ABSTRACT

Aims

To identify and synthesise peer-reviewed, published literature reporting perceived barriers and facilitators associated with cervical cancer screening attendance in EU member states with organised population-based screening programmes.

Methods

Quantitative and qualitative studies reporting perceived barriers/facilitators to attendance for cervical cancer screening were searched for in databases Embase, HMIC, Medline and PsycInfo. Data were extracted and deductively coded to the Theoretical Domains Framework domains and inductive thematic analysis within domains was employed to identify specific barriers or facilitators to attendance for cervical cancer screening.

Results

38 studies were included for data extraction. Five theoretical domains [‘Emotion’ (89% of the included studies), ‘Social influences’ (79%), ‘Knowledge’ (76%), ‘Environmental Context and Resources’ (74%) and ‘Beliefs about Consequences’ (68%)] were identified as key domains influencing cervical cancer screening attendance.

Conclusion

Five theoretical domains were identified as prominent influences on cervical cancer screening attendance in EU member states with organised population-based screening programmes. Further research is needed to identify the relative importance of different influences for different sub-populations and to identify the influences that are most appropriate and feasible to address in future interventions.

Introduction

Cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer among women and poses a significant threat to women’s health across the globe (WHO, Citation2019). An estimated 58,373 women are diagnosed with cervical cancer annually in Europe, and approximately 24,400 die from this illness every year (Bruni et al., 2019). Practically all cases (98%) of cervical cancer are caused by sexually transmitted infections with at least 14 types of human papilloma virus (HPV). Many men and women are infected with HPV when they engage in sexual activity for the first time and most infections clear up within months. Nevertheless, certain types of HPV infections may persist and progress into cervical cancer in women. Two types of HPV (HPV16 and HPV18) are considered particularly high risk, as they are responsible for approximately 70% of all pre-cancerous lesions and cervical cancers. Precancerous HPV infections take several years to evolve, which is why cervical cancer is most common among women aged 35–50 (WHO, Citation2019).

Fortunately, cervical cancer can often be effectively prevented and cured given that cancerous lesions have the potential to be detected early through cervical cancer screening (CCS) (WHO, 2020). Liquid based cytology and the Papanicolau test are widely used to screen for precancerous lesions and cervical cancer. Organised, Population-based Cervical Cancer Screening Programmes (PCCSP) coordinating CCS every three to five years can prevent up to 80% of all cervical cancer cases (Arbyn et al., Citation2008; ENCR, Citation2016). In 2003, the Council of the European Union designated principles of the implementation of national, population-based screening programmes for various forms of cancers, including cervical cancer (European Commission, 2003; Ponti et al., Citation2017). Although screening policies vary between countries, many EU member states have implemented PCCSPs, which contribute to a substantial reduction in the number of cases of and deaths from cervical cancer (ENCR, Citation2016). Despite the proven effectiveness of such screening programmes, many countries have seen a suboptimal uptake of their PCCSPs. Uptake rates vary greatly between countries and in some EU member states uptake rates have fallen (OECD/European Union, Citation2018). For example, in the UK, 28% of all eligible women failed to attend screening in 2018 (Screening & Immunisations Team, NHS Digital, 2018). This implies a missed opportunity to further reduce the number of women who become ill and die from cervical cancer.

A significant amount of research has been devoted to exploring women’s reasons for not attending CCS (Waller et al., Citation2009; Marlow et al., Citation2019; Holroyd et al., Citation2004, Walsh, Citation2006; Bennett et al., Citation2018; Wilding et al., Citation2020). Qualitative and quantitative studies have suggested a wide range of barriers and facilitators influencing screening attendance. Identified barriers and facilitators range from environmental and practical factors (e.g. lack of time, accessibility to clinic, inconvenient appointment times, invitation issues and economic costs associated with attending screening) (Waller et al., Citation2009; Marlow et al., Citation2019; Bennett et al., Citation2018; Wilding et al., Citation2020) to psychological determinants such as emotions (e.g. embarrassment, fear, shame and trauma), as well as (lack of) knowledge about CCS and cervical cancer (Waller et al., Citation2009; Walsh et al., 2006; Marlow et al., Citation2019; Wilding et al., Citation2020) and social influences (e.g. social norms, culture, identity) (Holroyd et al., Citation2004). Although such primary research studies have identified a great number of barriers and facilitators influencing screening attendance, it is important to develop a comprehensive understanding of the relative prominence of the barriers and facilitators that are found to influence CCS attendance across studies. This understanding will support the development of more effective interventions that target the most important influences on the behaviour of attendance for CCS.

Successful behaviour change interventions are based upon a rigorous and theoretically informed analysis of the target behaviour and identification of the key influences on it (Michie et al., Citation2011). The Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) was developed to provide researchers and practitioners with guidance on how to systematically identify and categorise barriers and facilitators that influence a target behaviour (Michie et al., 2005; Cane et al., Citation2012). The TDF is a synthesis of 128 theoretical constructs from 33 different theories relevant to implementation issues. The framework consists of 14 theoretical domains that cover factors reflecting the physical environment, the social environment, individual motivation and capability with each domain representing a number of related theoretical constructs (Cane et al., 2011). The TDF has been applied in many different contexts to support exploration of barriers and facilitators of target behaviours and inform intervention design (Atkins et al., Citation2017). Patient uptake of prevention programmes for cardiovascular disease and diabetes (Shaw et al., Citation2016) and medication adherence of diverse medications (Arden et al., Citation2019; Presseau et al., Citation2017) are examples of research that apply the TDF to focus on and analyse patient behaviour.

The TDF is increasingly applied as a coding guide to identify and categorise barriers and facilitators in systematic reviews. For example, the TDF has previously been used to code barriers and facilitators to attendance for diabetic retinopathy screening (Graham-Rowe et al., Citation2018), medication adherence among individuals with bipolar disorder (Prajapati et al., Citation2019), the implementation of physical activity policies in schools (Nathan et al., 2018) and the implementation of prescribing guidelines (Paksaite et al., Citation2021). Since plenty of independent research papers examining barriers and facilitators to CCS attendance in EU member states exist, a systematic review on the topic would provide a means to identify and analyse a great number of factors that influence attendance. Therefore, the present study will apply the TDF in a systematic review context to identify perceived barriers and facilitators to attendance for CCS from the perspective of individuals invited to participate in PCCSPs in EU member states.

The specific aims of this systematic review are:

To identify and synthesise peer-reviewed, published literature reporting perceived barriers and facilitators associated with CCS attendance in EU member states with organised PCCSP.

To extract reported barriers and facilitators and systematically categorise these according to the TDF domains.

To identify and depict the prominence of TDF domains found in the literature that influence attendance for CCS in EU member states.

To identify barriers and facilitators within domains concerning CCS attendance in EU member states.

Methods

This systematic review was written in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., Citation2009) and was registered in OSF (reference: https://osf.io/63g4r).

Study inclusion and exclusion criteria

Participants

The target population was females aged 25–64 invited to CCS. Eligible populations live in EU-member states with PCCSPs. Only studies examining the perspective of individuals invited to CCS were included. Perspectives from other types of informants (e.g. health care professionals) were excluded since only the barriers/facilitators perceived by the target group were relevant.

Study design

Peer reviewed studies were included if they (1) reported or investigated perceived barriers that might inhibit attendance for CCS and/or (2) reported or investigated perceived facilitators that might facilitate attendance for CCS. Eligible barriers/facilitators had to be modifiable, meaning that they needed to have the potential to be targeted by a systematically developed behaviour change intervention. Therefore, socio-demographic factors influencing screening attendance such as age, ethnicity, socioeconomic status (SES) or location were excluded unless they were reported as a perceived barrier or facilitator (e.g. lack of money to travel to appointment). Studies assessing effectiveness or efficacy of existing interventions were excluded unless they included information on perceived barriers and facilitators. Abstracts, editorials, supplementary documents, commentaries, summaries, systematic and non-systematic reviews and overviews were excluded. Only studies reported in English were included.

