Abstract

Objective

Routine, population-wide cervical screening programmes reduce cervical cancer incidence and mortality. However, socioeconomically deprived communities and ethnic minority groups typically have lower uptake in comparison to the general population and thus are described as ‘underserved.’ A systematic qualitative literature review was conducted to identify relevant determinants of participation for these groups.

Methods

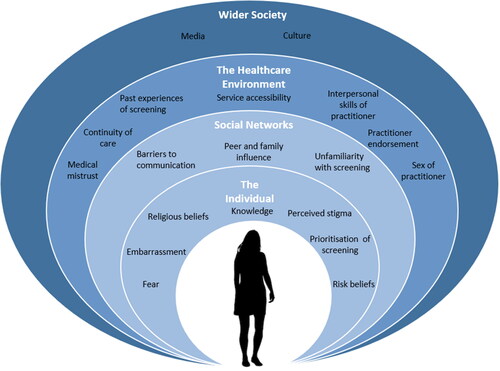

Online databases were searched for relevant literature from countries with well-established, call-recall screening programmes. Overall, 24 articles were eligible for inclusion. Data was synthesized via Framework synthesis. Dahlgren & Whitehead’s social model of health was used as a broad a priori coding framework.

Results

Participation was influenced by determinants at multiple levels. Overall, patient-provider relationships and peer support facilitated engagement. Cultural disparities, past healthcare experience and practical barriers hindered service access and exacerbated negative thoughts, feelings and attitudes towards participation. Complex interrelationships between determinants suggest barriers have a cumulative effect on screening participation.

Conclusions

These findings present a framework of psychosocial determinants of cervical screening uptake in underserved women and emphasise the role of policy makers and practitioners in reducing structural barriers to screening services. Additional work, exploring the experience of those living within socioeconomically disadvantaged areas, is needed to strengthen understanding in this area.

Background

Cervical screening aims to detect precancerous, and often symptomless, abnormalities within the cervix, and prevent cervical cancer morbidity and mortality. Although this is sometimes referred to as ‘cervical cancer screening’, the test is not designed to detect cancer and is intended as a preventative measure. To avoid confusion and potentially deterring people from screening, many organisations now use the term ‘cervical screening’ rather than ‘cervical cancer screening’ (NHS, Citation2020; Public Health England, Citation2021; Australian Government Department of Health, Citation2021).

Many countries, such as Finland, Netherlands and the United Kingdom (UK), have implemented population-wide cervical screening programmes in which women are invited to be screened at regular intervals. Whilst target age groups and screening intervals differ across countries, organised screening programmes have been shown to significantly reduce rates of cervical cancer incidence and mortality, increase equity of access, and thus improve programme efficacy and cost-effectiveness (Arbyn et al., Citation2010; Elfström et al., Citation2015; Jansen et al., Citation2020). Indeed, in the UK alone, it is estimated that the national cervical screening programme saves around 5,000 premature deaths from cervical cancer each year (Cancer Research UK, Citation2017). Despite these benefits, socioeconomic inequalities in uptake remain (De Prez et al., Citation2021). Whilst attendance data by socioeconomic status (SES) is not always collected at population level, research evidence from multiple countries demonstrates that those from socioeconomically deprived communities are less likely to attend routine cervical screening in comparison to those of higher socioeconomic status (Douglas et al., Citation2016; Chorley et al., Citation2017; Harder et al., Citation2018; Leinonen et al., 2017; Bongaerts et al., Citation2020). These inequalities are particularly problematic given non-attendance at routine screening substantially increases risk of cervical cancer mortality (Dugué et al., Citation2014). Higher rates of non-participation within underserved groups are therefore likely to result in higher ill-health burden within already disadvantaged communities. For example, cervical cancer incidence rates are 72% higher for women living in the most deprived areas in England, in comparison to the least deprived. Moreover, women living in the most deprived areas in England are 148% more likely to die from cervical cancer in comparison to women living in the least deprived areas (Public Health England, 2014). As such, it is important to understand factors influencing cervical screening participation within low SES groups. Given the association of deprivation with ethnic minority status (Office for National Statistics, Citation2018), it is also important to ensure that efforts to understand socioeconomic inequalities include evidence which elucidates factors important to ethnic minority groups. This is particularly relevant in relation to cervical screening as past research has consistently highlighted those from ethnic minority groups are also often less likely to participate in routine screening (Bongaerts et al., Citation2020; Azerkan et al., Citation2012; Idehen et al., Citation2018; Lovell et al., Citation2015; Marlow et al., Citation2015; Moser et al., Citation2009).

Participation in routine cervical screening is complex and dependent on multiple factors that are situated within psychological, sociocultural and environmental contexts (Chorley et al., Citation2017; Sorensen et al., Citation2003). Survey data suggests negative attitudes and beliefs towards cervical screening, poor screening-related knowledge, fear and embarrassment surrounding the procedure, work commitments and childcare challenges are common barriers to participation (Lovell et al., Citation2015; Marlow et al., Citation2015; Tran et al., Citation2011; Tung et al., Citation2017). Understanding of these factors has been advanced by qualitative methods. Qualitative approaches have contextualised determinants, providing rich, in-depth exploration of women’s experience of, and perspectives towards, cervical screening. Such studies have echoed the barriers highlighted above and demonstrated the complexity of cervical screening related behaviour, whereby individual’s attendance is often related to multiple factors and circumstances rather than one specific determinant (Oscarsson et al., Citation2008; Marlow et al., Citation2019; Waller et al., Citation2012; Logan & McIlfatrick, Citation2011; Cadman et al., Citation2012).

Whilst individual qualitative studies offer important insight, synthesising bodies of qualitative evidence allows researchers to develop new and detailed insight into a phenomena. This approach can also highlight previously unexplored pathways to behavioural change (Seers, Citation2014). Previously, researchers have synthesised qualitative evidence to gain insight into determinants of engagement with cancer screening programmes. Young et al. (Citation2018) reviewed qualitative literature in the UK which focused on factors influencing the decision to attend for cancer screening. Although considering cancer screening broadly, this review highlighted the influence of patient-provider relationships, cancer-related fear and risk beliefs/discourses in contributing to decisions surrounding screening attendance. More specifically to cervical screening, Chorley et al. (Citation2017) synthesised 39 studies that explored factors influencing cervical screening participation. This review emphasised screening as a behaviour that was consistently reassessed and revaluated over time, determined predominately by women’s thoughts and perceptions of the test as they considered the relevance and value of screening in conjunction with their emotional responses towards (and previous experiences of) the procedure. To a lesser extent, extrinsic factors such as competing priorities and practical barriers, were also identified and discussed as factors that may influence screening participation.

These reviews provide detailed insight into screening participation. However, much existing cervical screening literature tends to focus on individual level factors (e.g., beliefs, attitudes, emotions), with less attention given to social or environmental based barriers to engagement. This may lead to an over-emphasis on individual responsibility to, for example, ‘change’ one’s thoughts, feelings and behaviours which in turn can inadvertently increase challenges to service access for marginalised or underserved groups (e.g. those of low socioeconomic status or those from ethnic minority groups) (Lorenc et al., Citation2013; McGill et al., 2015; White et al., Citation2009). Situating these determinants within wider social, structural and cultural contexts would therefore be valuable, particularly as doing so allows researchers to explore and understand how multi-level factors interact with one another to influence behaviour (Public Health England, Citation2017; Marmot et al., 2010).

Existing reviews also present an overview of determinants in the context of a generalised female population. The perspectives of ethnic minority and deprived communities tend to be largely absent from academic research (Bonevski et al., Citation2014) and as such, it is currently difficult to determine how these generalised determinants of uptake are relevant to these underserved groups. Whilst reviews of the literature focusing solely on underserved populations are scarce, there are some examples of systematic reviews which have aimed to identify specific determinants of screening participation within those least likely to attend (Lee, Citation2015; Johnson et al., Citation2008; Chan & So, Citation2017). However, these reviews consider participation across a variety of international screening services, some of which come with a cost attached, or are not available country-wide, unlike the free screening programmes available within countries such as the UK, Australia, Denmark and Sweden. Due to these disparities, it remains important to consider specific determinants of cervical screening participation for underserved women, in the context of population wide call-recall programmes (i.e. whereby women are invited/recalled to participate at regular intervals).

Given the existing disparities in routine cervical screening uptake, the present review therefore aims to systematically collate and synthesise qualitative literature which explore determinants of cervical screening participation within the context of population wide call-recall screening programmes. Specifically, this review aims to synthesise the views of ethnic minority women and women living in socioeconomically deprived communities, identifying key commonalities across these underserved groups.

