Abstract

Objective: To provide insight into the motivational working mechanisms (i.e. mediators) of an effective physical activity (PA) intervention for adults aged over fifty.

Design: The mediation model (N = 822) was investigated in an RCT for the total intervention population, participants who were not norm-active at baseline (targeting PA initiation) and norm-active participants (targeting PA maintenance) separately.

Main Outcome Measures: Potential mediators (attitude, self-efficacy, intention, action planning and coping planning) of the effect on PA (6-months) were assessed at baseline, 3 and/or 6 months.

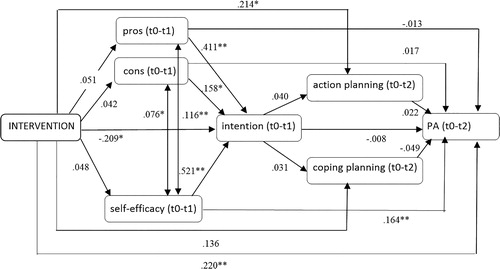

Results: The intervention resulted in a decrease in intention (B= −.209; p=.017), and an increase in action planning (B=.214; p=.018) and PA (B=.220; p=.002). Intention and action planning did not mediate the effect on PA. Self-efficacy, although not significantly influenced by the intervention, was found to be the only motivational variable that predicted change in PA (B=.164; p=.007). These results were confirmed among participants initiating PA. Among norm-active participants no significant intervention effects were identified.

Conclusion: The motivational factors cannot explain the intervention effect on PA. Most likely, the effect can be explained by an interaction between the motivational factors together. Differences between participants initiating versus maintaining PA, highlight the importance of performing mediation analyses per subgroup.

Background

Regular physical activity (PA) reduces the risks of multiple health problems, which often become more prevalent when people age (Hallal et al., Citation2012). The international guideline for PA recommends that people (among all ages) should be physically active at moderate to vigorous intensity for at least 5 days a week, for a minimum of 30 minutes a day (Nelson et al., Citation2007). Although this guideline counts for all adults, the definition for moderate to vigorous intensity differs for adults in general when compared to adults aged 65+ years, and adults aged 50–64 with clinically significant chronic conditions or functional limitations that affect movement ability, fitness, or physical activity. In addition, specifically for this latter mentioned group, it is recommended to perform muscle-strengthening activities using a resistance (weight) that allows 10–15 repetitions for each exercise, and to perform activities that maintain or increase flexibility on at least two days each week for at least 10 min each day (Nelson et al., Citation2007). Among all ages but especially among elderly, even small changes in PA can lead to marked and clinically relevant changes in health status, particularly in inactive or clinical populations (Nelson et al., Citation2007; Rhodes, Janssen, Bredin, Warburton, & Bauman, Citation2017). Regular PA is particularly important to enable older adults to maintain their physical independence, mental and emotional wellbeing, cognitive functioning, and social functioning and thereby to improve their quality of life (Vagetti et al., Citation2014). Because of the aging population, stimulating and maintaining PA among the over-fifties are of major relevance (World Health Organisation, Citation2013).

A systematic review has shown that PA of older adults can be effectively changed through behavioural interventions (Hobbs et al., Citation2013). Most health behaviour interventions are based on the assumption that intervention effects can be achieved by changing relevant underlying motivational determinants (i.e. mediators of the intervention effect) (Glanz & Bischop, 2010; Michie & Johnston, Citation2012; Prestwich, Webb, & Conner, Citation2015). However, as most intervention studies do not report the mechanisms of efficacy, more knowledge of effective motivational working mechanisms of PA interventions is needed (Aromatario et al., Citation2019). By conducting mediation analyses one can gain insight into which motivational determinants of PA are effectively influenced by the intervention, and whether any changes in these putative mediators are responsible for the intervention effect on PA. Insights into what works and what does not work may inform future intervention development and can improve their (cost-) effectiveness.

Several systematic reviews suggest that theory-based interventions are more effective in promoting PA than those without a theory-base (Muellmann et al., Citation2018; Webb, Joseph, Yardley, & Michie, Citation2010). However, the evidence regarding the effectiveness of theory-based interventions compared to interventions not explicitly guided by theory is inconclusive (Prestwich et al., Citation2015). In addition, a recent meta-analyses showed that although the overall effects on PA do not differ significantly between theory-based and no-stated theory interventions, theory-based interventions incorporated a greater number of behaviour change techniques (BCTs) and that interventions that incorporated at least three BCTs of different clusters (as defined by Michie et al. (Citation2013)) were more likely to be effective than those that used one or two (McEwan et al., Citation2018).

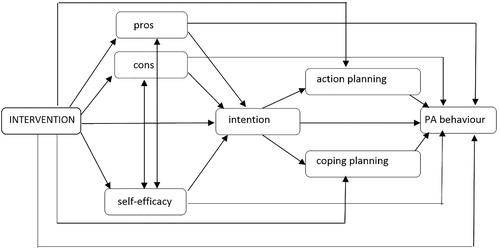

During the Active Plus project, a computer-tailored PA intervention was developed based on a review of theoretical models such as the I-change model (De Vries, Eggers, & Bolman, Citation2013), the Health Action Approach (Schwarzer, Citation2009), the self-regulation theory (Baumeister & Vohs, Citation2004) and the self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, Citation2007). In addition to this literature review regarding the most relevant and modifiable determinants of the initiation and maintenance of PA (Van Stralen, De Vries, Bolman, Mudde, & Lechner, Citation2009), a Delphi study was performed among experts in the field of health promotion and/or in the field of PA determinants (Van Stralen, Lechner, Mudde, De Vries, & Bolman, Citation2010). This Delphi study aimed to reach consensus regarding the relevance of these determinants, and accordingly, the selection of BCTs that proved to be valuable in changing the selected determinants (Van Stralen et al., Citation2008). Most important and modifiable determinants selected for this intervention study were attitude, self-efficacy, intention, action planning and coping planning. Attitude, as a construct of the theory of planned behaviour (TPB), is the belief that behavioural performance is associated with certain positive or negative outcome expectation (i.e. a favourable/unfavourable belief) (Ajzen, Citation1985). Self-efficacy, as a construct of the social cognitive theory (SCT), is the situation dependent appraising of one’s own ability to perform the behaviour successfully (Bandura, Citation1986). Attitude and self-efficacy might influence the behaviour directly, or via intention (see ) (Ajzen, Citation1985; Bandura, Citation1986). Furthermore, attitude and self-efficacy are also assumed to influence each other. A meta-analysis showed that interventions that modify attitudes and self-efficacy (often referred to as motivational determinants) are effective in promoting health behaviour intention and health behaviour change (Sheeran et al., Citation2016).

