Abstract

Objective

There is a distinct lack of research regarding the relationship with the body in women with endometriosis, despite the condition involving significant changes to appearance and impaired bodily functionality. The current study aimed to understand how women with endometriosis feel about their body.

Methods and Measures

Participants completed an online survey with open-ended questions on how they feel about their body, physical appearance, and level of daily functioning.

Results

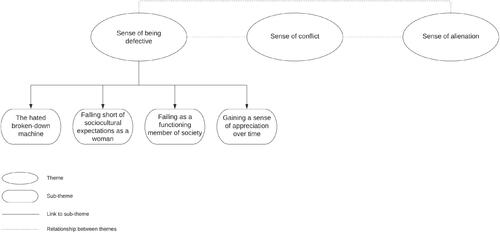

Responses from 315 women with endometriosis were analysed using reflexive thematic analysis, generating three themes: 1) ‘It makes me feel broken and inadequate’ (Sense of being defective); 2) ‘I feel like I’m in a war with it’ (Sense of conflict); and 3) ‘I feel like my body isn’t mine; it’s out of control’ (Sense of alienation).

Conclusion

The findings provide support for the notion that the relationship between the body and sense of self is particularly problematic for women with endometriosis and warrants therapeutic intervention. Future research should verify the efficacy of appreciation and self-compassion-based interventions for people with endometriosis.

Background

Endometriosis is a chronic health condition that affects approximately 1 in 9 Australian women by the age of 44 (Rowlands et al., Citation2021). Endometriosis occurs when cells similar to those that would usually line the uterus grow elsewhere in the body, such as in the ovaries, fallopian tubes, and pelvic organs, thickening, breaking down, shedding, and bleeding as per the menstrual cycle, and can result in physical symptoms including dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, bladder and bowel issues, abdominal bloating, and fertility issues (Jean Hailes, Citation2021). Endometriosis also has wide-reaching psychosocial impacts, with women with the condition showing significantly lower subjective wellbeing compared to members of the general population and other chronic health conditions (Rush & Misajon, Citation2018). However, there is a dearth of research examining the experience of body image for people with endometriosis.

Body image theories and chronic illness

Although there is no theory of body image among people with chronic illness, existing theories may be applicable to some extent, particularly elements of sociocultural theory and objectification theory. Sociocultural theory proposes that there are multiple sources of influence on an individual’s body image: peers, family, and the media (Thompson et al., Citation1999). The impact these factors exert on a person’s body image depends on the extent to which the person has adopted societal appearance standards as their own (i.e. thin ideal internalisation) and compares their body with others (i.e. appearance-based comparisons). Objectification theory is founded in the societal view that the purpose of a woman’s body is to serve as an object of enjoyment and sexual pleasure for men and that women are perpetually viewed this way by society at large (Fredrickson & Roberts, Citation1997). Being seen as an object by society is thought to lead women to view themselves as said object, wherein they adopt society’s third person view of themselves and give undue value and attention to their appearance. From an evolutionary perspective, it is thought that one reason why men objectify women is to assess their fertility, with instrumentality (i.e. in this case being seen as a tool to produce children) being one of the seven ways in which women can be viewed and treated as an object specifically (Nussbaum, Citation1995).

When women’s appearance or fertility is impacted due to a chronic illness, the pressures at play according to these body image theories are likely to be magnified. Countless studies have demonstrated that sociocultural theory and objectification theory help to explain how body image disturbance develops in women without chronic illnesses (e.g. Moradi & Huang, Citation2008; Rodgers et al., Citation2015), but the basic pathways may well be similar, and likely amplified. For people without chronic illness, the ways in which their body might deviate from the societal norm include elements such as their weight, general body shape, complexion, and muscle tone. For people with chronic illnesses that alter the way their body looks, such as with the surgical scarring or abdominal bloating that can come with endometriosis, these changes are likely to only add ways in which their bodies deviate from the societal ideal. Furthermore, for people who want to reproduce and are experiencing fertility issues, the difficulty or inability to bear a child may act as an additional factor determining their perceived value as a heteronormative woman.

Body dissatisfaction, body functionality, and endometriosis

Given the nature of endometriosis, two specific body image-related concepts may be particularly relevant, namely: body dissatisfaction and body functionality. Body dissatisfaction refers to feelings of discontent with one’s appearance, shape, or weight, and has been associated with disruptions to sense of wellbeing, self-esteem, and self-compassion (Ferreira et al., Citation2013). Approximately 20–40% of women in the general population report dissatisfaction with their body (Frederick et al., Citation2012). Although women have reported wanting a thinner body across all three phases of the menstrual cycle (pre-menstrual, menstrual, inter-menstrual), body dissatisfaction levels have been found to be highest during the pre-menstrual and menstrual phases, both of which are often characterised by abdominal bloating (Jappe & Gardner, Citation2009). Abdominal bloating is a common symptom of endometriosis with one study reporting 96% of women with endometriosis experienced abdominal bloating throughout one menstrual cycle, compared to 64% of women without endometriosis (Luscombe et al., Citation2009).

Although there is currently no empirical psychosocial investigation of the phenomenon, there are numerous anecdotal reports colloquially referring to ‘endo belly’, indicating that the swelling can be so extreme in some cases that other people presume the women to be pregnant (e.g. Larbi, Citation2019). It is therefore considered likely that the physical changes associated with endometriosis may contribute to feelings of unhappiness with one’s appearance. However, few studies to date have explored the body image experiences of women with endometriosis. Previous studies have found a relationship with worse body image in women with deep endometriosis (severe sub-type) (Melis et al., Citation2015), and dissatisfaction with appearance as a function of endometriosis-related symptoms or surgery side-effects in a focus group study with Australian women (Moradi et al., Citation2014). While these previous studies offer an initial exploration into endometriosis and body dissatisfaction, more work is needed to understand this relationship.