Method

The present qualitative systematic review adheres to ENTREQ guidelines for reporting qualitative synthesis (Tong et al., Citation2012) (see Supplementary Materials A).

Defining terms

The present review uses the term ‘underserved women’ to collectively refer to a) women of ethnic minority status and b) those of low socioeconomic status. For the purposes of clarity, further defining details of these sub-groups are included in Supplementary Materials B.

Search strategy

A comprehensive search of Web of Science, Scopus, MEDLINE, CINAHL and PsycARTICLES databases were carried out in June 2018 to identify relevant literature. Grey literature was searched via Proquest Dissertation and Theses. Databases were searched with broad search terms relating to determinants of cervical screening participation to minimise the risk of missing any potentially relevant studies. An example search strategy is presented in Supplementary Materials C and was developed from a previously published systematic review in the field (Chorley et al., Citation2017). Forward and backward citation searching was conducted on all included studies. The reference lists of full text articles were also hand searched for additional eligible literature. This search strategy was repeated in January 2021, to incorporate relevant literature published in between September 2018 and January 2021, in line with guidance from Cochrane on updating systematic reviews (Cumpston et al., Citation2020).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Articles were included under a strict set of eligibility criteria. We included any paper that included women’s detailed, perspectives and/or experiences regarding participation (or non-participation) in routine cervical screening, within healthy samples of adult women eligible for routine screening (in their country of residence) who, in addition, can be classified as belonging to an ethnic minority or low socioeconomic status group. Articles should also be based within a country with a well-established (i.e. 10 years+) call-recall programme (i.e. at the time of the review this included the UK, Australia, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Korea, the Netherlands, Norway, Slovenia and Sweden), and published at least 10 years after the initiation of routine screening within that country (See Supplementary materials D). This is to ensure views were in reference to an established programme which was familiar at a societal level. In addition, articles were excluded if no analysis of primary data was included and/or if the full-text was not available in English.

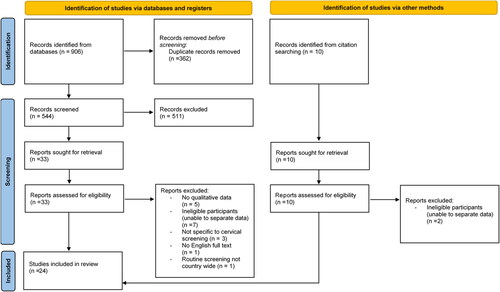

Data extraction

Identified records were initially stored on Endnote. Following the removal of duplications, AW screened title and abstracts for potential eligibility. The remaining full-text articles were then screened in line with the eligibility criteria. At both the title/abstract screening, and full text screening stages, LS acted as an independent, second reviewer and screened 20% of the sample. Rates of concordance between the first and second reviewer were high (96% overall). Any disagreements were resolved via discussion.

Data synthesis

Thomas, O’Mara-Eves, Harden and Newman (Citation2017) suggest that the process of framework synthesis can described in two broad stages: Developing or selecting an initial framework and Recognising patterns through aggregation.

Stage one: Selecting an initial framework

To ensure cervical screening was considered within wider social and cultural contexts, it was important to select a framework which incorporates a holistic view of determinants that may influence an individual’s health and/or health behaviours. Dahlgren and Whitehead’s (Citation1991) Social Model of Health was deemed a suitably broad and inclusive framework for the current synthesis, which outlines the multi-level determinants of health and health behaviours. This model also emphasises interactions between determinants, demonstrating how individual-level factors are situated within, and relate to the social, economic and cultural environment. Moreover, as this model is widely used throughout health and health-related literature (Public Health England, Citation2017; Bambra et al., Citation2010), the application of this model to the current dataset also facilitates outcomes that are useful for policy and practice.

Stage two: Recognising patterns through aggregation

Eligible literature was uploaded to NVivo version 12. Any text that referred to the findings of the included studies were line by line coded and grouped thematically in line with the initial framework. The coded text included participant quotes and interpretive text from the author(s). Text excluded from coding (e.g. text quoting/referring to the opinions of health professionals or from comparison groups who did not fit the eligibility criteria) is summarised in Supplementary Materials E. Coding and analysis was primarily conducted by the lead author (AW) who is an experienced qualitative researcher. AW also met regularly with LS to check coding/thematic development and discuss findings. During this stage, the initial framework was iteratively adapted to reflect the content of the synthesised literature i.e. by incorporating codes and themes identified during the coding process.

Data relating to each aspect of the finalised framework was extracted into tabular format in Microsoft Word, and then reviewed again to ensure themes and sub-themes were addressing the overall study aims. The studies contributing to each aspect of the framework were expressed in tabular format (see Supplementary Materials F), to illustrate the robustness of the review and relative weight of each determinant/aspect.

Quality assessment

Whilst there is a lack of consensus around appraising methodological quality in qualitative syntheses (Garside, Citation2014), the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist is the most commonly used within health and social care related literature reviews (Dalton et al., Citation2017). This checklist guides systematic appraisal of studies on the basis of 10 questions relating to the reporting of the research, appropriateness of chosen methodologies and rigour of data analysis. The first 9 questions are answered via yes/no (or unsure) checkboxes and with the statement of value being made for the final question. Included literature was assessed, via the CASP checklist, by AW and checked by LS. Quality was assessed purely for guidance purposes, as poor reporting does not adequately justify excluding valuable participant data (Garside, Citation2014; Sandelowski et al., Citation1997; McGeechan et al., Citation2021). However, no studies were found to be of low quality (See Supplementary Materials G)

Results

Search results

Following the literature search (and after removal of duplications), 544 articles were screened, with 511 being removed due to ineligibility. During the second (full text) round of screening, 19 further articles were removed. Overall, 24 studies were included within the final review. Further details of this process can be found in . As highlighted within the inclusion criteria, all participants were residents of a country with a population-wide, routine, call-recall cervical screening programme. In addition, all participants were eligible to participate in their home country’s routine screening programme. The vast majority of the studies (n = 21) focused on the perspectives of ethnic minority women with 2 studies focused on the perspectives of women from deprived communities. The one remaining study included the perspectives of both ethnic minority women and those of low socioeconomic status (i.e., two focus groups included those of low socioeconomic status and four focus groups included those of ethnic minority).

Summary of study characteristics

Of the studies recruiting ethnic minority women, nine were carried out in the UK, six were carried out in Australia, two in Norway, three in the Netherlands, one in Sweden, one in Finland. The majority of studies (n = 16) were focused upon migrant women. Two further studies grouped women as a minority based upon their religious beliefs, three studies classified participants as an ethnic minority if they self-defined as an ethnic group other than the country’s majority population and one study described participants as an ethnic minority in relation to their language group (without reference to migrant status).

Of the three studies specifically recruiting women of low socioeconomic status, two were carried out in the UK and the remaining study was carried out in Australia. Two studies classified participants as low socioeconomic status as they lived within areas of high deprivation. The remaining study classified participants by their social grade i.e., including those who were from social grades C (lower middle class/skilled working class) through to E (non-working). Further characteristics of the 24 included studies are presented in Supplementary Materials H.

Data synthesis

Literature was synthesized using Framework Synthesis. Four over-arching, inter-dependant levels of influence were developed: 1) The Individual, 2) Social Context, 3) The Healthcare Environment and 4) Wider Society. All levels were influential across both ethnic minority women and women of low socioeconomic status, however the type of influence within each level (i.e., sub-themes) were often underpinned by sociodemographic context (See Supporting Information 2 for an overview of how reviewed studies mapped to themes/sub-themes). A conceptual framework, outlining the major themes and sub-themes relevant to underserved women, is presented in . A narrative outline of sub-themes are presented below, with accompanying illustrative quotes shown in .

Table 1. Illustrative quotes supporting themes and sub-themes.

