux réalités pratiques des start-ups, en veillant à ce qu’ils soient à la fois rigoureux sur le plan conceptuel et pertinents sur le plan pratique. Cette adaptation est essentielle pour aider les entrepreneurs à utiliser efficacement les outils de ME pour l’innovation et la croissance.

1. Introduction

Understanding how start-ups utilize Business Model (BM) tools is crucial for bridging the gap between academic theory and practical application, which is vital for fostering innovation and success in entrepreneurial ventures. Despite the abundance of research on BM frameworks, a disconnect persists between theoretical models and their practical application in start-ups. Our study addresses this gap by investigating the use of BM tools among start-ups through multiple case studies and semi-structured interviews with founders. Our findings reveal two key phenomena: Reactive Iteration, where start-ups engage with BM tools selectively in response to specific triggers, and Adaptive Training, which prioritizes practical, mentor-led learning over theoretical frameworks. These insights highlight the need for adapting BM tools to the dynamic realities of start-ups, ensuring they are both conceptually rigorous and practically relevant. By examining these patterns, we aim to provide actionable recommendations to enhance the effectiveness of BM tools in driving innovation and growth in start-up environments.

A business model (BM) describes an articulated set of activities (Foss and Saebi Citation2018), outlining how a firm creates and delivers value (George and Bock Citation2011). Not all BMs are based on innovation – however, the design of the BM is especially relevant in new ventures (Jin and Shin Citation2020; Yu, Zhang, and Liu Citation2019) and entrepreneurial start-ups (Bocken and Snihur Citation2020; Slávik Citation2019). Designing an effective BM and managing business model innovation (BMI) to underpin a firm’s long-term success (Miller et al. Citation2021) has resonance for both practitioners (Skog, Wimelius, and Sandberg Citation2018) and scholars (Schmidt and van der Sijde Citation2022).

Although the BM concept is no longer an emerging field, prior research shows an ongoing misalignment between theory and practice (Baden-Fuller and Haefliger Citation2013; Do Vale, Collin-Lachaud, and Lecocq Citation2021; Farquhar et al. Citation2024; Ingstrup, Aarikka-Stenroos, and Adlin Citation2021). A better understanding of BM development may support early ventures in approaching their strategies more systematically. Also, incumbent firms may be able to derive insights from BM development that enables them to sustain their competitive advantages (Caputo et al. Citation2021; Climent and Haftor Citation2021; Zott, Amit, and Massa Citation2011), for which a BM must be ‘something more than just a good logical way of doing business. A sustainable model must meet particular customer needs’ (de Faria, Santos, and Zaidan Citation2021, 99).

We position our work within the stream of literature on university-based entrepreneurship education (cf., Kumar et al. Citation2021; Shirokova, Osiyevskyy, and Bogatyreva Citation2016). We argue that certain facets of entrepreneurship have been neglected, notably how start-ups can use BM tools for BM innovation. Indeed, BM tools (such as frameworks, models, methods and IT support) play a key role in BMI by facilitating knowledge-sharing among different actors (Schwarz and Legner Citation2020). The existing literature reveals a relative neglect of start-ups in academic research on BM and BMI. Haase and Eberl (Citation2019) suggest that this neglect is caused by start-ups lacking well‐embedded routines that more established organizations can rely on for building resilience; start-ups need to first create and maintain such routines.

Scholars often present a structured methodology or roadmap for BM development and design (Bachmann and Jodlbauer Citation2023). Owing to small size and resource constraints, start-ups often have decentralised, informal decision-making without structured processes (Blank and Dorf Citation2020). However, the BM literature recommends adopting systematic tools and methodologies to increase entrepreneurs’ chances of success (Baden-Fuller and Haefliger Citation2013; George and Bock Citation2011). This creates a mismatch between the conceptual rigor advocated by scholars (cf., Kumar et al. Citation2021) versus start-ups’ inherent preference for agile, action-oriented learning-by-doing (Ries Citation2011). As our findings reveal, entrepreneurs prefer simple experimental iterations based on real-time feedback, rather than relying on textbook tools and academic frameworks that seem less evidence-based.

In practice, business models often lack consistent terminology and critical components, and are often confused with organisational strategy (Sanchez and Ricart Citation2010). Despite research interest in BM and BMI, a number of gaps in knowledge remain (Budler, Župič, and Trkman Citation2021; Caputo et al. Citation2021), stemming from the focus on descriptive matters (value creation, delivery and capturing) to the detriment of practical matters (Zott and Amit Citation2017). This observation highlights the limitations of BM theorizing. It calls for efforts to focus on BM thinking that is fit-for-purpose (Baden-Fuller and Haefliger Citation2013; de Faria, Santos, and Zaidan Citation2021). Such information is particularly relevant for start-ups, which operate in highly uncertain environments yet require systematic, evidence-based approaches to BM design in order to translate innovations into commercial success (Paradkar, Knight, and Hansen Citation2015). However, relatively little investigation has focused on how start-ups make use of BM tools and frameworks (Griva et al. Citation2023). Our aim is to help bridge this divide by exploring how start-ups use business model tools, from which we provide recommendations to enhance BMI.

Set in the context of the University of Toronto’s co-working initiative, we examine the misalignment between university-based entrepreneurship reported in the literature and business practice (Ingstrup, Aarikka-Stenroos, and Adlin Citation2021). In doing so, we draw from Ratten et al. (Citation2023) to respond to the call for further research made by Salamzadeh et al. (Citation2022) to investigate why many start-ups struggle to develop a robust BM that can stand the test of time (Payne et al. Citation2020).

Drawing from multiple sources of data, the following research question is developed:

Given the misalignment between academic literature and business practice, how do entrepreneurial start-ups make use of BM tools?

Against this backdrop, we empirically examine how start-ups make use of BM frameworks, to identify where and how existing tools and methodologies require adjustment to become more relevant. Our study assesses the usefulness, functionality and effectiveness of BM tools, by reviewing how they are being used in start-ups, thereby identifying challenges and areas for improvement, as well as contributing to the practical aspects of BM research. Based on these insights, we make recommendations on the most effective ways that a start-up entrepreneur can approach the more technical aspects of BM design and BMI.

Through our investigation, we make several contributions to the existing literature. We address a notable gap in academic discourse, offering fresh perspectives on the alignment between scholarly work and business practices. This gap has important implications; it suggests that the existing literature may not sufficiently address practical concerns, limiting its applicability to the complexities of actual business environments. Bridging the gap is crucial for enhancing BM effectiveness. By incorporating practical insights, researchers can contribute to the development of BM that are theoretically sound and relevant for informing decision-making in real-world business settings. The gap underscores the need for BM thinking that is ‘fit-for-purpose’, which implies that BM and theoretical frameworks should not only be academically rigorous but also tailored to meet the practical needs and challenges faced by businesses.

Our findings also inspire the debate about the optimal BM framework, questioning the feasibility of a universal approach versus the need for contextual adjustments. Closing the gap in BM literature is particularly relevant to start-ups, as it provides them with practical insights for sustainable growth, operational guidance and present-day frameworks that can inform decision-making and help build resilience to address the challenges of developing a new entrepreneurial venture (Corral de Zubielqui and Jones Citation2020). Beyond theoretical insights, we provide practical recommendations tailored for start-ups, aimed at maximizing the potential of BM tools and BMI by equipping start-ups with strategies to ensure sustainable success.

In line with Farquhar et al. (Citation2024), an exploratory research approach was designed to gather data by semi-structured interviews using a multiple case study design methodology. A mixture of deductive and inductive approach was deployed during the analysis of the data. Cases were selected using a Snowball sampling methodology. Data were analyzed using the Gioia Method, by reviewing the material and developing categories based on interviewee verbatim (Elliott Citation2018).

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. We begin by reviewing the literature on BM and BMI, highlighting the misalignment between academic research and start-up practices. We then outline our methodology, detailing the multiple case study approach and data analysis using the Gioia Method. Next, we present our findings, discussing the phenomena of Reactive Iteration and Adaptive Training. Finally, we discuss the implications of our study, provide recommendations for start-ups, and conclude with limitations and future research directions.

