Abstract

Objective: Individual goals of health information seeking have been widely neglected by previous research, let alone systematically assessed. The authors propose that these goals may be classified on two dimensions, namely coping focus (problem versus emotion oriented) and regulatory focus (promotion versus prevention oriented).

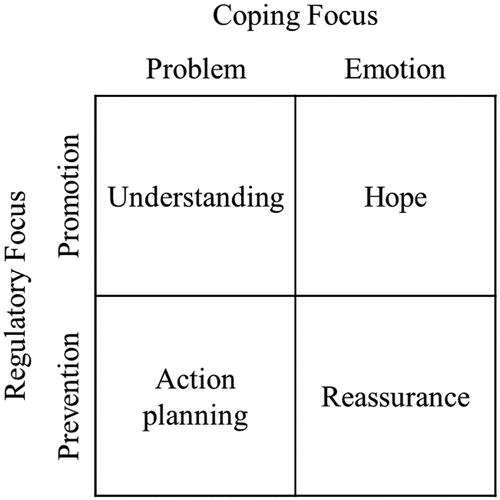

Methods: Based on this classification, the authors developed the 16-item Goals Associated with Health Information Seeking (GAINS) questionnaire measuring the four goals ‘understanding’, ‘action planning’, ‘hope’ and ‘reassurance’ on four scales, and a superordinate general need for health information. Three studies were conducted to assess the psychometric properties of the questionnaire.

Results: In the first two studies (N = 150 and N = 283), internal consistency of the scales was acceptable to very good, and all items had a satisfying discriminatory power. Factorial validity was corroborated by an acceptable model fit in confirmatory factor analyses. In the third study, which included a patient sample (N = 502), the questionnaire proved to be suitable for its target group and nomological relationships with personality as well as with situational variables providing evidence for construct validity.

Conclusion: The GAINS is a reliable and valid assessment tool, which enables researchers and practitioners to identify an individual’s goals related to health information seeking.

Introduction

Experiencing health-related symptoms, suspecting a health problem, or even receiving a professional diagnosis may lead to feelings of uncertainty, especially if a person feels a lack of information. In this case, an information need arises (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984). This information need can be satisfied by referring to prior (health) knowledge or through the acquisition of appropriate health information from suitable health information sources (Garneau et al., Citation2011). In the latter case, source-inherent features, situational aspects, and especially individual differences are pivotal for the choice of an information source and for the shaping of the information search process (Gray, Klein, Noyce, Sesselberg, & Cantrill, Citation2005; Lambert & Loiselle, Citation2007). In other words, the person x situation-interaction is crucial in determining the ideal source of information.

Although individuals’ information needs have been shown to significantly impact the information search process (Cole, Citation2011; Lu & Yuan, Citation2011; Savolainen, Citation2017; Wilson, Citation1981), interindividual differences regarding such needs as well as their dependence on situational demands have been widely neglected in the existing research literature. Accordingly, the goals of information seeking behaviour are commonly operationalised uniformly and are mostly assessed as a unidimensional construct in terms of a unidirectionally quantifiable information need (Lu & Yuan, Citation2011; Moerman, van Dam, Muller, & Oosting, Citation1996; Terpstra, Zaalberg, Boer, & Botzen, Citation2014). Some studies apply a more context-sensitive approach and investigate the ‘information need’ for a specific type of information, such as information about cancer or fibromyalgia (Daraz, MacDermid, Wilkins, Gibson, & Shaw, Citation2011; Mesters, van den Borne, De Boer, & Pruyn, Citation2001). Still, individual needs and goals are left out in such approaches, too.

Given the uncertainty that is associated with an information need, the search process can be seen as a certain form of coping. For example, during a threatening situation, adequate health information can support proper coping with feelings of helplessness (Damian & Tattersall, Citation1991; Muusses, van Weert, van Dulmen, & Jansen, Citation2012; Rutten, Arora, Bakos, Aziz, & Rowland, Citation2005). Moreover, depending on personal characteristics, differing information or representations of information may serve specific coping goals (Rutten et al., Citation2005). For example, individuals who prefer problem-focused coping (Folkman & Lazarus, Citation1980) directly address the situation by seeking information on direct interceding actions in order to support dealing with the health problem (Carver, Scheier, & Weintraub, Citation1989). On the other hand, individuals with an emotion-focused coping style (Folkman & Lazarus, Citation1980) prefer information which, for example, provides reassurance by showing that in the majority of cases, their symptoms can be considered harmless.

Hence, we argue that there is a general neglect of the consideration of coping and individual goals in the research of health-related information behaviour. For this reason, we developed a short self-report instrument, the ‘Goals Associated with Health Information Seeking’ (GAINS) questionnaire, which measures the specific goals of an individual’s information seekingFootnote1. The GAINS primarily assesses dispositional tendencies to pursue specific goals in the context of health information seeking, which may, however, interact with particular situational circumstances. These goals thereby can be assessed in every considerable health context and may not only vary inter- but also intra-individually, depending on the situation. With this, we rely on prior research regarding performance goal development and goal orientation that explicitly differentiates between dispositional (trait) and situational (state) goal orientations (see Payne, Youngcourt, & Beaubien, Citation2007, for a meta-analysis). Thus, we imply that in health information seeking, there are general, relatively stable tendencies to pursue certain goals as well as highly situation-dependent goals that can mainly be ascribed to a specific health context. As with other instruments measuring traits and states (e.g. the PANAS scales measuring state or trait positive and negative affect, Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, Citation1988), the questionnaire instruction can be adapted accordingly.

Several benefits of the new questionnaire are conceivable. First, on a conceptual level, the questionnaire allows researchers to find out more about health information-related cognitions, needs and motivations. Second, with regard to patient outcomes, patients and their relatives may be offered tailored information with respect to their individual needs (Young, Tordoff, & Smith, Citation2017). Third, the questionnaire may be used to tailor information literacy interventions to specific patient groups, and finally, it may even take part in improving the overall information design in health contexts (e.g. by providing information that is in line with common needs and goals of information users).

