Abstract

Medically unexplained physical symptoms (MUPS) are a frequent phenomenon. Understanding adults and adolescents’ lived experience with MUPS is essential for providing adequate care, yet a rigorous synthesis of existing studies is missing. Objective: This study aimed to summarize findings from primary qualitative studies focused on adults’ and adolescents’ experience of living with MUPS. Design: Qualitative studies were searched in the PsycINFO, PsycARTICLES, and Medline databases and manually. A total of 23 resources met the inclusion criteria and were subjected to a qualitative meta-summary. Results: Eight themes were found across the set of primary studies, namely, the need to feel understood, struggling with isolation, ‘sense of self’ in strain, facing uncertainty, searching for explanations, ambivalence about diagnosis, disappointed by healthcare, and active coping. Conclusion: The eight themes represent the core struggles adults’ and adolescents’ with MUPS face in their lives, psychologically and socially. Although these themes appear to be universal, the analysis also revealed considerable variability of experience in terms of expectations from healthcare professionals, attitude towards formal diagnoses, ability to cope with the illness, or potential to transform the illness experience into personal growth. Addressing this diversity of needs represents a significant challenge for the healthcare system.

Medically unexplained physical symptoms (MUPS) represent a highly frequent group of complaints in healthcare. The 12-month prevalence of MUPS in primary care was estimated to be as high as 49% (Haller et al., Citation2015), although the accuracy of this estimate remains doubtful. Not only are MUPS connected with specific challenges for practitioners, but they are also associated with specific experiences for patients, which may influence the course of the treatment. Therefore, understanding the lived experience of adults and adolescents with MUPS is an essential aspect of adequate medical care.

The term MUPS has been extensively debated. While some authors distinguish particular syndromes, such as chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), fibromyalgia (FM), psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES), and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) (Wessely & White, Citation2004), others argue that there is significant overlap among these syndromes in terms of symptoms and that these patients tend to share many characteristics, including response to treatment (e.g., Nimnuan et al., Citation2001). The role of psychological factors is also emphasized to a varying degree: Whether a symptom is medically explained is crucial in the area of somatic medicine; however, in psychiatry, the distinction becomes blurred, and patients’ attitude and reactions towards their symptoms become central (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). We adopted the term MUPS as an umbrella term for all these conditions in our study because of its wide use and etiological neutrality.

Patients with MUPS share some common characteristics in comparison with other patient groups. They tend to have the following characteristics: report more psychological distress, functional impairment, and social isolation (Dirkzwager & Verhaak, Citation2007); seek more emotional support from their general practitioner (Salmon et al., Citation2005); have an unfulfilled need for an explanation for their condition (Ring et al., Citation2004); often have psychiatric comorbidities; and highly utilize healthcare (Smith & Dwamena, Citation2007; Wessely & White, Citation2004). Furthermore, patients suffering from persistent MUPS tend to be exposed to extensive surgery and have a higher risk of iatrogenic harm (Fink, Citation1992).

Many current studies focus on the experiences of general practitioners (GPs) in treating patients with MUPS. Addressing an unknown etiology of symptoms seems to be quite difficult for GPs and may lead to the lack of confidence and frustration in these professionals (e.g., Harsh et al., Citation2016). Furthermore, they tend to experience negative feelings towards their patients, such as irritation or resistance (den Boeft et al., 2017), and may perceive them as ‘attention seekers’ (Czachowski et al., Citation2012), which may result in an uncomfortable encounter for both (Johansen & Risor, Citation2017).

To provide appropriate treatment, GPs need to understand the patients’ lived experience. Although many qualitative studies have been conducted in this area, synthesizing studies focused on the lived experience of people with MUPS are missing, except for several meta-studies focused specifically on CFS. One of them is a systematic review on the expressed needs of people with CFS by Drachler et al. (Citation2009), who found that these patients tend to report the following needs: (1) to make sense of symptoms and gain a diagnosis, (2) for respect and empathy from service providers, (3) for positive attitudes and support from family and friends, (4) for information about the diagnosis, (5) to adjust views and priorities, (6) to develop strategies to manage impairments and activity limitations, and (7) to develop strategies to maintain/regain social participation. In their qualitative meta-ethnography study, Larun and Malterud (Citation2007) came to similar conclusions. They emphasized that the sense of identity in patients with CFS can be endangered when the illness legitimacy is questioned. Furthermore, in their qualitative meta-ethnography, Pilkington et al. (2020) discovered how the “invisibility” of the illness undermines patients’ ability to gain support.

Since the existing reviews are limited to a single syndrome (i.e., CFS), the generalizability of their findings to other conditions remains uncertain. This study aimed to broaden the scope and synthesize the results of qualitative studies that explored the lived experiences of adults and adolescents with MUPS. We used the method of qualitative meta-summary (Sandelowski & Barroso, 2010) to derive common themes present across primary studies and, thereby, provide more robust findings that are not confined to the context of a single study.

