ABSTRACT

This study documents change over time and across proficiency levels in French second-language (L2) speakers’ practices for initiating complaints. Prior research has shown that speakers typically initiate complaints in a stepwise manner that indexes the contingent, moral, and delicate nature of the activity. Although elementary speakers in my data often launch complaint sequences in a straightforward way, they sometimes embodiedly foreshadow verbal expressions of negative stance or delay negative talk through brief positively valenced prefaces. More advanced speakers in part rely on the same initiation practices as elementary speakers. In addition, they recurrently use extensive prefatory work that accounts for and legitimizes the upcoming complaint, and they regularly initiate complaints jointly with coparticipants through a progressive escalation of negative stance expressions. I document interactional resources involved in this change and discuss the findings in terms of speakers’ development of L2 interactional competence. Data are in French with English translations.

Complaints about nonpresent third parties or states of affairs have been described as highly moral activities that are dependent on coparticipants’ collaboration for their emergence and development (Drew, Citation1998; Heinemann & Traverso, Citation2009). Speakers therefore tend to move into complaining in a stepwise manner, carefully testing the grounds for the complaint and displaying an orientation to the delicacy of criticizing others (Ruusuvuori et al., Citation2019). Although there is a growing body of conversation analytic (CA) research documenting how second-language (L2) speakers develop their interactional procedures for accomplishing social actions and activities in the L2 (e.g., Hellermann, Citation2008; Pekarek Doehler & Berger, Citation2018; Sert, Citation2019), how L2 speakers develop their practices for accomplishing third-party complaining-in-interaction has so far remained unexplored (but see Skogmyr Marian, Citation2020, for further results relating to the present study). As an attempt to fill this gap, this study focuses on one particular aspect of complaint activities, their initiation, and analyzes how elementary and upper-intermediate/advanced L2 speakers of French initiate complaints. I show that both of these groups of speakers have ways to attend to the moral and delicate nature of complaining in their initiations, although more advanced speakers deploy a more varied array of practices that allows them to enter into complaining in a stepwise manner in similar ways as first-language (L1) speakers. The documented change relates to both sequence organization and to the use of particular linguistic resources, as well as to the ability to co-construct complaints with others. These findings have implications for our understanding of the development of L2 interactional competence and of complaining-in-interaction.

The development of L2 interactional competence

The study is situated within the growing body of CA research that investigates L2 interactional competence and its longitudinal development (see Skogmyr Marian & Balaman, Citation2018, for an overview). The development of interactional competence may be understood as change over time in speakers’ systematic interactional procedures, or “methods” in ethnomethodological terms, for accomplishing recognizable social actions and activities in context-sensitive and recipient-designed ways (Pekarek Doehler & Berger, Citation2018). Empirical studies on the development of L2 interactional competence typically adopt a longitudinal research design, comparing L2 speakers’ interactional practices at different points in time. Others use a cross-sectional design, comparing practices of speakers at different proficiency levels—or combine the two frameworks (see Wagner et al., Citation2018). The many recent studies in this field have provided evidence about L2 speakers’ evolving methods for a range of social actions and activities.

While no developmental research has yet investigated complaining-in-interaction (except from Skogmyr Marian, Citation2020), research on speakers’ management of longer sequences of actions such as storytelling (Hellermann, Citation2008; Pekarek Doehler & Berger, Citation2018) and practices for accomplishing delicate actions like disagreements (Pekarek Doehler & Pochon-Berger, Citation2011) and requests (Al-Gahtani & Roever, Citation2012) are particularly relevant for the present study. So are studies on displays of active listenership and other types of recipient responses (Kunitz & Yeh, Citation2019; Sert, Citation2019). Such research shows that L2 speakers typically start out with a limited set of interactional procedures that diversify over time, allowing for increased context sensitivity and recipient design. In the case of storytelling, speakers progressively develop practices for accomplishing story prefaces that secure recipiency for a longer turn, provide necessary circumstantial information, and project the nature of the story so as to help coparticipants anticipate appropriate responses (Hellermann, Citation2008; Pekarek Doehler & Berger, Citation2018). As for disagreements and requests, more advanced L2 speakers deploy practices that index an orientation to the dispreferred nature of such actions. They produce disagreement turns in the yes-but format (Pekarek Doehler & Pochon-Berger, Citation2011) that often has been observed among L1 speakers (Pomerantz, Citation1984), and they better prepare the grounds for requests through preliminary moves (Al-Gahtani & Roever, Citation2012). Studies on L2 speakers’ practices for displaying active listenership and providing relevant recipient responses (Kunitz & Yeh, Citation2019; Sert, Citation2019) show that L2 speakers increasingly synchronize their turns and actions with others to sustain ordinary turn-taking, for instance through active listenership signals and collaborative turn completions.

Also relevant for this study is the growing literature on speakers’ development of an “L2 grammar-for-interaction” (Pekarek Doehler, Citation2018), which focuses on the role of linguistic resources for action formation and interaction organization. This research indicates that the development of L2 interactional competence does not only involve the use of an increasingly diverse linguistic repertoire over time but also a growing capacity to apply existing resources in context-sensitive and locally efficacious ways (for an overview, see Pekarek Doehler, Citation2018; see also Pekarek Doehler & Balaman, Citationthis issue).

