?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Self-managed teams are becoming more prevalent in sales. In such teams, leadership emergence plays a key role, as leaders are often not explicitly appointed but take on leadership implicitly. Previous research has focused primarily on antecedents that predict leadership emergence, paying less attention to conditions under which leadership emergence positively or negatively affects outcomes. Given the high demands placed on sales teams, understanding leadership emergence and its outcomes in the team selling context is of great importance. Using data from 185 sales team members of a business-to-business company, the authors present a conceptual framework that draws on the job demands-resources model. Results show a direct positive effect of salespeople’s individual perceptions of leadership emergence on perceived team sales performance. This effect depends heavily on perceived customer demandingness and competitive intensity. The strong practical relevance of leadership emergence in sales teams has important managerial implications.

In today’s corporate world, teamwork is omnipresent (Rapp and Rapp Citation2023), with approximately 94% of all organizations working in teams to function effectively (Burke, DiazGranados, and Salas Citation2011; DiazGranados et al. Citation2008; Friess et al. Citation2023). While the traditional view of teams in a corporate environment often involves an explicit leader with formally mandated authority, an imposing majority of 68% of Fortune 500 companies now operate with self-managed teams (Boiney Citation2001; Burke, DiazGranados, and Salas Citation2011), which ‘are widely used as an organizational response to increasing job demands and competition’ (Hu et al. Citation2019, p. 1369). When no explicit leader is present, such teams tend to organize themselves, leading to the emergence of so-called implicit leaders (Day, Gronn, and Salas Citation2004). This phenomenon is particularly important in the sales context. While many B2B companies work in sales teams to address the buying center’s participants individually (Moon and Armstrong Citation1994), they rarely appoint explicit leaders because of their team’s self-organized and cross-functional nature. However, salespeople need guidance as they face unprecedented changes (Alavi, Ehlig and Habel Citation2022) fueled by increased customer expectations and heightened competition (Friess et al. Citation2023; Rapp and Rapp Citation2023). Due to the unique nature of their role as liaisons between buying and selling centers and the associated tendency to step up into implicit leadership roles, they are confronted with much complexity, as well as associated uncertainty in achieving goals (Day, Gronn, and Salas Citation2004; Morgeson, DeRue, and Karam Citation2010). In this context, important research and managerial issues can arise, such as whether the emergence of implicit leaders is beneficial or under what conditions implicit leadership may be advantageous or even harmful.

This study defines individual perceptions of leadership emergence (IPLE) as the perceptual extent to which individual sales team members identify an individual without any formal authority as leading the team (Lee and Farh Citation2019; Schneier and Goktepe Citation1983; Taggar, Hackew, and Saha Citation1999). Numerous studies have investigated leadership emergence (LE) and are summarized by several meta-analyses (e.g. Badura et al. Citation2018; Ensari et al. Citation2011; Hanna et al. Citation2021). However, research has focused primarily on antecedents of LE and thus has not addressed how LE might affect sales outcomes and under what conditions this effect may be strengthened or weakened. Most research has ‘focused on antecedents without including organizationally relevant outcomes. This has led to an unwarranted assumption that emergent leadership is uniformly positive […]’ (Hanna et al. Citation2021, p. 89). Addressing the repeated calls for further research on this subject (DeRue and Ashford Citation2010; Hanna et al. Citation2021; Morgeson, DeRue, and Karam Citation2010; Wellman 2017), our study is based on the assumption that IPLE may have a particularly positive effect on perceived team sales performance (PTSP) when it is genuinely needed and provides benefits to the team. This is exemplified when the implicit leader effectively cultivates an environment fostering psychological safety among team members by alleviating work-related uncertainty (Baer and Frese Citation2003; Fransen, McEwan, and Sarkar Citation2020). However, IPLE may not uniformly increase PTSP, because under some conditions it is likely to be less relevant (House and Baetz Citation1979; Lee and Schuler Citation1980) and could even be a source of relational conflict (De Dreu and Weingart Citation2003; DeRue and Ashford Citation2010). One noteworthy ‘dark side’ of LE, which was evident in the company where we conducted the study, is the emergence of power struggles among team members. Those who exert influence, albeit implicitly, can face resistance from others who question the legitimacy of their authority. This internal tension can result in decreased collaboration, hindered communication, and a sense of unease within the team. Moreover, it has been shown in practice that the implicit leaders can inadvertently contribute to feelings of inequity among their peers. Team members may begin to perceive disparities in recognition, rewards, and opportunities, leading to a decline in overall team morale. This example highlights the potential pitfalls of LE, as it can inadvertently create a hierarchical structure within the team, even in the absence of formal leadership positions.

A closer look at sales and marketing research shows that the majority of studies has focused on explicit leadership issues, such as leadership styles (Dubinsky et al. Citation1995; Friess et al. Citation2023; MacKenzie, Podsakoff, and Rich Citation2001; Shannahan, Bush, and Shannahan Citation2013) or the sales manager–salesperson dyad (Martin and Bush Citation2006). To date, to the best of our knowledge no study has examined IPLE in the sales context and its impact on outcomes. We therefore address this research gap and examine leadership emergence from the perspective of an individual salesperson. In an ad hoc project team, which typically forms spontaneously for a specific task or project, a salesperson might notice the emergence of a leader among the group dynamics. It’s important to note that ad hoc project teams differ from formal teams in that they lack predetermined structures or assigned leadership roles. We aim to answer the important questions of how IPLE affects the sales team’s perceived performance and why and how this effect may change under specific work conditions.

In line with prior research, we measure IPLE as the extent to which team members perceive a person without any formal authority as leading the team (Lee and Farh Citation2019; Schneier and Goktepe Citation1983; Taggar, Hackew, and Saha Citation1999). In the following, this person is referred to as an ‘implicit leader’, which is a clear distinction from an ‘explicit leader’, which holds formal authority. We develop a conceptual framework that builds on the job demands-resources (JD-R) model (Demerouti et al. Citation2001) to explain the effects of IPLE from a team member’s perspective.

This study’s presentation of LE as an individual perception is in line with the JD-R model. The JD-R model focuses on employees’ perceptions of their work environment and proposes that working conditions are categorized as either job demands or job resources. Job resources are ‘[…] physical, psychological, social or organizational aspects of the job that may do any of the following: (a) be functional in achieving work goals, (b) reduce job demands and the associated physiological or psychological costs; (c) stimulate personal growth and development’ (Demerouti et al. Citation2001, p. 501). IPLE can represent a job resource because implicit leaders are likely to absorb pressure and provide guidance for the team. Thus, they help to achieve team goals and reduce job demands for the individual team members. Job demands are ‘those physical, social, or organizational aspects of the job that require sustained physical or mental effort and are therefore associated with certain physiological and psychological costs (e.g. exhaustion)’ (Demerouti et al. Citation2001, p. 501). When job resources can no longer adequately compensate for job demands, in the long-term employees withdraw from the company. Since we want to investigate how IPLE can compensate the increasing demands in a selling context, the JD-R model provides an adequate theoretical framework for our study.

We test the hypotheses of our conceptual framework by drawing on survey data from 185 sales team members of a B2B company from the industrial sector. The teams of at least two and at most six salespeople work together regularly. Additionally, we conduct robustness checks and interviews with six salespeople to validate our results.

Our results show a direct positive effect of IPLE on PTSP. Importantly, in accordance with our proposition we find that this direct effect depends on conditions that exert strong pressure on salespeople: when salespeople perceive increasing customer demands, IPLE positively affect PTSP. In contrast to our proposition, increasing competitive intensity (CI) diminishes the positive effect of IPLE on PTSP. We explain this finding post-hoc by the limited ability of an implicit leader to positively affect PTSP owing to lack of power to use countermeasures against strong competitors.