Design

Database search and eligibility criteria

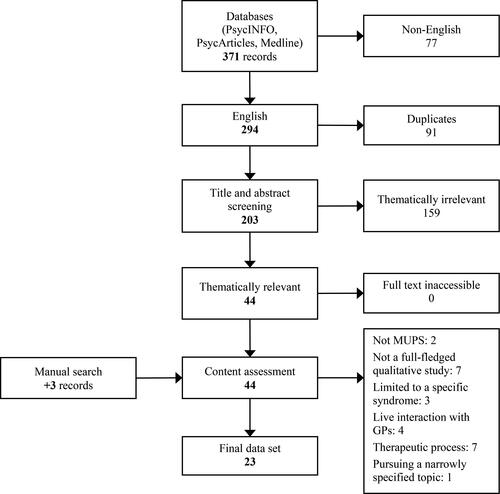

We conducted a systematic search in the PsycINFO, PsycARTICLES, and Medline databases (accessed through the EBSCOhost web portal) using the following string: TI (medically unexplained OR somatoform OR somatization OR somatisation OR psychosomatic OR functional syndrome OR functional symptom OR functional disorder OR bodily distress) AND AB (qualitative OR thematic OR phenomenological OR narrative). We faced a dilemma regarding the inclusion of specific functional syndromes, such as CFS, IBS, and PNES, in the string. We decided to exclude them because a preliminary search revealed that a string without specific syndromes already generated a substantial number of eligible studies and adding specific syndromes would yield a number of studies difficult to manage in a single meta-analysis. The search was finalized on January 11, 2019. Additional relevant studies were identified manually by checking the reference lists of included studies.

After removing duplicates and articles not written in English, we screened each article’s title and abstract to select articles potentially relevant for our study. After that, we obtained the full texts of these articles and assessed their content to determine their eligibility. An article was included in case (a) it was a full-fledged report of a qualitative study, (b) it explored the experience of living with MUPS from patients’ perspective (we excluded studies that were focused on the experience of being in psychotherapy or rehabilitation and studies that examined live interactions between patients and GPs from an external perspective), (c) the patient population was defined in terms of medically unexplained symptoms or somatoform disorders (i.e., not limited to a single syndrome), and (d) it focused on adults or adolescents. See for the flow chart.

Data analysis

First, we extracted descriptive information from each primary study’s method section, including sample characteristics, context of the study, and methods of data collection and analysis (see ). Second, we read the entire content of the primary studies’ results sections and selected those parts that pertained to the research question. Both direct quotations of the primary data and researchers’ summaries and interpretations were included in the analysis. However, if the results section contained parts based on other people’s perspectives (e.g., healthcare professionals or relatives), these were excluded from the analysis. Similarly, parts of the results section that were not based on the analysed data (e.g., references to other studies) were also excluded. Third, we repeatedly read all relevant parts of the data set and assigned codes to the text that captured the essence of patients’ experiences related to MUPS. Fourth, we sorted the codes based on their similarities and differences. Themes were created inductively by grouping codes that were similar in content. The codes were regrouped repeatedly until the resultant set of themes encompassed all codes and, thus, sufficiently reflected the scope of patients’ experience. Fifth, we counted the frequency of each theme (i.e., in how many primary studies the theme was present) and the intensity of each primary study (i.e., to how many themes a study contributed) according to Sandelowski and Barroso (2010). We did not eliminate any theme based on their frequency. Since, in several cases, two or more studies were based on the same data set, we merged these studies to avoid overestimating the influence of a single study (Timulak, Citation2009). All steps were conducted independently by both authors, and the results were discussed until they reached a consensus (Hill, Citation2012).

Table 1. Description of primary studies included in the meta-summary.

Results

Based on the meta-summary of 23 primary qualitative studies, we formulated eight common themes describing the lived experience of adults and adolescents with MUPS. See for the overview of the themes and their representation across primary studies. Since most of the analysed studies were conducted in the context of healthcare, we use the term patients here to refer to the participants. However, throughout the text, we strived to do justice to the fact that people find themselves in multiple social roles, all of which may be affected by the presence of MUPS.

Table 2. Representation of themes in the primary studies.

Need to feel understood: nobody knows how i feel inside

The subjective nature of unexplained physical concerns was experienced as an obstacle in communicating one’s experience to others. Not being able to ‘prove’ their suffering with a positive diagnosis, the patients were confronted with labels such as a ‘fraud,’ a ‘hypochondriac,’ a ‘malingerer,’ or a ‘hysteric.’ Too often, they felt their symptoms were not taken seriously.

Although present in many spheres of the patients’ lives, this issue was most clearly articulated in relation to medical care providers. The patients reported feelings of devastation when they felt they were not being understood and trusted by their physicians. Patients often felt that their first-person experiences of a symptom were not sufficient to earn physicians’ genuine interest, and physicians rarely inquired about patients’ daily lives and the emotional impacts of their condition. Physicians’ recourses to psychological explanations sometimes contributed to patients’ feelings of being dismissed as well.

