Abstract

Purpose

Research investigating depressive symptoms among cancer patients rarely distinguish between core symptoms of depression (motivational and consummatory anhedonia, and negative affect). This distinction is important as these symptoms may show different trajectories during the course of the illness and require different treatment approaches. The aim of the present study is to investigate fluctuations in core depressive symptoms in patients with colorectal cancer (CRC). It is hypothesized that these core depressive symptoms fluctuate differently during the course of the illness and depend on the phase of the illness (diagnostic, treatment, recovery and palliative phase).

Method

This study is based on data from the PROCORE study. PROCORE is a prospective, population-based study aimed to examine the longitudinal impact of CRC and its treatment on patient-reported outcomes. Eligible patients completed self-report questionnaires (i.e. Multifactorial Fatigue Index, Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale, EORTC-C30) after diagnosis, after surgery and at one and two years after diagnosis.

Results

In total, 539 patients participated of whom 68 have died until March 1ste 2021. Core depressive symptoms fluctuated differently during the course of the illness with higher levels of motivational anhedonia during treatment and palliative phase (P<.001), consummatory anhedonia at the palliative phase (p < .001) and negative affect at the diagnostic and palliative phase (P<.001).

Conclusion

It is important to distinguish between different core depressive symptoms as they fluctuate differently during the course of an illness like CRC. The various depressive symptoms may require a different treatment approach at specific moments during the illness process.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second most common cancer and one of the deadliest cancer types. In Europe 43.000 people die of CRC each year (Dekker et al., Citation2019; Ferlay et al., Citation2015). Health related quality of life is negatively affected by CRC (Flyum et al., Citation2021; Jansen et al., Citation2010) and depressive symptoms are among the most frequently reported complaints when confronted with CRC (Hartung et al., Citation2017). However, depressive symptoms come in various forms and ‘depression’ is a heterogeneous construct (Fried, Citation2015). According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-Fifth Edition, the core depressive symptoms are anhedonia and depressed mood (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2022). This distinction is important as the core depressive symptoms may have their own etiology and require different therapeutic approaches (Fried, Citation2015).

Anhedonia is defined as ‘markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all, or almost all, activities of the day’. Thereby, it is important to distinguish between motivational (lack of interest) and consummatory (lack of pleasure) anhedonia (Thomsen, Citation2015; Treadway & Zald, Citation2011). While a lack of interest is likely to result in a lack of pleasurable experiences (van Roekel et al., Citation2019) and vice versa, these types of anhedonia are also distinguishable (Borsini et al., Citation2020). People may experience a lack of interest and feel unmotivated to do things but when doing them they may experience pleasurable emotions. Besides anhedonia, depressed mood is a core symptom. Depressed mood entails more than sadness and despair but also other negative emotions such as anxiety, worry and irritability (Beard et al., Citation2016; Kalin, Citation2020; Solms, Citation2012). Although anhedonia and negative affect are related, they are distinct as people may experience lack of interest and/or pleasure but not feel depressed (Sibitz et al., Citation2010). This distinction is also supported by the notion that anhedonia may need a different treatment approach than negative affect (Treadway & Zald, Citation2011). For example, anhedonia may be more sensitive for treatment techniques aimed at activating reward systems (e.g. goal setting, behavioral activation) and not so much by interventions aimed at reducing negative thoughts and feelings (Craske et al., Citation2016).

Research into depressive symptoms among patients with cancer in general and CRC in particular rarely distinguish between these core symptoms while they may show different trajectories during the course of the illness. Studies investigating trajectories of depressive symptoms in patients with CRC often investigate a single (e.g. consummatory anhedonia or negative affect) (Hart & Charles, Citation2013) or a mixture of symptoms (e.g. distress, heath related quality of life) (Dunn, Ng, Breitbart, et al., Citation2013; Dunn, Ng, Holland, et al., Citation2013; Wheelwright et al., Citation2020). This limits insight in the differences between these core symptoms which is needed to tailor interventions, both in terms of content and timing. Thus far, one study investigated the trajectories of two different symptom clusters in patients with CRC (Ciere et al., Citation2017). This study found that positive affect (which is linked to consummatory anhedonia) and negative affect show different trajectories in the first 18 months after diagnosis, emphasizing the need to distinguish between the different depressive symptoms. Moreover, most longitudinal studies (Dunn, Ng, Holland, et al., Citation2013; Occhipinti et al., Citation2015; Qaderi et al., 2021; Shaffer et al., Citation2016), including those by Ciere et al. (2017), link assessment points to the time passed since diagnosis. These results are difficult to interpreted and are often of limited clinical value as the situation at a specific moment in time after diagnosis may be completely different for different patients (Henselmans et al., Citation2010). Therefore, in the present study we will look at depressive symptoms at various meaningful illness related phases.

For patients with cancer, the patient journey consists of several different phases including the diagnostic phase, treatment phase, follow-up phase and palliative phase. Each phase will impose its own challenges, demands and needs for the patient, and may be associated with different depressive symptoms. While for different types of cancer the patient journey will vary there are also similarities. The diagnostic phase likely involves high levels of negative affect (Brocken et al., Citation2012; Montgomery & McCrone, Citation2010) as it is a very uncertain period with little comfort and reassurance. Negative affect is, however, likely to decrease during treatment (Kant et al., Citation2018) and follow-up (Ciere et al., Citation2017; Henselmans et al., Citation2010; Hinnen et al., Citation2008) as most patients will be hopeful, supported and able to down-regulate their emotions. In contrast, during the treatment phase, anhedonia (lack of interest, apathy and pleasure) may increase due to the physical and functional impairment (e.g. food intake) and complaints (e.g. pain, fatigue) as a result of the anti-cancer treatment (Cabilan & Hines, Citation2017). This is in line with one of the few studies investigating anhedonia in patients with cancer (Sharpley et al., Citation2013). This study showed that anhedonia was more prevalent than depressed mood in prostate cancer patients of whom most were undergoing treatment. For CRC, treatment almost always involves surgery to remove (part of) the bowel and may be accompanied by radiation or (neo)adjuvant chemotherapy. During follow-up, most patients will once again expand their activities and become more engaged in the world around and consequently motivational and consummatory anhedonia is likely to decrease. When, instead of recovery, patients enter palliative phase and have to deal with the end of life, negative affect and anhedonia can be expected to be high due to the increasing physical and emotional burden (de Boer et al., Citation2020; Hotopf et al., Citation2002; Sewtz et al., Citation2021; Wilson et al., Citation2007).

