Abstract

Differentiated instruction occurs when teachers use students’ level of readiness, interests, and learning preferences to adjust the content, process, or products, which increases engagement and academic performance. However, teachers cannot offer every form of differentiation to every student all the time. There exist limits of resources as well as an essential balance that teachers need to make in terms of benefits for student learning on the one hand and classroom efficiency on the other. Additionally, the choices teachers make in terms of differentiation are also rooted in and stem from their personal beliefs systems. The goal of this research was to investigate teachers’ preferences for differentiating their instruction by using Q methodology. 32 teachers, coming from a single Dutch secondary school, completed a paper version of a Q sort containing 33 statements. Three groups of teachers were identified who emphasized 1) content mastery over students’ interests, 2) offering options over content growth, and 3) students’ interests or experiences over deliberate teaching. Therefore investigating teacher’s personal differentiation preferences will offer insight into what teachers choose to focus on in their differentiation, as well as, what teachers to not to emphasize. Each cluster is explored in terms of possible effects on student learning. Additionally, the implications for teacher development are also discussed per cluster.

Introduction

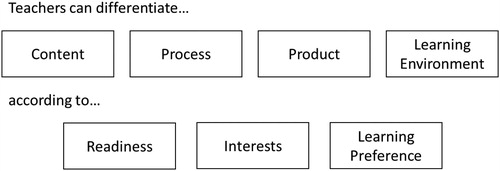

The notion of differentiated instruction is built upon the idea that teachers should focus on differences in terms of individual student’s level of readiness, interests, and learning preferences (Tomlinson, Citation1999). Readiness is defined as students’ earlier experiences, views about school and proficiency level in terms of cognitive and metacognitive skills (Santangelo & Tomlinson, Citation2012). By focusing on individual student’s interests, teachers can increase student engagement (Reis & Renzulli, Citation2010) and thus enhance academic performance (Astin, Citation1984; Tinto, Citation1988). Students’ individual learning preferences, such as group activities, lectures, as well as, issues concerning the actual physical learning environment (lighting, noise, etc.) are also important factors in student learning (Tomlinson et al., Citation2003). These three essential issues need to form the foundation for teachers’ decisions on how and when to differentiate in terms of: the “content” of the learning activity (what is being taught), the “process” of learning (how it is being learned), “products” that need to be created (assessments such as tests, reports, etc.), and the routines, procedures “as well as the overall tone or mood (Santangelo & Tomlinson, Citation2012, p. 314)” of the learning environment.

However, the work of Tomlinson needs to be seen as a part of the academic literature on differentiation and can be situated within a larger differentiated discussion. For example, McTighe and O’Connor (Citation2005) assert that there are seven practices for effective learning ranging from the usage of summative testing, assessing prior to the commencement of teaching, and goal setting for students. These practices are not contained in Tomlinson’s model.

In terms of content, when teachers adapt their content to students’ interests, students can perceive the relevance of the material and thus, teachers increase the chance for students to engage in that material or educational activity (Assor et al., Citation2002). Duball and Baker (Citation1990) when investigating student attrition, found that students who dropped out, compared to students who persisted in their degree program, reported lower levels for appropriateness of the instructional methods chosen by teachers. Besides the appropriateness of instructional methods, students need to receive assignments and assessments that both allow and encourage engagement. Gibbs (Citation2010) asserts that many commonly used assignment and assessment forms such as reflection assignments and automated multiple choice assessments fail to engage students and can lead to low quality student learning. Additionally, how students perceive the learning environment has also been identified as having a role in students’ sense of belonging in the classroom, which is also a factor in study success (Meeuwisse et al., Citation2010).

The academic literature concerning student engagement demonstrates the positive effects of student engagement for academic success (Astin, Citation1984; Carini et al., Citation2006; Tinto, Citation1988; You & Sharkey, Citation2009); greater sense of being part of the classroom discourse (Reid & Solomonides, Citation2007), more likely to employ a deep approach to their learning (Horstmanshof & Zimitat, Citation2007; Jansen & Bruinsma, Citation2005), more successful in their later years of study (Severiens & Schmidt, Citation2009), and reducing underachievement, especially in gifted students (Landis & Reschly, Citation2013).

Despite the above benefits, teachers still struggle with differentiating their curriculum (De Neve et al., Citation2015; Smit & Humpert, Citation2012; Tomlinson et al., Citation2003). This is, in part, due to several factors: the tension between meeting student’s individual needs and reaching mandated state standards (Van Tassel-Baska, Citation2006), lack understanding of how meta-cognition can assist in differentiation (Evans & Waring, Citation2008), potential misunderstandings concerning the elemental foundations of a supportive (motivating) classroom interactions (Nichols & Zhang, Citation2011), as well as, insufficient professional development concerning differentiation (Dixon et al., Citation2014).

