Abstract

Objective

The present research sought to examine whether cohabitation with a smoker undermines smoking cessation among people engaged in a cessation programme and whether the components of the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) act as mediating mechanisms.

Design

A prospective longitudinal study with online questionnaires was conducted among smokers living in Switzerland who enrolled in a 6-months smoking cessation programme.

Main outcome measures

Cohabitation with a smoker and the TPB constructs were assessed 10 days after the start of the programme (T1; N = 820). Smoking abstinence was measured at T1, and at 3-months (T2; N = 624) and 6-months follow-ups (T3; N = 354).

Results

Results showed that living with a smoker decreased the odds that smokers remained abstinent throughout the cessation programme. Furthermore, we found that cohabitation was negatively associated with subjective norm. Afterwards, subjective norm predicted intention to maintain smoking cessation, which, in turn, predicted smoking abstinence. Such mediation effects persisted at each time point.

Conclusion

The present research provided evidence that living with other smokers at home can lead to greater risks of relapsing among people engaged in a cessation programme. We discussed the role of smoking-related norms in the efficacy of cessation interventions.

Supplemental data for this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2022.2041638 .

Despite positive changes in recent years, tobacco consumption is still particularly high in many countries around the world. In 2016, almost a quarter of the Swiss population was still smoking cigarettes on a daily basis, and almost 80% of those who attempted to quit ended up relapsing at least two times before successful smoking cessation (Gmel et al., Citation2017). As a result, smoking cessation interventions remains fundamental practices to encourage smokers to give up and maintain quit attempts. However, ranging from pharmacological (e.g. nicotine replacement therapies) to psychological interventions (e.g. counselling-based interventions or cognitive behavioural therapies), cessation interventions result in varying quit rates and are far from being consistently successful (Fisher et al., Citation1993; Mottillo et al., Citation2009). Therefore, research is needed to identify the different factors that can degrade the effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions. In the present study, we focused our attention on smokers' living conditions, and more particularly, on the role played by cohabitation with a smoker in the success of a smoking cessation programme.

Living with a smoker and smoking cessation

Friends, family members, fellow workers, or anyone with whom one shares particular ties, exert considerable influence on health behaviours. This is also the case regarding tobacco consumption. Smoking is a socially contagious behaviour and smokers often mimic their closest friends and relatives in starting smoking when they start or in quitting when they decide to quit. In line with this, research has extensively shown that smokers' entourage plays a decisive role in smoking initiation, maintenance, and cessation (Christakis & Fowler, Citation2008; Takagi et al., Citation2020). Peer influence has been pointed out as one of the major causes of smoking initiation and continuation among adolescents (Liu et al., Citation2017). As a consequence, quitting smoking may be a significant challenge when one's important others still continue smoking.

In this perspective, cohabitation with a smoker has been shown to be an important barrier to smoking cessation that contributes significantly to maintaining tobacco use (e.g. Li et al., Citation2019; Mueller et al., Citation2007). Numerous studies have found that living with a smoking partner is associated with lower odds of quitting and an increase in relapse (e.g. Britton et al., Citation2019; Jackson et al., Citation2015; Margolis & Wright, Citation2016). However, despite that research has highlighted the deleterious impact of cohabitating with a smoker on quitting behaviours, little attention has been paid to whether this can also undermine the success of cessation interventions. Moreover, little is known about the underlying mechanisms. Thus, the objectives of the present research were to assess whether cohabitation with a smoker could affect abstinence among smokers attending a smoking cessation intervention and whether the constructs of the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB; Ajzen, Citation1991, Citation2020) could play as mediating processes.

The TPB constructs as mediating processes

The TPB proposes that health behaviours are determined by a relatively small number of socio-cognitive constructs that are associated with each other. The most proximal construct of the behaviour is behavioural intention, that is, the expression of a motivation to perform a given behaviour (e.g. quit smoking). Intention is predicted by attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioural control (PBC). In addition, a direct relationship is assumed between PBC and behaviour. Attitude corresponds to the more or less favourable evaluation of a given behaviour. Subjective norm reflects the perception that one's significant others approve or disapprove of a specific behaviour. PBC refers to the belief in being able to enact a behaviour. The TPB has been widely validated across a large number of studies and has been applied to a wide variety of health behaviours (Armitage & Conner, Citation2001; McEachan et al., Citation2011). In particular, this theory has been shown to be relevant in predicting smoking behaviour (Topa & Moriano, Citation2010), as well as the efficacy of cessation interventions (Lareyre et al., Citation2021; Norman et al., Citation1999).

Moreover, the TPB provides a useful framework to account for the psychological mechanisms underlying the effects of environmental variables, such as country of residence, occupation, or income level (Conner & Abraham, Citation2001; Conner & Sparks, Citation2015). Previous studies have shown that the TPB constructs (i.e. attitude, subjective norm, PBC, and intention) serve as mediators to explain the effects of people' environment on behaviour (e.g. Armitage et al., Citation2002; Desrichard et al., Citation2007; Hagger & Hamilton, Citation2021; Nagelhout et al., Citation2012). For example, across 13 independent samples including varied populations and contexts, the recent research by Hagger and Hamilton (Citation2021) provided meta-analytical evidence that the effects of socio-cultural variables (i.e. gender, age, and education) on health behaviours (e.g. dental flossing, drinking behaviour, sun safety) were mediated by the constructs of the TPB. In a 4-years longitudinal study, Nagelhout et al. (Citation2012) demonstrated that individual exposure to smoke-free legislation was related to quit attempt and quit success through attitude, subjective norm, and intention to quit. PBC was not found to be a mediator but still predicted directly smoking cessation.

