Abstract

Objective

This study applied the theory of reasoned goal pursuit (TRGP) in predicting physical activity among Australian undergraduate students, providing the first empirical test of the model.Methods: The research comprised an elicitation study (N = 25; MAge= 25.76, SDAge= 11.33, 20 female, 5 male) to identify readily accessible procurement and approval goal beliefs and behavioural, normative, and control beliefs; and, a two-wave prospective online survey study (N = 109; MAge = 21.88, SDAge = 7.04, 63 female, 46 male) to test the tenets of the TRGP in relation to meeting World Health Organization physical activity guidelines during the COVID-19 pandemic among first year university students.Results: A linear PLS-SEM model displayed good fit-to-data, predicting 38%, 74%, and 48% of the variance in motivation, intention, and physical activity, respectively. The model supported the majority of hypothesised pattern of effects among theory constructs; in particular, the proposition that beliefs corresponding to procurement and approval goals would be more consequential to people’s motivation and, thus, their intentions and behaviour, than other behavioural and normative beliefs, respectively.Conclusions: Results lend support for the TRGP and sets the agenda for future research to systematically test the proposed direct, indirect, and moderation effects for different health behaviours, populations, and contexts.

Supplemental data for this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2022.2026946 .

Attempts to identify effective and parsimonious models to predict and understand human behaviour is a core element of investigation in fields such as social psychology and health. For the most part, these models tend to be informed by a single theoretical approach. However, in recent years scholars have attempted to expand upon these models and theories, proposing and testing integrated models of behaviour (Hagger & Hamilton, Citation2020). Such models are often coined ‘hybrid models’, as they draw constructs and specified relations from more than one existing theory to arrive at a new theory. The rationale for model integration is based on arguments that no one theory can be considered definitive in explaining behaviour and, thus, should be open to modification to enable other constructs to be added that may provide more efficacious explanations of outcomes. One such recent integrated model of behaviour is the theory of reasoned goal pursuit (Ajzen & Kruglanski, Citation2019), integrating the theory of planned behaviour (Ajzen, Citation1991) and goal systems theory (Kruglanski et al., Citation2002).

The theory of reasoned goal pursuit (TRGP; Ajzen & Kruglanski, Citation2019) is a promising new model that can be used to identify the modifiable predictors of health behaviour. The TRGP is an extension of the theory of planned behaviour (TPB; Ajzen, Citation1985, Citation1991, Citation2012; Ajzen & Schmidt, Citation2020) designed to take into account the active goals that motivate people’s behaviour. In a typical application of the TPB, the focus is on a behaviour of interest to the investigator, be it drinking or smoking, exercising, dieting, using public transit, voting in elections, and so forth. Rarely, if ever, is an attempt made to explore the extent to which the behaviour under consideration is actually of concern to the study’s participants. Thus, for example, in an effort to address obesity in the population, a researcher may try to understand what motivates people to engage in physical activity irrespective of whether the participants would have contemplated engaging in physical activity had they not been asked about this behaviour. In other words, investigators relying on the TPB generally do not pay enough attention to why, in their everyday lives, people consider engaging in a particular behaviour in the first place. The TRGP fills this void by suggesting that the motivation to consider performing a particular behaviour rests, to a large extent, on the desire to attain one or more goals. A person who would like to lose weight, for example, may consider engaging in physical activity or going on a weight-loss diet, behaviours designed to attain the weight-loss goal. In the sections below, we briefly summarise the TPB and its extension, the TRGP.

Theory of planned behaviour

The research reported in this article is based on the conceptual framework provided by the original formulation of the TPB (Ajzen, Citation1985) and its more recent presentation (see Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation2010). However, we also mention certain simplifications that have guided much past research with the theory.

In the TPB, intention, defined as readiness to engage in a particular behaviour, is considered to be the immediate antecedent of the behaviour in question; the stronger the intention, the more likely it is that the behaviour will follow. However, unanticipated events, insufficient time or resources, lack of requisite skills, and many other factors may prevent people from acting on their intentions. The degree to which people have actual control over the behaviour depends on their ability to overcome barriers of this kind and on the presence of such facilitating factors as past experience and assistance provided by others. In light of these considerations, the TPB postulates that degree of behavioural control moderates the effect of intention on behaviour; the greater the actor’s actual control over the behaviour, the more likely it is that the intention will be carried out (for a discussion of the intention x control interaction, see Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation2010, pp. 65–66). However, because it is usually very difficult or impossible to ascertain the degree to which people have actual control over a given behaviour, perceived behavioural control is typically used as a proxy for actual control. To the extent that perceived behavioural control is veridical, it can serve as a proxy for actual control and contribute to the prediction of the behaviour in question.

Although the original TPB postulated an interaction between intention and perceived behavioural control in their effects on behaviour, empirical research has tended to find only main effects (see Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation2010, pp. 65–68). Subsequent formulations (e.g. Ajzen, Citation1991, Citation2012) and most empirical applications of the TPB have therefore used a simplified model in which perceived behavioural control is treated as a direct determinant of behaviour with a status equal to that of intention. Nevertheless, some evidence for the postulated interaction between intention and perceived behavioural control can be found in meta-analyses of relevant empirical research (Hagger et al., Citation2022; Yang-Wallentin et al., Citation2004), but these investigators also discuss the difficulties of estimating an effect of this kind.

