Abstract

Objective

Research has shown that some young carers face many negative consequences because of their caring experiences, whereas others seem to be unaffected or even report greater well-being. To understand how caring for a family member or close friend can have these different effects, this study compared benefit finding between young carers and their peers and examined its association with mental well-being.

Design

We recruited 2,525 adolescents aged 15–21 years (59.6% female, Mage = 17.73) through the Swiss education system. They were asked to complete measures of caring experiences, benefit finding, and mental well-being. Young carers (n = 1,137), including adolescents who currently or formerly provided care, were compared to adolescents without caring experiences (n = 1,388).

Results

Young carers had a higher level of overall benefit finding than non-carer peers, and their profiles of benefit finding differed regarding the dimensions of growth and empathy. The association between caring experiences and mental well-being was weaker when benefit finding was higher. Benefit finding dimensions were differently associated with mental well-being among young carers.

Conclusions

This study shows that caring is associated with benefit finding and suggests that engaging with past stressors in a positive way may promote resilience in young carers.

Introduction

Caring for a close person with health problems can be demanding for youth and is often associated with the experience of potentially traumatic events (e.g. medical emergency, loss of a significant person) or chronic family stress. Accordingly, children and adolescents who provide care to family members or close friends with an illness, disability, or frailty may experience negative consequences regarding their own health, development, and career opportunities (e.g. Lakman & Chalmers, Citation2019; Robison et al., Citation2020; Stamatopoulos, Citation2018). This makes young carers, as they are internationally referred, an especially vulnerable group of youth (Leu & Becker, Citation2019). However, it has also been recognized that youth’s caring experiences can have both positive and negative outcomes (Joseph et al., Citation2009). Subsequently, a variety of qualitative studies highlighted that despite the challenges of caring, many young carers experience positive consequences of their caring role such as pride, learning new skills, and personal development (e.g. Boyle, Citation2020; McDougall et al., Citation2018; Stamatopoulos, Citation2018). However, little is known about why some young carers do well with their situation and experience positive outcomes, whereas others do not. Hence, further research is needed to determine factors that may moderate the association between caring experiences and outcomes in health and well-being (see Joseph et al., Citation2020).

One factor that promises to help explain individual differences in the outcomes of caring is the degree to which benefits are perceived. After experiencing a stressful or traumatic event, many individuals notice positive transformations with regard to how they see themselves and their lives (Joseph, Citation2011). The subjective experience of positive changes following adversity has been referred to as benefit finding (e.g. Lechner et al., Citation2009). Benefit finding has also been noted as an important characteristic and resource among young carers (Cassidy & Giles, Citation2013; Celdrán et al., Citation2009; Gough & Gulliford, Citation2020; McDougall et al., Citation2018; Pakenham & Bursnall, Citation2006). Experienced benefits in response to caring have been documented across diverse populations of young people, including current and former carers, different age groups, and varying characteristics of the person cared for (e.g. Areguy et al., Citation2019; Kallander et al., Citation2018; Pakenham et al., Citation2007; Shifren et al., Citation2014). Moreover, recent research has suggested that more perceived caring responsibility is associated with a higher level of benefit finding in young carers (Pakenham & Cox, Citation2018).

Caring-related benefit finding has been associated with positive adjustment outcomes among young carers including lower levels of depression, lower levels of psychological distress, higher levels of quality of life, and more adaptive coping strategies (Cassidy et al., Citation2014a; Cassidy & Giles, Citation2013; Joseph et al., Citation2009; Pakenham & Cox, Citation2018). Taken together, a growing body of literature recognizes that caring can relate to benefit finding in youth and that experiencing positive aspects of caring is associated with better well-being.

