Abstract

Objective

Childhood obesity is a public health challenge with health, economic and psychosocial consequences. The design of interventions addressing childhood obesity seldom considers children’s perspectives on the topic. Weiner’s causal attribution framework was used to explore children’s perspectives on enablers of obesity.

Methods and measures

Children (N = 277) responded to a vignette with an open-ended question. Data were analyzed using content analysis.

Results

Children perceived internal, unstable and controllable causes (e.g. dietary intake, self-regulation and emotionality) as the main enablers (76.53%) of obesity, while some (11.91%) highlighted external, unstable and controllable causes (e.g. parent food restrictions). A focus on children with healthy body weight showed that they mentioned more internal, stable and controllable causes for obesity than children with unhealthy body weight/obesity did. The latter mentioned more external, unstable and controllable causes than their counterparts.

Conclusions

Understanding children’s causal attributions for obesity is expected to deepen our knowledge of obesity enablers and help design interventions matching children’s perspectives.

Introduction

Obesity is considered a chronic disease and a growing epidemic, with childhood obesity being one of the most serious public health challenges of the XXI century (Bray et al., Citation2017; Inchley et al., Citation2017). Obesity has health (e.g. insulin resistance), economic (e.g. costs with remediation), social (e.g. isolation) and psychological (e.g. low self-esteem) related consequences (Cawley et al., Citation2021; Datar et al., Citation2004; World Health Organization [WHO], Citation2021). In particular, literature has emphasized the psychosocial impact of obesity. For example, children with unhealthy body weight/obesity are likely to be the target of prejudice, blame and stigmatization, which may lead to feelings of self-blame (e.g. feelings of failure and guilt for having obesity) (Datar et al., Citation2004; Pearl & Lebowitz, Citation2014; Trainer et al., Citation2022).

To address this public health problem, literature has focused on understanding childhood obesity’s etiology. For example, the Six-Cs Model summarizes a vast body of research on variables likely to contribute to childhood obesity, including genetic factors and others related to eating behavior and physical activity (Harrison et al., Citation2011). Accordingly, there has been considerable investment in designing interventions based on these factors (e.g. nutrition education and interventions to increase physical activity) to prevent and mitigate childhood obesity with promising results (Comeras-Chueca et al., Citation2020; Lee et al., Citation2020). However, evidence indicates that childhood obesity rates remain high, suggesting the need to analyze the reasons behind these data (Bogle & Sykes, Citation2011; Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative [COSI], 2019; Kamath et al., Citation2008).

One possible explanation for the high childhood obesity rates could be that most previous research and interventions targeting obesity did not consider children’s perspectives on their causes (Baranowski, Citation2006). Considering children’s perspectives on the various causes of obesity is relevant because research indicates that meeting the needs of the target audience, and taking into account their current knowledge and perceptions, is critical to promote engagement with interventions and behavior change (Ingoldsby, Citation2010; Nitsch et al., Citation2016). A study by Brogan et al. (Citation2019) with children with obesity and their parents showed great heterogeneity in their perceived causes of obesity. Thus, individual beliefs could be a key determinant when addressing behavior change to design tailored approaches and increase children’s willingness to change (Amiri et al., Citation2011; Rendón-Macías et al., Citation2014). For example, children who perceive obesity as determined by genetic propensity are not likely to engage positively in an intervention that promotes ‘eating more fruit and vegetables’.

Weiner’s Attributional Theory (Weiner, Citation1982, Citation2012) provides a relevant theoretical framework for the current study. According to this model, individuals tend to search for causal explanations for the events of their lives. The causal attribution taxonomy classifies causal explanations into three dimensions: locus, stability and controllability. Locus classifies the causes as internal or external to the self, stability classifies the causes as stable or unstable according to their permanence over time and controllability classifies the causes as controllable or uncontrollable according to the amenability of being manipulated by the individuals or proximal others (Weiner, Citation1982, Citation2012). Weiner’s theory (1982, 2012) states that how individuals interpret and ascribe meaning to events will likely influence their future behavior. For example, in the school domain, when children attribute their success or failure to internal, unstable and controllable causes (e.g. effort), it produces motivation for engaging in behavioral change and persistence in this course of action (Almeida et al., Citation2008; Weiner, Citation2012). Perceiving a cause as self-generated may display a sense of control over the phenomenon, particularly when the cause is amenable to change (Bulman & Wortman, Citation1977).

Purpose

A vast body of literature analyzes the causes of childhood obesity (Harrison et al., Citation2011). However, most of the prior studies are: (a) grounded on bodies of knowledge rather than on a theoretical framework (e.g. Brogan et al., Citation2019; Pearl & Lebowitz, Citation2014); (b) focused only on one dimension of the complex net of causal explanations (e.g. only locus) (Pearl & Lebowitz, Citation2014); and (c) seldom focused on children’s perspective, which may differ from that of experts. In contrast, our study will examine children’s perspectives based on Weiner’s model (1982, 2012). We followed the suggestions made by previous research while considering that children’s perspectives could be key to deepening our knowledge of childhood obesity and explaining their subsequent behavior (Kornilaki, Citation2015). Moreover, grounding research in a robust theoretical framework helps provide clear implications for practice.

The novelty of analyzing children’s perspectives based on the three dimensions of Weiner’s causal attribution model allows us to go beyond the common reflections focused only on the locus of the causes of obesity. For example, a study by Wang et al. (Citation2016) analyzed nurses’ perspectives regarding the locus of causality of obesity and found that most believe the causes of obesity to be beyond the individual’s control. Results also suggested that nurses who make these attributions are more likely to have positive attitudes toward individuals with obesity (Wang et al., Citation2016). Despite being relevant, this information is limited since the authors did not consider whether these external causes of obesity are expected to change over time or are amenable to being manipulated. Thus, in addition to considering the relevance of the locus of causality, the literature suggests that the causes of obesity could also be understood as unstable, triggering individuals’ motivation to change, or, in contrast, as stable, leading individuals to learn discouragement, which may prevent behavioral change (i.e. individuals avoid making efforts to fight obesity because they do not expect changes) (Amiri et al., Citation2011; Weiner, Citation1982). Furthermore, the internal/external and stable/unstable causes could be perceived as controllable – leading to increase motivation and persistence in the case of success or to blame or discouragement in the case of failure –; or as uncontrollable, leading to passive acceptance of their circumstances (Almeida et al., Citation2008). All considered, we believe that Weiner’s Attributional Theory-inspired way of looking at the causes of childhood obesity from the child’s perspective is likely to help better understand children’s obesogenic-related behaviors and attitudes (e.g. adherence to healthy eating, blame).