Sometimes, listening was more important than receiving medical care for the patients. Some patients simply wanted to share their problems; diagnostic procedures were valued as a symbolic sign of a physician’s interest in the patient and evidence that the physician took their symptoms seriously. The patients appreciated when physicians showed openness, respect, empathy, a willingness to see their concerns within the complexity of their lives, and a sense of partnership in treatment planning. Feeling heard and having their suffering acknowledged as genuine and legitimate by their friends, relatives, and health professionals were hopes expressed across many patient accounts. These hopes were aptly condensed into a single sentence: ‘I just want permission to be ill’ (Nettleton, 2006, p. 1175).

Struggling with isolation: I need other people’s support

Patients in the primary studies often described a sense of isolation and loneliness. They felt that they could not freely express their concerns, since they did not want to ‘burden’ others with talks about their ailments, they expected a response of rejection or lacked proper words to describe their experience. Some of them tended to give up communicating their distress and strived to suppress their needs and feelings to reduce psychosocial distress. The invisibility of their symptoms and the absence of a ‘real’ diagnosis did not allow the patients to benefit from a socially validated sick role and thus deprived them of access to social support. This condition was further aggravated by daily activities and working capacity restrictions, which reduced opportunities to interact with people. The patients valued the support provided by their family and close friends. They welcomed opportunities to meet other people suffering from similar problems. Maintaining contact with their workplace was also perceived as a protective factor.

Patients sometimes perceived a barrier in communication with their physicians. They often felt that they could not convey the complexity of their illness to physicians and appreciated those who showed awareness of their problems’ breadth. Furthermore, symptoms were often connected with shame and embarrassment. Patients sometimes tended to hide their symptoms and suffering and pretended that ‘everything was normal.’ In a few studies, metaphors such as a ‘code of silence’ or an ‘emotional avoidance culture’ were used to describe a legacy that was passed on to patients during their childhood: rejection, humiliation, a lack of emotional validation, and other forms of adverse interpersonal experiences created an environment within which disclosure of feelings of distress was perceived as unsafe.

‘Sense of self’ in strain: the illness has changed me as a person

Life with MUPS changed the way patients experienced themselves. Living with pain, fatigue, sleep deprivation, and other physical difficulties left many patients paralyzed, exhausted, and more vulnerable to stress. Keeping up with their former activities and responsibilities became appreciably more difficult. However, based on patients’ narratives, we observed that an emotional and cognitive impact of the patients’ condition was no less important than the physical limitation. Patients described becoming more self-conscious as their physical symptoms began to occupy their minds. Since their ability to contribute to household and family management diminished, patients were confronted with feelings of uselessness. Becoming restricted and sometimes dependent in their daily lives threatened their sense of competence and identity.

A theme of self-doubt was also present throughout the primary studies. Being unable to find clinical confirmation of their symptoms left many patients feeling like a ‘fraud.’ Although on one level they knew that their suffering was real, sometimes they doubted their own experience and suspected themselves of ‘just being lazy’ or ‘imagining’ the symptoms. Despite their effort to recover, they often felt powerless to change their condition and meet their family and work commitments. The experience of a lack of improvement could then easily turn into feelings of self-blame and failure.

However, the illness was also sometimes appreciated as a source of personal growth. Some patients reflected on new insights, changes in their life values, and a sense of spiritual growth attributed to their illness. A determination to not give up on life or succumb to an illness identity helped them search for new meaning in their lives. Sometimes, they found a sense of purpose in helping others (for instance, educating other patients suffering from similar difficulties).

Facing uncertainty: my life has become more unpredictable

The unexplained nature of patients’ complaints was not only accompanied by uncertainty regarding the causes of their symptoms, but it was also often connected with a sense of unpredictability. Patients were confronted with an inability to anticipate the course of their illness, their treatment outcomes, or the process of returning to work. For patients whose condition was more chronic, work-life accommodation became increasingly difficult. However, the ‘unconfirmed’ status of their illness made it difficult for them to adopt the sick role.

Facing the unpredictable nature of their condition, patients tended to lose faith in change. The lack of a clear recovery trajectory left them in a state of confusion and lack of control. Their illness narration tended to be fragmented and chaotic: they had visited so many practitioners and had undergone so many examinations that they could barely preserve a sense of coherence and progression. They described their emotional state as a ‘roller coaster’ of hope for recovery on the one hand and frustration, fear, and despair on the other hand.

The intensity of their emotional reactions ranged from mild discomfort to a sense of devastation, as did patients’ ability to come to terms with their situation. Some of them described a process of accepting their restricted health and life situation and realizing that not everything in their life can be explained. They strived to look beyond the diagnosis and improve their quality of life within the context of their illness. However, others felt defeated by their symptoms and the medical system and found it hard to accept the reality of their symptoms in their lives and assume responsibility for their illness management. We may conclude that patients’ reactions seem to depend on the intensity of their symptoms and the quality of interactions with healthcare professionals.