The individual

Embarrassment

Embarrassment was a prominent sub-factor associated with cervical screening, mentioned across 15 studies (Addawe et al., Citation2018; Abdullahi et al., Citation2009; Anaman-Torgbor et al., Citation2017; Batarfi, Citation2012; Butler et al., Citation2020; Gele et al., Citation2017; Hamdiui et al., Citation2021; Kwok et al., Citation2011; Logan & McIlfatrick, Citation2011; Marlowet al., Citation2015; Marlow et al., Citation2019; Ogunsiji et al., Citation2013; Parajuli et al., Citation2020; Patel et al., 2019; Szarewski et al., Citation2009) (). The procedure itself was deemed to be both physically and emotionally invasive, and those with strong religious or cultural beliefs felt there was an aspect of shame associated with ‘exposing’ oneself, even to medical professionals (Hamdiui et al., Citation2021; Parajuli et al., Citation2020; Abdullahi et al., Citation2009; Anaman-Torgbor et al., Citation2017; Kwok et al., Citation2011; Marlow et al., Citation2015). Some deemed it embarrassing to talk about cervical screening with others, particularly if incompatible with their cultural norms (Butler et al., Citation2020; Parajuli et al., Citation2020; Addawe et al., Citation2018; Chiu et al., Citation1999). These feelings of embarrassment and shame decreased women’s motivation to make appointments and were a key barrier to attending or reattending routine cervical screening.

Fear

Participants in 17 studies (Addawe et al., Citation2018; Abdullahi et al., Citation2009; Anaman-Torgbor et al., Citation2017; Azerkan et al., Citation2015; Batarfi, Citation2012; Butler et al., Citation2020; Cadman et al., Citation2015; Chiu et al., 1999; Gele et al., Citation2017; Hamdiui et al., Citation2021; Kwok et al., Citation2011; Logan & McIlfatrick, Citation2011; Marlow et al., Citation2019; Marlowet al., Citation2015; Ogunsiji et al., Citation2013; Omolo, Citation2019; Szarewski et al., Citation2009) discussed feeling fear in relation to making, attending or even talking about a cervical screening appointment. This fear appeared to be related to two distinct aspects of the screening process; fear of the actual test, and fear of the potential outcome. In the most extreme case some participants suggested they would prefer to die without knowing they had cancer than attend screening and find out in advance (Anaman-Torgbor et al., Citation2017; Gele et al., Citation2017). Although in some cases, the perceived severity of cancer acted as a facilitator to attendance (Patel et al., Citation2020; Hamdiui et al., Citation2021; Omolo, Citation2019). In two studies, women suggested that the anticipated relief of receiving a positive outcome could overcome these fears, with the benefits of screening outweighing their own emotional response to the test (Butler et al., Citation2020; Marlow et al., Citation2015).

Risk beliefs

Fifteen studies (Addawe et al., Citation2018; Abdullahi et al., Citation2009; Azerkan et al., Citation2015; Butler et al., Citation2020; Gele et al., Citation2017; Hamdiui et al., Citation2021; Idehen et al., Citation2020; Kwok et al., Citation2011; Marlow et al., Citation2019; Marlow et al., Citation2015; Ogunsiji et al., Citation2013; Omolo, Citation2019; Parajuli et al., Citation2020; Patel et al., Citation2019; Szarewski et al., Citation2009) outlined the influence of cervical cancer related risk beliefs on screening engagement. Women felt they were at low risk of developing cancer if they only had one sexual partner or were in a monogamous long-term relationship (Marlow et al., Citation2019; Hamdiui et al., Citation2021; Kwok et al., Citation2011; Szarewski et al., Citation2009; Azerkan et al., Citation2015). Some held a belief that those from Somalian or Muslim cultures do not develop cancer, due in part to the perception that their religious background was a protective factor for cancer. This in turn was associated with the presence of misinformation and a lack of screening related knowledge within the community (Abdullahi et al., Citation2009; Gele et al., Citation2017). There were also some participants that felt that because they had no concerning symptoms, or were not worried about cervical cancer, they would not be at risk of developing the disease (Marlow et al., Citation2019; Parajuli et al., Citation2020; Ogunsiji et al., Citation2013; Batarfi, Citation2012; Marlow et al., Citation2015; Azerkan et al., Citation2015; Omolo, Citation2019). All of these risk beliefs were a significant barrier to attending screening services, as women felt there was no urgent need to attend under these circumstances. In contrast, the perceived severity of cervical cancer (Hamdiui et al., Citation2021; Omolo, Citation2019) and symptomless nature of the disease (Patel et al., Citation2020; Marlow et al., Citation2015) encouraged intentions to screen.

Religious beliefs

Participants across eight studies (Addawe et al., Citation2018; Abdullahi et al., Citation2009; Anaman-Torgbor et al., Citation2017; Batarfi, Citation2012; Cadman et al., Citation2015; Gele et al., Citation2017; Hamdiui et al., Citation2021; Salad et al., 2015) also referred to their religious belief’s surrounding sickness and disease and suggested that praying to Allah or God would keep them safe from cervical cancer (Batarfi, Citation2012; Gele et al., Citation2017). Some believed the development of cervical cancer to be the result of a curse or engagement in negative behaviours or attitudes (Anaman-Torgbor et al., Citation2017; Batarfi, Citation2012). Religious beliefs were often also tied to fatalistic attitudes towards cervical cancer, suggesting that it was ‘God’s ‘will’ or ‘fate’ if one developed, or indeed was cured of, this disease (Cadman et al., Citation2012; Hamdiui et al., Citation2021; Abdullahi et al., Citation2009; Addawe et al., Citation2018; Salad et al., Citation2015). This in turn suggested cervical screening was an unnecessary procedure, which could do little to alter the already inevitable. In contrast, two studies highlighted a religious-based responsibility to take care of one’s own health, and engage with the medical options available to them (Hamdiui et al., Citation2021; Salad et al., Citation2015).

Prioritising competing demands

Eleven studies (Addawe et al., Citation2018; Logan & McIlfatrick, Citation2011; Butler et al., Citation2020; Parajuli et al., Citation2020; Addawe et al., Citation2018; Batarfi, Citation2012; Gele et al., Citation2017; Marlow et al., Citation2015; Szarewski et al., Citation2009; Azerkan et al., Citation2015; Hamidiui et al., Citation2021) directly referred to competing demands throughout individuals’ everyday lives, and discussed how cervical screening was often prioritised last. Home life, work life and paying bills were deemed more urgent and more important than participating in cervical screening, with some suggesting that their own health in general was not a priority when they had so many different responsibilities to manage (Butler et al., Citation2020; Gele et al., Citation2017; Marlow et al., Citation2015; Szarewski et al., Citation2009). Migrant participants also had increased demands and responsibilities such as finding employment, accommodation and schooling for children which similarly needed to take priority over and above arranging cervical screening appointments (Patel et al., Citation2020; Parajuli et al., Citation2020; Azerkan et al., Citation2015). Some participants suggested screening was often postponed or forgotten about due to these complex, competing demands (Marlow et al., Citation2019; Logan & McIlfatrick, Citation2011; Addawe et al., Citation2018; Marlow et al., Citation2015; Azerkan et al., Citation2015).

Perceived stigma

Eight studies (Marlow et al., Citation2019; Logan & McIlfatrick, Citation2011; Butler et al., Citation2020; Hamdiui et al., Citation2021; Parajuli et al., Citation2020; Gele et al., Citation2017; Marlow et al., Citation2015; Szarewski et al., Citation2009) referred to perceptions of stigma surrounding participation in cervical screening. Women expressed a concern that they would be negatively judged, as screening attendance indicated to others that they were sexually active (Marlow et al., Citation2019; Logan & McIlfatrick, Citation2011; Szarewski et al., Citation2009). This was also exacerbated by the belief that cervical cancer was caused by promiscuity, which was particularly problematic for those with strong religious networks (Marlow et al., Citation2019; Hamdiui et al., Citation2021; Marlow et al., Citation2015).

Knowledge

There was a general lack of knowledge regarding the purpose of cervical screening, across 19 studies (Addawe et al., Citation2018; Abdullahi et al., Citation2009; Anaman-Torgbor et al., Citation2017; Azerkan et al., Citation2015; Batarfi, Citation2012; Butler et al., Citation2020; Chiu et al., 1999; Gele et al., Citation2017; Hamdiui et al., Citation2021; Idehen et al., Citation2020; Jackowska et al., Citation2012; Kwok et al., Citation2011; Logan & McIlfatrick, Citation2011; Marlow et al., Citation2019; Marlow et al., Citation2015; Ogunsiji et al., Citation2013; Omolo, Citation2019; Parajuli et al., Citation2020; Patel et al., Citation2019) . Some participants did not associate screening with cervical cancer and in some cases believed the test was carried out to detect other diseases or infections (i.e., such as HIV or syphilis) (Anaman-Torgbor et al., Citation2017). This was sometimes linked to unfamiliarity with the test for migrants who had no experience of the procedure within their home countries (Ogunsiji et al., Citation2013) and/or a lack of accessible cervical screening related information (Logan & McIlfatrick, Citation2011; Anaman-Torgbor et al., Citation2017; Chiu et al., Citation1999). Others held beliefs that were rooted within incorrect knowledge about cervical cancer (for example, that a lack of symptoms meant that they did not need to attend cervical screening) (Marlow et al., Citation2019; Patel et al., Citation2020; Abdullahi et al., Citation2009; Addawe et al., Citation2018; Gele et al., Citation2017; Chiu et al., Citation1999; Azerkan et al., Citation2015). A lack of knowledge did not always lead to non-participation. Some participants explained that they had taken part in cervical screening simply because family members and/or health professionals had told them they should, with little knowledge or understanding of the benefits or costs of the test (Parajuli et al., Citation2020; Kwok et al., Citation2011; Chiu et al., Citation1999; Idehen et al., Citation2020).