Complaining-in-interaction

The study investigates complaints about nonpresent third parties or states of affairs (e.g., Drew, Citation1998; Drew & Holt, Citation1988; Traverso, Citation2009), so-called indirect complaints. Studies on complaining in different languages (e.g., English, French, German, Danish, Finnish) have identified common characteristics of indirect complaints. In indirect complaints, speakers express negative stance toward a particular complainable (the object of the complaint) so as to recruit affiliation or sympathy from their coparticipants (Drew, Citation1998; Drew & Holt, Citation1988). Negative stance displays are sometimes subtle (Ruusuvuori et al., Citation2019) but may also include strong expressions of frustration or indignation, for example through extreme-case formulations (Pomerantz, Citation1986) and affect-laden prosody (Selting, Citation2012). Complaints are both moral and delicate in nature, as the complainant makes explicit how the object of the complaint breaches normative expectations of morality (what is fair, just, reasonable, etc.; Drew, Citation1998) and offers negative assessments the fairness of which is to be judged by coparticipants (Ruusuvuori et al., Citation2019). Complaints should be considered interactional activities rather than actions, as they typically stretch over more than one adjacency pair (Heinemann & Traverso, Citation2009). Their emergence is therefore contingent on coparticipants’ readiness to participate as complaint recipients or co-complainants (see Drew & Walker, Citation2009, for joint complaints). Because of these characteristics, speakers deploy particular means for introducing complaints in ways that index the contingent, moral, and delicate nature of the activity (Heinemann & Traverso, Citation2009; Ruusuvuori et al., Citation2019).

Incipient complainants tend to move into complaining in a stepwise manner that allows them to test the grounds for the complaint before launching the activity fully (Heinemann & Traverso, Citation2009; Ruusuvuori et al., Citation2019; Traverso, Citation2009). Specifically in institutional settings, speakers’ orientations to complaining as a delicate activity are observable in careful and often mitigated initiations (Ruusuvuori et al., Citation2019). In non-institutional interactions too, however, overt criticism and other strong expressions of negative stance tend to come only after more subtle hints (Pomerantz, Citation1986; Schegloff, Citation2005). Speakers may also do some “subject-side” (pertaining to themselves) prefatory work to convey their own reasonableness and that they are legitimate complainants (Edwards, Citation2005). Speakers’ orientation to complaints as moral and delicate activities hence often manifests in the initiation phase in both the delay and mitigation of criticism of others and through speakers’ positive self-portrayal. As shown by Ruusuvuori et al. (Citation2019), coparticipants may also facilitate complaint initiations. The result is a collaborative stepwise transition into the complaint, with a progressive escalation of negative stance expressions.

Method and data

The study uses comparative CA to investigate change in L2 interactional practices over time and across proficiency levels (see Wagner et al., Citation2018). Adopting a multimodal perspective, the study draws on a corpus of 80 hours of video recordings of small groups of university students participating in an L2 French “conversation circle” in the French-speaking part of Switzerland. All participants gave informed consent to participate in the research and permission for use of the data for scientific purposes, including publication. Names, images, and other identifying information have been anonymized. The participants were foreign students who met regularly over 6–12 months to practice ordinary conversation in an informal setting. They ranged from elementary to advanced speakers of French (A1–C1 levels on the CEFR scale, see Council of Europe, Citation2020), as estimated based on an independent proficiency measure and/or course level, and they interacted with two to three other L2 speakers at similar proficiency levels. The analysis focuses on interactions involving five focal participants: Suresh, Mariana, Malia, Aurelia, and Cassandra (all pseudonyms). These participants were chosen as they represent two main starting proficiency levels, elementary (A1–A2) and upper-intermediate/advanced (B2–C1), allowing for a comparison of the complaint initiations of speakers at distinctly different proficiency levels. Because two of the participants who were initially elementary speakers eventually reached the upper-intermediate/advanced level, the analysis incorporates a longitudinal dimension, comparing these speakers’ practices over time. Comparability is enhanced by the fact that the speech exchange system (small-group informal conversation), the (type of) participants (L2 peers), and the activity type (indirect complaining) are kept constant over time and participants (cf. Wagner et al., Citation2018).

A total of 68 complaints were included in the analysis (). The collection of complaints with the four elementary speakers (Suresh, Mariana, Aurelia, Malia) includes 32 sequences. The collection with upper-intermediate/advanced speakers (Aurelia, Malia, Cassandra) includes 36 sequences (Suresh and Mariana never reach upper-intermediate/advanced levels, and Cassandra is already at B2 level at the beginning of her participation in the recordings). The comparison thus encompasses a longitudinal analysis of Aurelia and Malia’s interactional practices at the beginning and end of their participation in the research (see gray cells in ).

Table 1. Number of complaint sequences per speaker and proficiency level. Months in parentheses refer to the months of the speakers’ participation included as base for the collection

The collections were established based on the characteristics of complaints presented in the previous literature review. I only included sequences in which the focal participants partake as main complainant(s). Distinctive for these data is that many complaints concern inanimate matters, such as Swiss society and the difficulty of learning French. The recurrence of these complainables reflects the interactional setting at hand, as the participants met in their roles as L2-speaking foreigners and often discussed their shared difficulties. Although some of these sequences initially resemble troubles talk (see Jefferson, Citation1988), they develop into complaints as speakers invoke issues of unfairness or unreasonableness and display their affect-laden frustration or indignation. The inanimate nature of many complainables and the participant framework (peers) possibly make such complaints less delicate matters than complaints about third parties in more formal settings. Interestingly, however, the documented change over time in speakers’ initiation practices is observed for both animate and inanimate complainables, which indicates the relevancy of initiating complaints in a more stepwise manner also in “safe” interactional contexts in which affiliative responses can be expected.

Analysis

Results show differences over time in the interactional work speakers accomplish as they move into complaining. The analysis demonstrates speakers’ increasing capacity to initiate complaints in a stepwise manner that indexes a sensitivity to the contingent, moral, and delicate nature of the activity. Starting with elementary speakers’ initiation practices, I then move on to upper-intermediate/advanced speakers. Because of the lengthy nature of most complaint sequences, I only show their beginning.