Searching for explanations: I need to understand the symptoms

Faced with the unpredictable nature of their symptoms, patients strived to develop their own understanding of what was wrong. They constructed diverse explanations with various levels of sophistication. Some patients built their explanations on biophysical grounds, considering their symptoms to be a consequence of factors such as genetic predisposition, chemical imbalance, or immune deficiency. Some thought of the disease as a malign autonomous entity that had its existence beyond the patient’s own body and could influence others. Some patients believed that their symptoms were related to their personality or psychological factors, such as a low ability to handle pressure and lack of control in their lives. Some of them acknowledged the possible role of emotions, although very few drew specific connections between emotions and symptoms. In several studies, traumatic events in patients’ personal histories were considered a root of the current problems. Some patients sought causes in the social domain: poor relationships in their family or workplace, a lack of social support, stressful life events, and worries and uncertainty about the future, among others. Some patients emphasized the role of a lifestyle, such as the lack of routine and irregular daily living patterns. Some tended to attribute their symptoms to their work: overwork or unemployment and the implied negative socioeconomic context. For some patients, symptoms possessed a moral dimension—they represented, for instance, a personal weakness or a character flaw, or they were experienced as an expiation of feelings of guilt. These explanatory frameworks were not mutually exclusive. Often, patients hypothesized interaction of multiple factors: a traumatic explanation, for example, did not preclude belief in a physical cause. Generally, patients differed in their attitudes towards psychological explanations. While some rejected them as meaningless or uncomfortable, others accepted them as meaningful insights. Despite the diversity of explanations, the very effort to find a proper interpretation was a common thread winding through the primary studies. However, these explanations were often perceived as incomplete or unsatisfactory and were expressed with uncertainty.

Ambivalence about diagnosis: it can reassure, it can stigmatize

A central part of the patients’ experience was the search for a diagnosis. Often, this comprised a long series of physical investigations designed to rule out possible physical conditions step by step, without ever reaching any definite diagnosis. There seemed to be a deep ambivalence ingrained in this process.

On the one hand, a diagnosis was connected with a sense of relief in patients’ minds. Having the problem named was crucial for the social validation of patients’ condition. It allowed patients themselves to experience their symptoms as real and to present them as such to others. In other words, it provided patients with permission to be ill and legitimized their sick role. Furthermore, a diagnosis was perceived as a key to treatment, both in terms of directions and eligibility. Without a diagnosis, patients were often helpless in finding strategies and resources to cope with their symptoms (for instance, searching for a self-help group or conducting an internet search for treatment options).

On the other hand, not having a diagnosis also had an element of reassurance because ‘if they had something serious, doctors would have found it’ (Moulin et al., 2015b, p. 320). A diagnosis could confirm patients’ fears about having a serious illness, and therefore, a lack of a diagnosis provided hope. Having a diagnosis could change a patient’s perception of their condition ‘from being an isolated, though severe, nuisance in their life to a chronic condition, determining almost all their thoughts and actions’ (Risør, Citation2009, p. 515). A problem also arose if a diagnosis did not correspond to patients’ experiences or did not provide answers to patients’ questions. Psychiatric diagnoses were often not well accepted because of their stigmatizing aspect. While some patients accepted them as a legitimate explanation of their symptoms, for others, they carried messages such as ‘it’s all in your head,’ ‘it’s your fault,’ and ‘you have to fix it somehow yourself.’ Consequently, some patients tended to withhold information about psychosocial factors from their general practitioners, although they were aware of their importance.

Disappointed by healthcare: I lost my faith in medicine

Although some patients described a positive experience with treatment, in many primary studies, patients’ dissatisfaction with the healthcare system was discovered, aptly summarized as an experience of ‘reaching a “dead end” in the health care system’ (Kornelsen et al., 2016, p. 370). After a series of ‘unsuccessful’ investigations, patients tended to lose their hope that medicine would help them or, more personally, they lost faith in their practitioner’s competence. Some adults and adolescents described a sense of getting lost in the system as a consequence of engaging with different providers at different levels of healthcare. They complained that physicians did not communicate with each other enough, forcing patients to repeat the same information about their symptoms many times, and did not coordinate medical care. Some described a feeling of being actively discriminated against, rejected, or treated as a passive, depersonalized object of medical care.

Some patients reported a mismatch between their needs and the care offered by healthcare professionals. However, these unmet needs seemed to differ from patient to patient and were difficult to generalize. For instance, while some patients were comfortable with a psychological explanation, others felt misunderstood. While some understood that healthcare professionals have limited power and knowledge, others seemed to have an idealized image of medicine. While some expected their clinicians to prescribe medication, others were opposed to that. While some wanted their clinicians to suggest new ways of coping, others wanted them to avoid challenging their current way of managing their problems. Furthermore, patients seemed to have their own pace of adaptation to illness.

