Abstract

Objective: Because the working memory (WM) has a limited capacity, the cognitive reactions towards persuasive information in the WM might be disturbed by taxing it by other means, in this study, by inducing voluntary eye movements (EMi). This is expected to influence persuasion.

Methods: Participants (N = 127) listened to an auditory persuasive message on fruit and vegetable consumption, that was either framed positively or negatively. Half of them was asked to keep following a regularly moving dot on their screen with their eyes. At pretest, cognitive self-affirmation inclination (CSAI) was assessed as individual difference to test possible moderation effects.

Results: The EMi significantly lowered the quality of the mental images that participants reported to have of the persuasive outcomes. With regard to self-reported fruit and vegetable consumption after two weeks, EMi significantly lowered consumption when CSAI was high but it significantly increased consumption when CSAI was low.

Conclusions: The results verify our earlier findings that induced EM can influence persuasion. Although it remains unclear whether the effects of EMi were caused by disturbing mental images of persuasive outcomes or self-regulative reactions to these images, or both, the WM account may provide new theoretical as well as practical angles on persuasion.

Introduction

The effectiveness of persuasive health messages is often lowered by recipients’ defensive reactions (Liberman & Chaiken, Citation2003; Good & Abraham, Citation2007; Ruiter, Abraham, & Kok, Citation2001). These reactions can be conceptualized as self-regulatory actions that are meant to lower the aversive feelings of threat caused by the message (Baumeister & Vonasch, Citation2015; Dijkstra, Citation2018). Because these actions can lower the effectiveness of persuasive messages that advocate healthy behaviours, they may be held responsible for the preservation of risky behaviours. The study of such defensive self-regulatory actions is one important way to increase effectiveness of all kinds of preventive health interventions.

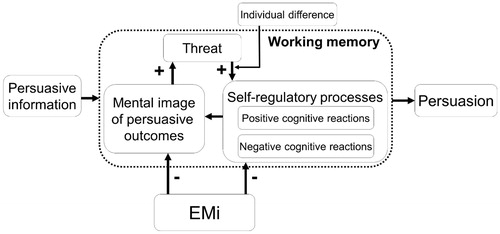

The working memory account

One emerging perspective on defensive self-regulatory actions is that they are ‘located’ in the working memory (WM). The WM is the virtual place where attention is directed, where incoming information is compared to stored information, and where ongoing reactions are initiated and regulated (Baddeley, Citation1986, Citation2012). Persuasive processes take place in the WM, and in persuasion two phases may be recognized. In the first phase, the persuasive information enters the WM, where it is linked to information from the long-term memory (Kruglanski & Thompson, Citation1999; Symons & Johnson, Citation1997). This combination can provide self-relevant meaning to the incoming information, and may result in the development of a mental image (Kosslyn, Reiser, Farah, & Fliegel, Citation1983; Pearson, Naselaris, Holmes, & Kosslyn, Citation2015) of the core persuasive outcomes in a message (Bolls & Lang, Citation2003; Bruyer & Scailquin, Citation1998), for example, the negative consequences of one’s own unhealthy behaviour. These mental images may trigger the experience of a threat, possibly with its accompanying emotions, such as fear (Witte, Citation1992).

When the threat passes a certain threshold, the second phase may be activated to down-regulate the threat, which is a manifestation of emotion–regulation (Gross, Citation2007), or more general, of self-regulatory action (Koole & Aldao, Citation2017). These cognitive self-regulatory actions may consist of processes that reject the persuasive message or processes that direct the behaviour towards a solution in line with the persuasive message (Witte, Citation1992). Thus, the WM account of persuasion assumes that the development of mental images (Bolls & Lang, Citation2003; Bruyer & Scailquin, Citation1998; Gunter & Bodner, Citation2008; van den Hout, Engelhard, Rijkeboer, et al., Citation2011) as well as the self-regulatory actions (Barret, Tugade, & Engle, 2004; Hinson, Jameson, & Whitney, Citation2003) take place in the WM.

A central premise is that the development of mental images and self-regulatory actions is not for free: They demand WM space. This implies that when there is not enough WM space, one or both processes may not completely unfold: mental images may fail to reach high quality (e.g. vividness) and/or self-regulatory actions may be prevented. This may have various effects on persuasion. Thus, the available WM space can be expected to influence persuasion, which implies that taxing the WM with another, competing task will influence persuasion. One way to tax the WM is by inducing regular eye movements.

Induced eye movements

Induced horizontal eye movements (EMi) have been studied in the context of understanding and treating PTSD (Shapiro, Citation1999), in which fearful and traumatic memories are central (Davidson & Parker, Citation2001): EMi have been shown to lower the vividness of mental of images from autobiographical memories of negative events (Gunter & Bodner, Citation2008; van den Hout, Engelhard, Rijkeboer, et al., Citation2011; van den Hout, Engelhard, Beetsma, et al., Citation2011). EMi influenced psychophysiological parameters (Schubert, Lee, & Drummond, Citation2011), and the startle reflex during the recall of such memories (Engelhard, van Uijen, & van den Hout, Citation2010) indicating less reactivity. In addition, EMi lowered vividness and emotionality of distressing images about feared future events (Engelhard, van den Hout, Janssen, & van der Beek, Citation2010), and of positive memories (Engelhard, van Uijen, et al., Citation2010; van den Hout, Muris, Salemink & Kindt, Citation2001). Although most studies induced horizontal EM, it seems that vertical EMi have similar effects (Gunter & Bodner, Citation2008). Indeed, the effects do not seem unique to (horizontal) EMi but have also been generated with other tasks, such as playing the game Tetris (Engelhard, van Uijen, et al., Citation2010; Engelhard, van den Hout, et al., Citation2010), although the effects of auditory stimuli (beeps) were smaller (van den Hout, Muris, Salemink, & Kindt, Citation2001). All these effects seem to be best explained by a WM account in which the EMi demand WM space as a competing task.

