ABSTRACT

This article explores live–work housing conditions for low-income older residents in an informal settlement in Bangkok called Klong Toey (KT) via interviews with 12 participants. The aim is to understand the housing and livelihood situation of older low-income inhabitants of KT, to assess the suitability of their physical environment and areas that could be improved to enable it to serve as live–work housing and to facilitate aging in place, and to inform future work. Participants were asked about the housing conditions in KT and their impact on residents; types of housing for older people in KT; design guidelines for live–work housing; and any lessons from other low-income housing projects. The study used content analysis to examine the interview transcripts. Four organizing themes were used to analyze the responses: housing conditions and relation to live–work; situation and requirements of older people’s housing; live–work housing design guidelines; and solutions to older people’s live–work housing. Finally, four global conceptual domains of live–work housing were constructed from mapping the basic themes. The global conceptual domains include “space,” “livelihood,” “support,” and “services” that are essential to the provision of live–work housing in KT.

Introduction

The aim of this study is to explore the live–work housing conditions of low-income older people in Klong Toey (KT), Bangkok, Thailand. Housing and livelihood constitute fundamental human needs; the cumulative effect of the dysfunction of these aspects of human lives disproportionately affects vulnerable groups such as older people in lower- and middle-income countries. live–work housing is a dwelling type that simultaneously accommodates living and livelihood activities (Durosaiye et al., Citation2022). In the context of this research and, more broadly, in the Global South, live–work housing is an emerging phenomenon in contemporary global housing debates. Whereas live–work housing is as an old form of habitat, it is not until the turn of the millennium that a consensual name has been ascribed to this long-standing human practice, to situate housing and work under one shelter (Dolan, Citation2012). Hence, it is little wonder that until recently there has been a dearth of research into live–work housing, as researchers, practitioners, and policymakers have used a myriad of terms to describe the co-existence of home and work within the same environment. According to Holliss (Citation2015), the existence of live–work housing centuries ago can be traced to the varying nomenclatures by which it was known in various parts of the world. For instance, in Japan it is known as “machiya” and described as dwellings where shopkeepers (individuals dealing with retail trade) and merchants (individuals or a company dealing in wholesale trade) lived and worked together. In Malaysia, it is referred to as the “shop house:” two-story mixed-use dwellings used for business activities on the ground floor and as residences on the upper floor (Mohit & Iyanda, Citation2016). Additionally, in Vietnam it is known as the “tube house:” a two-story rectangular building with a small frontage (2–4 meters) but significant depth (20–60 meters). The front areas on the ground floor are used as shops, while the other parts of the buildings serve as residences (Nguyen et al., Citation2016). However, the conscious attempt at assembling living and livelihood activities under a single unit differentiates contemporary live–work developments in the Global North from their earlier models in the Global South, where the combination of living and working arrangements under a single accommodation unit was incidental, and a matter of necessity (Kakal, Citation2010). Holliss (Citation2015) argues that while these workhome settings primarily respond to culture and climate, they “are often so familiar that they are no longer noticed” (Holliss, Citation2015, p. 6).

Additionally, necessity is still the major driver of live–work housing in the Global South today, and it often manifests as informal settlements, where live–work housing is perceived as a means to accommodate low-income vulnerable groups, while supporting their livelihood needs (Uyttebrouck et al., Citation2021). live–work housing in the context of this study refers to home-based enterprises, especially in low-income populations in Global South countries.

Background and context

The impetus to undertake this research derives from its implication for low-income older people in Global South countries. By addressing the housing insecurity and livelihood problems of low-income older residents in KT, this research responds to structural inequalities entrenched in the area’s informal settlements, recognizing that global challenges are often multi-dimensional, involving various stakeholders with diverse and, often, conflicting interests.

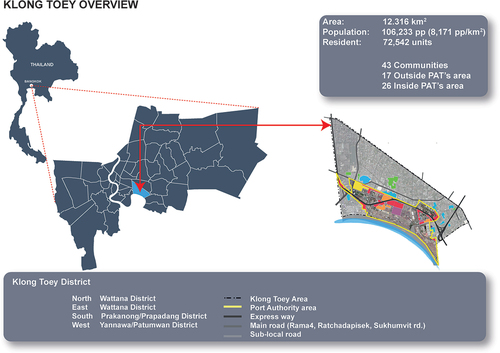

KT is the largest informal settlement in Bangkok and dates to 1939 when it was formed by dock laborers working for the Port of Thailand (Albright et al., Citation2011; Menon & Melendez, Citation2009). Atitruangsiri et al. (Citation2017) established that KT consists of 26 sub-communities over an area of 1.5 square kilometers on land belonging to the Port Authority of Thailand (PAT) (see ). KT is located close to a major shipping port, and this made it a viable settlement for low-income groups seeking job opportunities with PAT (Garabedian et al., Citation2006), with such groups building homes illegally on the PAT-owned land (Boonyabancha, Citation2005). The population of KT has grown to more than 100,000 people, mostly consisting of immigrants from the countryside and neighboring countries (Garabedian et al., Citation2006). According to Boonyabancha (Citation2005), because of a constant threat of eviction from PAT, KT residents have been reluctant to invest in developing their houses and community properly, leaving the settlement in a dilapidated state.

Despite attempts over the years to evict the residents to allow for the expansion of the port’s facilities, the population kept growing, and a strong community organization, supported by voluntary agencies, started opposing eviction attempts around 1973. Over the decades, residents of KT have created housing and livelihood solutions for themselves, which have complicated rehousing proposals by authorities. However, Archer (Citation2010) acknowledged that while previous government responses to low-income groups’ housing problems in Thailand had been suboptimal, recent efforts have targeted participatory slum upgrade projects with the aim of providing secure housing for low-income groups. Slum upgrading program in Thailand known as Baan Mankong (“Secure Housing”) started in 2003 and have used community participation to address secure tenure (Archer, Citation2012), and provided community welfare funds as grants or loans to older people for example with support from the World Bank Social Investment Fund (Boonyabancha, Citation2005). In fact, Thai government’s attempts to clear slums and to address urban housing problems started in the 1950s with mixed results (Giles, Citation2003). The Baan Mankong program was known for its “community-driven approach” which led to effective collaboration between residents and government and non-government agencies such as CODI (the Community Organizations Development Institute in Thailand) and the National Housing Authority (NHA) (Boonyabancha & Kerr, Citation2018; Tonmitr & Ogura, Citation2014). However, several factors combined to slow down the program across Thailand, with less than half planned projects in 400 cities completed in 2018 (Boonyabancha & Kerr, Citation2018). Additionally, feedback received from residents of KT on the Baan Mankong suggests that they were not satisfied with the community environment highlighting communal living issues (Archer, Citation2012). This study contributes to this debate by exploring live–work housing conditions for low-income older residents in KT through qualitative research.

