Abstract

Background

Around twenty percent of meningitis survivors experience after-effects. However, very little research on their psychological impact has been conducted. This report details a small explorative investigation into these psychological impacts.

Objective

To explore the impact sequelae have on the meningitis survivors affected.

Methods and measures

Thematic analysis of one-hundred individual user’s blog posts, self-reporting one or more sequelae after a diagnosis of meningitis.

Results

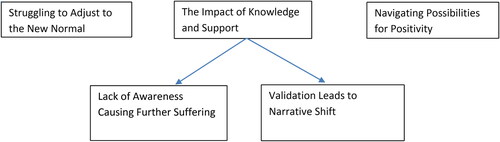

Blog posters’ experiences varied greatly. Common trends in experience were mapped onto three themes. ‘Struggling to Adjust to the New Normal’ captures blog posters’ struggles in returning to their lives post-hospitalization. ‘Navigating Possibilities for Positivity’ explores how blog posters either reported positive change due to their illness experience or felt a pressure, or inability, to do so. ‘The Impact of Knowledge and Support’ overarching two sub-themes; ‘Lack of Awareness Causing Further Suffering’ and ‘Validation Leads to Narrative Shift’. These sub-themes contrast differences in experience blog posters reported, with and without knowledge, of the cause of their symptoms and support in dealing with the resulting difficulties.

Conclusions

Consistent and structured after-care would benefit patients experiencing sequelae. Suggestions of a possible format this could take are put forward. In addition, self-regulatory models of illness perception help explain some variations in blog posters experiences, with possible intervention plans based on these models also suggested. However, limitations, including the comparatively small and highly selected sample, mean that further research is necessary to validate the findings and assess their validity, widespread applicability, and financial feasibility.

Introduction

Meningitis is a relatively rare but severe illness characterized by acute inflammation in the meninges area of the brain and spinal cord that can lead to blood poisoning through septicemia (Wallace et al., Citation2007). Around ten percent of people who contract meningitis die within forty-eight hours. In survivors, up to twenty percent experience one or more long-term sequelae, including amputation of limbs and digits, skin grafts, hearing and sight loss, neuromotor disability, gaps and lapses in all forms of memory, learning and behavioral difficulties, PTSD, anxiety, and depression (Olbrich et al., Citation2018; Schiess et al., Citation2021; Svendsen et al., Citation2020).

In 2017, the World Health Organization (WHO) developed a task force, ‘Defeating Meningitis by 2030’, aiming to reduce deaths by 70% and improve the quality of life of those living with after-effects (Greenwood et al., Citation2021). Since the early 2000s, the development and rollout of vaccines to target specific serogroups of meningitis have slowly reduced the number of cases worldwide (Taha et al., Citation2022). However, the meningitis B serogroup is only currently being mass-vaccinated in high-risk populations in the UK, Ireland, Italy, Andorra, Malta, and San Marino, meaning herd immunity is unlikely to be achieved (Martinón-Torres et al., Citation2022; Nadel & Ninis, Citation2018). Furthermore, increased vaccine hesitancy in the wake of the Covid 19 pandemic is a further challenge for the WHO to achieve these ambitious targets (Taha et al., Citation2022).

The debate around how cost-efficient further meningitis vaccine rollout would be is hindered by a need for more information on the long-term societal costs of people living with sequelae. Wang et al. (Citation2018) found substantial costs to healthcare systems dealing with meningitis in its acute phase but could not estimate costs in long-term care due to a lack of accurate records. Of the few studies that have documented the long-term (5 years +) impact of the disease, it has been noted that milder cognitive and behavioral difficulties following meningitis are often undiagnosed for years, impacting study and work performance (Schiess et al., Citation2021).

Previous studies of survivors of bacterial meningitis in childhood describe significant behavioural problems and lower Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQOL) (Sumpter et al., Citation2011). In addition, meningitis survivors are four and a half times more likely than the general population to suffer a major disabling deficit (9% to 2%), and over twice as likely to suffer with milder deficits (36% to 15%) (Viner et al., Citation2012).

Olbrich et al. (Citation2018) systematically reviewed 31 previously conducted observational studies. The review confirmed long-term reduced HRQOL in survivors, their families, and caregivers, recommending further studies to bridge data gaps, particularly in adolescent and adult HRQOL. However, difficulties in researching this area, including the small number of meningitis patients, the wide range of presenting sequelae and severity between cases, and the limitations of existing QoL measures in accurately assessing the long-term burden of deficits, have been identified (Marten et al., Citation2019).

While quantitative studies have greatly enhanced our understanding of various physical and neurological sequelae, personal experiences of psychological adaptation to meningitis are relatively lacking in academic literature (Scanferla et al., Citation2020).

Wallace et al. (Citation2007) conducted interviews with eleven adolescents who experienced scarring or skin grafts after contracting septicemia and analyzed them using Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA). The study highlighted the traumatic impact of altered appearance and the possibility that this is particularly problematic for adolescents. Scanferla et al. (Citation2020) conducted another IPA analysis of interviews with nine survivors across ages, years since illness onset, and meningitis serogroups. A follow-up study (Scanferla et al., Citation2021) used the same technique in interviews carried out with ten mothers and one grandmother of survivors of acute bacterial meningitis in childhood; this highlighted not only the continuing physical and psychological struggles experienced by their children but their own feelings of helplessness in the acute phase, and need for psychological support going forward, as well as the life-changing impact the event has had on survivors siblings. Previous research shows meningitis as a traumatic event with often permanent consequences for survivors and their families, with a broader cost burden on society.

The present study aims to extend previous findings by compiling data from public blog sites used by meningitis survivors, selecting material by blog posters self-reporting as living with sequelae. This approach allows for a larger sample size than previous qualitative studies, accessing a potentially vast source of previously unexplored information (Wilson et al., Citation2015) to answer the question: how does living with sequelae impact the lives of meningitis survivors? More precisely, the study aims to: 1) give a voice to people living with sequelae; 2) contribute to a greater understanding of the impact on their quality of life; 3) use this understanding to make suggestions for intervention development.