Teachers’ preferences of teaching

Teachers’ expectations and beliefs about learners and the classroom situation inform their teaching. The seminal work of Rosenthal and Jacobson (Citation1968) exploring the Pygmalion effect, laid the foundation for this vast research tradition exploring how teachers’ expectations affect student learning. This research has demonstrated that teachers’ expectations are a powerful force in the classroom. Besides expectations and beliefs, teachers’ self perceptions also influence their pedagogical choices in the classroom. Yeung et al. (Citation2014) report that aspects such as teachers’ self-concept, sense of efficacy, value of learning, and expectations of students in term of level, all influence teachers’ pedagogical actions. Furthermore, teachers’ beliefs systems are based not always based upon academic empirical evidence, but stem from personal opinions and conjecture (McLeod, Citation1995).

In other words, teaching preferences are created by the manner in which teachers’ personally conceptualize their teaching. It forms the core of their beliefs systems and thus at the heart of their teaching practices. Ho et al. (Citation2001) have identified that changes in the way teachers frame and conceptualize their teaching is an essential element of an effective professional development program aimed at improving student learning.

The relevance of teachers’ expectations and beliefs is not solely derived from its effect on students learning, but also due to its origins in teachers’ personal beliefs systems. The components of teachers’ beliefs systems about teaching are founded in their personal experiences as both students and professionals (Kagan, Citation1992). Therefore, teachers’ pedagogical choices could be more due to a predilection to being taught in a certain manner and employing specific known teaching techniques rather than teachers specifically responding to students’ needs or preferences (Aitken & Mildon, Citation1991). Therefore, teachers’ personal preferences inform teaching practices but can also overshadow the needs and preferences of individual students.

Research has demonstrated that the manner in which teachers approach their teaching can directly influences how students study (e.g. deep or superficial approach) (Entwistle & McCune, Citation2004; Kember & Gow, Citation1994; Trigwell & Prosser, Citation2004). Richardson (Citation2005) reviewed 25 years of research tracing the evolution of students’ approaches to studying and teachers’ approaches to teaching. He concluded that the manner in which students approach their studies is based upon two elements: students’ conceptions of learning and perceptions of the academic context. Both of these elements can be greatly influenced by teachers’ personal and pedagogical choices. For example, Trigwell & Prosser, when developing the approaches to teaching inventory (2004), identified two types of approaches to teaching: Conceptual Change/Student-focused and Information Transmission/Teacher-focused approach. Information Transmission/Teacher-focused approach was associated with higher scores on surface learning. This means that not only do teachers control the activities and content that students are required to engage in, but can also directly shape the approach in which students set out to engage in those activities and content.

Teachers’ conceptions of differentiation

Teachers’ conceptions of offering differentiation seems to contain an inherit opposition concerning the notion of individuality and equality (Norwich, Citation1994). Teachers need to choose between offering specific learning opportunities to individual students, as opposed to equalized learning opportunities to all students. This tension can be found in everyday pedagogical choices in the classroom, such as grouping on ability, heterogeneous grouping or offering additional classroom work. If a teacher chooses to group differing ability students together, in order to allow the higher ability students to help lower ability students, this could be an attempt to thwart the higher ability students from advancing too far ahead from the group; thus not having to deal with divergent ability levels in a single classroom. This pedagogical choice clearly leans toward achieving equality among students. On the other hand, if a teacher chooses to offer students additional work to students who are already master the material, then that teacher chooses the needs of those students over the rest of the group. This may risk widening the gap between those students and the other students in the classroom.

Nichols and Zhang (Citation2011) assert that there is also a misapprehension, on the part of teachers, concerning the factors that create a supportive learning environment. This study reports variations in teacher’s desires between teacher empowerment versus student empowerment in the classroom. Additionally, teachers also varied in their desire to encourage a positive classroom environment as opposed to a classroom atmosphere of rejection. Additionally, Hertberg-Davis (Citation2009) notes a prevalence of misunderstandings by teachers concerning how to actually differentiate. Besides the misunderstanding as to how to differentiate, there also exist misunderstandings concerning why to differentiate. Brighton et al. (Citation2005), note one of these misunderstandings as teachers’ preferences to offer differentiation to struggling students as opposed to gifted students. This might also be related to the abovementioned tension between individual instruction and state standards (Van Tassel-Baska, Citation2006) wherein teachers feel the pressure to offer lower ability students a more individualized curriculum in order to help these students reach the state mandated minimum requirements.

