Abstract

This study aims to offer novel means for rethinking contemporary business-to-business (B2B) sales operations and the assumptions that underlie them in the digital era. This rethinking relates especially to sales managers’ efforts to facilitate cognitive unlearning in B2B sales management during the ongoing digital transformation taking place in enterprises. Unlearning—the process of purposely reflecting on and discarding old ways of knowing and doing—is crucial to prevent outdated organizational knowledge and routines from becoming a barrier to change. Before adopting new sales practices, sales organizations must first discard old ways of knowing and doing. Drawing insights from unlearning and B2B sales management literature and conducting empirical qualitative research on 31 executives and senior managers operating in various industries, the study outlines a four-phase process for unlearning as well as several key themes within each phase. The findings emphasize how top management facilitates cognitive unlearning regarding digital business transformation in the B2B sales context. The study contributes to sales management literature by introducing cognitive unlearning as a new theoretical angle on the issue of digital transformation. It also offers insights for sales managers on how to elevate and leverage the unlearning of salespeople.

Digital transformation creates a need to unlearn in B2B sales

Business-to-business (B2B) selling and sales processes are being challenged by major disruptions brought about by advanced selling technologies, artificial intelligence, machine learning, and new digital working environments (Singh et al. Citation2019; Syam and Sharma Citation2018; Thaichon et al. Citation2018). Several studies have shown that the use of digital tools and technologies in B2B sales increases revenue, profitability, effectiveness, and understanding of the customers’ needs (Ahearne and Rapp Citation2010; Rodriguez et al. Citation2016). A recent commercial study by Bages-Amat et al. (Citation2020) shows that the Covid-19 pandemic has also changed buying and selling, with 70–80% of decision makers preferring to make purchases remotely or using self-service.

Alongside its opportunities, the adoption of sales technologies often involves multiple tradeoffs for the sales organization and salespeople (Hunter and Perreault Citation2007). Efforts have been made to unravel what kinds of changes advanced technologies and social media platforms (e.g., LinkedIn) bring to the organizing and management of salespeople (see, e.g., Agnihotri Citation2020; Cuevas Citation2018; Guenzi and Habel Citation2020; Thaichon et al. Citation2018). For example, Thaichon et al. (Citation2018) have argued that sales forces should combine both online and offline sales operations and that value creation requires tight collaboration between various teams in sales organizations (Thaichon et al. Citation2018). Customers’ complex demands and needs have led to the creation of new types of sales teams, which include salespeople and other actors, such as technical experts and marketing professionals (see, e.g., Cuevas Citation2018; Hartmann, Wieland, and Vargo Citation2018; Syam and Sharma Citation2018). Presented with new possibilities and requirements, sales professionals may be suspicious of new technologies (Rangarajan et al. Citation2020) and thus reluctant to accept and employ them in their jobs (Rodriguez, Peterson, and Krishnan Citation2012). Salespeople are reportedly concerned with the possible automation of sales tasks (Valdivieso de Uster Citation2020) and the redivision of labor between the salesperson and customer (Mahlamäki et al. Citation2020; Moncrief Citation2017).

As sales work changes in fundamental ways, current ways of knowing and doing are in danger of becoming obsolete. At the same time, to learn new routines, channels, and about new information sources, sales organizations must also selectively discard old information and behaviors (Lacoste Citation2018). This paper focuses on the latter process, which we refer to as unlearning. Unlearning—the process of purposely reflecting on and discarding old ways of knowing and doing (Akgün et al. Citation2007; Klammer and Gueldenberg Citation2019; Martin de Holan and Phillips Citation2011; Tsang and Zahra Citation2008)—is vital because outdated beliefs and/or routines can hinder learning (Tsang Citation2008, 17). The adoption of new technologies will be unsuccessful if salespeople continue to rely on knowledge or routines that are obsolete in the new digital environment.

Previous studies have indicated that sales managers play an important role in facilitating performance in sales organizations (Plank et al. Citation2018; Singh et al. Citation2019). However, limited theoretical and empirical guidance exists on what digital transformation requires from sales managers themselves. How should sales leaders—that is, professionals who fully or partly act in a management role in a sales organization (Plank et al. Citation2018)—and managers enact change that, for example, simultaneously ensures knowledge regeneration and novel ways of working? Guenzi and Habel (Citation2020) outline a descriptive strategy model for managing digital transformation and utilizing digital sales tools in B2B sales organizations but largely neglect the human side of digital transformation of sales, such as how sales managers practically support their sales forces in changing work practices. How sales managers encourage the unlearning of salespeople remains particularly unexplored. To the best of our knowledge, only one recent study in sales literature has touched upon unlearning, arguing that several skills, such as the capability to recognize and capitalize on opportunities and to create services that fit customer needs, must be unlearned to enable a transition from traditional to strategic selling techniques and management (Lacoste Citation2018). The study, however, neglects to consider both digital transformation and the managerial view, which is a core focus of this study.

The current study introduces a novel theoretical angle to sales management literature—unlearning—to demonstrate the many ways sales managers are currently prompting their organizations to discard obsolete knowledge and practices and enact the changes brought by digitalization. Scholars have called for more research on the mechanisms through which unlearning unfolds as well as the challenges organizations face during unlearning (Hislop et al. Citation2014; Mehrizi and Lashkarbolouki Citation2016; Yildiz and Fey Citation2010). For instance, Klammer and Gueldenberg (Citation2019) highlight the need for more research on the enablers of and barriers to unlearning. Commercial articles and papers discuss digital transformation, but until now, they have not been able to help sales managers in leading and managing digital transformation. This study explores cognitive unlearning at an organizational level (Becker Citation2008, Citation2010; Klammer and Gueldenberg Citation2019). Contextually, the study is positioned in the B2B sales context and considers the ongoing digital transformation of small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and large enterprises. It adopts a managerial view because executives and (senior) managers are expected to play a crucial role in enterprises’ digital transformation. Hence, we set the following research question: “How can managers facilitate cognitive unlearning in light of the digital transformation taking place in B2B sales?”

With reference to sales management literature, this study analyzes a qualitative data set of 31 semi-structured interviews with executives and senior managers from SMEs and large enterprises (more than 1,000 employees), to identify a four-phase cognitive unlearning process and analyzes 10 critical related factors. Hence, the study provides a new perspective on the digital transformation occurring in B2B sales by focusing on how cognitive unlearning takes place in this context. Our study will benefit sales executives and managers who are enacting digital transformation in their sales organizations by highlighting how they can encourage and facilitate the abandonment of outdated and unhelpful ways of knowing and doing.

Theoretical framework

Digital transformation of B2B sales

The adoption of new technology has a long history in sales practice and research. Generally, taking up sales technology has been shown to help salespeople to develop deeper customer relationships (Rodriguez and Honeycutt Citation2011). However, the adoption of sales technologies usually involves multiple tradeoffs, and its performance implications are nuanced and often poorly understood (Hunter and Perreault Citation2007). Moreover, enterprises are now moving beyond ‘mere’ technology adoption into digitalization-enabled modification of the business model and strategy, usually called digital transformation. In consultant terms, digital transformation refers to “the process of using digital technologies to create new—or modify existing—business processes, culture, and customer experiences to meet changing business and market requirements” (Salesforce Citation2020; see also Guenzi and Habel Citation2020). The digital transformation of sales can also be defined as the “application of digitization and AI technologies to company assets as a means to improve competencies and rethink the value proposition of the firm” (Singh et al. Citation2019, 5). While many technologies allow salespeople to improve existing work processes, they can also enable sales representatives to provide value in new ways (Hunter and Perreault Citation2007), including, for instance, through the digitalization of internal or customer-interaction processes with the aim of improving efficiency or effectiveness (Guenzi and Habel Citation2020).