The aim of the present study is to investigate fluctuations in anhedonia (lack of interest and lack of pleasure) and negative affect in patients with CRC. It is hypothesized that these core depressive symptoms fluctuate differently and that levels depend on the phase of the illness (diagnostic, treatment, recovery and palliative phase). That is, anhedonia may be especially prevalent at the end of treatment and when patients have to deal with the end of life, but not so much during the diagnostic phase and during follow-up. In contrast, negative affect may be highest after diagnosis and in the palliative phase, but not so much at the end of treatment and during follow-up. Moreover, we will investigate the percentage of patients reporting elevated levels of anhedonia and negative affect at the different phases.

Better insight in fluctuations of the different core depressive symptoms as well as the percentage of patients reporting elevated levels of anhedonia and negative affect will provide necessary information to provide timely and tailored interventions.

Methods

Setting and participants

This study is based on data from the PROCORE study. PROCORE is a prospective, population-based study aimed to examine the longitudinal impact of CRC and its treatment on patient-reported outcomes. Details of the data collection have been described elsewhere (Bonhof, van de Poll-Franse, Wasowicz, et al., Citation2021). In brief, data was collected through PROFILES, a registry for the physical and psychosocial impact of cancer and its treatment (van de Poll-Franse et al., 2011). PROFILES is linked to the Netherlands Cancer Registry (NCR) that collects clinical data from all newly diagnosed cancer patients in the Netherlands (Nederlandse Kankerregistratie). Recruitment for PROCORE took place at four hospitals in the Netherlands: Elisabeth-TweeSteden hospital, Catharina hospital, Elkerliek hospital, and Máxima Medical Centre. All patients newly diagnosed with primary CRC between January 2016 and January 2019 were approached and, if eligible, included shortly after diagnosis (i.e. before start of treatment). Those previously diagnosed with cancer (except basal skin cell carcinoma), those with cognitive impairment, and those unable to read or write Dutch, were excluded. In practice, some patients who were previously diagnosed with cancer and those who already started treatment were included. Parallel to previous publications based on the PROCORE dataset (Bonhof, van de Poll-Franse, Wasowicz, et al., Citation2021; Trompetter et al., Citation2022) patients were excluded for analysis if they (1) were previously diagnosed with cancer and (2) already started treatment before inclusion. In this publication, we also excluded patients who did not underwent surgery. A flowchart of the PROCORE study has been published previously (Bonhof, Van de Poll-Franse, de Hingh, et al., Citation2021).

Data collection

Eligible patients were invited by their research nurse or case manager and received an information package about the study. The package included an information letter, informed consent form, and the first questionnaire (T1). Follow-up questionnaires (online or on paper) were sent four weeks after surgery (T2), and one (T3) and two years (T4) after diagnosis. In case of non-respondence, reminders were sent after two weeks. PROCORE was approved by the certified Medical Ethics Committee ‘Medical research Ethics Committees United’ (registration number: NL51119.060.14).

Illness phase

For survivors, T1 is considered the diagnostic phase, T2 the treatment phase, and T3 and T4 the follow-up phase. For patients who died, the last questionnaire completed is used to represent the palliative phase (T5). Thus, if a patient died after treatment and completed T1 and T2, T2 was included in this study and renumbered as T5.

Study measures

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics

Patients’ sociodemographic (i.e. age, sex) and clinical (i.e. cancer type, clinical stage, treatment) information was available from the NCR (Nederlandse Kankerregistratie). Information on educational level was derived from the questionnaire.

Vital status

Survival status on March 1st 2021 was obtained by merging data from the Central Bureau for Genealogy to our dataset.

Core depressive symptoms

Motivational anhedonia was assessed with the 4-item reduced motivation subscale (e.g. I have a lot of plans, I don’t feel like doing anything) from the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI) (Smets et al., Citation1995). The MFI consists of five scales and responses are ranged on a 5-point scale. Items may be coded reversely to indicate that higher scores indicate reduced motivation (i.e. higher motivational anhedonia). A cut-off of 12 is used to represent elevated levels of motivational anhedonia (Thong et al., Citation2018). The MFI has been validated for patients with cancer (Schneider, Citation1998) and the motivational subscale is found to be moderately correlated with symptoms of depression and anxiety in patients with cancer (Smets et al., Citation1996). In the present study Cronbach’s alpha was .75 (T1), .76 (T2), .75 (T3) and .77 (T4).

Consummatory anhedonia was assessed with the 7-item depression subscale (e.g. I still enjoy the things I used to enjoy, I can enjoy a good book or radio/TV program) of the Hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) (Spinhoven et al., Citation1997; Zigmond & Snaith, Citation1983). The main construct assessed by the HADS-D is consummatory anhedonia (Langvik et al., Citation2016; Smith et al., Citation2002). The questions can be answered on a four-point Likert-scale and the total score for the depression scale can range from 0 to 21. The cut-off value for consummatory anhedonia was indicated by a score ≥8 (Borsini et al., Citation2020; Kalin, Citation2020; Solms, Citation2012). In the present study Cronbach’s alpha was .83 (T1), .84 (T2), .82 (T3) and .85 (T4).