Context

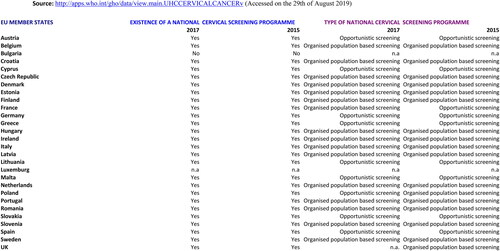

This review identified EU member states with PCCSP by using the World Health Organisation’sFootnote1 (WHO) data on the existence of cervical cancer screening programmes in different countries. Appendix 1 illustrates the WHO data representing whether EU member states had national cervical cancer screening programmes in 2015 and 2017 (representing the most up to date information when the search was run) and the type of programme (opportunistic screening or organised PCCSP). Studies published before the introduction of a PCCSP in a given country were excluded. Countries with opportunistic screening programs were excluded as this type of screening programme is not necessarily checked or monitored. The clinical procedures relevant for the target behaviour were: (1) Papanicolaou test (also known as Pap smear) and (2) Human papillomavirus (HPV) testing. Self-examination (e.g. self-collected/self-administered tests), visual inspection and second stage screening were excluded.

Search strategy

The search strategy was developed using a combination of search terms and relevant synonyms, which can be grouped into four categories: (1) cervical cancer (e.g. cervix cancer) (2); screening (e.g. cervical smear; cervical screening; smear test; Papanicolaou test; pap smear; cervical cytology; smear test); (3) attendance (e.g. non-attendance; participation); (4) potential barriers and facilitators (e.g. obstacles; enablers; determinants). Boolean operators were used to combine the facets (e.g. “AND”; “OR”). Studies were searched for in the databases Embase, HMIC, Medline and PsycInfo through the search interface Ovid. Various combinations of search terms were piloted and the second reviewer (D.D.L.) provided an additional perspective on the different search strategies. Nine peer-reviewed studies of high relevance for the review (previously identified through scoping searches) were searched for in the results in order to ensure that the search strategy was sufficiently inclusive. Appendix 2 depicts the nine reference studies. A search strategy that identified all nine papers was generated and the final search was run in Ovid on the 24th of May 2019. Appendix 3 depicts the final search strategy.

Study selection process

The number of records generated by the search strategy was de-duplicated in Ovid. Remaining records were exported to the reference management software Endnote, and any remaining duplicates were removed manually. Following deduplication, the first reviewer (G.S.) screened all titles and abstracts against the inclusion and exclusion criteria (summarised in ). Studies were coded as being either (a) ineligible for full text screening, or (b) potentially eligible for full text screening. To ensure screening reliability, the second reviewer (D.D.L.) independently screened 10% of the titles and abstracts. Following title and abstract screening, G.S. evaluated all papers included for full text screening to decide whether papers would be included or excluded for data extraction. The second reviewer (D.D.L.) independently screened 10% of the references included for full text screening. The two reviewers’ respective assessments were compared, and any disagreements were discussed until consensus was reached.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Data extraction

A data extraction form was developed in Microsoft Excel. G.S. developed the form and the second reviewer (D.D.L.) provided feedback on the structure and adjustments were made accordingly. The final data extraction form included the following study characteristics: author(s), year of publication, country, study aim(s), study design, participants, method of data collection, method of analysis, reported barriers, reported facilitators and supporting verbatim quotes for qualitative studies.

G.S. extracted data for all included studies. Extracted data were tabulated in the data extraction form and were categorised as representing either: (1) barriers; (2) facilitators; or (3) “general findings” (indicating an indistinct mixture of facilitators and barriers). Theme headings, theme descriptions and supporting verbatim quotes were extracted from qualitative studies. Authors’ interpretations of qualitative results were included providing these were presented in the results section. From quantitative studies, data from tables representing questionnaire/survey responses, reported perceived barriers/facilitators (in %) and predictors of and statistically significant associations with attendance/non-attendance were extracted.

D.D.L. checked the extracted data for all included studies and provided suggestions for amendment where necessary to increase the consistency and reliability of the extraction.

Quality assessment

Although no studies were excluded based on quality, appropriate quality assessment tools were applied to give an overview of methodological rigour and whether individual studies were affected by significant bias. Qualitative studies were assessed by G.S. using the “Critical Appraisal Skills Programme” (CASP, 2018) tool. Individual study average quality score was assigned using one of three quality categories: low (10 points), moderate (20 points) and high (30 points). Quantitative studies or studies using mixed methods were assessed using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) (Hong et al., Citation2018). Since MMAT discourages overall quality scores being calculated for individual studies, G.S. assessed quantitative studies by making ratings of each criterion. D.D.L. checked G.S.’s quality scorings for 25% of the quantitative and qualitative studies and amendments were made where appropriate.

Analysis

Extracted data on barriers and facilitators were deductively coded to the TDF domains and inductive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) within domains was employed to identify and describe specific barriers and facilitators to attendance for CCS. Summary statistics illustrating study characteristics, domain frequency (as an indicator of prominence across included studies) and frequencies of barriers and facilitators were created. Further detail of each component of the analysis is provided below.

Deductive analysis

Data were coded through a framework analysis approach (Gale et al., Citation2013) using the TDF as a coding framework. Appendix 4 illustrates the coding manual with definitions for each of the 14 domains from the TDF, which was developed to ensure consistency and reliability in coding for the deductive analysis. G.S. and D.D.L. developed the coding manual jointly by mapping data fragments to distinct domain(s) and made iterations until consensus was reached. During coding, G.S. and D.D.L. each coded all data fragments to the TDF domain(s) that was judged to be most appropriate. For example, extracted data illustrating “40% claimed no knowledge of cervical cancer” was coded to the “Knowledge” domain. Sometimes data were judged to concurrently represent more than one of the TDF domains, which resulted in the data being coded to multiple domains. For example, the following quote stating “You have feeling that if it’s a cancer it’s not treatable, so I leave it, I don’t want to know.” was coded to both the “Knowledge” and “Beliefs about consequences” domains.

Inductive analysis

A thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) was conducted on the data fragments within each individual TDF domain. This involved the first reviewer (G.S.) coding each data fragment and then grouping codes into global themes and sub-themes. For example, one global theme generated within the Emotion domain was “Fear” which contained the following sub-themes: “Fear/anxiety of screening procedure”; “Fear of cancer/test results”; “Fear related to interaction with Health Care Professional (HCP)”; “Unspecified fear/anxiety”. The second reviewer (D.D.L.) reviewed the inductive analysis and commented on whether the generated themes were sufficiently distinct and whether data had been appropriately coded. G.S. made adjustments accordingly.

Results

Data selection process

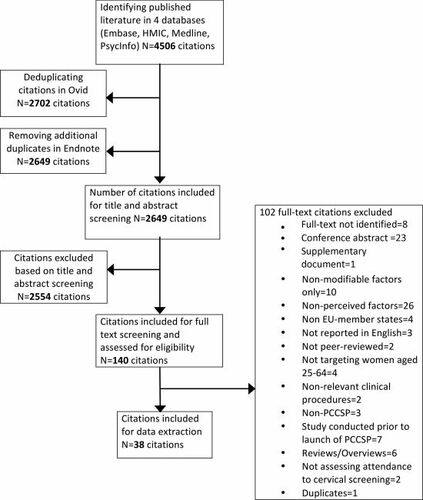

provides an overview of the study selection process. The search strategy generated 4506 references. Following de-duplication in Ovid, 2702 records remained, of which all were exported to Endnote. 2649 records eligible for title and abstract screening remained after manual deduplication in EndNote. The title and abstract screening resulted in 140 references included for full-text screening. 102 studies were excluded at full text stage, resulting in 38 studies included for data extraction. References for all 38 studies can be found in Appendix 5.

Results from reliability checks

The second reviewer checked 265 of the 2649 (10%) studies included for title and abstract screening. Initially the reviewers disagreed on the eligibility of 8 out of 265 papers (3%) for full text screening, however all discrepancies were discussed until consensus was reached and amendments were made accordingly. Of the 10% of the 140 studies (n = 14) included for full text screening, the reviewers initially disagreed on the eligibility of 4 papers (28.5%). However, the discrepancies were due to misunderstandings regarding whether: (i) a given country was part of the EU; (ii) the age of participants was eligible or not; (iii) determinants reflected perceived barriers/facilitators or not. Following clarification the reviewers reached consensus and no disagreements remained.