Theoretical background

To identify the individual goals of information seeking, it is important to consider the context in which the search for information takes place. In health contexts, goal-oriented information seeking may be interpreted as a way of coping with situations that are perceived as threatening (Lambert & Loiselle, Citation2007; Shiloh & Orgler-Shoob, Citation2006; van der Molen, Citation1999). The broad and well-known concept of coping encompasses an individual’s efforts to prevent or deal with distress, harm, or threat (Carver & Connor-Smith, Citation2010). When considering different foci of coping behaviour, the well-established distinction between problem- and emotion-focused coping initially proposed by Folkman and Lazarus (Citation1980) is particularly prominent. A problem-focus is characterised by aiming at tackling and eliminating the problem itself, for example, by understanding its causes and making plans of action (Littleton, Horsley, John, & Nelson, Citation2007). In contrast, emotion-focused strategies primarily aim at improving emotional well-being (e.g. reduce distress caused by the problem).

Hence, on this basis, two potential goal categories of health information seeking can be identified: emotion-related and problem-related goals. One might wonder: Do I need information because I want to feel better about the health problem, or because I want to overcome my health problem, or both? However, further differentiation between potential goals is necessary in order to indicate the goals individuals pursue when confronted with the respective problem and/or emotion they aim to deal with. Regulatory focus theory (RFT; Higgins, Citation1987, Citation1997) postulates two opposed motivational systems that, according to one of the two main conceptualisations of the theoryFootnote2, either strive to maximise positive outcomes (promotion focus) or to minimise negative outcomes (prevention focus). A promotion focus constitutes the regulation towards a desirable end-state and away from the absence of such a state. A prevention focus describes a regulation focus directed at taking care of staying away from undesirable states and/or approaching a state that is not undesirable. In this respect, it is important to note that prevention and promotion focus are not merely different designations for behavioural avoidance and approach tendencies. Both regulatory foci may serve avoidance goals as well as approach goals and may also lead to avoidance as well as to approach behaviour (Higgins, Citation1997); Summerville & Roese, Citation2008). Differences in these regulatory foci (e.g. due to personality or situational influences) were found to predict goals as well as goal-seeking strategies (Strauman, Citation1996). Therefore, RFT may also provide a useful framework to capture the goals individuals have when they are confronted with a health problem. This is especially true since the theory has already been applied numerous times in the context of health behaviour and health message framing (e.g. Bergvik, Sørlie, & Wynn, Citation2010; Dijkstra, Rothman, & Pietersma, Citation2011; Yi & Baumgartner, Citation2009). Bergvik et al. (Citation2010), for example, investigated the prevalence of such regulatory foci in surgery patients and found, among others, evidence that the foci reveal themselves in different goals.

Thus, alongside problem- vs. emotion-focused goals, it is advisable to differentiate between promotion- and prevention-focused goals individuals may pursue when seeking health information. Integrating these two superordinate categorisations of goals into one framework results in a 2 × 2 matrix containing four goal types: problem-promotion, problem-prevention, emotion-promotion and emotion-prevention. Consequently, we derived four scales with which our questionnaire should capture these four goal types (see ). The first scale, ‘Understanding’, addresses the goal to identify causes and consequences of a health problem. It is thus problem- as well as promotion-focused, as the goal is to deal with the health problem via enhancing one’s understanding and knowledge. The second scale, ‘Action planning’, measures the goal to determine tangible, situation adequate courses of action to prevent a further worsening of the problem. Hence, it is problem-focused, but unlike the ‘Understanding’ scale, also prevention-focused: the goal here is to deal with the problem via minimising the likelihood of health deterioration through protective efforts. The third scale is labelled ‘Hope’ and assesses the goal to activate personal emotional resources. It is therefore emotion- as well as promotion-focused since it aims at dealing with one’s emotions via increasing positive emotional states such as hope and trust. ‘Reassurance’ constitutes the fourth scale measuring the goal to reduce negative emotions like anxiety. It is therefore emotion- as well as prevention-focused as it aims to deal with emotions via reducing distress.

To sum up, the four scales of the GAINS measure four goals individuals may pursue when seeking health information: understanding, action planning, hope, and reassurance. It is important to note that it is also possible to have more than one goal at a time (Case, Andrews, Johnson, & Allard, Citation2005). Besides measuring four distinct goals, the GAINS also aims at quantifying an individual’s need for health information in general. This is achieved by referring to the sum score across all scales.

In this article, we report three studies that investigated the psychometric properties of the GAINS. The first two studies were conducted with the intention of examining the overall suitability of the questionnaire (i.e. item characteristics, internal consistency, structural validity, situational sensitivity). Thus, in Study 1, we focused on item characteristics and selected appropriate items for a final version, and, after that, we analysed the internal consistency of the final scales and examined the proposed factor structure of the questionnaire (four factors representing four goals of health information seeking). In Study 2, we aimed to replicate the factor structure from Study 1 within a larger sample, and to further validate our instrument in terms of sensitivity to situational influences, that is, to a varying degree of threat. In Study 3, we analysed construct validity in a larger sample constituting the questionnaire’s target group. Therefore, the sample in Study 3 was approximately representative for the general population with regard to age and sex and consisted of individuals experiencing a health problem who exhibited a resulting information need.

Study 1

Our first study aimed at the initial development and structural validation of the GAINS. For this reason, the wording of the questionnaire’s instructions was very general and independent from a specific health context in this study, as we asked participants to refer to the goals they usually had pursued in the past when seeking health information. With this, we were also able to test if the GAINS was suitable to measure dispositional, trans-situational goals. We analysed item characteristics (means, variances and discriminatory power), estimated the scales’ internal consistencies, and assessed the questionnaires’ factorial structure. According to our theoretical assumptions, we expected a confirmatory factor model with five latent variables (four first order-factors representing the four goals measured by the GAINS and one second-order factor representing a general need for health information) to yield an acceptable or better data fit. Furthermore, we expected this model to fit considerably better than three alternative models. The first two alternative models comprise only two (instead of five) latent factors representing (1) problem- and emotion-focused goals or (2) promotion- and prevention-focused goals. The third alternative model includes one single latent factor representing a general health information need.

Methods

Item construction

The initial approach involved the first two authors to formulate basic items for each subscale in collaborative brainstorming sessions, based on the theoretical derivation of the components of the four goals. These items were a starting point for the development of further items, made separately by the authors. By this means, a larger item pool was assembled, which however included a large number of redundancies. A selection of these items was made through a joint discussion by all four authors as to which items are most likely to represent the theoretical dimensions. Ultimately, this led to an item pool of 19 items. This approach is a mixture of the concepts of intuitive and rational construction (Jonkisz, Moosbrugger, & Brandt, Citation2012), as the construction of the items is equally based on intuition and experience from the authors, as well as on a deduction from related theories. The 19 items represent the four scales ‘Understanding’ (four items), ‘Action planning’ (four items), ‘Hope’ (six items) and ‘Reassurance’ (five items).