2. Literature review

Drawing from Ingstrup, Aarikka-Stenroos, and Adlin (Citation2021) and Farquhar et al. (Citation2024), we begin by explaining the misalignment between academic literature and business practice regarding BM. This stems from various factors. The dynamic pace of change in modern business environments, fueled by technology and globalization, poses a challenge for academic literature to keep up, resulting in a lag between emerging business practices and their incorporation into research. The academic focus, which prioritizes the development of robust models, rarely aligns with the immediate, practical concerns and fast decision-making required in real-world business settings. Moreover, publication timelines exacerbate the disconnect, as the time-consuming process of research, peer review, and publication can lead to outdated insights. Incentives in academia, emphasizing theoretical contributions, may undervalue immediate practical applicability for practitioners. Data limitations, often relying on past data, can hinder the representation of cutting-edge business strategies. The interdisciplinary nature of business models, spanning economics, strategy, marketing, and technology, poses a challenge for comprehensive coverage in academic literature. Communication barriers between academia and industry, including differences in language and dissemination channels, further contribute to this misalignment. Finally, risk aversion in academia, prioritizing rigor and generalizable findings, contrasts with the experimental and risk-taking nature of start-ups. Addressing this misalignment requires a more agile and collaborate approach to academic publishing to ensure theoretical insights remain relevant and applicable in the rapidly changing business landscape.

In the literature on BM and BMI, there is a lack of consensus on defining the terms ‘start-up’ and ‘business model’ (Magretta Citation2002) – which has hampered attempts to empirically test and theorize (Foss and Saebi Citation2018). There are also a number of inconsistencies with regards to factors relating to start-up BM and BMI, which complicates the understanding of key concepts. Acknowledging the various frameworks used by entrepreneurs to facilitate BM design and BMI, studies suggest that the high failure rate among start-ups is due to the lack of product-market fit, conflicts among founding partners, competition, lack of financial resources, and high uncertainty. In the case of cutting-edge innovative start-ups, the inability to commercialize value created (due to poor BM design) was found to hamper long-term success (Paradkar, Knight, and Hansen Citation2015). Thus, a robust architecture of how value should be created, delivered, and appropriated is vital to improve the chances of success (George and Bock Citation2011; Teece Citation2010).

Various definitions of a ‘start-up’ exist in the literature. Katila, Chen, and Piezunka (Citation2012) define a start-up as a company or project developed by an entrepreneur who would like to create and validate a scalable BM, whereas Ries (Citation2011) emphasizes its operation under conditions of serious uncertainty. Örnek and Danyal (Citation2015) link the term to technology ventures. Zamani et al. (Citation2021) found that start-ups are increasingly using a data-driven BM and are required to use cutting-edge techniques and methods to achieve and maintain their competitive advantage. Such ventures’ inherent uncertainties reportedly account for their high attrition rate within the first few years (Schmitt et al. Citation2018).

Multiple factors cause start-up failure including: lack of a systematic process for discovering markets, customer identification, and hypothesis validation (Trimi and Berbegal-Mirabent Citation2012); lack of financial resources and intense competition (Velu and Jacob Citation2016); interpersonal conflicts among founders (Paradkar, Knight, and Hansen Citation2015); lack of cohesion between the strong direction of a founder’s vision and the need for redirection that follows from market feedback (de Faria, Santos, and Zaidan Citation2021); ineffective project selection and prioritization, which are implicitly influenced by the start-up’s strategy and business model (Zamani et al. Citation2021); early-stage underestimation of unexpected obstacles in the entrepreneurship journey (Joseph, Aboobaker, and Zakkariya Citation2023; Suntornpithug and Suntornpithug Citation2008).

A BM is useful for ensuring that value is captured from innovation (George and Bock Citation2011; Teece Citation2010). Theories on BM emphasize the architecture that governs value creation, delivery, and appropriation (Do Vale, Collin-Lachaud, and Lecocq Citation2021; Gassmann, Frankenberger, and Michaela Citation2014). Indeed, Foss and Saebi (Citation2018) argue that Teece’s (Citation2010) widely-cited definition of a BM be adopted as a basis for a much-needed depersonalization of the BM and BMI constructs. This could be augmented by defining the constructs using visual aids, pioneered by the firm Strategyzer (Citation2020). (below) summarizes key concepts used in the literature.

Table 1. Key concepts.

Studies show that in order to successfully commercialize innovation, start-ups need to leverage their dynamic capabilities and improve access to complementary resources (Röhl Citation2019; Do Vale, Collin-Lachaud, and Lecocq Citation2021). However, scholars note the lack of fit between academic conceptualizations of BM and how BM are actually designed and implemented in practice. For example, Baden-Fuller and Haefliger (Citation2013) argue that BM research has been long on definitions and descriptions but short on prescriptions and tools for application, contributing to managers struggling with translating BM theory into practice.

Sanchez and Ricart (Citation2010) suggest that the proliferation of definitions, components and terms in scholarly BM research has produced confusion among practitioners attempting to undertake BMI; conflicting conceptualizations of what constitutes a BM pose barriers to effectively leveraging academic knowledge. Also, BM research has focused more on what a BM represents than on how those representations might assist management practice (Zott and Amit Citation2017), which indicates a divide between ideational BM scholarship and applied, problem-focused managerial priorities. The scholarly focus on descriptive accuracy over functional utility points to the need to better align theory with practice (de Faria, Santos, and Zaidan Citation2021) – hence the need to empirically examine how start-ups interface with academic BM theories and tools on the ground. By exploring if and how start-ups use such methodologies, our study provides vital evidence to substantiate claims of misalignment while uncovering tangible directions for improvement. We build on identified gaps by highlighting where dominant BM frameworks fall short or could be further attuned to entrepreneurial start-up contexts.

Business success requires a combination of technological innovation and a successful BM (Chesbrough Citation2010; Paradkar, Knight, and Hansen Citation2015; Velu and Jacob Citation2016), framed by a strong ‘can-do’ attitude and a start-up-friendly environment (Röhl Citation2019). Although BM have been linked to increased performance and chances of entrepreneurial success, it is worth noting that ‘a mediocre technology pursued within a great business model may be more valuable that a great technology exploited via a mediocre business model’ (Chesbrough Citation2010, 355), which resonates with more recent studies (de Faria, Santos, and Zaidan Citation2021; Do Vale, Collin-Lachaud, and Lecocq Citation2021).

BM frameworks provide a formal, conceptual structure that describe the components, elements, and relationships of a BM (Teece Citation2010). However, relying solely on these frameworks may not foster genuine innovation (George and Bock Citation2011). From the many BM and BMI frameworks that currently exist, we focus on six leading tools that offer broad insights into BMI, then we examine their relevance for start-ups. Further details of the Business Model Canvas (BMC), Lean Canvas, Value Model Canvas, Fluid Model Canvas, Value Proposition Canvas (VPC) and Business Model Navigator are presented in Appendix A.

Organizations may also make use of improvement tools, especially for Planning, Quality Control, and performance measurement, which has enabled scholars to report on how organizations integrate these tools into their operational frameworks. However, while the literature emphasizes the strategic importance of effective planning methodologies, highlighting the role of tools in facilitating systematic goal-setting and resource allocation, to align with broader goals of organizational excellence and competitiveness (Jochem, Menrath, and Landgraf Citation2010), these tools are less accessible to start-ups (Velu and Jacob Citation2016). Furthermore, the smaller and informal nature of start-ups significantly influences the adoption dynamics (Haase and Eberl Citation2019), often enabling faster decision-making without bureaucratic hurdles. Yet, this informality also poses challenges, as the lack of formal structures may lead to limited documentation and clarity in the decision-making process (Blank and Dorf Citation2020).

While leading BM frameworks portray elements in static mode (Blank Citation2003), start-ups need dynamic approaches adapted to revision cycles, as their informal models move toward formalization (Budler, Župič, and Trkman Citation2021). Moreover, existing tools emphasize later-stage scaling or sustainability concerns, often overlooking obstacles relevant for start-ups such as achieving product-market fit, initiating traction and transitioning from concept to commercialization (Suntornpithug and Suntornpithug Citation2008). The limited resources of start-ups clearly distinguish their BM needs from established firms (Paradkar, Knight, and Hansen Citation2015), yet the leading frameworks rarely address this constraint. Diverse factors also shape the ability of a start-up founder to implement BM methodologies, including their backgrounds, personality, motivation and current trends. However, scholars disproportionately focus on large or incumbent firms. To investigate this further and thereby address our research question, we develop four sub-queries:

At what stage of a start-up is working on a business model important?

What are the weaknesses of business model tools?

For what purpose are business model tools or frameworks used in start-ups?

How can BM tools be improved?