Materials and methods

Design

The current study employed an experiential qualitative design using thematic analysis of one hundred blog posts.

The study takes an experiential orientation that prioritizes meaning as expressed by the blog posters, a critical realist ontology, and contextualist epistemology. In the context of the present study, the researchers see meningitis disease and the various sequelae as objective, tangible, and measurable, but how blog posters perceive and explain their individual experiences is subjective and influenced by the context and society in which they live.

This study and related findings are reported in line with the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) checklist from the EQUATOR Network website (O’Brien et al., Citation2014).

Ethics

Ethical approval was obtained from the Faculty of Health and Life Sciences, University of Northumbria Ethics Committee (Submission Ref: 49435). Although informed consent was not deemed necessary as all data was in the public domain, in line with the British Psychological Society’s guidelines for internet-mediated research, the authors removed all potentially identifiable information before analysis to protect the privacy of blog posters (The British Psychological Society, Citation2021).

Data collection

Terms including “meningitis,” “septicemia,” “sequelae,” and “after-effects” were entered into internet search engines to find relevant blog sites. Inclusion criteria were that the content is publicly available (no membership or password needed to access data).

Five blog sites were chosen. These were from the websites of meningitis charities in sections designed for users to share their stories and experiences. These sites vary in the number of posts, and all were searched starting from the most recent blogs with no date limit for inclusion. One hundred posts were collected across these five blog sites from one-hundred separate users, one blog post per individual user.

All chosen data was uploaded into the software program NVivo for analysis.

Sample

Purposive sampling was employed to choose blog posters from the relevant resources, with irrelevant posts discarded. As rich data is preferable for qualitative research (Clarke & Braun, Citation2013), a blog post was deemed irrelevant if there was insufficient detail related to the research question. Posts reporting a full recovery, focused almost entirely on the acute stage of hospitalization, or those written by family members, were also excluded. Inclusion criteria were a blog poster reporting one or more sequelae after a diagnosis of meningitis, and the post was written first-hand in English.

Blog posters ranged from teenagers to elderly adults, with the majority residing in the UK, USA, Ireland, Australia, and New Zealand.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using Braun and Clarke (Citation2006, 2013, Citation2019, Citation2021) guidelines for their specific form of ‘reflexive’ thematic analysis. A predominantly inductive "bottom-up" approach was carried out on all data items. The first analysis phase involved a period of familiarization with the data, where all data items were read multiple times with general trends across the dataset noted. Next, complete coding was conducted across all data items. These codes were primarily semantic, aiming to prioritize meaning as expressed by the blog posters instead of researcher interpretations (Byrne, Citation2022).

From here, codes were grouped into categories that were whittled down to candidate themes. At this stage, CB and AR discussed the initial coding and their relation to the proposed domains until an initial coding framework was agreed upon. The initial framework was applied to 4 more transcripts, which did not generate new codes, suggesting data saturation had been met. Once all transcripts were analyzed, a thematic framework of barriers and facilitators impacting the behavior was created. This final framework was checked against the entire dataset to ensure it reflected the meaning of the blog posters responses.

Extracts from the data were chosen to represent the final themes; these extracts were treated analytically, with interpretations relating to the specific extracts and the entire dataset. Shorter quotes were sometimes taken from larger original posts; this is signified using […] to indicate data has been removed.

Results

The inductive thematic analysis produced three themes and two sub-themes. Nevertheless, some overlap exists between themes, explained in further detail throughout the analysis. Furthermore, blog posters’ experiences were far from unified or monologue, and contradictions in their experiences’ where present are addressed ().

Figure 1. Thematic map of all themes and sub-themes.

Note. Lines with pointed arrows indicate a directional relationship from theme to sub-themes.

Struggling to adjust to the new normal

Struggling to adjust to the new normal explores blog posters’ perceptions of meningitis and living with after-effects as a life-changing event with negative consequences.

A feeling of loss was prominent throughout the data, including loss of previous abilities, independence, and employment or friends. In addition, memory loss, either to the life they had before the illness or ongoing carrying out daily tasks, was reported as being disorientating, scary, and at times dangerous.

The hospitalization period and the immediate aftermath post-discharge were explained as particularly tough, with many blog posters struggling or unable to return to their old lives, jobs, and education commitments. Overall, this period was described as a time of anxiety, isolation, and grief towards their previous lives. This echoes Bury (Citation1982) description of ‘Illness as a biographical disruption’, with those experiencing chronic conditions and life-threatening events facing challenges to their self-identity. Strauss (Citation1997) describes the phases of dealing with a biographical disruption as starting with shock, bitterness, and confusion that life will not be the same again.

Blog Poster 4/Blogsite 4 - I simply went to sleep before lunch on Sunday and woke up 10 days later in the Hospital’s Intensive Care Unit and life as I knew it, had gone. ‘[…]’ I was now deaf and I had lost the sight in my left eye. ‘[…]’ I wanted the clock to wind back and my life to go back to normal. ‘[…]’ After a lifetime of living in a normal hearing and sight-seeing world this was scary, isolating and very lonely and I was angry and depressed and cried at the drop of a hat. I couldn’t have a conversation with my children or partner, couldn’t hear or see the TV, use a telephone, hear the doorbell or read a book or magazine as the writing was too small. I was desperate to communicate with people again […].

The feeling of longing to return to their life before the illness was commonly shared across the data set. Returning to work or study commitments was one area where blog posters’ desire for normalcy was palpable. In some cases, this was impossible and caused a feeling of despondence and lack of purpose, while for others, the road back to employment or education was one with many challenges.