Intention, the immediate antecedent of behaviour, is assumed to be based on three kinds of considerations: beliefs about the likely consequences and experiences associated with the behaviour (instrumental and experiential behavioural beliefs, respectively), beliefs about the normative expectations and behaviours of significant others (injunctive and descriptive normative beliefs, respectively), and beliefs about the presence of factors that may facilitate or impede performance of the behaviour (control beliefs). In their respective aggregates, behavioural beliefs produce a favourable or unfavourable attitude toward the behaviour; normative beliefs result in perceived social pressure or subjective norm; and control beliefs give rise to perceived behavioural control.

Again, from a theoretical perspective, perceived behavioural control does not exert a direct influence on intention. Instead, it is expected to moderate the effects of attitude and subjective norm (see Ajzen, Citation1985; La Barbera & Ajzen, Citation2020). Thus, perceptions of control are expected to determine the extent to which attitudes and subjective norms influence intentions to perform a target behaviour, for example exercise. However, because empirical investigations have revealed mostly main effects of perceived behavioural control, a commonly used simplified model has treated perceived behavioural control as a direct determinant of intention, together with attitude and subjective norm. Even so, investigators (e.g Hukkelberg et al., Citation2014; Kothe & Mullan, Citation2015; La Barbera & Ajzen, Citation2020, Citation2021; Yzer & Van Den Putte, Citation2014) have been able to obtain some evidence for the postulated interaction effects. To summarise, from a theoretical perspective perceived behavioural control moderates the effect of intention on behaviour and the effects of attitude and subjective norm on intention. In the present study, we examined both the direct as well as the moderating effects of perceived behavioural control.

A large number of empirical investigations have shown that the TPB provides a useful conceptual framework to predict health behaviour and, more specifically, physical activity behaviour, generally supporting the predictions of the (simplified) model and accounting for substantive variance in intention and behaviour in multiple health contexts and population groups (e.g. Armitage & Conner, Citation2001; Hamilton et al., Citation2020; McEachan et al., Citation2011; Rich et al., Citation2015). However, the TPB does not take into account the active goals that motivate people’s behaviour. The present study builds on this research by exploring the role of people’s active procurement and approval goal beliefs as posited in the TRGP.

Theory of reasoned goal pursuit

The TRGP (Ajzen & Kruglanski, Citation2019) extends the TPB by considering the goals that motivate people’s behaviour in a given behavioural domain. A distinction is made between outcomes a person may be motivated to attain, termed procurement goals (e.g. to improve physical health or maintain mental health); and approval from significant others the person may seek, termed approval goals (e.g. to attain approval from one’s partner). It is assumed that people are likely to consider performing a given behaviour to the extent that they see the behaviour as promoting the attainment of their procurement and/or approval goals. This implies that behavioural beliefs concerning outcomes or experiences that correspond to procurement goals are more consequential than other kinds of behavioural beliefs and, similarly, that normative beliefs regarding the expectations or behaviours of significant others who are the subject of approval goals have greater weight than normative beliefs concerning other social referents. Moreover, when people believe that performing the behaviour is likely to attain their procurement goals, the effect of other behavioural beliefs on their attitudes is likely to decline and, in a parallel manner, when people believe that performance of the behaviour is likely to attain their approval goals, the effect of other normative beliefs on their subjective norms is likely to be weakened.

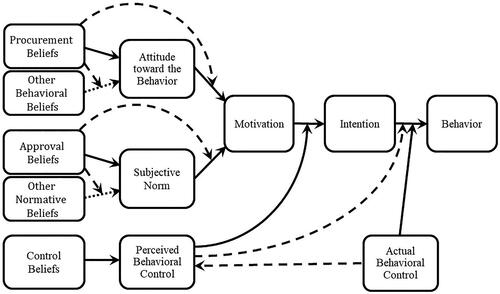

Rather than postulating a direct effect of attitude and subjective norm on intention, in the TRPG these variables provide the basis for a person’s motivation to engage in the behaviour, but a high level of motivation is not sufficient for the formation of a favourable intention. Strong motivation is expected to produce an intention to engage in the behaviour only when individuals believe that they have control over the behaviour under consideration. Thus, the effect of motivation on behavioural intention is assumed to be moderated by perceived behavioural control. Finally, the TRGP suggests that the effects of attitude and subjective norm on motivation is stronger when the behaviour is perceived to serve the attainment of active procurement and approval goal beliefs, respectively. The version of the TRGP tested in the present study is shown in .

Physical activity in COVID-19

In the context of this study, we provide a first empirical test of the TRGP in predicting university students’ physical activity during the COVID-19 pandemic. Globally, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has made substantive and life-altering changes to people’s way of living. To minimise transmission of the virus, many countries instituted restrictions on individuals’ movement, including facial mask mandates, ‘stay at home’ orders, physical distancing rules, closure of sporting and exercise facilities, and travel and recreation restrictions (Gostin & Wiley, Citation2020; Hale et al., Citation2020). Although vaccination offers hope of returning to ‘normal’, the world population rate of fully vaccinated individuals is just over 40% (as of 27th November 2021; https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/share-people-fully-vaccinated-covid?tab=table) and countries such as USA, Russia, and South Africa are witnessing a slowing of vaccine uptake. Until a global vaccination roll-out has occurred, restrictions will remain a cornerstone to reducing the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19) and preventing future outbreaks (Gozzi et al., Citation2021; Rubin et al., Citation2021). However, while the world is expending large amounts of energy and resources into tackling the COVID-19 pandemic, it has largely neglected another pandemic it has been facing for many years – physical inactivity (Hall et al., Citation2021; Kohl et al., Citation2012).