While the approach to measuring benefit finding as an overall tendency to perceive positive aspects of caring has recently generated important insights into young carers’ resilience, this focus has caused distinct types of benefits to fade into the background. However, benefit finding is a multifactorial concept that denotes many different aspects of positive changes that individuals may identify. Cassidy et al. (Citation2014b) described six dimensions of benefit finding: acceptance (e.g. accepting things, adjusting to things that cannot be changed, and taking things as they come), family bonds (e.g. the family is closer together, being more sensitive to family issues, and appreciating one’s family more), relationships (e.g. being aware of the available support from others, realizing who real friends are, and feeling positive about others), growth (e.g. being a more effective person, coping more effectively, becoming a stronger person, and handling most things), reprioritization (e.g. putting less emphasis on material things, living life more simply, and changing priorities in life), and empathy (e.g. being more compassionate to those in similar situations, sensitive to the needs of others, and caring about others).

Until now, little attention has been paid to the specific types of benefits that caring may invoke. Several suggestions have been offered to explain how caring leads to positive changes among young people. For instance, caring tasks may lead to experiences of closeness and reciprocity in relationships (Nigel et al., Citation2003), promote a positive self-concept (Bolas et al., Citation2007; Earley et al., Citation2007), or enable skills development in terms of a real-world learning setting (Siskowski, Citation2009). However, no previous studies have compared benefit finding between young carers and their peers without caring roles which would help establish the benefits that are associated with caring, if any. Research shows that any young person may report experiencing some level of benefit finding in relation to difficult events in their life on each of the six dimensions described (Cassidy et al., Citation2014b). However, there are likely to be individual differences in the extent to which benefits are found, in which case it can be hypothesized that greater benefit finding may mitigate the potential negative impact on young carers’ mental health and promote their well-being.

Previous studies exclusively reported on benefit finding related to caring, and thus provided limited information regarding this assumption. Their emphasis on benefit finding related to caring can be a weakness, because as well as the challenges of caring itself, young carers have to contend with everyday life stressors. The many other life domains that are important for youth, which can also lead to benefit finding among young carers, have been neglected thus far. In addition, this method involves potential measurement errors. Notably, social desirability issues may have been prompted when asked directly about the positive aspects of caring.

The current study addressed this limitation by examining benefit finding in response to general life stress and its association with mental well-being in youth with ongoing or former caring experiences, hereafter referred to as young carers, and those without such caring experiences. Using the benefit finding measure proposed by Cassidy et al. (Citation2014b), the respondents considered benefits related to the difficulties that they subjectively perceived as important to their biography along different dimensions of benefit finding. The current study proposes a new understanding of positive outcomes in young carers and it provides answers to the following main research questions:

Is there an association between being a young carer and degrees and profiles of benefit finding in response to life stress?

Does benefit finding in response to life stress moderate the association between having caring experiences (yes/no) and mental well-being in adolescents?

To this end, we first addressed whether caring was associated with finding benefits in response to past challenges by comparing benefit finding scores between young carers and their peers without caring experiences. As different types of stressors are likely to lead to different types of positive changes, we also examined group differences regarding the specific nuances of benefit finding, making use of the six dimensions: acceptance, family bonds, relationships, growth, reprioritization, and empathy.

Second, we addressed whether young carers’ positive perceptions of past adversity in their lives, that is, their benefit finding, made a difference in their current mental well-being. We tested whether the associations between having caring experiences (yes/no) and mental well-being varied as a function of levels of overall benefit finding (see ); and examined the associations between the different dimensions of benefit finding and mental well-being in young carers.

Using an exploratory approach, we further examined whether the degrees of benefit finding and their effects on mental well-being varied as a function of whether young carers (a) related their benefit finding to the caring role or not, and (b) were current or former carer.

Method

Participants and procedure

The study sample comprised 2,525 adolescents aged 15–21 years (59.6% female, Mage = 17.73, SD = 1.55) who attended schools and vocational training in the German-speaking part of Switzerland. The majority of the participants (71.5%) reported ‘Swiss’ as their nationality (participants could choose multiple nationalities). Most of the participants (85.6%) were in vocational education and training (VET), 8.3% in general education schools, and 6.1% in other types of educational situations, such as a preparatory course.