In sum, the main goal of the present study is to examine children’s perspectives on enablers of obesity from a causal attribution stance. The study enrolls children from a school community sample due to the importance of preventing childhood obesogenic-related behaviors before they arise; as Mikkilä et al. (Citation2005) reported, habits developed during childhood are likely to persist throughout adulthood. The second goal of the present study is to understand whether causal attributions differ by a child’s Body Mass Index (BMI). Braet et al. (Citation2012) emphasized that the psychological mechanisms underlying the perceived causes of obesity could differ in distinct subgroups of children. Understanding these possible differences could help researchers and practitioners develop tailored strategies (Braet et al., Citation2012) likely to increase children’s adherence to interventions and, consequently, increase interventions’ efficacy in promoting healthy behaviors.

Materials and methods

Setting and sample

Our sample comprises children enrolled in an intervention to promote healthy eating carried out in September 2019 in two schools in the north of Portugal. Data collection took place before the beginning of the intervention. During this initial session, data about the worldwide obesity scenario was presented to children (see the measures section). Participants were asked to reflect and write about the possible explanations for this scenario.

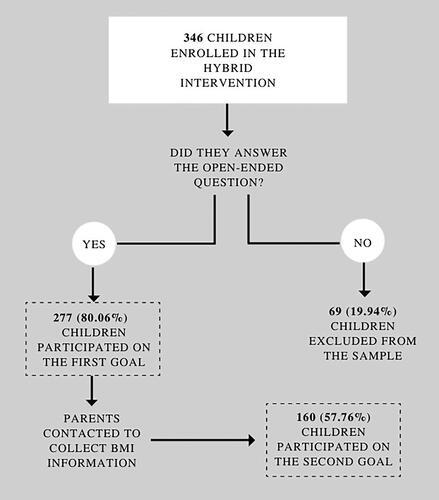

All children enrolled in the intervention were invited to partake in this research (see ). The reasons were: (i) gathering a diverse, maximum variation sample (Sandelowski, Citation1995), with the variation sought across BMI and gender; and (ii) using a vignette with an open-ended question to collect the data. This method requires collecting data from a large sample to achieve the large variability of responses possible and gather representativeness of the phenomenon (Creswell, Citation2012).

Figure 1. Participants’ selection for the qualitative analysis. Note: First goal - examine children’s perspectives of enablers of obesity from a causal attribution stance; Second goal - understand whether causal attributions differ depending on the children’s BMI.

The sample of our first goal was composed of 277 elementary-school children (132 girls, 47.65%) from the 5th and 6th grades, aged between 9 and 14 (M = 10.92, SD = 0.80). For the second goal, to calculate children’s BMI, despite all parents/caregivers being asked about children’s weight, height, gender and date of birth, just 160 responded positively (response rate of 57.76%; ).

To guarantee that the included and excluded samples (i.e. without BMI information) were similar regarding weight distribution, we compared both regarding their income. Income could be a good indicator because there is a close relationship between a family’s income and children’s BMI (Pereira et al., Citation2019). No significant differences between group × income were found [t (0.412; 275), p-value = .680], which may suggest no differences in the BMI of the children in both samples.

Data on the BMI information show that two (1.2%) participants had underweight, 108 (67.5%) had healthy body weight, 38 (23.8%) had unhealthy body weight and 12 (7.5%) had obesity (see measures section for details on BMI calculation). Considering the purpose of the second goal, participants with underweight were excluded from the analysis and participants with unhealthy body weight and obesity were included in the same group. The BMI distribution is not balanced, which might be due to being a school community sample – the distribution is close to what is expected in the general population (e.g. 29.6% of children with unhealthy body weight; COSI, Citation2019).

Measurement

Vignette with an open-ended question

Compared with closed-format questions, open-ended questions reduce the likelihood of biased responses and are better suited to capture the diversity of participants’ perceptions about a topic. Vignettes consist of written scenarios with brief descriptions of situations likely to prompt participants’ judgments (Wason et al., Citation2002). Advantages of using vignettes include: (i) providing the participants an evaluation of the situation presented and their position towards it; (ii) providing a standardized stimulus for all participants; (iii) reducing social convenience bias; and (iv) increasing the involvement of participants (Evans et al., Citation2015; Wason et al., Citation2002). In the present study, the vignette with an open-ended format question presented the following scenario:

It is estimated that: 1.9 billion adults have unhealthy body weight, and 650 million have obesity; 30% of children have unhealthy body weight or obesity, and 38 million under the age of 5 have unhealthy body weight or obesity.

What do you think are the causes for this scenario worldwide?

BMI

To evaluate children’s BMI, the Z-score classification system was used (Onis & Blössner, Citation1997). The Z-score system expresses the anthropometric value as the number of standard deviations below or above the mean or median value of reference. Parents/caregivers were asked about their child’s height, weight, gender and date of birth. With this information, we used the WHO AnthroPlus software to calculate children’s Z-scores. The classification through Z-scores for five-19 years is as follows: Obesity: > +2 SD, Unhealthy body weight: > +1 SD, Healthy range weight: between +1 SD and −1 SD, Underweight: between −1 SD and −2 SD and Severe thinness: > −2 SD.

Data collection

This study is part of a research project approved by the University of Minho Ethics Committee for Research in Social and Human Sciences (CEICSH) (CEICSH 032/2019). Consent to conduct the study in a school setting was obtained from the Portuguese Ministry of Education. Parents/caregivers of the participants provided written informed consent, and the children provided assent to participate.

Researchers collected data in person. The scenario’s presentation and the open-ended question completion took approximately 15 min. Afterward, responses were transcribed verbatim. Finally, a form was sent to parents/caregivers asking for their children’s BMI-related information. The information provided by the parents was matched to the children’s qualitative transcriptions via an assigned code.

Data analysis

Qualitative data were analyzed through content analysis, following the steps (i.e. pre-analysis, exploration of data and treatment) described by Bardin (Citation1977). The identification of categories and subcategories followed a deductive and an inductive iterative process. In the former, based on the three dimensions of Weiner’s model (Weiner, Citation1982, Citation2012), the eight possible categories were organized a priori in a codebook. Additionally, the subcategories were established based on the Six-Cs model, presenting contributors to childhood obesity (Harrison et al., Citation2011). As part of the inductive process, new subcategories were added based on new insights that emerged from the data as the analysis was carried out. The QSR International’s NVivo 10 software was used to assist with the data organization, management, coding and querying process (Richards, Citation2005).