The four sub-research questions posed above directly relate to and follow from the main research question presented in the introduction: Given the misalignment between academic literature and business practice, how do entrepreneurial start-ups make use of BM tools? This study aims to capture start-up entrepreneurs’ perceptions of these key aspects by investigating: (i) the stage(s) where BM development is important for start-ups, (ii) the weaknesses of current BM tools, (iii) the purposes for which start-ups use BM tools, and (iv) how BM tools can be improved. Examining these sub-questions will shed light on the overarching question of BM tool usage in the context of literature-practice gaps, allowing for a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon.

The methodology for addressing the research question is set out below.

3. Methodology

Following Yin (Citation2012), we use an empirical social research approach to facilitate an in-depth exploration of a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context. The use of multiple case studies potentially reinforces generalizing results (Farquhar Citation2012). Our intention was to examine the early-stage BM process undertaken by start-ups in a real-life context, to ascertain if the factors that deter BM usage in start-ups are different based on the context informed by the national context. An interpretive research approach gives voice in the interpretation of events in a first-order analysis to the people actually experiencing those events, as advocated Yin (Citation2012) and Farquhar (Citation2012). While exploratory theory building starts with little or no theory under consideration and no hypothesis to test (since preordained theoretical perspectives or propositions may bias and limit the findings), we acknowledge the issues of a ‘blank slate’ (Urquhart and Fernández Citation2013). Thus, although inductive reasoning is used in this study, there are elements of deductive reasoning.

Data were collected in Canada from ONRamp, which is the University of Toronto’s flagship co-working initiative that provides facilities and support for the university’s entrepreneurial community. The location of this incubator allows entrepreneurs to be immersed in the epicenter of entrepreneurial activity that exists in Toronto; 31 start-ups were interviewed. For each start-up, only one founding entrepreneur was interviewed. In instances where there are several co-founders, the person in the higher managerial position was interviewed.

The interview guide employed by the researchers was formulated based on insights gleaned from the literature review of business model definitions and related concepts, summarized in . Prior to launch, the survey was pilot-tested with 10 founders (chosen randomly) to verify the clarity and suitability of the questions, evidenced by the respondents’ interpretation of the logic in the question sequencing (Zikmund Citation2003). To avoid compromising the validity of the study, the qualifying criteria to participate were that (i) start-ups must have used at least one BM tool in their business, and that (ii) participants must be in decision-making positions.

Given that this research involves human subjects, we set out to obtain ethical approval from each founder. In line with Pietilä et al. (Citation2020), the participants were emailed full details of the study and notified that they could withdraw at any time. Those interested in participating in the study met the researchers face-to-face to give written consent for participating (see consent letter in Appendix B). The participants were advised of their rights in the research process in line with the Academy of Management (Citation2021) regarding responsibility, integrity, professional conduct and respect for people’s rights and dignity. No identifying information was given about the start-ups; the participants were referred to as ‘founder’ throughout.

Prior to the interviews, the researchers solicited permission from each respondent before any recording took place. All interviews were recorded using the iPhone app ‘Voice Memos’, owing to recording qualities. The audio recordings were transcribed and stored on an external storage device. One of the most effective ways of analyzing qualitative data in management sciences is to use coding, as the codes embody the meaning in verbatim (Farquhar Citation2012).

A non-probability sampling technique was used for data collection as, it allows for flexibility Zikmund (Citation2003). Purposive sampling was used to prioritize start-ups which are still in the ideation phase (ie when brainstorming takes place), with the aim of understanding if start-ups use BM tools to forge their business models. Face-to-face, semi-structured interviews were conducted with founders in February 2023. A semi-structured interview procedure was employed to ensure consistency across all participants while allowing some room for participants to express their idiosyncratic experiences of using BM tools.

Thus, the interview transcripts were thematically analyzed manually through Template Analysis, following the methodology proposed by King, Horrocks, and Brooks (Citation2018), whereby each recorded data item received equal consideration, with the use of colored highlighting for annotating transcripts. This initial process aimed to identify potential patterns or themes related to start-ups. Special attention was given to the contextual nuances surrounding the data to prevent overlooking relevant information (Bryman Citation2016). The work of Hennink and Kaiser (Citation2021) serves as a reminder that the quality and depth of analysis undertaken by the researcher will deteriorate with each additional interview conducted after the saturation point is reached. Thus, we carefully analyzed the data to ensure that the sample was large enough to be classified as representative of the population and then left out any additional data after saturation is reached.

Following the Gioia method (Gioia et al. Citation2013), data analysis was undertaken using a three-tiered coding system, taking an approach similar to Magnani and Gioia (Citation2023) and Farquhar et al. (Citation2024), who used this method in entrepreneurship research. In the first stage of the analysis, the researchers independently read and coded the interviewee comments, which were then organised manually into a set of 1st-order concepts, consistent with the expressions and narratives articulated by the interviewees. The next stage involved a 2nd-order analysis whereby the researchers sought to make sense of links between the data and new concepts. This ‘sense making’ provides an opportunity for concept development and theory building (Gioia and Chittipeddi Citation1991). In the final stage, the researchers aggregated key themes to provide two summative dimensions – Reactive Iteration and Adaptive Training – thus, forming a data structure (see ). The term Reactive Iteration describes how start-ups continually refine and adapt strategy based on pragmatic responses to challenges and opportunities), while Adaptive Training refers to going beyond theoretical delivery, by incorporating practical, mentor-led education to enhance the effective use of BM tools.

Table 2. Data structure.

Compared with other methods for analysis, such as content analysis, the Gioia method allows for alternative theoretical explanations to emerge from the data and has been used effectively to understand consumption patterns related to entrepreneurship research.

4. Findings and analysis

The initial sample included 31 start-ups. After 12 interviews, a saturation point was reached. Dey (Citation1999) defined saturation as the moment at which data collection becomes ‘counterproductive’ and ‘the new’ no longer contributes to the larger story, model, or theory. Hennink and Kaiser (Citation2021) found that saturation in qualitative research is commonly reached between 9 and 17 interviews or 4–8 focus group discussions.

In line with Magnani and Gioia (Citation2023) and Farquhar et al. (Citation2024), the findings are supported by quotes, providing a broad view of the challenges and opportunities associated with BM tools in the startup ecosystem. Studying these aspects provides valuable insights into how the size and informality of start-ups can shape their approach to adopting improvement tools ().

Table 3. Stage in which BM development starts (exemplary quotes).

RQ 1: At what stage of a start-up is working on a business model important?

RQ 1 sought to establish the stage at which working on a business model is important for a start-up. Some entrepreneurs indicated that although they never worked holistically on their business model in a formal sense or used the BMC to map out the business, they were continually working on parts of the business model; for example, when the entrepreneur realizes that inputs are needed in the development of a product. In that instance, the question of cost (and the ‘cost block’ of the BMC) is affected.

The findings show that the entrepreneurs focus primarily on product or service development (the value proposition block of the BMC) which was expected, given that the interviewees were mostly from engineering or science backgrounds. This finding is in line with Teece (Citation2010) who found that start-up entrepreneurs with a technical or science background tend to prioritize the product or solution to the problem that is being solved. Taking the BMC as a reference, most entrepreneurs worked on the value proposition block from the very beginning.

The only time that entrepreneurs take time to write down every aspect of the business model is when they are forced to do so – for example, when a mentor suggests mapping out the BMC, or when an investor asks to see the business model, or in preparation for attending a workshop. Otherwise, entrepreneurs seem to work on their business model as the need arises.

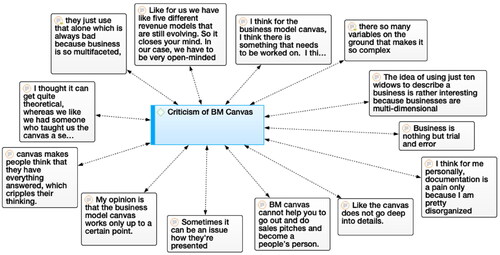

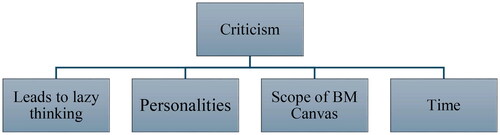

RQ 2: What are the weaknesses of business model tools?

This RQ sought to elicit the entrepreneurs’ attitudes towards BM frameworks ().

What emerged from the interviews is the fear that relying on systematic tools such as the BMC may retard the thought process, as Founder 1 voiced:

I think that the business model canvas makes people think that they have everything answered, which cripples their thinking… we have five different revenue models that are still evolving. So, it closes your mind. In our case, we have to be very open-minded.