Similarly, we believe that cohabitating with a smoker can undermine the success of smoking cessation interventions through the TPB constructs. Indeed, we hypothesize that living in such an environment is likely to generate:

A negative evaluation of smoking cessation (attitude). Given that smoking behaviours are related to a positive opinion toward smoking (de Leeuw et al., Citation2008; Mohammadi et al., Citation2017), one may think that cohabitation with a smoker implies living with someone holding, and supposedly conveying, positive views on smoking on a daily basis. Undoubtedly, this may shape smokers' own regard toward tobacco use and contribute to nurturing a negative attitude toward quitting. Relatedly, McGee et al. (Citation2015) have shown that 9–10-year-old children with smoking family and friends were less likely to believe that smoking is bad for health, compared with children being surrounded by a non-smoking entourage.

A perception that one's significant others disapprove of smoking cessation (subjective norm). Sharing one's everyday life with a smoker can fuel the idea that smoking cessation is not appropriate or desirable. Moreover, this can deprive of essential psychological resources in managing a quit attempt, such as encouragement and social support (Lüscher et al., Citation2017). This can also remove an important source of social control, resulting in reduced social pressure and sanctions on quitters to maintain their efforts in refraining from smoking (see Scholz et al., Citation2013; Westmaas et al., Citation2002).

A perception of being incapable to quit and/or maintain smoking cessation (PBC). Living with people continuing smoking can make quitters perceive that resistance to cigarette cravings and management of withdrawal symptoms would require increased efforts, thereby reducing their perceived abilities in quitting. Research has shown that smokers whose partner is also a smoker have a lower perception of self-efficacy in quitting and are then more likely to start smoking again (Jackson et al., Citation2015; Warner et al., Citation2018).

In line with TPB research (e.g. Lareyre et al., Citation2021; Topa & Moriano, Citation2010), attitude, subjective norm, and PBC should predict in turn reduced willingness to maintain smoking cessation (behavioural intention), which, finally, should increase the risks of relapsing (behaviour).

Overview of the study

The current study pursued three main objectives: (1) to examine whether and how much cohabiting with a smoker affects the likelihood that smokers who are engaged in a smoking cessation programme can maintain abstinence until the end of it; (2) to test whether the TPB constructs can account for the effects of cohabitation; (3) to investigate whether and how living with a smoker and the TPB components together predict smoking abstinence across time, over the course of a long-term cessation intervention.

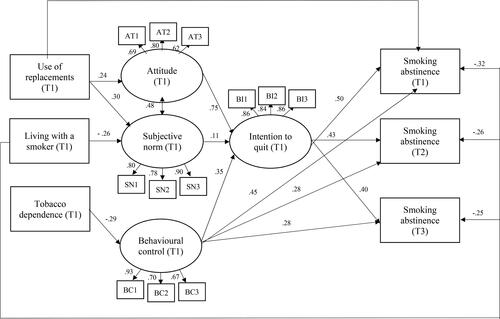

We hypothesized a model in which living with a smoker would negatively affect smoking abstinence, attitude, subjective norm, and PBC. In turn, we expected attitude, subjective norm, and PBC to predict behavioural intention, which itself would be associated with smoking abstinence. In line with the theoretical assumptions of the TPB, a direct path from PBC to smoking abstinence was also hypothesized. Moreover, we expected indirect paths from the cohabitation variable to intention through attitude, subjective norm, and PBC, while intention was hypothesized to mediate the effects of attitude, subjective norm, and PBC on smoking abstinence. An indirect effect of the cohabitation variable on smoking abstinence via PBC was also anticipated. Finally, we hypothesized serial mediation effects starting from cohabitation to abstinence through first attitude, subjective norm, and PBC (first path), and second through intention (second path). Our conceptual model was examined with smoking abstinence assessed at three-time points over the course of a 6-months smoking cessation program (i.e. 10 days after the start date, three months after the start date, and at the end). Tobacco dependence and use of nicotine replacements were both controlled.

Method

We conducted a prospective longitudinal study on a large sample of daily smokers who participated in the 'I quit smoking on Facebook' (IQSF) intervention. Built on the UK Stoptober campaign, IQSF was an online national-level cessation intervention, delivered through Facebook in Switzerland. The purpose of the campaign was to engage smokers who had the desire to quit in a collective quit attempt for six months from the 21st March 2017. To be considered participants, the volunteers had to subscribe and like the IQSF Facebook page and post a welcome comment. The intervention was advertised in Switzerland for two months before being officially launched. In total, 7008 smokers participated in the intervention. Over six months, all participants were provided with daily support messages and tips, designed by medical and tobacco experts, on how to manage withdrawal symptoms. They received free access to personally phone counselling, in addition to support and advice from other participants. They were also encouraged to post comments and share their feelings and difficulties in quitting. Success rates and further details concerning this intervention may be found in Desrichard et al. (Citation2021).