EMi in persuasion

As proposed above, in persuasion, mental images and self-regulatory reactions to these mental images are brought about in the WM. Firstly, EMi can disturb the development of mental images of the persuasive outcomes. This can have two effects: Or there is no persuasive power left, or there is some persuasive power left but the level of threat stays below a threshold, thereby preventing the mobilization of self-regulatory actions. In the latter case, EMi influence self-regulatory reactions indirectly (through effects on mental images). The persuasive effects depend on the type of self-regulatory processes that are prevented. Secondly, EMi can disturb the development of self-regulatory actions directly. The persuasive effect of disturbing the self-regulatory actions will depend on the type of action; in persuasion negative (defensive self-regulation) as well as positive cognitive reactions are conceptualized. According to the Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM; Petty & Cacioppo, Citation1986) people react with unfavourable, neutral or favourable thoughts to persuasive messages, and these thoughts have been captured in studies that applied a thought-listing procedure (Cacioppo & Petty, Citation1981). Unfavourable or negative reactions or thoughts in persuasion have been shown to manifest as counterarguments that need self-regulatory resources, and, thus, can be conceptualized as self-regulation (Dijkstra, Citation2018; Wheeler, Briñol, & Hermann, Citation2007). Yet, the favourable or positive reactions or thoughts can be conceptualized as self-regulation as well, and have been located in the WM (Hofmann, Gschwendner, Friese, Wiers, & Schmitt, Citation2008; Kane & Engle, Citation2003).

From the above it follows that the persuasive effects of EMi that disturb self-regulatory actions in the WM depend on the dominant processes that take place and are disturbed. When people react with defensive self-regulatory processes (negative/unfavourable thoughts) – which have the potential to lower persuasion – EMi will disturb these inhibiting processes and, therefore, will lead to increased persuasion. When people react with supporting self-regulatory processes (positive/favourable thoughts) – which have the potential to increase persuasion – EMi will disturb these facilitating processes and, therefore, will lead to decreased persuasion.

Our earlier study provided some first evidence for the WM account of persuasion using EMi (Dijkstra & van Asten, Citation2014): Participants who listened to a persuasive message were significantly more persuaded to eat fruit and vegetables when EMi were applied during listening. EMi seemed to have prevented or disturbed the defensive self-regulation that could lower persuasion. This was verified by the application of a self-affirmation procedure: This procedure – which is an established manipulation to prevent defensive self-regulatory actions (McQueen & Klein, Citation2006; Sweeney & Moyer, Citation2015) – revealed the presence of defensive self-regulation, as it also led to significantly more persuasion. Moreover, when self-affirmation was applied, EMi no longer increased persuasion, suggesting that there were no defensive self-regulation processes left to disturb.

Determinants of self-regulatory actions

EMi are thought to disturb whatever reactions people have towards the persuasive information. This means that in some people EMi may disturb negative/inhibiting reactions, thereby increasing persuasion, but in other people it may also disturb positive/facilitating reactions, thereby decreasing persuasion.

The individual difference ‘cognitive self-affirmation inclination’ is related to positive as well as to negative reactions towards threatening persuasive information (CSAI; Pietersma & Dijkstra, Citation2010). A high score on the measure of CSAI indicates a strong inclination to cope with a self-threat by thinking of compensating positive self-images, selectively and functionally derived from one’s long-term memory. These reactive pop-ups of positive self-images have a self-affirming effect. Similar to the effect of a self-affirmation procedure, people high in CSAI stay open-minded towards the information that causes the self-threat, and they do not engage in defensive self-regulatory actions (Harris & Napper, Citation2005; Sweeney & Moyer, Citation2015). Instead, they process the information open-minded and become painfully aware of their own role in generating unhealthy effects, leading to negative self-evaluation (Jessop, Simmonds, & Sparks, Citation2009; van Koningsbruggen et al., Citation2016). Thus, the positive cognitive reactions of people high in CSAI support persuasion. On the other hand, a low score on CSAI indicates the use of other strategies to deal with the threat. An earlier study suggests that the intention of people with low CSAI was actively lowered by defensive self-regulatory actions (Pietersma & Dijkstra, Citation2010): Those low in CSAI are expected to hold off the threat by negative cognitive reactions that inhibit persuasion. Thus, it is expected that in people high in CSAI, EMi will disturb supporting processes, thereby decreasing persuasion. In contrast, in people low in CSAI, EMi will disturb defensive processes, thereby increasing persuasion. summarizes the main concepts in the present WM account of persuasion.

Besides individual differences, message features influence how people will react. A considerable amount of research has been done to understand and influence defensive reactions towards health messages (see van’t Riet & Ruiter, Citation2013 for an overview), and one core dimension of messages is how threatening they are (Witte, Citation1992): Specifically messages that induce a moderate or high threat, not a low threat, can be expected to activate defensive self-regulation. Typically, these threatening messages apply a negative frame: They stress the negative outcomes of an unhealthy behavior (e.g. ‘a low fruit and vegetables consumption increases the risk for cancer’), thereby triggering reactions to cope with the resulting threat. In contrast, a positive frame (e.g. ‘a high fruit and vegetables consumption decreases the risk for cancer’) might be expected to be less threatening, thereby triggering lower levels of defensive self-regulatory actions (see Dijkstra, Rothman, & Pietersma, Citation2011), but also more positive thoughts (Tykocinski, Higgins, & Chaiken, Citation1994)

The present study

The aim is to study the effects of EMi in persuasion. In a 2(EMi versus no EMi) × 2(Positive frame versus Negative frame) experiment, participants listen to a positively or negatively framed persuasive audio message promoting fruit and vegetable consumption, while in half of them EM will be induced (following a dot on a computer screen with one’s eyes). The dependent variable is actual (self-reported) fruit and vegetable consumption assessed after two weeks.