I think for me personally, documentation is a pain only because I am pretty disorganized.

for me, documenting and formalizing things is hard and I guess the same goes for a lot of founders who are working over 12 hours a day… writing things down is the last thing you want to do when you could be spending time thinking about how to make money – it drains me.

Interestingly, Founder 3 commented:

in entrepreneurship, there’s a kind of romanticizing of being super busy. And I think the best way to approach it is to ask yourself: is my time well spent? And I’d say, time spend doing a business model canvas is probably better spent than you doing all other things because frankly if you haven’t really nailed those things down, then a lot of the time you are spending is wasted because you are heading in the wrong direction.

it’s important to have a platform with all basic instruments and tools, this would be really priceless!

Yes, we need such models and tools which should help to analyze what is happening and bring detailed recommendations.

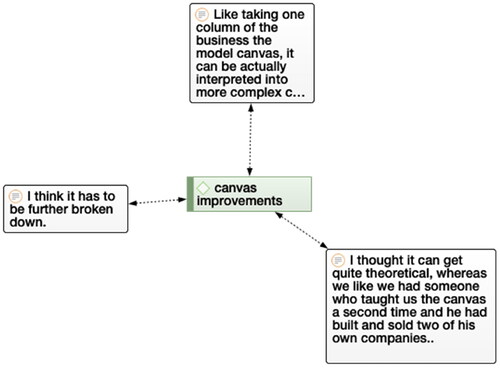

it has to be more open… the idea of using only nine windows to describe a business is constraining because businesses are multi-dimensional.

the canvas doesn’t go deep enough into detail… it should be further broken down, taking one column and interpreting it as more complex columns because business is complex.

Although this RQ sought to elicit negative interpretations of BM tools (see ), it also identified challenges that entrepreneurs experience while using BM tools.

4.1. Lazy thinking

There is a concern that relying on systematic tools such as the BMC may stymie thinking. One founder illustrated the issue thus: ‘I’m always alarmed when I see some of my interns referring to a textbook for everything’. Entrepreneurs are concerned that textbook tools threaten their ability to be artistic and creative. The LEGO® Learning Institute (Citation2009) describes creativity as the ability to form ideas or artefacts that are new, surprising and valuable; creativity is often misunderstood to be a single ability, whereas in reality, it is a multi-faceted concept. Research suggests that systems are crucial for creativity, and for channeling creativity into ideas or artefacts in a way that can be understood by ourselves and others. Scholars distinguish systems of science (for channeling creativity into solving specific problems as in entrepreneurship and business) from systems of art (channeling creativity into unique expressions, giving form to imagination, feelings and identities as in painting, music or sculpture.

Comberg et al. (Citation2014) put forward that one reason why start-ups fail is they lack a systematic process for discovering their markets and testing their assumptions. The results of this study indicate that the frameworks assist start-ups by guiding their thinking to consider the aspects of a business model. Frankenberger et al. (Citation2013) suggest that the BMC was designed to guide firms towards a systematic approach to creating a business model. This study thus supports the notion that business model frameworks provide a systematic structure and process for firms to develop their business models – however, this does not prove if such deployment would result in higher success rates of entrepreneurial initiatives.

While it is important that entrepreneurs succeed in their projects (ie one of the reasons they are encouraged to use BM tools), it is also worth noting that some people may set up a start-up for fun or for pleasure. Thus, tools or frameworks may take the enjoyment out of this rather creative and artistic process – which could explain the discomfort that entrepreneurs experience once they are required to engage in systematic activities. The data show that entrepreneurs prefer to undertake operational activities as they feel is necessary, and not according to fixed guidelines. Often, the incentive for becoming an entrepreneur is the dislike of fixed parameters, and the preference to take responsibility for one’s own initiatives (Aziz et al. Citation2013).

4.2. Personality

Besides the entrepreneur’s background, their personality was found to have an impact on what they prioritized during start-up development. Entrepreneurs who are less organised generally disliked working on frameworks or following structured processes.

4.3. Time

Speed-to-market is often cited as one of the biggest threats to start-ups (Frankenberger et al. Citation2013). Being first to market and tackling competitors can sift the winners from the losers. To that end, entrepreneurs are careful about how they spend their time. If an activity does not seem urgent, they will put it aside and focus on what they deem to be more urgent – ie opportunity cost. The profound realization is that entrepreneurs need to be able to see enough value in pursuing BMI if they are going to give up other activities and make time to work on this area.

4.4. Scope

The scope of BM tools has been widely debated in the literature (George and Bock Citation2011; Osterwalder and Pigneur Citation2010; Teece Citation2010). Attempts have been made to make the BMC more practical, based on concerns regarding the ‘learning’ aspect (Kumar et al. Citation2021), which is a vital component during the early stages of a start-up, particularly given that new ventures operate in a highly uncertain environment. Thus, Maurya (Citation2012) developed the Lean Canvas as an actionable and constructive tool to direct the entrepreneur ().

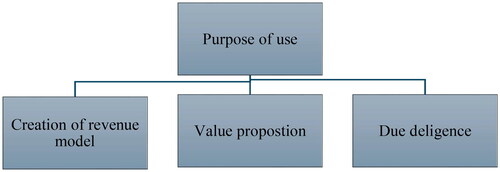

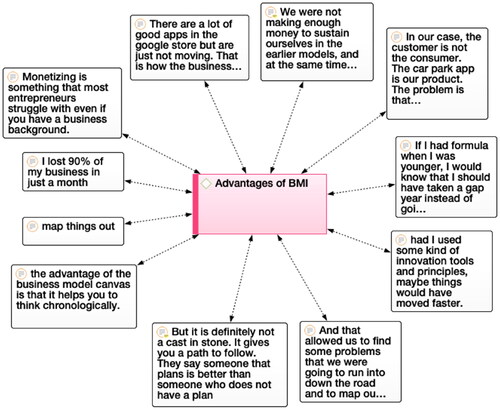

RQ 3: For what purpose are the business model tools or frameworks used in start-ups?

Founders of app-based start-ups (ie using apps as a primary component of their value proposition) showed a higher appreciation of BM tools. A common problem encountered is that users are often reluctant to pay for apps. Founder 2, who built an app to help car owners locate their vehicle in a public carpark, explained this problem:

in our case, the customer is not the consumer. The carpark app is our product. The problem is that users are willing to use the app, but they’re not willing to pay for it. So, we needed to change the business model, as most technopreneurs experience.

we’re working on a couple of pilot projects to validate the revenue model but essentially figuring out how to make money is the tough part of entrepreneurship, for me at least, because I’m from a science background.

we worked on our business model from the very beginning, because it’s a big part of our value proposition.

it gives you a path to follow, from start to finish, meaning that you need to have tactics to move from A to B so that when competitors start to jump in, you know that you’re going from A to Z, and you just let them be. And that’s what the business model allows you to see, the entire picture and not be too frustrated by the surrounding movement.

I’m one of the people that believe that there’s no competition in business. Everybody has a unique strategy. It’s about playing out strategies. That’s why we have Apple and Samsung and so forth. It’s essential to focus on making the customer happy and delivering value.

And that allowed us to identify some problems that we were going to encounter down the road and to map out whether we could scale or not.

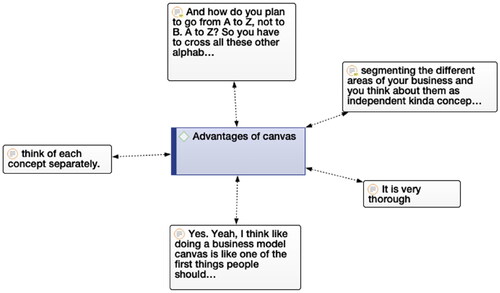

it helped in segmenting the different areas of our business and you think about them as independent concepts. It’s very thorough… there are discrete concepts where otherwise you just think things are not working, what do I have to change? That’s the way that I think it helped us. It really allows you to think of each concept separately.

Financial capital availability in the entrepreneurial ecosystem was also cited. For Founder 4,

despite the high number of start-ups, there’s abundant sources of capital… just enough to go around.

In terms of how capital availability affects the urgency of the work on business models, Founder 2 stated:

I’d say monetizing is a pretty urgent thing for all start-ups because you can have access to non-diluted funding but in order to get the investment, you need to make money. And in order for you to pay yourself, you still need to make money.