The importance of live–work housing to older people

Access to decent housing for low-income populations is a considerable challenge in the developing world. UN-HABITAT (Citation2016) estimates that close to 30% of urban dwellers in low-income countries live in slums or poor-quality housing. Habitat for Humanity (Citation2023) also estimates that by 2030 this will still be the case, with one in three dwellers living in slums in the developing world.

Access to basic amenities and sustainable livelihood opportunities for these population groups is an even bigger challenge. This situation is further exacerbated for vulnerable groups such as older people, women, or those suffering from mobility, sensory, or cognitive impairments. Low-income older urban dwellers are also affected by emerging demographic and socio-economic trends that are influenced by an aging population and the live–work needs of these dwellers, such as the desire to age in place and to maintain a sustainable livelihood (Durosaiye et al., Citation2022).

By 2050, Asia is on course to become the oldest continent in the world, accounting for 62% of the global older population (Menon & Melendez, Citation2009). This is a significant challenge that will also affect Thailand, which is experiencing growth in the number of people aged 60 and over. This population was estimated to be about 19% in 2020 and is expected to grow to 32% over the next two decades (Ruengtam, Citation2020). By 2030, the population over 60 years old will be larger than that of those under the age of 15 (Knodel & Chayovan, Citation2008). This unprecedented demographic change is also affecting low-income families living in informal settlements in Bangkok and elsewhere in Thailand. Low-income groups in the Global South often exhibit intersectional vulnerability, most notably in that they often belong to the older age groups as well. They also rely on live–work housing in the form of home-based enterprises. These play a vital role in income generation and are crucial to poverty alleviation at the household level, especially for women and older people, by affording them a level of financial independence which would otherwise be difficult to achieve (Gough et al., Citation2003). Home-based trade is in homes or around an owner’s dwelling and relies on personal or domestic assets with the potential of transitioning from a survivalist function to an enterprise. This occurs within a hierarchical space that includes a home, the immediate street located around the home, the broader neighborhood, and surrounding public urban spaces (Ghafur, Citation2001).

However, live–work housing in the Global South remains unpopular with planning and regulatory authorities regarding building control, land use, and issues of employment conditions, because these developments are perceived by local authorities and policymakers as conducive to poor working conditions (Gough et al., Citation2003). Nonetheless, live–work dwellings, also known as home-based enterprises in the Global South, provide job opportunities, particularly to the aging population and women, and are a source of income security.

The widespread development of home-based enterprises has led to growing calls urging policymakers, city planners, housing providers, and other allied built environment professionals to recognize the significant role live–work housing plays in the development of home-based enterprises, especially in low-income populations in Global South countries (Lawanson & Olanrewaju, Citation2012; Tipple, Citation2006).

It is in considering such calls that this study, through interviews with stakeholders, attempts to explore the concept of live–work housing solutions for low-income groups in Klong Toey, Bangkok, who depend on their housing for their livelihood.

Methodology

Semi-structured interviews were used as a data collection tool. Interviews with 12 participants, who include three older low-income residents, five community and non-governmental organizations, three policymakers, and one housing provider, were used in this research. This was done to gain an understanding from many perspectives of the housing and livelihood situation of older low-income inhabitants of KT, and to assess the suitability of their physical environment and the areas of improvement that will enable it to serve as live–work housing. The overall aim of this exploratory study is to raise research questions and identify key themes to inform future work. Our study was built on this premise, by selecting participants based on their involvement in the research project and their knowledge of KT history and current challenges. To gain a comprehensive understanding of the issues, the study interviewed a wide range of stakeholders involved in provision, use and management of live–work housing in KT. The profile of the participants is presented in .

Table 1. Profile of interview participants.

Participants were asked the following questions:

What do you think of the housing conditions in Klong Toey? Do they promote or reduce living and working conditions of the residents?

How should the housing for low-income older people in Klong Toey be?

What are the design guidelines for live–work housing for low-income people in Klong Toey, particularly for older people?

What lessons have you learned from previous works or projects in Klong Toey regarding low-income housing?

Interviews were conducted in Thai then transcribed in the same language. The transcription was then translated into English for content analysis and coding. The English translation was completed and cross-checked by three Thai researchers, then checked again by three UK-based researchers for accuracy and intelligibility. This process was adopted to remove methodological bias during the processing of data. All six researchers are coauthors of this article.

The study used content analysis to examine the interview transcripts. According to Hsieh and Shannon (Citation2005), p. 1278), content analysis is used in examining textual data by focusing “on the characteristics of language as communication with attention to the context or contextual meaning of the text.” In applying content analysis, Rourke et al. (Citation2001) established the existence of five types of units from which a researcher can select. One of those units which this study adopts is the thematic unit, which is also referred to as a unit of meaning. This is one of the most common units used in content analysis (Rourke et al., Citation2001). According to Chi (Citation1997), p. 46), in content analysis, a unit of meaning refers to “an idea, argument chain or discussion topic.” Thus, the data analysis was conducted through coding of the data to generate themes. The coding adopted the strategy of inductive content analysis used by Elo and Kyngäs (Citation2008), p. 109), which included “open coding, creating categories and abstraction.”

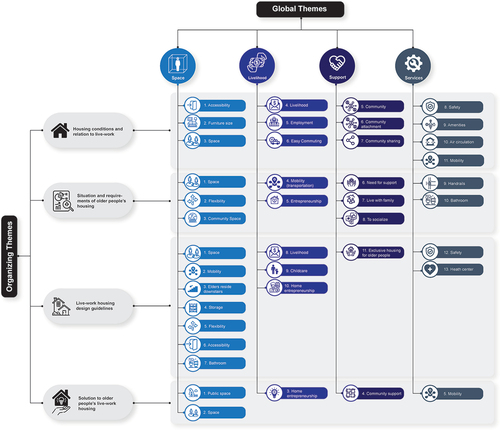

For the analysis, the interview transcripts were examined to generate themes. This was performed by two authors prior to coding with NVivo 11 software. The themes generated were transferred to a coding sheet to create categories. In line with Attride Stirling (Citation2001), the study developed organizing themes, basic themes, and global themes. The four organizing themes were drawn from the question schedule used in the interview:

Housing conditions and relation to live–work.

Situation and requirements of older people’s housing.

live–work housing design guidelines.