It is expected that CSAI moderates the effects of EMi: When scores on this individual difference lead to negative/inhibiting processes (low CSAI) EMi will disturb them, thereby increasing persuasion. The other way around, when the scores on this individual difference lead to positive/supporting processes (high CSAI) EMi will disturb them, thereby lowering persuasion. These effects may only occur in the case of a negatively framed message; in the case of positive framing few cognitive reactions will be triggered that might be disturbed by EMi because the threat remains low.

The goal of this study is not to reveal mechanisms (e.g. whether self-regulation is influenced directly or indirectly) but to replicate our earlier finding that EMi can influence persuasion. Still, one brief process measure will be included, also to relate to the line of WM research in PTSD (Engelhard, van den Hout, et al., Citation2010): The participants’ perceived quality of the mental image of the persuasive outcomes that will be induced by the persuasive message. In addition, our earlier study showed that EMi effects were related to self-esteem (Dijkstra & van Asten, Citation2014). Therefore, the role of self-esteem will also be considered in this study.

Method

Recruitment

Participants were recruited in two ways. Firstly, Psychology students of the University of Groningen were given the opportunity to earn course credits by joining the study; the study was promoted in the internal participant pool system. Second, students on the campuses of the University of Groningen and the Hanze University Groningen were approached personally; these students could earn 5 euro. In all recruitment, communication students were asked to come to the near Heymans Institute Psychology Laboratorium to join a study on ‘the influence of personality characteristics on listening’.

Design

Participants were randomly assigned to one of four conditions in a 2(EMi versus no-EMi) × 2(positive versus negative framing)-design. The dependent variable self-reported fruit and vegetable consumption was assessed after two weeks outside the laboratory, through the internet. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee Psychology (ECP) of the Faculty of Behavioural and Social Sciences.

Procedure

Participants were seated behind a PC in individual cubicles in the Psychology laboratory. They were told that they would participate in a study which included an auditory message and a number of questionnaires about their personality and their personal values. Participants were introduced to the study by a screen with the informed consent form and statements on the confidentiality of the research and the duration of the study (approximately 15 min). Participants were asked to complete the pretest measures prior to exposure to the coming auditory information. Subsequently, the introductory screens regarding the auditory information were presented, including an instruction on the regulation of the volume of the message: A 15 s auditory trial was presented to the participants to let them find the optimal volume on their headphone if necessary. Next, participants were randomized by the computer system to one of the four conditions. Participants in the EMi condition read the EM instruction. Then, all participants were exposed to the auditory persuasive message. Lastly, participants filled in the immediate posttest questions. They were also asked to leave their email address for the follow-up measurement. About two weeks after this experimental procedure, participants were sent an email with a link to an online questionnaire to assess their self-reported fruit and vegetable consumption. At the end of this questionnaire participants were debriefed.

The persuasive message

The auditory persuasive messages advocated fruit and vegetables consumption. The negatively framed message was the same as used by Dijkstra and van Asten (Citation2014); it was comprised of 243 words (110 s) – that mentioned the possible negative outcomes of not eating sufficient levels of fruit and vegetables (mainly losses, e.g., ‘larger risk for cancer’). The positively framed message was similar – comprised of 243 words (107 s) – but mentioned the possible positive outcomes of eating sufficient levels of fruit and vegetables (mainly non-losses, e.g., ‘lower risk for cancer’). Besides the information on these major outcomes related to fruit and vegetable consumption, consumption was said to be related to looking healthy (less versus more, respectively), to physical stamina (worsened versus better, respectively) and to aging ((un)healthier skin and hair, respectively). Two intermediary physical states were presented to be related to these consequences: (high versus lower, respectively) blood pressure and (high versus lower, respectively) high cholesterol. These effects were told to be related to lowered (or increased) intake of vitamins C and E.

To be able to apply a visual EMi (a dot on the screen), the message was offered through the auditory channel. A female voice that presented the message was selected in collaboration with a professional recording studio. The message was recorded in the studio by giving the actor instructions of speaking at normal rate and normal intonation, as the actor would read it like a professional newsreader.

The EMi manipulation

In the EM condition, participants were instructed to listen to the auditory message and at the same time look at the moving dot: ‘On the screen you will see a dot moving from left to right and vice versa. Please, follow the dot with your eyes while listening to the auditory message’. The size of the dot was 20 mm. It moved from one side of the screen to the other (30 cm) in 2 s, and it kept on moving until the auditory message was finished. Adherence to the eye-movement instructions was not assessed; only covert observation indicated that all participants in the EMi condition displayed the eye-movements at some time during the auditory message. Participants in the no-EMi condition were not presented with a moving dot, and only listened to the audio message

Measures

Pretest measures

In the first part of the questionnaire, participants were asked for their gender and age. In addition, they were asked to provide an estimate of their fruit and vegetable consumption: They could finish the sentence, ‘In general, I eat….’, which was followed by five options they had to choose one from: ‘far too little fruit’ (1); ‘too little fruit’ (2); ‘somewhat too little fruit’ (3); ‘sufficient fruit’ (4); ‘more than sufficient fruit’ (5). The same format was used to assess perceived vegetable intake.