Whilst body dissatisfaction is an example concept of the traditional framing of body image known as negative body image, there have been recent advances in exploring another framework, known as positive body image. This approach focuses on positive ways of inhabiting one’s body, extending beyond the way the body looks to include how the body feels and functions (Tylka & Piran, Citation2019). Body functionality refers to the body’s abilities, including physical functioning (e.g. walking), general health and internal processes (e.g. digestion), bodily senses (e.g. hearing), creative pursuits (e.g. painting), self-care (e.g. showering and sleeping), and communicating with others (e.g. through body language) (Alleva et al., Citation2014). Previous research indicates that chronic conditions can lead to a reduced sense of body functioning, which influences how an individual perceives their body overall. For instance, individuals with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), a chronic pain condition that can affect both an individual’s appearance and abilities through swollen and sore muscles and joints, have reported feeling frustrated at being unable to function as they would like (Collins et al., Citation2013). However, Alleva et al. (Citation2018) found an intervention focusing on broadening the understanding of body functioning beyond physical limitations helped to improve the relationship individuals with RA had with their body and, at least in part, alleviate the dissatisfaction they felt towards their body. As such, it is thought that this sense of functioning appreciation, a key positive body image concept, can partially overcome the self-objectification experienced by people in the general population and with specific health conditions affecting the body (Alleva et al., Citation2018).

Currently, there is limited empirical evidence focusing on how women with endometriosis feel about their level of body functioning and whether body functioning may be a valid construct to target in interventions. As such, the aim of this paper is to address this paucity of research by asking women with endometriosis about their body image experiences and, in doing so, attempt to build an understanding of the relationship women have with their bodies, using a qualitative approach. Given women with endometriosis often experience considerable variety in their presentation, symptoms, and the corresponding impact on their psychosocial wellbeing, the current study was exploratory in nature and aimed to capture a sense of the common issues experienced. The current study was guided by the research question: ‘How do womenFootnote1 with endometriosis feelFootnote2 about their body?’.

Methodology

Design

Given the exploratory nature of this study and the individual complexity of endometriosis as a condition, an online qualitative survey was selected for the current study as the format allows participants to write freely, as much or as little as they wish, taking as much time to pause and reflect as they like (Braun & Clarke, 2013). Online qualitative surveys are also anonymous, making them ideal for capturing information on potentially sensitive topics such as endometriosis and body image. An additional benefit of this design is that it enables individuals to take part in the study with minimal effort, as opposed to participating in a face-to-face interview, which is especially appropriate for women with endometriosis whose mobility and energy may be impacted by symptoms. Online qualitative surveys have been successfully used in endometriosis samples in the past (Cole et al., Citation2021; Grogan et al., Citation2018).

Data collection

Following ethics approval from the Human Research Ethics Committee at the Cairnmillar Institute (approval number: 2018/11334/11338/11332), the study was promoted on social media and by contacting relevant support groups, such as Epworth Freemasons hospital, Endometriosis Australia, and Endometriosis New Zealand. To be included, participants needed to be women with endometriosis aged 18 or older. Once informed consent was obtained via the Plain Language Statement, participants completed general (i.e. age, gender, relationship status, level of education, and ethnicity) and endometriosis-specific (i.e. year and method of diagnosis, onset of symptoms, number of endometriosis-related surgeries, and most commonly experienced endometriosis symptoms) demographics. Participants were also asked three open-ended questions about their relationship with their bodies, specifically, ‘How has endometriosis affected the way you feel about your body in general?’, ‘How has endometriosis affected the way you feel about your physical appearance?’, and ‘How has endometriosis affected your daily body functioning? (i.e. daily tasks and other needs such as food, bowel movements, sexual functioning, including desire, arousal, pain intensity etc.)’. Participants wrote an average of 30 words in response to each of the questions, with response lengths ranging from 1 to 210. A mood repair task was given to the participants, whereby participants were asked to consider and enter five positive things in their life into textboxes, to help counteract any negative effect the questions may have invoked (e.g. Otway & Carnelley, Citation2013). Data was collected from January to May 2019.

Participant characteristics

A total of 315 people with endometriosis completed the online survey. Ages ranged from 18 to 63, with an average of 31.26 years. The two most commonly reported ethnicities were New Zealand (51; 16.19%) and Australian (45; 14.29%). The majority (170; 54%) were married or in a de facto relationship and had completed a Bachelor’s degree (113; 35.9%). Most reported receiving their diagnosis via laparoscopy (283; 89.84%). The reported duration of endometriosis symptoms experienced ranged from 1 to 40 years with an average of 15.37 years, and there was an average of 2.30 endometriosis-related surgeries (range 0-15). Participants reported an average delay in receiving a diagnosis of 9.82 years (range 0-39). Most participants indicated pain to be their worst endometriosis symptom (243; 77.14%).