Tensions among differentiation, efficiency, and benefits

Schmoker (Citation2010) paints a picture of classroom differentiation as a devolution of classroom practices that “dumbed down” instruction and lead to teacher frustration. He states “differentiated instruction…corrupted both curriculum and effective instruction. With so many groups to teach, instructors found it almost impossible to provide sustained, properly executed lessons for every child or group-and in a single class period” (2010). There is some hyperbole in his assertions, but at its core, Schmoker makes a salient point: there exists a tension between the individual student requirements and the “demand” to meet them as dictated by differentiated instruction enthusiasts. Overuse and infidelity to the model’s principles leading to aberrations in classroom differentiation do exist (Tomlinson, Citation2010). However, Tomlinson also attributes these aberrations to an incorrect application of the model due to a lack of understanding rather than differentiated instruction itself.

Marshall (Citation2016) raises the concern that “overemphasizing, overthinking, and overusing differentiation” (2016, p. 9) can lead to exhausted teachers. Equally, teachers cannot fully and continually differentiate. There are resource limitations in terms of time and money. These limitations are combined together in the classroom with the tensions of choices in classroom practices. These tensions are partially outlined above (Norwich, Citation1994) with the simple fact that teachers simply cannot do everything. Teachers, like any other professional, need to make choices in their practices.

It is this context that the current study aims to extract the teacher’s preferences toward differentiation by investigating those choices. Teachers will choose what they deem to be most beneficial for student learning. While a teacher may value a certain differentiated instructional technique, they may choose to employ a different one in certain situations. However, these choices or preferences might be due more to a personal predilection to being taught in a certain manner or employing specific known teaching techniques rather than specific students’ needs (Aitken & Mildon, Citation1991).

By employing Q methodology, participants are “forced” to choose between alterative options (just like in the classroom). By forcing teachers to choose, Q methodology offers a different perspective in terms of indicated preferences. This methodology also allows for unique combinations of preferences, as opposed to a typical questionnaire with a predetermined factor structure (Godor, Citation2016).

Research goal and purpose

The main goal of this research was to investigate teachers’ personal preferences for differentiating their instruction. This research explores teachers’ subjective points of view concerning instructional differentiation. In order to achieve this goal, Q Methodology was employed in this study. As McKeown and Thomas state (2013): “the primary purpose for undertaking a Q study is to discern people’s perceptions of their world from the vantage point of self-reference (p. 1).” Additionally, a Q Methodology study allows for the identification clusters of subjectivity within the research participants. This means that specific groups of teachers holding the same subjective preferences can be identified.

Research question

In which ways do teaching preferences and beliefs of differentiation effect teachers’ conceptions of their own classroom differentiation practices.

Research method

Participants (P-Set)

Teachers (n = 32) from a single Dutch secondary school, completed a paper version of a Q sort containing 33 statements. The average age was 46 (SD = 10.1) and participants had on average, more than 20 years of teaching experience (M = 22.1, SD = 8.3). Students’ ages in Dutch secondary school range from 12 to 18 years. This school is situated in a rural area and most students are following an agricultural focused program. Teachers in this study specifically taught: Humanities (n = 5) such as languages, natural sciences and Mathematics (n = 16) such as algebra and geometry, physics, chemistry, and Social Sciences (n = 12) such as economy, management, history, and religion.

Q methodology

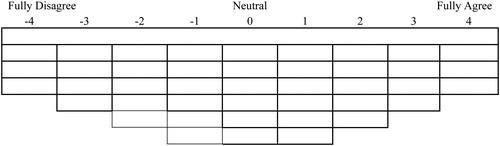

Q Methodology was used as both a research method and an analytical technique for this study to explore subjectivity (McKeown & Thomas, Citation2013; Stephenson, Citation1953). Q Methodology, as outlined by Stephenson (Citation1935), aims at exploring “correlating persons instead of tests (1935, p. 17).” Stephenson strove to explore similar held beliefs within populations by performing factor analysis techniques on subjects instead of test answers. This technique affords researchers a chance to cluster groups of similar subjectivities within a sample. He also desired to create a technique where grouping of subjectivity could be executed in a small sample of participants. A present day example of this is approach in education is looking at students’ approaches to studying within one class (Godor, Citation2016). In this research, Godor examined the approaches to studying for 65 master students following the same course. This is in line with Stephenson’s (Citation1935) previous ideas when introducing Q Methodology. He states: “Whereas previously a large number of people were given a small number of tests, now we give a small number of people a large number of tests or test-items, or require a large number of responses from them. (1935, p. 17)” By administering a fairly large battery of tests, Godor was able to cluster students based on those answer instead of quantifying certain levels of “approaches to studying” in that population. Also a unique aspect to Q Methodology is its data gathering technique. This is a two-step process whereby the development of the statements for participants (Q-Set) is a distinctive collection of commonly held beliefs about the research topic. However, the composition of these statements needs to be balanced in terms of covering all perspectives. This allows participants to proceed to the data collection stage where participants need to sort (Q-Sort, see ) the Q-Set. This technique allows participants to rank all the statements as they see fit and allows both relative soring in terms of agreement as well as the possibility of unique combinations. For example, Lundberg (Citation2019) explored teachers’ viewpoints about an educational reform and reported six unique different viewpoints (subjectivities) in the sample. Stemming from this investigation, Lundberg was able to make specific teacher professionalization recommendations. Subjectivities have been researched surrounding topics such as: prioritizing health care resources (van Exel et al., Citation2015), implications of divorce on children’s emotional and behavioral well-being (Øverland et al., Citation2013), experiences of TIA [transient ischemic attack] (Spurgeon et al., Citation2012) and human resource development (Bartlett & DeWeese, Citation2015).