Negative affect was assessed with the 4-item emotional functioning subscale of the EORTC QLQ-C30 (version 3.0) (Aaronson et al., 1993). The items asses feeling tense, worrying, feeling depressed, and being irritable.

This questionnaire contains five functional scales, a global quality of life scale, three symptom scales, and six single items. Each item is scored on a four-point Likert-scale. Scores were linear transformed to a 0-100 scale (Fayers, Citation2001) . A lower score on the emotional functional scale means higher negative affect. A cut-off below 75 is used as an indication for elevated negative affect (Calderon et al., Citation2019; Lidington et al., Citation2022). In the present study Cronbach’s alpha was .86 (T1), .88 (T2), .89 (T3) and .87 (T4).

Statistical analyses

Baseline characteristics were determined for survivors and those who died. Pearson correlations were determined of the various measures at the different assessment point. Mixed models with maximum likelihood estimation and an unstructured covariance matrix with a 2-level structure (time-level and patient-level) was used. Mixed model analyses allow the number of observations per assessment to differ and therefore missing data were not imputed. A sequence of models was fitted to investigate the fluctuations of motivational anhedonia, consummatory anhedonia and negative affect from diagnosis till two years after diagnosis. Whether a more complex model fits the data better was determined based on the Akaike Information Criteria (AIC). First, models with no explanatory variables, only the intercept (i.e. an unconditional model) were calculated to determine the amount of variance at the person and time level. Second, models with only baseline characteristics (age, sex, education level) were calculated. Variables significantly associated with motivational anhedonia, consummatory anhedonia or negative affect were used as covariates in the next models. Next, illness phase as explanatory variable (unconditional growth model) was calculated to determine whether motivational anhedonia, consummatory anhedonia and negative affect differs between diagnostic, treatment, follow-up (one and two years) and palliative phase. Intercept and time were entered both as fixed and random effects as each subject may have its own unique intercept and slope. Regression estimates and 95% confidence interval of fixed effects were presented. A model-based graph was created as an aid to determine how the depressive symptoms develop over time. Finally, the number of patients reporting elevated levels of motivational anhedonia, consummatory anhedonia and negative affect (i.e. emotional functioning) on the different assessment point were calculated. Chi-square statistics was used to investigate differences between the different phases.

Results

Patients’ characteristics at baseline are presented in . Fourteen patients were excluded as they did not receive surgery. In total, 68 patients died between start of the study and March 2021. Ten patients died between inclusion (T1) and treatment (T2), 16 between treatment and one year follow-up (T3), 19 between one and two year follow-up (T4) and 23 after two year follow-up. On average deceased patients, died within one year after completing their final questionnaire (days 339.51, SD =320.27) with a median of 233 days. Moreover, the average time between ending primary treatment and completing follow-up questionnaires was 306.56 (81.86) days for T3 and 673.21 (86.29) days for T4. Correlations between the motivation subscale from the Multidimensional Fatigue Index and the HADS depression subscale at the different assessment point ranged between .59 (p<.001) and .68 (p<.001) indicating a maximum explained variance of 46%. Correlations between motivation subscale from the MFI an the emotional function subscale of the EORTC ranged between .37 (<.001) and .46 (<.001) and between the HADS depression subscale and the emotional function subscale of the EORTC between .54 p (<.001) and .56 (<.001).

Table 1. Patient characteristics at baseline.

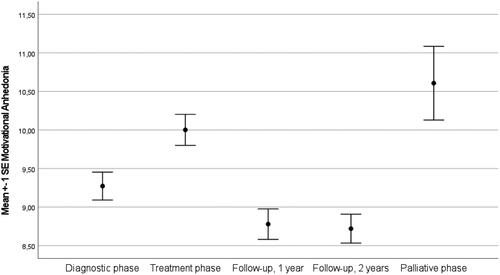

Motivational anhedonia

Intraclass correlation coefficients of the unconditional model showed that 54.3% of the variance was at the person level and the remaining 45.7% was at the time level. These results indicate that scores on motivational anhedonia differed enough between patients and over time to justify a two-level model (AIC = 7707.98). Next, we entered the sociodemographic variables age, sex and education level into the model of which age was significantly related with motivational anhedonia (p < .001). Education level and sex were excluded from further analyses. Moreover, we extended the model by entering illness phase into the model (). This model fitted the data better than the unconditional model (AIC = 7652.90) and showed that motivational anhedonia fluctuated (p < .001) with a mean score of 9.08 (95%CI 8.70-9.46) at T1, 9.87 (95%CI 9.47-10.26) at T2, 8.61 (95%CI 8.21-9.02) at T3, 8.66 (95%CI 8.25 − 9.07) at T4 and 10.67 (95%CI 9.75 − 11.60) at T5 (). Moreover, the prevalence of elevated motivational anhedonia differed at the different assessment points (See ). Elevated levels of motivational anhedonia are most prevalent after surgery and in the palliative phase.

Table 2. Fixed effects of age and illness phase on motivational anhedonia.

Table 3. Elevated scores at the different phases.