Methodological procedures to enhance the trustworthiness of the findings were set up (Goodell et al., Citation2016). Before the treatment phase, two researchers (i) discussed the distinguishing criteria of each of the categories and subcategories; (ii) practiced together applying the codebook to a selection of transcriptions comprising most categories and subcategories until they agreed on coding; (iii) codified a distinct selection of transcriptions independently, compared codifications and resolved any differences through discussion; until (iv) reached consistency on codification. Afterward, one researcher coded all the data, and a second coded 40% independently. The two researchers reviewed all categories and subcategories and discussed the differences found to reach a consensus. The Kappa value obtained was 0.83, considered excellent according to Landis and Koch (Citation1977).

To meet our first goal (i.e. examine children’s perspectives on enablers of obesity), the NVivo 10 software provided the number of participants in each category and subcategory, and the researchers calculated the respective frequencies and percentages. Then, the causal attributions more frequently referenced by children were analyzed. Finally, to meet the second goal, coding matrices were analyzed to investigate possible category frequency differences according to participants’ BMI.

Results

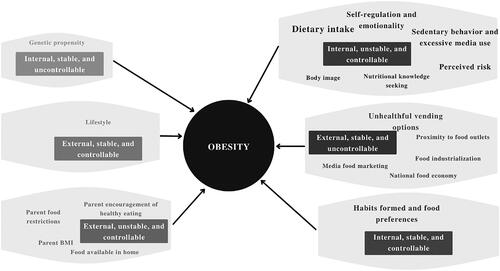

Attributions of obesity were highly diverse, with some children indicating a single cause and others a complex array of factors. Weiner’s model comprises eight possible attribution categories. In the present study, six out of these eight attribution categories were found: (i) Internal, unstable and controllable causes, (ii) External, stable and uncontrollable causes, (iii) Internal, stable and controllable causes, (iv) External, unstable and controllable causes, (v) External, stable and controllable causes and (vi) Internal, stable and uncontrollable causes. In the present section, the categories and subcategories were presented in decreasing order, from the most mentioned to the least mentioned.

To clarify the reporting process of the frequency of responses for each category and subcategory, we followed the Cooper and Rodgers (Citation2006) scoring scheme set for qualitative analyses with samples of 23 participants [all = 23 cases (100% of the participants); near all = 21 to 22 cases (100% minus 2 of the participants); most = 13 to 20 cases (50% plus 1 to 100% minus 2 of the participants); around half = 11 to 12 cases (50% minus 1 of the participants); some = 3 to 10 cases (3 to 50% plus 1 of the participants); a couple = 2 participants; one = 1 case]. In the current study, we used an adapted version while maintaining the proportionality of the frequencies. Scores were as follows: all = 277 cases (100% of the participants), nearly all = 253 to 276 cases (100% minus 24 to 100% minus1 of the participants), most = 163 to 252 cases (50% plus 24 to 100% minus 24 of the participants), around half = 114 to 162 cases (50% minus 24 to 50% plus 24 of the participants), some = 26 to 113 cases (26 to 50% minus 24 of the participants), a few = 2 to 25 cases (2 to 1 plus 24 participants) and one = 1 case. presents all the subcategories emerging in each category, with the respective response distribution and representative quotes. However, we only explored the categories and subcategories with reasonable representation in the data (categories and subcategories scoring n ≥ 8).

Table 1. Responses of children to the open-ended question about obesity causes.

Internal, unstable and controllable causes (76.53% of the total cases)

An excerpt of a response was classified as internal, unstable and controllable when children attributed obesity to causes related to themselves, likely to change over time and amenable to manipulation (i.e. children could change these factors). This attribution was the most mentioned category. Six subcategories were identified: dietary intake, self-regulation and emotionality, sedentary behavior and excessive media use, perceived risk, nutritional knowledge seeking and body image.

Dietary intake (44.40% of the cases within this category)

Around half of children perceived Dietary intake as a major cause of obesity. Participants indicated that not practicing a healthy and balanced diet and, conversely, practicing an unhealthy one contributes to obesity. Specifically, participants said that the consumption of large amounts of unhealthy food, such as junk food, candies and food with added salt, could lead to an excessive caloric intake.

They [people with obesity] only eat, for example, pizzas, hot dogs, schnitzels, many others [unhealthy foods]. People with obesity do not eat vegetables, fruits, soups; they do not eat healthy things. (CGA4, 12-year-old boy)

Self-regulation and emotionality (23.10% of the cases within this category)

Some children attributed obesity to a lack of self-control to avoid certain unhealthy foods that people feel like eating. Participants mentioned that after eating these unhealthy foods, individuals struggle to stop and tend to overeat. Consequently, eating becomes an addiction. It also emphasized the lack of motivation to plan and control diets.

They think like this: I am going to eat one more, just one more. In the end, they are already with obesity. (ARGB2, 12-year-old girl)

Sedentary behavior and excessive media use (18.05% of the cases within this category)

Some children mentioned a lack of physical activity as a cause of obesity. Participants declared that individuals are decreasing their regular exercise practice, especially in outdoor activities such as hiking. Moreover, participants stressed that increasing levels of sedentarism were related to the growing use of technology (e.g. individuals spend many hours sitting on the sofa watching television and playing with their smartphone/computer).

Nowadays, people prefer to watch television or play on the computer for long hours than to exercise (PVBG20, 12-year-old boy)

Perceived risk (14.8% of the cases within this category)

Some participants reported that individuals have obesity because they are unaware of its consequences and are not careful with their diets or general health. Some children stated that sometimes individuals only realize the health consequences of their excess weight when they already have unhealthy body weight.

People think that if they overeat and put on weight, nothing will happen to them (IMCS12, 9-year-old girl)

Nutritional knowledge seeking (6.86% of the cases within this category)

A few children attributed obesity to a lack of knowledge about healthy eating-related topics (e.g. food wheel). Participants mentioned that individuals often lack knowledge about what they eat and how to gather and apply information about a healthy diet.