Sample

According to a Monte Carlo simulation study by Muthén and Muthén (Citation2002), a sample size of minimum N = 100 to 150 participants would be sufficient for our purpose. Thus, we decided to recruit 150 participants. Data were collected in an online study on health information behaviour. Participants were recruited via a mailing list of a large German university as well as via Facebook groups aimed at recruiting subjects for psychological studies. The minimum age limit for participation was 18 years. The final sample included N = 150 participants, with an age range from 19 to 60 years and a mean age of 27.13 (SD = 7.27) years. Sixty-seven percent (n = 100) of the participants were females and with regard to educational level, 93.8 percent (n = 141) had at least the German high school diploma-equivalent (‘Abitur’). Thus, our sample was rather young and highly educated.

Materials and procedure

Alongside other questionnaires related to a different research question, participants completed the newly developed GAINS questionnaire. In the instruction, they were requested to evaluate, on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree), whether they usually had pursued the respective goal when seeking for information concerning health problems in the past. Survey completion took around 90 minutes, and participants received 15 € as compensation.

Results

Item characteristics and confirmatory factor analysis

For practical reasons, we aimed to reach an equal number of items (i.e. four) per scale. Thus, one item from the ‘Reassurance’ and two items from the ‘Hope’ scales had to be eliminated. We thereby decided to exclude the items that would provide the lowest discriminatory power. Accordingly, in the ‘Hope’ scale, the items with the lowest discriminatory power (‘…to regain courage despite the problem.’, .74 and ‘…to remain as carefree as possible despite the problem.’, .68) were eliminated. Since the discriminatory power of the two lowest-ranking items in the ‘Reassurance’ scale was extremely similar (.66), we decided to eliminate the item ‘…to feel more relieved at the thought of the problem.’ because it is redundant to another item with a better discriminatory power and a (subjectively) higher readability (‘to be more relaxed about the health problem.’). By retaining the other item, the complexity of the construct as a whole is also better represented. For the remaining 16 items, item means were moderate to high (2.85 to 4.35 on a 1–5 rating scale) and standard deviations ranged from 0.63 to 1.24. The discriminatory power of all items was satisfactory (rit > .50). Internal consistencies of the four scales and the overall scale were acceptable to very good (Cronbach’s Alphas: .68 for ‘General information need’, .80 for ‘Understanding’, .85 for ‘Action Planning’, .90 for ‘Hope’, and .85 for ‘Reassurance’).

Hence, 16 items were retained and included in the subsequent confirmatory factor analysis, which we conducted using the R-package lavaan (Rosseel, Citation2012). In a first step, we tested our proposed model (Model 1) with four latent factors representing the four subscales, and one latent second-order factor representing a general need for health information. For theoretical reasons, we allowed covariation between the two problem-focused and the two emotion-focused goals as well as between the two promotion-focused and the two prevention-focused goals in Model 1. This was because there are additional determinants besides the general need for health information that would contribute to their covariation (e.g. personality characteristics associated with a problem- or emotion focused coping style or a specific regulatory focus). Additionally, we assumed the latent goal factors to have a balanced impact on the second-order factor (general health information need), which is why we fixed their respective path coefficients to being equal.

According to the rules of thumb for model evaluation provided by Schermelleh-Engel, Moosbrugger, and Müller (Citation2003), this model provided an acceptable fit (χ2 = 140.74, df = 99, p < .05, RMSEA = .054, CFI = .97, SRMR = .068, AIC = 5654.93, BIC = 5765.57). The first alternative model (Model 2) had two latent factors representing problem- and emotion-focused goals. These goals were measured by combining the ‘Understanding’- and ‘Action planning’-items (problem focus) and the ‘Hope’- and ‘Reassurance’-items (emotion focus) into two factors. The second alternative model (Model 3) had two latent factors representing promotion- and prevention-focused goals. In this model, the ‘Understanding’- and ‘Hope’-items (promotion focus) and the ‘Action planning’- and ‘Reassurance’-items (prevention focus) were combined, respectively. The third alternative model (Model 4) was a single factor model representing a general and undifferentiated need for health information that was measured by all 16 items. All three alternative models yielded an insufficient fit, and the magnitude of the AIC and BIC differences from the proposed model suggested its superiority in the present sample (Symonds & Moussalli, Citation2011; Wagenmakers, Citation2007). depicts the four tested models with their respective fit measures. In sum, the first study provides initial empirical evidence for the reliability as well as for the structural validity of the GAINS.

Table 1. Fit-indices of different factor structure SEM estimations of the GAINS.

Study 2

For one, the aim of Study 2 was to replicate the results of Study 1. Hence, we expected satisfactory internal consistencies of all scales and an at least acceptable fit of our proposed model in a confirmatory factor analysis (structural validity).

Our second aim was to examine if the GAINS would prove sensitive to situational circumstances and thereby could, in addition to assessing rather dispositional goal orientations, also measure highly situation-dependent goals. Therefore, different from Study 1, participants were now explicitly instructed to refer to the information goals they would have when undergoing a portrayed health problem scenario. Then, we analysed the capability of the instrument to discriminate between individuals depending on the perceived seriousness of the described health problem. We expected that individuals would not differ in their preference for prevention goals depending on the severity of the health threat, but in their preference for promotion goals. This means that individuals confronted with a severe health threat may be more inclined to pursue promotion goals than individuals confronted with a moderate threat. In fact, prevention goals are activated when at least a moderate threat is anticipated (Higgins, Citation1997; Oyserman, Uskul, Yoder, Nesse, & Williams, Citation2007). However, because with a moderate danger present they are already highly expressed, we assumed that such goals are unlikely to further increase with a growing threat. In contrast, promotion goals like gaining hope or understanding the cause of the threat become much more relevant if the threat is high compared to moderate, as is also reflected in the counter-regulation hypothesis by Rothermund, Voss, and Wentura (Citation2008).