In order to translate ones intention into actions (i.e. to bridge the intention-behaviour gap), intentions need to be furnished with action plans and coping plans (Sniehotta, Citation2009). The Integrated Model for Change (I-Change Model) (De Vries et al., Citation2013) and the Health Action Process Approach (HAPA; (Schwarzer, Citation2008)) take into account these action and coping plans (often referred to as post-motivational determinants, i.e. the volitional or self-regulative process). The I-Change Model and HAPA both state that intentions are more likely to be translated into action when people make action plans and coping plans for the behaviour they are willing to perform. Action plans indicate that one specifies when, where and how to perform an action (Gollwitzer, Citation1996). Coping plans indicate that people imagine scenarios that hinder them in performing their intended behaviour and develop plans to cope with such challenging situations (Schwarzer, Citation1999). According to the I-Change Model and HAPA, action and coping planning are influenced by ones intention and influence behaviour, and might thus mediate the influence of intention on PA (Schwarzer & Luszczynska, Citation2015) as visualised in . Several meta-analyses have summarised the positive effects of planning on PA (Amireault, Godin, & Vezina-Im, Citation2013; Carraro & Gaudreau, Citation2013; Cradock et al., Citation2017; Gollwitzer & Sheeran, Citation2006; Kwasnicka, Presseau, White, & Sniehotta, Citation2013). Especially in older populations, planning seems effective in bridging the intention-behaviour gap (Reuter et al., Citation2010). However, most of the theories mentioned above mainly focus on PA initiation. There is limited evidence which theories best support PA maintenance and whether they differ from those supporting PA initiation. Reviews have highlighted a lack of reporting of maintenance outcomes (Kwasnicka, Dombrowski, White, & Sniehotta, Citation2016; Murray et al., Citation2017), in which maintenance is defined as sustained behaviour for at least six months. More insight in (post-)motivational factors related to PA maintenance can provide guidance on the development and evaluation of interventions promoting sustained PA.

The computer-tailored Active Plus intervention aims to influence the initiation of PA and the maintenance of PA by targeting its relevant and modifiable determinants (Peels, Van Stralen, et al., Citation2012; Van Stralen et al., Citation2008).

Based on the HAPA and the Precaution Adoption Process (Schwarzer, Citation2009; Van Stralen et al., Citation2008; Weinstein, Citation1988), Active Plus participants were divided into five groups, namely: (1) precontemplators – adults who did not reach the guideline and who did not want to initiate PA; (2) contemplators – adults who did not reach the guideline and who wanted to initiate PA within six months; (3) preparators – adults who did not reach the guideline and who wanted to initiate PA within one month; (4) actors and maintainers (<60 min.) – adults who did reach the guideline but were active for less than 60 minutes per day; and (5) actors and maintainers (>60 min.) – adults who did reach the guideline and were active for more than 60 minutes per day. Participants received tailored advice matching their stage and their personal needs and characteristics. Although all previously mentioned social cognitive determinants of PA are targeted among each participant, in line with the theories stated above the advice sets of the first three groups (targeting to initiate PA) mainly focus on motivational determinants of PA (i.e. attitude, self-efficacy and intention), whereas the advice sets of the last two groups (targeting to maintain PA) mainly focus on post-motivational determinants of PA (i.e. action planning and coping planning). The content of the tailored advice per stage group (i.e. the used theoretical methods and practical strategies) is shown in Online Supplementary Material 1. The effectiveness of the intervention on PA, its use, appreciation and attrition have been described in previous publications (Peels, Bolman, et al., Citation2012, Citation2013; Peels, De Vries et al., Citation2013; Peels et al., Citation2014). Results from a large scale randomised controlled trial showed that the intervention was effective in increasing the weekly minutes of PA (Peels, Bolman, et al., Citation2013; Peels et al., Citation2014). In order to explain the intervention effects on PA, more insight is needed into the mediating working mechanisms of the (post-)motivational variables being targeted by the intervention. It is hypothesised that among those who were not norm-active at baseline an increase in PA after six months will mainly be caused by changes in motivational determinants, whereas among those who were norm-active at baseline the maintenance of PA or the reach of even higher levels in PA will mainly be caused by changes in post-motivational determinants.

The aim of the current study was therefore: (1) to gain insight into which motivational factors explain the intervention effect of Active Plus on PA; (2) to gain insight into the difference in motivational working mechanisms between participants who were not norm-active at the start of Active Plus (aimed to stimulate PA initiation) and participants who were already norm-active (aimed to maintain these levels of PA or reach even higher levels of PA).

Methods

A clustered Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) was conducted; the trial was registered at the Dutch Trial Register (NTR2297) and approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Atrium–Orbis–Zuyd (MEC 10-N-36).

Study design

The Active Plus intervention (delivered in a printed or an online version) and a waiting list control group (who received no advice until the study had finished) were studied in a clustered RCT including assessments at baseline and three, six and twelve months after baseline. For the current study, variables of interest were assessed using self-reported questionnaires before the start of the intervention (baseline), 3 months after baseline and 6 months after baseline (i.e. 2 months after intervention completion). Participants in the Web-based version received invitations for follow-up assessment by e-mail; these included a direct link to the Web-based questionnaire. Participants in the printed version received invitations for follow-up assessment by post, with a printed follow-up questionnaire and a prepaid return envelope.

Intervention

Active Plus is a computer-tailored, theory- and evidence-based PA intervention, and is available in a printed and in a Web-based delivery mode. Intervention participants received 3 times tailored advice within 4 months, based on completed written or Web-based questionnaires (Peels, Van Stralen, et al., Citation2012; Van Stralen et al., Citation2008). Participants received their first tailored advice within 2 weeks after the baseline assessment. The second tailored advice was received 2 months after the baseline assessment, also based on the first assessment. The third tailored advice was received within 4 months after the baseline assessment, based on the second assessment that was filled out by the participants 3 months after baseline. The third advice contained feedback on the changes in PA and determinants within the first three months. Improvements were rewarded, and possible relapses were addressed appropriately with additional suggestions to increase PA levels again. The content of the tailored advice depended on participants’ personal characteristics, current PA level, scores on measures of the (post-)motivational factors, and the extent to which they were planning to change their PA (i.e. all participants received information on all topics, but the specific content and timing of the information differed across participants) (Van Stralen et al., Citation2008). As previously described, the advice sets of the participants who were not sufficiently physically active at baseline (i.e. the initiators) mainly focus on motivational determinants of PA, whereas the advice sets of the participants who were already sufficiently physically active (targeting to maintain PA) mainly focus on post-motivational determinants of PA. Theoretical methods and practical strategies were based on focus group interviews with the target population, a Delphi study and several theoretical models (Van Stralen et al., Citation2008); and were fine-tuned based on analyses of mediators, moderators and the program evaluation of a previous version of the printed intervention (Peels, Van Stralen, et al., Citation2012). An overview of the methods and strategies used in the current intervention can be found in Online Supplementary Material 1 and has been described extensively elsewhere (Peels, De Vries et al., Citation2013; Van Stralen et al., Citation2008).

Participants and procedures

Participants (Dutch speaking adults aged over 50 years) were recruited via direct mailing in the communities of the Municipal Health Council (MHC) regions (N = 6) participating in this project. Originally, the Active Plus intervention was developed in four different intervention conditions (Peels, Van Stralen, et al., Citation2012). As no differences in intervention effect on PA were identified between the intervention conditions (Peels et al., Citation2014), for the current study the intervention was studied as implemented in practice; no differentiation was made between the different intervention conditions. Considering the original study design (i.e. studying the different intervention conditions), the proportion of participants between the control group and the intervention condition is still 1:4, resulting in a G-power calculation (effect size = 0.3, α error probability = .05, power = 80%, allocation ratio N2/N1 = 0.25) showing that a total sample size of 548 participants is required, of which 110 should be allocated to the control group and 438 should be allocated to the intervention group.