Q-Set (concourse) development

A Q-set was constructed by a collecting self-referable statements about something, of statistical dimensions (Stephenson, Citation1993, p. 5). Stephenson (Citation1953) also calls for a balanced collection of statements (concourse) to form the Q-Set. The Q set was an adaptation of a survey instrument based on Tomlinson’s comprehensive model of differentiated instruction (Santangelo & Tomlinson, Citation2012). The modified version consisted of 33 statements: 3 on assessment, 9 on content, 4 on interest, 2 on learning environment, 2 on learning profile, 9 on process/product, and 4 on student readiness. The original instrument used in Santangelo & Tomlinson contained 57 items. A selection of statements was chosen that was a balance of statements (Stephenson, Citation1953) and reflective of the current concourse surrounding this topic. These statements were translated to Dutch and then back-translated into English.

Q-Sort

Participants received a paper version which contained both the 33 statements (Q-Set) and a forced distribution Q-Sort (see ). The research question was included at the top of the instruction paper along with the consent statement. Participants were then instructed to first read all of 33 statements in the Q-Set. Participants were then instructed to sort these statements into three categories: disagree, neutral, and agree. This stage is called the presort. For the main sorting procedure, participants filled in the Q-Sort with the corresponding statement number using the presorting categories as a rough guide.

Method

Factor extraction

The dataset was analyzed using the statistical package “R” with the qmethod package (V1.3.1) created by Zabala (Citation2014). A factor analysis using an oblique rotation (oblimin) revealed a parsimonious three factor solution. The total variance explained was 50.49% with 26 of the 32 respondents (81%) loading significantly on one of the three factors. Factors in Q Methodology represent a cluster of participants and not individual items. This solution revealed 21 statements that were significantly distinguishing for one factor, 6 statements that were significantly distinguishing for all factors, 5 consensus statements and 1 statement that was neither significantly distinguishing nor a consensus statement ().

Table 1. Number of participants and eigenvalues per factor.

Factor arrays

In order to interpret the three factors, an idealized Q-Sort was constructed for each of the three factors. This is accomplished by calculated standardized factor score (z-score) per question per factor. These scores are based upon the individual participant’s statement score weighted by their factor loading on that factor. This procedure differentiates the strength of individual participant’s scores when calculating the ranking order of statements for that factor. Accordingly, the statement with the highest z-score for a factor would be assigned a “+4” and remaining statements’ factor scores were subsequently labeled. This idealized Q-Sort ranking is used to sequentially return all statements into the Q-sort’s quasi-normal distribution framework. Additionally, statements’ factor scores were also tested for significant (p < .01) differences. Questions exceeding this limit were labeled as “distinguishing statements” for that factor ().

Table 2. Statements and factor positions.

Results

Three factors or groups of teachers were identified in this study: factor #1: Competency Focused- Interest Adverse, factor #2: Operationally Focused – Mastery Adverse, factor #3: Experience Focused – Pedagogically Adverse. Each of these groups reported significantly different preferences. Included in each of these factors is an emphasis on certain differentiated instructional elements. In the following paragraphs, each factor will be specifically discussed. The term “focused” in this study represents the notion of preference and the term “adverse” represents a lack of preference. This does not mean that teachers are against this concept, but in their choices, a preference or focus is indicated toward one concept and statistically less focus toward the other. In other words, teachers indicate that they would choose one focus over the other in their classroom practices.

Factor #1: competency focused – interest adverse

Teachers in this factor (n = 11) are aware of the differences in competency levels of their students. While the statements concerning students’ competency levels were not significantly distinguishing from other factors, their selection in the first two positive places in their sorts indicates an awareness of this issue. However, the disregard for students’ interest in informing their differentiation strongly characterizes this factor. Negative distinguishing statements (p < .01) such as “My understanding of variance in individual Students’ interests impacts what/how I teach,” “Assess each candidate’s interests (e.g., future plans, areas of talent/passion),” and “Create activities/assignments that allow each candidate to select a topic of personal interest” all indicate that these teachers take students’ interests much less into consideration when compared to teachers in the other two factors. Additionally, these teachers offer fewer options in terms of forms of assessments than teachers in the two other factors ().

Table 3. Distinguishing statements factor 1.