Participants and procedure

The procedure took place in different stages:

Two days before the start of the campaign, we disseminated a recruitment message via the Facebook list of the IQSF intervention's participants. In this message, we notified that volunteers were sought to participate in a study aimed at evaluating the efficacy of IQSF and understanding what may predict its success. They were told that participation in the study involved responding to an online questionnaire several times throughout the intervention. To reduce attrition, they were informed that completion of questionnaires at every follow-up would enter them into a prize draw to win CHF1,000 (≈ 930€), regardless of whether they ended up being abstinent or not. Our inclusion criteria were as follows: participants were included 1) if they were smokers before the start date and 2) if they had stopped smoking on the day the programme started. Therefore, we excluded those who were already abstinent before the day the intervention started and those who did not even try quitting at all. In total, 820 smokers were retained in our final sample.

Ten days after the start of the intervention (T1),Footnote1 participants were requested to complete the first questionnaire, assessing whether they were sharing their home with a smoker, attitude, subjective norm, PBC, and intention to quit. We also measured smoking abstinence, tobacco dependence, and use of nicotine replacements.Footnote2

Afterwards, participants were monitored for 6 months and asked to report whether they were still abstinent at two more time points after the start of the intervention: 3 months later (T2; N = 624) and 6 months later (T3: N = 354).Footnote3

Measures

The measures of attitude, subjective norm, PBC, and intention were adapted from Fishbein and Ajzen (Citation2010) and were answered on 7-points rating scales unless otherwise mentioned. The following possible answer was additionally provided for each item: 'I don't know' (coded as missing data when chosen). Following Little et al. (Citation2002)'s recommendations for structural equation modelling (SEM), we measured each latent factor with three observed indicators.

Cohabitation with a smoker

Participants were asked whether they were currently living with a smoker at home. Answers were 'yes' or 'no'.

Attitude

This construct was measured by three items: 'Refraining from smoking for the next 6 months is: very bad thing-very good thing'; 'Refraining from smoking for the next 6 months is: not important-very important'; 'I think that refraining from smoking for the next 6 months is: very useless-very useful' (α = .72).

Subjective norm

Subjective norm was assessed using three items: 'Most of the people for whom opinion is important to me wish I could stop for the next 6 months'; 'My family and friends think it is important that I refrain from smoking for the next 6 months'; 'People for whom opinion matters to me agree that I refrain from smoking for the next 6 months' (α = .86). Answers were given on a scale ranging from 'Not agree' to 'Totally agree'.

PBC

We measured PBC with three items: 'Refraining from smoking in the next 6 months is: very difficult-very easy'; 'Refraining from smoking in the next 6 months is: not much constraining-much constraining' (reverse-coded); 'Refraining from smoking in the 6 months requires efforts that are: not much important-very important' (reverse-coded; α = .81).

Intention

We used three items to measure intention: 'I feel motivated to refrain from smoking in the next 6 months'; 'I am ready to make efforts in refraining from smoking in the next 6 months'; 'My intention is to refrain from smoking in the next 6 months'. Answers were given on a scale ranging from 'Not agree' to 'Totally agree' (α = .87).

Smoking abstinence

At each follow-up, participants were asked to choose between the five following answers: 'I'm still not smoking', 'I'm still trying to quit completely, but sometimes I smoke', 'I gave up quitting, but I use less tobacco than before', 'I gave up quitting and I smoke as much as before', and 'I gave up quitting and I smoke more than before'. We considered participants as abstainers (coded +1) only if they had reported having not smoked since the intervention had started. This question was asked three times after the programme start: 10 days later (T1), 3-months later (T2) and 6-months later (T3; i.e. the end of the intervention).

Additional outcomes

We assessed tobacco dependence (at T1) using the Fagerström Test for Cigarette Dependence (FTCD; Fagerström, Citation2012; M = 4.48, SD = 2.20). We also asked participants (at T1) whether they had been using nicotine replacements (e.g. e-cigarettes, nicotine patches) during the program. Answers were either 'I have never used some', 'I used some at first but I have stopped', 'I'm still using some, but I'm going to stop' or 'I'm still using some and I'm going to continue'. We considered as replacement users (coded +1) all participants who selected one of the three last answers. In addition, we collected background demographic data, such as age, sex, professional status, household annual income, and educational degree.

Analytical strategy

In a first step, we conducted logistic regressions to examine whether and how much cohabitation with a smoker affects the probability to maintain abstinence in the course of the cessation programme. In a second step, we assessed the measurement model with four latent factors using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), and then used SEM with observed indicators and latent factors to estimate both direct and indirect effects of our serial mediation model.Footnote4 Attitude, subjective norm, PBC, and intention were latent factors, while other variables were observed indicators. We analysed our model by including smoking abstinence as an outcome measured at each time point (i.e. T1 to T3) and compared direct and indirect relationships between the variables predicting abstinence across time. We controlled for tobacco dependence and use of nicotine replacements. We run all analyses using the Mplus software version 8.4. Model fit was assessed using multiple indices and following the Hu and Bentler (Citation1999) cutoff criteria: Comparative Fit Index (CFI) > 0.95, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) < 0.06, and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (sRMR) < 0.08. We also reported the Chi-square test but did not use it to estimate the model fit due to its well-known limitations, notably its sensitivity to sample size (Brown, Citation2015). Comparisons between nested models were however made using χ2, considering that a significant Δχ2 indicates that the less restrictive model has a better fit to the data. Missing data were treated differently as a function of analyses. Regarding logistic regressions and CFA, we handled missing data using maximum likelihood estimation. Regarding SEM, missing data were handled with pairwise deletion and missingness was treated as a function of the observed covariates and not of the observed outcomes.