Elementary speakers

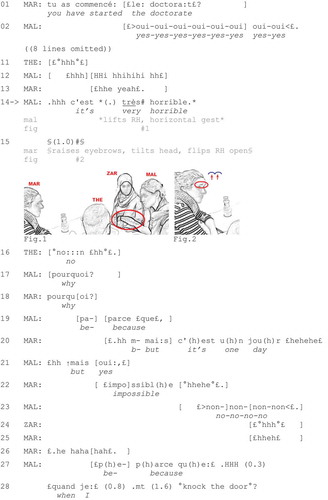

Elementary speakers regularly initiate complaint sequences through (high-grade) negative stance expressions that clearly convey the nature of the upcoming talk without showing any orientation to delicacy. Excerpt 1Footnote1 illustrates such initiation. Mariana asks Malia whether she has started her doctorate studies, as announced earlier (line 1). Malia’s repeated oui (“yes”) in fast succession and her smiley voice (line 2) foreshadow something newsworthy about the situation, without giving any indications about the upcoming complaint. In a side-sequence (lines omitted), Malia jokingly blames Mariana, who arrived late to the conversation, for having missed Malia’s first report about the start of her doctorate. She thereafter offers a high-grade negative assessment (line 14) that works as a steppingstone into a complaint about her first day as a PhD student.

Ex. 1 (Mer1_2016-11-02_33:18_commencé_travail_b)

Through prosodic stress on the intensifier très (“very”), the hyperbolic assessment adjective horrible (“horrible”), and a horizontal hand gesture (), Malia assesses the start of her doctorate as a highly negative experience (line 14). Mariana receipts this high-grade assessment with an embodied display of astonishment, seen in her raised eyebrows, tilted head, and hand flipped open palm up (line 15, ), while Theo, who has already heard about the situation, objects to Malia’s characterization of it (line 16). Malia’s own and Mariana’s pourquoi (“why,” lines 17–18) show their normative expectation of justification of negative assessments (Lerner, Citation1996). Malia attempts to initiate an account in line 19, but she is interrupted by Mariana’s objections to Malia’s portrayal of her first day (lines 20, 22). Only after some further insistence (line 23) does Malia pursue her account by telling about her troublesome first day (lines 27–28 and onward).

This sequence demonstrates elementary speakers’ recurrent use of high-grade negative assessments to launch complaint sequences. Such assessments clearly frame the upcoming talk as negatively valenced, without showing any orientation to delicacy. In this excerpt, Malia’s high-grade assessment led to objections that interrupted the sequence progression. In other cases, similar straightforward initiations are however treated as unproblematic by coparticipants (see Discussion).

Sometimes, elementary speakers nevertheless display an orientation to the delicate nature of complaining in their initiations. One way they do this is by first conveying negative stance embodiedly during silence or non-lexical vocalizations. Such stance expressions project the negative valence of the upcoming talk (cf. Ruusuvuori & Peräkylä, Citation2009) without including any immediate verbalization of criticism or negative stance. In my data, they often lead coparticipants to facilitate entry into complaining (Ruusuvuori et al., Citation2019) through cooperative responses. In Ex. 2, Malia invites Mariana to give a status update about herself (line 1). In response, Mariana first offers bodily-visual expressions of negative stance before initiating a complaint about her tiresome visit at the bank (see line 10).

Ex. 2 (Mer1_2016-11-02_21:04_la_banque)

In response to Malia’s question, Mariana closes her eyes (line 2, ) and starts leaning forward and lowering her head (line 3, ), thereby visibly delaying a verbal answer. Zarah’s laughter (line 3) displays the early recognizability of Mariana’s embodied conduct as indicating trouble. Malia’s loud £↑HI↑HI↑HE::H£ (line 4), which expresses a stylized laughter and possibly a sigh (cf. Haakana, Citation2012, on “fake” laughter; Hoey, Citation2014, on sighing in interaction), and the prosodically marked fatigu↑ée (“tired,” line 7), work as a mocking imitation of a response on Mariana’s behalf, showing Malia’s interpretation of Mariana’s embodied conduct as indicating tiredness and eliciting a confirmation from Mariana. Indeed, Mariana confirms this interpretation (line 8) and upgrades the assessment before expanding with an account: She went to the bank (line 10). As seen in Theo and Malia’s non-lexical assessments in lines 13–14, the coparticipants treat Mariana’s self-assessment and account as delivering bad news, and Malia elicits an elaboration by asking whether it was in French (line 18), thereby again facilitating the development of the sequence (Ruusuvuori et al., Citation2019). Mariana confirms Malia’s assumption and expands the sequence by telling about her tiresome experience (not shown). In this excerpt, Mariana’s bodily-visual display of trouble in response to her coparticipant’s open-ended status update inquiry foreshadows negatively valenced talk (cf. Ruusuvuori & Peräkylä, Citation2009, on facial expressions foreshadowing verbal assessments in the context of tellings). The coparticipants’ responses to this stance display afford an opportunity for Mariana to expand on her troubles, thereby assisting with the advancement of the sequence.

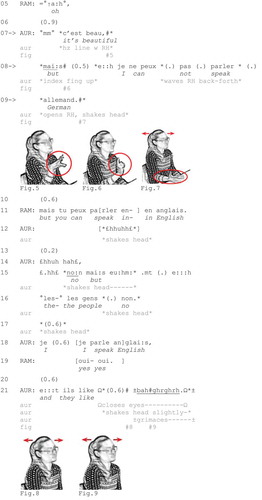

Another way elementary speakers orient to the delicacy involved in verbalizing negative stance is by using contrastive prefaces of positive valence of the type “praise-but”-initiations described by Sacks (Citation1992, Vol. I, p. 359). While delaying talk of negative valence, such prefaces also contribute, at least minimally, to portraying a more nuanced picture of the speaker as someone who does more than just complain. They also enhance the recognizability of whatever follows as something negative regardless of its linguistic formatting, thereby contributing to action formation. Excerpt 3 offers a first example. Here Aurelia will initiate a complaint about the difficulty of communicating with people in Zürich due to their unwillingness to speak English (see line 21). The sequence starts with a circumstantial story preface in which Aurelia announces that she went to Zürich last weekend (lines 1–2, 4). The turn of main interest comes in line 7, after Rameh’s receipts of the story preface (lines 3, 5).