They are unaware of the mistakes they make when eating certain foods (JGGN14, 11-year-old boy)

External, stable and uncontrollable causes (27.08% of the total cases)

An excerpt of a response was classified as external, stable and uncontrollable when children attributed obesity to causes related to environmental factors, unlikely to change over time and not amenable to being manipulated by individuals or proximal others. Five subcategories were identified: unhealthy vending options, proximity to food outlets, food industrialization, national food economy and media food marketing. Importantly, the subcategory ‘Food industrialization’ emerged from our data, despite being mentioned by a few children.

Unhealthful vending options (10.47% of the cases within this category)

Some children placed the responsibility for obesity on certain types of food sold in or near the school, especially those with added fats and sugars (e.g. jellies, burgers). Participants stated that there is an increasing availability of unhealthy foods, which are seen as more appealing and tastier than healthy ones. Consequently, these foods divert children from healthy eating while making them fat.

Processed foods are more attractive and less healthy, which makes them more consumed (DVM6, 11-year-old boy)

Proximity to food outlets (8.66% of the cases within this category)

Concurrently, a few participants indicated that the evolution of fast-food chains also contributes to obesity. Children mentioned that unhealthy-food-type restaurants are easier to find and are more prevalent than healthy ones. For example, participants stated that typically malls house several unhealthy food outlets (e.g. restaurants with processed food and candy stores).

When they go to shopping centers, there are many fast-food stores such as McDonald’s, Burger King, Steak Shake, Pizza Hut, Telepizza, Hussel, etc … (MSPA19, 10-year-old girl)

Food industrialization (6.14% of the cases within this category)

The modernization of the food industry is a perceived cause of obesity related to the previous one. A few children pointed out that, in the past, the number of sweets and unhealthy food brands available was more restricted compared to nowadays. A few participants stated that processed products are misleading consumers because they contain additives and chemicals that create artificial flavors while making foods tastier and more addictive.

The food is not of great quality. It is full of chemicals to make it look more appetizing. But if we look at how they are made, they are a danger to our health. (FCC6, 11-year-old girl)

National food economy (5.05% of the cases within this category)

A few children mentioned that obesity is caused by food prices (e.g. low prices for unhealthy foods [such as fast-food] and high prices for healthy foods [such as fruit and vegetables]). They believe that the food business is profitable and that companies producing unhealthy foods are more interested in economic growth than people’s well-being.

People continue to consume these [unhealthy] foods because they are cheap and fast. The people who produce them only think to produce for less [money] and more profit. (FCC6, 11-year-old girl)

Media food marketing (3.25% of the cases within this category)

A few children mentioned the importance of advertisements as a cause for obesity, specifically, the high number of advertisements (e.g. television, street mockup) with misleading messages inciting individuals to eat unhealthily. Participants also mentioned that food marketing predominantly promotes foods and drinks that are harmful to health rather than healthy foods.

Because of advertising. Usually, when I see advertising, it is about fast food; you rarely see advertising about mineral water or fruit, making people buy more fast food than healthy food. (CBCT3, 11-year-old girl)

Internal, stable and controllable causes (22.74% of the total cases)

An excerpt of a response was classified as internal, stable and controllable when children attributed obesity to causes related to themselves, unlikely to change over time but amenable to manipulation (i.e. children could change these factors). Just one subcategory was identified within this theme; still, this subcategory was mentioned by some participants.

Habits formed and food preferences (22.74% of the cases within this category)

Some children pointed out unhealthy eating practices that become a habit as a cause for obesity (i.e. eating junk food or going out to eat at restaurants every day or several times per week). Additionally, participants highlighted that the acquisition of these habits begins early in life. Children mentioned two reasons for grounding these habits. First, individuals prefer unhealthy to healthy foods because the former (e.g. sweet foods) taste better than the latter (e.g. vegetables). Second, individuals prefer unhealthy foods because they believe this is faster and easier than healthy options.

People have gotten used to it, and now there are millions of people who prefer food with lots of fats and have obesity instead of eating healthier foods. (ALLCI, 11-year-old girl)

External, unstable and controllable causes (11.91% of the total cases)

An excerpt of a response was classified as external, unstable and controllable when children attributed obesity to causes related to environmental variables, specifically family-related factors, that were amenable to being manipulated (i.e. parents could change these factors). Four subcategories were identified: parent encouragement of healthy eating, parent food restrictions, parent BMI and food available in the home. Some participants mentioned this category.

Parent encouragement of healthy eating (6.14% of the cases within this category)

A few children mentioned the lack of parental incentive to eat healthy as an enabler of obesity. More specifically, these participants described that some parents seldom provide their children with guidance about what they should eat or even care about their children’s food habits. In contrast, other children (a few) also mentioned that some parents encourage children to eat food and gain weight rather than encourage them to eat healthily.

Sometimes parents also don’t help their children; they don’t teach them what to eat (EFD5, 11-year-old boy)

Parents tell them [they need] to eat and get fat (IC10, 10-year-old girl)

Parent food restrictions (5.05% of the cases within this category)

A few children held their parents responsible for following a non-food restriction diet education. Participants mentioned that many parents let children eat without external control, including unhealthy foods that may contribute to their obesity (e.g. junk food and desserts high in sugar). According to participants, children who want to eat unhealthy food just need to ask for it or throw a tantrum.

Children ask their parents to eat lasagna, chips, etc… and parents give them that to eat (MPT17, 12-year-old boy)

External, stable, and controllable causes (3.61% of the total cases)

An excerpt of a response was classified as external, stable and controllable when children attributed obesity to causes related to environmental variables that are unlikely to change over time but amenable to being manipulated. Only one subcategory was identified within this category, and just a few children mentioned it.

Lifestyle (3.61% of the total cases)

A few children mentioned obesity as a contemporary lifestyle consequence. Participants mentioned that people who tend to live in a hurry lack time to cook healthy homemade meals. Additionally, participants mentioned that many people working in offices do not have the time to eat a proper lunch or do exercise. Another consequence of the present way of life mentioned by the participants was the easiness of ordering food online without leaving home/office.