Results

Sample characteristics

Among participants included at T1, there were 577 women and 202 men (41 did not report gender). Mean age was 37.00 (SD = 11.25), ranging from 16 to 69. Regarding professional status, 60.5% were employed, while the remainder was either unemployed, retired, or students. A bit less than 30% of participants had a college degree, while more than 45% had less than a high school degree. A great majority of participants (56%) used to smoke 10 to 19 cigarettes per day. On average, participants had started smoking when they were 17.16 years old (SD = 4.30). There were 193 participants who used nicotine replacements during the program (23.5%). Three hundred and six participants (37.3%) declared living with a smoker at home. At T1, 51.3% of participants were still abstainers, while abstinence rate dropped to 16.2% at T3. shows further details about our sample, while descriptive statistics (i.e. means and standard deviations) and correlations between the variables are presented in .

Table 1. Sample characteristics.

Table 2. Means, standard deviations, and correlations.

Logistic regressions

We performed a series of multiple logistic regressions to examine the impact of cohabitation with a smoker (coded as: 1 = yes, 0 = no) on smoking abstinence at each time point in the course of the programme (coded as: 1 = abstinent, 0 = non-abstinent). In complement, tobacco dependence and use of nicotine replacements were controlled. Results showed significant negative effects of cohabitation on smoking abstinence at Time 1, B = −.587, SE = .184, p = .001, 95% CI [-.890, −.285], Time 2, B = −.474, SE = .199, p = .017, 95% CI [-.801, −.148], and Time 3, B = −.443, SE = .235, p = .059, 95% CI [-.829, −.056], showing, as a whole, that smokers were less likely to remain abstinent (vs. not) as they cohabitated with other smokers. More specifically, there was a 44% decrease in the odds that smokers remained abstinent at T1 when they used to live with other smokers (OR = .56, SE = .102, 95% CI [.387, .797]. This percentage of decrease was 38% with abstinence measured at T2, (OR = .62, SE = .124, 95% CI [.422, .918]), and 36% when measured at T3 (OR = .64, SE = .151, 95% CI [.405, 1.018]. Descriptively, one may conclude that the likelihood that the attendees relapsed because of the presence of smokers at home was stronger at the beginning of the programme and slightly decreased as it progressed.

Measurement model

We conducted a CFA with maximum likelihood estimation to examine the factorial structure of latent variables (i.e. attitude, subjective norm, PBC, and intention). We tested a measurement model where observed indicators loaded only onto their corresponding latent factors. This model showed good fit to the data: χ2 (48) = 155.399, p < .001; RMSEA = .055 (90% CI [.046 − .065]); SRMR = .040; CFI = .97. All indicators loaded significantly onto their respective latent factors (almost all the standardized factor loadings were above .70 and significant).

Structural equation modelling

Using these latent factors, we tested a serial mediation model going from the cohabitation variable (i.e. the IV) to smoking abstinence (i.e. the DV) through the TPB constructs (i.e. the mediators). Direct paths were modelled from cohabitation to abstinence, attitude, subjective norm, and PBC, from attitude, subjective norm, and PBC to intention, and from PBC and intention to abstinence. This model was tested once with abstinence for T1, T2, and T3 included in the same analysis. Tobacco dependence (standardized score) and use of nicotine replacements were included as covariates. We also examined indirect effects such as described above. Given that we modelled categorical data, we opted for the WLSMV estimator (see Brown, Citation2015). Details about indirect effects are presented in .

Table 3. Indirect effects of the TPB constructs on smoking abstinence.

We first run the model as aforementioned, but fit indices were only barely acceptable (RMSEA > .10; sRMR = .07; CFI < .87). To improve the global fit, while being parsimonious in re-specification and consistent with our initial predictions, we allowed two latent factors, namely norm and attitude, to intercorrelate freely.Footnote5 Including this correction, indices showed an adequate fit to the data (χ2 (105) = 208.462, p < .001; RMSEA = .044 (90% CI [.035 − .052]); sRMR = .042; CFI = .98).Footnote6

Delving into this model, our results revealed negative effects of cohabitation on subjective norm (β = −.262, p < .005), abstinence at T1 (β = −.320, p < .001), abstinence at T2 (β = −.262, p = .017), and abstinence at T3, although marginally significant (β = −.246, p = .064). Direct effects of cohabitation on attitude and PBC were not significant (all ps > .48). Behavioural intention was significantly predicted by attitude (β = .750, p < .001), subjective norm (β = .111, p = .002), and PBC (β = .347, p < .001). There were also direct effects of PBC and behavioural intention on abstinence at T1 (β = .453, p < .001; β = .497, p < .001, respectively), at T2 (β = .284, p < .001; β = .434, p < .001, respectively), and at T3 (β = .276, p < .001; β = .397, p < .001, respectively). In addition, we found direct effects of tobacco dependence on PBC (β = −.288, p < .001) and marginally significant effects on abstinence at T1 (β = .079, p = .085) and behavioural intention (β = .072, p = .088). Direct effects of replacements use were found on attitude (β = .236, p = .042), subjective norm (β = .301, p = .005), and abstinence at T1 (β = .296, p = .002), and a marginally significant effect on behavioural intention (β = −.135, p = .075). Surprisingly, there was no significant effect on PBC (p > .25). Significant paths are presented in .

Figure 1. Structural equation model.

Note. Only significant paths are presented; Estimates are standardized regression coefficients.