Ex. 3 (Lun_2017-03-13_06:50_communication_impossible)

In line 7, Aurelia positively assesses Zürich with c’est beau (“it’s beautiful”). Her horizontal hand gesture () adds some emphasis to this assessment (Kendon, Citation2004). She then produces the slightly elongated and stressed contrastive conjunction mai:s (“but”) as she turns her right hand index finger upward (), thereby projecting a strong contrast with her positive assessment of Zürich to follow. What follows is not a negative object-assessment (pertaining to Zürich), however. Instead Aurelia asserts her inability to speak German (lines 8–9). Having waved her right hand back and forth in front of her, at the end of her turn she opens her hand up, palm upward and fingers spread () to index her helplessness in the situation (Kendon, Citation2004). Rameh’s interpretation of Aurelia’s turn as expressing a potential complaint is observable in his objection in line 11: While not accepting Aurelia’s assertion about her inability to speak German as a legitimate problem, it treats Aurelia’s assertion as the expression of a problem. In response, Aurelia reenacts how unhelpful and unreasonable people were when she tried to speak English with them (lines 15–16, 18, 21; ), thereby respecifying her problem in terms of a transgression by others. Only after this other-criticism does Rameh show his affiliation with Aurelia (lines 23–24), and Aurelia produces several high-grade negative assessments of her communication with the Zürichois (line 25 and onward). Aurelia’s positive assessment of the city and the contrastive conjunction thus delay and help frame the subsequent assertion about herself as a problem. The use of these resources (contrastive preface + negative self-portrayal) before other-criticism reveals some sensitivity to the moral and delicate dimensions of complaining.

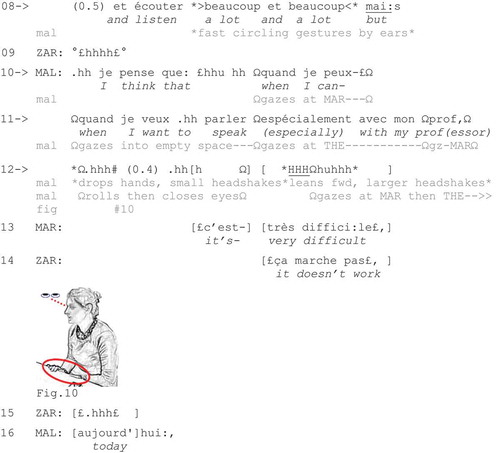

Excerpt 4 shows a similar case, although here the positive preface (lines 6–8) concerns the speaker herself. Malia will initiate a complaint telling about her recurrent difficulties speaking French with her supervisor (see line 11).

Ex. 4 (Mer1_2016-11-16_01:55_ parler_avec_prof)

After the coparticipants’ receipts of Malia’s story preface (lines 1–4), Malia asserts her efforts to study and listen a lot (presumably to French): j’essaie étudier beaucou:p, et écouter >beaucoup et beaucoup< (“I try study a lot, and listen a lot and a lot,” lines 6–8). By frowning and producing circling hand gestures when delivering the intensifier beaucou:p (“a lot,” lines 7–8), Malia animates and upgrades the strength of the positively valenced elements. Similar to Aurelia previously, Malia offers a prosodically prominent mai:s (“but,” line 8) to clearly project a contrast to follow. Zarah’s laughter in line 9 shows her anticipation of the upcoming contrast. In the continuation of her turn, Malia initiates a compound TCU with the dependent clause quand je peux- quand je veux .hh parler espécialement avec mon prof (“when I can- when I want to speak especially with my professor,” lines 10–11), as she gazes alternatively at her coparticipants, seeking close embodied contact with them. Instead of verbally completing the second part of the compound TCU, Malia offers an embodied completion (Olsher, Citation2004) with a display of heightened negative affectivity (Selting, Citation2012): She drops her hands on the table and starts shaking her head while taking two audible in-breaths and rolling her eyes before closing them (line 12, ), and she then lets out a loud sigh, leaning forward and shaking her head more markedly (line 12). Precisely timed with her sigh, both Mariana and Zarah offer grammatically fitted completions of Malia’s turn—namely, the independent clauses c’est très difficile (“it’s very difficult,” line 13) and ça marche pas (“it doesn’t work,” line 14). The strong projective force of the positively valenced element plus a contrastive conjunction, here also strengthened by the compound TCU structure, allow the coparticipants to anticipate the formulation of a problem and participate in the sequence by offering collaborative completions (Lerner, Citation1996), thereby affiliatively supporting the development of the sequence (Lerner, Citation2013). In the continuation of the sequence, Malia accounts for her expressed troubles by reporting on a specific complaint-worthy event the same day (line 16 and onward).

So far, I have shown a few different practices elementary speakers use to initiate complaints. Besides immediately launching high-grade negative assessments (Ex. 1), these speakers foreshadow negatively valenced talk through bodily-visual displays of negative stance during silence (Ex. 2) or non-lexical vocalizations, or use brief positively valenced, and hence contrastive, prefacing turns plus (often prosodically prominent) contrastive conjunctions (Ex. 3–4). The latter practices frequently recruit affiliative contributions from coparticipants in the form of candidate responses and turn completions that promote sequence development. In terms of linguistic resources, elementary speakers’ employment of contrastive prefaces testifies to their ability to use specific resources (positively valenced assertions plus the contrastive conjunction mais) for context-specific action purposes.