Cognitive Self-affirmation Affirmation Inclination (CSAI) was assessed with six items on the experienced frequency of having specific self-related positive thoughts (Pietersma & Dijkstra, Citation2010). This earlier study showed that high scores on the CSAI led to the open-minded processing of threatening information, similar to the effects of a self-affirmation procedure. Low scores led to a defensive reaction towards a (moderate) threat. The following statements were part of the CSAI scale: ‘I notice that I do some things very well’, ‘When I feel bad about myself, I think about all the things that I can be proud of’, ‘I think about the past and all the things that I have successfully accomplished’, ‘I think about all the things that I have successfully accomplished’, ‘When I have done something wrong that makes me feel dissatisfied with myself, I tell myself that I do not do everything wrong’ and ‘I realize that besides all the “stupid” things I do, I also do some things very well’ (end-points 1 [never] and 5 [very often]).

Self-esteem was assessed with the 10-item Rosenberg (Citation1965) self-esteem scale (Cronbach’s α = 0.85). Next, a new eight-item measure of imaginary ability was applied but will not presented here as it is not pertinent to the present study.

Posttest measures immediate

Right after listening to the message, participants were asked about their mental images during the audio text using three items: ‘When you listened to the auditory message: “… were you able to make a mental representation of…”; “…how lucid was your mental representation of…’; “…how lively was your mental representation of…”; “…the consequences of a low fruit and vegetable consumption?”’. All three items could be answered on a 5-point scale from ‘not at all’ (1) to ‘very much’ (5). A scale of mental image quality was created by averaging the scores on these three items (α = 0.83).

Next, a two-item measure of attention/distraction was employed in all conditions: ‘Were you able to concentrate on listening to the text about fruit and vegetable consumption?’, and ‘How much attention did you have for the text on fruit and vegetable consumption?’ The answers could be given on a 5-point scale from ‘very bad’/‘little attention’ (1) to ‘very good’/‘much attention’ (5). Both items correlated significantly 0.77, and were combined in a single attention/distraction scale.

Next, a six-item measure of intention to consume more fruit and vegetables was applied. Because the outcomes on this measure will not be presented, the measure will not be further outlined here.

Manipulation checks of EMi and message framing were conducted at the very end of the study. Unfortunately, due to programming error the data manipulation check data on message framing could not be retrieved. Only participants in the EMi condition were asked: ‘How well did you succeed in looking at the dot while listening to the audio message?’ The answer could be given on a 7-point scale from ‘not at all’ (1) to ‘completely’ (7).

Posttest measure follow-up

Two weeks after completion of the experiment, respondents were sent the link to the online follow-up questionnaire as an obligatory part of the study. The questionnaire was a detailed and validated frequency-questionnaire on the own average weekly fruit and vegetable intake regarding the past two weeks (self-reported fruit and vegetable intake; Bogers, van Assema, Kester, Westerterp, & Dagnelie, Citation2004; Elbert, Dijkstra, & Oenema, Citation2016). Respondents were asked to indicate how often on average they ate or drank products from several fruit and vegetable categories during the previous week. The answering options ranged from ‘never or less than 1 day a week’ (0), ‘1 day a week’ (1) to ‘every day’ (7). Next, they were asked to indicate the amount of intake per category of fruit or vegetables in terms of pieces of fruit and servings of vegetables (answering options ranged from ‘no pieces/glasses/serving spoons’ to ‘five or more pieces/glasses/serving spoons’). The main categories were ‘cooked vegetables’, ‘raw vegetables/salad’, ‘fruit/vegetable juice’, ‘tangerines’, ‘oranges/grapefruits/lemons’, ‘apples/pears’, ‘bananas’, ‘other fruit’ and ‘apple sauce’. The average number of days per week and the pieces of fruit and vegetable portions (defined as 50 g each) were multiplied for each category and added to create a composite index of weekly fruit and vegetable intake.

Results

Participant characteristics

Of the 127 participants at pretest, 93% had a higher education degree, 71.9% was female, and their mean age was 21.2 (SD = 4.84). The mean CSAI score was 3.0 (SD = 0.62), while the mean score on the perceived own fruit and vegetable consumption was 3.48 (SD = 0.83).

Attrition analysis

At the two-week follow-up measurement 26 participants did not provide data. To test whether these non-respondents at the two-week follow-up differed from the respondents (n = 101), attrition analyses were conducted using t-tests for continuous variables and Chi-square analyses for categorical variables. No significant differences were present (ps > .14) on the tested variables gender, level of education, age, CSAI and perceived own consumption.

Randomization check

The participants were about equally distributed over de four conditions: EMi and positive frame n = 32; no EMi and positive frame n = 31; EMi and negative frame n = 32; no EMi and negative frame n = 32. To check for randomization, the four conditions were compared on the same variables as in the attrition analyses. The four conditions did not differ significantly regarding all variables (ps > .19).

Manipulation check

The data on the self-report of intended eye movements (‘How well did you succeed in…’) showed that of the 64 participants in the EMi conditions, only two scored lower than a 5 on the 7-point scale; 97% scored a 5 or higher; and 72% scored a 6 or 7. Thus, on the basis of this self-report, most participants seemed to have complied the eye movement task. As mentioned above, the manipulation check data on message framing were lost.

Process measure

The brief attention/distraction scale was used to check whether the EMi influenced the extent to which participants succeeded in listening to the audio. An ANCOVA with the pretest perceived fruit and vegetable consumption as covariate showed that in the EMi conditions participants scored significantly lower, F(1, 124) = 4.85, p = .006, η2 = 0.059 (EMi M = 3.79; no-EMi M = 4.18). This suggests that the EMi made it more difficult to keep their attention to the message, as was expected.