Lately, people are very hurried and do not have time to prepare healthy foods at home; they choose to go to processed [food] restaurants such as MC Donald’s, Burger King, etc… (IGC11, 11-year-old girl)

Differences by children’s BMI

To examine response frequency by BMI, two analyses were conducted. First, an inter-category analysis has shown a similar pattern in the children’s response frequency by BMI in four out of the six categories: internal, stable and uncontrollable causes (i.e. genetic propensity), internal, unstable and controllable causes (e.g. dietary intake), external, stable and uncontrollable causes (e.g. unhealthful vending options) and external, stable and controllable causes (i.e. lifestyle). Regarding the other two categories, data show that children with healthy body weight mentioned internal, stable and controllable causes for obesity (i.e. habits formed and food preferences) around 4% more times than their counterparts with unhealthy body weight/obesity. In contrast, the participants with unhealthy body weight/obesity mentioned external, unstable and controllable causes of obesity (e.g. parent food restrictions) around 6% more often when compared with counterparts with healthy body weight. In particular, only children with unhealthy body weight/obesity mentioned their parent’s BMI as a cause for obesity; additionally, these children mentioned their parents’ food restrictions around 4% more often than their counterparts with healthy body weight did.

Second, a detailed within-category analysis has shown differences in some subcategories from two categories, i.e. external, stable and uncontrollable and internal, unstable and controllable causes. Regarding the external, stable and uncontrollable categories, children with healthy body weight mentioned the food industrialization cause around 4% more often than their counterparts with unhealthy body weight/obesity. Conversely, children with unhealthy body weight/obesity mentioned the proximity of food outlets around 4% more often than counterparts with healthy body weight. Concerning the internal, unstable and controllable category, children with healthy body weight mentioned the perceived risk factor around 4% more often than their counterparts with unhealthy body weight/obesity. Finally, children with unhealthy body weight/obesity referred to dietary intake as a cause approximately 8% more often than their counterparts with healthy body weight.

Discussion

Grounded on Weiner’s model (1982), this study explored the enablers of obesity from the children’s perspective. To attain this goal, children were presented with a vignette focused on obesity along with an open-ended question. The qualitative analysis of the responses allowed us to understand children’s causal attributions for obesity (see ). In addition, we examined whether causal attributions differed depending on children’s BMI. The following subsections address the more prominent result, the non-expected result, the differences by children’s BMI and the emerging enablers.

Figure 2. Visual map of the categories, subcategories and representatively developed through content analysis. Note: The kites’ size represents the frequency in which the causal attributions were represented in the results (i.e. larger kites, most mentioned categories). Data are presented following Cooper and Rodgers (Citation2006) scoring scheme. In each kite, the frequency of each subcategory within the theme is presented through font-size: big font size represents subcategories mentioned by around half of children (50% – 24 to 50% + 24, n = 114 to 162), medium font size represents subcategories mentioned by some children (25 to 50% – 24, n = 26 to 113), small font size represents subcategories mentioned by a few children (2 to 1 + 24, n = 2 to 25).

The main results

Internal, unstable and controllable causes were the children’s primary attributions for obesity. Children perceive obesity as the result of a combination of factors related to themselves, which are likely to change over time and under their control. Specifically, dietary practices characterized by low consumption of healthy foods and high consumption of unhealthy foods, poor self-regulation to cope with food temptations, sedentary habits and lack of perceived risk of the negative implications of obesity were identified as primary causes of obesity. This is consistent with evidence warning that poor diets and insufficient physical activity are the main drivers of obesity (Harrison et al., Citation2011) and with the findings of Pereira et al., (Citation2019) stressing the positive influence of self-regulation toward healthy eating on children’s weight. The current finding is also consistent with prior research showing that the perceived risk of obesity plays a central role in weight management (Alm et al., Citation2008).

In general, children showed awareness of their personal responsibility while making efforts to control and change some obesogenic behaviors; for example, very few children attributed obesity to genetics (i.e. internal, stable and uncontrollable causes). Interestingly, the latter result differs from Amiri et al. (Citation2011) data with adolescents indicating genetics as a prominent category explaining obesity. These authors concluded that this attribution likely contributes to feelings of lack of control towards own weight and health. Thus, the data may suggest the importance of intervening early in life before the transition to adolescence. This phase is characterized by more stable and less malleable attitudes than childhood, and adolescents are more resistant to change (Pearl & Lebowitz, Citation2014).

Children’s awareness of their personal responsibility toward obesity causes could also result from their exposure to public health and marketing campaigns (Pearl & Lebowitz, Citation2014; Puhl et al., Citation2013). To illustrate, news on television and social media have consistently stressed the need for individual behavioral changes rather than system-level solutions (e.g. food industry) to face obesity (Barry et al., Citation2011). The risks of focusing primarily on solutions at an individual level are manifold; for example, children may experience shame and discouragement when they fail to change their obesogenic behaviors or maintain healthy ones (Simpson et al., Citation2019). As Pearl and Lebowitz (Citation2014) warn, educators should be attentive to the high prejudice and blame children may experience as a consequence of failure in the accomplishment of healthy behaviors (both towards themselves and others; e.g. Throsby, Citation2007).

Unexpected findings

In the current study, the number of children attributing obesity to parent-related enablers (i.e. external, unstable and controllable causes) was low. This finding is consistent with those from Magalhães et al., (Citation2022), reporting few perceived parent-related barriers to healthy eating in a community sample. Nevertheless, we found interesting data while analyzing results by BMI. Children with unhealthy body weight/obesity appear to place greater emphasis on the role parents may play than their counterparts with healthy body weight did. This is consistent with the study by Brogan et al. (Citation2019), showing that children with obesity perceive the influence of parents as one of the causes of obesity. Thus, data suggest that some children with unhealthy body weight/obesity are prone to believe that the causes of obesity are not self-related, and although it is possible to change them, the control pertains to their parents who, in many cases, have unhealthy body weight/obesity (Lazzeri et al., Citation2011; Raynor et al., Citation2011).

Differences by children’s BMI

Children with unhealthy body weight/obesity also seem to attribute obesity more often to external, stable and uncontrollable causes (e.g. proximity to food outlets) than their counterparts with healthy body weight do. These attributions may indicate that the former believe that the causes of obesity are nonrelated to their behavior, will remain over time, and, importantly, there is nothing they or close others can do to change them (Almeida et al., Citation2008; Weiner, Citation1982, Citation2012). Children may be making these attributions to protect their self-esteem and avoid the sense of blame that an awareness of personal responsibility could entail (Branscombe & Wann, Citation1994; Pearl & Lebowitz, Citation2014); however, these approaches to obesity could translate into passive acceptance of their circumstances and resistance to interventions (Almeida et al., Citation2008; Amiri et al., Citation2011).