Blog Poster 3/Blogsite 1 - I was desperate to get back to work and persuaded the doctor to let me try a return to work plan. I […] managed to work 9 hours a week but this caused me extra anxiety, tiredness and headaches. After work, I had to lie down and it took a day or so to recover. […] I thought if I returned to work all the side effects would disappear, as I would be concentrating and putting all my energy into my job. It was difficult returning to work. I felt I had lost all my skills and I felt like a different person. […] I developed extreme anxiety which led to depression. I ignored the symptoms hoping they would all go away, but they didn’t and I went backwards in my recovery.

The drive to keep going, not give up, and get back to normal, in turn, causes more significant problems, leading to a stage of denial and guilt despite the warning signs of declining physical and mental health. Many reports of mental health difficulties and exhaustion during this phase were observed across the data set.

Memory loss was expressed in numerous ways along a broad spectrum of severity among blog posters. At its most extreme, blog posters reported having no recollection of their life before meningitis or not recognizing any family members upon waking from a coma. More frequently, they reported struggling to remember words and finding difficulties in vocabulary and communication compared to their pre-meningitis selves. Episodic and semantic memory was not only reported as being affected, with blog posters equally reporting learning new things and retaining procedural memory as problematic. Memory loss led to many situations of heightened anxiety for blog posters, from emergencies occurring due to forgetting kitchen appliances were on to dilemmas with driving and directions. Incidents of this kind, ranging from disorientating to terrifying, show potential real-world implications of memory loss on both the blog posters and others. While the specific outcomes and difficulties caused by these lapses in memory varied across the blog posters, the persistent nature, emotional reactions, and anxiety they induced were a common trend.

Some variations in experience dependent on the type and severity of sequelae were noticeable in the data. Those experiencing amputations, loss of hearing or vision, and severe neurological difficulties in areas such as memory loss unsurprisingly experienced the most significant life change. Having to relearn how to walk, attend speech therapy, and relearn basic skills, the grief expressed towards their old life in the early stages of recovery was understandably the greatest in this group. On the other hand, those with milder cognitive symptoms were more likely to report exhaustion and embarrassment when facing difficulties returning to their pre-meningitis commitments.

The impact of knowledge and support

This theme comprises two contrasting subthemes. ‘Lack of Awareness Causing Further Suffering’ and ‘Validation Leads to Narrative Shift’ show the empowering and validating impact finding knowledge and support has on those who manage to access it and the disabling and isolating effect on those who do not.

Lack of awareness causing further suffering

Some blog posters had not heard of meningitis or understood the possible symptoms until it nearly ended their life. Others reported medical professionals misdiagnosing them at the crucial stage of onset. Many spoke of feeling unprepared and ill-informed after hospital discharge with no follow-ups, after-care, or advice given. Leaving hospitals feeling they were on the way to being fully recovered and that this was the end of their meningitis journey, only to find this was the beginning of far more challenges. These, at times, are exacerbated by a perceived lack of awareness or sympathy from friends, family members, and institutions such as schools and workplaces.

Blog Poster 26/Blogsite 1 - I told employers I’d had meningococcal meningitis, but they never properly understood the effects, as I barely understood my own myself. I thought I was just incapable, and this caused depression. It never occurred to me that it might be the meningitis until I went back into barista-ing - work I’d done for two years and could do in my sleep - and found I couldn’t remember orders or keep up with the fast paced environment. This eventually lead to a nervous breakdown, as I didn’t feel I had a future if I couldn’t handle the simplest of things.

Here, the blog poster internalizes a narrative of self-blame rather than attributing their struggles to sequelae from meningitis. Throughout the data set there were multiple references to the level of despair this lack of knowledge of the “illness identity” (Leventhal et al., Citation2016) of meningitis and its sequalae caused. Many report depression and hopelessness at key stages of their illness trajectory. Another person who developed meningitis while still at school reports internalizing the doctors lack of knowledge about their illness:

Blog Poster 14/Blogsite 3 - I just kept telling myself that the doctors said I was ‘recovered’ and therefore I should be able to slot straight back in. I recall losing consciousness during one of my GCSE exams. I woke up to blood all over my exam paper, and my teacher apologising to me, saying I had no choice but to carry on. It seemed like I was just in this constant haze of struggle, and no one could reach me.

Blog Poster 24/Blogsite 3 - Those on the outside don’t appreciate the effort it takes to show up on any given day. People’s judgments can be harsh and because I look fine on the outside, people assume I am exaggerating or lying or things aren’t really that bad.

It is important to note that most blog posters expressed positive feelings and extreme gratitude to the medical staff that, in many cases, saved their lives. However, a sizable minority found themselves with issues such as misdiagnoses in the acute stage and, at worst, having medical staff dismiss their concerns as attention-seeking, delaying treatment that sometimes had catastrophic consequences. One blog poster who reported a range of physical, cognitive, and psychological difficulties since contracting meningitis explains the specific emotions this has caused.

Blog Poster 13/Blogsite 3 - Had that GP fobbed me off like the other two, I wouldn’t be here today. Had they acted sooner, would I be left with these life changes? Who knows? It’s hard to think about. I feel I was badly let down.

Blog posters with more severe and noticeable sequelae generally reported greater appreciation for the after-care support and rehabilitation they received. In contrast, those with milder symptoms often tried to access support later in their recovery and were more likely to express the lack of resources health care systems have when dealing with their needs or feeling misunderstood or not taken seriously with their concerns. Blog posters reporting viral meningitis were particularly prone to reporting misconceptions of the severity of their illness, expecting full recovery within days of leaving hospitals and then experiencing prolonged post-viral symptoms.

Validation leads to narrative shift

This sub-theme collates the numerous ways blog posters reported finding knowledge and support helped them understand their symptoms and validated their experiences. Both were described as alleviating psychological stress, self-blame, and isolation, positively improving acceptance, and allowing blog posters to regain control of their lives.