Social context

Peer and family influence

Twelve studies (Logan & McIlfatrick, Citation2011; Butler et al., Citation2020; Hamdiui et al., Citation2021; Abdullahi et al., Citation2009; Batarfi, Citation2012; Gele et al., Citation2017; Marlow et al., Citation2015; Chiu et al., Citation1999; Azerkan et al., Citation2015; Idehen et al., Citation2020; Jackowska et al., Citation2012; Ogunsiji et al., 2013) outlined the importance of social context in both deterring and facilitating cervical screening engagement. Strong social networks facilitated screening access, particularly for newly arrived women who found the process of settling into a new country, registering with numerous healthcare providers and services, overly complex (Butler et al., Citation2020; Hamdiui et al., Citation2021; Batarfi, Citation2012; Azerkan et al., Citation2015; Idehen et al., Citation2020).

Close family members were felt to be particularly influential in facilitating appointment making and encouraging attendance (Azerkan et al., Citation2015). Conversely, hearing negative stories and experiences from others, or even never having heard about female relatives attending screening could increase barriers to their own engagement (Logan & McIlfatrick, Citation2011; Parajuli et al., Citation2020; Abdullahi et al., Citation2009; Jackowska et al., Citation2012; Ogunsiji et al., Citation2013). Husbands were particularly influential, especially for those who were reliant on their partners for translation services. In some cases, participants suggested they would not, or could not, attend if their partner held negative views towards cervical screening (Batarfi, Citation2012; Gele et al., Citation2017; Chiu et al., Citation1999; Azerkan et al., Citation2015).

Barriers to communication

Fifteen studies (Addawe et al., Citation2018; Abdullahi et al., Citation2009; Anaman-Torgbor et al., Citation2017; Azerkan et al., Citation2015; Batarfi, Citation2012; Chiu et al.,1999; Gele et al., Citation2017; Hamdiui et al., Citation2021; Idehen et al., Citation2020; Jackowska et al., Citation2012; Kwok et al., Citation2011; Omolo, Citation2019; Parajuli et al., Citation2020; Patel et al., Citation2019; Szarewski et al., Citation2009) highlighted the impact of communication barriers, particularly amongst those who did not speak English as a first language. Participants described difficulties in reading and comprehending written information related to screening (thus not appreciating the importance of attendance) (Anaman-Torgbor et al., Citation2017; Batarfi, Citation2012; Patel et al., Citation2020; Hamdiui et al., Citation2021; Addawe et al., Citation2018; Gele et al., Citation2017; Szarewski et al., Citation2009; Azerkan et al., Citation2015; Omolo, Citation2019; Idehen et al., Citation2020) and in verbally communicating with health professionals (Kwok et al., Citation2011; Chiu et al., Citation1999; Azerkan et al., Citation2015; Jackowska et al., Citation2012). Some needed to attend their GP practice with their husbands or sons as they were not always aware that they could have access to a translator (Hamdiui et al., Citation2021; Parajuli et al., Citation2020; Abdullahi et al., Citation2009; Batarfi, Citation2012; Gele et al., Citation2017). Even those who could communicate well in English, outlined more nuanced difficulties in communication (e.g., expressing their thoughts and feelings clearly) during such a personal procedure, and experienced and/or expected negative attitudes or judgement from health professionals because of their ethnic status (Kwok et al., Citation2011; Chiu et al., Citation1999; Idehen et al., Citation2020).

Unfamiliarity with screening

Eleven studies (Addawe et al., Citation2018; Abdullahi et al., Citation2009; Anaman-Torgbor et al., Citation2017; Azerkan et al., Citation2015; Cadman et al., Citation2015; Chiu et al., Citation1999; Idehen et al., Citation2020; Ogunsiji et al., Citation2013; Omolo, Citation2019; Parajuli et al., Citation2020; Team et al., Citation2013) referred to a lack of familiarity with cervical screening. As well as being exacerbated by the language barriers and lack of peer/family support described above, migrant participants discussed the differences between healthcare in their home country and the country they were living in now; this being particularly problematic when individuals had migrated from countries with no formal screening programme (Addawe et al., Citation2018; Abdullahi et al., Citation2009; Ogunsiji et al., Citation2013; Anaman-Torgbor et al., Citation2017; Cadman et al., Citation2015). For some however, this unfamiliarity was not necessarily with the concept of cervical screening in itself, but with the way that cervical screening was delivered. Team et al. (Citation2013) described the disparities between healthcare in Russia (where women would be penalised if they did not participate in regular health checks) and the free choice that existed within the women’s new place of residence. Unfamiliarity with their new healthcare system thus resulted in perceptions that cervical screening was unimportant (i.e.as it would be compulsory if important to participate in).

Healthcare environment

Past experiences of screening and healthcare

Eleven studies (Marlow et al., Citation2019; Butler et al., Citation2020; Parajuli et al., Citation2020; Abdullahi et al., Citation2009; Anaman-Torgbor et al., Citation2017; Kwok et al., Citation2011; Marlow et al., Citation2015; Chiu et al., Citation1999; Azerkan et al., Citation2015; Idehen et al., Citation2020; Peters, Citation2010) referred to participant’s past healthcare experiences as a potential barrier to future engagement. Overall, negative past experiences of the test (such as pain and/or bleeding) reduced the likelihood of future attendance. Moreover, migrant women described negative screening experiences that arose due to language barriers; for example some studies included accounts of women participating in cervical screening without the procedure being explained to them (thus also highlighting a lack of informed consent) (Butler et al., Citation2020; Parajuli et al., Citation2020; Abdullahi et al., Citation2009; Chiu et al., Citation1999). Impersonal and ‘clinical’ environments and/or screening facilities (in one instance likened to ‘herding cattle’; (Azerkan et al., Citation2015) were also off-putting to service users and increased barriers to future participation.

Sex of practitioner

Fifteen studies (Addawe et al., Citation2018; Abdullahi et al., Citation2009; Anaman-Torgbor et al., Citation2017; Batarfi, Citation2012; Butler et al., Citation2020; Chiu et al., Citation1999; Gele et al., Citation2017; Hamdiui et al., Citation2021; Kwok et al., Citation2011; Logan & McIlfatrick, Citation2011; Marlow et al., 2015; Omolo, Citation2019; Parajuli et al., Citation2020; Peters, Citation2010; Szarewski et al., Citation2009) emphasised that access to a female screen-taker was key to encouraging screening participation. Across studies, the potential of a male screen-taker was off-putting to participants, resulting in feelings of embarrassment and indignity, and encouraged postponement. Female practitioners were believed to be more understanding and empathic; participants suggested they could be more open about their fears, questions and concerns if they were speaking to a professional who had also experienced the screening procedure (Butler et al., Citation2020; Batarfi, Citation2012; Kwok et al., Citation2011; Peters, Citation2010).

Interpersonal skills of practitioners

Although female staff were preferred throughout, this alone was not enough for participants to feel at ease with the screening procedure. Thirteen studies (Marlow et al., Citation2019; Logan & McIlfatrick, Citation2011; Butler et al., Citation2020; Addawe et al., Citation2018; Anaman-Torgbor et al., Citation2017; Gele et al., Citation2017; Marlow et al., Citation2015; Azerkan et al., Citation2015; Cadman et al., Citation2015; Idehen et al., Citation2020; Jackowska et al., Citation2012; Peters, Citation2010; Kwok et al., Citation2011) outlined the influence of practitioners’ general interpersonal skills. Women spoke favourably about healthcare staff who explained the procedure well and were friendly and approachable (e.g. Idehen et al., Citation2020; Jackowska et al., Citation2012). However, some participants described contrasting experiences; feeling misunderstood, unheard, ‘shouted at’ and/or rushed by healthcare staff which in turn, was a barrier to future participation (Marlow et al., Citation2019; Logan & McIlfatrick, Citation2011; Butler et al., Citation2020; Idehen et al., Citation2020).