Our results are highly relevant for practitioners, as businesses place heavy demands on salespeople (Macdonald, Kleinaltenkamp and Wilson Citation2016; Salonen et al. Citation2021). Leaders are likely to absorb the pressure and provide guidance that the sales team urgently needs when uncertainty increases (Conger Citation1999; Lord et al. Citation2017). IPLE especially benefit the team if the context and the situation allow the team to draw on leadership as a resource against increasing job demands. Our study provides valuable insights for managers aiming to foster effective leadership within their sales teams. Instead of focusing solely on enabling individual leaders directly, our findings suggest that companies can benefit significantly by creating environments that support the factors leading to leadership emergence. Previous research highlights the importance of shared vision, collaboration, and supportive team climates as facilitators of LE (Taggar, Hackew, and Saha Citation1999). Managers can strategically implement organizational practices that cultivate these conditions.

Literature review

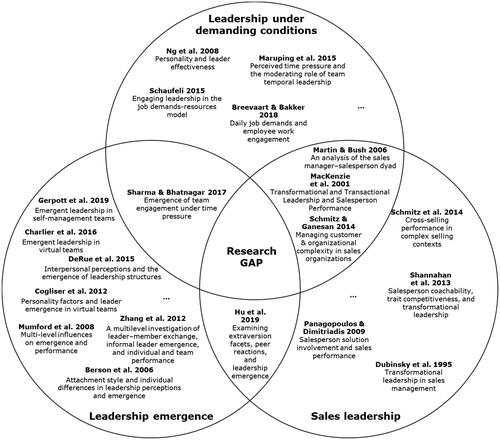

This paper brings together three important streams of literature: (1) research on LE, (2) examination of sales leadership, and (3) studies of leadership under demanding conditions. As shown in our literature overview (), each stream of literature is broadly researched in its own respect but has not yet been sufficiently investigated in combination with the others, producing a research gap which this study addresses.

Research on leadership emergence and its challenges

Research on LE has suffered from great limitations. In 35 published studies, over 70% primarily address predictors of LE (e.g. Badura et al. Citation2018; Ensari et al. Citation2011; Hanna et al. Citation2021). Surprisingly, only about 20% consider moderators and less than 10% include outcomes of LE, demonstrating a clear imbalance in the research focus.

After a profound review of studies on LE we contend that at most, five studies come close to being relevant to this paper (Charlier et al. Citation2016; Cogliser et al. Citation2012; DeRue, Nahrgang, and Ashford Citation2015; Hu et al. Citation2019; Zhang, Waldman, and Wang Citation2012). As shown in however, none of these studies focuses on the sales or on contingencies and performance outcomes in a corporate environment. In summary, while findings of these studies reveal some circumstances under which leadership emerges and, to some extent, the influence it has on performance, they do not expose various contextual factors and their positive or negative influence on the relationship between LE and performance outcomes.

Table 1. Selected studies on leadership emergence.

The role of leadership in sales management research

Research has widely studied the role of leadership in marketing and sales. While general leadership studies have predominantly focused on leaders’ traits (e.g. Lord, Vader and Alliger 1986), situational leadership (e.g. Peters, Hartke and Pohlmann 1985), and leadership styles (e.g. Judge and Piccolo Citation2004), marketing and sales research has focused mostly on leadership styles. This research has evolved from an early emphasis on transactional leadership (Becherer, Morgan, and Richard Citation1982; Jaworski and Kohli Citation1991; Kohli Citation1985, Citation1989; Teas, Wacker, and Hughes Citation1979) to a more contemporary concentration on transformational leadership (Dubinsky et al. Citation1995; MacKenzie, Podsakoff, and Rich Citation2001; Panagopoulos and Dimitriadis Citation2009; Schmitz, Lee, and Lilien Citation2014; Shannahan, Bush, and Shannahan Citation2013). Prior research shows that transformational leadership likely increases salespeople’s performance (Panagopoulos and Dimitriadis Citation2009) or can even outperform transactional leadership in the selling context (MacKenzie, Podsakoff, and Rich Citation2001). In conclusion, sales researchers and managers know very little about IPLE and its effects on outcomes in the team selling context. No study to date has answered the relevant questions: whether the individual perceptions of emergence of implicit leaders are beneficial or harmful in sales teams, under what conditions this effect may change, and which approaches firms can take to actively manage IPLE. We address this relevant research gap with our investigation.

Research on leadership under demanding conditions

Recent leadership studies focus almost completely on explicit leadership under demanding conditions while virtually ignoring implicit leadership (e.g. Breevaart and Bakker Citation2018; Maruping et al. Citation2015; Ng, Ang, and Chan Citation2008). Studies in sales leadership research also focus on explicit leadership under demanding conditions (Alavi, Ehlig, and Habel Citation2022; Friess et al. Citation2023; Hartmann and Lussier Citation2020). The relevance of these studies to our investigation should be questioned due to potential differences in team dynamics when implicit leaders emerge. Conflict may be more likely and perilous for the team for two reasons. First, conflicts can originate from confusion over leader and follower identities (DeRue and Ashford Citation2010). If the leader lacks formal appointment and authority, some team members may not recognize or accept him or her. Second, serious power struggles between team members and leaders could occur (De Dreu and Weingart Citation2003).

The inclusion of leadership under demanding conditions is important for several reasons in the context of researching IPLE in the B2B sector and its impact on PTSP. In B2B sales, teams often operate in dynamic and demanding conditions due to factors such as intense market competition, evolving customer needs, and complex sales processes. Including leadership under demanding conditions acknowledges the practical relevance of the research to the challenges faced by sales teams. Furthermore, effective leadership is contingent upon the specific context (Fiedler Citation1964). By exploring LE under demanding conditions, our research can contribute to a theoretical understanding of how leadership dynamics vary based on situational factors.

Hence, leadership research fails to sufficiently explain the performance impact of IPLE in demanding situations. In summary, the absence of research on LE under demanding conditions and the current state of knowledge on sales leadership in sales management research underscore the need for a study that brings together these streams of research, addressing this research gap and contributing new knowledge to the field. As can be seen in , none of the studies to date have considered all three research streams with B2B data being examined in the team selling context considering different moderators and outcomes. By combining the three streams, our research aims to provide a more holistic understanding of leadership dynamics. It acknowledges that leadership in sales is not only about the individual traits of leaders but also about how leaders emerge in demanding conditions within a sales context. Sales leadership plays a crucial role in driving team performance (Mehra et al. Citation2006), and this impact is magnified in demanding conditions (Wang, Waldman, and Zhang Citation2014). Understanding how leadership emerges in such conditions can offer practical insights for sales managers. Contemporary business environments are characterized by constant change, complexity, and high demands on sales teams. Research at the intersection of these streams addresses the needs of managers operating in such environments. It provides actionable insights into effective leadership strategies for maximizing team performance, as well as insights into potential dark sides of LE.

In summary, conducting research at the intersection of LE, sales leadership, and leadership under demanding conditions is relevant because it offers a comprehensive understanding, has practical implications for sales management, fills a gap in the literature, enhances theoretical frameworks, addresses contemporary business challenges, and has the potential to drive innovation in leadership practices.

Theoretical background and conceptual framework

In a self-managed environment with no explicit leader, teams tend to organize themselves, leading to the emergence of implicit leaders (Day, Gronn, and Salas Citation2004). In identifying situations wherein LE is paramount, we draw on the JD-R model (Demerouti et al. Citation2001). Leadership is crucial in situations with high job demands, as it serves as an important resource for salespeople (Alavi, Ehlig and Habel Citation2022). Since sales teams face high demands from customers and competitors (Rapp and Rapp Citation2023; Ulaga and Loveland Citation2014), they are likely to perceive such conditions as job demands that generate psychological costs (Demerouti et al. Citation2001). ‘Business markets are characterized by fundamental shifts, related to sales strategies, technologies, and customer expectations, all of which impose notable pressures on B2B firms […]’ (Salonen et al. Citation2021, p. 141).