Almost exclusively, this knowledge and support came from charitable organizations. Providing various services, from paying for therapy, posting accessible summaries of research findings, online peer support forums, and the blog sites from which the current study is derived. Blog posters reported accessing these services as a source of comfort and a turning point in their recovery process. In some cases, family members also received help. These services were often reported as filling a gap in perceived support from healthcare providers in the post-acute stage of recovery.

Blog Poster 8/Blogsite 3 - When I left hospital no support was given.

[…] What happens now? I remember coming home and thinking what happens now?

I was signed off work and was told to contact the GP if I needed more support.

Luckily, I found [charity name], and this is where things changed. All the support I needed was there.

[…] I remember getting off the call thinking, "Wow, I’m not alone and there is so much support in this group".

I also then joined the peer support group and shared my story with other meningitis sufferers and people who have been affected by this dreadful illness.

[Charity name] has made me realise you are not alone and whenever you need to chat they are there and will do anything they can to help you.

Taking a proactive approach in finding and engaging with charity services, in this case, led to a feeling of security that their needs would be met. For others, accessing knowledge and support did not happen until later in their recovery; this brought with it a specific juxtaposition in emotions, from feeling relief at understanding more about themselves finally but sadness at the years struggling with the negative impact of lack of awareness of their conditions.

Blog Poster 14/Blogsite 3 - All this time I struggled to understand why I am like this. It is when I contacted [charity name] that it was explained to me that all these problems were caused by my acquired brain injury. I felt a sense of relief to know why, but also a sense of sadness as I have struggled for so long and beaten myself up so much when actually I’m different and need to live differently rather than punish myself for not being who I was.

Here, the blog poster who spoke of their ‘constant haze of struggle’ in the previous theme describes the freeing impact of an illness narrative (Frank, Citation1995) that not only makes sense of their symptoms but also replaces the guilt and self-blame narrative that had negatively impacted their life over many years. Such “narrative turning points” were commonly reported across the data. The following blog poster talks of this impact after struggling with mental health issues such as anxiety and panic attacks since contracting meningitis.

Blog Poster 32/Blogsite 1 - It was after reading this information on [charity name] website that I could finally overcome some of the shame about my self-perceived ‘weaknesses’ and reach out for help. I learnt how to manage my mental health instead of letting it manage me, and really live the life that I had been blessed with.

Here, the blog poster describes finding narrative and practical knowledge as a significant turning point in how they understood and managed their symptoms and life. This positive and empowering impact of information and peer support on blog posters was seen across the dataset. All ages, types of meningitis, and range of sequelae reported these services as essential to their recovery process.

Earlier, we saw blog posters struggling to return to their previous life commitments, leading to feelings of distress, confusion, and isolation. When blog posters lacked an identity for the sequelae and symptoms they were experiencing, they were more likely to adopt a pessimistic explanatory style. Attributing the cause as internal (something about me), timeline as chronic (it will always be with me), and consequences as global (it will undermine everything I do), leading to a perception of lack of control (Peterson, Citation2000).

In contrast, blog posters with an identity for sequelae and symptoms (e.g. ABI), attributing the cause as external (meningitis), generally adopted a far more optimistic explanatory style. While they still faced challenges in returning to their former commitments, they were able to put their recovery first and work towards their goals with the appropriate help. The support of others in the same situation validates their experience, reduces the possibility of self-blame, increases awareness of rights and support available, and gives constant security and a place to turn through the stages of recovery ahead. In addition, these blog posters expressed a far greater level of control over their symptoms.

Navigating possibilities for positivity

Navigating possibilities for positivity explores positivity’s various roles in blog posters’ narratives. Often, this was expressed as growth in the aftermath of illness, though for others, the pressure to perform positivity or inability to do so was a source of further distress.

One of the most prominent themes across blog posters’ accounts was that they feel lucky despite the life-changing hardships they face due to meningitis. This often created a mix of emotions, both grieving for their losses since infection yet feeling grateful to be alive.

Blog Poster 23/Blogsite 3 - Although I spent a long time initially grieving for the version of myself I feared I would never get back after meningitis, I now feel like I have gained more than I have lost. I have more empathy and compassion now than I ever did, I can deal with setbacks and there are lots of issues that I feel very comfortable dealing with now that would have terrified me before I became unwell.

This negative to positive narrative was common across the dataset. It echoes the literature on post-traumatic growth (Tedeschi & Calhoun, Citation1996) that describes how following traumatic life events; people often report positive psychological changes across five domains: a greater appreciation of life, more meaningful relationships, increased strength and resilience, openness to new and often more altruistic life paths, and stronger religious, spiritual, or existential beliefs (Tedeschi et al., Citation2016). All of these were seen to various extents across the dataset.

Blog posters reported giving back to help others in a similar position in various ways, from working for organizations assisting amputees or those in wheelchairs to volunteering for meningitis charities or raising awareness of the condition and after-effects in broader society. These feelings of not letting their struggles be in vain were a significant part of most blog narratives. In the words of the following blog poster: "I want to be able to help. I don’t want to take advantage of waking up every day, I want to make use of every breath I take" (Blog Poster 36/Blogsite 1).

Undertaking physical challenges to raise money for their chosen charities, such as coastal walks, cycles, and half-marathons/marathons, were reported to serve multiple purposes. Simultaneously giving back and raising awareness for the organizations that had supported them, they also represent a significant milestone in their recovery and show others that outstanding achievement is possible despite the added difficulties caused by sequelae: "I run this body. Nothing else does, and certainly not meningitis. And I am the luckiest, most privileged runner, with or without toes, in the entire world. It would be an injustice not to try my hardest" (Blog Poster 4/Blogsite 3).

These findings further confirm the quest narrative identified by Frank (Citation1995), where the storyteller experiences suffering and profound life change but uses this experience to transform their identity to find a new life meaning. This allows those experiencing illness to change their role from passive receivers of care into active storytellers, using their experience to help others and become the hero in their own story.