To achieve a diverse sample of adolescents, participants were accessed through different schools and companies who offered vocational training in German-speaking parts of Switzerland. We contacted 19 schools and one company who offered vocational training to ask them if they would participate in our study (where possible units of entire schools, classes, or teams). A total of eight institutions (five vocational education schools, one company offering vocational training, two high schools, and one school offering transitional options for students who have not yet entered upper-secondary education) agreed to participate and invited their students and trainees to complete the survey. Before data collection, we provided the staff of the participating institutions with information letters for the potential participants and their parents as well as the materials required to conduct the survey (i.e. brief guidelines including the link to access the online survey). Participants completed a self-administered online questionnaire during school/working hours or as home assignments between May 2018 and November 2019. Adolescents were informed about the study aims (i.e. main aim: an examination of psychosocial well-being of adolescents in education; additional aims included finding out more about potential caring roles of adolescents), confidentiality issues, and the voluntary nature of participation. Thus, they completed and submitted the questionnaire only if they agreed to participate. The participants were not compensated for taking part in the study. The completion of the entire survey took approximately 25 minutes. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at the University of Zurich.

Instruments

Caring experiences

Potential ongoing or former caring activities were assessed using a set of questions. Participants answered whether there was a person they felt close to who needed support in day-to-day life because of health problemsFootnote1 (min 2 on a scale that ranged from 0 = no help to 3 = a lot of help). Additionally, adolescents provided information on the frequency of their caring tasks (‘Please indicate how often you have helped the person during the past 6 months’.) separately for four domains: domestic/household care (e.g. cleaning, grocery shopping, cooking, looking after siblings, etc.), personal/intimate care (e.g. help with eating, washing or toileting, help with medication, etc.), social/emotional care (e.g. cheering up, keeping company, making sure the person is safe, accompany, etc.), and instrumental care (e.g. coordination of appointments, paying bills, doing phone calls, organizing transportation, etc.). The frequency of caring tasks was assessed on a 5-point scale (1= never, 2 = rarely, 3 = now and then, 4 = often, 5 = very often). To determine whether ongoing caring activities were indicated, a minimum frequency of now and then (i.e. 3 on the 5-point frequency scale) in at least one of the four caring domains was used as a cut-off.

Participants who reported that there was a person who needed help because of health problems that they currently did not support in any of the four caring domains (1 = never or 2 = rarely) answered the question of whether they previously supported the person (yes or no). Furthermore, all participants were asked about their potential past caring activities (‘Did you provide assistance to one person or multiple persons who needed support because of health problems earlier in your life?’) with the response options (1 = yes, I used to provide support for someone, or 2 = no, this situation does not apply to me). A ‘yes’ answer to one of these two questions indicated former caring activities.

Adverse life events

To assess adverse life events in the youth’s past, a checklist of 26 events was developed based on the example provided by pre-existing instruments for adolescents (i.e. Low et al., Citation2012; Neuenschwander, Citation1998). Potentially critical events were sampled from multiple domains: family (e.g. change in family composition, financial problems), school/career (e.g. grade repeated, dropped out of a training/school), social (e.g. break up, mobbing), and personal (e.g. addiction problems, accidents). The instructions of the checklist asked the participants if they had experienced each event (0 = no; 1 = yes), and to rate the subjective stressfulness of the experienced events on a 5-point scale (0 = not at all stressful, 4 = very stressful). The total number of life events rated as rather stressful (3) or very stressful (4) were calculated, such that scores on the Checklist of Adverse Life Events (CALE) had a possible range from 0 to 26.

Benefit finding

The 28-item General Benefit Finding Scale (GBFS; Cassidy et al., Citation2014b) was used to measure adolescents’ subjective experience of positive changes after adversity. The introductory text of the questionnaire asked participants to consider difficult times they had had in their lives and respond to the scale in relation to how they felt living through those difficult times. Participants then rated how much each item describing a potential benefit (e.g. ‘Led me to be more accepting of things’, ‘Taught me how I can handle most things’) was true for them (0 = not true at all, 4 = absolutely true). The scale’s overall benefit finding score was derived by calculating the mean of the responses across all 28 items (standardized Cronbach’s Alpha α = .94). The six subscale scores were derived by calculating the mean of the responses in the corresponding subscale items: acceptance (5 items, α = .78), family bonds (4 items, α = .81), relationships (4 items, α = .73), growth (6 items, α = .86), reprioritization (4 items, α = .70), and empathy (5 items, α = .77). The items used in this study were translated into German by two independent researchers and then carefully discussed to find a consensus for the final wording appropriate for Swiss adolescents in this study.