I’m within striking distance of good external funding, which is great but we’re bootstrapped otherwise, and most businesses should expect this as the default mode. Canada offers a reasonably effective social safety net, which makes it possible to take the risk to start a business.

I had a stipend when I was doing my grad studies, so the university paid me to study which I know is a luxury compared to many other countries then I realized that I wanted to do entrepreneurship in the middle of my master’s so I lived on my stipend… but today, my company is self-funded though we also have the bonus of supporting start-up grants and micro-financing.

When I was at the very beginning of my business, I attended a meeting with investors who told me – you should earn at least a dollar at first. It is not possible to raise money before customers start paying for your product.

because we’re building a marketplace, people often give leniency to that. So, if you’re supporting growth you don’t have to monetize right away, particularly in the software industry in North America.

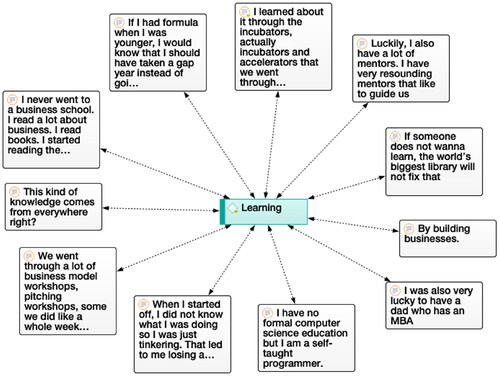

I learned about it through the incubator and accelerator that we went through. I didn’t know about it before.

it could get quite theoretical in the classroom, then we had someone who taught us the canvas a second time and he had built and sold two of his own companies and bankrupted one of them. He’d been through this three times so he could give us a little more grounded realism into what we should look for and how to innovate.

Below, summarizes how entrepreneurs learnt about BM.

Table 4. How entrepreneurs learned about tools for BM (exemplary quotes).

This RQ sought to explore the specific application or instances in which entrepreneurs find that there is a need to use business model tools.

4.5. Creation of revenue model

Our findings show that entrepreneurs are more frustrated by the revenue model than other parts of their business models. Founders of app-based start-ups were very enthusiastic to discuss the topic of creating business models, as they had experienced challenges associated with business model design very early in their journey. Users of digital products (such as apps) are accustomed to not having to pay for the use of such products. Traditionally, start-ups traded customer data for some revenue from advertisers. This type of business model has been threatened as customers are increasingly concerned about the use of the data gathered from them by internet companies (Buchalcevová and Mysliveček Citation2016). Policy-makers are now implementing stricter laws to regulate the practice of trading data received or logged from customers by internet companies. This adds a new constraint for entrepreneurs, forcing start-ups to rethink their business models. During the search for solutions, the entrepreneurs in our study came across tools such as BMC.

4.6. Value proposition

The literature offers little explanation as to whether an aspiring entrepreneur (who does not have a business idea but is convinced that they want to start a business) can start with a blank canvas and experiment with tools such as the BMC to come up with an idea for a start-up. Our data suggests that a unique business model can in itself be a start-up’s value proposition. This is confirmed by Gassmann, Frankenberger, and Michaela (Citation2014) who assert that only a few phenomena are really new. Often, innovations are merely minor changes of something that already exists elsewhere, either in another market or sector. Having examined several hundred BMIs, Gassmann, Frankenberger, and Michaela (Citation2014) found that some 90% of the innovations were a recombination of previously existing business model concepts; hence their identification of 55 repetitive patterns that form the core of most business models.

4.7. Roadmapping

One of the key issues that the business model is intended to address is the communication aspect of the business model. Prior to its creation, it is difficult for most entrepreneurs to communicate their business models. The BMC harnesses the power of visualization to communicate a message. This attribute and other useful attributes of the business model were not discussed by the sampled entrepreneurs. Overall, the BMC was interpreted as a roadmap or visual substitute for the traditional business plan – only less detailed. The lack of comments regarding the other benefits of the business model is concerning because if the entrepreneurs cannot realize the full potential of the tool then they will most likely not take full advantage of it. This may also result in lower adoption and/or frequency of use in the context of a start-up.

4.8. Due diligence

Our sample of entrepreneurs stated that the business model allowed them to think of every aspect of the business, independently. This allowed them to do the necessary due diligence and thus avoid overlooking vital aspects. The BM tools such as the BMC allowed the entrepreneurs to map out their assumptions on paper and contemplate them, then share them with the rest of the team, challenge and test them ( and ).

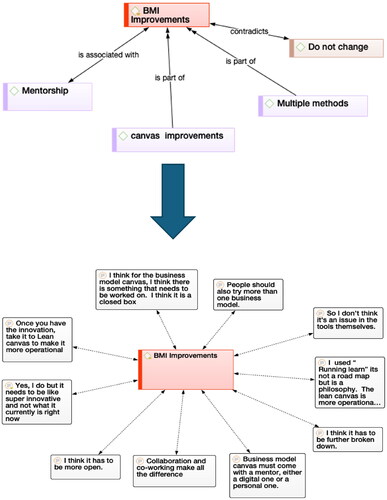

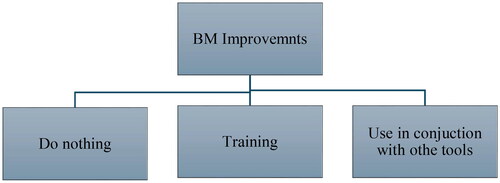

RQ 4: How can BM tools be improved?

Founder 1 criticized the current version of the BMC for being ‘too much of a closed box, it has to be more open’, while Founder 8 stated that ‘quantitative characteristics are needed’.

There is also a view that the BMC is fit-for-purpose, but the problem is the training around it, Founder 4:

I don’t think the tool is an issue in itself… sometimes it can be an issue how the tools are presented.

I used the Lean Canvas more as a philosophy than a roadmap, it’s more operational – but the BMC is the most important tool for innovation. Once you have the innovation, take it to the Lean Canvas to make it more operational.

4.9. Business model tools should not be improved

Our data reveal that some entrepreneurs argue in favor of not simplifying entrepreneurship. One explained how entrepreneurship is a mental sport, and as such, we should allow the ideas to organically develop, given the chaos and disorder can lead to imaginative innovation (Laberge Citation2009). This interpretation underscores how scholars can get carried away by the scientific aspects of entrepreneurship and overlook the creative aspects.

4.10. Training

Training emerged as a vital part for the effective use of the BMC. A theoretical delivery is not as inspiring to entrepreneurs as would be if it were taught by mentors or people who themselves had built a business before and thus know how to apply these tools in real life. Moreover, a lack of education on BM tools means that some entrepreneurs will never learn about tools that can facilitate entrepreneurial activities for them. Although it is outside the scope of this study to comment on if the use of BM tools resulted in greater success for the entrepreneurs who used them, it can be argued that an entrepreneur should take the initiative to learn about these tools, since studies confirm that they can be used to improve overall results (Foss and Saebi Citation2018).

4.11. Using BMC in conjunction with other tools

Although some entrepreneurs found the BMC to be overwhelming, other entrepreneurs expressed a preference for using it in conjunction with other frameworks. Examples include deconstructing ideas into a set of untested hypotheses then speaking to customers, testing the hypotheses and iterating until they find a valid business model – as advocated by Blank (Citation2003).

Following Osterwalder and Pigneur (Citation2010), there are various levels of using the BMC; the first level is a hypothesis checklist where the entrepreneur must think of everything that is needed to support an idea or vision or product. At the second level, an entrepreneur must understand that there are connections between all the boxes; entrepreneurs need to complete the BMC one step at a time. Blank (Citation2003) believes that most entrepreneurs stay at the first level, relating to product-market fit. Thus, a savvy entrepreneur may outwit their competitors by leveraging other elements of the BMC. The third level involves a process of mapping out the BM of leading companies, which allows an entrepreneur to understand what other companies did, which was so powerful. As the BMC is traditionally a static document, operationalizing can make it more dynamic. At level four, an entrepreneur must evaluate a number of business models or business model hypotheses, which necessitates performing experiments to fail or succeed and using those insights as feedback.

Our findings reveal that start-ups tend to engage only selectively with business model tools in a reactive, special fashion rather than using these methodologies as systematic BM innovation frameworks. Entrepreneurs focus intensely on product development first before addressing broader business model components in response to specific triggers. This is likely to stem from founders prioritizing immediate pressures and quick returns over longer-term strategic concerns (Blank Citation2003), aligning with Sanchez and Ricart (Citation2010) arguments that academic tools often overlook entrepreneurial realities.