Upper-intermediate/advanced speakers

Upper-intermediate/advanced speakers in part rely on the same initiation practices as elementary speakers. In addition, they recurrently perform more elaborate prefatory work to prepare the grounds for their complaints before launching overt criticism or other explicit verbal stance expressions. They also initiate complaints jointly with other coparticipants by producing aligning and affiliative negative assessments in response to other speakers’ negative stance expressions. The observed differences involve a change over time in sequence organization, which is facilitated by speakers’ increasing ability to put to use linguistic resources for structuring longer turns and sequences and to synchronize talk with others.

Ex. 5 illustrates upper-intermediate/advanced speakers’ ability to prepare the grounds for complaints over longer stretches of talk. Through fine-grained prefacing work, speakers build up the complaint implicitly to hint at the complaint and enhance the legitimacy of the complaint and of themselves as complainants before launching overt criticism or a verbal formulation of the complainable. In Ex. 5, Aurelia tells about the reasons for moving out of her old, shared apartment. The format of Jordan’s question in lines 1–2 invites negatively valenced talk, but as seen in Aurelia’s first reported reason—that the apartment was too small (omitted lines)—it does not invite complaining per se. Aurelia expands her answer with a second reason, however, which leads to a complaint about her prior flatmate (line 56 and onward). Note Aurelia’s positive portrayal of another flatmate and her use of grammatical projection devices (conditional clauses: lines 56, 86, left-dislocation: line 90) and generic statements of morality (lines 60, 76, 89) to build up her complaint initiation.

Ex. 5 (Lun_2018-05-28_09:56_ partager)

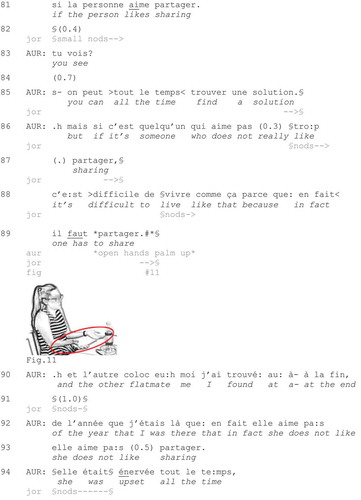

Aurelia begins her sequence expansion by asserting what is important if you live in a small apartment (lines 56–59)—that the two people “like sharing” (lines 60–61). The generic formulation c’est important (“it’s important,” line 60) carries a moral dimension, as it invokes “normative standards of conduct” (Drew, Citation1998, p. 297). Although formatted as a hypothetical statement through the if-clause si tu habites (“if you live,” line 56), this statement in its context after Aurelia’s description of the old apartment as too small is hearable as an implicit invocation of a problem related to the people living in her old apartment. As Jordan displays his listenership (line 63), Aurelia expands with a strongly positive portrayal of another flatmate (lines 64–73). Assessing him with the high-grade <incroyable> (“incredible,” line 65) and describing how she had a really good time with him as she came back from work (lines 68–71), Aurelia paints a picture of what it means to have a good flatmate, especially in the context of a small apartment where one has to share the kitchen (lines 75–77). Upon Jordan’s displays of alignment (see nods throughout Aurelia’s telling and verbal response tokens in lines 78–79), Aurelia restates her position that sharing a small place is okay if the person likes sharing (lines 80–81) since one can always find a solution (line 85). So far, Aurelia has thus (a) invoked normative moral expectations related to apartment sharing and foreshadowed a problem with this; (b) described an “ideal” flatmate who superseded such normative expectations; and (c) presented herself as someone who gets along with other, reasonable flatmates.

In line 86, Aurelia introduces the projected contrast with mais (“but”) followed by another hypothetical statement about someone who does not really like sharing (lines 86–87). She completes the compound TCU with another general assessment and an account: c’e:st >difficile de vivre comme ça parce que: en fait< il faut partager (“it’s difficult to live like that because in fact one has to share,” lines 88–89). Toward the end of her turn, Aurelia opens up her hands on the table with her palms facing up (), as if stating an obvious fact (Kendon, Citation2004). Aurelia thus contrasts her earlier hypothetical statement about the importance of “liking to share” in a small apartment with what happens if someone does not like sharing. Only after this does Aurelia name the object of her implied criticism: her other flatmate (line 90), who Aurelia eventually found out did not like sharing (lines 92–93). She escalates her negative stance expressions by claiming with an extreme-case formulation that the flatmate was “upset all the time” (line 94), and she backs up this high-grade negative assessment by reporting on a specific example of the flatmate’s transgressions (not shown).

The excerpt shows an elaborate work up to a complaint about a third party consisting of hypothetical statements about normative moral expectations involved in sharing an apartment, the description of an ideal flatmate, the portrayal of Aurelia herself as a reasonable flatmate, and a stepwise escalation of a negative other-portrayal. Through these actions, Aurelia works to account for and legitimize not only her criticism of her complaint-worthy flatmate but also to portray herself as a legitimate complainant (Drew, Citation1998; Edwards, Citation2005). Some of the linguistic resources used for accomplishing these actions are if-conditionals (lines 56, 86) and left-dislocations (see line 90) that allow Aurelia to insert framing information before completing the grammatical projection, and constructions for invoking normative moral expectations such as c’est important que (“it’s important that,” line 60) and il faut (“one has to/you have to,” lines 76, 89).

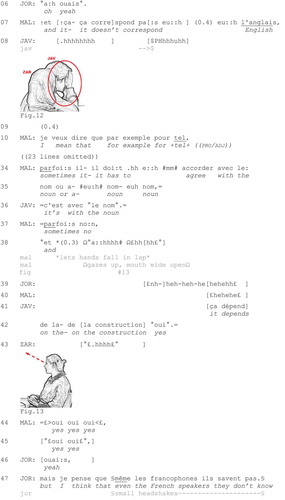

The final excerpt (Ex. 6) demonstrates the joint move into complaining through a collaborative process of progressive escalation of aligning and affiliative negative stance expressions (cf. Drew & Walker, Citation2009), something that rarely occurs among elementary speakers. Javier, Malia, and Jordan (all upper-intermediate/advanced speakers) have discussed in a lighthearted way the difficulty of an advanced French course that they all have taken or are currently attending. The discussion then moves to serious complaining about the difficulty of French through an escalation of negative talk (starting in lines 1–4).