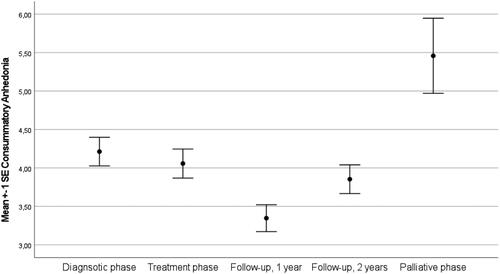

Consummatory anhedonia

Intraclass correlation coefficients of the unconditional model showed that 65.2% of the variance was at the person level and the remaining 34.8% was at the time level (AIC = 7183.71). Next, we entered the sociodemographic variables age, sex and education level into the model. These variables were not associated with consummatory anhedonia and excluded from further analyses. Moreover, we extended the model by entering illness phase into the model. This model () did fit the data better than the unconditional model (AIC = 7159. 51) and show the highest level of consummatory anhedonia in the palliative phase (). Similarly, the highest percentage of patients with elevated consummatory anhedonia was found among those in palliative phase ().

Table 4. Fixed effects of illness phase on consummatory anhedonia.

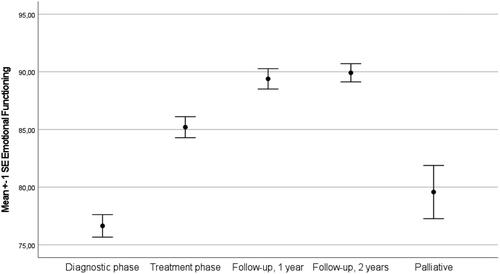

Negative affect

Intraclass correlation coefficients of the unconditional model showed that 45.9% of the variance was at the person level and the remaining 54.1% was at the time level, supporting a two level model (AIC = 12316.17). Next, we entered the sociodemographic variables sex, education level and age into the model which were all found to be significantly related with emotional functioning (p = .03, p =.02, p < .01). Moreover, we extended the model by entering illness phase into the model. This model fitted the data better than the unconditional model (AIC = 12008.79) and showed that emotional functioning fluctuated between the different phases (p < .001) (see ). In the diagnostic and palliative phase negative affect was highest (i.e. emotional function lowest). Similarly, the prevalence of elevated negative affect was highest at diagnosis and in patients in the palliative phase (see ).

Discussion

As expected, motivational anhedonia was found to be higher in the treatment and palliative phase and lower in the diagnostic and follow-up phase. Consummatory anhedonia (i.e. lack of pleasure) was found to be rather low and stable over time. Results showed that patients in the palliative phase reported higher levels of consummatory anhedonia and were more likely to report elevated scores. As expected and in line with previous studies (Mosher et al., Citation2016), negative affect was highest after diagnosis and in the palliative phase and improved during treatment and follow-up. These findings indicate that looking at particular (clusters of) depressive symptoms in patients with (colorectal) cancer may be more informative and clinically relevant than using depression as a single construct (i.e. syndrome). The different core symptoms show their own course which may inform clinicians when and how to intervene. Therefore it is important to understand how these core depressive symptoms are associated with separable emotional-affective networks in the brain (Dantzer, Citation2017; Davidson et al., Citation2002; Panksepp, Citation2010; Zellner et al., Citation2011). Motivational anhedonia has been linked to the SEEKING system (Treadway & Zald, Citation2011). This general-purpose motivational system is the inherent tendency of animals and humans alike to explore the world around (Panksepp, Citation2010). In humans this system generates and sustains curiosity, feeling engaged as well as positive expectations. It is dopamine driven and related with novelty seeking, expansion of activities, curiosity, and development of oneself. Under-arousal of this system results in passivity, apathy, and a lack of interest in the world around (Treadway & Zald, Citation2011). Consummatory anhedonia is linked to the LIKING system which is associated with gratification and feelings of pleasure and the dominant neuropeptide of this system is endorphin. Sustained under-arousal of this system is characterized by a lack of positive affect and pleasure (Solms, Citation2012). Negative affect (e.g. worry, despair, sadness, distress) has been argued to be especially related to the ATTACHMENT (i.e. separation distress) system (Levitan et al., Citation2009; Panksepp, Citation2010). The attachment system is, in children and adults alike, aimed to ensure safety by keeping support givers (e.g. parents, caregivers, romantic partners) close, especially when threatened. This system is dominated by endogenous opioids and oxytocin and will generate high levels of negative affect (e.g. anxiety, despair) when separation looms (e.g. death) or one feels unsupported in times of need (Solms et al., Citation2018).