Moreover, we found an indirect effect of subjective norm between cohabitation and intention (β = −.029, p = .033). Indirect effects via attitude and PBC were non-significant (all ps > .48). Behavioural intention was also found to mediate the relationship of attitude, subjective norm, and PBC on abstinence at T1 (β = .373, p < .001; β = .055, p = .004; β = .173, p < .001, respectively), abstinence at T2 (β = .326, p < .001; β = .048, p = .005; β = .151, p < .001, respectively), and abstinence at T3 (β = .298, p < .001; β = .044, p = .007; β = .138, p < .001, respectively). At all the time points, the indirect effects of cohabitation on smoking abstinence through PBC were not significant (all ps > .48). Moreover, the serial mediation effect going from cohabitation to abstinence through first subjective norm and then intention was found significant for all the time points (T1: β = −.014, p = .035; T2: β = −.013, p = .040; T3: β = −.012, p = .044), while those including attitude (all ps > .58) and PBC were not (all ps > .48).

Discussion

The purpose of the present research was to examine whether living with a smoker undermines the capacity to remain abstinent in people engaged in a smoking cessation programme and to evaluate whether the TPB constructs could serve as explanatory mechanisms. Consistent with our hypotheses, the findings revealed that cohabiting with a smoker decreased the likelihood to stay abstinent at all the time points of the cessation programme. Moreover, the analysis of our conceptual model showed that living with a smoker was negatively associated with subjective norm, which in turn was associated with lower intention and then greater relapse. Identical mediation relationships between these variables were observed with abstinence measured at all points in time. Contrary to hypotheses, we found that attitude and PBC were not associated with cohabitation with a smoker and did not explain the effect of this factor on abstinence.

Therefore, subjective norm appears to be the main construct at work in the effects of cohabitation with a smoker on the capacity to remain abstinent among smokers engaged in a cessation programme. In other words, the present findings suggest that living with a smoker undermines the success of smoking cessation programmes mostly because such cohabitation arises the perception that one's significant others do not approve of quitting, which then lowers the intention to refrain from smoking and, ultimately, increases the chances of relapse. Indeed, cohabiting with smokers on a daily basis is likely to create a home environment where smoking remains acceptable and desirable, which may make quitters more prone to start again for fear of not fitting with the environment's collective standards. In this sense, attempting to quit may reflect deviant behaviour that is not approved of by other significant smokers, who may be perceived as pressuring quitters to interrupt programme attendance and thus re-align with peers' expectations. Similarly, smoking cohabitants would be less likely perceived as potential sources to help quitters maintain their quit attempts and cope with smoking cravings. As such, these findings are consistent with the research showing that the perception of an anti-smoking norm in one's close environment leads smokers to greater motivation to quit while a pro-smoking norm produces the opposite effects (e.g. Falomir-Pichastor & Invernizzi, Citation1999; Jackson et al., Citation2020; Schoenaker et al., Citation2018).

Surprisingly, we found that attitude and PBC did not explain the effect of cohabitation. However, attitude and PBC were found to be indirectly predictive of abstinence at all time points of the study. We found that both were associated with abstinence via intention to refrain from smoking. Thus, this shows that these two constructs also account for the effects of smoking abstinence regardless of cohabitation and should equally be considered as central predictors of the efficacy of cessation interventions.

Another surprising result is that the use of nicotine replacements was positively associated with attitude and subjective norm but not with PBC. This suggests that using replacements, which are supposedly designed for giving smokers assistance in quitting and overcoming cravings, did not lead smokers to perceive they have enhanced capacities to quit. We could speculate that those who use such substitutes (vs. those who did not) had initially lower perceived capacities to quit, which is why they turned toward substitutes as a support to maximize their chances of successfully quitting. Given that the TPB variables were measured only 10 days later, one may suspect that replacements users were then equal to non-users in terms of PBC by then. In any case, this is an intriguing issue that would deserve to be further investigated in future research.

Moreover, we found that living with a smoker reduced the odds that smokers are able to maintain their quit attempt from the start to the end of the cessation programme. As a consequence, cohabitation with a smoker increases both immediate and long-term relapse. Similarly, the relationships between the variables examined were persistent in predicting abstinence all along the course of the programme. The same pathway through subjective norm and intention was found with abstinence measured at all times. Nonetheless, it is important to note that the likelihood that cohabitation undermines the success of the cessation programme, as well as the direct and indirect relations between the variables and abstinence, progressively decreased as the programme got closer to the end. We can speculate that the more participants found themselves abstinent over the course of the intervention, the more they were able to control and manage the deleterious effects of cohabitation and maintain smoking cessation.

From a theoretical point of view, our findings contribute to the idea that close entourage, such as one's close friends or relatives, exerts a significant influence on the maintenance of smoking behaviours. More specifically, we add to the extant literature by illuminating the notion that such entourage does not only affect smokers' intention to quit or propensity to actually engage in a quit attempt but also their ability to observe a smoking cessation program. Thus, because they shape what is deemed to be acceptable and desirable to do, people smokers live with are likely to have an impact at all stages of a cessation process and can undermine their chances of quit success, even among those who are highly motivated to quit and monitored by a programme to help them do so. Moreover, although we did not find indirect effects involving attitude and PBC, our findings gave strong support for the validity and usefulness of the TPB in predicting smoking behaviour and the success of cessation programmes, as well as accounting for the socio-cognitive dynamic underlying the effect of environmental factors on behaviour.