Global estimates indicate that 1 in 4 adults and 3 in 4 adolescents (aged 11-17 years) do not meet the World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations on physical activity for health (Bull et al., Citation2020; Guthold et al., Citation2018, Citation2020; World Health Organization, Citation2018), with millions of deaths per year and enormous economic burdens attributed to physical inactivity (World Health Organization, Citation2018). Of emerging concern, though, are studies that demonstrate reductions in physical activity due to COVID-19 (Caputo & Reichert, Citation2020; Stockwell et al., Citation2021). These changes in physical activity levels may be partially attributed to changes in individuals’ physical activity beliefs which have occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, individuals may believe COVID-19 restrictions make engaging in physical activity more difficult (Dwyer et al., Citation2020), or may view physical activity as increasingly important for their mental health due to COVID-19 related stressors or feelings of isolation due to restrictions on gatherings and movement (Caputo & Reichert, Citation2020). Extrapolating from research on other substantial events, such as natural disasters (Okazaki et al., Citation2015), the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to have lasting negative impacts on individuals’ physical activity performance. Together, this evidence should catalyse grave concern given the fact that deleterious effects of low levels of physical activity are well-documented (Lee et al., Citation2012).

Adults can obtain significant health benefits by accumulating at least 150 minutes of moderate intensity physical activity per week, 75 minutes of vigorous intensity physical activity per week, or an equivalent combination of moderate and vigorous intensity physical activity (World Health Organization, Citation2018). Despite these guidelines and the plethora of evidence on the benefits of sufficient physical activity, many Australian adults (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Citation2020), and indeed adults globally (World Health Organization, Citation2018), lead sedentary lifestyles. In particular, university students have been highlighted as an at-risk group (Irwin, Citation2004), and the COVID-19 pandemic has compounded this problem (López-Valenciano et al., Citation2020). To develop evidence-based behaviour-change interventions effective at encouraging physical activity behaviour among university students during a pandemic, it is important to identify the modifiable predictors of physical activity under these difficult circumstances.

The present study and hypotheses

The aim of the present study was to apply the TRGP in predicting physical activity behaviour among Australian undergraduate students during the COVID-19 shutdown period, providing the first test of the model. The study consisted of two phases. In the first phase, an elicitation study was conducted to identify active procurement and approval goal beliefs as well as accessible behavioural, normative, and control beliefs. In the second phase, a main study was conducted to test the TRGP in predicting physical activity intentions as well as prospectively measured adherence to physical activity guidelines. The following hypotheses were formulated.

H1: Behavioural beliefs predict attitude toward meeting the physical activity guidelines, and beliefs corresponding to procurement goals are more strongly related to the attitude than other behavioural beliefs.

H2: Normative beliefs predict subjective norm, and beliefs corresponding to approval goals are more strongly related to the subjective norm than other normative beliefs.

H3: Control beliefs predict perceived behavioural control.

H4: Attitude and subjective norm predict motivation to meet the physical activity guidelines.

H5: Motivation predicts intention to meet the physical activity guidelines (H5a), moderated by perceived behavioural control (H5b), such that the motivation-intention relation is stronger when perceived behavioural control is high rather than low.

H6: Intention to meet the physical activity guidelines predicts physical activity behaviour (H6a), moderated by perceived behavioural control (H6b), such that the relation between intention and behaviour is stronger when perceived behavioural control is high rather than low.

We also explored the possibility that behavioural beliefs involving procurement goal moderate the path of other behavioural beliefs to attitude and the path of attitude to motivation, and that normative beliefs involving approval goals moderate the path of other normative beliefs to subjective norm and the path of subjective norm to motivation. In addition, although the theory postulates interaction effects involving perceived behavioural control, we also tested its direct effects on motivation, intention, and behaviour; and its indirect effect on behaviour via motivation and intention.

Method

The research was carried out between April and May 2020. All procedures were approved by University Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) and in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration.

Elicitation study

An elicitation study was conducted on a sample of 25 undergraduate students from an Australian University in April, 2020 (MAge= 25.76, SDAge= 11.33, 20 female, 5 male). Participants were provided with a definition of physical activity guidelines, then asked to list their most salient active procurement goal beliefs (‘What is the most important personal goal you could achieve by meeting the physical activity guidelines each week during the coronavirus period?’) and their most salient active approval goal beliefs (‘Would you consider meeting the physical activity guidelines during the coronavirus period as a way to gain the approval of particular individuals or groups important to you? Please list any such individual or group whose approval you would be seeking.’). Participants where then asked to complete a belief elicitation questionnaire where they listed the advantages and disadvantages, those who would approve or disapprove, and potential barriers and facilitators towards meeting physical activity guidelines during the coronavirus period (Ajzen, Citation2006) (see Supplemental Material, Appendix A for the elicitation questionnaire). The most salient procurement goals were maintaining/improving physical health and maintaining/improving mental health, and the most salient approval goals were family and friends (although it should be noted that 13 participants stated they did not seek approval from anyone). The elicited procurement goals and approval goals are presented in , and the elicited behavioural, normative, and control beliefs are presented in .

Table 1. The elicited active procurement and approval goal beliefs for meeting physical activity guidelines each week in the coronavirus period.

Table 2. The elicited behavioural, normative, and control beliefs regarding meeting physical activity guidelines each week during the coronavirus period.

Main study

Participants and procedures

Participants were undergraduate first year students majoring in psychology recruited from a large university in Queensland, Australia. Students were eligible to participate if they did not have a medical condition which prevented them from undertaking regular physical activity of at least a moderate intensity. The main study was conducted in May 2020, at a time when government lockdown regulations allowed for exercise alone or in small family groups. Facilities such as gyms were closed, and team sport was not permitted. The study adopted a two-wave prospective online survey design, with participants (N = 150) completing self-report measures of constructs from the proposed model and demographic variables at Time 1. All eligible participants received partial course credit for participating. Two weeks later, at Time 2, participants were contacted via email to report their physical activity over the previous two weeks. Forty-one participants did not provide follow-up data, leaving a final sample of 109 participants (MAge= 21.88, SDAge= 7.04, 63 female, 46 male). As power in a PLS model can be inferred from the power of the most complex regression (Chin, Citation2010), a priori power analysis indicated the current study required a minimum sample of 73, allowing for a small effect size (R2=.15), a required power of .80, and alpha = .05 (Zhang & Yuan, Citation2018). Participants who completed both the baseline and follow-up survey did not differ from those who only completed the baseline survey in terms of age (t(148) = .51, p= .614) and sex (χ2(1)=.04, p = .851). However, there was a difference in baseline model statistics (F(8, 141)= 2.35, p = .021, Pillai’s Trace = .118); participants who completed only the baseline survey had a higher mean endorsement on control beliefs compared to those who completed both the baseline and follow-up surveys (F(1, 148)= 9.29, p = .003). Participants who completed the baseline survey only did not significantly differ from the final sample on any other baseline model statistics (ps > .065).

Measures

The TRGP variables were assessed at Time 1 using standard guidelines (Ajzen, Citation1991; Ajzen & Kruglanski, Citation2019) and consultation with the model’s founder and behaviour change experts. The target behaviour of physical activity was assessed at Time 2 and defined according to guidelines developed by the Department of Health (2019) for adults. See Supplemental Material, Appendix B for the main study questionnaire.

Procurement goal beliefs and behavioural beliefs

Participants rated each of the behavioural beliefs from the elicitation study in terms of its perceived likelihood (e.g. ‘If I meet the physical activity guidelines each week during the coronavirus period, it will improve my appearance’, scored 1 = Extremely Unlikely to 7 = Extremely Likely) and its subjective value (e.g. ‘How valuable are each of the following to you during the coronavirus period? - Improving my appearance’, scored 1 = Not at all to 7 = Extremely). The perceived likelihood of each outcome was multiplied by its subjective value and the resulting products were summed for the two most commonly elicited goal-related behavioural beliefs (improving physical health and improving mental health) and, separately, for the remaining six non-goal-related beliefs that significantly correlated with its relevant TPB construct of attitude.

Approval goal beliefs and normative beliefs

Participants rated each of the normative reference groups from the elicitation study in terms of their likelihood of providing approval (e.g. ‘How likely do you think it is that each the following people would approve of your meeting the physical activity guidelines each week during the coronavirus period? - My Friends’, scored 1 = Extremely Unlikely to 7 = Extremely Likely) and the value of that approval (e.g. ‘How much do you care whether each of the following people approve or don’t approve of what you do? - My Friends’, scored 1 = Not at all to 7 = Extremely). The same method was employed for normative beliefs. For each referent, perceived likelihood of approval was multiplied by the subjective value of approval and the products were summed separately for the two beliefs corresponding to the two approval goal referents (family and friends) and for the remaining two non-goal-related referents that significantly correlated with its relevant TPB construct of subjective norm.

Control beliefs

Each of the potential barriers to meeting physical activity guidelines each week during the coronavirus period identified in the elicitation study were rated for the extent to which they would interfere with behaviour (e.g. ‘How much would each of the following interfere with your ability to meet the physical activity guidelines each week during the coronavirus period - Lack of time to exercise’, scored 1 = Not at all to 7 = Extremely). A control belief composite was created using responses to the two control-related items that significantly correlated with its relevant TPB construct of perceived behavioural control.

Attitude

Attitude towards meeting physical activity guidelines each week during the coronavirus period was assessed by averaging responses to five bipolar adjective scales, each with the common stem ‘Meeting the physical activity guidelines each week during the coronavirus period would be…’ followed by adjective pairings on a 7-point scale (e.g. 1 = Bad to 7 = Good).

Subjective norm

Subjective norm towards meeting physical activity guidelines each week during the coronavirus period was assessed by averaging degree of agreement with four items (e.g. ‘Most people who are important to me would approve of me meeting the physical activity guidelines each week during the coronavirus period’), each scored 1 = Strongly Disagree to 7 = Strongly Agree.

Perceived behavioural control

Perceived behavioural control over meeting physical activity guidelines each week during the coronavirus period was assessed by averaging degree of agreement with four items (e.g. ‘It is mostly up to me whether I meet the physical activity guidelines each week during the coronavirus period’), scored 1 = Strongly Disagree to 7 = Strongly Agree.

Motivation

Participants’ motivation towards meeting physical activity guidelines each week during the coronavirus period was assessed by averaging responses to four items (e.g. ‘How motivated are you to meet the physical activity guidelines each week during the coronavirus period?’), scored 1 = Not at all to 7 = Very much.

Intention

Intention to meet physical activity guidelines each week during the coronavirus period was assessed by averaging degree of agreement with four items (e.g. ‘I intend to meet the physical activity guidelines each week during the coronavirus period’), scored 1 = Strongly Disagree to 7 = Strongly Agree.

Physical activity

Physical activity was measured at Time 2. The measure asked about participants performance in meeting the physical activity guidelines in the previous two weeks and was assessed using the mean of three items (e.g. ‘In the past two weeks, I met the physical activity guidelines each week?’), scored 1 = False to 7 = True.