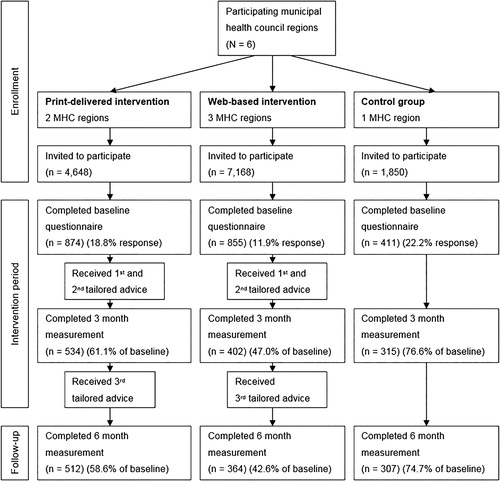

After stratification by age, each MHC provided a random sample of eligible potential participants who received an invitation to participate. provides an overview of the number of invitations that had to be distributed, the number of participants at enrolment and each participation stage. Because a lower response rate was expected for the Web-based intervention (due to the relative innovative character of an online intervention among adults aged over 65) a larger sample of eligible participants was invited for the online intervention. All participants provided informed consent at the time of enrolment.

Measures

Demographics of the participants (age and gender (0 = men; 1 = women), PA and potential (post-)motivational mediators were assessed using self-reported questionnaires.

PA behaviour

Total weekly minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA; in an average week over the last month) were assessed using the validated self-administered Dutch Short Questionnaire to Assess Health Enhancing Physical Activity (SQUASH) (Wendel-Vos, Schuit, Saris, & Kromhout, Citation2003) at baseline and after six months. The frequency of moderate to vigorous activities (days per week), was multiplied by duration (minutes per day) of leisure and transport walking, leisure and transport cycling, sports, gardening, domestic chores and other odd jobs performed with moderate and vigorous intensity. Weekly days with sufficient PA was measured with a single item: ‘On how many days per week are you, in total, moderately physically active by undertaking, for example, heavy walking, cycling, gardening, sports, or other physical activities for at least 30 minutes?’. In relation to actigraph activity monitors, the SQUASH has an overall reliability (rSpearman) of .57) and relative validity (rSpearman) of .67) (Wagenmakers et al., Citation2008). Participants who reached the international PA guideline (i.e. being moderate to vigorously physically active for at least 150 minutes a week, distributed on at least 5 days a week) at baseline were classified as being norm-active at baseline, participants not reaching the minimum of 150 minutes per week or not being active for at least 5 days a week were classified as being not norm-active at baseline.

Motivational mediator measures

At baseline, all (post-)motivational mediators (i.e. attitude, self-efficacy, intention, action planning and coping planning) were assessed. Subsequently, the potential mediators were selected for assessment at different time points, according to time point on which feedback on these variables was delivered within the intervention period. Attitude, self-efficacy and intention are considered to be motivational determinants, and are targeted in the first 2 advice sets (see Online Supplementary Material 1). The effect on these variables could thus be assessed at the 3-month assessment (i.e. 1 month before intervention completion). The main target in the third advice set were post-motivational variables (i.e. action planning and coping planning); these variables were therefore measured at the 6-month assessment (i.e. 2 months after intervention completion). It was explained in the questionnaire that ‘being sufficiently physically active’ refers to being active according to the Dutch guideline for PA which states that one should by moderate to vigorous physically active for at least 5 days a week, 30 minutes a day.

Attitude

The attitude scale (based on a study of Lechner and De Vries (Citation1995)) included 13 statements, of which 7 statements aimed to assess the participant’s opinion on the pros of PA and 6 statements assessed the participant’s opinion on the cons of PA including affective and instrumental beliefs. An example statement was ‘I find being sufficiently physically active very time consuming’. All statements were assessed on a 5-point scale from (−2) ‘Totally disagree’ to (+2) ‘Totally agree’. Previous study results assessing the reliability of this attitude scale in a population aged over 50 showed that the pros-scale had a Cronbach’s α of .86 and that the cons-scale had a Cronbach’s α of .77 (Van Stralen, De Vries, Mudde, Bolman, & Lechner, Citation2011). These estimates are in line with the reliability of both scales as tested in the current study according to the method of Cronbach, Citation1951, which showed a that the pros-scale had a Cronbach’s α of .88 and that the cons-scale had a Cronbach’s α of .78 (see ).

Table 1. Baseline descriptives of potential mediators.

Self-efficacy

The self-efficacy scale (based on a study of Resnick and Jenkins (Citation2000)) included 11 items. An example item was ‘Do you find yourself able to be sufficiently physically active when you are tired?’. All items were assessed on a 5-point scale from (−2) ‘Definitely unable’ to (+2) ‘Definitely able’. Previous study results assessing the reliability of the self-efficacy scale in a population aged over 50 resulted in a Cronbach’s α of .93 (Van Stralen et al., Citation2011). This estimate is in line with the reliability as tested in the current study according to Cronbach, Citation1951, which also showed a Cronbach’s α .93.

Intention

The scale to assess intention included three items and was based on the study of Sheeran and Orbell (Citation1999). An example item is ‘Do you intend to be sufficiently physically active?’. All items were assessed on a 10-point scale from (1) ‘Definitely not’ to (10) ‘Yes, definitely’. The intention scale showed a Cronbach’s α of 0.76 in previous research (Van Stralen et al., Citation2011), whereas in the current study a Cronbach’s α of .94 was found for the intention scale.

Action planning

The scale to assess action planning included 6 statements and was based on a study of Lippke, Ziegelmann, and Schwarzer (Citation2004). An example item is ‘I plan when to do my physical activity’. All statements were assessed on a 5-point scale from (−2) ‘Never’ to (+2) ‘Always’. The action planning scale had a Cronbach’s α of 0.85 in previous research (Scholz, Schuz, Ziegelmann, Lippke, & Schwarzer, Citation2008), whereas in the current study a Cronbach’s α of .93 was found for the action planning scale.

Coping planning

The scale to assess coping planning included 5 statements and was based on a study of Sniehotta, Schwarzer, Scholz, and Schüz (Citation2005). An example item is ‘I plan what to do in situations where something hinders my plans to be sufficiently physically active’. All statements were assessed on a 5-point scale from (−2) ‘Never’ to (+2) ‘Always’. Previous study results assessing the reliability of the coping planning scale showed a Cronbach’s α of 0.87 (Scholz et al., Citation2008), whereas in the current study a Cronbach’s α of .93 was found for the coping planning scale.