An equally common trend across the data was gratitude to the various people and organizations that had helped the blog posters throughout their journey:

Blog Poster 3/Blogsite 5 - Lastly, I would like to acknowledge my awesome God for giving me back my life, the incredible doctors and nurses at both Hospitals and the Rehab Centre for the outstanding work they do, my amazing family for sticking beside me through this ‘crazy-amazing’ journey, as I call it, family and friends that have been there for us and the [charity name] for their extraordinary work… I want to make the world a better, brighter place. There is still a long way to go, but I am determined to not let it hold me back.

However, there was a flip side to these positive and growth narratives—some blog posters felt they were expected to conform to them. As a result, a substantial minority of blog posters expressed difficulties in feeling lucky.

Blog Poster 34/Blogsite 3 - I’m very silent when talking about meningitis to my family because I feel if I did talk about it I would just be told to grow up and to carry on thinking that I was lucky to have the outcome I had, and I know that.

Blog Poster 41/Blogsite 3 - I felt so low, but I knew I should be grateful for having survived such a dangerous disease.

This pressure to publicly perform a positive narrative fits with previous cancer research. Ehrenreich (Citation2001) describes her experience with breast cancer engaging with the survivor community as riddled with enforced optimism, to the point that understandable anger or sadness at the negative impact of the disease requires an apologetic tone or be met with a harsh response. Willig (Citation2009) further describes that while dealing with a diagnosis of skin cancer, the opinions of friends and family members at times hindered personal acceptance and well-being, which was also seen in this section of our data set.

Blog posters listing a series of severe sequelae and descriptions of how awful it is to live with them day by day, interspersed with comments that they are one of the lucky ones who survived, were also common across the data, further suggesting mixed emotions, including a desire, and struggle, to maintain a positive spin on profoundly difficult circumstances. For a smaller minority, expressing any positivity about the impact of meningitis and its resulting sequelae on their life was impossible, as seen with the following blog poster.

Blog Poster 4/Blogsite 1 – I’m told full recovery could take two years […] Update: […] People think when you’re discharged from hospital you’re better. Most people haven’t a clue. 3.5 years later I’ve still got ongoing issues. I attend a pain specialist regularly. Meningitis has 100% ruined my health and my quality of life. It’s not just affected me but my partner and family too. It’s a living ongoing nightmare.

Here, we see the blog poster’s experience echoing earlier entries regarding lack of awareness, miscommunication from hospital staff regarding the expected length of recovery, and a feeling of discord between their expectations of what others think recovery should look like and their reality, adding to the difficulties they face.

While post-traumatic growth was a dominant narrative across the data set, this was far from unanimous. Significant individual differences in experience were apparent with some blog posters reporting considerable growth in the months following hospitalization and others experiencing none many years later. These differences suggest a highly individual and nonlinear recovery process. The commonality is that perceived growth occurs when an individual’s focus changes from a narrative of loss to one of gain.

Facilitators identified as contributing to a positive or growth narrative include internal validation through adequate knowledge as to the cause of sequelae symptoms, external validation from the support of others, and blog posters using their experience as inspiration to give back or undertake new pursuits. Conversely, pressure to perform positivity, lack of awareness as to the cause of symptoms, and feeling of incongruence to the opinions of others minimizing the negative impact of sequelae, acted as barriers, prolonging a narrative of chaos.

Discussion

By analysing the content of one-hundred blog posts, the present study explored how sequelae impact the lives of meningitis survivors. Sequelae from meningitis are known as wide-ranging, with significant variations in severity between cases (Marten et al., Citation2019), which the blog posters’ experiences corroborated, with a wide array of life areas impacted to vastly different degrees.

Despite this, common trends in experience were identified, including: 1) Meningitis is a life-changing event with long-term difficulties for those experiencing sequelae; 2) a lack of awareness of certain sequelae’s debilitating, long-term nature permeates society, including some medical professionals, enhancing difficulties; 3) significant differences in experiences were reported between those with visible and non-visible after-effects; 4) charities are the central hub for education on sequelae and psychosocial support in the post-acute stages, benefiting those who access them; 5) post-traumatic growth is a common, but not unanimous, feature in survivors’ meaning-making.

In comparison to previous qualitative studies in the area, despite the difference in focus and sample with Wallace et al. (Citation2007) study on adolescents who have experienced amputations and skin grafts, there are numerous points of crossover with our findings. All themes from the Scanferla et al. (Citation2020) study were replicated in our findings to various degrees. The most notable additions found in our study were in the long-term barrier to acceptance and successful recovery many blog posters felt due to a lack of understanding as to the cause of their symptoms post-hospitalization, and the benefit of peer-support services in counteracting these issues in those who access them.

Similar to our findings, Wallace et al. (Citation2007) saw participants split their lives into pre- and post-meningitis. Scanferla et al. (Citation2020) further identified prolonged physical and psychological after-effects in their sample, suggesting a life-changing event with long-term difficulties. Scanferla et al. (Citation2020) highlighted the potential benefit of systematic medical appointments in the months and years post-discharge, with Wallace et al. (Citation2007) observing that miscommunication between doctors trained in the biomedical model and meningitis survivors over the understanding of what a successful recovery constitutes, is likely to remain. The present study’s findings align with these recommendations, suggesting inconsistencies in after-care.

Scanferla et al. (Citation2020) found a perceived lack of knowledge among family and healthcare professionals; the present study extends these findings to include peers, schools, and workplaces, additionally highlighting the long-term detrimental impact on mental health and self-esteem this caused for many participants. Wallace et al. (Citation2007) further identified a possible cause of incongruence between doctors and patients being medical staff’s training in the biomedical model. This model led to them seeing adolescents who survived meningitis alive and without amputations as fully recovered. In contrast, the adolescents saw their skin grafts as a life-changing injury with psychosocial support needed in the post-acute stage. The present study extends these findings to a range of sequelae, with this incongruence a cause of confusion. Some blog posters blamed themselves for their subsequent cognitive difficulties. Feeling they should be recovered functioned as a barrier to seeking support despite extreme psychological stress.