After the benefit finding questionnaire, participants were asked to report which events in their life they primarily thought about when they rated the statements. A multiple-choice answer format including a list of all life events reported by the participants (see section Adverse Life Events), if applicable ‘My caring tasks for close people’, and ‘other’ with an open-ended text box as options.

Mental well-being

Mental well-being was assessed using the German version of the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (WEMWBS; Lang & Bachinger, Citation2017; Tennant et al., Citation2007). Items were rated on a 5-point scale (1 = none of the time, 5 = all of the time), and the overall mental well-being score was derived by summing up the responses across all 14 items. The standardized Cronbach’s alpha was .89.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were conducted using the R software. The inferential statistical procedure included analyses of covariance (ANCOVA) to compare the levels of benefit finding between groups as well as multivariate hierarchical regression analyses. We used the CALE score as a covariate throughout the analyses. Including CALE scores, that is, adverse events that may not be directly related to caring, allowed us to control for the potential confounding effect that the degrees of benefit finding and their association with mental well-being would be higher among young carer participants due to elevated numbers of experienced life events among this group. To account for the effects of multiple testing, we applied a significance level of α = .01.

Results

Participants were classified into groups based on their ongoing or former caring activities for a close person or close persons with health problems. A total of 601 adolescents reported that they ongoingly provided some type of care (i.e. domestic/household, social/emotional, personal/intimate, or instrumental) to a family member or close friend with a need for support caused by health problems. In addition, 536 participants reported that they had previously supported a close person with health problems. Together, these participants were classified as young carers (n = 1,137) and the remaining were classified as without caring experiences (n = 1,388).

The sample characteristics, including differences between groups, are shown in . The groups differed in terms of demographics and the number of experienced (adverse) life events. Demographics were also related to the study variables (benefit finding, and mental well-being). Consequently, demographic variables were included in the analyses as covariates to adjust for potential confounding effects. Among the young carers, 28.9% (n = 328) indicated that their answers regarding the benefits they identified (GBFS answers) were related to their caring role. The proportions did not differ significantly between the group with ongoing caring activities and the group with former caring activities nor was this variable associated with the demographics.

Table 1. Characteristics of the sample and differences between groups.

Association between caring and benefit finding

Mean comparisons between young carers and peers without caring experiences

To test our first research question of whether the experience of caring for a family member or close friend was associated with higher levels of benefit finding, one-way ANCOVAs were conducted to compare GBFS scores between the group of young carers and the group without caring experiences while controlling for demographics (gender, age, and nationality) and CALE scores. As shown in , there were statistically significant differences in the overall benefit finding, growth, and empathy scores between the groups. Comparing the estimated marginal means of these scores showed that young carers consistently had higher levels of benefit finding (overall, growth, and empathy) above and beyond the number of adverse life events and demographics (see ).

Table 2. Analyses of covariance in benefit finding (overall and subscales) with caring experiences as factor and demographics and adverse life events as covariates, test statistics, effect size and estimated marginal means of levels of benefit finding by comparison group.

Differences among young carers

displays the results of the multivariate regression analyses of the background variables that predict benefit finding scores among young carers. Regarding our exploratory research question, the results suggested that participants who linked their identification of benefits to their caring roles had higher levels of overall benefit finding (t(1136) = 2.64, p = .009), relationships (t(1136) = 3.47, p < .001), and empathy (t(1136) = 3.34, p < .001) than those who did not. Former as compared to ongoing caring activity was not associated with benefit finding (overall nor subscales). The unstandardized coefficients, test statistics, and explained variance are presented in .

Table 3. Multivariate regression analyses predicting benefit finding scores (overall and subscales) in young carers (unstandardized coefficients).