Our data also showcase start-ups’ emphasis on learning-by-doing over theoretical engagement. Entrepreneurs valued mentor-shared experiences over classroom exposure regarding BM tools, reflecting Baden-Fuller and Haefliger (Citation2013) view that scholarly models rarely provide adequate practical advice. The relative neglect of step-by-step implementation guidance again points to the literature-practice gap in translating complex BM frameworks into start-up-friendly processes (Zott and Amit Citation2017). However, once forced to utilize tools like the BMC, participants noted benefits in compartmentalizing BM components to enable holistic assessment, strategic iteration, and planning. This indicates the value in academic models when effectively adapted to start-up environments and adequately supported through applied learning. Our findings suggest that maintaining conceptual complexity while improving ease-of-use can further mediate rigor and relevance.

5. Management implications

Although the study set out to explore BM tools, especially BMC, that are currently used in start-ups, it was found that the BMC is used almost exclusively as a tool for creating business models. Thus, we recommend that the BMC be used as follows:

5.1. Step 1

Find the product-market fit for the product (while acknowledging that failure is very high). Our findings hinted that many entrepreneurs focus on product development in the early stages of their venture. This seems to be the default approach and popular among entrepreneurs from sciences and engineering backgrounds. An effective way to learn is by ensuring that failure happens quickly, as recommended by Ries (Citation2011) in his lean start-up methodology. Also, by deploying the Value Proposition Canvas to find the product-market fit, an entrepreneur may improve their chances of success.

5.2. Step 2

Entrepreneurs need to cover all the blocks of the BMC and anticipate further aspects that may be important to the business. This can be interpreted as a checklist of important factors and will result in a set of assumptions or hypotheses that the entrepreneur has to prove or validate.

5.3. Step 3

Once the assumptions have been created and understood by an entrepreneur, they can be communicated to the rest of the team, by ‘telling the business model as a story’ (Strategyzer Citation2020). Telling a story in this context means that an entrepreneur avoids explaining the entire business model, and instead walks the audience through the business model one block at a time.

5.4. Step 4

Here, the entrepreneur must try to take inspiration from other business model ideas that have been outstanding in the past, in line with Gassmann, Frankenberger, and Michaela (Citation2014) who advocate recombining the core business model patterns that have transformed many industries before. The aim is to come up with ideas for a new business model in a way that will be disruptive to incumbents.

5.5. Step 5

To test one business model at a time and learn from customers, Blank (Citation2003) advises the entrepreneur to ‘get out of the building’ and iterate until a working business model is validated.

This research offers practical recommendations for enhancing the use of BM tools to support start-ups innovation efforts. Our findings both validate and build on prior studies acknowledging misalignment between scholarly BM research and entrepreneurial realities. For example, founders’ emphasis on learning-by-doing aligns with Baden-Fuller and Haefliger (Citation2013) who argue that academic models fail to provide adequate practical prescriptions. Yet, participants still noted benefits in classification when forced to use Business Models, which highlights the relevance of rigorous tools if effectively adapted to entrepreneurial contexts.

Furthermore, whereas Sanchez and Ricart (Citation2010) critique conflicting BM conceptualizations for causing confusion in practice, our data reveal that engagement also stemming from entrepreneurial tendencies prioritizing immediate pressures over strategic concerns (Blank Citation2003). This suggests a need to better tools to startup mentalities in addition to resolving ideological misalignments. Finally, the shortage of tailored perspective and disproportionate focus on static components noted by Budler, Župič, and Trkman (Citation2021) manifests in our findings through entrepreneurs’ emphasis on product development over holistic business model construction.

However, BM compartmentalization capability indicates the potential for injecting greater dynamism into academic tools. Thus, while validating identified gaps, our start-up-centered perspective offers novel insights into directions for compromising, including simplifying complex methodologies without losing rigor and better accommodating entrepreneurial cognitive frames. The recommendations ultimately form practical guidance for enhancing models’ functionality in dynamic startup contexts, delivering on promised applied contribution.

6. Discussion

The findings of this study provide valuable insights into the use of BM tools by start-ups, shedding light on the misalignment between academic literature and business practice. The results disclose two key phenomena: Reactive Iteration and Adaptive Training, which have significant implications for understanding how start-ups engage with BM tools and how these tools can be optimized for the unique needs of entrepreneurs.

The phenomenon of Reactive Iteration suggests that start-ups tend to engage with BM tools selectively and in response to specific triggers, rather than as a continuous, systematic process. This finding aligns with prior research highlighting the informal and decentralized decision-making in start-ups (Blank and Dorf Citation2020). However, our study extends this understanding by entrepreneurs often priorities product development over holistic business model design, only engaging with BM tools when they experience particular challenges or external pressures. This insight contributes to the ongoing debate about the optimal BM framework (Gassmann, Frankenberger, and Michaela Citation2014), suggesting that a one-size-fits-all approach may not be suitable for start-ups and that BM tools should be adaptable to the dynamic realities of entrepreneurship.

The second phenomenon, Adaptive Training, highlights the importance of practical, mentor-led learning in facilitating the effective use of BM tools by start-ups. This finding agrees with previous studies emphasizing the role of experiential learning in entrepreneurship education (Foss and Saebi Citation2018). However, our research goes further by demonstrating that entrepreneurs value contextualized, real-world insights over theoretical classroom knowledge when it comes to BM tools. This finding underscores the need for BM education to bridge the theory-practice gap (Baden-Fuller and Haefliger Citation2013) by incorporating more applied, problem-based learning approaches.

The study also highlights inconsistencies in start-ups’ understanding and application of BM tools, stemming from their trend to focus intensely on product development before addressing broader business model components. This finding agrees Blank’s (Citation2003) claim that start-ups often priorities product-market fit over long-term strategic concerns. However, our research suggests that this inconsistent engagement with BM tools may hinder start-ups’ ability to create sustainable, scalable businesses. This insight contributes to the growing body of literature on the challenges faced by start-ups (Paradkar, Knight, and Hansen Citation2015) and highlights the importance of promoting a more holistic approach to BM design in entrepreneurial education (Kumar et al. Citation2021) and support programs.

7. Limitations and future research

This exploratory study has limitations related to its contextual focus and modest sample size, impacting external validity. Future empirical work with a larger start-up sample is recommended for investigating whether the use of BM tools for BMI correlates with improved start-up success rates. The semi-structured interviews with open-ended questions added depth but challenged replicability. Acknowledging these constraints, the study paves the way for further research, yet nevertheless contributes to scientific discourse on BM tools and BMI.

It would be constructive for future studies to formulate hypotheses to explore causal relationships between BM tool usage and startup success, how to optimize existing BM tools for enhanced utility, and redefine business models and BMI, thus establishing a solid foundation for subsequent research on BM tool effectiveness in fostering start-up success.

8. Conclusion

This study contributes to the existing literature by emphasizing the need to understand practical usage patterns of BM tools among entrepreneurs in start-ups. The findings diverge from widely-held assumptions, revealing that entrepreneurs tend to default to working on specific aspects, particularly the value proposition block, only methodically engaging with their business model when triggered by specific needs or external requirements. Unlike the common perception of BM tools as ongoing guides for BMI, our study contends that entrepreneurs often treat BMI as a dynamic and iterative process rather than a continuous, structured exercise.

Our study also highlights the tension between the criticality of BM tools and the time-consuming nature of their application, reinforcing the notion that entrepreneurs, while comfortable managing daily business demands, may neglect the long-term sustainability and profitability aspects that effective BM utilization could enhance. The recommendation to focus predominantly on the value proposition and customer segment blocks, especially in the ideation phase, challenges conventional beliefs and provides pragmatic guidance for start-ups in their early stages. Clearly, more research on start-ups is needed in order to keep pace with the ongoing evolution in business model design.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jessica Lichy

Jessica Lichy has an MBA, PhD and post-doctoral degree (HDR) in online/digital consumer behaviour, focusing on sociomaterial and sociotechnical segmentation of user behaviour. Passionate for digital, she is employed as a full professor at IDRAC Business School (France). She is Visiting Professor at University of Sunderland Faculty of Business, Law and Tourism, and works at international partner universities as a research-active guest lecturer. Her research interests include Big Data and digital transformation from an end-user perspective. Research-in-progress includes tracing and explaining emerging trends in technology-enhanced living. Jessica guest edits special issues for ranked journals, organises research conference with international partner institutions, and actively develops a number of collaborative academic projects and teaching exchanges.