Ex. 6 (Mer1_2017-10-11_29:32_attentes)

In lines 1–4, Javier initiates more serious talk about the difficulty of reaching high mastery of French and assesses the situation as vrai fou (“real crazy”) before launching an account (lines 3–4). Instead of verbally completing his turn initiations, he embodiedly expresses negative stance by lowering his head (lines 2, 4) and by covering his face with his hands () in what becomes recognizable as a negative assessment of the “construction” of the French language (see the initiation c’est [“it’s”], line 4, which Javier completes with bodily-visual conduct and a deep sigh, line 8). Whereas Jordan offers an agreement token (line 6), Malia produces a second, upgraded assessment (Pomerantz, Citation1984) of the French language that also works as an account for Javier’s assessment, ↑et ↑ça- ça correspond pa:s eu::h (0.4) eu::h l’anglais, (“and it- it doesn’t correspond English,” line 7), delivered with heightened affectivity (see high pitch and stress). By formatting her turn as a continuation of Javier’s turn and offering another account for his assessment, Malia shows strong affiliation with Javier and contributes to the development of the sequence into a joint complaint.

Malia justifies her own assessment by offering a precise example pertaining to the French word tel (approx. “such”), which can be used both as a pronoun and an adjective. She reports what she found out in the advanced course—that there are multiple different meanings of tel (omitted lines) with different rules for its inflection (lines 34–35, 37). Following this account, Malia too produces a nonverbal assessment through a voiced sigh (line 38) and a bodily-visual expression of exasperation ().

Having already expressed his affiliation (see laughter in line 39) and agreement with Malia and Javier (line 46), Jordan initiates the next expansion of the sequence by claiming that not even the French speakers “know” (line 47). The prosodic emphasis on même (“even”) and Jordan’s headshakes contribute to the plaintive tone of this assertion, which supports Javier and Malia’s prior claims about the difficulty of the French language and implies the unrealistic expectations for L2 speakers to learn something that not even L1 speakers master. By invoking the category les francophones (“the French speakers”), Jordan also positions himself and his L2 coparticipants in a different category than L1 speakers. Javier and Malia’s agreeing responses (lines 49–50), and specifically Malia’s loud, affect-laden EXA:CTE EXACTE (“exact exact,” line 50) confirm their interpretation of Jordan’s turn as a criticism and lead to further affiliative stance displays through which the participants agree on the unreasonable expectations.

The sequence shows the collaboratively accomplished escalation from an expression of personal despair (by Javier) to a joint complaint, realized through affect-laden displays of frustration (by Malia) to a generalized accusation and invocation of a common “we” against “the other” (by Jordan). Crucial for the escalation of the sequence into a complaint are the participants’ ability to produce timely and affiliative second assessments and negatively valenced observations and to build on each other’s turns.

To sum up, although upper-intermediate/advanced speakers in part use the same practices as elementary speakers to move into complaining, they regularly initiate complaints in a stepwise manner by preparing the grounds for the complaint over longer stretches of talk, and they increasingly initiate complaints jointly with coparticipants. Consequently, the proportion of complaints initiated through immediate criticism or other (high-grade) negative stance expressions is smaller than among elementary speakers. shows a comparative overview of the main initiation features across proficiency levels, documenting quantitatively the tendencies illustrated through the qualitative analyses.

Table 2. Overview of interactional features of complaint initiations across proficiency levels

On the one hand, the documented change pertains to sequence organization: Instead of first offering high-grade negative stance expressions and then an account, upper-intermediate/advanced speakers recurrently work to account for and legitimize the upcoming complaint before launching strong verbal expressions of negative stance. Such prefatory work thus preemptively manages the accountability of the complaint, presumably to enhance the chance of obtaining affiliative responses. On the other hand, the change manifests in and is facilitated by a range of interactional resources: Through hypothetical comparisons between moral ideals and third parties (Ex. 5), generic claims of morality (Ex. 5), and so-called first verb constructions (not shown; see Schulze-Wenck, Citation2005), upper-intermediate/advanced speakers imply criticism or trouble that they eventually verbalize in explicit terms. If-conditionals, left-dislocations, and pseudo-clefts are some of the grammatical resources used to secure longer turns. In addition, these speakers more often than elementary-level speakers initiate complaints jointly by producing aligning and affiliative negative stance expressions in response to coparticipants’ stance displays (Ex. 6).

Discussion

The analysis has documented differences in how elementary and upper-intermediate/advanced speakers of French initiate complaints. These differences suggest that speakers, over time, diversify their practices for moving into complaining. This diversification involves a change in sequence organization, whereby upper-intermediate/advanced speakers regularly deploy extensive prefatory work that allows them to enter into complaining in ways that index the contingent, moral, and delicate nature of the activity (Drew, Citation1998; Heinemann & Traverso, Citation2009; Ruusuvuori et al., Citation2019). They also initiate complaints jointly by closely coordinating and building on each other’s expressions of negative stance. Such initiations occur only occasionally among elementary speakers, suggesting a gradual change toward structurally more complex and co-constructed complaint initiations over time.