Data analysis

Reflexive thematic analysis (RTA; Braun & Clarke, Citation2019) was the analysis method, which aims to identify common themes that address the issue and are relevant to the research question (Maguire & Delahunt, Citation2017). A critical realist ontological perspective informed the methodology (Braun & Clarke, Citation2022), with authors adopting a constructivist epistemological approach when analysing the data, recognising that it is inevitable that data will be viewed through certain social and personal lenses (Madill et al., Citation2000). An experiential orientation to data interpretation was taken to emphasise women with endometriosis’ own experiences and how they feel about their body, rather than the sociocultural factors underlying this experience. The analysis was predominantly inductive or open-coded in nature to best showcase the meaning behind what participants said in their responses, with some deductive analysis also used, where relevant, to ensure themes were more likely to be easily mapped onto existing concepts (Braun & Clarke, Citation2022). Both semantic and latent coding was used, reflecting intention to emphasise the participant experience whilst also acknowledging researcher contribution to interpreting the meaning behind the participant responses. Throughout the analysis process, Author 1 maintained a research journal to document initial thoughts regarding the data and regular methodological decisions, as well as to clarify their impressions of participant responses (Janesick, Citation1999).

Braun and Clarke (Citation2019) six-phase thematic analysis guide was used when analysing the data. Firstly, after the data were imported into NVivo, Author 1 became familiar with the entire body of data by reading through responses to each question twice and taking note of early impressions so that initial codes could be systematically organised early. Secondly, short labels were generated and assigned to responses as applicable. Once all data was coded, Author 1 reviewed the first draft of codes to assess overlap, collapsing codes where appropriate, grouping codes, and creating early themes based on threads of commonality. In the fourth phase, themes underwent multiple revisions to ensure they each represented coherent, meaningful interpretations of the data that addressed the research question. The next phase of finalising the thematic framework involved confirming each theme’s name and definition. To do this, Author 1 re-read the data that fell within each theme to ensure a well-rounded understanding of what was being encapsulated. Theme titles went through multiple iterations. Throughout the process, codes and themes were reviewed several times by collaborative discussion with Authors 2 and 3, to sense-check. The final phase of RTA began informally throughout Author 1’s research journal and culminated in presenting the themes in the most logical manner below. The analysis was completed predominantly by Author 1, as is typical of RTA (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019).

It is integral to consider the positionality of the authors involved in the data analysis to acknowledge the inevitable influences on the process (Holmes, Citation2020). None of the authors have an endometriosis diagnosis and, while they may have experience with other chronic illnesses, are outsiders. All authors identify as cisgender. In addition, Author 1, a self-identified feminist, has a research background in understanding body image experiences and the impact of societal systems.

Findings

Themes reflecting how women with endometriosis feel about their body

Three themes regarding women’s relationships with their bodies were identified from participants’ responses: 1) ‘It makes me feel broken and inadequate’ (Sense of being defective), with four subthemes of a) The hated broken-down machine, b) Falling short of sociocultural expectations as a woman, c) Failing as a functioning member of society, and d) Gaining a sense of appreciation over time; 2) ‘I feel like I’m in a war with it’ (Sense of conflict); and 3) ‘I feel like my body isn’t mine, it’s out of control’ (Sense of alienation), which are detailed below with illustrative quotes. Any typographical errors in quotes were corrected to improve readability. The thematic map can be seen in .

Theme 1: ‘it makes me feel broken and inadequate’ (sense of being defective)

In the first instance, the brutality of the physical experiences of endometriosis led women to feel like they were fundamentally broken or incomplete. Feeling broken was accompanied by feelings of failure, manifested in two distinct ways: failing as a woman and failing as a contributing member of society. Coupled with this self-assessment as a failure was an undermined sense of identity for some, with many sharing more of an affinity with a machine than a person. Some women were able to view their body from a different, more adaptive perspective, thereby shifting the focus from a sense of brokenness to recognising the body’s capabilities in light of endometriosis, engendering feelings of respect and appreciation towards the body. For the majority of women, though, they felt their bodies were left wanting in some capacity. Theme 1 houses four subthemes, the first of which expounds on the feeling of identifying as a broken piece of machinery rather than a human being and/or a woman. The next two subthemes detail two key ways in which women with endometriosis feel they have failed, before the last subtheme explores a possible reframing that may help women with endometriosis change the way they view their body over time.

Subtheme 1: the hated broken-down machine

Many women wrote about feeling not only that their body was abnormal or different in some way, but that it was fundamentally ‘broken’, ‘defective’, ‘damaged’, ‘deteriorating’, ‘a dud’. This sense of feeling like a malfunctioning piece of machinery was reinforced by the idea of surgery being presented as a solution; by removing the endometriosis growths or, in more extreme cases, having a hysterectomy, women could be ‘patched up’. However, for some, this surgical solution was either not practical, or associated with only temporary relief, no relief, or worse outcomes. For these individuals, the sense of being broken continued, but with an added feeling of hopelessness.

I had stage 4 endo and on my bowel and my surgeons tell me it was very advanced, that I will most likely get it back. None of my endo symptoms have gone away after surgery so it feels like I spent all that money, pain, and time for nothing. I feel like my body lets me down no matter what I try and do

Some women reported feeling as though they have been failed by their body, and that they are failing other people, perpetuating a sense of shame and a strong dislike towards the body. Pointedly, women reflected on feeling worse about their body as a function of endometriosis than before they had symptoms. For example, one participant explained: ‘I hate my body even more than I used to. I hated the way it looked but now I hate the way it feels. I feel trapped and I don’t want it anymore.’. This hatred was occasionally directed at specific body parts (‘I feel deep hatred towards the body parts that hurt me, especially the uterus and abdominal area’.), but typically at the body as a whole (‘[Endometriosis] has made me hate my body in general as having chronic pain just makes everything worse’).