The present study suggests that the confrontation with an illness like CRC may result in an under- and overactivation of these systems during the illness process. That is, the Seeking and Liking system may become under-activated during the treatment period and/or during the palliative phase. Shielding oneself from the world around and focus attention and energy on the demands of the illness may actually be helpful to endure the emotional and physical burden of anti-cancer treatment and the end of life. Diminished interest and passivity may facilitate this process. Even elevated levels of motivational anhedonia, which were prevalent during the treatment (24.7%) and palliative phase (44.1%), may be an adaptive reaction when the treatment is highly demanding or the illness is in an advanced stage. From an evolutionary perspective the adaptive nature of anhedonia is understandable as it may prevent individuals who are sick and unable to escape danger (e.g. predators) to go out into the world (Solms, Citation2012). From a clinical perspective, validating and normalizing high levels of anhedonia during the treatment and palliative phases may therefore be more helpful than pathologizing. When lack of interest remains elevated during follow-up this may become more problematic. In the present sample, approximately 15% of the survivors reported motivation anhedonia above the cutoff at one and two years after diagnosis. These patients may profit from interventions aimed at activating the seeking system by boosting curiosity, positive expectations, hope and activation (Craske et al., Citation2016). Moreover, given the central role of dopamine within the seeking system it has been recommended to use dopamine active pharmacotherapies such as bupropion for the treatment of motivational anhedonia (Treadway & Zald, Citation2011). Interestingly, bupropion has been suggested as medication for cancer related fatigue (Ashrafi et al., Citation2018; Jim et al., Citation2020) which shows overlap with (motivational) anhedonia. The finding that consummatory anhedonia did not increase during treatment indicates that patients still can enjoy the things they do and the liking system may not be affected. During the palliative phase, a lack of pleasurable experiences was prevalent in a quarter of the patients (26.5%) which seems to mimic the pattern of motivational anhedonia and suggests that the liking system becomes under-aroused. In contrast to the Seeking and Liking systems which may become under-aroused, the present results indicate that the attachment system may become overactivated, especially during the diagnostic and palliative phase in which separation distress may be highest due to the confrontation with death. Moreover, high levels of negative affect at the diagnostic phase, which was found in 26.0% of the patients, may not be pathological perse, as these negative emotions may diminish when treatment starts. This does not mean that interventions during the diagnostic phase may not be helpful for patients to endure their worries and anxieties and promote recovery (Grimmett et al., Citation2022). Heightened levels of negative affect during follow-up was prevalent in 13% of the patients. From an attachment perspective, these high levels of negative affect should be viewed from a relational perspective and may require interventions aimed at promoting felt security, connectedness and support (Mah et al., Citation2020; von Blanckenburg & Leppin, Citation2018). Interestingly, it has been suggested that opioids like morphine which are often used in palliative phase may not only lesson physical pain but also the emotional pain associated with separation (Herman & Panksepp, Citation1978; Panksepp et al., Citation1978).

Moreover, the present study showed that during the diagnostic and treatment phase different core depressive symptoms were prevalent (negative affect and motivational anhedonia, respectively), while during the palliative phase all three core depressive symptoms were present. This is in line with previous studies showing the highest prevalence of major depression in the palliative phase (Walker et al., Citation2013).

The present study has some clear strengths and some limitations. This is the first study investigating various core depressive symptoms in a large population of patients with CRC at different meaningful moments during the illness process including the palliative phase. Although the scales used were correlated, they showed a distinct pattern over time. Information is lacking on the possible psychological or pharmacological treatment of various depressive symptoms among respondents. Although this might have impacted the results of our study by lessening depressive symptoms, enough patients with sufficient depressive symptoms participated in the present study. Future studies in this area should explicitly ask whether participants are receiving some form of psychological treatment. Also, patients lost to follow-up could have stopped participating due to depressive symptoms, which could have led to an underestimation of our findings. Moreover, although time since ending primary treatment was available, patients might have experienced illness recurrence for which they received treatment during follow-up. This information was not available but may have impacted the results. Furthermore, the present results primarily relate to patients with CRC but may also be applicable for a larger population of patients with cancer. Although each type of cancer has its own challenges and demands the patients journey also shows similarities. Whether the present findings are generalizable should be investigated in future studies. Furthermore, in the present study existing data was reanalyzed, limiting the instruments available to assess the core symptoms of depression. Although the instruments used in the present paper are frequently used and well validated, future research may further investigate the validity of this approach and/or use different measures (e.g. clinical interviews). Moreover, future studies may also want to investigate whether clinical factors, other than illness phase, are associated with these core symptoms. Other factors one can think of are fatigue, pain, and inflammation but also the various cancer treatments themselves (e.g. chemotherapy, surgery, immunotherapy) as they may impact anhedonia and negative affect differently ().

Table 5. Fixed effects of demographics, illness phase on emotional functioning.

Conclusion

Based on the present results it could be concluded that it might be helpful for researchers and clinicians not to talk about ‘depression’ or ‘depressive symptoms’ in patients with cancer but distinguish between various core depressive symptoms. Differentiating between the core depressive symptoms may be much more informative as they fluctuate differently over the course of the illness and may require different therapeutic approaches at a specific moments during the illness process.

Statements & declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The PROCORE study was approved by the certified Medical Ethic Committee of Medical research Ethics Committees United (registration number: NL51119.060.14).

List of abbreviations

Colorectal cancer (CRC); Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS); Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI); PROFILES: Patient Reported Outcomes Following Initial treatment and Long term Evaluation of Survivorship.

Data availability

The data is freely available for non-commercial scientific research, subject to study question, privacy and confidentiality restrictions, and registration (www.profilesregistry.nl).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Funding

The present research was supported by the Center of Research on Psychological disorders and Somatic diseases (CoRPS), Tilburg University, the Netherlands; the Netherlands Comprehensive Cancer Organisation, Utrecht, the Netherlands; and an Investment Subsidy Large (2016/04981/ZONMW-91101002) of the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (The Hague, The Netherlands).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aaronson, N. K., Ahmedzai, S., Bergman, B., Bullinger, M., Cull, A., Duez, N. J., Filiberti, A., Flechtner, H., Fleishman, S. B., de Haes, J. C., & Kaasa, S. (1993). The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 85(5), 365–376. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=8433390

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5-TR. American Psychiatric Association Publishing.