Associations between benefit finding and mental well-being

Benefit finding as a moderator

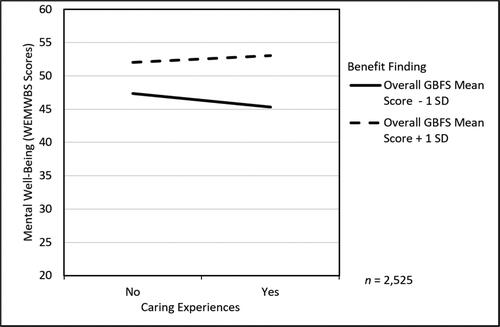

To test the second research question of whether benefit finding moderated the association between caring experiences and mental well-being, a hierarchical multiple regression analysis was conducted. In the first step, the covariates (gender, age, nationality, and CALE scores), as well as the dummy variable caring experiences and overall benefit finding scores were entered. These variables accounted for a significant amount of variance in the WEMWBS scores (adj. R2 = .19, F(6, 2518) = 100.50, p < .001). Next, the interaction term between caring experiences and overall GBFS scores was added to the regression model, which accounted for a significant additional proportion of the variance in mental well-being (Δ adj. R2 = .01, ΔF(1, 2517) = 22.27, p < .001, b = 2.09, t(2524) = 4.72, p < .001; for more details, see Appendix). As illustrated in , the effect of having caring experiences on mental well-being was only negative among adolescents with a low level of overall benefit finding.

Figure 2. Moderation analyses of caring experiences and overall benefit finding scores predicting levels of mental well-being in adolescents adjusted for gender, age, nationality, and the number of adverse life events. WEMWBS = Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale; GBFS = General Benefit Finding Scale.

Differences by benefit finding dimensions

To examine the role of different dimensions of benefit finding for mental well-being we ran hierarchical multiple regression analyses of GBFS overall and subscale scores predicting WEMWBS scores among young carers. The results are presented in . Above and beyond demographics, overall GBFS scores, as well as the GBFS subscale of relationships and growth, were positively associated with the WEMWBS scores in young carers, whereas the GBFS subscale of empathy was negatively associated with WEMWBS scores. There were no significant associations between mental well-being and the dimensions of acceptance, family bonds, or reprioritization.

Table 4. Multivariate regression analyses of benefit finding predicting mental well-being in young carers (unstandardized coefficients).

Differences among young carers

We further explored the differences between the subgroups of young carers, that is, current vs. former, and benefit finding related to caring vs. not related to caring. displays the hierarchical regressions of the GBFS scores as predictors of WEMWBS scores separately for all subgroups. The positive association between the GBFS subscale of relationships and the WEMWBS scores was only found when using the overall sample and the subsample of young carers who related benefit finding to caring. All other patterns of association were similar across the subgroups of young carers.

Discussion

The aim was to examine the association between being a young carer and benefit finding in different dimensions, and if benefit finding moderated the negative association between caring experiences and mental well-being. The results showed that caring was associated with benefit finding among adolescents. As expected, adolescents with ongoing or former caring tasks reported higher levels of benefit finding (overall, dimension of growth, and empathy) than their peers without such experiences. In addition, young carers who linked their identification of benefits to caring had higher levels of benefit finding (overall, relationships, empathy) than those who did not. In line with our prediction, the results also showed that benefit finding moderated the negative association between caring experiences and mental well-being.

However, we would like to note that not all types of identified benefits seem to be positively associated with mental well-being in young carers. The evidence from this study suggests that perceived changes in terms of personal growth, including feelings of inner strength and self-confidence, could be especially favorable for the mental well-being of young carers. Benefit finding in the form of sensitivity to others’ needs, in contrast, appears to impede their mental well-being. It seems that even though empathy can be perceived as a positive feature, an excess in orienting toward others’ needs may not be beneficial for the mental well-being of young carers. Another aspect of benefit finding seemed to be confined to specific participant groups. Namely, the benefit finding dimension of relationships was positively associated with mental well-being, but only among participants who related the perceived benefits to their caring role. As such, our findings suggest that it will be important for future research to further examine these separate dimensions of benefit finding and their possibly unique effects.