Continuity of care

In addition to a female practitioner (see ‘Sex of practitioner’ above), four studies (Butler et al., Citation2020; Batarfi, Citation2012; Marlow et al., Citation2015; Peters, Citation2010) expressed the importance of a regular health-care practitioner and outlined women’s desire to see a doctor who they had previously built a rapport with and who was already familiar with their medical history. This was deemed particularly important in relation to those who had suffered sexual abuse, so individuals were not required to repeatedly explain their background to various different members of staff (Peters, Citation2010). Poor continuity of care, or access to a familiar/trusted practitioner was therefore a barrier to screening for some service users.

Medical mistrust

Participants across seven studies (Marlow et al., Citation2019; Patel et al., Citation2020; Addawe et al., Citation2018; Batarfi, Citation2012; Gele et al., Citation2017; Azerkan et al., Citation2015; Jackowska et al., Citation2012) discussed the mis/trust they felt in relation to their healthcare providers. Migrant women in particular, expressed mistrust toward healthcare providers within the country they were currently residing in, sometimes referring to (their own or others’) experiences of medical mistakes or inadequate healthcare as validation (Batarfi, Citation2012; Gele et al., Citation2017; Jackowska et al., Citation2012). These women often preferred to verify medical decisions and diagnoses with practitioners in their countries of birth. In some cases, participants also described travelling, or intending to travel, back to their country of birth for screening (Patel et al., Citation2020; Jackowska et al., Citation2012).

Practitioner endorsement

Thirteen studies (Anaman-Torgbor et al., Citation2017; Azerkan et al., Citation2015; Batarfi, Citation2012; Gele et al., Citation2017; Hamdiui et al., Citation2021; Idehen et al., Citation2020; Kwok et al., Citation2011; Marlow et al., 2019; Ogunsiji et al., Citation2013; Omolo, Citation2019; Parajuli et al., Citation2020; Patel et al., Citation2019; Team et al., Citation2013) suggested women were more likely to attend cervical screening if they felt attendance was endorsed by a known health professional. Participants discussed being reminded or encouraged to attend when visiting their GP practice. Some also felt a personally addressed invitation letter was encouraging and also acted as a reminder to book their appointment (Hamdiui et al., Citation2021; Batarfi, Citation2012). Reliance on GP encouragement was particularly strong within individuals who had migrated from a country with a more compliance-based healthcare system (Patel et al., Citation2020; Team et al., Citation2013).

Service accessibility

Ten studies (Marlow et al., Citation2019; Logan & McIlfatrick, Citation2011; Butler et al., Citation2020; Parajuli et al., Citation2020; Abdullahi et al., Citation2009; Addawe et al., Citation2018; Kwok et al., Citation2011; Marlow et al., Citation2015; Idehen et al., Citation2020; Jackowska et al., Citation2012) referred to practical factors related to screening service access. Some migrant participants said receiving an invitation letter, to a free-of-charge test, facilitated attendance (Kwok et al., Citation2011; Idehen et al., Citation2020; Jackowska et al., Citation2012). Despite this, many women still faced practical barriers to accessing screening services and, across studies, highlighted lack of childcare, difficulties with travelling to screening locations and unsuitable appointment times.

The wider society

Culture

Thirteen studies (Addawe et al., Citation2018; Abdullahi et al., Citation2009; Anaman-Torgbor et al., Citation2017; Azerkan et al., Citation2015; Batarfi, Citation2012; Butler et al., Citation2020; Gele et al., Citation2017; Hamdiui et al., Citation2021; Idehen et al., Citation2020; Kwok et al., Citation2011; Ogunsiji et al., Citation2013; Parajuli et al., Citation2020; Salad et al., 2015) explicitly discussed the role of culture on migrant women’s thoughts, feelings and choices surrounding routine cervical screening. Women highlighted disparities between their own cultural background and that of the country they now resided in as a barrier to engagement in cervical screening. For example, African women felt there was stigma surrounding female circumcision and were apprehensive in attending cervical screening, where they felt they may be judged by health professionals (Addawe et al., Citation2018; Abdullahi et al., Citation2009; Anaman-Torgbor et al., Citation2017; Gele et al., Citation2017; Salad et al., Citation2015). Others described cultural beliefs that were not in line with the idea of preventative health (for example, that ‘searching’ for disease may ‘trigger’ ill health; Batarfi et al., Citation2012). Some participants suggested they would feel more comfortable attending screening if information and/or the test itself was provided by those who shared their own cultural background (Butler et al., Citation2020; Hamdiui et al., Citation2021; Kwok et al., Citation2011).

Media

Four studies briefly mentioned the influence of media on participation (Ogunsiji et al., Citation2013; Batarfi, Citation2012; Marlow et al., Citation2015; Jackowska et al., Citation2012). Participants felt cervical screening related campaigns in public places, and human-interest stories had a beneficial effect, raising awareness and encouraging women to participate in routine cervical screening. The media focus on Jade Goody, a celebrity who died from cervical cancer in 2009, was mentioned by both migrant and native women in two studies (Marlow et al., Citation2015; Jackowska et al., Citation2012); participants felt this highlighted both the importance of screening attendance and also the potential seriousness of cervical cancer if left undetected.

Discussion

The present review aimed to systematically identify and synthesise qualitative research that outlines factors influencing routine cervical screening participation, specifically within underserved women. Overall, 24 studies were synthesised in line with the principles of Framework Synthesis (Thomas et al., Citation2017). Dahlgren and Whitehead’s (Citation1991) social model of health was used as the initial conceptual framework for the analysis. Synthesis of existing literature resulted in four over-arching levels of influence, 1) The Individual, 2) Social Context, 3) The Healthcare Environment and 4) Wider Society. The resulting conceptual framework therefore presents cervical screening participation within the wider context of participant’s everyday lives, with sub-themes demonstrating the complexity of factors contributing to underserved women’s engagement in routine cervical screening.

The findings reported within this review are reflective of the wider cancer screening literature which considers determinants of participation at population level (Chorley et al., Citation2017; Young et al., Citation2018). However, the current synthesis goes further to highlight the relevance of these determinants for traditionally underserved women who are least likely to attend routine cervical screening. Situating these determinants within an adapted version of Dahlgren and Whitehead’s (Citation1991) Social Model of Health moves away from an over-focus on individual level barriers (e.g., attitudes, beliefs and emotions), also highlighting the social, cultural and environmental layers of influence that extend beyond the individual in influencing participation. For example, the healthcare environment was, unsurprisingly, a strong influence on women’s screening participation, with several barriers identified at this level including poor continuity of care, negative past experiences of screening, practical difficulties accessing services, increased levels of mistrust and impersonal patient-provider relationships. Moreover, participant’s social context had the potential to facilitate screening uptake, with supportive social networks acting as a source of encouragement, reassurance, and information for women. Without these supportive social networks, participants were often unfamiliar with the screening process, which in turn increased negative emotions and attitudes towards the test. In short, these findings support the belief that determinants of screening participation should not be considered in isolation (Oscarsson et al., Citation2008; Plourde et al., Citation2016; von Wagner et al., Citation2011). For example, aiming to tackle embarrassment, fear or negative attitudes towards screening may be partially effective but unlikely to address inequalities in screening participation without a consideration of the broader sociocultural context surrounding specific underserved groups (Sorensen et al., Citation2003; von Wagner et al., Citation2011; Craig et al., Citation2018).

Whilst those from a broad range of social positions may also experience barriers identified in the present review (e.g., unsupportive family members/friends, low perceived risk of cervical cancer or feelings of embarrassment) (Chorley et al., Citation2017; Plourde et al., Citation2016; Bukowska-Durawa & Luszczynska, Citation2014), this synthesis considers the additional structural and organisational barriers that are present for those in disadvantaged social positions. As such, non-participation within underserved women is often a result of multiple barriers at a number of different levels. The accumulation or ‘clustering’ of barriers within disadvantaged populations has been previously discussed as a mechanism by which social gradients in health occur (Dahlgren, Citation2007; Diderichsen et al., Citation2001). However, this is the first study to the authors’ knowledge which puts forward this argument to account for the persistent inequalities observed within cervical screening participation.