Active coping: I strive to take my life into my hands

Patients’ experiences with MUPS are inseparably interwoven into their efforts to manage their symptoms actively, sometimes with more success and sometimes with less. Many coping strategies have been described in primary studies. There was a large group of strategies connected with the attitude patients adopted towards their symptoms and body. Some strived to live in the ‘here and now,’ avoiding thoughts about the past and future or destructive thoughts and adopting a positive mindset or a detached view to protect themselves. Some invested themselves in relationships or socially gratifying and personally meaningful activities, such as care for grandchildren, helping others, or finding fulfilling activities in their spare time. Others mentioned developing body mindfulness, accepting the presence of symptoms in their life, disengaging from medical services, and finding personal ways of coping. Patients seemed to emphasize a need to regain control over their body and function as normally as possible within the constraints of their symptoms. Gaining more information and insight regarding MUPS helped them to move towards this goal. For some but not all patients, the illness turned into a transformative experience and contributed to perceived self-growth.

Discussion

This study aimed to gain a deeper understanding of the lived experience of adults and adolescents suffering from physical symptoms that had not been medically explained. We summarized findings from 23 primary qualitative studies. We identified eight themes reflecting these experiences: the need to feel understood, struggling with isolation, ‘sense of self’ in strain, facing uncertainty, searching for explanations, ambivalence about diagnosis, disappointed by healthcare, and active coping. None of the themes could be identified in all primary studies, possibly due to heterogeneous samples and different interview protocols. However, each of the themes was represented in at least half of the primary studies, suggesting their broad relevance. The themes are largely compatible with those derived by Drachler et al. (Citation2009), Larun and Malterud (Citation2007), and Pilkington et al. (2020) in their reviews and meta-studies on people with CFS, showing that there are many commonalities in the experiences of people suffering from MUPS, irrespective of the type of complaints. However, our results suggest that the ‘picture’ is more complicated in several respects. In our discussion of the findings, we focus on these complexities, stressing the interrelatedness of the themes, the differences among individuals suffering from MUPS, and their implications for practice. The experiential world of adults and adolescents with MUPS seems to be dominated by a sense of invalidation. They often feel ‘unheard’ and ‘unseen’ by their physicians and other people in their lives. Consequently, they experience feelings of isolation, loneliness, and a lack of support. Furthermore, the uncertainty of their condition often does not allow patients to make plans, and their future becomes more unpredictable. Disability, limitations, and changes in their social lives shatter their sense of competence and identity and challenge their mental balance. In a sample of patients with CFS, Clarke and James (Citation2003) described a process of gradually coming to terms with their illness, resulting in a ‘new self’ and a ‘new sense of the normal’ (p. 1391). However, in our primary studies, such salutary growth was not found in all patients, and some remained with a sense of devastation. Further research is needed to understand what facilitates positive personal growth as a response to such a life challenge.

MUPS seem to significantly impact patients’ social interactions, creating a vicious cycle of isolation and loneliness. Although it is often not explicitly recognized in the descriptions of patients’ experiences, patients seem to actively contribute to this sense of isolation by hiding their needs or withholding information. Patients’ perceived lack of support and feelings of being misunderstood, as well as their reluctance to burden others by opening their hearts to them, may cause them to withdraw from their social environment and isolate themselves. This negative loop must be recognized and changed to help patients regain their social life. Furthermore, there seem to be important differences related to the nature of the physical difficulties from which patients suffer. While patients in our primary studies tended to miss other people’s genuine interest and care, people with PNES complained about excessive care and lamented others’ overprotection (Rawlings & Reuber, Citation2016). We may hypothesize that, due to the uncontrolled nature of seizures, patients with PNES appear to need constant care. However, in patients with less visible and endangering symptoms, the suffering may remain unrecognized and unacknowledged by others.

One of the defining aspects of living with MUPS seems to be a constant search for an explanation. As a response to the sense of uncertainty, patients tend to develop their own theories about the origin of their symptoms, which may or may not be in accordance with the ones their physicians offer. Our findings echo those of other studies showing that while patients tend to prefer biological explanations (Nimnuan et al., Citation2001), some of them are well aware of the role of psychosocial factors (Sarudiansky et al., Citation2017).

The efforts to understand one’s condition are far from limited to a search for a diagnosis. In fact, patients seem to be profoundly ambivalent regarding a medical diagnosis. In the case of MUPS, a medical diagnosis often fails to provide a satisfying explanation and a straightforward course of satisfactory treatment (McMahon et al., Citation2012). Patients in the primary studies often expressed a fear of being labelled as “somatizers” or being diagnosed with a mental disorder. Similar observations were reported in studies on CFS (Drachler et al., Citation2009) or PNES (Rawlings & Reuber, Citation2016), although the CFS diagnosis is probably better accepted due to its lack of psychiatric connotations. Thus, in the case of MUPS, a medical diagnosis only partially serves the purposes of socially validating one’s subjective suffering and legitimizing the sick role.