Quality assessment of included studies

Detailed results of the quality assessment of included studies are presented in Appendix 6 for qualitative studies and Appendix 7 for quantitative/mixed studies, respectively. Because two dissimilar assessment tools with different scorings were applied in the quality assessment, no effort was made to summarise the respective qualitative assessments for qualitative and quantitative/mixed studies. The second reviewer assessed 9 studies in total and any discrepancies were resolved through discussion and learning applied across the whole sample of studies.

Study characteristics

illustrates characteristics of the included studies. There was a similar proportion of qualitative and quantitative studies (44.7% qualitative versus 42.1% quantitative studies). A majority of the papers were conducted in the United Kingdom (55.3%), followed by Sweden where nearly a fifth (18.4%) of the studies were performed. Nearly half (47.3%) of the included studies targeted minority populations in terms of religious background, age, ethnicity, social class, health status and sexual history.

Table 2. Characteristics of included studies.

Deductive analysis

Domain frequency

presents the 14 theoretical domains in rank order. This order illustrates the number of studies that included data that were coded to a given domain. Emotion was the most frequently identified domain among the included studies (34 studies), followed by Social influences (30 studies); Knowledge (29 studies); Environmental Context and Resources (28 studies); Beliefs about Consequences (26); Intentions (15 studies); Optimism (14 studies); Skills (12 studies); Goals (12 studies); Memory, Attention and Decision Processes (10 studies); Social Professional Role and Identity (8 studies); Beliefs about Cpabilities (3 studies); Reinforcement (2 studies). The fourteenth domain Behavioural Regulation was not identified in the extracted data of any of the 38 included studies.

Table 3. Frequencies of number of studies identified by each TDF domain presented in rank order, frequencies of barriers and facilitators and number of identified themes and sub-themes.

Inductive analysis

provides an overview of the number of global themes and sub-themes generated by the inductive analysis. Appendix 5 presents all of the identified global themes and sub-themes in detail, alongside frequencies of barriers, facilitators, relevant studies, sub-populations (when relevant), sample quotations and data fragments. Below follows a detailed description of the five domains that were identified most frequently by the deductive analysis. These five domains are Emotion, Social Influences, Knowledge, Environmental Context and Resources and Beliefs about Consequences. A narrative description of the global themes and sub-themes within these domains that were generated by the inductive analysis is presented below. Both global themes and sub-themes are narrated based on their relative frequency in terms of the number of studies represented within each individual global theme and sub-theme.

Emotion (34 studies)

Theme: Fear (30 studies)

Fear was a prominent emotional barrier reported by women in most studies. Many women expressed fear of the screening procedure itself. Some women expressed a more general fear or anxiety against the test “Fear of the test procedure (17.9%)” (Ekechi et al., Citation2014, p. 5) although many explicitly expressed being afraid that the procedure would cause them pain: “So the pain, does it hurt? I was worried about that” (Azerkan et al., Citation2015, p. 8). Another barrier was being afraid of potential results from a smear test:” I am so damned afraid … I don’t want there to be anything wrong” (Blomberg et al., Citation2008, p. 564) which was associated with non-attendance in quantitative studies “[…] Non-attendees worry more about the result (t = −2.8) than attendees” (Knops-Dullens et al., Citation2007, p. 441). Some women reported fears related to interacting and/or communicating with the HCP “I am worried I might have difficulties communicating with the doctor/nurse (16%)” (Shah et al., Citation2006, p. 50).

Theme: Self-Consciousness (25 studies)

Emotions related to self-consciousness were articulated to inhibit CCS attendance in more than half of the included studies. The most commonly identified emotion within this theme was embarrassment as many women reported that they perceive the procedure to be embarrassing: “Those from South Asian backgrounds were more likely to agree that smear tests were embarrassing (71–91% versus 28% compared with White British women”) (Marlow et al., Citation2015, p. 836) and “The test itself was often talked about in negative terms. Some women described feelings of extreme embarrassment […]” (Waller et al., Citation2012, p. 29). For some women the screening invitation was reported to induce feelings of embarrassment or shyness: “When the letter arrives I would feel shy and not bother going” (Box, Citation1998, p. 7). Perceiving that the test situates the woman in a vulnerable position was another reported barrier to CCS in some studies: “Power disparities (29%) (feelings of vulnerability and lack of control)” (Cadman et al., Citation2012). Shame was another reported emotion hampering screening attendance in a number of studies.

Theme: Negative past experiences (15 studies)

Some women reported previous negative screening experiences that had induced strong emotional reactions, which inhibited them from attending screening again. These emotional experiences usually involved a combination of physical pain, emotional stress and a perception that the test taker was unresponsive to the needs and the reactions of the patient. A woman provided an account of her emotionally distressing screening experience: “It hurt so much that they held me down, that he didn’t stop it then. Forced up in some way that I wanted to get up higher. I moved and they held on to me, I was pinned down. They used force on me, that’s how I felt. I can picture myself as a victim who had to suffer torture” (Oscarsson et al., Citation2008, p. 30).

Social influences (30 studies)

Theme: Health care professionals (25 studies)

The gender of the test taker was the most frequently reported factor by women within this theme. Having a male HCP was a frequently reported barrier to screening: “35% said that a male smear taker would be a barrier to their attendance for a cervical smear test. Of women who made this statement, 30% attended for a smear compared with 42% who did not consider a male smear taker a barrier” (Walsh Citation2006, p. 295) and having a female practitioner was a frequently reported facilitator to CCS “Most women preferred a female doctor or nurse to carry out the examination (82%)” (Shah et al., Citation2006, p. 50). HCPs’ perceived empathy and sensitivity or lack thereof was discussed in several studies. Some women mentioned that perceived negative treatment and behaviour of HCPs constituted barriers to CCS. HCPs were often reported to be perceived as indifferent, impatient and unresponsive to women’s needs and reactions during screening, which constituted a barrier to future screenings: “[…] the second time I went, I don’t know quite what happened and I thought I was gonna die from the pain from this woman and then … and I did cry. I mean, it hurt that much. And she shouted at me and called me a baby, err, which was just dreadful” (Marlow et al., Citation2019, p. 7). Many women expressed they wanted HCPs to demonstrate more patience, understanding and sensitivity during the screening appointment, as this would improve the interaction between the patient and the HCP, which would consequently facilitate CCS attendance: “I think if they’re quite friendly and they relax you, it doesn’t make it so uncomfortable … if they could take a bit more time and you know, understand, sometimes they don’t have any patience or they just want you in and out.” (Marlow et al., Citation2015, p. 251). Another central barrier and facilitator expressed by women in several studies was the importance of establishing good and clear communication during the screening appointment. Women requested being more directly involved in the procedure and to be given explanations of what the test involves in terms of e.g. pain and discomfort: “For [the doctor] it was something very routine but for the person who is coming for the first time for the test … she was not trying … to explain something or be helpful.” (Jackowska et al., Citation2012, p. 234)

Theme: Lack of support (9 studies)

Perceived absence or presence of social support was expressed to have an impact on women’s inclination to attend CCS. This theme relates to the presence or lack of support from social relationships and the broader social community. Support originating from the immediate social context such as family and friends was a facilitator to attendance when present and a barrier if absent. Results from a quantitative study showed that women who were expected to gain someone else’s permission were less likely to attend CCS than those who felt able to decide for themselves: “Women who could decide for themselves whether to take a screening test (1.70, 4.14–2.53, as compared to those needing to have someone else’s permission) had higher odds of having attended screening” (Andreassen et al., Citation2018, p. 612). Encouragement and practical support from family members, significant others and friends were reported as facilitators to CCS attendance, for example one woman explained that her mother reminded her about attending screening: “I think it was my Mum who said it, ‘you must go and do it, it is very important’.” (Azerkan et al., Citation2015, p. 8). Perceiving that one’s community is supportive of CCS was a reported facilitator to screening, especially among ethnic minority women: “I think that Somalis working in the community should be trained up to help in this. The authorities should train them and give them jobs to help Somali women access this service. If that could be done, the person will feel that they’d understand each other, have the same nationality, that person will feel at ease to attend” (Abdullahi et al., Citation2009, p. 683).