Methods

Sample

Data collection was conducted during a study on health information behaviour and carried out at a large Germany university. Participants were recruited via a university mailing list as well as via flyers at the university campus. The minimum age limit for participation was 18 years and participants were required to be enrolled as university students. The final sample included N = 283 participants, with an age range from 18 to 46 years and a mean age of 23.53 (SD = 3.25) years. 80.6% (n = 228) of the participants were females.

Materials and procedure

The second study was part of a larger study and was divided into two parts: an online survey (about 30 minutes) and a supervised group session with a maximum of 30 participants. The second part took about 90 minutes and included our experimental study. As compensation, participants received 30 € in cash. In this study, the final (16-item) version of the GAINS was employed. Internal consistency of the four scales as well as of the overall score were satisfactory to good (Cronbach’s Alpha = .74 to .89). Before applying the GAINS, we experimentally manipulated the perceived health threat by randomly assigning participants to one of two experimental conditions. These conditions differed in the severity of a short health scenario which was presented in written form at the beginning of the experiment. Participants were instructed to familiarise with the described situation and fill out the GAINS as if they themselves actually had to live through the portrayed situation. Participants from the first group (‘moderate threat’) were instructed to imagine that they would experience some unspecific breast pain that, however, would not considerably impact their everyday life and functioning. In contrast, participants from the second group (‘severe threat’) were presented with a scenario in which they would experience acute breast pain and breathing troubles, resulting in marked constraints for their functioning. As a manipulation check, participants rated the perceived threat of the respective scenario on a scale from 0 (no threat) to 100 (maximum possible threat). A t-test for independent samples revealed our manipulation to be effective (M = 39.01 and SD = 20.57 in the ‘moderate threat’ condition vs. M = 61.15 and SD = 21.56 in the ‘severe threat’ condition, t(281) = 8.84, p < .001).

Results

Structural validity

In order to further corroborate the structural validity of the GAINS, the factor structure was estimated in the second sample just like in Study 1. Again, we fixed the path coefficients of the first-order latent goal factors on the second-order factor to be equal. Model fit was acceptable (χ2 = 217.79, df = 99, p < .05, RMSEA = .065, CFI = .94, SRMR = .055; see , Model 1 b), implying a successful replication of the GAINS’ structure in an independent sample.

Sensitivity to situational influences

To assess the situational sensitivity of the GAINS, we conducted a MANOVA with threat condition (moderate vs. severe) as independent variable and the four goal scales as dependent variables. The multivariate effect was significant with Pillai’s trace = .059, F(4, 278) = 4.38, p < .01. The univariate F-tests showed that threat severity had a significant positive impact on the promotion goal ‘Understanding’ (F(1, 281) = 5.55, p < .05, partial η2 = .02). The descriptively positive effect of threat severity on the promotion goal ‘Hope’ was, contrary to our expectations, not significant (F(1, 281) = 3.78, p = .06, partial η2 = .01). Thus, an increase of threat seems to increase promotion goals – at least with regard to ‘Understanding’. As expected, threat severity had no significant impact on prevention goals (‘Action planning’: F(1, 281) = 1.47, p = .23; ‘Reassurance’: F(1, 281) = 0.91, p = .34).

Study 3

Our third study had two objectives. First, we intended to replicate our findings from the first two studies with regard to item characteristics, internal consistencies and structural validity in a larger sample. To further increase the generalisability of our results, we strived for a sample that would (a) be approximately representative of the general population with regard to age and gender, and (b) consist of individuals who currently experienced an actual health problem and a resulting information need. With this, we would be able to ascertain that the instrument may be applied to its genuine target group.

The second objective of Study 3 was to analyse the GAINS’ construct validity. For this reason, we developed hypotheses about the relationship between the GAINS scales and other constructs in a comprehensive nomological network.

First, we predicted all scales to positively correlate with the reported level of worry about the health problem as we assumed that increased worry leads to a higher personal relevance of the goals that health information may serve (Lee & Hawkins, Citation2016; Myrick, Willoughby, & Verghese, Citation2016; Yang & Kahlor, Citation2013).

Second, we expected a single item capturing the current information needed to correlate positively with the GAINS total score – which we meant to represent a general information need.

Third, we assumed that both problem-focused goal scales (‘Understanding’ and ‘Action planning’) would be positively associated with the perceived ability to find, analyse, understand and use relevant health information (health information literacy; Shipman, Kurtz-Rossi, & Funk, Citation2009). We will further refer to this perceived ability as ‘health information seeking self-efficacy’. With regard to the ‘Understanding’ scale, this is because individuals who have confidence in their capability to understand and make use of health information (i.e. whose self-efficacy is more pronounced) should more likely be motivated to understand the specific health problem in detail. Accordingly, research consistently finds general and domain-specific self-efficacy being positively associated with persistence and effort (Scholz, Doña, Sud, & Schwarzer, Citation2002; Zimmerman, Citation2000). Furthermore, with regard to ‘Action planning’, individuals who perceive themselves as health literate may be more willing to plan further action with the help of the retrieved information since they believe in their ability to adequately deal with it.

Fourth, the general individual disposition for having a promotion or prevention regulatory focus should correlate positively with a situationally sensitive, but dispositionally embedded preference of a corresponding domain-specific goal (namely, a health information seeking goal).

Methods

Sample

Our sample was approximately representative for the general population in Germany with regard to age and gender. It was acquired online via the CINT Access panel, in which participants were invited according to age group and gender quotas that represented the original distribution of these characteristics in the general population in Germany. The final sample consisted of N = 502 individuals with an age range from 18 to 74 years and a mean age of 45.24 years (SD = 13.94). Fifty-six percent were females and 39.8% had at least the German high school-diploma equivalent (‘Abitur’), which is a slightly higher proportion than in the general German population (about 32%; German Federal Statistical Office, Citation2017). A precondition for participation was the experience of a disease or another health problem within the past four weeks (maximum), and, at the same time, a need for information with regard to this issue. The most frequently mentioned health complaints were related to the muscoskeletal system (e.g. back pain, knee problems), mental health (e.g. depression, anxiety and eating disorders) and the cardiovascular system (e.g. hypertension, cardiac insufficiency).

