Abstract

The present study assesses the relationship between the dimensions of perceived corporate social responsibility (PCSR) and consumer perceptions about a brand. The approach taken herein for PCSR is based on the sustain-centric paradigm. Under this model, PCSR comprises three dimensions: economic, social, and environmental. Accordingly, a system of 11 hypotheses embedded in a conceptual framework is proposed and empirically tested. Measurements for the constructs in the hypotheses are assessed using a structured questionnaire with 521 respondents. The participants evaluated the brands of two major companies in Mexico. Path structural equation modeling is used to test the hypotheses. The results show that, of the three dimensions of PCSR, only economic and social dimensions affect variables related to brand perceptions. The proposed model suggests an explanatory power over attitude toward a brand through firm credibility, brand identification, and perceived functional value. The results imply that consumers disregard firm environmental responsibility when evaluating brands despite growing social efforts attempting to encourage environmental consciousness.

Introduction

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) has been defined as “the continuing commitment by business to behave ethically and contribute to economic development while improving the quality of life of the workforce and their families as well as the local community and society at large” (Watts & Holme, Citation1999, p. 8). The traditional approach for justifying a firm’s CSR programs has been founded on the benefits for society regardless of the firm’s financial performance. In other words, doing good (i.e., CSR) does not always translate into firms achieving a good financial result (Sen & Bhattacharya, Citation2001). However, current business research trends have challenged this idea, claiming that, in the long term, CSR practices can encourage business performance and financial profitability while also favoring human beings and the planet. Albeit not definitive, considerable evidence supports this position (Wang et al., Citation2016), and it has been called the “doing well by doing good” principle (Chernev & Blair, Citation2015; Kang et al., Citation2016). However, this notion has also been subjected to scrutiny. Some evidence shows that CSR actions can favor consumers’ evaluation of a firm and its products (Chernev & Blair, Citation2015; Zhou et al., Citation2012). However, in a study that tested four mechanisms by which a firm can implement CSR tactics as an aspect of its corporate strategy (Kang et al., Citation2016), only a few of the mechanisms were found to be profitable. The financial returns are consistently positive only when CSR is integral to a good management long-term policy. This strongly suggests that not all CSR actions necessarily produce favorable returns.

Perceived corporate social responsibility (PCSR), as based on a sustain-centric paradigm, has been conceptualized as a multidimensional construct comprising economic, social, and environmental components (Niskala & Tarna, Citation2003; Panwar et al., Citation2006). When a consumer evaluates a brand for self-consumption, one can assume that their PCSR of the firm will influence their evaluation. Some research has suggested that consumers from both developing and developed countries are becoming increasingly interested in matters of responsible consumption and are thus increasingly receptive to responsible efforts by brands and companies (Agrawal & Gupta, Citation2018). However, despite efforts for the adoption of CSR policies by organizations, the literature suggests that customers are not equally attracted by the three aforementioned components and do not necessarily consider such efforts when evaluating brands for purchase (Currás-Pérez et al., Citation2018; Peloza & Shang, Citation2011). Hence, the three dimensions of PCSR may elicit different effects on customer brand assessment. For example, in a study that assessed the effects of PCSR dimensions on customer perceived value, all three components were found to tend to affect perceived emotional value, but only the social dimension was likely to affect perceived social value (Currás-Pérez et al., Citation2018). Moreover, the social and economic dimensions of PCSR seem to affect perceived functional value, while the environmental dimension does not.

CSR generates value for consumers because it is thought to trigger favorable sentiments toward a firm (Currás-Pérez et al., Citation2018). The present study, however, posits that for CSR strategies to be profitable, customers should perceive those actions favorably and those perceptions should be transferred to the perception of the firm’s brand. One study on cause-related marketing tactics (a brand’s promise to donate to a social cause) confirmed that only clients with a high level of brand awareness expressed a favorable perception of a brand when there was a good fit between the brand’s image and the sponsored social cause (Nan & Heo, Citation2007). Generally, companies can improve consumer attitude by improving corporate capabilities and efforts to offer quality products and services (Wang et al., Citation2008). However, an increasing number of companies also seek to achieve good brand associations by addressing matters of social perception (Brown & Dacin, Citation1997). This may be attributable to the growing tendency of consumers and other stakeholders to feel more committed to social issues and to reward company promotions that seem more committed to society (Du et al., Citation2007; Luo & Bhattacharya, Citation2006). In summary, PCSR, together with the generation of functional value, could become an attribute of a brand that improves consumer attitude toward said brand (i.e., stronger favorable associations regarding the brand).

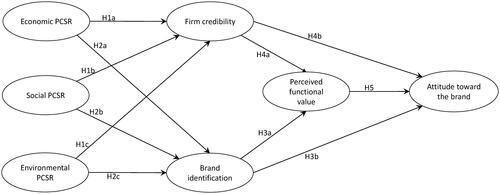

How does the level of PCSR relate to attitude toward a brand? Previous research has suggested that associations of corporate capability and CSR exert a parallel influence on consumer attitude to a brand (He & Li, Citation2011; Sen & Bhattacharya, Citation2001). In this work, we propose that the three dimensions of PCSR influence consumer attitude toward a brand insofar as these dimensions are a precursor to perceived functional value (Currás-Pérez et al., Citation2018; Peloza & Shang, Citation2011). Furthermore, we maintain that this influence occurs because PCSR improves two key company–consumer relational variables: credibility and personal identification with a brand or brand identification (He & Li, Citation2011).