According to one highly cited article (Ahearne and Rapp Citation2010), technologies can either be salesperson-oriented (used exclusively by the salesperson), customer-oriented (used exclusively by the customer), or shared (interactive technologies, such as social media). While a full review of contemporary sales technologies is beyond the scope of this study, brief definitions and examples of technologies driving the digital transformation of B2B sales are outlined in .

Table 1. Illustrative examples of technologies driving the digital transformation of B2B sales.

Some professionals estimate that up to 40% of sales tasks can be automated (Valdivieso de Uster Citation2020). Many claim that this automizing has led to fundamental changes in both buying and sales processes, for example, by reconfiguring the division of labor between the salesperson and the customer (see, e.g., Mahlamäki et al. Citation2020; Moncrief Citation2017; Rangarajan et al. Citation2020). With automated sales processes, customers can find needed products or services quickly and perform simple transactions without a salesperson (Thaichon et al. Citation2018). Nonetheless, salespeople still play an important role when customers require more complicated products or services (Ahearne and Rapp Citation2010; Cuevas Citation2018).

B2B salespeople are making use of digital platforms where opportunities for influencing and interacting with customers are wider than before (Sheth and Sharma Citation2008; Thaichon et al. Citation2018). There are various types of platforms, such as search, social media, and payment platforms (Rangaswamy et al. Citation2020). While some cater primarily to the needs of advertisers and consumers, others offer functionalities, such as matchmaking and the introduction of complementary offerings, that are relevant from a B2B selling viewpoint. The essential characteristic of platforms is their ability to unite and mediate the transactions and interactions of multiple parties, such as buyers, sellers, and complementors (McIntyre and Srinivasan Citation2017; cf. Rangaswamy et al. Citation2020; Gawer Citation2014; de Reuver, Sørensen, and Basole Citation2018). The notion of complementors is important as these firms can enhance a platform’s value by adding their own goods and services to it (Gawer Citation2014; McIntyre and Srinivasan Citation2017). These meta-organizations pool together and coordinate various resources for value creation and capture (Cusumano, Gawer, and Yoffie Citation2019; Gawer Citation2014; Mathmann et al. Citation2017; Vadana et al. Citation2019). In a B2B sales setting, digital platforms can function as scalable sales tools for sales organizations in which customers can self-serve on their buying journey, consequently allowing several actors, including nontraditional ones (e.g., technical staff), together with salespeople to create value with customers (Hartmann, Wieland, and Vargo Citation2018).

Digital platforms spark practitioner and researcher interest through their ability to transform how customers, suppliers, and other participants interact (Mathmann et al. Citation2017). Importantly, on digital platforms, the roles users play can become blurred, allowing a user to be both a customer and a seller (Kumar, Lahiri, and Dogan Citation2018). The success of a digital platform depends on the size of its user base (Gawer and Cusumano Citation2014) and especially the number of attractive users the platform can attract (Haucap and Heimeshoff Citation2014), highlighting the vital role of sales and marketing.

Finally, in the B2B sales context, social media technologies can enable salespeople to “pull” customers with social content or improve engagement via social networking (Agnihotri Citation2020). These customer-oriented technologies (Agnihotri Citation2020) have been shown to improve both sales processes and performance (see, e.g., Rodriguez, Peterson, and Krishnan Citation2012). Studies have demonstrated that the use of social media is beneficial for SMEs’ growth as it brings a deeper knowledge of customers and, consequently, leads to better revenue (Ahearne and Rapp Citation2010; Marshall et al. Citation2012; Rodriguez, Peterson, and Krishnan Citation2012).

Managerial role in digital transformation of B2B sales

As sales professionals must accept and employ new sales technologies in their jobs before those technologies can lead to improved performance (Rodriguez, Peterson, and Krishnan Citation2012), managers play a key role in motivating and justifying these developments. Managers need to gain “buy-in” from salespeople suspicious of new technologies and should reassure salespeople that new technologies will support, not replace, them (Rangarajan et al. Citation2020). Sales leaders’ commitment and empowering behaviors can improve salespeople’s technology use and performance (Mathieu, Ahearne, and Taylor Citation2007). Sales leaders can also promote improved sales performance through their coaching, collaborating, championing, and customer-engaging behaviors (Peesker et al. Citation2019). Nonetheless, the role of management in the digital transformation of B2B sales is multifaceted. While scholars have called for research that provides methods for sales managers to operate during changing times (Singh et al. Citation2019), studies until now have largely neglected the issue of how managers can organize and lead digital transformation in their sales organizations. What do managers do to enact digital transformation? How are they supported in this mission for more digitized and effective sales management? What effects do their decisions have on their staff? What role does unlearning play in these processes?

Recently, one empirical study has provided a model for managing the digital transformation and utilization of digital sales tools in B2B sales organizations and is based on a process that emerges as a digital sales transformation strategy (Guenzi and Habel Citation2020). However, this study fails to consider the role of human capital in digital transformation and required changes in the sales force’s working practices. Coaching has been discussed as a method that supports the dissemination of new ways of working (Shannahan, Shannahan, and Bush Citation2013), with coaching on individual development and the sales process (including strategic customer engagement and the salesperson’s metrics, both lagging and leading) facilitating successful sales (Peesker et al. Citation2019). Such discussions, however, leave sales managers wondering how to create a digitally enabled environment that supports learning, knowledge sharing, and culture in a way that encourages feedback, empowers the sales force, and develops the competencies of their sales teams.

The complex digital environment requires quick learning, especially in terms of regularly challenging and re-innovating ways to create value with customers (see, e.g., Guenzi and Habel Citation2020; Hartmann, Wieland, and Vargo Citation2018). Learning, such as building new ways of thinking about customers, involves a multilevel reflection process in which sales managers have an important role in facilitating sales personnel’s work in buyer-seller interactions (Kaski, Ari, and Pullins Citation2019). Customers’ changing buying behaviors further challenge sales personnel’s capabilities and adaptability to gauge customers’ expectations. The digital transformation, together with new ways of value creation facilitated by customers, tests the sales force’s structures, strategies, and capabilities (Singh et al. Citation2019; Thaichon et al. Citation2018). For the future, sales organizations’ competence requirements have been argued to include cognitive competencies, such as innovative problem solving, analytical abilities, and information processing, to address pressures brought by turbulent digital environments (Cuevas Citation2018).

Conceptualizing unlearning

Individuals and organizations retain their current beliefs and practices as long as they remain successful (Starbuck Citation1996). However, when large shifts in the environment make certain beliefs and practices obsolete, unlearning these ways of knowing and doing becomes necessary (Klammer and Gueldenberg Citation2019; Zhao, Lu, and Wang Citation2013). Multiple scholars have recognized the importance of unlearning as well as the need for more conceptual, and especially empirical, studies to better understand how the concept should be defined, conceptualized, or measured (Akgün et al. Citation2007; Becker Citation2010; Klammer and Gueldenberg Citation2019; Martin de Holan and Phillips Citation2011; Tsang and Zahra Citation2008).

The concept of unlearning is important as it focuses on the pain and anxiety inherent in major interruptions, which are sometimes ignored by organizational learning theorists (Visser Citation2017). Unlearning can simply be understood as the “purposeful destruction of established knowledge” (Martin de Holan and Phillips Citation2011, 443) or “the discarding of old routines to make way for new ones, if any” (Tsang and Zahra Citation2008, 1437). Unlearning is crucial because the “shadow of old routines” can hinder learning new ways of conducting commercial transactions (Tsang Citation2008, 17). At an organizational level, unlearning refers to organizations’ intentional practices to cope with their dependence on obsolete knowledge, routines, and processes (Akgün et al. Citation2007; Hedberg Citation1981; Mehrizi and Lashkarbolouki Citation2016). (For reviews on unlearning, see, e.g., Hislop et al. [Citation2014], Klammer and Gueldenberg [Citation2019], and Tsang and Zahra [Citation2008]).