Yuan Zhai

Yuan Zhai holds a PhD in Business Management, with a focus on applying emerging technologies for sustainable and inclusive growth in underserved communities. As an engaged scholar, he conducts interdisciplinary research exploring strategies for organizations to leverage innovations like AI to create shared value in emerging markets. Yuan actively disseminates his findings through academic publications and practitioner-oriented channels. He guest edits special journal issues, organizes conferences, and develops collaborative projects that bridge research and practice. Yuan is dedicated to capacity building and co-creation initiatives that empower local universities, entrepreneurs, and youth to lead locally-sustained development.

William Ang’awa

William Ang’awa as a Senior Lecturer, he specializes in marketing and enterprise with a passion for student-centered and impact-driven learning. William’s teaching fosters innovation and ethics through close collaboration with students and colleagues. His research examines embedding entrepreneurship across the curriculum. William serves on the University’s highest academic authority, overseeing standards and strategy. One of William’s greatest honors was being named ‘Most Student Oriented Lecturer’ for his commitment to co-creating ideas with learners. He aims to apply his scholarly and student-focused approach to inform best practices at the intersection of education and enterprise.

References

- Academy of Management. 2021. AoM Code of Ethics. Accessed 4 June 2023. https://aom.org/about-aom/governance/ethics/code-of-ethics

- Aziz, N., B. Friedman, A. Bopieva, and I. Kelesd. 2013. “Entrepreneurial Motives and Perceived Problems: An Empirical Study of Entrepreneurs in Kyrgyzstan.” International Journal of Business 18 (2): 163.

- Baden-Fuller, C., and S. Haefliger. 2013. “Business Models and Technological Innovation.” Long Range Planning 46 (6): 419–426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2013.08.023

- Bachmann, N., and H. Jodlbauer. 2023. “Iterative Business Model Innovation: A Conceptual Process Model and Tools for Incumbents.” Journal of Business Research 168: 114177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2023.114177

- Bocken, N., and Y. Snihur. 2020. “Lean Startup and the Business Model: Experimenting for Novelty and Impact.” Long Range Planning 53 (4): 101953. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2019.101953

- Blank, S. 2003. The Four Steps to the Epiphany: Successful Strategies for Products That Win. Delaware: Lule Enterprises Incorporated.

- Blank, S., and B. Dorf. 2020. The Startup Owner’s Manual: The Step-By-Step Guide for Building a Great Company. New Jersey, US: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- Bryman, Alan. 2016. Social Research Methods. 5th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Buchalcevová, A., and T. Mysliveček. 2016. “Lean Startup and Lean Canvas Using for Innovative Product Development.” Acta Informatica Pragensia 5 (1): 18–33. https://doi.org/10.18267/j.aip.82

- Budler, M., I. Župič, and P. Trkman. 2021. “The Development of Business Model Research: A Bibliometric Review.” Journal of Business Research 135: 480–495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.06.045

- Caputo, A., S. Pizzi, M. M. Pellegrini, and M. Dabić. 2021. “Digitalization and Business Models: Where Are we Going? A Science Map of the Field.” Journal of Business Research 123: 489–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.09.053

- Casadesus-Masanell, R., and J.-E. Ricart. 2010. “From Strategy to Business Model and onto Tactics.” Long Range Planning 43 (2-3): 195–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2010.01.004

- Chesbrough, H. 2010. “Business Model Innovation: Opportunities and Barriers.” Long Range Planning 43 (2-3): 354–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2009.07.010

- Climent, R. C., and D. M. Haftor. 2021. “Value Creation through the Evolution of Business Model Themes.” Journal of Business Research 122: 353–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.09.007

- Comberg, C., F. Seith, A. German, and V. Velamuri. 2014. “Pivots in Startups: Factors Influencing Business Model Innovation in Startups.” In ISPIM Conference Proceedings (pp. 1–19). The International Society for Professional Innovation Management.

- Corral de Zubielqui, G., and J. Jones. 2020. “How and When Social Media Affects Innovation in Start-Ups. A Moderated Mediation Model.” Industrial Marketing Management 85: 209–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2019.11.006

- de Faria, V. F., V. P. Santos, and F. H. Zaidan. 2021. “The Business Model Innovation and Lean Startup Process Supporting Startup Sustainability.” Procedia Computer Science 181: 93–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2021.01.106

- Dey, I. 1999. Grounding Grounded Theory. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- Do Vale, G., I. Collin-Lachaud, and X. Lecocq. 2021. “Micro-Level Practices of Bricolage during Business Model Innovation Process: The Case of Digital Transformation towards Omni-Channel Retailing.” Scandinavian Journal of Management 37 (2): 101154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scaman.2021.101154

- Elliott, V. 2018. “Thinking about the Coding Process in Qualitative Data Analysis.” Qualitative Report 23 (11): 2850–2861.

- Farquhar, J. 2012. Case Study Research for Business. London: Sage.

- Farquhar, J., J. Lichy, D. Althalathini, M. Kachour, and N. Michels. 2024. “Co-Creating Value in Entrepreneurship: An Exploratory Study of Lebanese Women.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2024.2311319

- Foss, N. J., and T. Saebi. 2018. “Business Models and Business Model Innovation: Between Wicked and Paradigmatic Problems.” Long Range Planning 51 (1): 9–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2017.07.006

- Frankenberger, K., T. Weiblen, M. Csik, and O. Gassmann. 2013. “The 4I-Framework of Business Model Innovation: A Structured View on Process Phases and Challenges.” International Journal of Product Development 18 (3/4): 249–273. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJPD.2013.055012

- Garidis, K., and A. Rossmann. 2019. “A Framework for Cooperation Behavior of Start-Ups: Developing a Multi-Item Scale and Its Performance Impacts.” Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 26 (6/7): 877–890. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-04-2019-0125

- Gassmann, O., K. Frankenberger, and C. Michaela. 2014. The Business Model Navigator. Pearson Education: Harlow.

- George, G., and A. J. Bock. 2011. “The Business Model in Practice and Its Implications for Entrepreneurship Research.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 35 (1): 83–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00424.x

- Griva, A., D. Kotsopoulos, A. Karagiannaki, and E. D. Zamani. 2023. “What Do Growing Early-Stage Digital Start-Ups Look like? A Mixed-Methods Approach.” International Journal of Information Management 69: 102427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2021.102427

- Haase, A., and P. Eberl. 2019. “The Challenges of Routinizing for Building Resilient Startups.” Journal of Small Business Management 57 (sup 2): 579–597. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12511

- Hennink, M., and B. N. Kaiser. 2021. “Sample Sizes for Saturation in Qualitative Research: A Systematic Review of Empirical Tests.” Social Science & Medicine 292: 114523. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114523

- Ingstrup, M. B., L. Aarikka-Stenroos, and N. Adlin. 2021. “When Institutional Logics Meet: Alignment and Misalignment in Collaboration between Academia and Practitioners.” Industrial Marketing Management 92: 267–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2020.01.004

- Jin, B., and D. Shin. 2020. “Changing the Game to Compete: Innovations in the Fashion Retail Industry from the Disruptive Business Model.” Business Horizons 63 (3): 301–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2020.01.004

- Jochem, R., M. Menrath, and K. Landgraf. 2010. “Implementing a Quality‐Based Performance Measurement System: A Case Study Approach.” The TQM Journal 22 (4): 410–422. https://doi.org/10.1108/17542731011053334

- Johnson, M. W., and A. G. Lafley. 2010. Seizing the White Space: Business Model Innovation for Growth and Renewal. Boston: Harvard Business Press.

- Joseph, G., N.Aboobaker, and A. Z. Zakkariya. 2023. “Entrepreneurial Cognition and Premature Scaling of Startups: A Qualitative Analysis of Determinants of Start-up Failures.” Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies 15 (1): 96–112. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEEE-11-2020-0412

- Katila, R., E. L. Chen, and H. Piezunka. 2012. “All the Right Moves: How Entrepreneurial Firms Compete Effectively.” Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 6 (2): 116–132. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1130

- King, N., C. Horrocks, and J. Brooks. 2018. Interviews in Qualitative Research, 360. London, Sage.