First, therefore, we analyze the influence of the three dimensions of PCSR, as based on the sustain-centric paradigm (Niskala & Tarna, Citation2003; Panwar et al., Citation2006), on firm credibility and brand identification. Second, we examine the mediating role of perceived functional value between the two relational variables (firm credibility and brand identification) and attitude toward a brand. Thus, our research intends to contribute to the body of knowledge on CSR and consumer behavior by exploring mechanisms for generating brand acceptance based on the dimensions of PCSR and perceived functional value. This assessment contrasts with those of previous research wherein functional value was not assessed as a structural variable, as though the consumer simply makes a tradeoff between PCSR and functional value (Sen & Bhattacharya, Citation2001).

To meet these two objectives, a model based on 11 hypotheses is outlined and empirically tested. If consumers strongly believe that a firm is socially responsible to the extent that it has a favorable effect on the perceptions toward the brand, thereby triggering possible purchases, a company would be further encouraged to adopt CSR policies. Although previous studies have offered some evidence that CSR activities may improve business performance (Sun et al., Citation2019; Wang et al., Citation2016), information on what occurs in between the CSR activities and such a performance remains scarce. The present research endeavors to address this gap by proposing and testing a structural conceptual framework in an attempt to connect the three dimensions of customer PCSR (economic, social, and environmental) with the attitude toward a brand and to thus make a unique contribution to the field. Moreover, this work might shed some light on the relative importance of each CSR dimension in terms of consumer perception and brands.

Conceptual framework

According to the literature, the extent of a firm’s CSR as perceived by a consumer may contribute to the overall reputation of a firm (Aksak et al., Citation2016; Saeidi et al., Citation2015; Stanaland et al., Citation2011). Thus, presumably, when a consumer believes that a company is socially responsible, it could constitute an information cue that encourages further positive beliefs regarding that company. Based on factors proposed under a sustainable development approach (Chow & Chen, Citation2012), the PCSR construct was proposed as a mix of specific dimensions through which a company would be, or should be, considered socially responsible. These dimensions involve three areas (Alvarado-Herrera et al., Citation2017; Panwar et al., Citation2006). The first concerns the extent to which a firm is perceived to be responsible regarding financial aspects, such as employee compensation, the quality of its products, and offering fair prices (economic PCSR). The second area involves the level of consumer perception for which a company is responsible in terms of observing ethical behavior and generating community welfare (social PCSR). The third is the extent to which an enterprise is committed to respecting the ecosystem (environmental PCSR). These three dimensions of PCSR are consistent with a range of factors identified in an exploratory study that attempted to explain how CSR can constitute an effective approach in building corporate identity (Bravo et al., Citation2012).

Studies have shown that PCSR tends to have a significant effect on corporate image and reputation (David et al., Citation2005; Melo & Garrido-Morgado, Citation2012). Moreover, one study revealed that interaction between a firm and customers, with credible messages regarding CSR activities, can be an effective method of improving corporate reputation (Eberle et al., Citation2013). In addition, according to evidence from the aforementioned study, corporate reputation has a positive relationship with consumer brand credibility. Furthermore, changes in company reputation can also affect the credibility of the brand for other stakeholders (Herbig & Milewicz, Citation1993). Although the relationship between CSR marketing activities and actual consumer behavior is complex, credibility appears to have a substantial influence as a mediating variable in this relationship (Inoue & Kent, Citation2014). Therefore, a consumer’s PCSR should presumably exhibit some kind of relationship with the perceived credibility of a firm. Hence, this study proposes that, through its three dimensions, PCSR affects firm credibility as follows.

H1a. Economic PCSR has a direct effect on firm credibility.

H1b. Social PCSR has a direct effect on firm credibility.

H1c. Environmental PCSR has a direct effect on firm credibility.

One investigation showed that PCSR can generate a positive consumer attitude and that the latter tends to influence purchase intentions (Kang & Hustvedt, Citation2014). However, despite being statistically significant, the values for the relationships between the variables presented in the aforementioned study were not high (r = .17 and r = .33, respectively). Similar results were found in a study of Chinese consumers, which verified that PCSR activities elicit an overall improved consumer perception of a company, favoring purchase intention (Tian et al., Citation2011). The previous study seems to accord with the conclusions of earlier works. Although empirical evidence exists for the correlation between PCSR and consumer purchase intention as well as purchase behavior, its causality embodies a highly complex chain of relationships (David et al., Citation2005). The present study addresses this complexity by proposing that several mediating variables may be missing in the development of a strong statistical model to substantiate a more complete explanation of how PCSR influences consumer brand perception. Most studies have treated PCSR as a one-dimensional construct (as addressed earlier). Thus, this study proposes a model that could reveal the relationships linking different dimensions of PCSR and attitude toward brands, applying some mediating variables that have not been considered in the literature, such as brand identification ().

Nan and Heo (Citation2007) experimental research indicated that when advertisement presents a good fit between CSR content and brand image, particularly among customers with high levels of brand awareness, it can improve consumer attitude toward a firm. However, in the aforementioned study, advertising with CSR content that did not fit the brand’s image had no effect on consumer attitude toward the product, brand, or advertisement. Similarly, evidence supports the contention that when the type of CSR activities is consistent with the type of CSR that is important to the consumer, a strong relationship tends to exist between the PCSR and the level of identification (self-congruence) of the consumer with the firm in question (Sen & Bhattacharya, Citation2001). Moreover, interactive firm–customer efforts to communicate CSR initiatives can generate stronger feelings of consumer identification with the company and lead to positive word of mouth (Eberle et al., Citation2013). Therefore, the dimensions of PCSR could be related to the identification (self-congruence) that a customer feels with a brand. Accordingly, this study proposes the following connections.

H2a. Economic PCSR has a direct effect on brand identification.

H2b. Social PCSR has a direct effect on brand identification.

H2c. Environmental PCSR has a direct effect on brand identification.

PCSR is empirically related to the perceived value of a firm’s brand (Currás-Pérez et al., Citation2018). The notion of customer perceived value in the academic literature derives from the exchange between the perceived benefits obtained by the customer from the company’s offer and how much the customer gives in return (cost or sacrifice). This perceived value can be highly idiosyncratic and can vary widely from one consumer to another (González-Gallarza et al., Citation2011). The sacrifice includes monetary and non-monetary costs, such as the time spent, energy consumed, and stress experienced. Accordingly, the existing research has accepted perceived value as a multidimensional construct that encompasses functional, hedonic, and social dimensions (Sweeney & Soutar, Citation2001). The present study focuses on the role of functional (or utilitarian) value as a mediator between the outcomes of PCSR (credibility and identification) and attitude toward a brand. The functional value represents a strong motivator because it embodies the consumer’s rational economic valuation. It constitutes the search for a specific cost–benefit outcome; thus, it is considered cognitive and behavioral (Babin et al., Citation1994).

Some of the existing literature suggests that perceived functional value and the level of congruity between brand image and consumer self-concept (brand identification) are variables related to purchase intentions toward a brand (Yeh et al., Citation2016). Accordingly, under certain circumstances (e.g., when CSR activities are related to issues that are important to consumers), a firm’s social activities might improve brand image. Making a brand more acceptable and consistent with consumers’ self-image, might motivate a customer to pay a higher price for the firm’s products. In general, the evidence shows that, regardless of the consumer’s culture, the perceived identification with an object tends to trigger favorable attitudes (Kaur & Soch, Citation2018). Furthermore, a recent study asserted that the congruity between a brand’s image and the actual or ideal self-image activates emotions that can have a positive effect on the perceived quality of the brand (Klabi, Citation2020). Moreover, consumers who identify with a brand’s image tend to manifest a stronger commitment toward that brand, consequently generating favorable word of mouth (Rambocas & Ramsubhag, Citation2018; Tuškej et al., Citation2013). Therefore, the following hypotheses seem logical.

H3a. Brand identification has a direct effect on perceived functional value.

H3b. Brand identification has a direct effect on attitude toward the brand.

The empirical evidence for various products and services shows that brand credibility can have strong positive effects on the perceived quality and perceived functional value of a brand (Baek et al., Citation2010; Baek & Whitehill King, Citation2011). In this relationship, customer perceived value relates to a reduction in the search for information because credibility can reduce the perceived risk and improve the overall perception toward a brand (Baek et al., Citation2010; Hussain et al., Citation2017). Accordingly, brands carry information from firms to consumers; therefore, firm credibility can have a direct effect on brand perception (Jahanzeb et al., Citation2013). Hence, the following hypotheses are presented.

H4a. Firm credibility has a direct effect on perceived functional value.

H4b. Firm credibility has a direct effect on attitude toward a brand.

In the process of product–money exchange, perceived functional value can be interpreted as how much a customer believes will be obtained when assessing how much will be given away for a product (Sweeney & Soutar, Citation2001). A high functional value implies that a consumer perceives a substantially higher benefit from purchasing the product than from not doing so (i.e., the obtained goods have more value than the money sacrificed). Furthermore, a perceived high functional value can encourage consumers to adopt a favorable predisposition toward a brand. This perspective has been corroborated in several commercial activities (Ruiz-Molina & Gil-Saura, Citation2008). Thus, the perceived functional value has been established as a key antecedent of consumer brand equity variables (Jahanzeb et al., Citation2013). Therefore, to investigate how the dimensions of CSR connect to brand attitude through mediating variables, the following hypothesis seems applicable.

H5. Perceived functional value has a direct effect on attitude toward a brand.

Study design

A cross-sectional empirical study was conducted to test the theoretical model and the hypotheses. The study was performed with a sample of actual consumers of mass consumption products offered by two transnational firms in the Mexican city of Hermosillo, Sonora. To elicit consumers’ perceptions of CSR, four main criteria were considered for selecting the two brands used herein: to (1) be well known, (2) be consumed by large population segments, (3) not be socially stigmatized, and (4) undertake CSR initiatives. The sample included 521 respondents (301 consumers evaluating the brand Bimbo and 220 evaluating the Walmart brand, two large and renowned companies/brands in Mexico). For CSR to have any kind of effect, customers must possess considerable information about the firm in question (Öberseder et al., Citation2011). Data were collected through a face-to-face survey, which was based on a structured questionnaire; the survey was conducted during the annual celebration of Dia de los Muertos in the two cemeteries of the city. Participation in the survey was completely anonymous and voluntary. The profile of the target population included individuals who were residents of Mexico and had purchased (and consumed) products from the two firms at least once within the six months prior to the observation. The open population of the city constituted the primary sampling frame for the study. The sample was selected using a two-stage approach. The first stage was by quota (half of the sample from each cemetery); the second followed a random approximation to subjects with a systematic jumping rule. The information was gathered using a structured questionnaire. The questionnaires of all the 521 respondents were validated as complete and correctly answered. Although a convenience sampling procedure, the sample size would correspond to an estimation error of ±4.27% with a confidence level of 95% (at maximum population heterogeneity). The data were depurated and descriptively analyzed. The estimation and testing of the proposed relationships were conducted via structural equation modeling (SEM) with the maximum likelihood estimation method (AMOS software), which is considered a rigorous, robust technique for measurement validity and theory testing (Anderson & Gerbing, Citation1988). The sample comprised 266 women (51%) and 255 men (49%), with ages ranging from 18 to 80 years (mean = 31.3 years, standard deviation = 14.1 years). Students made up 47% of the participants (245), while 29% were professionals (151), and 24% (125) had different main activities at the time of the interviews. Further, 198 respondents (38%) had a university education.

Measurements

Appendix A shows the 23 items that were used for the seven latent variables in the model, which were derived from scales with previously confirmed reliability and validity. Perceived economic, social, and environmental dimensions of CSR were assessed using nine items from the CSRConsPerScale (Alvarado-Herrera et al., Citation2017). Firm credibility was measured using three items from a study by Lafferty and Goldsmith (Citation1999). Perceived functional value was assessed using three items from the PERVAL scale (Sweeney & Soutar, Citation2001). Brand identification was measured using four items employed by Currás-Pérez et al. (Citation2009). Mackenzie and Lutz’s (Citation1989) four-item scale was used to assess attitude toward the brand. Prior to the formal fieldwork, a preliminary questionnaire was tested with a sample of 25 consumers. This pilot test resulted in improvements to the wording of the items and the questionnaire format. Each item was operationalized through a Likert-type scale of seven points (1 = Strongly disagree to 7 = Strongly agree).

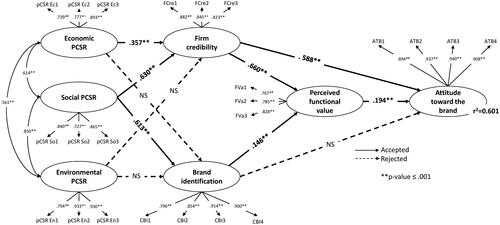

The psychometric properties of the scales were assessed to confirm measurement reliability and validity. presents the results of the validity and reliability tests of the measurements. The items related to the dimensions of the CSR construct were first subjected to a factorial analysis with varimax rotation to test the convergent–discriminant validity of the scale. Single factorial analyses were performed to test the convergent validity of the items of the other constructs. Because these constructs were treated theoretically in a one-dimensional manner, discriminant validity testing was not required; therefore, rotation was unneeded. As shown in , the factorial analysis for the items related to the dimensions of CSR shows the items as loaded into three different factors (each item in its expected component). For this analysis, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) coefficient (.89) and Bartlett’s test (chi-square = 3283.5, sig = .000) showed a good fit of the model to the data. In this case, the varimax rotation confirms the total independence (item discrimination) of the three latent variables. For the other factorial analyses, items converged as expected in single principal component models, showing a good fit in each case (with high KMO coefficients and statistically significant values for the Bartlett’s tests) and thereby showing evidence of unidimensionality (Gerbing & Anderson, Citation1988).

Table 1. Measurement assessment.

The results also indicated that the convergent validity of the measurement model can be established as follows. (1) All the items relate significantly to their corresponding factor (p < 0.01). (2) The sizes of all the standardized loadings, and their averages, are larger than 0.70. (3) All Cronbach’s alphas exceed the recommended value of 0.70 (Tavakol & Dennick, Citation2011) ). (4) The composite reliability (or omega coefficient) of the items in each factor was higher than the desired minimum value of 0.60 (Bagozzi & Yi, Citation1988; Dunn et al., Citation2014). (5) Each average variance extracted (AVE) coefficient is greater than the recommended minimum cutoff of 0.5 (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). Finally, the multifactorial solution of the measurements, along with discrimination validity, evidenced that no common method bias effect was generated when measuring the variables with a single questionnaire because these results were sufficiently consistent with Harman’s test to discard this problem (see the use of this test in Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). The following section shows that the path SEM model used for the hypotheses testing presents a good fit of the model to the data. This further confirms the convergence–discriminant validity of the measurements as all the standardized measurement weights of the observed variables ranged between .73 and .94 in relation to each of their latent variables (confirming the factorial loads in ). Nevertheless, in the SEM model, collinearity among the three latent variables of PCSR was found, suggesting interdependence among these dimensions (). However, this is a commonly encountered phenomenon with multidimensional constructs in the behavioral sciences (Edwards, Citation2001; Polites et al., Citation2012). To confirm the measurement validity once again, a confirmatory SEM measurement model (with collinear relationships between all the latent variables) was executed. Here, all measurement weights (between the observed variables and their corresponding latent variables) were statistically significant and ranged between .73 and .94 (standardized coefficients). The results of absolute fit indexes were acceptable with a relative/normed chi-square ratio (χ2/df) value of 2.43 (Wheaton et al., Citation1977) and a root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) value of .052 (Hooper et al., Citation2008; MacCallum et al., Citation1996). In addition, base line fit coefficients were highly satisfactory with a normed fit index (NFI) value of .95, an incremental fit index (IFI) value of .97, a non-normed fit index (NNFI) value of .96, and a comparative fit index (CFI) value of .97 (Hooper et al., Citation2008).

Results

To test the proposed hypotheses and the theoretical model (), as stated earlier, SEM was performed using the maximum likelihood method. An inspection of the variables showed low values of skewness (under ±1.03) and kurtosis (under ±0.93), evidencing a fairly approximation to normality. This finding, along with the robustness of this SEM method using rescaled (standardized) coefficients and no missing data in the matrix, suggests conditions for reliable results from SEM even under the violation of the assumption of independence between the exogenous variables (Benson & Fleishman, Citation1994; Savalei, Citation2008). and present the empirical estimates for the main-effects model. The results of the structural path model suggest a good fit of the model to the data. Regarding absolute fit indexes, even when χ2 = 562.3 (216 df) was significant (p < 0.01), the relative/normed chi-square ratio (χ2/df = 2.6) was smaller than the benchmark value of 5 (Wheaton et al., Citation1977). The RMSEA (= 0.056) was below the maximum recommended value of 0.08 (MacCallum et al., Citation1996). The baseline fit coefficients (NFI = 0.95; IFI = 0.94; NNFI = 0.96; CFI = 0.97) were also a good fit to the data; all the values passed the recommended value of 0.9, including one instance of 0.95 (Hooper et al., Citation2008).

Table 2. Testing relationships.