Materials and procedure

The study was designed as an online survey that took about 15 minutes to complete and was conducted by a professional panel-based data collection service. The final (16-item) version of the GAINS was employed. Internal consistency of the four scales as well as of the overall score was good (Cronbach’s Alpha = .80 to .89). After completing the GAINS, to examine construct validity, participants responded to several questionnaires and single item questions (see below). Additionally, before administering the GAINS, we included questions about the nature and duration of the health problem, the perceived knowledge regarding the health problem (single item), and diagnosis (if applicable).

Information need and worry about the health problem

Information need was measured by a single item asking participants to rate their information need with regard to their health problem on a scale from 0 (very low information need) to 100 (extremely high information need). Mean information need was M = 71.95 (SD = 24.90). We also asked how worried participants were about their health problem, which they could rate on a scale from 0 (not worried at all) to 100 (extremely worried). For this item, the mean was M = 53.95 (SD = 27.84).

Health information seeking self-efficacy

To assess health information seeking self-efficacy, we adapted the Self-Efficacy Scale for Information Searching Behaviour (SES-IB-16) by Behm (Citation2015) with regard to the context of health information. The questionnaire consists of 16 items that are scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = does not apply at all, 5 = fully applies). With Cronbach’s Alpha of .91, internal consistency was very good.

Regulatory focus

As suggested by Yi and Baumgartner (Citation2009), the individual dispositions for behavioural inhibition (BIS) and behavioural activation (BAS) may serve as a proxy for regulatory focus (see also Leone, Perugini, & Bagozzi, Citation2005; Mann, Sherman, & Updegraff, Citation2004). Regulatory focus was thus measured by the short German version of an instrument assessing BIS and BAS established by Carver and White (Citation1994). This version, called ARES-K, was developed by Hartig and Moosbrugger (Citation2003) and contains 20 items, with 10 items measuring BIS or BAS, respectively. The items are scored on a 4-point Likert scale, with 1 indicating strong disagreement and 4 indicating strong agreement. Cronbach’s Alpha of both scales was good to very good, with α = .94 for the BIS scale and α = .82 for the BAS scale.

Results

Item characteristics and structural validity

Just like in our initial construction study (Study 1), item characteristics were satisfactory. Item means were moderate to high (3.59 to 4.23 on a 1–5 scale) and the lowest standard deviation was .86. Item discriminatory power (item-total correlation) ranged from .51 to .72 in the general information need scale and from .50 to .81 in the four subscales (i.e. the goal scales).

For the purpose of further corroborating the proposed factor structure of the GAINS, we conducted another confirmatory factor analysis in this third sample. Again, we fixed the path coefficients of the first-order latent goal factors on the second-order factor to be equal. Model fit was acceptable (χ2 = 269.064, df = 99, p < .05, RMSEA = .058, CFI = .96, SRMR = .052; see , Model 1c), implying a successful replication of the instrument’s factor structure.

Construct validity

Construct Validity was tested by means of Pearson correlations between the GAINS and the subscales BIS and BAS of the ARES-K, the SES-IB-16 and the two single items measuring worry and information need (see ). As hypothesised, worrying about the health problem positively correlated with all four goals. Moreover, again in accordance with our expectations, information need positively correlated with the GAINS total score. Regarding the SES-IB-16 (health information seeking self-efficacy), as expected, statistically significant and positive correlations were found for the overall score as well as for the problem focus goals ‘Understanding’ and ‘Action planning’. Moreover, in terms of discriminant validity, the two other subscales (‘Reassurance’ and ‘Hope’) showed no significant correlations with the SES-IB-16. The expected positive correlation between the prevention goal ‘Reassurance’ and BIS was significant, just as the correlation between the promotion goal ‘Understanding’ and BAS. Again, in terms of discriminant validity, we found no statistically significant correlations between ‘Reassurance’ and BAS and ‘Understanding’ and BIS. However, contrary to our expectations, the second prevention goal, ‘Action Planning’, did not correlate with BIS (but with BAS), and the second promotion goal, ‘Hope’, did not correlate with BAS (but with BIS).

Table 2. Correlations, means and standard deviations of the GAINS scales, ARES-K scales, SES-IB, Worry and Information Need in Study 3.

General discussion

The GAINS questionnaire aims to measure individual goals of health information seeking on the four scales ‘Understanding’, ‘Action planning’, ‘Hope’ and ‘Reassurance’, as well as a general need for health information (mean score across the scales). In three independent studies, we analysed the psychometric properties of the instrument. Study 1, an online study using a generally formulated, situation-independent instruction, showed that all items had a satisfactory discriminatory power, and provided first evidence for the reliability of the instrument. Furthermore, the proposed factor model yielded an acceptable fit and was clearly superior to three alternative models. These results were corroborated in Study 2, which included a university student sample and used a situation-specific instruction referring to an experimentally manipulated health threat. Here again, adequate scale reliabilities and an acceptable fit of the proposed factor structure were found. In Study 3, we analysed a sample from the target population of the GAINS which was approximately representative for the German general population with regard to age and gender. This sample constituted of individuals who currently suffered from a health problem and had a resulting information need. Here, too, our analyses revealed adequate item characteristics and internal consistencies, as well as a satisfactory fit of the proposed factor model.

While the questionnaire proved reliable and structurally valid in all three studies, we also found evidence for its construct validity in Study 3. Worrying about one’s health problem(s) correlated significantly with all scales, and a single item capturing participants’ current information need was positively associated with the GAINS total score (which we proposed to measure a general information need). Moreover, the problem-focus scales correlated with self-efficacy beliefs regarding health information seeking. This supports construct validity since individuals who have confidence in their information seeking capability are more likely to adopt an (usually more challenging) problem-orientated search. The very low (even insignificant) correlations of self-efficacy beliefs with both emotion-focus scales further corroborate construct validity in terms of discriminant validity - which is in line with our expectations since the regulation of one’s emotions is only very loosely connected to an achievement-oriented variable such as self-efficacy. Furthermore, in accordance with our theoretical assumptions, the promotion-focus goal ‘Understanding’ significantly correlated with our measure for a predisposition promotion focus (BAS), and the prevention-focus goal ‘Reassurance’ correlated with the prevention equivalent (BIS). Finally, the GAINS was, overall, sensitive to experimental variations of the perceived health threat (Study 2).