To the best of the researcher’s knowledge, the difference in psychological experience between those suffering from visible and non-visible sequelae has not previously been highlighted in the context of meningitis. However, the present study’s findings that those with visible difficulties were more likely to perceive others as underestimating their abilities, with the opposite being true for those with invisible difficulties, supports previous findings in brain injuries more broadly (Swift & Wilson, Citation2001).

Scanferla et al. (Citation2021) study highlighted the role of charities in providing knowledge for family members to understand meningitis and sequelae better, which the present study extends to the survivors themselves. To the best of the researcher’s knowledge, the benefits of peer support have not been identified in the context of meningitis survivors. However, the present study’s findings support Kinsella et al. (Citation2020) research on acquired brain injuries, showing participants sharing information in rehabilitation groups with others in a similar position lowered depression and improved acceptance and emotional self-regulation.

The present study corroborates the possibility of post-traumatic growth that has been featured in the findings of all previous qualitative studies on meningitis. Interestingly, in the current study’s context, Tedeschi et al. (Citation2016) also identified mutual support with others who have been through similar circumstances as a powerful facilitator of growth, backed up by our findings of peer support creating the conditions for increased growth and acceptance. In addition, Scanferla et al. (Citation2020) observed participants giving back to charities by raising awareness and helping others through sharing their experiences as a sub-profile of post-traumatic growth, which the blog posters experiences in the present study corroborates.

The experience of pain, changed relationships, growing dependency on others, and the possibility of death all happen prematurely and against the presumed chronological order of aging, forcing a re-evaluation of life and a change in habits (Pranka, Citation2018). These align with the present study’s findings of hospitalization and the period shortly after being particularly detrimental to blog posters’ mental health, followed by a process of growth and acceptance.

Frank (Citation1995) describes the role of storytelling as a response to illness’s disruption to life narratives. Frank explains illness stories as taking three possible formats; the restitution narrative, where illness is seen as a transitory event, where the heroes are medicine and medical staff, with normal life then resumed. Secondly, the chaos narrative where suffering continues with no heroes to save the day or happy ending. Finally, the quest narrative, where following a period of hardship and struggle, the patient becomes the hero in their own story by exhibiting growth and positive change. Western society is identified as desiring quest and restitution narratives, where health and well-being are primarily restored. These stories act as a shield from the anxiety-provoking thought that our lives could experience the chaos narrative of illness at any time, with reports of chaos largely shunned.

In the context of the present study, restitution stories would not meet the inclusion criteria of reporting one or more after-effects, which could help to explain the high number of quest stories and findings of post-traumatic growth. In addition, the experience of some blog posters feeling pressure to find growth publicly in a difficult situation and experiencing negative reactions to their experiences of prolonged suffering and chaos also fits into these societal preferences for positive illness narratives.

The happiness imperative experienced by those experiencing ill health can be seen as part of a wider culture of toxic positivity. Goodman (Citation2022) explains toxic positivity as permeating all aspects of western society, but with nobody impacted more than those experiencing disability or chronic health conditions.

To the best of the researcher’s knowledge, pressure to publicly perform a positive narrative has not previously been identified in the context of meningitis survivors. However, Scanferla et al. (Citation2020) identified an incongruence with others as to the severity of their symptoms as a cause of isolation. These findings align with previous research into the personal experience of cancer survivors. Willig (Citation2011) describes cancer diagnosis as placing those diagnosed at odds with broader society, where existential questions and conversations around confronting the possibility of death are actively discouraged. Vitry (Citation2010) further highlights the contrast between a biomedical procedure that sees depression in those experiencing cancer diagnosis as requiring quick solutions and pharmaceutical treatment, with the personal experience of cancer survivors that often lends itself to existential discourse, seeing a period of mourning as essential to achieving acceptance and growth.

Self-regulatory models of illness perception could help to explain further variations in the blog posters’ experiences, with Leventhal et al. (Citation2016) illustrating five specific components that influence how a person perceives and manages a health threat: Identity (a name for disease or symptoms), cause (e.g. infection, stress, smoking), timeline (acute, chronic, or cyclical), consequences (e.g. physical, psychological, economic), control (curability or manageability).

The positive function of optimism in self-regulation of illness threats was highlighted by Rasmussen et al. (Citation2006), with people confident about their future more likely to continue making an effort towards goals, while those doubtful are more likely to experience denial, withdrawal, and increased stress. Their report further explained that health threats negatively impact well-being by making previous life goals unattainable, thus increasing symptoms of depression.

In contrast, pessimistic explanatory styles can lead to increased health-damaging behavior and adverse health outcomes, low self-esteem, and feeling destined to fail (Contrada & Coups, Citation2012; Peterson, Citation2000). However, these adverse effects can be countered through goal readjustment, where unattainable goals are disengaged and replaced with new, attainable ones (Rasmussen et al., Citation2006). The present study’s findings corroborate, with blog posters particularly likely to report mental distress when encountering difficulties returning to their pre-meningitis commitments after hospitalization. However, blog posters reported increased purpose and well-being when finding new and meaningful pursuits. Reduced stress was also observed when using a structured approach to disengage from goals temporarily in recovery, to be re-engaged later.

Clinical implications

The current NICE guidelines in the UK suggest that parents of under 16’s contracting bacterial meningitis or septicemia should have potential after-effects discussed and be given details of charity support and where it can be found (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE], 2010). The present study suggests this be extended to survivors of all forms of meningitis and all age groups.

A potential solution to mitigate some of the problems faced by many blog posters with inconsistencies reported in their after-care could be an initial telephone consultation shortly after discharge with a clinician of biopsychosocial training. This would be particularly suitable to try and reduce the possibility of missed psychological difficulties. With the present study identifying this period and returning to life commitments as particularly challenging with many participants experiencing mental health difficulties, identifying, and signposting those at risk at this stage could have great benefits.