Knowledge (29 studies)

Theme: Awareness of cervical cancer (22 studies)

Lack of awareness about cervical cancer constituted the most common barrier to CCS attendance within the Knowledge domain. It was evident in quantitative and qualitative studies that women lacked knowledge of cervical cancer. For example in one study “40% [of the respondents] claimed no knowledge of cervical cancer” (Neilson & Jones, Citation1998, p. 573). It was also common among women to demonstrate misconceptions about the disease and lack of knowledge about susceptibility of cervical cancer was a frequently expressed barrier. For example, several studies reported that women assumed that they were not at risk of having cervical cancer if they had no symptoms: “I still feel that if there’s no symptoms you don’t need to worry particularly” (Waller et al., Citation2012, p. 29). Another recurrent misconception among women related to susceptibility of cancer was the belief that transitory sexual meant that one was not at risk of getting cervical cancer:” I’ve always related it to being sexually active, so if you’re not then you’re not at risk whatsoever” (Waller et al., Citation2012, p. 29) or that the disease is genetic: “Well, it’s quite stupid really because it is important to check. But then I think that there’s no one in my family that has ever had any problems there. Not one, neither my mother nor grandmother nor great-grandmother or my sister. So there’s no worries” (Oscarsson et al., Citation2008, p. 28). Insufficient knowledge about cervical cancer was also evident with regards to its potential of being treated: “You have feeling that if it’s cancer it’s not treatable” (Marlow et al., Citation2019, p. 6), and knowing that the disease is treatable was a reported facilitator to screening attendance: “Cancer was a scary word before the meetings but now I see it as another illness which can be cured” (Box, Citation1998, p. 7).

Theme: Lack of awareness/knowledge of CCS (20 studies)

Knowledge about CCS constituted a barrier to attendance if absent, and a facilitator if present. Lack of knowledge that CCS is beneficiary for health was the most frequently identified barrier within this theme. Scepticism about the health benefits from attending screening was raised by women on several occasions, for example: “There are different opinions about the benefits of this testing (as with mammograms) for others than risk groups.” (Blomberg et al., Citation2008, p. 564). General information about CCS was another reported barrier and facilitator to screening attendance and a quantitative study found a significant association between CCS attendance and awareness of the national PCCSP: “Screening attendance was associated with having ever heard of cervical cancer screening (5.90, 3.76–9.27), as compared to not having heard of it” (Andreassen et al., Citation2018, p. 612). Awareness about the purpose of CCS (including recommended frequency) was a reported barrier to CCS attendance and some women requested more education as this would eventually facilitate attendance. Knowledge about the procedure constituted a facilitator to screening and in a number of studies women expressed a request to learn more explicitly what it involves: “I want to be told what is going on and to be shown the instruments they will be using" (Box, Citation1998, p. 9). Lack of awareness of eligibility to participate in the PCCSP constituted another barrier to screening, for example erroneous beliefs that one is too old to participate: “I don’t need to go any more… I’m too old now" (woman between 40 and 60 years old)” (Box, Citation1998, p. 7).

Environmental context and resources (28 studies)

Theme: Time (competing demands) (20 studies)

Time constraints were a common barrier and were significantly associated with reduced probability to attend CCS: “Women without time constraints (2.20, 1.47–3.30, as compared to women with time constraints) had higher odds of having attended screening” (Andreassen et al., Citation2018, p. 612). The most frequent barrier related to personal time constraints was unspecified time constraints, which represents a general lack of time or simply being busy:” I was really busy, more than I ought to be, recently, so it’s very easy to blame it on not being able to find the time” (Oscarsson et al., Citation2008, p. 30). Other women attributed their time constraints to family commitments (e.g. childcare) and/or work commitments: “I didn’t get round to go to the doctors … I’m busy cos I’m working full-time, single parent, lots to do” (Marlow, et al., Citation2015, p. 252).

Theme: Time (service issues) (16 studies)

Time related service issues were another frequently expressed theme in the data, where inconvenience to make an appointment was the most frequently identified barrier among the included studies. Thinking that making an appointment is easy was significantly associated with CCS attendance in one study: “Attendees think of making an appointment for screening with the GP by phone as significantly easier than non-attendees (t=−3.50) […]”. (Knops-Dullens et al., Citation2007, p. 441). Unsuitable appointment times and scheduling issues have been identified as a barrier to CCS attendance in several studies: “19% said that unsuitable appointment times would prevent them from attending CS. Of women who made this statement, 27% attended for a smear compared with 40% of those who disagreed (w2 1⁄4 14.53; df 1⁄4 1; P 1⁄4 0.000)” (Walsh, Citation2006, p. 295). Convenient clinic opening hours were repeatedly reported as a facilitator if present and a barrier if absent: “Women pointed out different reasons why they could not participate in screening […]. Other reasons were […] unsuitable reception times (11.8%)”. (Kivistik et al., 2011, p. 3).

Theme: Accessibility (11 studies)

Women identified accessibility to the clinic as both a barrier and facilitator to CCS. Ease to participate in CCS was an important facilitator to screening according to some women: “The most commonly proposed reasons for the women to participate in the screening were […] easy to participate when invited (49%)” (Idestrom et al., Citation2002, p. 964). Some women reported that distance to the screening clinic was a factor that could impede CCS attendance: “The most frequent barriers for non-attendance among never-attenders was […] and ‘Distance to the doctor (11%)” (Andreassen et al., Citation2018, p. 612).

Beliefs about Consequences (26 studies)

Theme: Future effects of (not) attending CCS (21 studies)

Anticipated future outcomes of CCS were a common theme that influenced women’s inclination to attend CCS. The most recurrent theme was receiving results from the screening, which could hamper women’s willingness to attend CCS as they might fear a cancer-positive result: “If they find something wrong, I am afraid it might be cancer (46%)” (Shah et al., Citation2006, p. 50). On the other hand, for some women, learning the results from a smear test constituted a facilitator to CCS attendance: “The most commonly proposed reasons for the women to participate in the screening were to be ensured that they were healthy (67%)” (Idestrom et al., Citation2002, p. 964). Physical consequences that could occur as a result of the procedure was a repeated barrier to screening and some women expressed concerns that it could cause direct or indirect long term health consequences, for example: “[…] In some cases, these tests can cause detrimental changes instead. The worry, which can also elicit sickness, and which the body is exposed to during the wait for the test results, has also been discussed, from what I have heard and read […] ”(Blomberg et al., Citation2008, p. 564). However, some women considered CCS attendance to facilitate the prevention of physical conditions: “1st woman: ‘If women don’t go for this test, they will feel uneasy, and they may have pain, because of that …and stomach pain’ (Chiu et al., Citation1999, p. 15).

Theme: Immediate effects of (not) attending screening (17 studies)

Many studies reported that women’s concerns relating to beliefs about potential short-term effects or outcomes of screening were barriers to attendance. Anticipating that screening will be painful or unpleasant was the foremost barrier to attendance reported by women in several studies. Women often based their beliefs that screening causes pain or discomfort on their own or others’ experiences: “The pain was really bad and we had to stop it. I suppose from that onset of having the bad experience I haven’t liked it." (Marlow et al., Citation2019, p. 6) and “You hear the stories of other women who go through them and they’re uncomfortable, and they’re painful … it didn’t seem like a great idea to go and have one” (Marlow et al., Citation2018, p. 2490). Although many women reported that pain or discomfort was a barrier, some explained that this would not inhibit them from attending CCS: “No, I think it is unpleasant. I think it is very unpleasant, but then again… you know that soon it is done” (Azerkan et al., Citation2015, p. 14).

Discussion

This systematic review set out to identify and synthesise the peer-reviewed, published literature reporting perceived barriers and facilitators associated with attendance for CCS in EU member states with organised PCCSP. This was achieved by extracting reported barriers/facilitators and systematically categorising them to the TDF domains. Thematic analysis within each TDF domain enabled the identification of key global themes and sub-themes.

Implications for practice

The findings of this review have implications for the systematic development of behaviour change interventions targeting attendance for CCS in EU member states with organised PCCSP. The TDF can be applied as a component of the Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW) framework for intervention development (Michie et al., Citation2011). The framework follows several steps including problem formulation and specification of target behaviour(s), behavioural analysis and diagnosis (i.e. data driven exploration of the key influences on a target behaviour), identification of intervention options as well as policy and implementation options. The present review provides a behavioural diagnosis of the target behaviour. Future endeavours to target CCS uptake will benefit from adhering to the remaining steps of the BCW to systematically identify congruent Intervention Types and Behaviour Change Techniques (BCTs) that may be effective in increasing CCS uptake and make context informed decisions (i.e. with consideration of the local population and available resources) on which to include.