As a result of their unacknowledged suffering and lack of effective treatment, many patients tended to lose their faith in medicine. Lamb et al. (Citation2012) found that patients who have greater challenges in accessing primary care, including MUPS patients, seek validation and normalization of their symptoms through talking to a physician. The popularity of alternative treatments, such as acupuncture, may be at least partly explained by the amount of time a practitioner devotes to listening to patients (Rugg et al., Citation2011). Clearly, the loss of faith in medicine was not always accompanied by a sense of resignation and patients searched for alternative ways to regain control over their lives.

In our study, the sense of being misunderstood was usually framed as a failure on the physician’s part. Again, however, there seems to be a reciprocal interaction between what a patient chooses to confide in a physician and how the physician responds. On the one hand, a patient may be discouraged from sharing any information of a psychosocial nature based on his or her previous experience with the healthcare system (Murray et al., Citation2016). On the other hand, patients’ withholding of relevant information about their condition may deprive physicians of clues that are essential for appropriate diagnostics and treatment. A step towards better trust and openness between a patient and a physician may require the destigmatization of psychosomatic issues.

However, what became apparent in our results was great variability in patients’ needs and expectations of healthcare providers. This variability places high demands on physicians’ skills in understanding these expectations and responding to them on an individual basis. The relational aspects of patient-physician interaction seem to be of utmost importance for patients suffering from MUPS.

Limitations

The results of our study are derived from the interpretations made by the authors of the primary studies rather than from the primary data, which is a common limitation in a qualitative meta-analysis (Timulak, Citation2009). It is more difficult to assess the groundedness of the themes in the participants’ actual experiences. Nevertheless, the frequency of the themes (55% to 85%) suggests that we successfully captured phenomena common to this group of people. To reduce the chance of an unreflected impact of our interests, preferences, and experiences on data interpretation, each of us conducted an independent analysis of the whole data set. The results are then based on thorough discussion and data checking.

The heterogeneity of the primary studies regarding their samples, context, data collection methods, and analytic procedures complicated the analysis. Some of the studies followed a narrowly specified research question (e.g., patients’ perceptions of medical explanations for somatization disorders), while others were focused more broadly. The studies also differed in the level of detail and elaboration of results—the higher the elaboration of themes, the more influential the study was. Consequently, the primary studies varied largely in the number of themes they saturated (the intensity ranged from 25% to 100%). Readers should also bear in mind that the frequency of themes does not represent the percentage of patients for whom a theme was relevant. A quantitative survey on a representative sample of patients would be required to obtain such findings. Furthermore, the exclusion of studies written in languages other than English may have biased our findings.

Conclusion

Based on a meta-summary of 23 qualitative studies, we described common themes reflecting the lived experience of adults and adolescents with MUPS. The results show that patients are active in their efforts to understand and cope with their problems far beyond the boundaries of medical care: they tend to search for information about their condition and alternative treatment approaches, often expressing disillusionment by the healthcare system. However, at the centre of patients’ experiences seems to be the importance of other people’s reactions to patients’ unexplained and often unprovable yet real suffering. Patients need to feel heard and validated in their suffering, irrespective of whether by a physician or a family member. It also became evident that the patient-physician relationship is not unidirectional since patients and physicians respond to each other in the construction of mutual expectations and attitudes. The reciprocity of patient-physician interaction should be studied in depth to clarify its role in the diagnostic and treatment process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Additional information

Funding

Funding

References

References marked with an asterisk indicate publications used as data in this study

- *Aamland, A., Werner, E. L., & Malterud, K. (2013). Sickness absence, marginality, and medically unexplained physical symptoms: A focus-group study of patients’ experiences. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care, 31(2), 95–100. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/02813432.2013.788274

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association.

- den Boeft, M., Huisman, D., Morton, L., Lucassen, P., van der Wouden, J. C., Westerman, M. J., van der Horst, H. E., & Burton, C. D. (2017). Negotiating explanations: doctor-patient communication with patients with medically unexplained symptoms-a qualitative analysis. Family Practice, 34(1), 107–113. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmw113

- *Burton, C., Mcgorm, K., Weller, D., & Sharpe, M. (2011). The interpretation of low mood and worry by high users of secondary care with medically unexplained symptoms. BMC Family Practice, 12(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-12-107

- Clarke, J. N., & James, S. (2003). The radicalized self: The impact on the self of the contested nature of the diagnosis of chronic fatigue syndrome. Social Science & Medicine, 57(8), 1387–1395. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00515-4

- *Claassen-van Dessel, N., R. Velzeboer, F., C. van der Wouden, J., den Boer, C., Dekker, J., & E. van der Horst, H. (2015). Patients’ perspectives on improvement of medically unexplained physical symptoms: A qualitative analysis. Mental Health in Family Medicine, 11(2), 42–48. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.25149/1756-8358.1102007

- Czachowski, S., Piszczek, E., Sowinska, A., & Hartman, T. C. O. (2012). Challenges in the management of patients with medically unexplained symptoms in Poland: A qualitative study. Family Practice, 29(2), 228–234. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmr065

- Dirkzwager, A. J., & Verhaak, P. F. (2007). Patients with persistent medically unexplained symptoms in general practice: Characteristics and quality of care. BMC Family Practice, 8(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-8-33