Simply put, through unlearning, changes can occur in beliefs and/or routines (Akgün et al. Citation2007). More specifically, unlearning can involve various organizational elements, including the knowledge of managers and employees (see, e.g., Lohrke, Bedeian, and Palmer Citation2004), the schemas and behaviors of teams (see, e.g., Akgün et al. Citation2007), organizational memory and routines (Tsang Citation2008), outdated technologies (Starbuck Citation1996), cultural norms and values (Yildiz and Fey Citation2010), and business models (Mehrizi and Lashkarbolouki Citation2016). Organizational unlearning has mostly been conceptualized as occurring through the interrelated dynamics of cognitive unlearning and behavioral unlearning (Hedberg Citation1981; cf. Akgün et al. Citation2007). Cognitive unlearning means that managers and employees interpret, reflect on, and make sense of the limitations and problems of current knowledge, routines, technologies, and values (Starbuck Citation1996; Tsang and Zahra Citation2008; Zhao, Lu, and Wang Citation2013). These managers and employees then discuss their understanding by critically examining taken-for-granted assumptions and mindsets/mental models. Finally, these actors collectively revise their views (Bettis and Prahalad Citation1995). Behavioral unlearning involves actual collective actions to reduce or stop reliance on obsolete or irrelevant beliefs, routines, and technologies (Hedberg Citation1981; Mehrizi and Lashkarbolouki Citation2016). As unlearning requires a change in the frame of reference, individual mental models, stereotypes, or mindsets might lead the individual to resist unlearning. Unlearning, therefore, requires that individuals have the ability and willingness to discard obsolete routines (Zhao, Lu, and Wang Citation2013).

Social processes within an organization can also lead to unlearning (McKeown Citation2012). In such a view, some organizational knowledge and routines are socially ingrained and conform to a certain social order within the organization, making them hard to unlearn (Tsang Citation2008). Further, the role of emotions in unlearning should not be overlooked (Klammer and Gueldenberg Citation2019) because unlearning involves substantial emotional work (Akgün et al. Citation2007; McKeown Citation2012). Unlearning can give rise to negative emotions, such as anxiety, fear, confusion, guilt, or rage, because individuals may have invested emotions and even identity into the established ways of understanding and doing (Hislop et al. Citation2014). A psychologically safe and supportive environment is necessary in such cases (Brook et al. Citation2016; Visser Citation2017).

Processes for unlearning are likely to vary significantly depending on the underlying objects of unlearning (Hislop et al. Citation2014; Tsang Citation2008; Yildiz and Fey Citation2010; Mehrizi and Lashkarbolouki Citation2016). For example, Yildiz and Fey (Citation2010) found large differences between unlearning beliefs, norms, and behavioral patterns. Mehrizi and Lashkarbolouki (Citation2016) suggest that unlearning different elements requires distinct mechanisms to unbundle established links and reduce attachments to them. For example, irrelevant past knowledge is often harder to forget than problematic routines, which might be unlearned by simply not enacting them for a while (Tsang Citation2008). Unlearning deep-seated elements, such as core values and assumptions, may prove even more difficult (Hislop et al. Citation2014).

In B2B sales, digitalization and the platform economy have put strain on salespeople’s traditional practices. As the composition of sales teams diversifies and sales becomes a collaborative effort, a single salesperson will be unable to take credit for a successful sale. Overreliance on current ways of conducting business, deeply intertwined with all organizational aspects, can negatively impact on business by narrowing managers’ minds and biasing all decision-making to enforce existing business logic (Bettis and Prahalad Citation1995). Therefore, a business should be prepared to “break the rules that had previously guided its success” (Johnson, Christensen, and Kagermann Citation2008, 66).

Mechanisms of unlearning: process, antecedents, and consequences

As a process, unlearning can involve abandoning organizational values, norms, and/or behaviors through altering ways of understanding, such as cognitive structures, mental models, or dominant logics (see, e.g., Zhao, Lu, and Wang Citation2013). Unlearning begins when a person or organization realizes that their knowledge is obsolete or no longer useful and then makes a deliberate effort to end any routines involving this knowledge. This can happen, for example, when a person enters a new organization (Tsang and Zahra Citation2008), and, of course, organizations unlearn through their individuals (Becker Citation2008, Citation2010; Klammer and Gueldenberg Citation2019). Sometimes individual unlearning, however, might not reach the organizational level, or, alternatively, the individual might fail to unlearn even though the organization abandons old ways of knowing and doing (Klammer and Gueldenberg Citation2019; see also Hedberg Citation1981).

Some authors highlight that unlearning should be seen as a process of reflection (Brook et al. Citation2016; Mehrizi and Lashkarbolouki Citation2016), withing individuals unlearning by reflecting on their own actions and performance to identify which should be changed to improve performance (Cegarra-Navarro and Rodrigo-Moya Citation2005). From the B2B sales managers’ perspective, it is important to systematically build a culture that gives every team member opportunities to contribute to discussions on how to, for example, build superior value in complex and digitized environments (Kaski, Ari, and Pullins Citation2019).

Research has revealed numerous antecedents for unlearning, leading to managerial suggestions on how to initiate or enhance unlearning (see, e.g., Easterby-Smith and Lyles Citation2011). Unlearning is typically triggered by a problem (Hedberg Citation1981), as well as crises and stress (Klammer and Gueldenberg Citation2019). Managers can, therefore, facilitate unlearning by creating a sense of urgency or by bringing in outsiders to challenge existing worldviews and prevent groupthink (Akgün, Lynn, and Yılmaz Citation2006). Especially if the firm’s environment is turbulent, relying on past experiences is likely to be insufficient for success (Visser Citation2017). However, realizing that novel experiences cannot be interpreted with current belief systems instigates unlearning (Lant and Mezias Citation1992), while reflexivity can also have a positive effect (Lee and Sukoco Citation2011). To ease unlearning, managers should remain skeptical and avoid overconfidence in current methods and practices (Starbuck Citation1996). Finally, the amount of customer interaction, customer pressure, strategic partners, and competitive intensity are all triggers for organizational unlearning (see, e.g., Cegarra-Navarro, Eldridge, and Martinez-Martinez Citation2010; Klammer and Gueldenberg Citation2019).

Unlearning can have both positive and negative consequences (Klammer and Gueldenberg Citation2019). On the one hand, it facilitates learning new information and routines, which can help rejuvenate and renew the organization’s business model and ultimately contribute to better performance and firm survival (Martin de Holan and Phillips Citation2011). By changing organizational mindsets or mental models, organizations reassess the value of their obsolete technologies, helping them in their search for alternatives (Starbuck Citation1996). Unlearning can also assist with other forms of organizational change, technology implementation, and innovation (Becker Citation2008). On the other hand, as it is difficult to separate obsolete and useful knowledge, unlearning may obstruct organizational functioning (Zahra, Abdelgawad, and Tsang Citation2011) and lead to the organization to lose critical knowledge (Yildiz and Fey Citation2010).

Materials and methods

Data collection

To explore cognitive unlearning and its relation to digital business transformation in the context of B2B sales empirically, this study adopted a qualitative and interpretive research design. This design choice was due to the fragmented nature of the study phenomenon. The qualitative interview data for the study were generated between February and June 2020 using online meeting tools (see ). In total, 15 corporate-level (C-level) executives from large enterprises (hereafter dataset A) and 17 senior-level managers (mainly CEOs) from SMEs (hereafter dataset B) were interviewed. These enterprises, most of which operated in the field of information and communication technologies (ICT) and/or offered ICT-related services to other enterprises, were selected as we anticipated that they would provide rich information about digital transformation and unlearning.