Most previous studies on benefit finding solely sampled young people with caring experiences, and they mainly recruited participants through support services and young carers projects (e.g. Cassidy et al., Citation2014b; Gough & Gulliford, Citation2020). Thus, previous studies have targeted young carers who already received some type of support and/or recognition in their caring role, whereas the present sample is more likely to be representative of the young carer population. Recruitment through schools and companies, combined with the large sample size, suggests a solid basis for collecting insights regarding caring experiences and benefit finding among Swiss adolescents.Footnote2 However, due to inconsistencies in the definition and recruitment of young carers, the comparability of our findings with existing literature on young carers is limited. While other studies have narrowed the study population of young carers to specific situations such as the context of parental illness (e.g. Pakenham & Cox, Citation2018) or specific types of health problems of the care recipient (e.g. Celdrán et al., Citation2009), we applied a broader definition that was inclusive of many different situations of current and former young carers.

In addition, previous studies have mainly approached young carers by addressing them directly in their role as such, and thus required young people to be aware of their caring role. However, our study applied a different sampling approach by addressing them as adolescents. Therefore, in our study, participants who met the criteria of a young carer may have been unaware of their caring role. Such an approach is highly needed, as many young people with caring tasks do not self-identify as carers, often because they perceive their situation and tasks as normal or reject labeling their role for other reasons (Bolas et al., Citation2007; Leu et al., Citation2018; Smyth et al., Citation2011). For instance, the finding that less than one third of the young carer participants related their benefit finding to the caring role should be interpreted in this light. Due to these limitations of compatibility, the results of our study must be interpreted with caution, and the potential benefits and unintended consequences of self-identification as a young carer should be addressed in future research.

Nevertheless, the novel approach used in this study produced several exploratory findings that prompt hypotheses for future studies on young carers. For instance, the results of the present study raise the possibility that the lifetime prevalence of caring activities among adolescents is even higher than what may have been expected. Almost half of the adolescents who participated in this study reported some caring experiences in their lives, that is, 24% of ongoing caring activities and 21% of former caring activities. These numbers are substantially higher than the national 8% prevalence estimate of young carers aged 9–15 years (Leu et al., Citation2019) but comparable with sample proportions found in a US study conducted by Greene et al. (Citation2017; i.e. current caring activity: 22%, former caring activity: 23%). The latter is the only study that we know of that asked young people (age range: 18–24 years) about their current and former caring roles.

Another exploratory analysis of this study addressed the comparison of adolescents with former caring activities and those with ongoing caring activities. As the results did not show substantial differences in benefit finding and its impact on mental well-being, we assume that the experience of caring could have a formative impact on youth beyond involvement in present caring. Moreover, the timing and duration of caring activities and their impact on youth are additional important aspects of future research.

The present findings suggest that it may be valuable to help young carers reflect on their strengths in coping with difficulties, thereby promoting their self-efficacy and helping them develop coping strategies. However, this study has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design of the present study limits the interpretability of causation; thus, we urge caution in developing such interventions prematurely. To broaden knowledge about benefit finding in the context of young carers, future studies should apply longitudinal designs and further determine which constellations and factors (inner and external resources) promote benefit finding. Second, the present study conceptualized caring experiences as a simplified yes or no variable. Thus, the manifold experiences related to caring tasks (e.g. level of responsibility, restrictions due to caring) and its complex context (e.g. age when caring, relationship to care recipient) could not be captured. Third, there is a risk of potential bias in relation to the benefit finding self-report measure in terms of individuals inflating their perceptions of change in retrospect. However, in this study, we were primarily interested in benefit finding in terms of personal capacity to see positive aspects, and therefore, the perception of the outcome is more relevant than the outcome per se. Fourth, by not asking respondents to rate the importance of events for their identified benefits, it remains unclear which characteristics of the caring situation or events related to caring were the predominant triggers of benefit finding (e.g. chronic stress or traumatic events).

To conclude, our findings add significant information to a growing body of research on benefit finding and its possible protective impact on mental health in young carers. This is the first comparative study on benefit finding between adolescents with and without caring experiences, and it is the first study to apply a multidimensional instrument to assess benefit finding in young carers, showing that benefit finding occurs in young carers more than their peers, and that it seems to moderate associations between caring experiences and mental well-being.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all institutions and students who participated in this research.

Disclosure statement

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Participants were instructed that health problems could be physical or mental difficulties or difficulties with cognition (e.g., a disability, depression, addiction, infirmities of old age, chronic disease such as cancer, etc.) that result in an enduring or recurring need for emotional or practical help; and that with the term health problem we did not mean a temporary flue, cold, or injury.

2 Besides female adolescents being slightly better represented than male adolescents; and adolescents in VET being somewhat overrepresented (85.6 vs. 63.6%), whereas those in general education school underrepresented (8.3% vs. 27.5%), a relatively balanced sample composition regarding the Swiss population of adolescents in upper secondary education was indicated (Federal Statistical Office, Citation2020).

References

- Areguy, F., Mock, S. E., Breen, A., van Rhijn, T., Wilson, K., & Lero, D. S. (2019). Communal orientation, benefit-finding, and coping among young carers. Child & Youth Services, 40(4), 363–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/0145935X.2019.1614906

- Bolas, H., van Wersch, A., & Flynn, D. (2007). The well-being of young people who care for a dependent relative: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Psychology & Health, 22(7), 829–850. https://doi.org/10.1080/14768320601020154

- Boyle, G. (2020). The moral resilience of young people who care. Ethics and Social Welfare, 14(3), 266–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/17496535.2020.1771606

- Cassidy, T., & Giles, M. (2013). Further exploration of the Young Carers Perceived Stress Scale: Identifying a benefit-finding dimension. British Journal of Health Psychology, 18(3), 642–655. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12017

- Cassidy, T., Giles, M., & McLaughlin, M. (2014a). Benefit finding and resilience in child caregivers. British Journal of Health Psychology, 19(3), 606–618. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12059

- Cassidy, T., McLaughlin, M., & Giles, M. (2014b). Benefit finding in response to general life stress: Measurement and correlates. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine, 2(1), 268–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/21642850.2014.889570

- Celdrán, M., Triadó, C., & Villar, F. (2009). Learning from the disease: Lessons drawn from adolescents having a grandparent suffering dementia. International Journal of Aging & Human Development, 68(3), 243–259. https://doi.org/10.2190/AG.68.3.d

- Earley, L., Cushway, D., & Cassidy, T. (2007). Children’s perceptions and experiences of care giving: A focus group study. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 20(1), 69–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070701217830

- Federal Statistical Office. (2020). Education statistics 2019. Neuchâtel, Switzerland. https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home.assetdetail.12607178.html

- Gough, G., & Gulliford, A. (2020). Resilience amongst young carers: Investigating protective factors and benefit-finding as perceived by young carers. Educational Psychology in Practice, 36(2), 149–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667363.2019.1710469

- Greene, J., Cohen, D., Siskowski, C., & Toyinbo, P. (2017). The relationship between family caregiving and the mental health of emerging young adult caregivers. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 44(4), 551–563. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-016-9526-7

- Joseph, S. (2011). What doesn’t kill us: The new psychology of posttraumatic growth. Basic Books.

- Joseph, S., Becker, S., Becker, F., & Regel, S. (2009). Assessment of caring and its effects in young people: Development of the Multidimensional Assessment of Caring Activities Checklist (MACA-YC18) and the Positive and Negative Outcomes of Caring Questionnaire (PANOC-YC20) for young carers. Child: Care, Health and Development, 35(4), 510–520. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2009.00959.x

- Joseph, S., Sempik, J., Leu, A., & Becker, S. (2020). Young carers research, practice and policy: An overview and critical perspective on possible future directions. Adolescent Research Review, 5(1), 77–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-019-00119-9

- Kallander, E. K., Weimand, B., Ruud, T., Becker, S., van Roy, B., & Hanssen-Bauer, K. (2018). Outcomes for children who care for a parent with a severe illness or substance abuse. Child & Youth Services, 39(4), 228–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/0145935X.2018.1491302

- Lakman, Y., & Chalmers, H. (2019). Psychosocial comparison of carers and noncarers. Child & Youth Services, 40(2), 200–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/0145935X.2018.1553614

- Lang, G., & Bachinger, A. (2017). Validation of the German Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (WEMWBS) in a community-based sample of adults in Austria: A bi-factor modelling approach. Journal of Public Health, 25(2), 135–146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-016-0778-8

- Lechner, S. C., Tennen, H., & Affleck, G. (2009). Benefit-finding and growth. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Oxford library of psychology. Oxford handbook of positive psychology (2nd ed., pp. 633–640). Oxford University Press.