The ability of upper-intermediate/advanced speakers to initiate complaints in a more stepwise manner converges with findings about L2 speakers’ practices for dealing with other delicate actions, such as disagreements (Pekarek Doehler & Pochon-Berger, Citation2011) and requests (Al-Gahtani & Roever, Citation2012), as well as with studies on L2 speakers’ storytelling prefaces (Hellermann, Citation2008; Pekarek Doehler & Berger, Citation2018). In all these cases, speakers show increasing tendency over time to preface their actions with talk that works to maintain social solidarity between the participants and, especially in the case of storytellings, helps coparticipants anticipate what is coming. Although the foreshadowing and delay of explicit criticism through silence and embodied conduct and contrastive turn prefaces to some extent serve such purposes, elaborate workups further enhance the chances of receiving aligning and affiliative responses from coparticipants.

The findings highlight the role of particular interactional (linguistic, multimodal) resources for structuring longer turns and sequences of actions and for indexing stance in complaint initiations. Upper-intermediate/advanced speakers deploy a large repertoire of grammatical resources for projection (Pekarek Doehler, Citation2011) in their initiations, such as conditional clauses, pseudo-clefts, and “first verb” constructions, that can be used to suspend the turn-taking machinery to allow for a multi-unit turn. Most of these resources are not specific to complaints and indicate speakers’ generally enhanced capacity to engage in long sequences of actions. Some of the linguistic resources prove especially helpful for subtly implying criticism or trouble, however—such as the pragmatic projection device of “first verb” constructions (see Schulze-Wenck, Citation2005)—allowing speakers to implicitly convey complaints before verbalizing them in explicit terms. Such resources thus play more into the stance-taking dimension of complaining, while also projecting a particular upcoming action. As shown in Ex. 2, embodied conduct can similarly convey stance early in the sequence but lacks the turn-taking function of linguistic projection devices. Upper-intermediate/advanced speakers’ regular use of linguistic resources for projection in complaint initiations demonstrates these speakers’ developing L2 grammar-for-interaction (Pekarek Doehler, Citation2018).

More advanced speakers’ increased tendency to initiate complaints jointly through an escalation of negative stance displays reflects their growing ability to synchronize their actions with others in timely and fitted ways. As shown, for example by Sert (Citation2019), with time L2 speakers diversify their practices for building on other speakers’ turns, and they increasingly respond in a well-timed manner. Upper-intermediate/advanced speakers’ capacity to produce timely and aligning (and specifically upgrading) second assessments (Pomerantz, Citation1984) and stance expressions helps them engage in joint complaints. Since joint complaining requires collaboration (Drew & Walker, Citation2009), it is, however, not enough for one speaker to develop his/her interactional practices. The progressively more frequent joint complaint initiations rather reflect a concurrent change in the interactional abilities of several participants, resulting in a participation framework that is generally more apt for joint complaining than in elementary-level groups.

The documented change in practices for initiating complaints raises questions about the possibility of maintaining an emic perspective while interpreting such change in terms of the development of L2 interactional competence (cf. Deppermann & Pekarek Doehler, Citation2021/this issue). As illustrated in Ex. 1, sequence-initiations in the form of high-grade negative assessments are sometimes troublesome—here leading to a side-sequence addressing the hyperbolic nature of the assessment and interrupting progressivity. This is not always the case in my data, however, as initiations through high-grade negative stance expressions sometimes go unaddressed. A possible explanation for this is the general “permissiveness” often observable in L2 interactions, whereby speakers show a high tolerance toward practices that in L1 talk would be considered problematic. But if particular practices are treated by coparticipants as competent conduct at time X (e.g., at elementary level), how can we emically argue for increased competency at time X+1 (e.g., at upper-intermediate/advanced level), if participants do not ostensibly orient to longitudinal development in their practices (cf. Wagner et al., Citation2018)? Although I do not have any definite answer to this question, a few words about my own analytical approach are in order. To ensure a basic emic analysis, I have applied strict sequential analysis and not relied on any exogenous learning theory in analyzing the data (which is sometimes the case in L2-learning research). In addition, I suggest that the similarity in the documented differences over time across several participants indicates that these participants themselves consider certain interactional practices “better” than others, showing their emic orientations to what it means to be a competent L2 French speaker in the particular interactional setting—regardless of how their conduct is treated by coparticipants. Such observation is only possible when including several participants in the analysis; underlining the need to rely on a sufficiently large data set for longitudinal comparison. Quantification of practices helps to a certain extent, as it shows tendencies in proportional change over time.

To conclude, the study documents change over time in French L2 speakers’ methods for initiating complaints. Upper-intermediate/advanced speakers’ increased prefatory work and ability to synchronize their actions with others allow them to better account for and legitimize their complaints and move into complaining in a stepwise manner, showing an enhanced capacity for dealing with delicate actions (Lerner, Citation2013). These speakers’ more diverse practices for initiating complaints hence provide them with enhanced possibilities for adjusting their initiations to different interactional contexts and recipients. As argued elsewhere (e.g., Pekarek Doehler & Berger, Citation2018), such increased ability for context-sensitive and recipient-designed conduct lies at the very heart of what it means to be interactionally competent.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Transcriptions adopt Jeffersonian conventions complemented by Mondada’s (Citation2019) principles for indicating embodied conduct.

References

- Al-Gahtani, S., & Roever, C. (2012). Proficiency and sequential organization of L2 requests. Applied Linguistics, 33(1), 42–65. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amr031

- Council of Europe. (2020). Common European framework of reference for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment – Companion volume.