Statistical analyses

Baseline and drop-out characteristics

The reliability of the scales used in the current study were assessed by calculating its Cronbach’s alpha (Cronbach, Citation1951). One-way analyses of variance and Chi-squared tests were conducted to test for baseline differences in participant characteristics between the intervention and the control group, and between participants who were included in the Web-based version of the intervention and participants who were included in the printed-version of the intervention. For a more straight forward interpretation of the descriptive variables, the original scale scores from −2 to +2 were transformed in scores from 1 to 5 before conducting these baseline analyses.

Logistic regression analyses were performed to investigate whether dropout was associated with participants’ baseline characteristics (i.e. gender, age, BMI, educational level, intention, perceived pros, perceived cons, self-efficacy, the degree of action planning, the degree of coping planning and baseline PA).

Since the current study relied on a clustered randomisation, it can be expected that participants are not totally independent (Schulz, Altman, & Moher, Citation2010). However, when calculating the intra cluster correlation (ICC) of the participants within the neighbourhoods, an ICC of 0.0 was observed, indicating the absence of cluster effects. For the current study, participants are therefore considered as independent.

Since the different potential determinants of PA may be highly intercorrelated, correlations are calculated to provide insight in the intercorrelatedness between the different variables and the potential multicollinearity. When performing the path models as described below, analyses were corrected for these intercorrelations between potential mediators.

Mediation model analyses

The mediation model (see ) was tested using path analysis of observed variables using the LAVAAN (Rosseel, Citation2012) package for R (R Core Team, Citation2016). The relative chi-square (χ2/df), the Tucker Lewis Index (TLI), the standardised Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) and the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) were used as fit indices to indicate how well the model fitted the data. A cut-off value of < 2 for the relative chi-square, > .95 for the TLI and < .06 for the RMSEA and the SRMR indicate a good fit, and an adequate fit is indicated when TLI exceeds .90, and when RMSEA and SRMR are below .08 (Arbuckle, Citation2011; Kline, Citation2011; CitationTabachnick & Fidell, 2001). The independent variable (i.e. intervention condition) was recoded into a dummy variable, where 0 refers to the control group and 1 refers to the intervention group. Since no differences were found in effect between the printed and the online version of the intervention (not on PA behaviour and not regarding the potential mediators), both intervention conditions (online and printed) were combined into one dummy variable (1 = intervention (online/print); 0 = no intervention). All potential (post-)motivational mediators were centred before entering the model.

The mediation model aims to explain the changes in minutes of moderate to vigorous PA (MVPA) between baseline (t0) and 6 months after baseline (t2). As visualized in , it was assumed that attitude (pros and cons), self-efficacy and intention will first be formed, and consequently will be furnished with action plans and coping plans. Therefore, as potential motivational mediators of the changes in PA (t2-t0), changes in attitude, self-efficacy and intention between baseline (t0) and 3 months (t1) and changes in action planning and coping planning between baseline (t0) and 6 months (t2) were included in the model. It was assumed that the intervention directly affected all included social cognitive variables, and that all included social cognitive variables might directly influence the PA behaviour. Furthermore, it is assumed that pros, cons and self-efficacy might also influence the PA behaviour indirectly via intention, and attitude and self-efficacy are expected to influence each other. Lastly, changes in action planning and coping planning between 0 and 6 months after baseline are assumed to mediate the influence of the changes in intention (t1-t0) on PA (t2-t0). To study whether there are any differences in important (post-)motivational mediators between participants who were already norm-active at baseline and participants who were not norm-active at baseline, the analysis was repeated for both groups separately. To study whether differences in the Beta’s between the norm-active and the not norm-active participants regarding the effect of the intervention on all (post-)motivational variables and the effect of these variables on PA are significant, the Wald-statistic will be calculated (as the difference in Beta’s divided by the pooled standard errors) in which a Wald-score between −1.96 and 1.96 is considered to be non-significant. Regarding the outcome measure (i.e. minutes of MVPA per week) the Cohen’s d effect sizes (ESs) were calculated for participants who were already norm-active at baseline and participants who were not norm-active at baseline. ESs were defined as the mean difference in effect between the intervention group and the control group divided by the pooled standard deviations of those means (Rossi, Citation2003).

Results

Baseline characteristics

Of the 2,140 participants at baseline, 1,183 participants (55%) completed the 6-month assessment (see ). However, due to multiple missing data in one of the assessed potential determinants at one of the time points (i.e. missing a score at one of the variables at baseline, 3 months or 6 months assessment) only 827 participants were included in the mediation model. Participant data showed that the (post-)motivational scales used in the current study had Cronbach’s alphas varying between .78 and .94 (see ). Participants had an average age of 62.4 years (SD = 7.71) and 53% were female. There was no significant difference in age or gender between the Web-based and the printed intervention group, nor between the intervention group and the control group. A significant difference in PA was identified between the intervention and the control group, in which participants in the intervention group were more likely to be norm-active at baseline (47%) than participants in the control group (39%; p = .045). The only difference in motivational variables at baseline between the intervention group and the control group was found for self-efficacy, on which participants in the intervention group (mean score = 3.74, SD = .68) had a significant (p = .006) higher baseline score than participants in the control group (mean score = 3.60, SD = .67). No significant differences were identified in baseline scores between the printed and the online intervention group. As presented in , several differences were found in baseline scores on motivational variables between participants who were norm-active at baseline and participants who were not yet norm-active at baseline.

Dropout analysis showed that older participants (B = −.027, p <.001) and participants who perceived more cons of PA at baseline (B = −.191, p = .035) were less likely to drop out before the 6-month follow-up assessment. Predictors of dropout did not differ between the intervention group and the control group.

As shown in , all (post-)motivational factors assessed in the current study, are significantly correlated with most of the other (post-)motivational factors. In the model analyses as described below, these correlations are taken into account.

Table 2. Pearson correlations of all cognitive variables assessed in the mediation model.

Mediation model

When looking at the total Active Plus population, the mediation model fitted the data adequately according to most fit criteria (χ2 = 14.3, df = 6; χ2/df = 2.4; TLI = .820; RMSEA = .041; SRMR= .02). Only the TLI indicated poor fit. As visualized in the model below (), among the general Active Plus population the intervention resulted in a significant (direct) increase in minutes of MVPA after 6 months (B = .220; p = .002). The intervention resulted in a significant decrease in intention after three months (B = −.209; p = .017) and significant increase in action planning after six months (B = .214; p = .018). The intervention did not significantly affect any of the other social cognitive variables (see and ).

Figure 3. Mediation model of the total group. *p <.05; **p <.01.

Note: t0 = assessed at baseline; t1 = assessed 3 months after baseline; t2 = assessed 6 months after baseline.

Table 3. Intervention effects on (post-)motivational variables and minutes of MVPA.

Although not significantly influenced by the intervention, an increase in pros (B = .411; p ≤ .001), cons (B = .154; p = .024) and self-efficacy after 3 months (B = .521; p ≤ .001) resulted in a significant increase in intention after three months. Intention, in turn, was not directly related to the increase in PA at 6 months (B = −.008; p = .778). The significant change in intention and change in the amount of action planning as a result of the Active Plus intervention did not result in an increase in PA nor did action planning mediate the effect of intention on PA. Self-efficacy, although not significantly influenced by the intervention itself, was found to be the only motivational variable that directly predicted change in PA behaviour (B = .164; p = .007). The significant changes in self-efficacy were associated with changes in pros (B = .116; p = .003) and cons (B = .076; p = .020).