- Leu, A., & Becker, S. (2019). Young carers. In H. Montgomery (Ed.), Oxford bibliographies in childhood studies. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/OBO/9780199791231-0120

- Leu, A., Frech, M., & Jung, C. (2018). Young carers and young adult carers in Switzerland: Caring roles, ways into care and the meaning of communication. Health & Social Care in the Community, 26(6), 925–934. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12622

- Leu, A., Frech, M., Wepf, H., Sempik, J., Joseph, S., Helbling, L., Moser, U., Becker, S., & Jung, C. (2019). Counting young carers in Switzerland - A study of prevalence. Children & Society, 33(1), 53–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12296

- Low, N. C., Dugas, E., O’Loughlin, E., Rodriguez, D., Contreras, G., Chaiton, M., & O’Loughlin, J. (2012). Common stressful life events and difficulties are associated with mental health symptoms and substance use in young adolescents. BMC Psychiatry, 12(1), 116. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-12-116

- McDougall, E., O’Connor, M., & Howell, J. (2018). ‘Something that happens at home and stays at home’: An exploration of the lived experience of young carers in Western Australia. Health & Social Care in the Community, 26(4), 572–580. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12547

- Neuenschwander, M. P. (1998). Schule und Identität im Jugendalter I. Kurzdokumentation der Skalen und Stichproben. Forschungsbericht Nr. 18 [School and Identity in Youth I. Brief methodological report].

- Nigel, T., Stainton, T., Jackson, S., Cheung, W. Y., Doubtfire, S., & Webb, A. (2003). Your friends don’t understand’: Invisibility and unmet need in the lives of ‘young carers’. Child & Family Social Work, 8(1), 35–46. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2206.2003.00266.x

- Pakenham, K. I., & Bursnall, S. (2006). Relations between social support, appraisal and coping and both positive and negative outcomes for children of a parent with multiple sclerosis and comparisons with children of healthy parents. Clinical Rehabilitation, 20(8), 709–723. https://doi.org/10.1191/0269215506cre976oa

- Pakenham, K. I., & Cox, S. D. (2018). Effects of benefit finding, social support and caregiving on youth adjustment in a parental illness context. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(8), 2491–2506. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1088-2

- Pakenham, K. I., Chiu, J., Bursnall, S., & Cannon, T. (2007). Relations between social support, appraisal and coping and both positive and negative outcomes in young carers. Journal of Health Psychology, 12(1), 89–102. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105307071743

- Robison, O. M. E. F., Inglis, G., & Egan, J. (2020). The health, well-being and future opportunities of young carers: A population approach. Public Health, 185, 139–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2020.05.002

- Shifren, K., Hillman, A., & Rowe, A. (2014). Early caregiver experiences, optimism, and mental health: Former young caregivers and emerging adult caregivers. International Journal of Psychology Research, 9(4), 361–383.

- Siskowski, C. T. (2009). Adolescent caregivers. In K. Shifren (Ed.), How caregiving affects development: Psychological implications for child, adolescent, and adult caregivers. American Psychological Association.

- Smyth, C., Blaxland, M., & Cass, B. (2011). So that’s how I found out I was a young carer and that I actually had been a carer most of my life’. Identifying and supporting hidden young carers. Journal of Youth Studies, 14(2), 145–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2010.506524

- Stamatopoulos, V. (2018). The young carer penalty: Exploring the costs of caregiving among a sample of Canadian youth. Child & Youth Services, 39(2–3), 180–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/0145935X.2018.1491303

- Tennant, R., Hiller, L., Fishwick, R., Platt, S., Joseph, S., Weich, S., Parkinson, J., Secker, J., & Stewart-Brown, S. (2007). The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS): Development and UK validation. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 5, 63. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-5-63