Teachers in the factor seem to compensate for the fact that students differ in terms of academic and study skills by focusing on the process of teaching. A strong emphasis is on grouping techniques, learning modalities, and motivation. However, these teachers’ report that individual interests of students is taken less into consideration in informing their teaching choices. In other words, there is a strong emphasis on the process of teaching and less attention to the products of learning. This can also demonstrated by a lack of variation in assessments forms reported by these teachers.

Factor #2: Operationally focused – mastery adverse

The differentiation that teachers in this factor (n = 8) report is a variety of forms of assessments and a blend of differentiation processes: “Use three or more forms of assessment to determine course grades” and “Use a variety of grouping formats during class. Teachers in this factor also report an awareness of students’ individual learning preferences: “Students in my class differ significantly in their preferred learning modalities.” All three of these statements are positive distinguishing statements (p < .01). These teachers also have a higher average score for enhancing student motivation toward course content compared to teachers in the other two factors. However, these teachers’ differentiation lacks any accessibility to more complex work. This is demonstrated by the significantly distinguishing (p < .01) negative statements: “Create more advanced opportunities for Students who master course content with minimal effort, use text materials that present content at varying levels of complexity, and allow Students to select from multiple text options (e.g., read one of three).”

Teachers in this factor report being focused on the act of teaching. These teachers are also aware of different modalities of learning (visual, auditory, or kinesthetic; active or passive; intelligence preferences). However, there appears to be a lack of focus concerning content differentiation. Students who already master the content are not offered differentiation in terms of advanced content. This differentiation preference could specifically have a negative effect on gifted students in these classrooms. As previously mentioned in Brighton et al. (Citation2005), this avoidance may be due to a stronger focus on weaker students. However, the lack of focus on mastery in this factor could lead to higher levels of underachievement in gifted students and strongly reflects a misunderstanding of why to differentiate ().

Table 4. Distinguishing statements factor 2.

Factor #3: Experience focused – pedagogically adverse

Teachers in this factor (n = 7) are keenly aware of the need to connect the curriculum to the students’ life-world: “Students in my class differ significantly in relevant background knowledge” is a distinguishing positive statement. These teachers also have a higher average score for “Present course content using examples that reflect Students’ interests or experiences” compared to teachers in the other two factors. However, there appears to be a lack of concern for students’ individual learning modalities “Students in my class differ significantly in their preferred learning modalities (e.g., visual, auditory, or kinesthetic; active or passive; intelligence preferences)” as well as general awareness of the importance of the learning environment: “take deliberate efforts to ensure Students participate consistently and equitably during class, take deliberate efforts to make yourself approachable/available to Students.” Moreover, the lack of “deliberate efforts” in especially making oneself “approachable/available” give the impression of disinterest in the pedagogical process ().

Table 5. Distinguishing statements factor 3.

The interest and background experience of student is the focus of teachers in this factor and informs how these teachers differentiate. They present content using examples based on students’ experiences. However, deliberate teaching seems to be less of a focus. These teachers use differentiated grouping techniques significantly less than teachers in the other two factors, and report not taking a deliberate effort for neither ensuring students’ participation nor making themselves approachable/available to students. This combination might lead students to feel less a part of the classroom discourse, thus leading to possible difficulties in engaging in the course.

Discussion

The main goal of this research was to investigate teachers’ preferences for differentiating their instruction and thus identifying clusters of subjectivity within this group of secondary school teachers. By allowing teachers to report their preferences in using Q Methodology, this research contributes to the academic literature by offering a richer view of these preferences not available in a tradition survey/questionnaire study. Three factors or groups of teachers were identified in this study: factor #1: Competency Focused- Interest Adverse, factor #2: Operationally Focused – Mastery Adverse, factor #3: Experience Focused – Pedagogically Adverse. Each of these groups reported significantly different preferences. These preferences are created by the manner in which teachers’ conceptualize their teaching. It forms the core of their beliefs systems and thus at the heart of their teaching practices.

Teachers’ personal preferences inform and can possibly dominate their teaching practices, thus overshadowing the needs and preferences of individual students. While each factor does indeed contain differentiation elements that are evidenced-based in terms of positive effects on student learning, it could be argued that these differentiation elements are present due to teachers’ predilection to being taught in a certain manner and employing specific comfortable teaching techniques rather than teachers responding to students’ specific needs or preferences.

For example, factor #1 (Competency Focused- Interest Adverse) appears to be a teacher-centered approach due to a strong focus on skill development while taking students’ interests less into consideration as a possible medium for differentiation. This could be due to teachers’ beliefs that content in terms of information transfer is more important than using students’ interest as a catalyst for engagement. That being said, students will most likely face difficulties in engaging in this subject. As a consequence of these teachers’ preferences, students’ academic performance could be brought into jeopardy. Teachers in factor #2 (Operationally Focused – Mastery Adverse) appear to highly engage in the act of teaching, but much less than offering learning opportunities for students who have already mastered the material. If teachers choose to offer less learning opportunities to advanced students due to their concerns about individuality and equality (Norwich, Citation1994), then a link can be made between teachers’ personal beliefs and a higher risk for gifted student of disengagement. For factor #3 (Experience Focused – Pedagogically Adverse), these teachers seem be open for the employment of experience as a differentiation element. However, these teachers report much lower levels of deliberate teaching. The specific reasons for these teachers to be less engaged in deliberate teaching is not known and was not a focus of this study. However, this teaching approach, like all teaching approaches, is a personal choice based on that individual teacher’s conceptualization of teaching. As such, the potential risk to student learning remains.

Implications for student engagement and learning

The academic literature concerning student engagement demonstrates the positive effects of student engagement for academic success (Astin, Citation1984; Carini et al., Citation2006; Tinto, Citation1988; You & Sharkey, Citation2009); greater sense of being part of the classroom discourse (Reid & Solomonides, Citation2007), more likely to employ a deep approach to their learning (Horstmanshof & Zimitat, Citation2007; Jansen & Bruinsma, Citation2005). However, in order for students to choose and engage in the curriculum, there needs to be a totality of both school and classroom practices that is applicable to each individual student. This study has revealed different differentiation preferences which could be in conflict with student’s individual needs. These preferences could form an obstacle for students in terms of engaging in the curriculum.

Additionally, it must be noted that the tensions and struggles teachers face with differentiating their curriculum are complex (De Neve et al., Citation2015; Smit & Humpert, Citation2012; Tomlinson et al., Citation2003). This is due to the tension between meeting student’s individual needs and reaching mandated state standards (Van Tassel-Baska, Citation2006), lack understanding of how meta-cognition can assist in differentiation (Evans & Waring, Citation2008), potential misunderstandings concerning the elemental foundations of a supportive (motivating) classroom interactions (Nichols & Zhang, Citation2011), as well as, insufficient professional development concerning differentiation (Dixon et al., Citation2014).

Implications for teacher development

When teachers’ undergo a conceptual change regarding their teaching, changes in students’ approaches to studying occur (Ho et al., Citation2001). For example, if teachers want to reduce surface learning by students, then a conceptual change toward a more conceptual change/student-focused teaching approached is needed (Trigwell & Prosser, Citation2004). Effective professional development program aimed at improving student learning should focus on such issues (Ho et al., Citation2001). In other words, professional development programs should require teachers to firstly, to explore their personal teaching preferences and beliefs about differentiation and secondly become aware of the connection between teacher’s teaching and student’s learning and lastly, create effective and alternative teaching strategies to best reach all students in their classroom.

Besides the focus on conceptual changes in teachers, the amount of professional development, when specifically for classroom differentiation, have demonstrated positive effects for teacher efficacy (Dixon et al., Citation2014). In that same study, it was demonstrated that teachers with higher levels of efficacy, in regards to their competency in differentiating, were more likely to differentiate. In other words, teachers’ beliefs about how well they perform certain pedagogical acts lead to those same teachers to performing those acts more often. Specifically for professional development programs, there needs to be an effective learning balance for teachers between cognitive understanding of the concepts of differentiation and evidence-based “ready-to-go” strategies. The latter can allow teachers to create success experiences and thus lead to possible higher levels of teacher efficacy. Building form these success experiences, teachers that have a better cognitive understanding of the concepts of differentiation can then begin to form their own differentiation strategies which take into consideration their own personal teaching preferences and beliefs about differentiation.

Teachers’ opposition concerning differentiation due to the tension between the notions of individuality and equality also needs be addressed in professional development initiatives. This highly personal preference, that shapes differentiation, should not be seen as two separate elements. However, teachers need to see these elements as two interrelated values wherein both need to be considered when informing teachers’ classroom practices (Norwich, Citation1994). In other words, teachers need to first recognize their preference and then find a balance between both of these values in order to offer the most didactically sound differentiation to all students.

Limitations and new directions for research

While Q Methodology is an analytical technique to explore subjectivity, it explores subjectivity within a single group. Nonetheless, the context of this study and the challenges that these teachers face are similar to other secondary school teachers. The relevance and generalizability of this study could be strengthened by using this methodology in a larger setting or complementing this research methodology with qualitative research methods such as interviews or classroom observations. Additionally, supplementing this research by exploring students’ classroom experiences could possibly add additional insight into the relationship between teachers’ approaches to teaching and students’ approaches to studying. While the research’s goal was to explore teachers’ personal preferences for differentiating their instruction, deeper insight could be gained when future research focuses on possible trends in teacher characteristics per factor. However, this was not the goal is this research.