Table 2. Summary of the generated interview data.

The interviews were semi-structured, with the focus on the enterprises’ business digitalization, the management of digitalized business operations, and different technologies. We posed direct questions about unlearning in relation to the broader themes presented above. Because most interviewees found it challenging to answer these questions, we also focused on questions such as what kinds of challenges the interviewees had faced with their digital transformation and how they were overcoming them. The interviewees were encouraged to give practical examples to reveal their own processes of unlearning. The interviews lasted approximately 30 to 75 minutes. Thirty interviews were held in Finnish and one in English. Two interviews were group interviews involving two senior-level managers. All the interviews were recorded and resulted in approximately 459 pages of transcript.

Data analysis

Qualitative content analysis (Eriksson and Kovalainen Citation2016) was used to analyze the data. During the analysis and interpretation processes, the generated data were both analyzed separately and progressed together. The separate analysis processes occurred during the first phases of the analysis and interpretation process. The first and third author read the transcripts and marked sentences where the interviewees talked about unlearning and/or learning and described the digital change ensuing in their enterprises. After these separate analysis phases, the analysis process involved several online meetings during which all authors jointly read and discussed the identified themes and their affiliated raw data quotations, as well as progressed the data analysis jointly. The authors also openly discussed the separate coding processes and reconciled interpretations, resonating with the intercoder agreement outlined by Campbell et al. (Citation2013, 297). The cognitive unlearning process and related main themes and subthemes that resulted from the analysis are discussed in the next section.

Findings

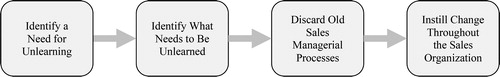

Through our data analysis, we identified a four-phase unlearning process in relation to digital transformation in B2B sales as well as main themes with subthemes for unlearning with respect to each phase (in total 10 critical factors). The four phases comprise identifying a need for unlearning, identifying what needs to be unlearned, discarding old sales managerial processes, and instilling change throughout the sales organization (see ).

Identify a need for unlearning

The first cornerstone in unlearning is identifying a need for it (see, e.g., Tsang and Zahra Citation2008). Our data analyses resulted in the identification of two main themes: 1) questioning one’s own mindset and 2) being receptive to triggers for unlearning. Next, we elaborate on these main themes and their related subthemes.

The first main theme, questioning one’s own mindset, highlights the recognized need to change the organization-wide mindset of sales and selling activities in the digital era. It relates to sales leaders’ and managers’ reawakening regarding what sales work in the digital era comprises and an understanding of how “in the future, we need to understand what can be digitized and possibly automated […] thus, what parts of the selling are worth doing” (B3).

Previous literature has observed that crises usually play a key role in identifying a need for unlearning (Klammer and Gueldenberg Citation2019). In our data, the COVID-19 pandemic has forced companies to rapidly rethink and reorganize current selling activities as sellers have been unable to meet their customers in person. The interviewees also reported other major changes in their businesses, such as drastically diminishing returns and resulting reorganization activities, which have boosted unlearning in their enterprises. Our data analysis reveals that a need for unlearning may occur even before the identification of a crisis (see also Morais-Storz and Nguyen Citation2017). In this case, the role of leaders and managers to encourage their own and their workers’ awakening for unlearning is crucial to starting unlearning in an organization. The leaders and managers can artificially create a “burning platform” to encourage their employees to recognize the need for unlearning. This can, however, be challenging for leaders and managers because “you always have some burning platform at your own desk. If you don’t find that [burning platform], then it is really challenging for you to progress the issue. You just marvel and say how we are advancing, but it does move ahead before finding that burning platform to start with” (B10), as one senior manager aptly noted.

Our data also show that quite a few interviewees had not identified challenges or recognized a need to change their current sales process, limiting their detection of the need for unlearning in relation to old-fashioned ways of selling. Leaders and managers can, thus, inhibit unlearning if they are reluctant to notice and accept that current sales and selling processes should be changed with respect to the digital transformation. The interviewees who did not see a need for change shared a belief that their companies’ sales processes will continue to include face-to-face interactions and to require an “ability to be human and understand human interaction, I mean, being empathic and having situational awareness” (A7), despite the ongoing digital transformation. They also described how, for example, “trade shows are still important to us, and the customer meetings are the number one in priority. Moreover, we create all [marketing] paperwork, different brochures […] and samples for customers” (A4B). They also specified how solution selling activities were run by “doctors of science having a coffee together, I mean, two highly educated experts pondering an issue” (A8).

The second main theme, being receptive to triggers for unlearning, relates to managers’ readiness for change. Previous literature has argued that individuals need to understand that change is required and worth investing in (Becker Citation2010); as one interviewee observed, “you have to understand the benefits these [digitalization] changes bring to your business and what it means if you don’t do them […] I mean, that kind of an understanding, articulating benefits in manners that they don’t sound difficult” (B2). Hence, the managers’ ability to be receptive and motivated (“you need to be curious, I mean as an enterprise but also personally, because the pace of change in these business models and in our business is so remarkable” [B12]) and to maintain a vision for the digital change in their organizations are, according to our data analysis, fertile foundations for unlearning. These abilities assist managers in challenging existing interpretations and assumptions (see also Cegarra-Navarro and Wensley Citation2019) and making sense of their knowledge shortages regarding digital transformation. Some interviewees also emphasized how rethinking organizational identity can trigger readiness for change: “We want to be a technology company and platform company and not an operator” (B7).

Allowing sales personnel time and other resources to scrutinize alternative interpretations of the digital transformation internally can, however, be challenging if the company has no track record of handling digital transformation in sales. Some interviewees reported that their sales strategies and practices needed updating, but they lacked concrete solutions to enact change. One C-level executive, however, reflected on production as an exemplary case of a successful digitalization project and compared it to sales and marketing processes that she was experiencing as constantly dropping behind other digitalized business processes. This type of reflection acted as fertile ground for her to recognize the need for unlearning in sales and selling activities.

In addition to the internal triggers for unlearning mentioned above, we identified several external triggers. First, many C-level executives anticipated that customers familiar with digital selling and buying processes would enable their organizations to identify irrelevant parts of selling processes. Such customers already know how to search for information and create value without sales organizations, which may, for example, reduce the needs for personal selling efforts and cold calling in an organization. Unlearning may also be triggered when enterprises interact with their customers in purchasing processes, as was particularly evident among the interviewed SME managers. The managers noticed that customers need a more profound understanding of what digitalization can offer them as “our customers don’t know how to buy that [the enterprise’s solution] from online stores” (B7) and “we also would like to brand ourselves with that ‘artificial intelligence tag,’ but […] most customers don’t want to purchase that [AI]” (B16). The disruptive nature of their solutions thus boosted the managers to reflect on their ways of selling and how to increase their customers’ “digital maturity,” as one senior manager called it, to ease buying processes and the use of their services.

New selling technologies and industry benchmarks can also facilitate recognizing the need for unlearning in situations, such as when in-person sales decline; as one interviewee stated “customer transactions come in numbers, and incoming euros are not much, it doesn’t bear the costs of the personal selling that we had previously allocated to it” (A3). Another interviewee highlighted change prompted by growth, saying that as the “company grows and develops, it requires constant organizational change […] operating in a highly developing branch of industry […] creating a combination of growth and industry change, it brings us the constant necessity to question operations and move them to a next level” (A6).