As most meningitis survivors don’t experience long-term sequelae, further consultations should be optional, with those deeming them unnecessary having the information of organizations to contact later if needed. However, for those who opt-in, additional telephone appointments at 3, 6, and 12 months could help to identify patients struggling in this critical transition period.

For those flagged as needing further support, assessment using an adapted Revised IPQ-R (Moss-Morris et al., Citation2002) for symptoms of meningitis sequelae could be used to identify individual patient beliefs and specific areas of concern. From these personal findings, clinicians can fill gaps in patient knowledge and challenge unrealistic assumptions. Clinicians could also contact education establishments or employers to arrange structured return plans where necessary. For those experiencing previous life goals becoming unattainable, using hierarchical goal plans to create patient-led plans for goal readjustment to new, attainable goals could be beneficial (Rasmussen et al., Citation2006). These are all designed to be dynamic and open to change at different stages of patient recovery.

Further research into whether the IPQR (Moss-Morris et al., Citation2002) can be successfully adapted for meningitis after-effects while retaining reliability and validity is necessary, as well as evaluations into the widespread applicability, financial feasibility, and improvement in patient well-being after such interventions.

Strengths and limitations

Many of the study’s strengths come from the larger sample size than previous qualitative studies in the area, allowing a broader range of stories to be analyzed, with new observations and contradictions in blog posters’ experiences being identified. In addition, linking the findings to established health psychology models of self-regulation in illness perception helps to understand some probable causes of these variations. Finally, the study suggests potential improvement in after-care and exciting areas for future research.

The study is far from without limitations. First, the retrospective nature of blog posts could induce storytelling bias. Second, blogs from charity websites likely overestimate these organizations’ impact on meningitis survivors more broadly. However, this does not negate the benefits reported and the possibility that others could gain from these services. Finally, the self-selecting nature of blog posters who upload their stories to a charity website could attract a certain kind of blog poster.

The vast majority of blog posters are from higher-income Western countries, so it is highly likely that their healthcare experiences are not representative of meningitis survivors worldwide. Even among the nations represented, healthcare systems are varied, which could induce further bias. The U.S.A. notably does not have a national healthcare service, which could make accessing certain rehabilitation facilities more difficult for these blog posters.

As previously discussed, western society’s desire for restitution and quest narratives likely influenced the type of stories survivors share, with the possibility that those experiencing prolonged suffering and chaos are less likely to contribute. This comparatively small and self-selecting sample requires further research on the study’s findings to assess their widespread applicability and validity.

In addition, with numerous demographic information removed before analysis, trends specific to certain genders, age groups, years since onset, or country of residence were impossible. Future research repeating the study for particular demographics, types of meningitis (bacterial/viral), or years since onset (< 5) could help close these gaps and make findings potentially more relevant to present-day healthcare systems.

Finally, inclusion criteria that blogs were written first-hand in English are likely to have attracted a specific type of blog poster, with those with more severe neurological disabilities unable to post, or those unable to speak English or afford a computer or smartphone device also excluded from the conversation. But, again, further research in different cultural contexts, or interviews with survivors’ family members, could help close these gaps.

Conclusion

While vaccine rollout has dramatically reduced the number of new infections, those living with meningitis after-effects face a range of long-term challenges that will continue for many years. The present study detailed a small, explorative investigation into the psychological impact of meningitis sequelae. It highlighted common trends in experience across three themes and two sub-themes.

The results led to recommendations for improvement in after-care and possible intervention strategies. Still, limitations, including the comparatively small and self-selecting sample, make further research to assess the validity and widespread applicability of these findings necessary.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the associate editor and anonymous reviewer for their constructive comments on an earlier version of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Open Science Framework at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/MK9UW.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 328–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

- Bury, M. (1982). Chronic illness as biographical disruption. Sociology of Health & Illness, 4(2), 167–182. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.ep11339939

- Byrne, D. (2022). A worked example of Braun and Clarke’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Quality & Quantity, 56(3), 1391–1412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-021-01182-y

- Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. Sage.

- Contrada, R. J., & Coups, E. J. (2012). Personality and self-regulation in health and disease: Toward an integrative perspective. In The self-regulation of health and illness behaviour (pp. 67–95). Routledge.

- Ehrenreich, B. (2001). Welcome to cancerland. Harper’s Magazine, 303(1818), 43–53.

- Frank, A. W. (1995). The wounded storyteller: body, illness, and ethics. The University of Chicago. Press.

- Goodman, W. (2022). Toxic positivity: How to embrace every emotion in a happy-obsessed world. Hachette UK.

- Greenwood, B., Sow, S., & Preziosi, M. P. (2021). Defeating meningitis by 2030-an ambitious target. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 115(10), 1099–1101. https://doi.org/10.1093/trstmh/trab133

- Kinsella, E. L., Muldoon, O. T., Fortune, D. G., & Haslam, C. (2020). Collective influences on individual functioning: Multiple group memberships, self-regulation, and depression after acquired brain injury. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 30(6), 1059–1073. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2018.1546194

- Leventhal, H., Phillips, L. A., & Burns, E. (2016). The common-sense model of self-regulation (CSM): A dynamic framework for understanding illness self-management. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 39(6), 935–946. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-016-9782-2

- Marten, O., Koerber, F., Bloom, D., Bullinger, M., Buysse, C., Christensen, H., De Wals, P., Dohna-Schwake, C., Henneke, P., Kirchner, M., Knuf, M., Lawrenz, B., Monteiro, A. L., Sevilla, J. P., Van De Velde, N., Welte, R., Wright, C., & Greiner, W. (2019). A DELPHI study on aspects of study design to overcome knowledge gaps on the burden of disease caused by serogroup B invasive meningococcal disease. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 17(1), 87. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-019-1159-0