Ethical statement

This research project has been conducted within the current university guidelines: all respondents voluntarily participated, confidentiality and anonymity of the research respondents were insured by anonymous participation, no harm was incurred, and the researcher has acted independent and impartial as no vested interest in the specific outcomes was present.

References

- Aitken, J. L., & Mildon, D. (1991). The dynamics of personal knowledge and teacher education. Curriculum Inquiry, 21(2), 141–162. https://doi.org/10.2307/1179940

- Assor, A., Kaplan, H., & Roth, G. (2002). Choice is good, but relevance is excellent: Autonomy-enhancing and suppressing teacher behaviours predicting students' engagement in schoolwork. The British Journal of Educational Psychology, 72(Pt 2), 261–278. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709902158883

- Astin, A. W. (1984). Student involvement: A developmental theory for higher education. Journal of College Student Development, 40(5), 518–529.

- Bartlett, J. E., & DeWeese, B. (2015). Using the Q methodology approach in human resource development research. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 17(1), 72–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/1523422314559811

- Brighton, C., Hertberg, H., Callahan, C., Tomlinson, C. A., & Moon, T. (2005). The feasibility of high end learning in academically diverse middle schools (No. 05210).

- Carini, R. M., Kuh, G. D., & Klein, S. P. (2006). Student engagement and student learning: Testing the linkages. Research in Higher Education, 47(1), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-005-8150-9

- De Neve, D., Devos, G., & Tuytens, M. (2015). The importance of job resources and self-efficacy for beginning teachers’ professional learning in differentiated instruction. Teaching and Teacher Education, 47, 30–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2014.12.003

- Dixon, F. A., Yssel, N., McConnell, J. M., & Hardin, T. (2014). Differentiated instruction, professional development, and teacher efficacy. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 37(2), 111–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162353214529042

- Duball, B., Baker, R. (1990). Attrition in TAFE: the influences of institutional variables. TAFE National Centre for Research and Development. http://www.voced.edu.au/content/ngv%3A17297

- Entwistle, N., & McCune, V. (2004). The conceptual bases of study strategy inventories. Educational Psychology Review, 16(4), 325–345. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-004-0003-0

- Evans, C., & Waring, M. (2008). Trainee teachers’ cognitive styles and notions of differentiation. Education + Training, 50(2), 140–154. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400910810862128

- Gibbs, G. (2010). Using assessment to support student learning. Leeds Metropolitan University.

- Godor, B. P. (2016). Moving beyond the deep and surface dichotomy; using Q methodology to explore students’ approaches to studying. Teaching in Higher Education, 21(2), 207–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2015.1136275

- Hertberg-Davis, H. (2009). Myth 7: Differentiation in the regular classroom is equivalent to gifted programs and is sufficient: classroom teachers have the time, the skill, and the will to differentiate adequately. Gifted Child Quarterly, 53(4), 251–253. https://doi.org/10.1177/0016986209346927

- Ho, A., Watkins, D., & Kelly, M. (2001). The conceptual change approach to improving teaching and learning: An evaluation of a Hong Kong staff development programme. Higher Education, 42(2), 143–169.

- Horstmanshof, L., & Zimitat, C. (2007). Future time orientation predicts academic engagement among first-year university students. The British Journal of Educational Psychology, 77(Pt 3), 703–718. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709906X160778

- Jansen, E., & Bruinsma, M. (2005). Explaining achievement in higher education. Educational Research and Evaluation, 11(3), 235–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803610500101173

- Kagan, D. M. (1992). Professional growth among preservice and beginning teachers. Review of Educational Research, 62(2), 129–169. https://doi.org/10.2307/1170578

- Kember, D., & Gow, L. (1994). Orientations to teaching and their effect on the quality of student learning. The Journal of Higher Education, 65(1), 58–74. https://doi.org/10.2307/2943877

- Landis, R. N., & Reschly, A. L. (2013). Reexamining gifted underachievement and dropout through the lens of student engagement. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 36(2), 220–249. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162353213480864

- Lundberg, A. (2019). Teachers’ viewpoints about an educational reform concerning multilingualism in German-speaking Switzerland. Learning and Instruction, 64, 101244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2019.101244

- Marshall, K. (2016). Rethinking differentiation—Using teachers’ time most effectively. Phi Delta Kappan, 98(1), 8–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/0031721716666046

- McKeown, B. F., & Thomas, D. B. (2013). Q methodology (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc.

- McLeod, S. (1995). Pygmalion or Golem? Teacher affect and efficacy. College Composition and Communication, 46(3), 369–386. https://doi.org/10.2307/358711

- McTighe, J., & O’Connor, K. (2005). Seven practices for effective learning. Educational Leadership, 63, 10–17.