In the analysis, five TDF domains were most frequently identified as factors influencing screening attendance: Emotion, Social Influences, Knowledge, Environmental Context and Resources and Beliefs about Consequences. Consequently, interventions targeting these domains may be more effective in increasing CCS attendance compared to domains that were less frequently identified (i.e. Social Professional Role and Identity, Beliefs about Capabilities and Reinforcement). Although all findings should be considered as part of a systematic intervention development process and with consideration of the given context and target population, below we propose key recommendations based on the most frequently identified barriers and facilitators in this review: (1) Increase sense of comfort, support and emotional safety; (2) Increase awareness of the importance of CCS (3) Reduce inconvenience to improve ease of attending screening.

Increase sense of comfort, support and safety

Many of the barriers identified were related to the perceived psychological and physical discomfort that CCS is considered to entail. Almost all of the included studies reported that negative emotions such as fear and embarrassment were important barriers to screening. Although there were limited reports of potential facilitators to overcome barriers within the Emotion domain specifically, there were many reports on how the interaction with and treatment by the HCP could be improved in order to increase a sense of comfort, support and safety and thereby facilitate CCS attendance. For example, having a female test taker, being treated with patience, understanding, empathy and encouragement, being informed about the procedure and the instruments used and having established continuity with the HCP were reported facilitators that are judged to support feelings of comfort, support and safety. Consequently, although previous independent research studies have highlighted psychological and physical discomfort and negative emotions as barriers to CCS attendance (Holroyd et al., Citation2004; Waller et al., Citation2009; Wilding et al., Citation2020; Walsh, Citation2006), the present study reveals how these may be addressed by implementing a range of intervention components. Furthermore, for minority populations there was some evidence of the potential benefit of developing culturally sensitive interventions that promote social/cultural compatibility between the test taker and the CCS attendee (in terms of, e.g., shared language and nationality).

Increase awareness of the importance of CCS

Lacking awareness and understanding of CCS and cervical cancer were prominent barriers that were reported in more than three quarters of the included studies. Not being informed about the purpose, importance and health benefits of CCS were frequently reported barriers in the included studies. Reported potential facilitators were education about the purpose of screening and associated health benefits, as well as disseminating explanatory information about the PCCSP. With regards to cervical cancer, many women lacked knowledge about susceptibility of HPV/cervical cancer, development of the disease and potential treatments. Using various channels to disseminate relevant information about CCS and cervical cancer may be an important intervention component to promote awareness and consequently screening uptake.

Reduce inconvenience to improve ease of attending screening

Many of the identified barriers related to perceived inconvenience to attend CCS, which has been highlighted in previous research studies (Bennett et al., Citation2018; Waller et al., Citation2009). The present review covers a collection of prominent barriers that are reported to hamper screening attendance, including but not limited to: competing time demands, scheduling issues, clinic opening hours and distance to screening clinic. Although not as frequently identified, reported facilitators highlighted the importance of improving accessibility and convenience to participate in screening. Providing childcare facilities at screening clinics as well as offering more flexible appointment and opening times, and locations, for the screening may be advantageous to increase CCS uptake. Intervention strategies that aim to address inconvenience will likely benefit from a close collaboration between those looking to promote screening uptake and those responsible for providing and delivering screening.

Strengths, limitations and challenges

This review provides a comprehensive account of potential barriers and facilitators that could be targeted to increase CCS attendance in EU member states. Each stage of the review was led by G.S. with reliability checks from D.D.L. at every stage of the process (i.e. search strategy development, screening, data extraction, quality assessment and analysis). The framework informed approach guided the identification of barriers and facilitators linked to pre-established theoretical domains while the inductive coding enabled a more detailed data-driven understanding of the specific factors that were nested within each domain. The combination of these two approaches is therefore considered a strength of this study.

One limitation of this study is that research from several EU member states was not identified, whereas a majority of the included studies were performed in the United Kingdom. This may skew the results in favour of particular populations. The review also did not include grey literature and countries not part of the EU. A further limitation is that the review relies on the ways in which data has been presented in the primary studies that are included. This could have implications for the domains most frequently identified. Furthermore, although the TDF allowed for systematic and theory informed identification of barriers and facilitators, the mapping of data to the domains was occasionally challenging due to a lack of explicit contextual detail within the extracted data. This challenge can not be attributed to the use of a framework approach alone, but is rather a specific issue for coding secondary data as part of a systematic review.

Limitations of the TDF

One difficulty with the application of the TDF was the apparent overlap between different domains. One example is “thinking that screening is unnecessary”, which is a barrier that equally could be mapped to two (or more domains) – in this case the Knowledge domain and the Optimism domain. Eventually, this theme was coded to Knowledge based on careful deliberation, although this decision still involved some subjective interpretation. Previous studies have also reported challenges with determining which domains data would be most appropriately assigned to (Craig et al., Citation2016; Connell et al., Citation2016). Future versions of the TDF should provide more explicit descriptions and definitions of the respective domains and make more precise distinctions between them in order to guide researchers on how to best select one domain over another.

Recommendations for future research

There is a need for research in additional EU member states than those frequently identified in this study. Furthermore, future reviews should include unpublished literature and consider all countries with organised PCCSP. Future research will benefit from using integrative theoretical frameworks (i.e. TDF or similar) when collecting data on the influences on CCS attendance in different populations and contexts. This will improve the likelihood of gaining a broader understanding of perceived barriers and facilitators as opposed to focusing on a limited number, which may have been biased by previous research. Additionally, future research should investigate the relative importance of specific domains within distinct sub-groups and explore which of the barriers and facilitators identified in this review are most feasible to address in future interventions in different real world contexts. Half of the included studies in this review targeted minority populations and it is likely that certain barriers and facilitators are of higher relevance for these sub-groups of women.

Conclusion

Five theoretical domains were identified as prominent influences on cervical cancer screening attendance in EU member states with organised PCCSP. Examples of barriers covered in these domains include physical and psychological discomfort, lack of awareness about CCS and cervical cancer and perceived inconvenience of attending screening. Education and information about PCCSP, CCS and cervical cancer, improved interaction between HCPs and patients, and improved accessibility of screening acted as facilitators. Further research is needed to identify the relative importance of different influences for different sub-populations and to identify the influences that are most appropriate and feasible to address in future interventions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this work.

Data availability statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Notes

1 World Health Organisation: ”Cervical cancer screening: Response by country” 2018-03-13. Accessed on the 15th of August 2019. http://apps.who.int/gho/data/view.main.UHCCERVICALCANCERv

References

- Abdullahi, A., & Copping, J., & Kessel, A., & Luck, M., & Bonell, C. (2009). Cervical screening: Perceptions and barriers to uptake among Somali women in Camden. Public Health, 123(10), 680–685. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2009.09.011

- Andreassen, T., Melnic, A., Figueiredo, R., Moen, K., Şuteu, O., Nicula, F., Ursin, G., & Weiderpass, E. (2018). Attendance to cervical cancer screening among Roma and non-Roma women living in North-Western region of Romania. International Journal of Public Health, 63(5), 609–619. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-018-1107-5

- Arbyn, E., Anttila, A., Jordan, J., Ronco, G., Schenck, U., Segnan, N., Wiener, H., Herbert, A., Daniel, J., & von Karsa, L. (2008). European guidelines for quality assurance in cervical cancer screening. 2nd ed. Directorate-General for Health and Food Safety. http://screening.iarc.fr/doc/ND7007117ENC_002.pdf

- Arden, M., Drabble, S., O’cathain, A., Hutchings, M., & Wildman, M. (2019). Adherence to medication in adults with Cystic Fibrosis: An investigation using objective adherence data and the Theoretical Domains Framework. British Journal of Health Psychology, 24 (2), 357–380. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12357

- Atkins, L., Francis, J., Islam, R., O’Connor, D., Patey, A., Ivers, N., Foy, R., Duncan, E., Colquhoun, H., Grimshaw, J., Lawton, R., & Michie, S. (2017). A guide to using the Theoretical Domains Framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Implementation Science,12: (1), 1–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0605-9