ResultsFootnote1

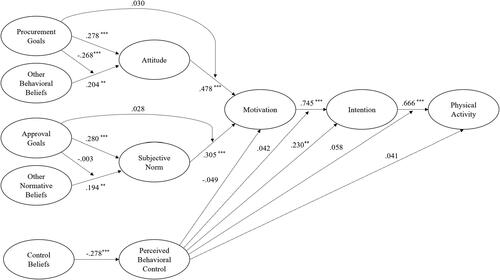

The analysis was run as a linear PLS-SEM model in WarpPLS 7.0 (Kock, Citation2018), as this method is especially robust in small samples compared with other SEM procedures using Maximum likelihood estimation (Dijkstra & Henseler, Citation2015). Standard errors were calculated using the stable method (Kock, Citation2014). Scale items were used to form latent variables for each of the constructs used (see Supplemental Material, Appendix A for loadings). Goal and belief constructs were set as formative latent variables (Bollen & Diamantopoulos, Citation2017), while all other constructs were reflective latent variables. Only beliefs that significantly correlated with their relevant TPB construct were included in the beliefs latent variables. The model displayed good fit-to-data (GoF = .562, RSCR = .989), and predicted 38% of the variance in motivation, 74% of the variance in intention, and 48% of the variance in physical activity. All parameter statistics are presented in .

Table 3. Parameter estimates from the model predicting physical activity during the COVID-19 period using the theory of reasoned goal pursuit.

Next, we examined predictions derived from the theory of reasoned goal pursuit. In support of H1, attitude was positively predicted by behavioural beliefs, but, importantly, beliefs corresponding to procurement goal beliefs were more strongly related to attitude than other behavioural beliefs. Further, procurement goal beliefs negatively moderated the effects of other behavioural beliefs on attitudes. To further investigate this interaction, a simple slopes analysis with a median split was conducted, indicating the effect of other behavioural beliefs was stronger when the elicited procurement goal beliefs were not endorsed (βBelow Median Goal Endorsement = .51, p < .001; β Above Median Goal Endorsement = .18, p = .188). Procurement goal beliefs had a significant indirect effect on behaviour through attitude, motivation, and intention. Supporting H2, subjective norm was predicted by normative beliefs, and, again in support of the TRGP, beliefs corresponding to approval goal beliefs were more strongly related to subjective norm than other normative beliefs. As hypothesised, control beliefs predicted perceived behavioural control (H3). In support of H4, attitude and subjective norm predicted motivation to meet the physical activity guidelines. Further, attitude and subjective norm had a significant indirect effect on behaviour through motivation and intention. As expected, motivation was a significant predictor of intention to meet the physical activity guidelines (H5a) and intention significantly predicted prospectively measured physical activity behaviour (H6b). Further, motivation had a significant indirect effect on behaviour through intention. However, in contrast to predictions, perceived behavioural control did not moderate the motivation-intention (H5b) or intention-behaviour (H6b) relations. Perceived behavioural control also did not predict motivation or physical activity behaviour but it did predict intention and physical activity behaviour indirectly through intention. Finally, we explored the possibility that behavioural beliefs corresponding to procurement goal beliefs may moderate the attitude to motivation path, and that normative beliefs corresponding to approval goal beliefs may moderate the subjective norm to motivation path. In contrast to expectations, no other moderation effects met the conventional significance threshold of 0.05; however, all tested moderations were in the expected direction. See for a graphical depiction.

Discussion

In a first empirical test of the TRGP (Ajzen & Kruglanski, Citation2019), the present study was designed to identify the modifiable predictors of university students’ physical activity during the COVID-19 pandemic. A linear PLS-SEM model generally supported the hypothesised pattern of effects among theory constructs, explaining a good proportion of the variance in motivation (38%), intention (78%), and physical activity behaviour (48%).

A central tenet of the TRGP is the proposition that beliefs corresponding to procurement goals (i.e. beliefs concerning outcomes a person may be motivated to attain by performing physical activity) and beliefs corresponding to approval goals (i.e. beliefs concerning the approval from significant others the person may seek by performing physical activity) are more consequential to people’s motivation and, thus, their intentions and behaviour, than other behavioural and normative beliefs, respectively. Consistent with these expectations, the present study found that beliefs corresponding to active procurement goal beliefs and active approval goal beliefs were more strongly related to attitude and subjective norm than other behavioural beliefs and normative beliefs, respectively. However, also consistent with expectations, the other behavioural beliefs to attitude path was moderated by active procurement goals, indicating that when individuals endorse the most commonly held active procurement goals, the effect of other behavioural beliefs on attitude is weakened. Furthermore, we found active beliefs corresponding to procurement goals indirectly predicted behaviour by way of attitude, motivation, and intention whereas other behavioural beliefs did not. These findings support the propositions of the TRGP in that people are more likely to be guided by their attitudes and subjective norms, and thus be more motivated to perform a given behaviour, if they perceive the behaviour as promoting the attainment of their procurement and/or approval goals.

We also explored the possibility that beliefs corresponding to active procurement goals moderate the attitude to motivation path, and that beliefs corresponding to active approval goals moderate the subjective norm to motivation path. This was based on the notion that the effects of attitude and subjective norm on motivation may be stronger when the behaviour is perceived to serve the attainment of active procurement and approval goal beliefs, respectively. However, although the observed moderating effects were in the expected positive direction, they were not statistically significant. Further research is needed to explore the possibility that stronger moderation by goal-relevant beliefs may emerge with respect to different kinds of behaviour or in different contexts.