We also learned that children with healthy body weight mentioned internal, stable and controllable causes of obesity (i.e. habits formed and food preferences) more often than their counterparts with unhealthy body weight/obesity did. This finding is important because children making these attributions could be prone to blaming their peers for their obesogenic behaviors and voicing expectations that these behaviors would maintain over time (Weiner, Citation2012). Importantly, efforts to blame peers for their unhealthy behaviors are not aligned with the chronic disease model that views obesity as caused by an agent (e.g. food, genetics, environmental factors) affecting the host (e.g. children) and producing a disease (e.g. obesity) (Bray et al., Citation2017). These beliefs could lead to stigmatization and social prejudice towards individuals with unhealthy body weight/obesity (Datar et al., Citation2004; Trainer et al., Citation2022).

Emerging enablers

We believe our data also add to the literature by emphasizing two new enablers of obesity (i.e. food industrialization and lifestyle) that could be related to the increasing development of industries and society (e.g. Datar et al., Citation2014). Current new data are aligned with warnings from the WHO highlighting that health maintenance is particularly relevant amidst the context of increased production and availability of processed foods, rapid urbanization and changes in people’s lifestyles likely to lead to an increase in unhealthy dietary patterns (WHO, Citation2020).

Implications for practice

The present study provides contributions to practice by supporting prior evidence indicating that the design of interventions on a particular topic should match the perceptions of the target population on that topic (Ingoldsby, Citation2010; Nitsch et al., Citation2016). In general, data suggest that children could benefit from behavior change interventions addressing constructs emerging in the more prominent category of our results, such as promoting healthy behaviors through self-regulation training (Pereira et al., Citation2018, Magalhães et al., Citation2020). A study by Daniel et al. (Citation2015) showed that developing self-regulation strategies may help children with unhealthy body weight/obesity to deal with food temptations by reducing delay discounting, i.e. disregarding larger future rewards (e.g. good health) in favor of smaller immediate rewards (e.g. eat processed food). In fact, children with training in self-regulation strategies are expected to proactively develop and maintain healthy habits despite the reported external influences (e.g. the proximity of food outlets) (Rosário et al., Citation2017). In our study, children identified lack of perceived risk as a cause of obesity. This important finding could help educators set up brief interventions to improve children’s awareness of the consequences of obesity while promoting positive attitudes about the benefits of healthy behaviors (Pereira et al., Citation2021).

Additionally, as our data suggest, when targeting obesity, educators could consider teaching children about the chronic disease model of obesity by striking a balance between factors focused on promoting healthy eating and physical activity and those out of children’s control. This approach is likely to help children failing to achieve healthy behavior goals overcome their sense of blame and actively engage in interventions (Branscombe & Wann, Citation1994; Pearl & Lebowitz, Citation2014). Moreover, by mentioning enablers that are out of children’s control, educators prevent the propagation of stigmatizing messages and attitudes towards individuals with obesity, likely to lead to social prejudice (Barry et al., Citation2011; Throsby, Citation2007).

Current data suggest that children with unhealthy body weight/obesity and children with healthy body weight understand the causes of obesity distinctively. Thus, these subgroups of children may also differ on the psychological mechanisms underlying the perceived causes of obesity (e.g. acceptance of their circumstances vs. willingness to change) (Almeida et al., Citation2008; Braet et al., Citation2012). Nevertheless, literature has highlighted the benefits of considering the different characteristics of a group of children as an approach to designing tailored strategies and interventions (Braet et al., Citation2012). For example, present results suggest that children with unhealthy body weight/obesity, when compared with counterparts, may be more resistant to change and need further help to understand the internal causes of obesity better. Moreover, these children may also benefit most from interventions targeting children-plus-parents. In fact, Baghurst and Eichmann (Citation2014) found that interventions targeting both children and parents had increased effectiveness in changing obesity-related behaviors. During childhood, parents have a prominent role in their children’s education; for example, while influencing their eating behavior (Scaglioni et al., Citation2018). However, as mentioned in the present results, due to the ongoing lifestyle changes, many parents do not have time to cook meals at home and may end up providing children with unhealthy foods from restaurants. Therefore, interventions focused on healthy eating habits targeting children-plus-parents are expected to help parents with time constraints (e.g. working parents) while providing training on strategies for planning healthy meals (Dahl et al., Citation2023). Conversely to children with unhealthy weight/obesity, children with healthy body weight may benefit from interventions aiming to promote healthy behaviors to prevent the risks of developing obesity in the future.

Lastly, our study supports the need to acknowledge the rapid advances and changes in the food industry and lifestyle (Harrison et al., Citation2011). Accordingly, future interventions could consider new potential contributors to obesity to keep pace with rapid advances in food-related topics, and interventions should be complemented with policy actions.

Limitations and future research

Limitations of this study include the methodology adopted for data collection. Even though the vignette with an open-ended question is likely to capture the diversity of children’s perceptions, most answers consisted of a few sentences, which may have prevented participants from conveying a full picture of their understanding of obesity causes. Future studies could consider using interviews to capture children’s perceptions further. Additionally, difficulties in reaching parents through schools were an obstacle to data collection (e.g. parents’ low availability to engage in research). This obstacle might help explain why we did not have access to BMI information for 42% of the children. Moreover, although we have followed the work of Goodman et al. (Citation2000), showing that they correctly classified 96% of adolescents’ weight status through parental self-reported height and weight data, parents’ reports of their child’s height and weight may have led to inaccurate answers and error in the BMI calculation. Future studies could consider collecting BMI data via objective measures. Finally, children in the present study were enrolled in an intervention promoting healthy eating, which might lead to a sampling bias. Children that accepted to participate in the intervention could have built perceptions about the causes of obesity distinct from those who did not accept to participate in the intervention (e.g. children with common knowledge may understand the causes of obesity as external, stable and uncontrollable, which may lead to resistance to interventions; Almeida et al., Citation2008; Amiri et al., Citation2011). Thus, future research should consider analyzing the causal attributions of a totally naïve sample.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Katarina Agudelo for the English-language editing of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

Data will be available upon request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alm, M., Soroudi, N., Wylie-Rosett, J., Isasi, C. R., Suchday, S., Rieder, J., & Khan, U. (2008). A qualitative assessment of barriers and facilitators to achieving behavior goals among obese inner-city adolescents in a weight management program. The Diabetes Educator, 34(2), 277–284. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145721708314182

- Almeida L da, S., Miranda, L., & Guisande, M. A. (2008). Atribuições causais para o sucesso e fracasso escolares. Estudos De Psicologia (Campinas), 25(2), 169–176.cc

- Amiri, P., Ghofranipour, F., Ahmadi, F., Hosseinpanah, F., Montazeri, A., Jalali-Farahani, S., & Rastegarpour, A. (2011). Barriers to a healthy lifestyle among obese adolescents: A qualitative study from Iran. International Journal of Public Health, 56(2), 181–189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-010-0119-6

- Baghurst, T., & Eichmann, K. (2014). Effectiveness of a child-only and a child-plus-parent nutritional education program. Journal of Child and Adolescent Health, 7(3), 229–237.