Of the eleven relationships tested within this statistical model and its data, seven suggested acceptance (). In , the path coefficients obtained are higher for the relationships of social PCSR with firm credibility and brand identification. Furthermore, a high coefficient was found between firm credibility and attitude toward the brand. These relationships reveal a considerably strong indirect effect of the social dimension of PCSR on the perceived functional value and attitude toward the brand (with standardized indirect effects of .50 and .51, respectively). Thus, judging from the standardized path coefficients of the statistical model, the social dimension of PCSR has the highest explanatory power over brand perception among the three variables. Overall, the statistical model presents a considerable level of explanation over the final dependent variable (attitude toward the brand) of 60% of its variance (r2 = 0.601).

Discussion

Conclusions

The results herein support multiple conclusions. Economic PCSR appears to have an indirect effect on attitude toward the brand, mediated by firm credibility and the customer’s perceived functional value. Social PCSR seems to have a significant indirect effect on attitude toward the brand, mediated by firm credibility, brand identification, and perceived functional value. Although health issues may constitute the type of expectations that are most related to CSR activities by consumers in developed and developing countries (Gassler et al., Citation2016), and individuals in general perceive that the environment can have an effect on the self’s health (Parsons, Citation1991), surprisingly, environmental PCSR showed no effect on any variable in the model. Similarly, Currás-Pérez et al. (Citation2018) found no effects from the environmental dimension on perceived functional value (although their investigation was not on brand perception). Firm credibility seems to have a direct effect on attitude toward the brand, while brand identification may have an indirect effect on attitude toward the brand that is mediated by perceived functional value. Thus, perceived functional value tends to affect attitude toward the brand. Finally, of the three dimensions, only the economic and social dimensions of PCSR exhibited an explanatory power over variables of brand perception. The environmental dimension of PCSR appears not to have any kind of explanatory power over these types of variables.

Notably, of the three dimensions of CSR, the social dimension displays high and significant association coefficients with firm credibility and brand identification. Thus, it may represent the most relevant dimension of CSR to raise favorable consumer perceptions toward a brand (at least in the context of the present study). Similarly, in countries with more collective cultures, such as Mexico and India (compared to the United States and Canada), the perceived social aspects of a brand would be expected to be deemed more important for engendering purchase intentions (Kaur & Soch, Citation2018; Yang et al., Citation2019). Moreover, in cultures with stronger strict social norms, corporate social performance (social aspects of CSR) tends to have a higher correlation with financial performance than that in cultures with less strict (indulgent) social norms (Sun et al., Citation2019).

Theoretical implications

If companies adopt CSR activities as an aspect of their regular operations regardless of any possible favorable business performance outcome (i.e., merely adopting CSR activities for the common good), it can prove highly beneficial. However, developing a long-term CSR culture in companies would be augmented by the conviction that CSR strategies are a good business practice that can generate positive financial results. In this study, we offer additional evidence that the “doing well by doing good” principle (Chernev & Blair, Citation2015; Kang et al., Citation2016) works, showing a relationship between the different dimensions of PCSR, firm credibility, brand identification, perceived functional value, and the improvement of attitude regarding the brand. Although there are numerous studies on CSR activities that measure firms’ financial performance (e.g., Sun et al., Citation2019; Wang et al., Citation2016), to the best of the knowledge of the authors of the present study, research on the relationship between CSR and variables related to consumer brand perception remains surprisingly scarce. As CSR and firm performance may be related, understanding this relationship from the perspective of customer behavior is crucial because the customers are the purchasers of the products that generate financial value. In the literature, consumer brand perception represents a group of variables with an ample explanatory power on consumer purchase behavior (a well-recognized principle in marketing). Moreover, the brand is an important vehicle through which CSR promises can be connected with stakeholders (Kitchin, Citation2003). Therefore, this study endeavors to explain the mechanism by which the perception of CSR actions links with consumer attitude toward a brand. First, this study shows that the functional value elicited by PCSR may be a precursor to brand attitude. Namely, the social character of the corporation is capable of improving the perceptions of consumers (i.e., functional value), which can cultivate an improvement in brand associations (i.e., attitude toward the brand). Second, although this research confirms that brand credibility and identification mediate the relationship between PCSR and perceived functional value (He & Li, Citation2011), it also assesses the influence of each dimension of CSR in this relationship. However, the evidence indicates that customers must perceive CSR activities as legitimate for it to have an effect on the credibility of the company (Inoue & Kent, Citation2014). Thus, the social dimension of CSR tends to improve the brand credibility and is capable of generating a higher level of consumer brand identification. Finally, at least in the context of our study, the environmental dimension is not a precursor to perceived functional value as it does not significantly influence brand credibility or identification.

Despite a growing worldwide trend toward responsible consumption behavior (Agrawal & Gupta, Citation2018), CSR actions do not seem to be a priority for customers when choosing products. Variables such as the country of origin, price, product quality, and service performance tend to have a far greater impact on purchase decisions (Öberseder et al., Citation2011). Accordingly, a considerably small proportion of consumers tend to prioritize CSR when making purchase decisions. Thus, regardless of the country of origin, only consumers with high levels of unselfishness and environmental knowledge tend to evince interest in matters related to environmental sustainability (Perez-Castillo & Vera-Martínez, Citation2021; Uddin & Khan, Citation2018).

Managerial implications

Consumers from developed and developing countries have become more aware of the actions of brands and firms that favor responsible consumption (Agrawal & Gupta, Citation2018). Therefore, based on the current findings, worldwide practitioners should recognize the important role of brand credibility and identification to design CSR activities that can favor consumer brand attitude. As stated earlier, brand identification favors positive consumer attitudes regardless of the specific country or culture (Kaur & Soch, Citation2018).