- Meeuwisse, M., Severiens, S. E., & Born, M. P. (2010). Learning environment, interaction, sense of belonging and study success in ethnically diverse student groups. Research in Higher Education, 51(6), 528–545. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-010-9168-1

- Nichols, J. D., & Zhang, G. (2011). Classroom environments and student empowerment: An analysis of elementary and secondary teacher beliefs. Learning Environments Research, 14(3), 229–239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-011-9091-1

- Norwich, B. (1994). Differentiation: From the perspective of resolving tensions between basic social values and assumptions about individual differences. Curriculum Studies, 2(3), 289–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965975940020302

- Øverland, K., Størksen, I., & Thorsen, A. A. (2013). Daycare children of divorce and their helpers. International Journal of Early Childhood, 45(1), 51–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-012-0065-y

- Reid, A., & Solomonides, I. (2007). Design students’ experience of engagement and creativity. Art, Design and Communication in Higher Education, 6(1), 25–39.

- Reis, S. M., & Renzulli, J. (2010). The schoolwide enrichment model: A focus on student strengths and interests. Gifted Education International, 26(2–3), 140–157. https://doi.org/10.1177/026142941002600303

- Richardson, J. T. (2005). Students’ approaches to learning and teachers’ approaches to teaching in higher education. Educational Psychology, 25(6), 673–680. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410500344720

- Rosenthal, R., & Jacobson, L. (1968). Pygmalion in the classroom: Teacher expectation and pupils’ intellectual development. Rinehart and Winston.

- Santangelo, T., & Tomlinson, C. A. (2012). Teacher educators’ perceptions and use of differentiated instruction practices: An exploratory investigation. Action in Teacher Education, 34(4), 309–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/01626620.2012.717032

- Schmoker, M. (2010, September 29). When pedagogic fads Trump priorities. Education Week. https://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2010/09/29/05schmoker.h30.html

- Severiens, S. E., & Schmidt, H. G. (2009). Academic and social integration and study progress in problem based learning. Higher Education, 58(1), 59–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-008-9181-x

- Smit, R., & Humpert, W. (2012). Differentiated instruction in small schools. Teaching and Teacher Education, 28(8), 1152–1162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2012.07.003

- Spurgeon, L., Humphreys, G., James, G., & Sackley, C. (2012). A Q-methodology study of patients' subjective experiences of TIA. Stroke Research and Treatment, 2012, 486261. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/486261

- Stephenson, W. (1935). Correlating persons instead of tests. Journal of Personality, 4(1), 17–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1935.tb02022.x

- Stephenson, W. (1953). The study of behavior: Q-technique and its methodology (5th Impression ed.). University of Chicago Press.

- Stephenson, W. (1993). Introduction to Q-methodology. Operant Subjectivity, 17(1), 1–13.

- Tinto, V. (1988). Stages of student departure: Reflections on the longitudinal character of student leaving. The Journal of Higher Education, 59(4), 438–455. https://doi.org/10.2307/1981920

- Tomlinson, C. A. (1999). The differentiated classroom: Responding to the needs of all learners. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

- Tomlinson, C. A. (2010, November 12). When pedagogical misinformation Trumps reason. Education Week. https://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2010/11/17/12letter-b1.h30.html

- Tomlinson, C. A., Brighton, C., Hertberg, H., Callahan, C. M., Moon, T. R., Brimijoin, K., Conover, L. A., & Reynolds, T. (2003). Differentiating instruction in response to student readiness, interest, and learning profile in academically diverse classrooms: A review of literature. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 27(2–3), 119–145. https://doi.org/10.1177/016235320302700203

- Trigwell, K., & Prosser, M. (2004). Development and use of the approaches to teaching inventory. Educational Psychology Review, 16(4), 409–424. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-004-0007-9

- van Exel, J., Baker, R., Mason, H., Donaldson, C., Brouwer, W, & EuroVaQ Team. (2015). Public views on principles for health care priority setting: Findings of a European cross-country study using Q methodology. Social Science & Medicine, 126, 128–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.12.023

- Van Tassel-Baska, J. (2006). A content analysis of evaluation findings across 20 gifted programs: A Clarion call for enhanced gifted program development. Gifted Child Quarterly, 50(3), 199–215. https://doi.org/10.1177/001698620605000302

- Yeung, A. S., Craven, R. G., & Kaur, G. (2014). Teachers’ self-concept and valuing of learning: Relations with teaching approaches and beliefs about students. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 42(3), 305–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2014.905670

- You, S., & Sharkey, J. (2009). Testing a developmental-ecological model of student engagement: A multilevel latent growth curve analysis. Educational Psychology, 29(6), 659–684. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410903206815

- Zabala, A. (2014). qmethod: A package to explore human perspectives using Q methodology. A Peer-Reviewed, Open-Access Publication of the R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 6(2), 163. https://doi.org/10.32614/RJ-2014-032