Present findings also showed that attitude and subjective norm predicted motivation to meet the physical activity guidelines, and indirectly predicted behaviour through motivation and intention, as posited by the TRGP. Further, although not specified by the TRGP, yet as has been widely tested and observed in the literature (Armitage & Conner, Citation2001; McEachan et al., Citation2011), perceived behavioural control did not predict motivation or physical activity behaviour directly but did predict intention, and thus it predicted physical activity behaviour indirectly through intention. In addition, and as proposed by the TRGP, motivation was a significant predictor of intention to meet the physical activity guidelines and intention significantly predicted prospectively measured physical activity behaviour, with a significant motivation-intention- behaviour relationship observed.

These findings indicate that commonly observed social cognition constructs that predict performance of physical activity behaviour in general (e.g. attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavioural control, motivation; Armitage & Conner, Citation2001; McEachan et al., Citation2011; Teixeira et al., Citation2012) also predict physical activity behaviour in times of extreme uncertainty and change, such as in a pandemic. The mediation effects observed indicate that interventions targeting change in the determinants of intention are likely to have a concomitant effect on behaviour, as demonstrated in recent experimental evidence (Sheeran et al., Citation2016). This knowledge provides guidance to interventionists as to which specific behaviour change techniques to adopt (Abraham & Michie, Citation2008), thus facilitating the development of interventions that are based on theory and that provide an empirically validated foundation for effective design and implementation. For example, information provision, persuasive communication, or cognitive dissonance techniques could be used to change attitudes; subjective norms could be changed using techniques such as highlighting others’ approval and mobilising social support; and providing mastery and vicarious experiences and environmental restructuring techniques could be used to change perceived behavioural control (Hamilton & Johnson, Citation2020; Warner & French, Citation2020). Further, beyond common social-cognitive intervention strategies, the effect of procurement and approval goals on social cognition beliefs may flag the potential for goal system targeted behaviour change techniques to supplement the aforementioned social-cognitive based strategies. For example, using theory-based goal setting strategies to promote strong procurement goals which may in turn influence attitude (Kruglanski et al., Citation2002).

Finally, and in contrast to predictions and the propositions of the TRGP, perceived behavioural control did not moderate the motivation-intention or intention-behaviour relations. Research investigating the effects of perceived behavioural control has tended to focus on its direct effects and indirect effects (via intention) on behaviour, with broad meta-analytic support for these pathways (Armitage & Conner, Citation2001; McEachan et al., Citation2011), particularly the perceived behavioural control-intention link, including in the present study. Emerging research, however, has started to refocus its efforts on testing the moderation of the intention-behaviour relation by perceived behavioural control, and a recent meta-analysis (Hagger et al., Citation2022) provided evidence to support this effect, suggesting that when perceived control over a behaviour is compromised, individuals are less likely to act on their intentions. Given the present study did not find this effect, it is suggested that further research explore the conditions under which the moderating effect of perceived behavioural control is likely to be observed.

Study limitations and avenues for future research

Despite this study being the first test of the TRGP, it is, nevertheless, important to consider some limitations when interpreting its findings. First, the study was conducted on one behaviour, on a selective sample of university students, and in the context of a pandemic. Nevertheless, although the present findings may not be generalisable to other behaviours, samples, and contexts they provide formative evidence for the TRGP. Second, the current study was correlational in design, so reported effects reflect prediction and causal effects in the model are inferred from theory alone not the data. Future research adopting cross-lagged panel, experimental, or intervention designs is required in order to permit more severe tests of causal relations. Third, it is important to note that a self-report measure of behaviour was used. Although similar brief measures addressing the extent to which individuals believe they have met physical activity goals or guidelines have demonstrated good correspondence with objective measures (Hamilton et al., Citation2012; Innerd et al., Citation2015), self-reports of behaviour involve an increased risk of recall bias and socially desirable responding. Fourth, as in the vast majority of studies relying on the TPB, the elicitation process to identify the most salient goals and beliefs in the present study used group rather than individual data (i.e. modal accessible goals and beliefs). This may have resulted in the most readily accessible goals identified for analysis on the group level not being accurate for everyone. It should be noted that the most common response to approval goals in the elicitation study was ‘I don’t seek approval’. Given that most people denied having approval goals, other methods and questioning techniques to identify approval goals may be needed. Finally, while the results of the current study generally support the TRGP, it is important to note that the modest sample size used precluded detailed model comparisons. Thus, the current study provides little evidence in regard to the extent to which the TRGP improves upon the TPB on which it is largely based. Future research may seek to test the TRGP in larger sample sizes with the express goal of conducting model comparison tests.

Conclusion

The current study is the first empirical test of the TRGP, providing valuable formative evidence in support of model predictions. Results lend support for the majority of predictions in the model and also provide some indication of the processes by which the model’s theoretical constructs relate to behaviour. Importantly, we found that behavioural and normative beliefs corresponding to procurement and approval goals, respectively, correlated more strongly with attitude and subjective norm than other behavioural and normative beliefs. These findings support the important role played by goals in the context of reasoned action models. The TRGP was tested in the context of predicting physical activity behaviour among Australian undergraduate students during the COVID-19 shutdown period. Study findings set the agenda for future research to systematically test the proposed direct, indirect, and moderation effects for different health behaviours, populations, and contexts. This will facilitate the gathering of sufficient data to enable future research syntheses of the TRGP and its proposed effects, as has been done for other well-known social cognitions models such as the TPB.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (21.3 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors. Peer review of this article was handled by former Co-Editor-in-Chief, Professor Mark Conner, independent of the current Co-Editors in Chief and Associate Editors of Psychology and Health.