Strengths and limitations

The present review is the first to synthesise qualitative literature which identifies determinants of routine, population-wide cervical screening participation within underserved women (specifically those from ethnic minority groups and those living within areas of high deprivation). The findings of this review demonstrate not only the range of determinants that influence screening participation in underserved women, but importantly, situates these determinants within a well-established theoretical framework, and emphasises interrelationships between factors.

Despite these strengths, this review should be considered alongside its limitations. As indicated above, underserved populations are diverse. Study samples include those from a variety of different cultural and social backgrounds (e.g., Somalian migrants, White British natives, Muslim women and so on). It is also important to emphasise that some of the sociodemographic characteristics discussed here are not mutually exclusive (e.g. participants of ethnic minority status may, or may not, experience economic disadvantage). As such, some of the factors discussed may be more relevant to some groups than others. Nonetheless, our intention was to present an overview of literature tailored toward the perspectives of those who traditionally experience difficulty accessing healthcare services and highlight key commonalities within these groups. These findings should therefore be valuable in providing a foundation from which further, more specific, insight can be developed.

It is also of note that the present findings synthesised very few studies, particularly in relation to area-level deprivation (n = 2). Thus, the results reported here may not necessarily be fully representative of the wider population of underserved women. For example, although there is much literature to suggest that factors such as living and working conditions can encourage healthy behaviours (Lovell & Bibby, Citation2018; Short & Mollborn, Citation2015), these factors were relatively unexplored within the present review. In addition, the social context/demographic backgrounds of participants are often not fully described within published literature and as such, it is possible that some relevant studies were missed during the selection process. However, the lack of explicitly relevant literature demonstrates the need for further qualitative work to explore cervical screening participation from the experiences and perspectives of those who are least likely to access the service.

Implications for policy and practice

Whilst organised screening programmes are beneficial in increasing equity of access (Arbyn et al., Citation2010; Elfström et al., Citation2015) these findings suggest that further action is needed to address structural barriers for the most underserved (De Prez et al., Citation2021). There were several barriers identified at the level of the healthcare environment. These included poor continuity of care, negative past experiences of screening, practical difficulties accessing services, increased levels of mistrust and impersonal patient-provider relationships. These findings therefore emphasise the prominent role of policy makers and healthcare providers in ensuring underserved women feel safe, supported and able to participate in cervical screening services. For example, the availability of a female screen-taker greatly influenced participants’ willingness (or ability) to engage in cervical screening. It is already well-established that the potential of a male screen-taker increases cervical screening non-adherence (Leinonen et al., 2017). Whilst women have a right to request a female practitioner for any intimate or invasive procedure, this right may be difficult to exercise for underserved women who often have poor communication with healthcare providers (Sheppard et al., Citation2011; Moss et al., Citation2016). As such, healthcare providers should go further than simply implementing female screen-takers as standard, they should also aim to increase awareness of female screen-takers for those who may be unfamiliar with standard practice (e.g. migrant populations).

Patient-provider relationships also appeared to be particularly influential in determining screening participation and has been previously cited as one of the strongest modifiable factors to encourage cancer screening behaviour (Peterson et al., Citation2016). Within the present review, a good rapport and feeling listened to during past appointments reduced anxiety surrounding the test, encouraging women to attend. Conversely, those who had negative interpersonal experiences with healthcare staff were understandably reluctant to engage with future cervical screening. In line with this, the present review suggests that a focus on increasing relational quality and screening related conversations between patients and providers would positively influence engagement with cervical screening within under-served women (De Prez et al., Citation2021). This is also in line with previous evidence which suggests that it is not sufficient to simply increase patient-provider communication when attempting to encourage cancer screening participation; the quality of such interactions are key (Peterson et al., Citation2016). This in turn also emphasises the need to prioritise culturally sensitive communication strategies and tools when discussing and delivering cervical screening. This may be particularly important within the UK healthcare context given evidence that UK health services often do not meet the needs of culturally diverse groups (Salway et al., Citation2016; George et al., Citation2015).

Recommendations for future research

The current review presents a number of avenues for researchers to pursue. In the first instance, it is clear that there is a paucity of qualitative evidence exploring the experiences and perspectives of routine cervical screening participation, in relation to those living within areas of high relative deprivation. Developing this body of evidence would allow for further exploration of observed uptake inequalities and encourage identification of suitable targets for intervention. As socioeconomically disadvantaged groups are often described as ‘hard-to-reach’, it is also recommended that researchers develop acceptable strategies for connecting with socioeconomically disadvantaged groups within screening related research (Bonevski et al., Citation2014).

The present findings also indicate that cervical screening participation is a result of a wide range of influences, indicating that more distal factors such as social context can indirectly increase likelihood of engagement. Whilst the importance of social determinants on health behaviours is widely known (Short & Mollborn, Citation2015), this is relatively unexplored in relation to cervical screening participation. As such, it is recommended that further research is conducted to explore individual’s social, economic and environmental contexts in conjunction with cancer screening behaviours. This may be particularly important in light of increasing health inequality and challenges to healthcare access, which have occurred as a result of the Coronavirus disease 2019 (i.e. COVID-19) pandemic since this study was conducted (Bambra et al., Citation2021). Understanding screening within this broader societal context would reduce further individualisation of screening behaviour (which is unhelpful to those who face increased structural barriers to engagement which they cannot control) (Holman et al., Citation2018; Baum, Citation2007) and facilitate the development of multi-level interventions. The complex interrelationships between determinants, described within this review, suggests that this approach is likely to be successful in increasing screening participation in underserved populations.

Conclusion

There are distinct and persistent inequalities in cervical screening participation. Women from ethnic minority backgrounds and/or those of low socioeconomic status are currently ‘underserved’ and least likely to attend routine cervical screening. The present review suggests that, for underserved women, screening participation is a result of multi-level, interrelated determinants. Overall, positive patient-provider relationships and peer support may facilitate screening engagement whilst communication and cultural disparities, poor continuity of care and practical barriers often impede service access and exacerbate aversive thoughts, feelings and attitudes toward participation. In contrast to their more affluent or privileged counterparts, underserved women face increased structural barriers to accessing screening services, navigating healthcare systems and services that are not adequate for their, often complex, needs. This review outlines the need to consider cervical screening participation in the wider context of participants’ lives. Furthering exploration of the social determinants of screening participation may result in more effective avenues for intervention development, targeted to those most in need of support.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (48.6 KB)Declaration of interest statement

The authors declare no competing or conflicts of interest

Data availability statement

As a systematic review, no new data was created for this study.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Angela Wearn

Dr Angela Wearn, is a Research Fellow for the NIHR Applied Research Collaboration North East and North Cumbria. Prior to this she completed her PHD in Health Psychology at Northumbria University which focused on understanding and addressing socioeconomic inequalities in cervical screening participation. Her research covers the development and evaluation of complex health interventions, the involvement of the public and communities in health research and preventative health behaviour change.

Lee Shepherd

Dr Lee Shepherd, is a Senior Lecturer in Psychology at Northumbria University. He undertakes research looking into the role of emotions in predicting behaviour. He has researched a variety of behaviours, ranging from group processes and intergroup relations to health screening and organ donation.

References

- A., Addawe, M., B., Mburu, C., A. & Madar, (2018). Abarriers to cervical cancer screening: A qualitative study among Somali women in Oslo Norway. Heal Prim Care, 2(1), 1–5.

- Abdullahi, A., Copping, J., Kessel, A., Luck, M., & Bonell, C. (2009). Cervical screening: Perceptions and barriers to uptake among Somali women in Camden. Public Health, 123(10), 680–685.

- Anaman-Torgbor, J. A., King, J., & Correa-Velez, I. (2017). Barriers and facilitators of cervical cancer screening practices among African immigrant women living in Brisbane, Australia. European Journal of Oncology Nursing: The Official Journal of European Oncology Nursing Society, 31, 22–29.

- Arbyn, M., Anttila, A., Jordan, J., Ronco, G., Schenck, U., Segnan, N., Wiener, H., Herbert, A., & von Karsa, L. (2010). European guidelines for quality assurance in cervical cancer screening. second edition-summary document. Annals of Oncology: Official Journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology, 21(3), 448–458.

- Australian Government Department of Health. (2021). How cervical screening works [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2022 Jan 27]. https://www.health.gov.au/initiatives-and-programs/national-cervical-screening-program/getting-a-cervical-screening-test/how-cervical-screening-works

- Azerkan, F., Sparén, P., Sandin, S., Tillgren, P., Faxelid, E., & Zendehdel, K. (2012). Cervical screening participation and risk among Swedish-born and immigrant women in Sweden. International Journal of Cancer, 130(4), 937–947. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.2608421437898

- Azerkan, F., Widmark, C., Sparén, P., Weiderpass, E., Tillgren, P., & Faxelid, E. (2015). When life got in the way: How Danish and Norwegian immigrant women in Sweden reason about cervical screening and why they postpone attendance. PLoS One, 10(7), e0107624. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0107624

- Bambra, C., Gibson, M., Sowden, A., Wright, K., Whitehead, M., & Petticrew, M. (2010). Tackling the wider social determinants of health and health inequalities: Evidence from systematic reviews. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 64(4), 284–291. [Internet]. [cited 2021 Sep. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC2921286/.

- Bambra, C., Smith, K., & Lynch, J. (2021). The unequal pandemic: COVID-19 and health inequalities (pp. 1–184). Policy Press.

- Batarfi, N. S. (2012). Women’s experiences, barriers, and facilitators when accessing breast and cervical cancer screening services. University of York.

- Baum, F. (2007). Cracking the nut of health equity: Top down and bottom up pressure for action on the social determinants of health. Promotion & Education, 14(2), 90–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/10253823070140022002

- Bonevski, B., Randell, M., Paul, C., Chapman, K., Twyman, L., Bryant, J., Brozek, I., & Hughes, C. (2014). Reaching the hard-to-reach: A systematic review of strategies for improving health and medical research with socially disadvantaged groups. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 14(1), 42–2018.

- Bongaerts, T. H., Büchner, F. L., Middelkoop, B. J., Guicherit, O. R., & Numans, M. E. (2020). Determinants of (non-)attendance at the Dutch cancer screening programmes: A systematic review. Journal of Medical Screening, 27(3), 121–129.

- Bukowska-Durawa, A., & Luszczynska, A. (2014). Cervical cancer screening and psychosocial barriers perceived by patients. A systematic review. Wspolczesna Onkol, 18(3), 153–159. [Internet]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25520573] [25520573]

- Butler, T. L., Anderson, K., Condon, J. R., Garvey, G., Brotherton, J. M. L., Cunningham, J., Tong, A., Moore, S. P., Maher, C. M., Mein, J. K., Warren, E. F., & Whop, L. J. (2020). Indigenous Australian women’s experiences of participation in cervical screening. PLoS One, 15(6), e0234536. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0234536

- Cadman, L., Ashdown-Barr, L., Waller, J., & Szarewski, A. (2015). Attitudes towards cytology and human papillomavirus self-sample collection for cervical screening among Hindu women in London, UK: A mixed methods study. The Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care, 41(1), 38–47.

- Cadman, L., Waller, J., Ashdown-Barr, L., & Szarewski, A. (2012). Barriers to cervical screening in women who have experienced sexual abuse: An exploratory study. The Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care, 38(4), 214–220.

- Cancer Research UK. Cervical cancer statistics. (2017). [Internet]. [cited 2020 Sep 11]. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/cervical-cancer

- Chan, D. N. S., & So, W. K. W. (2017). A systematic review of the factors influencing ethnic minority women’s cervical cancer screening behavior: From intrapersonal to policy level. Cancer Nursing, 40(6), E1–30.

- Chiu, L. F., Heywood, P., Jordan, J., McKinney, P., & Dowell, T. (1999). Balancing the equation: The significance of professional and lay perceptions in the promotion of cervical screening amongst minority ethnic women. Critical Public Health, 9(1), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581599908409216

- Chorley, A. J., Marlow, L. A. V., Forster, A. S., Haddrell, J. B., & Waller, J. (2017). Experiences of cervical screening and barriers to participation in the context of an organised programme: A systematic review and thematic synthesis. Psycho-oncology, 26(2), 161–172.

- Craig, P., Ruggiero, E., Di, Frohlich Kl, Mykhalovskiy, E., White, M., & Campbell, R. (2018). Taking account of context in population health intervention research: Guidance for producers, users and funders of research. [Internet]. UK. [cited 2020 Jul 29]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3310/CIHR-NIHR-01

- Cumpston, M., Chandler. (2020). Updating a review (Chapter IV). In J. P. Higgins, J. Thomas, J. Chandler, M. Cumpston, T. L, & M. Page (Eds.), Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Cochrane. [cited 2021 Jan 6]. www.traning.cochrane.org/handbook

- Dahlgren, W. (2007). European strategies for tackling social inequities in health: Levelling up Part 2. [Internet]. WHO, Regional Office for Europe.; [cited 2019 Jul 12]. Available from: www.euro.who.int

- Dahlgren, G., & Whitehead, M. (1991). Policies and strategies to promote social equity in health Background document to WHO: Strategy paper (Vol. 14, pp. 67). Institute for Future Studies. http://ideas.repec.org/p/hhs/ifswps/2007_014.html.

- Dalton, J., Booth, A., Noyes, J., & Sowden, A. J. (2017 [cited 2021 Sep 2). Potential value of systematic reviews of qualitative evidence in informing user-centered health and social care: Findings from a descriptive overview. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 88, 37–46. [Internet]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.04.020

- De Prez, V., Jolidon, V., Willems, B., Cullati, S., Burton-Jeangros, C., & Bracke, P. (2021). Cervical cancer screening programs and their context-dependent effect on inequalities in screening uptake: A dynamic interplay between public health policy and welfare state redistribution. International Journal for Equity in Health, 20(1) [Internet]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-021-01548-6

- Diderichsen, F., Evans, T., & Whitehead, M. (2001). The social basis of disparities in health. In T. Evans, M. Whitehead, F. Diderichsen, A. Bhuiya, M. Wirth (Eds.), Challenging inequities in health: From ethics to action (pp. 12–23). Oxford University Press.

- Douglas, E., Waller, J., Duffy, S. W., & Wardle, J. (2016). Socioeconomic inequalities in breast and cervical screening coverage in England: Are we closing the gap? Journal of Medical Screening, 23(2), 98–103.

- Dugué, P.-A., Lynge, E., & Rebolj, M. (2014). Mortality of non-participants in cervical screening: Register-based cohort study. International Journal of Cancer, 134(11)

- Elfström, K. M., Arnheim-Dahlström, L., Von Karsa, L., & Dillner, J. (2015). Cervical cancer screening in Europe: Quality assurance and organisation of programmes. European Journal of Cancer (Oxford, England: 1990), 51(8), 950–968.

- Garside, R. (2014). Should we appraise the quality of qualitative research reports for systematic reviews, and if so, how? Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research, 27(1), 67–79. [Internet]. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs https://doi.org/10.1080/13511610.2013.777270

- Gele, A. A., Qureshi, S. A., Kour, P., Kumar, B., & Diaz, E. (2017). Barriers and facilitators to cervical cancer screening among Pakistani and Somali immigrant women in Oslo: A qualitative study. International Journal of Women’s Health, 9(9), 487–496. Jul

- George, R. E., Thornicroft, G., & Dogra, N. (2015). Exploration of cultural competency training in UK healthcare settings: A critical interpretive review of the literature. Divers Equal Heal Care, 12(3), 104–115.

- Hamdiui, N., Marchena, E., Stein, M. L., van Steenbergen, J. E., Crutzen, R., van Keulen, H. M., Reis, R., van den Muijsenbergh, M. E. T. C., & Timen, A. (2021). Decision-making, barriers, and facilitators regarding cervical cancer screening participation among Turkish and Moroccan women in the Netherlands: A focus group study. Ethnicity & Health, 0(0), 1–19. [Internet]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2020.1863921

- Harder, E., Juul, K. E., Jensen, S. M., Thomsen, L. T., Frederiksen, K., & Kjaer, S. K. (2018). Factors associated with non-participation in cervical cancer screening: A nationwide study of nearly half a million women in Denmark. Preventive Medicine, 111, 94–100.

- Holman, D., Lynch, R., & Reeves, A. (2018). How do health behaviour interventions take account of social context? A literature trend and co-citation analysis. Health (London, England: 1997), 22(4), 389–410. [Internet]. Aug 14]Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459317695630

- Idehen, E. E., Koponen, P., Härkänen, T., Kangasniemi, M., Pietilä, A. M., & Korhonen, T. (2018). Disparities in cervical screening participation: A comparison of Russian, Somali and Kurdish immigrants with the general Finnish population. International Journal for Equity in Health, 17(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-018-0768-2

- Idehen, E. E., Pietilä, A. M., & Kangasniemi, M. (2020). Barriers and facilitators to cervical screening among migrant women of African origin: A qualitative study in Finland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health., 17(20), 1–20.