Subtheme 2: falling short of sociocultural expectations as a woman

This subtheme is related to feeling as though the body is ‘not working as it should’ as a woman. Many of the participants felt they failed to meet beauty standards, such as the thin ideal. However, there are numerous other heteronormative societal expectations for how women should act that are affected by the condition, with perhaps the most pertinent being the ability to bear children. For participants wanting children, having difficulty or being unable to conceive due to endometriosis led to feeling like less of a woman:

…when I start thinking of fertility issues I may have, I feel like a failure as a woman, that the one thing I should be able to do if I choose (i.e. have kids) may not be an option. An option I don’t get to choose but one made for me. I feel almost defective as woman.

It was apparent that many women sourced some portion of their sense of identity from certain physical features and/or functions, i.e. having female reproductive organs, being capable of bearing children, and being able to have sex (for themselves, but also for their partner/s). Through socialisation, the latter two functions were often considered ‘givens’ that women are expected to be able to do happily and easily. When women are unable to do one or both, such as the case with endometriosis, it can cause them to question their very identity.

Subtheme 3: failing as a functioning member of society

This third subtheme is concerned with how women with endometriosis feel their bodies have affected their ability to function as an average human being, as distinct from a woman specifically. Participants described many elements of daily life that the average person takes for granted as difficult or impossible for people with endometriosis, including maintaining a job, building a career, balancing work, family, and studying, as well as socialising: ‘Endometriosis has affected every aspect of my life, including relationships, work, eating, sleeping, socializing, being active, sex, voiding, showering, relaxing, even how I move. It sucks’.

Many participants described how pain, fatigue, and/or brain fog associated with the condition prevented them from being able to keep a job, let alone progressing a career, with many women having to change their line of work or employment fraction, for example ‘… heavy bleeding has meant I’ve lost jobs’.; ‘I had to quit my job as a child care working due to debilitating pain after being at work for only an hour’. Regularly taking sick days from a job for pain, fatigue, or post-surgery recovery also resulted in concerns of being perceived as an unreliable or uncommitted employee: ‘Sick days at work were the norm which may have reflected a poor work ethic when that was not the case’.

Participants reported that the impact of endometriosis on their diet and digestion further limited their ability to comfortably socialise with others, with many having to limit or avoid certain foods: ‘I have many gut issues since, alternating diarrhea and constipation, which can make going out stressful and makes eating not as enjoyable as I’m not sure how my body will react!’. The need to consider the possible consequences of what they might eat or needing to adhere to specific diets means women may be restricted in terms of where they can socialise or may simply opt to not go out:

I have had to change my diet to low FODMAP which severely restricts my ability to eat what I want or eat out with friends. The painkillers I take sap my energy. I often have to cancel plans with friends at the last minute which leaves them frustrated with me.

Women described feeling trapped by their bodies, both in a metaphorical sense and a literal sense, often feeling incapable or unwilling to leave their house. This was often due to pain and/or fatigue: ‘I was in copious amounts of pain, unable to sleep and would often faint and be sick. I became isolated, not wanting to go out much due to the level of pain I was experiencing.’; ‘My endometriosis pain leads me to want to become recluse, and stay in bed and eat bad foods’.

Many women with endometriosis described living a half-life, unable to operate in society as ‘normal’ or expected, due to the considerable constraints the condition places on virtually every aspect of their life.

Subtheme 4: gaining a sense of appreciation over time

This subtheme acknowledges and explores the finding that a small but non-trivial number of women reported that their endometriosis brought about increased understanding of and respect for their body. Rather than a simple antithesis to the main theme, this subtheme is instead about some women’s ability to simultaneously hold the bodily pain and devastation caused by endometriosis in one hand and either a burgeoning or a profound appreciation for their body’s endurance in the other. In other words, this appreciation grew from participants’ initial experiences of feeling broken or inadequate, with some stating the diagnosis has helped them learn to accept and understand their body for what it has become. As one woman wrote:

It’s developed a stronger love/hate relationship. There are days I look at my body…and feel sad…But then there are good days where it empowers me, I feel mentally stronger that I can manage to do so much with all this going on and I look at my body with somewhat pride and acceptance.

I think it has oddly taught me to be more accepting of my physical appearance. Because I am in pain and am tired so much, I stopped wearing make up to try and hide how I felt. Now I just accept and embrace that if I feel tired or unwell, it’s okay to look a bit tired and I don’t need to hide that for anyone or myself.

I think that endometriosis can leave me feeling very frustrated with my body due to the level of pain that I am frequently in but also feel very grateful that despite this and the struggle, that I have been able to have two children. Something I never thought would happen.

Theme 2: ‘I feel like I’m in a war with it’ (sense of conflict)

Women felt as though the body was a battleground, host to a tug of war between their mind and body, their expectations and reality, as well as their pain and their resources, with one woman remarking ‘I feel like I am fighting it, it’s a second job living in my body, I have nothing positive to say about how it works’. For those participants experiencing almost constant pain or discomfort, a chronic hypervigilance was instilled, characterised by a heightened awareness of their body and their pain that was punctuated with periods of acute distress during a flare-up. For example, one participant reported an increase in self-surveillance: ‘I can’t help running a hand over my pelvis every now and then, as if to “pat” down and check any bloating’.