However, contrary to our expectations, there were no associations between ‘Action planning’ and BIS, and ‘Hope’ and BAS, but instead between ‘Action planning’ and BAS and ‘Hope’ and BIS (see ). This might be due to theoretical reasons: As Strauman and Wilson (Citation2010) point out, BAS and BIS on one side, and a specific regulatory focus (prevention vs. promotion) on the other side, should be conceived on different levels of approach and avoidance motivation. BAS and BIS represent dispositional, fundamental approach and avoidance temperaments (Carver, Citation2005) and are therefore more closely related to actual behaviour (Elliot & Thrash, Citation2002). Regulatory focus, on the other hand, predicts the preference for a specific strategy when pursuing an approach or avoidance goal (with the strategies differing in their respective reference points in goal regulation; Summerville & Roese, Citation2008). Hence, it is conceivable that a prevention focus may lead to approach behaviour if this serves the superordinate goal of reducing a threat. For example, in the case of ‘Action planning’, the prevention focus (averting danger) may direct approach behaviour such as initiating specific actions in dealing with the danger. Thus, essentially, behavioural approach and avoidance tendencies (as captured by the BIS and BAS measures), regulatory focus and approach/avoidance goals may be interrelated, but cannot be regarded as interchangeable designations of the same construct- which might explain why not all our expectations regarding the respective correlations were supported by our data. While we were relying on the literature suggesting BIS and BAS as valid proxies for prevention and promotion foci (e.g. Yi & Baumgartner, Citation2009; Mann et al., Citation2004), we therefore must conclude that in our case, a more sophisticated approach to validate prevention and promotion focus might have been indicated, especially since a clear distinction between approach/avoidance behavior, goals, and promotion/prevention regulatory focus is crucial for our purposes. Hence, concerning the further analysis of construct validity, future studies additionally should assess the relationship between the GAINS scales and regulatory focus directly, for example, via message framing experiments (Hevey & Dolan, Citation2014) and by using more appropriate questionnaires (see below).

A direct consequence of the denoted issue is that, overall, our results concerning construct validity mainly support differentiating between coping foci, but not necessarily between regulatory foci in health information seeking goals. However, the four factor-solution exhibited a much better fit than the two factor-solution that would come into question when dropping the regulatory focus dimension. In addition, all four scales are theoretically well-founded with regard to their unique meaning in health information seeking (see, e.g. Dickerson, Boehmke, Ogle, & Brown, Citation2006 about gaining hope as motivation in searching for information about cancer care). Thus, the theoretical framework of the GAINS represented by a 2 × 2 matrix (see ) could be adapted by eliminating the regulatory focus dimension while keeping all four scales. However, before taking this step, the framework first has to be tested more appropriately with regard to regulatory focus (as discussed above) to base this decision on more solid grounds. We therefore decided to nevertheless retain the regulatory focus dimension, but advise caution regarding its insufficient empirical testing.

One further limitation concerns (the lack of) additional reliability and validity testing. Although internal consistencies were satisfactory in all three studies, future studies should investigate the test-retest reliability of the GAINS to corroborate reliability. Additionally, criterion validity has yet to be assessed. To date, it is unclear if the GAINS can predict actual information behaviour or the actual pursuit of certain goals. For further evaluation of criterion validity, a relevant external criterion (e.g. observed information behaviour) has to be included in subsequent studies. As for concurrent validity, a possible solution would be to assess positive and negative affect before and after information seeking, and compare a potential emotional shift with the results of the GAINS. In terms of prognostic validity, actual behaviour and change in affect after a given time could be an appropriate implementation for future research.

In addition to the connection to actual behaviour, better instruments for the associated validation constructs, in terms of their contextual and theoretical fit, would be useful for further validation efforts. Thus, in future studies, we plan to include additional questionnaires measuring coping tendencies, such as the COPE inventory (Litman, Citation2006), as well as questionnaires measuring dispositional promotion and prevention regulatory focus using a reference-point definition (Summerville & Roese, Citation2008), like the general regulatory focus measure (GRFM; Lockwood, Jordan, & Kunda, Citation2002). Furthermore, scrutinising the relationship between the GAINS scales and actual health problems would significantly contribute to the analysis of construct validity. We would expect varying grades of markedness of every single information seeking goal depending on the perceived severity of and mere susceptibility to a health problem. Here, conducting a quasi-experimental investigation with varying severity of and susceptibility to a health problem (e.g. using a 2 × 2 design) would constitute a promising approach to further investigate construct validity. Subsequently, to integrate our approach into a broader theoretical framework of health behaviour, relationships between the GAINS and questionnaires measuring cognitive and/or behavioural aspects of health behaviour could be established. Regarding the Transtheoretical Model of Behavior Change (TTM; Prochaska & DiClemente, Citation1983), for example, one could explore mediating effects by the GAINS scales with regard to the association between the ‘contemplation’ and the ‘preparation’ or ‘action’ stages: Depending on their preferred information seeking goal(s), individuals may come to different conclusions with regard to the kind of potential changes in their health behavior they may adapt.

Another future research direction concerns our aspiration to measure dispositional as well as situation-specific health information seeking goals by adapting the instruction accordingly, depending on the respective focus of interest. In the three studies reported in this article, we introduced both approaches, using a generally phrased instruction in Study 1 (relating to usually pursued goals) and situation-related instructions in Studies 2 and 3. However, there is more research needed as to the justification of differentiating between trait and state goals in the area of health information seeking, and thus, of using different instructions when applying the GAINS. Longitudinal designs in which the GAINS is applied with different instructions (trait vs. state) across varying experimental conditions may constitute a promising approach in this respect.

In sum, the GAINS questionnaire was demonstrated to be a reliable and empirically valid instrument that makes a unique contribution to the interdisciplinary fields of health psychology, health communication, and medical psychology. The new questionnaire allows a comprehensive assessment of the goals that individuals pursue when searching for health information. The specific goals captured by the GAINS have a solid theoretical foundation and show the best statistical fit if they are estimated independently in a structural model. With regard to research applications, this makes the questionnaire an excellent choice for analysing individual differences in coping through health information seeking. The individual goal dimensions may aid the field in explaining variance in relevant outcomes, as well as in increasing the understanding of information search processes. Furthermore, at the interface between research and practice, the GAINS may help to design and improve specifically tailored information for various patient groups. Ultimately, identifying specific goals in health information seeking may even improve the coping and understanding process in patients, and lead to better health outcomes. Hence, the GAINS can be considered as an instrument of high value in a relatively broad field of application to a new and not yet wholly covered topic.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

Datasets are available on request. The raw data supporting the conclusions of this manuscript will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The questionnaire can be found in the original German version with an unverified English translation in a publicly accessible repository in the publicly accessible repository PsychArchives (https://www.psycharchives.org/handle/20.500.12034/560.2).