- Jackowska, M., Von Wagner, C., Wardle, J., Juszczyk, D., Luszczynska, A., & Waller, J. (2012). Cervical screening among migrant women: A qualitative study of Polish, Slovak and Romanian women in London, UK. The Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care, 38(4), 229–238.

- Jansen, E. E. L., Zielonke, N., Gini, A., Anttila, A., Segnan, N., Vokó, Z., Ivanuš, U., McKee, M., de Koning, H. J., de Kok, I. M. C. M, & EU-TOPIA Consortium. (2020). Effect of organised cervical cancer screening on cervical cancer mortality in Europe: A systematic review. European Journal of Cancer (Oxford, England: 1990), 127, 207–223.

- Johnson, C. E., Mues, K. E., Mayne, S. L., & Kiblawi, A. N. (2008). Cervical cancer screening among immigrants and ethnic minorities. Journal of Lower Genital Tract Disease, 12(3), 232–241. [18596467]

- Kwok, C., White, K., & Roydhouse, J. K. J. K. (2011). Chinese-Australian women’s knowledge, facilitators and barriers related to cervical cancer screening: A qualitative study. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 13(6), 1076–1083.

- Lee, S.-Y. (2015). Cultural factors associated with breast and cervical cancer screening in Korean American women in the US: An integrative literature review. Asian Nursing Research, 9(2), 81–90. PMC] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anr.2015.05.00326160234

- Leinonen, M. K., Campbell, S., Klungsøyr, O., Lönnberg, S., Hansen, B. T. B. T., & Nygård, M. (2017). Personal and provider level factors influence participation to cervical cancer screening: A retrospective register-based study of 1.3 million women in Norway. Preventive Medicine, 94, 31–39. [Internet]. Jan 1 [cited 2019 Aug 7]Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0091743516303735

- Logan, L., & McIlfatrick, S. (2011). Exploring women’s knowledge, experiences and perceptions of cervical cancer screening in an area of social deprivation. European Journal of Cancer Care, 20(6), 720–727.

- Lorenc, T., Petticrew, M., Welch, V., & Tugwell, P. (2013). What types of interventions generate inequalities? Evidence from systematic reviews. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 67(2), 190–193.

- Lovell, B., Wetherell, M. A., & Shepherd, L. (2015). Barriers to cervical screening participation in high-risk women. Journal of Public Health, 23(1), 57–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-014-0649-0

- Lovell, N., & Bibby, J. (2018). What makes us healthy? An introduction to the social determinants of health. [Internet]. London; Available from: https://www.health.org.uk/sites/default/files/What-makes-us-healthy-quick-guide.pdf

- Marlow, L., McBride, E., Varnes, L., & Waller, J. (2019). Barriers to cervical screening among older women from hard-to-reach groups: A qualitative study in England. BMC Women’s Health, 19(1), 38.

- Marlow, L., Waller, J., & Wardle, J. (2015). Barriers to cervical cancer screening among ethnic minority women: A qualitative study. Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care, 41(4), 248–254. https://doi.org/10.1136/jfprhc-2014-101082

- Marlow, L., Wardle, J., & Waller, J. (2015). Understanding cervical screening non-attendance among ethnic minority women in England. British Journal of Cancer, 113(5), 833–839.

- Marmot, M., Allen, J., Goldblatt, P., Boyce, T., McNeish, D. & Grady, M ( 2010). The Marmot review: Fair society, healthy lives. [Internet].[cited 2019 Jul 10]. http://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/fair-society-healthy-lives-the-marmot-review/fair-society-healthy-lives-full-report-pdf.pdf

- McGeechan, G. J., Byrnes, K., Campbell, M., Carthy, N., Eberhardt, J., Paton, W., Swainston, K., & Giles, E. L. (2021). A systematic review and qualitative synthesis of the experience of living with colorectal cancer as a chronic illness. Psychology & Health, 0(0), 1–25. [Internet]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2020.1867137

- McGill, R., Anwar, E., Orton, L., Bromley, H., Lloyd-Williams, F., O’Flaherty, M., Taylor-Robinson, D., Guzman-Castillo, M., Gillespie, D., Moreira, P., Allen, K., Hyseni, L., Calder, N., Petticrew, M., White, M., Whitehead, M., & Capewell, S. (2015). Are interventions to promote healthy eating equally effective for all? Systematic review of socioeconomic inequalities in impact Health behavior, health promotion and society. BMC Public Health [Internet], 15(1), 457.

- Moser, K., Patnick, J., & Beral, V. (2009). Inequalities in reported use of breast and cervical screening in Great Britain: Analysis of cross sectional survey data. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed), 338, b2025.

- Moss, J. L., Gilkey, M. B., Rimer, B. K., & Brewer, N. T. (2016). Disparities in collaborative patient-provider communication about human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 12(6), 1476–1483. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2015.1128601

- NHS. (2020). What is cervical screening? [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020 Aug 20]. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/cervical-screening/

- Office for National Statistics. (2018). People living in deprived neighbourhoods [Internet]. [cited 2019 Dec 3]. https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/uk-population-by-ethnicity/demographics/people-living-in-deprived-neighbourhoods/latest

- Ogunsiji, O., Wilkes, L., Peters, K., & Jackson, D. (2013). Knowledge, attitudes and usage of cancer screening among West African migrant women. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 22(7–8), 1026–1033.

- Omolo, D. (2019). The uptake of pap smear screening among Kenyan migrants in the Netherlands: A qualitative study [Internet]. Available from: https://thesis.eur.nl/pub/51368/Omolo-Deborah_MA2018_19_SJP.pdf.

- Oscarsson, M. G., Wijma, B. E., & Benzein, E. G. (2008). I do not need to. I do not want to. I do not give it priority.” Why women choose not to attend cervical cancer screening. Heal Expect, 11(1).

- Parajuli, J., Horey, D., & Avgoulas, M. I. (2020). Perceived barriers to cervical cancer screening among refugee women after resettlement: A qualitative study. Contemporary Nurse, 56(4), 363–375.

- Patel, H., Sherman, S. M., Tincello, D., & Moss, E. L. (2020). Awareness of and attitudes towards cervical cancer prevention among migrant Eastern European women in England. Journal of Medical Screening, 27(1), 40–47.

- Peters, K. (2010). Reasons why women choose a medical practice or a women’s health centre for routine health screening: Worker and client perspectives. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 19(17–18), 2557–2564. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03245.x

- Peterson, E. B., Ostroff, J. S., DuHamel, K. N., D’Agostino, T. A., Hernandez, M., Canzona, M. R., & Bylund, C. L. (2016). Impact of provider-patient communication on cancer screening adherence: A systematic review. Preventive Medicine, 93, 96–105.

- Plourde, N., Brown, H. K., Vigod, S., & Cobigo, V. (2016). Contextual factors associated with uptake of breast and cervical cancer screening: A systematic review of the literature. Women & Health, 56(8), 906–925. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2016.1145169

- Public Health England. (2017). Health profile for England: [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2019 Jul 15]. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-profile-for-england

- Public Health England. (2014). National cancer intelligence network. Cancer by deprivation in England incidence. 1996–2010 Mortality, 1997–2011. London, UK.

- Public Health England. (2021). Cervical screening: Programme overview [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2022 Jan 27]. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/cervical-screening-programme-overview

- Salad, J., Verdonk, P., De Boer, F., & Abma, T. A. T. A. (2015). A Somali girl is Muslim and does not have premarital sex. Is vaccination really necessary?” A qualitative study into the perceptions of Somali women in the Netherlands about the prevention of cervical cancer. International Journal for Equity in Health, 14(1), 68. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-015-0198-3

- Salway, S., Mir, G., Turner, D., Ellison, G. T. H., Carter, L., & Gerrish, K. (2016). Obstacles to “race equality” in the english national health service: Insights from the healthcare commissioning arena. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 152, 102–110. [Internet]. Mar 1 [cited 2020 Sep 2]Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC4774476/?report = abstract

- Sandelowski, M., Docherty, S., & Emden, C. (1997). Qualitative metasynthesis: Issues and techniques. Research in Nursing & Health, 20(4), 365–371. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-240X(199708)20:4<365::AID-NUR9>3.0.CO;2-E

- Seers, K. (2014). Correction to what is a qualitative synthesis? Evidence-Based Nursing, 15, 66.