- Martinón-Torres, F., Taha, M. K., Knuf, M., Abbing-Karahagopian, V., Pellegrini, M., Bekkat-Berkani, R., & Abitbol, V. (2022). Evolving strategies for meningococcal vaccination in Europe: Overview and key determinants for current and future considerations. Pathogens and Global Health, 116(2), 85–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/20477724.2021.1972663

- Moss-Morris, R., Weinman, J., Petrie, K., Horne, R., Cameron, L., & Buick, D. (2002). The revised Illness Perception Questionnaire (IPQ-R). Psychology & Health, 17(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870440290001494

- Nadel, S., & Ninis, N. (2018). Invasive meningococcal disease in the vaccine era. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 6(vember), 321. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2018.00321

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE]. (2010). Meningitis (bacterial) and meningococcal septicaemia in under 16s: recognition, diagnosis and management Clinical guideline [CG102]. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg102, June 2010, 1–47.

- O’Brien, B. C., Harris, I. B., Beckman, T. J., Reed, D. A., & Cook, D. A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 89(9), 1245–1251. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388

- Olbrich, K. J., Müller, D., Schumacher, S., Beck, E., Meszaros, K., & Koerber, F. (2018). Systematic review of invasive meningococcal disease: Sequelae and quality of life impact on patients and their caregivers. Infectious Diseases and Therapy, 7(4), 421–438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-018-0213-2

- Peterson, C. (2000). The future of optimism. The American Psychologist, 55(1), 44–55. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.44

- Pranka, M. (2018). Biographical disruption and factors facilitating overcoming it. SHS Web of Conferences, 51, 03007. https://doi.org/10.1051/shsconf/20185103007

- Rasmussen, H. N., Wrosch, C., Scheier, M. F., & Carver, C. S. (2006). Self-regulation processes and health: The importance of optimism and goal adjustment. Journal of Personality, 74(6), 1721–1747. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2006.00426.x

- Scanferla, E., Fasse, L., & Gorwood, P. (2020). Subjective experience of meningitis survivors: A transversal qualitative study using interpretative phenomenological analysis. BMJ Open, 10(8), e037168. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037168

- Scanferla, E., Gorwood, P., & Fasse, L. (2021). Familial experience of acute bacterial meningitis in children: A transversal qualitative study using interpretative phenomenological analysis. BMJ Open, 11(7), e047465. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-047465

- Schiess, N., Groce, N. E., & Dua, T. (2021). The impact and burden of neurological sequelae following bacterial meningitis: A narrative review. Microorganisms, 9(5), 900. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9050900

- Strauss, A. L. (1997). Mirrors and masks: The search for identity. Transaction Publishers.

- Sumpter, R., Brunklaus, A., McWilliam, R., & Dorris, L. (2011). Health-related quality-of-life and behavioural outcome in survivors of childhood meningitis. Brain Injury, 25(13–14), 1288–1295. https://doi.org/10.3109/02699052.2011.613090

- Svendsen, M. B., Ring Kofoed, I., Nielsen, H., Schønheyder, H. C., & Bodilsen, J. (2020). Neurological sequelae remain frequent after bacterial meningitis in children. Acta Paediatrica (Oslo, Norway: 1992), 109(2), 361–367. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.14942

- Swift, T. L., & Wilson, S. L. (2001). Misconceptions about brain injury among the general public and non-expert health professionals: An exploratory study. Brain Injury, 15(2), 149–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699050117322

- Taha, M. K., Martinon-Torres, F., Köllges, R., Bonanni, P., Safadi, M. A. P., Booy, R., Smith, V., Garcia, S., Bekkat-Berkani, R., & Abitbol, V. (2022). Equity in vaccination policies to overcome social deprivation as a risk factor for invasive meningococcal disease. Expert Review of Vaccines, 21(5), 659–674. https://doi.org/10.1080/14760584.2022.2052048

- Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (1996). The posttraumatic growth inventory. Jounal of Traumatic Stress, 9(3), 455–471.

- Tedeschi, R. G., Calhoun, L. G., Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (2016). Target article: Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Posttraumatic Growth : Conceptual Foundations and Empirical Evidence, 7965(March), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli1501

- The British Psychological Society. (2021). Ethics guidelines for internet-mediated research. https://explore.bps.org.uk/content/report-guideline/bpsrep.2021.rep155

- Viner, R. M., Booy, R., Johnson, H., Edmunds, W. J., Hudson, L., Bedford, H., Kaczmarski, E., Rajput, K., Ramsay, M., & Christie, D. (2012). Outcomes of invasive meningococcal serogroup B disease in children and adolescents (MOSAIC): A case-control study. The Lancet. Neurology, 11(9), 774–783. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70180-1

- Vitry, A. (2010). The imperative of happiness for women living with breast cancer. Canadian Woman Studies/Les Cahiers de la Femme, 28, 30–33.

- Wallace, M., Harcourt, D., & Rumsey, N. (2007). Adjustment to appearance changes resulting from meningococcal septicaemia during adolescence: A qualitative study. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 10(2), 125–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/13638490701217313

- Wang, B., Santoreneos, R., Afzali, H., Giles, L., & Marshall, H. (2018). Costs of invasive meningococcal disease: a global systematic review. PharmacoEconomics, 36(10), 1201–1222. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-018-0679-5

- Willig, C. (2009). Unlike a rock, a tree, a horse or an angel…’ reflections on the struggle for meaning through writing during the process of cancer diagnosis. Journal of Health Psychology, 14(2), 181–189. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105308100202

- Willig, C. (2011). Cancer diagnosis as discursive capture: Phenomenological repercussions of being positioned within dominant constructions of cancer. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 73(6), 897–903. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.02.028

- Wilson, E., Kenny, A., & Dickson-Swift, V. (2015). Using blogs as a qualitative health research tool: a scoping review. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 14(5), 160940691561804. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406915618049