- Baranowski, T. (2006). Crisis and chaos in behavioral nutrition and physical activity. The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 3(1), 27. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-3-27

- Bardin, L. (1977). The content analysis. Presses Universitaires de France.

- Barry, C. L., Jarlenski, M., Grob, R., Schlesinger, M., & Gollust, S. E. (2011). News media framing of childhood obesity in the United States from 2000 to 2009. Pediatrics, 128(1), 132–145. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-3924

- Bogle, V., & Sykes, C. (2011). Psychological interventions in the treatment of childhood obesity: What we know and need to find out. Journal of Health Psychology, 16(7), 997–1014. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105310397626

- Braet, C., Beyers, W., Goossens, L., Verbeken, S., & Moens, E. (2012). Subtyping children and adolescents who are overweight based on eating pathology and psychopathology. European Eating Disorders Review : The Journal of the Eating Disorders Association, 20(4), 279–286. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.1151

- Branscombe, N. R., & Wann, D. L. (1994). Collective self-esteem consequences of outgroup derogation when a valued social identity is on trial - Branscombe. European Journal of Social Psychology, 24(6), 641–657. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420240603

- Bray, G. A., Kim, K. K.,Wilding, J. P. H., & World Obesity Federation. (2017). Obesity: A chronic relapsing progressive disease process. A position statement of the World Obesity Federation. Obesity Reviews: An Official Journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity, 18(7), 715–723. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12551

- Brogan, A., Hevey, D., Wilson, C., Brinkley, A., O’Malley, G., & Murphy, S. (2019). A network analysis of the causal attributions for obesity in children and adolescents and their parents. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 24(9), 1063–1074. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2019.1620298

- Bulman, R. J., & Wortman, C. B. (1977). Attributions of blame and coping in the ‘real world’: Severe accident victims react to their lot. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 35(5), 351–363. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.35.5.351

- Cawley, J., Biener, A., Meyerhoefer, C., Ding, Y., Zvenyach, T., Smolarz, B. G., & Ramasamy, A. (2021). Direct medical costs of obesity in the United States and the most populous states. Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy, 27(3), 354–366. https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2021.20410

- Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative. (2019). COSI Portugal – 2019. http://www.insa.min-saude.pt/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/COSI2019_FactSheet.pdf

- Comeras-Chueca, C., Villalba-Heredia, L., Pérez-Llera, M., Lozano-Berges, G., Marín-Puyalto, J., Vicente-Rodríguez, G., Matute-Llorente, Á., Casajús, J. A., & González-Agüero, A. (2020). Assessment of active video games’ energy expenditure in children with overweight and obesity and differences by gender. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(18), 6714. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186714

- Cooper, M., & Rodgers, B. (2006). Proposed scoring scheme for qualitative thematic analysis. Proposed scoring scheme for qualitative thematic analysis. University of Strathclyde.

- Creswell, J. W. (2012). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (4th ed.). Pearson.

- Dahl, A. A., Mayfield, M., Fernandez-Borunda, A., Butts, S. J., Grafals, M., & Racine, E. F. (2023). Dinner planning and preparation considerations of parents with children attending childcare. Appetite, 180, 106332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2022.106332

- Daniel, T. O., Said, M., Stanton, C. M., & Epstein, L. H. (2015). Episodic future thinking reduces delay discounting and energy intake in children. Eating Behaviors, 18, 20–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2015.03.006

- Datar, A., Nicosia, N., & Shier, V. (2014). Maternal work and children’s diet, activity, and obesity. Social Science & Medicine, 107, 196–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.12.022

- Datar, A., Sturm, R., & Magnabosco, J. L. (2004). Childhood overweight and academic performance: National study of kindergartners and first-graders. Obesity Research, 12(1), 58–68. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2004.9

- Evans, S. C., Roberts, M. C., Keeley, J. W., Blossom, J. B., Amaro, C. M., Garcia, A. M., Stough, C. O., Canter, K. S., Robles, R., & Reed, G. M. (2015). Vignette methodologies for studying clinicians’ decision-making: Validity, utility, and application in ICD-11 field studies. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 15(2), 160–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijchp.2014.12.001

- Goodell, L. S., Stage, V. C., & Cooke, N. K. (2016). Practical qualitative research strategies: Training interviewers and coders. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 48(8), 578–585.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2016.06.001

- Goodman, E., Hinden, B. R., & Khandelwal, S. (2000). Accuracy of teen and parental reports of obesity and Body Mass Index. Pediatrics, 106(1 Pt 1), 52–58. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.106.1.52

- Harrison, K., Bost, K. K., McBride, B. A., Donovan, S. M., Grigsby-Toussaint, D. S., Kim, J., Liechty, J. M., Wiley, A., Teran-Garcia, M., & Jacobsohn, G. C. (2011). Toward a developmental conceptualization of contributors to overweight and obesity in childhood: The Six-Cs model. Child Development Perspectives, 5(1), 50–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-8606.2010.00150.x

- Inchley, J., Currie, D., Jewell, J., Breda, J., & Barnekow, V.(2017). Adolescent obesity and related behaviours: Trends and inequalities in the WHO European Region, 2002–2014: Observations from the Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) WHO Collaborative Cross-National Study. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/329417

- Ingoldsby, E. M. (2010). Review of interventions to improve family engagement and retention in parent and child mental health programs. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19(5), 629–645. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-009-9350-2

- Kamath, C. C., Vickers, K. S., Ehrlich, A., McGovern, L., Johnson, J., Singhal, V., Paulo, R., Hettinger, A., Erwin, P. J., & Montori, V. M. (2008). Behavioral interventions to prevent childhood obesity: A systematic review and metaanalyses of randomized trials. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 93(12), 4606–4615. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2006-2411