Solution to older people’s live–work housing.

These four themes were used to structure the data analysis by discussing their constituent basic themes and to help construct the global conceptual domains. The mapping of the basic themes according to how they feature and the concepts they underscored in the data analysis identified four global conceptual domains of live–work housing: space, livelihood, support and services. ()

Table 2. Global themes, organizing themes and basic themes.

Data analysis

The matrix query in NVivo 11 software was used to highlight the frequency of how a response corresponds to the main theme. The analysis followed the thematic network approach proposed by Attride Stirling (Citation2001), p. 388), which is a form of theme organization in a structure.

The next section presents the analysis of the responses from participants based on the organizing themes. The findings from the thematic analysis which will be discussed in the next sections can be summarized in the following table.

Housing conditions and relation to live–work

Under this, 13 basic themes were identified to have generated the highest number of frequencies (). These are “mobility,” “accessibility,” “poor air circulation,” “poor livelihood,” “lack of space,” “furniture size,” “safety,” “sharing community,” “community attachment,” “community service,” “easy commuting,” “attractive employment,” and “poor amenities” – all of which emerged when describing the housing conditions and its relation to live–work in KT.

The basic themes of “mobility” and “accessibility” underscore the various challenges associated with accessibility, which are also integral components of a dwelling. An example indicates that in some cases, bathrooms are constructed outdoors, away from the dwelling unit, and this fails to consider the convenience of older people and the sick. Additionally, because of the way the settlement is designed, most inhabitants are forced to convert part of the dwelling to a storage or trade area.

Furthermore, from the responses, the basic themes share a direct relationship. For instance, in discussions of accessibility problems, there were issues associated with mobility of the older occupants in their dwellings. As an example, in highlighting their housing conditions, a participant from one of the community organizations suggested that:

When there’s a patient and they have to transport the person, getting the stretcher in is difficult, because the door is narrow and hard to get in. – P10

Similarly, the basic themes “furniture size” and “lack of space” are related to participants stressing how, due to limited dwelling spaces and partly because of large pieces of home furniture, creating workspace for trade is difficult. This is attributed to an inability to find suitable furniture to fit into the limited dwelling spaces. To illustrate this, a resident participant noted:

The furniture they sell in Thailand are usually the same sample sizes; therefore, the main issue relates to limited space and cheap furniture that takes too much space … when the beds are installed, there is no room left. – P12

Another recurring basic theme is “poor livelihood,” which emphasizes the economic conditions of most of the people living in KT. This, the participants argue, has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has caused even more hardship. Participants who live in KT suggest that their poor livelihood situation is aggravated by poor living conditions which leave large families occupying small rooms of about 28 square meters. Furthermore, a participant from a charity who agrees with this said:

If you are asking if it is good to live here, the answer is – it does not provide a good quality of life. – P2

It is noteworthy that the basic theme “poor livelihood” emerged in discussions that reiterate the unique appeal of KT to new settlers as an economically attractive settlement. Linking KT’s poor livelihood with its attraction to employment, a resident contends that:

The area around Klong Toey where it is residential might not have a good quality of life, but it is the location that caters to jobs and income. – P7

Another basic theme linked to employment attraction is “community attachment,” where a few participants pointed out that inhabitants of the settlements are often attached to the community because it is near places of economic opportunities. Emphasizing this link, a housing provider with at least 20 years’ experience in housing design for KT communities said:

I talked to them about moving somewhere else … they told me that some people moved out. But in the end, they could not live there (in their new place) and had to move back. When they moved out, they could not find jobs or could not make a living and there was no connection at all. – P5

This statement provides some level of veracity to other claims such as by Archer (Citation2012) about the significance of community cohesion in KT. There is a concession among stakeholders which suggests that even when people are provided with housing alternatives, usually of better quality, but nonetheless detached from their means of livelihood, they tend to lose their economic viability in this new setting. This also means that a new livelihood could not be created as quickly as new housing. This perception suggests that their attachment to the KT community does not just derive from their emotional and familiarity needs, but cuts through their existential needs as well, despite the poor state of infrastructure in KT, such as its water system and inadequate waste disposal.

Situation and requirements of older people’s housing

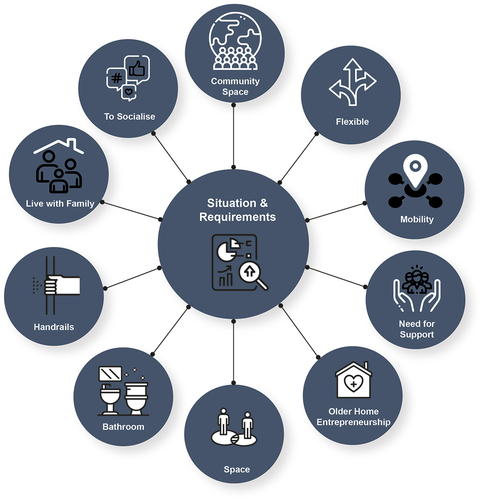

An insight into the situation and requirements of older people’s housing in KT is central to understanding their current housing situation and using this knowledge to plan a settlement that is conducive to sustainable aging in place. This organizing theme generated 10 basic themes: “community space,” “older home entrepreneurship,” “flexibility,” “mobility,” “need for support,” “space,” “bathroom,” “handrails,” “live with family,” and “to socialize” ().

While some of these themes emerged in discussions on the housing situation of the older residents, others emerged to suggest these are key requirements for aging in place. Additionally, a few of these appeared when discussing both. For instance, the themes “space,” “mobility,” “need for support,” and “older home entrepreneurship” were also highlighted under the housing situation and requirements of older people’s housing. This organizing theme also features the themes “bathrooms” and “handrails,” highlighted in both this theme and the housing situation. This evokes the inadequacy currently in the older people’s housing situation, suggesting that there could be a need for either the provision of new housing or the improvement of existing older housing. As a reminder, the themes “mobility” and “older home entrepreneurship” were also emphasized when discussing the housing conditions and relation to live–work organizing theme.