Finally, major trends within and alongside digital transformation may prompt the need for unlearning. Some interviewed senior managers’ told us for example how their enterprises’ customers and device manufacturers are approached the ways “they are used to be” (B11) or how the utilization of data is a natural continuum of what they were previously doing: “first we create tools for our own use, and then we offer them to our customers” (B15). However, others informed us about larger recognized changes in their business environments, such as blurring boundaries between the B2B and business-to-customer (B2C) sectors, which assists in detecting the need for unlearning.

Identify what needs to be unlearned

After recognizing the need for it, the next critical phase in the unlearning process is being able to identify key issues that require unlearning (see, e.g., Cegarra-Navarro and Rodrigo-Moya Citation2005). We determined two main themes in this identification process: 1) critically analyzing one’s current sales process (phases and contents) and 2) analyzing one’s ways of thinking and current knowledge sources in sales. These themes, as well as several subthemes, elucidate what executives and managers in our dataset underline as the key issues requiring unlearning in the digital transformation of B2B sales.

The first main theme, critically analyzing the current sales process (phases and content), concerns how managers make sense of the “warning signals” in their enterprises’ existing sales processes in the emerging digital era. Interestingly, many C-level executives had trouble picturing concretely what needed to be unlearned or changed. They had, however, noticed shifting (and increasingly complex) customer expectations and how digital channels and/or automated processes could deliver value during the customers’ buying path and ease after-sales service processes. The executives pointed out some phases of the selling process, especially the prospecting phase, which could benefit from investment in and use of sales technologies and tools.

Intertwining closely with an understanding of customers’ buying behaviors in the digital era, the executives told us that their customers are ready to self-serve with the help of digital content and sales technologies; as one interviewee noted, “we have had a half-dozen customers that we have not ever seen […] we have closed deals […] these kinds of phases changing the world like corona pandemic will advance also digital selling channels and the demand for digital services” (B7). However, this increase in customers’ readiness to purchase online, assisted by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, has exposed sellers who need to find new ways to interact with customers and develop sales remotely.

Besides questioning the cost effectiveness of the enterprises’ sales activities, the interviewees told us how they recognized the need to digitize sales processes but that the “actual problem” lay in the mindsets of salespeople who were not ready for the digital transformation. Some interviewees described how salespeople have been educated to serve their customers in person rather than digitally. The interviewees realized that the sellers needed to rethink their understanding of sales work and critically consider their activities during the sales process: “They [salespeople] need to showcase to their customers the new ways to do business, for example, in digital settings or via customer service […] It is a huge change in a sales person’s daily activities” (A3).

The data analysis shows that an important target for unlearning is changing customers’ ways of thinking and acting (see also Cegarra-Navarro and Wensley Citation2019). While understanding that their enterprises’ services/products needed to be purchased and accessed digitally by customers, the interviewees operating in the SMEs, in particular, noted that their customers did not know how to buy (and use) the enterprises’ offerings. They described, however, how ready-made solutions would encourage buying activities as “customers hunger for these services. They may not necessarily know how to buy them yet from our type of actors, so we need a packaged solution, which is easy to sell and easy to buy” (B3). Others noted that they were already providing easy-to-use solutions to their customers: “Persons who can use computers can use our services” (B9). One senior manager told us how the enterprise is only focusing on companies ready to make a purchase: “If the firm says, ‘I have a data strategy to be presented to the board of directors next year,’ there is no point for us to spend a second with them right now” (B5).

The second main theme, analyzing one’s ways of thinking and current knowledge sources in sales, focuses on how managers limit the targets of unlearning regarding selling/sales activities. The interviewees largely reported a lack of knowledge about how different tools and technologies could or should be used in sales and selling processes. This was somewhat surprising because many of them seemed to be familiar with several different kinds of digital B2B sales tools and platforms and had either started or been involved with digitization projects. Being aware of alternative technological options could help managers limit the targets of unlearning in sales.

Most interviewees reflected in some way on the important role of data in their businesses and how their enterprises were collecting data from various sources, including customer relationship management (CRM) systems and website visits (regarding prospects and time spent in purchasing activities). At the same time, the interviewees emphasized that they lacked an understanding of how to use that data in sales, for example, to optimize selling activities. Many interviewees recognized that adopting digital selling tools and technologies should facilitate not only increased customers’ awareness but also closing deals and engaging in business development. The technologies could help salespeople receive data-based facts, enabling them to bring value to their daily work, such as by improving interactions with customers.

Additionally, some interviewees stated that various ICT systems are not integrated into the enterprise’s sales organization, limiting efforts for improved customer insight and customer service. For example, the data from industrial Internet of things (IoT) systems, focusing on the use of sold products, may not have been integrated into the company’s CRM systems. In this case, the sales personnel may lack important, real-time information about how their customers are actually using the services/products they sell. Rather, they are forced to develop the business using “old” information collection methods, such as making phone calls, meeting customers in person, and scouting information from systems that may not be regularly updated by other members in their organization.

Discard old sales managerial processes

After identifying the areas that need unlearning, managers should focus on replacing these unwanted ways of knowing and doing (Cegarra-Navarro and Wensley Citation2019). We identified three main themes in this phase of the unlearning process: 1) experimenting for and with customers, 2) circulating, shifting, and/or replacing roles, and 3) caring about individuals and encouraging their commitment. Next, the main themes and their related subthemes are elaborated on.

The first main theme, experimenting for and with customers, relates to managers’ efforts to comprehend how current sales/selling routines should be replaced and how digital tools and technologies should be implemented in salespeople’s daily routines. Experimenting has been argued to serve as an important means for unlearning (Cegarra-Navarro and Wensley Citation2019; Morais-Storz and Nguyen Citation2017). Our data also reinforce the importance of experimentation, even though some interviewees reported lacking an understanding of how to drive the digital change in their sales organizations. They told us, for example, how they are “rehearsing […] not really looking at concrete manners” (A2). Others, however, emphasized how experimentation allows the quick testing of different ideas—“in this digital world, you can test something only with a small sum of money and see if the idea works” (A6)—without a fear of punishment for errors—“we try to stress that mistakes are allowed” (A9).

One way the interviewees described experimenting for customers was through content creation. The sales team, together with a marketing person, started to produce blogs, examining analytics that indicated how the blog postings were drawing followers. Based on the data received, the sales team identified key content suitable for their customers or prospects and started to produce content differently from before. Hence, unlearning can also occur in teams when sellers co-experiment on sales-related issues, such as content creation (see also Cegarra-Navarro and Wensley Citation2019).

Some interviewees emphasized how experimenting with customers can facilitate both the customers’ and their own unlearning as it enables the salesperson to receive feedback from outside their immediate sales organizations and recognize what exact aspects in the sales process could be performed differently. One interviewed C-level executive noted, “we have, for example, brought self-service channels to customers […] while many customers still want to have on-site service […] We have created new roles so that customers’ voices can be seen in our daily activities” (A5).

Many senior managers in SMEs highlighted how an experimental mindset enables collectively the abandonment of an idea that one interviewed senior manager called, somewhat ironically, “a propeller-head case.” To act upon digital transformation, enterprises can no longer “hold an engineering approach that everything should be perfect” (B11) or “be fixed with the thought that we know everything beforehand” (B1). Instead, they should understand that “in the digital world, not all needs to be in upfront use. Instead, you can just jump and see and trust that you will learn along the way” (A6). With this experimental mindset and embracing collaboration, such as by “not building it in a way that all would be enormously homogenous, but […building] it to allow for diversity” (B11), enterprises are also able to, for example, run “these fast [development] sprints, which enable us to test some small things, which could then demonstrate whether they lead [to the desired outcome]” (B2) and “design products on customers’ terms” (B11).