The continual battle of living with endometriosis can add considerable cognitive and emotional load. Participants wrote about perpetual preparation and planning, whether this was regarding how they were going to use their finite energy reserves, what they were going to eat in an attempt to avoid painful bowel movements, or where the nearest public amenities were, for example: ‘I have to plan my daily tasks carefully as I’m only capable of doing so much in a day.’; ‘I now have to plan my day around the location of the bathroom’.

Participants also referred to the additional cognitive and emotional labour of having to mentally steel themselves for the perceived inevitability of pain: ‘I have to prepare myself mentally if I’m going to have intercourse as it can be painful’; ‘If I need to have a comfortable bowel movement, or sexual experience it takes preparation’, and to shield other people from the realities of their painful experience ‘I am mentally drained most of the time trying to manage my pain and work 40 h a week with three children and still try to present okay, so they don’t worry’. When interacting with strangers in public, women seemed to feel bound by society’s norms around expressing pain and feel obliged to put on a front. For example:

My stomach is bloated, and I walk funny to try and act normal with the pain. Sometimes in the supermarket I will crouch to "read the ingredients" on a product, while, really, I’m wincing through a flare up. Trying to act normal, not to draw attention.

Theme 3: ‘I feel like my body isn’t mine; it’s out of control’ (sense of alienation)

The third theme represents the disconnect women with endometriosis can feel between themselves and their body. Participants described feeling as though their bodies were no longer theirs—they no longer own, control, or recognise their bodies. Instead, they felt another entity was in charge of their body, their actions, and their life, with one woman describing the experience as though: ‘…my body is clearly possessed by a demonic hell demon’. Endometriosis has rendered their body, or at least parts of it, unfamiliar to them:

It has made me feel like my womb is a foreign body to me. Something I have no control over and no desire for anymore. It is torture, it’s evil, it’s life destroying, and it is constant. I don’t feel like me; I feel like a shell of my former self.

Certain tasks like hanging the washing out or cleaning, any sudden movements like sneezing or twisting, can cause severe [pain] in my abdomen which makes me instantly curl up in agony. I can go from being starving to completely nauseous in minutes.

What limited steps women can take to try to mitigate the effects of the condition are often unsuccessful, when endometriosis appears for some to have a ‘mind of its own’. The fluctuating nature of the condition and its impacts on the body mean that, accordingly, the way women feel about their body can differ from moment to moment.

I find it difficult to have one ‘true’ feeling about my body because it changes constantly. One day I can feel happy and healthy and care-free and really take care of myself, the next I am in debilitating pain with ‘endo-belly’ and swelling. Other times I may look like I’m ok but underneath my floaty dress is my swollen endo-belly and I’m surviving that day on pain killers. It is incredibly hard to feel a consistent way towards my body when it changes so rapidly.

The speed with which endometriosis can change and the unpredictable nature of the changes, as well as the multiple life domains impacted, all act to reinforce views that the body is out of their control and, instead, that their body is controlling them. As one participant put it: ‘[Endometriosis] affects every moment, what I can eat, can I sit or stand, can I take pain relief or not, can I sleep, are my joints sore, can I have sex, can I talk about it, am I sad?’. Participants reported lack of control over their weight, appetite, diet, physical movement, socialising, sex life, family planning, study, or work. Even clothing choice was determined by endometriosis, avoiding wearing certain clothes due to bloating-related discomfort:

I have effectively 2 sets of clothes - those that fit in the first half of my cycle and those that fit in the second half to accommodate bloating. I now wear elasticated waistbands where possible.

I am under 30 but feel like I’m 80. I am tired and become exhausted after small tasks. Require help with most daily activities like cooking and cleaning.

As a young adult, unable to meet friends because I couldn’t leave the house because of pain, this was not the way it was supposed to be

One woman reflected that the disconnection between herself and her body was itself a way of dealing with the pain from endometriosis, whilst others attempted to cope with this disconnect between the body and the mind by essentially engaging in wishful thinking and desiring a different body to theirs: ‘I feel like my body isn’t mine. It’s out of control. I want a replacement’. For others, separating endometriosis from the body was helpful: ‘Over the years, I’ve come to accept that it [body] is not [hideous]; that the disease itself is hideous’. In fact, actively anthropomorphising endometriosis and giving the condition an identity provided a way of coping with the havoc being wreaked on their body: ‘[Endometriosis] has explained a lot and I have named it Edna in a way to deal with the squatter!’.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to examine how women with endometriosis felt towards their body. Results indicate that women with endometriosis have a complex and fraught relationship with their body, as a function of the condition, revealing three key themes relating to a sense of defectiveness specifically as a woman and generally as a human, a sense of constant conflict of them versus their body, and a sense of alienation from their body and separation of their mind and body.

The findings were overwhelmingly negative, suggesting that women with endometriosis constitute a subgroup of the population that may be at higher risk of suffering from severe body image issues. It appears that women with endometriosis are likely to feel the usual ‘normative discontent’ (Rodin et al., Citation1984) experienced by the average woman in Western society, but with additional discontent caused by endometriosis. This aligns with a recent quantitative study showing people with endometriosis report worse body image than people without (Volker & Mills, Citation2022). Furthermore, this endometriosis-specific discontent seems to have two components: 1) appearance-related elements, due to bloating, surgical scarring, and weight gain, and 2) functionality-related elements, such as difficulties with general mobility, digestion, personal hygiene, sexual activity and fertility. It is perhaps the combination of these two forms of dissatisfaction—feeling dissatisfied with the way one looks and the functional limitations one experiences - that contributes to a sense of disconnection between the self and the body among those with endometriosis. This sense of body-separation extends upon earlier work by Melis et al. (Citation2015) suggesting that severity of pain was associated with women becoming unfamiliar with their body.