- Drachler, M. d L., Leite, J. C. d C., Hooper, L., Hong, C. S., Pheby, D., Nacul, L., Lacerda, E., Campion, P., Killett, A., McArthur, M., & Poland, F. (2009). The expressed needs of people with chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis: A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 9(1), 458. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-9-458

- *Dwamena, F. C., Lyles, J. S., Frankel, R. M., & Smith, R. C. (2009). In their own words: Qualitative study of high-utilising primary care patients with medically unexplained symptoms. BMC Family Practice, 10(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-10-67

- Fink, P. (1992). Surgery and medical treatment in persistent somatizing patients. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 36(5), 439–447. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3999(92)90004-L

- Haller, H., Cramer, H., Lauche, R., & Dobos, G. (2015). Somatoform disorders and medically unexplained symptoms in primary care. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International, 112(16), 279–287.https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2015.0279

- Harsh, J., Hodgson, J., White, M. B., Lamson, A. L., & Irons, T. G. (2016). Medical residents’ experiences with medically unexplained illness and medically unexplained symptoms. Qualitative Health Research, 26(8), 1091–1101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315578400

- Hill, C. E. (2012). Consensual qualitative research: A practical resource for investigating social science phenomena. American Psychological Association, Washington, DC.

- *Hills, J., Lees, J., Freshwater, D., & Cahill, J. (2018). Psychosoma in crisis: An autoethnographic study of medically unexplained symptoms and their diverse contexts. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 46(2), 135–147. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2016.1172201

- *Houwen, J., Lucassen, P. L., Stappers, H. W., Assendelft, W. J., Dulmen, S. V., & Hartman, T. C. O. (2017). Improving GP communication in consultations on medically unexplained symptoms: A qualitative interview study with patients in primary care. The British Journal of General Practice : The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 67(663), e716–e723. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp17X692537

- Johansen, M.-L., & Risor, M. B. (2017). What is the problem with medically unexplained symptoms for GPs? A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies . Patient Education and Counseling, 100(4), 647–654. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2016.11.015

- *Junod Perron, N., & Hudelson, P. (2006). Somatisation: Illness perspectives of asylum seeker and refugee patients from the former country of Yugoslavia. BMC Family Practice, 7(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-7-10

- *Kornelsen, J., Atkins, C., Brownell, K., & Woollard, R. (2016). The meaning of patient experiences of medically unexplained physical symptoms. Qualitative Health Research, 26(3), 367–376. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732314566326

- Lamb, J., Bower, P., Rogers, A., Dowrick, C., & Gask, L. (2012). Access to mental health in primary care: A qualitative meta-synthesis of evidence from the experience of people from ‘hard to reach’ groups. Health (London, England : 1997), 16(1), 76–104. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459311403945

- Larun, L., & Malterud, K. (2007). Identity and coping experiences in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: A synthesis of qualitative studies. Patient Education and Counseling, 69(1–3), 20–28. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2007.06.008

- *Lidén, E., Björk-Brämberg, E., & Svensson, S. (2015). The meaning of learning to live with medically unexplained symptoms as narrated by patients in primary care: A phenomenological-hermeneutic study. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 10(1), 27191. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v10.27191

- *Lind, A. B., Delmar, C., & Nielsen, K. (2014). Searching for existential security: A prospective qualitative study on the influence of mindfulness therapy on experienced stress and coping strategies among patients with somatoform disorders. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 77(6), 516–521. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.07.015

- McMahon, L., Murray, C., & Simpson, J. (2012). The potential benefits of applying a narrative analytic approach for understanding the experience of fibromyalgia: A review. Disability and Rehabilitation, 34(13), 1121–1130. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2011.628742

- *Morse, D. S., Suchman, A. L., & Frankel, R. M. (1997). The meaning of symptoms in 10 women with somatization disorder and a history of childhood abuse. Archives of Family Medicine, 6(5), 468–476. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/archfami.6.5.468

- *Moulin, V., Akre, C., Rodondi, P.-Y., Ambresin, A.-E., & Suris, J.-C. (2015a). A qualitative study of adolescents with medically unexplained symptoms and their parents. Part 1: Experiences and impact on daily life. Journal of Adolescence, 45, 307–316. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.10.010

- *Moulin, V., Akre, C., Rodondi, P.-Y., Ambresin, A.-E., & Suris, J.-C. (2015b). A qualitative study of adolescents with medically unexplained symptoms and their parents. Part 2: How is healthcare perceived?Journal of Adolescence, 45, 317–326. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.10.003

- Murray, A. M., Toussaint, A., Althaus, A., & Löwe, B. (2016). The challenge of diagnosing non-specific, functional, and somatoform disorders: A systematic review of barriers to diagnosis in primary care. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 80, 1–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.11.002

- *Nettleton, S. (2006). ‘I just want permission to be ill’: Towards a sociology of medically unexplained symptoms. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 62(5), 1167–1178. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.07.030