2 Higgins (Citation1997) introduces two conceptualisations of prevention and promotion regulatory foci which Summerville and Roese, (Citation2008) term ‘self-guide definition’ and ‘reference-point definition’. Throughout this article, when relating to the RFT, we refer to the reference-point definition, which distinguishes between the two regulation foci characterised by one of two possible reference end-states (‘gain’ or ‘loss’).

References

- Behm, T. (2015). Informationskompetenz und Selbstregulation: Zur Relevanz bereichsspezifischer Selbstwirksamkeitsüberzeugungen [Information competence and self-regulation: The relevance of domain-specific self-efficacy]. In A. K. Mayer (Ed.), Informationskompetenz im Hochschulkontext [Information competence in the higher education context.]: Interdisziplinäre Forschungsperspektiven [Interdisciplinary research perspectives] (pp. 151–162). Lengerich: Pabst Science Publishers.

- Bergvik, S., Sørlie, T., & Wynn, R. (2010). Approach and avoidance coping and regulatory focus in patients having coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Journal of Health Psychology, 15(6), 915–924. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105309359542

- Carver, C. S. (2005). Impulse and constraint: Perspectives from personality psychology, convergence with theory in other areas, and potential for integration. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 9(4), 312–333. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0904_2

- Carver, C. S., & Connor-Smith, J. (2010). Personality and coping. Annual Review of Psychology, 61(1), 679–704. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100352

- Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., & Weintraub, J. K. (1989). Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(2), 267–283. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.56.2.267

- Carver, C. S., & White, T. L. (1994). Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: The BIS/BAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(2), 319–333. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.67.2.319

- Case, D. O., Andrews, J. E., Johnson, J. D., & Allard, S. L. (2005). Avoiding versus seeking: The relationship of information seeking to avoidance, blunting, coping, dissonance, and related concepts. Journal of the Medical Library Association: JMLA, 93(3), 353–362.

- Cole, C. (2011). A theory of information need for information retrieval that connects information to knowledge. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 62(7), 1216–1231. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.21541

- Damian, D., & Tattersall, M. H. N. (1991). Letters to patients: Improving communication in cancer care. The Lancet, 338(8772), 923–925. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0140-6736(91)91782-P

- Daraz, L., MacDermid, J. C., Wilkins, S., Gibson, J., & Shaw, L. (2011). Information preferences of people living with fibromyalgia – a survey of their information needs and preferences. Rheumatology Reports, 3(1), 7. doi:https://doi.org/10.4081/rr.2011.e7

- Dickerson, S. S., Boehmke, M., Ogle, C., & Brown, J. K. (2006). Seeking and managing hope: Patients' experiences using the internet for cancer care: Patients' experiences using the Internet for cancer care. Oncology Nursing Forum, 33(1), E8–17. doi:https://doi.org/10.1188/06.ONF.E8-E17

- Dijkstra, A., Rothman, A., & Pietersma, S. (2011). The persuasive effects of framing messages on fruit and vegetable consumption according to regulatory focus theory. Psychology & Health, 26(8), 1036–1048. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2010.526715

- Elliot, A. J., & Thrash, T. M. (2002). Approach-avoidance motivation in personality: Approach and avoidance temperaments and goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(5), 804–818. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.5.804

- Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1980). An analysis of coping in a middle-aged community sample. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 21(3), 219–239. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2136617

- Garneau, K., Iversen, M., Jan, S., Parmar, K., Tsao, P., & Solomon, D. H. (2011). Rheumatoid arthritis decision making: Many information sources but not all rated as useful. Journal of Clinical Rheumatology: Practical Reports on Rheumatic & Musculoskeletal Diseases, 17(5), 231–235. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/RHU.0b013e318226a220

- German Federal Statistical Office (2017). Bildungsstand [Level of education]. Retrieved from https://www.destatis.de/DE/ZahlenFakten/GesellschaftStaat/BildungForschungKultur/Bildungsstand/Bildungsstand.html;jsessionid=06B1569627151DD09AC94028CC2B8AE1.InternetLive1

- Gray, N. J., Klein, J. D., Noyce, P. R., Sesselberg, T. S., & Cantrill, J. A. (2005). Health information-seeking behaviour in adolescence: The place of the internet. Social Science & Medicine, 60(7), 1467–1478. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.010

- Hartig, J., & Moosbrugger, H. (2003). Die “ARES-Skalen” zur Erfassung der individuellen BIS-und BAS-Sensitivität: Entwicklung einer Lang- und einer Kurzfassung [The ARES-Scales as a Measurement of Individual BIS- and BAS-sensitivity: Development of a Long and a Short Questionnaire Version]. Zeitschrift Für Differentielle Und Diagnostische Psychologie, 24(4), 293–310. doi:https://doi.org/10.1024/0170-1789.24.4.293

- Hevey, D., & Dolan, M. (2014). Approach/avoidance motivation, message framing and skin cancer prevention: A test of the congruency hypothesis. Journal of Health Psychology, 19(8), 1003–1012. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105313483154

- Higgins, E. T. (1987). Self-discrepancy: A theory relating self and affect. Psychological Review, 94(3), 319–340. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.94.3.319

- Higgins, E. T. (1997). Beyond pleasure and pain. American Psychologist, 52(12), 1280–1300. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.52.12.1280

- Jonkisz, E., Moosbrugger, H., Brandt, H. (2012). Planung und Entwicklung von Tests und Fragebogen [Construction and developmnent of tests and questionnaires]. In H. Moosbrugger & A. Kelava (Eds.), Testtheorie und Fragebogenkonstruktion [Test theory and questionnaire development] (pp. 27–74). Heidelberg, Germany: Springer.

- Lambert, S. D., & Loiselle, C. G. (2007). Health information seeking behavior. Qualitative Health Research, 17(8), 1006–1019. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732307305199

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer Publishing Company.