Underlying this discontent with the body is the objectification of women in society. Women transition from being a someone to a something; an object for men’s and society’s use and pleasure (Fredrickson & Roberts, Citation1997; Nussbaum, Citation1995). Many women hold an objectified perception of self by default and endometriosis can further distort this self-view as a broken something. Women may feel their body is not fit for purpose in terms of its appearance (not meeting the thin ideal) and as a sexual and fertile object. The frequent framing of their body as broken and defective only reinforces the extent to which these women objectified their bodies, ultimately viewing themselves as malfunctioning machines. Furthermore, objectification theory proposed that women are alienated from their bodies in terms of being able to feel and identify physical sensations (Fredrickson & Roberts, Citation1997).

Results from our study echo findings from the literature on body image in other chronic pain conditions, for example, women with RA show higher body dissatisfaction than women without RA (Jorge et al., Citation2010). Specifically, individuals with RA report diminished body-self harmony and high body-self alienation (Bode et al., Citation2010), with women with RA deeming the body a ‘separate adversary’ holding them back from their personal wants and needs (Alleva et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, for individuals with RA, the stronger this disconnect between the body and the self, the more difficult it was to manage the pain and reduced functionality associated with the condition (Bode et al., Citation2010). These findings resonate with the current study in that, for many, the endometriosis-affected body was perceived as distinct from the self and as an enemy. However, unlike the existing literature on RA, we also found that some people with endometriosis go beyond this and intentionally view the condition as distinct from both their body and their sense of self. This compartmentalisation of endometriosis as something external from both the body and self is a method of coping which shares similarities with personification of chronic physical illnesses such as lupus (Schattner et al., Citation2008), as well as mental health disorders, such as anorexia nervosa, often personified as ‘Ana’ (Abelskov, Citation2008). However, it remains unclear if this is an effective coping strategy for people with endometriosis.

To further our understanding of the relationship between endometriosis and body image, one next step is to quantify the findings from the current study by assessing appearance dissatisfaction, functionality dissatisfaction, and body harmony and alienation levels in women with endometriosis. Findings should be considered in comparison to the general population, individuals with other chronic pain conditions, such as varied types of arthritis, fibromyalgia, and Crohn’s disease, as well as other conditions impacting women’s health specifically (e.g. polycystic ovarian syndrome). Doing so will help determine the extent of any shared experiences and therefore any potential for similar intervention approaches, or whether endometriosis-specific approaches are warranted. Ascertaining whether the body image concerns experienced by women with endometriosis negatively impact other aspects of their wellbeing, including depression and anxiety, both of which are common comorbidities in this population (Pope et al., Citation2015), would assist in untangling the relationship between endometriosis and mental health.

Although the majority of women in the current study reported feeling negatively about their body, a small number described learning to hold positive views over time. This transition from pain to acceptance and gratitude holds similarities with positive growth following trauma and highlights the potential relevance for concepts like resilience in people with endometriosis. For instance, patients with cancer have shown that the more their body has changed as a function of the disease and treatment and, in turn, the worse their body self-image has been, the more resilience they have developed in response (Godoys et al., Citation2020). Additionally, resilience has been identified as a significant buffer against body image disruptions in women post-mastectomy (Izydorczyk et al., Citation2018). It follows that the experience of endometriosis can be viewed as a trauma for some, and that psychological resilience, including the practice of benefit finding, such as we saw in our data with some participants able to identify the silver linings of their diagnosis, is a skill that can develop over time, allowing the possibility for post-traumatic growth within this subgroup.

Implications

These findings demonstrate there is a critical need to address body image concerns in people with endometriosis. Much of the research on endometriosis has focused on determining the cause, cure, and treatment from a biomedical perspective. While this is vital work, the current study clearly highlights the negative impact the condition presently has on the psychosocial wellbeing of many women. Indeed, there is an urgent need to investigate ways to ameliorate this impact, particularly in the absence of an effective cure or treatment. By improving the body image outcomes of individuals with endometriosis, the considerable cognitive load associated with the condition may be at least partially alleviated, potentially making it easier for women to focus on the management of the condition more broadly.

The limited number of women in the current study who spoke positively about their body image did so in relation to appreciation and self-compassion. These findings suggest that by developing a sense of understanding of their bodies, women were able to positively reframe their experience of living with endometriosis. Given this, and the establishment of self-compassion as a protective factor against body dissatisfaction (Albertson et al., Citation2015), investigation into appreciation- and self-compassion-based body image interventions is warranted. For example, an online self-compassion-based intervention for breast cancer survivors successfully addressed body image discontent stemming from breast removal via mastectomy, scarring from surgery, or lymphedema (Sherman et al., Citation2018). It is worthwhile examining the potential of such a self-compassion-based body image intervention to improve the relationship with the body for women with endometriosis. Similarly, positive body image interventions that encourage women to accept and respect their body, regardless of its perceived imperfections, (i.e. body appreciation) and focus on what their body is capable of doing on good days or even on bad days, despite endometriosis (i.e. functionality appreciation), may help encourage a sense of gratitude and improve the connection with the body. Furthermore, a recent systematic review of mind-body interventions and their efficacy in improving psychological distress associated with endometriosis found that, although the research area is in its infancy, mind-body interventions hold promise (Evans et al., Citation2019).