However, these activities must be perceived as legitimate and consistent with the brand’s image to effectively improve credibility (Inoue & Kent, Citation2014; Nan & Heo, Citation2007) and thus attitude toward the brand. Moreover, such activities might prove more effective if they are consistent with the socially responsible aspects that are relevant for the targeted customers as this will likely increase brand identification (Sen & Bhattacharya, Citation2001). Hence, to improve the social dimension of PCSR, companies should heed the social needs of the local communities in which they operate, donate money to local social causes, and implement codes of conduct that respect the local idiosyncrasy of customers.

If companies seek to improve brand perceptions through CSR actions, an emphasis on the social and economic dimensions of PCSR should be prioritized in the short term because these dimensions of PCSR affect firm credibility, brand identification, perceived functional value, and attitude toward the brand (at least in the context of the present study: Mexico). However, from a global management point of view; it should be noted that the social aspects of CSR may have a greater effect in collective societies (e.g., Mexico and India) than in more individualistic cultures (Kaur & Soch, Citation2018; Yang et al., Citation2019). Accordingly, in countries tending toward individualism (e.g., Canada and United States), the economic aspect of CSR, or even the environmental dimension, might have a higher level of effectiveness in improving consumer attitude.

Similarly, global management should consider that the social aspects of CSR tend to have a higher correlation with financial performance for countries with stricter social norms (Sun et al., Citation2019). Therefore, economic and environmental CSR actions might be more effective in promoting consumer attitude toward a brand in countries with less strict social norms.

According to our findings, the environmental dimension of PCSR did not affect brand perceptions. This is a worrying sign in that some consumers may not consider the environmental activities of a company while considering a brand. It is important to remember that not all CSR activities generate positive returns for a company (Kang et al., Citation2016). Therefore, in the long term, companies and society as a whole should empathically communicate the importance of corporate environmental actions to consumers as a crucial factor for general wellbeing. In this manner, changes in consumer beliefs could serve as a pull factor to motivate environmental CSR actions. Such stakeholder pressure has been favorably tested as a driver for companies to adopt environmentally friendly actions (Bıçakcıoğlu, Citation2018).

Limitations and future studies

This study was conducted in Mexico. The finding that the social and economic dimensions of PCSR influence brand perception while the environmental dimension does not, in particular, may be unique to the consumers of Mexico or to the sample herein. Therefore, future studies should test such effects in other countries and contexts to support the development of a more generalizable theory. Accordingly, comparative studies of countries that are characterized by more individualistic cultures and countries considered to have more collective cultures would be valuable because there is evidence that the social aspects are less important in the former than in the latter in terms of motivating purchase behavior (Kaur & Soch, Citation2018; Yang et al., Citation2019). For instance, environmental PCSR might have a more significant effect on brand perception in an individualistic society than social PCSR (in contrast with the present findings as Mexican culture tends to be more collective, as stated earlier).

Although people tend to prefer companies that are socially responsible, not all consumers respond equally to CSR initiatives. Despite a company’s best efforts to adopt CSR trends, some purchase behaviors will not change based on these activities. Conversely, some customers might modify their purchase behavior heavily in favor of the company in response to CSR activities (Mohr et al., Citation2001a, Citation2001b). This implies a lack of linearity between PCSR and the expected outcome of consumer behavior. This lack may explain why not all the relationships in the statistical model have the desired path coefficients despite being significant—albeit not as high as desired. The present study is limited to suggesting some possible connections between PCSR and the attitudinal acceptance of a brand. Possible customer behavioral outcomes of PCSR were not considered herein, although several new connections in an already complex theoretical model were proposed. Moreover, linking CSR activities to actual consumer behavior is challenging (David et al., Citation2005). Therefore, future research should consider the relationship of CSR activities with additional measurements of customer behavior. These measurements could include the intention to purchase (as marginally evidenced by Sen & Bhattacharya, Citation2001; Tian et al., Citation2011; and Kang & Hustvedt, Citation2014) and the repurchase rate, mediated by a construct that can act as a stronger mediating variable than those used in the existing literature: attitude toward the brand.

References

- Agrawal, R., & Gupta, S. (2018). Consuming responsibly: Exploring environmentally responsible consumption behaviors. Journal of Global Marketing, 31(4), 231–245. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08911762.2017.1415402

- Aksak, E. O., Ferguson, M. A., & Atakan Duman, S. (2016). Corporate social responsibility and CSR fit as predictors of corporate reputation: A global perspective. Public Relations Review, 42(1), 79–81. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2015.11.004

- Alvarado-Herrera, A., Bigne, E., Aldas-Manzano, J., & Curras-Perez, R. (2017). A scale for measuring consumer perceptions of corporate social responsibility following the sustainable development paradigm. Journal of Business Ethics, 140(2), 243–262. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2654-9

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

- Babin, B. J., Darden, W. R., & Griffin, M. (1994). Work and/or fun: Measuring hedonic and utilitarian shopping value. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(4), 644–656. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/209376

- Baek, T. H., Kim, J., & Yu, J. H. (2010). The differential roles of brand credibility and brand prestige in consumer brand choice. Psychology and Marketing, 27(7), 662–678. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20350

- Baek, T. H., & Whitehill King, K. (2011). Exploring the consequences of brand credibility in services. Journal of Services Marketing, 25(4), 260–272. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/08876041111143096

- Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16(1), 74–94. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02723327

- Benson, J., & Fleishman, J. A. (1994). The robustness of maximum likelihood and distribution-free estimators to non-normality in confirmatory factor analysis. Quality & Quantity, 28(2), 117–136. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01102757

- Bıçakcıoğlu, N. (2018). Green business strategies of exporting manufacturing firms: Antecedents, practices, and outcomes. Journal of Global Marketing, 31(4), 246–269. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08911762.2018.1436731

- Bravo, R., Matute, J., & Pina, J. M. (2012). Corporate social responsibility as a vehicle to reveal the corporate identity: A study focused on the websites of Spanish financial entities. Journal of Business Ethics, 107(2), 129–146. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-1027-2