The second main theme, circulating, shifting, and/or replacing roles, concerns managers’ actions to discard old habits in sales/selling activities. Our data analysis shows that managers encourage unlearning by making internal shifts in work positions. Rotations in work positions enable employees to become familiar with others’ perspectives and attitudes and find new ways to act. For example, one senior manager recounted how he had changed the work position of a few senior managers into “a kind of a free pitcher of ideas” (B2). Reasons for the changes, according to the interviewee, were based on the top management’s expectation that these people with deep industry-specific business knowledge and an understanding of the current developments in a specific branch of industry would better grasp market/customers signals by “just sniff[ing] and snoop[ing] around these [new] issues” (B2) than, for example, external consultants.

Our data analysis also indicates that dividing sellers’ core task areas can encourage unlearning. This is closely related to managers’ realization of how changes in enterprises’ offerings challenge existing understandings of how salespeople work. For example, the seller may have sold a single product and be trained to present the product’s unique (and differentiating) properties, with a potential customer being and touching the product. Now, however, the seller is faced with selling a service using digital channels.

This realization has forced managers to find alternative ways to support the daily activities of sellers, a key means of which, according to our analysis, was to divide the sellers’ core task areas between them. One C-level executive described the issue the following way: “We have slowly moved toward a division of labor in which certain guys are focusing more on digital services while the other ones are more equipment side sellers” (A2). The interviewees also told us how the division of salespeople’s tasks corresponded with the recognized (digital) competencies of the sellers and their ability to challenge their own comfort zones. Another way for managers to support discarding unwanted ways of knowing and doing was to create new roles in sales based on, for example, feedback from customers.

The managers also recruited new people to make digital changes in sales due to the recognized need to better understand the digital transformation as they “didn’t really understand [in relation to cloud services] what should be done and, therefore, […] needed new talent to look at it” (A2). The interviewees thus informed us that recruitments were needed (or underway) to facilitate digital transformation effectively in their enterprises. Previous literature has, however, indicated that unlearning existing routines can be difficult if only actors external to the organization are relied on (Tsang and Zahra Citation2008). Our interviewees also faced challenges with the new recruits and noted that finding the right people—“technical or salespeople who can talk business” (B5) or “people who understand the deep technical side of machine learning […] not only a technical understanding but an ability to lead and to talk to the customer” (B8)—was not an easy task. Some interviewees also reported that the new recruits had not succeeded in their task, prompting further reconsideration and action.

The third main theme, caring about individuals and encouraging their commitment, emphasizes the managers’ efforts to pay attention to individuals and increase their commitment regarding the digital transformation in sales. Previous literature has shown that individuals may hold on to negative experiences about previous change processes and should be treated not as mere recipients of change but rather as active agents in change processes (Becker Citation2010).

Our data show that digital transformation in sales requires both systematic and people-oriented activities from the managers, through which the managers can alleviate the negative emotions, such as fears and anxieties, of single sellers and equip them with active agency in the change. The interviewees stressed the importance of systematically inviting employees to participate in the digital transformation taking place in the enterprise and allowing them, together with the managers and leaders, to reconceptualize selling activities and make the transition toward new, digitally-enabled operation models. They also emphasized acknowledging the human aspect of digital transformation; as one interviewee observed, “technology is rarely an absolute value but an enabler and a tool that can boost activities” (A12). Another noted the importance of “minding the individual, of recognizing human issues, I mean, to lead those kinds of things that make me or whoever as a human being to shine and perform better” (A5). The interviewees further emphasized the low hierarchical cultures adopted in their organizations, which enabled attention to individuals as well as the cultivation of individual sellers’ self-organization and initiative.

Instill change throughout the sales organization

The final identified phase regarding the unlearning process is to instill the change throughout the sales organization. Managers must ensure that individual employees unlearn old ways of knowing and doing along with the organization (Klammer and Gueldenberg Citation2019; Hedberg Citation1981). The analysis resulted in the identification of three main themes that correspond with the efforts leaders and managers made to diffuse digital transformation throughout their sales organizations: ensuring a safe atmosphere, acting as examples, and making the digital change visible. These main themes and their related subthemes are next elaborated on.

The first main theme, ensuring a safe atmosphere, emphasizes the importance of acting upon negative emotional aspects involved in the digital transformation (first subtheme) and introducing the change in small steps (second subtheme). The analysis shows that digital transformation is an emotionally laden issue that requires managers to make sense of and cope with anxieties and hopes both individually and organizationally (see also Morais-Storz and Nguyen Citation2017). By ensuring a safe atmosphere in which sellers can share their negative emotions, managers can diminish fears related to the digital transformation that would otherwise hinder the change and unlearning process (see also Becker Citation2010). As one interviewee observed, “You need to make big changes to routines, you need to communicate enough, regularly and regarding the contents so that people feel that they are taken care of in that change process and to avoid opposition” (A7).

Guaranteeing a safe atmosphere also relates to managers’ efforts to steer the digital transformation at staff’s own pace and on their own terms. Our analysis shows that the envisioned digital transformation does not occur overnight. Instead, the interviewees emphasized the importance of synchronizing the change in ways that allow sales staff to disregard irrelevant routines as and when they see fit because of their limited adoption capabilities. This synchronization also allows managers themselves to make sense of the digital change and direct the envisioned digital progression in the organization.

The second main theme, executives as active change agents, recognizes the critical role of leaders and managers in both showing commitment to the envisioned digital transformation (first subtheme) and acting as examples, through their own actions, of the envisioned digital transformation (second subtheme). Regarding the first, the interviewees anticipated, based on previous experiences, that top executive commitment is a crucial step in enabling the digital transformation of sales. However, how this top executive commitment was to be achieved remained, interestingly, somewhat ambiguous among the interviewed senior managers. This ambiguity seemed to derive from the managers’ limited capabilities to market and sell their ideas about the envisioned digital transformation within the organization, by, for example, providing arguments on how it would benefit the organization and employees. Thus, in some enterprises, the managers seized the importance of digital transformation, but this enlightenment had not (yet) reached top management.

The second subtheme, acting as an example, emphasizes the importance of leaders and managers showing their commitment to digital change through concrete actions. The interviewees highlighted what one interviewed senior manager called their “educational work” and reported how much information was needed and the uncertainties that digitalization brought to their daily lives. This “educational work” points to the need for leaders and managers to indicate and follow the envisioned direction and path in concrete ways. As one interviewee described, “the management should, in my view, be adopting and using these new tools and procedures. They can’t demand that the staff should change their ways of working if they don’t demonstrate the change themselves” (A3).

The third main theme, making the change visible, concerns the resiliency of leaders and managers to keep the envisioned digital transformation in their agenda through assertive communication (the first subtheme) and demonstration of its benefits (the second subtheme). Instilling the envisioned digital transformation requires first and foremost that leaders and managers assertively and persistently communicate the importance of the envisioned digital transformation despite potential resistance: “if you force and sanction not using it [CRM], the benefit is not big compared to when that single seller would buy the relief brought by digitalization to her own work and to increase effectivity” (A5). With regard to assertive communication, most C-level executives indicated the importance of quantifying targets in the envisioned digital change processes, emphasizing how measurable targets allow the company to gain better results from digital transformation activities. However, communication through quantification may impede unlearning if the leaders and managers fail to quantify relevant procedures and targets, enabling increased digitalization in sales.

Some interviewees pointed out the importance of demonstrating the benefits of digital change. These benefits should be communicated not only from an organizational perspective, such as increased turnover or profit for the company, but also from an individual seller’s perspective, as well as in ways that enable the effective functioning of sales and marketing staff (which often operate in different functions). For example, while salespeople may initially experience the introduction of advanced selling technologies as exciting and interesting, the actual implementation of these technologies in daily activities and working habits, as mentioned earlier, may require constant communication about their importance and value to individuals.