Limitations

A limitation of the study is that we did not capture the gender identity of participants, to the unintentional exclusion of people with endometriosis who identify as non-binary. The experience of the body for people with endometriosis who identify as non-binary is likely to be distinctly nuanced compared to that of people who identify as cisgender, and as such, should be the focus of future work. In addition, the current study did not capture participants’ sexual orientation. Given the impact of endometriosis on sexual functioning, more targeted research explicitly exploring the impact of endometriosis on sexual functioning across a range of sexual contexts is warranted.

Endometriosis literature is largely built on samples of White women, resulting in a potentially biased characterisation of endometriosis symptom presentation and experience (Bougie et al., Citation2019). Our sample too was mainly White. Future research on more diverse populations is needed. In addition, although the online nature of the current study was chosen specifically for its benefits in allowing participants to discuss their experiences anonymously in as much or as little detail as they felt comfortable, the methodology did not provide the opportunity for follow-up questions to encourage elaboration, clarification, and exploration of certain avenues in more depth (Braun & Clarke, 2013). Therefore, future research should consider methodologies that allow for this.

Conclusion

The findings of this study highlight the negative impact endometriosis has on women’s body image and depict a complex, difficult, and often fractured relationship between women’s sense of self and their body. However, the findings also highlight that it is possible for some women with endometriosis to develop a sense of appreciation or gratitude towards their body. As such, future research should aim to ascertain whether self-compassion-based interventions are beneficial for reducing body appearance- and functionality dissatisfaction and increasing body-self harmony among women with endometriosis.

Authors’ contributions

Jacqueline Mills: Conceptualisation, Writing (Review & Editing), Formal Analysis, Data Curation, Project Administration, Supervision ChellChih Shu: Writing (Original Draft), Data Curation, Formal Analysis RoseAnne Misajon: Conceptualisation, Formal Analysis, Writing (Review & Editing) Georgia Rush-Privitera: Writing (Review & Editing).

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Data availability statement

Due to the nature of this research, participants did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The authors wish to acknowledge that not all people with endometriosis identify as women. This study captured a sample of people identifying as women with endometriosis, however, this will not reflect the breadth of experiences of people with endometriosis.

2 The authors note that while the word “feel” traditionally refers to emotions experienced, it is being used in the more colloquial sense in the current research question and analysis to mean emotions, attitudes, perceptions, and thoughts. This aligns with the way the word appeared to be used by participants in their responses.

References

- Abelskov, A. C. (2008). Anorexia—In between illness and identity. Sygeplejersken/Danish Journal of Nursing, 108(18), 44–47.

- Albertson, E. R., Neff, K. D., & Dill-Shackleford, K. E. (2015). Self-compassion and body dissatisfaction in women: A randomized controlled trial of a brief meditation intervention. Mindfulness, 6(3), 444–454. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-014-0277-3

- Alleva, J. M., Diedrichs, P. C., Halliwell, E., Peters, M. L., Dures, E., Stuijfzand, B. G., & Rumsey, N. (2018). More than my RA: A randomized trial investigating body image improvement among women with rheumatoid arthritis using a functionality-focused intervention program. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 86(8), 666–676. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000317

- Alleva, J. M., Martijn, C., Jansen, A., & Nederkoorn, C. (2014). Body language: Affecting body satisfaction by describing the body in functionality terms. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 38(2), 181–196. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684313507897

- Bode, C., van der Heij, A., Taal, E., & van de Laar, M. A. F. J. (2010). Body-self unity and self-esteem in patients with rheumatic diseases. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 15(6), 672–684. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2010.507774

- Bougie, O., Healey, J., & Singh, S. S. (2019). Behind the times: Revisiting endometriosis and race. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 221(1), 35.e1-35–e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2019.01.238

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. SAGE Publishing.

- Cole, J. M., Grogan, S., & Turley, E. (2021). The most lonely condition I can imagine”: Psychosocial impacts of endometriosis on women’s identity. Feminism & Psychology, 31(2), 171–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353520930602

- Collins, S., Wilkinson, K., Bosworth, A., & Jacklin, C. (2013). Emotions, relationships, & sexuality. https://nras.org.uk/resource/emotions-relationships-sexuality/

- Evans, S., Fernandez, S., Olive, L., Payne, L. A., & Mikocka-Walus, A. (2019). Psychological and mind-body interventions for endometriosis: A systematic review. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 124, 109756. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2019.109756

- Ferreira, C., Pinto-Gouveia, J., & Duarte, C. (2013). Self-compassion in the face of shame and body image dissatisfaction: Implications for eating disorders. Eating Behaviors, 14(2), 207–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.01.005

- Frederick, D. A., Jafary, A. M., Gruys, K., & Daniels, E. A. (2012). Surveys and the epidemiology of body image dissatisfaction. In Cash, T. (Ed.), Encyclopedia of body image and human appearance (pp. 766–774). Academic Press.

- Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T.-A. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21(2), 173–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x

- Godoys Lins, F., Barcelos do Nascimento, H., Corrêa Sória, D., de, A., & de Souza, S. R. (2020). Self image and resilience of oncological patients. Revista de Pesquisa Cuidado é Fundamental Online, 12(1), 492–498. https://doi.org/10.9789/2175-5361.rpcfo.v12.8565

- Grogan, S., Turley, E., & Cole, J. (2018). So many women suffer in silence’: A thematic analysis of women’s written accounts of coping with endometriosis. Psychology & Health, 33(11), 1364–1378. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2018.1496252

- Holmes, A. G. D. (2020). Researcher positionality—A consideration of its influence and place in qualitative research—A new researcher guide. Shanlax International Journal of Education, 8(2), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.34293/education.v8i4.3232

- Izydorczyk, B., Kwapniewska, A., Lizinczyk, S., & Sitnik-Warchulska, K. (2018). Psychological resilience as a protective factor for the body image in post-mastectomy women with breast cancer. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(6), 1181. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15061181

- Janesick, V. J. (1999). A journal about journal writing as a qualitative research technique: History, issues, and reflections. Qualitative Inquiry, 5(4), 505–524. https://doi.org/10.1177/107780049900500404

- Jappe, L., & Gardner, R. (2009). Body-image perception and dissatisfaction throughout phases of the female menstrual cycle. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 108(1), 74–80. https://journals-sagepub-com.ezproxy-f.deakin.edu.au/doi/abs/10.2466/pms.108.1.74-80

- Hailes, J. (2021). Endometriosis symptoms & causes. Jean Hailes. https://www.jeanhailes.org.au/health-a-z/endometriosis/symptoms-causes

- Jorge, R. T. B., Brumini, C., Jones, A., & Natour, J. (2010). Body image in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Modern Rheumatology, 20(5), 491–495. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10165-010-0316-4

- Larbi, M. (2019). Women share pics of bloated bellies to show reality of living with endometriosis. The Sun. https://www.thesun.co.uk/fabulous/8986666/endometriosis-bloated-bellies/

- Luscombe, G. M., Markham, R., Judio, M., Grigoriu, A., & Fraser, I. S. (2009). Abdominal bloating: An under-recognized endometriosis symptom. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada: JOGC = Journal D’obstetrique et Gynecologie du Canada: JOGC, 31(12), 1159–1171. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1701-2163(16)34377-8

- Madill, A., Jordan, A., & Shirley, C. (2000). Objectivity and reliability in qualitative analysis: Realist, contextualist and radical constructionist epistemologies. British Journal of Psychology, 91(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1348/000712600161646

- Maguire, M., & Delahunt, B. (2017). Doing a thematic analysis: A practical. Step-by-Step Guide for Learning and Teaching Scholars, 8(3), 14.

- Melis, I., Litta, P., Nappi, L., Agus, M., Melis, G. B., & Angioni, S. (2015). Sexual function in women with deep endometriosis: Correlation with quality of life, intensity of pain, depression, anxiety, and body image. International Journal of Sexual Health, 27(2), 175–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/19317611.2014.952394

- Moradi, B., & Huang, Y.-P. (2008). Objectification theory and psychology of women: A decade of advances and future directions. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 32(4), 377–398. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2008.00452.x

- Moradi, M., Parker, M., Sneddon, A., Lopez, V., & Ellwood, D. (2014). Impact of endometriosis on women’s lives: A qualitative study. BMC Women’s Health, 14(1), 123. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6874-14-123

- Nussbaum, M. (1995). Objectification. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 24(4), 249–291. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1088-4963.1995.tb00032.x

- Otway, L., & Carnelley, K. (2013). Exploring the associations between adult attachment security and self-actualization and self-transcendence. Self and Identity, 12(2), 217–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2012.667570

- Pope, C. J., Sharma, V., Sharma, S., & Mazmanian, D. (2015). A systematic review of the association between psychiatric disturbances and endometriosis. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada: JOGC = Journal D’obstetrique et Gynecologie du Canada: JOGC, 37(11), 1006–1015. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1701-2163(16)30050-0

- Rodgers, R. F., McLean, S. A., & Paxton, S. J. (2015). Longitudinal relationships among internalization of the media ideal, peer social comparison, and body dissatisfaction: Implications for the tripartite influence model. Developmental Psychology, 51(5), 706–713. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000013

- Rodin, J., Silberstein, L., & Striegel-Moore, R. (1984). Women and weight: A normative discontent. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 32, 267–307.

- Rowlands, I., Abbott, J., Montgomery, G., Hockey, R., Rogers, P., & Mishra, G. (2021). Prevalence and incidence of endometriosis in Australian women: A data linkage cohort study. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 128(4), 657–665. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.16447

- Rush, G., & Misajon, R. (2018). Examining subjective wellbeing and health-related quality of life in women with endometriosis. Health Care for Women International, 39(3), 303–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2017.1397671

- Schattner, E., Shahar, G., & Abu-Shakra, M. (2008). I used to dream of lupus as some sort of creature’: Chronic illness as an internal object. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 78(4), 466–472. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014392

- Sherman, K. A., Przezdziecki, A., Alcorso, J., Kilby, C. J., Elder, E., Boyages, J., Koelmeyer, L., & Mackie, H. (2018). Reducing body image–related distress in women with breast cancer using a structured online writing exercise: Results from the My Changed Body randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, 36(19), 1930–1940. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2017.76.3318

- Thompson, J. K., Heinberg, L., Altabe, M., & Tantleff-Dunn, S. (1999). Exacting beauty: Theory, assessment and treatment of body image disturbance. American Psychological Association.

- Tylka, T. L., & Piran, N. (2019). Focusing on the positive: An introduction to the volume. In T. L. Tylka & N. Piran (Eds.), Handbook of positive body image and embodiment (pp. 1–8). Oxford University Press.

- Volker, C., & Mills, J. (2022). Endometriosis and body image: Comparing people with and without endometriosis and exploring the relationship with pelvic pain. Body Image, 43, 518–522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2022.10.014