- Kornilaki, E. N. (2015). Obesity bias in children: The role of actual and perceived body size. Infant and Child Development, 24(4), 365–378. https://doi.org/10.1002/icd.1894

- Landis, J. R., & Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33(1), 159–174. https://doi.org/10.2307/2529310

- Lazzeri, G., Pammolli, A., Pilato, V., & Giacchi, M. V. (2011). Relationship between 8/9-yr-old school children BMI, parents’ BMI and educational level: A cross sectional survey. Nutrition Journal, 10(1), 76. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-10-76

- Lee, S. Y., Kim, J., Oh, S., Kim, Y., Woo, S., Jang, H. B., Lee, H.-J., Park, S. I., Park, K. H., & Lim, H. (2020). A 24-week intervention based on nutrition care process improves diet quality, body mass index, and motivation in children and adolescents with obesity. Nutrition Research (New York, N.Y.), 84, 53–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nutres.2020.09.005

- Magalhães, P., Silva, C., Pereira, B., Figueiredo, G., Guimarães, A., Pereira, A., & Rosário, P. (2020). An online-based intervention to promote healthy eating through self-regulation among children: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials, 21(1), 786. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-020-04685-5

- Magalhães, P., Vilas, C., Pereira, B., Silva, C., Oliveira, H., Aguiar, C., & Rosário, P. (2022). Children’s perceived barriers to a healthy diet: The influence of child and community-related factors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(4), Article 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042069

- Mikkilä, V., Räsänen, L., Raitakari, O. T., Pietinen, P., & Viikari, J. (2005). Consistent dietary patterns identified from childhood to adulthood: The cardiovascular risk in young finns study. The British Journal of Nutrition, 93(6), 923–931. https://doi.org/10.1079/BJN20051418

- Nitsch, M., Dimopoulos, C. N., Flaschberger, E., Saffran, K., Kruger, J. F., Garlock, L., Wilfley, D. E., Taylor, C. B., & Jones, M. (2016). A guided online and mobile self-help program for individuals with eating disorders: An iterative engagement and usability study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18(1), e7. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.4972

- Onis, M., & Blössner, M. (1997). WHO Global Database on Child Growth and Malnutrition. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/63750/WHO_NUT_97.4.pdf;jsessionid=32DCEFA4D1E12FA21958B5C5A2A154FE?sequence=1

- Pearl, R. L., & Lebowitz, M. S. (2014). Beyond personal responsibility: Effects of causal attributions for overweight and obesity on weight-related beliefs, stigma, and policy support. Psychology & Health, 29(10), 1176–1191. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2014.916807

- Pereira, B., Magalhães, P., & Pereira, R. (2018). Building knowledge of healthy eating in hospitalized youth: A self-regulated campaign. Psicothema, 30(4), 415–420. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2018.148

- Pereira, B., Rosário, P., Silva, C., Figueiredo, G., Núñez, J. C., & Magalhães, P. (2019). The mediator and/or moderator role of complexity of knowledge about healthy eating and self-regulated behavior on the relation between family’s income and children’s obesity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(21), Article 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16214207

- Pereira, B., Magalhães, P., Núñez, J. C., Vallejo, G., Pereira, A., Lopes, S., & Rosário, P. (2021). Elementary school students’ attitudes towards cerebral palsy: A raising awareness brief intervention. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2021.1900420

- Puhl, R., Peterson, J. L., & Luedicke, J. (2013). Fighting obesity or obese persons? Public perceptions of obesity-related health messages. International Journal of Obesity, 37(6), 774–782. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2012.156

- Raynor, H. A., Van Walleghen, E. L., Osterholt, K. M., Hart, C. N., Jelalian, E., Wing, R. R., & Goldfield, G. S. (2011). The relationship between child and parent food hedonics and parent and child food group intake in children with overweight/obesity. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 111(3), 425–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2010.12.013

- Rendón-Macías, M.-E., Rosas-Vargas, H., Villasís-Keever, M.-Á., & Pérez-García, C. (2014). Children’s perception on obesity and quality of life: A Mexican survey. BMC Pediatrics, 14(1), 131. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-14-131

- Richards, L. (2005). Handling qualitative data: A practical guide. SAGE Publications.

- Rosário, P., Núñez, J. C., Rodríguez, C., Cerezo, R., Fernández, E., Tuero, E., & Högemann, J. (2017). Analysis of instructional programs in different academic levels for improving self-regulated learning SRL through written text. Design Principles for Teaching Effective Writing, 201–231. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004270480_010

- Sandelowski, M. (1995). Sample size in qualitative research. Research in Nursing & Health, 18(2), 179–183. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.4770180211

- Scaglioni, S., De Cosmi, V., Ciappolino, V., Parazzini, F., Brambilla, P., & Agostoni, C. (2018). Factors influencing children’s eating behaviours. Nutrients, 10(6), 706. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10060706

- Simpson, C. C., Griffin, B. J., & Mazzeo, S. E. (2019). Psychological and behavioral effects of obesity prevention campaigns. Journal of Health Psychology, 24(9), 1268–1281. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105317693913

- Throsby, K. (2007). How could you let yourself get like that?: Stories of the origins of obesity in accounts of weight loss surgery. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 65(8), 1561–1571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.06.005

- Trainer, S., SturtzSreetharan, C., Wutich, A., Brewis, A., & Hardin, J. (2022). Fat is all my fault: Globalized metathemes of body self-blame. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 36(1), 5–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/maq.12687

- Wang, Y., Ding, Y., Song, D., Zhu, D., & Wang, J. (2016). Attitudes toward obese persons and weight locus of control in Chinese nurses: A cross-sectional survey. Nursing Research, 65(2), 126–132. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNR.0000000000000145

- Wason, K. D., Polonsky, M. J., & Hyman, M. R. (2002). Designing vignette studies in marketing. Australasian Marketing Journal, 10(3), 41–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1441-3582(02)70157-2

- Weiner, B. (1982). An attribution theory of motivation and emotion (pp. 223–245). Series in Clinical & Community Psychology: Achievement, Stress, & Anxiety.

- Weiner, B. (2012). An attributional theory of motivation and emotion. Springer Science & Business Media.

- World Health Organization. (2020). Healthy diet. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/healthy-diet

- World Health Organization. (2021). Obesity and overweight. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight