Abstract

Differentiation has gained increasing attention in contemporary pedagogy as an approach to cater for student diversity. However, particularly novice and pre-service teachers seem to struggle with applying it in practice. The aim of this study was to increase pre-service English teachers’ understanding of differentiation in Finland. Differentiation was approached through the 5-Dimensional (5 D) model of differentiation created by the author (e.g., Roiha & Polso, Citation2021b). The data of the study are 14 students’ learning journals written at the end of the course in which they reflected on the course content. The data were analyzed following thematic analysis. The findings showed that some students had formed a fairly progressive and wide understanding of differentiation whereas others still perceived it in a more restricted way. While almost all students regarded differentiation as highly important, many voiced several challenges for its effective implementation. Overall, the findings of this study imply that although the 5 D model had provided the students with a basic understanding of differentiation, many students still viewed differentiation predominantly through teaching methods. Therefore, it would be important in the future to emphasize other dimensions of the model, such as assessment or learning environment, to expand students’ perceptions of differentiation even more.

Introduction

Differentiation has become a popular teaching approach in many educational contexts in recent years. There, however, seems to be a lack of a shared vision on differentiation as it is perceived somewhat differently among scholars and practitioners (e.g., Civitillo et al., Citation2016; Graham et al., Citation2021; Roiha, Citation2014; Roiha & Polso, Citation2021b). Sometimes differentiation is predominantly defined as a reactive approach which concerns primarily ability levels (e.g., Hall, Citation2002; Roy et al., Citation2013; Saloviita, Citation2018) or as merely a set of teaching practices (e.g., Benjamin, Citation2002). Other times differentiation is understood more progressively as a proactive and comprehensive teaching approach where students’ individuality is profoundly addressed (e.g., Roiha & Polso, Citation2021b; Tomlinson, Citation2014). The key characteristics of broad conceptualizations of differentiation is to view it both as a proactive and reactive approach that entails all learners and is at the responsibility of the entire school community (see e.g., Roiha & Polso, Citation2021b for a more detailed discussion on the different definitions of differentiation).

Despite the growing interest in differentiation, teachers have struggled with its purposeful implementation. The most commonly mentioned challenges have been large class sizes, time constrains, impractical physical environment, teaching materials, lack of knowledge of effective differentiation methods, lack of collaborative planning time and lack of administrative support (e.g., Berbaum, Citation2009; Hertberg-Davis & Brighton, Citation2006; Roiha, Citation2014; Santangelo & Tomlinson, Citation2012; Tomlinson & Imbeau, Citation2010; VanTassel-Baska & Stambaugh, Citation2005; Wan, Citation2016). Particularly novice teachers are often overwhelmed by the expectations to consider each student’s individuality (e.g., Fantilli & McDougall, Citation2009; Mansfield et al., Citation2014; van Geel et al., Citation2019).

The aim of this article is to make its contribution to research on differentiation from pre-service teachers’ perspectives. More specifically, the purpose of the article is to shed more light on pre-service language teachers’ beliefs and understanding of differentiation and how their teacher training contributes to this, which is a relatively under-researched topic. The participants of the study are future English language teachers (N = 14) who were completing their one-year pedagogical studies at a teacher education department at a Finnish university. The data used are the participants’ learning journals in which they reflected on differentiation, a topic which was covered in the course. In this study, the development of the students’ understanding of differentiation and the potential of the 5 D model as a pedagogical tool in pre-service teacher education is explored. The specific research questions that are addressed in this study are as follows:

What kind of perception of differentiation have the participants (N = 14) formed based on the course and the 5 D model?

What challenges and opportunities do they identify for differentiation?

Pre-service teachers’ perceptions of differentiation

Although most research on differentiation has dealt with in-service teachers, pre-service teachers’ outlook on differentiation has also been the scope of a few earlier studies. Some studies have reviewed how differentiation is addressed in the curricula of teacher education programs. It seems that differentiation often receives very little attention in teacher education (e.g., Allday et al., Citation2013; Brevik et al., Citation2018; D’Intino & Wang, Citation2021). Bearing on this, Smets (Citation2017) has aptly stated that both pre- and in-service teacher education will be increasingly challenged to prepare teachers to meet the diversity of students through differentiation.

In light of the above, it may not be too surprising that pre-service teachers have found to hold a somewhat restricted and narrow perception of differentiation. In Nepal et al. (Citation2021) study, Australian pre-service teachers mostly perceived differentiation as a set of practical tools that should be predominantly targeted on struggling learners and mostly focused on visible differences among the students. They also felt unconfident and unprepared to implement differentiation in practice. This was also the case with the student teachers in Brevik et al. (Citation2018) study with regard to differentiation for high-achieving students and in Dack’s (Citation2019) study on teacher candidates’ conceptions of differentiation. Dee (Citation2010) found that pre-service teachers did not pay a lot of attention to differentiation in their lesson plans. Moreover, many students had an underdeveloped understanding of differentiation and most of them stated that differentiation is not required in their lessons.

Positively, however, in Wan’s (Citation2016) and Dack’s (Citation2019) studies, offering courses on differentiation during pre-service teacher training led to a broader understanding of the approach and more positive attitudes toward it. Evans-Hellman’s and Haney’s (Citation2017) study, in turn, revealed that 90 percent of the pre-service teacher participants were planning to differentiate in their future teaching which coincides with a similar result by Joseph et al. (Citation2013) with 88 percent of the pre-service teacher respondents intending to act similarly. In Goodnough’s (Citation2010) study with pre-service science teachers, addressing differentiation in their training increased most students’ understanding of the approach and made them review the curriculum, learning and assessment from the perspective of differentiation.

Differentiation in Finland

Differentiation is strongly present in the Finnish educational landscape, at least on a discourse level. This is the case particularly in basic education, since the Finnish National Core Curriculum for Basic Education (FNCCBE, Citation2014) urges all teachers to differentiate their teaching. The curriculum stipulates that: ‘The selection of working methods is guided by differentiation of instruction. Differentiation is based on the teacher’s knowledge of their pupils’ personal needs. It is the pedagogical point of departure for all instruction’ (FNCCBE, Citation2014, section 4.3). Moreover, for foreign languages, the curriculum (FNCCBE, Citation2014) specifies that support is provided for pupils with learning difficulties connected to languages. The instruction is planned to offer challenges also for those advancing faster or those with previous proficiency in English.

The Finnish National Core Curriculum for General Upper Secondary Education (FNCCGUSE, Citation2019), in turn, mentions differentiation only three times, twice in the general section and once in relation to physical education. The curriculum states that ‘the instruction should be differentiated considering each student’s individual background, needs, aims, hobbies, interests, areas of expertise and factors affecting their current life situation’ (FNCCGUSE, Citation2019, p. 27) (author’s translation). Moreover, in relation to supporting students’ learning the curriculum states that ‘The methods of support can be for instance differentiation, remedial teaching and other pedagogical solutions’ (FNCCGUSE, Citation2019, p. 31) (author’s translation). Interestingly, the curriculum for general upper secondary education seems to reflect a somewhat narrow perception of differentiation as it distinguishes between differentiation and remedial teaching whereas when perceiving differentiation holistically, remedial teaching can be considered one differentiation practice. It is a central differentiation method also in the 5 D model pertaining to teaching arrangements (see the section The 5-Dimensional model of differentiation).

Differentiation has not been extensively studied in Finland. In Roiha’s (Citation2014) study, Finnish CLIL (Content and Language Integrated Learning) teachers (N = 51) seemed to differentiate their teaching in a fairly versatile way. Among commonly used differentiation methods were expecting individual accomplishment, offering individual support, providing extensive visual and oral support during teacher talk and employing flexible grouping. On average, most teachers seemed to think that differentiation is equally important for underachieving and gifted pupils and that both dimensions of differentiation are equally challenging. However, 12 teachers considered differentiation for underachieving pupils to be more important whereas no-one thought the contrary. Similarly, 17 of the teachers considered differentiation easier for underachieving than gifted pupils whereas only seven held the opposite view. The teachers also identified several challenges for effective differentiation which echo other studies (e.g., Hertberg-Davis & Brighton, Citation2006; Tomlinson & Imbeau, Citation2010), namely lack of time and resources, teaching material, physical classroom environment and large class sizes.

Saloviita (Citation2018) examined Finnish in-service teachers’ (N = 2276) use of co-teaching, group work and differentiation. Forty-two percent of the teachers used co-teaching and 43 percent group work at least every week, whereas 83 percent of the teachers reported using differentiation regularly. Subject teachers was the group that differentiated the least (i.e., 69%) compared to classroom teachers and special education teachers. This, in its part, speaks for the importance of incorporating differentiation into pre-service subject teachers’ training more than is done at present. As a limitation to Saloviita’s (Citation2018) study, differentiation was not defined in the survey and teachers merely had to choose between yes and no regarding a statement ‘I differentiate the instruction on a regular basis’.

Laari et al. (Citation2021) examined the use of the 5 D model among Finnish in-service teachers (N = 40). On average, differentiation seemed to be strongly present in the teachers’ teaching praxis. The most used dimensions were teaching methods, learning environment and assessment, whereas support materials and teaching arrangements received the least attention. However, each dimension was utilized relatively often which suggests that the 5 D model covers the basic tenets of differentiation in a fairly balanced manner.

The few Finnish studies on differentiation have focused on in-service classroom teachers making pre-service teachers’ perceptions of differentiation a somewhat uncharted territory in Finland. In general, most previous studies on pre-service teachers’ conceptions of differentiation have focused on classroom teachers and not so much on subject teachers (e.g., Brevik et al., Citation2018; Nepal et al., Citation2021). Particularly pre-service language teachers’ understanding of differentiation is a fairly unexplored terrain. The aim of the present study is thus to fill this gap by bringing valuable information on pre-service language teachers’ understanding of differentiation in the Finnish education context. This is important since Saloviita’s (Citation2018) study revealed that subject teachers differentiate their teaching less than classroom teachers and special education teachers. Moreover, in this study, the 5 D model is used as the framework for differentiation, which provides more empirical information on its usefulness (see also Laari et al., Citation2021). Finally, Finnish teacher education is a fruitful context to examine also for the reason that it has a high reputation and it has received a lot of international attention in recent years (e.g., Tirri, Citation2014). As differentiation is an integral part of the national curricula, all pre- and in-service teachers can be expected to differentiate their teaching in a wide manner. In what follows, the theoretical background of the 5 D model and the methods of the study are briefly presented. After that, the findings of the study are discussed according to the research questions and implications are drawn based on them.

The 5-Dimensional model of differentiation

There has been an abundance of differentiation models established in the past few decades (see Roiha & Polso, Citation2021b for an overview). Scholars such as Tomlinson (Citation2014), Smets (Citation2017), Prast et al. (Citation2015), Rock et al. (Citation2008) or Reis and Renzulli (Citation2015) have made their valuable contribution to the conceptualization of differentiation. Notwithstanding the above models, differentiation has been regarded challenging and tedious to implement (e.g., Santangelo & Tomlinson, Citation2012; VanTassel-Baska & Stambaugh, Citation2005; Wan, Citation2016), which has motivated the creation of the 5-Dimensional (5 D) model of differentiation. The 5 D model aims to offer a clearer and more tangible approach to differentiation than some of the previous models. The model for instance expands the responsibility of differentiation to the entire school community and dedicates a dimension to support materials in differentiation which are often implicit in other models. The 5 D model is created in the Finnish context with the purpose of alleviating the challenges of teaching diverse classrooms. The 5 D model is based on the assumption that pupils’ interests and prior knowledge are the foundation of all differentiation. Moreover, teachers are advocated to provide all pupils with challenges that are at an appropriate level for each learner and to acknowledge the different profiles of pupils in their teaching.

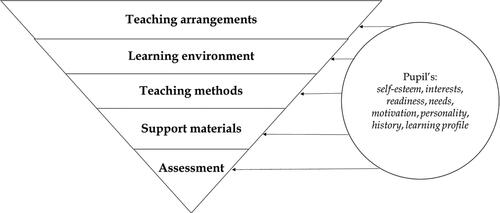

The model distinguishes five dimensions of differentiation, namely teaching arrangements, learning environment, teaching methods, support materials and assessment (see ). The model progresses from general to specific. That is, the first two dimensions (i.e., teaching arrangements and learning environment) are more macro-level dimensions which lay the grounds for more detailed differentiation in dimensions three to five (i.e., teaching methods, support materials and assessment). All differentiation in the 5 D model stems from pupils’ individual features such as learning profile, self-esteem, interests, readiness, needs, motivation, personality and history (for a more detailed discussion of the model, see Roiha & Polso, Citation2021a, Citation2021b).

Figure 1. The 5-Dimensional model of differentiation (Adapted from Roiha & Polso, Citation2020).

Methods

The purposes of this cross-sectional qualitative study were twofold. One aim was to investigate the pre-service teachers’ understanding of differentiation at the end of their course. Another aim was to get an indication of the usefulness of the course based on the students’ reflections. The students’ learning journals offered insights into how deeply they had understood the concept of differentiation and its implementation. Based on the findings, the author assessed the strengths and weaknesses of the course design and made relevant changes to it to provide future students with even broader perspective of differentiation. As an example, more time will be dedicated to the role of assessment and learning environment in differentiation as these dimensions received little attention in many students’ learning journals (see the Findings section).

Participants and context

The participants of the study are 14 pre-service teachers who were completing their pedagogical studies at a teacher education department at a Finnish university. They were all English major students and thus studied to become future English teachers. All in all, 23 students took part in the course from which the data originate. In the course, the students received lectures and small group sessions on differentiation in foreign language teaching. Differentiation was approached through the 5 D model (see e.g., Roiha & Polso, Citation2021a, Citation2021b). In the lectures, differentiation was first conceptualized and its theoretical underpinnings presented. Then a variety of previous differentiation models and precepts were presented (e.g., Tomlinson, Citation2014; Prast et al., Citation2015; Smets, Citation2017). The final part of the lectures focused on introducing the 5 D model, first generally and then in relation to foreign language teaching. During the lectures, students had group activities in which they had to reflect on their own experiences of differentiation from their school times and also how it had been dealt with in the teacher training schools.

Following the lectures, the students had small group sessions where the topic of differentiation was further discussed. Prior to the sessions, the students were expected to read a chapter on the 5 D model and how it can be used in the differentiation of language teaching as a pre-reading. During the sessions, the students worked in small groups and first invented an imaginary class with several pupils with special needs. The class descriptions were then rotated so that each group got another group’s imagined class. The groups then had to create a unit plan for the class and come up with a variety of differentiation practices in each dimension of the 5 D model. The work was done in groups of four which enabled and incited the exchange of ideas and promoted peer learning.

The students were given a choice to choose their final assessment method between a learning journal and a book exam, a practice which, in itself, modeled differentiated assessment to the students. Only two students opted for the exam while the others chose the learning journal. Learning journals were chosen as the other method of assessment for the course as their use has been shown to promote self-reflection and learning among students (Lew & Schmidt, Citation2011). Moreover, writing as a pedagogical practice has been found to contribute to the professional development of pre-service teachers (e.g., Arshavskaya, Citation2017; Johnson & Golombek, Citation2011). For the learning journal, the students were asked to reflect on three out of 12 course themes. Out of the 21 students who had chosen learning journals as an assessment method, 15 students had decided to discuss differentiation in their journals which illustrates the importance of the topic to the students. All 15 of them were approached to take part in the study retrospectively and all but one gave their consent to use their learning journals as the data for this study.

Research ethics

All relevant ethical measures have been taken in this research. The Ethics Committee for Human Sciences at the university was consulted and it was deemed that their approval was not needed since the study was on a voluntary basis and did not cause any harm to the participants. All the participants were thoroughly informed about the research and they all signed a consent form to take part in the research. It was clearly communicated to them that they had the right to withdraw from the study at any point. It was further emphasized that their decision to take part in the research had no effect on their course grading. In addition, a privacy notice was provided to the participants which explained how personal data would be processed. All direct identifiers were removed prior to the analysis and the data were transferred to a separate word file. The participants are referred to with pseudonyms in the article. They have not read each other’s learning journals and cannot therefore recognize each other in the research report, which further protects their privacy.

Data collection and analysis

The data used in this article are students’ learning journals, and more specifically the parts in which they discuss differentiation. The students submitted their learning journals a few weeks after the course finished but they were advised to write down some tentative notes after each session. Some guiding questions were provided to the students to aid their writing but it was explicitly mentioned that these were merely suggestive and that the students did not need to adhere to these questions. The instructions were to write approximately 750–1000 words per topic and the students were expected to use at least two new references to inform their views in the journals in addition to the ones provided in the lectures. Therefore, all in all the data used in this study are approximately 11 700 words of text.

The data were subjected to thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). The analysis can be labeled theory-oriented (Eskola, Citation2018) since it was informed by the theoretical underpinnings of differentiation as well as the conceptualization of differentiation in the 5 D model but was nevertheless open to the data and themes emerging from them. Eskola (Citation2018) places this type of analysis in between the deductive/inductive dichotomy. Fereday and Muir-Cochrane (Citation2006), in turn, label this a hybrid approach to data analysis. What this means in the present study is that the dimensions of the 5 D model (teaching arrangements, learning environment, teaching methods, support materials and assessment) worked as a priori codes that directed the analysis. The analysis, however, went deeper than that and aimed to capture the participants’ understanding of differentiation based on their described differentiation practices. That is, the students’ who mentioned only a few differentiation practices and focused on one or two dimensions of the 5 D model were interpreted to hold fairly limited views on differentiation. Conversely, the ones who discussed several practices on all or most dimensions of the model were interpreted to have a broad understanding of differentiation. It is an implicit postulate that the differentiation practices described by the participants reveal something about their underlying perceptions of differentiation. In addition, the conceptualization of differentiation as a proactive and comprehensive teaching approach served as lenses in the analysis. The data were examined in terms of how the students described differentiation which further uncovers their understanding of it. The challenges of differentiation also worked as a priori theme through which to analyze the data. However, the associated themes were formed inductively based on the data.

In practice, the entire dataset was first read through two times and coded the latter time. The initial codes were the types of differentiation practices the students mentioned (e.g., seating arrangements, flexible grouping) and the way differentiation was described in general (e.g., proactive, time-consuming, important). Following the guidelines of systematic and rigorous thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006), the codes were further analyzed by grouping them together and forming broader themes. The final themes of the analysis were “students’ perception of differentiation and the 5 D model” and “the challenges of differentiation”. The findings that follow are presented according to the abovementioned main themes. Both sections are further divided into subsections based on the corresponding subthemes. The students wrote their learning journals in Finnish, therefore the quotations incorporated in the Findings section have been translated into English by the author.

Findings

Students’ perceptions of differentiation after the course

The importance of differentiation

Differentiation was almost exclusively seen as an important and interesting concept. It was for instance described as ‘the cornerstone of good teaching’ (Riku) and as ‘the pocketknife of teacher’s toolkit’ (Rasmus). Riku further explained that:

The topic interests me, since I find differentiation to be one of the things that differentiates a good teacher from excellent one. (Riku)

Most students seemed to think that it is important to differentiate for all pupils, but a few students explicitly mentioned how they felt that it is more important to support the underachieving students. Lisa stated the following on the topic:

I could imagine that it is better to first support the students who have fallen behind and get them to learn the essential content, because they will certainly be more disadvantaged in the future than those who are gifted and who may be frustrated with the pace of the lessons and could progress faster. (Lisa)

Reported satisfaction with the course and the 5 D model

Overall, the students were satisfied with the course and perceived differentiation as a topic that was important to cover with future language teachers. The students explicitly mentioned how the course provided them with concrete tools to implement differentiation. For instance, Ida stated how the course made her realize how differentiation also supports Krashen’s (Citation1985) input hypothesis theory, a seminal second language acquisition theory that postulates that students will acquire the language if teachers provide them with enough comprehensible input.

The fundamental aim of the course was to broaden the pre-service students’ perceptions of differentiation. Based on their learning journals, the self-reported perception of most students was that the course had indeed deepened their understanding of differentiation as an educational approach. The following quotation from Rasmus exemplifies this:

Differentiation for gifted or underachieving students was clear already before the course but I didn’t really think of differentiating the learning objectives of learners, let alone group level differentiation where you take the whole group’s special needs into account. Through the lecture I also realized that in order to differentiate, it is essential to know your pupils. (Rasmus)

As a future teacher, the 5 D model seems like a clear and approachable starting point. I feel like I can apply it in my own teaching, because I would like to strive for differentiated teaching that takes into account the individual needs of each student. It seems easy to approach differentiation through the model, as it offers concrete means of differentiation in different sub-areas, always based on the student. (Ella)

Narrow views on differentiation

One of the main goals of the course was that differentiation would become a natural and inherent part of the students’ teaching philosophies. It was further desired that the students would gain a broad and progressive understanding of differentiation according to which it is seen as a pervasive teaching approach that transcends all teaching (e.g., Roiha & Polso, Citation2021b; Tomlinson, Citation2014). Even though most students’ self-reported belief was that the course had provided them with a broad perception of differentiation, the learning journals revealed that the students’ conceptions of differentiation seemed to vary to some extent. Two groups could be identified in the data concerning the students’ stance on differentiation. The first group consisted of students whose learning journals depicted a fairly narrow and restricted view on differentiation. They seemed to perceive differentiation mostly as a mechanical set of practices or something extra that one adds on top of regular teaching. The students in this group mostly focused on teaching methods which are only one part of differentiation in the 5 D model (e.g., Roiha & Polso, Citation2021b). These limited views echo many previous studies on pre-service teachers’ perceptions of differentiation (e.g., Dack, Citation2019; Nepal et al., Citation2021).

Arttu was one example of students holding limited views of differentiation as he wrote in his journal as follows:

I am going to adopt some (author’s emphasis) of the features of differentiation in my own teaching. However, it is not worth to differentiate all the time since challenges are also useful for pupils. (Arttu)

Remedial teaching is more beneficial than differentiation. Differentiating for underachieving pupils would lead to students falling further behind and that’s why I’m not entirely sure if that makes sense (Arttu)

Broad views on differentiation

The second group comprised students who reflected on differentiation in a relatively progressive manner. That is, they mentioned that differentiation involves all learners and emphasized that knowing one’s pupils well works as the premise for all differentiation. Furthermore, their journals reflected the idea that differentiation creates the foundation for all teaching which is in line with the broad definitions of differentiation (e.g., Roiha & Polso, Citation2021b; Tomlinson, Citation2014) as well as with the national curriculum for basic education in Finland (FNCCBE, Citation2014). For instance, according to Rasmus:

Differentiation is a central part of the teaching that I personally see as ideal for language learning. (Rasmus)

With regard to the dimension of support materials, a few students discussed digitalization and its potential in differentiation in their journals. Rasmus, for instance, mentioned how digital learning platforms can be used for differentiation since they offer challenges for different learners. It was somewhat surprising that not more students talked about information and communication technology (ICT) since it is part of contemporary education and also strongly present in both national curricula as one of the transversal competencies that should transcend all teaching (FNCCBE, Citation2014; FNCCGUSE, Citation2019). ICT, and the wealth of possibilities it offers for differentiation, was also covered in the course since it is an essential part of the dimension of support materials in the 5 D model (Roiha & Polso, Citation2021b). Deunk et al. (Citation2018) meta-analysis gives further support to the use of ICT in differentiation since it evidenced the benefits of using computer technology in differentiation.

Learning environment and assessment were the dimensions of the 5 D model that received the least attention from the students (cf. support materials and teaching arrangements in Laari et al. (Citation2021)). Only four students altogether addressed assessment in their journals even though it is a key aspect in the 5 D model and also highlighted in many previous differentiation models (e.g., Tomlinson, Citation2014; Prast et al., Citation2015; Rock et al., Citation2008). Particularly diagnostic and formative assessment are seen as pivotal in differentiation (e.g., Guskey & McTighe, Citation2016; McGlynn & Kelly, Citation2017). Similarly, only a few students discussed learning environment and its differentiation in their journals even though it is an essential part of differentiation and affects students’ learning (e.g., Murillo & Roman, Citation2011; Yeager & Walton, Citation2011). This was a valuable finding for future years when delivering the same course.

Oscillating between broad and narrow views on differentiation

In addition to the main distinction between narrow and broad perceptions of differentiation, a few students’ reflections on differentiation seemed to oscillate between progressive and restrictive views of the approach. Riku was an example of this as he talked about using transversal projects of pupils’ own choice in differentiation for gifted students which coincides with modern views of differentiation (e.g., Tomlinson, Citation2014). On the other hand, Riku mostly wrote about providing students with different level activities from the course book which is one differentiation practice pertaining to teaching methods but nevertheless represents a fairly limited take on differentiation.

Similarly, even though Arttu mainly expressed fairly restricted views on differentiation as evidenced above, his journal also included some progressive elements of differentiation. For instance, he wrote that the greatest insight he had gained from the course was the realization that differentiation does not necessarily mean differentiating the quantity of assignments but rather the quality. Arttu further explained how he will try to give different instructions to the same assignments in order for everyone to work on challenges that are appropriate for them, which is well in line with Vygotsky’s (Citation1978) zone of proximal development and progressive views on differentiation.

Challenges of differentiation

A lack of resources

The students raised several challenges for differentiation in their learning journals. This was also one of the suggestive questions for them to address in their journals. The most prominent challenge voiced by the students was the lack of proper resources which was reflected in most dimensions of the 5 D model. Many felt that for instance co-teaching, teaching assistant and appropriate support materials require financial resources and they had reservations as to whether most schools could accommodate these. The lack of resources was also linked to large group sizes which was seen as a notable challenge for differentiation.

These reflections from the students are interesting since most of them have very limited practical teaching experience themselves. Thus, they are mostly echoing the discourse of in-service teachers with regard to the challenges of differentiation (e.g., Santangelo & Tomlinson, Citation2012; VanTassel-Baska & Stambaugh, Citation2005). The challenges of differentiation were also addressed in the course which could also explain their strong presence in the learning journals. However, a lot of time in the course was also dedicated for solutions to overcome the obstacles for differentiation.

The challenge of being a novice or subject teacher

Some students mentioned that already teaching itself is challenging and adding differentiation to it makes it even more demanding. For instance, Ida’s quotation exemplifies this as she stated the following:

As future teacher I find differentiation still relatively challenging. The classroom setting still feels like a chaos. There are a lot of things that you need to take into account and most of your focus goes on details like giving clear instructions. Seeing the bigger picture is challenging. I plan my teaching very thoroughly and I think of differentiation already before the lessons. However, often the situations where you need to differentiate are subject- and situation-specific so that meticulous preparation has not served itself in a situation where I have found a student in need of help. (Ida)

Laura was one of those who felt that being a subject teacher makes differentiation even more challenging:

As a subject teacher, I think differentiation can be difficult depending on the school you end up working in. A high school teacher may see a pupil in only one course. Also, in a busy environment, you may not notice if a pupil is in need of differentiation, or information is not flowing within the school. I was left wondering about the resources and how much effort teachers want to put in differentiation. For example, if a pupil has dyslexia, does the teacher start editing their materials or producing completely new material using plain language even if the teacher teaches the pupil in only one course? (Laura)

Discussion and conclusion

The aim of this study was to provide information on pre-service language teachers’ perceptions of differentiation, a topic on which there are relatively few studies. On the whole, it seemed that the participants had understood the importance of differentiation and had formed a basic understanding of it. The participants still voiced many prospective challenges for differentiation which correspond to the ones identified in previous research (e.g., Roiha, Citation2014; Santangelo & Tomlinson, Citation2012; Tomlinson & Imbeau, Citation2010; VanTassel-Baska & Stambaugh, Citation2005). Positively, however, most challenges mentioned by the participants (e.g., lack of resources, large class sizes, ineffective cooperation between teachers) are not insurmountable and can be overcome with the right mindset and support. The challenges related to being a novice and subject teacher highlight the importance of developing more practical solutions to support newly qualified subject teachers in differentiation. This is particularly important as subject teachers seem to differentiate their teaching less than classroom teachers or special needs teachers do (e.g., Saloviita, Citation2018).

Many models and frameworks have been created for differentiation throughout the years (e.g., Tomlinson, Citation2014; Prast et al., Citation2015; see Roiha & Polso, Citation2021b for a more detailed discussion). In this study, the potential of the 5 D model to broaden pre-service language teachers’ perceptions of differentiation was investigated with the fundamental aim of making it a paramount component of their teaching. Overall, the findings of this study consolidated the view that the 5 D model provides a tangible and concrete framework for pre-service language teachers to address differentiation in their teaching, which is in line with Laari et al. (Citation2021) study. Based on the learning journals, the course had reinforced the students’ views on the significance of differentiation and offered them practical tools to implement it. Moreover, the 5 D model seemed to provide the students with a basic, albeit somewhat limited, understanding of differentiation from which to work toward a more profound conception of the approach.

The learning journals, however, revealed that the students were at different stages in their perceptions of differentiation. While some students demonstrated relatively progressive and broad understandings of differentiation, many students seemed to hold a more restricted and narrow view of the approach, which is in line with studies by Brevik et al. (Citation2018), Dack (Citation2019), Dee (Citation2010) and Nepal et al. (Citation2021). It could also be argued that not all students had fully embraced the national core curriculum which underscores differentiation and sees it as the pedagogical point of departure for all instruction (FNCCBE, Citation2014). They associated differentiation mostly with teaching methods which is only one dimension of differentiation in the 5 D model. This suggests that more time should be dedicated to other dimensions of the model, particularly to assessment and learning environment since these were the dimensions that received the least attention in the students’ journals. Based on these findings, modifications and adjustments will be made to the course design to address the above issue in future years. Positively though, all of the students considered differentiation important and were willing to implement it in their future teaching. Differentiation is thus a topic that seems to resonate with pre-service teachers and more time should be dedicated to it in teacher education programs. Another practical implication from the study is that differentiation needs to be given more attention throughout the pedagogical studies and it should be covered more in-depth also in relation to other language teaching topics. That way it can become a natural and inherent part of all teaching and not something that is seen as an add-on to teachers’ workload.

Although the participants’ pre-understanding of differentiation was not measured in the present study, the data suggest that they experienced growth in their understanding of differentiation. Most students also explicitly stated this in their journals. Similarly, Wan’s (Citation2016) and Dack’s (Citation2019) studies demonstrated that offering courses on differentiation during pre-service teacher training can lead to broader understanding of the approach and more positive attitudes toward it. It is also worth noting that many students in the present study did not have any prior knowledge on differentiation and they encountered the notion in the course for the first time. In light of this, the learning journals also demonstrate in-depth reflections on and positive aspects of differentiation. In line with the general idea that teacher education only provides tools for lifelong learning and does not produce complete teachers, the assumption is that pre-service teachers will also keep on learning and forming their own approaches to differentiation. Therefore, the fact that some students seemed to have a more restricted and narrow view on differentiation does not mean that they are not able to broaden their perspective and gain a deeper understanding of the notion in the future. Just as differentiation is considered a constantly evolving process that does not have an endpoint (e.g., Roiha & Polso, Citation2021b; Tomlinson, Citation2014), so too are teachers expected to continuously update their knowledge and understanding of differentiation.

Finally, it is important to bear in mind that the learning journals only offer us insights into the students’ perceptions of differentiation and not on their actual differentiation practices. Dack (Citation2019) has accurately brought up the importance of distinguishing between pre-service teachers’ understanding of differentiation, their beliefs about its importance and their actual implementation of differentiation in practice. Only the two first dimensions were at the scope of the present research. It may be that the positive discourse about differentiation by some students in the present study does not necessarily translate into teaching. Follow-up data would thus be needed to see how these pre-service language teachers’ attitudes toward differentiation possibly change when entering the work life. For instance, in Tomlinson et al. (Citation1997) study, pre-service teachers had received training on differentiation prior to their teaching which had resulted in their increasing appreciation toward the need to differentiate and willingness to do so effectively. However, when observed during their teaching period, their differentiation in practice was fairly limited. Secondly, an important point to note is that only 15 out of 21 students had chosen to address differentiation in their learning journals. It can be interpreted that the remaining six students deemed the other themes in the course more important. It would be interesting to inquire into their views on differentiation and see whether they differ from those of the participants in this study. Despite its limitations, the present study supports the importance of addressing differentiation thoroughly in pre-service language teacher education. Moreover, the findings of the study imply the potential of approaching differentiation through the 5 D model and its theoretical underpinnings as long as all the dimensions of the model are comprehensively covered with the students.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Ahtiainen, R., Beirad, M., Hautamäki, J., Hilasvuori, T., & Thuneberg, H. (2011). Samanaikaisopetus on mahdollisuus. Tutkimus Helsingin pilottikoulujen uudistuvasta opetuksesta. The Education Department of Helsinki.

- Allday, R. A., Neilsen-Gatti, S., & Hudson, T. M. (2013). Preparation for inclusion in teacher education pre-service curricula. Teacher Education and Special Education: The Journal of the Teacher Education Division of the Council for Exceptional Children, 36(4), 298–311. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888406413497485

- Arshavskaya, E. (2017). Becoming a language teacher: Exploring the transformative potential of blogs. System, 69, 15–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2017.08.006

- Benjamin, A. (2002). Differentiated instruction. A guide for middle and high school teachers. Eye on Education.

- Berbaum, K. A. (2009). Initiating differentiated instruction in general education classrooms with inclusion learning support students: A multiple case study [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Walden University.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brevik, L. M., Gunnulfsen, A. E., & Renzulli, J. S. (2018). Student teachers’ practice and experience with differentiated instruction for students with higher learning potential. Teaching and Teacher Education, 71, 34–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.12.003

- Civitillo, S., Denessen, E., & Molenaar, I. (2016). How to see the classroom through the eyes of a teacher: Consistency between perceptions on diversity and differentiation practices. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 16(1), 587–591. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-3802.12190

- Dack, H. (2019). Understanding teacher candidate misconceptions and concerns about differentiated instruction. The Teacher Educator, 54(1), 22–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/08878730.2018.1485802

- DeBaryshe, B. D., Gorecki, D. M., & Mishima-Young, L. N. (2009). Differentiated instruction to support high-risk preschool learners. NHSA Dialog, 12(3), 227–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/15240750903075305

- Dee, A. L. (2010). Preservice teacher application of differentiated instruction. The Teacher Educator, 46(1), 53–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/08878730.2010.529987

- Deunk, M. I., Smale-Jacobse, A. E., de Boer, H., Doolaard, S., & Bosker, R. J. (2018). Effective differentiation practices: A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies on the cognitive effects of differentiation practices in primary education. Educational Research Review, 24, 31–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2018.02.002

- D’Intino, J. S., & Wang, L. (2021). Differentiated instruction: A review of teacher education practices for Canadian pre-service elementary school teachers. Journal of Education for Teaching, 47(5), 668–681. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2021.1951603

- Eskola, J. (2018). Laadullisen tutkimuksen juhannustaiat: Laadullisen aineiston analyysi vaihe vaiheelta. In R. Valli (Ed.), Ikkunoita tutkimusmetodeihin 2. Näkökulmia aloittelevalle tutkijalle tutkimuksen teoreettisiin lähtökohtiin ja analyysimenetelmiin (pp. 209–231). PS-kustannus.

- Evans-Hellman, L. A., & Haney, R. (2017). Differentiation (DI) in higher education (HE): Modeling what we teach with pre-service teachers. Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice, 17(5), 28–38. https://articlegateway.com/index.php/JHETP/article/view/1535

- Fantilli, R. D., & McDougall, D. E. (2009). A study of novice teachers: Challenges and supports in the first years. Teaching and Teacher Education, 25(6), 814–825. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2009.02.021

- Fereday, J., & Muir-Cochrane, E. (2006). Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(1), 80–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500107

- Finnish National Core Curriculum for Basic Education (FNCCBE). (2014). Finnish National Board of Education.

- Finnish National Core Curriculum for General Upper Secondary Education (FNCCGUSE). (2019). Finnish National Board of Education.

- Goodnough, K. (2010). Investigating pre-service science teachers’ developing professional knowledge through the lens of differentiated instruction. Research in Science Education, 40(2), 239–265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-009-9120-6

- Graham, L., de Bruin, K., Lassig, C., & Spandagou, I. (2021). A scoping review of 20 years of research on differentiation: Investigating conceptualisation, characteristics, and methods used. Review of Education, 9(1), 161–198. https://doi.org/10.1002/rev3.3238

- Guskey, T. R., & McTighe, J. (2016). Pre-assessment: Promises and cautions. Educational Leadership, 73(7), 38–43. https://www.ascd.org/el/articles/pre-assessment-promises-and-cautions

- Hall, T. (2002). Differentiated instruction. National Center on Accessing the General Curriculum.

- Hertberg-Davis, H. L., & Brighton, C. M. (2006). Support and sabotage: Principals’ influence on middle school teachers’ responses to differentiation. Journal of Secondary Gifted Education, 17(2), 90–102. https://doi.org/10.4219/jsge-2006-685

- Johnson, K. E., & Golombek, P. R. (2011). The transformative power of narrative in second language teacher education. TESOL Quarterly, 45(3), 486–509. https://doi.org/10.5054/tq.2011.256797

- Joseph, S., Thomas, M., Simonette, G., & Ramsook, L. (2013). The impact of differentiated instruction in a teacher education setting: Successes and challenges. International Journal of Higher Education, 2(3), 28–39. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v2n3p28

- Kivirauma, J., & Ruoho, K. (2007). Excellence through special education? Lessons from the Finnish school reform. International Review of Education, 53(3), 283–302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-007-9044-1

- Krashen, S. D. (1985). The input hypothesis: Issues and implications. Longman.

- Laari, A., Lakkala, S., & Uusiautti, S. (2021). For the whole grade’s common good and based on the student’s own current situation’: Differentiated teaching and the choice of methods among Finnish teachers. Early Child Development and Care, 191(4), 598–611. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2019.1633314

- Lew, M. D. N., & Schmidt, H. G. (2011). Writing to learn: Can reflection journals be used to promote self-reflection and learning? Higher Education Research & Development, 30(4), 519–532. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2010.512627

- Mansfield, C., Beltman, S., & Price, A. (2014). ‘I’m coming back again!’ The resilience process of early career teachers. Teachers and Teaching, 20(5), 547–567. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2014.937958

- McGlynn, K., & Kelly, J. (2017). Using formative assessments to differentiate instruction. Science Scope, 041(04), 22–25. https://doi.org/10.2505/4/ss17_041_04_22

- Murawski, W. W., & Swanson, H. L. (2001). A meta-analysis of co-teaching research. Remedial and Special Education, 22(5), 258–267. https://doi.org/10.1177/074193250102200501

- Murillo, F. J., & Roman, M. (2011). School infrastructure and resources do matter: Analysis of the incidence of school resources on the performance of Latin American students. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 22(1), 29–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2010.543538

- Nepal, S., Walker, S., & Dillon-Wallace, J. (2021). How do Australian pre-service teachers understand differentiated instruction and associated concepts of inclusion and diversity? International Journal of Inclusive Education. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2021.1916111

- Prast, E. J., Van de Weijer-Bergsma, E., Kroesbergen, E. H., & Van Luit, J. E. H. (2015). Readiness-based differentiation in primary school mathematics: Expert recommendations and teacher self-assessment. Frontline Learning Research, 3(2), 90–116. https://doi.org/10.14786/flr.v3i2.163

- Reis, S. M., McCoach, D. B., Little, C. A., Muller, L. M., & Kaniskan, R. B. (2011). The effects of differentiated instruction and enrichment pedagogy on reading achievement in five elementary schools. American Educational Research Journal, 48(2), 462–501. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831210382891

- Reis, S. M., & Renzulli, J. S. (2015). Five dimensions of differentiation. Gifted Education Press Quarterly, 29(3), 2–9. https://gifted.uconn.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/961/2021/12/Five_Dimensions_of_Differntiation.pdf

- Rock, M. L., Gregg, M., Ellis, E., & Gable, R. A. (2008). REACH: A framework for differentiating classroom instruction. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 52(2), 31–47. https://doi.org/10.3200/PSFL.52.2.31-47

- Roiha, A. (2014). Teachers’ views on differentiation in content and language integrated learning (CLIL): Perceptions, practices and challenges. Language and Education, 28(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2012.748061

- Roiha, A., & Polso, J. (2020). How to succeed in differentiation: The Finnish approach. John Catt Educational Ltd.

- Roiha, A., & Polso, J. (2021a). The 5-dimensional model: A Finnish approach to differentiation. In D. L. Banegas, G. Beacon & M. Pérez Berbain (Eds.), International perspectives on diversity in English language teaching (pp. 211–227). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Roiha, A., & Polso, J. (2021b). The 5-dimensional model: A tangible framework for differentiation. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 26,, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.7275/22037164

- Roy, A., Guay, F., & Valois, P. (2013). Teaching to address diverse learning needs: Development and validation of a differentiated instruction scale. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 17(11), 1186–1204. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2012.743604

- Saloviita, T. (2018). How common are inclusive educational practices among Finnish teachers? International Journal of Inclusive Education, 22(5), 560–575. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2017.1390001

- Santangelo, T., & Tomlinson, C. A. (2012). Teacher educators’ perceptions and use of differentiated instruction practices: An exploratory investigation. Action in Teacher Education, 34(4), 309–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/01626620.2012.717032

- Seppälä, R., & Kautto-Knape, E. (2009). Eriyttämisen tavat englannin opetuksessa. Kielikukko, 4, 13–18.

- Shaunessy-Dedrick, E., Evans, L., Ferron, J., & Lindo, M. (2015). Effects of differentiated reading on elementary students’ reading comprehension and attitudes toward reading. Gifted Child Quarterly, 59(2), 91–107. https://doi.org/10.1177/0016986214568718

- Smets, W. (2017). High quality differentiated instruction: A checklist for teacher professional development on handling differences in the general education classroom. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 5(11), 2074–2080. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2017.051124

- Thousand, J. S., Villa, R. A., & Nevin, A. I. (2006). The many faces of collaborative planning and teaching. Theory into Practice, 45(3), 239–248. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4503_6

- Tirri, K. (2014). The last 40 years in Finnish teacher education. Journal of Education for Teaching, 40(5), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2014.956545

- Tomlinson, C. A. (2014). The differentiated classroom. Responding to the needs of all learners (2nd ed.). ASCD.

- Tomlinson, C. A., Callahan, C. M., Tomchin, E. M., Eiss, N., Imbeau, M., & Landrum, M. (1997). Becoming architects of communities of learning: Addressing academic diversity in contemporary classrooms. Exceptional Children, 63(2), 269–282. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440299706300210

- Tomlinson, C. A., & Eidson, C. C. (2003). Differentiation in practice. A resource guide for differentiating curriculum, grades 5–9 ASCD.

- Tomlinson, C. A., & Imbeau, M. (2010). Leading and managing a differentiated classroom. ASCD.

- van Geel, M., Keuning, T., Frèrejean, J., Dolmans, D., van Merriënboer, J., & Visscher, A. J. (2019). Capturing the complexity of differentiated instruction. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 30(1), 51–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2018.1539013

- VanTassel-Baska, J., & Stambaugh, T. (2005). Challenges and possibilities for serving gifted learners in the regular classroom. Theory into Practice, 44(3), 211–217. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4403_5

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. (M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner & E. Souberman, Ed. & Trans.). Harvard University Press.

- Wan, S. W. Y. (2016). Differentiated instruction: Are Hong Kong in-service teachers ready? Teachers and Teaching, 23(3), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2016.1204289

- Yeager, D. S., & Walton, G. M. (2011). Social-psychological interventions in education: They’re not magic. Review of Educational Research, 81(2), 267–301. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654311405999