The basic themes “to socialize” and “community space” were raised by participants to emphasize the community requirements for aging in place. This is also evident in participants’ claim that there is the need to provide spaces for socializing:

There should be a common area and a space that they could engage (in) activities together, maybe catching up and updating … or talk(ing) about their careers together. – P6

The perception is that the ability of older people to socialize aids aging in place and reduces the feelings of loneliness suffered by some of the older residents, some of whom are living alone. Participants suggested this could be achieved by providing “community space” for these interactions. Thus, additional requirements regarding spaces, as part of the resettlement planning, should make provision for community spaces that could be used by the community in general and the older residents in particular. In arguing for the need of this, a participant noted:

What I really want to see is there should be a shared space provided consisting of a career space to make a living and the recreational space for the community within the shared space. – P2

This community space, or common space, as referred to by the participants, serves the dual purpose of being a recreational space for use by the community. Furthermore, participants argued that there is a need to plan for a living arrangement that allows older residents to live with their families. This was echoed by an older resident, who said:

They still want to live with a proper family. We have to think about how the older people and their children would live together. – P7

On this, however, there were some dissenting voices, who suggested planning separate dwellings for the older residents in flats and allowing the children and grandchildren to visit from time to time. This would be like arrangements made in care homes, which is common in the Global North.

live–work housing design guidelines

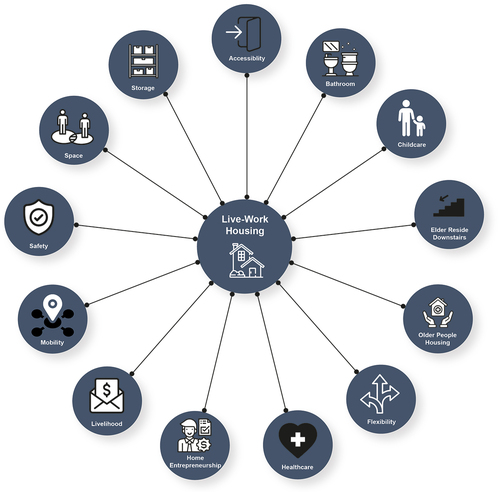

Under this organizing theme, 13 basic themes emerged. These are “space,” “mobility,” “elders reside downstairs,” “flexibility,” “accessibility,” “livelihood,” “safety,” “home entrepreneurship,” “storage,” “childcare,” “health center,” “bathroom,” and “exclusive housing for older people” ().

In discussions on space, three basic themes were linked to this: the provision of adequate “dwelling spaces,” “working spaces” and “shared spaces.” Highlighting the need for adequate spaces, participants argue that design provisions should consider furniture spaces and an inhabitant’s working area within a dwelling to overcome current problems of limited circulation spaces in the dwellings. In terms of the working spaces, there were suggestions that adjusting the overall circulation spaces in a dwelling would allow for the creation of a working space which could be used by inhabitants for home entrepreneurship activities. This would allow multiple inhabitants in different trades to operate within the same space. Furthermore, the need for shared spaces for older inhabitants was suggested, to allow them to interact with each other more often, as this supports aging in place. This was highlighted by one participant in particular:

Another important thing is there should have been a shared space provided for the community to do activities together. – P2

Further, the basic theme “livelihood” was related to the provision of space in general, and specifically working space. Discussions on livelihood focused on the provision of a dwelling type that can support an older person to live and work in the same place. For instance, P1, a social worker, vaguely argued for a primary design requirement:

… just a proper housing for elders which is safe and able to accommodate a small business or selling, just enough to earn a living and feed the family. – P1

The case for space is strengthened by arguments that in most cases current living arrangements do not provide sufficient storage for inhabitants, and this contributes to cramping up of dwellings, since the same space is used for living, business, and storage. Participant P9, who is a researcher in housing delivery, shed more light on the need for storage space by arguing that:

They need lots of space at the ground floor. They need extra storage for their tools. There should be space for them to store their tools for their business. – P9

The need for independence as a fundamental feature of aging in place is echoed by participants, who suggested this would be reflected in a good live–work dwelling arrangement. A good living arrangement allows an inhabitant to live safely, be able to take care of themselves, and be able to move within their dwelling with the provision of support facilities like handrails and ramps for wheelchair users. Furthermore, participants highlighted that a good live–work dwelling would allow older residents to be involved not only in home entrepreneurship but also in assisting with childcare while earning a living. This is highlighted by a participant who said:

A lot of elders with proper dwelling can take care of their grandchildren and be involved in selling stuff like sodas or confectionery. So, they can take care of their grandchildren and earn an income. – P1

As stressed when discussing the housing situation and condition of older people’s housing, factors related to two basic themes were raised during discussion about the adequacy of space in the dwellings: “mobility” and “accessibility.” The link between mobility and accessibility is reiterated in this suggestion by a participant:

Perhaps, they could be buildings spread out and connected by overhead walkways or underground passages within the project which promotes mobility within the area without the need for using a personal car. – P8

In general, participants argued that as a person gets older, mobility problems emerge, and this is likely to impede accessibility, especially when a dwelling is cramped. Thus, the link between mobility, accessibility, and space adequacy was emphasized by participants who suggested that designing dwellings with adequate spaces allows inhabitants to easily move around, and this helps even those with mobility problems.

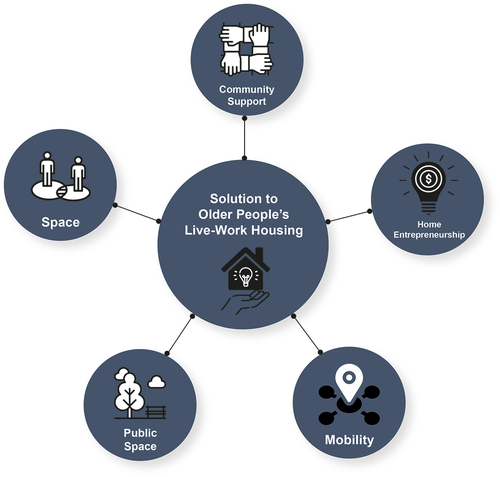

Solution to older people’s live–work housing

Five basic themes emerged from discussions on solutions to older people’s live–work housing arrangement. These are “home entrepreneurship,” “mobility,” “public space,” “community support,” and “space” (). The need for a dwelling and public spaces was raised many times by participants, as well as the need for support. In discussing the need for public spaces, participants specifically highlighted the need for community spaces, arguing that despite the size of KT, there are no planned parks and playgrounds for children, or places older residents could use for walking and exercise. They claimed that such spaces avail people living around such areas the opportunity to relax and unwind together, and that provision of such spaces improves the quality of life of older residents as well as the children living in those areas. Emphasizing the importance of communal spaces in KT, a resident participant noted that:

Klong Toey is a crowded community with low-income families, not very much living space, and a lot of people living in it without much communal space to walk around and exercise. – P7