- Ashrafi, F., Mousavi, S., & Karimi, M. (2018). Potential role of bupropion sustained release for cancer-related fatigue: A double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention : APJCP, 19(6), 1547–1551. https://doi.org/10.22034/apjcp.2018.19.6.1547

- Beard, C., Millner, A. J., Forgeard, M. J. C., Fried, E. I., Hsu, K. J., Treadway, M. T., Leonard, C. V., Kertz, S. J., & Björgvinsson, T. (2016). Network analysis of depression and anxiety symptom relationships in a psychiatric sample. Psychological Medicine, 46(16), 3359–3369. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291716002300

- Bonhof, C. S., Van de Poll-Franse, L. V., de Hingh, I. H., Nefs, G., Vreugdenhil, G., & Mols, F. (2021). Association between peripheral neuropathy and sleep quality among colorectal cancer patients from diagnosis until 2-year follow-up: Results from the PROFILES registry. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-021-01130-7

- Bonhof, C. S., van de Poll-Franse, L. V., Wasowicz, D. K., Beerepoot, L. V., Vreugdenhil, G., & Mols, F. (2021). The course of peripheral neuropathy and its association with health-related quality of life among colorectal cancer patients. Journal of Cancer Survivorship : Research and Practice, 15(2), 190–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-020-00923-6

- Borsini, A., Wallis, A. S. J., Zunszain, P., Pariante, C. M., & Kempton, M. J. (2020). Characterizing anhedonia: A systematic review of neuroimaging across the subtypes of reward processing deficits in depression. Cognitive, Affective & Behavioral Neuroscience, 20(4), 816–841. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13415-020-00804-6

- Brocken, P., Prins, J. B., Dekhuijzen, P. N., & van der Heijden, H. F. (2012). The faster the better?—A systematic review on distress in the diagnostic phase of suspected cancer, and the influence of rapid diagnostic pathways. Psycho-oncology, 21(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1929

- Cabilan, C. J., & Hines, S. (2017). The short-term impact of colorectal cancer treatment on physical activity, functional status and quality of life: A systematic review. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports, 15(2), 517–566. https://doi.org/10.11124/jbisrir-2016003282

- Calderon, C., Carmona-Bayonas, A., Jara, C., Beato, C., Mediano, M., Ramón y Cajal, T., Carmen Soriano, M., & Jiménez-Fonseca, P. (2019). Emotional functioning to screen for psychological distress in breast and colorectal cancer patients prior to adjuvant treatment initiation. European Journal of Cancer Care, 28(3), e13005. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.13005

- Ciere, Y., Janse, M., Almansa, J., Visser, A., Sanderman, R., Sprangers, M. A. G., Ranchor, A. V., & Fleer, J. (2017). Distinct trajectories of positive and negative affect after colorectal cancer diagnosis. Health Psychology : Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 36(6), 521–528. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000485

- Craske, M. G., Meuret, A. E., Ritz, T., Treanor, M., & Dour, H. J. (2016). Treatment for anhedonia: A neuroscience driven approach. Depression and Anxiety, 33(10), 927–938. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22490

- Dantzer, R. (2017). Role of the kynurenine metabolism pathway in inflammation-induced depression: Preclinical approaches. Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences, 31, 117–138. https://doi.org/10.1007/7854_2016_6

- Davidson, R. J., Pizzagalli, D., Nitschke, J. B., & Putnam, K. (2002). Depression: Perspectives from affective neuroscience. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 545–574. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135148

- de Boer, A. Z., Derks, M. G. M., de Glas, N. A., Bastiaannet, E., Liefers, G. J., Stiggelbout, A. M., van Dijk, M. A., Kroep, J. R., Ropela, A., van den Bos, F., & Portielje, J. E. A. (2020). Metastatic breast cancer in older patients: A longitudinal assessment of geriatric outcomes. Journal of Geriatric Oncology, 11(6), 969–975. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2020.04.002

- Dekker, E., Tanis, P. J., Vleugels, J. L. A., Kasi, P. M., & Wallace, M. B. (2019). Colorectal cancer. Lancet (London, England), 394(10207), 1467–1480. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(19)32319-0

- Dunn, J., Ng, S. K., Breitbart, W., Aitken, J., Youl, P., Baade, P. D., & Chambers, S. K. (2013). Health-related quality of life and life satisfaction in colorectal cancer survivors: Trajectories of adjustment. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 11(1), 46. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-11-46

- Dunn, J., Ng, S. K., Holland, J., Aitken, J., Youl, P., Baade, P. D., & Chambers, S. K. (2013). Trajectories of psychological distress after colorectal cancer. Psycho-oncology, 22(8), 1759–1765. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3210

- Fayers, P. (2001). EORTC QLQ-C30 scoring manual.

- Ferlay, J., Soerjomataram, I., Dikshit, R., Eser, S., Mathers, C., Rebelo, M., Parkin, D. M., Forman, D., & Bray, F. (2015). Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. International Journal of Cancer, 136(5), E359–386. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.29210

- Flyum, I. R., Mahic, S., Grov, E. K., & Joranger, P. (2021). Health-related quality of life in patients with colorectal cancer in the palliative phase: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Palliative Care, 20(1), 144. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-021-00837-9

- Fried, E. I. (2015). Problematic assumptions have slowed down depression research: Why symptoms, not syndromes are the way forward. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 309. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00309

- Grimmett, C., Heneka, N., & Chambers, S. (2022). Psychological interventions prior to cancer surgery: A review of reviews. Current Anesthesiology Reports, 12(1), 78–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40140-021-00505-x

- Hart, S. L., & Charles, S. T. (2013). Age-related patterns in negative affect and appraisals about colorectal cancer over time. Health Psychology : Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 32(3), 302–310. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028523

- Hartung, T. J., Brähler, E., Faller, H., Härter, M., Hinz, A., Johansen, C., Keller, M., Koch, U., Schulz, H., Weis, J., & Mehnert, A. (2017). The risk of being depressed is significantly higher in cancer patients than in the general population: Prevalence and severity of depressive symptoms across major cancer types. European Journal of Cancer (Oxford, England : 1990), 72, 46–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2016.11.017

- Henselmans, I., Helgeson, V. S., Seltman, H., de Vries, J., Sanderman, R., & Ranchor, A. V. (2010). Identification and prediction of distress trajectories in the first year after a breast cancer diagnosis. Health Psychology : Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 29(2), 160–168. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017806