- Azerkan, F., Widmark, C., Sparen, P., Weiderpass, E., Tillgren, P., & Faxelid, E. (2015). When life got in the way: How Danish and Norwegian immigrant women in Sweden reason about cervical screening and why they postpone attendance. PLoS ONE, 10(7), e0107624. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0107624

- Bennett, K. F., Waller, J., Chorley, A. J., Ferrer, R. A., Haddrell, J. B., & Marlow, L. A. (2018). Barriers to cervical screening and interest in self-sampling among women who actively decline screening. Journal of Medical Screening, 25(4), 211–217. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0969141318767471

- Blomberg, K., Tishelman, C., Ternestedt, B. M., & Tornberg, S. (2008). How do women who choose not to participate in population-based cervical cancer screening reason about their decision?Psycho-Oncology, 17(6), 561–569. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1270

- Bosgraaf, R. P., Ketelaars, P. J. W., Verhoef, V. M. J., Massuger, L. F. A. G., Meijer, W. C. J. L. M., Melchers, J. G., & Bekkers, R. L. M. (2014). Reasons for non-attendance to cervical screening and preferences for HPV self-sampling in Dutch women. Preventive Medicine, 64, 108–113. Volume https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.04.011

- Box, V. (1998). Cervical screening: the knowledge and opinions of black and minority ethnic women and of health advocates in East London. Health Education Journal, 57(1), 3–15. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/001789699805700102

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Bruni, L., Albero, G., Serrano, B., Mena, M., Gómez, D., Muñoz, J., Bosch, F. X., & de Sanjosé, S., ICO/IARC Information Centre on HPV and Cancer (HPV Information Centre). (2019). Human Papillomavirus and Related Diseases in Europe. Summary Report 17 June 2019. https://hpvcentre.net/statistics/reports/XEX.pdf

- Cadman, L., Waller, J., Ashdown-Barr, L., & Szarewski, A. (2012). Barriers to cervical screening in women who have experienced sexual abuse: An exploratory study. Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care, 38(4), 214–220. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/jfprhc-2012-100378

- Cane, J., O’Connor, D., & Michie, S. (2012). Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implementation Science, 7(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-7-37

- Chiu, L., Heywood, P., Jordan, J., McKinney, P., & Dowell, T. (1999). Balancing the equation: The significance of professional and lay perceptions in the promotion of cervical screening amongst minority ethnic women. Critical Public Health, 9(1), 5–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09581599908409216

- Crăciun, I. C., Todorova, I., & Băban, A. (2020). Taking responsibility for my health”: Health system barriers and women’s attitudes toward cervical cancer screening in Romania and Bulgaria. Journal of Health Psychology, 25(13-14), 2151–2163. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105318787616

- Craig, L. E., McInnes, E., Taylor, N., Grimley, R., Cadilhac, D. A., Considine, J., & Middleton, S. (2016). Identifying the barriers and enablers for a triage, treatment, and transfer clinical intervention to manage acute stroke patients in the emergency department: a systematic review using the theoretical domains framework (TDF). Implementation Science, 11(1), 157. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0524-1

- Connell, L., McMahon, N., Tyson, S., Watkins, C., & Eng, J. (2016). Mechanisms of action of an implementation intervention in stroke rehabilitation: A qualitative interview study. BMC Health Services Research, 16(1), 534. Article number: 2016). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1793-8

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). (2018). CASP Qualitative Checklist. [online] Available at: https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018.pdf.

- Ekechi, C., Olaitan, A., Ellis, R., Koris, J., Amajuoyi, A., & Marlow, L. A. (2014). Knowledge of cervical cancer and attendance at cervical cancer screening: a survey of Black women in London. BMC Public Health, 14(1), 1096. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-1096

- European Commission. (2003). Council Recommendation of 2 December 2003 on cancer screening (2003/878/EC). Official Journal of the European Union,

- European Network of Cancer Registries (ENCR). (2016). Cervical Cancer (CCU) Factsheet. https://www.encr.eu/sites/default/files/factsheets/ENCR%20Factsheet%20Cervical%20Cancer%20March%202016.pdf

- Gale, N. K., Heath, G., Cameron, E., Rashid, S., & Redwood, S. (2013). Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(1), 117. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-117

- Graham-Rowe, E., Lorencatto, F., Lawrenson, J. G., Burr, J. M., Grimshaw, J. M., Ivers, N. M., Presseau, J., Vale, L., Peto, T., Bunce, C., & J Francis, J. and (2018). WIDeR-EyeS Project team. (2018). Systematic review or Meta-analysis Barriers to and enablers of diabetic retinopathy screening attendance: A systematic review of published and grey literature. Diabetic Medicine, 35(10), 1308–1319. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.13686

- Holroyd, E., Twinn, S., & Adab, P. (2004). Socio‐cultural influences on Chinese women’s attendance for cervical screening. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 46(1), 42–52. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2003.02964.x

- Hong, Q. N., & Fàbregues, S., & Bartlett, G., & Boardman, F., & Cargo, M., & Dagenais, P., & Gagnon, M.-P., & Griffiths, F., & Nicolau, B., & O’Cathain, A., & Rousseau, M.-C., & Vedel, I., & Pluye, P. (2018). The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Education for Information, 34(4), 285–287. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3233/EFI-180221

- Idestrom, M., Milsom, I., & Andersson-Ellstrom, A. (2002). Knowledge and attitudes about the Pap-smear screening program: A population-based study of women aged 20-59 years. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand, 81(10), 962–967.

- Jackowska, M., Wagner, C., Wardle, J., Juszczyk, D., Luszczynska, A., & Waller, J. (2012). Cervical screening among migrant women: a qualitative study of Polish, Slovak and Romanian women in London, UK. Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care, 38 (4), 229–238. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/jfprhc-2011-100144

- Knops-Dullens, T., De Vries, N., & De Vries, H. (2007). Reasons for non-attendance in cervical cancer screening programmes: An application of the Integrated Model for Behavioural Change. European Journal of Cancer Prevention, 16(5), 436–445. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/01.cej.0000236250.71113.7c

- Marlow, L., McBride, E., Varnes, L., & Waller, J. (2019). Barriers to cervical screening among older women from hard-to-reach groups: A qualitative study in England 11 Medical and Health Sciences 1117 Public Health and Health Services. BMC Women’s Health, 19(38), 1–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-019-0736-z.

- Marlow, L. A. V., Chorley, A. J., Rockliffe, L., & Waller, J. (2018). Decision-making about cervical screening in a heterogeneous sample of nonparticipants: A qualitative interview study. Psycho-Oncology, 27(10), 2488–2493. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4857

- Marlow, L. A. V., Wardle, J., & Waller, J. (2015). Barriers to cervical cancer screening among ethnic minority women: A qualitative study. Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care, 41(4), 248–254. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/jfprhc-2014-101082

- Marlow, L. A. V., Wardle, J., & Waller, J. (2015). Understanding cervical screening non-attendance among ethnic minority women in England. British Journal of Cancer, 113(5), 833–839. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2015.248

- Michie, S., van Stralen, M. M., & West, R. (2011). The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation Science, 6(1), 42. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-6-42

- Michie, S., Johnston, M., Abraham, C., Lawton, R., Parker, D., & Walker, A, on behalf of the ‘Psychological Theory’ Group. (2005). Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: a consensus approach. Quality and Safety in Health Care , 2005(14), 26–33. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2004.011155

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & Group, P. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 151(4), 264–269. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- Naish, J. B., & Denton, B. (1994). Intercultural consultations: Investigation of factors that deter non-English speaking women from attending their general practitioners for cervical screening. British Medical Journal, 309(6962).

- Nathan, N., Elton, B., Babic, M., McCarthy, N., Sutherland, R., Presseau, J., Seward, K., Hodder, R., Booth, D., Yoong, S., & Wolfenden, L. (2018). Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of physical activity policies in schools: A systematic review. Preventive Medicine, 107, 45–53. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.11.012.

- Neilson, A., R. K., & Jones, R. K. (1998). Women’s lay knowledge of cervical cancer/cervical screening: accounting for non-attendance at cervical screening clinics. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 28(3), 571–575. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.1998.00728.x

- OECD/European Union. (2018). Screening, survival and mortality for cervical cancer, in Health at a Glance: Europe 2018: State of Health in the EU Cycle. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1787/health_glance_eur-2018-41-en

- Ogbonna, F. (2017). Knowledge, attitude, and experience of cervical cancer and screening among Sub-saharan African female students in a UK University. Annals of African Medicine, 16(1). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4103/aam.aam_37_16

- Oscarsson, M. G., Wijma, B. E., Benzein, E. G. (2008). I do not need to… I do not want to… I do not give it priority…’ - Why women choose not to attend cervical cancer screening. Health Expectations, 11(1), 26–34. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1369-7625.2007.00478.x

- Paksaite, P., Watson, M., Crosskey, J., Sula, E., & West, C. (2021). A systematic review using the Theoretical Domains Framework to identify barriers and facilitators to the adoption of prescribing guidelines. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/ijpp.12654

- Ponti, A., Anttila, A., & Ronco, G. (2017). Cancer Screening in the European Union. Report on the implementation of Council Recommendation on Cancer Screening. European Commission.

- Prajapati, A. R., Dima, A. L., & Clark, A. B. (2019). Mapping of modifiable barriers and facilitators of medication adherence in bipolar disorder to the Theoretical Domains Framework: a systematic review protocol. BMJ Open, 2019(9), e026980. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026980

- Presseau, J., Schwalm, J. D., Grimshaw, J. M., Witteman, H. O., Natarajan, M. K., Linklater, S., Sullivan, K., & Ivers, N. M. (2017). Identifying determinants of medication adherence following myocardial infarction using the Theoretical Domains Framework and the Health Action Process Approach. Psychology & Health, 32(10), 1176–1194. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2016.1260724

- Salad, J., Verdonk, P., De Boer, F., & Abma, T. A. (2015). A Somali girl is Muslim and does not have premarital sex. Is vaccination really necessary? A qualitative study into the perceptions of Somali women in the Netherlands about the prevention of cervical cancer. International Journal for Equity in Health, 14(1). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-015-0198-3

- Screening & Immunisations Team, NHS Digital. (2018). Cervical Screening Programme England, 2017-18. https://files.digital.nhs.uk/B1/66FF72/nhs-cerv-scre-prog-eng-2017-18-report.pdf

- Shah, S., Montgomery, H., Smith, C., Madge, S., Walker, P., Evans, H., Johnson, M., & Sabin, C. (2006). Cervical screening in HIV-positive women: Characteristics of those who default and attitudes towards screening. HIV Medicine, 7(1), 46–52. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-1293.2005.00331.x

- Shaw, R. L., Holland, C., Pattison, H. M., & Cooke, R. (2016). Patients’ perceptions and experiences of cardiovascular disease and diabetes prevention programmes: a systematic review and framework synthesis using the Theoretical Domains Framework. Social Science & Medicine, 156, 192–203. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.03.015

- Waller, J., Bartoszek, M., Marlow, L., & Wardle, J. (2009). Barriers to cervical cancer screening attendance in England: a population-based survey. Journal of Medical Screening, 16(4), 199–204. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1258/jms.2009.009073

- Waller, J., Jackowska, M., Marlow, L., & Wardle, J. (2012). Exploring age differences in reasons for nonattendance for cervical screening: A qualitative study. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 119(1). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03030.x.

- Walsh, J. C. (2006). The impact of knowledge, perceived barriers and perceptions of risk on attendance for a routine cervical smear. European Journal of Contraception and Reproductive Health Care, 11(4), 291–296. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13625180600841827.

- Wilding, S., Wighton, S., Halligan, D., West, R., Conner, M., & B. O’Connor, D. (2020). What factors are most influential in increasing cervical cancer screening attendance? An online study of UK-based women. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine, 8(1), 314–328. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/21642850.2020.1798239

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2019). Human papillomavirus (HPV) and cervical cancer.https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/human-papillomavirus-(hpv)-and-cervical-cancer

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2020). Cervical Cancer. https://www.who.int/health-topics/cervical-cancer#tab=tab_1

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2018). Cervical cancer screening: Response by country. WHO. http://apps.who.int/gho/data/view.main.UHCCERVICALCANCERv

Appendix 1.

World Health Organization (2017) – Data on the existence of National Cervical Screening Programmes in EU member states.

Appendix 2.

Reference papers used to develop search strategy

1. Abdullahi, A., Copping, J., Kessel, Anthony., Luck, M. & Bonell, Chris. (2009). Cervical screening: Perceptions and barriers to uptake among Somali women in Camden. Public health. 123. 680-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2009.09.011.

2. Augusto, E.F., Rosa, M.L.G., Cavalcanti, S.M.B. et al. (2013). ”Barriers to cervical cancer screening in women attending the Family Medical Program in Niterói, Rio de Janeiro.” Arch Gynecol Obstet 287: 53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-012-2511-3

3. Kwok, C., White, K. & Roydhouse, J.K. J. (2011) “Chinese-Australian women’s knowledge, facilitators and barriers related to cervical cancer screening: a qualitative study.” Immigrant Minority Health 13: 1076. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-011-9491-4

4. Ryan, M., Marlow, L., Waller, J. (2019). “Socio-demographic correlates of cervical cancer: risk factor knowledge among screening non-participants in Great Britain”. Preventive Medicine, Volume 125, 2019, Pages 1-4, ISSN 0091-7435, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.04.026

5. Marlow, L., McBride, E., Varnes, L., Waller, J. (2019) “Barriers to cervical screening among older women from hard-to-reach groups: a qualitative study in England”. BMC Women’s Health. Volume 19, Article number: 38 (2019).

6. Marlow LAV, Waller J, Wardle J. “Barriers to cervical cancer screening among ethnic minority women: a qualitative study”. Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care; 41:248-254.

7. Waller, J., Bartoszek, M., Marlow, L., & Wardle, J. (2009). “Barriers to cervical cancer screening attendance in England: a population-based survey”. Journal of Medical Screening, 16(4), 199–204. https://doi.org/10.1258/jms.2009.009073

8. Walsh, Jane C. (2006) “The impact of knowledge, perceived barriers and perceptions of risk on attendance for a routine cervical smear”. The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care, 11:4, 291-296, DOI: 10.1080/13625180600841827

9. Holroyd, E., Twinn, S. and Adab, P. (2004). “Socio‐cultural influences on Chinese women’s attendance for cervical screening”. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 46: 42-52. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2003.02964.x

Appendix 3.

Search strategy used in Ovid the 24th of May 2019

(Cervical Cancer.ti,ab or Cervical.ti,ab. or Cervix.ti,ab. AND (Cervical smear$.ti,ab. or Cervical test$.ti,ab. or Cervical screen$.ti,ab. or Smear test$.ti,ab. or Pap tes$.ti,ab. or Pap smear$.ti,ab. or Papanicolaou smear$.ti,ab. or Papanicolaou test$.ti,ab. or Cervical cytolog$.ti,ab. or Cervical screening program$.ti,ab. or Cervical cancer screening$.ti,ab. or screening$.ti,ab. or test$.ti,ab.) AND (non-attend$.ti,ab. or non attend$.ti,ab. or attend$.ti,ab. or attending$.ti,ab. or attendance.ti,ab. or participati$.ti,ab.) AND (Barrier$.ti,ab. or Obstacle$.ti,ab. or Facilitator$.ti,ab. or Enabler$.ti,ab. or Determin$.ti,ab. or Influenc$.ti,ab. or Motivat$.ti,ab. or Factor$.ti,ab. or Barriers.ti,ab. or Facilitators.ti,ab.))

Appendix 4.

Coding manual with definitions for each of the 14 domains in the TDF

Appendix 5

Domain: Social professional role and identity (8 studies)

Complete reference list of studies included in the analysis

Abdullahi, A & Copping, J & Kessel, Anthony & Luck, M & Bonell, Chris. (2009). Cervical screening: Perceptions and barriers to uptake among Somali women in Camden. Public health. 123. 680-5. 10.1016/j.puhe.2009.09.011.