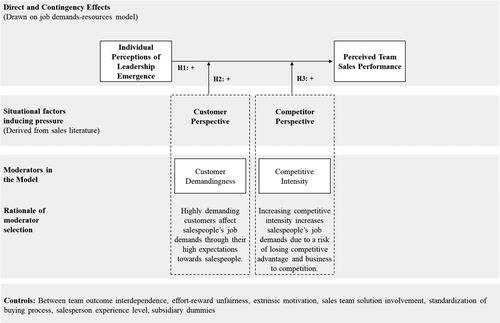

The moderator selection framework () shows which job demands should be considered when examining the effects of LE. Leaders are likely to absorb pressure and provide guidance that the team urgently needs (Conger Citation1999; Lord et al. Citation2017). That is, when salespeople are exposed to situational pressure, they are likely to be more receptive to LE because leaders’ imposition of structure clarifies roles, sets goals, and defines steps to reach these goals (Lee and Schuler Citation1980) actions that can reduce uncertainty. Hence, to study situations in a selling context, where LE may work particularly well, we include in our model moderators that are likely to be perceived as job demands. To reflect the prevailing pressure conditions of salespeople, our moderators take the customer and the competitor perspective.

From the customer’s perspective, customer demandingness (CD) (Wang and Netemeyer 2002) is a highly relevant moderator. Highly demanding customers increase pressure on salespeople due to their high expectations of quality, support and satisfaction of individual needs (Bonney and Williams Citation2009; Jaramillo, Mulki, and Boles Citation2013). We therefore assume such conditions are perceived as job demands and salespeople are likely to perceive LE as a supporting element in terms of a job resource.

From a competitor’s standpoint, we include CI (Chan et al. Citation2012; Jaworski and Kohli Citation1993) as a relevant moderator because salespeople can perceive strong competition as a job demand. We propose that with increasing competitiveness, pressure on salespeople intensifies, because the competitive advantage of a supplier’s product and solution portfolio is at risk and the possibility of a competitor takeover of individual customer relationships strengthens (Auh and Menguc Citation2005; Homburg, Müller, and Klarmann Citation2011). We propose that under such conditions, IPLE can be an important job resource for salespeople, as they might trust the leader to organize winning actions against a strong competitor.

In conclusion, the extent to which IPLE affect PTSP should strongly depend on these contingencies. For our conceptual framework, we initially focus on the direct relationship between IPLE and PTSP (). We also include moderators that reflect the increasing demands and high-pressure conditions of frontline employees. In the following, we derive the hypothesis for a direct effect of individual perceptions LE on PTSP and then elaborate on how contingencies influence these effects.

Research hypotheses

Individual perceptions of leadership emergence and perceived team sales performance

IPLE should increase PTSP. Salespeople should perceive emerging leaders as a valuable resource and source of support in their work. Implicit leaders can absorb pressure and provide guidance to the team, and thus salespeople should perceive such leadership as a job resource. In what follows, we ground this line of thought in previous research.

When salespeople perceive emergent leaders, they can perceive such leaders to initiate structure by clarifying roles, setting goals, and defining steps to reach these goals (Lee and Schuler Citation1980). Hence, a leader’s initiation of structure can reduce uncertainty within the team because team members gain a better understanding of the steps needed to reach a goal and their individual contribution to the team’s success. When uncertainty can be reduced by leaders and team members feel less work-related insecurity, team members experience psychological safety (Edmonson Citation2004). Previous research has shown that teams of individuals with high levels of work-related psychological safety develop high levels of team identification, which can be an important predictor of team performance (Johnson and Avolio Citation2019). Moreover, studies show a positive relationship between performance and psychological safety resulting from implicit team leadership (Baer and Frese Citation2003; Fransen, McEwan, and Sarkar Citation2020). Hence, the individual perception of emergence of implicit team leadership is likely to be an important job resource to achieve a high PTSP.

However, some findings in previous research on LE raise doubts about this rationale. IPLE may be also a source of conflict since leaders implicitly exert power over their peers. When leaders are perceived to emerge in self-managed teams, ‘confusion and conflict over leader and follower identities [may] emerge, thereby resulting in less clarity’ in the team (DeRue and Ashford Citation2010, p. 635). In such a situation, salespeople could perceive LE as a job demand.

Importantly, this argument may not be applicable in the selling context for two reasons. First, teamwork and interdependence are crucial to satisfy customer needs in sales (Perry, Pearce, and Sims Citation1999). Individuals are likely to perceive a benefit and thus a job resource from working in self-organized teams that are managed by implicit leaders. Prior research shows that when individuals derive benefits from their team membership, team identification and effectiveness are strengthened (Perry, Pearce, and Sims Citation1999; Van Knippenberg, Haslam, and Platow Citation2007). Thus, if IPLE benefit team members and promises to increase salespeople’s success, salespeople are likely to perceive leadership as a job resource and identify to a greater extent with the team and its implicit leader (Van Knippenberg, Haslam, and Platow Citation2007).

Second, the information-processing view posits that even when associated with some level of conflict, team members’ different perspectives are advantageous owing to broader knowledge and skills (Mannix and Neale Citation2005). Hence, if the individual perception of LE leads to contrasting views and ideas about work-related issues rather than conflicts about leader and follower identities, conflicts could be beneficial for the team and thus be an important job resource (Levine, Resnick, and Higgins Citation1993; Nonaka and Takeuchi Citation1995).

In sum, IPLE are likely to increase PTSP if LE helps the team to gain structure and orientation. Furthermore, IPLE are likely to positively affect PTSP when salespeople derive benefits from their team membership and when conflicts lead to a better quality of work results. After considering both lines of reasoning, we assume that an individual perception of LE is more likely to be an important job resource and therefore propose:

H1: Salespeople’s individual perceptions of leadership emergence will increase perceived team sales performance.

Contingency factor: Customer demandingness

CD refers to a salesperson’s perception of customers’ high expectations regarding product and service offerings (Wang and Netemeyer Citation2002), which directly translate to increasing customer demands. In situations with high CD, IPLE can be particularly promising as job resources, because they can help salespeople to cope with rising job demands (Demerouti et al. Citation2001). Therefore, when CD is high, IPLE should prove especially relevant and positively influence PTSP. We base this argument on the following considerations.

CD reflects customers’ high expectations of salespeople. More precisely, demanding customers expect high levels of product and service quality and want a perfect match of their needs and salespeople’s offerings (Wang and Netemeyer Citation2002). When customer demands are mounting, salespeople are progressively more dependent on each other’s contribution to create a solution to the customer’s problem. For example, salespeople first need to identify and understand the customer problem and then craft an offering that solves the customer problem and oversee the offering’s successful implementation and maintenance (Alavi et al. Citation2022). Salespeople need to carefully coordinate various resources and departments of their own organization—a responsibility that expands the traditional role of a salesperson beyond the customer-interaction boundaries (Tuli, Kohli, and Bharadwaj Citation2007). In other words, one salesperson alone is unlikely to be able to meet the growing customer demands. High CD increases the demands put on salespeople, because in addition to routine selling tasks, a considerable amount of coordination work is now required to successfully meet the intensifying customer demands.

Under such conditions, the IPLE could play an important role, as prior research shows that leadership is a key factor influencing salespeople’s behavior and success (Boichuk et al. Citation2014; Dubinsky et al. Citation1995; Schmitz and Ganesan Citation2014). We assume that salespeople perceiving LE functions as a job resource in this situation for the following reasons. When customer demands are increasing and salespeople rely on each other to a greater extent, implicit leaders can positively influence the collaboration of the entire sales team. For example, the individual perception of an implicit leader could help to initiate structure, provide orientation, and encourage coordination between team members. Thus, salespeople may perceive the leader as an important resource, relieving the salesperson of the coordination tasks. As a result, when customers are highly demanding and salespeople perceive an implicit leader to emerge within the sales team, salespeople may be more able to focus on their key competences, which in turn should offset the high demand placed on them.

Thus, when customer demands are increasing, IPLE can provide important job resources, helping salespeople to cope with increasing job demands. Therefore, we put forth:

H2: Customer demandingness positively moderates the effect of salespeople’s individual perceptions of leadership emergence on team sales performance.