- Herman, B. H., & Panksepp, J. (1978). Effects of morphine and naloxone on separation distress and approach attachment: Evidence for opiate mediation of social affect. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior, 9(2), 213–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/0091-3057(78)90167-3

- Hinnen, C., Ranchor, A. V., Sanderman, R., Snijders, T. A. B., Hagedoorn, M., & Coyne, J. C. (2008). Course of distress in breast cancer patients, their partners, and matched control couples. Annals of Behavioral Medicine : A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, 36(2), 141–148. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-008-9061-8

- Hotopf, M., Chidgey, J., Addington-Hall, J., & Ly, K. L. (2002). Depression in advanced disease: A systematic review Part 1. Prevalence and case finding. Palliative Medicine, 16(2), 81–97. https://doi.org/10.1191/02169216302pm507oa

- Jansen, L., Koch, L., Brenner, H., & Arndt, V. (2010). Quality of life among long-term (≥5 years) colorectal cancer survivors–systematic review. European Journal of Cancer (Oxford, England : 1990), 46(16), 2879–2888. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2010.06.010

- Jim, H. S. L., Hoogland, A. I., Han, H. S., Culakova, E., Heckler, C., Janelsins, M., Williams, G. C., Bower, J., Cole, S., Desta, Z., Babilonia, M. B., Morrow, G., & Peppone, L. (2020). A randomized placebo-controlled trial of bupropion for Cancer-related fatigue: Study design and procedures. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 91, 105976. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2020.105976

- Kalin, N. H. (2020). The critical relationship between anxiety and depression. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 177(5), 365–367. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20030305

- Kant, J., Czisch, A., Schott, S., Siewerdt-Werner, D., Birkenfeld, F., & Keller, M. (2018). Identifying and predicting distinct distress trajectories following a breast cancer diagnosis - from treatment into early survival. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 115, 6–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.09.012

- Langvik, E., Hjemdal, O., & Nordahl, H. M. (2016). Personality traits, gender differences and symptoms of anhedonia: What does the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) measure in nonclinical settings? Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 57(2), 144–151. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12272

- Levitan, R. D., Atkinson, L., Pedersen, R., Buis, T., Kennedy, S. H., Chopra, K., Leung, E. M., & Segal, Z. V. (2009). A novel examination of atypical major depressive disorder based on attachment theory. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 70(6), 879–887. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.07m03306

- Lidington, E., Giesinger, J. M., Janssen, S. H. M., Tang, S., Beardsworth, S., Darlington, A.-S., Starling, N., Szucs, Z., Gonzalez, M., Sharma, A., Sirohi, B., van der Graaf, W. T. A., & Husson, O. (2022). Identifying health-related quality of life cut-off scores that indicate the need for supportive care in young adults with cancer. Quality of Life Research, 31(9), 2717–2727. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-022-03139-6

- Mah, K., Shapiro, G. K., Hales, S., Rydall, A., Malfitano, C., An, E., Nissim, R., Li, M., Zimmermann, C., & Rodin, G. (2020). The impact of attachment security on death preparation in advanced cancer: The role of couple communication. Psycho-oncology, 29(5), 833–840. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5354

- Montgomery, M., & McCrone, S. H. (2010). Psychological distress associated with the diagnostic phase for suspected breast cancer: Systematic review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 66(11), 2372–2390. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05439.x

- Mosher, C. E., Winger, J. G., Given, B. A., Helft, P. R., & O'Neil, B. H. (2016). Mental health outcomes during colorectal cancer survivorship: A review of the literature. Psycho-oncology, 25(11), 1261–1270. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3954

- Nederlandse Kankerregistratie. (2022). Cijfers over Kanker. http://www.cijfersoverkanker.nl/

- Occhipinti, S., Chambers, S. K., Lepore, S., Aitken, J., & Dunn, J. (2015). A longitudinal study of post-traumatic growth and psychological distress in colorectal cancer survivors. PloS One, 10(9), e0139119. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0139119

- Panksepp, J. (2010). Affective neuroscience of the emotional BrainMind: Evolutionary perspectives and implications for understanding depression. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 12(4), 533–545. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2010.12.4/jpanksepp

- Panksepp, J., Herman, B., Conner, R., Bishop, P., & Scott, J. P. (1978). The biology of social attachments: Opiates alleviate separation distress. Biological Psychiatry, 13(5), 607–618.

- Qaderi, S. M., van der Heijden, J. A., Verhoeven, R. H., de Wilt, J. H., Custers, J. A., Beets, G. L., Eric, J. T., Berbée, M., Beverdam, F. H., Blankenburgh, R., & Coene, P. P. L. (2021). Trajectories of health-related quality of life and psychological distress in patients with colorectal cancer: A population-based study. European Journal of Cancer (Oxford, England : 1990), 158, 144–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2021.08.050

- Schneider, R. A. (1998). Concurrent validity of the Beck Depression Inventory and the multidimensional fatigue inventory-20 in assessing fatigue among cancer patients. Psychological Reports, 82(3), 883–886. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1998.82.3.883

- Sewtz, C., Muscheites, W., Grosse-Thie, C., Kriesen, U., Leithaeuser, M., Glaeser, D., Hansen, P., Kundt, G., Fuellen, G., & Junghanss, C. (2021). Longitudinal observation of anxiety and depression among palliative care cancer patients. Annals of Palliative Medicine, 10(4), 3836–3846. https://doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-1346

- Shaffer, K. M., Kim, Y., & Carver, C. S. (2016). Physical and mental health trajectories of cancer patients and caregivers across the year post-diagnosis: A dyadic investigation. Psychology & Health, 31(6), 655–674. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2015.1131826