Participants emphasized the huge importance attached to space and reiterated the need for adequate dwelling spaces within a proper live–work arrangement. They stressed that current arrangements often offer living spaces only, without any provision for activities related to trade or livelihood and with no access to green space for the residents. Additionally, linked with trading spaces is the basic theme “home entrepreneurship,” which participants suggested enables an older person to earn a decent living in or around their dwelling if this is professionally designed to allow for aging in place. Furthermore, the theme “community support” emerged, with participants calling for a better support structure for older residents in KT, suggesting that this could be strengthened through community programs and advocacy. As an example, such programs could include the provision of a rehabilitation center where older residents could access physical therapy sessions as suggested by a participant:

We want to see a strong community where we can take care of the elders in the community. This will include the provision of a rehabilitation center and nurses for elders. – P2

Participants argue that through community support, socializing among residents will increase and incidents of isolation among older residents will undoubtedly reduce. Additionally, the theme “mobility,” as highlighted in previous conversations on live–work design, also emerged in debate over proper live–work arrangements. In this instance, it was mentioned by the participants regarding facilities required in properly constructed live–work dwellings. They claimed that fittings such as handrails, ramps, and adequate lighting were vital components of a live–work dwelling. For instance, stressing the need for handrails, a participant said:

We would need handrails or some design that is suitable for us. We must prepare in case we cannot walk. In bathrooms, there should be handrails. – P3

One participant suggested that overall, a participatory approach is required for maximum impact, although they argued that providing a solution through such a process may require time and patience to allow the residents to gain confidence and understanding of the projects’ objectives and importance, and the potential benefits arising from them.

Next, the global conceptual domains emerging from this analysis will be discussed. “Global” in this context means universal or comprehensive.

Global conceptual domains

The second stage of the data analysis aims to construct the global conceptual domains from the analysis of the basic themes. Four global conceptual domains of live–work housing emerged by mapping the basic themes according to how they feature and the concepts they underscored in the data (). The global conceptual domains include “space,” “livelihood,” “support,” and “services” that are essential to the provision of live–work housing for older people in KT (). The following sections explore how these domains of live–work housing can support aging in place in Bangkok, Thailand.

Figure 6. Global conceptual domains of live–work housing to support aging in place in Bangkok, Thailand.

Space

The notion of “space” centers on themes related to the provision and allocation of spaces for living and working purposes in a live–work arrangement. Topics related to space include accessibility, furniture size, lack of space, and mobility. Additional topics include community space, flexibility, elders reside downstairs, public space, and storage. It is noteworthy that while themes related to outdoor spaces were highlighted, discussions by participants about spaces were broadly concerned with dwelling arrangements that would promote live–work.

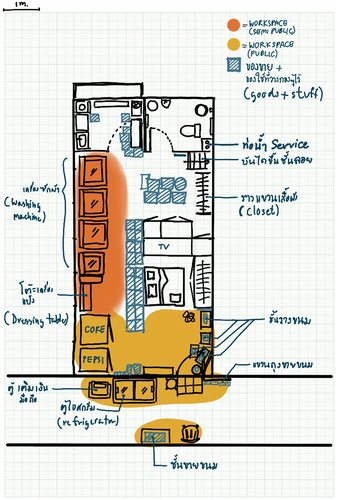

To shed more light on space arrangement, Holliss (Citation2015) argues that the spatial organization of live–work dwellings is determined by four factors. First is the nature of an inhabitant’s occupation or business and their socio-economic relationships. Second is the family context; this deals with variables such as family size, culture, social norms, and social roles. Third is that the available space determines the extent of possibilities for the spatial organization. Fourth is the personality of the individual who is conducting the business. These factors combine to create each household’s unique live–work arrangement. In the case of KT, the nature of people’s businesses in the settlement creates problems related to adequacy of shared and communal spaces. The family context affects space adequacy, and this is highlighted in the problem of furniture sizes that participants argue limits live–work arrangements. Additionally, family sizes determine certain living arrangements, with the lower floors usually reserved for older residents. Family size also influences storage space, which in turn affects live–work arrangements.

Other authors have also discussed the importance of space allocation in live–work housing arrangements (Friedman, Citation2012; Gough et al., Citation2003; Holliss, Citation2015; Poldma, Citation2008). For instance, Gough et al. (Citation2003) noted that a lack of adequate space is one of the key problems associated with live–work housing, which also limits the possibilities for expansion. Poldma (Citation2008), on the other hand, contends that interior spaces within a dwelling are often created as a cultural symbol or for the aesthetic contentment of the inhabitant, rather than as a response to an occupant’s actual needs.

Participants observed that most of the dwellings are cramped because of inadequate spaces, and this contributes to increases in problems related to access and mobility. Friedman (Citation2012) agrees with this and argues that in situations where a dwelling has minimal floor space, the integration of elements like movable partitions provides the option for extending or reducing the business spaces, subject to its inhabitants’ needs. However, in this case, a challenge to solving the problem associated with space may be related to the absence of regulatory guidance on minimum space standards and allocation, since KT is an informal settlement. Gough et al. (Citation2003) strengthen this argument with a study on home-based enterprises in developing countries, which established that comprehensive formal regulation on operation is usually limited. Gough et al. (Citation2003), p. 268) argue that the operation of home-based enterprises is limited, with the existence of “a wide range of informal regulatory mechanisms” dictating how space is used.

Additionally, participants in this study used the basic theme “flexibility” when discussing the limited dwelling spaces and overcrowding (). Nadim (Citation2016) argues that the relationship between flexibility and the concept of spaces in live–work dwellings emanates from the need for occupants to alter or amend their floor layouts. Reasons for this may include the need to accommodate more people, household composition changes, and the desire to introduce a new business venture.

There were discussions on the need for fittings to support aging in place, such as the need for handrails that are suitable for older people and can assist people with reduced mobility. There were suggestions that such fittings should also be provided in bathrooms to help with safe movement. Additional requirements suggested include ramped walkways with handrails, wheelchair accessible elevators, adequate light, and appliances for everyday use. For aging in place, Friedman (Citation2012) suggests that the introduction of barrier-free designs enables the creation of spaces that ease tasks for people with reduced mobility.

Livelihood

Moser (Citation2008) established that housing itself is a physical asset for low-income groups that could function in various forms, including as an avenue for the creation of a range of livelihood opportunities which low-income groups could use to maximize livelihood outcomes. In exploring live–work arrangements in KT, inhabitants’ means of livelihood dominated discussion. A key feature of KT that emerged from the interviews was its attractiveness. Its location makes it appealing to low-income groups because it is “attractive employment” and “commuting is easy” for inhabitants. This may well be due to its location on PAT land and its proximity to other ancillary businesses (Albright et al., Citation2011). Although agreeing with such claims, Garabedian et al. (Citation2006) established that while the viability of KT was mainly due to availability of work through the ports, in recent years, privatization and mechanization have considerably reduced the job opportunities for these low-income groups, who are also often low skilled, and this is subjecting them to major eviction threats from PAT.

Furthermore, settlers’ attraction to KT may also be because the settlement enables them to engage in entrepreneurial activities that bring goods and services closer to its inhabitants and at prices they can afford. Ezeadichie (Citation2012) argues that home-based entrepreneurships in developing countries serve the needs of low-income groups because they are often available, accessible and affordable. Entrepreneurs provide essential services within such communities, and consumers find them affordable, since they eliminate the need to invest time and money in traveling to other neighborhoods for the required goods and services.

The participants identified voluntary “childcare” duties and “older home entrepreneurship” as activities common among older people in KT. Childcare often is unpaid and involves grandparents looking after their grandchildren while the parents go to work, so they also set up home entrepreneurships, targeting KT residents. These businesses, which include services like salons and catering, provide informal income for the older residents and services to the KT community. This agrees with a study by Assatarakul (Citation2015) on the socio-economic activities of older people in Thailand, which engaged more than 16,000 older participants (aged 60 years and over). This established that up to 80% of the older population engage in at least one of three activities: childcare (caregiving service to family members); providing community service; or conducting a form of home entrepreneurship to help improve their livelihood.

Another major contributory factor to the poor living conditions and livelihood conditions is related to space limitations (on average about 28 square meters). Participants argue that this creates a low standard of living, with potential negative health impacts.

Participants also highlighted the absence of infrastructure and argue that provision of such basic amenities would help to develop the community in diverse ways, perhaps leading to social amenities such as marketplaces, offices, hospitals, community centers, and education centers. Furthermore, the arrival of such amenities would give people living in KT more diverse job opportunities in sales and services and encourage other businesses to expand. Kigochie (Citation2001) agrees with this, noting that most governments in developing countries do not encourage home-based enterprises because they are mostly found in the informal sector. Most often they are created in isolated locations, which makes growing a business difficult. However, there are indications that the provision of requisite infrastructure, such as transportation, could offer these informal settlements the potential to compete with the formal sector in revenue generation (Kigochie, Citation2001).

With regard to the potential of live–work housing to provide a sustainable means of livelihood for low-income groups, Gough et al. (Citation2003) contend that home-based enterprises are crucial to income generation in developing countries and play a vital role in alleviating poverty at individual and household levels. Specifically, they provide opportunities for vulnerable groups like women and older people. For instance, they serve as an earning mainstay for women who combine productive and caring roles in their dwellings. Additionally, for older people, home-based entrepreneurships contribute economically and socially by providing the opportunity to retain self-esteem and independence.

Support

The concept of support as discussed in the study includes “community support,” “community service,” “sharing community,” “need for support,” “live with family,” and “to socialize.” The majority of these are related to tasks conducted either by younger individuals to assist older people or by the older people themselves to promote aging in place. These younger individuals are either family members or members of the community support groups from KT. Jitramontree et al. (Citation2011) discussed the community support groups in Bangkok low-income settlements, including KT, which provide voluntary services to older people. This includes small, easily accessible healthcare services from community volunteers who are knowledgeable in healthcare. Community support services conducted by either active older care volunteers or younger individuals ensure that older people regularly interact with community members and are not living in isolation. The crux of the argument raised by participants suggests that aging in place must be properly supported through the provision of community support. According to Friedman (Citation2012), aging in place is an approach which creates dwellings and communities to support mature people’s needs as they grow older. This approach of adapting the dwelling to the changing needs of older people also ensures independent and secure living, which in turn provides them with a better quality of life. Economically, aging in place provides financial sustainability by avoiding or delaying the need for families or the state to provide new or costly adjustments to living arrangements for older people.

Furthermore, Allen and Wiles (Citation2013) argue that the term “support” for older people could suggest either being dependent or a tool to maintain an independent lifestyle despite aging. In this study, participants refer to the term in the context of both definitions. Its reference to being dependent is underscored in the themes “exclusive housing for older people” and “live with family,” with both highlighting the older inhabitant becoming dependent on either family or professional care to maintain a decent quality of life. On the other hand, the basic themes “to socialize” and “community service” were used by participants to emphasize the importance of these factors to older residents wishing to “age in place” while maintaining their independent lifestyles. They argue that these activities involve older people in the community and help to eliminate the incidence of loneliness and isolation suffered by some older people, especially those living alone.

Jitramontree et al. (Citation2011) established that KT was among the communities in Bangkok with effective social services that include a good community support structure for older residents, and this is attributed to active leadership and effective teamwork.

Services

Services is the fourth global conceptual domain to the live–work housing requirements in KT. Under this, discussions by participants cover “poor state of amenities,” “handrail” fittings for aging in place and “poor air circulation.” Other basic themes associated with services are “mobility,” “safety,” “bathroom,” and “health center.” The poor state of infrastructure provision in KT may not be unconnected to tenure insecurity experienced by its households. Since the land on which the settlement is located belongs to PAT, the inability to improve the settlement’s infrastructure may serve to discourage its further growth.

The issue of safety was viewed by participants on two fronts: crimes and drugs within the community, and protection of dwellings from the outbreak of fire. Discussions regarding fire incidents revealed that households are not allowed to use gas for cooking in their dwellings, which they contend is argued as a safety measure by the authorities. Instead, they are only allowed to use electric stoves. However, because the cost of gas is cheaper, households defy this and use gas stoves, which in the past has led to fire incidents. As such, participants call for better planning guidelines by authorities that could allow households to use a cheaper energy source while eliminating potential fire hazards. As an additional safety measure, fire and smoke alarms should be provided in dwelling units to notify households of fire incidences. Furthermore, participants established that due to the composition of the inhabitants of KT, antisocial behavior, such as drug abuse and other crimes, is prevalent. They explained the impact of these on their children, especially since KT is a crowded community of low-income families with limited living and recreational space. Finally, participants also highlighted the need for adequate amenities such as a health center nearby for residents and older people in particular.

Conclusion

Since KT is the largest informal settlement in Bangkok, with more than 100,000 people, adequate housing is a prominent problem for its inhabitants. This is compounded by tenure insecurity and a recurring threat of eviction. However, through community organizations, the residents of KT continue to be engaged in creating housing and livelihood solutions for themselves in situ. Seeking to find solutions, this study explored the live–work housing conditions of older low-income residents of the KT community. It argues that developing effective housing for older residents serving as both a dwelling and a means of livelihood is integral to their economic prosperity and ability to age in place. Through interviews with 12 participants represented by community organizations, housing providers, policymakers, and older KT residents, this study collected data on four topics which explored the live–work housing conditions of older residents.

The first topic assessed the housing conditions and their relation to the live–work housing arrangements of KT residents. Second, the housing situation and requirements of older residents were discussed. The third and fourth areas offered to promote live–work housing design guidelines and recommendations for older people’s live–work housing. These can inform future practice in live–work housing for low-income older people in terms of mobility, accessibility, and improved housing conditions. Implications for future research include understanding place attachment and place-based livelihood in low-income settings and their impact on housing in older age.

A detailed two-layered analysis of the interviews produced basic themes from each of the four organizing themes, and subsequently four global conceptual domains that are integral to live–work housing provision for older people in KT were developed: “space,” “support,” “livelihood,” and “services.”

First, the notion of space use underscores discussion on the live–work dwelling needs of older people at the dwelling scale. These include consideration of sufficient space for living areas, business activities, as well as adequate community and public spaces for interaction and shared use. Additionally, mobility, accessibility, flexibility, furniture, bathrooms fitted with grab rails and adequate storage space are essential elements to live–work housing for older people. It is also suggested that older people should live downstairs in multi-level dwellings such as those with mezzanine floors.

Second, the location of KT makes it an “attractive employment” option for residents, and this allows older people to engage in livelihood activities or voluntary childcare. Other important considerations are easy commuting to and from work and adequate transportation, and opportunities for home entrepreneurship, which are evident in some areas of KT.

Third, the concept of support is vital for the economic prosperity of older residents and their ability to age in place at the neighborhood scale; this includes being dependent, which requires either familial or professional support. Additionally, activities that encourage socializing and providing community support contribute to aging in place for older independent residents. It is also important to highlight community attachment in KT and other community aspects such as sharing of resources and mutual support. Residents’ attachment to the KT community is fueled by their emotional and familiarity needs, as well as their existential needs.

Fourth, the community lacks adequate services and infrastructure, such as health centers and other amenities also on the neighborhood scale. It also lacks reliable electricity and water supply, and waste disposal, which are important for the improvement of its inhabitants’ well-being. There are also several safety issues concerned with accessibility and mobility in open spaces, and with the high-risk use of gas, and pollution from waste that is not disposed of properly due to a lack of a waste removal system.

An effective combination of suitable space for living and livelihood, livelihood opportunities, community and local authority support, and finally adequate services and infrastructure may combine to create a supportive environment with live–work housing. This type of housing can be seen as the familiar environment that will support aging in place and sustainable and healthy living for low-income people in KT.

The analysis of the global conceptual domains raised a number of questions emerging from the basic themes. Firstly, the notion of “space” as an essential construct for living and working purposes and how this may affect live–work arrangements. Implications for policy and practice in this area include development of clear guidelines to support aging in place. Secondly, “livelihood” also understood in this case study as home-based entrepreneurship is essential to sustainable living. Further study could explore the enablers and barriers of home-based enterprises in low-income settings. Thirdly, the importance of “support” provided to older people by the community or younger individuals with the aim to promote aging in place. Future research could study the contribution of intergenerational living to facilitating aging in place and community cohesion. Finally, “services” emerged as the weakest provision in KT given their poor state and their potential negative impact on safety of users, with fire being the main concern. Future research should explore the social and physical integration of health and safety within the neighborhood.

Future research could also explore the process of place attachment in KT to understand how livelihood is manifested and sustained.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the funding body, the Thai Research Assistants who helped in the data collection, and the residents of Klong Toey communities for their participation and contribution to this study. Special thanks to Dr Yanisa Niennattrakul for producing the infographics.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Karim Hadjri

Karim Hadjri: Karim’s research is concerned with inclusive and sustainable design of the built environment, housing and health. This includes addressing the challenges of designing age-friendly environments, as well as enabling environments particularly for people with dementia.

Isaiah Durosaiye

Isaiah Durosaiye: Isaiah’s research is concerned with supporting the creation of livable spaces within the processes of human – environment interactions. This includes the study of how marginalized communities and individuals engage with urban spaces, especially by focusing on conflicting actors and interests in the informal settlements of urban centers in the Global South.

Aliyu Abubakar

Aliyu Abubakar: Aliyu’s research specifically focuses on sustainable housing design and provision. This includes assessing and addressing low-income housing provision in developing countries.

Soranart Sinuraibhan

Soranart Sinuraibhan: Soranart’s research is concerned with the study of built environment for health and well-being. This includes the study of healthcare environment and how individuals engage with livable and healthy spaces, particularly within the hospital.

Sutida Sattayakorn

Sutida Sattayakorn: Sutida’s research is concerned with human’s comfort and health impacts of the built environment. Her research also includes a holistic approach of well-being and sustainability, as well as an investigation on how the physical environment and socio-cultural issues support the health and wellbeing within healthcare facilities.

Supreeya Wungpatcharapon

Supreeya Wungpatcharapon: Supreeya’s research interests focus on low-income housing, informal settlements, community development, participatory design, and urban equality. Her recent research includes inclusive design for built environment for health and well-being.

Saithiwa Ramasoot

Saithiwa Ramasoot: Saithiwa’s research interest is concerned with the sustainable design of built environment through health and well-being, the relationship between old and new architecture, and socio-cultural issues in design. Her past research includes the adaptive reuse of historic architecture and participatory design of healthcare facilities.

References

- Albright, A., Aurchaikarn, S., Chaiyanun, C., Dharani, P., Hanson, P., Nokdhes, N., & Sae-Lim, N. (2011). Identifying strategies to facilitate a successful relocation: The informal settlement of Klong Toey. Chulalongkorn University.

- Allen, R. E. S., & Wiles, J. L. (2013). How older people position their late-life childlessness: A qualitative study. Journal of Marriage & Family, 75(1), 206–220. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.01019.x

- Archer, D. (2010, September 19–23). Empowering the urban poor through community-based slum upgrading: The case of Bangkok, Thailand. 46th ISOCARP Congress, ‘Sustainable City/Developing World’, Nairobi, Kenya.