Contingency factor: Competitive intensity

Our purpose is to test whether CI influences the effect of IPLE on PTSP. We define CI as ‘a situation where competition is fierce due to the number of competitors in the market and the lack of potential opportunities for further growth’ (Auh and Menguc Citation2005, p. 1654).

We argue that an increase in CI expands salespeople’s job demands. We base this argument on the following considerations. First, when competition is fierce, salespeople face pressure to differentiate themselves from the competition so as not to lose business or even entire customer relationships to competition (Homburg, Müller, and Klarmann Citation2011). Since salespeople are highly dependent on their contribution to the company’s success through outcome-based control systems (Anderson and Oliver Citation1987), such losses of business and customer relationships are directly related to their income. This thinking is in line with that of Jaworski and Kohli (Citation1993), who argue that the greater the competition, the more effort salespeople have to put into identifying customer needs and generating superior customer value. Hence, salespeople face swelling job demands resulting from rising CI.

Again, we assume that under such conditions, perceived LE is likely to be perceived as an important job resource. First, when competition is fierce, the leader could help salespeople to cope with competition. For example, the implicit leader might gather and process information from different team members and provide guidance toward a competitive strategy, thus influencing colleagues’ behavior. As noted earlier, previous research has shown that leadership is a key factor influencing salespeople’s behavior and thus their success (Boichuk et al. Citation2014; Dubinsky et al. Citation1995; Schmitz and Ganesan Citation2014). Second, when leaders are perceived to emerge within the team, providing orientation and guidance, salespeople should feel more secure (Davidovitz et al. Citation2007). For example, the perceived leader could offset the imbalance of underestimating the firm’s own service offering and overestimating the offering of the competitor by providing information about the competitor and strengthening the belief in the advantages of the firm’s own service offer. In this context, prior research has shown that when implicit leaders lessen insecurity, performance can be positively affected (Baer and Frese Citation2003; Fransen, McEwan, and Sarkar Citation2020). This effect may be particularly relevant under demanding conditions, where leadership can be perceived as a protective shield (Kerr et al. Citation1974).

In summary, when CI is high, perceived leaders can provide important job resources through their behavior, which helps salespeople to cope with increasing job demands resulting from CI. Consequently, we hypothesize:

H3: Competitive intensity positively moderates the effect of individual perceptions of leadership emergence on perceived team sales performance.

Methodology

Data collection and sample

Context description

We conducted our study in a field setting and collected data in a business-to-business context. All data were acquired from a German globally leading manufacturer of products, systems, and solutions for building services and water management, which employs over 7,500 employees in more than 60 countries. The company generates sales of around €1.5 billion. The portfolio comprises products and solutions for heating, air conditioning, ventilation, cooling, water supply, and wastewater treatment applications based on pump systems, including digital connectivity and respective maintenance services. To enhance the generalizability of our study findings and mitigate the impact of cultural factors or variations in the maturity levels of the company’s sales force and offerings, we collected data from six international subsidiaries. Each subsidiary operates as an independent entity with its own profit and loss responsibility and largely autonomous organizational structures.

The company’s salespeople are responsible for sales opportunity identification, needs evaluation, specification of the right solution, closing of contracts, and commissioning of solutions on the customer side. Salespeople interact with buying centers along the sales process, depending on the current status of their sales opportunities. The sales process can be roughly divided into three phases: pre-sales, sales, and after-sales. In the pre-sales phase, salespeople identify potential building services or water management projects and try to positively influence the planning offices to ensure that their own solution portfolio is the best possible match for the bid. In the sales phase, they work on the published bids and prepare and follow up on a corresponding offer. In this process phase, salespeople influence various stakeholders in the customer’s buying center. This influence may be based on the unique value proposition of a solution or on more commercial reasoning, such as payback on energy costs. Once the price negotiations have been concluded and the contract awarded, the solution is put into operation in the after-sales phase and regularly monitored in the case of a maintenance agreement or serviced in the event of a breakdown. To ensure that salespeople’s responsibilities are accomplished along these process phases, salespeople gather in self-organized teams without formal team leaders.

Data sources and collection procedure

To test our hypotheses empirically, we asked 256 sales team members from six subsidiaries to complete an online questionnaire. Participants were reminded twice, two weeks after the initial mailing and four days before the deadline. We received 185 completed surveys, yielding a response rate of 72.3%. The survey items focused on participants’ work environment and individual competences. Participants provided detailed information on sales team structure and cooperation by naming colleagues they work with most frequently. They identified team leaders who are perceived as such despite lacking explicit appointment. Participants were also queried about various aspects of LE, as well as internal and external factors inducing situational pressure. Sales team questions encompassed solution involvement and team sales performance aspects.

Sample description

On average, the sales teams consisted of 3.5 members, ranging between two and six salespeople. Of the respondents, 77.42% were male, 10.75% were female, and 11.83% did not provide gender information. We show further information on overall sales experience, company tenure, and job position tenure in the web appendix.

Measures and measurement diagnostics

We primarily use well established measures from the marketing literature with adjustments to suit our study’s context. In what follows, we indicate the data sources of our core constructs.

To measure our independent variable IPLE, the items aim to capture respondents’ perceptions in the context of their experiences in project teams. A project team is a temporary group of individuals assembled to achieve a specific goal or complete a particular project. Project teams are characterized by their ad hoc nature, formed for a defined period to address unique tasks, challenges, or objectives. The project teams in the company where we conducted the survey usually form for specific projects that can last from 3 to 12 months. We first asked the responding salespeople to think of the person they perceive as a leader within the team even though the person is not explicitly appointed as a leader. We then measure IPLE with three items from prior studies (Foti and Hauenstein Citation2007; Lord, Foti, and De Vader Citation1984). For instance, the scale to measure IPLE includes the following item: ‘How much leadership does this person have in your team?’ The items are rated on a seven-point Likert scale, with 1 indicating ‘none at all’ and 7 indicating ‘extraordinary’.

Using seven-point Likert scales established in the literature, we measured our two moderators, CD (Wang and Netemeyer Citation2002) and CI (Chan et al. Citation2012; Jaworski and Kohli Citation1993). To measure CD, we use four items, such as ‘Our customers have high expectations in terms of service and support’. To measure CI, we use three items, such as ‘Competition in our market is fierce.’ The salespeople who participated in our survey operate within different subsidiaries that are in different countries. By working in different countries, they are exposed to distinct market conditions, customer demands, and competitive landscapes. Hence, the variance on the moderating variables is grounded in the tangible differences in the environments in which these sales teams operate.

We based the measurement of our dependent variable PTSP on three items from prior studies (Lambe, Webb, and Ishida Citation2009; Schmitz, Lee, and Lilien Citation2014), such as ‘The results of my team are outstanding’. Again, we adjusted the scales slightly to fit the context of the study. We measure not only IPLE but also PTSP at the task level. We provided explicit instructions to respondents, asking them to ‘please relate the following responses to your current project and the associated tasks’. This approach aims to capture the nuanced and context-specific nature of emergent leadership within adhoc project teams.

Appendix A lists the sources and the operationalization of all measurement scales of our core constructs as well as the control variables used within our study. The reasoning for the selection of the control variables follows in the next section (see omitted variable bias section). To assess the appropriateness of not aggregating measures to the team level, we calculated the intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) for the main DV and IV, PTSP and IPLE. The ICC for PTSP is 3.1%, and for IPLE it is 3.7%. These values suggest that a small proportion of the variance is attributable to team-level differences. According to common recommendations, when ICC values are low, observations can be considered relatively independent of each other, and aggregation may not be appropriate. In our case, both ICCs fall within this range (Koo and Li Citation2016), indicating that the observations for PTSP and IPLE are relatively independent, supporting our decision not to aggregate measures at the team level. We also calculated the ICCs for the moderators, perceived CI and CD, resulting in values of 5% and 3% respectively. Low ICC values are common when team sizes are small (Bliese Citation1998), which applies to this study’s average sales team of 3.5 members. Our focus on adhoc project teams, rather than formally established ones, allows a flexible exploration of emerging leaders, given the temporary nature of these teams. However, team members from diverse task environments may lead to leading to varied perspectives on customers and competitors. While their ratings may not strongly align (Beeler, Zablah, and Rapp Citation2022; Dukerich, Golden, and Shortell Citation2002), this diversity allows us to meaningfully examine the effects of leader emergence at the individual level. Individual perceptions are crucial as they influence salespeople’s motivation and reactions to emergent leaders.