Funding

The author(s) reported there is no funding associated with the work featured in this article.

Notes

1 A statistical analysis of the theory of planned behavior is available for comparison in the online supplementary materials at https://osf.io/sf8mw/. See Supplemental Material, Appendix C and Supplemental Material, Table 1.

References

- Abraham, C., & Michie, S. (2008). A taxonomy of behavior change techniques used in interventions. Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 27(3), 379–387. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.27.3.379

- Ajzen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In J. Kuhl & J. Beckmann (Eds.), Action control (pp. 11–39). Springer.

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Ajzen, I. (2006). Constructing a theory of planned behavior questionnaire.

- Ajzen, I. (2012). The theory of planned behaviour. In P. A. M. van Lange, A. W. Kruglanski, & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of theories of social psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 438–459). Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446249215

- Ajzen, I., & Kruglanski, A. W. (2019). Reasoned action in the service of goal pursuit. Psychological Review, 126(5), 774–786. https://doi.org/10.1037/rev0000155

- Ajzen, I., & Schmidt, P. (2020). Changing behaviour using the theory of planned behavior. In M. S. Hagger, L. D. Cameron, K. Hamilton, N. Hankonen, & T. Lintunen (Eds.), Handbook of behavior change (pp. 17–31). Cambridge University Press.

- Armitage, C. J., & Conner, M. (2001). Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analytic review. The British Journal of Social Psychology, 40(Pt 4), 471–499. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466601164939

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2020). Behaviours & risk factors: Insufficient physical activity. AIHW.

- Bollen, K. A., & Diamantopoulos, A. (2017). In defense of causal-formative indicators: A minority report. Psychological Methods, 22(3), 581–596. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000056

- Bull, F. C., Al-Ansari, S. S., Biddle, S., Borodulin, K., Buman, M. P., Cardon, G., Carty, C., Chaput, J.-P., Chastin, S., Chou, R., Dempsey, P. C., DiPietro, L., Ekelund, U., Firth, J., Friedenreich, C. M., Garcia, L., Gichu, M., Jago, R., Katzmarzyk, P. T., … Willumsen, J. F. (2020). World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 54(24), 1451–1462. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2020-102955

- Caputo, E. L., & Reichert, F. F. (2020). Studies of physical activity and COVID-19 during the pandemic: A scoping review. Journal of Physical Activity & Health, 17(12), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2020-0406

- Chin, W. W. (2010). How to write up and report PLS analyses. In V. E. Vinzi, W. W. Chin, J. Henseler, & H. Wang (Eds.), Handbook of partial least squares (pp. 655–690). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-32827-8_29

- Dijkstra, T. K., & Henseler, J. (2015). Consistent partial least squares path modeling. MIS Quarterly, 39(2), 297–316. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2015/39.2.02

- Dwyer, M. J., Pasini, M., De Dominicis, S., & Righi, E. (2020). Physical activity: Benefits and challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 30(7), 1291–1294. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.13710

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (2010). Predicting and changing behavior: The reasoned action approach. Psychology Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203838020

- Gostin, L. O., & Wiley, L. F. (2020). Governmental public health powers during the COVID-19 pandemic: Stay-at-home orders, business closures, and travel restrictions. JAMA, 323(21), 2137–2138. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.5460

- Gozzi, N., Bajardi, P., & Perra, N. (2021). The importance of non-pharmaceutical interventions during the COVID-19 vaccine rollout. PLOS Computational Biology, 17(9). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009346

- Guthold, R., Stevens, G. A., Riley, L. M., & Bull, F. C. (2018). Worldwide trends in insufficient physical activity from 2001 to 2016: A pooled analysis of 358 population-based surveys with 1·9 million participants. The Lancet Global Health, 6(10), e1077–e1086. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30357-7

- Guthold, R., Stevens, G. A., Riley, L. M., & Bull, F. C. (2020). Global trends in insufficient physical activity among adolescents: A pooled analysis of 298 population-based surveys with 1·6 million participants. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 4(1), 23–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30323-2

- Hagger, M. S., Cheung, M., Aizen, I., & Hamilton, K. (2022). Perceived behavioral control moderating effects in the theory of planned behavior: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0001153

- Hagger, M. S., & Hamilton, K. (2020). Changing behaviour using integrated theories. In M. S. Hagger, L. D. Cameron, K. Hamilton, N. Hankonen, & T. Lintunen (Eds.), The handbook of behavior change (pp. 208–224). Cambridge University Press.

- Hale, T., Petherick, A., Phillips, T., & Webster, S. (2020). Variation in government responses to COVID-19. Blavatnik School of Government Working Paper, 31, 2020–2011.