- Archer, D. (2012). Baan Mankong participatory slum upgrading in Bangkok, Thailand: Community perceptions of outcomes and security of tenure. Habitat International, 36(1), 178–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2011.08.006

- Assatarakul, T. (2015). Socio-economic activities of the elderly in Thailand. Population Review, 54(1). https://doi.org/10.1353/prv.2015.a584406

- Atitruangsiri, A., Holman, G., Page, D., Parkjit, K., Sittapairoj, P., Trott, J., & Wolfson, B. (2017). Mitigating the effects of flooding in the Khlong Toei Slum of Bangkok, Thailand. WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE and CHULALONGKORN UNIVERSITY. https://web.wpi.edu/Pubs/E-project/Available/E-project-030217-054122/unrestricted/Mitigating_Flooding_in_Khlong_Toei.pdf

- Attride Stirling, J. (2001). Thematic networks: An analytic tool for qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 1(3), 385–405. https://doi.org/10.1177/146879410100100307

- Boonyabancha, S. (2005). Baan Mankong: Going to scale with “slum” and squatter upgrading in Thailand. Environment and Urbanization, 17(1), 21–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/095624780501700104

- Boonyabancha, S., & Kerr, T. (2018). Lessons from CODI on co-production. Environment and Urbanization, 30(2), 444–460. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247818791239

- Chi, M. T. H. (1997). Quantifying qualitative analyses of verbal data: A practical Guide. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 6(3), 271–315. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327809jls0603_1

- Dolan, T. (2012). Live-work planning and design: Zero-commute housing. Wiley.

- Durosaiye, I., Hadjri, K., Huang, J., Sinuraibhan, S., Wungpatcharapon, S., Sattayakorn, S., & Ramasoot, S. (2022). Developing and testing a live-work postoccupancy evaluation tool for informal settlements in Thailand. The International Journal of Design Management and Professional Practice, 16(2), 77–94. https://doi.org/10.18848/2325-162X/CGP/v16i02/77-94

- Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

- Ezeadichie, N. (2012). Home-based enterprises in urban spaces: An obligation for strategic planning. Berkeley Planning Journal, 25(1), 44–63. https://doi.org/10.5070/BP325112010

- Friedman, A. (2012). Fundamentals of sustainable dwellings. Island Press. https://doi.org/10.5822/978-1-61091-211-2

- Garabedian, L. A., Smith, K. J., Ossa, D., & DiNino, J. (2006). Negotiating secure land tenure through community redevelopment: A case study from the Klong Toey Slum in Bangkok. Worcester Polytechnic Institute. https://digital.wpi.edu/show/08612n98z

- Ghafur, S. (2001). Beyond homemaking. Third World Planning Review, 23(2), 111–135. https://doi.org/10.3828/twpr.23.2.e03v811p83432851

- Giles, C. (2003). The autonomy of Thai housing policy, 1945–1996. Habitat International, 27(2), 227–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0197-3975(02)00047-4

- Gough, K. V., Tipple, A. G., & Napier, M. (2003). Making a living in African cities: The role of Home-based enterprises in Accra and Pretoria. International Planning Studies, 8(4), 253–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/1356347032000153115

- Habitat for Humanity. (2023). Slum rehabilitation, what is a slum?. Retrieved January 23, 2023, from. https://www.habitatforhumanity.org.uk/what-we-do/slum-rehabilitation/what-is-a-slum/

- Holliss, F. (2015). Beyond Live/work: The architecture of home-based work (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315738048

- Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

- Jitramontree, N., Thongchareon, V., & Thayansin, S. (2011). Good model of elderly care in urban community. Nursing Science Journal of Thailand, 29(3), 67–74. https://he02.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/ns/article/view/2865

- Kakal, A. (2010). Live-work developments: From theory to practice. Toronto Metropolitan University.

- Kigochie, P. W. (2001). Squatter rehabilitation projects that support home-based enterprises create jobs and housing: The case of Mathare 4A, Nairobi. Cities, 18(4), 223–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0264-2751(01)00015-4

- Knodel, J., & Chayovan, N. (2008). Population ageing and the well-being of older persons in Thailand: Past trends, current situation and future challenges. Population Studies Centre, University of Michigan. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=2c61e70a6c8de1a0b5eb1c29ce90fe0bcfc8ce00

- Lawanson, T., & Olanrewaju, D. (2012). The home as workplace: Investigating home based enterprises in low income settlements of the Lagos Metropolis. Ethiopian Journal of Environmental Studies and Management, 5(4), 397–407. https://doi.org/10.4314/ejesm.v5i4.9

- Menon, J., & Melendez, A. C. (2009). Ageing in Asia: Trends, impacts and responses. Journal of Southeast Asian Economies, 26(3), 293–305. https://doi.org/10.1355/AE26-3E

- Mohit, M. A., & Iyanda, S. A. (2016). Liveability and low-income housing in Nigeria. Procedia - Social & Behavioral Sciences, 222, 863–871. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.05.198

- Moser, C. (2008). Assets and livelihoods: A framework for asset-based social policy. In C. Moser & A. Dani (Eds.), Assets, livelihoods and social policy (pp. 43–81). World Bank.

- Nadim, W. (2016). Live-work and adaptable housing in Egypt. Smart & Sustainable Built Environment, 5(3), 289–302. https://doi.org/10.1108/SASBE-08-2016-0019

- Nguyen, P. A., Bokel, R. M. J., & Dobbelsteen, V. D. (2016). Towards a sustainable plan for new tube houses in Vietnam. 17th IPHS Conference: History Urbanism Resilience, Delft.

- Poldma, T. (2008). Dwelling futures and lived experiences: Transforming interior spaces. Design Philosophy Papers, 6(2), 141–155. https://doi.org/10.2752/144871308X13968666267437

- Rourke, L., Terry Anderson, D., Garrison, R., & Archer, W. (2001). Methodological issues in the content analysis of computer conference transcripts. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education (Vol. 12. pp. 8–22). https://telearn.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00197319

- Ruengtam, P. (2020). Conceptual residential design framework to enhance well-being of elderly in Thailand. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering (Vol. 829. pp. 1–7). https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/829/1/012010

- Tipple, G. (2006). Employment and work conditions in home-based enterprises in four developing countries: Do they constitute ‘decent work’? Work, Employment and Society, 20(1), 167–179. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017006061280

- Tonmitr, N., & Ogura, N. (2014). Self-customization for income generation space in the baan mankong program: The case of tawanmai community housing in Khon Kaen Province, Thailand. Journal of Architecture and Planning (Transactions of AIJ), 79(703), 1871–1879. https://doi.org/10.3130/aija.79.1871

- UN-HABITAT. (2016). World cities report 2016: Urbanization and development - emerging futures. https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/download-manager-files/WCR-2016-WEB.pdf

- Uyttebrouck, C., Remøy, H., & Teller, J. (2021). The governance of live-work mix: Actors and instruments in Amsterdam and Brussels development projects. Cities, 113, 103–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2021.103161