We evaluated the reliability and convergent validity of our measurements by examining Cronbach’s alpha and conducting confirmatory factor analyses (Diamantopoulos and Winklhofer Citation2001). As shows, the values for Cronbach’s alpha exceed the threshold of .7 (Nunnally Citation1978). Furthermore, the composite reliabilities (CR) of all constructs are above .78 and below .90 and therefore lie within the recommended values (Bagozzi and Yi Citation1988; Fornell and Larcker Citation1981). The values of all of our multi-item constructs exceed the prescribed thresholds for average variance extracted (AVE) (.5) (Fornell and Larcker Citation1981; Bagozzi and Yi Citation1988). Additionally, all scales meet the Fornell-Larcker criterion. The confirmatory factor analysis indicates a very good fit of the overall measurement model to the data (CFI = .91, TLI = .90, RMSEA = .06, SRMR = .06). Hence, the measurements exhibit adequate reliability as well as discriminant and convergent validity.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics and correlations.

Model specification and identification concerns

To test our hypotheses, we initially specified the following linear model:

where i stands for participants, b denotes regression coefficients, and u is the error term.

We centered all predictor variables on their grand mean before the model estimation in StataSE 15 (StataCorp Citation2017) to reduce potential multicollinearity and facilitate the interpretation of the interaction effects (Hofmann and Gavin Citation1998). We also calculated the variance inflation factors for all variables. Given that all variance inflation factors are well below 5 (), we do not assume multicollinearity to be an issue in our analysis (Belsley, Kuh, and Welsch Citation1980). To evaluate the model fit, we inspected the values for the R2. As indicated by values shown in , the regression model fits the observed data well.

Table 3. Model hypotheses and results.

We estimated three regression models to test our hypotheses. First, we specified a model with main effects only (Model 1 in ). To explore the moderating effects of CD and CI, we added the interaction effects (Model 2 in ). Finally, we specified a model with main effects, interaction effects and control variables (Model 3 in ). In the following, we concentrate on the discussion of Model 3. Importantly, this model might be subject to several concerns that might bias identification of effects. We discuss and mitigate these concerns in the following.

Common method bias

Our measures may be subject to a common method bias because the respondents are the source for the exogenous variable as well as the endogenous variable (Podsakoff et al. Citation2003). However, common method bias is unlikely to have influenced our results for the following reasons. We informed participants that the survey questions had no right or wrong answers. In addition, we assured full anonymity for participants’ answers (e.g. Alavi et al. Citation2018). Furthermore, problems resulting from common method bias tend to decrease within moderation analyses since respondents are unlikely to be guided by a cognitive map that includes interactions which are difficult to visualize, as is the case with moderator analyses (Chang, Van Witteloostuijn, and Eden Citation2010).

Additionally, to verify external validity of the performance measure, we conducted an additional analysis testing the correlation of PTSP with objective-related individual sales performance. We found significant correlations between individual items of PTSP and objective performance data, specifically ‘Salesperson total number of visits’ (β = .30, p < .01) and ‘Salesperson total sales revenue’ (β = .20, p < .10)). These objective data were not integrated into the model, as they were only available for 84 salespeople.

Moreover, we used the marker variable approach for estimating the magnitude of method bias within our study. Therefore, we employed ‘standardization of the buying process’ in the study as a marker variable that is theoretically unrelated to the constructs of interest. The correlations in our data underline this assumption. Specifically, there are no theoretical grounds to assume that standardization of the buying process is related to effort-reward unfairness. We created a new correlation matrix adjusting for this correlation and re-estimated the model on this basis. Since our hypothesized results do not differ between both estimations, we can assume that our results are not strongly subject to a common method bias (Lindell and Brandt Citation2000; Lindell and Whitney Citation2001; Podsakoff et al. Citation2003). The full results of the marker variable approach can be found in the web appendix.

Omitted variable bias

Omitted variable bias occurs when an independent variable correlates with other variables not included in the model that causally affect the dependent variable. As a consequence, the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable can be spuriously significant. To rule out endogeneity through omitted variables, we included control variables derived from prior research (Sande and Ghosh Citation2018).

We control for the individual perception of extrinsic motivation (Oliver and Anderson Citation1994), effort–reward unfairness (Janssen Citation2001) and the subsidiary to which each sales team member belongs and salesperson experience level. Considering the potential variation in sales environments across different subsidiaries, controlling for this variable accounts for contextual differences. A salesperson’s experience could influence their individual perception of LE and how they contribute to team outcomes. Previous research has shown that extrinsic motivation can contribute to performance (Sansone and Harackiewicz Citation2000) and that role stressors such as effort–reward unfairness affect salespeople. Unfairness might introduce complexities that could impact IPLE and PTSP. The prevailing consensus is that effort–reward unfairness is negatively related to job performance (Janssen Citation2001; MacKenzie, Podsakoff, and Ahearne Citation1998). To account for the possible influence of extrinsic motivation and effort–reward unfairness on PTSP and other variables used in our model, we included these factors as a control variable—other predictors—in our model.

Further, we control for between-team outcome interdependence (Van Der Vegt, Emans, and Van De Vliert Citation1998) and sales team solution involvement (Panagopoulos, Rapp, and Ogilvie Citation2017). Previous research has shown that team task characteristics, such as task and goal interdependence and employee involvement, are positively related to team performance (Campion, Medsker, and Higgs Citation1993). Between-team outcome interdependence captures the extent to which team outcomes depend on the performance of other teams. In sales, where collaboration and coordination across teams are crucial, between-team outcome interdependence helps account for the interplay between teams, which could influence both IPLE and PTSP. Acknowledging the complexity of solution selling contexts, this control variable captures the extent of the team’s involvement in solution-based sales. Hence, we control for sales team solution involvement and between-team outcome interdependence.

Moreover, through the subsidiary dummies, we control for idiosyncratic influences of the specific contexts in the subsidiary’s market.

Nonresponse bias

Non-response bias occurs when the characteristics of individuals who do not respond to a survey differ from those who do respond. It can undermine the validity of survey results by skewing the sample composition (Armstrong and Overton Citation1977). To rule out non-response bias as an issue, we conducted an early-late responder test. The results show that the characteristics of the ‘early’ and ‘late’ responders are not significantly different and thus the time at which the participants respond has no influence on their responses. Full results of this additional analysis are shown in the web appendix.

Endogeneity of leadership emergence

Our independent variable—IPLE—may be endogenous as it could be driven by our moderator variables—CD, CI, or other predictors. That is, a team that faces highly demanding customers or strong CI may create an environment in which a leader can step forward and be acknowledged as such. This may lead to IPLE being correlated with the error terms, which would bias the results. To address this concern, we conducted the Durbin-Wu-Hausman test. The test evaluates the consistency of an estimator when compared to an alternative, less efficient estimator that is already known to be consistent (Greene Citation2000). With a p-value of .59 the results show that our IV, IPLE, is not endogenous in our model specification, as we cannot reject the null hypothesis that the unique errors and the regressors in the model are not correlated (Greene Citation2000).

Robustness check

In addition to applying our final model, we followed procedures to preclude the possibility of nonlinear effects of IPLE or the moderator variables and to validate the interaction effects (Ganzach Citation1997). Thus, we added the squared predictor and moderator variables as additional controls into the model. However, none of the coefficients of the squared variables was significant, and all hypothesized effects remained stable.

Results

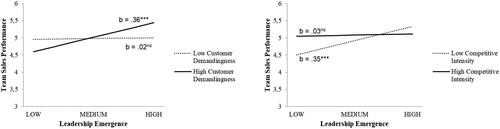

shows the results of all the models. We tested our hypotheses using the full model (Model 3). With regard to H1, the results of our full model reveal that IPLE have a significant positive effect on PTSP (b = .19, SE = .07, p < .05). H2 suggested a positive interaction of IPLE and CD on PTSP. Our results provide tentative support for H2 (b = .18, SE = .10, p < .10). Specifically, inspecting the conditional effects (i.e. simple slopes depicted in ), IPLE increases PTSP more when CD is high (b = .36, SE = .08, p < .01) rather than low (b = .02, SE = .13, p > .10). However, we find no support for our proposition H3 of a positive interaction effect of IPLE and CI on PTSP. Instead, we find that CI negatively moderates the effect of IPLE on PTSP (b = −0.18, SE = .09, p < .05). In particular, IPLE increase PTSP more when CI is low (b = .35, SE = .11, p < .01) rather than high (b = .03, SE = 10, p > .10). We discuss this finding in the following chapter, with displaying the corresponding interaction plots.

Figure 3. Interaction plots.

*p < .10, **p < .05, ***p < .01, n.s. not significant (p > .10) (two-tailed).

Notes: We report unstandardized coefficients. High/low moderator values reflect +/- 1.0 standard deviations from the mean value.

We delved into additional analyses to explore the potential interaction effects of role conflict and effort-reward unfairness on team outcomes in the context of implicit leadership. Please refer to the web appendix for this analysis. Our investigation encompassed two-way interactions with role conflict and effort-reward unfairness, as well as three-way interactions involving IPLE, CD or CI, and either role conflict or effort-reward unfairness.

The outcomes of the supplementary analysis of the two-way interactions with role conflict and effort-reward unfairness affirmed the stability of our main effects, reinforcing the robustness of our primary findings. The three-way interaction of IPLE, CD and effort-reward unfairness is significant and depicted in the web appendix. The empirical findings consistently indicate a positive effect of IPLE when demanding conditions such as high CD or effort-reward unfairness are present. These results intricately align with the tenets of the JD-R theory, wherein the perception of emergence of implicit leadership manifests as a beneficial asset in the face of heightened demands. The discernible positive effects imply that the perception of an implicit leader is advantageous for the team, serving as a strategic resource in navigating challenges and fostering coordinated efforts under demanding conditions. Notably, the absence of discernible demands coincides with the attenuation of the positive effect associated with IPLE. This empirical pattern underscores the contextual sensitivity of leadership dynamics and substantiates the JD-R framework’s applicability in elucidating the nuanced interplay between IPLE and environmental demands. Full results of this additional analysis are shown in the web appendix.

Discussion

The aim of this study is to understand how IPLE affect PTSP and under what conditions this effect may change. In particular, we investigated how situational pressure may influence the effect of IPLE on PTSP. As sales teams face high demands from customers and competitors (Rapp and Rapp Citation2023; Ulaga and Loveland Citation2014), companies and their salespeople are exposed to steadily increasing pressure (Salonen et al. Citation2021). We therefore applied the JD-R model (Demerouti et al. Citation2001) to explain our moderating effects and include into our model moderators that reflect such job demands. Additionally, we conducted an analysis to assess factors that might explain if there are types of teams that management should be aware of that need a leader assigned since it’s less likely that one will emerge naturally. The results of the additional analysis show that in project teams that perceive low emergent leadership, the experience is lower and there is a higher effort-reward unfairness.

The direct positive effect of IPLE on PTSP depends on the situation the team is exposed to. Therefore, it would be inappropriate to use only our direct effect to explain IPLE in the sales context. Although IPLE obviously elevate PTSP, the strength of this effect varies based on salespeople’s perceived job demands and how the implicit leader responds to these demands by providing suitable job resources. Thus, we discuss our two contingency effects and apply our theoretical rationale based on the job JD-R model advanced earlier.

First, with respect to CD we find a positive moderating effect on the relationship between IPLE and PTSP. In line with our reasoning, demanding customers are more challenging for salespeople than less demanding customers. Salespeople need to identify and understand the customer problem, but also create an appropriate offer that solves the customer problem and ensures successful implementation and maintenance (Alavi et al. Citation2022). That is, high CD means that salespeople must carefully coordinate various resources and departments within their own organization to meet the demands. This requirement extends the traditional role of a salesperson beyond the boundaries of customer interaction (Tuli, Kohli, and Bharadwaj Citation2007). Therefore, increased CD results in stronger job demands. In this situation, the perception of an implicit leader can act as a job resource, providing structure, orientation, and coordination for the team to balance the high demands.

Second, the finding that high CI nullifies the positive effect of IPLE on PTSP needs further investigation and discussion. At first glance, this finding is surprising and suggests the rejection of our hypothesis. One possible explanation could be that in highly competitive environments, the emergence of implicit leaders may not provide sufficient job resources to cope with increasing job demands resulting from high CI. High CI requires the ability to react quickly, flexibly, and efficiently to differentiate the firm from the competition and achieve increased profitability (Sanders Jones and Linderman Citation2014). An implicit leader who is perceived to emerge from within the sales team may find such requirements difficult to meet. Although such implicit leaders may have the means to react quickly and flexibly, their authority is likely to be limited or sometimes not appropriately defined, which slows down fast and flexible decision-making processes. That is, depending on the situation, implicit leaders may need to reconcile their decisions with leaders above the line and may therefore be unable to set up actions and job resources sufficient to win against strong competition. Our findings suggest that, when CI is rather low, IPLE is relevant and increasingly suitable to increase PTSP. In this situation, leaders may be more able to provide adequate resources to the team because they can independently decide on their actions since the situation does not require reconciliation with leaders above them. To validate the logic of the effect of CI, we conducted six interviews with salespeople. The results are depicted in .

Table 4. Interviews with salespeople on CI moderation.

While both factors introduce challenges and heightened expectations for sales teams, the underlying dynamics and implications for emergent leadership vary. CI introduces challenges that primarily arise from external market forces, industry dynamics, and the actions of competitors. The pressures from heightened competition may require sales teams to adapt quickly, focus on differentiation strategies, and navigate a rapidly changing landscape. The difficulties associated with CI are often centered on the need for agility, strategic responsiveness, and the ability to outperform rivals.

Conversely, CD involves challenges emanating from the expectations and requirements of customers and is therefore more controllable for sales teams. Sales teams facing demanding customers need to excel in areas such as negotiations, customization, and service quality. The difficulties associated with CD revolve around meeting or exceeding customer expectations, building and maintaining strong relationships, and delivering value in a customer-centric manner. In the face of rising customer demands, individual perceptions of emergent leaders play a crucial role in guiding the team, fostering collaboration, and adapting strategies to meet customer expectations. The negative moderation effect indicates that, under high CI, the positive impact of IPLE on PTSP is attenuated. This could be attributed to the fact that in highly competitive environments, team success might be influenced more by firm-level strategic decisions or organizational responses, rather than the emergent leadership within the team. In summary, the positive effect of IPLE on PTSP is robust when salespeople perceive increasing customer demands. However, as CI rises, the contribution of individual perceptions of emergent leadership may become less decisive, suggesting that other external factors and organizational strategies play a more prominent role in determining team success.

Despite our surprising finding regarding CI, we were able to confirm all our remaining hypotheses. Thereby, we provide strong contributions to both research and practice in the under-researched field of LE in the team selling context. We offer numerous suggestions for further research on this topic and provide decision-making attributes for practitioners. In the following, we discuss research and managerial implications in more detail.

Implications

Theoretical implications

Our study contributes to research on LE and extends research on team selling by examining this important but rarely studied subject. As highlighted in our literature review, studies on predictors of LE have dominated academia and explain which individual or team-based aspects lead to LE (e.g. DeRue, Nahrgang, and Ashford Citation2015; Zhang, Waldman, and Wang Citation2012): ‘[…] most research has […] focused on antecedents without including organizationally relevant outcomes. This has led to an unwarranted assumption that emergent leadership is uniformly positive […]’ (Hanna et al. Citation2021, p. 89).

Hence, we address this first critical finding, that leadership studies have to date almost excluded situational factors and also failed to consider the underlying theoretical mechanisms for different effects of LE. Our main contribution in this area is to provide a sound theoretical framework for IPLE and to explain how situational conditions affect IPLE and thereby influence outcomes. Our results show a direct effect of IPLE on PTSP. This effect significantly increases or decreases, depending on the job demands resulting from CD and CI.

Second, most studies on LE have been based on the fundamental premise that LE must be supportive. Again, in a comprehensive meta study Hanna et al. (Citation2021) underscored this insufficient assumption and called for further research on the dark side of LE. Prior work (Mathieu et al. Citation2019; Podsakoff et al. Citation1993) or, more specifically, research regarding implicit leadership (Kirkman and Rosen Citation1999; Tepper Citation2000) has indicated that leadership can be influenced by situational conditions that amplify or mitigate effects of LE. Although our study did not initially propose any negative direct or contingency effects, we address the call of Hanna et al. (Citation2021) in showing that IPLE become less effective when implicit leaders are less able to provide sufficient job resources. That is, in our study, we find countervailing effects of IPLE that vary when the context of the team changes. Our main contribution in this area is to discuss LE in a more differentiated vein than has been the case to date.

Third, studies have primarily investigated team structures outside the corporate environment. For example, DeRue, Nahrgang, and Ashford (Citation2015) show that MBA students who identify more with a group contribute more often to within-group leadership. Similarly, in their study with undergraduate business students, Charlier et al. (Citation2016) show a moderating effect of team dispersion on the relationship between communication skills and LE. Cogliser et al. (Citation2012) also use a sample of undergraduate business students to show a relationship between leadership behavior and team members’ performance contribution. In sum, the studies highlighted and reflected in our literature review (see ) reveal highly relevant insights regarding predictors (DeRue, Narhgang and Ashford Citation2015), moderators (Charlier et al. Citation2016) and even outcomes (Cogliser et al. Citation2012) of LE. However, they fail to explain such effects for corporate work teams or more specifically for sales teams.

Finally, as our dataset represents the field of sales, we clearly position our study at the intersection of LE and team selling. Although numerous studies have covered the issue of leadership in the selling context (e.g. Dubinsky et al. Citation1995; MacKenzie, Podsakoff, and Rich Citation2001; Panagopoulos and Dimitriadis Citation2009; Schmitz, Lee, and Lilien Citation2014; Shannahan, Bush, and Shannahan Citation2013), little prior research has examined LE in self-managed teams. To date and to the best of our knowledge, no study in the sales and marketing research has investigated LE in the team selling context. Thus, our study contributes significantly to the understanding of how members of sales teams respond to situational pressure from customers and competitors, particularly when leaders emerge in self-managed teams where no explicit leader is appointed. With this in mind, our study should be understood as a starting point for fellow researchers investigating situational factors and outcomes of LE and hopefully increasingly conducting their studies in the marketing and sales context.

Managerial implications

Our study shows that IPLE can be a supportive element for self-organized teams in the sales context. Hence, companies should foster and enable the emergence of potential leaders within their sales teams. Salespeople could be encouraged to emerge as implicit leaders through very clear communication of roles and responsibilities along the sales process throughout the sales organization. In addition, IPLE can be strengthened if one salesperson is defined as the owner of each sales opportunity, coordinating all respective sales functions to coordinate and share the necessary tasks and deliverables to maximize team sales performance. The enablement of salespeople to emerge as leaders should be crucial to prevent damaging results from implicit leadership, such as relational conflicts (De Dreu and Weingart Citation2003; DeRue and Ashford Citation2010). One concrete measure could be the use of training for implicit leadership, which should focus less on authority and self-image of leadership roles and more on applicable leadership and communication tools for implicit leaders.

Previous research has assumed that teams are more receptive to leadership when pressure increases (e.g. Kerr et al. Citation1974). Our study confirms this perception. Thus, we recommend close evaluation of the situational conditions a team is exposed to. Increasing customer demands suggest that the associated job demands can be offset by the job resources associated with IPLE. When customer demands are steadily more relevant, we advise strengthening IPLE to maximize PTSP. As in the sales context a lack of influence on team members’ tasks and outcomes should be highly relevant owing to the division of labor along the sales process, we recommend addressing this topic with training programs. Implicit leaders should initiate the requisite structure by clearly communicating the priority and sequence of tasks. Especially in self-organized teams, this communication must be carefully managed, underscoring the need for communication-based training. If such training enables implicit leaders to provide sufficient job resources by initiating structure in the team and even managing conflict when it arises, it can positively impact the sales team’s performance.

With respect to the competitor side, our recommendation is less straightforward. While sales teams may exert a degree of control over their strategies and approaches to address increasing CD, the same level of controllability may not extend to CI. The competitive landscape, shaped by external market forces and the actions of rival organizations, introduces complexities and uncertainties that may be less amenable to direct control by individual sales teams. When competition is fierce, as in the product business, we suggest not actively strengthening LE because our results show that such an effort is likely to be ineffective. A more appropriate approach may be to address competition from the sidelines. To avoid the need for team members to emerge as leaders when CI increases, companies and their managers should equip salespeople as much as possible with countermeasures and tools. These could take the form of specific training to gain deeper knowledge about the competitor’s product portfolio, pricing, and unique value propositions. Moreover, tangible instruments such as sales folders and negotiation guidelines may be of great help in preparing salespeople and making them responsible for their customer relationship. When salespeople are equipped with the necessary knowledge and tools to face the competition, they may be less likely to rely on the emergence of leaders from within the team.

However, when CI is less pronounced, we suggest emphasizing LE, because our findings indicate that the perception of leadership emergence increases the team’s sales performance. Again, one concrete measure could be to train and connect potential leaders so they can improve their knowledge and share experience about LE in self-organized teams.

Limitations and avenues for future research

Our study offers promising avenues for further research. First, with respect to our conceptual framework, we suggest investigation of more extensive models that reflect the whole bandwidth of situations a sales team may be exposed to. For instance, the impact of IPLE under conditions of diverse skills and the impact on resulting team dynamics such as conflicts may be worth investigating, as diverse teams also matter in this context. Further aspects of potential situations that can influence the effectiveness of teamwork may be found in the input-process-output model (Gladstein Citation1984; Hackman and Morris Citation1975). Exploring variables such as team size, team tenure, and gender dispersion as potential moderators aligns with the nuanced nature of LE. By investigating how these situational factors interact with emergent leadership dynamics, we can gain a deeper understanding of when and under what circumstances the potential negative effects of emergent leadership might exacerbate or mitigate. Unraveling these complexities could enhance our understanding and contribute valuable insights to the nuanced interplay between LE and team outcomes.

Furthermore, recognizing the intriguing nature of examining agreement or disagreement in team member perceptions of LE, we acknowledge the current limitations of our data and study design. Our instructions to salespeople, prompting them to reflect on their individual project teams, inadvertently create variability in the teams considered. Consequently, directly assessing the level of agreement or disagreement within specific teams becomes a challenge. We posit this as a noteworthy limitation and a promising avenue for future research, suggesting that more nuanced investigations into the dynamics of shared perceptions within specific teams could provide valuable insights into the emergent leadership phenomenon. Additionally, future research could select a context where team members do not come from strongly different task environments and perspectives, thus allowing ratings on customers and competitors to align more closely than in our context.

Exploring an emergent leadership classification schema based on social/interpersonal aspects versus task/performance capabilities could provide further valuable insights into the dynamics of LE. Additionally, incorporating reluctant leadership theories may offer a nuanced understanding of how leaders, based on different attributes, respond to challenges such as CI. This classification could shed light on why certain emergent leaders might excel in specific situations while others face challenges.