When considering those who were not norm-active at baseline (n = 369) and those who were norm-active at baseline (n = 453) separately (see ), results showed that the relations as found in the total group were mainly confirmed in the group who was not norm-active at baseline. No significant relations were found in the group who was norm active at baseline. Whereas a significant intervention effect on PA was found among participants who were not norm-active at baseline (B = .247; p = .003), no significant intervention effect on PA was found among participants who were norm-active at baseline (B = .209; p = .084). Descriptive statistics (see ) showed that among participants who were not norm-active at baseline, the intervention groups increased its PA behaviour significantly more than the control group, resulting in an effect size of 0.36. Participants who were norm-active at baseline also increased their PA behaviour within the intervention group, whereas the control group did not increase their PA behaviour, resulting in an effect size of 0.18. This differences in PA, however, was not significant.

Table 4. Descriptive statistics of minutes of MVPA at baseline (T0) and after six months (T2).

Significant differences between participants who were not norm-active and those who were norm-active at baseline were found regarding the effect of the intervention on intention, in which no intervention effect on intention was identified among participants who were norm-active at baseline (B = .065; p = .608) and a significant negative effect of the intervention on intention was found among participants who were not norm-active at baseline (B = −.368; p = .002). Furthermore, results showed that the effect of pros and cons on PA was significantly more positive among participants who were not norm-active at baseline than among participants who were norm-active at baseline.

Discussion

This study aimed to provide insight into the motivational and post-motivational working mechanisms through which a tailored intervention targeted PA initiation and maintenance among adults aged over fifty. The current study showed that (among the total study population) Active Plus resulted in a significant decrease in intention after three months and a significant increase in the amount of action planning after 6 months. Probably, participants increased their PA behaviour substantially in the first three months of the intervention, resulting in a lack of intention after three months to increase their PA behaviour more than they did in the first three months. On the other hand, the significant decrease in intention might be explained by the response-shift phenomenon (Fokkema, Smits, Kelderman, & Cuijpers, Citation2013; Sprangers & Schwartz, Citation1999), which indicates that the interpretation of self-report items and response categories may vary over time. Whereas participants at baseline scored relatively high on their intention to be sufficiently physically active, the intervention might have made the participants more aware of the meaning (and the difficultness) of ‘being sufficiently physically active’ which might have resulted in a different interpretation of these questions and thus a lower response score at the follow-up measurement.

Although all behavioural change strategies of the current intervention were grounded in theory and evidence-based, the intervention was only able to evidently increase the amount of action planning. One explanation for not detecting an effect on the other (post-)motivational variables is that the intervention itself (advice offered 3 times over 4 months) was not sufficient in dose to change these motivational variables. Another explanation for not detecting an effect on the other (post-) motivational variables is the relatively high baseline score on these variables among our target group. Scores on the motivational factors (i.e. pros, cons and self-efficacy) were relatively high at baseline (averages varying between 3.48 and 4.13 on a scale of 1-5 in the total Active Plus group), whereas average scores on post-motivational factors (i.e. action planning and coping planning) were respectively 2.21 and 2.88. This indicates that these post-motivational factors were more susceptible for change than the (not significantly increased) motivational factors, whereas a ceiling effect might limit any further improvement in the motivational factors. Most participants were thus already relatively motivated to be sufficiently physically active. Stimulating to make concrete action plans might help these motivated participants (targeted to initiate PA behaviour) to translate their intention into actual behaviour change.

Several meta-analyses have summarized the positive effects of planning on PA (Amireault et al., Citation2013; Carraro & Gaudreau, Citation2013; Cradock et al., Citation2017; Gollwitzer & Sheeran, Citation2006; Kwasnicka et al., Citation2013), however, although a significant effect of the intervention on action planning was found, no significant relationship was identified between planning and PA in the current study. Also, although a mediation effect by action planning and coping planning between intention and PA is hypothesized by the HAPA (Schwarzer, Citation2008), this was not confirmed in the current study. The increase in the amount of action planning as a result of Active Plus could thus not explain the intervention effects on PA. Probably, the effect of planning on PA has vanished by the inclusion of other volitional constructs in the mediation model, like self-efficacy which did result in a significant increase in PA. Previous studies have shown that the effect of planning on behaviour was no direct one but there was a serial mediation via action control or self-efficacy (i.e. action control and self-efficacy were found to mediate the association between planning and the outcome behaviour) (Godinho, Alvarez, Lima, & Schwarzer, Citation2014; Kreausukon, Gellert, Lippke, & Schwarzer, Citation2012). Also preparatory behaviours (i.e. any behavioural performance that is performed prior to and in relation to the target behaviour) have been identified to mediate between action planning and PA (Barz et al., Citation2016). Furthermore, as well as in the study of Godinho et al. (Citation2014) as in our own study, there was a medium to strong correlation between action planning and coping planning (varying between .26 and .44 over the different time points of assessment). Although factor analyses showed that both planning concepts could not be merged into a single planning construct, discriminant validity might be lacking by the strong correlation between both concepts, which might explain the vanished effect of both planning concepts on PA. More research is needed to provide insight in the different sequential mediation processes which might explain the intervention effects on PA, and more insight in the construct validity of the different motivational variables is needed.

Results of our analyses on participants who were norm-active at baseline and those who were not norm-active at baseline separately showed that the results of our general mediation model were only confirmed among participants who were not norm-active at baseline. In contrast to our hypotheses, no stronger intervention effect was found on the motivational determinants among the participants who were not norm-active at baseline, nor were stronger intervention effects identified on the post-motivational determinants among the norm-active participants. It might be that adults participating in this intervention who were not yet norm active, did already have a relatively higher intention to become more physically active (when compared to the general population) and thus relative high baseline scores on motivational determinants, making an effect on post-motivational determinants like action planning more likely within this specific group of participants. More appropriate recruitment methods are needed to reach participants with a lower intention to become more physically active (e.g. by using telephone reminders and financial incentives (Treweek et al., Citation2013) or the provision of peer and counsellor support (Murray et al., Citation2009)). When these participants with low basic intention are included, intervention effects on pre-motivational determinants might be more likely.

Furthermore, our results showed that (although not significantly influenced by the intervention) an increase in pros and cons is among participants who were not norm-active at baseline significantly more important for increasing PA behaviour than among participants who were already norm active at baseline. These results highlight the importance of tailoring an intervention to the participants baseline PA behaviour, and targeting these motivational factors especially among participants who are not yet norm-active at baseline.