- Brown, T., & Dacin, P. (1997). The company and the product: Corporate associations and consumer product responses. Journal of Marketing, 61(1), 68–84. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299706100106

- Chernev, A., & Blair, S. (2015). Doing well by doing good: The benevolent halo of corporate social responsibility. Journal of Consumer Research, 41(6), 1412–1425. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/680089

- Chow, W. S., & Chen, Y. (2012). Corporate sustainable development: Testing a new scale based on the mainland Chinese context. Journal of Business Ethics, 105(4), 519–533. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0983-x

- Currás-Pérez, R., Dolz, ‐Dolz, C., Miquel, ‐Romero, M. J., & Sánchez‐García, I. (2018). How social, environmental, and economic CSR affects consumer‐perceived value: Does perceived consumer effectiveness make a difference?Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 25(5), 733–747. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1490

- Currás-Pérez, R., Bigné-Alcañiz, E., & Alvarado-Herrera, A. (2009). The role of self-definitional principles in consumer identification with a socially responsible company. Journal of Business Ethics, 89(4), 547–564. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-0016-6

- David, P., Kline, S., & Dai, Y. (2005). Corporate social responsibility practices, corporate identity, and purchase intention: A dual-process model. Journal of Public Relations Research, 17(3), 291–313. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532754xjprr1703_4

- Du, S., Bhattacharya, C., & Sen, S. (2007). Reaping relational rewards from corporate social responsibility: The role of competitive positioning. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 24(3), 224–241. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2007.01.001

- Dunn, T. J., Baguley, T., & Brunsden, V. (2014). From alpha to omega: A practical solution to the pervasive problem of internal consistency estimation. British Journal of Psychology (London, England : 1953), 105(3), 399–412. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12046

- Eberle, D., Berens, G., & Li, T. (2013). The impact of interactive corporate social responsibility communication on corporate reputation. Journal of Business Ethics, 118(4), 731–746. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1957-y

- Edwards, J. R. (2001). Multidimensional constructs in organizational behavior research: An integrative analytical framework. Organizational Research Methods, 4(2), 144–192. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/109442810142004

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 382–388. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800313

- Gassler, B., von Meyer-Höfer, M., & Spiller, A. (2016). Exploring consumers’ expectations of sustainability in mature and emerging markets. Journal of Global Marketing, 29(2), 71–84. (2015). 1133869 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08911762

- Gerbing, D. W., & Anderson, J. C. (1988). An updated paradigm for scale development incorporating unidimensionality and its assessment. Journal of Marketing Research, 25(2), 186–192. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378802500207

- González-Gallarza, M., Gil-Saura, I., & Holbrook, M. B. (2011). The value of value: Further excursions on the meaning and role of customer value. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 10(4), 179–191. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.328

- He, H., & Li, Y. (2011). CSR and service brand: The mediating effect of brand identification and moderating effect of service quality. Journal of Business Ethics, 100(4), 673–688. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-010-0703-y

- Herbig, P., & Milewicz, J. (1993). The relationship of reputation and credibility to brand success. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 10(3), 18–24. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000002601

- Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. (2008). Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal on Business Research Methods, 6(1), 53–60.

- Hussain, S., Ahmed, W., Jafar, R. M. S., Rabnawaz, A., & Jianzhou, Y. (2017). eWOM source credibility, perceived risk and food product customer’s information adoption. Computers in Human Behavior, 66, 96–102. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.09.034

- Inoue, Y., & Kent, A. (2014). A conceptual framework for understanding the effects of corporate social marketing on consumer behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 121(4), 621–633. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1742-y

- Jahanzeb, S., Fatima, T., & Mohsin Butt, M. (2013). How service quality influences brand equity: The dual mediating role of perceived value and corporate credibility. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 31(2), 126–141. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/02652321311298735

- Kang, C., Germann, F., & Grewal, R. (2016). Washing away your sins? Corporate social responsibility, corporate social irresponsibility, and firm performance. Journal of Marketing, 80(2), 59–79. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.15.0324

- Kang, J., & Hustvedt, G. (2014). Building trust between consumers and corporations: The role of consumer perceptions of transparency and social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 125(2), 253–265. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1916-7

- Kaur, K., & Soch, H. (2018). Does image matter while shopping for a smartphone? A cross-cultural study of Indian and Canadian consumers. Journal of Global Marketing, 31(2), 142–153. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08911762.2017.1360431

- Kitchin, T. (2003). Corporate social responsibility: A brand explanation. Journal of Brand Management, 10(4), 312–326. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.bm.2540127

- Klabi, F. (2020). Self-image congruity affecting perceived quality and the moderation of brand experience: The case of local and international brands in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Journal of Global Marketing, 33(2), 69–83. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08911762.2019.1614242

- Lafferty, B. A., & Goldsmith, R. E. (1999). Corporate credibility’s role in consumers’ attitudes and purchase intentions when a high versus a low credibility endorser is used in the ad. Journal of Business Research, 44(2), 109–116. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(98)00002-2

- Luo, X., & Bhattacharya, C. B. (2006). Corporate social responsibility, customer satisfaction, and market value. Journal of Marketing, 70(4), 1–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.70.4.001

- MacCallum, R. C., Browne, M. W., & Sugawara, H. M. (1996). Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modelling. Psychological Methods, 1(2), 130–149. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.1.2.130

- MacKenzie, S. B., & Lutz, R. J. (1989). An Empirical Examination of the Structural Antecedents of Attitude toward the Ad in an Advertising Pretesting Context. Journal of Marketing, 53(2), 48–65. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/002224298905300204

- Melo, T., & Garrido-Morgado, A. (2012). Corporate reputation: A combination of social responsibility and industry. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 19(1), 11–31. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.260

- Mohr, L. A., Webb, D. J., & Harris, K. E. (2001b). Do consumers expect companies to be socially responsible? The impact of corporate social responsibility on buying behavior. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 35(1), 45–72. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6606.2001.tb00102.x

- Mohr, L., Webb, J., & Harris, K. (2001a). Do customers expect companies to be socially responsible? The impact of CSR on buying behavior. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 35(1), 45–32. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6606.2001.tb00102.x

- Nan, X., & Heo, K. (2007). Consumer responses to corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives: Examining the role of brand-cause fit in cause-related marketing. Journal of Advertising, 36(2), 63–74. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2753/JOA0091-3367360204

- Niskala, M., & Tarna, K. (2003). Yhteiskuntavastuuraportointi (social responsibility reporting). KHT Media. Gummerus Oy. 244.