One of the major practical implications of our results is to have underscored the importance of smokers' conditions of living in the development of smoking cessation interventions and how cohabitation with a smoker can reduce their success. It is indeed essential to design cessation interventions taking into account that participants presumably live with other smokers on a daily basis while attending the intervention and may have to deal with a pro-smoking climate at home. While it may be difficult to change smokers' environment, it is still possible to address their perceptions of subjective norm. Specific instructions can be given to change these perceptions so that, despite living with a smoker, participants can forge the conviction that their entourage approves and supports their engagement in the intervention and wants them to succeed in quitting. In addition, quitters can be alerted to this difficulty and encouraged to engage smokers to try to quit or to convince them to support their attempt.

Limitations

An important limitation of the present study was the lack of information about the type of relationship that participants had with the smoker(s) they were cohabiting with (e.g. partner, family member, roommate). However, one may reasonably assume that living with a smoking partner, as compared to a smoking roommate, might have varying impacts on the risks of relapse.

Other limitations pertain to the measurement time. First, cohabitation was only assessed at T1, but it remains that changes may have occurred in the course of the intervention, such as the person with whom they were cohabiting have moved out or started quitting as well. Such information will need to be considered and controlled in future studies. Moreover, we did not assess cohabitation and TPB constructs at each follow-up. This would have allowed evaluating the effects of changes in these variables on abstinence and how changes in abstinence can have an impact on the TPB constructs in return. Also, we measured the predicting variables only ten days after the start of the intervention, but it is plausible that participants' responses could have already changed during that time.

Finally, another potential limitation is that we did not cover the variables developed by the extended versions of the TPB. However, over the last few decades, plenty of suggestions have been made to enrich and complement the TPB with new variables, such as past behaviours, anticipated regret, or self-identity (Conner & Armitage, Citation1998; Reid et al., Citation2018). New studies could thus include these variables and test novel explanatory mechanisms. Similarly, sub-dimensions have been proposed for each of the basic TPB variables. For example, whereas subjective norm was traditionally conceptualised as a form of injunctive norm (Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation2010), Ajzen (Citation2020) acknowledged that subjective norm comprised of both injunctive (i.e. what most people approve of) and descriptive norm (i.e. what most people do). Therefore, given that the key mediating factor in our findings was subjective norm, a possible room for future research might be to examine other forms of norms, such as descriptive norms (i.e. the perception that one's significant others have quitted or are in the process of quitting). Finally, there was a lack of information about representativity of our final sample with respect to the programme sample (as we did not have access to the programme data) and perhaps that our sample failed in being fully representative of that sample.

Conclusion

Our research has shown that living with a smoker increases the chances of relapse among smokers who are engaged in a cessation programme. More specifically, we found that maintaining smoking abstinence in the course of a programme becomes more difficult when the participants cohabitated with other smokers. This is partly due to the fact that this fosters the belief that one's closest relatives and friends do not fully approve of engaging in a quit attempt, which in turn diminishes intention to make efforts in refraining from smoking. Attitude toward smoking cessation and beliefs in one's capacity to refrain from smoking are also important factors to predict the efficacy of cessation interventions but do not explain why cohabitation undermines abstinence. Based on these findings, it follows that smoking cessation interventions need to be adapted to take into account attendants' close circle and how this circle can be a brake on the efforts they make into attempting to quit.

Declaration of interest statement

No potential competing interest was reported by the authors.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (17 KB)Data availability statement

All data concerning this research is openly available at https://osf.io/vc8xw

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Given that research has extensively shown that most relapses occur within the first weeks after a quit attempt (Herd et al., Citation2009; Hughes, Citation2007), we had planned to administrate the first questionnaire to participants 10 days after the quit date to evaluate their smoking status at that point. Unfortunately, for practical reasons, we were not able to provide participants with two questionnaires a few days apart and we had then to incorporate the other measures only 10 days later. We acknowledged this limitation in the discussion section.

2 As part of a larger study investigating the psychological predictors underlying the efficacy of online smoking cessation interventions, it is important to note that other variables were assessed in every follow-ups in addition to those described here, the results of which are not reported in the present manuscript (see Desrichard et al., Citation2021; Falomir-Pichastor et al., Citation2020). Also, note that this research has been approved by the ethical committee of the authors' faculty (approval number: PSE.20190304.01).

3 Attrition rate was 23.9% at T2 (n = 196; of them, 51.5% did not cohabitate with a smoker) and 57.9% at T3 (n = 475; of them, 56.6% did not cohabitate with a smoker). At T1, while there was no attrition with respect to smoking abstinence (all the participants responded to the corresponding item), average rates of missing data were 10.7% (n = 88) for attitude, 13% (n = 107) for subjective norm, 11% (n = 90) for PBC, 10.9% (n = 89) for behavioural intention, and 5.4% (n = 44) for dependence. There were 44 missing data (5.4%) on the cohabitation variable and 284 (34.6%) regarding the use of replacements.

4 In the supplementary materials, we provided the results of multi-group CFA and SEM examining whether or not the measurement and structural models are invariant between those who cohabitated with a smoker and those who did not.

5 Based on modification indices, we freely estimated the parameter with the largest and most substantial modification value (MI = 486.27, EPC = .42). Note that this modification remains theoretically sound with the assumptions of the TPB (see Ajzen, Citation2020) and that the difference between the uncorrected and corrected models was significant (Δχ² (1) = 99.19, p < .001).