The lack of an intervention effect on PA and its motivational factors among participants who were already norm-active at baseline, can probably be explained by the participants history in PA behaviour. In the current study, maintenance was defined as sustained behaviour for at least six months, and it was hypothesized that an increase in post-motivational factors (e.g. action planning and coping planning) might stimulate maintenance. In most studies, this maintenance in PA behaviour is studied from 6 months after the behaviour was initiated. However, this population who was norm-active already might have formed their habits in PA behaviour decades ago and might already be very competent in formulating action plans and coping plans. Nevertheless, the aging process tends to reducephysical fitness (strength, endurance, agility, and flexibility), resulting in difficulties in daily life activities and a decline in PA (Milanovic et al., Citation2013). For this specific group, more insight is needed in how decline in PA behaviour as a result of ageing can be prevented. Appropriate strategies to handle these ageing-related perceptions resulting a decline in PA behaviour are needed. In line with the review of Kwasnicka et al. who show that there are distinct patters of theoretical explanations for behaviour change and behaviour maintenance (Kwasnicka et al., Citation2016), our study confirms that future research should focus on the informed development of behaviour change maintenance theory in addition to theories regarding behaviour change.

In conclusion, the changes in PA as a result of the Active Plus intervention (that were mainly found among participants who were not norm-active at baseline) cannot be explained by mediation of any of the separately assessed (post-)motivational variables. As the current study showed strong associations between several (post-)motivational factors (e.g. attitude and self-efficacy, attitude and intention, self-efficacy and intention), the (post-)motivational working mechanisms of PA can be considered as a very complex process. Most likely, the intervention effect on PA can be explained by a combination or an interaction between the (limited affected) (post-)motivational variables together (i.e. a non-significant effect of several single determinants, might together result in a significant effect on PA). Furthermore, other social-cognitive variables not assessed in the current study (i.e. awareness of the sufficiency of PA and changes in environmental perceptions (Van Stralen et al., Citation2011)) might also be partly responsible for the effect of the intervention on PA.

Strengths and limitation

The strengths of the present study include the large sample, and a strong prospective design assessing mediators prior to the outcome measure. However, there are also some limitations to this study. First of all, there was considerable dropout from the intervention. Although no systematic differences were found in dropout between the different intervention conditions, it could be that due to the dropout our analyses cannot be generalised to the total population of adults aged over fifty. Secondly, although we had a large sample for testing complex models, the power for performing subgroup analyses might still be limited. Thirdly, although the behavioural change strategies used in this study were grounded in theory and evidence-based, we can only speculate about which specific aspects of the intervention (as can be referred to by the creation of taxonomies of behaviour change techniques (Michie et al., Citation2013)) acted on potential mediators of the intervention effect. As is the case in most interventions, Active Plus is based on a combination of BCTs and when there is no randomization to a certain BCT, we can only speculate about which specific BCT acted on potential mediators of the intervention effect, and causal inferences about the BCT-mediator-outcome relationship are tenuous (Mackinnon, Fritz, Williams, & Lockwood, Citation2007). Fourthly, data on potential motivational determinants was only gathered 3 and/or 6 months after baseline. It can be recommended to gather data on potential motivational determinants of PA on a longer time horizon to provide more insight in the differences in motivational determinants of PA regarding the maintenance of recently established behaviours versus behaviours that are already a habit and might be of danger for decline as a result of ageing. Interactions between the time the behaviour was established and the importance of these motivational determinants over time should be studied. Fifthly, the usage of gain scores (in contrast to using residual change scores) within the current study may be questionable. One of the most important arguments to decide between both methodologies is the research question the study aims to answer: as in the current study we aim to determine mechanisms underlying the effectiveness of the intervention, and to identify difference between effectiveness on these determinants regarding the participants baseline level of PA, when correcting for differences in PA at baseline (i.e. using residual change scores) this might mask important findings of our study (Fitzmaurice, Laird, & Ware, Citation2004; Van Breukelen, Citation2013; Zumbo, Citation1999). Furthermore, since gain score analysis offers greater power because it estimates fewer parameters (Oakes & Feldman, Citation2001), and the more straight forward interpretation of its results, it was decided to use gain scores instead of residual change scores in the current study.

Finally, the assessment of the (post-)motivational variables and PA relied on data collected using validated, but self-report questionnaires, which might have resulted in answers biased through social desirability. The inclusion of objective measures of PA is recommended.

Implications for practice and future research

The results of the current study suggest some tentative recommendations for future tailored PA interventions for adults aged over fifty. To stimulate action planning in PA, strategies used in the current intervention (invite to formulate action plans in a week schema (Peels, De Vries et al., Citation2013)) can be recommended, especially for non-norm active adults aged over fifty. The substantial changes in PA as a result of the Active Plus intervention cannot be explained by mediation of any of the assessed (post-)motivational variables. Most likely, the intervention effect on PA can be explained by a combination or an interaction between the (limited affected) variables together which indicates that a combination of strategies used in the current intervention can be effective in stimulating PA, especially among participants who are not yet norm-active at baseline. Differences between participants initiating versus maintaining PA, highlight the importance of performing mediation analyses per subgroup. For participants who were norm-active at baseline already, more insight is needed is how decline in PA behaviour as a result of ageing can be prevented. In addition to stimulating maintenance, appropriate strategies to prevent decline in PA behaviour are needed.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (53.5 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ajzen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behaviour. In J. Kuhl & J. Beckman (Eds.), Action control: From cognition to behaviour (pp. 11–39). Heidelberg: Springer.

- Amireault, S., Godin, G., & Vezina-Im, L. A. (2013). Determinants of physical activity maintenance: A systematic review and meta-analyses. Health Psychology Review, 7(1), 55–91. doi:10.1080/17437199.2012.701060

- Arbuckle, J. L. (2011). Amos 20 user’s guide IBM. Mount Pleasant: Amos Development Corporation.

- Aromatario, O., Van Hoye, A., Vuillemin, A., Foucaut, A. M., Crozet, C., Pommier, J., & Cambon, L. (2019). How do mobile health applications support behaviour changes? A scoping review of mobile health applications relating to physical activity and eating behaviours. Public Health, 175, 8–18. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2019.06.011

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs: NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Barz, M., Lange, D., Parschau, L., Lonsdale, C., Knoll, N., & Schwarzer, R. (2016). Self-efficacy, planning, and preparatory behaviours as joint predictors of physical activity: A conditional process analysis. Psychology & Health, 31(1), 65–78. doi:10.1080/08870446.2015.1070157

- Baumeister, R. F., & Vohs, K. D. (2004). Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory, and applications. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

- Carraro, N., & Gaudreau, P. (2013). Spontaneous and experimentally induced action planning and coping planning for physical activity: A meta-analysis. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 14(2), 228–248. doi:10.1016/j.psychsport.2012.10.004

- Cradock, K. A., Olaighin, G., Finucane, F. M., Gainforth, H. L., Quinlan, L. R., & Ginis, K. A. M. (2017). Behaviour change techniques targeting both diet and physical activity in type 2 diabetes: A systematic review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 14(1), 18. p doi:10.1186/s12966-016-0436-0

- Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3), 297–334. doi:10.1007/BF02310555

- De Vries, H., Eggers, S., & Bolman, C. (2013). The role of action planning and plan enactment for smoking cessation. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 393. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-393

- Fitzmaurice, G. M., Laird, N. M., & Ware, J. H. (2004). Applied longitudinal analysis. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Fokkema, M., Smits, N., Kelderman, H., & Cuijpers, P. (2013). Response shifts in mental health interventions: An illustration of longitudinal measurement invariance. Psychological Assessment, 25(2), 520–531. doi:10.1037/a0031669

- Glanz, K., & Bishop, D. B. (2010). The role of behavioral science theory in development and implementation of public health intervention. Annual Review of Public Health, 31(1), 399–418. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103604

- Godinho, C. A., Alvarez, M., Lima, M. L., & Schwarzer, R. (2014). Will is not enough: Coping planning and action control as mediators in the prediction of fruit and vegetable intake. British Journal of Health Psychology, 19(4), 856–870. doi:10.1111/bjhp.12084

- Gollwitzer, P. M. (1996). The volitional benefits of planning. In P. M. Gollwitzer & J. A. Barg (Eds.), The psychology of action: Linking cognition and motivation to behavior (pp. 287–312). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

- Gollwitzer, P. M., & Sheeran, P. (2006). Implementation intentions and goal achievement: A meta-analysis of effects and processes. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 38, 69–119.

- Hallal, P. C., Andersen, L. B., Bull, F. C., Guthold, R., Haskell, W., & Ekelund, U. (2012). Global physical activity levels: Surveillance progress, pitfalls, and prospects. The Lancet, 380(9838), 247–257. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60646-1

- Hobbs, N., Godfrey, A., Lara, J., Errington, L., Meyer, T. D., Rochester, L., … Sniehotta, F. F. (2013). Are behavioural interventions effective in increasing physical activity at 12 to 36 months in adults aged 55 to 70 years? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Medicine, 11(1), 75. p doi:10.1186/1741-7015-11-75

- Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Kreausukon, P., Gellert, P., Lippke, S., & Schwarzer, R. (2012). Planning and self-efficacy can increase fruit and vegetable consumption: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 35(4), 443–451. doi:10.1007/s10865-011-9373-1

- Kwasnicka, D., Dombrowski, S. U., White, M., & Sniehotta, F. F. (2016). Theoretical explanations for maintenance of behaviour change: A systematic review of behaviour theories. Health Psychology Review, 10(3), 277–296. doi:10.1080/17437199.2016.1151372

- Kwasnicka, D., Presseau, J., White, M., & Sniehotta, F. F. (2013). Does planning how to cope with anticipated barriers facilitate health-related behaviour change? A systematic review. Health Psychology Review, 7(2), 129–145. doi:10.1080/17437199.2013.766832

- Lechner, L., & De Vries, H. (1995). Participation in an employee fitness program: Determinants of high adherence low adherence, and dropout. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 37(4), 429–436. doi:10.1097/00043764-199504000-00014

- Lippke, S., Ziegelmann, J., & Schwarzer, R. (2004). Behavioral intentions and action plans to promote physical exercise: A longitudinal study with orthopedic rehabilitation patients. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 26(3), 470–483. doi:10.1123/jsep.26.3.470

- Mackinnon, D. P., Fritz, M., Williams, J., & Lockwood, C. (2007). Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect: Program PRODLIN. Behavior Research Methods, 39(3), 384–389. doi:10.3758/BF03193007

- McEwan, D., Beauchamp, M. R., Kouvousis, C., Ray, C. M., Wyrough, A., & Rhodes, R. E. (2018). Examining the active ingredients of physical activity interventions underpinned by theory versus nu stated theory: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology Review, 13(1), 1–17. doi:10.1080/17437199.2018.1547120

- Michie, S., & Johnston, M. (2012). Theories and techniques of behaviour change: Developing a cumulative science of behaviour change. Health Psychology Review, 6(1), 1–6. doi:10.1080/17437199.2012.654964

- Michie, S., Richardson, M., Johnston, M., Abraham, C., Francis, J., Hardeman, W., … Wood, C. E. (2013). The behaviour change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: Building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 46(1), 81–95. doi:10.1007/s12160-013-9486-6

- Milanovic, Z., Pantelic, S., Traikovic, N., Sporis, G., Kostic, R., & James, N. (2013). Age-related decrease in physical activity and functional fitness among elderly men and women. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 8, 549–556.

- Muellmann, S., Forberger, S., Mollers, T., Broring, E., Zeeb, H., & Pischke, C. (2018). Effectiveness of eHealth interventions for the promotion of physical activity in older adults: A systematic review. Preventive Medicine, 108, 93–110. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.12.026

- Murray, J. M., Brennan, S. F., French, D. P., Patterson, C. C., Kee, F., & Hunter, R. F. (2017). Effectiveness of physical activity interventions in achieving behaviour change maintenance in young and middle aged adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Social Science & Medicine, 192, 125–133. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.09.021

- Murray, E., Khadjesari, Z., White, I. R., Kalaitzaki, E., Godfrey, C., McCambridge, J., … Wallace, P. (2009). Methodological challenges in online trials. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 11(1), e9. doi:10.2196/jmir.1052

- Nelson, M. E., Rejeski, W. J., Blair, S. N., Duncan, P. W., Judge, J. O., King, A. C., … Castaneda-Sceppa, C. (2007). Physical activity and public health in older adults: Recommendation from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 39(8), 1435–1445. doi:10.1249/mss.0b013e3180616aa2

- Oakes, J. M., & Feldman, H. A. (2001). Statistical power for nonequivalent pretest-posttest designs: The impact of change-score versus ANCOVA models. Evaluation Review, 25(1), 3–28. doi:10.1177/0193841X0102500101

- Peels, D. A., Bolman, C., Golsteijn, R. H. J., De Vries, H., Mudde, A. N., Van Stralen, M. M., & Lechner, L. (2012). Differences in reach and attrition between web-based or print-delivered tailored interventions among adults aged over fifty. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 14(6), e179. doi:10.2196/jmir.2229

- Peels, D. A., Bolman, C., Golsteijn, R. H. J., De Vries, H., Mudde, A. N., Van Stralen, M. M., & Lechner, L. (2013). Long-term efficacy of a tailored physical activity intervention among older adults. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 10(1), 104. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-10-104

- Peels, D. A., De Vries, H., Bolman, C., Golsteijn, R. H. J., Van Stralen, M. M., Mudde, A. N., & Lechner, L. (2013). Differences in the use and appreciation of a Web-based or printed computer tailored physical activity intervention for people aged over fifty. Health Education Research, 28(4), 715–731. doi:10.1093/her/cyt065

- Peels, D. A., Van Stralen, M. M., Bolman, C., Golsteijn, R. H. J., De Vries, H., Mudde, A. N., & Lechner, L. (2012). The development of a web-based computer tailored advice to promote physical activity among people older than 50 years. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 14(2), e39. doi:10.2196/jmir.1742

- Peels, D. A., Van Stralen, M. M., Bolman, C., Golsteijn, R. H. J., De Vries, H., Mudde, A. N., & Lechner, L. (2014). The differentiated effectiveness of a printed versus a web-based tailored intervention to promote physical activity among the over-fifties. Health Education Research, 29(5), 870–882. doi:10.1093/her/cyu039

- Prestwich, A., Webb, T. L., & Conner, M. (2015). Using theory to develop and test interventions to promote changes in health behaviour. Current Opinion in Psychology, 5, 1–5. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.02.011

- R Core Team. (2016). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

- Resnick, B., & Jenkins, L. S. (2000). Testing the reliability and validity of the self-efficacy for exercise scale. Nursing Research, 49(3), 154–159. doi:10.1097/00006199-200005000-00007

- Reuter, T., Ziegelmann, J. P., Wiedemann, A. U., Lippke, S., Schuz, B., & Aiken, L. S. (2010). Planning bridges the intention-behaviour gap: Age makes a difference and strategy use explains why. Psychology & Health, 25(7), 873–887. doi:10.1080/08870440902939857

- Rhodes, R. E., Janssen, I., Bredin, S. S. D., Warburton, D. E. R., & Bauman, A. (2017). Physical activity: Health impact, prevalence, correlates and interventions. Psychology & Health, 32(8), 942–975. doi:10.1080/08870446.2017.1325486

- Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. doi:10.18637/jss.v048.i02

- Rossi, J. S. (2003). Comparison of the use of significance testing and effect sizes in theory-based health promotion research. In 43rd Annual Meeting of the Society for Multivariate Experimental Psychology, Keystone.

- Ryan, R., & Deci, E. (2007). Active human nature: Self-determination theory and the promotion and maintenance of sport, exercise and health. In M. S. Hagger & N. L. D. Chatzisarantis (Eds.), Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in exercise and sport (pp. 1–19). Champaign: Human Kinatics Europe Ltd.

- Scholz, U., Schuz, B., Ziegelmann, J., Lippke, S., & Schwarzer, R. (2008). Beyond behavioural intentions: Planning mediates between intentions and physical activity. British Journal of Health Psychology, 13(3), 479–494. doi:10.1348/135910707X216062

- Schulz, K., Altman, D., & Moher, D. (2010). CONSORT 2010 Statement: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. British Medical Journal, 322, 340.

- Schwarzer, R. (1999). Self-regulatory processes in the adoption and maintenance of health behaviors. Journal of Health Psychology, 4(2), 115–127. doi:10.1177/135910539900400208

- Schwarzer, R. (2008). Modeling health behavior change: How to predict and modify the adoption and maintenance of health behaviors. Applied Psychology, 57(1), 1–29. Retrieved from doi:10.1111/j.1464-0597.2007.00325.x

- Schwarzer, R. (2009). The health action approach (HAPA). doi:10.15517/ap.v30i121.23458

- Schwarzer, R., & Luszczynska, A. (2015). Health action process approach. In M. Conner & P. Norman (Eds.), Predicting and changing health behaviour: Research and practice with social cognition models (pp. 252–278). Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Sheeran, P., Maki, A., Montanaro, E., Avis-Yitshak, A., Bryan, A., Klein, W. M., … Rothman, A. J. (2016). The impact of changing attitudes, norms, and self-efficacy on health-related intentions and behavior: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology, 35(11), 1178.

- Sheeran, P., & Orbell, S. (1999). Implementation intentions and repeated behaviour: Augmenting the predictive validity of the theory of planned behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology, 37, 231–250. p

- Sniehotta, F. F. (2009). Towards a theory of intentional behavior change: Plans, planning, and self-regulation. British Journal of Health Psychology, 14(2), 261–273. doi:10.1348/135910708X389042

- Sniehotta, F. F., Schwarzer, R., Scholz, U., & Schüz, B. (2005). Action planning and coping planning for long-term lifestyle change: Theory and assessment. European Journal of Social Psychology, 35(4), 565–576. doi:10.1002/ejsp.258

- Sprangers, M., & Schwartz, C. (1999). Integrating response shift into health-related quality of life research: A theoretical model. Social Science & Medicine, 48(11), 1507–1515. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00045-3

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2001). Using multivariate statistics (Vol. 4). Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

- Treweek, S., Lockhart, P., Pitkethly, M., Cook, J. A., Kjeldstrøm, M., Johansen, M., … Mitchell, E. D. (2013). Methods to improve recruitment to randomised controlled trials: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ Open, 3(2), e002360. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002360

- Vagetti, G. C., Filho, V. C. B., Moreira, N. B., De Oliveira, V., Mazzardo, O., & de Campos, W. (2014). Association between physical activity and quality of life in the elderly: A systematic review, 2000-2012. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 36(1), 76–88. doi:10.1590/1516-4446-2012-0895

- Van Breukelen, G. J. P. (2013). ANCOVA versus CHANGE from baseline in nonrandomized studies: The difference. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 48(6), 895–922. doi:10.1080/00273171.2013.831743

- Van Stralen, M. M., De Vries, H., Bolman, C., Mudde, A. N., & Lechner, L. (2009). Determinants of initiation and maintenance of physical activity in older adults: A literature review. Health Psychology Review, 3(2), 147–207. doi:10.1080/17437190903229462

- Van Stralen, M. M., De Vries, H., Mudde, A. N., Bolman, C., & Lechner, L. (2011). The long-term efficacy of two computer-tailored physical activity interventions for older adults: Main effects and mediators. Health Psychology, 30(4), 442–452. doi:10.1037/a0023579

- Van Stralen, M. M., Kok, G., De Vries, H., Mudde, A. N., Bolman, C., & Lechner, L. (2008). The Active Plus protocol: Systematic development of two theory and evidence-based tailored physical activity interventions for the over-fifties. BMC Public Health, 8(1), 399. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-8-399

- Van Stralen, M. M., Lechner, L., Mudde, A. N., De Vries, H., & Bolman, C. (2010). Determinants of awareness, initiation and maintenance of physical activity among the over-fifties: A Delphi study. Health Education Research, 25(2), 233–247. doi:10.1093/her/cyn045

- Wagenmakers, R., Van den Akker-Scheek, I., Groothoff, J. W., Zijlstra, W., Bulstra, S. K., Kootstra, J. W. J., … Stevens, M. (2008). Reliability and validity of the short questionnaire to assess health-enhancing physical actiivty (SQUASH) in patients after total hip arthroplasty. BMC Muskuloskeletal Disorders, 9, 141.

- Webb, T. L., Joseph, J., Yardley, L., & Michie, S. (2010). Using the internet to promote health behavior change: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of theoretical basis, use of behavior change techniques and mode of delivery on efficacy. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 12(1), e4. doi:10.2196/jmir.1376

- Weinstein, N. D. (1988). The precaution adoption process. Health Psychology, 7(4), 355–386. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.7.4.355

- Wendel-Vos, G. C. W., Schuit, A. J., Saris, W. H., & Kromhout, D. (2003). Reproducibility and relative validity of the short questionnaire to assess health-enhancing physical activity. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 56(12), 1163–1169. doi:10.1016/S0895-4356(03)00220-8

- World Health Organisation. (2013). Global action plan for the prevention and control of NCD’s (2013–2020). Geneva: WHO Press.

- Zumbo, B. D. (1999). The simple difference score as an inherently poor measure of change: Some reality, much mythology. In B. Thompson (Ed.), Advances in social science methodology, Volume 5, (pp. 269–304). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.