Mental image quality

The experienced quality of the mental images of the persuasive outcomes while listening to the audio message was assessed immediately after the audio finished. The influence of EMi on the image quality was computed with an ANCOVAs with EMi as factor and pretest perceived fruit and vegetable consumption as covariate. Participants in the EMi condition reported a significantly lower mental image quality (M = 3.59) than those in the no-EMi conditions (M = 3.9), F(1, 124) = 4.22, p = .042, η2 = 0.032. Mental image quality was not significantly correlated to behaviour after two weeks.

Effects on behaviour after two weeks

The analyses with dependent variable behaviour after two weeks were conducted on the 101 participants of whom behavioural data were available. To test whether the interaction effects between framing and EMi on behaviour differed for participants with different pretest levels of CSAI, a saturated ANCOVA was built with the Framing × EMi × CSAI interaction as the highest order factor. The dependent variable was fruit and vegetable consumption after two weeks, while the perceived own fruit and vegetable consumption was entered as a covariate. The latter covariate was included because it correlated significantly with the dependent variable, r = 0.33; p < .001; N = 101.

The three-way interaction was not significant (F(1, 92) = 1.07, p = .30, η2 = .012). However, in this model the two-way interaction between EMi and CSAI was significant (p = .009), and it remained significant when it was tested in a model with the EMi × CSAI interaction as the highest order factor, F(1, 96) = 8.37, p = .005, η2 = 0.08 (and pretest perceived own consumption as covariate). These results suggest that message framing did not make a difference in generating effects of EMi. Therefore, in the remainder of the analyses the framing conditions were combined.

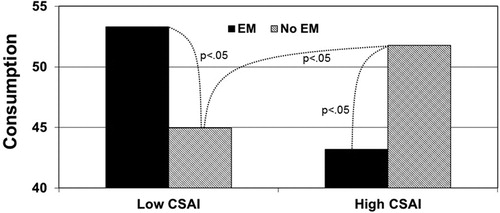

To search for the meaning of the EMi × CSAI interaction, contrast analyses were conducted when CSAI was low and when CSAI was high. The complete dataset for these analyses (N = 101) was modelled to represent two levels of CSAI scores, by subtracting and adding one from the individual standardized scores (z-scores), respectively (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, Citation2003; Siero, Huisman, & Kiers, Citation2009). shows the estimated means on fruit and vegetable consumption.

Figure 2. The two-week follow-up effects of induced eye movements on self-reported fruit and vegetables consumption, moderated by the individual difference CSAI.

When CSAI was modelled to be low, the EMi led to a significant increase in consumption, F(1, 92) = 4.09, p = .046, η2 = 0.041: from M = 45 without EMi to M = 53.3 with EMi. When CSAI was modelled to be high, the EM led to a significant decrease in consumption, F(1, 92) = 4.23, p = .042, η2 = 0.042: from M = 51.8 without EM to M = 43.2 with EMi. Only in the no-EMi condition CSAI was significantly correlated with fruit and vegetable consumption (partialing out the perceived fruit and vegetable consumption), r = 0.30; p < .05; n = 42.

The effect of self-esteem

In earlier studies, self-esteem moderated the effects of EMi (Dijkstra & Van Asten, Citation2014), and self-esteem was significantly related to CSAI (Pietersma & Dijkstra, Citation2010). Therefore, the role of self-esteem as individual difference assessed at pretest was studied in different ways. Firstly, the correlation between self-esteem and CSAI was significant (all participants r = 37; p < .001; N = 127) follow-up participants r = 0.42; p < .001; N = 101), replicating earlier results. Next, it was tested whether the earlier results on EMi and self-esteem could be replicated (Dijkstra & Van Asten, Citation2014), but this time on behaviour. In the present study, the EMi × self-esteem interaction on the follow-up behaviour approached significance, F(1, 96) = 3.74, p = .056, η2 = 0.038, and showed the same pattern of means in behaviour as was found on intention in our earlier study: When self-esteem was low, no-EMi led to a score of 43, EMi to a score of 48.5; when self-esteem was high, no-EMi led to a score of 54.3 and EMi to a score of 48.4. However, both contrasts were not significant (p > .16).

Lastly, both interactions, the EMi × self-esteem and the EMi × CSAI, were put in a single model, using the method recommended by Yzerbyt, Muller, and Judd (Citation2004). Only the EMi × CSAI interaction remained significant, F(1, 93) = 4.34, p = .04, η2 = 0.045; the EMi × self-esteem interaction disappeared (p > .28). In conclusion, the above findings on CSAI and the experimental manipulations were not due to individual difference in self-esteem.

Discussion

In our earlier study, induced eye-movements influenced the immediate intention. In the present study, it influenced fruit and vegetable consumption after two weeks, indicating that the effects of EMi are deep enough to influence actual behaviour. As induced eye-movements provide no persuasive information, they must have brought about their effects by influencing the processing of the auditory persuasive information, as we propose, in the WM.

The effects of EMi showed the predicted effects by CSAI: EMi increased persuasion in the case of low CSAI and it decreased persuasion in the case of high CSAI. These effects are in line with our theorizing that in low CSAI, EMi takes away defensive or negative processes, thereby increasing persuasion, while in high CSAI, EMi takes away facilitative or positive processes, thereby decreasing persuasion. On the other hand, EMi may have eroded mental image quality or vividness, in low CSAI below a threshold for self-regulatory reactions, and in high CSAI to such an extent that they lost persuasive power. The present study was not designed to solve the process issue.