- Öberseder, M., Schlegelmilch, B. B., & Gruber, V. (2011). Why don’t consumers care about CSR?’: A qualitative study exploring the role of CSR in consumption decisions. Journal of Business Ethics, 104(4), 449–460. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0925-7

- Panwar, R., Rinne, T., Hansen, E. Y., & Juslin, H. (2006). Corporate responsibility: Balancing economic, environmental, and social issues in the forest products industry. Forest Products Journal, 56(2), 4–12.

- Parsons, R. (1991). The potential influences of environmental perception on human health. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 11(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-4944(05)80002-7

- Peloza, J., & Shang, J. (2011). How can corporate social responsibility activities create value for stakeholders? A systematic review. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39(1), 117–135. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-010-0213-6

- Perez-Castillo, D., & Vera-Martinez, J. (2021). Green behaviour and switching intention towards remanufactured products in sustainable consumers as potential earlier adopters. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 33(8), 1776–1797.

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Polites, G. L., Roberts, N., & Thatcher, J. (2012). Conceptualizing models using multidimensional constructs: A review and guidelines for their use. European Journal of Information Systems, 21(1), 22–48. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/ejis.2011.10

- Rambocas, M., & Ramsubhag, A. X. (2018). The moderating role of country of origin on brand equity, repeat purchase intentions, and word of mouth in Trinidad and Tobago. Journal of Global Marketing, 31(1), 42–55. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08911762.2017.1388462

- Ruiz-Molina, M. E., & Gil-Saura, I. (2008). Perceived value, customer attitude and loyalty in retailing. Journal of Retail & Leisure Property, 7(4), 305–314. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/rlp.2008.21

- Saeidi, S. P., Sofian, S., Saeidi, P., Saeidi, S. P., & Saaeidi, S. A. (2015). How does corporate social responsibility contribute to firm financial performance? The mediating role of competitive advantage, reputation, and customer satisfaction. Journal of Business Research, 68(2), 341–350. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.06.024

- Savalei, V. (2008). Is the ML chi-square ever robust to nonnormality? A cautionary note with missing data. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 15(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701758091

- Sen, S., & Bhattacharya, C. B. (2001). Does doing good always lead to doing better? Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility. Journal of Marketing Research, 38(2), 225–243. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.38.2.225.18838

- Stanaland, A. J. S., Lwin, M. O., & Murphy, P. E. (2011). Consumer perceptions of the antecedents and consequences of corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 102(1), 47–55. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0904-z

- Sun, J., Yoo, S., Park, J., & Hayati, B. (2019). Indulgence versus restraint: The moderating role of cultural differences on the relationship between corporate social performance and corporate financial performance. Journal of Global Marketing, 32(2), 83–92. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08911762.2018.1464236

- Sweeney, J. C., & Soutar, G. N. (2001). Consumer perceived value: The development of a multiple item scale. Journal of Retailing, 77(2), 203–220. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4359(01)00041-0

- Tavakol, M., & Dennick, R. (2011). Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. International journal of medical education, 2(1), 53–55. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.4dfb.8dfd

- Tian, Z., Wang, R., & Yang, W. (2011). Consumer responses to corporate social responsibility (CSR) in China. Journal of Business Ethics, 101(2), 197–212. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-010-0716-6

- Tuškej, U., Golob, U., & Podnar, K. (2013). The role of consumer–brand identification in building brand relationships. Journal of Business Research, 66(1), 53–59. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.07.022

- Uddin, S. F., & Khan, M. N. (2018). Young consumer’s green purchasing behavior: Opportunities for green marketing. Journal of Global Marketing, 31(4), 270–281. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08911762.2017.1407982

- Wang, Q., Dou, J., & Jia, S. (2016). A meta-analytic review of corporate social responsibility and corporate financial performance: The moderating effect of contextual factors. Business & Society, 55(8), 1083–1121. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650315584317

- Wang, H., Wei, Y., & Yu, C. (2008). Global brand equity model: combining customer‐based with product‐market outcome approaches. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 17(5), 305–316. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/10610420810896068

- Watts, P., & Holme, R. (1999). Corporate social responsibility: Meeting changing expectations. World Business Council for Sustainable Development.

- Wheaton, B., Muthen, B., Alwin, D. F., & Summers, G. F. (1977). Assessing reliability and stability in panel models. Sociological Methodology, 8(1), 84–136.85. 4 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2707

- Yang, S., Jiménez, F. R., Hadjimarcou, J., & Frankwick, G. L. (2019). Functional and social value of Chinese brands. Journal of Global Marketing, 32(3), 200–215. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08911762.2018.1545955

- Yeh, C. H., Wang, Y. S., & Yieh, K. (2016). Predicting smartphone brand loyalty: Consumer value and consumer-brand identification perspectives. International Journal of Information Management, 36(3), 245–257. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2015.11.013

- Zhou, Y., Poon, P., & Huang, G. (2012). Corporate ability and corporate social responsibility in a developing country: The role of product involvement. Journal of Global Marketing, 25(1), 45–56. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08911762.2012.697385