- Lee, S. Y., & Hawkins, R. P. (2016). Worry as an uncertainty-associated emotion: Exploring the role of worry in health information seeking. Health Communication, 31(8), 926–933. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2015.1018701

- Leone, L., Perugini, M., & Bagozzi, R. (2005). Emotions and decision making: Regulatory focus moderates the influence of anticipated emotions on action evaluations. Cognition & Emotion, 19(8), 1175–1198. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930500203203

- Litman, J. A. (2006). The COPE inventory: Dimensionality and relationships with approach-and avoidance-motives and positive and negative traits. Personality and Individual Differences, 41(2), 273–284. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2005.11.032

- Littleton, H., Horsley, S., John, S., & Nelson, D. V. (2007). Trauma coping strategies and psychological distress: A meta-analysis. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 20(6), 977–988. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20276

- Lockwood, P., Jordan, C. H., & Kunda, Z. (2002). Motivation by positive or negative role models: Regulatory focus determines who will best inspire us. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(4), 854

- Lu, L., & Yuan, Y. C. (2011). Shall I Google it or ask the competent villain down the hall? The moderating role of information need in information source selection. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 62(1), 133–145. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.21449

- Mann, T., Sherman, D., & Updegraff, J. (2004). Dispositional motivations and message framing: A test of the congruency hypothesis in college students. Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 23(3), 330–334. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.23.3.330

- Mesters, I., van den Borne, B., De Boer, M., & Pruyn, J. (2001). Measuring information needs among cancer patients. Patient Education and Counseling, 43(3), 255–264. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0738-3991(00)00166-X doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0738-3991(00)00166-X

- Moerman, N., van Dam, F. S., Muller, M. J., & Oosting, H. (1996). The Amsterdam preoperative anxiety and information scale (APAIS). Anesthesia & Analgesia, 82(3), 445–451. doi:https://doi.org/10.1213/00000539-199603000-00002

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2002). How to use a Monte Carlo study to decide on sample size and determine power. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(4), 599–620. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0904_8

- Muusses, L. D., van Weert, J. C. M., van Dulmen, S., & Jansen, J. (2012). Chemotherapy and information-seeking behaviour: Characteristics of patients using mass-media information sources. Psycho-Oncology, 21(9), 993–1002. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1997

- Myrick, J. G., Willoughby, J. F., & Verghese, R. S. (2016). How and why young adults do and do not search for health information: Cognitive and affective factors. Health Education Journal, 75(2), 208–219. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0017896915571764

- Oyserman, D., Uskul, A. K., Yoder, N., Nesse, R. M., & Williams, D. R. (2007). Unfair treatment and self-regulatory focus. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43(3), 505–512. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2006.05.014

- Payne, S. C., Youngcourt, S. S., & Beaubien, J. M. (2007). A meta-analytic examination of the goal orientation nomological net. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(1), 128. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.1.128

- Prochaska, J. O., & DiClemente, C. C. (1983). Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 51(3), 390–395. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-006X.51.3.390

- Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. doi:https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

- Rothermund, K., Voss, A., & Wentura, D. (2008). Counter-regulation in affective attentional biases: A basic mechanism that warrants flexibility in emotion and motivation. Emotion, 8(1), 34–46. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.8.1.34

- Rutten, L. J. F., Arora, N. K., Bakos, A. D., Aziz, N., & Rowland, J. (2005). Information needs and sources of information among cancer patients: A systematic review of research (1980-2003). Patient Education and Counseling, 57(3), 250–261. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2004.06.006

- Savolainen, R. (2017). Information need as trigger and driver of information seeking: A conceptual analysis. Aslib Journal of Information Management, 69(1), 2–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/AJIM-08-2016-0139

- Schermelleh-Engel, K., Moosbrugger, H., & Müller, H. (2003). Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods of Psychological Research Online, 8(2), 23–74.

- Scholz, U., Doña, B. G., Sud, S., & Schwarzer, R. (2002). Is general self-efficacy a universal construct? Psychometric findings from 25 countries. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 18(3), 242–251. doi:https://doi.org/10.1027//1015-5759.18.3.242

- Shiloh, S., & Orgler-Shoob, M. (2006). Monitoring: A dual-function coping style. Journal of Personality, 74(2), 457–478. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00381.x

- Shipman, J. P., Kurtz-Rossi, S., & Funk, C. J. (2009). The health information literacy research project. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 97(4), 293–301. doi:https://doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.97.4.014

- Strauman, T. J., & Wilson, W. A. (2010). Individual differences in approach and avoidance. In K. D. Vohs & R. F. Baumeister (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation (2nd ed., pp. 447–472). New York: Guilford Press.

- Strauman, T. J. (1996). Stability within the self: A longitudinal study of the structural implications of self-discrepancy theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(6), 1142–1153. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.71.6.1142

- Summerville, A., & Roese, N. J. (2008). Self-report measures of individual differences in regulatory focus: A cautionary note. Journal of Research in Personality, 42(1), 247–254. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2007.05.005

- Symonds, M. R. E., & Moussalli, A. (2011). A brief guide to model selection, multimodel inference and model averaging in behavioural ecology using Akaike’s information criterion. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 65(1), 13–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-010-1037-6

- Terpstra, T., Zaalberg, R., Boer, J. D., & Botzen, W. J. W. (2014). You have been framed! How antecedents of information need mediate the effects of risk communication messages. Risk Analysis, 34(8), 1506–1520. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/risa.12181/full doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.12181

- Van der Molen, (1999). Relating information needs to the cancer experience: 1. Information as a key coping strategy. European Journal of Cancer Care, 8(4), 238–244. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2354.1999.00176.x

- Wagenmakers, E.-J. (2007). A practical solution to the pervasive problems of p values. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 14(5), 779–804. doi:https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03194105

- Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063

- Wilson, T. D. (1981). On user studies and information needs. Journal of Documentation, 37(1), 3–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/eb026702

- Yang, Z. J., & Kahlor, L. (2013). What, me worry? The role of affect in information seeking and avoidance. Science Communication, 35(2), 189–212. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547012441873

- Yi, S., & Baumgartner, H. (2009). Regulatory focus and message framing: A test of three accounts. Motivation and Emotion, 33(4), 435–443. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-009-9148-y

- Young, A., Tordoff, J., & Smith, A. (2017). What do patients want? Tailoring medicines information to meet patients' needs. Research in Social & Administrative Pharmacy: RSAP, 13(6), 1186–1190. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2016.10.006

- Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Self-efficacy: An essential motive to learn. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 82–91. doi:https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1016