- Deppermann, A., & Pekarek Doehler, S. (2021/this issue). Longitudinal conversation analysis – introduction to the special issue. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 54(2), 127–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2021.1899707

- Drew, P. (1998). Complaints about transgressions and misconduct. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 31(3–4), 295–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.1998.9683595

- Drew, P., & Holt, E. (1988). Complainable matters: The use of idiomatic expressions in making complaints. Social Problems, 35(4), 398–417. https://doi.org/10.2307/800594

- Drew, P., & Walker, T. (2009). Going too far: Complaining, escalating and disaffiliation. Journal of Pragmatics, 41(12), 2400–2414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2008.09.046

- Edwards, D. (2005). Moaning, whinging and laughing: The subjective side of complaints. Discourse Studies, 7(1), 5–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445605048765

- Haakana, M. (2012). Laughter in conversation: The case of “fake” laughter. In A. Peräkylä & M.-L. Sorjonen (Eds.), Emotion in interaction [Electronic resource]. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199730735.003.0008

- Heinemann, T., & Traverso, V. (2009). Complaining in interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 41(12), 2381–2384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2008.10.006

- Hellermann, J. (2008). Social actions for classroom language learning. Multilingual Matters.

- Hoey, E. M. (2014). Sighing in interaction: Somatic, semiotic, and social. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 47(2), 175–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2014.900229

- Jefferson, G. (1988). On the sequential organization of troubles-talk in ordinary conversation. Social Problems, 35(4), 418–441. https://doi.org/10.2307/800595

- Kendon, A. (2004). Gesture: Visible action as utterance. Cambridge University Press.

- Kunitz, S., & Yeh, M. (2019). Instructed L2 interactional competence in the first year. In R. Salaberry & S. Kunitz (Eds.), Teaching and testing L2 interactional competence (pp. 228–259). Routledge.

- Lerner, G. H. (1996). On the “semi-permeable” character of grammatical units in conversation: Conditional entry into the turn space of another speaker. In E. Ochs, E. Schegloff, & S. Thompson (Eds.), Interaction and grammar (Studies in Interactional Sociolinguistics, pp. 238–276). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511620874.005

- Lerner, G. H. (2013). On the place of hesitating in delicate formulations: A turn-constructional infrastructure for collaborative indiscretion. In M. Hayashi, G. Raymond, & J. Sidnell (Eds.), Conversational repair and human understanding (pp. 95–134). Cambridge University Press.

- Mondada, L. (2019). Conventions for multimodal transcription. https://www.lorenzamondada.net/multimodal-transcription

- Olsher, D. (2004). Talk and gesture: The embodied completion of sequential actions in spoken interactions. In R. Gardner & J. Wagner (Eds.), Second language conversations (pp. 221–245). Continuum.

- Pekarek Doehler, S. (2011). Clause-combining and the sequencing of actions: Projector constructions in French conversation. In R. Laury & R. Suzuki (Eds.), Subordination in conversation: A crosslinguistic perspective (pp. 103–148). John Benjamins.

- Pekarek Doehler, S. (2018). Elaborations on L2 interactional competence: The development of L2 grammar‐for-interaction. Classroom Discourse, 9(1), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/19463014.2018.1437759

- Pekarek Doehler, S., & Balaman, U. (this issue). The routinization of grammar as a social action format: A longitudinal study of video-mediated interactions.

- Pekarek Doehler, S., & Berger, E. (2018). L2 interactional competence as increased ability for context-sensitive conduct: A longitudinal study of story-openings. Applied Linguistics, 39(4), 555–578. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amw021

- Pekarek Doehler, S., & Pochon-Berger, E. (2011). Developing ‘methods’ for interaction: Disagreement sequences in French L2. In J. K. Hall, J. Hellermann, & S. Pekarek Doehler (Eds.), L2 interactional competence and development (pp. 206–243). Multilingual Matters.

- Pomerantz, A. (1984). Agreeing and disagreeing with assessments: Some features of preferred/dispreferred turn shapes. In J. M. Atkinson & J. Heritage (Eds.), Structures of social action (pp. 57–101). Cambridge University Press.

- Pomerantz, A. (1986). Extreme case formulations: A way of legitimizing claims. Human Studies, 9(2–3), 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00148128

- Ruusuvuori, J., Asmuß, B., Henttonen, P., & Ravaja, N. (2019). Complaining about others at work. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 52(1), 41–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2019.1572379

- Ruusuvuori, J., & Peräkylä, A. (2009). Facial and verbal expressions in assessing stories and topics. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 42(4), 377–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351810903296499

- Sacks, H. (1992). Lectures on conversation. Basil Blackwell.

- Schegloff, E. A. (2005). On complainability. Social Problems, 52(4), 449–476. https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.2005.52.4.449

- Schulze-Wenck, S. (2005). Form and function of ‘first verbs’ in talk-in-interaction. In A. Hakulinen & M. Selting (Eds.), Syntax and lexis in conversation: Studies on the use of linguistic resources in talk-in-interaction (pp. 319–348). John Benjamins.

- Selting, M. (2012). Complaint stories and subsequent complaint stories with affect displays. Journal of Pragmatics, 44(4), 387–415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2012.01.005

- Sert, O. (2019). The interplay between collaborative turn sequences and active listenership: Implications for the development of L2 interactional competence. In R. Salaberry & S. Kunitz (Eds.), Teaching and testing L2 interactional competence (pp. 228–259). Routledge.

- Skogmyr Marian, K. (2020). The development of interactional competence in a second language: A multimodal analysis of complaining in French interactions [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Neuchâtel.

- Skogmyr Marian, K., & Balaman, U. (2018). Second language interactional competence and its development: An overview of conversation analytic research on interactional change over time. Language and Linguistics Compass, 12(8), e12285. https://doi.org/10.1111/lnc3.12285

- Traverso, V. (2009). The dilemmas of third-party complaints in conversation between friends. Journal of Pragmatics, 41(12), 2385–2399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2008.09.047

- Wagner, J., Pekarek Doehler, S., & González-Martínez, E. (2018). Longitudinal research on the organization of social interaction: Current developments and methodological challenges. In S. Pekarek Doehler, E. González-Martínez, & J. Wagner (Eds.), Longitudinal studies on the organization of social interaction (pp. 3–35). Palgrave Macmillan.