The present data suggest that the negative framing (mainly losses) and the positive framing (mainly non-losses) did not lead to relevant differences in negative cognitive reactions nor in positive cognitive reactions. One possibility is that the framing manipulation was not successful. However, it is also plausible that the frames indeed did not differ on negative reactions. When the loss message mentioned: ‘a low fruit and vegetable consumption will lead to a larger risk for cancer’, our non-loss message mentioned: ‘a high fruit and vegetable consumption will lead to a lower risk for cancer’. Also in the latter positively framed message the associated consequence is still cancer, which may increase the perceived threat and, thereby, cognitive reactions to cope with the threat. It may be better next time to compare losses (e.g. ‘worse health’) not to non-losses (e.g. ‘no worse health’) but to gains (e.g. ‘better health’), which are positive in valence but also in type (Dijkstra et al., Citation2011).

The analyses regarding self-esteem showed that the above discussed findings were not confounded by self-esteem. Although self-esteem is conceptually related to CSAI (Pietersma & Dijkstra, Citation2010), CSAI had its own unique effects. CSAI is the inclination to gather positive self-images from ones self-memory in the case of a self-threat; the images probably are a selection out of all possible images (Pietersma & Dijkstra, Citation2010). Self-esteem on the other hand is the evaluation of the self, including all self-images. Our earlier study found a significant interaction between pretest self-esteem and EMi (Dijkstra & van Asten, Citation2014). The present study replicated the pattern of means, this time on behaviour, but the effects were not significant. Self-esteem is probably related to people’s reactions to persuasive messages (Greenberg et al., Citation1993), but CSAI may be more proximal in these effects.

In the present WM account of persuasion, EMi effects are brought about by directly disturbing the negative or positive self-regulatory actions that are mobilized in reaction to the mental images or by indirectly disturbing or preventing these action by lowering the quality of the mental images. In past persuasion research, the present effects of EMi would probably have been understood within the distraction paradigm of persuasion, in which distraction was: ‘…conceptualized either as the presentation of absorbing sensory stimulation (irrelevant to the speech) or the requirement that subjects perform irrelevant activity during a message’ (p. 310; Baron, Baron, & Miller, Citation1973; Keating & Brock, Citation1974). In this paradigm there is no mention of mental images or alike in persuasion, and the main understanding of distraction effects was ‘…that distraction inhibits the dominant cognitive response to a persuasive appeal’ (p. 883; Petty, Wells, & Brock, Citation1976). Our data can be understood through this perspective. Bringing together the EMi research line related to PTSD and fear (van den Hout et al., Citation2001) and the present line in persuasion, may reveal new perspectives: The former line inspires to look at the determinants of the unfolding of mental images in persuasion, while the latter line inspires to look at self-regulatory processes in reaction to mental images that may prevent recovery in PTSD. As in both lines of research EMi are thought to tax the WM, the present state-of-the-art begs for an integrative theorizing around psychological processes in the WM.

Above, the WM is presented simply as a ‘location’ in which cognitive actions take place. For the present theorizing, it is sufficient to understand that the WM has limited capacity (Baddeley, Citation2012; Kane & Engle, Citation2003; Schmeichel, Citation2007), and that taxing the WM with induced EM goes at the expense of the cognitive actions in progress (Andrade, Kavanagh, & Baddeley, Citation1997). However, in the conceptualization of Baddeley (Citation2012) the WM is comprised of a phonological loop and a visual/spatial sketch pad (besides the central executive and the episodic buffer) that process information that is vocabulary and visual, respectively. Research has shown that within these systems, stimuli may disturb each other because of limited capacity (Baddeley, Citation2012, but also see Bruyer & Scailquin, Citation1998). In the present study, however, eyes and ears were used simultaneously in the EMi condition, and no visual information that otherwise might have been verbalized internally (and might enter the phonological loop) was processed. This design did not include interference within the loop or the sketch pad. Thus, our manipulations were not at the level of the loops but probably at the level of the overarching executive control that integrates information from different loops with the episodic buffer, which also has limited capacity (Baddeley, Citation2012); we do not know. In trying to understand exactly what happened in the present study it is also important to realize that the WM and the processes that take place in WM may be conceptualized differently. For example, Diamond (Citation2013) proposes three core Executive Functions that together determine reasoning, problem solving and planning: WM, Cognitive Flexibility and Inhibitory Control. In this conceptualization becomes even more puzzling where exactly our induced EM disturb the unfolding of mental images and self-regulatory actions. Although there is a lot of practical work to do in the field of persuasion by varying the stimuli that are expected to tax the WM, future studies must also provide a next level of understanding of ‘where’ defensive self-regulation finds place and ‘where’ they are influenced by induced EM.

The present study has some relevant limitations. Firstly, as mentioned above, the present study was not designed to test a theory on the WM. It is an early-phase study on persuasion that gathers evidence that induced EM indeed influence persuasion. Secondly, only one type and intensity of a stimulus that was thought to ‘tax the WM’ was used. It is unclear what the effects of, for example, auditory stimuli or a faster moving dot would have been. Future studies can carefully study the taxing that is effective in influencing persuasion. Thirdly, self-regulatory or defensive processes were not assessed, and were treated just as a phenomenon playing in the WM. However, in persuasion probably several different self-regulatory or defensive processes can play a role (van’t Riet & Ruiter, Citation2013). Fourthly, no main effects of EMi were found; the effects differed by pretest individual differences. The latter implies that it cannot be ruled out that some third variable caused the moderation effects, although it was not self-esteem. In addition, the persuasive effects of EMi do not do not depend on the eye-movements but on what the eye-movement bring about in the WM, and this is most probably related to individual differences. Lastly, the estimated level of fruit and vegetable consumption in the present study was relatively high, between 43 and 53. Although we cannot rule out that these self-reports are inflated by memory biases or social desirability, they are consistent with data that show that in the Netherlands the higher educated more often behave according to health guidelines, especially regarding vegetables consumption (‘Leefstijl en (preventief) gezondheidszonderzoek’, 2018).