Discussion

B2B sales operations are currently undergoing a fundamental digital transformation, forcing sales organizations to adopt and use new technologies to improve the cost efficiency and customer-centricity of operations (see, e.g., Ahearne and Rapp Citation2010; Thaichon et al. Citation2018). The digitalization of business has made sales operations central to the whole organization’s agenda. To capitalize on the opportunities provided by digital transformation, enterprises must be able to change their long-held assumptions, routines, and practices—even entire business models. A successful change will require discarding outdated ways of knowing and doing, including, perhaps, the very practices that made enterprises’ successful in the past. The current study has addressed this issue by identifying a four-phase cognitive unlearning process and analyzing key themes and subthemes related to each phase regarding the digital transformation of B2B sales. While unlearning can also occur behaviorally, this study focused on the cognitive perspective because scholars posit that cognitive unlearning is a prerequisite for any behavioral unlearning (Mehrizi and Lashkarbolouki Citation2016). Indeed, sales organizations must first perceive and understand obsolete elements before acting to change them. The cognitive perspective is also interesting since irrelevant past knowledge is often harder to forget than problematic routines, which can be unlearned by simply not enacting them for a while (Tsang Citation2008).

Contextually, we focused on digital transformation occurring in B2B sales. B2B sales management literature has largely focused on the work of salespeople as well as how changes in customer behavior and demands have transformed B2B selling and sales management (see, e.g., Cuevas Citation2018; Sheth and Sharma 2008). Studies have also indicated that digitalization will influence buying and selling in profound ways (see, e.g., Singh et al. Citation2019; Thaichon et al. Citation2018). Businesses are increasingly adopting new sales technologies, establishing digital platforms, and utilizing various social media tools to, for example, scale their costly face-to-face interactions, improve customer experience, and lower overheads. These actions have led sales organizations into situations in which they are facing the challenge of reconfiguring their operations (see, e.g., Marshall et al. Citation2012; Moncrief Citation2017). Empirically, we utilized qualitative interview data generated from 31 executives and senior-level managers (mainly CEOs) operating in different industrial sectors. All interviewees were driving digital business transformations in their enterprises.

The study’s findings (see ) reveal how cognitive unlearning is closely intertwined with making sense of what ideas and assumptions within one’s businesses are becoming obsolete in the context of the digital business transformation in sales and what kind of changes in routines are required. Our analysis shows that cognitive unlearning is a multifaceted issue, highlighting tradeoffs and tensions that need to be made visible to progress with digital transformation in a sales organization and revealing the human side of digital transformation. Next, we reflect on our findings in more detail.

Table 3. Enabling cognitive unlearning in B2B sales: phases, critical factors, and empirical illustrations.

Our study outlines a four-phase cognitive unlearning process for digital transformation of B2B sales and analyzes 10 critical factors for unlearning. The first phase, identifying a need for unlearning, occurs when sales leaders and managers cannot rely on existing organizational beliefs, triggering unlearning (Lant and Mezias Citation1992). Critical factors regarding digital transformation are, in this starting phase, sales executives’ and managers’ abilities to question their own mindsets about sales work and to create initial conditions for unlearning in their organizations. They also need to be receptive to triggers for unlearning that can stem from within their own organizations, such as prior digital project expertise, and outside them, including feedback from customers and other stakeholders.

Currently, many sellers’ routine tasks have been facilitated or removed by advanced sales technologies, dramatically changing the essence of sellers’ work (Syam and Sharma Citation2018). This ideological change in sales also assists the enterprises’ customers in their efforts to comprehend how to use advanced technologies and ever-increasing data in their business processes. However, as this study reveals, many sales executives and managers are unable to fully recognize how digital transformation changes their organizations’ existing sales strategies and models, and sellers’ ways of working. Of course, it may be easier for sales executives and managers to recognize unlearning needs in separate, tactical tasks than in larger organizational elements. As Mehrizi and Lashkarbolouki (Citation2016) have argued, holistic unlearning, such as unlearning one’s business model, is more difficult than unlearning a specific practice.

The second phase, identifying what needs to be unlearned, directs attention to the areas sales executives and managers recognize as requiring unlearning. The study shows that sales executives and managers struggle to understand the key issues requiring unlearning in sales processes (both regarding their phases and contents), as well as how to shift existing ways of thinking and use different knowledge sources in sales. While they are aware of changing customer expectations and buying behaviors, as well as technological alternatives, they are unsure of how a salesperson’s mindset (or their own) should be altered or how to facilitate heterogenous business development using digital technologies and tools, reaching anticipated cost efficiency and improved sales performance. To identify the knowledge and routines that require updating, reconfiguring, or revitalizing (Tsang and Zahra Citation2008; Zhao, Lu, and Wang Citation2013), managers can start by reflecting on and making sense of digital business opportunities.

Furthermore, our study identifies prospecting, awareness generation, business development, and the use of new technologies and tools in both sales processes and sales management as key targets for unlearning. Previous studies have shown that customer interaction, customer pressure, strategic partners, and competitive intensity all trigger unlearning (see, e.g., Cegarra-Navarro, Eldridge, and Martinez-Martinez Citation2010; Klammer and Gueldenberg Citation2019). However, the sales executives’ and managers’ inability to recognize pitfalls in their organizations’ current sales processes and to comprehend the role of data and technologies in these processes may, according to our study, dilute efforts to realize the envisioned digital transformation.

The third phase, discarding old sales managerial processes, focuses on managerial efforts to abandon obsolete sales and selling routines. The study identifies experimentation, job/task circulation, shifts and/or new recruits as important means for sales executives and managers to encourage a new understanding of sales work in the digital era, as well as what phases and practices sales processes should include. New recruits can offer managers possibilities to facilitate organizational unlearning if the “newcomers” are able to challenge existing world views and prevent group thinking (Akgün, Lynn, and Yılmaz Citation2006). However, in our study, the sales executives and managers largely experienced failures in achieving the desired outcomes with recruiting. This observation suggests that the sales organizations maintained deeply rooted elements, such as values and assumptions (see, e.g., Hislop Citation2013) about sales work that hindered unlearning, despite managerial efforts. Therefore, we suggest that sales managers focus on establishing conditions and possibilities for job/task rotations and shifts. In this way, they can also (at least partially) address the third critical factor identified in the study related to discarding old sales managerial processes, namely demonstrating continual care toward the sales personnel and making efforts to give them active agency in the change process. These activities encourage a focus on the human aspect of digital transformation, mitigating, for example, negative emotions related to the digital transformation, which further facilitates unlearning.

Finally, the fourth phase of unlearning, instilling change throughout the sales organization, emphasizes how sales leaders and managers not only discard unwanted understandings, cultural burdens, and ways of doing but also strive to harness continually evolving understandings and routines into their sales organizations. In our data, the critical factors enabling these efforts are ensuring a safe environment, acting as change agents (showing commitment and acting as role models), and making the digital transformation visible (assertive communication and concrete actions to demonstrate the benefits of the digital transformation to a single seller). These findings reinforce the importance of social processes and hierarchies (see, e.g., McKeown Citation2012; Tsang Citation2008) as well as emotions (Klammer and Gueldenberg Citation2019) in unlearning. As stated in the theoretical background, unlearning involves emotional labor (Akgün et al. Citation2007), which is why managers should pay attention to negative emotions (Hislop et al. Citation2014) and create a psychologically safe and supportive environment (Brook et al. Citation2016; Visser Citation2017). The findings also echo previous studies that argue for a (psychologically) safe and supportive environment for unlearning to occur (Brook et al. Citation2016; Visser Citation2017).

Conclusions

This article has addressed the topical and important issue of how B2B sales operations are critically changing due to major disruptions brought about by the digitalization of businesses. Focusing on cognitive unlearning in relation to the digital transformation of B2B sales from a managerial perspective, the article makes three key contributions.