- Kumar, S., J. Vanevenhoven, E. Liguori, L. P. Dana, and N. Pandey. 2021. “Twenty-Five Years of the Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development: A Bibliometric Review.” Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 28 (3): 429–455. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-12-2020-0443

- Laberge, P. Y. 2009. “Edgar Morin, Mon Chemin: Entretiens Avec Djenane Kareh Tager.” Canadian Journal of Sociology 34 (1): 184–187. https://doi.org/10.29173/cjs6098

- LEGO® Learning Institute. 2009. “Defining Systematic Creativity.” Accessed January 13, 2022. https://davidgauntlett.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/LEGO_LLI09_Systematic_Creativity_PUBLIC.pdf

- Gioia, D., and K. Chittipeddi. 1991. “Sensemaking and Sensegiving in Strategic Change Initiation.” Strategic Management Journal 12 (6): 433–448. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250120604

- Gioia, D. A., K. G. Corley, and A. L. Hamilton. 2013. “Seeking Qualitative Rigor in Inductive Research: Notes on the Gioia Methodology.” Organizational Research Methods 16 (1): 15–31.

- Magnani, G., and D. Gioia. 2023. “Using the Gioia Methodology in International Business and Entrepreneurship Research.” International Business Review 32 (2): 102097. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2022.102097

- Maurya, A. 2012. “Why Lean Canvas vs. Business Model Canvas.” Accessed March 28, 2023. https://blog.leanstack.com/why-lean-canvas-vs-business-model-canvas/

- Magretta, J. 2002. “Why Business Models Matter.” Harvard Business Review 80 (5): 86–92.

- McFarlane, D. 2017. “Osterwalder’s Business Model Canvas: Its Genesis, Features, Comparison, Benefits and Limitations.” Westcliff International Journal of Applied Research 1 (2): 24–27. https://doi.org/10.47670/wuwijar201712DAMC

- McGrath, R. G. 2013. The End of Competitive Advantage: How to Keep Your Strategy Moving as Fast as Your Business. Harvard Business Review Press.

- Miller, K., M. McAdam, P. Spieth, and M. Brady. 2021. “Business Models Big and Small: Review of Conceptualisations and Constructs and Future Directions for SME Business Model Research.” Journal of Business Research 131: 619–626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.12.036

- Morris, M., M. Schindehutte, and J. Allen. 2005. “The Entrepreneur’s Business Model: Toward a Unified Perspective.” Journal of Business Research 58 (6): 726–735. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2003.11.001

- Örnek, A. S., and Y. Danyal. 2015. “Increased Importance of Entrepreneurship from Entrepreneurship to Techno-Entrepreneurship (Startup): Provided Supports and Conveniences to Techno-Entrepreneurs in Turkey.” Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences 195: 1146–1155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.06.164

- Osterwalder, A., and Y. Pigneur. 2010. Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers. Vol. 1. New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons.

- Paradkar, A., J. Knight, and P. Hansen. 2015. “Innovation in Start-Ups: Ideas Filling the Void or Ideas Devoid of Resources and Capabilities?” Technovation 41–42: 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2015.03.004

- Payne, A., P. Frow, L. Steinhoff, and A. Eggert. 2020. “Toward a Comprehensive Framework of Value Proposition Development: From Strategy to Implementation.” Industrial Marketing Management 87: 244–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2020.02.015

- Pietilä, A. M., S. M. Nurmi, A. Halkoaho, and H. Kyngäs. 2020. “Qualitative Research: Ethical Considerations.” In The Application of Content Analysis in Nursing Science Research (pp. 49–69). Cham: Springer.

- Ratten, V., E. St-Jean, M. Brännback, A. Carsrud, S. Kiridena, and I. Akpan. 2023. “How to Write a Good Entrepreneurship and Small Business Article.” Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship 35 (5): 659–670. https://doi.org/10.1080/08276331.2022.2059983

- Ries, E. 2011. The Lean Startup. New York, NY: Crown Business.

- Röhl, K.-H. 2019. “Entrepreneurship: A Comparative Study of the Interplay of Culture and Personality from a Regional Perspective.” Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship 31 (2): 119–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/08276331.2018.1462621

- Salamzadeh, Y., T. Sangosanya, A. Salamzadeh, and V. Braga. 2022. “Entrepreneurial Universities and Social Capital: The Moderating Role of Entrepreneurial Intention in the Malaysian Context.” The International Journal of Management Education 20 (1): 100609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2022.100609

- Sanchez, P., and J. E. Ricart. 2010. “Business Model Innovation and Sources of Value Creation in Low‐Income Markets.” European Management Review 7 (3): 138–154. https://doi.org/10.1057/emr.2010.16

- Schmitt, A., K. Rosing, S. X. Zhang, and M. Leatherbee. 2018. “A Dynamic Model of Entrepreneurial Uncertainty and Business Opportunity Identification: Exploration as a Mediator and Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy as a Moderator.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 42 (6): 835–859. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258717721482

- Skog, D., H. Wimelius, and J. Sandberg. 2018. “Digital Disruption.” Business & Information Systems Engineering 60 (5): 431–437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12599-018-0550-4

- Slávik, Š. 2019. “The Business Model of Start-up—Structure and Consequences.” Administrative Sciences 9 (3): 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci9030069

- Schmidt, A. L., and P. van der Sijde. 2022. “Disruption by Design? Classification Framework for the Archetypes of Disruptive Business Models.” R&D Management 52 (5): 893–929. https://doi.org/10.1111/radm.12530

- Schwarz, J., and C. Legner. 2020. “Business Model Tools at the Boundary: Exploring Communities of Practice and Knowledge Boundaries in Business Model Innovation.” Electronic Markets 30 (3): 421–445. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-019-00379-2

- Shirokova, G., O. Osiyevskyy, and K. Bogatyreva. 2016. “Exploring the Intention–Behavior Link in Student Entrepreneurship: Moderating Effects of Individual and Environmental Characteristics.” European Management Journal 34 (4): 386–399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2015.12.007

- Strategyzer. 2020. “Build an Invincible Company.” Accessed January 12, 2022. https://strategyzer.com

- Suntornpithug, N., and P. Suntornpithug. 2008. “Don’t Give Them the Fish, Show Them How to Fish: Framework of Market-Driven Entrepreneurship in Thailand.” Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship 21 (2): 181–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/08276331.2008.10593421

- Teece, D. J. 2010. “Business Models, Business Strategy and Innovation.” Long Range Planning 43 (2-3): 172–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2009.07.003

- Trimi, S., and J. Berbegal-Mirabent. 2012. “Business Model Innovation in Entrepreneurship.” International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 8 (4): 449–465. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-012-0234-3

- Urquhart, C., and W. Fernández. 2013. “Using Grounded Theory Method in Information Systems: The Researcher as Blank Slate and Other Myths.” Journal of Information Technology 28 (3): 224–236. https://doi.org/10.1057/jit.2012.34

- Velu, C., and A. Jacob. 2016. “Business Model Innovation and Owner–Managers: The Moderating Role of Competition.” R&D Management 46 (3): 451–463. https://doi.org/10.1111/radm.12095

- Yin, R. K. 2012. Applications of Case Study Research. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Yu, C., Z. Zhang, and Y. Liu. 2019. “Understanding New Ventures’ Business Model Design in the Digital Era: An Empirical Study in China.” Computers in Human Behavior 95: 238–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.01.027

- Zamani, E. D., A. Griva, K. Spanaki, P. O'Raghallaigh, and D. Sammon. 2021. “Making Sense of Business Analytics in Project Typical and Prioritisation: Insights from the Start-up Trenches.” Information Technology & People 37 (2): 895–918. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-09-2020-0633

- Zikmund, W. G. 2003. Business Research Methods. London: Thomson/South-Western.

- Zott, C., and R. Amit. 2007. “Business Model Design and the Performance of Entrepreneurial Firms.” Organization Science 18 (2): 181–199. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1060.0232

- Zott, C., and R. Amit. 2008. “The Fit between Product Market Strategy and Business Model: Implications for Firm Performance.” Strategic Management Journal 29 (1): 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.642

- Zott, C., R. Amit, and L. Massa. 2011. “The Business Model: Recent Developments and Future Research.” Journal of Management 37 (4): 1019–1042. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311406265

- Zott, C., and R. Amit. 2017. “Business Model Innovation: How to Create Value in a Digital World.” NIM Marketing Intelligence Review 9 (1): 18–23. https://doi.org/10.1515/gfkmir-2017-0003

Appendix A:

Overview of 6 business model tools

Business Model Canvas (BMC)