- *Nettleton, S., O’Malley, L., Watt, I., & Duffey, P. (2004). Enigmatic illness: Narratives of patients who live with medically unexplained symptoms. Social Theory & Health, 2(1), 47–66. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/palgrave.sth.8700013

- Nettleton, S., Watt, I., O’Malley, L., & Duffey, P. (2005). Understanding the narratives of people who live with medically unexplained illness. Patient Education and Counseling, 56(2), 205–210. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2004.02.010

- Nimnuan, C., Rabe-Hesketh, S., Wessely, S., & Hotopf, M. (2001). How many functional somatic syndromes?Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 51(4), 549–557. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(01)00224-0

- *Nunes, J., Ventura, T., Encarnação, R., Pinto, P. R., & Santos, I. (2013). What do patients with medically unexplained physical symptoms (MUPS) think? A qualitative study. Mental Health in Family Medicine, 10(2), 67–79.

- *Østbye, S. V., Kvamme, M. F., Wang, C. E. A., Haavind, H., Waage, T., & Risør, M. B. (2020). Not a film about my slackness’: Making sense of medically unexplained illness in youth using collaborative visual methods. Health: An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness and Medicine, 24(1), 38–58. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459318785696

- *Peters, S., Rogers, A., Salmon, P., Gask, L., Dowrick, C., Towey, M., Clifford, R., & Morriss, R. (2009). What do patients choose to tell their doctors? Qualitative analysis of potential barriers to reattributing medically unexplained symptoms. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 24(4), 443–449. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0872-x

- *Peters, S., Stanley, I., Rose, M., & Salmon, P. (1998). Patients with medically unexplained symptoms: Sources of patients’ authority and implications for demands on medical care. Social Science & Medicine ( Medicine), 46(4–5), 559–565. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(97)00200-1

- Pilkington, K., Ridge, D. T., Igwesi-Chidobe, C. N., Chew-Graham, C. A., Little, P., Babatunde, O., Corp, N., McDermott, C., & Cheshire, A. (2020). A relational analysis of an invisible illness: A meta-ethnography of people with chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME) and their support needs. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 265, 113369. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113369

- Rawlings, G. H., & Reuber, M. (2016). What patients say about living with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: A systematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Seizure, 41, 100–111. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seizure.2016.07.014

- Ring, A., Dowrick, C., Humphris, G., & Salmon, P. (2004). Do patients with unexplained physical symptoms pressurise general practitioners for somatic treatment? A qualitative study. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 328(7447), 1057. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.38057.622639.EE

- *Risør, M. B. (2009). Illness explanations among patients with medically unexplained symptoms: Different idioms for different contexts. Health, 13(5), 505–521. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459308336794

- Rugg, S., Paterson, C., Britten, N., Bridges, J., & Griffiths, P. (2011). Traditional acupuncture for people with medically unexplained symptoms: A longitudinal qualitative study of patients’ experiences. British Journal of General Practice, 61(587), e306–e315. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp11X577972

- *Salmon, P., Peters, S., & Stanley, I. (1999). Patients’ perceptions of medical explanations for somatisation disorders: Qualitative analysis. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 318(7180), 372–376. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.318.7180.372

- Salmon, P., Ring, A., Dowrick, C. F., & Humphris, G. M. (2005). What do general practice patients want when they present medically unexplained symptoms, and why do their doctors feel pressurized?Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 59(4), 255–260. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.03.004

- Sandelowski, M., & Barroso, J. (2010). Handbook for synthesizing qualitative research. Springer.

- Sarudiansky, M., Lanzillotti, A. I., Areco Pico, M. M., Tenreyro, C., Scévola, L., Kochen, S., D’Alessio, L., & Korman, G. P. (2017). What patients think about psychogenic nonepileptic seizures in Buenos Aires, Argentina: A qualitative approach. Seizure, 51, 14–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seizure.2017.07.004

- Smith, R. C., & Dwamena, F. C. (2007). Classification and diagnosis of patients with medically unexplained symptoms. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 22(5), 685–691. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-006-0067-2

- *Sowińska, A., & Czachowski, S. (2018). Patients’ experiences of living with medically unexplained symptoms (MUS): A qualitative study. BMC Family Practice, 19(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-018-0709-6

- Timulak, L. (2009). Meta-analysis of qualitative studies: A tool for reviewing qualitative research findings in psychotherapy. Psychotherapy Research : Journal of the Society for Psychotherapy Research, 19(4–5), 591–600. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10503300802477989

- Wessely, S., & White, P. D. (2004). There is only one functional somatic syndrome. The British Journal of Psychiatry : The Journal of Mental Science, 185(2), 95–96. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.185.2.95

- *Whitley, R., Kirmayer, L. J., & Groleau, D. (2006). Public pressure, private protest: Illness narratives of West Indian immigrants in Montreal with medically unexplained symptoms. Anthropology & Medicine, 13(3), 193–205. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13648470600863548