First, the article introduces the concept of unlearning with respect to digital business transformation in B2B sales. Previous B2B sales management studies have provided valuable insights on the digital transformation, such as the role of advanced technologies and digital tools in future sales and selling activities, as well as changes in sales categorization and strategy (see, e.g., Cuevas Citation2018; Guenzi and Habel Citation2020; Syam and Sharma Citation2018). However, very little research has outlined what sales managers need to do to transform old ways of working into new ones and how these changes relate to sales and selling activities. B2B sales management studies tend to scrutinize managerial issues based on salespeople (see, e.g., Peesker et al. Citation2019; Singh et al. Citation2019). This article introduces unlearning as a useful metaphor for depicting the digital change taking place in sales (Tsang Citation2017) and reveals the four-phase process involved in it. It also emphasizes, with the help of the unlearning concept, the human side of digital transformation.

Second, the article identifies critical factors related to unlearning, responding to the call of prior research (Klammer and Gueldenberg Citation2019; see also Hislop et al. Citation2014; Tsang Citation2008; Yildiz and Fey Citation2010; Mehrizi and Lashkarbolouki Citation2016). Focusing on the identified 10 critical factors (thus key themes and related subthemes) within the identified unlearning process, sales leaders and managers can create the necessary conditions for discarding obsolete knowledge and practices at both individual and organizational levels. However, sales leaders and managers should not directly assume that the unlearning of individuals automatically translates into unlearning at the organizational level. Instead, sales leaders and managers should consider how the sales organization, its individual salespeople, and its customers can jointly unlearn.

Third, the findings reveal tensions between the individual and organization in relation to unlearning. As literature has shown, individuals learn differently from organizations; organizations, in a sense, unlearn through their individuals, which is why scholars recommend that unlearning is analyzed at the individual as well as the organizational level (Becker Citation2008, Citation2010; Klammer and Gueldenberg Citation2019). Unlearning, however, may not extend unproblematically from the individual to the organization or vice versa. Sometimes the organization may be able to discard old routines while some individuals may still hold onto obsolete ways of performing sales. Alternatively, certain individuals can succeed in unlearning while the organization continues business as usual (Klammer and Gueldenberg Citation2019; Hedberg Citation1981). In our data, the managers expressed their frustration regarding the slow progression of digitalization in their sales’ organizations due to tensions between unwilling individuals and slow-changing organizational processes. The sales executives and managers should, therefore, make an effort to mitigate such tensions and are perfectly situated for this task, having both “the big picture” of the enterprise’s businesses and an understanding of sales-related details.

Despite the contributions made in this article, certain limitations need to be addressed, leading to suggestions for future research. First, although we outline a four-phase process of unlearning, our article does not provide answers to questions about how sales organizations unlearn. As a future research prospect, we suggest exploring the processual issues involved in unlearning in the B2B sales context in more detail.

Second, while answering the call of Klammer and Gueldenberg (Citation2019) for more research on the factors that affect unlearning, this study leaves room for further (qualitative and quantitative) studies that focus on the critical factors for unlearning as well as the relationships between different types of knowledge and unlearning.

Third, our study is exploratory in nature, providing a holistic view of cognitive unlearning from the managerialist perspective. Future studies could treat our study as a starting point and provide more insights into cognitive unlearning in sales organizations by utilizing data collected from sales personnel rather than executives and senior managers. Furthermore, future studies could complement this one by adopting a quantitative methodology and examining the identified factors across various organizations.

Finally, the study offers insights for sales executives and managers on how to cultivate unlearning and extend it beyond organizational borders to customers and other relevant stakeholders. They should, however, note that these activities may also raise tensions that can thwart good intentions, although managers are also uniquely positioned to mitigate tensions between individual- and organizational-level unlearning. Nonetheless, we join others in calling for research into unlearning that simultaneously considers individual and organizational levels (Becker Citation2008, Citation2010; Klammer and Gueldenberg Citation2019).

Declaration of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agnihotri, Raj. 2020. “Social Media, Customer Engagement, and Sales Organizations: A Research Agenda.” Industrial Marketing Management 90:291–9. doi: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2020.07.017.

- Ahearne, Michael, and Adam Rapp. 2010. “The Role of Technology at the Interface between Salespeople and Consumers.” Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management 30 (2):111–20. doi: 10.2753/PSS0885-3134300202.

- Akgün, Ali E., John C. Byrne, Gary S. Lynn, and Halit Keskin. 2007. “Organizational Unlearning as Changes in Beliefs and Routines in Organizations.” Journal of Organizational Change Management 20 (6):794–812. doi: 10.1108/09534810710831028.

- Akgün, Ali E., Gary S. Lynn, and Cengiz Yılmaz. 2006. “Learning Process in New Product Development Teams and Effects on Product Success: A Socio-Cognitive Perspective.” Industrial Marketing Management 35 (2):210–24. doi: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2005.02.005.

- Bages-Amat, Arnau, Liz Harrison, Dennis Spillecke, and Jennifer Stanley. 2020. “These Eight Charts Show How COVID-19 Has Changed B2B Sales Forever.” McKinsey. Accessed April 19, 2021. https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/marketing-and-sales/our-insights/these-eight-charts-show-how-covid-19-has-changed-b2b-sales-forever.

- Becker, Karen. 2008. “Unlearning as a Driver of Sustainable Change and Innovation: Three Australian Case Studies.” International Journal of Technology Management 42 (1–2):89–106. doi: 10.1504/IJTM.2008.018062.

- Becker, Karen. 2010. “Facilitating Unlearning during Implementation of New Technology.” Management 23 (3):251–68.

- Bettis, Richard A., and Coimbatore K. Prahalad. 1995. “The Dominant Logic: Retrospective and Extension.” Strategic Management Journal 16 (1):5–14. doi: 10.1002/smj.4250160104.

- Brook, Cheryl, Mike Pedler, Christine Abbott, and John Burgoyne. 2016. “On Stopping Doing Those Things That Are Not Getting Us to Where We Want to Be: Unlearning, Wicked Problems and Critical Action Learning.” Human Relations 69 (2):369–89. doi: 10.1177/0018726715586243.

- Campbell, John, L. Quincy, Charles Jordan Osserman, and Ove K. Pedersen. 2013. “Coding in-Depth Semistructured Interviews: Problems of Unitization and Intercoder Reliability and Agreement.” Sociological Methods & Research 42 (3):294–320. doi: 10.1177/0049124113500475.

- Cegarra‐Navarro, Juan G., and Beatriz Rodrigo‐Moya. 2005. “Learning Facilitating Factors of Teamwork on Intellectual Capital Creation.” Knowledge and Process Management 12 (1):32–42.

- Cegarra-Navarro, Juan G., Stephen Eldridge, and Aurora Martinez-Martinez. 2010. “Managing Environmental Knowledge through Unlearning in Spanish Hospitality Companies.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 30 (2):249–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2009.11.009.

- Cegarra-Navarro, Juan G., and Anthony Wensley. 2019. “Promoting Intentional Unlearning through an Unlearning Cycle.” Journal of Organizational Change Management 32 (1):67–79. doi: 10.1108/JOCM-04-2018-0107.

- Chuang, Shu-Hui. 2020. “Co-Creating Social Media Agility to Build Strong Customer-Firm Relationships.” Industrial Marketing Management 84 (1):202–11. doi: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2019.06.012.

- Cuevas, Javier Marcos. 2018. “The Transformation of Professional Selling: Implications for Leading the Modern Sales Organization.” Industrial Marketing Management 69:198–208.

- Cusumano, Michael A., Annabelle Gawer, and David B. Yoffie. 2019. The Business of Platforms: Strategy in the Age of Digital Competition, Innovation, and Power. New York: Harper Business.