Moreover, because of its high relevance in the sales context, the customer perspective may be of great interest in the investigation of LE. Possible links may be the customer’s perception of the dynamics that occur when the sales team and the buying organization interact and LE becomes visible, as during price negotiations.

Additionally, regarding outcomes of LE, we encourage researchers to include objective data in their studies. In our study, we lack an ideal measurement of team sales performance. However, we were able to find first correlations between our PTSP construct and objective sales performance data of certain sales team members. However, since IPLE may influence salespeople’s behavior (e.g. during price negotiations), including objective information such as sales or price performance data for all participants in the study would be of great interest. In future research, we encourage scholars to also extend their investigation beyond objective performance metrics. Exploring outcomes such as team and job satisfaction, turnover rates, customer retention, and lagged performance provides a holistic perspective on the impact of LE. Understanding how emergent leaders influence team dynamics, individual job satisfaction, and customer relationships will contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the complex interplay in sales teams. This nuanced approach can unveil the broader implications of LE and shed light on its effects across various dimensions, enriching the scholarly discourse in this domain.

Lastly, our study relies on data from a single company. Data on IPLE, PTSP and moderating variables were gathered through self-reports from sales team members. Caution should be exercised in making broad generalizations, as this dataset pertains specifically to a company with a distinct structure and maturity level. Although our reference company, its sales force, and dataset represent a broad spectrum and are relevant to many companies, we encourage researchers to empirically examine our findings in other industries or corporate settings. Future research could explore variations in company size or team structures. Utilizing multi-source data collection methods, incorporating perspectives from both team members and external observers, could enhance the robustness and comprehensiveness of findings. Despite this limitation, our study provides a foundational exploration of emergent leadership in sales teams and offers avenues for further investigation.

Web Appendix.docx

Download MS Word (237.2 KB)Declaration of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Alavi, S., E. Böhm, J. Habel, J. Wieseke, C. Schmitz, and F. Brüggemann. 2022. “The Ambivalent Role of Monetary Sales Incentives in Service Innovation Selling.” Journal of Product Innovation Management, 39 (3): 445–463. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12600.

- Alavi, Sascha, Pia A. Ehlig, and Johannes Habel. 2022. “Transformational and Transactional Sales Leadership during a Global Pandemic.” Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management 42 (4): 324–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/08853134.2022.2101462.

- Alavi, Sascha, Johannes Habel, Paolo Guenzi, and Jan Wieseke. 2018. “The Role of Leadership in Salespeople’s Price Negotiation Behavior.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 46 (4): 703–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-017-0566-1.

- Anderson, Erin, and Richard L. Oliver. 1987. “Perspectives on Behavior-Based versus Outcome-Based Salesforce Control Systems.” Journal of Marketing 51 (4): 76–88 https://doi.org/10.1177/002224298705100407.

- Armstrong, J. Scott, and Terry S. Overton. 1977. “Estimating Nonresponse Bias in Mail Surveys.” Journal of Marketing Research 14 (3): 396–402. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224377701400320.

- Auh, Seigyoung, and Bulent Menguc. 2005. “Balancing Exploration and Exploitation: The Moderating Role of CI.” Journal of Business Research 58 (12): 1652–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2004.11.007.

- Badura, Katie L., Emily Grijalva, Daniel A. Newman, Thomas T. Yan, and Gahyun Jeon. 2018. “Gender and Leadership Emergence: A Meta-Analysis and Explanatory Model.” Personnel Psychology 71 (3): 335–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12266.

- Baer, Markus, and Michael Frese. 2003. “Innovation is Not Enough: Climates for Initiative and Psychological Safety, Process Innovations, and Firm Performance.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 24 (1): 45–68. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.179.

- Bagozzi, Richard P., and Youjae Yi. 1988. “On the Evaluation of Structural Equation Models.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 16 (1): 74–94https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02723327.

- Becherer, Richard C., Fred W. Morgan, and Lawrence M. Richard. 1982. “The Job Characteristics of Industrial Salespersons: Relationship to Motivation and Satisfaction.” Journal of Marketing 46 (4): 125–35. https://doi.org/10.2307/1251368.

- Beeler, Lisa, Alex R. Zablah, and Adam Rapp. 2022. “Ability is in the Eye of the Beholder: How Context and Individual Factors Shape Consumer Perceptions of Digital Assistant Ability.” Journal of Business Research 148: 33–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.04.045.

- Belsley, David A., Edwin Kuh, and Roy E. Welsch. 1980. Regression Diagnostics: Identifying Influential Data and Sources of Collinearity. New York: John Wiley & Son.

- Berson, Yair, Orrie Dan, and Francis J. Yammarino. 2006. “Attachment Style and Individual Differences in Leadership Perceptions and Emergence.” The Journal of Social Psychology 146 (2): 165–82. https://doi.org/10.3200/SOCP.146.2.165-182.

- Bliese, Paul D. 1998. “Group Size, ICC Values, and Group-Level Correlations: A Simulation.” Organizational Research Methods 1 (4): 355–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442819814001.

- Boichuk, Jeffrey P., Willy Bolander, Zachary R. Hall, Michael Ahearne, William J. Zahn, and Mellisa Nieves. 2014. “Learned Helplessness among Newly Hired Salespeople and the Influence of Leadership.” Journal of Marketing 78 (1): 95–111. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.12.0468.

- Boiney, Lindsley G. 2001. Gender Impacts Virtual Work Teams: Men Want Clear Objectives While Woman Value Communication. Accessed November 23, 2021. http://gbr.pepperdine.edu/014/teams.html.

- Bonney, F. Leff, and Brian C. Williams. 2009. “From Products to Solutions: The Role of Salesperson Opportunity Recognition.” European Journal of Marketing 43 (7/8): 1032–52. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560910961506.

- Breevaart, Kimberley, and Arnold B. Bakker. 2018. “Daily Job Demands and Employee Work Engagement: The Role of Daily Transformational Leadership Behavior.” Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 23 (3): 338–49. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000082.

- Burke, C. Shawn, Deborah DiazGranados, and Eduardo Salas. 2011. “Team Leadership: A Review and Look Ahead.” In The Sage Handbook of Leadership, edited by A. Bryman, D. Collinson, B. Jackson, K. Grint, and M. Uhl-Bien, 338–52. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage publications.

- Campion, Michael A., Gina J. Medsker, and A. Catherine Higgs. 1993. “Relations between Work Group Characteristics and Effectiveness: Implications for Designing Effective Work Groups.” Personnel Psychology 46 (4): 823–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1993.tb01571.x.

- Chan, Ricky Y., Hongwei He, Hing K. Chan, and William Y. C. Wang. 2012. “Environmental Orientation and Corporate Performance: The Mediation Mechanism of Green Supply Chain Management and Moderating Effect of CI.” Industrial Marketing Management 41 (4): 621–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2012.04.009.

- Chang, Sea-Jin, Arjen Van Witteloostuijn, and Lorraine Eden. 2010. “Common Method Variance in International Business Research.” Journal of International Business Studies 41 (2): 178–84. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2009.88.

- Charlier, Steven D., Greg L. Stewart, Lindsey M. Greco, and Cody J. Reeves. 2016. “Emergent Leadership in Virtual Teams: A Multilevel Investigation of Individual Communication and Team Dispersion Antecedents.” The Leadership Quarterly 27 (5): 745–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2016.05.002.

- Christmann, Petra. 2004. “Multinational Companies and the Natural Environment: Determinants of Global Environmental Policy Standardization.” Academy of Management Journal 47 (5): 747–60. https://doi.org/10.2307/20159616.

- Cogliser, Claudia C., William L. Gardner, Mark B. Gavin, and J. Christian Broberg. 2012. “Big Five Personality Factors and Leader Emergence in Virtual Teams: Relationships with Team Trustworthiness, Member Performance Contributions, and Team Performance.” Group & Organization Management 37 (6): 752–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601112464266.