6 To ensure reliability of this model, we compared it to more restrictive alternative models. In the first alternative model, we constrained the direct paths from cohabitation to attitude and PBC. This model led to a good fit (χ2 (111) = 274.07, p < .001; RMSEA = .053; sRMR = .058; CFI = .96), but significantly differed from our model (Δχ² (6) = 39.048, p < .001). In the second alternative model, the direct paths from cohabitation to attitude, norm, and PBC were constrained. We found a good fit (χ2 (117) = 301.481, p < .001; RMSEA = .055; sRMR = .067; CFI = .96), but a significant difference still appeared with our model (Δχ² (12) = 63.216, p < .001). In a third alternative model, we freely estimated the direct paths from cohabitation to intention and constrained the paths going to abstinence. This model fitted poorly to the data (χ2 (120) = 1309.569, p < .001; RMSEA = .138; sRMR = .164; CFI = .72) and statistically differed from our model (Δχ² (15) = 626.276, p < .001). In sum, these analyses suggested that our model exhibited a better fit in comparison with alternative models and was retained as the most optimal model to explain the data.

References

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Ajzen, I. (2020). The theory of planned behavior: Frequently asked questions. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 2(4), 314–324. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.195

- Armitage, C. J., & Conner, M. (2001). Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analytic review. The British Journal of Social Psychology, 40(Pt 4), 471–499. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466601164939

- Armitage, C. J., Norman, P., & Conner, M. (2002). Can the theory of planned behaviour mediate the effects of age, gender, and multidimensional health locus of control? British Journal of Health Psychology, 7(Part 3), 299–316. https://doi.org/10.1348/135910702760213698

- Britton, M., Haddad, S., & Derrick, J. L. (2019). Perceived partner responsiveness predicts smoking cessation in single-smoker couples. Addictive Behaviors, 88, 122–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.08.026

- Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research (2nd ed.). Guilford.

- Christakis, N. A., & Fowler, J. H. (2008). The collective dynamics of smoking in a large social network. The New England Journal of Medicine, 358(21), 2249–2258. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa0706154

- Conner, M., & Armitage, C. J. (1998). Extending the theory of planned behavior: A review and avenues for further research. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 28(15), 1429–1464. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1998.tb01685.x

- Conner, M., & Sparks, P. (2015). Theory of planned behaviour and the reasoned action approach. In M. Conner & P. Norman (Eds.), Predicting and changing health behaviour: Research and practice with social cognition models (pp. 142–188). Open University Press.

- Conner, M. T., & Abraham, C. (2001). Conscientiousness and the theory of planned behavior: Toward a more complete model of the antecedents of intentions and behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(11), 1547–1561. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672012711014

- de Leeuw, R. N., Engels, R. C., Vermulst, A. A., & Scholte, R. H. (2008). Do smoking attitudes predict behaviour? A longitudinal study on the bi-directional relations between adolescents' smoking attitudes and behaviours. Addiction, 103(10), 1713–1721. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02293.x

- Desrichard, O., Moussaoui, L. S., Blondé, J., Felder, M., Riedo, G., Folly, L., Falomir-Pichastor, J. M. (2021). Cessation rates from a national collective social network smoking cessation programme: Results from the 'I quit smoking with Facebook on March 21' Swiss programme. Tobacco Control, tobaccocontrol-2020-056182. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-056182

- Desrichard, O., Roché, S., & Bègue, L. (2007). The theory of planned behavior as mediator of the effect of parental supervision: A study of intentions to violate driving rules in a representative sample of adolescents. Journal of Safety Research, 38(4), 447–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsr.2007.01.012

- Fagerström, K. (2012). Determinants of tobacco use and renaming the FTND to the Fagerström Test for Cigarette Dependence. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 14(1), 75–78. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntr137

- Falomir-Pichastor, J. M., Blondé, J., Desrichard, O., Felder, M., Riedo, G., & Folly, L. (2020). Tobacco dependence and smoking cessation: The mediating role of smoker and ex-smoker self-concepts. Addictive Behaviors, 102, 106200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.106200

- Falomir-Pichastor, J. M., & Invernizzi, F. (1999). The role of social influence and smoker identity in resistance to smoking cessation. Swiss Journal of Psychology, 58(2), 73–84. https://doi.org/10.1024//1421-0185.58.2.73

- Fisher, E. B., Jr., Lichtenstein, E., Haire-Joshu, D., Morgan, G. D., & Rehberg, H. R. (1993). Methods, successes, and failures of smoking cessation programs. Annual Review of Medicine, 44, 481–513. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.me.44.020193.002405

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (2010). Predicting and changing behavior: The reasoned action approach. Psychology Press.

- Gmel, G., Kuendig, H., Notari, L., & Gmel, C. (2017). Monitorage suisse des addictions: Consommation d'alcool, tabac et drogues illégales en Suisse en 2016. Addiction Suisse.