- Sharpley, C. F., Bitsika, V., & Christie, D. H. (2013). Do prostate cancer patients suffer more from depressed mood or anhedonia? Psycho-oncology, 22(8), 1718–1723. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3203

- Sibitz, I., Berger, P., Freidl, M., Topitz, A., Krautgartner, M., Spiegel, W., & Katschnig, H. (2010). ICD-10 or DSM-IV? Anhedonia, fatigue and depressed mood as screening symptoms for diagnosing a current depressive episode in physically ill patients in general hospital. Journal of Affective Disorders, 126(1-2), 245–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2010.03.023

- Smets, E. M., Garssen, B., Bonke, B., & De Haes, J. C. (1995). The Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI) psychometric qualities of an instrument to assess fatigue. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 39(3), 315–325. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7636775 https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3999(94)00125-O

- Smets, E. M., Garssen, B., Cull, A., & de Haes, J. C. (1996). Application of the multidimensional fatigue inventory (MFI-20) in cancer patients receiving radiotherapy. British Journal of Cancer, 73(2), 241–245. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8546913 https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.1996.42

- Smith, A. B., Selby, P. J., Velikova, G., Stark, D., Wright, E. P., Gould, A., & Cull, A. (2002). Factor analysis of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale from a large cancer population. Psychology and Psychotherapy, 75(Pt 2), 165–176. https://doi.org/10.1348/147608302169625

- Solms, M. (2012). Depression: A neuropsychoanalytic perspective. International Forum of Psychoanalysis, 21(3–4), 207–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/0803706X.2011.631582

- Solms, M., Turnbull, O., & Taylor, F. (2018). The brain and the inner world: An introduction to the neuroscience of subjective experience. Routledge, an imprint of Taylor and Francis.

- Spinhoven, P., Ormel, J., Sloekers, P. P., Kempen, G. I., Speckens, A. E., & Van Hemert, A. M. (1997). A validation study of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in different groups of Dutch subjects. Psychological Medicine, 27(2), 363–370.

- Thomsen, K. R. (2015). Measuring anhedonia: Impaired ability to pursue, experience, and learn about reward. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1409–1409. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01409

- Thong, M. S. Y., Mols, F., van de Poll-Franse, L. V., Sprangers, M. A. G., van der Rijt, C. C. D., Barsevick, A. M., Knoop, H., & Husson, O. (2018). Identifying the subtypes of cancer-related fatigue: Results from the population-based PROFILES registry. Journal of Cancer Survivorship : Research and Practice, 12(1), 38–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-017-0641-0

- Treadway, M. T., & Zald, D. H. (2011). Reconsidering anhedonia in depression: Lessons from translational neuroscience. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 35(3), 537–555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.06.006

- Trompetter, H. R., Bonhof, C. S., van de Poll-Franse, L. V., Vreugdenhil, G., & Mols, F. (2022). Exploring the relationship among dispositional optimism, health-related quality of life, and CIPN severity among colorectal cancer patients with chronic peripheral neuropathy. Supportive Care in Cancer : Official Journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, 30(1), 95–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06352-0

- van de Poll-Franse, L. V., Horevoorts, N., van Eenbergen, M., Denollet, J., Roukema, J. A., Aaronson, N. K., Vingerhoets, A., Coebergh, J. W., de Vries, J., Essink-Bot, M.-L., & Mols, F. (2011). The Patient Reported Outcomes Following Initial treatment and Long term Evaluation of Survivorship registry: Scope, rationale and design of an infrastructure for the study of physical and psychosocial outcomes in cancer survivorship cohorts. European Journal of Cancer (Oxford, England : 1990), 47(14), 2188–2194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2011.04.034

- van Roekel, E., Heininga, V. E., Vrijen, C., Snippe, E., & Oldehinkel, A. J. (2019). Reciprocal associations between positive emotions and motivation in daily life: Network analyses in anhedonic individuals and healthy controls. Emotion (Washington, D.C.), 19(2), 292–300. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000424

- von Blanckenburg, P., & Leppin, N. (2018). Psychological interventions in palliative care. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 31(5), 389–395. https://doi.org/10.1097/yco.0000000000000441

- Walker, J., Holm Hansen, C., Martin, P., Sawhney, A., Thekkumpurath, P., Beale, C., Symeonides, S., Wall, L., Murray, G., & Sharpe, M. (2013). Prevalence of depression in adults with cancer: A systematic review. Annals of Oncology : Official Journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology, 24(4), 895–900. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mds575

- Wheelwright, S., Permyakova, N. V., Calman, L., Din, A., Fenlon, D., Richardson, A., Sodergren, S., Smith, P. W. F., Winter, J., & Foster, C. (2020). Does quality of life return to pre-treatment levels five years after curative intent surgery for colorectal cancer? Evidence from the ColoREctal Wellbeing (CREW) study. PLoS One. 15(4), e0231332. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231332

- Wilson, K. G., Chochinov, H. M., Skirko, M. G., Allard, P., Chary, S., Gagnon, P. R., Macmillan, K., De Luca, M., O'Shea, F., Kuhl, D., Fainsinger, R. L., & Clinch, J. J. (2007). Depression and anxiety disorders in palliative cancer care. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 33(2), 118–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.07.016

- Zellner, M. R., Watt, D. F., Solms, M., & Panksepp, J. (2011). Affective neuroscientific and neuropsychoanalytic approaches to two intractable psychiatric problems: Why depression feels so bad and what addicts really want. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 35(9), 2000–2008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.01.003

- Zigmond, A. S., & Snaith, R. P. (1983). The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 67(6), 361–370. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=6880820 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x