To conclude, EMi do influence persuasion and research on the exact underlying processes will bring new breath to the field of persuasion. In addition, this study brings together the psychological perspectives of persuasion, distraction, WM, emotion-regulation (or self-regulation) and PTSD. This combination of angles may improve our understanding of the complex phenomenon of persuasion or behaviour modification.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ellen Kloen and Valerie Simonetti for their assistance in developing and conducting the present study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Andrade, J., Kavanagh, D., & Baddeley, A. (1997). Eye movements and visual imagery: A working memory approach to the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 36, 209–223. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8260.1997.tb01408.x

- Baddeley, A. D. (1986). Working Memory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Baddeley, A. D. (2012). Working memory: Theories, models, and controversies. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 1–29. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100422

- Baron, R. S., Baron, P. H., & Miller, N. (1973). The relation between distraction and persuasion. Psychological Bulletin, 80, 310–323. doi:10.1037/h0034950

- Baumeister, R. F., & Vonasch, A. J. (2015). Uses of self-regulation to facilitate and restrain addictive behavior. Addictive Behaviors, 44, 3–8. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.09.011

- Bogers, R. P., Van Assema, P., Kester, A. D. M., Westerterp, K. R., & Dagnelie, P. C. (2004). Reproducibility, validity, and responsiveness to change of a short questionnaire for measuring fruit and vegetable intake. American Journal of Epidemiology, 159, 900–909. doi:10.1093/aje/kwh123

- Bolls, P. D., & Lang, A. (2003). I saw it on the radio: The allocation of attention to high-imagery radio advertisements. Media Psychology, 5, 33–55. doi:10.1207/S1532785XMEP0501_2

- Bruyer, R., & Scailquin, J. (1998). The visuospatial sketchpad for mental images: Testing the multicomponent model of working memory. Acta Psychologica, 98, 17–36.

- Cacioppo, J. T., & Petty, R. E. (1981). Social psychological procedures for cognitive response assessment: The thought listing technique. In: T. Merluzzi, C. Glass, & M. Genest (Eds.), Cognitive assessment. New York: Guilford.

- Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2003). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. London: Erlbaum.

- Davidson, P. R., & Parker, K. C. H. (2001). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR): A meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69, 305–316.

- Diamond, A. (2013). Executive Functions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 135–168. doi:10.1146/annurevpsych-113011-143750

- Dijkstra, A. (2018). Self-control in smoking cessation. In D. de Ridder, M. Adriaanse, & K. Fujita (Eds.), Routledge international handbook of self-control in health and well-being. Concepts, theories, and central issues. New York: Routledge.

- Dijkstra, A., & van Asten, R. (2014). The eye movement desensitization and reprocessing procedure prevents defensive processing in health persuasion. Health Communication, 29, 542–551. doi:10.1080/10410236.2013.779558

- Dijkstra, A., Rothman, A., & Pietersma, S. (2011). The persuasive effects of framing messages on fruit and vegetable consumption according to regulatory focus theory. Psychology & Health, 26, 1036–1048. doi:10.1080/08870446.2010.526715

- Elbert, S. P., Dijkstra, A., & Oenema, A. (2016). A mobile phone app intervention targeting fruit and vegetable consumption: The efficacy of textual and auditory tailored health information tested in a randomized controlled trial. Journal of medical Internet research, 18, 1–18.

- Engelhard, I. M., van Uijen, S. L., & van den Hout, M. A. (2010). The impact of taxing working memory on negative and positive memories. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 1, 1–8. doi:10.3402/ejpt.v1i0.5623

- Engelhard, I. M., van den Hout, M. A., Janssen, W. C., & van der Beek, J. (2010). Eye movements reduce vividness and emotionality of images about “flashforwards”. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48, 442–447. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2010.01.003

- Greenberg, J., Pyszcynski, T., Solomon, S., Pinel, E., Simon, L., & Jordan, K. (1993). Effects of self-esteem on vulnerability-denying defensive distortions: Further evidence of an anxiety-buffering function of self-esteem. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 29, 229–251. doi:10.1006/jesp.1993.1010

- Good, A., & Abraham, C. (2007). Measuring defensive responses to threatening messages: A meta-analysis of measures. Health Psychology Review, 1, 208–229. doi:10.1080/17437190802280889

- Gunter, R. W., & Bodner, G. E. (2008). How eye movements affect unpleasant memories: Support for a working memory account. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46, 913–931. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2008.04.006

- Gross, J. J. (2007). Handbook of emotion regulation. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Harris, P. R., & Napper, L. (2005). Self-affirmation and the biased processing of threatening health-risk information. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, 1250–1263. doi:10.1177/0146167205274694

- van den Hout, M. A., Engelhard, I. M., Rijkeboer, M. M., Koekebakker, J., Hornsveld, H., Leer, A., Toffolo, M. B. J., & Akse, N. (2011). EMDR: Eye movements superior to beeps in taxing working memory and reducing vividness of recollections. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49, 92–98. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2010.11.003

- van den Hout, M. A., Engelhard, I. M., Beetsma, D., Slofstra, C., Hornsveld, H., Houtveen, J., & Leer, A. (2011). EMDR and mindfulness: Eye movements and attentional breathing tax working memory and reduce vividness and emotionality of aversive ideation. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 42, 423–431. doi:10.1016/j.jbtep.2011.03.004

- van den Hout, M. A., Muris, P., Salemink, E., & Kindt, M. (2001). Autobiographical memories become less vivid and emotional after eye movements. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 40, 121–130. doi:10.1348/014466501163571

- Hinson, J. M., Jameson, T. L., & Whitney, P. (2003). Impulsive decision making and working memory. Journal of Experimental Psychological: Learning, Memory and Cognition, 29, 298–306. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.29.2.298

- Hofmann, W., Gschwendner, T., Friese, M., Wiers, R. W., & Schmitt, M. (2008). Working memory capacity and self-regulation: Toward an individual differences perspective on behavior determination by automatic versus controlled processes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 962–969.