- Hagger, M. S., & Hamilton, K. (2021). Effects of socio-structural variables in the theory of planned behavior: A mediation model in multiple samples and behaviors. Psychology & Health, 36(3), 307–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2020.1784420

- Herd, N., Borland, R., & Hyland, A. (2009). Predictors of smoking relapse by duration of abstinence: Findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Addiction, 104(12), 2088–2099. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02732.x

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Hughes, J. R. (2007). Effects of abstinence from tobacco: Valid symptoms and time course. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 9(3), 315–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/14622200701188919

- Jackson, S. E., Proudfoot, H., Brown, J., East, K., Hitchman, S. C., & Shahab, L. (2020). Perceived non-smoking norms and motivation to stop smoking, quit attempts, and cessation: A cross-sectional study in England. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 10487. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-67003-8

- Jackson, S. E., Steptoe, A., & Wardle, J. (2015). The influence of partner's behavior on health behavior change: The English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. JAMA Internal Medicine, 175(3), 385–392. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.7554

- Lareyre, O., Gourlan, M., Stoebner-Delbarre, A., & Cousson-Gélie, F. (2021). Characteristics and impact of theory of planned behavior interventions on smoking behavior: A systematic review of the literature. Preventive Medicine, 143, 106327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106327

- Li, M., Okamoto, R., & Shirai, F. (2019). Factors associated with smoking cessation and relapse in the Japanese smoking cessation treatment program: A prospective cohort study based on financial support in Suita City, Japan. Tobacco Induced Diseases, 17(October), 71. https://doi.org/10.18332/tid/112154

- Little, T. D., Cunningham, W. A., Shahar, G., & Widaman, K. F. (2002). To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 9(2), 151–173. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_1

- Liu, J., Zhao, S., Chen, X., Falk, E., & Albarracín, D. (2017). The influence of peer behavior as a function of social and cultural closeness: A meta-analysis of normative influence on adolescent smoking initiation and continuation. Psychological Bulletin, 143(10), 1082–1115. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000113

- Lüscher, J., Stadler, G., & Scholz, U. (2017). A daily diary Study of joint quit attempts by dual-smoker couples: The role of received and provided social support. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 20(1), 100–107. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntx079

- Margolis, R., & Wright, L. (2016). Better off alone than with a smoker: The influence of partner's smoking behavior in later life. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 71(4), 687–697. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbu220

- McEachan, R. R. C., Conner, M., Taylor, N. J., & Lawton, R. J. (2011). Prospective prediction of health-related behaviours with the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology Review, 5(2), 97–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2010.521684

- McGee, C. E., Trigwell, J., Fairclough, S. J., Murphy, R. C., Porcellato, L., Ussher, M., & Foweather, L. (2015). Influence of family and friend smoking on intentions to smoke and smoking-related attitudes and refusal self-efficacy among 9-10 year old children from deprived neighbourhoods: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 15, 225 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1513-z

- Mohammadi, S., Ghajari, H., Valizade, R., Ghaderi, N., Yousefi, F., Taymoori, P., & Nouri, B. (2017). Predictors of smoking among the secondary high school boy students based on the health belief model. International Journal of Preventive Medicine, 8, 24. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_264_16

- Mottillo, S., Filion, K. B., Bélisle, P., Joseph, L., Gervais, A., O'Loughlin, J., Paradis, G., Pihl, R., Pilote, L., Rinfret, S., Tremblay, M., & Eisenberg, M. J. (2009). Behavioural interventions for smoking cessation: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. European Heart Journal, 30(6), 718–730. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehn552

- Mueller, L. L., Munk, C., Thomsen, B. L., Frederiksen, K., & Kjaer, S. K. (2007). The influence of parity and smoking in the social environment on tobacco consumption among daily smoking women in Denmark. European Addiction Research, 13(3), 177–184. https://doi.org/10.1159/000101554

- Nagelhout, G. E., de Vries, H., Fong, G. T., Candel, M. J., Thrasher, J. F., van den Putte, B., Thompson, M. E., Cummings, K. M., & Willemsen, M. C. (2012). Pathways of change explaining the effect of smoke-free legislation on smoking cessation in The Netherlands. An application of the international tobacco control conceptual model. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 14(12), 1474–1482. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/nts081

- Norman, P., Conner, M., & Bell, R. (1999). The theory of planned behavior and smoking cessation. Health Psychology, 18(1), 89–94. https://doi.org/10.1037//0278-6133.18.1.89

- Reid, M., Sparks, P., & Jessop, D. C. (2018). The effect of self-identity alongside perceived importance within the theory of planned behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology, 48(6), 883–889. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2373

- Schoenaker, D., Brennan, E., Wakefield, M. A., & Durkin, S. J. (2018). Anti-smoking social norms are associated with increased cessation behaviours among lower and higher socioeconomic status smokers: A population-based cohort study. PLoS One, 13(12), e0208950. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0208950

- Scholz, U., Berli, C., Goldammer, P., Lüscher, J., Hornung, R., & Knoll, N. (2013). Social control and smoking: Examining the moderating effects of different dimensions of relationship quality. Families, Systems & Health, 31(4), 354–365. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033063

- Takagi, D., Yokouchi, N., & Hashimoto, H. (2020). Smoking behavior prevalence in one's personal social network and peer's popularity: A population-based study of middle-aged adults in Japan. Social Science & Medicine, 260, 113207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113207

- Topa, G., & Moriano, J. A. (2010). Theory of planned behavior and smoking: Meta-analysis and SEM model. Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation, 1, 23–33. https://doi.org/10.2147/SAR.S15168

- Warner, L. M., Stadler, G., Lüscher, J., Knoll, N., Ochsner, S., Hornung, R., & Scholz, U. (2018). Day-to-day mastery and self-efficacy changes during a smoking quit attempt: Two studies. British Journal of Health Psychology, 23(2), 371–386. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12293

- Westmaas, J. L., Wild, T. C., & Ferrence, R. (2002). Effects of gender in social control of smoking cessation. Health Psychology, 21(4), 368–376. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.21.4.368