- Hall, G., Laddu, D. R., Phillips, S. A., Lavie, C. J., & Arena, R. (2021). A tale of two pandemics: How will COVID-19 and global trends in physical inactivity and sedentary behavior affect one another? Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases, 64, 108–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2020.04.005

- Hamilton, K., & Johnson, B. T. (2020). Attitude and persuasive communication interventions. In M. S. Hagger, L. D. Cameron, K. Hamilton, N. Hankonen, & T. Lintunen (Eds.), Handbook of behavior change (pp. 445–460). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108677318.031

- Hamilton, K., van Dongen, A., & Hagger, M. S. (2020). An extended theory of planned behavior for parent-for-child health behaviors: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology, 39(10), 863–878. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000940

- Hamilton, K., White, K. M., & Cuddihy, T. (2012). Using a single-item physical activity measure to describe and validate parents’ physical activity patterns. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 83(2), 340–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2012.10599865

- Hukkelberg, S. S., Hagtvet, K. A., & Kovac, V. B. (2014). Latent interaction effects in the theory of planned behaviour applied to quitting smoking. British Journal of Health Psychology, 19(1), 83–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12034

- Innerd, P., Catt, M., Collerton, J., Davies, K., Trenell, M., Kirkwood, T. B. L., & Jagger, C. (2015). A comparison of subjective and objective measures of physical activity from the Newcastle 85+ study. Age and Ageing, 44(4), 691–694. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afv062

- Irwin, J. D. (2004). Prevalence of university students’ sufficient physical activity: a systematic review. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 98(3 Pt 1), 927–943. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.98.3.927-943

- Kock, N. (2014). Stable P value calculation methods in PLS-SEM. ScriptWarp Systems.

- Kock, N. (2018). WarpPLS user manual: Version 6.0. ScriptWarp Systems.

- Kohl, H. W., Craig, C. L., Lambert, E. V., Inoue, S., Alkandari, J. R., Leetongin, G., & Kahlmeier, S. (2012). The pandemic of physical inactivity: Global action for public health. The Lancet, 380(9838), 294–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60898-8

- Kothe, E. J., & Mullan, B. A. (2015). Interaction effects in the theory of planned behaviour: Predicting fruit and vegetable consumption in three prospective cohorts. British Journal of Health Psychology, 20(3), 549–562. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12115

- Kruglanski, A. W., Shah, J. Y., Fishbach, A., Friedman, R., Chun, W. Y., & Sleeth-Keppler, D. (2002). A theory of goal systems. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 34, pp. 331–378). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(02)80008-9

- La Barbera, F., & Ajzen, I. (2020). Control interactions in the theory of planned behavior: Rethinking the role of subjective norm. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 16(3), 401–417. https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.v16i3.2056

- La Barbera, F., & Ajzen, I. (2021). Moderating role of perceived behavioral control in the theory of planned behavior: A preregistered study. Journal of Theoretical Social Psychology, 5(1), 35–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts5.83

- Lee, I.-M., Shiroma, E. J., Lobelo, F., Puska, P., Blair, S. N., & Katzmarzyk, P. T. (2012). Impact of physical inactivity on the world’s major non-communicable diseases. The Lancet, 380(9838), 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61031-9

- López-Valenciano, A., Suárez-Iglesias, D., Sanchez-Lastra, M. A., & Ayan, C. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on university students’ physical activity levels: An early systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 3787.

- McEachan, R. R. C., Conner, M., Taylor, N. J., & Lawton, R. J. (2011). Prospective prediction of health-related behaviours with the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology Review, 5(2), 97–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2010.521684

- Okazaki, K., Suzuki, K., Sakamoto, Y., & Sasaki, K. (2015). Physical activity and sedentary behavior among children and adolescents living in an area affected by the 2011 Great East Japan earthquake and tsunami for 3 years. Preventive Medicine Reports, 2, 720–724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2015.08.010

- Rich, A., Brandes, K., Mullan, B., & Hagger, M. S. (2015). Theory of planned behavior and adherence in chronic illness: A meta-analysis. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 38(4), 673–688. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-015-9644-3

- Rubin, G. J., Brainard, J., Hunter, P., & Michie, S. (2021). Are people letting down their guard too soon after covid-19 vaccination? British Medical Journal (BMJ). https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2021/03/18/are-people-letting-down-their-guard-too-soon-after-covid-19-vaccination/

- Sheeran, P., Maki, A., Montanaro, E., Avishai-Yitshak, A., Bryan, A., Klein, W. M. P., Miles, E., & Rothman, A. J. (2016). The impact of changing attitudes, norms, and self-efficacy on health-related intentions and behavior: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 35(11), 1178–1188. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000387

- Stockwell, S., Trott, M., Tully, M., Shin, J., Barnett, Y., Butler, L., McDermott, D., Schuch, F., & Smith, L. (2021). Changes in physical activity and sedentary behaviours from before to during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown: A systematic review. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine, 7(1), e000960. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsem-2020-000960

- Teixeira, P. J., Carraça, E. V., Markland, D., Silva, M. N., & Ryan, R. M. (2012). Exercise, physical activity, and self-determination theory: A systematic review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 9(1), 78. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-9-78

- Warner, L. M., & French, D. P. (2020). Confidence and self-efficacy interventions. In M. S. Hagger, L. D. Cameron, K. Hamilton, N. Hankonen, & T. Lintunen (Eds.), Handbook of behavior change (pp. 461–478). Cambridge University Press.

- World Health Organization. (2018). Global action plan on physical activity 2018-2030: More active people for a healthier world. WHO.

- Yang-Wallentin, F., Schmidt, P., Davidov, E., & Bamberg, S. (2004). Is there any interaction effect between intention and perceived behavioral control. Methods of Psychological Research Online, 8(2), 127–157. https://doi.org/10.23668/psycharchives.12787

- Yzer, M., & Van Den Putte, B. (2014). Control perceptions moderate attitudinal and normative effects on intention to quit smoking. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors: Journal of the Society of Psychologists in Addictive Behaviors, 28(4), 1153–1161. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037924

- Zhang, Z., & Yuan, K. H. (2018). Practical statistical power analysis using webpower and R. ISDSA Press. https://webpower.psychstat.org