- Jessop, D. C., Simmonds, L. V., & Sparks, P. (2009). Motivational and behavioural consequences of self-affirmation interventions: A study of sunscreen use among women. Psychology and Health, 24, 529–544. doi:10.1080/08870440801930320

- Kane, M. J., & Engle, R. W. (2003). Working-memory capacity and the control of attention: The contributions of goal neglect, response competition, and task set to Stroop interference. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 132, 47–70. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.132.1.47

- Keating, J. P., & Brock, T. C. (1974). Acceptance of persuasion and the inhibition of counter argumentation under various distraction tasks. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 10, 301–309. doi:10.1016/0022-1031(74)90027-4

- van Koningsbruggen, G. M., Harris, P. R., Smits, A. J., Schüz, B., Scholz, U., & Cooke, R. (2016). Self-affirmation before exposure to health communications promotes intentions and health behavior change by increasing anticipated regret. Communication Research. doi:10.1177/0093650214555180

- Koole, S. L., & Aldao, A. (2017). In: K. D. Vohs & R. F. Baumeister (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation (3rd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

- Kosslyn, S. M., Reiser, B. J., Farah, M. J., & Fliegel, S. L. (1983). Generating visual images: Units and relations. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 26, 278–303. doi:10.1037//0096-3445.112.2.278

- Kruglanski, A. W., & Thompson, E. P. (1999). Persuasion by a single route: A view from the unimodel. Psychological Inquiry, 10, 83–109. doi:10.1207/S15327965PL100201

- Leefstijl en (preventief) gezondheidszonderzoek; persoonskenmerken. (2018, April 6). Retrieved from https://opendata.cbs.nl/statline/#/CBS/nl/dataset/83021NED/table/ts=1551792274559

- Liberman, A., & Chaiken, S. (2003). Defensive processing of personally relevant health messages. In P. Salovey and A. J. Rothman (Eds.). Social psychology of health (pp. 118–129). New York: Psychology Press.

- McQueen, A., & Klein, W. M. P. (2006). Experimental manipulations of self-affirmation: A systematic review. Self and Identity, 5, 289–354. doi:10.1080/15298860600805325

- Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1986). The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology. New York: Academic Press.

- Petty, R. E., Wells, G. L., & Brock, T. C. (1976). Distraction can enhance or reduce yielding to propaganda: Thought disruption versus effort justification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 34, 874–884. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.34.5.874

- Pearson, J., Naselaris, T., Holmes, E. A., & Kosslyn, S. M. (2015). Mental imagery: Functional mechanisms and clinical applications. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 19. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2015.08.003

- Pietersma, S., & Dijkstra, A. (2010). Cognitive self-affirmation inclination: An individual difference in dealing with self-threats. British Journal of Social Psychology, 51, 33–51. doi:10.1348/014466610X533768

- van’t Riet, J., & Ruiter, R. A. C. (2013). Defensive reactions to health-promoting information: An overview and implications for future research. Health Psychology Review, 7, S104–S136. doi:10.1080/17437199.2011.606782

- Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Ruiter, R. A. C., Abraham, D., & Kok, G. J. (2001). Scary warnings and rational precautions: A review of the psychology of fear appeals. Psychology & Health, 16, 613–630. doi:10.1080/08870440108405863

- Schubert, S. J., Lee, C. W., & Drummond, P. D. (2011). The efficacy and psychophysiological correlates of dual-attention tasks in eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR). Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 25, 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.06.024

- Shapiro, F. (1999). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) and the anxiety disorders: Clinical and research implications of an integrated psychotherapy treatment. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 13, 35–67. doi:10.1016/S0887-6185(98)00038-3

- Schmeichel, B. J. (2007). Attention control, memory updating, and emotion regulation temporarily reduce the capacity for executive control. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 136, 241–255. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.136.2.241

- Siero, F. W., Huisman, M., & Kiers, H. A. L. (2009). Voortgezette regressie en variantieanalyse [Advanced regression and variance analysis]. Houten: Springer Media.

- Sweeney, A. M., & Moyer, A. (2015). Self-affirmation and responses to health messages: A meta-analysis on intentions and behavior. Health Psychology, 34, 149–159. doi:10.1037/hea0000110

- Symons, C. S., & Johnson, B. T. (1997). The self-reference effect in memory: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 121, 371–394.

- Tykocinski, O., Higgins, E. T., & Chaiken, K. (1994). Message framing, self-discrepancies, and yielding to persuasive messages: The motivational significance of psychological situations. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20, 107–115. doi:10.1177/0146167294201011

- Wheeler, S. C., Briñol, P., & Hermann, A. D. (2007). Resistance to persuasion as self-regulation: Ego-depletion and its effects on attitude change processes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43, 150–151. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2006.01.001

- Witte, K. (1992). Putting the fear back into fear appeals: The extended parallel process model. Communications Monographs, 59, 329–349. doi:10.1080/03637759209376276

- Yzerbyt, V. Y., Muller, D., & Judd, C. M. (2004). Adjusting researchers' approach to adjustment: On the use of covariates when testing interactions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 40, 424–431.