Akhagba, O. M.(2017). Migrant women’s knowledge and perceived sociocultural barriers to cervical cancer screening programme: A qualitative study of African women in Poland. Health Psychology Report, 3(3), 263–271. ISSN 2353-4184. https://doi.org/10.5114/hpr.2017.65238

Andreassen, T., Melnic, A., Figueiredo, R., Moen, K., Şuteu, O., Nicula, F., Ursin, G., & Weiderpass, E. (2018). Attendance to cervical cancer screening among Roma and non-Roma women living in North-Western region of Romania. International journal of public health, 63(5), 609–619.

Azerkan, F., Widmark, C., Sparen, P., Weiderpass, E., Tillgren, P., and Faxelid, E. (2015). When life got in the way: How danish and norwegian immigrant women in Sweden reason about cervical screening and why they postpone attendance. PLoS ONE 10(7), 1-22. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0107624

Bennett, K. F., Waller, J., Chorley, A. J., Ferrer, R. A., Haddrell, J. B., & Marlow, L. A. (2018). Barriers to cervical screening and interest in self-sampling among women who actively decline screening. Journal of medical screening, 25(4), 211–217. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969141318767471

Blomberg, K., Tishelman, C., Ternestedt, B.M., Tornberg, S. (2008) How do women who choose not to participate in population-based cervical cancer screening reason about their decision? Psycho-Oncology, 2008, 17: 561-569.

Blomberg, K., Tishelman, C., Ternestedt, B.-M., Törnberg, S., Levál, A., & Widmark, C.(2011). How can young women be encouraged to attend cervical cancer screening? Suggestions from face-to-face and internet focus group discussions with 30-year-old women in Stockholm, Sweden. Acta Oncologica, 50(1), 112–120. 2011 Jan https://doi.org/10.3109/0284186X.2010.528790

Bosgraaf, R. P., Ketelaars, P. J., Verhoef, V. M., Massuger, L. F., Meijer, C. J., Melchers, W. J., & Bekkers, R. L. (2014). Reasons for non-attendance to cervical screening and preferences for HPV self-sampling in Dutch women. Preventive medicine, 64, 108–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.04.011

Box, V. (1998) Cervical screening: the knowledge and opinions of black and minority ethnic women and of health advocates in East London. Health Education Journal, 57(1), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/001789699805700102

Cadman, L., Waller, J., Ashdown-Barr, L., & Szarewski, A.(2015). Attitudes towards cytology and human papillomavirus self-sample collection for cervical screening among Hindu women in London, UK: A mixed methods study. Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care, 41(1), 38–47. https://doi.org/10.1136/jfprhc-2013-100705

Cadman, L., Waller, J., Ashdown-Barr, L., and Szarewski, A. (2012). Barriers to cervical screening in women who have experienced sexual abuse: An exploratory study. Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care. 38(4), 214-220 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jfprhc-2012-100378

Chiu, L., Heywood, P., Jordan, J., McKinney, P. & Tony Dowell. (1999). Balancing the equation: The significance of professional and lay perceptions in the promotion of cervical screening amongst minority ethnic women. Critical Public Health, 9:1, 5-22, DOI: 10.1080/09581599908409216

Craciun, I. C., Todorova, I., & Băban, A. (2020). Taking responsibility for my health”: Health system barriers and women’s attitudes toward cervical cancer screening in Romania and Bulgaria. Journal of Health Psychology, 25(13-14), 2151–2163. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105318787616

Ekechi, C., Olaitan, A., Ellis, R., Koris, J., Amajuoyi, A., and Marlow, L. A. (2014) Knowledge of cervical cancer and attendance at cervical cancer screening: a survey of Black women in London. BMC Public Health. 14(1096), 1-9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1096.

Idestrom, M., Milsom, I., and Andersson-Ellstrom, A., (2002). Knowledge and attitudes about the Pap-smear screening program: A population-based study of women aged 20-59 years. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2002 Oct;81(10):962-7.

Jackowska, M; von Wagner, C; Wardle, J; Juszczyk, D; Luszczynska, A; Waller, J; (2012). Cervical screening among migrant women: a qualitative study of Polish, Slovak and Romanian women in London, UK. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care, 38 (4) pp. 229-238. 10.1136/jfprhc-2011-100144.

Kivistik, Alice & Lang, Katrin & Baili, Paolo & Anttila, Ahti & Veerus, Piret. (2011). Women’s knowledge about cervical cancer risk factors, screening, and reasons for non-participation in cervical cancer screening programme in Estonia. BMC women’s health. 11(43), 1-6. 10.1186/1472-6874-11-43.

Knops-Dullens, T., de Vries, N., & de Vries, H. (2007). Reasons for non-attendance in cervical cancer screening programmes: an application of the Integrated Model for Behavioural Change. European journal of cancer prevention: the official journal of the European Cancer Prevention Organisation (ECP), 16(5), 436–445. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.cej.0000236250.71113.7c

Larsen, L. P., & Olesen, F.(1998). Women’s knowledge of and attitude towards organized cervical smear screening. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 77(10), 988–996. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0412.1998.771008.x

Marlow, L., McBride, E., Varnes, L., & Waller, J. (2019). Barriers to cervical screening among older women from hard-to-reach groups: a qualitative study in England. BMC women’s health, 19(1), 1-10.

Marlow, L., Chorley, A. J., Rockliffe, L., & Waller, J. (2018). Decision-making about cervical screening in a heterogeneous sample of nonparticipants: A qualitative interview study. Psycho-oncology, 27(10), 2488–2493. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4857

Marlow, L. A., Waller, J., & Wardle, J. (2015). Barriers to cervical cancer screening among ethnic minority women: a qualitative study. The journal of family planning and reproductive health care, 41(4), 248–254. https://doi.org/10.1136/jfprhc-2014-101082

Marlow, L. A., Wardle, J., & Waller, J. (2015). Understanding cervical screening non-attendance among ethnic minority women in England. British journal of cancer, 113(5), 833–839. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2015.248

McKie, L.(1993). Women’s views of the cervical smear test: implications for nursing practice–women who have not had a smear test. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 18(6), 972–979. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.1993.18060972.x

Naish, J., Brown, J., & Denton, B. (1994). Intercultural consultations: investigation of factors that deter non-English speaking women from attending their general practitioners for cervical screening. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 309(6962), 1126–1128.

Neilson, A., & Jones, R. K. (1998). Women’s lay knowledge of cervical cancer/cervical screening: accounting for non-attendance at cervical screening clinics. Journal of advanced nursing, 28(3), 571–575. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.1998.00728.x

Ogbonna F. S. (2017). Knowledge, attitude, and experience of cervical cancer and screening among Sub-saharan African female students in a UK University. Annals of African medicine, 16(1), 18–23. https://doi.org/10.4103/aam.aam_37_16

Ostensson, E., Alder, S., Elfstrom, K. M., Sundstrom, K., Zethraeus, N., Arbyn, M., & Andersson, S.(2015). Barriers to and facilitators of compliance with clinic-based cervical cancer screening: Population-based cohort study of women aged 23-60 years. PLoS One, 10(5), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0128270

Oscarsson, M. G., Wijma, B. E., & Benzein, E. G. (2008). ‘I do not need to… I do not want to… I do not give it priority…’–why women choose not to attend cervical cancer screening. Health expectations: an international journal of public participation in health care and health policy, 11(1), 26–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1369-7625.2007.00478.x

Salad, J., Verdonk, P., De Boer, F., & Abma, T. A. (2015). A Somali girl is Muslim and does not have premarital sex. Is vaccination really necessary? A qualitative study into the perceptions of Somali women in the Netherlands about the prevention of cervical cancer. International Journal for Equity in Health, 14(1), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-015-0198-3.

Sheeran, P., & Orbell, S.(2000). Using implementation intentions to increase attendance for cervical cancer screening. Health Psychology, 19(3), 283–289. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.19.3.283

Shah, S., Montgomery, H., Smith, C., Madge, S., Walker, P., Evans, H., Johnson, M., & Sabin, C. (2006). Cervical screening in HIV-positive women: characteristics of those who default and attitudes towards screening. HIV medicine, 7(1), 46–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-1293.2005.00331.x

Spencer, A. M., Brabin, L., Roberts, S. A., Patnick, J., Elton, P., & Verma, A. (2016). A qualitative study to assess the potential of the human papillomavirus vaccination programme to encourage under-screened mothers to attend for cervical screening. The journal of family planning and reproductive health care, 42(2), 119–126. https://doi.org/10.1136/jfprhc-2015-101283